Abstract

Bacteria have been found in tumors for over 100 years, but the irreproducibility of experiments on bacteria, the limitations of science and technology, and the contamination of the host environment have severely hampered most research into the role of bacteria in carcinogenesis and cancer treatment. With the development of molecular tools and techniques (e.g., macrogenomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, and macrotranscriptomics), the complex relationships between hosts and different microorganisms are gradually being deciphered. In the past, attention has been focused on the impact of the gut microbiota, the site where the body’s microbes gather most, on tumors. However, little is known about the role of microbes from other sites, particularly the intratumor microbiota, in cancer. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have identified the presence of symbiotic microbiota within a large number of tumors, bringing the intratumor microbiota into the limelight. In this review, we aim to provide a better understanding of the role of the intratumor microbiota in cancer, to provide direction for future experimental and translational research, and to offer new approaches to the treatment of cancer and the improvement of patient prognosis.

Keywords: Intratumor microbiota, Tumor-resident intracellular microbiota, Microbiome, Tumor, Immunotherapy

Introduction

The microbiota is the collection of microorganisms (eubacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses and protists) that inhabit the body of an individual at a given time; the human microbiota resides mainly in the gut, but also in most parts of the body (e.g., skin, vagina and mouth, and even the nose, conjunctiva, pharynx, and urethra) (Cho and Blaser 2012; Ursell et al. 2012). These microbial colonies that make up the human microbiota profoundly influence many important physiological functions in humans, such as nutritional metabolism, xenobiotic substances, drug metabolism, immune regulation (Ezenwa et al. 2012; Turnbaugh et al. 2006), and can even influence tumorigenesis, development, and therapeutic response (Jobin 2018). As these bacterial communities vary between different physical habitats, a complex interaction between host and microorganism is established (Human microbiome Project Consortium 2012), making it a potential determinant of disease development, including cancer. According to statistics, nearly 20% of cancers worldwide are linked to the human microbiota (de Martel et al. 2012). Since the opening of the Human Microbiome Project, the understanding of the microbiota has gradually improved, and the gut microbiota has received excellent feedback for cancers of the gastrointestinal tract and other distal sites of tumors (Dzutsev et al. 2017; Garrett 2015; Shalapour and Karin 2020). They exert immunomodulatory and anti-tumor effects on distal or proximal tumor tissue mainly through indirect pathways (metabolites and immune pathways), while dysbiosis of gut microbes can induce the release of toxic metabolites and exhibit pro-tumor effects in humans, especially in colorectal cancer, which is closely related to the gut microbiota, and is most extensively studied (Garrett 2015; Xavier et al. 2020).

However, in recent years, there have been emerging lines of evidence that microbes are also integral components of the tumor tissue itself in much broader cancer types beyond colorectal cancer, such as pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, and others, which were originally thought to be sterile (Flemer et al. 2017; Jin et al. 2019; Nejman et al. 2020; Pushalkar et al. 2018; Riquelme et al. 2019; Urbaniak et al. 2016). Further mechanistic studies have revealed that these intratumor microbiota form an important part of the tumor microenvironment, influencing tumor development and response to chemotherapy and immunotherapy to a certain extent. In a recent study, researchers analyzed the intratumor microbiomes of 1526 tumors and their adjacent normal tissues from seven cancer types: breast, lung, ovarian, melanoma, bone, and brain tumors, and found that different types of human tumors have their own unique composition of bacterial populations, mainly within cancer cells and immune cells. In each tumor type, changes in the intratumor microbiota can be detected and inferred to be associated with clinicopathological features (Nejman et al. 2020). In addition, Gellar et al. found that intratumor microbiota can reduce the efficacy of the chemotherapeutic agent gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer (Geller et al. 2017), suggesting that intratumor microbiota also play an important role in therapeutic behaviors such as chemotherapy. It is from this perspective that we discuss the role of intratumoral microbes in tumor development and their response to cancer therapy, as well as how to target the intratumoral microbiota to achieve therapeutic goals.

