Abstract

The spread of bacterial drug resistance has posed a severe threat to public health globally. Here, we cover bacterial resistance to current antibacterial drugs, including traditional herbal medicines, conventional antibiotics, and antimicrobial peptides. We summarize the influence of bacterial drug resistance on global health and its economic burden while highlighting the resistance mechanisms developed by bacteria. Based on the One Health concept, we propose 4A strategies to combat bacterial resistance, including prudent Application of antibacterial agents, Administration, Assays, and Alternatives to antibiotics. Finally, we identify several opportunities and unsolved questions warranting future exploration for combating bacterial resistance, such as predicting genetic bacterial resistance through the use of more effective techniques, surveying both genetic determinants of bacterial resistance and the transmission dynamics of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs).

Keywords: Bacterial resistance, Antibiotics, Mechanism of action, Antimicrobial peptides, Strategies, Global health

1. Introduction

The use of antibiotics over 100 years has triggered the widespread and rapid transfer of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) among bacteria across the world (Andersson, 2003; Larsson and Flach, 2021). Clinical resistance of the spirochaete bacterium Treponema pallidum to the antibiotic arsphenamine (also known as Salvarsan) was first reported in 1924 (Silberstein, 1924; Stekel, 2018). This was followed by the detection of resistance to the commercial penicillin in Staphylococcus aureus as early as 1942, rapidly followed in the 1950s and 1960s by the acquisition of resistance by other bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., and other bacterial species (Aslam et al., 2018; Rammelkamp and Maxon, 1942). Bacterial antibiotic resistance emerges almost concurrently as new antibiotics enter the market and are widely implemented in our society (Levy, 1998). Today, nearly all known bacterial pathogens have developed resistance to antibiotics (Barber and Rozwadowska-Dowzenko, 1948). Resistance continues to spread not only in pathogenic bacteria of human or animal origin, but also in environmental microbes. Resistance can also develop to some probiotics under the long-term selective pressure exerted by antibiotics (Li et al., 2020a-c; Radimersky et al., 2010; Al-Zahrani et al., 2019; Ejaz et al., 2021; Mohapatra et al., 2018; Fluit et al., 2001; Hawkey, 1986; Wozniak et al., 2019; Peterson and Kaur, 2018; Sharma et al., 2014). Antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) can survive and even grow in the presence of one or more antibacterial agents. Multidrug resistance (MDR) has been regarded as acquired resistance to at least one drug in three or more antimicrobial categories (Magiorakos et al., 2012). There is an increasing prevalence of MDR bacteria globally, which are exceedingly difficult to treat, constituting a growing global health problem (Zarfel et al., 2014; van Duin and Paterson, 2016; Breidenstein et al., 2011; Der Torossian and de la Fuente-Nunez, 2019), particularly for critical care practitioners. Thus, there is a tremendous interest in developing novel agents as alternative approaches for treating such infections (de la Fuente-Núñez et al., 2016; de la Fuente-Nunez et al., 2017; Torres et al., 2018; Torres et al., 2019; Mirghani et al., 2022).

Recently, increasing attention has focused on ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) from animals, plants, and microorganisms (Magana et al., 2020). These peptides, initially described in the 1960s, are known as promising natural alternatives to classical antibiotics because of their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity (Abdi et al., 2019; Torres et al., 2021; Melo et al., 2021; Torres et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b; Li et al., 2018). AMPs, also named host defense peptides, are critical components of the host innate defense system and have multi-functions, including anti-fungal, anti-viral, anti-parasitic, anti-tumor, and anti-inflammatory activity, which are different from conventional antibiotics (Hegedüs and Marx, 2013; Kurpe et al., 2020; Bakovic et al., 2021; Pérez-Cordero et al., 2011; Pereira et al., 2016; Arias et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2013; Mookherjee et al., 2006). AMPs can bind to the negatively charged bacterial surface and kill bacteria primarily through membrane disruption (Wang et al., 2020b; Nuri et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017b). The development of bacterial resistance to AMPs is unlikely due to their action on multiple cellular targets (Zasloff, 2002; Duperthuy, 2020). However, a growing number of studies have demonstrated that some pathogenic bacteria, including Group A Streptococcus (GAS), Salmonella enterica, and Campylobacter jejuni, can develop significant resistance to various AMPs, such as defensins, LL-37, cecropins, melittin, and PR-39 (Duperthuy, 2020; Malik et al., 2017; Lofton et al., 2013; Nizet et al., 2001; Cullen and Trent, 2010; Gruenheid and Le Moual, 2012). Additionally, traditional herbal medicines are a previously untapped source of potential antibacterial drugs. Indeed, herbal medicines have been shown to contain antibacterial compounds including alkaloids, organic acids, flavonoids, terpenes, essential oils, anthraquinones, etc.; they are widely considered as antibiotic alternatives because of their antimicrobial activity and low cytotoxicity (Yang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2013; Cushnie et al., 2014; Sieniawska et al., 2017; Tagousop et al., 2018; Adamczak et al., 2019; Parham et al., 2020; Soković et al., 2010; Manso et al., 2022; Kosalec et al., 2013). The use of naturally occurring herbal medicines to treat bacterial infections has a long history (over 5,000 years) in parts of Asia (such as China and India), Europe, North America, and Australia (Ekor, 2014; Majaz and Khurshid, 2016). For example, a combination of garlic, wine and other allium species described in a 1,000-year-old remedy from an Anglo-Saxon leechbook was able to kill methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and suppress biofilm infection (Harrison et al., 2015). Ointments containing tea leaf extracts have been utilized to treat diseases caused by MDR S. aureus, and natural products containing alkaloids have been used to treat diarrheic infectious diseases (Orchard and van Vuuren, 2017; Romero et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2014; Rubinstein and Keynan, 2013). However, there is still little experimental evidence demonstrating that certain bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae, Morganellaceae, Bacillaceae and staphylococci, develop resistance to extracts from herbal medicines (e.g., Cymbopogon citratus, Salvia officinalis, Artemisia vulgaris, etc.) (Singh et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2013).

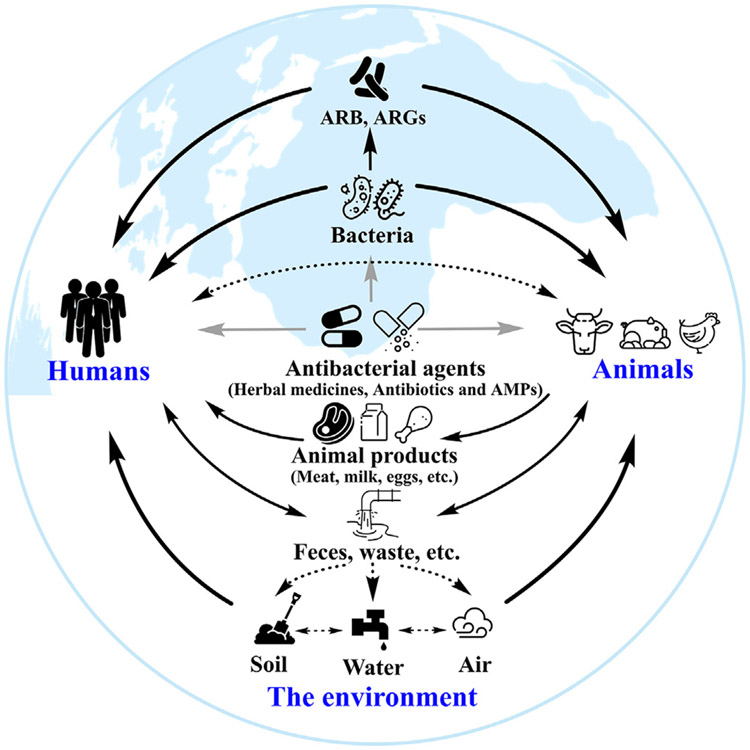

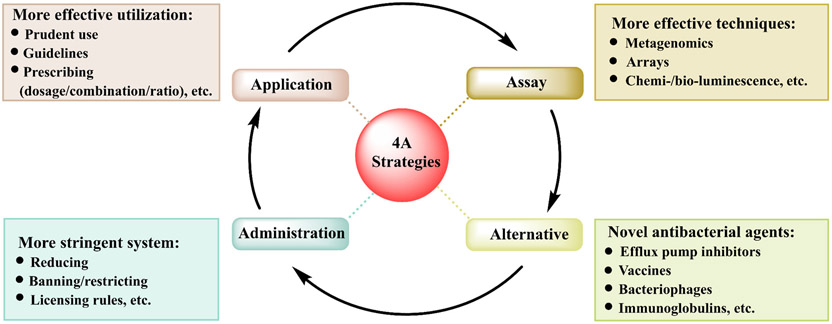

In this review, we outline various mechanisms whereby bacteria become resistant to antibacterial agents (including traditional herbal medicines, conventional antibiotics, and AMPs), as well as highlight the impact and economic burden of bacterial resistance on global health. Fig. 1 delineates the evolution of bacterial resistance to antibacterial agents over time. According to the One Health concept (Kim and Cha, 2021), we propose 4A strategies to combat the spread of bacterial drug resistance, including prudent Application of antibacterial agents, scientific Administration, development of effective Assays and find novel Alternatives to antibiotics. While describing how bacteria develop resistance to antibiotics, we hope to obtain insights into the mechanisms and general physiological effects that antibacterial agents exert on bacteria. Collectively, these insights may enable the development of more effective antibacterial agents that minimize drug resistance.

Fig. 1.

A brief profile of the evolution of bacterial resistance to current antibacterial agents. Of the large number of bacteria in the world, a fraction causes diseases in humans and animals, against which we need effective antibacterial agents. Some bacteria (such as the ESKAPE pathogens) are particularly resistant to antibiotics (Martin et al., 2015). These resistant bacteria and ARGs are rapidly disseminated in humans, animals, and the environment by direct or indirect contact with each other or with excreta, animal products, soil, and water contributing to the concept of One Health (Larsson and Flach, 2021; Rana et al., 1991). ARB: antibiotic-resistant bacteria. ARGs: antibiotic resistance genes. Black arrow: the spread of ARB and ARGs in humans, animals, and the environment. Gray arrow: effects of drugs on bacteria or bacterial infections in humans and animals.

2. Influence of bacterial drug resistance on health, food security, and economics

According to the WHO, drug resistance is currently one of the most severe threats to global health, food security, and economic burden, and can influence anyone at any age and any place. Drug resistance occurs naturally, but unfortunately, the misuse of conventional antibiotics in both human and animal health has greatly accelerated this process.

