Abstract

The application of traditional morphological and ecological species concepts to closely related, asexual fungal taxa is challenging due to the lack of distinctive morphological characters and frequent cosmopolitan and plurivorous behaviour. As a result, multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) has become a powerful and widely used tool to recognise and delimit independent evolutionary lineages (IEL) in fungi. However, MLSA can mask discordances in individual gene trees and lead to misinterpretation of speciation events. This phenomenon has been extensively documented in Diaporthe, and species identifications in this genus remains an ongoing challenge. However, the accurate delimitation of Diaporthe species is critical as the genus encompasses several cosmopolitan pathogens that cause serious diseases on many economically important plant hosts. In this regard, following a survey of palm leaf spotting fungi in Lisbon, Portugal, Diaporthe species occurring on Arecaceae hosts were used as a case study to implement an integrative taxonomic approach for a reliable species identification in the genus. Molecular analyses based on the genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition (GCPSR) and DNA-based species delimitation methods revealed that speciation events in the genus have been highly overestimated. Most IEL identified by the GCPSR were also recognised by Poisson tree processes (PTP) coalescent-based methods, which indicated that phylogenetic lineages in Diaporthe are likely influenced by incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) and reticulation events. Furthermore, the recognition of genetic recombination signals and the evaluation of genetic variability based on sequence polymorphisms reinforced these hypotheses. New clues towards the intraspecific variation in the common loci used for phylogenetic inference of Diaporthe species are discussed. These results demonstrate that intraspecific variability has often been used as an indicator to introduce new species in Diaporthe, which has led to a proliferation of species names in the genus. Based on these data, 53 species are reduced to synonymy with 18 existing Diaporthe species, and a new species, D. pygmaeae, is introduced. Thirteen new plant host-fungus associations are reported, all of which represent new host family records for Arecaceae. This study has recognised and resolved a total of 14 valid Diaporthe species associated with Arecaceae hosts worldwide, some of which are associated with disease symptoms. This illustrates the need for more systematic research to examine the complex of Diaporthe taxa associated with palms and determine their potential pathogenicity. By implementing a more rational framework for future studies on species delimitation in Diaporthe, this study provides a solid foundation to stabilise the taxonomy of species in the genus. Guidelines for species recognition, definition and identification in Diaporthe are included.

Taxonomic novelties: New species: Diaporthe pygmaeae D.S. Pereira & A.J.L. Phillips. New synonyms: Diaporthe afzeliae Monkai & Lumyong, Diaporthe alangii C.M. Tian & Q. Yang, Diaporthe araliae-chinensis S.Y. Wang et al., Diaporthe australiana R.G. Shivas et al., Diaporthe australpacifica Y.P. Tan & R.G. Shivas, Diaporthe bombacis Monkai & Lumyong, Diaporthe caryae C.M. Tian & Q. Yang, Diaporthe chimonanthi (C.Q. Chang et al.) Y.H. Gao & L. Cai, Diaporthe conferta H. Dong et al., Diaporthe diospyrina Y.K. Bai & X.L. Fan, Diaporthe durionigena L.D. Thao et al., Diaporthe etinsideae Y.P. Tan & R.G. Shivas, Diaporthe eucalyptorum Crous & R.G. Shivas, Diaporthe fujianensis Jayaward. et al., Diaporthe fusiformis Jayaward. et al., Diaporthe globoostiolata Monkai & Lumyong, Diaporthe hainanensis Qin Yang, Diaporthe hongkongensis R.R. Gomes et al., Diaporthe hubeiensis Dissan. et al., Diaporthe infecunda R.R. Gomes et al., Diaporthe italiana Chethana et al., Diaporthe juglandigena S.Y. Wang et al., Diaporthe lagerstroemiae (C.Q. Chang et al.) Y.H. Gao & L. Cai, Diaporthe lithocarpi (Y.H. Gao et al.) Y.H. Gao & L. Cai, Diaporthe lutescens S.T. Huang et al., Diaporthe machili S.T. Huang et al., Diaporthe megabiguttulata M. Luo et al., Diaporthe middletonii R.G. Shivas et al., Diaporthe morindae M. Luo et al., Diaporthe nannuoshanensis S.T. Huang et al., Diaporthe nigra Brahman. & K.D. Hyde, Diaporthe orixae Q.T. Lu & Zhen Zhang, Diaporthe passifloricola Crous & M.J. Wingf., Diaporthe pimpinellae Abeywickrama et al., Diaporthe pseudoinconspicua T.G.L Oliveira et al., Diaporthe pungensis S.T. Huang et al., Diaporthe rhodomyrti C.M. Tian & Qin Yang, Diaporthe rosae M.C. Samar. & K.D. Hyde, Diaporthe rumicicola Manawas et al., Diaporthe salicicola R.G. Shivas et al., Diaporthe samaneae Monkai & Lumyong, Diaporthe subcylindrospora S.K. Huang et al., Diaporthe tectonae Doilom et al., Diaporthe tectonigena Doilom et al., Diaporthe theobromatis H. Dong et al., Diaporthe thunbergiicola Udayanga & K.D. Hyde, Diaporthe tuyouyouiae Y.P. Tan et al., Diaporthe unshiuensis F. Huang et al., Diaporthe vochysiae S.A. Noriler et al., Diaporthe xishuangbannaensis Hongsanan & K.D. Hyde, Diaporthe xylocarpi M.S. Calabon & E.B.G. Jones, Diaporthe zaobaisu Y.S. Guo & G.P. Wang, Diaporthe zhaoqingensis M. Luo et al.

Citation: Pereira DS, Phillips AJL (2024). Diaporthe species on palms – integrative taxonomic approach for species boundaries delimitation in the genus Diaporthe, with the description of D. pygmaeae sp. nov. Studies in Mycology 109: 487–594. doi: 10.3114/sim.2024.109.08

Keywords: coalescent-based methods, genetic distance-based methods, integrative taxonomy, new taxa, species limits

INTRODUCTION

Species are the fundamental units of biodiversity, ecology, evolution, and bioconservation. Yet, defining and recognising a species has been an ongoing challenge (De Queiroz 2007, Ellis 2011). Many species concepts and recognition criteria have been proposed over the years. However, whether it is based on morphological, biological, ecological or phylogenetic characters, there are numerous disagreements regarding the acceptable criteria to delineate a fungal species (Giraud et al. 2008, Lücking et al. 2020, Xu 2020, Stengel et al. 2022). The high degree of phenotypic plasticity, homologous sequence data and broad range of hosts, often lead to different conclusions about how to determine the variation and boundaries between fungal taxa (Jeewon & Hyde 2016, Steenkamp et al. 2018, Chethana et al. 2020, 2021a).

Since the early 1990s, the use of DNA sequence analyses increased the complexity of fungal taxonomy, giving rise to new difficulties in understanding evolutionary processes and relationships. Although phylogenetic-based studies have changed the perception of fungal diversity, relationships at species level and recognition of species remain controversial and subject to different interpretations (Hyde et al. 2013, Jeewon & Hyde 2016, Xu 2016, 2020, Maharachchikumbura et al. 2021). The concatenation of multilocus DNA sequence data represents a powerful and commonly used approach to recognise independent evolutionary lineages (IEL) in fungi (Dupuis et al. 2012). However, the process is not always straightforward as it can mask the discordances among loci and lead to misinterpretations of the speciation events (Kubatko & Degnan 2007).

The genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition (GCPSR) (Taylor et al. 2000), which relies on the comparison of more than one gene genealogy, has proven to be a suitable tool for species delimitation, especially in morphologically conserved fungi (Cai et al. 2011, Laurence et al. 2014, Udayanga et al. 2014a). According to the GCPSR, recombination within a lineage is likely to cause conflict between gene trees and the transition from conflict to congruence indicates the species limit (Taylor et al. 2000). Even so, genes can have significantly different evolutionary histories, which make the species boundaries difficult to ascertain in the early stages of speciation. Thus, processes such as incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) and other reticulation events can also cause gene-tree/species-tree discordance and ultimately mislead the evolutionary relationships among closely related taxa (Castresana 2007, Degnan & Rosenberg 2006, 2009, Schrempf & Szöllősi 2020).

For the above reasons, modern systematics rely on integrative taxonomic approaches that combine different sources of evidence for identifying, delimiting, and describing species. Subsequently, congruence between results from different methods and datasets is likely to lead to more reliably supported species limits (Padial et al. 2010, Carstens et al. 2013, Bustamante et al. 2019, Stengel et al. 2022). Recent studies have successfully applied coalescentand genetic distance-based methods to aid species delimitation in taxa where cryptic speciation processes have been reported. Coalescent-based methods, which stochastically connect sampled gene lineages backward in time, allow alternative hypotheses of evolutionary independence to be tested. These methods can infer the relationships among taxa and delimit IEL objectively even when there is incongruence between gene genealogies and lack of reciprocal monophyly among lineages. Thus, coalescent-based methods provide a more comprehensive view of speciation events than the GCPSR (Rannala & Yang 2003, 2020, Liu et al. 2009, Sukumaran & Knowles 2017). On the other hand, genetic distance-based methods rely on the close clustering of haplotypes as an indication of the species boundaries, which will therefore depend on the difference in variation of intra- and interspecific diversification rates. These methods can infer putative relationships among taxa by accessing pairwise nucleotide genetic distances in the sequences of a given dataset. These are grouped according to the assumption that the genetic variation within species is smaller than between species (DeSalle et al. 2005, Del-Prado et al. 2010, Zou et al. 2011, Krishnamurthy & Francis 2012).

Coalescent- and genetic distance-based methods have proved to be very useful to estimate species trees and support species boundaries for several animal (e.g., Waters et al. 2010, Satler et al. 2013, Yu et al. 2017, Guo & Kong 2022) and plant (e.g., Carston et al. 2009, Karbstein et al. 2020, Vieira et al. 2023) taxa. However, they have rarely been used in fungi. A few studies have examined the utility of these methods for closely related, morphologically conserved asexual fungal taxa, such as Alternaria (Stewart et al. 2014), Aspergillus (Sklenář et al. 2017, 2021), Beauveria (Bustamante et al. 2019), Colletotrichum (Liu et al. 2016), Fusarium (Achari et al. 2020) and, more recently, Diaporthe (Hilário et al. 2021a, b, Pereira et al. 2023).

Species of Diaporthe (syn. Phomopsis) have a diverse host range and a wide geographical distribution, occurring mostly as plant pathogens, endophytes and saprobes, but also as pathogens of humans and other mammals (Murali et al. 2006, Garcia-Reyne et al. 2011, Udayanga et al. 2011, Marin-Felix et al. 2019). Species recognition criteria in Diaporthe have evolved from morphology and host association (Uecker 1988) to the widespread use of DNA sequence data (Udayanga et al. 2012a, b, Tan et al. 2013, Dissanayake et al. 2017, Lambert et al. 2023). Modern systematic accounts of the genus rely on multilocus sequence analyses (MLSA) based on the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, and the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1), beta-tubulin (tub2), histone (his3), and calmodulin (cal) loci (Gomes et al. 2013, Santos et al. 2017a, Guo et al. 2020, Sun et al. 2021, Wang et al. 2021). Although Diaporthe has received much attention, and many phylogenetic studies have been conducted over the years, the taxonomy of the genus is still uncertain, and several lineages remain poorly understood. Cryptic diversification, phenotypic plasticity and extensive host associations, coupled with its paraphyletic nature, have long made it difficult to accurately identify Diaporthe spp. and ultimately impair a truthful analysis of their species boundaries (Gao et al. 2017, Norphanphoun et al. 2022).

In recent years, most studies have considered distinct well-supported Diaporthe clades recognised by MLSA as distinct species, disregarding key factors to determine species status, such as incongruences among gene genealogies and lack of gene flow between populations. However, gene concatenation has been shown to impair reliable tree topologies when there are high levels of ILS, recombination or other reticulation events, resulting in poor species discrimination (Kubatko & Degnan 2007, Mendes & Hahn 2018). Therefore, Diaporthe is an ideal case study for the application of quantitative species recognition methodologies, using methods that incorporate uncertainty in gene trees, and that assess intra- and interspecific diversification rates. Recent studies have shown significant incongruences among the gene genealogies and identified the presence of recombination events, indicating divergent evolutionary histories among the common loci used for phylogenetic inference in Diaporthe (Hilário et al. 2021a, b, Pereira et al. 2023). Hilário et al. (2021a, b) resolved the D. amygdali and D. eres species complexes through the application of the GCPSR principle, along with coalescent-based models, providing evidence that each complex constitutes a population with intraspecific variability rather than different lineages. Pereira et al. (2023) recognised three IEL in the D. arecae species complex (DASC) and reduced 52 species to synonym under D. arecae following an integrative taxonomic approach that included genealogical concordance and coalescent-based analyses. Hypotheses suggested by the authors to explain these results included recombination and ILS. Despite having been reported in previous studies, these phylogenetic incongruences are still overlooked in most Diaporthe spp.

Considering that the high intraspecific variability of Diaporthe has been erroneously used to delimit species, the true species diversity of the genus is likely to be highly overestimated. In this sense, in the present study, Diaporthe species occurring on Arecaceae hosts were used as a case study to gain new insights into the phylogenetic species delimitation in the genus. No intensive study supported by molecular data has yet been carried out to resolve the complex of Diaporthe species occurring on Arecaceae hosts. Although several Diaporthe species have been recorded on palms, most were mainly based on host association but without molecular data to confirm their phylogenetic position. As a result, most of these taxa have not been transferred to Diaporthe and remain in Phomopsis. Fröhlich et al. (1997) provided a synopsis of Diaporthe (as Phomopsis) species known from palms and several other species have been reported by Taylor & Hyde (2003).

Recently, Pereira et al. (2023) resolved the species boundaries delimitation in the DASC and provided new data on the Diaporthe species occurring on palms. The present study builds on this previous research and aims to: (1) implement an integrative taxonomic approach, comprising single and multilocus phylogenetic analyses, coalescent- and genetic distance-based species delimitation methods, phylogenetic networks and hierarchical cluster analysis of phenotypic data, to reliably identify species in the genus Diaporthe; (2) propose practical guidelines to provide a more rational framework, based on scientific data, on how to delineate species boundaries and establish novel taxa in the genus Diaporthe; (3) identify a set of potential phytopathogenic isolates of Diaporthe obtained from foliar lesions of ornamental palm trees in Lisbon, Portugal; and (4) resolve the complex of Diaporthe species occurring on Arecaceae hosts. A new synopsis of currently accepted and phylogenetically validated Diaporthe species reported from palms worldwide is also presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen collection, examination, and single-spore isolation

Between October 2018 and May 2021, diseased leaf segments and leaflets with foliar lesions were collected from different ornamental palm tree species in Lisbon, Portugal, including Chamaerops humilis, Chrysalidocarpus lutescens, Phoenix roebelenii, Trachycarpus fortunei, and Washingtonia filifera (detailed information of collection sites and respective hosts are referred to in the Taxonomy section). Plant material was transported to the laboratory in paper envelopes and examined with a Leica MZ9.5 stereo microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Germany) for observations on lesion morphology and associated fungi.

