Abstract

BACKGROUND

Blepharoconjunctivitis poses a diagnostic challenge due to its diverse etiology, including viral infections. Blepharoconjunctivits can be acute or chronic, self-limiting, or needing medical therapy.

AIM

To review possible viral agents crucial for accurate differential diagnosis in cases of blepharoconjunctivitis.

METHODS

The PubMed database was searched for records relating to viral blepharoconjunctivitis. The search string generated was “("virally"[All Fields] OR "virals"[All Fields] OR "virology"[MeSH Terms] OR "virology"[All Fields] OR "viral"[All Fields]) AND "Blepharoconjunctivitis"[All Fields]".

RESULTS

A total of 24 publications were generated from the search string. Reference lists from each relevant article were also searched for more information and included in this review. Viral etiologies such as adenovirus, herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are frequently implicated. Adenoviral infections manifest with follicular conjunctivitis and preauricular lymphadenopathy, often presenting as epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. HSV and VZV infections can result in herpetic keratitis and may exhibit characteristic dendritic corneal ulcers. EBV, although less common, can cause unilateral or bilateral follicular conjunctivitis, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. Other potential viral agents, such as enteroviruses and molluscum contagiosum virus, should also be considered, especially in pediatric cases.

CONCLUSION

Prompt recognition of these viral etiologies is essential for appropriate management and prevention of complications. Thus, a thorough understanding of the clinical presentation, epidemiology, and diagnostic modalities is crucial for accurate identification and management of viral blepharoconjunctivitis.

Keywords: Viral, Blepharoconjunctivitis, Herpes simplex virus, Varicella-Zoster, Epstein-Barr

Core Tip: Viral blepharoconjunctivitis, an inflammation of the conjunctiva and eyelids caused by viral infections, represents a significant challenge in ophthalmic practice due to its highly contagious nature and potential for widespread outbreaks. The virus not only directly damages the conjunctival epithelial cells but also induces a robust inflammatory response. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions remains a focus of ongoing research, with implications for developing targeted therapies. The self-limiting nature of the condition, with symptoms generally resolving within two to three weeks, poses a diagnostic challenge, as it often necessitates distinguishing it from other types of conjunctivitis to prevent unnecessary use of antibiotics and to implement appropriate infection control measures.

INTRODUCTION

Overview of blepharoconjunctivitis

Blepharoconjunctivitis is a complex entity that depicts, inflammation of the eyelid and the conjunctiva at once, due to various causes, especially of infectious origin. So in layman's terms, it is a combination of blepharitis and conjunctivitis[1]. The signs and symptoms are similar to those seen in blepharitis, it is worth noting that, chronic blepharitis can trigger conjunctivitis, because of the anatomical juxtaposition between the eyelid structure and the translucent conjunctiva[2]. Signs and Symptoms include pain, conjunctiva injection, eyelid edema and concretion, tearing, ocular irritation, etc. There are different mechanisms or patterns of classification, depending on the cause, course, anatomical location affected, etc. The most common classification pattern used is the American Academy of Ophthalmology, which divides it into anterior and posterior, depending on what anatomical location is affected by the condition[1]. Management is usually poised towards identifying the cause and treatment to relieve symptoms and recurrence. The diagnosis of the various types of blepharoconjunctivitis is important not only because it directs therapy, but also because it gives both the physician and patient an idea about the prognosis[3,4].

Clinical presentation of blepharoconjunctivitis

Blepharoconjunctivitis is an inflammatory response of the eyelids and the conjunctival tissue to physical, chemical, neoplastic, viral or microbial assault[1]. It is usually characterized by the presence of certain clinical features which can also be associated with other ocular surface disorders. Consequently, the common clinical features of blepharoconjunctivitis are considered to be non-specific. Clinically, the etiology mostly defines the type and nature of the presenting characteristics of blepharoconjunctivitis. The nature of clinical presentation may range from severely ulcerated and disrupted eyelid margins to pouting of the meibomian orifices and mild conjunctival injection. Whereas, the former presentation is mostly associated with serious cases such as neoplasm, a viral or virulent microbial invasion, trauma[5-8] etc., the latter mostly suggests a non-sight and non-life-threatening etiology. Moreover, the chronicity of the disease can determine the type and nature of the clinical characteristics at the initial presentation. This is because clinically, most blepharoconjunctivitis can be secondary to a poorly managed blepharitis or any long-standing disease of the eyelids[9].

Definition and classification

The term blepharoconjunctivitis refers to the inflammation of the eyelids and the semi-transparent mucous membrane-like conjunctival covering the anterior surface of the globe and the tarsal plate[1]. The conjunctival membrane is continuous with the stratified squamous epithelium of the eyelid at the mucocutaneous junction of the eyelid margin. Consequently, the close apposition between both tissues makes it easier for a long-standing eyelid inflammation to spread to the conjunctival. The word “Blepharoconjunctivis” derives its origin from the Greek words, “Blepharon” meaning eyelid, and “itis” meaning inflammation[10-12] and the Latin word “conjunctival” meaning to connect. Generally, blepharoconjunctivitis can be categorized based on the cause, chronicity, anatomical position of involvement, standardized photo grading scales, presenting clinical features, and associated signs[1,13]. A correct and adequate classification is necessary to establish the severity, and chronicity as well as formulate the most effective treatment regimen.

Symptoms and signs

The patient's presenting complaints may include epiphora, foreign body sensation, ocular itching, ocular discomfort, burning sensation, and grittiness[14,15]. Symptoms such as a ropy and mucopurulent ocular discharge may be reported in cases of allergies, viral invasion, and a chronic bacterial infestation of the lids respectively. Furthermore, some patients may report ocular redness along with other symptoms[15]. The presenting clinical signs can be influenced by the etiology and associated conditions. Severe itching, phylectenular, follicles, papillae, ropy or a mucopurulent discharge and conjunctival injection, may suggest an allergy, a viral or bacterial infestation[16]. Recurrent chalazia, pouting of the meibomian orifice, and telangiectasia of the eyelid and tarsal plate may be suggestive of meibomian gland dysfunction and posterior blepharitis[17,18]. Whereas, eyelash mating, crusting, scaling, and an erythematous eyelid may demonstrate anterior blepharitis[19,20]. Furthermore, severe conjunctival cicatrization, symblepharon, ocular surface desiccation, trichiasis corneal opacity may suggest a serious underlying systemic disease such as Steven Johnson syndrome, pemphigoid, trachoma etcetera. Blepharoconjunctivitis can also be associated with certain skin conditions such as rosacea[21,22]. This is usually associated with facial papule, erythema, telangiectasia etc. The ulceration of the eyelid margin as well as the disruption of its normal anatomical layout is usually associated with neoplastic lesions involving the eyelid, an aggressive viral infiltration, or virulent microbial infestations[5-8].

Challenges in diagnosis

One challenge to differentials is the sudden emergence of a new virus or a new strain of an existing virus. It is important to accurately put the monkeypox virus at the back of our mind for cases presenting with acute blepharoconjunctivitis, due to its re-emergence, as this will help proffer early solutions, for better outcomes[23]. Treatment for other conditions may also present with blepharoconjunctivitis as a side effect, for example, Kornhauser et al[24] found out during the treatment of a case of glioblastoma multiform with Temozolomide, that blepharoconjunctivitis was a side effect of the treatment regimen. Dupilumab, the monoclonal antibody used in treating eczema and asthma, has also been implicated in triggering blepharoconjunctivitis, especially in patients with atopic dermatitis[25,26].

Blepharoconjunctivitis, inflammation of the eyelids and conjunctiva, can be caused by various infectious agents, including viruses. Of all these conditions, viral blepharoconjunctivitis stands out because it is extremely contagious and has the potential to affect public health greatly. Viral infections, including those caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and other less frequent viruses, significantly contribute to the overall impact of this disorder.

Epidemiological studies emphasize the significance of distinguishing viral blepharoconjunctivitis from alternative sources of conjunctival inflammation. HSV type 1 keratitis impacts almost 1.5 million individuals worldwide, with around 40000 new cases each year. This condition can result in serious complications like corneal ulcers and blindness[27]. This emphasizes the crucial requirement for precise diagnosis and efficient management techniques in order to avoid results that could potentially harm vision. Furthermore, it is important to comprehend viral causes in eye diseases, as VZV-related herpes zoster impacts 10%-20% of individuals who were previously infected, especially those who are 50 years old or older[28,29].

