Abstract

The overall structural integrity plays a vital role in the unique performance of living organisms, but the integral synchronous preparation of different multiscale architectures remains challenging. Inspired by the cuttlebone’s rigid cavity-wall structure with excellent energy absorption, we develop a robust hierarchical predesigned hydrogel assembly strategy to integrally synchronously assemble multiple organic and inorganic micro-nano building blocks to different structures. The two types of predesigned hydrogels, combined with hydrogen, covalent bonding, and electrostatic interactions, are layer-by-layer assembled into brick-and-mortar structures and close-packed rigid micro hollow structures in a cuttlebone-inspired structural material, respectively. The cuttlebone-inspired structural materials gain crack growth resistance, high strength, and energy absorption characteristics beyond typical energy-absorbing materials with similar densities. This hierarchical hydrogel integral synchronous assembly strategy is promising for the integrated fabrication guidance of bioinspired structural materials with multiple different micro-nano architectures.

Subject terms: Bioinspired materials, Mechanical properties, Gels and hydrogels

For bioinspired structural materials, integral preparation of multiscale structures remains challenging. The authors report a hierarchical strategy to assemble multiple micro-nano units to complex multiscale structures integrally synchronously.

Introduction

Biological structural materials obtain extraordinary properties, e.g., excellent strength, toughness, or energy absorption, from simple building blocks, which can be attributed mainly to their cross-scale hierarchical structures achieved by highly ordered combinations and coordination of various meta-structures1–4. Natural structures have provided precious inspiration for developing engineering materials, such as brick-and-mortar and prismatic structures of nacre5–7, and vertically oriented micro-channels of natural wood8,9. To date, various methods have been created and further developed to construct the bioinspired architecture, including 3D printing10–12, freeze casting13,14, biomimetic mineralization15, layer-by-layer assembly16–19, self-assembly and externally induced assembly20–22, and so on. These methods can be used to preliminarily fabricate bioinspired meta-architectures, effectively demonstrating the advancement of bioinspired structural design.

Although manufacturing a single type of bioinspired meta-structure has notable success, the integrated preparation of the overall architecture of high-performance natural structural materials is not a low-hanging fruit. The overall structural integrity plays a vital role in embodying unique performance for the survival of living things23–26. As a typical example, cuttlebone can effectively withstand tremendous hydrostatic pressure from the deep sea26,27, owing to its overall rigid cavity-wall structure (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Under external loads, the rigid cavity can absorb the energy by sufficient crushing, and the rigid wall can disperse the stress when the rigid cavity layer breaks and fails, significantly improving the damage tolerance and energy absorption of the material to effectively avoid catastrophic failure of the bulk material26–28. This ingenious structure results in high specific stiffness and energy absorption over the stainless-steel foam due to the structural integrity and coordination of each meta-structure26. Several groups have attempted to construct multiple sophisticated structures like cuttlebones with an overall architecture27–29. Nevertheless, the design and fabrication of these materials are mainly on the macroscopic scale, which does not reach the micro-nano scale and multiple organic/inorganic complex components of the original overall natural architecture. This is because solving multiscale structural design and cross-scale cooperative assembly problems of complex organic and inorganic components is challenging. Different scales need to be considered, including the interaction between complex organic and inorganic building elements, orderly and controllable assembly at micro- and nano-scales, and orderly arrangement at larger scales. Unfortunately, it remains an open issue to realize the integral synchronous assembly of different meta-structures in bioinspired structural materials by coordinating the ordered assembly and arrangement of micro-nano building blocks.

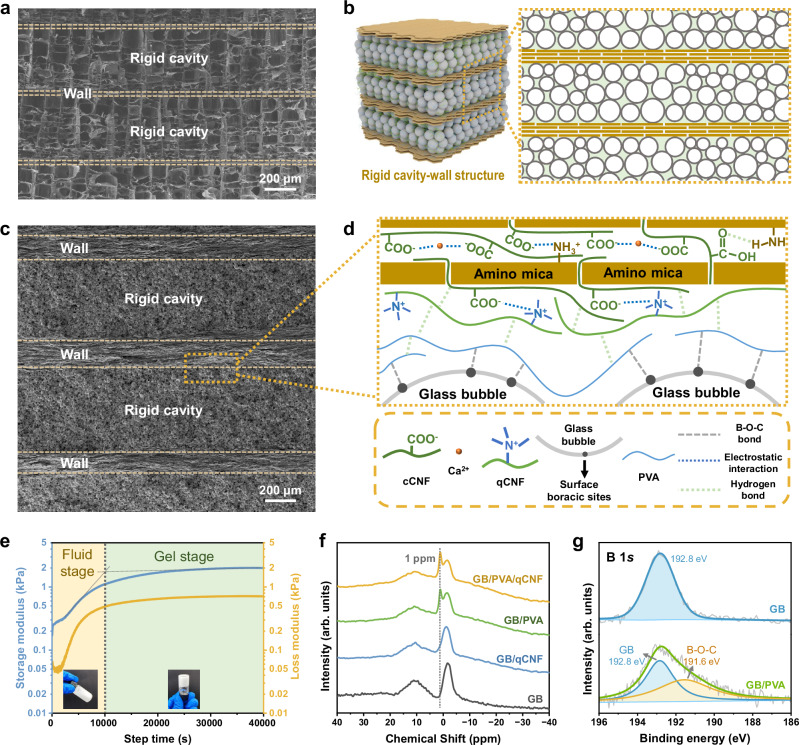

Fig. 1. Design, structure, and interaction characterization of rigid cavity-wall structural material (RCWSM).

a Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the natural cuttlebone. b Structural design of the RCWSM. c SEM image of the RCWSM. d Multiple interactions of building blocks within the RCWSM. e The rheological properties of the GB/PVA/qCNF initial gel of rigid cavity layer. GB glass bubble, PVA polyvinyl alcohol, qCNF quaternized cellulose nanofiber. Insets are photographs of the initial gel at the fluid stage (left) and gel stage (right). f Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (11B) of the GB/PVA/qCNF, GB/PVA, GB/qCNF, and GB samples. g B 1s X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of the GB and GB/PVA samples.