Isolations were made directly from foliar lesions. Pieces of tissue 1–2 mm2 were cut from the edge of the lesion, surface disinfected in 5 % sodium hypochlorite for 1 min, rinsed in three changes of sterile water and blotted dry on sterile filter paper. The fragments were plated onto 1/2 strength Potato Dextrose Agar (1/2 PDA) (PDA; BIOKAR Diagnostics, France) containing 0.05 % chloramphenicol (CPDA) (Chloramphenicol; Sigma-Aldrich, Canada) and incubated at room temperature until colonies developed. Colonies were subcultured onto 1/2 PDA, and single-spore isolates were subsequently established. Sterilisation efficiency was controlled by sterilised leaf fragments impressions and plating of the last sterile water change onto CPDA.

Four of the isolates used in the present study, i.e., CDP 0022, CDP 0209, CDP 0315 (D. foeniculina) and CDP 0052 (D. pyracanthae), were previously reported as a preliminary study on Diaporthe occurring on palms published in Boonmee et al. (2021) and their morphomolecular characterisation was re-accessed here.

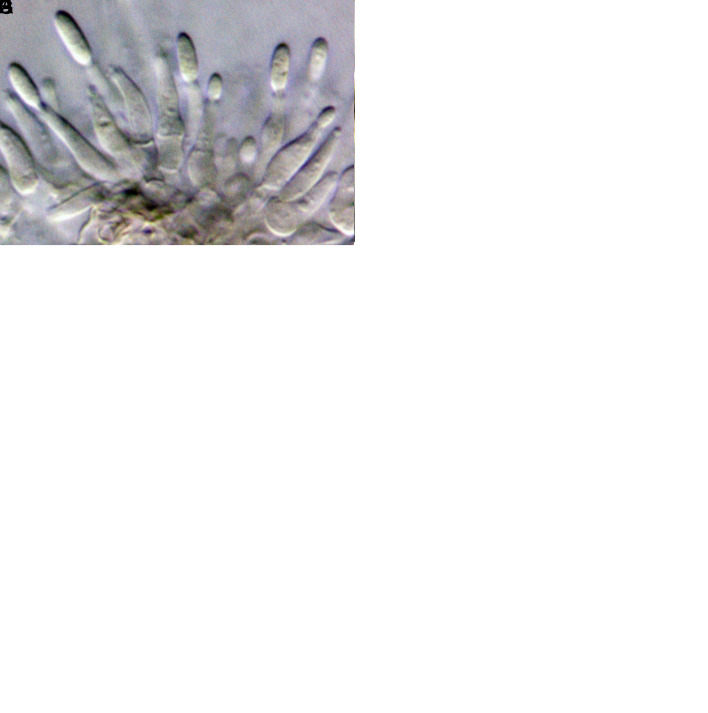

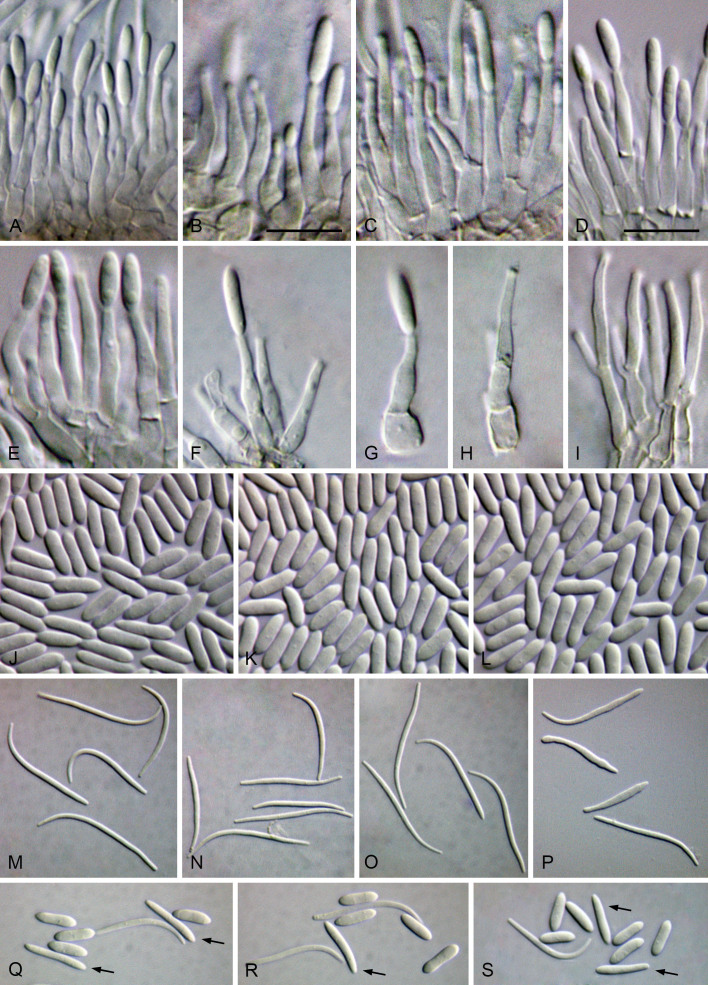

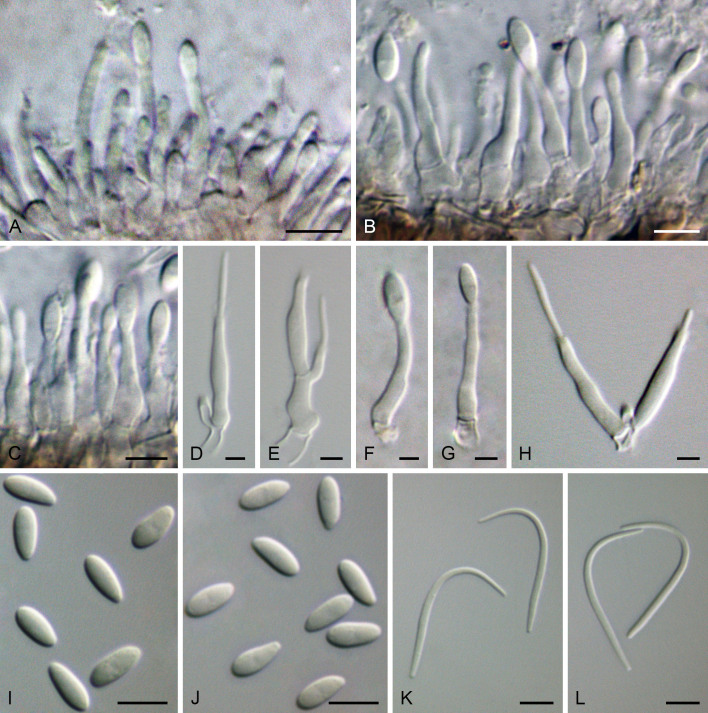

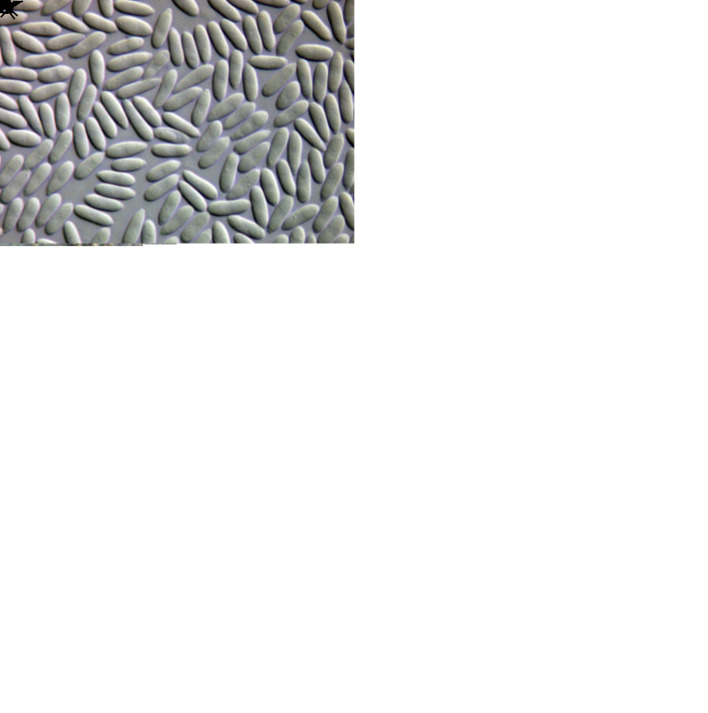

Morphological observation and characterisation

Cultures were induced to sporulate by culturing on 2 % water agar (WA) (Bacteriological Agar Type E; BIOKAR Diagnostics, France) bearing healthy doubled autoclaved (two cycles of 20 min, 121 °C and 1 bar with 48 h between each cycle) palm leaf pieces. After a suitable period of incubation at 28 °C under black light, ranging from 3 d to 1 wk, conidiomata were cut through vertically and the conidiogenous layer dissected. Microscopic structures (pycnidia, conidiophores, conidiogenous cells and conidia) were mounted in 100 % lactic acid and examined by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. Observations on micromorphological features were made with Leica MZ9.5 and Leica DMR microscopes (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Germany), and digital images were recorded with Leica DFC300 and Leica DFC320 cameras (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Germany), respectively. Measurements were made with the measurement module of the Leica IM500 Image Management System (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Germany). Mean, standard deviation (SD) and 95 % confidence intervals were calculated from n = total of measured structures. Measurements are given as minimum and maximum dimensions with mean and SD in parenthesis. Photoplates were prepared with Adobe Photoshop CS6 Extended (Adobe, USA).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from mycelium of cultures grown on 1/2 PDA following a modified and optimized version of the guanidium thiocyanate method described by Pitcher et al. (1989). Amplification reactions were carried out with Taq polymerase, nucleotides, primers, PCR-grade water (ultrapure DNase/RNase-free distilled water) and buffers supplied by Invitrogen (USA). Primer details and respective amplification targets are listed in Table 1. Amplification reactions were performed in an UNO II Thermocycler (Biometra, Germany). The PCR products were checked on 1 % agarose electrophoresis gels stained with ethidium bromide and visualised on a UV transilluminator to assess PCR amplification. Amplified PCR products were purified and sequenced by Eurofins Genomics (Germany).

Table 1.

Details of primers used for amplification and sequencing.

| Locus1 | Primer name | Direction | Sequence (5’ → 3’) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cal | CAL-228F | Forward | GAGTTCAAGGAGGCCTTCTCCC | Carbone & Kohn (1999) |

| CAL-737R | Reverse | CATCTTTCTGGCCATCATGG | Carbone & Kohn (1999) | |

| ITS | ITS5 | Forward | GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG | White et al. (1990) |

| NL4 | Reverse | GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG | O’Donnell (1993) | |

| tef1 | EF1-688F | Forward | CGGTCACTTGATCTACAAGTGC | Alves et al. (2008) |

| EF1-1251R | Reverse | CCTCGAACTCACCAGTACCG | Alves et al. (2008) | |

| tub2 | T1 | Forward | AACATGCGTGAGATTGTAAGT | O’Donnell & Cigelnik (1997) |

| Bt2b | Reverse | ACCCTCAGTGTAGTGACCCTTGGC | Glass & Donaldson (1995) |

1cal: partial calmodulin gene; ITS: partial cluster of nrRNA genes, including the nuclear 5.8S rRNA gene and its flanking internal transcribed spacer regions ITS1 and ITS2; tef1: partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene; tub2: partial beta-tubulin gene.

The PCR reaction mixtures and respective cycling conditions used to amplify the cluster of nrRNA genes (ITS) and part of the translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene (tef1) and the β-tubulin gene (tub2), were performed as described by Pereira & Phillips (2023). Primers CAL-228F and CAL-737R were used to amplify part of the calmodulin gene (cal). The PCR reaction mixture for each primer pair consisted of 50–100 ng of gDNA, 1× PCR buffer, 25 pmol of each primer, 200 μM of each dNTP, 3 mM MgCl2, 3 % of DMSO, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase and was made up to a total volume of 25 μL with PCR-water. Negative controls with PCR water instead of the template DNA were included in every set of amplification reactions. The following cycling conditions were used: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 45 s and elongation at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 min.

ITS and tef1 were sequenced only in the forward direction using the primers ITS5 and EF1-688F, respectively, while tub2 and cal were sequenced in both directions using the same primers as used for the DNA amplification. Consensus sequences for tub2 and cal were produced using BioEdit v. 7.0.5.3 (Hall 1999). All newly generated sequences were deposited in GenBank and their accession numbers are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Collection details and GenBank accession numbers of taxa included in the phylogenetic analyses.

1 Taxon or strain previous name is noted in brackets if different from current name for taxa that have been synonymised (indicated by syn.) or resolved in the present study or in previous studies.

2 Acronyms of culture collections, AR, FAU: isolates in culture collection of Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, Maryland, USA; ATCC: American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, USA; BRIP: Plant Pathology Herbarium, Department of Primary Industries, Dutton Park, Queensland, Australia; CAA: Collection of Artur Alves housed at Department of Biology, University of Aveiro, Portugal; CBS: CBS-KNAW Fungal Bio-diversity Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CDP: culture collection of D.S. Pereira, housed at the Lab Bugworkers | M&B-BioISI | Tec Labs – Innovation Centre, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal; CECT: Spanish Type Culture Collection at University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain; CFCC: China Forestry Culture Collection Center, Beijing, China; CGMCC: China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center, China; CGMHD: Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan; CPC: working collection of P.W. Crous, housed at CBS; DAL: strains deposited in fungal collection of the Instituto Agroforestal Mediterráneo, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain; GUCC: Guizhou University Culture Collection; GZCC: Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences Culture Collection, Guizhou, China; JZB: culture collection of Institute of Plant and Environmental Protection, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing 100097, China; KUMCC: Culture Collection of Kunming Institute of Botany, Kunming, China; KUNCC: Kunming Institute of Botany Culture Collection, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, China; LC: working collection of Lei Cai, housed at Laboratory State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China; LGMF: Culture Collection of Laboratório de Genética de Microrganismos (LabGeM), Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil; MFLU: Herbarium of Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, Thailand; MFLUCC: Mae Fah Luang University Culture Collection, Chiang Rai, Thailand; MUM: Culture Collection of Micoteca da Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal; NCYUCC: National Chiayi University Culture Collection, Taiwan; NTUCC: Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, National Taiwan University Culture Collection, Taiwan; NTUPPMCC: Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, National Taiwan University Culture Collection; PSCG: personal culture collection of Y.S. Guo, China; SAUCC: Shandong Agricultural University Culture Collection, China; SCHM: Mycological Herbarium of South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China; SDBR-CMU: Culture Collection of Sustainable Development of Biological Resources Laboratory at Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand; STMA: culture collection of HZI, Helmholtz Center for Infection Research, Braunschweig, Germany; URM: Culture Collection of Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil; VPRI: Victorian Plant Pathology Herbarium, National Collection of Fungi, Knoxfield, Victoria, Australia; VTCC: Vietnam Type Culture Collection, Center of Biotechnology, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam; ZHKUCC: University of Agriculture and Engineering Culture Collection, China.