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a virus linked to many eye conditions such as uveitis, keratitis, and conjunctivitis, has a notable impact on a substantial number of people globally[30,31]. Notable occurrences of EBV-related sequelae, such as nasopharyngeal cancer and systemic lupus erythematosus, have been recorded with frequency in countries like China and Saudi Arabia[32,33]. These data emphasize the significance of considering EBV when diagnosing ocular inflammation.

The various causes of viral blepharoconjunctivitis, including uncommon pathogens like molluscum contagiosum, enteroviruses, and monkeypox virus, make diagnosis more difficult and emphasize the importance of comprehensive clinical assessment and specific diagnostic techniques. Enteroviral infections can result in acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis and other disorders affecting the surface of the eye. Additionally, monkeypox has recently been identified as a cause of viral blepharoconjunctivitis[34,35].

This study specifically examines viral-related blepharoconjunctivitis, aiming to clarify the different viral agents implicated, their clinical presentations, diagnostic difficulties, and approaches to treatment. By including epidemiological research into our discussion, we aim to improve our understanding of the significance of precise diagnosis and proper treatment in reducing the problems linked to viral blepharoconjunctivitis. Common viral agents implicated in the differentials are discussed while other less common pathogens are also mentioned. A literature review on the management of these conditions is also attempted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

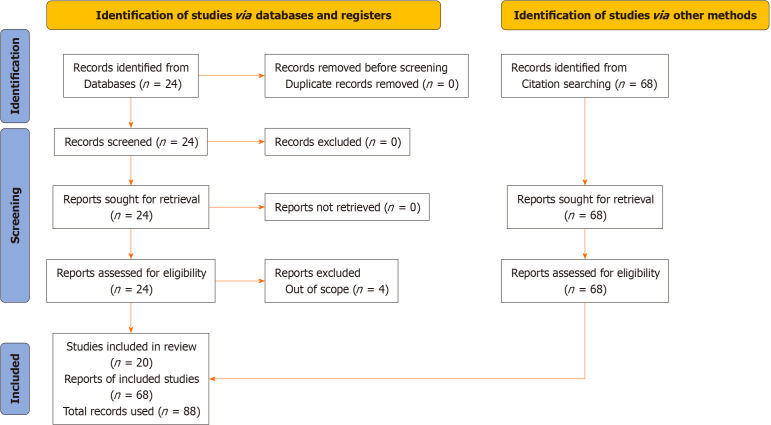

A search of the online PubMed database was conducted using the keywords “viral” and “blepharoconjunctivitis”. The search algorithm generated a search string thus; “("virally"[All Fields] OR "virals"[All Fields] OR "virology"[MeSH Terms] OR "virology"[All Fields] OR "viral"[All Fields]) AND "Blepharoconjunctivitis"[All Fields]”. The results were scrutinized by two authors for relevance. A PRISMA diagram[4] is shown Figure 1, depicting the search strategy. This study included peer-reviewed research publications that met specific criteria, such as being randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, or case reports. This study included individuals of all age groups who were diagnosed with viral blepharoconjunctivitis or other ocular diseases caused by viral infections. Articles that particularly discuss the study of the occurrence, characteristics, diagnostic techniques, and strategies for managing viral blepharoconjunctivitis were included. We only included research published in English to guarantee the correctness and uniformity of the data extraction.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram depicting the search strategy.

Reviews, editorials, comments, and publications that were not based on original research were excluded from consideration. Studies that only examined non-viral causes of blepharoconjunctivitis or did not give detailed information about viral causes were also excluded. Articles that lacked significant data on the epidemiology, clinical symptoms, or management of viral blepharoconjunctivitis were not included. Studies published in languages other than English were eliminated because of the possibility of translation problems and variances in terminologies.

RESULTS

This search returned 24 records. 5 studies were excluded due to being out of scope. The records retrieved ranged from 1973 to 2023. Each valid record was further scrutinized for related literature among their references. A further 68 articles were therefore generated.

DISCUSSION

Viral etiologies of blepharoconjunctivitis

Adenovirus: Epidemiology: Adenoviruses constitute the most common cause of highly contagious conjunctivitis in the world. Viral conjunctivitis affects many people yearly with a percentage of the population exhibiting corneal infiltrates[36]. In fact, in a study, epidemiological analysis of retrospective data which also included 231 conjunctival cases, 205 were diagnosed with viral origin (46.3 % male and 53.7 female), thus highlighting the higher prevalence of viral conjunctivitis in comparison to those of bacterial origin[37]. Another study aimed at evaluating the Human adenoviruses and their serotypes in keratoconjunctivitis patients who attended outpatient clinics at Mansoura Ophthalmic Centre was done. Results therefrom, showed human adenoviruses (HAdV) was detected in 38% of samples, and among the serotypes, HAdV D-8 was the most dominant[38]. Viral conjunctivitis spreads in areas where patients have close contacts such as ophthalmic units of Hospitals, schools, nursing homes, and workplaces[39].

Clinical features: HAdV have been known to cause mild respiratory, gastrointestinal, urogenital, and ocular disease[40]. Adenoviral conjunctivitis which presents mainly as acute follicular conjunctivitis with severe symptoms such as epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC) is caused by human adenovirus[36]. Serotypes of Adenoviruses that cause EKC include Adenovirus 8, 19, and 37[41]. Adenovirus type 3 has been implicated in pharyngoconjunctival fever. Furthermore, a wide range of serotypes have also been presumed to cause follicular conjunctivitis[36]. It is a contagious disease that could be associated with community-acquired or nosocomial infections[42]. Adenoviruses have been shown to result in hemorrhagic enteritis in chickens[43]. They have also been implicated as one of the causes of keratitis[44]. In typical cases, patients complain of unilateral redness, tearing, irritation, and photophobia[36]. Care must be taken to differentiate such complaints from diseases like glaucoma[39,45].

Diagnostic methods: Adenoviruses are classically by an increased titer value of antibodies as the patient progresses from an acute to a chronic stage. Polymerase chain reaction based testing[46].

HSV: The Herpesviridae family, comprising Alphaherpesvirinae, Betaherpesvirinae, and Gammaherpesvirinae subfamilies, further delineates into two major genera within Alphaherpesvirinae: Simplexvirus and Varicellovirus[47]. This viral family exhibits the potential for transmission from the genitals to the eye, leading to severe ocular complications such as blepharoconjunctivitis especially among adults[48]. Primary herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis also typically affects children and adolescents, with some individuals delaying medical attention until they recognize persistent watering as a lasting consequence of the infection[49].

Blepharoconjunctivitis, a prevalent ocular infection among young individuals, also manifests bilaterally in Iberian hares infected with the myxoma virus and is recognized in avian pox cases[50-52]. Moreover, it can arise as a complication associated with unhygienic use of ocular prosthetics or water pollution[53,54]. Additionally, bacterial blepharokeratoconjunctivitis can lead to acute bilateral corneal opacity in children, albeit rarely[55]. In humans, herpetic stromal keratitis and blepharoconjunctivitis, partly attributed to immunopathological responses to HSV-1, involve neutrophil infiltration and cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, IL-12, and interferon-gamma[56]. Tumor-induced blepharoconjunctivitis is observed in immunodeficient patients, like those with Autosomal-recessive hyper-IgE syndrome[57].

Epidemiology: HSV type 1 keratitis affects 1.5 million people globally, with 40000 new cases annually leading to severe eye conditions such as corneal ulcers, which can potentially cause blindness[22]. Although HSV infection is more common in adults, there are reports of it occurring in children through vaginal delivery, leading to ocular diseases[58].