2.1. Global health

A growing number of pathogenic bacterial infections, such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, salmonellosis, and gonorrhea, are becoming harder to treat due to their increased resistance to conventional antibiotics. In the 2021 GLASS Report (involving 109 countries or territories), the proportions of E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae resistant to cotrimoxazole, a first-line drug, were 54.4 % and 43.1 % in urinary tract infections, 24.9 % for MRSA, and 65.48 % for Acinetobacter spp. against the third-generation cephalosporin in bloodstream infections (World Health Organization (WHO), 2021). Neisseria gonorrhoeae resistant to cefixime, the third-generation cephalosporin, has already been found in Thailand and the Philippines (World Health Organization (WHO), 2021). The prevalence of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) was 5 % in Asia, 16 % in Africa, 4 % in America, 3 % in South America, and 1 % in Europe (Shariati et al., 2020). The prevalence of colistin-resistant bacteria has increased to 43 % in Italy, 37.3–28.8 % in China, 31 % in Spain, and 20.8 % in Greece (Gogry et al., 2021; Que et al., 2022). In summary, bacterial antibiotic resistance has reached worrying levels in many countries worldwide.

In some cases, the available antibiotic treatment options for common bacterial infections are becoming ineffective. In countries such as Argentina, China, Australia, Chile, Lebanon, Colombia, the US, and Singapore, it has been shown that >50 % of patients infected with resistant K. pneumoniae have infections that do not respond to carbapenems (Wang et al., 2022a-c; Bassetti et al., 2021). Colistin and vancomycin, both last-resort drugs, even prove to be ineffective against MDR Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Klebsiella and E. coli) and VRSA (Gogry et al., 2021). The lack of therapeutic solutions is resulting in increased mortality, longer hospital stays, and higher medical costs (Aslam et al., 2018). In 2019, approximately 1.27 million people globally died from infections caused by ARB, and it has been estimated that 10,000,000 people will die every year by 2050 in the absence of effective treatments (Murray et al., 2022; Nishanth and Palanichamy, 2020; WHO, 2019). In Thailand, around 38,000 people die every year and there are 3.2 million hospital days due to resistant bacterial infections. In Europe and the US, 33,000 and 35,000 deaths, respectively, occur annually amounting to 2–2.5 million extra hospital days, and in India resistance causes the death of 58,000 babies per year (WHO, 2019; Zhen et al., 2021). Notably, death rates of patients with bacteremia induced by resistant ESKAPE pathogens were up 20–70 % from 2006 to 2011 (De Oliveira et al., 2020). These statistics depict a dire scenario and point to drug-resistant bacterial infections as a global health threat.

2.2. Food security

Conventional antibiotics are widely used in food animals, including chickens, pigs, cattle, and fish (Van Boeckel et al., 2015). In some countries, such as Vietnam, over 70 % of the total antibiotics produced are applied to animal production, largely for growth promotion and disease prevention rather than for therapeutic means (Carrique-Mas et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2015; Carrique-Mas et al., 2020; Van et al., 2020). It is currently projected that the antibiotic use in the farming sector will rise to 67 % by 2030 in certain developing countries (Van Boeckel et al., 2015). This widespread application of antibiotics in livestock and other animals is considered to be partially responsible for the rapid emergence of ARB. If not tackled appropriately, agricultural uses of antibiotics may have significant public health implications. ARB from animals may be transferred to humans through a variety of means, such as direct contact with farmers, food products, animal excretions, and environmental dispersal (Fig. 1) (Graham et al., 2009; Price et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2013).

The transfer of resistant bacteria from farm animals to humans was first reported in the past 40 years, and a high incidence of antibiotic resistance has been shown to take place in the gut microbiota of farm animals and workers (Smith et al., 2013). Over 90 % of conventional antibiotics applied in animals are excreted in urine and feces and then widely transmitted by groundwater, fertilizer, and surface runoff, profoundly impacting the environmental microbiome while also transferring ARB and resistance genes to humans (Fig. 1) (Smith et al., 2013).

As a result, food products from animals may be contaminated with ARB and ARGs. These ARB and resistance genes are present in the soil, water and in excretions from animals (Verraes et al., 2013; Que et al., 2022). As shown in Fig. 1, food may be contaminated with ARB and ARGs present in the environment during food processing. In food, the competence development of transformation (see above) for the uptake of plasmid-borne erythromycin and kanamycin resistance genes including erm(B) and nptII has been shown for Enterococcus faecalis, L. lactis and Bacillus subtilis in milk (Kharazmi et al., 2002; Zenz et al., 1998; Toomey et al., 2009). Antibiotic resistance has also been transferred to Campylobacter jejuni via transformation (Verraes et al., 2013).

During the production of certain food products, probiotics, starter cultures, bacteriophages, and biopreserving microorganisms are intentionally used for technical reasons (Verraes et al., 2013). Starter cultures are added to foodstuffs to induce fermentation in drinks and food, e.g., yoghurt, sauerkraut, and fermented sausages (Verraes et al., 2013). Some probiotics, such as Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, and Pediococcus, are mostly used for fermentation and biopreservation (Li et al., 2020a-c). Almost all probiotics contain resistance genes that may be transmitted to other bacteria (Li et al., 2020a-c; Verraes et al., 2013). Many Lactobacillus and Enterococcus species possess transferable ARGs, such as tet, cat, blaZ, and ermB, suggesting a higher risk of transmission to humans, while a few studies have detected the transfer of erm and tet resistance genes of Bifidobacteria from humans (Aires et al., 2007; Gueimonde et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2017a).

2.3. Economic burden

The economic impact of antibiotic resistance is enormous and growing. In the US, medical costs associated with drug-resistant infections are in the range of $18,588–29,069 per patient (Aslam et al., 2018). Direct economic losses of about $20 and $42 billion resulting from such infections have been recorded in the US and China, respectively, which is equivalent to 0.11 % of the US' and 0.37 % of China's yearly gross domestic product (GDP), and amounting to a societal economic burden of $35 billion and $77 billion annually, respectively (Aslam et al., 2018; Ventola, 2015; Zhen et al., 2021). In Europe, bacterial resistance accounted for €1.5 billion in economic burden, with over €900 million in hospital costs; societal costs have been estimated to reach 569 million extra hospital days yearly by 2050 (Kobeissi et al., 2021). Moreover, Sub-Saharan Africa has lost 0.1–2.5 % of its GDP due to bacterial resistance (Taylor et al., 2014). In total, resulting from drug-resistance, the annual global GDP in 2050 would decline by 3.8 % and 1.0 % in high-income and low-income countries, respectively, with >5 % of GDP loss, and the global economic burden of antibiotic resistance is predicted to amount to about $120 trillion by 2050 (Aslam et al., 2018; Zhen et al., 2019; Prestinaci et al., 2015; Bank, 2017).

Additionally, bacterial infections caused by antibiotic-resistant pathogens also impose a burden on families and communities because of lost salaries and health care costs. In India, the average cost of treating a resistant bacterial infection is about $700, which is equivalent to 442 days of salary for a rural male worker. In Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, treatments for patients infected with antibiotic-resistant pathogens incur an additional cost of $10,000–$40,000 (Bank, 2017; Cecchini et al., 2015). It is predicted that approximately 24 million people across the globe would be pushed into extreme poverty due to bacterial resistance by 2030, especially in developing countries, and 28.3 million people would fall into poverty in 2050 (Zhen et al., 2019; Bank, 2017; Cecchini et al., 2015; Kotwani et al., 2021). In addition, annual global increases in health care costs due to drug-resistance infections may be up to $0.3–1 trillion per year by 2050, including $23 billion in Europe and the US, and $2.9 trillion in OECD countries (Bank, 2017; Cecchini et al., 2015). If effective strategies are not put into effect in the near future, resistant bacteria may have an even larger negative effect on global public health, food security, and the economy.

3. Bacterial resistance to antibacterial agents

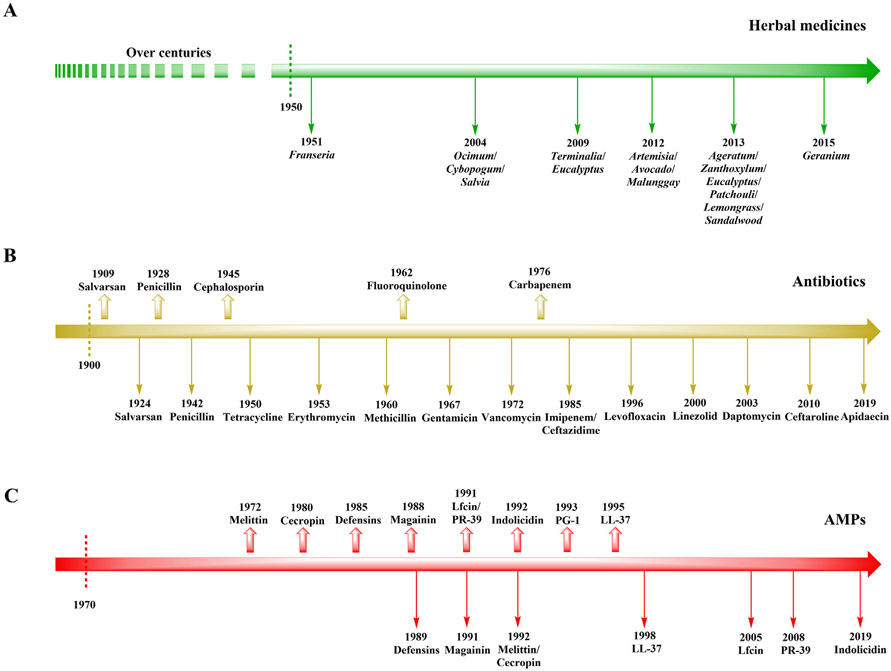

Various bacterial diseases may be treated with currently available antibacterial agents (including traditional herbal medicines and conventional antibiotics). Unfortunately, bacteria have developed resistance to many of these agents (Rubinstein and Keynan, 2013; Chromek et al., 2006; Kai-Larsen et al., 2010). Comparably, conventional antibiotics have contributed substantially to multidrug resistance due to their over prescription world-wide (Miranda et al., 2018; Remesh et al., 2013; Ozkurt et al., 2005). The timeline for bacterial resistance development toward antibacterial agents is provided in Fig. 2, which includes the discovery date of each drug (traditional herbal medicines, conventional antibiotics, and AMPs) along with the year in which bacterial resistance was first reported.

Fig. 2.

Timeline for bacterial resistance to develop against current antibacterial agents. (A) Traditional herbal medicines. (B) Conventional antibiotics. (C) Next-generation AMPs. Defensins: phase IV; magainin: phase III; PG-1: phase II; LL-37: phase I and II; other AMPs: no data. Rightward arrow: timeline; upward arrow: drug discovery date; downward arrow: Year when drug resistance was first reported.

