Abstract

Histoplasma, a genus of dimorphic fungi, is the etiological agent of histoplasmosis, a pulmonary disease widespread across the globe. Whole genome sequencing has revealed that the genus harbors a previously unrecognized diversity of cryptic species. To date, studies have focused on Histoplasma isolates collected in the Americas with little knowledge of the genomic variation from other localities. In this report, we report the existence of a well-differentiated lineage of Histoplasma occurring in the Indian subcontinent. The group is differentiated enough to satisfy the requirements of a phylogenetic species, as it shows extensive genetic differentiation along the whole genome and has little evidence of gene exchange with other Histoplasma species. Next, we leverage this genetic differentiation to identify genetic changes that are unique to this group and that have putatively evolved through rapid positive selection. We found that none of the previously known virulence factors have evolved rapidly in the Indian lineage but find evidence of strong signatures of selection on other alleles potentially involved in clinically-important phenotypes. Our work serves as an example of the importance of correctly identifying species boundaries to understand the extent of selection in the evolution of pathogenic lineages.

INTRODUCTION

Fungal disease is prevalent across the globe. Over 1.7 billion people are affected by fungal infections yearly (Brown et al. 2012; Vallabhaneni et al. 2016; Spallone and Schwartz 2021). Invasive mycoses kill more than one million people every year (Brown et al. 2012). The disease burden of mycoses has increased over the last 20 years, and with the increase of resistance to antifungals, the importance of fungal disease is expected to keep increasing in the years to come (Seagle et al. 2021). One of these mycoses, histoplasmosis, is highly prevalent across global populations (Ashraf et al. 2020) but their actual incidence remains largely unknown as several parts of the world do not require the reporting of histoplasmosis (Nosanchuk et al. 2021). In the United States alone, 3.4 cases per 100,000 people occur yearly (Baddley et al. 2011). The disease is characterized by lung compromise resulting in disseminated mycosis that might turn lethal (Wheat 2003; Kauffman 2007; Benedict et al. 2016; Rodrigues et al. 2020). Immunocompromised individuals routinely suffer from opportunistic histoplasmosis which is often deadly if not properly diagnosed and treated (Hajjeh 1995; Cano and Hajjeh 2001; Hajjeh et al. 2001; Colombo et al. 2011; Adenis et al. 2014).

Histoplasmosis is caused by fungi in the genus Histoplasma, a dimorphic fungus that transitions between mycelia and yeast depending on temperature (Sil 2019). Histoplasma exists in the mycelial phase in the soil, where it produces airborne microconidia or hyphal fragments, which are the infective form that transforms into the pathogenic yeast in vivo that cause disease (Kalra et al. 1957; Woods et al. 2001; Diaz 2018). Histoplasma was originally described as a protozoon from a series of patients suffering an affliction similar to leishmaniasis in Panama by S.T. Darling in 1906 (Darling 1906, 1908). Later inspection of the original slides revealed that the etiological agent was a fungus instead (da Rocha-Lima 1912) reviewed in (Schwarz and Baum 1957) and was initially thought to be a single species (H. capsulatum). Nonetheless, several efforts reported the existence of extensive genetic polymorphism and interstrain phenotypic variability in H. capsulatum (Vincent et al. 1986; Spitzer et al. 1990; Kersulyte et al. 1992; Keath et al. 1992).

Whole genome sequences revealed the existence of at least five different species that are reciprocally monophyletic across the whole genome. A sample largely composed of isolates from the Americas confirmed the existence of at least four species within America and one tentative isolated species from Africa (Sepúlveda et al. 2017). The American phylogenetic species were thus named H. capsulatum sensu stricto (Panama), H. mississippiense (NAm 1), H. ohiense (NAm 2), and H. suramericanum (LAm A). Genome-wide assessments of gene exchange have shown that gene exchange seems to be relatively rare among these species (Sepúlveda et al. 2017; Maxwell et al. 2018), confirming that the level of genetic divergence between these lineages is sufficient to identify genetic discontinuities consistent with species boundaries. Previous multilocus sequence typing suggested the possibility of the existence of even more lineages with the potential of cryptic speciation (Teixeira et al. 2016). Understanding the evolutionary processes that have led to diversification in Histoplasma will necessitate an assessment of genetic variation across geography using whole genomes (discussed in Matute and Sepúlveda 2019; e.g., Sepúlveda et al. 2017; Maxwell et al. 2018). Non-American samples represent an overwhelming minority of the sequenced Histoplasma isolates, posing a significant gap in our understanding of the evolution of the fungus across its global distribution.

In this study we explore the phylogenetic relationships and the population structure of 16 clinical Histoplasma isolates cultured from the same number of patients during a period of 15 years (2006–2020). The patients resided across the whole Indian subcontinent. We used whole genome phylogenetic analysis to demonstrate that these cases are caused by a cluster of isolates that form a differentiated group consistent with an undescribed phylogenetic species. We show that this isolated genetic lineage is closely related to the North America species H. mississippiense and H. ohiense.

Next, we leveraged the differentiation between species of Histoplasma to identify genetic changes specific to the Indian lineage of Histoplasma. In the case of other fungi, selection has driven the evolution of virulence factors (Matute et al. 2008). We find no evidence that selection has driven the evolution of previously identified virulence factors in this lineage of Histoplasma. On the other hand, we find evidence of selection in genes with the potential to be of clinical relevance. The work presented here exemplifies how the combination of species boundaries delimitation and population genetics can identify alleles potentially important for the evolution of virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Long-read sequencing

We assembled a de novo genome for the Histoplasma strain H88 using Oxford Nanopore technologies (ONT) long-reads. We obtained a total of 888,661 reads, with an average length of 1,972.54 bp. The mean coverage from our reads was 61X. Reads were assembled with Flye (Kolmogorov et al. 2019). The assembly was iteratively polished with Racon (Vaser et al. 2017) (three runs) and Medaka (Medaka 2021). We ran Pilon (Walker et al. 2014) for indel corrections four times using the FASTQs files. We quantified the quality and completeness of our resulting assembly using Quast (Gurevich et al. 2013) and BUSCO (Waterhouse et al. 2018) with the fungi and Eurotiomycetes OrthoDB V10 databases (Kriventseva et al. 2018). The assembly was partitioned into 406 contigs; 33% of the genome was assembled in the ten largest contigs and we focused on those for the phylogenetic analysis. We used the whole genome for the rest of the analyses.

Indian isolate genomes

Indian Histoplasma isolates were stocked and maintained in the culture collection of the Medical Mycology Unit, V. P. Chest Institute (VPCI), Delhi India. The isolates were obtained from 16 patients during a period of 2006–2020. Of the 16 isolates, the majority (n=9) were cultured from blood and bone marrow, with the rest from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and tissue biopsy (n=7). The primary isolation of Histoplasma isolates from the clinical specimens were obtained on selective media such as brain heart infusion (BHI) blood agar and yeast phosphate agar (YPA). All the isolates were maintained in the VPCI Medical Mycology Laboratory by subculturing on BHI agar slants at 28°C and stored at 4°C.

Briefly, the DNA was extracted by collecting ~20 mg mycelia from the cultures on BHI agar and then grounded in the presence of liquid nitrogen and DNA extraction buffer (0.2 mol/L Tris-HCl, 10 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5 mol/L NaCl, 1% SDS) in a mortar and pestle, followed by the phenol, chloroform, and isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extraction and ethanol precipitation. Extracted DNA quantity was checked on Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (Thermofisher #Q33238) using DNA HS assay kit (Thermofisher #Q32851) following manufacturer’s protocol. To measure the concentration of the DNA, we placed 1 ul of sample on a Nanodrop 1000 (Thermofisher). The quality of the DNA was confirmed on the 1% agarose gel.

To prepare genomic libraries for each isolate, we used Truseq DNA Nano library preparation kits (Illumina #20015965) using ~250 ng of DNA. The fragmented DNA was further end-repaired, A-tailed and ligated with unique adapters to multiplex at the sequencing stages. We measured the final quality of the library using a Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (Thermofisher #Q33238) and a DNA HS assay kit (Thermofisher #Q32851) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The size of the library inserts was assessed using an Tapestation 4150 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and dsDNA screentape (Agilent, #5067–5365). Next, we diluted each library to 200 pM. Libraries were then loaded on a SP/S4 flowcell (NOVASEQ6000, Illumina) and sequenced for 300 cycles. Table S1 shows the sequencing depth and the SRA numbers for each of these isolates.

Public data

To understand the phylogenetic relationships between the Indian isolates and the rest of the surveyed Histoplasma isolates, we used data generated by previous studies in addition to the data reported here. In total, we downloaded 30 resequenced genomes from multiple Histoplasma species (Sepúlveda et al. 2017). This sample encompassed 10 H. mississippiense isolates, 11 H. ohiense isolates, four H. suramericanum isolates, three H. capsulatum isolates, and two H. capsulatum sensu stricto isolates. Additionally, we used five isolates from the genus Emergomyces (two from E. crescens, two from E. parva, and one from E. pasteruiana,), and five isolates from the genus Paracoccidioides (Mavengere et al. 2020) as the outgroups for our downstream analyses. Table S2 lists the SRA accession numbers for these samples.

Read mapping, filtering, and variant calling

We mapped the whole sample (Histoplasma and outgroups) to the reference genome Histoplasma capsulatum Africa H88 genome (described immediately above) using BWA version 0.7.15 (Li and Durbin 2009). We soft-clipped the reads beyond the alignment to our reference genome, sorted the resulting BAM files, and marked and filtered the duplicate reads using Samtools version 1.11 (Li et al. 2009). We called SNPs using the GATK version 4.1.7.0 HaplotypeCaller function (McKenna et al. 2010; DePristo et al. 2011), and since Histoplasma is haploid (Carr and Shearer 1998) we set the -ploidy option as 1. Then we merged the resulting gvcf files using the GATK GenomicsDBImport function and subsequently jointly genotyped the database with the GATK GenotypeGVCFs function. Finally, we we applied the following filters to the resulting multisample vcf file: QD < 2.0 || FS > 60.0 || MQ < 30.0 || MQRankSum < −12.5 || ReadPosRankSum < −8.0 using GATK VariantFiltration.

Principal component analysis

Our main goal was to determine whether the genetic variation in Indian isolates of Histoplasma was distinct from that found in other lineages. We used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to determine whether allele frequencies differed across potential lineages of Histoplasma. We generated a beagle file with ANGSD (Korneliussen et al. 2014), using the bam files described in the section immediately above, filtering sites with more than 20% missing data, a mapping quality lower than 30, and a base quality lower than 20. We then estimated the individual allele frequencies and computed the covariance matrix. We used the R package PCAngsd (Meisner and Albrechtsen 2018) to decompose the matrix intro eigenvalues and eigenvectors and plotted two principal component (PC) combinations, PC1/PC2 and PC3/PC4, which explained the majority of the genetic variation in our dataset (See Results).