Sources of intratumor microbiota

The human microbiota lives extensively in and on the human body, including in solid tumors where it can be detected, but no definitive conclusions have emerged about the origin of the microbiota within tumors. Some studies suggest that the intratumor microbiota emerges after tumor formation as a result of bacterial migration due to the various characteristics of solid tumors. McAllister et al. found that approximately 20% of microbiota in pancreatic tumors were of intestinal origin through analysis of surgical specimens (McAllister et al. 2019). Another researcher performed deep sequencing of PCR-amplified bacterial 16S rDNA in 65 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC) and found that most of the populations belonged to the order Gammaproteobacteria, including members of the Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas (Geller et al. 2017), and these species were most common in the duodenum (Nistal et al. 2012; Ou et al. 2009), where the pancreatic duct opens to the duodenum, suggesting that retrograde migration of bacteria from the duodenum to the pancreas is the source of PDAD-associated bacteria, in agreement with the findings of McAllister et al. Mechanistically, it was previously thought to be primarily due to the hypoxic nature of most solid tumors, which result in lower oxygen levels compared to normal tissue, providing a unique growth environment for anaerobic and partly anaerobic bacteria (Wei et al. 2007). Second, the presence of bacterial nutrients such as aspartic acid, serine, ribose, or galactose in the tumor necrosis zone favors the survival and growth of specific species of bacteria. At the same time, the necrotic area of the tumor releases chemical signals that attract and promote the extravasation of bacteria into the tumor, leading to the aggregation of bacteria after tumor formation (Baban et al. 2010). For example, Gram-positive anaerobic bacteria, Clostridium perfringens, can colonize areas of tumor necrosis and hypoxia, while Gram-negative parthenogenic anaerobic bacteria, Salmonella, can invasively enter and colonize tumor tissue from outside it. As tumors develop, they promote the formation of new blood vessels, which, in the process, leads to the formation of a highly leaky vascular system around the tumor cells, where circulating bacteria can easily enter and colonize the tumor locally (Baban et al. 2010). Finally, cancer cells evade surveillance by the immune system through various mechanisms, and colonizing bacteria can take advantage of this tumor immune privilege to proliferate easily without any interference from the host immune system (Bermudes et al. 2000; Sznol et al. 2000).

Many studies now indicate, however, that the microbiota may be present within the tumor at an early stage of formation and may be involved in the tumor formation process. In an experiment by Aikun Fu et al., they used qPCR and 16S sequencing to characterize the intratumor flora of the MMTV-PyMT (mouse mammary tumor virus polyoma intermediate tumor antigen) spontaneous mouse mammary tumor (BT) model, which was found to be enriched in Staphylococcus, Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, and Streptococcus (Nejman et al. 2020; Thompson et al. 2017; Urbaniak et al. 2014, 2016), similar to those found in human breast cancer (Fu et al. 2022). On this basis, Aikun Fu et al. analyzed the differences in normal and tumor tissues of mice and found a decrease in anaerobic bacteria and a significant increase in facultative anaerobes in BT tissues, suggesting the presence of a dynamic oxygen microenvironment in spontaneous mammary tumors formed by PyMT. These results suggest that the intratumoral microbiota is more likely to be an intrinsic and integral part of the tumor tissue than an incidental occurrence due to pathogenic infection. This possibility was also supported by Nejman et al. in their comprehensive intratumoral microbiota analysis of various human cancer types (Nejman et al. 2020), but it still needs to be supported by more experimental data.

Intratumor bacteria are mostly intracecellular and are present in both cancer and immune cells

The presence of intratumoral microbiota has been confirmed in at least 33 major cancer types to date (Kalaora et al. 2021; Nejman et al. 2020; Poore et al. 2020; Riquelme et al. 2019), as well as imaging data that show the colocalization of panbacterial markers with immune and epithelial cell targets, suggesting that the intratumoral microbiota can be intracellular (Bullman et al. 2017; Kalaora et al. 2021; Nejman et al. 2020). For example, Nejman et al. showed that intratumor bacteria in human cancers are predominantly present in the cytoplasm of both immune cells and tumor cells (Nejman et al. 2020). Aikun Fu et al. reconfirmed the presence of punctate bacteria in the perinuclear region of cancer cells using 16S fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), lipopolysaccharides (LPS) staining (for Gram-negative bacteria), and lipoteichoic acid (LTA) staining (for Gram-positive bacteria) (Fu et al. 2022). The results of high-resolution electron microscopy (EM) analysis also support the idea that most bacterial-like structures appear in the cytoplasm rather than in the extracellular space (Fu et al. 2022). And in a recent study, Bullman et al. found that bacteria can reside in highly immunosuppressed microniches in the CD45 + immune compartment of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) (Galeano Niño et al. 2022). Meanwhile, Bullman et al. infected three invasive bacterial species—Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum), Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia—with the human colon cancer cell line HCT116 at 100:1 and 500:1 multiplex infection. Confocal imaging indicated the presence of intracellular bacteria in cancer cells after bacterial co-culture (Galeano Niño et al. 2022), this all indicates that most of the intratumor micobita is present within the tumor cells. Notably, however, in Aikun Fu's experiments quantifying the relative number of cells inside and outside the tumor, no significant enrichment in the number of extracellular bacteria in PyMT tumors was found. However, in mouse models, immunodeficient NPSG mice tend to have more extracellular bacterial components compared to immunocompetent Fvb mice, suggesting involvement of the immune system (Fu et al. 2022). Nevertheless, the abundance of extra-tumor cell microbiota is much lower compared to the intracellular microbiota of tumors, and further studies are still needed to understand their functional spectrum and potency.