Clinical features: HSV infection of the cornea and ocular adnexa in children can present with several clinical manifestations, including blepharoconjunctivitis, interstitial keratitis, epithelial keratitis, disciform keratitis, neurotrophic keratitis, and stromal keratitis[59]. Herpes simplex virus infection can lead to several ocular diseases, including blepharoconjunctivitis, epithelial keratitis, stromal keratitis, endothelial keratitis, and iritis[60]. The manifestation of these ocular diseases is accompanied by a variety of clinical features. For example, a case of blepharoconjunctivitis was reported in an elderly patient with complete acquired ankyloblepharon, showing clinical signs of preseptal cellulitis[61]. Also, patients who have previously experienced HSV epithelial keratitis are likely to experience increased likelihood of recurrent epithelial keratitis while undergoing acute treatment for HSV stromal keratouveitis[62]. A report by Malik et al[63] indicated that congenital HSV-2 infection can lead to bilateral macular hyperpigmented scars. While most HSV ocular diseases are unilateral, in patients with atopy or compromised immune systems, bilateral herpetic keratoconjunctivitis can occur, leading to a more prolonged course with frequent recurrences and severe complications[64].

Diagnostic methods: HSV 1 infection can be definitively diagnosed through polymerase chain reaction testing of blood and cerebrospinal fluid samples[65]. Oral acyclovir is regarded as a treatment option for HSV infection, even in children, once the diagnosis is confirmed[66]. Clinicians should recognize that smallpox vaccination can cause harmful ocular effects, such as preseptal cellulitis and blepharoconjunctivitis, in both vaccine recipients and their contacts to ensure rapid diagnosis and appropriate treatment[67].

VZV: The VZV is one of the several herpes viruses that are infective to humans. It is the causative organism for shingles(herpes zoster) and chicken pox[68]. While chickenpox is generally a self-limiting illness, complications such as bacterial super infections, pneumonia, and central nervous system involvement can occur, particularly in immunocompromised individuals[69,70].

Epidemiology: Scampoli et al[28] reported that 10%-20% of previously infected individuals were likely to develop VZV-linked herpes zoster with its attendant sequelae later in life, especially above 50 years. Individual risk herpes zoster has been reported at 25%, with a two-fold increase in individuals older than 85 years of age[29].

Clinical features: Following primary infection, VZV establishes latency in sensory ganglia. Reactivation of the latent virus can lead to herpes zoster, commonly known as shingles. Herpes zoster presents as a painful vesicular rash localized to a dermatome innervated by the affected ganglion[71,72]. Post-herpetic neuralgia, a chronic pain syndrome, is a common complication of herpes zoster, particularly in older adults.

Diagnostic methods: Diagnosis of VZV-linked systemic and ocular diseases is by a combination of clinical/physical examinations and serological assays. Patients usually present with a rash that begins as flat lesions and progressed to raised lesions accompanied by a rash. The rashes start from the central body mass and progress to the extremities. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the fluid collected from the pustules confirms the presence of VZV[73].

EBV: EBV, a member of the herpes virus family, is one of the most prevalent viruses in humans[30]. Known primarily for causing infectious mononucleosis (mono), EBV is also linked to various cancers and autoimmune diseases[74,75]. Additionally, EBV is associated with ocular manifestations such as blepharoconjunctivitis, as shown by sero-epidemiologic data and confirmed cases where conjunctival disease appeared as an initial symptom of EBV infection[76].

EBV, also referred to as human herpes virus 4, is a double-stranded DNA virus[77]. It was identified in 1964 by Michael Epstein, Yvonne Barr, and Bert Achong through the study of Burkitt lymphoma cell cultures[78]. This virus primarily targets B lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell integral to the immune system[79]. EBV is notable for its capacity to establish a lifelong latent infection within the host, reactivating intermittently without causing symptoms[80].

The EBV genome is about 172 kilobase pairs in length and encodes approximately 85 proteins[81]. Key among these proteins are the EBV nuclear antigens and latent membrane proteins, which are essential for the virus's persistence in the host and the transformation of infected cells[82].

Epidemiology: The epidemiology of EBV exhibits diverse trends and impacts across various populations. In China, studies reveal a high prevalence of EBV among children, with viral loads rising in the presence of co-infections with bacteria or other viruses, contributing to immune disorders like systemic lupus erythematosus and infectious mononucleosis[32]. In Saudi Arabia, EBV is notably associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), showing a high prevalence of EBV infection in patients and a predominance of genotype I, highlighting the need for further research to understand the burden of EBV-associated NPC[33]. In Russia, EBV infection represents a global challenge, with variations in immunological reactivity due to different pathogens, underscoring the necessity for improved epidemiological surveillance and preventive measures[83]. In Brazil, a study links EBV infection with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases, particularly noting a higher prevalence of active EBV infection in systemic lupus erythematosus patients, especially those undergoing corticosteroid therapy[84].

Clinical features: Ocular manifestations associated with EBV infection are diverse and can affect various structures within the eye. Uveitis stands out as one of the primary presentations, marked by inflammation of the uvea, which encompasses the iris, ciliary body, and choroid[85]. This inflammation typically presents with symptoms like eye redness, pain, and sensitivity to light, and blurred vision, with anterior uveitis being more prevalent in EBV-related cases[31]. Although less common, posterior uveitis affecting the retina and choroid can also occur[86], and EBV-associated uveitis may manifest unilaterally or bilaterally and may recur[87].

Beyond uveitis, EBV infection has been linked to various other ocular complications, including keratitis, conjunctivitis, and optic neuritis[88,89]. Keratitis, involving inflammation of the cornea, can range from mild epithelial defects to severe necrotizing forms[88]. Conjunctivitis, characterized by conjunctival redness and discharge, may coincide with systemic EBV symptoms like fever and malaise[89]. Optic neuritis, affecting the optic nerve, can cause vision impairment and eye pain exacerbated by movement.

Less common but still significant ocular conditions associated with EBV infection include retinal vasculitis, retinitis, and optic neuropathy[90-92]. Retinal vasculitis involves inflammation of retinal blood vessels, potentially leading to vascular occlusion and ischemic retinopathy[90]. Retinitis, characterized by features like retinal hemorrhages and exudates, can also occur[91]. Optic neuropathy related to EBV infection may present with optic disc swelling or optic atrophy, resulting in visual field defects and decreased acuity[92].

Given the range and severity of EBV-associated ocular manifestations, clinicians must maintain a high level of suspicion for EBV in patients presenting with ocular inflammation, especially alongside systemic symptoms suggestive of viral infection. Early recognition and proper management of these EBV-related eye conditions are crucial for preventing vision-threatening complications and preserving visual function.

Diagnostic methods: The diagnosis of ocular conditions associated with EBV often involves a combination of clinical evaluation, serological testing for EBV-specific antibodies, PCR assays for viral DNA, and ocular imaging techniques such as fundoscopy, optical coherence tomography, and fluorescein angiography[93-98]. Treatment strategies for EBV-associated eye diseases typically focus on managing inflammation and controlling viral replication. Topical or systemic corticosteroids may be prescribed to alleviate ocular inflammation, while antiviral agents such as acyclovir or valacyclovir may be used to suppress viral replication[99,100].

Other potential viral agents: Although most cases of viral conjunctivitis have been known to be associated with adenovirus[101] however, some of the most contagious forms of blepharoconjunctivitis are linked to certain enterovirus stereotypes[34].

Enterovirus: Enterovirus is a genus consisting of several other species and subspecies of viruses such as coxsackieviruses, enteroviruses, rhinoviruses, polioviruses and echovirus. It belongs to the viral family Picornaviridae and is renowned for being amongst the most Rampant pathogens on earth[102]. Blepharoconjunctivitis secondary to certain strains of enterovirus is characterized by varying degrees of subconjunctival hemorrhage, conjunctival hyperemia, tarsal conjunctival follicles, profuse tearing, and lid edema. Certain patients may report itching before the onset of conjunctivitis[103]. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis is a highly contagious ocular surface disease that is caused by enterovirus 70 and coxsackievirus A24[104]. Although the condition is relatively benign and resolves within five to seven days it may associated with significant ocular pain if a superficial punctate keratopathy develops. Other less common viral etiology of blepharoconjunctivitis include molluscum contagiosum virus, measles, mumps, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus.

