Abstract

Nuclear extracts from Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells synchronized in S phase support the semiconservative replication of supercoiled plasmids in vitro. We examined the dependence of this reaction on the prereplicative complex that assembles at yeast origins and on S-phase kinases that trigger initiation in vivo. We found that replication in nuclear extracts initiates independently of the origin recognition complex (ORC), Cdc6p, and an autonomously replicating sequence (ARS) consensus. Nonetheless, quantitative density gradient analysis showed that S- and M-phase nuclear extracts consistently promote semiconservative DNA replication more efficiently than G1-phase extracts. The observed semiconservative replication is compromised in S-phase nuclear extracts deficient for the Cdk1 kinase (Cdc28p) but not in extracts deficient for the Cdc7p kinase. In a cdc4-1 G1-phase extract, which accumulates high levels of the specific Clb-Cdk1 inhibitor p40SIC1, very low levels of semiconservative DNA replication were detected. Recombinant Clb5-Cdc28 restores replication in a cdc28-4 S-phase extract yet fails to do so in the cdc4-1 G1-phase extract. In contrast, the addition of recombinant Xenopus CycB-Cdc2, which is not sensitive to inhibition by p40SIC1, restores efficient replication to both extracts. Our results suggest that in addition to its well-characterized role in regulating the origin-specific prereplication complex, the Clb-Cdk1 complex modulates the efficiency of the replication machinery itself.

Replication of the eukaryotic genome occurs exclusively during S phase and requires strict coordination among cis-acting sequences, the replicative enzymes, and their regulatory factors to ensure that origins of replication fire only once per cell cycle. The presence of multiple origins of replication on eukaryotic chromosomes permits the simultaneous engagement of polymerases at different sites on the same chromosome and also allows for delayed or regulated origin firing (25). Both the cis-acting sequences and the trans-acting factors that function at origins in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been well characterized genetically, although no successful reconstitution of origin-dependent replication in a fully soluble system has been reported (6, 54).

All known yeast origins of replication include an essential 11-bp sequence, called the autonomously replicating sequence (ARS) consensus, situated within an AT-rich stretch of DNA that binds the nuclear scaffold (reviewed in reference 50). These elements confer high-frequency transformation on circular plasmids in S. cerevisiae (32, 63) and function as origins of DNA replication on both circular and linear plasmids and in the genome (7, 33). ARS elements occur on average once per 36 kb in yeast chromosomes (49), although not all are active origins in their native genomic context (50). Under certain conditions, a large fragment of yeast chromosome III appears capable of semiconservative replication in the absence of detectable initiation events at known ARS elements (48a). This fact suggests that alternative means to initiate replication may exist in vivo, although the mechanisms remain to be characterized.

The standard ARS-specific initiation of replication in yeast requires ORC, a six-subunit origin recognition complex (4, 16). Strains with temperature-sensitive alleles of ORC2 and ORC5 arrest in S phase with the dumbbell phenotype typical of mutants that affect DNA replication and show a drop in the efficiency of initiation (3, 40, 42). Moreover, G1-phase nuclei isolated from a temperature-sensitive orc2-1 mutant fail to initiate DNA replication in vitro at the restrictive temperature (53). Although ORC is bound to the ARS consensus throughout the cell cycle (17), in vivo footprinting data indicate that additional components associate with ORC following entry into G1 phase, forming the so-called prereplicative complex (pre-RC) (17). The transition from the postreplicative complex to the pre-RC coincides with the synthesis of Cdc6p (9, 55), a protein that is essential for the initiation of DNA replication and that associates with ORC (39, 40). Cdc6p, in turn, promotes the association of minichromosome maintenance (MCM) proteins with prereplicative chromatin (10, 21, 64). Activation through an S-phase-promoting factor is proposed to modify and possibly displace Cdc6p and the MCM proteins from the pre-RC, triggering the initiation of DNA replication (15, 47).

The initiation of DNA synthesis itself requires the catalytic activity of the polymerase α (pol α)-primase complex, which is composed of four subunits, two of which (p48 and p58) are involved in short RNA primer synthesis on the template strand (reviewed in reference 27). The catalytic p180 subunit then extends the cDNA strand for 100 to 200 nucleotides. The exact function of the second largest subunit, p86, is unknown, but this subunit appears to be regulatory and may target the complex to prereplicative foci. In the well-characterized simian virus 40 (SV40) replication reaction, the pol α-primase complex is targeted to the site of initiation through contacts with the single-strand-binding protein replication protein A (RPA) and the virus-encoded, origin-binding factor, large T antigen (11, 22, 41). RPA is also essential for early steps in genomic replication in eukaryotes, but it associates tightly with DNA near the origin only after activation of the Clb-Cdk1 kinase (65). The fact that replication-associated RPA foci form independently of ORC in nuclei reconstituted in Xenopus extracts (10) suggests that replication enzymes and factors may associate by a mechanism partially independent of the ORC-containing pre-RC. Consistently, a proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-binding sequence motif that targets enzymes to replication foci in mammalian cells has been identified (8, 45).

In yeast, the protein kinase encoded by CDC28 (also called Cdk1) is a key regulator of the cell division cycle and, when complexed with B-type cyclins, this kinase is essential for promotion of S phase (reviewed in reference 48). The six B-type cyclins that stimulate Cdk1 are expressed at different points in the cell cycle. CLB5 and CLB6 expression peaks in early S phase, and although deletion of these genes delays the onset of S phase, other B-type cyclins can promote S phase if induced after the pre-RC has formed (2, 60). Not only does activation of the Clb-Cdc28 complex promote the G1/S transition, but also the sustained activity of this complex through G2 phase appears necessary to prevent the precocious reassembly of the pre-RC. Thus, the maintenance of high Clb-Cdk1 activity also ensures that origins fire only once per cell cycle (12). Cdc6p appears to be a physiological substrate of Clb-Cdc28, but other replication-associated targets undoubtedly exist, since mutation of the phosphoacceptor sites in Cdc6p has little effect on cell cycle progression (7a). Moreover, Clb-Cdc28 activity is a prerequisite for the association of Cdc45p with the pre-RC (69).

A second Ser/Thr kinase, encoded by CDC7, is also necessary for the initiation of DNA replication in vivo (5, 19, 31, 34) and in isolated yeast nuclei (54a). The genetically determined CDC7 execution point is downstream of the point of G1/S function of CDC28 (31), and its activity is necessary throughout S phase to allow the activation of late-firing origins (5, 20). Mcm2p is at least one of the physiological substrates of the Dbf4-Cdc7 complex (38). Intriguingly, the requirement for both Cdc7p and its regulatory subunit, Dbf4p, can be bypassed by an allele of MCM5 called bob1-1 (30).

In vertebrate cells, promotion of S phase requires Cdk2 in complex with cyclins D1, E, and A (29, 51, 52, 57). Consistently, the promotion of replication in isolated G1-phase HeLa cell nuclei requires the synergistic activity of CycA-Cdk2 and CycE-Cdk2 (37). The mitotic CycB-Cdc2 kinase does not stimulate replication in this mammalian in vitro replication system, yet in a similar reconstituted yeast system in which G1-phase nuclear templates replicate semiconservatively (53), either the recombinant Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 kinase or the yeast Clb5-Cdc28 complex can serve to promote ORC-dependent initiation in vitro (54a). To further examine the ORC and kinase dependence of DNA replication in yeast, we have made use of a recently established soluble DNA replication assay in which supercoiled plasmids can be semiconservatively replicated in S-phase nuclear extracts. This reaction requires polymerase δ (pol δ), the pol α-primase complex, and the Dna2 helicase (6). Both ribonucleotides and deoxynucleotides are required for successful replication, which is sensitive to aphidicolin but not α-amanitin. Despite a demonstrated dependence on replicative polymerases, we show here that the replication of naked plasmid DNA in vitro does not require a functional ARS, the ORC, or the CDC6 gene product. As a result, our replication assay permits us to examine the effects of the Cdk1 and Cdc7 kinases on enzymatic events that take place downstream of the establishment and activation of the ORC-dependent initiation complex. By several approaches, we show that semiconservative DNA replication in vitro requires the activity of the Clb-Cdk1 kinase but not of the Dbf4-Cdc7 kinase. This finding suggests that B-type cyclin-dependent kinases play at least two roles in replication: in addition to regulating pre-RC assembly and disassembly, Clb-Cdk1 may regulate the replication machinery itself.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, synchronization, isolation, and extraction of yeast nuclei.

The genotypes of all strains used are listed in Table 1. GA-59, or congenic GA-811, was used as our standard wild-type strain, except as indicated otherwise. We have prepared extracts from a large variety of yeast strains and have detected no reproducible background-based variation in replication efficiency as long as the strains are wild type for cell cycle and replication factors. Several of the strains used here are nonetheless from the same background, notably, GA-112 and GA-1087, which are derived from the parent of GA-462. GA-161 and GA-315 are from the background of the original cdc collection of Hartwell et al. (31). All temperature-sensitive strains were checked for lethality at the restrictive temperature before and after culturing. The pep4 yeast strains were regularly tested by a plate-stain assay for carboxypeptidase Y activity (35).

TABLE 1.

Strains

| Name (previous name) | Source | Genotype |

|---|---|---|

| GA-59 (BJ2168) | E. Jones | MATa leu2 trp1 ura3-52 gal2 pep4-3 prb1-1122 prc1-407 |

| GA-85 (RM14-3A) | B. Brewer | MATa bar1 his6 leu2-3 leu2-112 trp1-289 ura3-52 cdc7-1 |

| GA-112 (K1719) | K. Nasmyth | MATa ade2-11 can1-100 his3-11 his3-15 leu2-3 leu2-112 trp1-1 ura3 GAL psi+ pep4::URA3 cdc28-4 |

| GA-161 (H1GC1 A1) | L. Hartwell | MATa his7 ura1 cdc16-1 |

| GA-315 | L. Hartwell | MATa ade1 ade2 his7 lys2 tyr1 ura1 gal1 pep4::LYS2 cdc6-1 |

| GA-360 | D. Braguglia | MATa ade2-1 leu2 trp1 ura3-52 pep4::URA3 |

| GA-462 | H. Renauld | MATa ade2-1 can1-100 his3 leu2-3 leu2-112 trp1-1 ura3-1 pep4::URA3 orc2-1 |

| GA-811 | E. Jones | MATa trp1 ura3-52 pep4-3 prb1-1122 prc1-407 |

| GA-1087 | E. Schwob | MATα ade2-11 can1-100 his3-11 his3-15 leu2-3 leu2-112 trp1-1 ura3 GAL psi+ cdc4-1 |

Preparation of nuclear extracts was carried out as described previously (6). Temperature-sensitive strains were grown and synchronized by pheromone arrest and release at 25°C (or 23°C as indicated). To prepare G1- or M-phase extracts, exponential cultures at the permissive temperature for cdc4-1 (GA-1087) or cdc16-1 (GA-161) mutants were shifted to the restrictive temperature 4 h prior to harvesting. A similar protocol was used for the cdc7-1 (GA-85) extract. S-phase extracts were prepared from wild-type (GA-59, GA-811, and GA-360), cdc28-4 (GA-112), or orc2-1 (GA-462) strains after cells were blocked with α factor and released into fresh yeast-peptone-dextrose medium (YPD) at the permissive temperature until 50% had small buds. Spheroplast formation was done as rapidly as possible in YPD with 1 M sorbitol. Media were described previously (58).