Mechanism

Intratumor microbiota effects on the TME

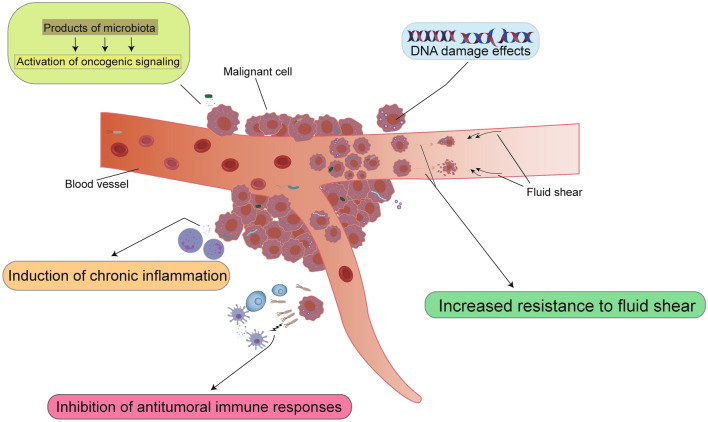

It is well known that cancer is a multifactorial, multi-organ, cumulative, and comprehensive disease involving multiple factors. The tumor microenvironment (TME) is widely recognized to be associated with tumorigenesis. Non-malignant cells in the tumor microenvironment are able to play a key role in all stages of tumorigenesis by stimulating and promoting uncontrolled cellular value addition. Among them, the metabolites of tumor cells play a crucial role in the tumor microenvironment as essential products affecting tumor cell growth, and an important source of metabolites is the microbiota. Studies have shown that the metabolites and molecules produced by these microbiota colonizing the surface of human epithelial cells can promote tumor growth and development through many effects on TME (Hamada et al. 2018; Le Noci et al. 2018; Mima et al. 2015; Parhi et al. 2020; Pushalkar et al. 2018; Riquelme et al. 2019; Roberti et al. 2020): (1) affecting genomic stability; (2) upregulation or activation of oncogenic signaling pathways; (3) induction of chronic inflammation and other modalities; and (4) inhibition of antitumoral immune responses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms associated between microorganisms and tumor formation. According to the currently known relevant data, there are five mechanisms by which intratumor microorganisms influence cancer development:causes activation of oncogenic signaling pathways (top left), causes genomic instability and DNA damage (top right), induces chronic inflammation (bottom left 1), inhibits tumor cell killing by NK cells and T cells (bottom left 2), and enhances resistance to fluid shear in the circulatory system, which promotes the survival of host tumor cells (bottom right)

Affecting genomic stability

The acquisition of genomic instability is one of the important features of tumorigenesis and development. When tumor cells suffer DNA damage that is not repaired in time, the cells acquire a “mutator phenotype” that increases the frequency of mutations and allows precancerous cells to evolve into aggressive cancer cells, thereby promoting tumorigenesis and progression (Raptis and Bapat 2006). Many microorganisms have evolved to produce compounds that cause damage to DNA, cell cycle arrest, and genetic instability, and these compounds can affect genomic homeostasis through different pathways. For example, cytotoxic swelling toxins (CDT) produced by a variety of Gram-negative bacteria can cause nuclear fragmentation and chromatin destruction and promote DNA fragmentation in cells exposed to purified soluble toxins, thereby causing genomic instability (Elwell and Dreyfus 2000; Hassane et al. 2001; Lara-Tejero and Galán, 2000). Bacteroides fragilis toxin (BFT) in Enterotoxigenic Bacillus fragilis (ETBF) causes carcinogenesis through genomic instability by inducing epithelial cell host oxidase induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) to activate DNA damage responses (Pflug et al. 2016; Sears 2009). Colibactin genotoxin produced by pks + E. Coli induces double-strand breaks (DSBs), specific mutational features, and other forms of DNA damage, resulting in a unique mutational signature (Nougayrède et al. 2006; Putze et al. 2009). And this mutational signature is found in both in vitro and in vivo experiments in colorectal cancer (Garrett 2015; Guerra et al. 2011).