3 Status of the strains or specimens are noted by bold superscript ET (ex-epitype), H (holotype), IT (ex-isotype), PT (ex-paratype) and T (ex-type).

4 Newly generated sequences are in bold; n/a: sequences not available; cal: partial calmodulin gene; his3: partial histone H3 gene; ITS: partial cluster of nrRNA genes, including the nuclear 5.8S rRNA gene and its flanking internal transcribed spacer regions ITS1 and ITS2; tef1: partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene; tub2: partial beta-tubulin gene.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

A preliminary identification based on BLASTn searches with the ITS sequences of the isolates from the present study was carried out to determine the most closely related taxa, whose sequences were subsequently retrieved from GenBank. Isolates of Diaporthe obtained from palm tissues listed in recent literature (i.e., Gomes et al. 2013, Azuddin et al. 2021, Sun et al. 2021) or deposited in GenBank were also used. An initial phylogenetic analysis with all species currently accepted in the genus Diaporthe was conducted. The resulting tree was compared with recent literature on Diaporthe. Nine well-supported clades containing the Diaporthe isolates from palms examined in the present study were selected for further analyses. These clades were populated and the available ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequences for the corresponding taxa were retrieved from GenBank and their accession numbers are listed in Table 2.

Sequences for each locus were aligned with ClustalX v. 2.1 (Thompson et al. 1997) using the following parameters: pairwise alignment parameters (gap opening = 10, gap extension = 0.1) and multiple alignment parameters (gap opening = 10, gap extension = 0.2, DNA transition weight = 0.5, delay divergent sequences = 25 %). Alignments were checked, and manual adjustments were made wherever necessary with BioEdit v. 7.0.5.3 (Hall 1999). Terminal regions with missing data and ambiguously aligned regions were visually checked and manually excluded from the analysis. Sequences were combined in concatenated matrices using MEGA X v. 10.2.6 (Kumar et al. 2018).

Maximum likelihood (ML), maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian analyses (BA) were used for phylogenetic inferences of the concatenated alignments and were implemented on the CIPRES Science Gateway portal v. 3.3 (Miller et al. 2010) using RAxML-NG v. 1.1.0 (Kozlov et al. 2019), PAUP v. 4.0a165 (Swofford 2002) and MrBayes v. 3.2.7a (Ronquist et al. 2012), respectively. The resulting trees were visualised with FigTree v. 1.4.4 (Rambaut 2018) and prepared with Adobe Illustrator CS2 v. 12.0.0 (Adobe, USA). All phylogenetic inferences included a set of outgroup taxa corresponding to Diaporthe species closely related to the Diaporthe clade under analysis as inferred by the initial phylogenetic analysis conducted.

The best-fit nucleotide substitution model for each locus was determined using MEGA X v. 10.2.6 (Kumar et al. 2018) under the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Clade stability and robustness of the branches of the best scoring ML tree were estimated by conducting a rapid bootstrap (BS) analysis with iterations halted automatically by RAxML-NG.

Maximum parsimony analyses were performed using the heuristic search option with 1 000 random taxa additions and tree bisection and reconnection (TBR) as the branch-swapping algorithm. All characters were unordered and of equal weight, and alignment gaps were treated as missing data. Maxtrees was set to 10 000, branches of zero length were collapsed and all multiple, and equally parsimonious trees were saved. The first equally most parsimonious tree was used as reference when multiple equally most parsimonious trees were obtained. Clade stability and robustness of the most parsimonious trees were assessed using BS analysis with 1 000 pseudoreplicates, each with 10 replicates of random stepwise addition of taxa (Felsenstein 1985, Hillis & Bull 1993). Descriptive tree statistics for parsimony such as tree length (TL), homoplasy index (HI), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI) and rescaled consistency index (RC) were calculated.

The Bayesian analyses were computed with four simultaneous Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains for two runs, 10 000 000 generations and a sampling frequency of 10 generations, ending the run automatically when standard deviation of split frequencies (SDSF) fell below 0.01. The first 25 % of trees were discarded as the burn-in fraction, while the remaining 75 % were used to calculate the 50 % majority rule consensus tree and posterior probability (PP) values.

The resulting alignments and phylogenetic trees were deposited in figshare (www.figshare.com, DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.27144723, accessed during October 2024).

Phylogenetic species recognition

Individual gene trees were assessed to compare highly supported clades in order to detect clade conflicts between the individual phylogenies and to accordingly apply the GCPSR principle (Taylor et al. 2000) to determine the species boundaries of each Diaporthe clade. Subclades were ranked to independent evolutionary lineages (IEL) if they were a) well-delimited from other lineages as dichotomous branches with relevant relative length; and b) well-supported (ML-BS and MP-BS ≥ 70 %) in a single gene tree and not contradicted at or above this level of support in more than one other single gene tree. For these assessments, ML and MP analyses were conducted as described above for single gene sequence alignments. Species with missing data for a given gene were excluded from the analyses of that gene region. The IEL were determined conclusively if resolved with high support values (ML/MP-BS ≥ 70 % and PP ≥ 0.90) in most phylogenetic analyses of the combined datasets. For all potential synonyms and new species, their phylogenetic position, branch length to the closest sister species and support values for the clustering were evaluated.

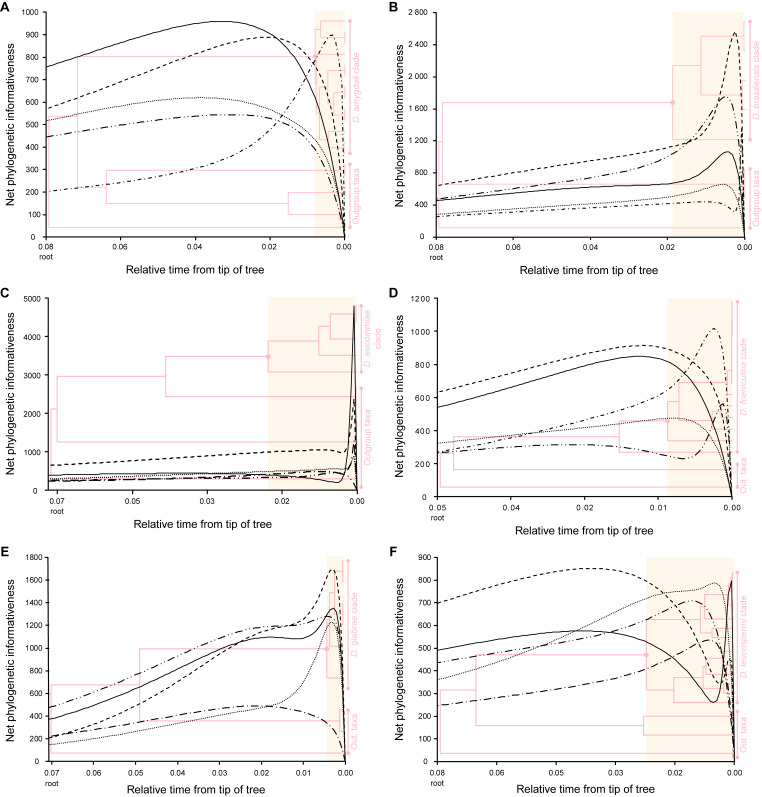

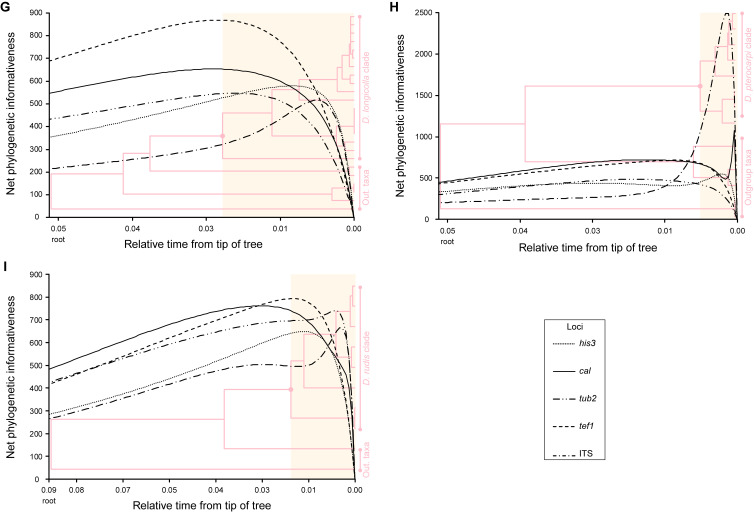

Phylogenetic informativeness analysis

To determine the loci most suitable for phylogenetic inference in each Diaporthe clade, the phylogenetic informativeness (PI) profiling method (Townsend 2007) was employed. The analysis was implemented in PhyDesign (López-Giráldez & Townsend 2011) web server (http://phydesign.townsend.yale.edu/, accessed during November 2023). The PI was measured from a partitioned combined dataset of the ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 loci for the strains of each Diaporthe clade for which the five loci were available, including the set of closely related outgroup taxa. An ML inference from RAxML-NG analysis of the combined dataset was performed as described above, using a general time reversible (GTR) nucleotide substitution model including a discrete gamma distribution and estimation of proportion of invariable sites (GTR + G + I) to accommodate variable rates across sites. The ML inference was used to build a time tree using MEGA X v. 10.2.6 (Kumar et al. 2018) as described by Mello (2018). Relative divergence times were estimated for all branching points by applying the RelTime-ML method (Tamura et al. 2012, 2018) with no calibration constraints. Branch lengths were calculated using the same substitution model as previously used to estimate the ML inference. The PI for all five partitions were determined using the rates of change for each site under the HyPhy criteria (Pond et al. 2005).

Species delimitation analyses

Five DNA-based species delimitation analyses were carried out, including three genetic distance-based methods, i.e., statistical parsimony network (SPN) (Templeton et al. 1992), automatic barcode gap discovery (ABGD) (Puillandre et al. 2012) and assemble species by automatic partitioning (ASAP) (Puillandre et al. 2021), and two coalescent-based methods, i.e., Poisson tree processes (PTP) (Zhang et al. 2013) and multi-rate PTP (mPTP) (Kapli et al. 2017). For these assessments, single gene sequence alignments for the most phylogenetic informative locus (as determined by the PI profiling method) for ABGD and ASAP, and 5-loci combined datasets for all methods, were used to infer the species boundaries of each Diaporthe clade.

The species delimitation hypotheses inferred by each method were compared with the phylogenetic species recognised by the GCPSR principle. Subsequently, the taxa delimited by the DNA-based species delimitation analyses were considered as molecular operational taxonomic units (MOTU) and were used to calculate the delimitation efficiency ratio (DER) according to equation (1) to assess which method best infers the species limits recognised by the GCPSR principle. The delimitation of the closely related outgroup taxa included in each clade was not considered for the DER as the analyses conducted were not directed towards the delimitation of these species.

| (1) |

where, for a given Diaporthe clade, NMOTU stands for the number of MOTU inferred by a given species delimitation method, and Nspecies stands for the number of species recognised by the GCPSR principle.

The SPN analyses were performed in TCS v. 1.21 (Clement et al. 2000) with alignment gaps treated as missing data, and a maximum parsimony connection probability set at 95 % statistical confidence, as this value proved to be a useful general tool and simple quantitative standard for phylogenetic species recognition (Hart & Sunday 2007). Resulting networks were considered as MOTU.

The ABGD analyses were performed using the Kimura two-parameter (K2P) nucleotide substitution model (Kimura 1980) to compute the matrix of pairwise nucleotide distances; the remaining parameters were left as default, including a relative gap width (X) of 1.5, and a prior maximum divergence of intraspecific diversity (P) ranging from 0.001 (Pmin) to 0.1 (Pmax). The analyses were conducted on the web server for ABGD (https://bioinfo.mnhn.fr/abi/public/abgd/abgdweb.html, accessed during November 2023). Only the primary partitions produced by ABGD were considered to sort the aligned sequences into hypothetical species, since they are typically stable on a wider range of prior values and are usually closer to the number of groups described by taxonomists (Puillandre et al. 2012). However, recursive splits were checked and are reported if their results were considered significant given the species delimitation schemes produced by the other methods. Moreover, to avoid subjectivity in the analyses, the median number of ABGD partitions (i.e., closest to P = 0.01) were used as the basis for hypothetical species, as this has produced good correspondence with traditional species in empirical studies (Puillandre et al. 2012, Kekkonen & Herbert 2014).

The ASAP analyses were performed using the K2P nucleotide substitution model (Kimura 1980) to compute the matrix of pairwise nucleotide distances; the remaining parameters were left as default, including a recursive split probability of 0.01. The analyses were conducted on the web server for ASAP (https://bioinfo.mnhn.fr/abi/public/asap/, accessed during November 2023). Hypothetical species delimitation was defined evaluating both the partitions with best asap-score and with second best asap-score according to Puillandre et al. (2021). In highly discordant cases, the partition with the third best asap-score was also evaluated. The partition selected was the closest to the delimitation predicted based on phylogenetic analyses, as well as the species delimitation schemes produced by the other methods.

The PTP (Zhang et al. 2013) and mPTP (Kapli et al. 2017) analyses were performed using the ML inferences produced by RAxML-NG v. 1.1.0 (Kozlov et al. 2019). The PTP analyses were performed with 500 000 MCMC generations, thinning set to 100, burn-in of 10 % and conducted on the web server for PTP (http://species.h-its.org/ptp/, accessed during November 2023). Convergence of the MCMC iterations was assessed by visualising the log-likelihood trace plot. The mPTP analyses were conducted on the web server for mPTP (http://mptp.h-its.org, accessed during November 2023). The resulting trees were prepared with Adobe Illustrator CS2 v. 12.0.0 (Adobe, USA).

Coalescent-based species tree estimation methods have been shown to work reliably and produce accurate species trees even when there are substantial amounts of missing data (Nute et al. 2018), especially if they are randomly distributed (per gene and/or per taxa) and if a sufficiently large number of genes are sampled (Xi et al. 2016). To avoid possible erroneous species delimitations schemes, given the lack of cal and his3 partial sequences for several species of most Diaporthe clades under analysis, PTP and mPTP analyses were additionally applied to combined datasets that included those species whose five (ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3), four (ITS, tef1, tub2 and cal) and three (ITS, tef1 and tub2) loci were available, and were conducted using ML inferences of the 5-, 4- and 3-loci combined datasets, respectively. All coalescent-based species delimitation schemes obtained for each Diaporthe clade were qualitatively compared and discordant cases are noted and discussed. To aid conclusions on species excluded from these additional analyses due to lack of partial sequences for tef1 and/or tub2, their phylogenetic position within the established species boundaries of its respective clade was considered. A similar approach was followed for ABGD and ASAP analyses when there were a substantial number of species lacking tub2 and cal partial sequences for a given Diaporthe clade. Therefore, these analyses were conducted using 3-loci combined datasets.