In vitro replication reactions.

Replication was carried out with 300 ng of either pGEM3Z(−) (hereafter called pGEM), pH4ARS (384-bp H4ARS Sau3AI fragment cloned into the SmaI site of the polylinker), or pRS424 (61) prepared according to a standard alkaline lysis method and purified over Qiagen columns or by banding on a CsCl gradient, avoiding exposure to UV light (59). At least 90% of each preparation was in the supercoiled form. Replication reactions were performed as described previously (6). For experiments performed at restrictive temperatures, the reaction mixture was incubated for 15 or 20 min at the elevated temperature prior to the addition of the template DNA. For control reactions, preincubation was done at 23 or 25°C. When needed, 500 μg of aphidicolin per ml, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, was added, whereas control reactions received dimethyl sulfoxide alone. The replication reaction was stopped after 90 min (180 min for all 5-bromo-dUTP (BrdUTP) substitution experiments) at 25°C (or as indicated) with final concentrations of 0.3 M Na acetate (pH 5.2), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 5 mM EDTA, and 100 μg of proteinase K per ml. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min and the addition of a tRNA carrier, the DNA was extracted with phenol, precipitated, washed with 1 ml of 70% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in 20 μl of distilled water. For buoyant density analysis, the DNA was passed over a Sephadex G-50 spin column to eliminate free nucleotides. In all assays, the recovery of input DNA was quantified after the spin column step and before the CsCl gradient step by fluorescence readings and by separation of 25% of the reaction sample on an agarose gel (see Fig. 8C). Recovery of DNA in a given set of experiments usually varied less than 10%, but a correction factor for DNA recovery was introduced when semiconservative DNA synthesis was calculated in picograms of DNA synthesized or as fractions of the input template. Other modifications (substitution of BrdUTP for dTTP and buoyant density gradient analysis) are described elsewhere (6).

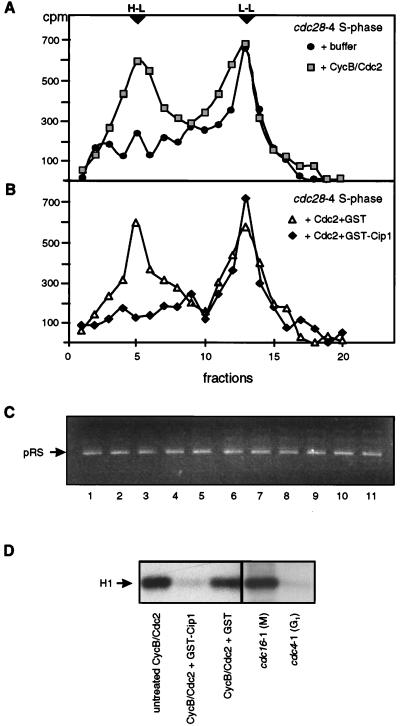

FIG. 8.

Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 activates plasmid replication in a cdc28-4 S-phase nuclear extract. (A) Buoyant density analysis was done for BrdUTP-containing replication reactions performed in parallel with those shown in Fig. 7C. Reactions were carried out with cdc28-4 (GA-112) S-phase nuclear extracts and 300 ng of pRS424 for 3 h at 23°C. Reaction mixtures contained either 10 U or recombinant Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 kinase (grey squares) or an equivalent amount of kinase buffer (black circles). DNA recovery was checked prior to CsCl gradient analysis and is shown in lanes 1 and 3 of panel C. The expected migration of H-L and L-L molecules is indicated by arrowheads. (B) BrdUTP-containing replication reactions were identical to those in panel A, except that the Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 kinase was pretreated with either GST-Cip1 beads (black diamonds) (see Materials and Methods) or GST beads (white triangles). Similar results were obtained when the kinase was inactivated by reductive alkylation and added directly to the reaction mixtures (see Materials and Methods). (C) Systematic analysis performed after each replication reaction; 25% of the recovered DNA was analyzed and quantified on an 0.8% agarose gel prior to loading of the remaining 75% on CsCl gradients. The ethidium bromide-stained plasmid was detected by UV fluorescence and quantified by scanning. The samples shown on the gel include, among others, the products from reactions analyzed in Fig. 7 and panels A and B. (D) Kinase activity as monitored by the phosphorylation of histone H1 by untreated recombinant Xenopus CycB-Cdc 2 kinase or kinase treated with either GST-Cip1 bound to glutathione-agarose beads or GST bound to glutathione-agarose beads. The relative kinase activity in equal portions of cdc16-1 (GA-161) M-phase and cdc4-1 (GA-1087) G1-phase extracts is also shown as a reference.

Analysis of semiconservative DNA replication.

Two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis (7), CsCl density gradient analysis, and the quantitation of these results with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager or direct Cerenkov counting of incorporated radioactivity are described elsewhere (6). We have validated these methods by quantifying the recovery of DNA in the heavy-light (H-L) peak of the CsCl gradient by Southern blot analysis of slot blot gradient fractions or gradient fractions after agarose gel electrophoresis. Southern blot analysis is less quantitative than direct counting of incorporated 32P-labeled deoxynucleoside triphosphates, because although a large fraction of the labeled DNA is in the H-L peak, a very small fraction of the total DNA shifts to this point in the gradient. Quantification by autoradiography and/or PhosphorImager techniques of the DNA recovered in the H-L peak from a range of experiments confirmed that between 0.1 and 2% of the input DNA was semiconservatively replicated (data not shown). The amount of label incorporated into the light-light (L-L) peak varies with the integrity of the supercoiled template and the endonuclease/ligase ratio in the extract and shows no positive correlation with the efficiency of semiconservative DNA replication. Indeed, the addition of nicked or linear template produces very high levels of incorporation into the L-L DNA peak and competes efficiently for semiconservative DNA replication (discussed in reference 6).

DpnI digestions (in 50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 150 mM NaCl) were performed on the DNA recovered from 25% of a standard replication reaction sample generally with the addition of 300 ng of fully methylated pH4ARS (fourfold excess) to monitor the ability of DpnI to completely digest its substrate.

Immunodetection.

Western blotting was performed with peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham). Rabbit antisera were used for the detection of Orc2p (gift of J. Diffley, ICRF, London, United Kingdom), p40SIC1 (gift of R. Deshaies, Pasadena, Calif.), and topoisomerase II. Monoclonal antibodies were used to detect pol α and p86 (gifts of P. Plevani and M. Foiani, University of Milan, Milan, Italy), the Myc epitope (9E10), and tubulin TAT1 (gift of K. Gull, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom).

Kinase inhibition and activity assays.

Kinase activity was assessed through measurement of histone H1 phosphorylation by established protocols (46). For the analysis of H1 kinase in nuclear extracts, the extracts were diluted to 100 ng/μl in 25 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (pH 7.5)–15 mM MgCl2–15 mM EGTA–1 mM DTT–60 mM β-glycerophosphate–0.1 mM Na orthovanadate–15 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate–1% Triton X-100 (kinase buffer). Then, histone H1 at 500 ng/μl and [γ-32P]ATP at 0.1 μCi/μl were added to a total reaction volume of 20 μl. For purified-kinase assays, extracts were omitted. After 20 min at 23°C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of SDS sample buffer. Samples were run on a 10% acrylamide–SDS gel, which was then stained with Coomassie blue to quantify equal recovery of histone H1. Incorporated radioactivity was quantified with a PhosphorImager, and values were normalized to histone H1 recovery. It should be noted that the higher eukaryotic histone H1 is a relatively poor, nonphysiological substrate for the yeast Clb-Cdc28 kinase. In S-phase yeast extracts of a cdc28-4 strain isolated at the permissive temperature, there is little modification of histone H1 at 23°C, although these extracts are fully competent for modifying endogenous targets and stimulating replication in nuclei at permissive, but not restrictive, temperatures (54a). Thus, H1 kinase assays of yeast extracts give a relative but not an absolute measure of Cdc28 kinase activity.

Expression and purification of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-p40SIC1-Myc-His6 and CycB-Cdc2 kinase.

Escherichia coli BL21 transformed with pLysS and the expression vector pGEX-4T-Sic1-Myc-His6 (where His6 is six histidines; containing the full-length SIC1 gene; gift of R. Feldman, Pasadena, Calif.) was grown at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 in Luria broth with ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml). The Sic1p fusion was induced with 0.8 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 90 min. Harvested cells were resuspended in 25 ml of 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.6)–0.5 M NaCl–5 mM β-mercaptoethanol–protease inhibitors (lysis buffer), and cells were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. The cells were thawed, lysed by sonication, and centrifuged for 20 min at 18,000 rpm in an SS34 rotor at 4°C. All subsequent steps were done at 4°C. Ni-NTA–agarose (2 ml; Qiagen) was added to the supernatant and mixed for 30 min. The lysate-resin mixture was poured into a column and washed with 5 volumes of lysis buffer plus 10% glycerol and 20 mM imidazole and then with 2 volumes of 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.6)–0.2 M NaCl. Two elutions were carried out with 5 ml of the latter buffer plus 0.5 M imidazole. The eluates were pooled and adjusted to 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT. All subsequent buffers contained these two reagents. Glutathione-agarose beads (1 ml; Sigma) were added and mixed with the eluate for 30 min. The beads were washed four times with 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.6)–0.5 M NaCl and twice with 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.6)–0.15 M NaCl, and elution was carried out with 3 ml of 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.6)–0.15 M NaCl–10 mM reduced glutathione. Dialysis was carried out for 12 h against 25 mM Tris-Cl, (pH 7.6)–0.15 M NaCl–10% glycerol (dialysis buffer). Aliquots were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Semiconservative DNA replication efficiency dropped significantly when GST-p40SIC1-Myc-His6 was titrated into a reaction mixture containing wild-type S-phase nuclear extract relative to mixtures treated with dialysis buffer alone (data not shown). However, a similar inhibition resulted from the addition of high levels of the GST moiety. The latter result may reflect an interaction between GST and PCNA which was documented in our laboratory (33a).