3.1. Bacterial resistance to herbal medicines

For centuries, traditional herbal medicines have been used for the management of various bacterial diseases in many developed and developing countries, however the study of bacterial resistance to herbal drugs has remained understudied (Martin and Ernst, 2003; Bittner Fialová et al., 2021; Odongo et al., 2022). In recent decades, some bacteria (especially enteric bacteria) have been shown to develop resistance to herbal medicines (Fig. 2A; Table 1).

Table 1.

Bacterial resistance to traditional herbal medicines.

| Time | Bacteria | Resistance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | S. pullorum and D. pneumoniae | Extracts of Franseria ambrosioides leaves and stems in vitro and in vivo (chicks and mice) | (Parlett, 1951) |

| 1951 | K. pneumoniae | Extracts of Franseria ambrosioides in vitro | (Parlett, 1951) |

| 2004 | P. aeruginosa | Oils extracted from Ocimum gratissimum, Cybopogum citratus, and Salvia officinalis | (Pereira et al., 2004) |

| 2009 | P. aeruginosa, S. enterica Typhimurium, E. coli and K. pneumoniae | Extracts of Terminalia arjuna and Eucalyptus globulus | (Khan et al., 2009) |

| 2010 | P. aeruginosa | Oils extracted from Cymbopogon citratus | (Naik et al., 2010) |

| 2011 | Enterobacteriaceae (Hafnea alvei, Leclercia adecarboxylata, Salmonella, Escherichia, Citrobacter, Kluyvera cryocrescens, Erwinia ananas, Pragia fontium, and Klebsiella), Morganellaceae (Xenorhabdus luminescens and Providencia), Proteobacteria (Proteus), Yersiniaceae (Serratia), Bacillaceae (Bacillus) and staphylococci | Oils extracted from C. citratus | (Singh et al., 2011) |

| 2012 | Bordetella and Bacillus coagulans | Oils extracted from Artemisia vulgaris | (Singh et al., 2012) |

| 2012 | Pediococci (P. acidilactici and P. pentosaceous) and L. plantarum BS | Extracts of avocado (Persea americana Mill.) and malunggay (Moringa oleifera Lam.) | (Saguibo and Elegado, 2012) |

| 2013 | Citrobacter, Edwardsiella, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Raoultella, Salmonella, etc. | Extracts of Ageratum conyzoides and Zanthoxylum rhetsa; essential oils from eucalyptus, patchouli, lemongrass, sandalwood, and Artemisia vulgaris | (Singh et al., 2013) |

| 2013 | Actinobacillus, Aeromonas, E. coli, Salmonella, Klebsiella, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Vibrio minicus, Alcaligenes and Brucella | Oils extracted from Salvia officinalis L. sage | (Singh, 2013) |

| 2015 | E. faecium and S. thermophilus | Extracts of Geranium sanguineum and Salvia officinalis leaves | (Teneva-angelova and Beshkova, 2015) |

In the early 1950s, Parlett investigated the resistance of Salmonella pullorum, K. pneumoniae, and Diplococcus pneumoniae to plant extracts (Parlett, 1951). S. pullorum and D. pneumoniae were found to develop resistance to the extracts from the leaves and stems of Franseria ambrosioides in chicks and mice, and K. pneumoniae developed resistance in vitro: the inhibitory concentration of K. pneumoniae increased from 4.5 to 7.5 mg/ml over an 8-week period of subculturing. A few reports have demonstrated the prevalence of resistance to herbal drugs in clinical and environmental bacterial strains. Some clinical bacterial strains, such as Salmonella spp., Escherichia, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and staphylococci were also resistant to essential oils extracted from herbal plants, including Ocimum gratissimum, Cymbopogon citratus, Cybopogum citratus, Salvia officinalis, and A. vulgaris (Singh et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2011; Naik et al., 2010; Pereira et al., 2004). Singh et al. (2013) found that bacterial strains (including Actinobacillus spp., Aeromonas spp., Salmonella spp., E. coli, and Klebsiella spp.) isolated from sick or dead animals were resistant to S. officinalis L. sage oil (Singh, 2013). Moreover, MDR strains of E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. enterica Typhimurium, and K. pneumoniae were resistant to extracts of Terminalia arjuna and Eucalyptus globulus (Khan et al., 2009). A total of 194 faecal samples were collected from house geckos and detected the antibiotic and herbal drug sensitivity of bacterial isolates from such samples (Singh et al., 2013). The results indicated that MDR bacteria (including Citrobacter, Edwardsiella, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, and Salmonella) accounted for 12.1 % of the isolates tested for antimicrobial drug sensitivity; among them, only 27.8 % and 13.9 % of the bacterial strains were inhibited by the extracts of Ageratum conyzoides and Zanthoxylum rhetsa; only 3.1–5.4 % of the bacterial strains were inhibited by essential oils from eucalyptus, patchouli, lemongrass, sandalwood, and Artemisia vulgaris. Of note, MDR strains of E. coli, Klebsiella and Raoultella developed resistance to extracts from herbal medicines (such as Ageratum conyzoides, Artemisia vulgaris, Zanthoxylum rhetsa, patchouli, etc.) (Singh et al., 2013). These results indicate that bacterial resistance to herbal drugs and antibiotics are likely to go hand in hand (Singh et al., 2013).

Additionally, Saguibo and Elegado (2012) detected resistance to leaf extracts of malunggay (Moringa oleifera Lam.) and avocado (Persea americana Mill.) leaves in probiotic lactic acid bacteria (LAB), including Lactobacillus plantarum BS, Pediococcus acidilactici strains (4E5, AA5a, 3G3 and K3A2–2) and P. pentosaceous K2A2–3 (Saguibo and Elegado, 2012). These results revealed that all LAB developed selective resistance to some plant extracts; the pediococci strains exhibited higher resistance than L. plantarum BS. Other probiotics, such as the Streptococcus thermophilus and Enterococcus faecium strains isolated from Geranium, were resistant to the extracts of Geranium sanguineum leaves at a concentration of 30 mg/ml; the E. faecium and S. thermophilus isolates from Salvia had increased resistance to S. officinalis leave extracts, at concentrations of 30–100 mg/ml (Table 1) (Teneva-angelova and Beshkova, 2015).

3.2. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics

The first antimicrobial, arsphenamine Salvarsan, was discovered in 1909 and clinical resistance to this drug was first reported in 1924 (Silberstein, 1924; Stekel, 2018). Penicillin was discovered in 1928, then commercialized and implemented in society to treat bacterial infections in the 1940s (Ventola, 2015). However, penicillin-resistant bacteria emerged as early as 1943, and this trend has continued with every antibiotic that has been deployed in our society (Fig. 2B) (Ventola, 2015). Some bacteria have intrinsic resistance and they may also develop resistance to antibiotics through mutation (i.e., adaptive resistance). Resistance can develop in the environment by the uptake of genetic elements encoding resistance genes or mutations in bacterial genomes (Kummerer, 2004; Méhi et al., 2014).

Recent years have seen a rapid rise in the prevalence of pathogenic MDR bacteria globally, representing a serious threat to global health (van Duin and Paterson, 2016). The most important types of ARB include E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species (ESKAPE) (Santajit and Indrawattana, 2016). These resistant bacteria are endowed with various intrinsic resistance mechanisms to antibiotics and can also acquire new resistance genes or mutations (Rubinstein and Keynan, 2013).

(i). Enterococci.

Enterococci are Gram-positive facultative anaerobes often found in the gut of animals and humans. More than 20 Enterococcus species have been reported, which are resistant to aminoglycosides, vancomycin, and ampicillin (Rubinstein and Keynan, 2013). Among them, E. faecium and E. faecalis are the most common vancomycin-resistant pathogens (Santajit and Indrawattana, 2016). MDR enterococci have rapidly emerged in recent years; these strains exhibit high-level gentamicin and penicillin resistance due to β-lactamase production. Increasing numbers of vancomycin-resistant and ampicillin-resistant infections caused by enterococci have been detected in healthcare facilities, animals, and humans (Rubinstein and Keynan, 2013; Freitas et al., 2018; Correa-Martínez et al., 2022; Bunnell et al., 2022; Freitas et al., 2022; Samad et al., 2022).

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) emerged in North America during the late 1980s and have disseminated across the world with an incidence of 20–30 % (Rubinstein and Keynan, 2013). For example, vancomycin-resistant MDR enterococci have emerged in Europe (Huycke and Gilmore, 1998; Murray et al., 1991; Leclercq et al., 1988). About 2–5 % of the European population and about 0.1–3.7 % of the population in China are intestinal carriers of vancomycin-resistant E. faecium acquired from food (Rubinstein and Keynan, 2013; Zhou et al., 2020). Individuals at the highest risk of infection by VRE are hospital workers and those working in agriculture, food industry, and waste and wastewater treatment, especially when in direct contact with patients and feces (Freitas et al., 2022; Samad et al., 2022). VRE outbreaks can also take place in transplant and intensive care units.

(ii). S. aureus.

The Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus is frequently present on the skin and in the upper respiratory tract, and it is the major cause of soft tissue and skin infectious diseases. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was first identified in England in 1961 and disseminated globally, becoming a leading cause of bacterial infections in animals and humans (Lee et al., 2018a,b; Morgan, 2008; Romero and de Souza da Cunha, 2021; Argudín et al., 2021; Kejela and Dekosa, 2022). MRSA has also been found in livestock, poultry, and companion animals. New strains of MRSA emerging from animals, particularly pigs, are increasingly causing infections in humans (Morgan, 2008; Abdullahi et al., 2021). In the US, MRSA causes over 80,000 severe infections per year and was responsible for 100,000 deaths in 2019 (Murray et al., 2022). MRSA is regarded as a “superbug” as it is resistant to all β-lactams, among others, and constitutes a growing public health threat.

Vancomycin is one of the last-line antibacterial agents to treat MRSA infections and has been used for nearly 40 years since the 1980s (Werner and Witte, 2008). However, vancomycin-resistant S. aureus isolates have been found for over 20 years (Cong et al., 2020; Shariati et al., 2020; Kejela and Dekosa, 2022). Clinical cases of VRSA (with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ≥ 16 μg/ml) and vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) (with MIC of 4–8 μg/ml) are becoming increasingly common (Chambers and Deleo, 2009). The presence or absence of vanA or other van resistance genes is used to determine whether S. aureus isolates can be classified as VRSA (Werner and Witte, 2008). VRSA is of special concern because resistance genes from VRE are transmitted among species. VRSA isolates carry both the vanA and mecA resistance determinants, which confer resistance to vancomycin and methicillin, respectively (Appelbaum, 2007; Desta et al., 2022).