Here, inspired by the rigid cavity-wall structure of cuttlebone, we designed a robust hierarchical predesigned hydrogel integral synchronous assembly strategy to construct exquisitely integrated micro-nano architecture with different meta-structures (Supplementary Fig. 2). The close-packed rigid low-density structure of hollow glass bubble (GB) was designed as the rigid cavity layer, and the brick-and-mortar structure was used as the wall layer (Fig. 1b). By regulating the interaction between the two types of hydrogels, we ordered assembled multiple organic and inorganic micro-nano building blocks and integrally fabricated rigid cavity-wall structural material (RCWSM) with excellent energy absorption properties (Fig. 1c, d).

Results

Material design and fabrication strategy

To fabricate a cuttlebone-inspired rigid cavity-wall exquisite structure on the micro-nano scale, we detailedly analyzed and designed the wall layer and rigid cavity layer in sequence. According to our previous works22,30, the cellulose nanofiber (CNF)-based brick-and-mortar structure has demonstrated crack extension resistance and satisfactory damage tolerance, avoiding catastrophic failure of the bulk material and thus making it a suitable choice for the wall layer. The mica was treated with (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane to achieve surface amino functionalization (Supplementary Figs. 3–5), realizing electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding with carboxylated CNF (cCNF) (Supplementary Figs. 6–8). Through further Ca2+ crosslinking, the designed wall layer hydrogel was prefabricated (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

The core of the rigid cavity layer is to construct rigid and low-density structures, which is challenging. GB is made of borosilicate glass with a typical microscale rigid hollow cavity that demonstrates low density, selected as the skeleton building blocks for the rigid cavity layer (Supplementary Figs. 9–11). The hydroxyl-rich polymer, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), was used to bond GB together. During the mixing process, the viscosity and modulus of the mixture gradually increased, causing obvious gelation (Supplementary Fig. 12). The quaternized CNF (qCNF) was introduced to the GB/PVA mixture to construct nanonetworks and improve the modulus and strength (Supplementary Figs. 13–15). The rheology test results reveal that the modulus and viscosity increase visibly and eventually flatten out with time, from which a time window of nearly 10,000 s for easy processing molding could be estimated (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 16). No noticeable multi-order modulus variation is observed in the GB/qCNF mixed system (Supplementary Fig. 17). The above results demonstrate a particular interaction between PVA and GB. Considering the boron sites on the surface of GB (Supplementary Fig. 9), we speculate that the hydroxyl groups on the PVA chain and the boracic sites on the GB surface form B–O–C bonds.

Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were also performed to study the interaction mechanism between PVA and GB. 11B NMR data reveals an apparent new signal peak from the GB/PVA and the GB/PVA/qCNF samples, which is not present in the other control samples (Fig. 1f). This phenomenon shows that strong interactions occurred between PVA and GB31,32. Moreover, a 191.6 eV signal is detected in the XPS results (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 18), which is attributed to the B–O–C bond33,34. Thus, GB could also be regarded as a solid-state crosslinking reagent in the rigid cavity layer induced by the B–O–C bond within the hydroxyl groups of PVA and boracic sites of the GB surface (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

To fabricate the close-packed rigid micro hollow structure, we regulated the composition and content of the energy-absorbing layer. PVA can bond with GB, protecting GB from breaking to some extent. A suitable qCNF mass content (PVA:qCNF=3:1) addition can enhance the stiffness and strength of the GB/PVA/qCNF hydrogel, which can form a nanonetwork to protect GB from sliding to push against each other during the dehydration and assembly process (Supplementary Fig. 19). Under the above preconditions, with the change in GB content, the compaction structure changes from no close packing for a low GB content to GB cavity structure failure for GB overfilling during dehydration and assembly (Supplementary Fig. 20). Therefore, considering the compaction of the effective rigid cavity, a 50 wt% mass content of GB is appropriate for the fabrication of a close-packed rigid cavity layer with a low density of ~0.58 g cm−3 (Supplementary Table 1).

The predesigned wall and rigid cavity layer hydrogels were assembled successively and then dehydrated and densified (Supplementary Fig. 2). In this process, multiple micro-nano building blocks were orderly arranged to form the designed rigid cavity-wall structure with a density of ~0.79 g cm−3 (Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Fig. 21).