Partially purified Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 expressed in Sf9 cells (62) was a gift of U. K. Laemmli, P. Grandi, and P. Descombes (University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland). Activity is expressed in arbitrary units, based on a standard curve of histone H1 phosphorylation. One unit of purified recombinant CycB-Cdc2 is equivalent to the activity in 1.5 μl (20 μg) of GA-161 mitotic nuclear extract, which was used to calibrate activities in different preparations. Inactivation was carried out by treatment with GST–Cip1–glutathione-agarose beads essentially as described by Adachi and Laemmli (1). Control incubations with GST–glutathione-agarose beads were carried out in parallel. Following treatment, beads were pelleted, and the supernatants were tested for H1 kinase activity and added to the standard replication reaction for BrdUTP substitution and buoyant density analysis. Inactivation through reductive alkylation was carried out by 5 min of incubation at 0°C of 10 U of recombinant CycB-Cdc2 with 1 mM DTT, followed by the addition of 5 mM N-ethylmaleinimide (NEM). The sample was incubated for a further 30 min at 0°C, and the reaction was quenched by the addition of 25 mM DTT. This mixture or a control containing just kinase buffer, DTT, and NEM was diluted 1/50 in the replication reaction.

For the expression of recombinant Clb5-Cdc28 kinase, pMW2 contains the 1.34-kb DraI-SpeI CLB5 genomic fragment inserted into the SmaI-XbaI sites of pAcPK31 (40), and pMW6 contains the 1.23-kb BstBI-MunI CDC28 genomic fragment inserted into the SmaI-EcoRI sites of pAcPK31. These plasmids were cotransfected with BaculoGold DNA (Pharmingen) into Sf9 cells in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, and appropriate viruses were plaque purified and amplified. During purification, Cdc28p was monitored by Western blotting with the rabbit antibody Cdc28-181 (kindly provided by B. Futcher), and Clb5-Cdc28 kinase activity was monitored with an H1 kinase assay. All buffers contained 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mg of pepstatin per ml, 0.1 mg of bacitracin per ml, 1 mM benzamidine, and 1 mM DTT.

Sf9 cells (6.7 × 108 cells) grown in suspension at 27°C were infected with BVCDC28 and BVCLB5, each at multiplicity of infection of 10. After 65 h, cells were collected, washed once in phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed in hypotonic buffer (H buffer) (20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2) by Dounce homogenization on ice. The subsequent steps were carried out at 4°C. Nuclei were centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g, placed in 5 ml of H/0.1 buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 10% glycerol, 0.02% Nonidet P-40), and lysed with 12.5% (final) ammonium sulfate. The extract was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h in a Ti60 rotor, and the soluble protein was precipitated with 70% (final) ammonium sulfate. Following dialysis against H/0.1 buffer, the protein was applied to a 10-ml SP-Sepharose column (Pharmacia) and eluted with an 80-ml gradient (0.1 to 1.0 M NaCl) in H buffer. Peak fractions (0.25 M NaCl) were pooled, dialyzed against H/0.1 buffer, and applied to a 10-liter Q-Sepharose column (Pharmacia). Proteins were eluted with an 80-ml gradient (0.1 to 0.6 M NaCl) in H buffer. Peak fractions (0.2 M) were dialyzed against H/0.1 buffer, applied to a 2-ml histone-agarose column (Sigma H3889), washed with H/0.2 buffer (H buffer with 200 mM NaCl), and eluted with H buffer with 500 mM NaCl (H/0.5 buffer). The kinase was concentrated on a 0.5-ml SP-Sepharose column, applied to a 10-ml glycerol gradient (10 to 35%) in H/0.2 buffer, and centrifuged for 22.5 h at 40,000 rpm in an SW41 rotor. Fractions were collected from the top and analyzed by silver staining and an H1 kinase assay. The purified Clb5-Cdc28p fractions were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. One unit of purified recombinant kinase is equivalent to the H1 kinase activity in 1.5 μl (20 μg) of GA-161 mitotic nuclear extract (see above).

RESULTS

Nuclear extracts from yeast cells synchronized in S phase promote aphidicolin-sensitive, semiconservative replication of primer-free, supercoiled plasmids in vitro, as monitored by one-dimensional and 2D gel electrophoresis and by buoyant density analysis of the newly synthesized DNA following incorporation of the derivatized nucleotide BrdUTP (6). The reaction is dependent on DNA pol δ and the pol α-primase complex, and we have been able to detect putative Okazaki fragments under ATP-limiting conditions (6). In contrast to supercoiled templates, nicked or linear plasmid DNA incorporates BrdUTP through a repair mechanism that does not cause a shift in density to that of fully substituted H-L DNA, as monitored on CsCl gradients. The replication reaction is independent of the recombination-promoting factor Rad52p but requires the activity of the Dna2p helicase (6). Here we examine the dependence of our replication system on the ARS consensus, the pre-RC, and kinases that are known to promote S phase in vivo.

The replication of plasmid DNA in yeast nuclear extracts is ARS independent.

Highly supercoiled preparations of bacterially produced plasmids (pGEM and pH4ARS; i.e. the same vector carrying the 384-bp H4ARS fragment) were incubated in either the presence or the absence of aphidicolin in an S-phase nuclear extract isolated from a protease-deficient yeast strain (GA-59; see Materials and Methods). After 90 min of incubation in the presence of [α-32P]dATP and other, unlabeled nucleotides, DNA was purified and separated on a nondenaturing agarose gel. As shown in Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 3, the replication products of both pGEM and pH4ARS migrated as diffuse smears toward the origin of the gel. Except for a low level of repair incorporation, mainly into open circular DNA, the reaction was inhibited by aphidicolin and was fully dependent on the added template (Fig. 1A, lanes 2, 4, and 5).

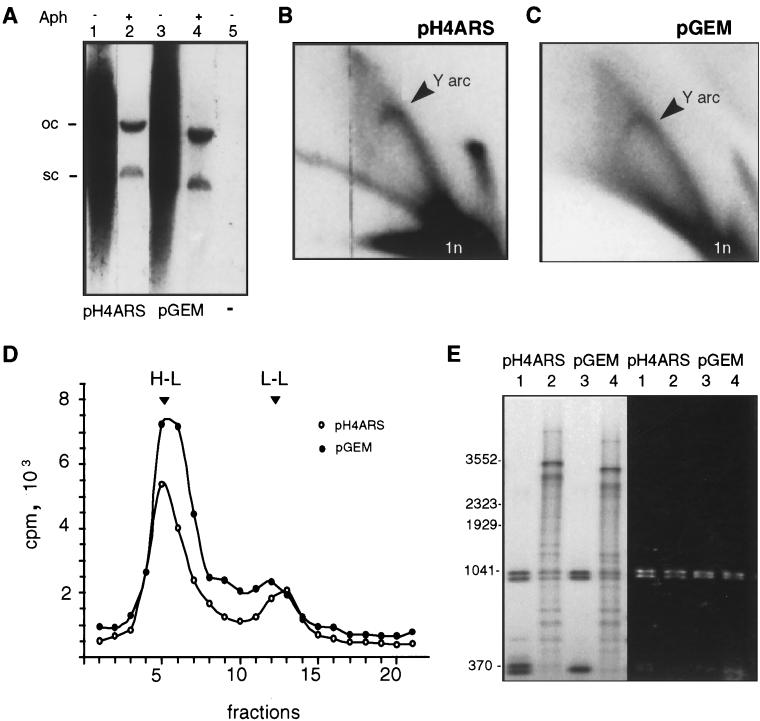

FIG. 1.

DNA replication in nuclear extracts is ARS independent. (A) pH4ARS or pGEM (300 ng) was incubated in a GA-59 S-phase nuclear extract with all nucleotides and [α-32P]dATP for 90 min at 25°C as described in Materials and Methods. Shown is an autoradiograph of the replicated DNA separated on a 0.8% agarose gel. Lanes 1 and 3, complete reactions with pH4ARS and pGEM, respectively. Lanes 2 and 4, like lanes 1 and 3 but with the addition of aphidicolin (Aph) at 500 μg/ml. Lane 5, no DNA added OC, open circular; SC, supercoiled. (B and C) Replication reactions were carried out as described for lanes 1 and 3 in panel A. The DNA was extracted, digested with EcoRI, and visualized by neutral-neutral 2D gel electrophoresis (7). Autoradiograms of dried gels are shown; the Y arc and one linear molecule (ln) are indicated. (D) For BrdUTP substitution, replication reactions were performed for 3 h at 23°C with 300 ng of supercoiled pH4ARS or pGEM in a GA-59 S-phase extract. BrdUTP replaces dTTP, and [α-32P]dATP is added as a tracer (see Materials and Methods). Replicated DNA was extracted and filtered with Sephadex G-50, and recovery was checked by analyzing 25% of the reaction on an ethidium bromide-stained gel. Following CsCl gradient centrifugation of the remaining DNA, gradient fractions were analyzed for refractive index (η) and 32P incorporation. The H-L peak corresponds to an η of 1.4040, consistent with the migration of fully substituted DNA. The L-L peak (η, 1.4000) corresponds to unsubstituted molecules. (E) Replication reactions were carried out for 3 h with GA-59 S-phase nuclear extract and fully methylated pH4ARS (lane 2) or pGEM (lane 4) as described in Materials and Methods. Following the reactions, replicated DNA was digested with ScaI and DpnI and analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. Complete digestion was monitored by ethidium bromide staining of the gel (right panel) and comparison with the migration of methylated plasmid DNA (i.e., pH4ARS in lane 1 and pGEM in lane 3) digested with DpnI and end labeled by standard procedures (59). The pattern of radioactive bands scanned with a PhosphorImager from the dried gel is shown in the left panel. Numbers at left indicate base pair markers.