(iii). K. pneumoniae.

The Gram-negative bacterium K. pneumoniae is ubiquitously found on the mucosal surface in humans and animals, water and soil (Wang et al., 2020a). K. pneumoniae exists in the gastrointestinal tract and the nasopharynx of humans; it can also enter the blood circulation or other tissues, causing infection (Piperaki et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2021).

Data from the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network for the years 2005–2015 identified K. pneumoniae resistant to all four main categories of antibiotics: carbapenems, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and third generation cephalosporins. Notably, carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) has been found in Italy, Greece, and Romania, with 40–60 % resistance rates, as well as other countries, highlighting the major role of CRKP in the burden of antibiotic resistance (Navon-Venezia et al., 2017). Infections caused by CRKP are highly recalcitrant and impose a tremendous problem particularly in severely ill patients.

Additionally, the production by K. pneumoniae of the enzyme known as New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM-1), which is encoded by the blaNDM-1 gene, has increased the incidence of CRKP isolates and may affect other antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and β-lactams (Kumarasamy et al., 2010; Yong et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2021;Wang et al., 2022a-c ). Carbapenemase-mediated MDR K. pneumoniae cannot currently be completely eradicated with existing drugs.

(iv). A. baumannii.

The Gram-negative organism A. baumannii, a coccobacillus, is an important opportunistic pathogen (Joly-Guillou, 2005; Murray et al., 2022). A. baumannii, which is responsible for 2–10 % of all hospital diseases infected by Gram-negative bacteria, is regarded as one of six major MDR pathogens in hospitals by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (Talbot et al., 2006; Murray et al., 2022).

The WHO published in 2017 a list of global research priorities to treat MDR and broadly resistant bacteria and ranked A. baumannii first on its list (Isler et al., 2019; Kurihara et al., 2020). Treatment for each infection caused by MDR A. baumannii is estimated to cost $33,510–$129,917 (Zhou et al., 2019). Moreover, patients with bacteremia have high mortality rates (56.2 %) due to serious infections caused by MDR A. baumannii (Gramatniece et al., 2019). The attributed mortality rate of MDR A. baumannii varies from 8.4 to 89 % (Cornejo-Juarez et al., 2020; Falagas and Rafailidis, 2007).

(v). P. aeruginosa.

P. aeruginosa is a Gram-negative rod-shaped γ-Proteobacterium found in all habitats (Breidenstein et al., 2011; Gellatly and Hancock, 2013; Moradali et al., 2017). Although P. aeruginosa is considered a conditional pathogen, it is the bacterium most commonly related to hospital-acquired infectious diseases and ventilator-associated pneumonia (Barbier et al., 2013). This bacterium is responsible for high mortality and morbidity in immunocompromised individuals and in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) (Sadikot et al., 2005). P. aeruginosa is the leading pathogen causing CF lung diseases; chronic infection with P. aeruginosa is recalcitrant to treatment with antibiotics and leads to decreased pulmonary function and finally to mortality in CF patients (Lyczak et al., 2002).

It is exceedingly difficult to completely eradicate P. aeruginosa as it possesses intrinsic, acquired or adaptive resistance, through its low membrane permeability, to a wide variety of antibiotics including fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and β-lactams (Hancock and Speert, 2000; Nicas and Hancock, 1983; Pelegrin et al., 2021). Because most antibiotic molecules do not enter P. aeruginosa cells, they are ineffective. Some ARGs such as ftsI, mcr and oprD in P. aeruginosa may play a role in resistance to β-lactams, carbapenem, cetftolozan, tazobactam, among other antibiotics (Pang et al., 2019; Pelegrin et al., 2021).

(vi). Enterobacteriaceae.

Enterobacteriaceae (which includes the genera Escherichia, Citrobacter, Serratia, Salmonella, Enterobacter, Proteus, and others) are non-fastidious Gram-negative bacilli that can result in opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients. Enterobacteriaceae have developed a variety of mechanisms against antibiotics (Santajit and Indrawattana, 2016). In 2020, the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) reported that the rate of resistance to ciprofloxacin commonly applied in the treatment of urinary tract infections was in the range of 4.1 % to 79.4 % for K. pneumoniae and of 8.4 % to 92.9 % for E. coli. Resistance to fluoroquinolone in E. coli and Salmonella, as well as other genera, is also widespread. In China, a distinct increase was detected in ARGs among E. coli isolates from livestock, leading to resistance to veterinary (norfloxacin and florfenicol) and human medicines (cephalosporins, meropenem and colistin) for 50 years (from the 1970s to 2019) (Yang et al., 2022). Enterobacteriaceae resistant to colistin, a last-line antibiotic, have also been detected in several countries (e.g., Italy, Spain, Belgium, UK, the US, Japan, Egypt, etc.) (Aghapour et al., 2019; Gharaibeh and Shatnawi, 2019; Qadi et al., 2021; Kawamoto et al., 2022).

A few studies investigating patients found that approximately 5.8 % of E. coli and 31.1 % of Enterobacter spp. displayed resistance to third- or fourth generation cephalosporins (Murray et al., 2022; Paterson, 2006; Shah et al., 2004). Genes encoding extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) are frequently found in Enterobacteriaceae, endowing high-level resistance to sulfonamides, aminoglycosides, and quinolones. ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae are MDR and highly resistant to all currently available antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance not only impedes the effective treatment and prevention of Enterobacteriaceae infections but can also be transferred from Enterobacteriaceae to a wide range of bacterial species (Paterson, 2006).

3.3. Bacterial resistance to next-generation AMPs

AMPs are vital components of the host native defense system targeting pathogenic bacteria. These peptides are typically short and positively charged (Koprivnjak and Peschel, 2011). Since bombinin (1962) and melittin (1972) were isolated from the skin secretions of Bombina variegate and honeybee venom, respectively, over 5,948 AMPs (containing natural and synthetic ones) have been found across the tree of life displaying broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity (https://dramp.cpu-bioinfor.org/) (Koprivnjak and Peschel, 2011; Habermann, 1972). However, most AMPs are still in preclinical and clinical development (Lazzaro et al., 2020; Boparai and Sharma, 2020). Bacteria take longer to initiate resistance to AMPs than to conventional antibiotics because AMPs exhibit multifunctional mechanisms of action (Zasloff, 2002). However, there is increasing data reporting that bacteria such as GAS, S. enterica, and Campylobacter jejuni eventually develop resistance to various AMPs (Nizet et al., 2001; Cullen and Trent, 2010; Gruenheid and Le Moual, 2012; Lofton et al., 2013; Andersson et al., 2016; Malik et al., 2017; Duperthuy, 2020; Wang et al., 2022a-c) (Fig. 2C; Table 2). Similarly to conventional antibiotics, the development of bacterial resistance to AMPs is eventually expected when these agents are deployed in clinical practice (Aslam et al., 2018).

Table 2.

Summary of bacterial resistance to new generation AMPs and its mechanisms.

| Types of AMPs |

Reported time |

Bacteria | AMPs | Genes involved in AMP resistance |

Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defensins | 1989 | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | NP-1 | phoP | The phoP mutants play a role in resistance | (Fields et al., 1989) |

| 1996–2013 | B. pertussis | HNP-1, pBD-1 and pBD-2 | brkA and bvg | BrkA and bvg-activated genes and surface modification mediate resistance | (Elahi et al., 2006; Fernandez and Weiss, 1996; Taneja et al., 2013) | |

| 1998 | N. gonorrhoeae | rNP-2 and HNP-2 | mtrR | Energy-dependent mtr efflux systems contribute to resistance to defensins | (Shafer et al., 1998) | |

| 1999–2017 | S. aureus and MRSA | HNP-1, HNP-2, HNP-3, hBD-1, hBD-2, hBD-3 and hBD-4 | dltA/B/C, mprF, hemB, graR/S, qacA, srrAB, aps and mprF | The mutant teichoic acids lacking D-alanine, SCV phenotype and modification of lipid A by phosphoethanolamine transferase LptA endow S. aureus with resistance to defensin | (Habets and Brockhurst, 2012; Kubicek-Sutherland et al., 2017; Glaser et al., 2014; Li et al., 2007; Peschel et al., 1999; Ernst et al., 2009; Peschel et al., 1999; Peschel et al., 2001) | |

| 2003 | S. agalactiae | HNP-1, HNP-2 and HNP-3 | dtlA | D-alanylation of LTA contributes to resistance to AMPs | (Poyart et al., 2003) | |

| 2004 | P. aeruginosa | hBD-1 and rabbit NP1 | pmrAB | PhoPQ two-component system contributes to resistance to AMP | (Moskowitz et al., 2004) | |

| 2005 | Porphyromonas gingivalis | hBD-2 | NN | ND | (Shelburne et al., 2005) | |

| 2006 | B. bronchiseptica | pBD-1 and hBD-2 | NN | ND | (Elahi et al., 2006) | |

| 2007–2015 | H. ducreyi | α-Defensins (HNP-1, HNP-2 and HNP-3) and β-defensins (hBD-2, hBD-4 and hBD-5) | lptA, ptdA and ptdB | Modification of lipid A by phosphoethanolamine transferase LptA confer to resistance to AMPs | (Trombley et al., 2015; Mount et al., 2007; Mount et al., 2010) | |

| 1999–2017 | S. aureus and MRSA | HNP 1–3, hBD-1, hBD-2, hBD-3 and hBD-4 | dltA/B/C, mprF, graR/S, qacA, srrAB, aps and mprF | Reduced electron transport, SCV phenotype, modification of teichoic acids and resistance MprF protein are associated with resistance to defensins | (Kubicek-Sutherland et al., 2017; Li et al. 2007; Peschel et al., 1999; Ernst et al. 2009) | |

| 2011 | K. pneumoniae | hBD-1, hBD-2 and HNP-1 | cps, ugd, pmrF and pagP | Capsule expression and lipid A modification with aminoarabinose and palmitate contribute to resistance to AMPs | (Llobet et al., 2011) | |

| 2013 | B. pertussis | HNP-1 and HNP-2 | dra | dra contributes to AMP resistance by decreasing the electronegativity of the cell surface | (Taneja et al., 2013) | |

| 2015 | Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | hAD5 | lpxF | LPS modification confers to resistance to AMPs | (Cullen et al., 2015) | |