Molluscum contagiosum: this is a DNA virus that belongs to the poxviridae family. It causes dermatosis mostly in the pediatric demographics, sexually active and immunocompromised individuals[105]. Molluscum contagiosum is a round pinkish umbilicated skin papule that can be found on epithelial surfaces including the skin of the face and eyelids[106]. Furthermore, transmission is usually by contact, fomites, and autoinoculation[107], and It is known for its affinity for epithelial tissue, this is known as “tropism”[108]. Molluscum contagiosum dermatosis is usually self-remitting however, treatment may be required for genital lesions and immunocompromised individuals[104]. Blepharoconjunctivitis may arise secondary to longstanding ocular molluscum contagiosum, which is more common in HIV and pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis[109]. Commonly associated signs include follicular conjunctivitis, mucopurulent discharge, subepithelial epithelial infiltrates, and corneal pannus[110].

Measles and mumps: These are both single-stranded RNA viruses with enveloped virions and equipped with the ability to replicate in a host's cytoplasm. Both cause very contagious diseases in humans although, measles and mumps are preventable with the MMR vaccine[111] both can lead to encephalitis and other potentially life-threatening complications[112-114]. Whereas, measles is generally characterized by upper respiratory symptoms (coryza), cough, and conjunctivitis, Mumps on the other hand is characterized by general symptoms such as pyrexia, tiredness, cephalalgia, malaise, and anorexia which is followed by swelling and inflammation of the parotid[115]. Mump and measles blepharoconjunctivitis are mostly characterized by conjunctival follicles, superficial vessel engorgement, conjunctival hyperemia, pseudomembranes, and photophobia[116].

Monkey pox virus: Scandale et al[35] implicated the monkeypox virus as a causative agent of viral blepharoconjunctivitis; reporting a unilateral ocular manifestation, with associated epidermal findings. The examination pointed to a diagnosis of Viral blepharoconjunctivitis in that eye, secondary to a monkeypox infection[23]. This can progress to necrotizing keratoconjunctivitis which would result in significant orbital morbidity[117]. While the monkeypox virus may be self-limiting in its mild forms, antiviral medication is needed in its more serious presentations[118].

Myxoma virus: This is a virus from the genus Leporipoxvirus[119]. It is commonly carried by its murine host and transmitted by the mosquito insect which is endemic to Sun-Saharan Africa[120,121]. Farsang et al[122] reported on myxomatosis presenting with conjunctivitis as one of its symptoms in a study out of central Europe.

Table 1 is has been included to show and summarize a differential diagnoses between common causes of viral blepharoconjunctivitis.

Table 1.

Distinguishing features of blepharoconjunctivitis caused by different viruses, including herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, adenovirus, and enterovirus

|

Feature

|

Herpes simplex virus

|

Varicella-zoster virus

|

Adenovirus

|

Enterovirus

|

| Common symptoms | Unilateral conjunctival redness, itching, vesicular lesions on eyelids, dendritic ulcers on cornea | Painful vesicular rash localized to a dermatome, conjunctivitis | Acute conjunctivitis with profuse, watery discharge, preauricular lymphadenopathy | Conjunctival hyperemia, lid swelling, profuse tearing, possible subconjunctival hemorrhage |

| Discharge type | Clear or watery; may have epithelial defects | Clear or serous; often accompanied by skin lesions | Watery; often profuse and accompanied by preauricular lymphadenopathy | Watery or serous; can be associated with hemorrhage |

| Onset | Sudden, often following reactivation of latent infection | Sudden, often follows a history of shingles or chickenpox | Acute onset, highly contagious | Acute onset, highly contagious |

| Preauricular lymphadenopathy | Rare | Rare | Common | Rare |

| Corneal involvement | Frequent; dendritic ulcers visible on fluorescein staining | Possible; less common but can have corneal involvement | Rare | Rare |

| Associated systemic symptoms | Fever, malaise, possibly cold sores | Painful rash in a dermatome, fever | Often accompanied by upper respiratory symptoms | May have systemic symptoms like fever, malaise, or rash |

| Diagnostic tests | PCR for HSV DNA, viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody | PCR for VZV DNA, viral culture | PCR for adenoviral DNA, viral culture | PCR for enteroviral RNA, viral culture |

| Immunoassays | Detect HSV-specific antigens or antibodies | Detect VZV-specific antigens or antibodies | Detect adenoviral antigens or antibodies | Detect enteroviral antigens or antibodies |

| Corneal examination | Dendritic ulcers, punctate epithelial keratopathy | Vesicular rash on eyelids and possible corneal involvement | Typically, no corneal involvement | Rarely involves the cornea |

| Epidemiology | Common, especially in individuals with a history of cold sores or HSV infections | Less common, typically in individuals with recent shingles or chickenpox | Highly contagious; common in children and adults | Less common, often associated with outbreaks |

| Management | Antiviral medications (e.g., acyclovir), topical or systemic steroids for inflammation | Antiviral medications, supportive care for rash and pain | Supportive care, antihistamines, sometimes antiviral treatment | Supportive care, analgesics for discomfort |

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; HSV: Herpes simplex virus; VZV: Varicella-zoster virus.

Diagnostic modalities for viral blepharoconjunctivitis

Distinguishing between viral infection-related blepharoconjunctivitis and blepharoconjunctivitis caused by other factors requires a meticulous evaluation of clinical symptoms, patient history, and diagnostic tests. The clinical presentation is fundamental. Regarding blepharoconjunctivitis associated with viral infection, the initiation and manifestations are important. Viral blepharoconjunctivitis typically manifests with an abrupt onset. Typical symptoms consist of redness in the conjunctiva, discharge of watery fluid, and a sensation of itching. Different viral strains may exhibit unique characteristics. HSV is a viral infection with typical unilateral manifestation characterized by blister-like sores on the eyelids or conjunctiva. There is a possibility of having dendritic ulcers on the cornea.

VZV is a pathogen, and the condition typically manifests as a painful vesicular rash that is limited to a specific area of the skin, known as a dermatome. It is sometimes accompanied by inflammation of the conjunctiva, which is the thin membrane that covers the front surface of the eye. Adenovirus infection frequently leads to a sudden and highly infectious inflammation of the conjunctiva, characterized by a copious and watery discharge. Linked to preauricular lymphadenopathy. Enteroviruses can lead to a condition called acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, which is characterized by redness and swelling of the conjunctiva and eyelids.

The generalized symptoms with different agents can vary. Viral infections might be accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, or a prodromal rash. Causes not related to viruses can give different symptoms. Allergic blepharoconjunctivitis frequently occurs on both sides, accompanied by irritation, tearing, and redness of the conjunctiva. May have a previous record of exposure to allergens and frequently exhibit a viscous discharge. Bacterial blepharoconjunctivitis typically exhibits a purulent discharge that is particularly intense in the morning. It can occur on one side or both sides and may be accompanied by the formation of crusts on the eyelids. Chemical irritants commonly manifest as a sensation of burning and redness after coming into contact with irritants or chemicals. The discharge may become less purulent and frequently improves after the removal of the irritant.

The medical background should be considered in the differential diagnosis. For viral infection, it is fundamental to search for recent contact with persons who have exhibited comparable symptoms, a past occurrence of cold sores (caused by the herpes simplex virus), or shingles (caused by the varicella-zoster virus). Past use of contact lenses can be significant, especially when considering adenoviral infections. For allergies, the clinician should request information regarding recent contact with recognized allergies, such as pollen, dust, or animal dander. Allergic blepharoconjunctivitis commonly occurs during certain seasons or is associated with specific triggers. With bacterial infections, it is fundamental to consider recent occurrences of upper respiratory infections or proximity to individuals with bacterial conjunctivitis. Chemical exposure needs to be evaluated for recent exposure to chemicals or irritants, such as chlorine in swimming pools or domestic cleaning products.

Diagnostic tests can be useful in determining etiology. Viral conjunctivitis can be diagnosed with PCR testing. This assay is highly sensitive to identifying specific viral DNA or RNA, namely for HSV, VZV, and adenovirus. PCR is a diagnostic technique that can verify the existence of the virus and differentiate between various strains. Viral cultures can be used in difficult cases. This refers to the process of growing and isolating viruses in a laboratory setting to study their characteristics and behavior. This method can be utilized to separate and detect the virus from conjunctival swabs. This is very valuable for verifying adenoviral infections. Immunoassays can identify viral antigens or antibodies. For instance, the utilization of direct fluorescent antibody testing can accurately detect adenoviral infections. Gram stain and culture can be used to diagnose bacterial infections. The Gram stain of the discharge and culture can be used to identify bacterial pathogens.