Upregulation or activation of oncogenic signaling pathways

Intratumor microbiota and their products can participate in host oncogenic signaling pathways, and promote tumorigenesis and progression by upregulating or activating these signaling pathways. For example, the Cag pathogenicity island (Cag-PAI) plays a key role in the pathogenesis of H. pylori-induced gastric cancer. Phosphorylated CagA causes dysregulation of epithelial structure and integrity through its effect on host cell signaling, such as the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, by interacting with SHP-2, Grb2, Crk/Crk-L, Csk, Met, and ZO-1 (Amieva et al. 2003; Churin et al. 2003; Higashi et al. 2002; Mimuro et al. 2002; Suzuki et al. 2005; Tsutsumi et al. 2003). The CRPIA motif in nonphosphorylated CagA was involved in interacting with activated Met, the hepatocyte growth factor receptor, leading to the sustained activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling in response to Hp infection. This in turn led to the activation of β-catenin and NF-κB signaling, which promote proliferation and inflammation, respectively (Suzuki et al. 2009). Furthermore, the intratumoral microbiota and its products can activate or regulate the WNT/-catenin pathway, promoting tumor progression in gastric and colorectal cancers (Kostic et al. 2012, 2013; Sears 2009).It is well understood that abnormal activation of this pathway causes β-catenin accumulation in the nucleus, promotes the transcription of many oncogenes, such as c-Myc and G1/S-specific cyclin-D1 (CyclinD-1), and promotes tumor progression (Shang et al. 2017). In esophageal cancer, Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) was able to reduce the level of the tumor suppressor P53 by activating JAK2 and GSK1β pathways to promote tumorigenesis (Gao et al. 2016; Hajishengallis and Lamont 2014; Wang et al. 2014). In a recent study, Bullman et al. found by INVADEseq (invasion–adhesion-directed expression sequencing) that bacteria-infected cells exhibited a significant upregulation of signaling pathways that are involved in the response to bacterial infection, such as the TNF pathway and pathways related to inflammation and hypoxia, as well as cancer cell progression via the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the p53 signaling pathway.

Induction of chronic inflammation and other modalities

Tumors are closely associated with chronic inflammation, and tumor-promoting inflammation is thought to be one of the main features of carcinogenesis (Kawanishi et al. 2017). Statistics show that nearly 25% of human cancers are associated with chronic inflammation caused by recurrent infections, autoimmune diseases, etc. (Kundu and Surh 2008). The intratumor microbiota promotes tumorigenesis through a coordinated pro-inflammatory response by inflammatory cells and mediators (including cytokines, chemokines and prostaglandins) in the tumor microenvironment (Mantovani et al. 2008). These mechanisms are associated with inflammation and immune responses activated through NF-κB transcription, including DNA-damaging ROS produced by innate immune cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, and precancerous cell mutations that accumulate due to overproliferation. In lung cancer, Jin et al. demonstrated through experiments in an oncogenic mouse autologous lung cancer model that local microbiota can trigger inflammatory interactions between alveolar macrophages and IL-17-producing lung resident γδ T cells, thereby promoting tumor progression. In addition, a significant increase in the abundance of Fusobacterium (F.) nucleatum was found in colorectal cancer. The introduction of F. nucleatum into a mouse intestinal tumorigenic model revealed that F. nucleatum promotes chronic inflammatory responses through the NF-κB pathway, creating a tumor microenvironment and accelerating the development of tumors (Rajagopala et al. 2017). Likewise, F. nucleatum are responsible for recruiting myeloid cells to induce an inflammatory response through JAK–STAT signaling, promoting T cell exclusion and tumor growth by secreting specific interleukins and chemokines into the surrounding environment (Galeano Niño et al. 2022). In gastric cancer, H. pylori induces neutrophil and macrophage recruitment, which in turn produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen species (RONS) (Suzuki et al. 1994). And these ROS/RONS mediated by inflammation can cause DNA base damage, leading to single-strand breaks (SSBs) and enhanced oncogene expression (Cerutti 1994; Feig et al. 1994) and induce NF-κB inflammatory pathways that can trigger double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) to promote tumor development (Kidane 2018). The inflammatory environment can in turn promote bacterial growth, e.g., the pro-inflammatory response induced by H. pylori includes interleukin 1β (IL-1)and tumor necrosis factor α(TNF-α), which inhibit acid secretion from gastric lining cells and promote secondary bacterial overgrowth (Peek and Crabtree 2006).

Inhibition of antitumoral immune responses

The effects of microbiota on the regulation of the immune system and the development of tumors have been widely reported (Belkaid and Hand 2014; Belkaid and Naik 2013; Dzutsev et al. 2017). In a symbiotic state, the microbiota is in dynamic equilibrium with its host, exerting local and remote influences. Hosts tolerate the presence of commensal microbes and respond modestly to potentially harmful pathogens, preventing tumor development (Shapira et al. 2013). However, a variety of internal and external influences may disturb this balance, resulting in a dysbiosis of the microbiota. Imbalances in the composition of the local microbiota may affect the host's immune response and promote chronic inflammation, thereby promoting tumorigenesis and progression (Marteau 2009; Shapira et al. 2013).