| 2019 | E. coli | hBD-3 | folA, mlaD, malE, lpxA, acpS and ublA | Reduction in the net negative surface charge of the bacterial membrane by perturbing the Mla pathway confers to resistance to human membrane-targeting AMPs | (Kintses et al., 2019a,b) | |

| Cathelicidins | 1998–2016 | N. gonorrhoeae | LL-37 | mtrR, misR and lptA | The capsule and the endotoxin LOS, energy-dependent multiple transferable efflux systems (such as MtrCDE), MisR response regulator and MisS sensor kinase are involved in resistance to AMP | (Shafer et al., 1998; Kandler et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2009) |

| 2001–2005 | GAS | Cathelicidin and CRAMP | Tn917, crgR and dltA | Chromosomal location of the Tn917 insertion, crgR regulator and D-alanylation of teichoic acid endow with resistance to AMPs | (Nizet et al., 2001) | |

| 2004 | P. aeruginosa | LL-37, CAP18 and SMAP29 | pmrAB | PhoPQ two-component system contributes to resistance to AMP | (Moskowitz et al., 2004) | |

| 2005–2009 | N. meningitidis | LL-37 | mtrD, lptA, siaC, siaD and lipA | The endotoxin LOS and polysaccharide capsule contribute to resistance | (Spencer et al., 2018; Kristian et al., 2005; Tzeng et al., 2005) | |

| 2006–2019 | E. coli | LL-37 and PR-39 | folA, mlaD, malE, lpxA, acpS and ublA | Curli increased adherence to epithelial cells and resistance to AMPs | (Chromek et al., 2006; Kai-Larsen et al., 2010; Kintses et al., 2019a,b) | |

| 2010 | H. ducreyi | LL-37 | sapA | The SapA transporter confers to resistance to AMP | (Mount et al., 2010) | |

| 2007–2017 | S. aureus and MRSA | LL-37 and PR-39 | dltA/B/C, mprF, graR/S, qacA, hemB, aps and mprF | Reduced electron transport, SCV phenotype, the aps sensor system and resistance MprF protein are associated with resistance to AMPs | (Kubicek-Sutherland et al., 2017; Glaser et al., 2014; Sakoulas et al., 2014; Thedieck et al., 2006; Li et al. 2007; Ernst et al. 2009) | |

| 2013–2018 | A. baumannii | LL-37 | pmrB | Nonsynonymous point mutations within pmrB conferring resistance to AMP | (Spencer et al., 2018; Napier et al., 2013) | |

| 2013 | S. enterica Typhimurium | LL-37 and PR-39 | pmrB, phoP and waaY (or rfaY) | Mutations in two-component signal transduction pathways and in the lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis pathway confer to resistance to AMPs | (Lofton et al., 2013) | |

| 2015 | Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | LL-37 and CRAMP | lpxF | LPS modification confers to resistance to AMPs | (Cullen et al., 2015) | |

| Others | 1991–2017 | S. enterica Typhimurium | Magainin 2, cecropin P1, mastoparan, melittin, CNY100HL, WGH, Lfcin and Cycloviolacin O2 | sbmA, hemA, hemB, hemC, hemL, pmrB, waaY and phoP | Inactivation and mutations in two-component signal transduction pathways and in the LPS biosynthesis pathway reduce the uptake of AMPs | (Malik et al., 2017; Lofton et al., 2013; Glaser et al., 2014; Pranting et al., 2008; Pranting and Andersson, 2010; Paterson et al., 2009; Groisman et al., 1992; Rana et al., 1991) |

| 1996 | B. pertussis | Cecropin P1 | brkA and bvg | BrkA protein and bvg-activated genes mediate resistance | (Fernandez and Weiss, 1996) | |

| 1998 | B. bronchiseptica and B. pertussis | Cecropin (P and B), magainine-II-amide, protamine and melittin | bvgS, wlbA and wlbL | The loss of the O-specific side chains and the prevalence of the LPS core structure confer to resistance to AMPs | (Banemann and Gross, 1998) | |

| 1998–2005 | N. gonorrhoeae | PG-1 | mtrR and lptA | Energy-dependent mtr efflux systems and lipid A modification contribute to resistance to AMPs | (Shafer et al., 1998; Tzeng et al. 2005) | |

| 1999–2020 | S. aureus | LfcinB, melittin, pexiganan, indolicidin, protegrins, tachyplesins and magainin II | hemB, pmtR (ytrA), vraG (bceB), atl, namA, menF, atl and aps | SCV phenotype and the aps sensor system endow S. aureus with resistance to AMPs | (Habets and Brockhurst, 2012; El Shazely et al., 2020; Samuelsen et al., 2005; Li et al. 2007; Peschel et al., 1999) | |

| 2000 | P. aeruginosa | CP28 and CP29 | phoQ | The PhoP-PhoQ system contributes to resistance to AMPs | (Macfarlane et al., 2000) | |

| 2003 | S. agalactiae | Indolicidin, magainin II, cecropin B, PG-1 and PG-3 | dtlA | D-alanylation of LTA contributes to resistance to AMPs | (Poyartet al. 2003) | |

| 2006 | P. fluorescens | Pexiganan | NN | ND | (Perron et al., 2006) | |

| 2006–2019 | E. coli | Membrane-targeting (pexiganan, CAP18, cecropin P1, etc.) and intracellular-targeting AMPs (apidaecin IB, bactenecin 5, indolicidin, etc.) | folA, mlaD, malE, lpxA, acpS and ublA | Reduction in the net negative surface charge of the bacterial membrane by perturbing the Mla pathway confers to resistance to human membrane-targeting AMPs | (Kintses et al., 2019a,b; Perron et al., 2006) | |

| 2011 | K. pneumoniae | Magainin 2 | ugd, pmrF and pagP | Capsule expression and lipid A modification with aminoarabinose and palmitate contribute to resistance to AMPs | (Llobet et al., 2011) | |

| 2017 | MRSA | CNY100HL and WGH | dltA/B/C, mprF, graR/S, qacA and srrAB | Reduced electron transport and SCV phenotype are associated with resistance to AMPs | (Kubicek-Sutherland et al., 2017) | |

| 2019 | Gut microbiota | Cecropin P1, indolicidin, PR-39, R8, tacyplesin II, omigannan, etc. | acr, alm, anr, pmr, arn, bra, col, cpr, dlt, epi, lpx, mcr1, mtr, par, pho, yej, etc. | Intrinsic resistant genes contribute to AMPs | (Kintses et al., 2019a,b) |

ND; no data.

(i). Defensins.

Defensins (18–45 amino acids) are small cationic defense peptides that are rich in cysteine and found in animals, plants, and fungi. Characterized by the linking pattern of highly conserved cysteines, the following three sub-families of defensins have been classified: α (Cys1–6, Cys2–4 and Cys3–5), β (Cys1–5, Cys2–4 and Cys3–6), and circular θ (no free N- and C-terminus), mainly secreted by neutrophils, epithelial cells, and leukocytes, respectively (Ganz, 2003). Defensins display potent antimicrobial and immune activities (Ganz, 2003; Arnett and Seveau, 2011; Contreras et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2022).

A few studies have shown that defensins can induce resistance in several bacterial pathogens (Table 2) (Elahi et al., 2006). For example, Bordetella pertussis displayed various levels of resistance to human α-defensin 1 (HNP-1) and α-defensin 2 (HNP-2) (Fernandez and Weiss, 1996; Taneja et al., 2013). The dra locus confers defensin resistance by reducing the cell surface electronegativity of B. pertussis (Taneja et al., 2013). Elahi et al. evaluated the protective effects of β-defensin against B. pertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica in newborn piglets and found that B. bronchiseptica was fully resistant to porcine β-defensin 1 (pBD-1) and human β-defensin 2 (hBD-2), but B. pertussis was highly sensitive to pBD-1 and partially resistant to pBD-2 (Elahi et al., 2006). N. gonorrhoeae developed resistance to the rabbit defensin 2 (rNP-2) and HNP-2 by a mechanism related to energy-dependent mtr efflux systems (Shafer et al., 1998). Shelburne et al. investigated the effects of human β-defensin 1 (hBD-1), β-defensin 2 (hBD-2), β-defensin 3 (hBD-3), and β-defensin 4 (hBD-4) on the oral periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis and found that these four hBDs can induce resistance in multiple P. gingivalis strains after pretreatment with sublethal levels of defensins or exposure to environmental conditions such as heat and peroxide stress (Shelburne et al., 2005).

H. ducreyi has high resistance to human α-defensins (including HNP-1, HNP-2 and HNP-3) and β-defensins (such as hBD-2, hBD-4 and hBD-5), respectively (Mount et al., 2007; Mount et al., 2010). This may be related to modification of pEtN transferase in Haemophilus ducreyi, conferring resistance to α-defensins and β-defensins (Trombley et al., 2015). Moreover, lipid A modification by phosphoethanolamine transferase LptA in H. ducreyi can confer resistance to human defensins (such as α-defensin HNP-3 and β-defensin hBD-5) (Trombley et al., 2015). Exposure of K. pneumoniae to polymyxin induces cross-resistance to hBD-1, hBD-2, and HNP-1 (Llobet et al., 2011). Treatment with polymyxin B led to upregulated expression of genes cps, pmrF, ugd, and pagP, conferring resistance to defensins (Llobet et al., 2011). A few studies have demonstrated that S. aureus rapidly became resistant to HNP-1, hBD-2 and hBD-3 (Habets and Brockhurst, 2012; Kubicek-Sutherland et al., 2017). MRSA mutants resistant to LL-37 exhibited increased cross-resistance to hBD-1, hBD-2 and hBD-3; PR-39-resistant S. aureus mutants displayed cross-resistance to hBD-1 and hBD-4; a wheat germ histone (WGH)-resistant S. aureus mutant showed resistance to hBD-1, hBD-3 and hBD-4. These observations indicate that resistant S. aureus mutants may evade host defensins (Kubicek-Sutherland et al., 2017); in fact, S. aureus resistance to defensins is linked to the formation of the small colony variant (SCV) phenotype and reduced electron transport (Habets and Brockhurst, 2012; Kubicek-Sutherland et al., 2017; Glaser et al., 2014).

(ii). Cathelicidins.

Cathelicidins are a third general class of epithelial AMPs that are expressed in the intestinal epithelium in humans and other animals and can kill bacteria by membrane disruption (Bals and Wilson, 2003; Batista Araujo et al., 2022). Recent data have demonstrated that some bacterial pathogens (including Neisseria, GAS, S. enterica, and E. coli) display resistance to cathelicidins (Table 2) (Lofton et al., 2013; Nizet et al., 2001; Chromek et al., 2006).