Allergy testing can be useful for causes not related to viruses. To accurately identify certain allergies, skin prick testing or serological assays may be required. Schirmer's test can be used to diagnose underlying dry eye diseases. The procedure assesses tear production and aids in the diagnosis of dry eye syndrome or meibomian gland.

Medical assessment is imperative to making a diagnosis. The conjunctival appearance must be considered. Viral conjunctivitis commonly manifests as widespread redness of the conjunctiva. Bacterial infections can exhibit localized hyperemia, which is an increased blood flow in a specific area, along with the presence of purulent discharge. The ocular surface evaluation is fundamental. Dendritic ulcers are a clear sign of HSV infection. Additional viral infections may exhibit a broader and more widespread corneal involvement, whereas allergic or bacterial conjunctivitis often does not directly impact the cornea. Preauricular lymphadenopathy manifests as the enlargement of lymph nodes located in front of the ear. Prevalent in viral conjunctivitis, especially adenoviral infections. This discovery can aid in distinguishing between allergic or bacterial origins.

Clinical examination: Prompt diagnosis of viral blepharoconjunctivitis is essential in other to control the spread of the disease. Subjective symptoms such as eyelid swelling, serofibrinous discharges, ciliary injection, subconjunctival hemorrhage, punctate epithelial keratopathy, and occasional preauricular lymph node inflammation may aid in the diagnosis[123].

Laboratory tests: Careful examination of the eyelid margins and the type of discharge emanating from the eye and the lymph nodes are useful clinical tests that can help the diagnosis of viral blepharoconjunctivitis. The immunochromatography test kit was introduced to diagnose adenoviral infections in 1996[124]. It works by detecting the presence of the presence of hexon proteins which are the outer parts of adenoviruses[125]. A unique viral detection tool that uses tears instead of conjunctival scrapings has also been found useful in the diagnosis of adenoviruses[126,127].

Viral culture: Molecular analyses are the most common method for diagnosing the presence of viruses in vivo or in vitro, as the time taken to isolate a virus might be long, demands a lot of technical know-how, is expensive, and also requires a special form of setup.

For effective management of viral blepharoconjunctivitis, culture assessment is very important, as determination of the viral agent involved is of paramount importance. With the knowledge that the viral load is a factor in the remission of symptoms and prognosis[127], effective laboratory culture becomes very important, the virus of concern must be determined with high-level accuracy, and the best-responding medication taught in the management of the condition[64]. Although the most common viral agent isolated from the ocular surface over the years, is the herpes simplex virus 1[128], that does not mean a randomized treatment plan should not be discontinued if resolution seems not to occur. Viruses can be cultured in two or more forms, of which we have the tube culture and the shell vial method.

PCR: Metagenomic deep sequencing, and cenegermin nerve growth factor[129] offer promise as diagnostic, and therapeutic options, respectively. Polymerase chain reaction offers a wide range of advantages, including but not limited to, high sensitivity and specificity, it can also be used to assess a wide range of rotavirus, which is a common cause of diarrhea in children[130,131]. Real-time PCR helps in obtaining insights into viral workups, including those affecting the respiratory tracts in children[132]. Polymerase chain reaction comes highly recommended in cases of recurrent or non-differentiating ocular inflammation. The PCR test is a rapid test for identification of different strains of the adenovirus[133-135].

Imaging studies: Confocal microscopy is a very important non-invasive method of imaging, even in cases where there is already existing keratopathy[136]. Adenovirus infections usually are capable of affecting deeper tissues spreading down to the orbit, hence MRI is a strong tool in the clinical workup of ocular infection, with high-level suspicion for adenovirus[137,138]. Immunochromatography comes in more handy and useful than the enzymatic assay, in terms of specificity and sensitivity, in identifying adenoviral-related conjunctivitis[139]. In almost all cases of viral infection electron microscopy, due to its rapid nature and relatively inexpensiveness, it is an important imaging tool in viral infections[140].

Management strategies for viral blepharoconjunctivitis

Management of viral blepharoconjunctivitis starts with an appropriate diagnosis of the actual causative agent, followed by an appropriate culture plan, if management or treatment must be holistic, and with better prognostic outcome. Although if management is prompt better outcomes are sure, but some cases can end up causing debilitating ocular defects with long-time visual disability and discomfort. A remarkable effect has been found from the use of zalcitabine, sanidine, interferon beta, and anti osteopontin, in the treatment of adenoviral-related conjunctivitis[141], there seems to be no experimental study to show the significant therapeutic effect gotten from the combination of topical corticosteroid and topical cidofovir in treating adenoviral related eye infection[142]. Some cases of ocular tumor especially ocular sebaceous carcinoma can present with signs of blepharoconjunctivitis too, so appropriate diagnosis of a condition is very key in preventing more devastating sequelae[143]. Managing blepharoconjunctivitis irrespective of the cause is poised at limiting surface inflammation, limiting dysfunction involving the meibomian gland and protecting the eyelid integrity[144].

General supportive measures

Management is usually supportive or conservative, especially in uncomplicated cases[24]. The use of a warm compass to relieve symptoms and appropriate ocular hygiene has also been documented. Also, there is an important need to as a matter of importance avoid possible triggers, especially environmental triggers[1]. For cases of blepharoconjunctivitis occurring side by side with other conditions, are managed with proper management of the triggering condition, Termozolamide has been found to have ocular side effects in treating a patient that presents with blepharoconjunctivitis and also multiform gliomas[145] eyelid hygiene enhances better treatment outcome in cases of blepharoconjunctivitis[146].

Complications and their management

Blepharoconjunctivitis can lead to a range of complications if not properly managed. One major complication is chronic discomfort and irritation[146], which can significantly impact a patient's quality of life similar to other diseases[147,148]. Persistent inflammation can in turn cause changes in the structure of the eyelids, such as thickening, scarring, or the development of irregularities in the eyelid margin[149,150]. These structural changes can disrupt the normal function of the eyelids, potentially leading to issues like trichiasis, where eyelashes grow inward and rub against the cornea, causing further irritation and risk of corneal abrasions or ulcers, and eventual blindness[146].

Another significant complication of blepharoconjunctivitis is the increased risk of secondary infections[151]. The chronic inflammation and disruption of the normal eyelid and conjunctival architecture can compromise the natural barriers that protect the eye from pathogens. This can lead to recurrent bacterial or viral infections, which may exacerbate the inflammation and further damage the ocular surface. Additionally, chronic inflammation can result in meibomian gland dysfunction, leading to dry eye syndrome. This condition not only causes discomfort but also increases the risk of further complications like corneal erosion, which can severely impair vision if not treated appropriately. Thus, the management of blepharoconjunctivitis requires a comprehensive approach to mitigate these potential complications and preserve ocular health.

Prevention and control measures

Hygiene practices: As with all infective processes, proper hygiene is the first point of call in preventive considerations. A primary step is maintaining good eyelid hygiene[152]. This involves regular cleaning of the eyelids to remove debris, oils, and bacteria that can contribute to inflammation[152]. Using a clean, damp cloth or a commercially available eyelid scrub, gently wipe along the lash line to keep the area clean[153]. It’s recommended to perform this cleaning routine at least once a day, especially if the patient has a predisposition to blepharitis or has experienced recurrent episodes of conjunctivitis[154].

Another essential step is to practice good hand hygiene, as this helps to prevent the transfer of infectious agents to the eyes[114]. Hands should be washed thoroughly with soap and water before touching the face or eyes[155]. Additionally, individuals should avoid rubbing their eyes, as this can introduce bacteria or viruses and exacerbate irritation[155]. For contact lens users, it is vital to follow proper lens care guidelines, including washing hands before handling lenses, using appropriate cleaning solutions, and replacing lenses as recommended[156,157]. Avoid sharing personal items like towels, cosmetics, and eye drops to minimize the risk of cross-contamination. Implementing these hygiene practices can significantly reduce the likelihood of developing blepharoconjunctivitis and help maintain overall eye health.