Species boundaries definition

The Indian isolates are a distinct genetic group (See Results). We thus used phylogenetics and population genetics approaches to determine whether they constitute a previously unsampled phylogenetic species. We used the species boundaries framework proposed by (Matute and Sepúlveda 2019) which formulated four criteria to analyze whole genome sequences to detect species boundaries. First, we determined whether the Indian isolates formed a monophyletic group (following Taylor et al. 2000; Dettman et al. 2003a; b). Next, we studied the magnitude of concordance across the genomic windows and coding regions of the genome. Isolated species should show differentiation along the whole genome and not just in a few loci. Third, we assessed whether the differentiation among clades was larger than the extent of genetic variation within species (based on Barraclough et al. 2003; Hughes et al. 2009; Birky 2013). Finally, we quantified the extent of gene exchange between the India lineage and the two more closely related species: H. ohiense and H. mississippiense. We describe the approaches for evaluating each of these criteria as follows.

Criterion 1: phylogenetic relationships

If the India clade is a differentiated phylogenetic species from the rest of Histoplasma clades, then they should form a monophyletic group that is reciprocally monophyletic from all other Histoplasma species (Taylor et al. 2000; Matute and Sepúlveda 2019). To test this hypothesis, we used IQ-TREE 2 (Minh et al. 2020) to construct a maximum likelihood (ML) tree. First, we converted the multisample VCF generated above into a concatenated genome-wide alignment in Phylip format, using the Python script vcf2phylip (Ortiz 2019). The alignment to generate the tree had 4,982,183 variable sites. We then extracted the 10 largest contigs using bcftools (Li et al. 2009), and converted each alignment into Phylip format as above. We then built ML trees from each of the 10 largest contigs and the genome-wide alignment using IQ-TREE 2 (Minh et al. 2020b). Model Finder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al. 2017) determined that the model TVM+F was the best fit to explain substitution patterns in our sample. To estimate branch support, we used 1,000 replicates of ultrafast bootstrap approximation (Hoang et al. 2018). We rooted all trees using five Paracoccidioides isolates from two different species P. restrepiensis and P. brasiliensis sensu stricto (Turissini et al. 2017; Mavengere et al. 2020). We compared each of the trees from the ten largest supercontigs with the tree from the whole concatenated tree using a Robertson-Foulds distance (RF; Bryant and Steel 2009) as implemented in the R function treedist (library phangorn, Schliep 2011). The name of the isolates, their geographical origin, and their SRA numbers, are listed in Table S2.

Criterion 2: gene concordance using genomic windows and BUSCO genes

Phylogenetic reconstructions using concatenated genes can lead to the erroneous inference of genetic relationships (Mendes and Hahn 2018). We thus estimated the extent of genealogical concordance (i.e., whether different loci along the genome showed the same evolutionary history) across the genome in two ways. We used a genomic windows approach in which the H88 genome was split into 276 windows following (Sepúlveda et al. 2017). To extract the genomic windows we used bcftools (options view -r, Li et al. 2009). Second, we used a sample of gene trees from 743 complete orthologs (listed in Table S3). We extracted the regions of each BUSCO from the multisample VCF using Tabix (Li 2011). The sequence of each BUSCO gene was then converted into Phylip format using vcf2phylip (Ortiz 2019). The approach to generate the trees is identical in both cases. We inferred a ML species tree with 1,000 bootstrapped replicates using IQ-TREE 2 (Minh et al. 2020). Finally, we used IQ-TREE 2 to compile either the genome-window trees or the gene trees, and calculate the concordance factors for each clade in the species tree (inferred as described in the section immediately above).

We studied the extent of genomic discordance with higher detail using the program Quartet Sampling (QS; Pease et al. 2018). Both the ML BUSCO species and the tree generated from the concatenated 743 BUSCO genes were formatted in relaxed Phylip format. The premise of this approach is that each internal branch has four branches connected to it, QS randomly selects one taxon from each of the four branches and calculates the likelihood of each of the three possible topological arrangements of the four branches (see Figure. 1 in Pease et al. 2018; and Figure S1). Quartet Concordance (QC) calculates the concordance between the sampled topology and the input tree (in this case the tree inferred with the concatenated alignment) in each sampled branch. Second, we calculated the Quartet Differential (QD) for each node. When there are discordant topologies, QD explores whether discordant topologies are represented equally in a gene tree sample; low QD values indicate that among the two possible discordant topologies, one type is sampled more often than the other. Finally, we calculated the Quartet Informativeness (QI) for each branch, a metric of the level of informativeness of each quartet. Low QI values indicate that most alternative topologies are uninformative.

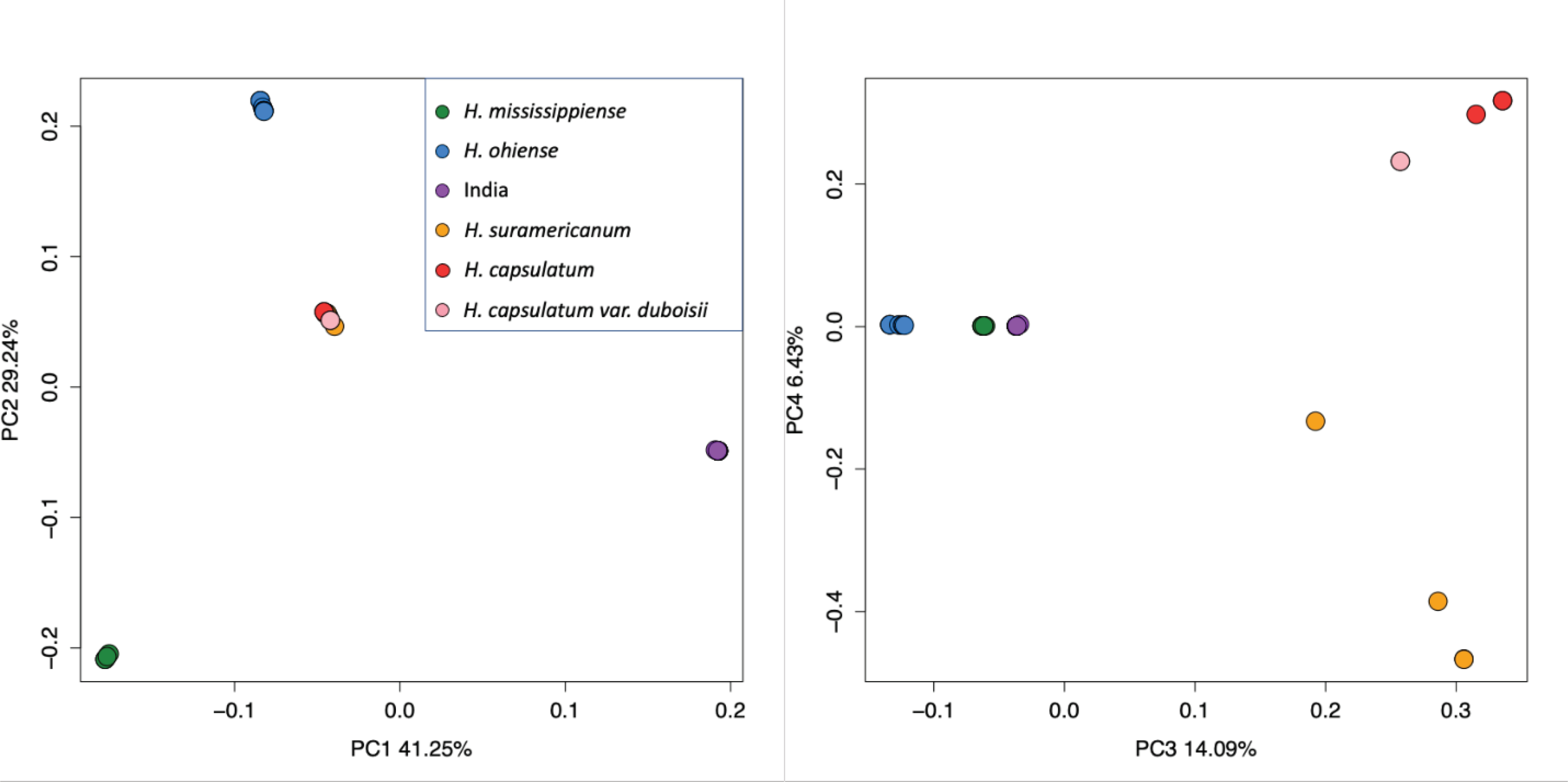

FIGURE 1. Genetic variation is allocated in genetic clusters in the genus Histoplasma.

The principal-component analysis using whole-genome allelic frequencies identifies six discrete clusters. Panel A, principal component 1 and 2 with their respective variance, and panel B, principal component 3 and 4 with their respective variance.

Criterion 3: population genomic analyses

Our studies of genetic variation within Histoplasma and our phylogenetic analyses revealed that the Indian isolates form a monophyletic group (See results). Next, we studied the magnitude of genetic variation within the lineage and how this metric compared to the magnitude of divergence from other species. We used Pixy (Korunes and Samuk 2021) to calculate nucleotide diversity (π) in the Histoplasma isolates from India and genetic differentiation (FST and Dxy) between this lineage and other species of Histoplasma. Pixy includes genotyped invariant sites in the dataset, and accounts for missing data to calculate degree of polymorphism and genetic differentiation. We compared the values of π in each of these species with the magnitude of interclade divergence (Dxy) between the three species. In instances of advanced divergence, Dxy should be much larger than π; this genetic discontinuity has been proposed to signal species boundaries (Birky 2013; Matute and Sepúlveda 2019). We used an Approximative Two-Sample Fisher-Pitman Permutation Test (R function oneway_test, library coin, Zeileis et al. 2008; Hothorn et al. 2019) with 1,000 subsampling iterations to determine whether the π values within each of the species in a pair differed from the Dxy values.

To study local levels of variation along the genome between the Indian lineage and its most closely related species, we used sliding windows of 1 kb to calculate genome wide patterns of π in three Histoplasma lineages (India, H. ohiensis, and H. mississippiense) and FST, and Dxy between India and each of the two North American species. We calculated Tajima’s D (TD) to explore the distribution of the genome in these lineages potentially evolving neutrally (TD = 0). An excess of low-frequency variation leads to TD < 0, and suggests either positive selection or a population expansion. An excess of high-frequency variation leads to TD > 0 which suggests potentially under balancing selection or population contraction (Tajima 1989). Using sliding windows of 100kb, we compared values of Tajima’s D across the genome between the India clade, H. mississippiense and H. ohiense. We used vcftools to calculate Tajima’s D with haploid support (https://github.com/jydu/vcftools).