Wild-type N. gonorrhoeae strain FA19 is 4-fold to 8-fold more highly resistant to LL-37 than its isogenic misR-null mutant JK100, which is attributed to the MisR response regulator (Kandler et al., 2016). Moreover, the energy-dependent efflux systems-multiple transferable resistance (mtr), MtrCDE and resistance/nodulation/division (RND) in N. gonorrhoeae also contribute to resistance to LL-37 (Shafer et al., 1998; Kandler et al., 2016; Spencer et al., 2018). Another wild-type N. meningitidis serogroup C strain FAM20 was resistant to 10 μM of LL-37 after 1 h of attachment to the epithelial cell surface, which was attributed to its capsule and the endotoxin lipooligosaccharide (LOS) (Jones et al., 2009). Nizet et al. discovered that cathelicidin- and CRAMP-resistant GAS was more pathogenic than sensitive GAS in normal mice; chromosomal integration of transposon Tn917 and cathelicidin resistance gene regulator-crgR are associated with an inducible cathelicidin-resistant phenotype of GAS (Nizet et al., 2001). Meanwhile, the S. enterica Typhimurium LT2 strain was resistant to LL-37, resulting from to gene mutations in two-component signal transduction and in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis (Lofton et al., 2013). Clinical pyelonephritic E. coli strains from patients were more highly resistant to LL-37 than cystitic strains; these data suggested that E. coli invasiveness was related to bacterial resistance to cathelicidin (Chromek et al., 2006). Additionally, E. coli strains with mutant curli proteins or mutant cellulose synthase were more resistant to human LL-37 and mouse cathelicidin than their wild-type counterparts (Kai-Larsen et al., 2010).

In addition to the resistance of H. ducreyi to defensins as noted above, this species was found to be resistant to cathelicidin LL-37, which was linked to the SapA transporter (Mount et al., 2010). Additionally, previous studies showed that when MDR A. baumannii was treated with colistin, cross-resistance to host LL-37 increased, which was linked to mutations within pmrB (Spencer et al., 2018; Napier et al., 2013). Noticeably, community-associated (CA)-MRSA USA300 LAC JE2 and USA600 strains exhibited remarkably increased resistance to human LL-37 (Sakoulas et al., 2014) due to defects in electron transport (Kubicek-Sutherland et al., 2017). Additionally, the hemB S. aureus mutant displayed the SCV phenotype, conferring resistance to LL-37 (Glaser et al., 2014).

(iii). Other peptides.

Additional reports have demonstrated the development of resistance to other AMPs, such as magainin, melittin, and lactoferricin B (LfcinB) (Table 2) (Kintses et al., 2019a,b; Andersson et al., 2016). Fernandez and Banemann detected in B. bronchiseptica and B. pertussis resistance to various AMPs, including cecropin (P and B), melittin, magainine-II-amide, and protamine (Fernandez and Weiss, 1996; Banemann and Gross, 1998). These authors found that B. bronchiseptica displayed remarkably more resistance to all AMPs than B. pertussis, which may be due to structural changes in its LPS, specifically, the absence of highly charged O-specific sugar side chains and the presence of a crystalline porin structure mediated by wlbA, wlbL, and bvg gene products (Fernandez and Weiss, 1996; Banemann and Gross, 1998). Shafer et al. also found that the mtr efflux system of N. gonorrhoeae could enhance gonococcal resistance to LL-37 and protegrin-1 (PG-1) (Shafer et al., 1998).

Polymyxin-resistant P. aeruginosa developed cross-resistance to defensins, cathelicidins (including LL-37, CAP18 and SMAP29), and other peptides (such as CP28 and CP29) (Moskowitz et al., 2004; Macfarlane et al., 2000). S. aureus rapidly evolved cross-resistance to melittin, LfcinB, HNP-1, and pexiganan (magainin's derivative, phase III clinical trials) in vitro; four mutated genes — pmtR (ytrA), vraG (bceB), atl, and namA — were identified in each melittin-resistant strain (Habets and Brockhurst, 2012; El Shazely et al., 2020; Samuelsen et al., 2005). The S. enterica Typhimurium DA6192 strain developed cross-resistance to cycloviolacin O2, the cyclotide peptide isolated from Viola odorata after 100–150 passages (Malik et al., 2017). In S. enterica, some mutations (sbmA, waaY, and phoP) in two-component signal transduction pathways and LPS biosynthesis conferred resistance to CNY100HL, WGH, Lfcin, and PR-39; strains carrying these mutations were also cross-resistant to cycloviolacin O2 (Malik et al., 2017; Lofton et al., 2013; Glaser et al., 2014; Pranting et al., 2008; Pranting and Andersson, 2010). Exposure of K. pneumoniae to polymyxin induced cross-resistance to magainin 2 and human defensins (including hBD1, hBD2, and HNP1), which was associated with LPS modification and capsule expression (Llobet et al., 2011). The resistance of the CA-MRSA USA300 LAC JE2 strain to AMPs was assessed by serial passage; the results showed that this strain of S. aureus was highly resistant to CNY100HL, WGH, and PR-39, again resulting from defects in electron transport (Kubicek-Sutherland et al., 2017).

A study systematically assessing the resistance of E. coli to 15 AMPs revealed the prevalence of resistance or cross-resistance in E. coli to membrane-targeting peptides (pexiganan, CAP18, cecropin P1, HBD-3, LL-37, and others) and intracellular-targeting peptides with similar modes of action (apidaecin IB, bactenecin 5, indolicidin, PR-39, and others) (Kintses et al., 2019a,b; Perron et al., 2006). Perturbing the Mla pathway can decrease the net negative charge of the bacterial cell surface, leading bacteria to become resistant to AMPs that target bacterial membranes. Intracellular-targeting AMPs (PR39 and BAC5) can scarcely elicit bacterial cross-resistance to membrane-disruptive human AMPs (LL-37) (Kintses et al., 2019a,b). Similarly, P. fluorescens rapidly developed resistance to pexiganan, an analogue of magainin, after exposure to gradually increasing concentrations of this peptide (Perron et al., 2006).

4. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to current antibacterial agents

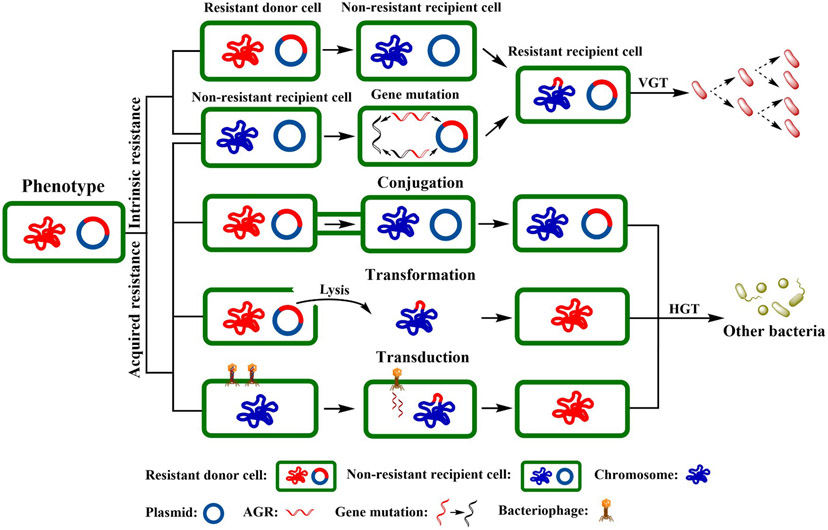

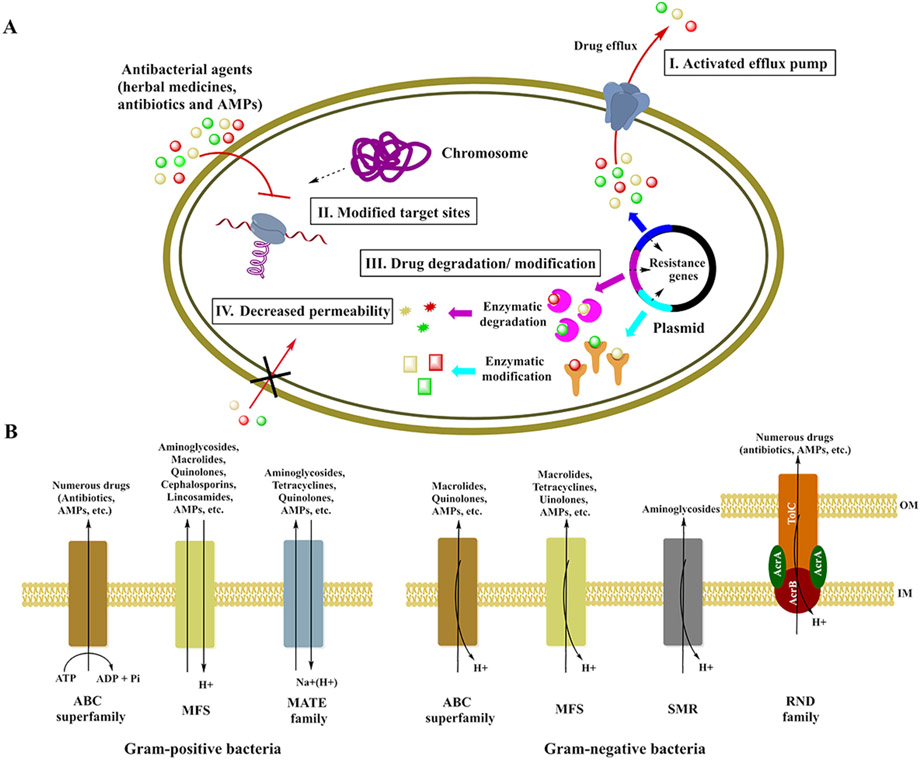

Bacterial resistance to antibacterial drugs can be classified as either intrinsic or acquired resistance. Table 3 describes instances of intrinsic resistance of both pathogenic bacteria and probiotics to conventional antibiotics, including aminoglycosides, β-lactams, carbapenems and quinolones, etc. Meanwhile, inherent ARGs vertically transfer during cell division to the next generation (Fig. 3) (Davies and Davies, 2010; Perry et al., 2014). The most common bacterial mechanisms involved in intrinsic resistance involve efflux pumps and modifying the bacterial outer membrane (Fig. 4A) (Reygaert, 2018). Comparably, acquired resistance occurs via DNA mutation or by horizontal transmission (Fig. 3) and may involve activation of efflux pumps, target modification, and drug modification or inactivation (Fig. 4A) (Regea, 2018; Reygaert, 2018).

Table 3.