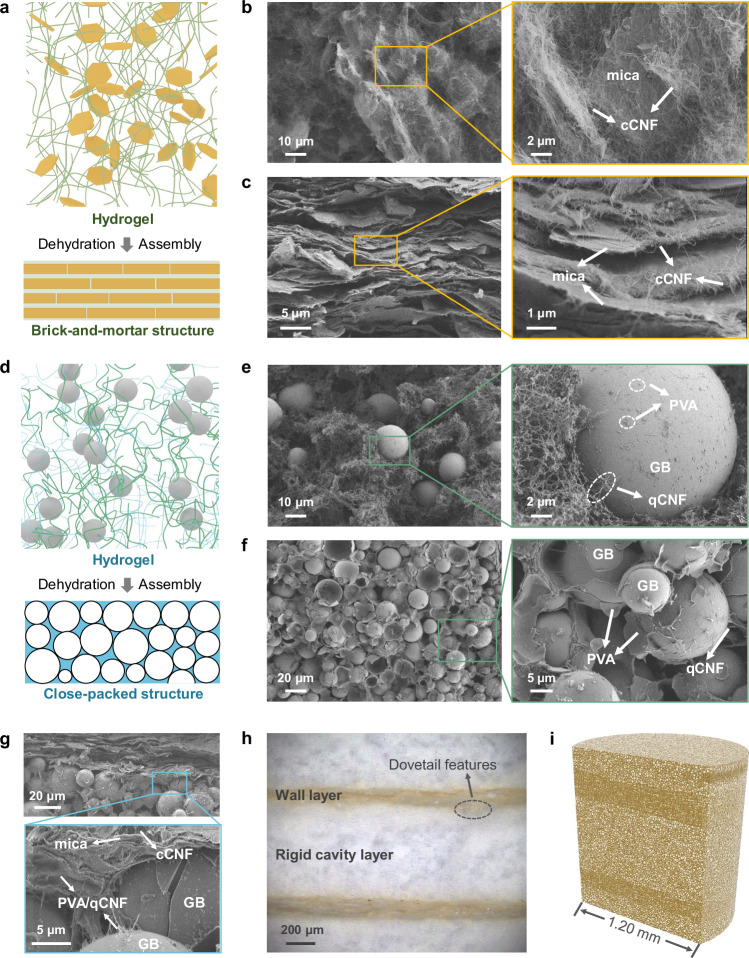

The mechanism of ordered assembly and arrangement

We further analyzed the transformation of hydrogels to final structural materials with a rigid cavity-wall structure. In the wall layer hydrogel, the crosslinked cCNF formed a 3D nanonetwork, while the amino mica was uniformly dispersed in this nanonetwork (Fig. 2a, b). We directly pressed the hydrogel to reduce its thickness and kept its in-plane size unchanged for dehydration. During this densification process, the 2D mica building blocks tended to have uniform orientations in a limited domain system and finally reached an even distribution in the 1D nanofiber network (Fig. 2a). In the brick-and-mortar structure, the amino mica stacked regularly and was tightly wrapped by the cCNF, forming a robust wall layer (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2. Synchronous assembly of various microstructures in the RCWSM.

a Schematic of the brick-and-mortar wall structure from the initial hydrogel to the dense state. Amino mica, yellow platelet; carboxylated CNF (cCNF), green curve. b SEM images of the irregular arrangement of mica platelets in the initial hydrogel. c SEM images of the brick-and-mortar wall in the RCWSM. d Schematic of the rigid cavity layer from the initial hydrogel to the dense state. GB gray sphere, PVA blue curve, qCNF green curve. e SEM images of the irregular arrangement of GB in the initial hydrogel. f SEM images of the rigid cavity layer within the RCWSM. g SEM images of the interface between the brick-and-mortar wall and the close-packed rigid cavity layer. h Polarizing microscope image of the cross-section of the RCWSM, which shows the obvious dovetail features at the interface between the two layers. i 3D reconstruction of the RCWSM derived from X-ray microtomography.

In the rigid cavity layer hydrogel, the qCNF and PVA constitute nanonetworks that support the uniform distribution of GB (Fig. 2d, e). Meanwhile, GB interacts with PVA via surface B–O–C bonds. During the dehydration and densification process, the distance between GB gradually decreases, and the material finally reaches a close-packed state (Fig. 2d). In the close-packed rigid micro hollow structure, the GB is tightly packed and protected by the PVA/qCNF mixture, forming a close-packed structure with walls approximately tangent to each other (Fig. 2f).

We characterized the interlayer interfacial bonding between the wall and rigid cavity layers at the hydrogel state. After external forces break the interlayer interface, GB in the rigid cavity layer adheres to the surface of the wall layer, and mica platelets in the wall layer adhere to the surface of the rigid cavity layer, indicating the robust combination of two different hydrogel layers (Supplementary Fig. 22). As for the junction of the wall and rigid cavity layers in the densified cuttlebone-inspired structural materials, there is no distinct gap between the two layers, further demonstrating the advantages of this one-step method for assembling predesigned hydrogels (Fig. 2g). GB in the rigid cavity layer can tightly bind mica in the wall layer by mediating PVA, qCNF, and cCNF through high-density hydrogen bonding, covalent bonding, and electrostatic interactions (Fig. 2g). A partially embedded dovetail-like structure is also observed at the interface between the two layers, which helps to increase damage tolerance (Fig. 2h). We achieved synchronous fabrication of highly ordered brick-and-mortar walls and close-packed rigid cavity layers through the hierarchical predesigned hydrogel integral synchronous assembly strategy mentioned above, obtaining the cuttlebone-inspired structural material (Supplementary Fig. 23). Through 3D reconstruction, a visible and robust cuttlebone-inspired rigid cavity-wall ordered microstructure can be observed from the surface to the inside (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Movie 1).

Mechanical properties and mechanism analysis

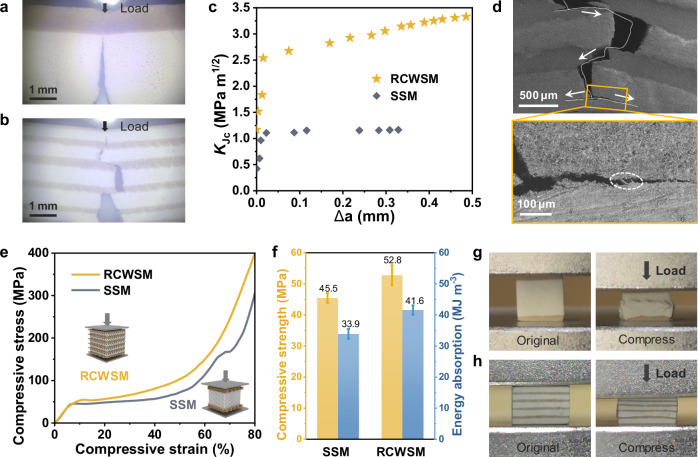

The predesigned hydrogel integral synchronous assembly strategy is universal and scalable for building complex bioinspired structures, through which a structural material with a rigid cavity-wall structure was fabricated. Moreover, sandwich structural material (SSM) with the same composition and content were also prepared via the same strategy to systematically study the influence of the integrated complex structure on the mechanical properties (Supplementary Fig. 24). We analyzed the fracture modes and failure behaviors of materials with two different structural designs through crack propagation behavior, static compression tests, and split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) tests.