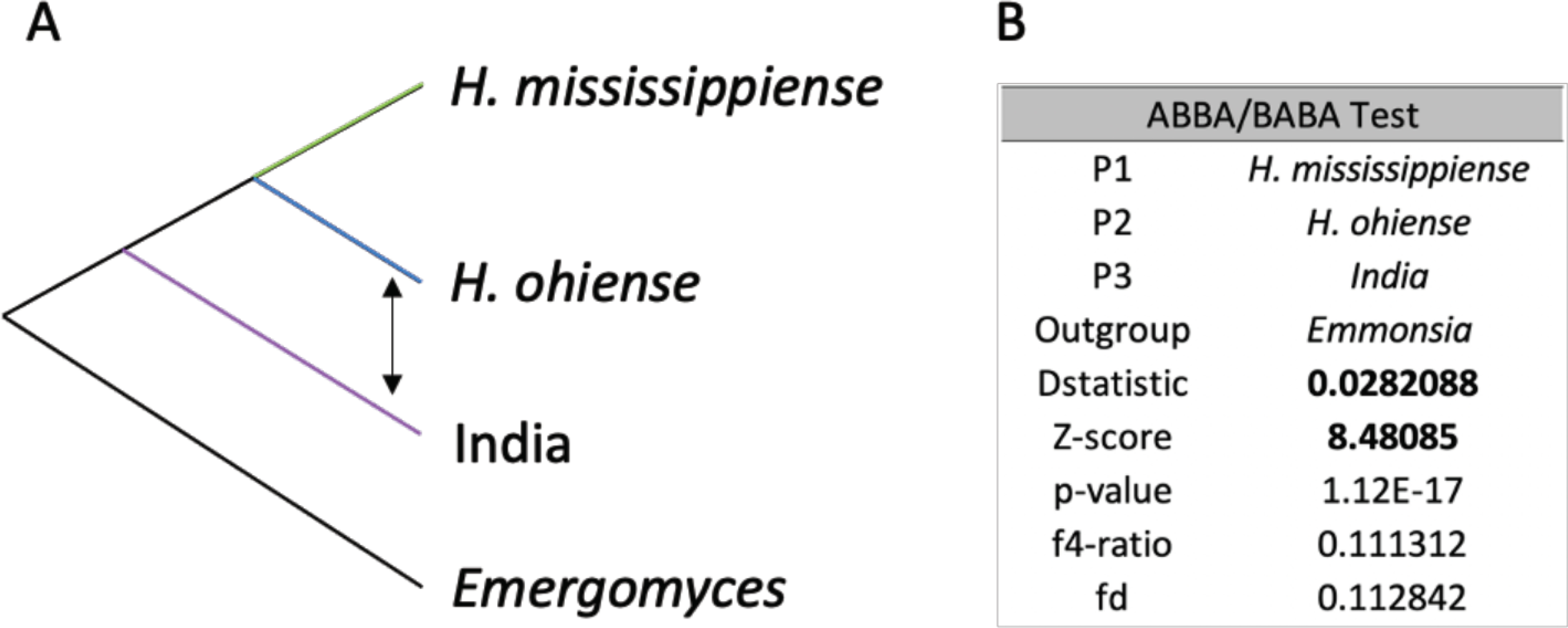

Criterion 4: Introgression Analysis

A major requirement of species delimitations requires the existence of barriers to gene exchange that reduce the likelihood of merging into a single lineage (Matute and Sepúlveda 2019). To get an estimate of the amount of introgression between Histoplasma lineages we used three different variants of Patterson’s D statistic. First, Patterson’s D (Green et al. 2010) considers ancestral alleles (the “As”) and derived alleles (the “Bs”) across the genomes of four taxa: “P1” and “P2” as sister species, “P3” as closely related species, and P4 as an outgroup. In a scenario without gene flow the number of derived alleles shared by “P2” and “P3” but not “P1” (the “ABBAs”), and the number of derived alleles that is shared by “P1” and “P3” but not “P2” (the “BABAs”) should be similar. Introgression from “P3” to “P2” cause an excess of “ABBAs” (and a positive D statistic), and introgression from “P3” to “P1” cause an excess of “BABAs” (and a negative D statistic). Instances of incomplete lineage sorting will lead to a similar number of ABBAs and BABAs (Green et al. 2010). We used the Dtrios program from Dsuite (Malinsky et al. 2021), providing the genome wide ML tree as a the species tree, and calculated Patterson’s D for the H. mississippiense/H. ohiense/India trio using Emergomyces crescens as the outgroup. We used the same approach to calculate a second metric, the f4 ratio. Given a phylogeny, an f4 ratio is a method that calculates the admixture proportion between two taxa (Patterson et al. 2012). For example, let H. mississippiense be “M”, let H. ohiense be “O”, let the India clade be “I”, and let Emergomyces be “E”; Dtrios splits the “I” clade into two subsets ”Ia” and “Ib” and randomly samples alleles from “I” and calculates the ratio between the covariance of allele frequencies (Patterson et al. 2012; Harris and DeGiorgio 2017; Malinsky et al. 2018). If the proportion of ancestry between “O” and “Ia” is α and the proportion of ancestry between “Ia” and “Ib” is 1-α then the f4 ratio is calculated as:

Finally we used the metric fd (Martin et al. 2015) to calculate the local extent of admixture along the genome. Simulation studies have shown that fd is a relatively unbiased and powerful metric to detect introgressed loci (Martin et al. 2015).

Selection scans: Population branch statistics, and Population branch excess

Finally, we studied the influence of selection on allele evolution in genomes of the Indian lineage of Histoplasma. We measured lineage-specific differentiation with the Population Branch Statistic (PBS) (Yi et al. 2010) to scan for signatures of selection. Instances of selection at a given locus will show significantly longer branches for the lineage that has experienced selection. Leveraging information from our whole genome ML tree, we estimated PBS with the program PBScan (Hämälä and Savolainen 2019) using the India, H. mississippiense and H. ohiense trio. PBScan analyzed non-overlapping windows containing 100 SNPs (15Kb long on average) from the beagle file produced with ANGSD to estimate absolute levels of differentiation (Dxy) and transform them into relative divergence times (T) (Hämälä and Savolainen 2019) in each population pair where

TIM = −log(1 − DXY) between the India clade and H. mississippiense

TIO = −log(1 − DXY) between the India clade and H. ohiense

TMO = −log(1 − DXY) between H. mississippiense and H. ohiense

PBScan then applied:

to quantify the magnitude of Dxy at a given locus attributable to the India lineage since its the divergence from H. mississippiense, H. ohiense. Selection acting on the India clade would generate substantial differentiation and show longer branch lengths than H. mississippiense and H. ohiense. To detect branch statistic outliers in the India clade, first we calculated a modified version of PBS that measures the Population branch excess compared to its predicted value (PBE; Yassin et al. 2016). PBE is defined as:

Where TMO is the relative divergence time (see above) between H. mississippiense and H. ohiense, and PBS is the branch statistic for the India clade. Then, we calculated the mean, median, interquartile range, and the 95th and 99th percentiles of the India clade PBE calculated genome-wide. Any locus with a PBE higher than the 95th percentile was considered an outlier. PBE outliers from the India clade represent loci that underwent population-specific sequence differentiation consistent with positive selection (Yi et al. 2010; Yassin et al. 2016).

RESULTS

H88 de novo genome assembly

Our assembly pipeline produced an assembly of 28.67 Mbp, distributed across 406 contigs with an N50 of 517,231 bp (See Table S4). The completeness assessment with BUSCO reported that from 758 fungi orthologs, 744 (98.15%), and from 3,546 Eurotiomycetes orthologs, 3497 (98.5%) are complete and included in our assembly. The BUSCO completeness of our genome showed that from 758 Fungi BUSCOs, 98.1% are present, 0.5% are fragmented, and 1.4% are missing. A similar analysis showed that from 3,546 Eurotiomycetes BUSCOs, 98.6% are present, 0.3% are fragmented, and 1.1% are missing. The previously reported genome from H88 by Sepúlveda et al. (2017) showed a Fungi BUSCO completeness of 97.4% with 1.1% fragmented and 1.5% missing; and a Eurotiomycetes BUSCO completeness of 97.3% with 0.9% fragmented and 1.8% missing. Even though the previous assembly is more contiguous (Table S4), our assembly had more complete genes and for that reason is better suited to analyses of selection on coding genes.

Clinical characteristics of the India isolates

We identified 16 cases of histoplasmosis in India in a period of 15 years. The patients came from widespread regions of India including seven states and Union territories (Northwestern region-Delhi, Haryana, Chandigarh, Maharashtra; Central region, Madhya Pradesh; North Eastern region, Jharkhand and Assam). The majority of the patients (n=9, 63%) had disseminated histoplasmosis, whereas others had pulmonary histoplasmosis, including chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis (n=4), and acute pulmonary infection (n=3). A single case of COVID-19 associated histoplasmosis was diagnosed during the early pandemic 2020. Sixty-eight percent of these cases (n = 11) occurred in apparently immunocompetent patients which is slightly higher from the regular occurrence of histoplasmosis in immunocompetent patients in other cohorts (2-sample test for equality of proportions with continuity correction, X2 = 5.490, df = 1, p-value = 0.019 when compared to Deodhar et al. 2013). In the six remaining cases, patients had diabetes mellitus and COVID-19 underlying disease. None of the patients had a history of travel to endemic areas outside India.

Histoplasma isolates from India form discrete genetic clusters.

To estimate the magnitude of genetic structure within isolates collected in India, we mapped the fastq files to our H88 genome assembly and used the resulting BAM files to do a principal component analysis as implemented in PCAngsd (Korneliussen et al. 2014). Figure S2 shows the proportion of variance explained by each PC, compared to the broken stick model. The first and second Principal components (PCs) explained 41.25% and 29.24% of the variance respectively, and differentiate four clusters within Histoplasma, corresponding to H. mississippiense, H. ohiense (Sepúlveda et al. 2017), and isolates from India as strong independent clusters (Figure 1A, Figure S3). The fourth cluster corresponds to H. suramericanum, H. capsulatum sensu stricto, and H. capsulatum Africa altogether. The third and fourth PCA (14.09% and 6.43% of variance explained, respectively) differentiate six clusters, showing H. suramericanum, Histoplasma capsulatum sensu stricto, and H. capsulatum Africa as independent clusters (Figure 1B). The PCA suggests that the variation in the Indian isolates of Histoplasma is differentiated from all other phylogenetic species in Histoplasma. We thus formally studied whether these isolates have a distinct evolutionary history from all the previously proposed lineages of Histoplasma. We used the framework proposed in (Matute and Sepúlveda 2019) and explored four different criteria for species boundaries definition. We describe the results for each of these studies as follows.

Species boundaries definition

Isolates from India form a monophyletic group.

First, we studied the phylogenetic relationship between the isolates from India and the Histoplasma clades previously reported (Sepúlveda et al. 2017). We rooted the tree with five isolates from the genus Paracoccidioides (Mavengere et al. 2020). Our ML phylogeny revealed two novel patterns. First, we identified six reciprocally monophyletic clusters within Histoplasma, all of which show strong bootstrap support (Figure 2A). Five of these clades correspond with previously identified species (Sepúlveda et al. 2017). The sixth group was exclusively formed by the Indian isolates which formed a distinct, monophyletic clade on their own (Figure 2A). This clustering suggests a single origin for all these samples. Second, the Indian clade formed a monophyletic group with H. mississippiense and H. ohiense. These results suggest that the monophyletic American clade of Histoplasma initially proposed by (Sepúlveda et al. 2017) is an artifact due to lack of systematic sampling from other populations in the world.