Pairwise homoplasy index test and phylogenetic network analyses

The concatenated alignments were used to infer the occurrence of recombination events within each Diaporthe clade under analyses, and between potentially synonymous species within each Diaporthe clade through the pairwise homoplasy index (PHI, Φw) test (Bruen et al. 2006) implemented in SplitsTree4 v. 4.19.0 (Huson & Bryant 2006). For these assessments, when possible, the strains of a given species were tested for genetic interchange with a set of authentic strains, including those with type status, of the respective species under which the synonym is suggested. A similar approach was followed for potentially taxonomic novelties. Significant recombination was considered when the probably of the Φw-statistic was below 0.05 (P-value < 0.05).

To evaluate and visualise the impact of the potential recombination events, the relationships between taxa within each Diaporthe clade were visualised through phylogenetic networks based on the concatenated sequence alignments. The phylogenetic networks were constructed using the LogDet transformation (Steel 1994) for the distance matrix and the Neighbor-Net algorithm (Bryant & Moulton 2006) implemented in SplitsTree4 v. 4.19.0 (Huson & Bryant 2006). The resulting phylogenetic networks were prepared with Adobe Illustrator CS2 v. 12.0.0 (Adobe, USA).

Hierarchical cluster analysis of phenotypic data

To assess the correlation between species phylogenetic boundaries and taxa morphology, measurements of the length and width of morphological features of all species belonging to each Diaporthe clade with published taxonomic descriptions were used. A hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was conducted using R Statistical Software v. 4.3.1 (R Core Team 2023). Pairwise distance among taxa were estimated with Euclidean distance index to generate the dissimilarity matrices and dendrograms were constructed by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) as the clustering algorithm. Dendrograms were generated using the following R packages: cluster v. 2.1.4 (Maechler et al. 2022), factoextra v. 1.0.7 (Kassambara et al. 2020) and dendextend v. 1.17.1 (Galili 2015). The number of clusters was determined by visual inspection of the dendrograms and by using the gap statistic method (Tibshirani et al. 2001). Goodness-of-fit of the dendrograms was evaluated by means of the cophenetic correlation coefficient (c) (Sokal & Rohlf 1962). Dendrograms were generated based on the length-to-width (L/W) ratios of alpha conidia, beta conidia and/or elements of the conidiogenous layer (i.e., conidiophores and/or conidiogenous cells). The species included in the analyses were only those with available dimensions for these features. When several taxa were lacking dimensions for a particular feature, it was excluded from the analyses or, in the case of beta conidia, coded with zeros. The L/W ratios were calculated for all taxa following equation (2) to standardise and make the data comparable between taxa.

| (2) |

where, for a given taxon and a given micromorphological structure, Lmin and Lmax stand for the length minimum and maximum dimensions, respectively, and Wmin and Wmax stand for the width minimum and maximum dimensions, respectively.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analyses and phylogenetic species recognition

Twenty-six isolates obtained from foliar lesions of palms in Lisbon, Portugal were tentatively identified as diaporthe-like taxa based on macro- and micromorphological characters. These included the presence of fluffy, flattened, white or greyish aerial mycelium, often with scattered, solitary or aggregated, globose to subglobose, dark conidiomata, producing alpha and/or beta conidia. BLASTn searches in GenBank with the newly generated ITS sequences revealed about 99–100 % similarity to known Diaporthe species. Phylogenetic analyses of these isolates, along with 10 additional Diaporthe taxa isolated from palm tissues listed in recent literature or deposited in GenBank, revealed that they belong in nine well-supported (ML-BS ≥ 95 %) Diaporthe clades, which were assigned according to the oldest typified species (Figs 1–9). Fifteen isolates reside in the D. foeniculina clade (Fig. 5), five in the D. longicolla clade (Fig. 9), four in the D. leucospermi clade (Fig. 8), three in the D. amygdali clade (Fig. 2), two in each the D. brasiliensis (Fig. 3), D. glabrae (Fig. 6) and D. rudis (Fig. 10) clades, while the remaining two isolates reside in the D. eucommiae (Fig. 4) and D. inconspicua (Fig. 7) clades. All nine Diaporthe clades, along with a set of closely related outgroup taxa, were subsequently analysed to assess their species limits and correctly assign isolates from palm tissues to Diaporthe species.

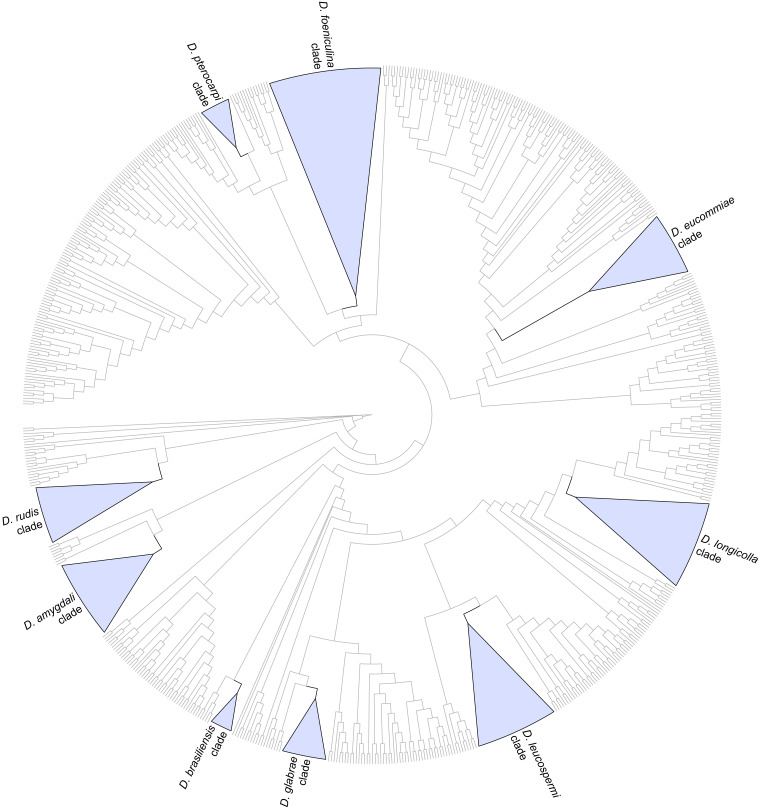

Fig. 1.

Cladogram of the phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the isolates from palms examined in this study and all species currently accepted in the genus Diaporthe. A total of 783 strains were included in the combined dataset that comprised 2 790 characters (including gaps) (576 characters for ITS, 507 for tef1, 560 for tub2, 614 for cal and 533 for his3) after alignment and manual adjustment. The analysis was conducted using the GTR+G+I nucleotide substitution model. Taxa names and phylogenetic support values have been removed for simplification purposes. The well-supported (ML-BS ≥ 95 %) clades containing the isolates from palms examined in this study have been collapsed and are highlighted with coloured triangles with their respective branches in black. Cladogram is rooted to Cytospora disciformis (CBS 116827 and CBS 118083).

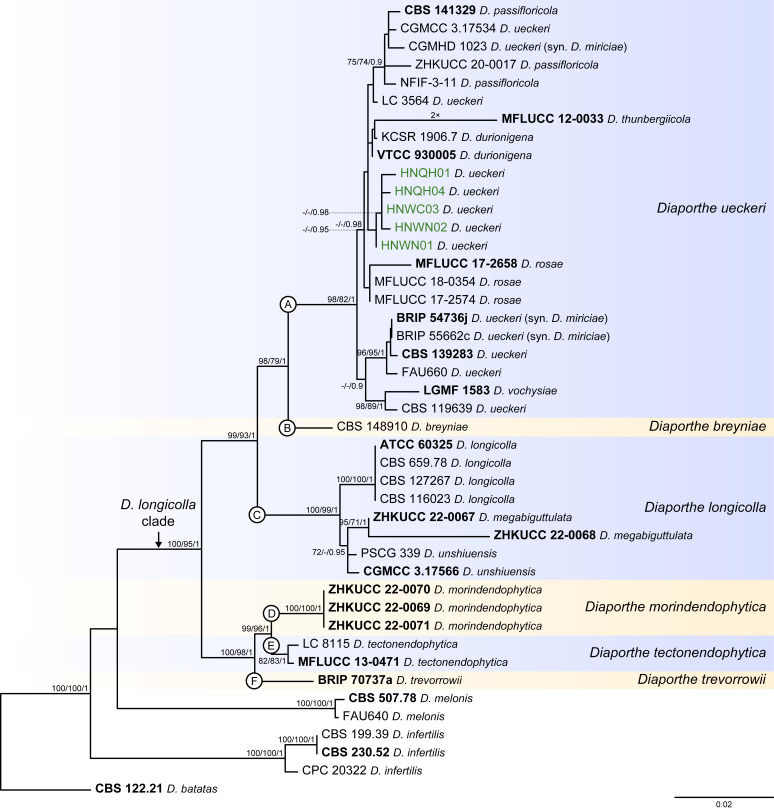

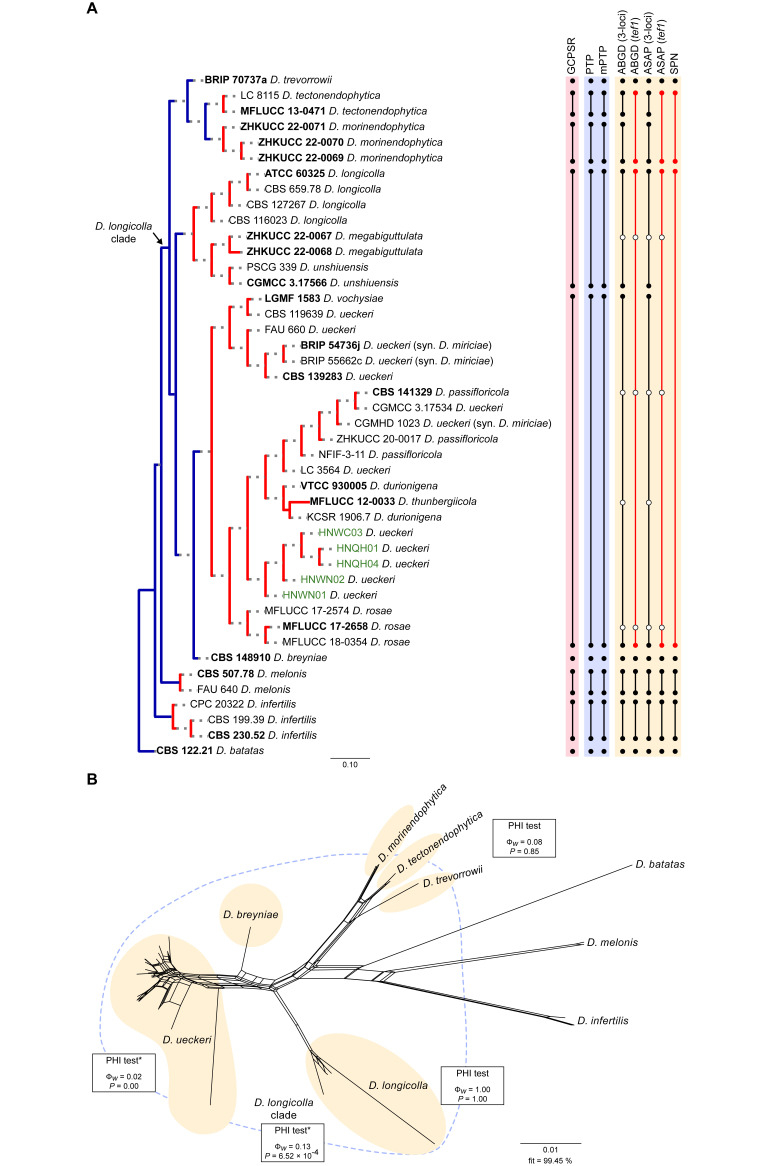

Fig. 9.

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the Diaporthe longicolla clade and closely related species. Bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony (ML-BS/MP-BS ≥ 70 %) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP ≥ 0.90) are shown at the nodes. Strains with type status are indicated in bold font. The isolates from palm tissues included in the analyses are presented in green typeface. Species boundaries within the D. longicolla clade are delimited with coloured blocks and their respective branches are indicated by lettered circles (A–F). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide changes per site. The tree is rooted to D. batatas (CBS 122.21).