After pre-cracking the sample, the materials with two structures exhibit different fracture behaviors under external forces. The initial crack directly penetrates through the rigid cavity in the sandwich structure (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Movie 2). For the material with a rigid cavity-wall structure, the initial crack is significantly hindered during the propagation process by the brick-and-mortar wall layers, and it has a tortuous crack propagation path (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Movie 3). We further analyzed the fracture toughness by the J-R curve approach, which can represent the increase in fracture toughness with crack extension and multiple extrinsic toughening mechanisms30,35. Due to the reinforcing effect of the brick-and-mortar wall layers, crack initiation can be effectively resisted in the rigid cavity-wall structure. Meanwhile, brick-and-mortar wall layers can effectively relieve locally high stress and achieve energy dissipation inside the material36,37, endowing the RCWSM with a maximum fracture toughness (KJc) greater than twice that of the SSM (Fig. 3c). Through multiple extrinsic toughening mechanisms, such as interfacial delamination, crack branching and bridging, catastrophic failure of the material in the case of internal defects can be avoided (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3. Fracture modes and failure behaviors of the RCWSM.

a, b Optical micrographs of sandwich structural material (SSM) (a) and RCWSM (b) taken from in situ single-edge notched bend tests. c Rising crack-extension resistance curves (evaluated by the steady-state fracture toughness KJc) of the SSM and RCWSM. d SEM images of the crack propagation behavior of the RCWSM in the single-edge notched bend test. The area magnified in the orange box is the crack branch, and the white dotted oval box marks the crack bridge. e Compressive stress-strain curves of the SSM and RCWSM. Insets: compressive stress direction of the RCWSM (left) and SSM (right). f Compressive strength and energy absorption of the SSM and RCWSM. Error bars show standard deviation with at least four repeats. g, h Photographs of the SSM (g) and RCWSM (h) before and after the compression test.

Figure 3e shows the compressive stress–stain curves of the RCWSM and SSM. Compared with SSM, RCWSM embodies a higher plateau stage under compressive stress. Differences in compressive stress-strain curve behavior result in the apparent superiority of the rigid cavity-wall structure in strength and energy absorption compared with the sandwich structure (Fig. 3f). Under compressive stress, the energy-absorbing part of the SSM is extruded and breaks at the edges without GB being sufficiently broken, resulting in premature failure of the material for full function (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Movie 4). The rigid cavity-wall structure can effectively confine rigid cavity layers by brick-and-mortar wall layers, enhancing the overall structural stability and promoting sufficient failure rather than extruding rigid cavity layers under compressive stress (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Movie 5). Thus, RCWSM achieves better strength and energy absorption than SSM with the same composition and content, demonstrating the advantage of cuttlebone-inspired overall structural integrity design (Supplementary Fig. 25).

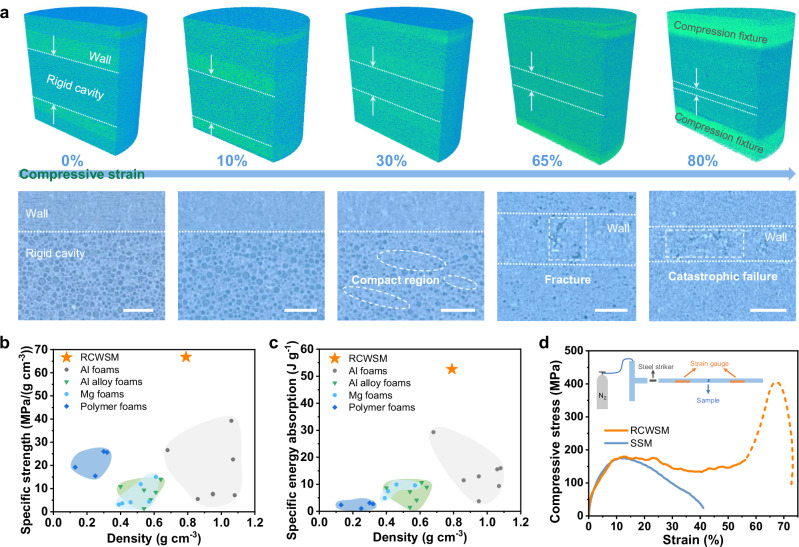

To visualize the energy absorption process of the RCWSM, we carried out compression testing coupled with in situ X-ray microtomography to interpret internal 3D microstructural changes (Fig. 4a). At the initial stage of compression testing (from 0 to 10% compressive strain), the rigid cavity-wall structure can maintain the overall stability of the internal structure, reflecting obvious structural rigidity. When reaching 30% compressive strain, a typical strain in the plateau stage, partial GB microspheres were crushed and densified in rigid cavity layers, during which a clearly compact region was observed. However, the brick-and-mortar wall layers remained intact. The brick-and-mortar wall layers appeared to fracture at 65% compressive strain and catastrophic fracture failure at 80% compressive strain. Moreover, nearly all the GB had already been broken catastrophically, and extensive densification had occurred in the original rigid cavity layers. These micro-structural behaviors further illustrate the effect of brick-and-mortar wall layers on reducing stress concentration, resulting in the superior mechanical properties of the rigid cavity-wall structure design.