Intratumor microbes often create tolerogenic programming through pattern recognition receptor (PRR) ligation with lower proportions of TILs, including CD8 + T cells, and occasionally more CD4 + CD25 + FoxP3 + Tregs, as observed in colorectal, pancreatic, breast, and lung cancers (Hamada et al. 2018; Jin et al. 2019; Le Noci et al. 2018; Mima et al. 2015; Parhi et al. 2020; Pushalkar et al. 2018; Roberti et al. 2020).Some studies have shown that certain bacteria can inhibit local natural killer (NK) and T cell-mediated killing of tumor cells to help them evade immune surveillance. For example, the FAP2 protein of F. nucleatum prevents T cell immune receptor and Ig and ITIM structural domains (TIGIT)-mediated NK cell activation, shielding colon adenocarcinoma cells from NK cell-mediated killing (Gur et al. 2015). And in oral squamous carcinoma, bacterial load was positively corelated with the potent neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL8 and negatively correlated with the expression of CD3E, this indicates that intratumoral bacteria-colonized microniches are immunosuppressive by recruiting neutrophils and excluding CD3 + T cells (Galeano Niño et al. 2022). In addition, an association between intratumor microbiota and immunogenicity in melanoma and triple-negative breast cancer has also been suggested, but the exact mechanism is unknown. This all suggests that some of the intratumoral microbiota may be a potential targets for cancer immunotherapy, although further research is still needed.

Effect of intratumor microbiota on cancer cell metastasis

The intratumor microbiota not only plays an important role in tumor growth but also influences tumor colonization and metastasis. Metastatic colonization has been reported to be a very inefficient process, with dramatic tumor cell death when distal organs are reached (Massagué and Obenauf 2016), and intra-tumor microbes can help tumor cells increase the efficiency of metastatic colonization. In a recent study, Aikun Fu et al. found that removal of intratumor microbiota significantly reduced lung metastasis without affecting primary tumor growth by studying intratumor microbiota in a mouse model of spontaneous breast cancer tumors. The main mechanism is due to the fact that during tumor metastasis colonization, circulating tumor cells carry intra-tumor microorganisms that enhance resistance to fluid shear stress in the circulatory system by reconstituting the actin cytoskeleton, thereby promoting host cell survival (Fu et al. 2022). This mechanism is not limited to breast cancer, as there is similar evidence in colorectal cancer that intra-tumoral microbiota can persist during metastasis and transmigration (Bullman et al. 2017). Notably, Aikun Fu's analysis of tumor cells in the PyMT circulation revealed that these intratumor microbiota were present more often among clusters of circulating tumor cells than among individual circulating tumor cells. In combination with recent studies on circulating tumor cell clusters, it has been found that circulating tumor clusters have a better ability to survive and trigger metastasis to distant organs (Aceto et al. 2014; Cheung et al. 2016). The mechanism may be related to the presence of intra-tumor microorganisms in the cytoplasm of cancer cells. Furthermore, in the mouse model of Parhi et al., it was observed that F. nucleatum not only increased the size of primary AT3 mammary tumors, but it also increased the number of lung metastases. This may be related to the fact that the intratumor microbiota can upregulate tumor matrix metalloproteinases (Parhi et al. 2020). In lung cancer, the intratumor microbiota can promote tumor metastasis by helping the host tumor cells to evade immune surveillance. In the mouse model of Le Noci et al., lung metastasis of melanoma B16 was significantly reduced in the lungs of mice using vancomycin/neomycin nebulized inhalation by a mechanism that may be associated with a reduction in bacterial load with a reduction in regulatory T cells and activation of T cells and NK cells (Le Noci et al. 2018). These all suggest that the intratumor microbiota may be a potential target for the early prevention of metastasis in a wide range of cancer types.

It is worth noting that the mechanisms by which the intratumoral microbiota affect tumor development do not function entirely independently and that many bacteria have overlapping mechanisms. For example, in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer, ETBF bacteria are able to promote inflammatory mucosal responses through binding to parietal receptors on colonic epithelial cells (CEC), causing β-catenin nuclear translocation and activation of tyrosine kinases, MAPKs and NF-κB leading to nuclear signaling and new gene transcription, leading to the development of colorectal cancer (Sears 2009). In addition to this, MAMPs also play a role in promoting chronic inflammation. Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) refer to interactions between the microbiota and host immunity that alter the composition of bacterial molecules essential to specific body sites. Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) refer to interactions between the microbiota and host immunity that alter the composition of bacterial molecules essential to specific body sites. The changes can activate pattern receptors of innate immunity, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization structural domains (NODs). Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) refer to interactions between the microbiota and host immunity that alter the composition of bacterial molecules essential to specific body sites. The changes activate innate immune pattern receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domains (NODs), and binding to these receptors activates the NF-κB pathway, which induces cytokine and interleukin expression to promote chronic inflammation (Siegel et al. 2014).