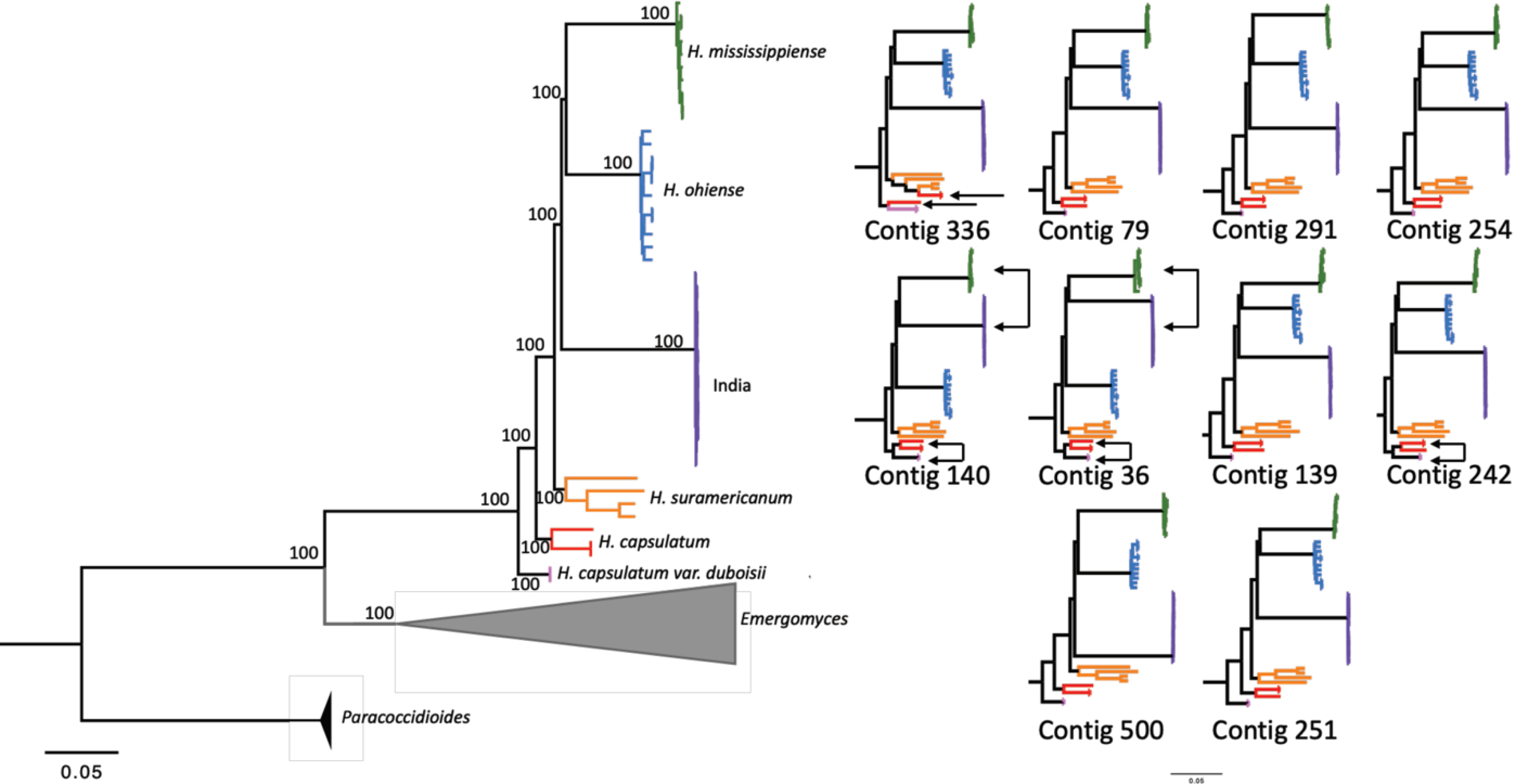

FIGURE 2. Phylogenomic analysis reveals that isolates from India generate a discrete monophyletic group apart from other Histoplasma species.

The phylogram in A was estimated using variable sites from the whole genome and was rooted with Paracoccidioides brasiliensis as the outgroup. The numbers above each branch are bootstrap support. The phylograms in B were estimated with the variation from the 10 largest contigs from our assembly. The trees are arranged left to right and top to bottom from largest to smallest size (contig 336 being the largest and contig 251 being the smallest). Phylograms were also rooted with Paracoccidioides brasiliensis as the outgroup (P. brasiliensis and Emergomyces (Emmonsia) are omitted for visualization).

Next, we explored whether the phylogenetic signal from the concatenated dataset was recapitulated by individual supercontigs. Most of the supercontigs showed a topology that is largely similar to the patterns from the concatenated dataset; in the whole concatenated genome, and in eight of the ten largest contig trees, the India clade was a sister group to the dyad of North American species, H. mississippiense and H. ohiense. Nonetheless, there are notable differences (Figure 2B). Two contigs show the India lineage as closely related to H. mississippiense, with H. ohiense as a sister group (140 and 36). Three contigs (140, 36, and 242) show H. capsulatum ss as two independent branches associated with H. suramericanum and H. c. Africa. Table 1 shows the RF indexes between the ten largest supercontigs and the concatenated tree. Altogether, the concatenated dataset and the individual supercontigs all show that India is a reciprocally monophyletic clade from other Histoplasma species, with some discordance among supercontigs. We explored these differences using a more fine-grained approach as follows.

TABLE 1.

Robertson-Foulds concordance factors between each of the largest supercontigs and the tree generated with the concatenated alignment. The RF distance was converted to a normalized distance that ranges from 0 (complete discordance) to 1 (complete concordance).

| Supercontig | Length (bp) | RF distance | Normalized RF distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 336 | 1,578,516 | 52 | 0.536 |

| 79 | 1,141,980 | 40 | 0.643 |

| 291 | 1,109,290 | 42 | 0.625 |

| 254 | 1,094,252 | 36 | 0.679 |

| 140 | 935,751 | 46 | 0.589 |

| 36 | 820,472 | 42 | 0.625 |

| 139 | 788,355 | 40 | 0.643 |

| 242 | 766,417 | 44 | 0.607 |

| 500 | 731,789 | 28 | 0.75 |

| 251 | 712,987 | 48 | 0.572 |

BUSCO genes trees show reciprocal monophyly but low gene concordance in tree topology

BUSCO genes trees show reciprocal monophyly but low gene concordance in tree topology

Next, we studied whether the signal of strong isolation from India was shared by the whole genome or was driven by a few loci. Individual supercontigs show high levels of concordance in their topology. In particular, they show complete concordance in the reciprocal monophyly of the India clade. We next explored whether this level of concordance was also observed at the genome window level and at the gene level. First, we used a genome-windows approach as proposed by (Sepúlveda et al. 2017; Mavengere et al. 2020). A concordance analysis with 282 windows showed high levels of concordance across most branches consistent with previous reports (Sepúlveda et al. 2017). Almost every genomic window supported the existence of the India lineage as a monophyletic group (Figure 3A). Moreover, the majority of windows (~80%) supported the position of India as an outgroup of the North American dyad.

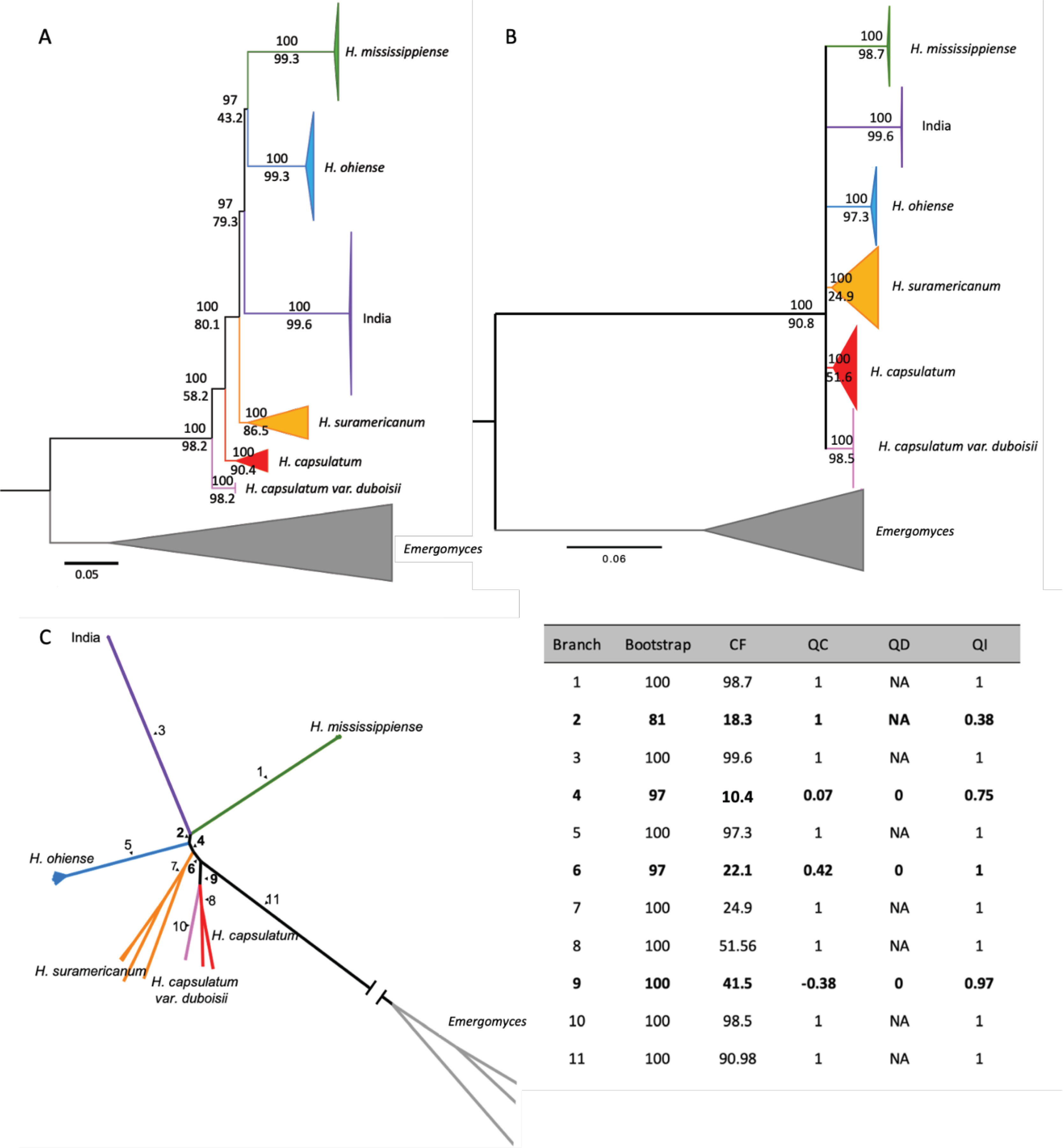

FIGURE 3. Genomic concordance in the genus Histoplasma.

A. Concordance measured using 282 non-overlapping 100 windows in IQ-TREE 2. B. Concordance measured using 743 complete BUSCO orthologs. For both A and B, values in each branch show the bootstrap support (upper value) and the gene concordance factor (gCF, lower value; internal branches with gCF < 50% are omitted). In both analyses, we find six reciprocally monophyletic lineages. The outgroup Paracoccidioides is not shown for image clarity. C. Results from the Quartet sampling analysis. Unrooted phylogram from 743 BUSCO genes with each internal branch enumerated. The results from each internal branch are shown on the table, bolded numbers correspond to internal branches that have 4 taxa connected to it. CF, Concordance Factor; QC, Quartet Concordance; QD, Quartet Differential; and QI, Quartet Informativeness.