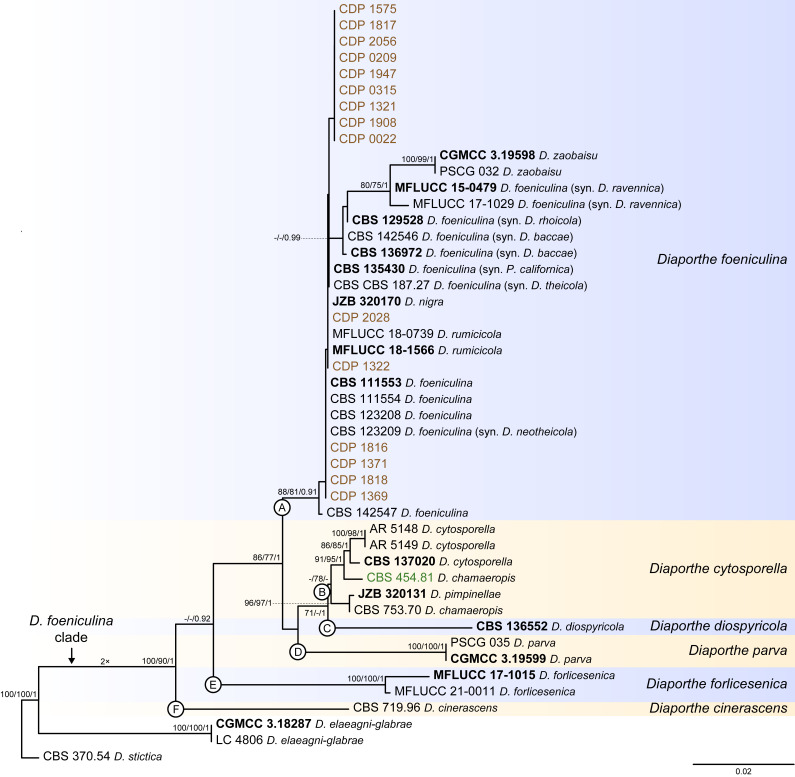

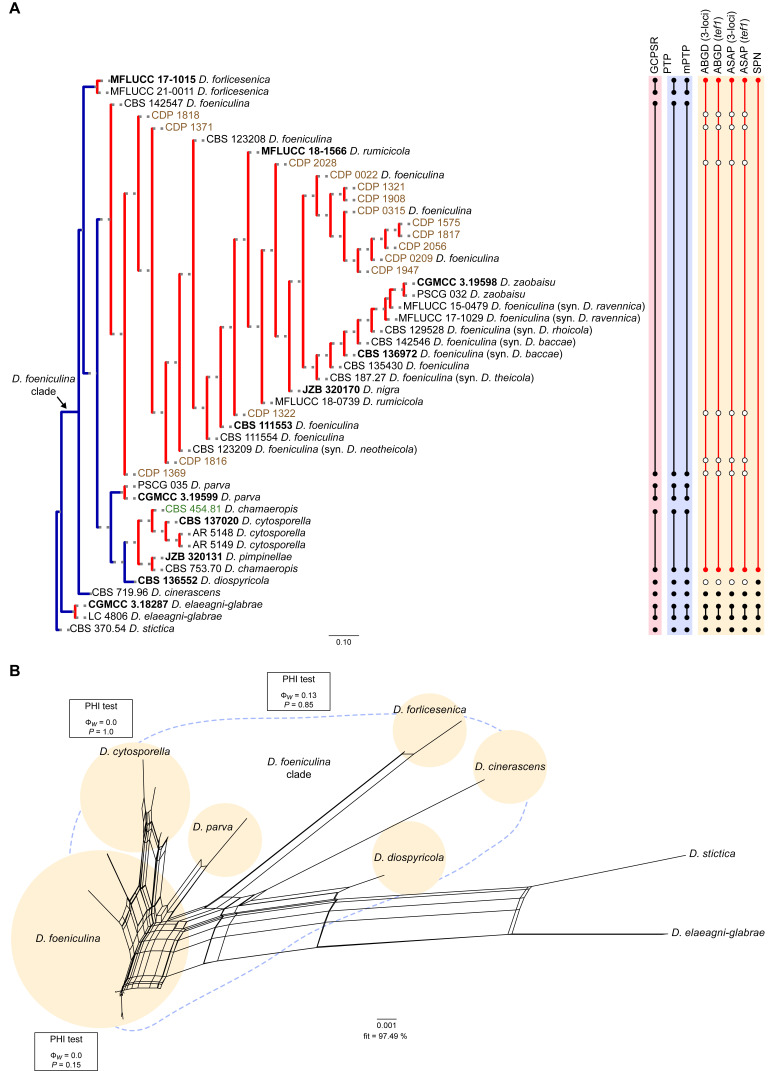

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the Diaporthe foeniculina clade and closely related species. Bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony (ML-BS/MP-BS ≥ 70 %) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP ≥ 0.90) are shown at the nodes. Strains with type status are indicated in bold font. The isolates from this study are presented in brown typeface and the additional isolate from palm tissues included in the analyses is presented in green typeface. Species boundaries within the D. foeniculina clade are delimited with coloured blocks and their respective branches are indicated by lettered circles (A–F). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide changes per site. The tree is rooted to D. stictica (CBS 370.54).

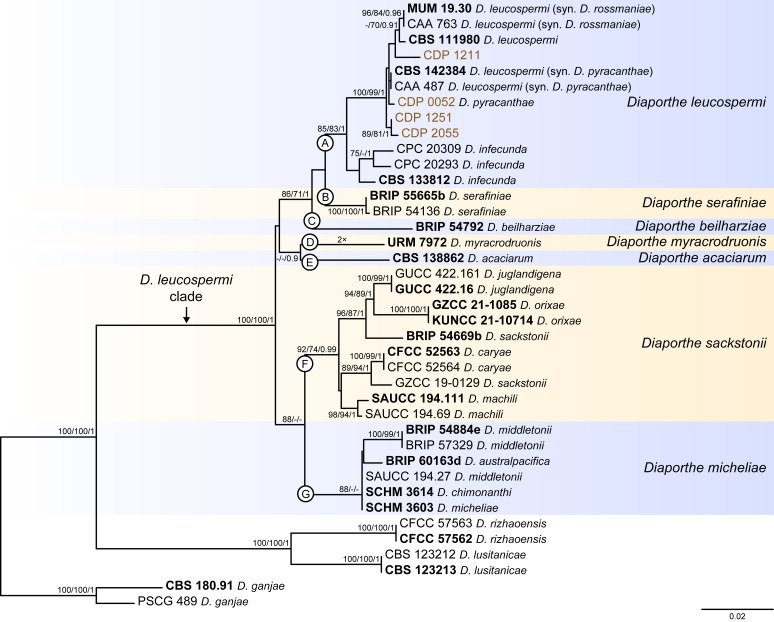

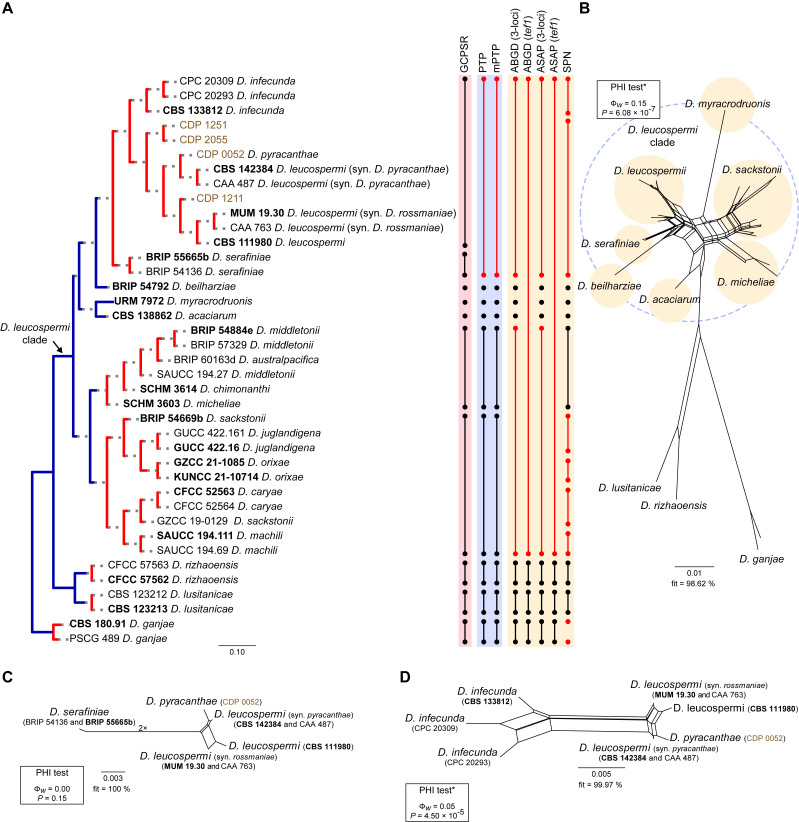

Fig. 8.

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the Diaporthe leucospermi clade and closely related species. Bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony (ML-BS/MP-BS ≥ 70 %) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP ≥ 0.90) are shown at the nodes. Strains with type status are indicated in bold font. The isolates from this study are presented in brown typeface. Species boundaries within the D. leucospermi clade are delimited with coloured blocks and their respective branches are indicated by lettered circles (A–G). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide changes per site. The tree is rooted to D. ganjae (CBS 180.91 and PSCG 489).

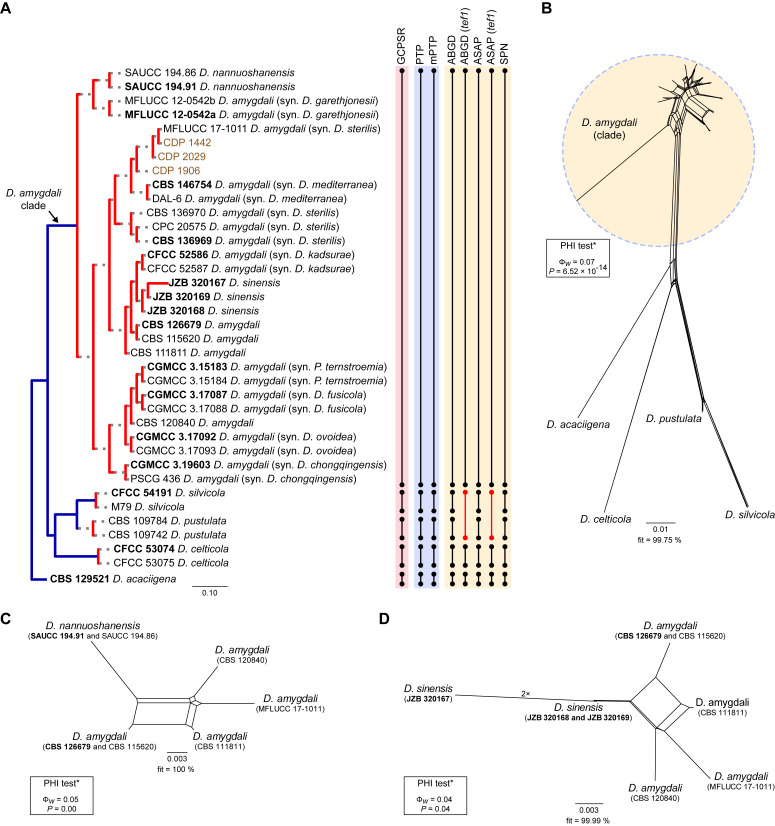

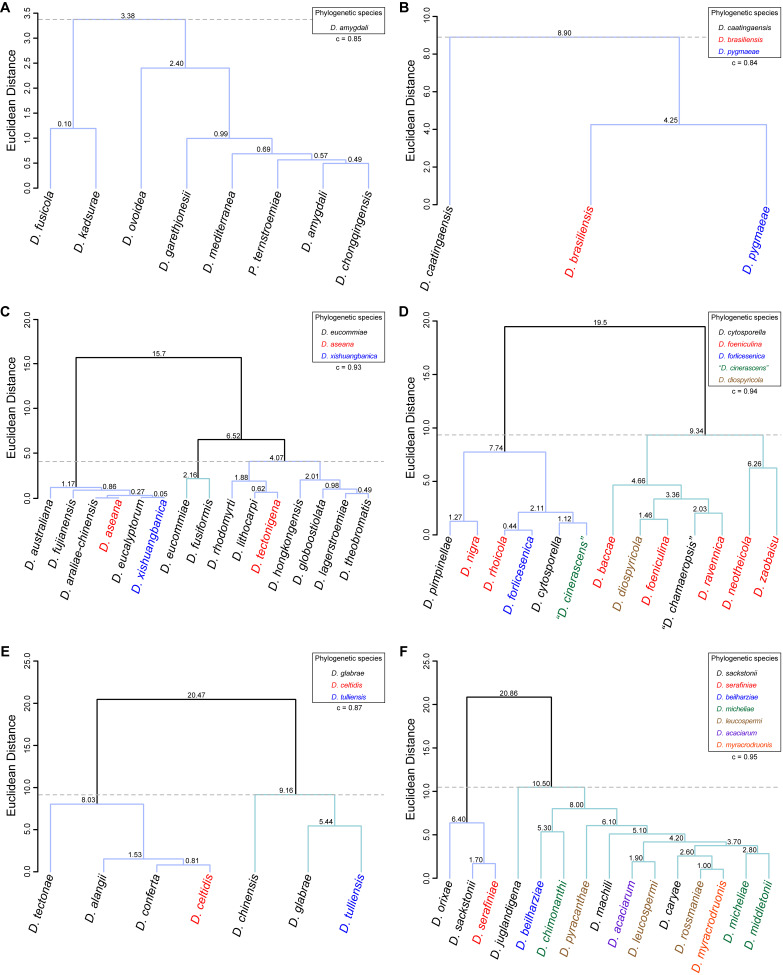

Fig. 2.

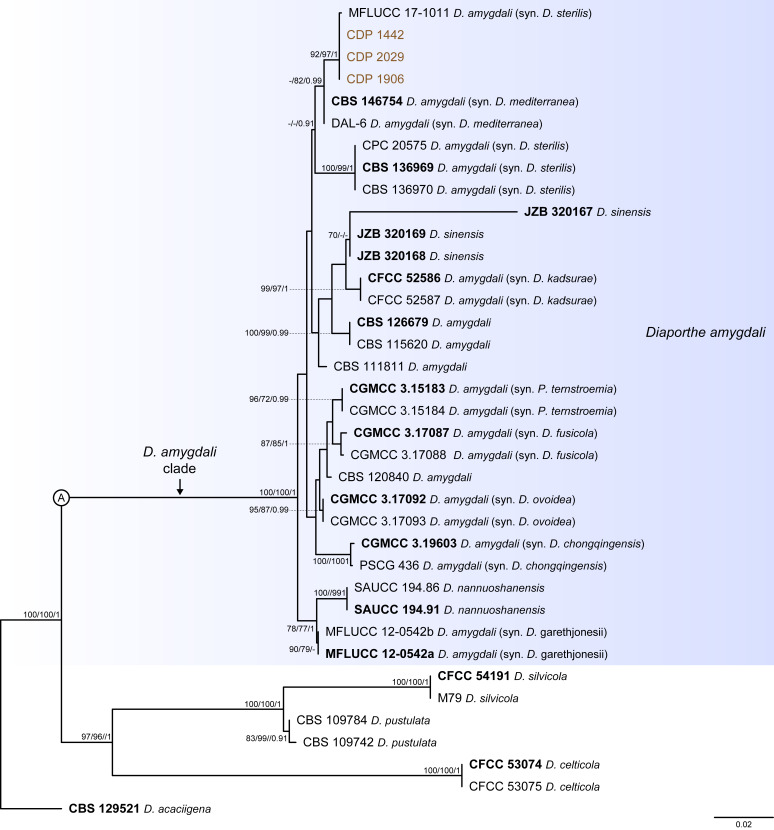

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the Diaporthe amygdali clade and closely related species. Bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony (ML-BS/MP-BS ≥ 70 %) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP ≥ 0.90) are shown at the nodes. Strains with type status are indicated in bold font. The isolates from this study are presented in brown typeface. Species boundaries within the D. amygdali clade are delimited with a coloured block and its respective branch is indicated by a lettered circle (A). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide changes per site. The tree is rooted to D. acaciigena (CBS 129521).

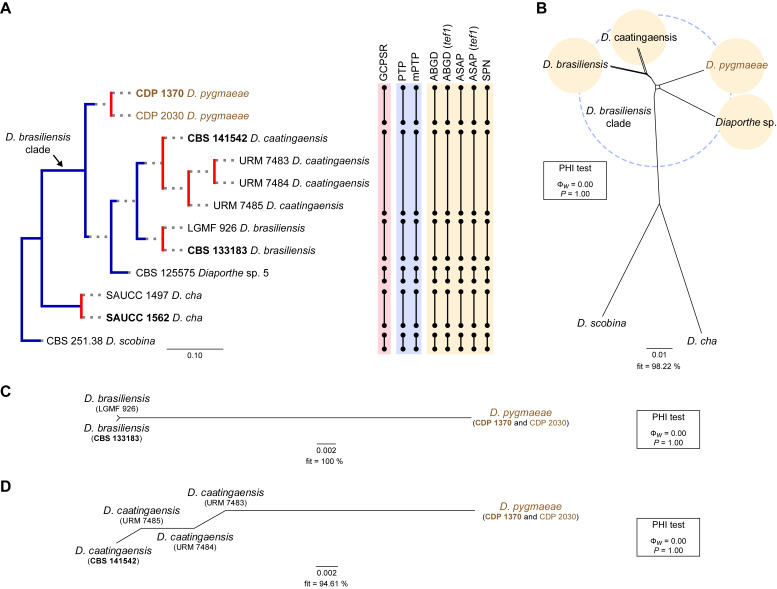

Fig. 3.