Intratumoral microbiota and gut microbiota

About 4 × 1013 microbial cells spanning ~ 3 × 103 species inhabit the human body: About 97% of these cells are bacteria in the colon, ~ 2–3% are extracolonic bacteria (proximal gut, skin, lungs, etc.), and ~ 0.1–1% are archaea and eukarya (including fungi) (Almeida et al. 2019; Sender et al. 2016). Such a high density of intestinal flora is naturally a major target for research on the potential impact of microbiota on oncogenes and cancer prognosis (Garrett et al. 2010). Changes in the composition of the gut microbiota have been shown to drive the majority of known microbial immunomodulatory effects in the human body, even for some malignancies outside the gut, such as lung, breast, and prostate cancers. The gut microbiota can modulate the immune response against tumorigenesis or directly influence drug toxicity and activity in cancer therapy by initiating metabolic processes. However, it is worth noting that extraintestinal malignancies can also accommodate the development of their own microbiota within the tissues and may accordingly play their own role in the process of tumor progression, affecting or even overwhelming the effects of the intestinal microbiota (Jin et al. 2019; Le Noci et al. 2018; Nejman et al. 2020; Tsay et al. 2021). For example, in breast cancer, pre-existing disturbances in the gut microbiota (e.g., F. nucleatum) have been shown to increase the metastasis of breast cancer cells (Parhi et al. 2020). However, in the MMTV-PyMT spontaneous breast cancer mouse model, in which only the intratumoral microbiota was eliminated and the intestinal microbiota remained intact, the occurrence of lung metastases was significantly reduced (Fu et al. 2022). This suggests that the intratumor microbiota may play a role in targeting the metastatic capacity of breast cancer cells independently of, and perhaps even in preference to, the gut microbiota for breast cancer cells, but this still needs to be confirmed by further studies.

The role of intratumoral microbiota in various cancers

Breast cancer

In recent decades, the incidence of breast cancer has risen to unprecedented levels worldwide, making it one of the leading causes of death for women in many parts of the world today (Darbre and Fernandez 2013). Extensive research efforts have identified a combination of genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors as contributing to the development of breast cancer (Barnes et al. 2011), but this only explains a limited global incidence and the origin of the majority of breast cases (estimated at up to 70%) remains unclear (Madigan et al. 1995). In recent years, a growing body of data has shown that there are different microbial profiles in the breast tissue of healthy women and breast cancer patients (Urbaniak et al. 2016). Hieken et al. found significantly higher relative abundance of Bacillus, Staphylococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, Flagellomycetes, and Bacteroides in breast cancer tissue, all of which have the ability to cause DNA damage in vitro (Hieken et al. 2016). Another study reported similar findings: in a qualitative survey of DNA from the mammary microbiota, Methanobacterium radiodurans was relatively abundant in tumor tissue, while Sphingomonas sp. was relatively abundant in paired normal tissue. The relative abundance of these two bacteria was negatively correlated in paired normal breast tissues, but not in tumor tissues. Notably, there was a negative correlation between bacterial DNA load and breast cancer disease stage (Xuan et al. 2014), both of which suggest that microflora dysbiosis may play a role in breast cancer tumorigenesis.

As mentioned earlier, microbiota can promote malignancy by inducing chronic inflammation and triggering uncontrolled innate and adaptive immune responses (Schwabe and Jobin 2013). Previous studies have demonstrated that an increased risk of breast cancer is strongly associated with the presence of chronic, persistent and dysregulated inflammation (Iyengar et al. 2016), but the specific mechanisms by which this inflammation arises are still unclear. It is clear that dysbiosis of the microflora can influence the increased risk of breast cancer (Rao et al. 2007); for example, infection of APCMin/ + mice with the hepatitis H virus leads to increased inflammation and a significant increase in the incidence of breast cancer in female mice among them (Rao et al. 2006). Claire et al. showed that dysbiosis of commensal flora in a mouse model promotes early recruitment of inflammatory myeloid cells into the mammary tissue microenvironment, thereby promoting early inflammation in the mammary gland and that this inflammation can persist during mammary tumor progression (Buchta Rosean et al. 2019). Some specific microbiota may also play a role in maintaining healthy mammary tissue by stimulating the host's inflammatory response. Studies have shown that Yanoikuyae is normally found in the breast tissue of healthy women and the dramatic decrease in its abundance in the corresponding tumor tissue suggests that this microorganism may have a probiotic function in the breast. Yanoikuyae expresses glycosphingolipid ligands, which are potent activators of INKT cells (Kinjo et al. 2005). INKT is an important mediator of cancer immunosurveillance (Terabe and Berzofsky 2007) and has an essential role in the control of breast cancer metastasis (Hix et al. 2011).

It has also been demonstrated that some intratumoral microorganisms can play a role in cancer development by modulating specific immune responses. For example, Lactococcus spp. can help prevent the development of cancer by regulating cellular immunity by maintaining the cytotoxic activity of resident natural killer NK cells (Carrega et al. 2014).In a murine model, FAP2-sufficient but not FAP2-deficient, F. nucleatum colonized orthotopic breast cancer and suppressed tumor-infiltrating T cells to promote tumor growth and metastasis (Parhi et al. 2020).