To determine whether the irregular migration of the labeled products reflects the presence of replication intermediates (RIs), we analyzed the replicated DNA by 2D gel electrophoresis after linearization. A prominent Y arc, as well as a double Y arc, were observed for both pGEM and pH4ARS (Fig. 1B and C; see Fig. 3B for the 2D gel scheme). With both plasmids we also detected a strong signal that migrated as a linear plasmid; this signal could reflect either an intact plasmid with short regions of repair or fully replicated DNA. We observed no significant differences between the RIs detected for templates with or without ARS elements.

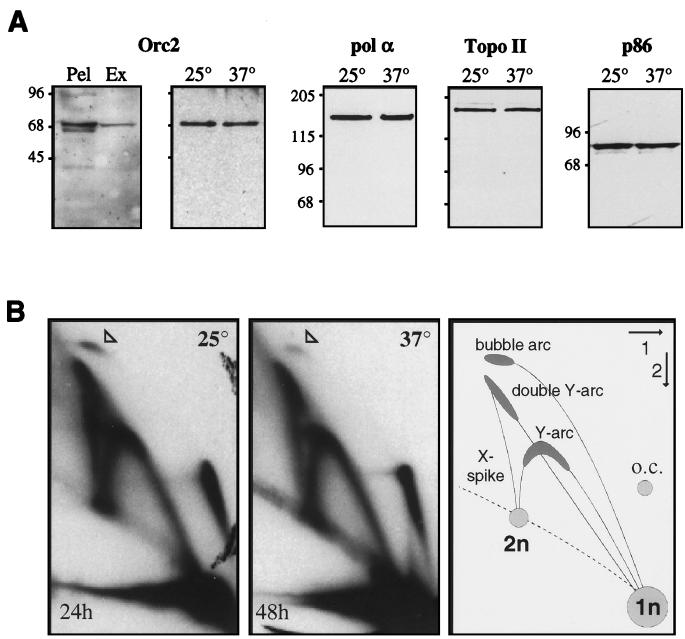

FIG. 3.

The orc2-1 mutation does not abrogate the appearance of RIs during plasmid replication in vitro. (A) Immunoblotting was performed by standard procedures (59). In the first panel, Orc2p in 25 μl of GA-59 S-phase nuclear extract (Ex) and in the insoluble material (Pel) recovered from the same volume of extract (i.e., a fraction rendered insoluble by dialysis) was detected with an anti-Orc2p antibody. The insoluble fraction has the appearance of nuclei under the microscope and may reflect residual structures not removed by centrifugation in high-salt conditions. In the second panel, nuclei from orc2-1 cells (GA-462) grown at 23°C were incubated at either 25 or 37°C for 30 min, and 25 μg of each preparation was probed for Orc2p. In all other panels, 60 μg of GA-59 S-phase extract was incubated for 90 min at either 25 or 37°C as indicated and subsequently analyzed by Western blotting with monoclonal antibody 24D9 against DNA pol α (56), monoclonal antibody 6D2 against p86 (28), or a rabbit polyclonal antibody against topoisomerase II. Secondary antibodies were peroxidase coupled and detected by chemiluminescence. Molecular weight standards (in thousands) are indicated at the left. (B) pH4ARS (300 ng) was incubated at 25 or 37°C in an S-phase nuclear extract prepared from orc2-1 cells (GA-462) for 90 min in the presence of [α-32P]dATP as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. Reaction products were separated by neutral-neutral 2D gel electrophoresis (see Materials and Methods). An arrowhead indicates the top of the putative bubble arc, exposure times are indicated in the lower left corners, and the 2D gel pattern is explained on the right. oc, open circular; n, mass of one plasmid.

Evidence that we were observing semiconservative plasmid replication, as opposed to short patch repair synthesis, was obtained by analyzing the buoyant density of the newly synthesized DNA after substitution with both the heavy base analogue BrdUTP and [α-32P]dATP. Analysis of gradient fractions revealed a prominent peak at the position corresponding to complete second-strand synthesis (H-L DNA) for both the pH4ARS and the pGEM reactions (Fig. 1D). An L-L peak that varied in size, probably representing the repair of nicked substrates (16), was also present. The recovery of DNA prior to the loading of gradients was monitored, and the absolute amount of DNA recovered in each H-L peak could be calculated from the moles of radioactive nucleotide recovered in this fraction. Quantitation of the H-L peaks indicated that 1.9 ng of pH4ARS and 2.6 ng of pGEM were synthesized de novo, representing the semiconservative replication of 0.3 and 0.4% of the input templates. Southern analysis of gradient fractions with the input plasmid confirmed this level of efficiency (data not shown) (see Materials and Methods). Since the use of BrdUTP by replicative polymerases is disfavored over that of dTTP by at least fivefold, the potential replication efficiency of the system may be higher than that suggested by BrdUTP incorporation (discussed in reference 6). Nonetheless, the relevant point is that the quantitation of semiconservative DNA replication in reactions with either pGEM or pH4ARS indicated that the two plasmids replicate with approximately equal efficiencies.

Further confirmation that we were observing complete semiconservative replication of both pGEM and pH4ARS was obtained by digesting the radiolabeled replication products with DpnI, which cuts only fully methylated substrate DNA. When a methylated plasmid is used as a template, the semiconservatively replicated products are hemimethylated and insensitive to DpnI digestion. The digestion patterns of the products from the replication of methylated pH4ARS or pGEM (Fig. 1E, left panel, lanes 2 and 4) showed that approximately 80% of [α-32P]dATP incorporation was associated with DpnI-resistant DNA for both plasmids (pH4ARS, 86%; pGEM, 79%). The migration pattern of fully cleaved, methylated plasmid DNA is shown in Fig. 1E, left panel, lanes 1 and 3. Visualization of the ethidium bromide-stained gel confirmed that all DNA recovered from the replication reaction was digested to completion (Fig. 1E, right panel, lanes 2 and 4).

Initiation is not strictly localized to an ARS element.

The experiments shown in Fig. 1 indicated that the replication of supercoiled templates does not require an ARS element and suggested that sites of initiation might be dispersed along the plasmid sequence. This idea is consistent with the fact that we did not observe the arc indicative of a localized bubble and only rarely detected the very top of the bubble arc on 2D gels of linearized products (see Fig. 3B for an example). Since our template was small and the replication fork progresses quickly (3.7 kb/min in vivo) (25), we surmised that by assaying after 90 min, we might be favoring the detection of late or stalled RIs. However, pooling of aliquots taken at 2.5-min intervals between 0 and 15, 17.5 and 30, and 32.5 and 45 min failed to increase the bubble arc intensity (data not shown). The absence of the bubble arc was not due to inappropriate linearization of the plasmid, since digestion with EcoRI (which is adjacent to the ARS consensus of pH4ARS) or with ScaI (which cuts at a point 180° from the ARS consensus) yielded the same RIs on 2D gel analysis (Fig. 2A). Despite this result, a pronounced arc corresponding to a bubble within a circle was detected when nonlinearized replication products were analyzed on 2D gels (see reference 6). We can reconcile these results with two models: (i) initiation in this system is a poorly localized event or (ii) initiation is restricted to a specific site, but during digestion and reisolation of the replicated plasmid, bubble structures are artifactually converted to asymmetric Y arcs by breakage near the fork.

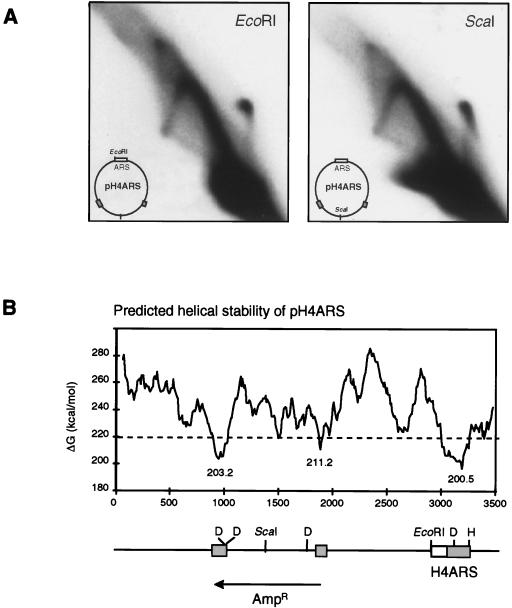

FIG. 2.

Initiation does not map specifically to the ARS consensus. (A) The replication reaction mixture described in Fig. 1A was scaled up, so that 600 ng of pH4ARS and 120 μg of wild-type S-phase extract (GA-59) were used. The recovered DNA was linearized with EcoRI or ScaI, and products were analyzed by 2D gel electrophoresis. Autoradiographs of dried gels are shown. Maps of the plasmids indicating the sites of relevant restriction enzymes are shown. (B) The helical stability of the pH4ARS plasmid (ΔG values) was calculated as described by Marilley and Pasero (43). A linear map of the plasmid is shown under the graph; DNA-unwinding elements (66) are indicated by grey boxes and H4ARS is indicated by an empty box. D, DraI; H, HindIII. These sites were used to quantify label incorporation into appropriately restricted DNA (see the text).

As an alternative method for mapping sites promoting initiation, we quantified the label incorporated into defined restriction fragments of the pH4ARS template after 9 min of incubation of the standard replication reaction. After normalization of the moles of [α-32P]dATP incorporated to the size and AT content of the respective fragments, a DraI fragment overlapping the β-lactamase (Ampr) gene located between two regions of helical instability (or DNA-unwinding elements) (66) (Fig. 2B) was found to be fivefold more highly labeled than adjacent fragments, while the next most highly labeled fragments contained H4ARS (data not shown). These regions represent sequences that are readily denatured under tortional stress (Fig. 2B); hence, initiation appears not to be localized to one site but rather to occur where strand separation is favored.

Replication of plasmid DNA in S-phase extracts does not require components of the pre-RC.

It has been proposed that the S-phase Cdk1 kinases modify components of the pre-RC, preventing their reassembly into a complex competent for reinitiation (12; reviewed in reference 47). Thus, the lack of origin dependence for initiation could reflect an inhibition of pre-RC assembly, the absence of ORC, or even the promiscuous binding of ORC to multiple sites in the plasmid. To ascertain whether ORC is present in our extracts, we probed for the presence of the 72-kDa subunit, Orc2p, by Western blotting. Although a large fraction of this protein was lost in an insoluble fraction that was removed by centrifugation after dialysis of the extract, Orc2p was readily detected in the nuclear extract used for replication (Fig. 3A, compare Pel and Ex). Moreover, Orc2p and other replication enzymes, such as pol α, p86, and topoisomerase II, were stable after incubation at 37°C, mimicking the replication assay conditions for temperature-sensitive extracts (Fig. 3A).