Fig. 4. Mechanism and performance for energy absorption of the RCWSM.

a Failure process of the RCWSM under static compression coupled with in situ X-ray microtomography. 3D reconstructions and corresponding cross-sections of the RCWSM under various compressive strains are shown to demonstrate the details of the failure process. Scale bar: 100 μm. b, c Ashby diagrams of specific strength versus density (b) and specific energy absorption versus density (c) for the RCWSM compared with those of typical energy absorption materials40–49. Dark blue region: polymer foams; light blue region: Mg foams; green region: Al alloy foams; gray region: Al foams. d Compressive stress-strain curves of the SSM and RCWSM for the split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) test under a 6000 s−1 strain rate. The dashed line indicates that the integrity of the RCWSM has been destroyed, and the RCWSM has failed. Inset: schematic of the SHPB test.

The cuttlebone-inspired rigid cavity-wall design and multiple cross-scale organic/inorganic micro-nano architectures endow the RCWSM with excellent mechanical properties. With a low density of 0.79 g cm−3, the RCWSM reaches a high specific compressive strength [up to 66.8 MPa/(Mg m−3)] and high specific energy absorption (up to 52.6 J g−1), both of which are higher than those of other typical energy absorption materials with similar densities (Fig. 4b, c; Supplementary Fig. 26 and Supplementary Tables 2–3). Moreover, under the dynamic impact of the SHPB test, the rigid cavity-wall structure can also play a pivotal role in exerting the confinement function of brick-and-mortar wall layers, allowing the rigid cavity layers to fully absorb the energy. Compared with that of the SSM, the compressive stress-strain curve of the RCWSM exhibits a plateau stage, during which the RCWSM could absorb impact energy and realize adequate protection effectively (Fig. 4d). In addition, to demonstrate the durability in practical application, we further evaluated the mechanical properties of RCWSM under different environmental conditions. After 20 days of ultraviolet (UV) aging treatment, RCWSM can maintain similar compressive strength and energy absorption (Supplementary Fig. 27). Under cyclic load, the maximum stress of RCWSM has nearly no significant change after 200 times uniaxial cyclic loading and unloading (Supplementary Fig. 28).

Discussion

We engineered a hydrogel integral synchronous assembly strategy based on predesigned cross-scale organic/inorganic hydrogels to construct hierarchical cuttlebone-inspired rigid cavity-wall architectures. Through multiple interactions regulated by the predesigned hydrogels, organic and inorganic micro-nano building blocks are assembled in a highly ordered way to synchronously form a brick-and-mortar structure wall layer and a close-packed rigid micro hollow structure, as expected. The various interactions between organic and inorganic micro-nano building blocks are also responsible for the strong bonding and maintenance of structural integrity in the obtained RCWSM. Owing to the spatial confinement of brick-and-mortar structure wall layers, the RCWSM reaches excellent strength and energy absorption, higher than those of other typical energy absorption materials with similar densities. Moreover, multiple extrinsic toughening mechanisms can effectively prevent crack growth and thus avoid catastrophic failure. Our predesigned hydrogel fabrication strategy provides experience for the integrated preparation of multiple sophisticated bioinspired architectures, which have potential in various complex functional coupling applications, such as lightweight and energy-absorbing protective structural materials in intelligent cars and aerospace devices.

Methods

Materials

All of the chemical reagents and raw materials were commercially available.

Carboxylated cellulose nanofiber (cCNF) was prepared from bacterial cellulose (BC; Hainan Yide Food Co., Ltd.) by 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxy (TEMPO; Aladdin)-mediated oxidation38. BC was dispersed in 3000 mL of phosphate buffer, which consisted of KOH (0.08 mol, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd.) and KH2PO4 (0.17 mol, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd.), dissolving 3.5 mmol of TEMPO and NaClO2 (80%, 0.35 mol, Macklin). NaClO aqueous solution (35 mL, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd.) was diluted by adding it to 500 mL of phosphate buffer, and this mixed liquid was added to initiate the oxidation reaction. The reaction was carried out at 60 °C for about 3 days. The reaction mixture was sufficiently washed with deionized water (DIW). Finally, cCNF was received after being suspended in DIW and nanofibrillated by high-pressure homogenization.

Quaternized cellulose nanofiber (qCNF) was prepared from BC by the quaternization method39. BC was reacted with 5 wt% NaOH (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd.) and 3 wt% glycidyl trimethylammonium chloride (Shanghai Haohong Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.) aqueous solution under stirring at 65 °C for about 6 h. The reaction mixture was neutralized with glacial acetic acid and sufficiently washed with DIW. Finally, qCNF was obtained after being suspended in DIW and nanofibrillated by high-pressure homogenization.

Glass bubbles (GB, iM30K, 3 M Company) were alkali-treated with an alkaline etching solution obtained by diluting 1 mol L−1 NaOH aqueous solution with ethanol (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd.) five times to achieve sufficient activation of the surface for about 16 h. Then, the pretreated GB was filtered and washed once with ethanol and then washed three times with DIW.

Amino mica was pretreated by hydrolysis with N-[3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl]ethylenediamine. In a typical fabrication, 70 g of mica platelets (Chuzhou Wanjuan New Materials Co., Ltd.) was calcined at 800 °C for 2 h using a muffle furnace. Then, the heat-treated mica was dispersed in 500 mL of ethanol, N-[3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl]ethylenediamine (10 g, Aladdin), and about 5 mL of DIW was added, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h as a pretreatment. The amino mica dispersion was subsequently filtered and washed three times with ethanol.