Second, we generated individual gene trees for each BUSCO gene and assessed their concordance. We only retained clades for which the level of concordance was over 50% (Figure 3B). Notably, all the phylogenetic species and the India lineage show high levels of concordance and appear as monophyletic units. This result is consistent with our ML tree and with the concordance analysis using genome windows (Figures 2A, 3A, and 3B). Nonetheless, all other older relationships are not conclusively resolved. A quartet analysis, which presents additional metrics of branch support shows similar results (Figure 3C): while we find strong support for all six lineages, BUSCO gene genealogies yield low QC values (a metric of concordance) for internal branches in spite of high levels of informativeness (measured by QI) in most cases. These results suggest that the differentiation between species of Histoplasma at the gene level is strong, but that the signal from conserved genes to differentiate between lineages is lower than that of genomic windows in Histoplasma.

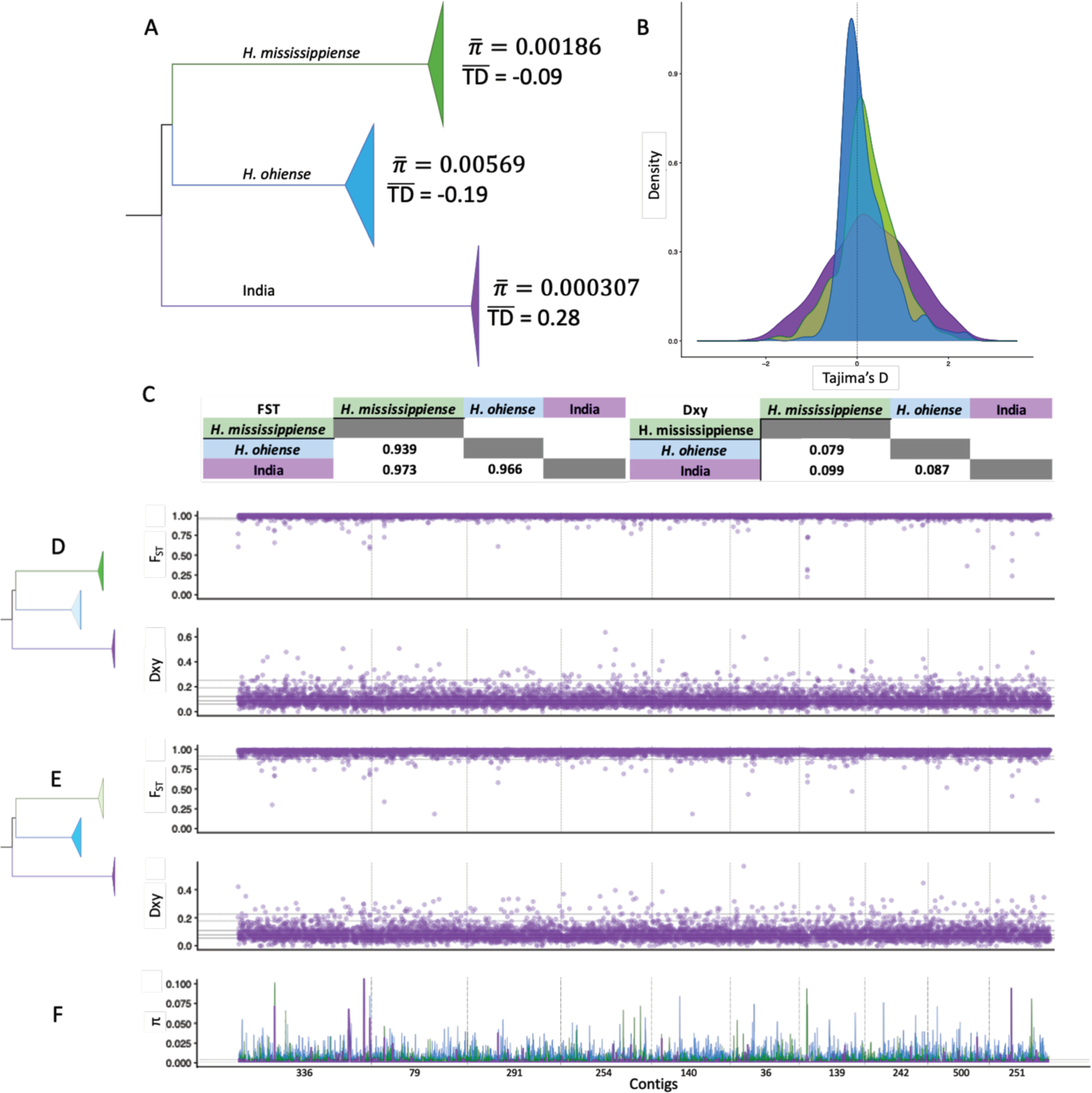

The India clade shows the lowest genetic diversity among any Histoplasma lineage

A third prediction of advanced speciation is that the magnitude of genetic differentiation between loci will be larger than the amount of genetic diversity in a clade (Birky 2013; Matute and Sepúlveda 2019). We thus compared the genetic diversity (π) within India, H. mississippiense, and H. ohiense with the extent of differentiation between lineage pairs (Dxy). We calculated nucleotide diversity (π), fixation index (FST), and divergence (Dxy) (Figure 4 A–F). We found that the clade from India showed the lowest genetic diversity of the three groups (π̅=3.07×10−4, SD=2.82×10−3; Figure 4A), six times lower than H. mississippiense (π̅=1.86×10−3, SD= 4.69×10−3) and 18 times lower than π from H. ohiense (π̅=5.69×10−3, SD=7.79×10−3). In all three pairwise comparisons, Dxy is significantly higher than either value of π suggesting advanced divergence (Table 2).

FIGURE 4. Population genomic analysis reveals genetic differentiation in the Histoplasma isolates from India.

(A) Branch from our genome-wide phylogenetic tree depicting average genome-wide nucleotide diversity (π) and Tajima’s D (TD) from H. mississippiense, H. ohiense, and the clade from India (See also Figure S4). (B) Genome-wide distribution of TD between the three clades from the tree in (A). (C) Average genome-wide variation in FST and Dxy for pairwise comparisons between the three clades. (D) Genome-wide (1-kb windows) distribution of pairwise FST and Dxy between H. mississippiense and the clade from India. (E) Genome-wide (1-kb windows) distribution of pairwise FST and Dxy between H. ohiense and the clade from India. (F) Comparison of the genome-wide (1-kb windows) distribution of π from H. mississippiense (green), H. ohiense (blue), and the clade from India (purple). D,E, and F show the distribution across the 10 largest contigs of our H88 reference genome. Black bold line is the median, gray dashed lines are the interquartile range, black long-dash lines are the 95 and 99 percentiles.

TABLE 2. Genetic distances between species are significantly larger than the amount of intraspecific variation in all pairwise comparisons among Histoplasma species.

We focused on the triad of species composed by the North American and Indian lineages. Other comparisons are shown in (Sepulveda et al. 2017).

| Species 1 | Species 2 | π̅Species1 | π̅Species2 | Dxy | Z value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. mississippiense | H. ohiense | 1.86×10−3 | 5.69×10−3 | 0.119 | 13.915 | < 0.0001 |

| India | H. ohiense | 3.07×10−3 | 5.69×10−3 | 0.129 | 17.156 | < 0.0001 |

| India | H. mississippiense | 3.07×10−3 | 1.86×10−3 | 0.146 | 12.408 | < 0.0001 |

Genomewide Fst estimates also showed a high level of differentiation between lineage pairs (FST = 0.969 India-H. ohiense; FST = 0.98 India-H. mississippiense; FST = 0.95 H. ohiense-H. mississippiense). These results are in line with the results from the PCA (Figure 1) and the phylogenetic trees (Figure 2) which suggest that in this triad of lineages, the genetic variation is largely partitioned among lineages.

Next, we studied the local patterns of variation and differentiation along the genome. Local estimates of FST and Dxy values (calculated in 1kb windows) along the genome revealed that the vast majority of the genome show signals of high divergence between lineages. Only nine windows show low FST (< 0.5) and Dxy (< 0.03) between the India clade and H. ohiense, and three windows show low FST and Dxy between the India clade and H. mississippiense. Windows with low FST and Dxy between the India clade and H. ohiense include the following genes: BSD domain-containing protein (BUSCO ID: 83957at147545; NCBI accession: CP069107, region: 1943686–1946004), Xanthine dehydrogenase (BUSCO ID: 2090at147545; NCBI accession: CP069102, region: 3527354–3532320), hsp70 (BUSCO ID: 11403at147545; NCBI accession: CP069102, region: 4433527–4439015), IQ calmodulin-binding motif domain-containing protein (NCBI accession: CP069104, region: 5008298–5012474), 26S protease regulatory subunit 4(BUSCO ID: 52992at147545; NCBI accession: CP069105, region: 2505990–2508204), and apc11(BUSCO ID: 96837at147545; NCBI accession: CP069102, region: 9049268–9051875). Windows with low FST and Dxy between the India clade and H. mississippiense include the following genes: DNA damage-inducible protein (BUSCO ID: 75029at147545; NCBI accession: CP069103, region: 5341961–5344970), and von Willebrand factor (NCBI accession: CP069105, region: 592878–594440). Regions with decreased FST and Dxy can be caused by multiple processes such as introgression and convergent selection (Beaumont 2005; Noor and Bennett 2009; Cruickshank and Hahn 2014; Rosenzweig et al. 2016). These results suggest that the Histoplasma clade from India is genetically isolated from the sister species H. mississippiense and H. ohiense and most of its genome recapitulates a history of isolation. Collectively, all the patterns of differentiation of the India clade suggest that these isolates form their own phylogenetic species (Matute and Sepúlveda 2019).

Low levels of gene exchange between species of Histoplasma

Finally, lineages at an advanced stage of the species process should show little to no evidence of gene flow. We studied the occurrence of introgression with the ABBA/BABA test to determine whether the India clade had evidence of disproportionate larger rates of introgression with one of the two North American species. Since the India clade is allopatric to both H. mississippiense and H. ohiense, one would expect either no evidence of introgression, or less likely equal rates of introgression with either species. We used the genome-wide ML tree as a guide for Dtrios and tested the hypothesis that there has been introgression between the India clade and either H. mississippiense or H. ohiense (Figure 5A). The resulting D statistic suggests that introgression between the India clade and H. ohiense is more common than between the India clade and H. mississippiense (Figure 5B). The f4-ratio and fd values both suggest that the excess of the proportion of admixture between these two lineages is rather small as the proportion of ancestry of H. ohiense in the India lineage is low (~0.11 %). These results suggest that there is some gene flow between India and H. ohiense, but that introgression between the India lineage and either of the two North American species of Histoplasma is not overwhelmingly large.

FIGURE 5. Patterson’s D shows low occurrence of ancestral admixture between the isolates from India and H. ohiense.

In A the focal trios are shown arranged as in our ML phylogenetic tree, with the patterns of introgression denoted with arrows. Table in B shows the results from the Dtrios analysis. Evidence of introgression between P3 and P2 (positive D statistic, and Z scores >3) is shown in bold.