To test whether ORC is necessary for replication, S-phase nuclear extracts were prepared at the permissive temperature from a temperature-sensitive orc2-1 mutant after α-factor blocking and release (GA-462; see Materials and Methods). Replication reactions with supercoiled pH4ARS were carried out at permissive (25°C) and restrictive (37°C) temperatures and analyzed by 2D gel electrophoresis. Similar patterns of RIs were present at both temperatures, as indicated by α-32P-labeled Y arcs, double Y arcs, X spikes, and the top of a weak bubble arc (Fig. 3B), although incorporation efficiency was slightly lower at 37°C (Fig. 3B). When G1-phase orc2-1 nuclei were used as templates in an in vitro replication system, replication was completely inhibited at 35°C, although wild-type nuclei replicated normally at this temperature (53). We conclude that the appearance of RIs in naked plasmid templates in vitro is largely ORC independent.

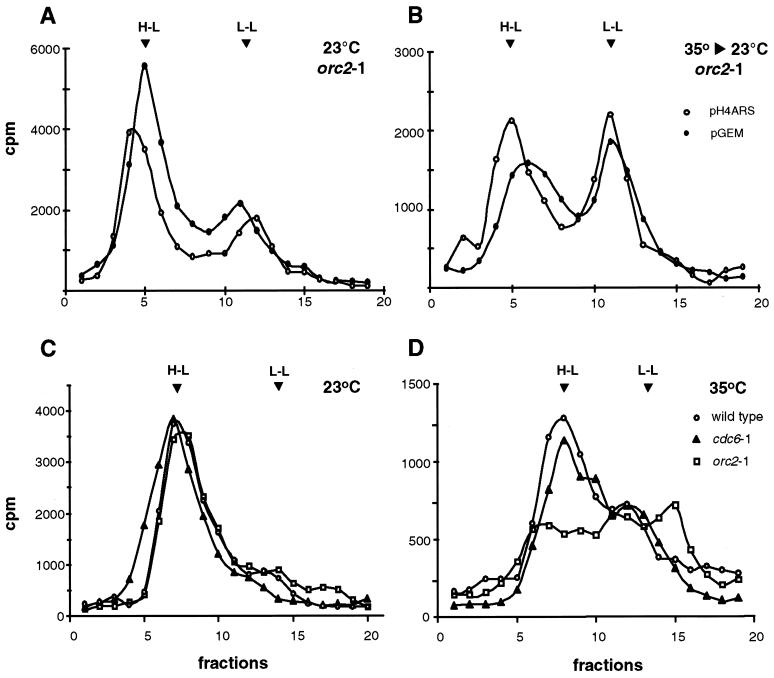

To obtain a quantitative measure of semiconservative replication under these conditions, we examined similar replication reactions with an S-phase orc2-1 extract prepared at the permissive temperature by using BrdUTP substitution and gradient analysis. Both pGEM and pH4ARS were tested as substrates. Since the orc2-1 deficiency is rapidly induced and is irreversible (53), we preincubated the extract for 15 min at 35°C to inactivate Orc2p and then shifted the reaction mixture to 23°C for the 3-h replication reaction. The control reaction mixture was kept continuously at 23°C. Buoyant density analysis of the reaction mixtures demonstrated that the semiconservative replication of both pGEM and pH4ARS in the orc2-1 extract occurred independently of the 35°C preincubation (Fig. 4B). Although the overall level of replication in the temperature-shifted extract was reduced (compare Fig. 4A and B), this reduction was observed in many wild-type extracts as well (data not shown). Importantly, the drop in efficiency for the orc2-1 extract at 35°C was the same for both pGEM and pH4ARS, suggesting that the partial temperature sensitivity was not due to inactivation of ARS-bound ORC, since pGEM carries no ARS element.

FIG. 4.

Semiconservative DNA replication in nuclear extracts requires neither Cdc6p nor intact ORC. (A) BrdUTP-containing replication reactions (Fig. 1D) were performed in parallel with 300 ng of either pH4ARS (open circles) or pGEM (filled circles). Incubation was done at 23°C for 3 h with a GA-462 (orc2-1) S-phase extract prepared at the permissive temperature. The reactions were preceded by 15 min of preincubation at 23°C of all components except DNA. Following replication, the DNA was purified, recovery was quantified, and 75% of the reaction was separated on a CsCl density gradient. All fractions were monitored for refractive index and 32P incorporation. Peaks corresponding to the migration of H-L and L-L molecules are indicated. (B) Reactions identical to those in panel A were performed, except that reaction mixtures were preincubated at 35°C and then cooled to 23°C before the addition of DNA. (C and D) Similar BrdUTP-containing replication reactions were performed with 300 ng of supercoiled pH4ARS in GA-59, GA-462 (orc2-1) or GA-315 (cdc6-1) S-phase nuclear extracts, all prepared at the permissive temperature. Incubation was done for 3 h at either 23°C (C) or 35°C (D). Replicated DNA was separated on CsCl density gradients. The expected migration of H-L and L-L molecules is indicated by arrowheads. Incorporation was lower at 35°C for all strains tested (see the y axis for counts per minute).

Similar reactions were carried out in parallel with S-phase extracts from a wild-type strain (GA-59), a temperature-sensitive Cdc6p mutant (GA-315), and the orc2-1 strain (GA-462) with pH4ARS as a substrate. Replication reactions were carried out at 23 or 35°C continuously for 3 h, and BrdUTP incorporation was evaluated by buoyant density analysis. Although the orc2-1 extract again showed a slight temperature-induced impairment compared to the wild-type extract, replication in the cdc6-1 strain at the restrictive temperature showed incorporation equivalent to that of the wild-type control (compare Fig. 4C and D). Together, these results suggest that semiconservative plasmid replication occurs in S-phase nuclear extracts in an origin- and Cdc6p-independent manner, consistent with the model that S-phase kinases prevent the formation in this case on template pre-RC plasmid (15, 47).

The partial inactivation observed in the orc2-1 extract may reflect nonspecific interference with the replication machinery by an improperly assembled ORC. This idea is corroborated by the fact that titration of a 1- to 10-fold molar excess of recombinant ORC into a wild-type S-phase reaction mixture at 25°C also progressively lowered replication efficiency (data not shown). This result was obtained with either pGEM or pH4ARS as a template. Since it is highly unlikely that a pre-RC can assemble in an S-phase extract, we interpreted these results as an indication that an excess of unassembled ORC can interfere with the functioning of the replication machinery, although we do not know which component is affected.

Semiconservative DNA replication is impaired by a conditional mutation in CDC28 but not in CDC7.

In our initial studies of replication in vitro, we readily observed Y arcs on 2D gels following reactions with S-phase nuclear extracts but not with nuclear extracts prepared from pheromone-arrested G1-phase cultures (6) (see also Fig. 6A and B). Western blotting of equivalent aliquots of nuclear extracts from either unsynchronized cells or cells synchronized in G1, S, or M phase indicated that the levels of many replication-related proteins did not vary significantly through the cell cycle (data not shown; pol α, p180, and p86 subunits, PCNA, RPA, topoisomerase II, and the third subunit of replication factor [RF-C] were tested). In view of this result, the obvious candidates for rendering our in vitro replication reaction cell cycle dependent were the S-phase-promoting kinases Cdc28p and Cdc7p (34, 48).

FIG. 6.