Fabrication of cuttlebone-inspired rigid cavity-wall structural material (RCWSM)

RCWSM was fabricated from different initial hydrogels to construct the corresponding microstructures. The brick-and-mortar wall layer was fabricated by assembling amino-modified mica platelets and cCNF through Ca2+ crosslinking27. In a typical fabrication, 10 g of amino mica dispersion (about 25 wt%) was evenly mixed with 250 g of cCNF (1 wt%), which was crosslinked by spraying about 200 mL 1 mol L−1 CaCl2 (Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd.) solution evenly on the mixed slurry of amino mica and cCNF, and then washed three times with DIW. Formed initial hydrogel was divided evenly into 6 parts. For the rigid cavity layer, 4 g of GB after surface alkali-activation treatment were evenly mixed in a 100 g aqueous dispersion with 3 wt% PVA (1750 ± 50, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd.) and 1 wt% qCNF. After stable molding for about 12 h, the mixture was formed and evenly divided into 5 parts. The above-mentioned initial hydrogels were stacked in turn and pressed at 90 °C under 20 MPa of pressure to achieve integral assembly.

Fabrication of sandwich structural material (SSM)

SSM was fabricated by in-turn stacking of an amino-modified mica/cCNF composite hydrogel and a GB/PVA/qCNF composite hydrogel as a sandwich-like structure. The contents, mass, and fabrication process of the SSM were the same as those of the RCWSM. The initial hydrogel of the brick-and-mortar wall was divided equally in half as the external layers of the SSM before integral assembly.

Fabrication of rigid cavity layers with various content ratios

GB composites with various content ratios were prepared for the optimum design of effective rigid microcavities. Composites with different GB/PVA/qCNF mass content ratios were prepared. The mass ratios of each component are shown in Supplementary Table 1. All of the initial gels were stably molded at 90 °C under 20 MPa of forming pressure.

Characterizations

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images and scanning electron microscopy/energy-dispersive X‐ray spectrometry (SEM/EDS) were taken with a GeminiSEM 450 Schottky field emission scanning electron microscope at acceleration voltages ranging from 1 to 5 kV. All the samples were gold-sputtered for 45 s at a constant current of 30 mA before observation. In particular, for the SEM sample preparation of various initial hydrogels, the initial hydrogel was dried with supercritical CO2 after the original solvent was sufficiently exchanged with ethanol in a critical point dryer (Leica EM CPD300).

11B solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) cross-polarization magic angle spinning spectra were obtained by a WB Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometer (Bruker AVANCE NEO 600 WB, 600 MHz).

Zeta potential curves were obtained by a Malvern Zetasizer at room temperature. All of the samples for the zeta potential test were at a concentration of ~0.05 wt% at pH = 7.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images were obtained using a Bruker Dimension Icon. The samples were dispersed in DIW at a concentration of ~0.05 wt% and then dropped on the mica substrate to dry naturally.

For Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, the spectra of the cCNF and qCNF films were obtained by a Bruker Vector-22 FT-IR spectrometer in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode at room temperature.

A microscope image of the RCWSM was obtained by an OLYMPUS BX53M optical microscope.

The particle size distribution curve was obtained by a laser particle analyzer (Malvern Mastersizer 2000).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed with a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha instrument using a monochromatic Al Kα radiation source. Deconvolution of the XPS spectra was performed with XPS Peak software.

Rheological test

Rheological property analysis was performed with a rotating rheometer (TA HR20). The storage modulus, loss modulus and viscosity of all the samples were tested for 40,000 s at room temperature with a 60 mm parallel plate clamp. For the rheological property test, the water content of the sample was about 93%. The mass content ratio of the GB/PVA/qCNF sample was GB:PVA:qCNF = 4:3:1; that of the GB/PVA sample was GB:PVA = 1:1; and that of the GB/qCNF sample was GB: qCNF = 1:1. All of the samples were loaded onto the sample stage, and the tests were started immediately while the samples were mixed evenly.

Single-edge notched bend (SENB) test

For the SENB tests, the RCWSM and SSM samples were notched using a diamond saw (~300 μm), and then the notch was sharpened by slightly sliding a razor blade repeatedly. The loading rate was 10 μm min−1 for the SENB samples under a polarizing microscope (Olympus BX53M) to study their crack propagation behavior.

Compression test

The compression test was performed with a Shimadzu AGX-V universal testing machine at a loading rate of 1 mm min−1. All cuboid samples (about 5 mm × 5 mm × 4 mm) were tested at room temperature via compressive tests. The compression process was recorded by the movie.

Lap-shear test

The lap-shear test was performed with Instron 5565-A universal testing machine at a loading rate of 5 mm min−1. Two different hydrogels were combined and formed under ~20 MPa. All rectangular samples (with the bond area of about 5 mm × 5 mm) were tested at room temperature via lap-shear test.

180° peel test

The 180° peel test was performed with Instron 5565-A universal testing machine at a loading rate of 5 mm min−1. Two different hydrogels were combined and formed under ~20 MPa. All rectangular samples (with the width of about 8.5 mm) were tested at room temperature via 180° peel test.

In situ X-ray microtomography

X-ray microtomography was conducted during compression testing of the RCWSM on a Zeiss Xradia 520. This in situ compression-X-ray microtomography characterization can reveal the changes in the three-dimensional (3D) microstructure of the RCWSM non-destructively during compression (representative status: compressive strains of 0%, 10%, 30%, 65%, and 80%). The raw X-ray microtomography data were reconstructed using Dragonfly software by assembling the static images in sequence.

Split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) test

For the SHPB tests, the RCWSM and SSM samples were in cuboid shape (6 × 6 mm2 in sectional area and about 4 mm in height), and the compression strain rate was about 6000 s−1.