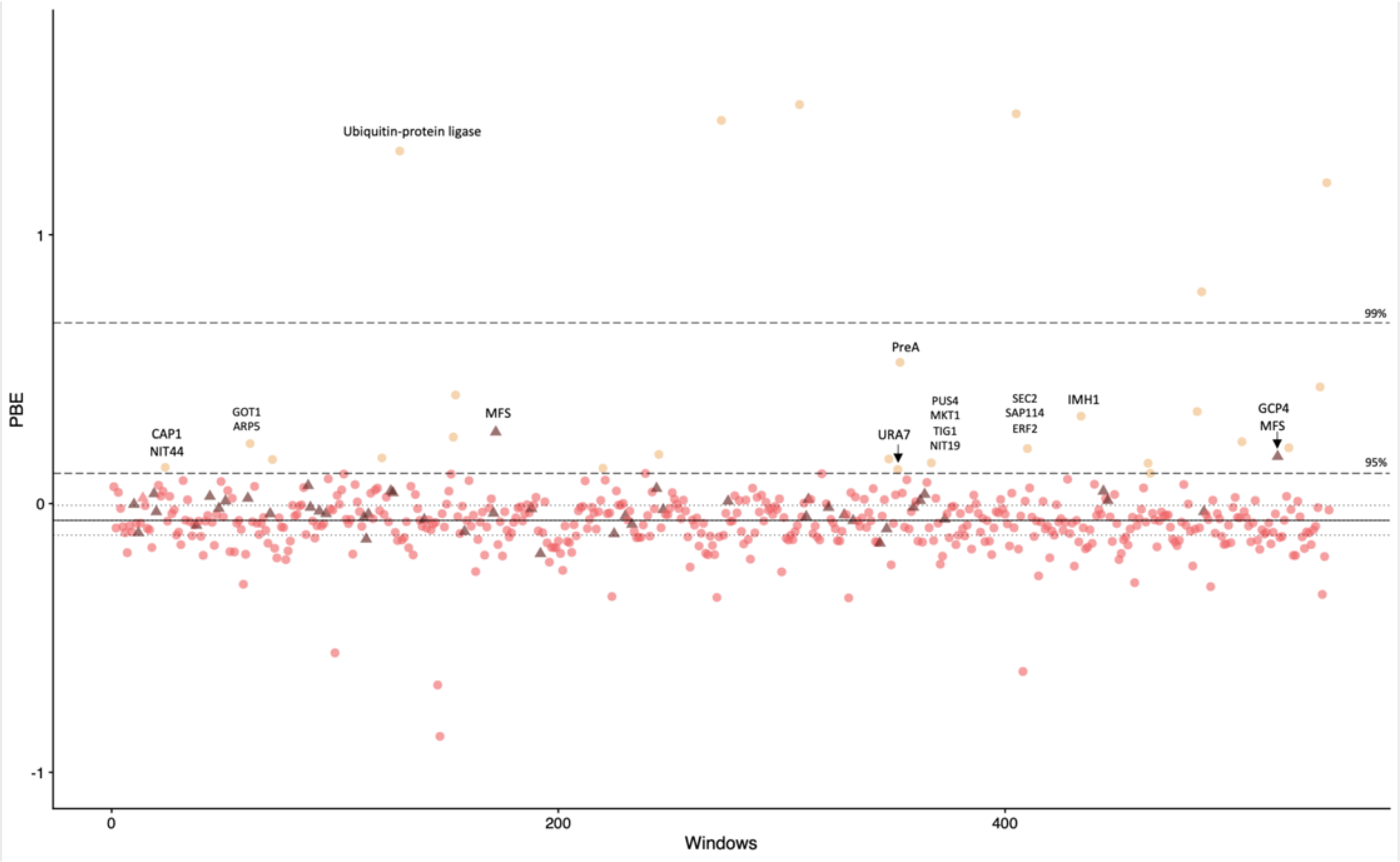

Highly differentiated genes in the India lineage

Finally, we studied what genes were the target of selection in the India group using Population Branch Statistic (PBS; Yi et al. 2010) and Population Branch Excess (PBE; Yassin et al. 2016) estimates. We calculated these two metrics to quantify genetic differentiation specific to the India branch using H. mississippiense and H. ohiense as the other two populations. First, we studied whether selection has acted differently in known virulence factors. We found no difference between the mean PBS value of windows that include a virulence factor and the rest of the genome (Welch Two Sample t-test, t = 1.311, df = 31.648, P = 0.199). Alleles known to be involved in virulence in Histoplasma do not show branch lengths longer than the rest of the genome. For example, the virulence factor alpha-glucan-synthase, ags1, did not show an abnormally long branch (PBE: 0.020, ~83% PBE, Table 3) in the India lineage.

TABLE 3.

Fungal virulence factors and PBE outlier genes (bolded) and their respective PBE values.

| Virulence Factor | PBE India clade | PBE percentile | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| VMA1 | −0.34621 | 1% | Iron homeostasis | (Hilty et al. 2008) |

| HSP82 | −0.19276 | 5% | Response to cellular stresses | (Edwards et al. 2011) |

| Drk1 | −0.15580 | 12% | Required for yeast-phase growth | (Nemecek et al. 2006) |

| gapdh | −0.13763 | 20% | Adhesion to host tissues | Barbosa et al. 2006 |

| H2B | −0.08075 | 40% | Cell surface component | (Albuquerque et al. 2008) |

| Engl | −0.06511 | 50% | Limits detection from phagocytes | (Garfoot et al. 2016, 2017) |

| SRE1 | −0.04945 | 57% | Involved in iron acquisition | (Hwang et al. 2012) |

| ppg1 | −0.04087 | 60% | Putative alpha pheromone | (Laskowski and Smulian 2010) |

| Ryp3 | −0.03837 | 62% | Transition from conidia to yeast | (Webster and Sil 2008) |

| Ryp2 | −0.03755 | 62% | Transition from conidia to yeast | (Webster and Sil 2008) |

| FsFKSI | −0.03141 | 66% | Production of 1,3-β-glucan | (Rappleye et al. 2004; Ha et al. 2006; Edwards et al. 2011) |

| yps-3 | −0.03024 | 66% | Highly-enriched in the yeast phase | (Weaver et al. 1996) |

| Ryp1 | −0.02979 | 67% | Required for yeast phase growth | (Nguyen and Sil 2008) |

| CBP1 | −0.02069 | 69% | Involved in macrophage cell lysis | (Isaac et al. 2015) |

| catP | −0.01883 | 70% | Counters reactive oxygen in the host | (Holbrook et al. 2011) |

| Ctr3 | −0.01813 | 70% | Copper transporter | (Shen et al. 2018) |

| HSP60 | −0.01650 | 72% | Mediates attachment to macrophages | (Long et al. 2003) |

| SOD3 | −0.01397 | 73% | Protection from oxidative stress | (Youseff et al. 2012) |

| Sid1 | −0.01372 | 73% | Counters iron restriction in the host | (Hilty et al. 2011) |

| MAT1 | −0.00806 | 75% | Mating type locus | (Bubnick and Smulian 2007) |

| ags1 | 0.02041 | 83% | Production of α-(1,3)-glucan | (Rappleye et al. 2007; Edwards et al. 2011) |

| gp43 | 0.02684 | 85% | Involved in yeast adhesion to the extracellular matrix | (Carvalho et al. 2005; Torres et al. 2013) |

|

| ||||

| URA7 | 0.12665 | 95% | ||

| CAP1 | 0.13479 | 95% | Elevated expression during infection in Cryptococcus neoformans | (Hu et al. 2008) |

| NIT44 | 0.13479 | 95% | Produces glycogenin, involved in biosynthesis of α-(1,3)-glucan | (Vos et al. 2007) |

| PUS4 | 0.15164 | 96% | ||

| MKT1 | 0.15164 | 96% | ||

| TIG1 | 0.15164 | 96% | ||

| NIT22 | 0.15164 | 96% | ||

| GCP4 | 0.17534 | 96% | ||

| MFS | 0.17534 | 96% | Membrane transporters, involved in multidrug resistance | (K. Redhu et al. 2016) |

| SEC2 | 0.20481 | 97% | ||

| SAP114 | 0.20481 | 97% | ||

| ERF2 | 0.20481 | 97% | ||

| ARP5 | 0.22359 | 97% | ||

| GOT1 | 0.22359 | 97% | ||

| MFS | 0.26555 | 97% | Membrane transporters, involved in multidrug resistance | (K. Redhu et al. 2016) |

| IMH2 | 0.32463 | 98% | ||

| PreA | 0.52516 | 98% | G-protein-coupled pheromone receptor alpha | (Gomes-Rezende et al. 2012) |

| Ubiquitin-protein ligase | 1.31129 | 99% | Involved in ubiquitination reaction | (Liu and Xue 2011) |

One of these genomic windows includes two notable alleles with the potential of being involved in virulence in Histoplasma, NIT44 and cap1. The NIT44 allele in the India lineage shows high differentiation compared to the orthologous alleles in the two North American species. NIT44 produces glycogenin, a nucleating factor that is involved in the polymerization of glucose into linear glycogen, which in turn can be converted to linear α-(1,3)-glucan, one of the virulence factors in Histoplasma (Rappleye et al. 2004, 2007). The same highly-differentiated genomic window encompasses cap1, an allele involved in oxidative stress resistance and a proven virulence factor in Candida albicans (Bahn and Sundstrom 2001). Candida strains with a homozygous deletion for cap1 are avirulent in a mouse model of systemic candidiasis. Little is known about cap1 in Histoplasma. Comparisons of gene expression show that cap1 is more expressed in mycelia than in yeast between mycelia in two different species of Histoplasma (Edwards et al. 2013). Again, whether this allele is involved in virulence in Histoplasma remains unstudied.

Next, we studied whether genes from the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) were also highly differentiated in the Indian lineage. MFS genes have been implicated in drug resistance in multiple Candida species (Costa et al. 2014; Redhu et al. 2016), and are coregulated under conditions of iron limitation in H. capsulatum (Hwang et al. 2008). The mean PBS value for the MFS family is higher than the rest of the genome (t = 4.169, df = 148.89, P = 5.164 ×10−5) which suggests the influence of selection in this gene family along the differentiation of the Indian lineage. Out of the 50 MFS copies in the Histoplasma capsulatum H88 genome (Voorhies et al. 2021), two loci (lI7I53_01150 and I7I53_09273) show an exceptionally long branch in our PBE/PBS scans (Figure 6). Both of these genes remain uncharacterized in Histoplasma.

FIGURE 6. Genome-wide (windows with 100 SNPs) Population branch excess (PBE) from the India clade.

Black bold line is the median, gray dashed lines are the interquartile range, black long-dash lines are the 95th and 99th percentiles. Triangles are genomic windows that include Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) genes.