Recent studies have shown that the microbiota within breast tumors also influences the development of tumor metastasis. Parida and colleagues discovered that Bacteroides fragilis promotes the growth and metastatic progression of breast tumors in a mouse model and that this process is associated with the β-catenin and Notch1 pathways in breast tumor tissue (Parida et al. 2021). Also in a spontaneous mouse mammary tumor (BT) model, Aikun Fu et al. found that the intratumoral microbiota of breast cancer was predominantly present in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells. During metastatic colonization, intratumor bacteria carried by circulating tumor cells promoted host cell survival by enhancing resistance to fluid shear stress by reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton. And the intracellular bacteria can travel to the distal organ together with the host tumor cells, offering the possibility to establish the metastatic microbiota themselves (Fu et al. 2022). Overall, these findings support the view that the local microbiota can play an important role in the development or metastasis of breast cancer through a variety of pathways, providing a potential new avenue for breast cancer prevention and treatment.

Lung cancer

The lungs have the largest mucosal surface area, and as the main interface with the external environment, they were initially traditionally thought to be sterile in healthy individuals as bacteria could rarely be isolated from normal healthy lung tissue using conventional culture techniques (Baughman et al. 1987; Thorpe et al. 1987). However, since the first report on the culture-independent microbiota of the asthmatic airway (Hilty et al. 2010), more than 30 studies using different molecular techniques have shown that multiple microbial communities exist in the lung and are distinct from microbial populations in other parts of the body (including oral, nasal, skin, and vaginal) (Dickson et al. 2015). The available data show that the composition of the lung microbiota differs significantly between healthy people and patients with different lung diseases, and that the alpha diversity is significantly higher in healthy lung tissue than in lung tumor tissue. For example, Prevotella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Neisseria, Haemophilus and Fusobacterium are the most abundant bacterial genera in healthy lung tissue (Sommariva et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2016). In an analysis of lung microbiota from paired samples of tumor tissue and contralateral non-cancerous sites collected from 24 lung cancer patients and 18 healthy subjects, it was found that microbial diversity was significantly lower in lung cancer patients compared to controls, with Streptococcus spp. and Staphylococcus spp. being significantly higher in the cancer group than in the control group, respectively. According to one study that used both primary lung tissue samples and a validation cohort from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Proteobacteria were found to be more abundant in the lung cancer microbiome overall, with increased Acidovorax (phylum Proteobacteria) abundance specifically found in squamous cell carcinoma with TP53 mutations in smokers (Greathouse et al. 2018). These results suggest that the composition of the lung microbiota varies between healthy and diseased populations and that this variation is associated with the development of lung cancer (Cameron et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2018; Ramírez-Labrada et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2016). This also points, in another way, to the fact that analysis of specific bacterial phyla or genera may be a potential biomarker for the diagnosis of lung cancer.

The microbiota in the lungs can directly influence the growth of lung cancer cells. Among the mechanisms that have been proposed, both local regulation of the immune microenvironment and oncogenic pathways have been associated with the development of lung cancer. It has been suggested that dysbiosis of the lung microbiota can promote tumorigenesis through the activation of molecular pathways with oncogenic potential by specific microbial components (Ramírez-Labrada et al. 2020). Researchers found that parallel transcriptional analysis of bronchial epithelial cells exposed to Veillonella, Prevotella, and Streptococcus showed upregulation of the ERK/PI3K signaling pathway, and in vitro experiments showed that Veillonella directly promoted ERK/PI3K signaling in respiratory epithelial cells and lung tumor cells (Tsay et al. 2018). PI3K is known to be a key pathway involved in the pathogenesis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by regulating cell proliferation and survival, and this pathway represents an early event in lung cancer (Kostic et al. 2013; Sears et al. 2014). Furthermore, Apopa et al. discovered that CD36 may regulate lung carcinogenesis by influencing the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) pathway (Apopa et al. 2018; Koch et al. 2011), which is a key regulator of cell proliferation and carcinogenesis. Dysbiosis of the lung microbiota can therefore lead to the activation or upregulation of oncogenic pathways that promote lung cancer development.

In addition, due to the extensive exposure of the lungs to the external environment, they are a key site for immune-microbial interactions and are maintained in dynamic balance by resident cells in the lungs (Huffnagle et al. 2017; Lloyd and Marsland 2017; Pilette et al. 2001; Sommariva et al. 2020). These resident cells exert their immunomodulatory properties by inducing the production of regulatory T cells (Treg) (Soroosh et al. 2013) and the release of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), tumor growth-initiating northern tower (Tf-β) and interleukin 10 (IL-10) (Hussell and Bell 2014). There is growing evidence that the lung microbiota acts on resident immune cells to play a key role in promoting lung immune tolerance. In a recent study, Jin and colleagues used a KP mouse lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) model driven by a Kras activating point mutation and TP53 deletion to clearly demonstrate that increased local bacterial load and altered lung microbiota composition stimulate myeloid cells to produce Myd88-dependent IL-1β and IL-23. These cytokines induce Vy6 + Vδ1 + γδ T cell activation and proliferation, producing IL-17 and other effector molecules that promote inflammation and neutrophil infiltration, thereby driving precancerous inflammation and tumor cell proliferation (Jin et al. 2019). Notably, lung cancer growth was significantly reduced in germ-free (GF) mice and mice treated with antibiotics in a genetic model of lung cancer, where the delayed tumor growth observed in GF mice could also be attributed to a complete lack of tolerance mechanisms in the lungs (Gollwitzer et al. 2014; Herbst et al. 2011), such as the presence of immunomodulatory cells that cancer cells can use to avoid surveillance by the immune system. Overall, these results provide a strong scientific basis for designing new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of lung cancer that target the intrapulmonary microbiota.