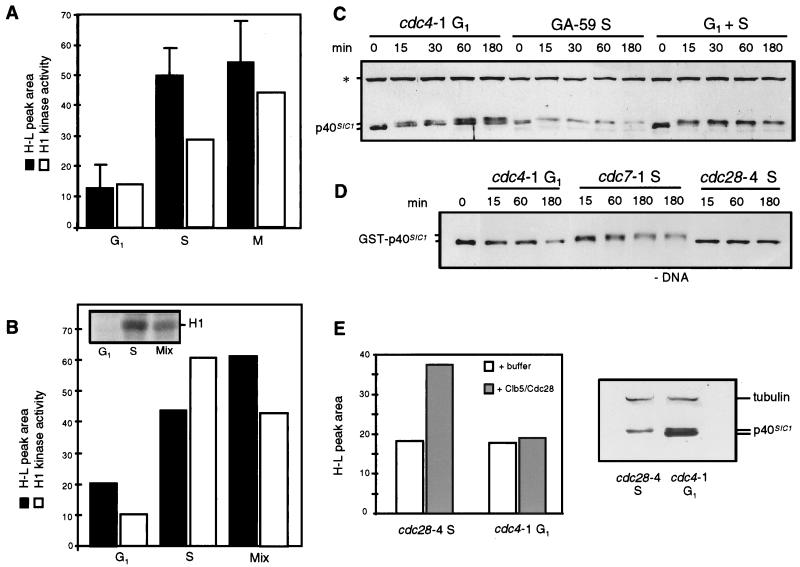

Replication efficiency and modification of P40SIC1 in nuclear extracts vary in a cell-cycle-dependent manner. (A) Quantitation is shown for integrations of the H-L peaks (black bars) from multiple BrdUTP substitution reactions performed for 3 h at 23°C with 40 μg of a G1-phase (cdc4-1; GA-1087), an S-phase (GA-59), or an M-phase (cdc16-1; GA-161) nuclear extract and 300 ng of template as described in Materials and Methods. Buoyant density analysis was performed on replicated DNA after plasmid recovery was checked. For the cdc4-1 G1-phase extract and the GA-59 S-phase extract, five reactions were performed under identical conditions, and the area of the H-L replication peak following CsCl gradient analysis of each was quantified in arbitrary units (for the cdc4-1 extract, the mean was 13.2 [standard deviation, 7.6]; for the GA-59 extract, the mean was 50 [standard deviation, 8.7]). Three reactions with the cdc16-1 M-phase extract were performed in parallel (mean, 54.6 [standard deviation, 14.4]). Comparative replication reactions were always performed with identical template preparations. The relative H1 kinase activities for equal aliquots of the extracts are indicated by white bars. (B) Replication reactions were performed as in panel A with 40 μg of a G1-phase nuclear extract (GA-1087), 40 μg of a wild-type S-phase extract (GA-360), or a mixture of 20 μg of each. Reactions were performed in parallel for 3 h at 23°C with 300 ng of pGEM. The H-L peaks of the CsCl gradients were integrated (black bars). Histone H1 kinase assays were done with the cdc4-1 G1-phase extract (GA-1087), the S-phase nuclear extract (GA-360), and a 1:1 mixture of the two. An autoradiograph of the kinase assays is shown in the inset, quantiation in arbitrary units is shown by white bars. (C) Immunodetection of endogenous p40SIC1 in a series of replication reactions allowed to proceed at 23°C for the times indicated. Reaction mixtures contained 40 μg of a wild-type S-phase extract (GA-59), 40 μg of the cdc4-1 G1-phase extract (GA-1087), or a mixture of 20 μg of each and 300 ng of pGEM but no radioactive dATP. Loading buffer (4×; 200 mM Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], 400 mM DTT, 8% SDS, 0.4% bromophenol blue, 40% glycerol) was added to equal samples taken at the indicated time. p40SIC1 was detected by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-p40SIC1 serum. The lower band of P40SIC1 was presumably already modified by Cln/Cdc28, and a rapid and complete shift to a slower mobility was detected during incubation in the S-phase extract or in the mixture of extracts but not in the G1-phase extract. The asterisk indicates an unrelated cross-reacting polypeptide that served as an internal loading standard. As expected, levels of P40SIC1 were lower in the S-phase extract. (D) Bacterially expressed GST p40SIC1-Myc-His6 (GST-p40SIC1) (see Materials and Methods) was added at a concentration of 0.8 ng/μl to replication reactions carried out as described for panel C but with cdc4-1 (GA-1087) G1-phase or cdc7-1 (GA-85) or cdc28-4 (GA-112) S-phase nuclear extracts prepared as described in Materials and Methods. DNA was omitted from one of the reactions with the GA-85 S-phase extract (−DNA). Immunoblotting was carried out as described for panel C but with an anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (9E10). The 0 time point represents input GST-p40SIC1-Myc-His6. (E) Integration of the H-L replication peaks determined from quantitative buoyant density analysis of BrdUTP-containing replication reactions is shown in arbitrary units. These reactions were performed for 3 h at 23°C with 300 ng of pRS424 DNA and 40 μg of GA-112 (cdc28-4) S-phase or GA-1087 (cdc4-1) G1-phase nuclear extract, either with (grey bars) or without (white bars) the addition of 2 U of baculovirus-expressed Clb5-Cdc28 (see Materials and Methods). To the right, Western blot analysis for p40SIC1 was performed as described for panel C but with 40-μg aliquots of the GA-112 (cdc28-4) S-phase or GA-1087 (cdc4-1) G1-phase nuclear extract. The analysis showed that the latter had higher levels of p40SIC1. As shown in panel C, p40SIC1 in the G1-phase extracts had faster mobility.

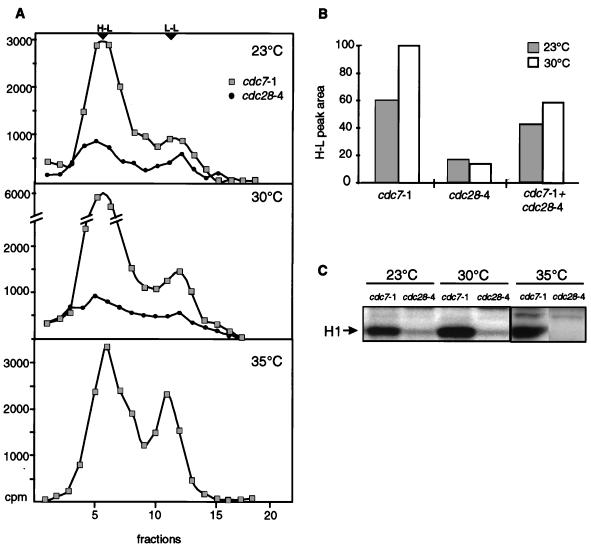

To examine their roles, S-phase nuclear extracts were prepared at the permissive temperature from the conditional cdc28-4 strain (GA-112) and by temperature-sensitive arrest of the cdc7-1 mutant (GA-85). Extracts were monitored for their abilities to phosphorylate histone H1 and to promote semiconservative DNA replication in vitro. As previously reported, H1 kinase activity in the cdc28-4 mutant was very low even at the permissive temperature (23°C) (Fig. 5C) (60) and, as expected, H1 kinase activity in the cdc7-1 mutant was intact at all temperatures tested (23, 30, and 35°C) (Fig. 5C). Two unidentified polypeptides in the cdc7-1 nuclear extract showed temperature-sensitive modification and may have represented physiological substrates of this kinase (data not shown). When these extracts were used in the in vitro replication assay, a very low level of semiconservative DNA replication in the cdc28-4 extract at 23°C was reduced further at 30°C (Fig. 5A). The cdc7-1 extract, on the other hand, supported efficient replication at all temperatures tested (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Replication in vitro is sensitive to the loss of Cdc28 but not Cdc7 kinase. (A) BrdUTP-containing replication reactions were carried out for 3 h at 23, 30, or 35°C (for cdc7-1 only) as described in Materials and Methods with 40 μg of S-phase nuclear extract from either GA-112 (cdc28-4) prepared at the permissive temperature or GA-85 (cdc7-1) synchronized by a temperature shift (see Materials and Methods). All reactions were performed in parallel with 300 ng of pH4ARS as a template, and equal recovery of the plasmid was checked prior to CsCl gradient analysis. Cerenkov counts of the fractions from the CsCl gradients are shown. Fractions with refractive indices appropriate for H-L and L-L DNAs are indicated. The increase in the replication efficiency of the cdc7-1 extract at 30°C compared to that at 23°C was also observed for the wild-type extract (data not shown). (B) Parallel reactions like those in panel A were performed at 23 and 30°C for 3 h with 40 μg of a 1:1 mixture of cdc28-4 and cdc7-1 extracts. DNA recovery was monitored. After CsCl gradient analysis, the relative levels of replication supported by each extract at 23 or 30°C or by the 1:1 mixture were quantified by integration of the H-L replication peak. Relative values are expressed as arbitrary units. (C) Histone H1 kinase assays were performed at the indicated temperatures as described in Materials and Methods with equal amounts of the cdc28-4 and cdc7-1 extracts (see panel A). Histone H1 is indicated. Although we did not detect H1 modification in the cdc28-4 extract at 23°C, this extract showed temperature-sensitive promotion of replication in G1-phase nuclei in vitro (see Materials and Methods).

To rule out the possibility that the cdc28-4 extract contains nonspecific inhibitors of replication (e.g., nuclease or protease activities), we performed identical replication reactions in parallel by using a 1:1 mixture of the cdc28-4 and cdc7-1 extracts at either 23 or 30°C and keeping the final protein concentration constant. The peaks of H-L DNA from buoyant density analyses of the individual extracts and the mixture were integrated and are presented in Fig. 5B. The levels of semiconservative DNA replication in the mixture were higher than the average for equal amounts of the two extracts alone, indicating that the cdc28-4 extract is competent for replication when Cdc28p is provided in trans. Cdc28p may, however, still be limiting for maximal replication efficiency. This hypothesis is examined further below. In conclusion, semiconservative DNA replication in vitro shows a pronounced dependence on Cdk1 kinase activity but not on that of Dbf4-Cdc7 kinase.

Cell-cycle-dependent stimulation of replication correlates with alterations in the p40SIC1 inhibitor.

The protein p40SIC1 is a physiological inhibitor of the Clb5-Cdc28 complex that accumulates during G1 phase and that becomes phosphorylated, ubiquitinated, and degraded at the G1/S transition point (14, 26, 36). If the critical, limiting activator for semiconservative replication in vitro is the Clb5-Cdc28 kinase, we reasoned that extracts prepared from cells that accumulate p40SIC1 should be inactive for replication. If the required Clb-Cdk1 activity is not restricted to Clb5-Cdc28, then M-phase nuclear extracts may actively support replication. To test these hypotheses, we prepared a late-G1-phase nuclear extract from cdc4-1 cells (GA-1087) arrested at 37°C due to the inactivation of the complex that targets p40SIC1 for degradation (14, 26). This extract was compared to a wild-type S-phase extract and a cdc16-1 M-phase extract prepared from cells blocked in mitosis by a similar temperature shift. The arrest by the temperature shift inactivates Cdc16p, which is needed to target B-type cyclins for degradation at the metaphase-anaphase transition (2). Replication reactions were performed in parallel at the permissive temperature, and H-L DNA was monitored by buoyant density analysis.

As demonstrated by calculating the mean ± standard deviation for five independent experiments, the late-G1-phase extract (cdc4-1) was four- to fivefold less efficient at promoting semiconservative DNA replication than the wild-type S-phase extract (Fig. 6A). The recovery of DNA was checked for each reaction, and identical templates were used when different extracts were compared. The cdc16-1 mitotic extract supported semiconservative DNA replication at levels comparable to those obtained with the S-phase extract (Fig. 6A). The histone H1 kinase activity measured in these extracts correlated well with both the replication efficiency and the maintenance of a G1 form of p40SIC1 (Fig. 6A and C).

To demonstrate that the deficiency of the cdc4-1 extract can be overcome by a kinase-containing extract, we monitored semiconservative replication in parallel reactions performed at 23°C with a wild-type S-phase extract, a cdc4-1 G1-phase extract, and a 1:1 mixture of the two, such that the final protein concentration was maintained. When mixed, the extracts had a synergistic effect on replication efficiency, although the H1 kinase activity dropped slightly relative to what was observed with the S-phase extract alone (Fig. 6B). The synergy observed with the mixture indicated that the low level of replication in the cdc4-1 extract was not artifactual and suggested that the p40SIC1 inhibitor in this extract was either inactivated or overwhelmed by the S-phase extract.

To monitor the fate of the p40SIC1 inhibitor during these three reactions, we probed equal aliquots from the replication assay with antibodies specific for p40SIC1 (Fig. 6C). First, as expected, p40SIC1 was far more abundant in the G1-phase extract than in the S-phase extract (Fig. 6C and E). Second, in both the S-phase extract and the G1-phase–S-phase extract mixture, all p40SIC1 was rapidly converted to a slower-migrating form detected by Western blotting (Fig. 6C). This shift was presumably due to phosphorylation by Clb-Cdc28 (Fig. 6D) (see below) and was presumably superimposed on the endogenous phosphorylation state conferred on the protein by G1-phase kinase activities (67). In contrast, only a fraction of endogenous p40SIC1 showed altered mobility as a result of the 3-h incubation in the cdc4-1 extract. This partial modification may indicate that even in the cdc4-1 extract some phosphorylation of endogenous p40SIC1 can occur presumably by Cln-dependent kinases. Although we added no ubiquitin and hence no proteasome-mediated degradation of p40SIC1 occurred in our system (26, 67), we cannot exclude the possibility that the additional phosphorylation partially inactivated the inhibitor. In any case, the persistence of a significant level of the G1 form of p40SIC1 correlated with the low-level replication observed in the cdc4-1 extract (Fig. 6A and B). Moreover, the observation that all of the G1-phase p40SIC1 in the cdc4-1 extract became modified when mixed with an S-phase extract correlated with the elevated replication efficiency obtained when the two extracts were mixed (Fig. 6B).