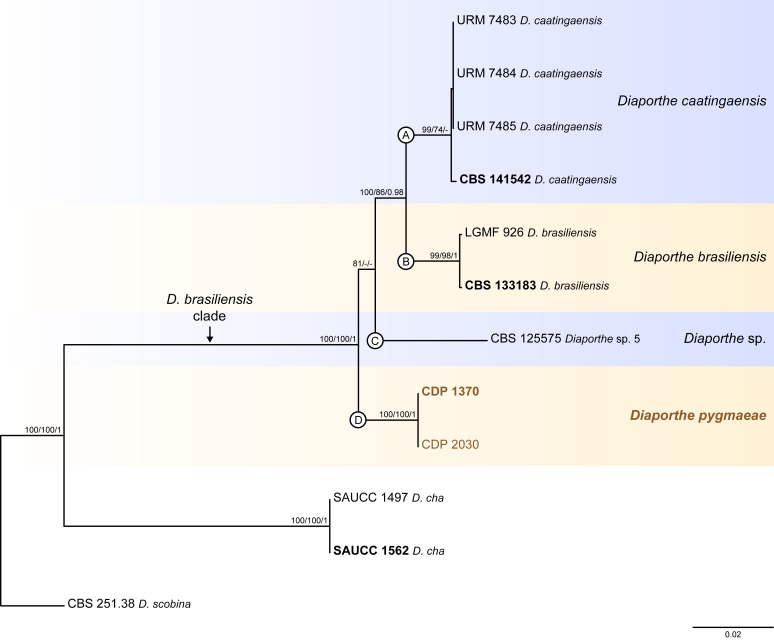

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the Diaporthe brasiliensis clade and closely related species. Bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony (ML-BS/MP-BS ≥ 70 %) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP ≥ 0.90) are shown at the nodes. Strains with type status are indicated in bold font. The isolates from this study are presented in brown typeface. Species boundaries within the D. brasiliensis clade are delimited with coloured blocks and their respective branches are indicated by lettered circles (A–D). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide changes per site. The tree is rooted to D. scobina (CBS 251.38).

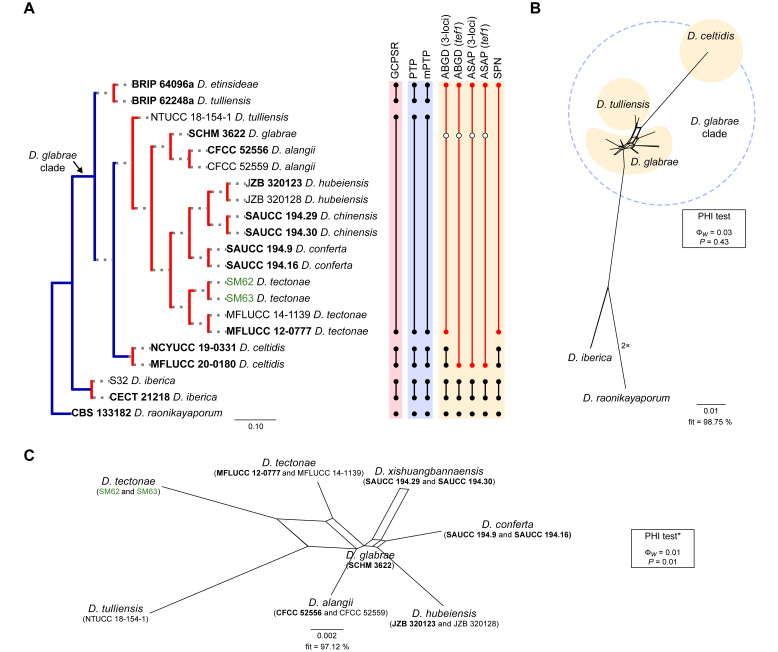

Fig. 6.

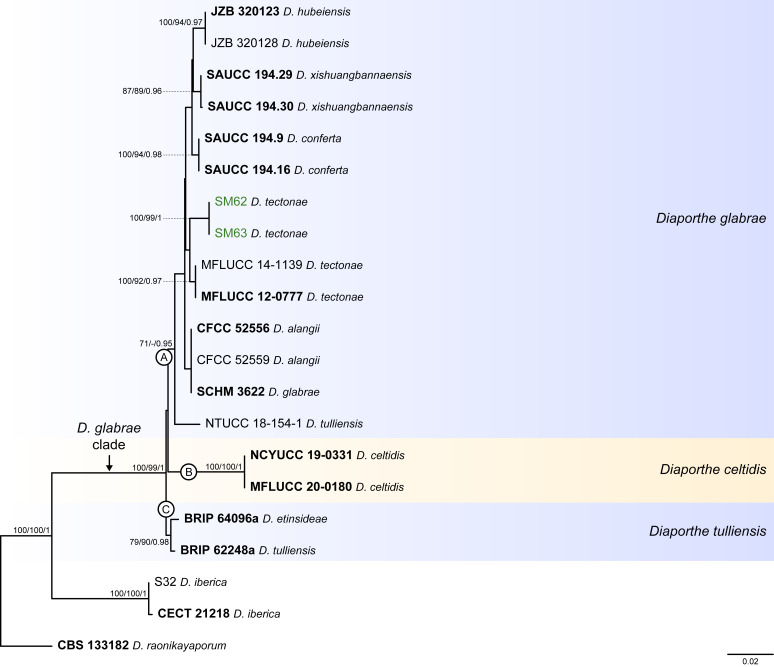

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the Diaporthe glabrae clade and closely related species. Bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony (ML-BS/MP-BS ≥ 70 %) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP ≥ 0.90) are shown at the nodes. Strains with type status are indicated in bold font. The isolates from palm tissues included in the analyses are presented in green typeface. Species boundaries within the D. glabrae clade are delimited with coloured blocks and their respective branches are indicated by lettered circles (A–C). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide changes per site. The tree is rooted to D. raonikayaporum (CBS 133182).

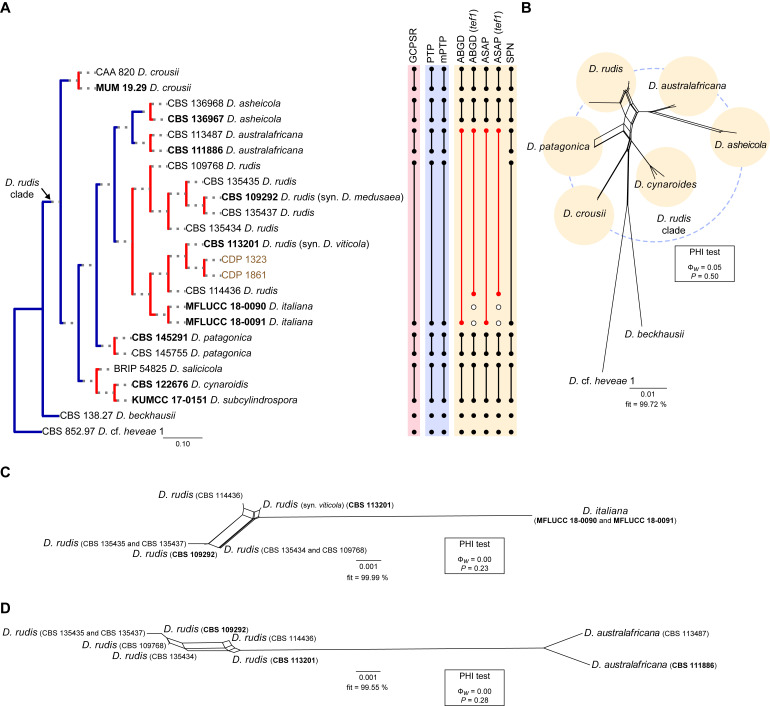

Fig. 10.

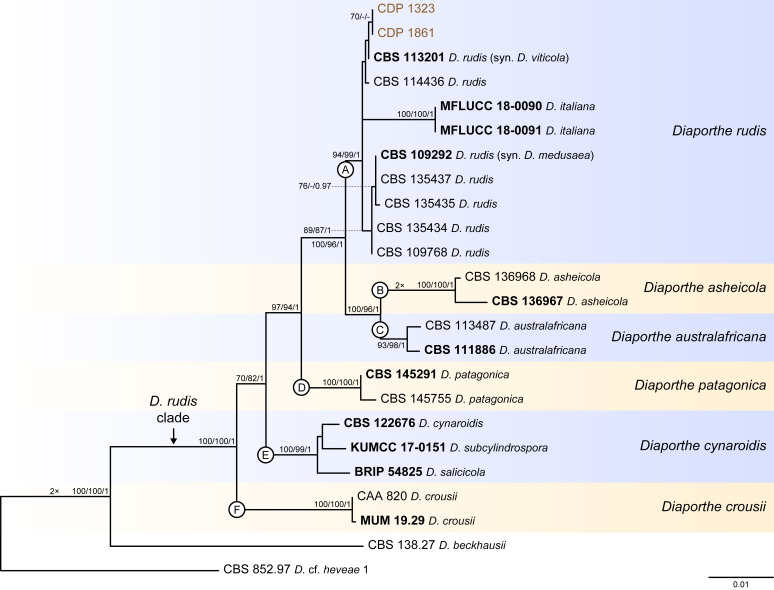

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the Diaporthe rudis clade and closely related species. Bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony (ML-BS/MP-BS ≥ 70 %) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP ≥ 0.90) are shown at the nodes. Strains with type status are indicated in bold font. The isolates from this study are presented in brown typeface. Species boundaries within the D. rudis clade are delimited with coloured blocks and their respective branches are indicated by lettered circles (A–F). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide changes per site. The tree is rooted to D. cf. heveae 1 (CBS 852.97).

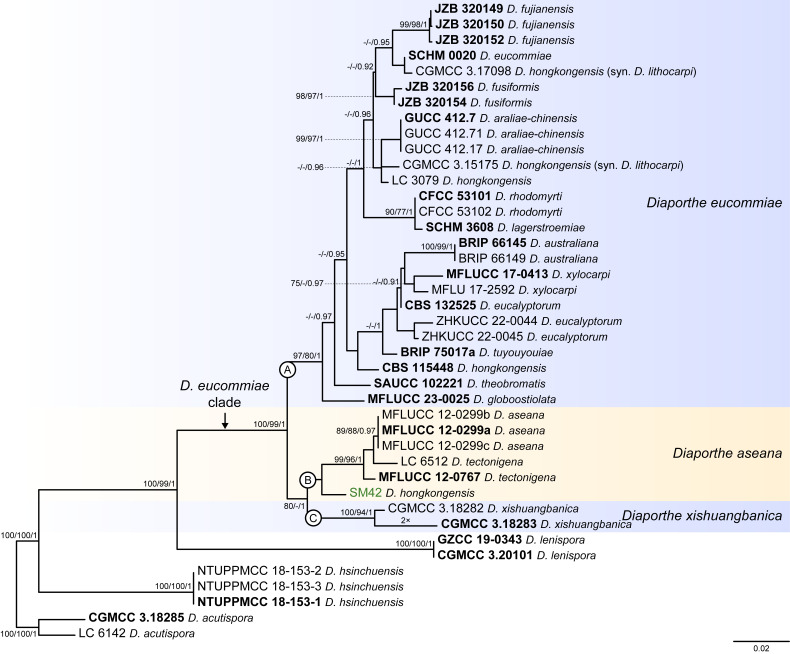

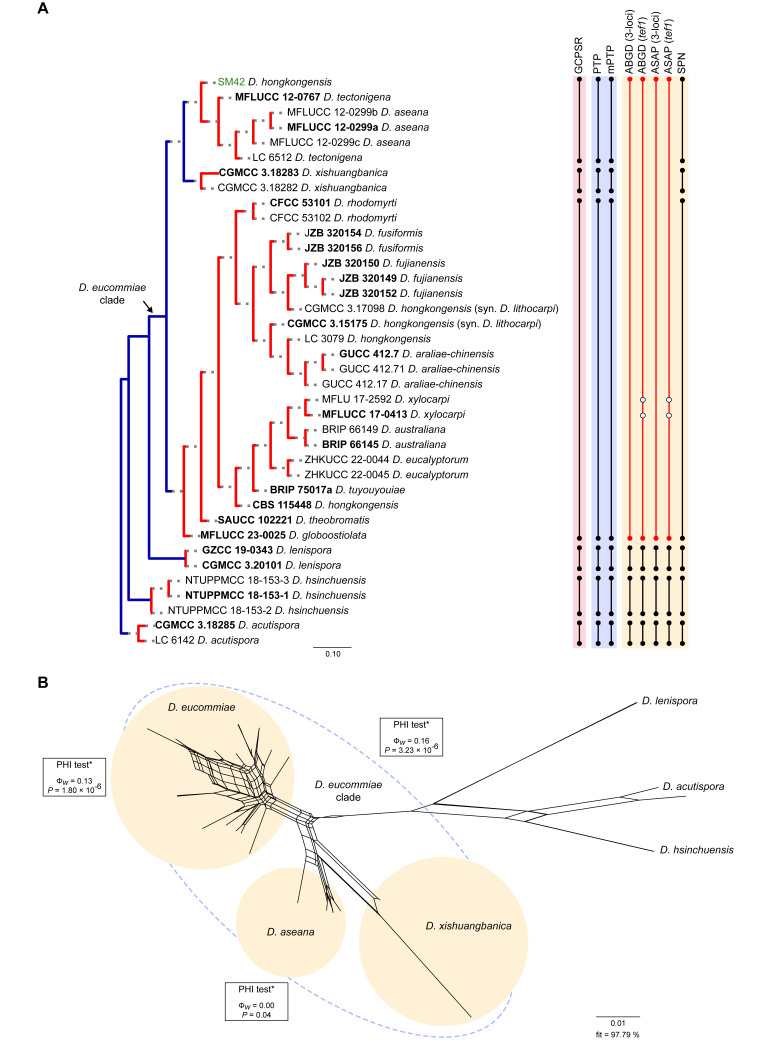

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the Diaporthe eucommiae clade and closely related species. Bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony (ML-BS/MP-BS ≥ 70 %) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP ≥ 0.90) are shown at the nodes. Strains with type status are indicated in bold font. The isolate from palm tissues included in the analyses is presented in green typeface. Species boundaries within the D. eucommiae clade are delimited with coloured blocks and their respective branches are indicated by lettered circles (A–C). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide changes per site. The tree is rooted to D. acutispora (CGMCC 3.18285 and LC 6142).