DISCUSSION

Seminal studies proposed metrics for detecting species boundaries using levels of gene genealogy support (Dettman et al. 2003b; Hughes et al. 2009). The application of metrics devised for a handful of gene genealogies is limited when analyzing genomic datasets, and a new generation of metrics has proposed to leverage the signal that reproductive isolation leaves in the genomes of diverging species (Zhao et al. 2017; Steenkamp et al. 2018; Matute and Sepúlveda 2019). The use of these genetic markers has revolutionized our understanding of fungal diversity and have revealed the existence of previously unrecognized species (Zhao et al. 2017; Steenkamp et al. 2018; Matute and Sepúlveda 2019; Xu 2020). Fungal pathogens are not an exception and DNA markers have revealed the pervasive existence of cryptic species (e.g., O’Donnell et al. 2000; Koufopanou et al. 2001; Rokas et al. 2007; Turissini et al. 2017). Histoplasma is an important fungal pathogen with high prevalence around the world and previous approaches have revealed the existence of multiple species with highly differentiated genomes (Sepúlveda et al. 2017; Maxwell et al. 2018). Yet, few efforts have quantified the extent of genome variation of isolates from outside the Americas. In this report, we study the genetic variation of Histoplasma from an group of histoplasmosis cases in mostly immunocompetent patients in India. We find that all the Indian isolates form a monophyletic group, which in turn poses the possibility of a differentiated and previously unrecognized species. We find that, indeed, the Indian lineage satisfies the requirements to be catalogued as a differentiated phylogenetic species within Histoplasma.

The identification of differentiated species in fungal pathogens has important implications for the understanding of the evolution of virulence. In the case of Coccidioides, two previously unidentified species, C. immitis sensu stricto and C. posadasii, differ in their thermotolerance profile (Mead et al. 2020). Different species of Paracoccidioides differ in their morphology (De Melo Teixeira et al. 2015; Turissini et al. 2017) and their resistance profile to antifungals (Restrepo and Arango 1980; Cruz et al. 2013). Histoplasma species also differ phenotypically as they showed stark differences in their virulence (Sepúlveda et al. 2014, Jones et al. 2020) which in turn suggest that the genetic mechanisms underlying the ability to cause disease have changed along lineage divergence. Determining whether this is a true heritable difference between lineages will require systematic clinical studies. Incorporating clinical, immunological, and epidemiological data that compare the type of histoplasmosis caused by each lineage is the next frontier in understanding the effect of speciation in Histoplasma and whether the existence of multiple lineages has an effect on patient care and treatment.

Our finding that the India clade is genetically differentiated from the previously identified American and African species of Histoplasma poses the question of the role of geography in the radiation of Histoplasma lineages. Histoplasmosis cases are commonly associated with exposure to bat guano (Emmons 1958; Di Salvo et al. 1969; Hoff and Bigler 1981; Bartlett et al. 1982; Dias et al. 2011; Diaz 2018) and bats have been proposed to be associated with the radiation of Histoplasma (Taylor et al. 2005; Teixeira et al. 2016). The idea of a potential co-radiation remains largely speculative as no formal study has addressed the potential coevolution between these potential reservoirs and the fungus. In any case, the magnitude of the genetic differentiation among geographical lineages of Histoplasma suggest that geography has played an important role in the diversification of Histoplasma and a large-scale sampling across the world is sorely needed.

Previous studies in Paracoccidioides, a closely related genus to Histoplasma, revealed that virulence factors often show signatures of natural selection (Matute et al. 2008). We find that in Histoplasma this signature is not pervasive and that selection on known virulence factors have not generally contributed to the divergence of the India clade. For example, SID1 (Hwang et al. 2008), yps3 (Bohse and Woods 2007), and ags1 (Edwards et al. 2011), three of the best characterized virulence factors in the genus show average levels of differentiation in the India lineage. Nonetheless, other alleles with the potential to be involved in virulence show signatures of selection. Even though none of the highly differentiated alleles in the Indian lineage of Histoplasma have been involved in virulence so far, the potential effect of their differentiation in the Indian lineage warrants more investigation. MSF genes, on the other hand, show signatures of selection and two genes of the family are among the most highly differentiated genes in the lineage. Whether these alleles are involved in clinically-relevant phenotypes, and specifically in virulence, remains highly speculative and only functional genetic experiments will reveal whether this hypothesis is correct.

Our work also opens some additional questions. First, the India lineage might have a larger range than the Indian subcontinent. Since our current sampling is limited to this area, we do not know the possible geographic range of the lineage. Second, we find low rates of gene flow between the Indian lineage and the most closely related known species of the group, the two North American species of Histoplasma. Nonetheless, the newly recognized clade seems to be completely allopatric with its known sister species and there is no known instance that might allow for hybridization. India might well exchange alleles with other previously unrecognized lineages that are yet unsampled. This phenomenon, sometimes called ghost admixture, can facilitate gene exchange between chains of lineages. A systematic approach that aims to quantify the extent of introgression across the whole Histoplasma genome should reveal whether any lineage serves as a bridge for allele transfer among lineages with dissimilar geographic ranges. All these caveats point to the future directions that phylogenomics studies in Histoplasma should be undertaken.

More generally, understanding the processes that have driven the divergence of the Histoplasma lineages will require a genomewide assessment of the global genetic diversity of this pathogen as other undescribed species are likely to exist. Kasuga et al. (1999, 2003) used four nuclear and unlinked loci to study the extent of genetic diversity within Histoplasma and suggested the existence of a total of eight lineages with a strong correspondence to geographical locations. Follow-up studies (Teixeira et al. 2016; Rodrigues et al. 2020) increased the number of isolates, but focused on the same four loci, and reported the existence of at least six additional monophyletic groups in South America. None of these clades has been formally examined to assess if they fulfill the requirements of phylogenetic species. The possibility of affordable whole genome sequences with low amounts of input DNA suggests that the time is ripe for a global characterization of the diversity of Histoplasma.

Supplementary Material

IMPORTANCE.

Whole genome sequencing has revolutionized our understanding of microbial diversity, including human pathogens. In the case of fungal pathogens, a limiting factor in understanding the extent of their genetic diversity has been the lack of systematic sampling. In this piece, we show the results of a collection in the Indian subcontinent of the pathogenic fungus Histoplasma, the causal agent of a systemic mycosis. We find that Indian samples of Histoplasma form a distinct clade which is highly differentiated from other Histoplasma species. We also show that the genome of this lineage shows unique signals of natural selection. This work exemplifies how the combination of a robust sampling along with population genetics, and phylogenetics can reveal the precise genetic changes that differentiate lineages of fungal pathogens.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Whole genome sequencing has revolutionized our understanding of microbial diversity, including human pathogens.

Indian samples of Histoplasma form a distinct clade which is highly differentiated from other Histoplasma species.

The genome of this Indian lineage shows unique signals of natural selection.

The combination of a robust sampling along with population genetics, and phylogenetics can reveal the precise genetic changes that differentiate lineages of fungal pathogens.

ACKNOLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AI153523).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adenis A, Nacher M, Hanf M, Basurko C, Dufour J, et al. , 2014. Tuberculosis and histoplasmosis among human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients: a comparative study. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 90: 216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque PC, Nakayasu ES, Rodrigues ML, Frases S, Casadevall A, et al. , 2008. Vesicular transport in Histoplasma capsulatum: an effective mechanism for trans-cell wall transfer of proteins and lipids in ascomycetes. Cellular microbiology 10: 1695–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddley JW, Winthrop KL, Patkar NM, Delzell E, Beukelman T, et al. , 2011. Geographic Distribution of Endemic Fungal Infections among Older Persons, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 17: 1664–1669. 10.3201/eid1709.101987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahn YS, and Sundstrom P, 2001. CAP1, an adenylate cyclase-associated protein gene, regulates bud-hypha transitions, filamentous growth, and cyclic AMP levels and is required for virulence of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol 183: 3211–3223. 10.1128/JB.183.10.3211-3223.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough TG, Birky CW Jr and Burt A, 2003. Diversification in sexual and asexual organisms. Evolution, 57: 2166–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett PC, Vonbehren LA, Tewari RP, Martin RJ, Eagleton L, et al. , 1982. Bats in the belfry: an outbreak of histoplasmosis. American Journal of Public Health 72: 1369–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont MA, 2005. Adaptation and speciation: what can Fst tell us? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20: 435–440. 10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict K, Derado G, and Mody RK, 2016. Histoplasmosis-Associated Hospitalizations in the United States, 2001–2012. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 3. 10.1093/ofid/ofv219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birky CW, 2013. Species Detection and Identification in Sexual Organisms Using Population Genetic Theory and DNA Sequences. PLoS ONE. 8: e52544. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Levitz SM, Netea MG, et al. , 2012. Hidden Killers: Human Fungal Infections. Science Translational Medicine 4: 165rv13–165rv13. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D, and Steel M, 2009. Computing the distribution of a tree metric. IEEE/ACM transactions on computational biology and bioinformatics 6: 420–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubnick M, and Smulian AG, 2007. The MAT1 locus of Histoplasma capsulatum is responsive in a mating type-specific manner. Eukaryotic Cell 6: 616–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MV, and Hajjeh RA, 2001. The epidemiology of histoplasmosis: a review., pp. 109–118 in Seminars in respiratory infections,. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho KC, Ganiko L, Batista WL, Morais FV, Marques ER, et al. , 2005. Virulence of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and gp43 expression in isolates bearing known PbGP43 genotype. Microbes and infection 7: 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa C, Dias PJ, Sá-Correia I, and Teixeira MC, 2014. MFS multidrug transporters in pathogenic fungi: do they have real clinical impact? Frontiers in Physiology 5: 197. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank TE, and Hahn MW, 2014. Reanalysis suggests that genomic islands of speciation are due to reduced diversity, not reduced gene flow. Molecular Ecology 23: 3133–3157. 10.1111/mec.12796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz RC, Werneck SMC, Oliveira CS, Santos PC, Soares BM, et al. , 2013. Influence of different media, incubation times, and temperatures for determining the MICs of seven antifungal agents against Paracoccidioides brasiliensis by microdilution. Journal of clinical microbiology 51: 436–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling ST, 1906. A pProtozoön general infection producing pseudotubercles in the lungs and focal necroses in the liver, spleen and lymphnodes. Journal of the American Medical Association 46: 1283–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Darling ST, 1908. histoplasmosis: a fatal infectious disease resembling kala-azar found among natives of tropical America. Archives of Internal Medicine 2: 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- De Melo Teixeira M, Theodoro RC, De Oliveira FFM, Machado GC, Hahn RC, et al. , 2015. Paracoccidioides lutzii sp. nov.: Biological and clinical implications. Medical Mycology, 52: 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deodhar D, Frenzen F, Rupali P, David D, Promila M, et al. , 2013. Disseminated histoplasmosis: a comparative study of the clinical features and outcome among immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. Natl Med J India 26: 214–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, et al. , 2011. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nature genetics 43: 491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman JR, Jacobson DJ, and Taylor JW, 2003a. A multilocus genealogical approach to phylogenetic species recognition in the model eukaryote Neurospora. Evolution. 57: 2703–2720. 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01514.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman JR, Jacobson DJ, Turner E, Pringle A, and Taylor JW, 2003b. Reproductive isolation and phylogenetic divergence in Neurospora: Comparing methods of species recognition in a model eukaryote. Evolution. 57: 2721–2741. 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Salvo AF, Ajello l., Palmer JW Jr, and Winkler WG, 1969. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from Arizona bats. American Journal of Epidemiology 89: 606–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias MG, Oliveira RZ, Giudice MC, Netto HM, Jordão LR, et al. , 2011. Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from bats in the urban area of São Paulo State, Brazil. Epidemiology & Infection 139: 1642–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz JH, 2018. Environmental and wilderness-related risk factors for histoplasmosis: more than bats in caves. Wilderness & environmental medicine 29: 531–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JA, Alore EA, and Rappleye CA, 2011. The yeast-phase virulence requirement for α-glucan synthase differs among Histoplasma capsulatum chemotypes. Eukaryotic cell 10: 87–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JA, Chen C, Kemski MM, Hu J, Mitchell TK, et al. , 2013. Histoplasma yeast and mycelial transcriptomes reveal pathogenic-phase and lineage-specific gene expression profiles. BMC Genomics 14: 695. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons CW, 1958. Association of bats with histoplasmosis. Public Health Reports 73: 590. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfoot AL, Shen Q, Wüthrich M, Klein BS, and Rappleye CA, 2016. The eng1 β-glucanase enhances Histoplasma virulence by reducing β-glucan exposure. mBio. 10.1128/mBio.01388-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfoot AL, Dearing KL, VanSchoiack AD, Wysocki VH, and Rappleye CA, 2017. Eng1 and Exg8 Are the Major α-Glucanases Secreted by the Fungal Pathogen Histoplasma capsulatum. Journal of Biological Chemistry 292: 4801–4810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Rezende JA, Gomes-Alves AG, Menino JF, Coelho MA, Ludovico P, et al. , 2012. Functionality of the Paracoccidioides mating α-pheromone-receptor system. PLoS ONE 7(10): e47033. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, Maricic T, Stenzel U, et al. , 2010. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science 328: 710–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, and Tesler G, 2013. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29: 1072–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha Y, Covert SF, and Momany M, 2006. FsFKS1, the 1, 3-β-glucan synthase from the caspofungin-resistant fungus Fusarium solani. Eukaryotic cell 5: 1036–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjeh RA, 1995. Disseminated histoplasmosis in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clinical infectious diseases 21: S108–S110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjeh RA, Pappas PG, Henderson H, Lancaster D, Bamberger DM, et al. , 2001. Multicenter case-control study of risk factors for histoplasmosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. Clinical Infectious Diseases 32: 1215–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hämälä T, and Savolainen O, 2019. Genomic patterns of local adaptation under gene flow in Arabidopsis lyrata. Molecular Biology and Evolution 36: 2557–2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AM, and DeGiorgio M, 2017. Admixture and ancestry inference from ancient and modern samples through measures of population genetic drift. Human Biology 89: 21–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilty J, Smulian AG, and Newman SL, 2008. The Histoplasma capsulatum vacuolar ATPase is required for iron homeostasis, intracellular replication in macrophages and virulence in a murine model of histoplasmosis. Molecular microbiology 70: 127–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilty J, George Smulian A, and Newman SL, 2011. Histoplasma capsulatum utilizes siderophores for intracellular iron acquisition in macrophages. Medical mycology 49: 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff GL, and Bigler WJ, 1981. The role of bats in the propagation and spread of histoplasmosis: a review. J Wildl Dis 17: 191–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook ED, Edwards JA, Youseff BH, and Rappleye CA, 2011. Definition of the extracellular proteome of pathogenic-phase Histoplasma capsulatum. Journal of proteome research 10: 1929–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Hornik K, van de Wiel MA, Zeileis A, and Hothorn MT, 2019. Package ‘coin.’ Conditional Inference Procedures in a Permutation Test Framework. [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Cheng P-Y, Sham A, Perfect JR, and Kronstad JW, 2008. Metabolic adaptation in Cryptococcus neoformans during early murine pulmonary infection. Molecular microbiology 69: 1456–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes KW, Petersen RH, and Lickey EB, 2009. Using heterozygosity to estimate a percentage DNA sequence similarity for environmental species’ delimitation across basidiomycete fungi. New Phytologist, 182: 795–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang LH, Mayfield JA, Rine J, and Sil A, 2008. Histoplasma requires SID1, a member of an iron-regulated siderophore gene cluster, for host colonization. PLoS pathogens 4: e1000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang LH, Seth E, Gilmore SA, and Sil A, 2012. SRE1 regulates iron-dependent and-independent pathways in the fungal pathogen Histoplasma capsulatum. Eukaryotic cell 11: 16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac DT, Berkes CA, English BC, Hocking Murray D, Lee YN, et al. , 2015. Macrophage cell death and transcriptional response are actively triggered by the fungal virulence factor Cbp1 during H. capsulatum infection. Molecular microbiology 98: 910–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GS, Sepúlveda VE and Goldman WE, 2020. Biodiverse Histoplasma species elicit distinct patterns of pulmonary inflammation following sublethal infection. Msphere, 5: e00742–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra SL, Borcar MDS, and Rebello ERF, 1957. Histoplasmosis, isolation of the fungus from soil and man. Indian journal of medical sciences 11: 496–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TK, Von Haeseler A, and Jermiin LS, 2017. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nature methods 14: 587–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman CA, 2007. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clinical microbiology reviews 20: 115–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keath EJ, Kobayashi GS, and Medoff G, 1992. Typing of Histoplasma capsulatum by restriction fragment length polymorphisms in a nuclear gene. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 30: 2104–2107. 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2104-2107.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersulyte D, Woods JP, Keath EJ, Goldman WE, and Berg DE, 1992. Diversity among clinical isolates of Histoplasma capsulatum detected by polymerase chain reaction with arbitrary primers. Journal of bacteriology 174: 7075–7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korneliussen TS, Albrechtsen A, and Nielsen R, 2014. ANGSD: analysis of next generation sequencing data. BMC bioinformatics 15: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korunes KL, and Samuk K, 2021. pixy: Unbiased estimation of nucleotide diversity and divergence in the presence of missing data. Molecular ecology resources 21: 1359–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koufopanou V, Burt A, Szaro T, and Taylor JW, 2001. Gene genealogies, cryptic species, and molecular evolution in the human pathogen Coccidioides immitis and relatives (Ascomycota, Onygenales). Molecular Biology and Evolution 18: 1246–1258. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski MC, and Smulian AG, 2010. Insertional mutagenesis enables cleistothecial formation in a non-mating strain of Histoplasma capsulatum. BMC microbiology 10: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, et al. , 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, and Durbin R, 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, 2011. Tabix: fast retrieval of sequence features from generic TAB-delimited files. Bioinformatics 27: 718–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T-B, and Xue C, 2011. The ubiquitin-proteasome system and F-box proteins in pathogenic fungi. Mycobiology 39: 243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long KH, Gomez FJ, Morris RE, and Newman SL, 2003. Identification of heat shock protein 60 as the ligand on Histoplasma capsulatum that mediates binding to CD18 receptors on human macrophages. The Journal of Immunology 170: 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinsky M, Svardal H, Tyers AM, Miska EA, Genner MJ, et al. , 2018. Whole-genome sequences of Malawi cichlids reveal multiple radiations interconnected by gene flow. Nat Ecol Evol 2: 1940–1955. 10.1038/s41559-018-0717-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SH, Davey JW, and Jiggins CD, 2015. Evaluating the use of ABBA–BABA statistics to locate introgressed loci. Molecular biology and evolution 32: 244–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute DR, Quesada-Ocampo LM, Rauscher JT, and McEwen JG, 2008. Evidence for positive selection in putative virulence factors within the Paracoccidioides brasiliensis species complex. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2: e296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute DR, and Sepúlveda VE, 2019. Fungal species boundaries in the genomics era. Fungal Genetics and Biology 131: 103249. 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavengere H, Mattox K, Teixeira MM, Sepúlveda VE, Gomez OM, et al. , 2020. Paracoccidioides Genomes Reflect High Levels of Species Divergence and Little Interspecific Gene Flow. mBio 11: e01999–20. 10.1128/mBio.01999-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell CS, Sepulveda VE, Turissini DA, Goldman WE, and Matute DR, 2018. Recent admixture between species of the fungal pathogen Histoplasma. Evolution Letters 2: 210–220. 10.1002/evl3.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, et al. , 2010. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20: 1297–1303. 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead HL, Hamm PS, Shaffer IN, de M. Teixeira M, Wendel CS, et al. , 2020. Differential thermotolerance adaptation between species of Coccidioides. Journal of Fungi 6: 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medaka, 2021. Oxford Nanopore Technologies. [Google Scholar]

- Meisner J, and Albrechtsen A, 2018. Inferring population structure and admixture proportions in low-depth NGS data. Genetics 210: 719–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes FK, and Hahn MW, 2018. Why Concatenation Fails Near the Anomaly Zone. Systematic Biology. 67: 158–169. 10.1093/sysbio/syx063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, et al. , 2020. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Molecular biology and evolution 37: 1530–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemecek JC, Wüthrich M, and Klein BS, 2006. Global control of dimorphism and virulence in fungi. Science 312: 583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VQ, and Sil A, 2008. Temperature-induced switch to the pathogenic yeast form of Histoplasma capsulatum requires Ryp1, a conserved transcriptional regulator. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105: 4880–4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noor M. a. F., and Bennett SM, 2009. Islands of speciation or mirages in the desert? Examining the role of restricted recombination in maintaining species. Heredity 103: 439–444. 10.1038/hdy.2009.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Kistler HC, Tacke BK, and Casper HH, 2000. Gene genealogies reveal global phylogeographic structure and reproductive isolation among lineages of Fusarium graminearum, the fungus causing wheat scab. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 10.1073/pnas.130193297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz EM, 2019. v cf2phylip v2. 0: convert a VCF matrix into several matrix formats for phylogenetic analysis. URL https://doiorg/105281/zenodo2540861.

- Patterson N, Moorjani P, Luo Y, Mallick S, Rohland N, et al. , 2012. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics 192: 1065–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redhu A, Shah AH, and Prasad R, 2016. MFS transporters of Candida species and their role in clinical drug resistance. FEMS yeast research 16: fow043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappleye CA, Engle JT, and Goldman WE, 2004. RNA interference in Histoplasma capsulatum demonstrates a role for α-(1,3)-glucan in virulence. Molecular Microbiology 53: 153–165. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04131.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappleye C. a, Eissenberg LG, and Goldman WE, 2007. Histoplasma capsulatum alpha-(1,3)-glucan blocks innate immune recognition by the beta-glucan receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 10.1073/pnas.0609848104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo A, and Arango MD, 1980. In vitro susceptibility testing of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis to sulfonamides. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 18: 190–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Lima H. da, 1912. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Blastomykosen, Lymphangitis epizootica und Histoplasmosis. Centralbl. Bakt.(Abt. 1) 67: 233. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues AM, Beale MA, Hagen F, Fisher MC, Terra PPD, et al. , 2020. The global epidemiology of emerging Histoplasma species in recent years. Studies in Mycology 97: 100095. 10.1016/j.simyco.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokas A, Payne G, Fedorova ND, Baker SE, Machida M, et al. , 2007. What can comparative genomics tell us about species concepts in the genus Aspergillus? Studies in Mycology 59: 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig BK, Pease JB, Besansky NJ, and Hahn MW, 2016. Powerful methods for detecting introgressed regions from population genomic data. Molecular ecology 25: 2387–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]