Evidence that the shift in the mobility of endogenous G1-phase p40SIC1 reflected modification by a Cdc28p kinase complex was obtained by incubating a recombinant GST-p40SIC1 fusion with different nuclear extracts in mock replication reactions at the permissive temperature, followed by Western blotting to detect the recombinant protein (Fig. 6D). In the cdc4-1 G1-phase extract there was no detectable shift in the mobility of the fusion protein, whereas a pronounced shift upward was detected after incubation in the cdc7-1 S-phase extract, even in the absence of template DNA (Fig. 6D, DNA, 180 min). This shift was lost in the cdc28-4 S-phase extract, suggesting that it was Cdc28p dependent. In summary, both endogenous p40SIC1 and a GST-p40SIC1 fusion become modified and partially destabilized in S-phase extracts in vitro. When we added recombinant GST-p40SIC1 to a wild-type S-phase reaction, semiconservative DNA synthesis was inhibited (22a), however, it is difficult to interpret this result, since the addition of the GST moiety alone also interfered with the reaction (see Materials and Methods). To correctly demonstrate repression of replication, we may need to isolate a nonphosphorylatable form of p40SIC1 lacking the GST domain.

Cdk1p is necessary and sufficient to stimulate semiconservative DNA replication in G1-phase extracts.

To confirm that the minimal replication level observed in the cdc28-4 S-phase extract reflected the absence of Clb5-Cdc28 kinase activity, we complemented this extract with highly purified baculovirus-expressed Clb5-Cdc28 and performed parallel replication reactions at 23°C (see Materials and Methods). The addition of 2 U of Clb5-Cdc28 was sufficient to double the efficiency of semiconservative plasmid replication in the cdc28-4 mutant extract (Fig. 6E). Lower levels of enzyme resulted in less stimulation, while the addition of 30 or 100 U no longer increased the recovery of H-L DNA (data not shown) (see below). In contrast, 2 U of recombinant Clb-Cdc28 kinase was unable to stimulate replication in the cdc4-1 extract (Fig. 6E). This result was presumably due to the high level of p40SIC1 in the cdc4-1 extract (see Western blot of equivalent extract aliquots in Fig. 6E), which probably inhibited the added kinase (see below).

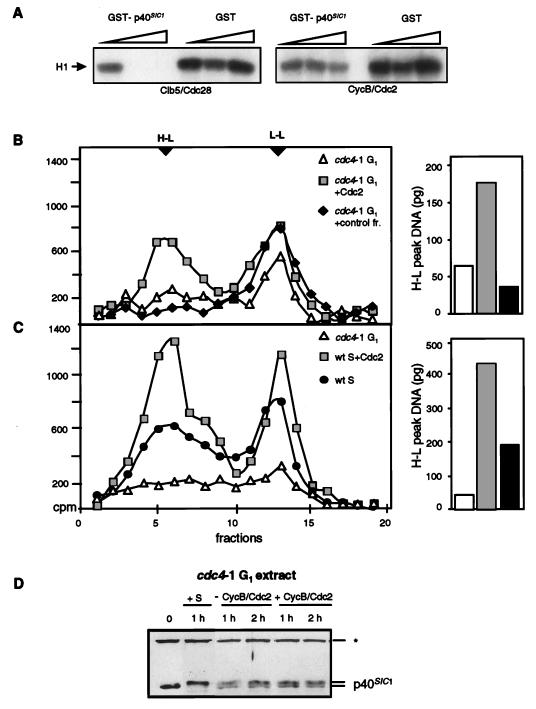

If the lack of replication observed in the cdc4-1 G1-phase nuclear extract is due exclusively to the absence of CycB-Cdk1 activity, it should be possible to activate semiconservative DNA replication in this extract by adding an exogenous Cdk1 kinase that is insensitive to p40SIC1 inhibition. To this end, baculovirus-expressed Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 kinase was isolated from Sf9 cells (12a, 62), and its sensitivity to recombinant p40SIC1 was tested. As shown in the phosphorylation assay in Fig. 7A, titration of the GST-p40SIC1 fusion completely inhibited the activity of Clb5-Cdc28, while the H1 kinase activity of CycB-Cdc2 persisted even at the highest concentration of the inhibitor. The GST moiety itself had no effect on either kinase (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

Addition of mitotic CycB-Cdc2 stimulates replication in both S-phase and G1-phase extracts. (A) Histone H1 kinase assays were performed at 23°C as described in Materials and Methods with 20 U of purified recombinant Clb5-Cdc28 or CycB-Cdc2 and with increasing concentrations (0.16, 0.8, and 4 μM) of either bacterially expressed GST-p40SIC1-Myc-His6 (GST-p40SIC1) or GST alone in a 10-μl reaction volume. Histone H1 is indicated. (B and C) CsCl gradient analyses of BrdUTP-containing replication reactions performed in parallel with 300 ng of pRS424 and 40 μg of either wild-type (wt) S-phase (GA-811) or cdc4-1 G1-phase (GA-1087) nuclear extract for 3 h at 23°C. Either 10 U of baculovirus-expressed Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 or an equivalent volume of the corresponding fraction (control fr.) from mock-infection Sf9 cells was added to the replication reactions as indicated. The recovery of DNA was checked prior to CsCl gradient analysis (see lanes 5 to 9 of Fig. 8C). Integration of the H-L peaks is shown to the right of the gradient profiles and is given in absolute picograms of replicated DNA. (D) Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 does not stimulate the degradation of P40SIC1 during replication reactions. Replication reactions were performed as described for panel B with 40 μg of a cdc4-1 (GA-1087) G1-phase nuclear extract, either with (+) or without (−) the addition of 10 U of baculovirus-expressed Xenopus CycB-Cdc2. Radioactive nucleotide was omitted. Where indicated (+S), the reaction mixtures contained 20 μg each of the G1-phase (GA-1087) and wild-type S-phase (GA-811) extracts. Samples taken after 1 or 2 h and input G1-phase extract (0 time point) were analyzed by Western blotting for endogenous p40SIC1 as described in the legend to Fig. 6. The asterisk indicates a cross-reacting polypeptide that was used as a loading control.

A series of replication reactions was then performed at 23°C with the cdc4-1 G1-phase nuclear extract with or without the addition of 10 U of Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 kinase or a control fraction from Sf9 cells containing no H1 kinase activity. Buoyant density analysis of the replication products from a typical reaction revealed virtually no H-L peak after 3 h of incubation of a supercoiled template with the extract alone or with the extract plus a control fraction (Fig. 7B). The addition of Xenopus CycB-Cdc2, on the other hand, promoted semiconservative replication to the same level as that in an S-phase extract tested with the same substrates under identical conditions (compare integrated H-L peaks in the right-hand panels of Fig. 7B and C). The recovery of DNA from all reactions was shown to be equivalent by gel electrophoresis (see Fig. 8C), and the peak of H-L DNA increased reproducibly about threefold in the presence of Xenopus CycB-Cdc2. Much higher levels of recombinant enzyme (30 U) were not able to stimulate replication, a result which may indicate that an excess of kinase activity counteracts its own stimulatory action (data not shown). This possibility is consistent with the observation that phosphorylation of the mammalian pol α-primase complex by CycA-Cdk2 can be inhibitory (68). However, to understand the relevance of these in vitro effects requires further study. The fact that the cdc4-1 G1-phase extract was stimulated by a mitotic CycB-Cdc2 kinase supports genetic data suggesting that the mitotic B-type cyclins of yeast can substitute for Clb5p and Clb6p in vivo (60).

CycB-Cdc2 kinase stimulates replication in cdc28-4 and wild-type S-phase extracts.

The observation that the cdc28-4 S-phase extract was deficient for semiconservative DNA replication suggested that Clb-Cdc28 kinase activity is required continuously during DNA synthesis and not simply to inactivate an inhibitor of replication at the G1/S boundary. Since our S-phase extracts still contained a low level of p40SIC1 (Fig. 6), it seemed possible that Clb-Cdk1 activity was limiting for replication even in the wild-type S-phase extract. To test this possibility, we added 10 U of purified Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 to the standard replication assay with a wild-type S-phase extract. BrdUTP incorporation was monitored by buoyant density analysis, and the recovery of DNA was systematically quantified (see Fig. 8C). The addition of 10 U of CycB-Cdc2 to the wild-type S-phase extract stimulated replication over the control level (2.5-fold) (Fig. 7C), while the addition of a control fraction had no effect (data not shown). As an internal standard, replication in the cdc4-1 extract was assayed in parallel, and the H-L peaks were quantified by integration (Fig. 7B and C). In conclusion, Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 stimulated replication in both S-phase and cdc4-1 G1-phase nuclear extracts.

To determine whether this activation reflected the phosphorylation of replicative enzymes by the Xenopus kinase directly or was an indirect effect achieved by inactivation of p40SIC1 (which would, in turn, release endogenous Clb-Cdc28 kinase), we blotted p40SIC1 after incubation in the cdc4-1 replication mixture with or without exogenous Xenopus CycB-Cdc2. p40SIC1 did not shift quantitatively to the slower-migrating form in the cdc4-1 extract as it did in an S-phase extract (Fig. 7D), nor were p40SIC1 levels significantly reduced, suggesting that the exogenous CycB-Cdc2 kinase acts directly rather than by modifying p40SIC1.