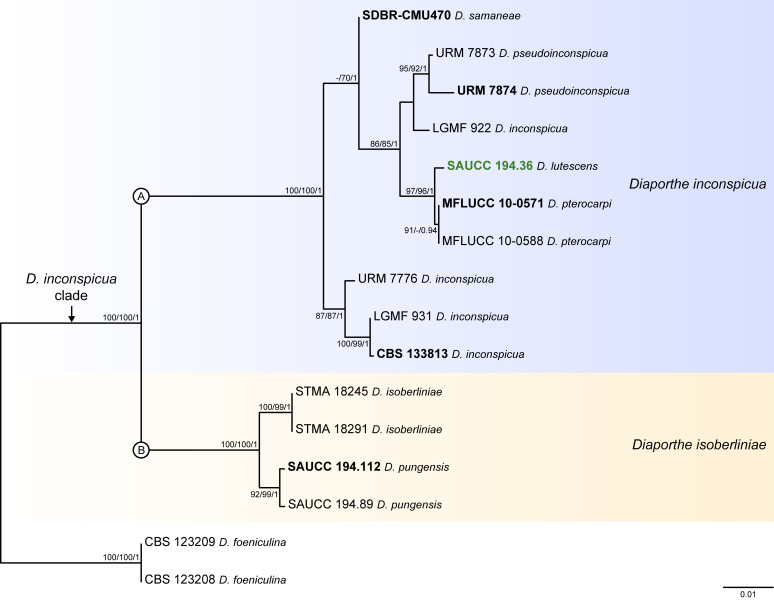

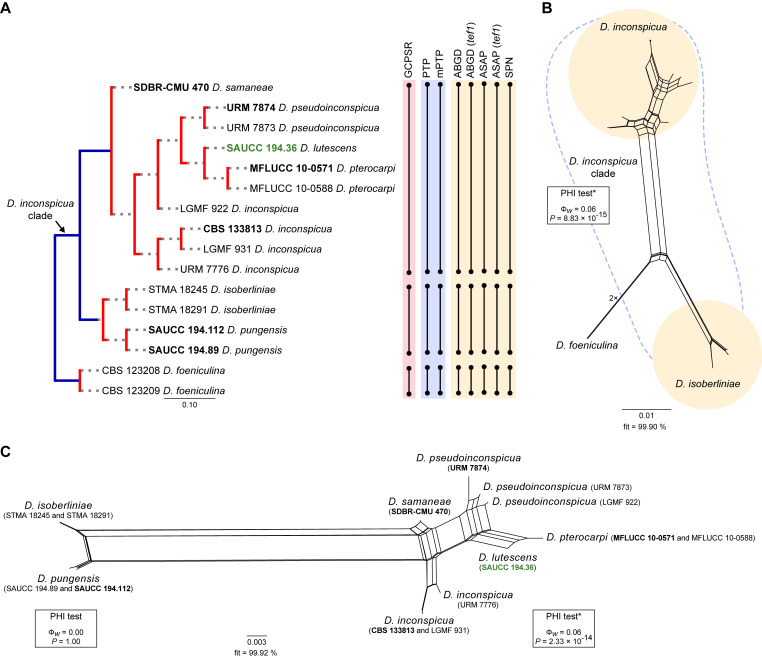

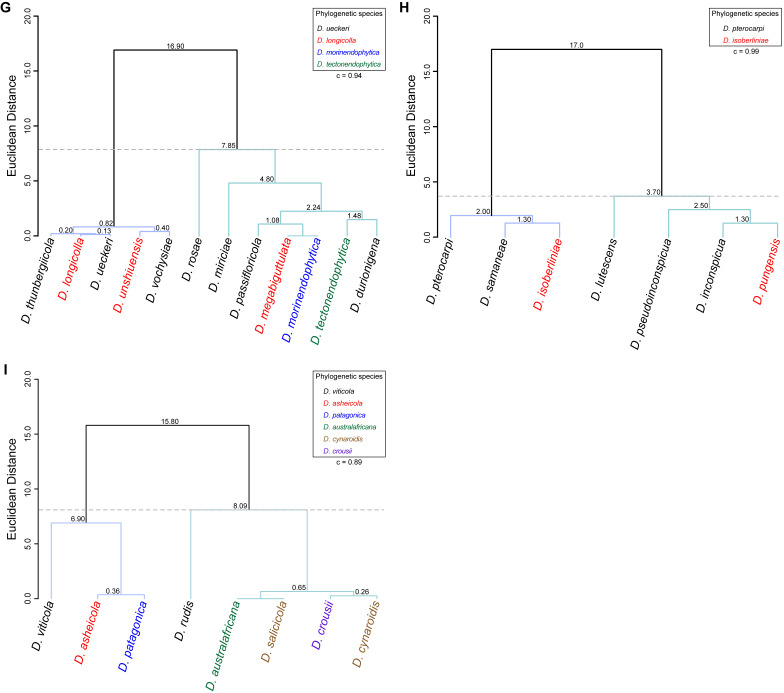

Fig. 7.

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum likelihood analysis based on combined ITS, tef1, tub2, cal and his3 sequence data of the Diaporthe inconspicua clade and closely related species. Bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony (ML-BS/MP-BS ≥ 70 %) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP ≥ 0.90) are shown at the nodes. Strains with type status are indicated in bold font. The isolate from palm tissues included in the analyses is presented in green typeface. Species boundaries within the D. inconspicua clade are delimited with coloured blocks and their respective branches are indicated by lettered circles (A and B). The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide changes per site. The tree is rooted to D. foeniculina (CBS 123208 and CBS 123209).

Diaporthe amygdali clade

Thirty-seven isolates were included in the phylogenetic analyses of the D. amygdali clade, namely 30 ingroup taxa (three obtained in this study, viz. CDP 1442, CDP 1906 and CDP 2029) and seven closely related outgroup taxa (Table 2). Statistics for the different datasets and respective phylogenetic trees are summarised in Table S1. Tree topologies resulting from ML, MP and BA inferences were similar, displaying roughly the same well-resolved terminal clades, mostly supported by high ML/MP-BS (≥ 70 %) and PP (≥ 0.90) values, whose relative position differed only in the MP inference. The ML tree is shown in Fig. 2 with ML-BS/MP-BS/PP values at the nodes. The final likelihood score for the best scoring ML tree was -6875.719343. The BA inference had an average standard deviation of split frequencies (SDSF) and an average potential scale reduction factor (PSRF) of 0.009856 and 1.001, respectively, after 570 000 generations, resulting in 85 502 trees sampled. The MP analysis of 434 parsimony-informative characters (21.5 %) resulted in 180 equally parsimonious trees of 808 steps with a low level of homoplasy as indicated by the measures of homoplasy and character fit (Table S1).

According to the phylogenetic analyses of the concatenated alignment, the three isolates from this study clustered in a highly supported clade (100 % ML-BS / 100 % MP-BS / 1 PP), which was designated here as the D. amygdali clade (clade A in Fig. 2). This clade contained 22 taxa previously recognised as D. amygdali, including its ex-type strain CBS 126679, as well as five taxa belonging to two other Diaporthe species, i.e., D. nannuoshanensis and D. sinensis. Both species appear to be intermingled with taxa previously recognised as D. amygdali, lacking a clear phylogenetic distinction. Moreover, the three strains of D. sinensis did not cluster in highly supported monophyletic lineage (Fig. 2).

Individual ML and MP gene trees were compared to identify concordant branches and accordingly apply the GCPSR principle. All individual ML and MP gene trees were topologically similar, presenting the same well-delimited clades. However, several conflicts were detected between the individual phylogenies of the different loci. Tree topologies between the individual gene genealogies varied substantially, with incongruent branches and most of the internal nodes receiving low or lacking bootstrap support values (Fig. S1). In general, tree topologies of the tef1-(Fig. S1B) and cal-phylograms (Fig. S1D) were more similar to the phylogenetic analyses of the combined dataset. The multilocus phylogenetic analyses showed a better delimitation of the D. amygdali clade when compared to the individual gene genealogies (Fig. 2).

Most individual gene genealogies failed to diagnose D. nannuoshanensis and D. sinensis as well-supported monophyletic lineages, except for tef1- and his3-phylograms (Fig. S1B, E), and ITS-phylograms (Fig. S1A), respectively. In most individual datasets, both species lack phylogenetic distinctiveness from several D. amygdali strains. Moreover, the relationships between both species and the remaining D. amygdali strains are highly discordant among the individual phylogenies (Fig. S1). Following the GCPSR principle, it was verified that the node that delimits the transition from concordant branches to incongruity among branches corresponds to the D. amygdali clade (Fig. 2), which was recovered with high ML/MP-BS values from almost all individual gene trees (-/88 %, 99/100 %, 100/100 %, 100/100 % and 100/100 % in ITS-, tef1-, tub2-, cal- and his3-phylograms, respectively) (Fig. S1). Subsequently, all taxa within the D. amygdali clade seem to be conspecific and were recognised as a single independent evolutionary lineage (IEL). Thus, considering the phylogenetic analyses of the combined dataset, as well as the GCPSR principle, D. nannuoshanensis and D. sinensis are regarded as potential synonyms of D. amygdali.

Diaporthe brasiliensis clade

Twelve isolates were included in the phylogenetic analyses of the D. brasiliensis clade, namely nine ingroup taxa (two obtained in this study, viz. CDP 1370 and CDP 2030) and three closely related outgroup taxa (Table 2). Statistics for the different datasets and respective phylogenetic trees are summarised in Table S2. Tree topologies resulting from ML, MP and BA inferences were similar, and presented the same well-resolved clades for each species included in the analyses, mostly supported by high ML/MP-BS and PP values. The ML tree is shown in Fig. 3 with ML-BS/MP-BS/PP values at the nodes. The final likelihood score for the best scoring ML tree was -5929.692434. The BA inference had an average SDSF and an average PSRF of 0.009819 and 1.001, respectively, after 135 000 generations, resulting in 20 252 trees sampled. The MP analysis of 289 parsimony-informative characters (11.7 %) resulted in one tree of 523 steps with a very low level of homoplasy as indicated by the measures of homoplasy and character fit (Table S2).

According to the phylogenetic analyses, CDP 1370 and CDP 2030 grouped together in a monophyletic lineage with maximum support values (100 % ML-BS / 100 % MP-BB / 1 PP; subclade D in Fig. 3). This formed a distinct subclade sister to D. caatingaensis (subclade A), D. brasiliensis (subclade B) and the strain CBS 125575 (Diaporthe sp. 5) (subclade C) in a well-supported clade (100 % ML-BS / 100 % MP-BS / 1 PP), which was designated here as the D. brasiliensis clade (Fig. 3). Subclade D is here considered to represent a new Diaporthe species, D. pygmaeae, which is introduced below in the Taxonomy section.

Individual ML and MP gene trees were compared to identify concordant branches and accordingly apply the GCPSR principle. All individual ML and MP gene trees were topologically similar, presenting the same well-resolved clades. In addition, almost no conflicts were detected between the individual phylogenies of the different loci, which were topologically similar to the analyses of the concatenated dataset (Figs S2, 3). The only exception was the ITS-phylograms, in which D. caatingaensis strains were paraphyletic (Fig. S2A). Thus, except for D. caatingaensis, all Diaporthe species were well-resolved and constant among phylogenetic trees, insomuch as all individual datasets had similar resolution, displaying the same well-supported groupings as resolved with the combined dataset phylogenies. All species, as well as the D. brasiliensis clade, were recovered with high ML/MP-BS (≥ 86 %) values from almost all individual gene trees (Fig. S2). Following the GCPSR principle, four different IEL were recognised within the D. brasiliensis clade, including an unnamed species, i.e., the strain CBS 125575. Therefore, all individual datasets supported a new subclade in the D. brasiliensis clade as representing a new Diaporthe species. Additionally, the support for D. pygmaeae sp. nov. was provided by base-pair sequence comparisons with the ex-type strains of D. brasiliensis (CBS 133183) and D. caatingaensis (CBS 141542) (detailed information of sequence comparisons are referred to in the Taxonomy section).

Diaporthe eucommiae clade

The phylogenetic analyses of the D. eucommiae clade included 34 ingroup taxa and seven closely related outgroup taxa. The ingroup taxa included one strain from palm substrata retrieved from recent literature, i.e., SM42 identified as D. hongkongensis (Table 2). Statistics for the different datasets and respective phylogenetic trees are summarised in Table S3. Tree topologies resulting from ML, MP and BA inferences were similar, displaying the same well-resolved terminal clades, whose relative position differed only in the MP inference. The ML tree is shown in Fig. 4 with ML-BS/MP-BS/PP values at the nodes. The final likelihood score for the best scoring ML tree was -6645.118752. The BA inference had an average SDSF and an average PSRF of 0.009519 and 1.002, respectively, after 425 000 generations, resulting in 63 752 trees sampled. The MP analysis of 358 parsimony-informative characters (19.1 %) resulted in 1 000 trees of 749 steps with a low level of homoplasy as indicated by the measures of homoplasy and character fit (Table S3).

According to the phylogenetic analyses, the ingroup taxa resolved into three subclades, which clustered in a monophyletic lineage with high support values (100 % ML-BS / 99 % MP-BS / 1 PP), which was designated here as the D. eucommiae clade (Fig. 4). Of these, subclade C represent a well-supported (100 % ML-BS / 94 % MP-BS / 1 PP) single lineage, while subclades A and, at less extent, B displayed substantial substructure (Fig. 4). The strain SM42 clustered with no relevant support values in subclade B, together with five strains belonging to D. aseana and D. tectonigena. These two species grouped in a well-supported lineage (99 % MLBS / 96 % MP-BS / 1 PP) without a clear phylogenetic distinction, since D. tectonigena strains (LC 6512 and MFLUCC 12-0767) did not group into a separate, dichotomous lineage from D. aseana (Fig. 4). Although identified as D. hongkongensis, SM42 did not group with strains previously recognised as D. hongkongensis, including its ex-type strain CBS 115448, and is phylogenetically closer to D. xishuangbanica (CGMCC 3.18282 and GCMCC 3.18283) (subclade C). The ex-type strain and other previously recognised strains of D. hongkongensis grouped together but dispersed among 22 strains belonging to 12 different Diaporthe species in a monophyletic lineage with support values of 97 % ML-BS, 80 % MP-BS and 1 PP (subclade A), namely D. araliaechinensis, D. australiana, D. eucalyptorum, D. eucommiae, D. fujianensis, D. fusiformis, D. globoostiolata, D. lagerstroemiae, D. rhodomyrti, D. theobromatis, D. tuyouyou and D. xylocarpi. Most of the evolutionary relationships between these species lack phylogenetic support and some species present phylogenetic indistinctiveness or even a paraphyletic nature (Fig. 4).

Considering the lack of phylogenetic distinction between the species included in the subclades A and B (Fig. 4), the multilocus phylogenetic inferences suggest that the species boundaries within the D. eucommiae clade are poorly defined, which makes it impossible to correctly classify the isolate from palm substrata included in the analyses. In this sense, the GCPSR principle was applied, and the individual ML and MP gene trees were compared to identify concordant branches. All individual ML and MP gene trees were topologically similar, presenting the same well-delimited clades. However, due to lack of partial sequences of cal and his3 loci for several taxa, IEL are difficult to define, and their boundaries become unclear due to the comparison of datasets with a substantially different number of taxa. Still, several conflicts were detected between the individual phylogenies of the different loci, most of which produced highly discordant branches (Fig. S3), which can be used to predict IEL within the D. eucommiae clade.