Intrinsic resistance of bacteria to conventional antibiotics.

| Types | Bacteria | Antibiotics | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogens | Treponema pallidum | Arsphenamine (Salvarsan) | (Silberstein, 1924) |

| E. coli | Macrolides | (Reygaert, 2018; Liu et al., 2010; Blair et al., 2004) | |

| S. marcescens | Macrolides | (Reygaert, 2018; Blair et al., 2004; Stock et al., 2003) | |

| Bacteroides | Aminoglycosides, β-lactams and quinolones | (Reygaert, 2018) | |

| S. maltophilia | Aminoglycosides, β-lactams, carbapenems and quinolones | (Reygaert, 2018; Nicodemo and Paez, 2007; Alonso and Martínez, 2001; Alonso and Martínez, 2000) | |

| L. monocytogenes | β-Lactams and cephalosporins | (Reygaert, 2018) | |

| Klebsiella spp. | β-Lactams | (Reygaert, 2018; Fu et al., 2007) | |

| Acinetobacter spp. | β-Lactams and glycopeptides | (Reygaert, 2018; Vila et al., 1993; Seifert et al., 1993) | |

| P. aeruginosa | Sulfonamides, β-lactams, chloramphenicols and tetracyclines | (Reygaert, 2018; Deplano et al., 2005; Sellera et al., 2018) | |

| S. enterica Typhimurium | Melittin and cecropin | (Paterson et al., 2009) | |

| S. aureus | Indolicidin, hBD-3 and LL-37 | (Li et al., 2007) | |

| Probiotics | Enterococcus | Aminoglycosides, β-lactams, cephalosporins, lincosamides and glycopeptides | (Li et al., 2020a-c; Reygaert, 2018; Hollenbeck and Rice, 2012; Portillo et al., 2000; Courvalin et al., 1980; Zervos and Schaberg, 1985; Arias et al., 2007) |

| Lactobacillus | Aminoglycosides, glycopeptides, metronidazole and quinolones | (Guo et al., 2017; Courvalin et al., 1980; Jaimee and Halami, 2015) | |

| Bifiobacterium | Aminoglycosides, glycopeptides, metronidazole, quinolones and polypeptides | (Li et al., 2020a-c; Jose et al., 2014; Gueimonde et al., 2010) | |

| L. lactis | Aminoglycosides, quinolones, polypeptides and β-lactams | (Li et al., 2020a-c; Jose et al., 2014; Gueimonde et al., 2010; Hummel et al., 2007) | |

| S. thermophilus | Aminoglycosides and neomycin | (Li et al., 2020a-c; Jose et al., 2014; Gueimonde et al., 2010) |

Note: “R” in the table indicates resistance to the antibiotics.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypes of bacterial resistance to antibacterial agents. Bacterial resistance includes intrinsic resistance (only vertically transferred, taxa-specific) and acquired resistance (vertically or horizontally transferred, taxa-nonspecific). Bacteria can transfer ARGs by horizontal gene transfer (HGT), i.e., conjugation, transformation, or transduction, and by vertical gene transfer (VGT) during genome replication and cell division. HGT is regarded as one of the major mechanisms of ARG transfer and is responsible for the abundance of ARGs. VGT can determine the prevalence of ARGs within a bacterial community (Rana et al., 1991; Pereira et al., 2004; Cox and Wright, 2013).

Fig. 4.

Bacterial mechanisms of resistance to current antibacterial agents. (A) Resistance mechanisms. Bacterial resistance mechanisms include activated efflux pumps, modified targets, degradation or modification of drugs, and decreased permeability to drugs. (B) Bacterial efflux pumps. In Gram-positive bacteria, efflux pumps (such as the ABC superfamily, MFS, and the MATE family) are related to resistance to a few antibiotics and AMPs. Efflux pumps of Gram-negative bacteria include the ABC superfamily, MFS, SMR, and the RND family (Russell et al., 1986; Gunn et al., 1998; Shafer et al., 1998; Saar-Dover et al., 2012; Warner et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2017a; Uddin et al., 2021). IM: inner membrane; OM: outer membrane.

4.1. Activation of efflux pumps

Bacterial efflux pump systems, composed of membrane proteins, are present in bacterial cells and play a key role in resistance to antibacterial agents (including traditional herbal medicines, conventional antibiotics and AMPs); efflux pumps can also be involved in other functions in bacteria such as virulence and pathogenesis (Li and Nikaido, 2009; Alav et al., 2018; Toit, 2017). Efflux pumps can be encoded both within the bacterial chromosome and on plasmids. They involves five major families of efflux systems in bacteria: major facilitator superfamily (MFS), ATP binding cassettes (ABC), small multidrug resistance (SMR), resistance nodulation division (RND), and multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) (Li and Nikaido, 2009). The electrochemical potential of the membrane is an energy source for some efflux pumps. The ABC efflux pump, however, uses ATP hydrolysis for the export of toxic antibacterial agents or biological metabolites from bacterial cells out into the extracellular environment (Fig. 4A) (Mahamoud et al., 2007; Aires and Nikaido, 2005; Zgurskaya and Nikaido, 1999).

Several efflux pumps are constitutively produced at low levels and confer intrinsic resistance under any given condition, whereas others are transiently overexpressed in the presence of a mutation or an effector (i.e., acquired resistance) (Li and Nikaido, 2009). The most abundant efflux pumps are those of the MFS, which are encoded in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and RNDs, which exclusively exist in Gram-negative bacteria. Both types of efflux pumps contribute to resistance to fluoroquinolones, penicillins, macrolides, polymyxin B, tetracyclines, and other conventional antibiotics, as well as some AMPs (Table 4) (Alav et al., 2018; Aygul, 2015; Kabra et al., 2019; Bina et al., 2008; Mateus et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2010). The RND tripartite pump in Gram-negative bacteria is fixed in the inner membrane and comprised of an inner membrane transporter (such as AcrB, AcrD, or MexB), a periplasmic adaptor protein (such as AcrA, MexC, MexA, MexX, or MexE), and an outer membrane channel (such as TolC, OprJ, OprN, or OprM). The RND tripartite pump can catalyze the active efflux of various conventional antibiotics (Daury et al., 2016). For example, E. coli AcrABZ-TolC is composed of four distinct functional proteins: TolC, AcrA, AcrB, and AcrZ (Fig. 4B). TolC, which is similar to a porin, traverses the bacterial outer membrane. The inner membrane protein AcrB, which extends into the periplasmic region, is a permease that utilizes the potential energy of a proton motive force to drive the efflux process. AcrA connects AcrB and TolC and can transfer drug-triggered conformational changes in AcrB within the inner membrane to TolC in the outer membrane. The highly conserved AcrZ protein interacts with the AcrB transmembrane regions, influencing drug recognition (Nikaido, 2009). In the presence of antibiotics, the pump assumes a transport activated state, in which the AcrB trimer is either in a loose (L), tight (T), or open (O) conformation, representing different stages of the transport mechanism; the cycling of AcrB from the L to T to O conformation is driven by proton translocation through the transmembrane domain of AcrB. In the absence of antibiotics, this pump switches to a resting state, in which the AcrB trimer is in the LLL conformation and the TolC central channel is closed (Aron and Opperman, 2018; Wang et al., 2017a). The AcrABZ-TolC RND pump system can extrude most common antibiotics and detergents, thereby lowering their concentration inside the cell, and although AcrB cannot extrude aminoglycosides, a homologous protein, AcrD, can (Wang et al., 2017a; Russell et al., 1986).

Table 4.

Efflux pumps of ESKAPE and their resistance to antibacterial agents.

| ESKAPE | Transporter family | Efflux pump | Antibacterial agents | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococci | MFS and ABC | EmeA, EfmA, EfrAB, MsrC, ABC7 and ABC16 | Antibiotics: macrolides (azithromycin, erythromycin), aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, quinolones (ofloxacin, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin) and lincosamides (lincomycin) | (Santajit and Indrawattana, 2016; Miller et al., 2014; Nishioka et al., 2009; Chouchani et al., 2012) |

| S. aureus | MFS, ABC, MATE and SMR | NorA, NorB, NorC, MsrA, MepA, SepA, MdeA, SdrM, Tet38, QacA and QacB | Antibiotics: quinolones (mupirocin, norfloxacin), macrolides, tetracyclines and β-lactams (nafcillin, penicillin G, methicillin and cefotaxime); AMPs: LL-37, HBD-3 and indolicidin | (Reygaert, 2018; Blair et al., 2004; Falord et al., 2012; Schrader-Fischer and Berger-Bachi, 2001) |

| K. pneumoniae | MFS, RND and SMR | KpnGH, KpnEF and AcrAB-TolC | Antibiotics: chloramphenicols (chloramphenicol), quinolones (nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin) and cephalosporins (cefoxitin) AMPs: cathelicidin and defensins (HNP-1, hBD-1 and hBD-2) |

(Padilla et al., 2010; Srinivasan et al., 2014; Srinivasan and Rajamohan, 2013) |

| A. baumannii | MFS, MATE and RND | SmvA, AbeM, AdeIJK and AdeABC | Antibiotics: macrolides (erythromycin), quinolones and cephalosporins (cephalosporin) | (Vrancianu et al., 2020; Kyriakidis et al., 2021; Su et al., 2005) |

| P. aeruginosa | SMR, MATE and RND | MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, MexEF-OprN, MexXY-OprM and EmrE | Antibiotics: β-lactams (ampicillin), tetracyclines, chloramphenicols (chloramphenicol), quinolones and cephalosporins | (Nikaido, 2009; Li et al., 1995; Poole et al., 1996; Kohler et al., 1997; Rieg et al., 2009; Poole, 2001) |

| Enterobacter | MFS, RND, MATE and ABC | QepA, AcrAB-TolC, AcrEF-TolC, AcrAD-TolC, Mef(B), MacAB-Tolc, MsdAB-TolC, MdfA, MdtK, SmfY, SsmE and SmdAB | Antibiotics: quinolones (norfloxacin), β-lactams, tetracyclines, chloramphenicols and macrolides (erythromycin) AMPs: LL-37, HNP-1, HNP-2, HNP-3, HBD-1, HBD-2 and PG-1 |

(Russell et al., 1986; Padilla et al., 2010; Kohler et al., 1997; Rieg et al., 2009; Mine et al., 1999) |

Other orthologous RND pumps that extrude antibacterial drugs, such as MexAB-OprM and VexAB of K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, Enterobacter, N. meningitides, N. gonorrhoeae, and Vibrio cholerae, share the same architecture as AcrABZ-TolC; they are responsible for resistance to antibiotics as well as a few AMPs (including HNP-1, LL-37, HBD-1, HBD-2, PG-1, CRAMP-38, etc.) (Shafer et al., 1998; Padilla et al., 2010; Joo et al., 2016).