Can the purified Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 kinase alone restore replication to the Cdk1-deficient cdc28-4 extract? To test this idea, 10 U of recombinant Xenopus enzyme was added to a replication reaction performed with the cdc28-4 S-phase extract and BrdUTP at 23°C. Equal fractions of template DNA (pRS424) were recovered after the reaction (Fig. 8C) and were subjected to buoyant density analysis. The gradient profile in Fig. 8A shows that a significant H-L peak was recovered when recombinant Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 was added to the cdc28-4 extract. Two controls were used to confirm that the stimulation was due to the kinase activity of CycB-Cdc2. First, as shown in Fig. 8B, the kinase fraction was treated with agarose beads complexed with GST-Cip1p, a specific inhibitor of the vertebrate Cdc2 kinase, or with GST alone. After removal of the beads, the soluble fraction was added to the replication reaction described above. Equal amounts of recovered DNA were analyzed by buoyant density analysis. Consistent with a requirement for Cdk1 activity, the GST-treated kinase fraction stimulated semiconservative DNA replication, while the Cip1-treated kinase fraction did not (Fig. 8B). Histone H1 kinase assays confirmed that the Xenopus enzyme was active prior to Cip1p treatment and that it was inhibited by treatment with GST-Cip1p but not GST alone (Fig. 8D). As a further control, Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 was either mock treated or inactivated by reductive alkylation (see Materials and Methods) prior to its addition to replication reactions identical to those shown in Fig. 8A and B. The inactivated kinase fraction did not promote replication, whereas sequential additions of the kinase and the premixed NEM-DTT solution stimulated semiconservative DNA replication to the level observed in Fig. 8A (data not shown). Together, these results confirmed that a mitotic CycB-Cdk1 kinase complex is sufficient to complement the replication-promoting defect in a cdc28-4 S-phase extract as well as to stimulate a G1-phase extract that contains high levels of endogenous p40SIC1.

DISCUSSION

Coordination between the cell cycle and the initiation of DNA replication in budding yeast depends primarily on the assembly of proteins at the origin of replication and trans-activating cyclin-dependent kinases. The pre-RC that assembles in G1 phase is altered as origins fire and usually requires passage through mitosis to render it competent for reinitiating DNA replication (47, 48). The exact composition of the proteins that form the pre-RC is still unclear, and much remains to be learned about how S-phase-promoting kinases stimulate both the initiation and the subsequent elongation steps of DNA replication. The possibility that pre-RC-independent initiation can occur in yeast has not been excluded, since orc mutants do progress partially through the S phase at the restrictive temperature (3), and a chromosome III fragment lacking functional ARS elements can be replicated (48a). Here we examined an in vitro replication system from budding yeast cells that initiates DNA replication in the absence of pre-RC formation. We demonstrated a cell cycle dependence of this reaction, which is most simply explained as a requirement for CycB-Cdk1 activity. Our results suggest that the S-phase Clb-Cdc28 complex does more than dismantle the ORC-dependent pre-RC at the G1/S transition to promote genomic DNA replication.

The semiconservative replication of supercoiled plasmid templates in vitro requires the activity of the pol α-primase complex, pol δ, and the Dna2 helicase (6). Consistently, the reaction requires ribonucleotides and can be inhibited both by antibodies that inactivate pol α and by aphidicolin, suggesting that this system retains mechanistic aspects of genomic DNA replication. However, unlike replication in intact cells or the replication of nuclear templates in vitro (53), initiation occurs in the absence of an ARS consensus and independently of two essential components of the pre-RC, ORC and Cdc6p (Fig. 3 and 4) (64). Preliminary depletion data suggested that the reaction is MCM independent as well (31a). These unconventional initiation events may reflect the ability of pol α-primase to associate with chromatin in a pre-RC-independent manner, as reported by Desdouets et al. (13), yet these authors found the chromatin association to be inhibited by Clb-Cdk1 kinases (see below). Alternatively, gene conversion-type events which lead to chromosome replication may occur in vitro, although the appearance of RIs in our system does not require RAD52 and is not stimulated by the addition of homologous single-stranded DNA (6).

In S-phase extracts from an orc2-1 mutant, we still detected semiconservative plasmid replication at the nonpermissive temperature, although the efficiency was reduced. Since this finding was true even for plasmids that lacked an ARS consensus, we assumed that it reflected either the temperature-induced lability of another component or indirect interference in initiation due to dissociation of the ORC. Consistent with this latter hypothesis, we also detected the inhibition of plasmid replication in S-phase extracts when baculovirus-expressed ORC was titrated into the reaction (31a). Since this finding also occurred with templates lacking an ARS consensus, it suggests that an excess of “free” ORC can repress replication. Surprisingly, in preliminary experiments, we found that the repressive effect of exogenous ORC was reproducibly counteracted by preincubating the complex and template with a G1-phase extract prior to adding the S-phase extract to promote replication. Such results may be the first steps in reconstituting a functional pre-RC, which may require the assembly of ORC, Cdc6p, Dbf4-Cdc7p, MCM, and perhaps nucleosomes on templates in extracts that lack Clb-Cdc28 activity (15, 48). A reconstituted origin may then be able to fire in an origin-specific manner, like the initiation observed in isolated G1-phase nuclei (53).

Because the replication that we detected in extracts occurred in the absence of pre-RC formation, we were surprised to find it subject to cell cycle controls. While this finding might reflect the availability of a limiting replication enzyme, we detected no major variations in the levels of the common replication factors throughout the cell cycle. With both conditional mutants and reconstitution assays, we showed here that CycB-Cdk1 activity but not that of Dbf4-Cdc7 kinase, appeared to be limiting for ORC-independent initiation events in vitro. Notably, the inefficient plasmid replication supported by the cdc28-deficient extract could be complemented by adding an equivalent amount (2 U) of purified Clb5-Cdc28 complex or 10 U of Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 complex. Titrations showed less stimulation when smaller amounts were added and inhibition when a vast excess of kinase was added (30 to 100 U) (data not shown). If this inhibition is not artifactual, it may mean that optimal kinase levels are carefully balanced in the cell and that excessively high Clb-Cdk1 levels play a role in downregulating DNA polymerase activity. Such fine-tuning of DNA replication may be one function of the CLB3 and CLB4 gene products that accumulate during S phase (48). Although the interpretation of these results requires further analysis, there are many precedents for differential phosphorylation patterns of a given protein regulating activity in opposite directions (see the discussion of DNA pol α-primase complex below and reference 67).

Activation of a late-G1-phase extract by Xenopus CycB-Cdk1.

A G1-phase extract from a cdc4-1 strain which accumulated high levels of Cln/Cdc28-modified p40SIC1 at a restrictive temperature supported very low levels of semiconservative plasmid replication. In S-phase extracts, p40SIC1 levels were much lower, and when G1- and S-phase extracts were mixed, we saw a shift in inhibitor mobility consistent with a rapid phosphorylation of the already modified polypeptide. This further modification was probably due to Clb-Cdc28, for the shift of recombinant p40SIC1-Myc-His6 occurred in S-phase extracts from wild-type and cdc7-1 cells but not from cdc28-4 cells (Fig. 6D).

The efficient replication that we detected in a mixture of G1- and S-phase extracts could be accounted for by at least two models. Either the level of Cdk1 kinase in the S-phase extract simply overwhelms the inhibitor present in the G1-phase extract and the shift in the mobility of the inhibitor is irrelevant, or else the phosphorylation of the form of p40SIC1 present in the cdc4-1 extract by S-phase kinases renders it unable to efficiently repress the kinases in the mixture. It has been shown that Clb5-Cdc28 kinase can substitute for Cln/Cdc28 kinase to modify p40SIC1 for ubiquitination and degradation (26). Since our system lacks ubiquitin, we did not observe the proteasome-dependent degradation of endogenous p40SIC1, although we did observe a rapid shift upward in the migration of p40SIC1 when it was exposed to S-phase kinases (Fig. 6). There are nine potential Cdc28 kinase target sites in p40SIC1; three of these are sufficient to mediate protein degradation (67). The possibility that the combined phosphorylation of p40SIC by Cln/Cdc28, Pcl/Pho85, and Clb-Cdc28 activities in the absence of ubiquitin inactivates the inhibitor has not been ruled out. However, when phosphorylated by Clb-Cdc28 alone, p40SIC1 appears to stay bound to the kinase complex (26). Our second explanation, i.e., that p40SIC1 is partially inactivated by cumulative phosphorylation, required verification by further in vitro studies. It is partially inconsistent with the simpler model, which proposes that the Cln/Cdc28 and Clb5-Cdc28 modifications of p40SIC1 are equivalent and serve only to target p40SIC1 for ubiquitination (14, 26). In our experiments, it is clear that the persistence of a faster-migrating form of p40SIC1 in the cdc4-1 G1-phase extract correlated with a lack of replication in vitro and that this inhibition could be at least partially overcome by the addition of the p40SIC1-insensitive Xenopus CycB-Cdc2 kinase.

Potential targets of Cdk1.

The target(s) responsible for the observed Cdk-dependent regulation of replication is likely to be a component(s) of the replication machinery. One candidate is the B subunit of pol α-primase (p86), which may be the regulatory subunit of the complex (11, 13, 28, 56). The population of p86 that is newly synthesized at G1/S, becomes modified in late S phase, while the “maternal” p86 is phosphorylated in early S phase. Both populations are dephosphorylated as cells exit mitosis. Intriguingly, it was recently reported that the phosphorylation of yeast p86 is dependent on the CDC28 gene product (13, 27), much like the Cdk-dependent phosphorylation of p68, the mammalian equivalent of p86. Phosphopeptide maps of p68 from cells blocked at G1/S or in late S are similar to those produced by CycE-Cdk2 or CycA-Cdk2 phosphorylation in vitro (67a). In vitro analyses of the effects of pol α-primase phosphorylation on SV40 replication have indicated that modification by CycE-Cdk2 stimulates the primase activity of the complex, whereas modification of additional sites by CycA-Cdk2 inhibits pol α activity (67a, 68). Our observation that low levels of exogenously added Clb-Cdk1 kinase activates replication, while higher levels can repress it, is interesting in light of these studies on mammalian pol α. Low levels of Clb-Cdk1 kinase activity in early S phase may release pol α-primase from the potentially inhibitory p86 subunit, while high levels may interfere with the binding of the complex to chromatin (13). Alternatively, Clb-Cdk1 kinase may promote the association of Cdc45p and pol α (44, 69). If Cdc45p is capable of associating with DNA in the absence of a pre-RC, this Cdc45p–pol-α-primase interaction could account for the increased replication that we observed in our in vitro system upon the addition of Clb-Cdk1. The soluble replication system described here is an excellent tool for testing these hypotheses.

The single-strand-binding protein RPA also shows various degrees of phosphorylation through the cell cycle (18) which appear to be mediated by a Cdc2-type kinase (24). In yeast, the p32 subunit is phosphorylated at the G1/S boundary and dephosphorylated at the G2/M boundary (18), although the physiological relevance of these modifications is unknown.