UV aging treatment

The RCWSM samples (about 5 mm × 5 mm × 4 mm) were treated in an accelerated aging tester (FBS-UV340 L) under UV irradiation intensity of 2.00 W m−2 for 20 days. The test temperature and relative humidity were 30 °C and 50%.

Cyclic compression test

The cyclic compression test was performed with a Shimadzu AGX-V universal testing machine at a loading rate of 0.2 mm min−1. All cuboid samples (about 5 mm × 5 mm × 4 mm) were tested at room temperature via cyclic compressive tests.

Calculations

The density of the cuboid samples was calculated as the mass divided by the volume.

The energy absorption of the cuboid samples was calculated by the integrated area under the compressive stress-strain curve before densification, which was about 60% of the strain determined by the actual compressive testing movie of the corresponding samples.

The specific energy absorption of the cuboid samples was calculated by dividing the energy absorption by the density of the corresponding samples.

The fracture toughness of the RCWSM and SSM samples was calculated via the SENB test. The fracture toughness for crack initiation (KIc) was calculated by

| 1 |

where PIc is the load in the SENB test, S is the span, B is the thickness of the SENB specimen, W is the width, and a is the length of the precrack. The function is given by

| 2 |

The maximum fracture toughness (KJc) was determined by

| 3 |

where Jel represents the elastic component of the J-integral, Jpl is the plastic component of the J-integral, and E’ is given by

| 4 |

where E represents the elastic modulus and ν is the Poisson’s ratio.

The elastic component Jel was based on linear elastic fracture mechanics.

| 5 |

The plastic component Jpl was calculated by

| 6 |

where Apl is the area of the plastic region under the load-displacement curve.

The crack length, Δa, was calculated using the following equation:

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

where an, Cn, un, and fn are the crack length, compliance, displacement, and load at each point after crack initiation, respectively.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding support from the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grants XDB0450402, Q.-F.G.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA0715700, S.-H.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 22293044, S.-H.Y., 22105194, Q.-F.G., 92163130, Q.-F.G., and 22405264, H.-B.Y.), the Major Basic Research Project of Anhui Province (2023z04020009, S.-H.Y.), Anhui Province Outstanding Youth Science Fund (2408085J011, Q.-F.G.), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (GZC20241637, H.-B.Y.), and the New Cornerstone Investigator Program (S.-H.Y.). This work was partially carried out at the USTC Center for Micro- and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication. The authors thank New Materials and Intelligent Manufacturing Joint Laboratory. The authors thank L.-J. Wang for in situ X-ray microtomography. The authors thank M. Li, S.-Q. Fu, and H.-M. Zhou from the Instruments Center for Physical Science, University of Science and Technology of China, for help with the scanning electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy characterizations.

Author contributions

H.-B.Y., Q.-F.G., and S.-H.Y. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. S.-H.Y. and Q.-F.G. supervised the project. H.-B.Y., Y.-X.L., X.Y., Z.-X.L., W.-B.S., and W.-P.Z. carried out the experiments, characterization, and analysis. Y.-X. L. contributed to the 3D illustrations. H.-B.Y., Y.-X.L., Q.-F.G., and S.-H.Y. wrote the paper, and all the authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Wei Zhang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file. All the data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided in this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Huai-Bin Yang, Yi-Xing Lu, Xin Yue.

Contributor Information

Qing-Fang Guan, Email: guanqf@ustc.edu.cn.

Shu-Hong Yu, Email: shyu@ustc.edu.cn, Email: yush@sustech.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-55344-1.