MFS efflux pumps are composed of 12 or 24 total membrane fractions and are associated with the transport of conventional antibiotics, metabolites, and other dyes (Reygaert, 2018). Most MFS efflux pumps are encoded in bacterial chromosomes. TetA, QepA, MefB, and NorA pumps in many Enterobacteriaceae and S. aureus actively extrude tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicols, and macrolides; particularly in E. coli, approximately 50 % of efflux pumps belong to the MFS system (Reygaert, 2018; Blair et al., 2004; Falord et al., 2012).

ABC transporters confer resistance to various antibiotics and AMPs (including vancomycin, nisin, indolicidin, LL-37, bacitracin, and HBD-3) (Table 4) (Li and Nikaido, 2009; Falord et al., 2012). For example, the dual ABC and MFS efflux pumps found in S. pneumoniae play a key role in resistance to cathelicidin that can alter mefE and mel expression and this can confer cross-resistance to LL-37 and macrolides (Zahner et al., 2010). Notably, the multidrug-binding repressor TtgR can regulate the transcription of the RND family transporter TtgABC in Pseudomonas putida; the TtgR-TtgABC system recognizes and extrudes various conventional antibiotics (including chloramphenicol and tetracycline) and herbal flavonoids (such as quercetin, naringenin, and phloretin) (Alguel et al., 2007; Teran et al., 2006). The SapABCDF function in S. enterica may mediate resistance to melittin. AMPs bind to SapA in the periplasm and are transported to the cytoplasm, where they may be degraded by proteases or bind to a regulator, activating resistance determinants (Parra-Lopez et al., 1993).

Some efflux pumps also play an important role in bacterial biofilm resistance and undergo upregulation in biofilms in comparison with bacterial cells in the planktonic state (Gillis et al., 2005). ABC-, MFS- and RND-type efflux pumps were reported to be of great importance for the evolution of resistance to aminoglycosides, quinolones, β-lactams, and other antibiotics in a sub-population of bacterial biofilms, such as those produced by P. aeruginosa, E. coli, A. baumannii, S. enterica, and S. aureus (Li and Nikaido, 2009; Pamp et al., 2008). These resistance patterns are strongly associated with antibiotics actively extruded by the MexXY, MexCD-OprJ and MexAB-OprM pumps, thus linking these pumps to biofilm resistance to antibiotics (Gillis et al., 2005; Chiang et al., 2012).

4.2. Modification of target sites

A few cases of bacterial resistance attributable to target modification involve the mutation of target genes, leading to reduced binding to drugs (herbal medicines, antibiotics and AMPs) (Fig. 4A) (Nikaido, 2009; Su et al., 2018; Marshall et al., 2002). The chromosome or a plasmid may encode the target genes. Bacterial resistance to fluoroquinolones, for example, is elicited by mutations in their target enzymes-DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, which play a role in DNA replication (Hooper, 2000). Ince et al. determined the effects of mutations in topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase in S. aureus on the MICs for gatifloxacin and ciprofloxacin. The MICs of these antibiotics against S. aureus with mutated grlA (A116E and S80F), grlB (R470N), or gyrA (S84L) increased by 2-, 4-, and 8-fold, respectively, indicating that mutations in these fluoroquinolone targets can result in bacterial resistance (Ince et al., 1999). Similarly, the gyrA S. pneumoniae mutants were cross-resistant to sparfloxacin and gatifloxacin; parC gene encodes subunits of topoisomerase IV and point mutations in this gene in S. pneumoniae led to increased MICs for ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, trovafloxacin, and norfloxacin (Ince et al., 1999). Gootz et al. also demonstrated that the parC mutants of S. pneumoniae selected by ciprofloxacin are resistant to both ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin (Gootz et al., 1996). These results support the notion that some target-altered mutants are resistant to fluoroquinolones.

Another example of bacterial high-level resistance ascribed to target mutation is streptomycin resistance conferred by mutations in rpsL, which encodes ribosomal proteins (e.g., RpsL) in E. coli (Pelchovich et al., 2013). Ribosomal mutations in target genes rpsL, rrs, and S12 are also found in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical strains, contributing to resistance to streptomycin, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (Finken et al., 1993; Khosravi et al., 2017). The mechanism of action of antibiotics determines whether this resistance can be transferred between bacteria; in some cases, a plasmid carrying this mutated target gene will not make the recipient completely resistant due to the antibiotic targeting the ribosome (including chromosomally encoded intact RpsL), which can cause cell death (Nikaido, 2009). Additionally, the erm family of genes can confer clinical resistance to macrolides; mutation in 23S rRNA by altering A2058 or its neighboring sites and methylation of A2058 by an adenine-specific methylase-ErmC can cause resistance to lincosamides, macrolides, chloramphenicol, and streptogramins (the MLS antibiotics) in E. coli, S. aureus, and B. subtilis (Nikaido, 2009; Weisblum, 1995).

On the Gram-negative bacterial cell surface, the major modification target sites are located in LPS and LOS, particularly lipid A. These targets are modified by the removal of phosphate groups and the reduction of their net negative charge (Fleitas et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2008). The addition of L-Ara4N, glucosamine, galactosamine, palmitate, acylation, glycine or diglycine to the acyl chain of lipid A and to phosphatidylglycerol (PG) can confer resistance to peptide antibiotics (including colistin and polymyxin B) and AMPs (including indolicidin, LL-37, and defensins) in various bacteria, including S. enterica, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, B. pertussis, V. cholerae, and S. aureus (Fleitas et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2008; Hankins et al., 2012; Shah et al., 2014; Thaipisuttikul et al., 2014; Tamayo et al., 2005; Dalebroux et al., 2014). Meanwhile, modified lipoteichoic acid (LTA) in Gram-positive bacteria is regarded as a common cause of resistance to polymyxin B, colistin, and a subset of cationic AMPs (such as magainin 2, LL37, K9L6, and K6L9), especially through D-alanylation of LTA (Kristian et al., 2005; Saar-Dover et al., 2012). The dlt operon is responsible for encoding the D-alanyl carrier protein ligase, which adds D-alanine to the LTA Gro-P moiety; dlt mutants displayed enhanced sensitivity to AMPs, but overexpression of these genes conferred increased resistance (Neuhaus and Baddiley, 2003). Additionally, the capsular polysaccharides or exopolysaccharides produced by S. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa can directly trap drugs or inhibit their interaction with the cell membrane, leading to resistance to antibacterial agents including polymyxin B, LL-37, HNP-1, HBD-1, and HD-5 (Jones et al., 2009; Campos et al., 2004; Thomassin et al., 2013).

4.3. Modification or degradation of drugs

One general mechanism of resistance is inactivation of the conventional antibiotic or AMP (Nikaido, 2009; Fleitas et al., 2016). Aminoglycosides, such as kanamycin, amikacin, and tobramycin, are inactivated by phosphorylation, acetylation, or adenylation via plasmid- or chromosomeencoded enzymes; this enzymatic activity reduces the net positive charge of the aminoglycoside and leads to resistance in E. coli, Streptomyces fradiae, and other Gram-negative bacteria (Shaw et al., 1993; Bujnakova et al., 2014). Enzymes that hydrolyze β-lactam antibiotics contribute to resistance in Enterobacter, Serratia, and staphylococci (Reygaert, 2018; Vu and Nikaido, 1985).

Another common resistance mechanism is proteolytic degradation (Fig. 4A) (Nikaido, 2009; Fleitas et al., 2016). Some bacteria proteolytically degrade AMPs by expressing proteinases such as SpeB (Fleitas et al., 2016). The omptin family of aspartate proteases present in the outer membrane of enteric bacteria is the most thoroughly researched class of proteases in Gram-negative bacteria (Kukkonen and Korhonen, 2004). Metalloproteases also are involved in Gram-negative bacterial defense against AMPs (Kooi and Sokol, 2009). Some Gram-negative bacteria degrade AMPs, e.g., LL-37 and mCRAMP, inside the bacterial cell after transporting them with specific transporters (Parra-Lopez et al., 1993). Another bacterial resistance mechanism to AMPs involves neutralizing or binding to AMPs. Such a resistant mechanism can be achieved directly by interactions with the bacterial cell surface or released proteins or indirectly by AMP-binding molecules secreted from the host cell surface of pathogenic bacteria (Nizet, 2006).

4.4. Decreased permeability of bacterial cells to drugs

Resistant bacteria, particularly Gram-negative bacteria, can reduce the permeability of the cell outer membrane by changing porin channels located in the membrane; these changes make the membrane less permeable and so prevent the entry of hydrophilic drug molecules, such as tetracyclines, β-lactams, and fluroquinolones (Fig. 4A) (Munita and Arias, 2016; Hasdemir et al., 2004; Kiani et al., 2021). Mutations in certain porins, such as OmpK35, OmpK36 and OprD, have been found in K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter aerogenes, N. gonorrhoeae, and Pseudomonas isolates, conferring resistance to carbapenems, cephalosporins and imipenem (Kiani et al., 2021; Thiolas et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2018a,b; Hamzaoui et al., 2018). As fewer drug molecules enter the bacterial cell, the level of resistance to the drugs increases.

Sequestration, another mechanism of resistance, requires drug-binding proteins, which inhibit the antibiotic from approaching its target. In bacteria that produce the bleomycin (BLM) family of antibiotics, for example, the producing bacteria sequester the antibiotic by expressing the binding proteins BlmA, TlmA, and ZbmA (Sugiyama and Kumagai, 2002). Furthermore, some bacteria can circumvent an antibacterial response by downregulating AMP expression (Fleitas et al., 2016). Generally, most bacteria contain multiple cooperating mechanisms to enable response to the antibacterial agents, including antibiotics or active molecules that bacteria themselves produce (Peterson and Kaur, 2018).

5. The 4A strategies to combat bacterial resistance

To counteract the increasing problem of bacterial drug resistance that then is transferred between humans, animals, and the environment, the following 4A strategies may be adopted based on the One Health concept (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The 4A strategies to counter drug resistance. Effective strategies are urgently needed to combat bacterial resistance, including the prudent use of antibacterial agents, advanced molecular techniques, stringent administration and the need for novel alternatives to antibiotics, such as efflux pump inhibitors, vaccines, bacteriophages, immunoglobulins, AMPs, untapped herbal medicines, and probiotics (Kern and de With, 2012).

5.1. Application

First, we need to prudently manage the application of antibacterial agents under supervision, with a rational and appropriate drug prescribing approach to ultimately eradicate infection.