Vaccines: Vaccinations are a useful management for viral blepharoconjunctivitis as they directly attack the causal agents. Trifluridine has been suggested as a possible prophylactic choice for adenoviruses and the monkeypox virus[158]. Trifluridine combined with brincidofovir and tecovirimat performed better than single-therapy tecovirimat in resistant monkeypox strains[159]. Multiple vaccines including NIOCH-14, Cidofovir, CMX-001, and ST-246 are in the final stages of development and show some promise in blepharoconjunctivitis prevention[160]. Al-Dwairi et al[161] reported that periocular vaccination produced better protection against herpes simplex keratitis than against systemic vaccination. Naidu et al[162] however suggested that intramuscular administration of the HSV-VC1 vaccine resulted in complete protection against the McKrae strain of the HSV virus. On the other hand, systemic vaccines have also been known to re-activate dormant herpes simplex virus in ocular tissue[163].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, viral blepharoconjunctivitis presents a significant clinical challenge due to its highly contagious nature and potential for widespread transmission. This paper has shed light on the complexities surrounding this ocular condition by examining its etiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management strategies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Ophthalmology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Wu J S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zheng XM

Contributor Information

Mutali Musa, Department of Optometry, University of Benin, Benin 300283, Nigeria; Department of Ophthalmology, Africa Eye Laser Centre Ltd, Benin 300105, Nigeria; Department of Ophthalmology, Centre for Sight Africa Ltd, Nkpor 434212, Nigeria.

Babatunde Ismail Bale, Department of Optometry, University of Benin, Benin 300283, Nigeria.

Ayuba Suleman, Department of Ophthalmology, Africa Eye Laser Centre Ltd, Benin 300105, Nigeria.

Gladness Aluyi-Osa, Department of Ophthalmology, Africa Eye Laser Centre Ltd, Benin 300105, Nigeria.

Ekele Chukwuyem, Department of Ophthalmology, Centre for Sight Africa Ltd, Nkpor 434212, Nigeria.

Fabiana D’Esposito, Imperial College Ophthalmic Research Group Unit, Imperial College, London NW1 5QH, United Kingdom; GENOFTA srl, Via A. Balsamo, 93, Naples 80065, Italy.

Caterina Gagliano, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Enna "Kore", Catania 94100, Italy; Eye Clinic, Catania University San Marco Hospital, Catania 95121, Italy.

Antonio Longo, Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital of Catania, Catania 95123, Italy.

Andrea Russo, Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital of Catania, Catania 95123, Italy.

Marco Zeppieri, Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital of Udine, Udine 33100, Italy. mark.zeppieri@asufc.sanita.fvg.it.

References

- 1.Fazal MI, Patel BC. Blepharoconjunctivitis. 2023 Jul 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chodosh J, Pineda R II, Bunya VY, Sundar G, Yen MT, MD, Burkat CN, Kaufman AR. 2024. Monkeypox. Accessed June 7, 2024. Available from: https://eyewiki.org/Monkeypox .