References

- 1.Wegst, U. G. K., Bai, H., Saiz, E., Tomsia, A. P. & Ritchie, R. O. Bioinspired structural materials. Nat. Mater.14, 23–36 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng, X. S. et al. Deformable hard tissue with high fatigue resistance in the hinge of bivalve Cristaria plicata. Science380, 1252–1257 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang, Y. et al. Ginkgo seed shell provides a unique model for bioinspired design. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA119, e2211458119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao, H. et al. Multiscale engineered artificial tooth enamel. Science375, 551–556 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao, H. B., Ge, J., Mao, L. B., Yan, Y. X. & Yu, S. H. 25th Anniversary article: artificial carbonate nanocrystals and layered structural nanocomposites inspired by nacre: Synthesis, fabrication and applications. Adv. Mater.26, 163–188 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan, S. et al. Ultrastrong MXene films via the synergy of intercalating small flakes and interfacial bridging. Nat. Commun.13, 7340 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao, C. et al. Total morphosynthesis of biomimetic prismatic-type CaCO3 thin films. Nat. Commun.8, 1398 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, C. et al. Structure–property–function relationships of natural and engineered wood. Nat. Rev. Mater.5, 642–666 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu, Z. L. et al. Emerging bioinspired artificial woods. Adv. Mater.33, e2001086 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu, G. X., Takaffoli, M. & Buehler, M. J. Hierarchically enhanced impact resistance of bioinspired composites. Adv. Mater.29, 1700060 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imrie, P. & Jin, J. Multimaterial Hydrogel 3D Printing. Macromol. Mater. Eng.309, 2300272 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou, X. et al. Advances in field‐assisted 3D printing of bio‐inspired composites: from bioprototyping to manufacturing. Macromol. Biosci.22, 2100332 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu, Z., Wu, M., Gao, W. & Bai, H. A sustainable single-component “Silk nacre”. Sci. Adv.8, eabo0946 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han, Z. M. et al. An all‐natural wood‐inspired aerogel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202211099 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mao, L. B. et al. Synthetic nacre by predesigned matrix-directed mineralization. Science354, 107–110 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan, Q. F. et al. Lightweight, tough, and sustainable cellulose nanofiber-derived bulk structural materials with low thermal expansion coefficient. Sci. Adv.6, eaaz1114 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, K. et al. Graphene oxide bulk material reinforced by heterophase platelets with multiscale interface crosslinking. Nat. Mater.21, 1121–1129 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang, H. B. et al. Simultaneously strengthening and toughening all‐natural structural materials via 3D nanofiber network interfacial design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202408458 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Tang, Z., Kotov, N. A., Magonov, S. & Ozturk, B. Nanostructured artificial nacre. Nat. Mater.2, 413–418 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan, S. et al. High-strength scalable graphene sheets by freezing stretch-induced alignment. Nat. Mater.20, 624–631 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao, C. et al. Layered nanocomposites by shear-flow-induced alignment of nanosheets. Nature580, 210–215 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang, H. B. et al. An all-natural fire-resistant bioinspired cellulose-based structural material by external force-induced assembly. Mater. Today Nano23, 100342 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magwene, P. M. & Socha, J. J. Biomechanics of turtle shells: how whole shells fail in compression. J. Exp. Zool. Part A319, 86–98 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seki, Y., Kad, B., Benson, D. & Meyers, M. A. The toucan beak: structure and mechanical response. Mater. Sci. Eng. C26, 1412–1420 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novitskaya, E. et al. Reinforcements in avian wing bones: experiments, analysis, and modeling. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater.76, 85–96 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang, T. et al. Mechanical design of the highly porous cuttlebone: a bioceramic hard buoyancy tank for cuttlefish. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA117, 23450–23459 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mao, A., Zhao, N., Liang, Y. & Bai, H. Mechanically efficient cellular materials inspired by cuttlebone. Adv. Mater.33, 2007348 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui, C., Chen, L., Feng, S., Cui, X. & Lu, J. Novel cuttlebone-inspired hierarchical bionic structure enabled high energy absorption. Thin Wall Struct.186, 110693 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen, L., Cui, C., Cui, X. & Lu, J. Cuttlebone-inspired honeycomb structure realizing good out-of-plane compressive performances validated by DLP additive manufacturing. Thin Wall Struct.198, 111768 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan, Q. F., Yang, H. B., Han, Z. M., Ling, Z. C. & Yu, S. H. An all-natural bioinspired structural material for plastic replacement. Nat. Commun.11, 5401 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wan, S. et al. High-strength scalable MXene films through bridging-induced densification. Science374, 96–99 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An, Z., Compton, O. C., Putz, K. W., Brinson, L. C. & Nguyen, S. T. Bio-inspired borate cross-linking in ultra-stiff graphene oxide thin films. Adv. Mater.23, 3842–3846 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han, J. L. et al. Borate inorganic cross-linked durable graphene oxide membrane preparation and membrane fouling control. Environ. Sci. Technol.53, 1501–1508 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, S., Jing, X., Wang, Y. & Si, J. High char yield of aryl boron-containing phenolic resins: the effect of phenylboronic acid on the thermal stability and carbonization of phenolic resins. Polym. Degrad. Stabil.99, 1–11 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouville, F. et al. Strong, tough and stiff bioinspired ceramics from brittle constituents. Nat. Mater.13, 508–514 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao, H. & Guo, L. Nacre-inspired structural composites: performance-enhancement strategy and perspective. Adv. Mater.29, 1702903 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, H. et al. Tough and conductive nacre‐inspired MXene/epoxy layered bulk nanocomposites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202216874 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guan, Q. F. et al. Plant cellulose nanofiber-derived structural material with high-density reversible interaction networks for plastic substitute. Nano Lett.21, 8999–9004 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pei, A., Butchosa, N., Berglund, L. A. & Zhou, Q. Surface quaternized cellulose nanofibrils with high water absorbency and adsorption capacity for anionic dyes. Soft Matter9, 2047–2055 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, C., Li, C. & Wang, Y. Compressive behavior and energy absorption capacity of unconstrained and constrained open-cell aluminum foams. Adv. Compos. Lett.29, 1–4 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Novak, N. et al. Compressive behaviour of closed-cell aluminium foam at different strain rates. Materials12, 4108 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soni, B. & Biswas, S. Effects of cell parameters at low strain rates on the mechanical properties of metallic foams of Al and 7075-T6 alloy processed by pressurized infiltration casting method. J. Mater. Res.33, 3418–3429 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hassani, A., Habibolahzadeh, A. & Bafti, H. Production of graded aluminum foams via powder space holder technique. Mater. Des.40, 510–515 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang, W., Zheng, X., Zhu, C. & Long, W. Effect of Ti content on the cell structure and compressive and energy absorption properties of Al3Ti/Al6061 foam composite. J. Alloy. Compd.957, 170321 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xia, X., Feng, H., Zhang, X. & Zhao, W. The compressive properties of closed-cell aluminum foams with different Mn additions. Mater. Des.51, 797–802 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang, X., Xie, M., Li, W., Sha, J. & Zhao, N. Controllable design of structural and mechanical behaviors of Al–Si foams by powder metallurgy foaming. Adv. Eng. Mater.24, 2200125 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osorio-Hernández, J. O. et al. Manufacturing of open-cell Mg foams by replication process and mechanical properties. Mater. Des.64, 136–141 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saha, M. C. et al. Effect of density, microstructure, and strain rate on compression behavior of polymeric foams. Mat. Sci. Eng. A406, 328–336 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu, G. Q., Hao, H., Wang, F. Y. & Zhang, X. G. Preparation of closed-cell Mg foams using SiO2-coated CaCO3 as blowing agent in atmosphere. Trans. Nonferr. Metal. Soc.23, 1832–1837 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file. All the data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided in this paper.