While tef1-phylograms presented a very similar topology to that observed with the combined dataset analyses (Figs S3B, 4), most individual phylograms presented a highly variable structure, with different groupings depending on the locus under analysis (Fig. S3). ITS- and tub2-phylograms appear to be the most divergent loci in depicting the evolutionary relationships within the D. eucommiae clade (Fig. S3A, C), although the substantially different number of taxa between gene trees makes it difficult to draw conclusions. In both analyses, the number of discordant branches and lack of phylogenetic support indicate that a single IEL can be recognised within the D. eucommiae subclade. In the ITS-phylograms, some species recognised within the D. eucommiae subclade in the multilocus phylogenetic inferences, clustered together with D. aseana and D. tectonigena (Fig. S3A), with no relevant support values, while in the tub2-phylograms some species clustered as distinct lineages from the D. eucommiae subclade (Fig. S3B). Thus, considering the phylogenetic analyses of the combined dataset and most of the conflicts detected through the GCPRS principle, three IEL are considered in the D. eucommiae clade. Therefore, D. araliae-chinensis, D. australiana, D. eucalyptorum, D. fujianensis, D. fusiformis, D. globoostiolata, D. hongkongensis, D. lagerstroemiae, D. rhodomyrti, D. theobromatis, D. tuyouyou and D. xylocarpi are regarded as potential synonyms of D. eucommiae, and D. tectonigena is regarded as a potential synonym of D. aseana. The third IEL recognised within the D. eucommiae clade, i.e., D. xishuangbanica, was found to represent a distinct well-supported lineage in all individual gene trees for which sequences are available, except for ITS-phylograms (Fig. S3).

Diaporthe foeniculina clade

The phylogenetic analyses of the D. foeniculina clade included 44 ingroup taxa and three closely related outgroup taxa. The ingroup taxa included 15 isolates from this study, namely CDP 0022, CDP 0209, CDP 0315, CDP 1321, CDP 1322, CDP 1369, CDP 1371, CDP 1575, CDP 1816, CDP 1817, CDP 1818, CDP 1908, CDP 1947, CDP 2028 and CDP 2056, and an additional strain from palm substrata retrieved from recent literature, i.e., CBS 454.81 identified as D. chamaeropis (Table 2). Statistics for the different datasets and respective phylogenetic trees are summarised in Table S4. Tree topologies resulting from ML, MP and BA inferences were similar, presenting generally the same well-resolved clades, although few terminal clades were different in the MP inference. The ML tree is shown in Fig. 5 with ML-BS/MP-BS/PP values at the nodes. The final likelihood score for the best scoring ML tree was -4865.036992. The BA inference had an average SDSF and an average PSRF of 0.009423 and 1.003, respectively, after 260 000 generations, resulting in 39 002 trees sampled. The MP analysis of 191 parsimony-informative characters (10.0 %) resulted in 1 000 trees of 400 steps with a low level of homoplasy as indicated by the measures of homoplasy and character fit (Table S4).

According to the phylogenetic analyses, the ingroup taxa resolved into six moderately to highly supported subclades. The 15 isolates from this study clustered in a well-supported subclade (88 % ML-BS / 81 % MP-BS / 0.91 PP), dispersed among 17 other Diaporthe strains (subclade A in Fig. 5). This subclade contains 11 taxa previously recognised as D. foeniculina, as well as five taxa belonging to three other Diaporthe species, i.e., D. nigra, D. rumicicola and D. zaobaisu. Diaporthe rumicicola and D. nigra cannot be distinguished from D. foeniculina strains considering the concatenated sequence analyses conducted, given that both species lack either support values and/or relevant branch length (Fig. 5). Although D. zaobaisu grouped in a well-supported lineage with a substantial relative branch length within the above-mentioned subclade, all three species appear to be intermingled among other strains previously recognised as D. foeniculina, lacking a clear phylogenetic distinction. The strain CBS 454.81 (D. chamaeropis) clustered in a sister subclade, supported by moderate ML-BS support value (78 %; subclade B), together with five Diaporthe strains, including two different species (D. cytosporella and D. pimpinellae) and another D. chamaeropis strain (CBS 753.70), which seems to be paraphyletic in relation to CBS 454.81. Both subclades clustered in a monophyletic lineage, together with D. diospyricola (subclade C), D. parva (subclade D), D. forlicesenica (subclade E) and D. cinerascens (subclade F), with high support values (100 % ML-BS / 90 % MP-BS / 1 PP), which was designated here as the D. foeniculina clade (Fig. 5).

To test the conflicts detected through the analyses of the concatenated dataset, the individual ML and MP gene trees were compared to identify concordant branches and define the IEL within the D. foeniculina clade, according to the GCPSR principle. All individual ML and MP gene trees were topologically similar, presenting the same well-delimited clades. As for the previous clade, the results of the GCPSR principle should be carefully interpreted due to lack of partial sequences of cal and his3 loci for several taxa and, subsequently, comparison of datasets with a substantially different number of taxa. Even so, several conflicts were detected between the individual phylogenies of the different loci, particularly among taxa composing the subclades that include D. foeniculina and D. chamaeropis strains (subclades A and B in Fig. 5), suggesting that strains in both lineages are conspecific. In both subclades, species are paraphyletic or produce polytomies in most individual gene genealogies, or even present phylogenetic indistinctiveness in different combinations of taxa depending on the locus under analysis (Fig. S4). In general, tree topologies of the tef1-phylograms (Fig. S4B) and cal-phylograms (Fig. S4D) were more similar to the phylogenetic analyses of the combined dataset. The multilocus phylogenetic analyses showed a better delimitation of the D. foeniculina clade when compared to the individual gene genealogies.

The phylogenetic position and distinction of D. zaobaisu is not clear, since it appears to be a distinct well-supported (ML-BS and/or MP-BS ≥ 82 %) lineage sister to D. foeniculina in tef1-, tub2- and his3-phylograms (Fig. S4B, C, E), but cannot be recognised as a distinct clade on ITS-phylograms (Fig. S4A) and on the multilocus phylogenies (Fig. 5). No cal partial sequences are available to confirm the evolutionary relationships of D. zaobaisu with D. foeniculina strains. Thus, considering the phylogenetic analyses of the combined dataset, as well as the GCPSR principle, D. nigra, D. rumicicola and D. zaobaisu are regarded as potential synonyms of D. foeniculina, and D. chamaeropis and D. pimpinellae are regarded as potential synonyms of D. cytosporella. The remaining IEL recognised within the D. foeniculina clade, i.e., D. cinerascens, D. diospyricola, D. forlicesenica and D. parva, were found to clear represent distinct well-supported lineages in most individual gene trees for which sequences are available. (Fig. S4).

Diaporthe glabrae clade

The phylogenetic analyses of the D. glabrae clade included 18 ingroup taxa and three closely related outgroup taxa. The ingroup taxa included two strains from palm substrata retrieved from recent literature, i.e., SM62 and SM63, both identified as D. tectonae (Table 2). Statistics for the different datasets and respective phylogenetic trees are summarised in Table S5. Tree topologies resulting from ML, MP and BA inferences were similar, and presented the same groupings with the same relative positions for each species included in the analyses, mostly supported by high ML/MP-BS and PP values. The ML tree is shown in Fig. 6 with ML-BS/MP-BS/PP values at the nodes. The final likelihood score for the best scoring ML tree was -4757.046661. The BA inference had an average SDSF and an average PSRF of 0.009705 and 1.001, respectively, after 410 000 generations, resulting in 30 751 trees sampled. The MP analysis of 184 parsimony-informative characters (9.6 %) resulted in 114 trees of 412 steps with a very low level of homoplasy as indicated by the measures of homoplasy and character fit (Table S5).

According to the phylogenetic analyses, SM62 and SM63 clustered in a well-supported subclade (71 % ML-BS / 0.97 PP; subclade A in Fig. 6), together with 11 strains belonging to six different Diaporthe species, i.e., D. alangii, D. conferta, D. glabrae, D. hubeiensis, D. chinensis and D. tectonae, as well as the strain NTUCC 18-154-1 identified as D. tulliensis. Most species in this subclade are well-resolved in monophyletic lineages with high support values, except for the lineage of the ex-type strains of D. alangii (CFCC 52556) and D. glabrae (SCHM 3622). This lineage did not present relevant support values, and both species are phylogenetically indistinct. Even so, the relative branch lengths in the entire clade are small and the strains from palm tissues (SM62 and SM53), which are identified as D. tectonae, did not cluster with the ex-type strain of D. tectonae (MFLUCC 12-0777) with relevant support values (Fig. 6). Similarly, the strain NTUCC 18-154-1 (D. tulliensis) did not cluster with the ex-type strain of D. tulliensis (BRIP 62248a), which grouped in a separate lineage, together with D. etinsideae, with moderate to high support values (79 % MLBS / 90 % MP-BS / 0.98 PP; subclade C), although with very small relative branch lengths (Fig. 6). Subclades A and C, together with D. celtidis (subclade B), clustered in a monophyletic lineage with support values of 100 % ML-BS, 99 % MP-BS and 1 PP, which was designated here as the D. glabrae clade (Fig. 6).

Individual ML and MP gene trees were compared to identify concordant branches and accordingly apply the GCPSR principle. All individual ML and MP gene trees were topologically similar, presenting the same well-delimited clades. However, some strains in the D. glabrae clade presented conflicts between the individual phylogenies of the different loci (Fig. S5). As previously mentioned, IEL should be carefully interpreted when applying the GCPSR principle due to lack of partial sequences of cal and his3 loci for several taxa. In general, tree topologies of the tub2-phylograms (Fig. S5C) were more similar to the phylogenetic analyses of the combined dataset. The multilocus phylogenetic analyses showed a better delimitation of the D. glabrae clade when compared to the individual gene genealogies (Fig. 6).

Considering the ITS-phylograms (Fig. S5A), most species from subclade A (Fig. 6) presented phylogenetic indistinctiveness. In tef1- and tub2-phylograms (Fig. S5B, C), although most species are apparently well-resolved, their groupings are highly discordant among the two loci. Most species with available sequences for cal and his3 loci, also presented phylogenetic indistinctiveness (Fig. S5D, E). Moreover, the ex-type strains of D. tulliensis (BRIP 62248a) and D. etinsideae (BRIP 64096a) are barely distinguishable in ITS-, tef1 and tub2-phylograms, with very inconspicuous relative branch lengths, suggesting that they are conspecific, while D. celtidis strains clustered as an independent lineage in all three individual gene genealogies (Fig. S5A–C). Thus, considering the phylogenetic analyses of the combined dataset, as well as the GCPSR principle, three IEL can be recognised within the D. glabrae clade, insomuch as D. alangii, D. conferta, D. hubeiensis, D. tectonae and D. xishuangbannaensis are regarded as potential synonyms of D. glabrae, and D. etinsideae is regarded as a potential synonym of D. tulliensis.

Diaporthe inconspicua clade

Sixteen isolates were included in the phylogenetic analyses of the D. inconspicua clade, namely 14 ingroup taxa and two closely related outgroup taxa. The ingroup taxa included one strain from palm substrata retrieved from recent literature, i.e., SAUCC 194.36, which corresponds to D. lutescens isolated from leaves of Chrysalidocarpus lutescens in Yunnan (Table 2). Statistics for the different datasets and respective phylogenetic trees are summarised in Table S6. Tree topologies resulting from ML, MP and BA inferences were similar, and presented the same well-resolved clades with the same relative positions for each species included in the analyses, supported by high ML-BS, MP-BS and PP values. The ML tree is shown in Fig. 7 with ML-BS/MP-BS/PP values at the nodes. The final likelihood score for the best scoring ML tree was -4017.269368. The BA inference had an average SDSF and an average PSRF of 0.008328 and 1.024, respectively, after 5 000 generations, resulting in 752 trees sampled. The MP analysis of 202 parsimony-informative characters (11.1 %) resulted in one tree of 264 steps with a low level of homoplasy as indicated by the measures of homoplasy and character fit (Table S6).

According to the phylogenetic analyses, D. lutescens (SAUCC 194.36) clustered in a monophyletic lineage with maximum support values (100 % ML-BS / 100 % MP-BS / 1 PP) together with nine strains belonging to four Diaporthe species, i.e., D. inconspicua, D. pseudoinconspicua, D. pterocarpi and D. samaneae (subclade A in Fig. 7). While most species in this lineage are well-resolved, strains identified as D. inconspicua are paraphyletic. Moreover, the relative length of the branches between D. lutescens and D. pterocarpi is very small and the two species are almost phylogenetically indistinguishable (Fig. 7). This lineage is sister to another subclade with maximum support values that includes two Diaporthe species, i.e., D. isoberliniae and D. pungensis, both apparently well-resolved (subclade B in Fig. 7). In a more general view, both subclades clustered in a monophyletic lineage with maximum support values, which was designated here as the D. inconspicua clade (Fig. 9). It is worth mentioning that the ex-type strain of D. isoberliniae (CBS 137981) was not included in the phylogenetic inferences conducted here. Only the sequences for ITS and tub2 loci are available for this strain, which results in a negative impact on the robustness and overall support of the phylogenetic inferences. However, ML phylogenetic inferences have been conducted to confirm that the D. isoberliniae strains used (STMA 18245 and STMA 18291) are related to its ex-type strain (data not shown).

Individual ML and MP gene trees were compared to identify concordant branches and accordingly apply the GCPSR principle. All individual ML and MP gene trees were topologically similar, presenting the same well-delimited clades. However, several conflicts were detected between the individual phylogenies of the different loci. None of the individual phylogenies displayed a similar topology to that observed in the multilocus phylogenetic analyses (Figd S6, 7). In most individual gene genealogies, all strains included in the subclade A presented phylogenetic indistinctiveness and the evolutionary relationships established are highly discordant (Fig. S6). For instance, D. lutescens is phylogenetically indistinct from D. pterocarpi in the cal-phylograms (Fig. S6D) and from D. samaneae in the his3-phylograms (Fig. S6E), while it lacks phylogenetic distinctiveness from most species in the subclade A in the tef1- and tub2-phylograms (Fig. S6B, C). Similarly, D. isoberliniae and D. pungensis are phylogenetically indistinct in tef1- and cal-phylograms, where the lineage is composed by polytomies for all or some of the strains (Fig. S6B, D). Only the ITS-phylograms displayed a roughly similar topology to that observed in the multilocus phylogenetic inferences, although some species remained unresolved in polytomies and/or in paraphyletic branches (Fig. S6A). Thus, considering the phylogenetic analyses of the combined dataset, as well as the GCPSR principle, two IEL can be recognised within the D. inconspicua clade, insomuch as D. lutescens, D. pseudoinconspicua, D. pterocarpi and D. samaneae are regarded as potential synonyms of D. inconspicua, and D. pungensis is regarded as a potential synonym of D. isoberliniae.