- 3.McCulley JP. Blepharoconjunctivitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1984;24:65–77. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198424020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeppieri M, Gagliano C, Spadea L, Salati C, Chukwuyem EC, Enaholo ES, D'Esposito F, Musa M. From Eye Care to Hair Growth: Bimatoprost. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024;17 doi: 10.3390/ph17050561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitiello L, Lixi F, Coco G, Giannaccare G. Ocular Surface Side Effects of Novel Anticancer Drugs. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16 doi: 10.3390/cancers16020344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira SM, Lima RV, Muniz MCR, Araújo MBF, de Moraes Ferreira Júnior L, de Queiroz Sales Martins JT, Luz CFC, Cid DAC, da Rocha Lucena D. Congenital herpes simplex with ophthalmic and multisystem features: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23:611. doi: 10.1186/s12887-023-04423-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nghiem AZ, Ameen M, Koutroumanos N. Canalicular obstruction associated with dupilumab. Int Ophthalmol. 2023;43:4791–4795. doi: 10.1007/s10792-023-02880-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Z, Oyeniran EO, Xu X, Baumrin EL. Pseudomonal blepharoconjunctivitis causing neutropenic sepsis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2022;24:e13718. doi: 10.1111/tid.13718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bothun CE, Decanini A, Bothun ED. Tinea blepharitis and follicular conjunctivitis in a child. J AAPOS. 2021;25:253–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2021.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subramanian N. Blepharoplasty. Indian J Plast Surg. 2008;41:S88–S92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinash RG, Fulton NJ. Essential blepharospasm: nursing update. J Neurosci Nurs. 1990;22:215–219. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehrotra N, Singh S. Periodontitis. 2023 May 1. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thygeson P. The etiology and treatment of blepharitis; a study in military personnel. Mil Surg. 1946;98:191–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Floor T, Henry YP, Kraal-Biezen E. [Corneal perforation due to 'lost' contact lenses] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2019;163 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Idu FK, Efosa AD, Mutali M Jr. Ocular Side Effects of Eyelash Extension Use Among Female Students of the University of Benin, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. Cureus. 2024;16:e53047. doi: 10.7759/cureus.53047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabhahit SV, Babu M, V D. Ocular effects of eye cosmetic formulations. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2024;43:154–160. doi: 10.1080/15569527.2024.2360735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le T, Can B, Orge F. Herpes Simplex Conjunctivitis and Recurrent Chalazia in a Patient DOCK8 Deficiency. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2022;30:1988–1991. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1919309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeu E, Garg S, Ayres BD, Beckman K, Chamberlain W, Lee B, Raju L, Rao N, Rocha KM, Schallhorn J, Zavodni Z, Mah FS, Farid M from the ASCRS Cornea Clinical Committee. Current state and future perspectives in the diagnosis of eyelid margin disease: clinical review. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2024;50:868–875. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000001483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahuja AS, Farford BA, Forouhi M, Abdin R, Salinas M. The Ocular Manifestations of COVID-19 Through Conjunctivitis. Cureus. 2020;12:e12218. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salvetat ML, Musa M, Pellegrini F, Salati C, Spadea L, Zeppieri M. Considerations of COVID-19 in Ophthalmology. Microorganisms. 2023;11 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11092220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musa MJ, Okoye SG, Enaholo E, Ogwumu KE, Iyami NG. Stevens-Johnson syndrome in an 18-year-old Nigerian female: A case report. Jrnl Nig Opto Assoc. 2023;25:32–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel NV, Gupta N, Shetty R. Preferred practice patterns and review on rosacea. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;71:1382–1390. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_2983_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 23.Bloom J, Parise M, Saeed O, Holicki C, Mihok B. Monkeypox Presenting with Blepharoconjunctivitis. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2023;14:647–653. doi: 10.1159/000533914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kornhauser T, Pemberton JD. Temozolomide-associated blepharoconjunctivitis: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024;24:162. doi: 10.1186/s12886-024-03417-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira S, Torres T. Conjunctivitis in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. Drugs Context. 2020;9 doi: 10.7573/dic.2020-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberman P, Shifera AS, Berkenstock M. Dupilumab-Associated Conjunctivitis in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis. Cornea. 2020;39:784–786. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zannella C, Chianese A, De Bernardo M, Folliero V, Petrillo F, De Filippis A, Boccia G, Franci G, Rosa N, Galdiero M. Ophthalmic Solutions with a Broad Antiviral Action: Evaluation of Their Potential against Ocular Herpetic Infections. Microorganisms. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10091728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scampoli P, Di Martino G, Cedrone F, Odio C, Di Giovanni P, Romano F, Staniscia T. The Burden of Herpes Zoster on Hospital Admissions: A Retrospective Analysis in the Years of 2015-2021 from the Abruzzo Region, Italy. Vaccines (Basel) 2024;12 doi: 10.3390/vaccines12050462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinchinat S, Cebrián-Cuenca AM, Bricout H, Johnson RW. Similar herpes zoster incidence across Europe: results from a systematic literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang W, Bai L, Tang H. Epstein-Barr virus infection: the micro and macro worlds. Virol J. 2023;20:220. doi: 10.1186/s12985-023-02187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paroli MP, Restivo L, Ottaviani E, Nardella C, Abicca I, Spadea L, Paroli M. Clinical Features of Infectious Uveitis in Children Referred to a Hospital-Based Eye Clinic in Italy. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58 doi: 10.3390/medicina58111673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye Z, Chen L, Zhong H, Cao L, Fu P, Xu J. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus infection among children in Shanghai, China, 2017-2022. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1139068. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1139068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Anazi AE, Alanazi BS, Alshanbari HM, Masuadi E, Hamed ME, Dandachi I, Alkathiri A, Hanif A, Nour I, Fatani H, Alsaran H, AlKhareeb F, Al Zahrani A, Alsharm AA, Eifan S, Alosaimi B. Increased Prevalence of EBV Infection in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Patients: A Six-Year Cross-Sectional Study. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15 doi: 10.3390/cancers15030643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lévêque N, Huguet P, Norder H, Chomel JJ. [Enteroviruses responsible for acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis] Med Mal Infect. 2010;40:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scandale P, Raccagni AR, Nozza S. Unilateral Blepharoconjunctivitis due to Monkeypox Virus Infection. Ophthalmology. 2022;129:1274. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omari AA, Mian SI. Adenoviral keratitis: a review of the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018;29:365–372. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balasopoulou A, Κokkinos P, Pagoulatos D, Plotas P, Makri OE, Georgakopoulos CD, Vantarakis A. Α molecular epidemiological analysis of adenoviruses from excess conjunctivitis cases. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17:51. doi: 10.1186/s12886-017-0447-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Badawi AE, Kasem MA, Moemen D, El Sayed Zaki M. Molecular, Epidemiological and Clinical Assessment of Adenoviral Keratoconjunctivitis in Egypt: Institutional Study. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31:1640–1646. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2022.2092004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salvetat ML, Zeppieri M, Tosoni C, Parisi L, Brusini P. Non-conventional perimetric methods in the detection of early glaucomatous functional damage. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:835–842. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gonçalves MA, de Vries AA. Adenovirus: from foe to friend. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16:167–186. doi: 10.1002/rmv.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shafiei K, Makvandi M, Teimoori A, Samarbafzadeh A, Khataminia G, Jalilian S, Neisi N, Makvandi K, Haj MS. Frequency of adenovirus serotype 8 in patients with Keratoconjunctivitis, in Ahvaz, Iran. Iran J Microbiol. 2019;11:129–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta D 4th, Daigavane S. A Clinical Case of Viral Keratitis. Cureus. 2022;14:e30311. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aoki K, Kaneko H, Kitaichi N, Ohguchi T, Tagawa Y, Ohno S. Clinical features of adenoviral conjunctivitis at the early stage of infection. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55:11–15. doi: 10.1007/s10384-010-0894-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shivaprasad HL. Adenovirus group II-like infection in chukar partridges (Alectoris chukar) Avian Dis. 2008;52:353–356. doi: 10.1637/8032-062007-Case.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Della Mea G, Bacchetti S, Zeppieri M, Brusini P, Cutuli D, Gigli GL. Nerve fibre layer analysis with GDx with a variable corneal compensator in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmologica. 2007;221:186–189. doi: 10.1159/000099299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doerfler W. Adenoviruses. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th ed. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galvesto, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khehra N, Padda IS, Swift CJ. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). 2023 Mar 6. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitley RJ. Herpesviruses. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th ed. Galveston (TX), 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oh JO, Kimura SJ, Ostler HB. Acute ocular infection by type 2 herpes simplex virus in adults. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:1127–1129. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020845003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kareem Rhumaid A, Alak Mahdi Al-Buhilal J, Al-Rubaey NKF, Yassen Al-Zamily K. Prevalence and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Pathogenic Bacteria Associated with Ocular Infections in Adult Patients. Arch Razi Inst. 2022;77:1917–1924. doi: 10.22092/ARI.2022.359510.2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agulló-Ros I, Jiménez-Martín D, Camacho-Sillero L, Gortázar C, Capucci L, Cano-Terriza D, Zorrilla I, Gómez-Guillamón F, García-Bocanegra I, Risalde MA. Pathological changes and viral antigen distribution in tissues of Iberian hare (Lepus granatensis) naturally infected with the emerging recombinant myxoma virus (ha-MYXV) Vet Rec. 2023;192:e2182. doi: 10.1002/vetr.2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ávila-Reyes VA, Díaz-Morales V, Chávez-Maya F, García-Espinosa G, Sánchez-Godoy FD. Outbreak of Systemic Avian Pox in Canaries (Serinus canaria domestica) Associated with the B1 Subgroup of Avian Pox Viruses. Avian Dis. 2019;63:525–530. doi: 10.1637/12038-011819-Case.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rokohl AC, Mor JM, Trester M, Koch KR, Heindl LM. [Rehabilitation of Anophthalmic Patients with Prosthetic Eyes in Germany Today - Supply Possibilities, Daily Use, Complications and Psychological Aspects] Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2019;236:54–62. doi: 10.1055/a-0764-4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iftimovici R, Iordan L, Chelaru M. [Viral pollution studies of water environments] Virologie. 1989;40:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang TJ, Hsiao CH, Hu FR, Wang IJ, Hou YC. Acute bilateral diffuse corneal opacity in a child. Cornea. 2007;26:375–378. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31802eaf7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stumpf TH, Case R, Shimeld C, Easty DL, Hill TJ. Primary herpes simplex virus type 1 infection of the eye triggers similar immune responses in the cornea and the skin of the eyelids. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1579–1590. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, Albert MH, Ehrt O, Sawalle-Belohradsky J, Neumann J, Ries M, Bufler P, Wollenberg A, Renner ED. Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matos RJC, Pires JMS, Cortesão D. Management of Neonatal Herpes Simplex Infection: A Rare Case of Blepharoconjunctivitis and Concurrent Epithelial and Stromal Keratitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26:625–627. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2016.1242017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carter SB, Cohen EJ. Development of Herpes Simplex Virus Infectious Epithelial Keratitis During Oral Acyclovir Therapy and Response to Topical Antivirals. Cornea. 2016;35:692–695. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu S, Pavan-Langston D, Colby KA. Pediatric herpes simplex of the anterior segment: characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2003–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campanella PC, Rosenwasser GO, Sassani JW, Goldberg SH. Herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis presenting as complete acquired ankyloblepharon. Cornea. 1997;16:360–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilhelmus KR, Dawson CR, Barron BA, Bacchetti P, Gee L, Jones DB, Kaufman HE, Sugar J, Hyndiuk RA, Laibson PR, Stulting RD, Asbell PA. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis recurring during treatment of stromal keratitis or iridocyclitis. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:969–972. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.11.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Malik AN, Hildebrand GD, Sekhri R, Russell-Eggitt IM. Bilateral macular scars following intrauterine herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. J AAPOS. 2008;12:305–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Souza PM, Holland EJ, Huang AJ. Bilateral herpetic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:493–496. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01772-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imamoglu EY, Gunay M, Cilek EA, Karatekin G. Bilateral blepharoconjunctivitis as the presenting sign of disseminated herpes simplex 1 infection in a preterm neonate. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2014;22:326–329. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2013.807346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hong J, Deng SX, Sun X, Xu J. Oral acyclovir for herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in children. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:e28. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu G, Wang MJ, Miller MJ, Holland GN, Bruckner DA, Civen R, Bornstein LA, Mascola L, Lovett MA, Mondino BJ, Pegues DA. Ocular vaccinia following exposure to a smallpox vaccinee. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:554–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adishvili L, Bodokia N, Tsikarishvili S, Tskitishvili A. Adult Varicella Complicated by Deep Venous Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Report and a Literature Review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59213. doi: 10.7759/cureus.59213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saksena R, Thomas BJ, Das R, Nagpal S, Suri PR, Wadhwa RK, Choudhary A, Gaind R, Gupta E. Varicella zoster virus outbreak in a long-term care unit of a tertiary care hospital in northern India. Epidemiol Infect. 2024;152:e81. doi: 10.1017/S0950268824000712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Biswas J, Nagpal A, Chopra S, Karna S. Resolution of chicken pox neuroretinitis with oral acyclovir: a case report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2003;11:315–318. doi: 10.1076/ocii.11.4.315.18267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takahashi S, Okabayashi K, Soejima I, Oniki A, Ishihara S, Tomimitsu H. Delayed Superior Orbital Fissure Syndrome Arising More than One Month after Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus and Meningitis. Intern Med. 2024 doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.3652-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Musa M, Enaholo E, Aluyi-Osa G, Atuanya GN, Spadea L, Salati C, Zeppieri M. Herpes simplex keratitis: A brief clinical overview. World J Virol. 2024;13:89934. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v13.i1.89934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chau VQ, Hinkle JW, Wu CY, Pakravan P, Volante V, Sengillo JD, Staropoli PC, Miller D, Yannuzzi NA, Albini TA. Outcomes of infectious panuveitis associated with simultaneous multi-positive ocular fluid polymerase chain reaction. Retina. 2024;44:909–915. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000004037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soldan SS, Messick TE, Lieberman PM. Therapeutic approaches to Epstein-Barr virus cancers. Curr Opin Virol. 2022;56:101260. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2022.101260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dunmire SK, Hogquist KA, Balfour HH. Infectious Mononucleosis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;390:211–240. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22822-8_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murata T. Epstein-Barr virus: the molecular virology and the associated diseases. Fujita Med J. 2023;9:65–72. doi: 10.20407/fmj.2022-018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang N, Zuo Y, Jiang L, Peng Y, Huang X, Zuo L. Epstein-Barr Virus and Neurological Diseases. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:816098. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.816098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O'Gallagher M, Bunce C, Hingorani M, Larkin F, Tuft S, Dahlmann-Noor A. Topical treatments for blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD011965. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011965.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lieberman PM. Chromatin Structure of Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Episomes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;390:71–102. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22822-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hatton OL, Harris-Arnold A, Schaffert S, Krams SM, Martinez OM. The interplay between Epstein-Barr virus and B lymphocytes: implications for infection, immunity, and disease. Immunol Res. 2014;58:268–276. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8496-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smatti MK, Al-Sadeq DW, Ali NH, Pintus G, Abou-Saleh H, Nasrallah GK. Epstein-Barr Virus Epidemiology, Serology, and Genetic Variability of LMP-1 Oncogene Among Healthy Population: An Update. Front Oncol. 2018;8:211. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cancian L, Bosshard R, Lucchesi W, Karstegl CE, Farrell PJ. C-terminal region of EBNA-2 determines the superior transforming ability of type 1 Epstein-Barr virus by enhanced gene regulation of LMP-1 and CXCR7. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002164. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Solomay TV, Semenenko TA. [Epstein-Barr viral infection is a global epidemiological problem] Vopr Virusol. 2022;67:265–273. doi: 10.36233/0507-4088-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.França SAS, Viana JBGO, Góes HCA, Fonseca RRS, Laurentino RV, Costa IB, Oliveira-Filho AB, Machado LFA. Epidemiology of the Epstein-Barr Virus in Autoimmune Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases in Northern Brazil. Viruses. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/v14040694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hsia NY, Bair H, Lin CY, Lin CJ, Lai CT, Chang CM, Lin JM, Tsai YY. Epstein-Barr Virus Uveitis Confirmed via Aqueous Humor Polymerase Chain Reaction and Metagenomics-A Case Report. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024;60 doi: 10.3390/medicina60010097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alba-Linero C, Rocha-de-Lossada C, Rachwani-Anil R, Sainz-de-la-Maza M, Sena-Corrales G, Romano V, Rodríguez-Calvo-de-Mora M. Anterior segment involvement in Epstein-Barr virus: a review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022;100:e1052–e1060. doi: 10.1111/aos.15061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee JH, Agarwal A, Mahendradas P, Lee CS, Gupta V, Pavesio CE, Agrawal R. Viral posterior uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2017;62:404–445. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tang RT, Gavito-Higuera J, Prospero Ponce CM. A Case of Epstein-Barr Virus Encephalitis and Orbital-Face Inflammation. Cureus. 2024;16:e56888. doi: 10.7759/cureus.56888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mushiga Y, Komoto T, Nagai N, Ozawa Y. Effects of intraocular treatments for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) retinitis: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e28101. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Victor AA, Sukmana N. RETINAL VASCULITIS ASSOCIATED WITH EPSTEIN-BARR VIRUS INFECTION, A CASE REPORT. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2018;12:314–317. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hsia YC, Chin-Hong PV, Levin MH. Epstein-Barr Virus Neuroretinitis in a Lung Transplant Patient. J Neuroophthalmol. 2017;37:43–47. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Peponis VG, Chatziralli IP, Parikakis EA, Chaira N, Katzakis MC, Mitropoulos PG. Bilateral Multifocal Chorioretinitis and Optic Neuritis due to Epstein-Barr Virus: A Case Report. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2012;3:327–332. doi: 10.1159/000343704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Keorochana N. A case report of Epstein-Barr virus-associated retinal vasculitis: successful treatment using only acyclovir therapy. Int Med Case Rep J. 2016;9:213–218. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S107089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Weller JM, Bergua A, Mardin CY. Retinopathy in a patient with acute Epstein-Barr virus infection: follow-up analysis using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2015;9:72–77. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Savastano MC, Rispoli M, Di Antonio L, Mastropasqua L, Lumbroso B. Observed positive correlation between Epstein-Barr virus infection and focal choroidal excavation. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34:927–932. doi: 10.1007/s10792-013-9874-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu Z, Ji MF, Huang QH, Fang F, Liu Q, Jia WH, Guo X, Xie SH, Chen F, Liu Y, Mo HY, Liu WL, Yu YL, Cheng WM, Yang YY, Wu BH, Wei KR, Ling W, Lin X, Lin EH, Ye W, Hong MH, Zeng YX, Cao SM. Two Epstein-Barr virus-related serologic antibody tests in nasopharyngeal carcinoma screening: results from the initial phase of a cluster randomized controlled trial in Southern China. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:242–250. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.De Paschale M, Clerici P. Serological diagnosis of Epstein-Barr virus infection: Problems and solutions. World J Virol. 2012;1:31–43. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v1.i1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.She RC, Stevenson J, Phansalkar AR, Hillyard DR, Litwin CM, Petti CA. Limitations of polymerase chain reaction testing for diagnosing acute Epstein-Barr virus infections. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;58:333–335. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sato T, Kitamura R, Kaburaki T, Takeuchi M. Retinitis associated with double infection of Epstein-Barr virus and varicella-zoster virus: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11663. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Walling DM, Flaitz CM, Nichols CM. Epstein-Barr virus replication in oral hairy leukoplakia: response, persistence, and resistance to treatment with valacyclovir. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:883–890. doi: 10.1086/378072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Durand ML, Barshak MB, Sobrin L. Eye Infections. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:2363–2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2216081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sinclair W, Omar M. Enterovirus. 2023 Jul 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Langford MP, Anders EA, Burch MA. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis: anti-coxsackievirus A24 variant secretory immunoglobulin A in acute and convalescent tear. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1665–1673. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S85358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wright PW, Strauss GH, Langford MP. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. Am Fam Physician. 1992;45:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Meza-Romero R, Navarrete-Dechent C, Downey C. Molluscum contagiosum: an update and review of new perspectives in etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:373–381. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Peterson AR, Nash E, Anderson BJ. Infectious Disease in Contact Sports. Sports Health. 2019;11:47–58. doi: 10.1177/1941738118789954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leung AKC, Barankin B, Hon KLE. Molluscum Contagiosum: An Update. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2017;11:22–31. doi: 10.2174/1872213X11666170518114456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Senkevich TG, Koonin EV, Bugert JJ, Darai G, Moss B. The genome of molluscum contagiosum virus: analysis and comparison with other poxviruses. Virology. 1997;233:19–42. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Singh M, Acharya M, Gandhi A, Prakash U. Molluscum-related keratoconjunctivitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:1176. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1808_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ringeisen AL, Raven ML, Barney NP. Bulbar Conjunctival Molluscum Contagiosum. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:294. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Moss WJ. Measles. Lancet. 2017;390:2490–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Naim HY. Measles virus. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:21–26. doi: 10.4161/hv.34298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.White SJ, Boldt KL, Holditch SJ, Poland GA, Jacobson RM. Measles, mumps, and rubella. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:550–559. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31824df256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hviid A, Rubin S, Mühlemann K. Mumps. Lancet. 2008;371:932–944. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Muto T, Imaizumi S, Kamoi K. Viral Conjunctivitis. Viruses. 2023;15 doi: 10.3390/v15030676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Solano D, Fu L, Czyz CN. Viral Conjunctivitis. 2023 Aug 28. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]