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer and ranks second in cancer-related deaths worldwide (Sung et al. 2021). According to statistics, sporadic colorectal cancer stimulated by environmental factors (including obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking, the Western diet, etc.) accounts for the majority of colorectal cancers. These risk factors all contribute to changes in the composition of the gut microbiota, and together with the existing studies that have found individual strains of bacteria to have the ability to promote tumorigenesis, these results suggest an important role for the gut microbiota in the development and progression of colorectal cancer (Keum and Giovannucci 2019; Wong and Yu 2019). Some of these studies have also demonstrated the presence of intratumoral microbiota in colorectal cancer and the significant correlation between the differences in the composition of the intratumoral and extratumoral microbiota and the development of colorectal cancer. In a study of the microbiota of colorectal cancer patients versus healthy individuals, higher levels of F. nucleatum, Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis were detected in colorectal cancer tumor tissues, while cancer tissues had relatively higher abundance of Lactococcus and Fusobacterium and lower abundance of Pseudomonas and Shigella compared to paracancerous tissues (Janney et al. 2020). These results suggest a dynamic correlation between intestinal microbiota and colorectal carcinogenesis.

Among these, F. nucleatum is considered a potential microbial species contributing to colorectal cancer susceptibility (Schwabe and Jobin 2013; Sears and Garrett 2014) and is predominantly found in the tumor microenvironment (TME) (Brennan and Garrett 2019). F. nucleatum uses the virulence factor FadA to bind to the extracellular domain of E-cadherin, which induces colon cancer cell proliferation through activation of host CEC WNT/β-catenin signaling in addition to TLR4-activated signaling to NF-κB (Brennan and Garrett 2019). And F. nucleatum further induces a pro-inflammatory, tumor-promoting microenvironment by expanding myeloid-derived immune cells. Chamutal et al. found that F. nucleatum could inhibit the cytotoxic function of natural killer (NK) cells and other tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes through the interaction of the F. nucleatum protein Fap2 with the human TIGIT (inhibitory receptor), thereby helping tumor cells to complete immune evasion. Interestingly, so far, this interaction only occurs in human cells, and F. nucleatum does not bind to TIGIT in mice, for reasons that are not clear. In addition, F. nucleatum and its associated metastatic flora were found to persist in the distal liver metastases of colorectal cancer tumors (Bullman et al. 2017), suggesting that F. nucleatum and its associated metastatic microbiota influence antitumoral responses and may be involved in metastatic lesions (Bertocchi et al. 2021).

Other intratumor microbes associated with colorectal carcinomatosis include Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF) and Escherichia coli. ETBF stimulates carcinogenesis by activating host colonic epithelial cell (CEC) NF-κB and STAT3 pathways, while additionally recruiting procarcinogenic myeloid inflammation and inducing mucosal IL-17 production (Valguarnera and Wardenburg 2020). E. coli was previously thought to be primarily a benign bacterium. However, it has now been found that E. coli is capable of producing the genotoxin colibactin via a 50-kb heterozygous polyketide-non-ribosomal peptide synthase manipulator (pks + E. coli) (Pleguezuelos-Manzano et al. 2020). Detailed studies have demonstrated that colibactin causes DNA interstrand cross-links, DNA double-strand breaks, chromosomal aberrances, and cell cycle arrest in human cells in vitro (Allen and Sears 2019). Despite its unstable nature, colibactin forms specific DNA compounds that cause cytotoxicity and mutations (Wilson et al. 2019). These DNA damage responses, together with intestinal inflammation, promote tumor formation in mice. Dejea et al. showed that co-colonization of ETBF and pks + E.coli accelerated colon carcinogenesis and increased mortality in a CRC mouse model (Dejea et al. 2018). Furthermore, tumor-encapsulated ETBF has been shown to recruit other bacteria and immune cells to tumor sites and enhance IL-17-mediated inflammation (Dejea et al. 2018).

In addition to tumorigenesis, the intratumor microbiota plays an important regulatory role in the response to cancer treatment. For example, Yu et al. showed that F. nucleatum was able to promote chemoresistance by downregulating microRNAs (mia-18a and miR4802) to activate the autophagic pathway (Yu et al. 2017). Shi et al. found that colonotypic Bifidobacterium aggregates at tumor sites and promotes local anti-CD47 therapy via the STING pathway (Shi et al. 2020). In conclusion, we were able to find that the intratumor microbiota is inextricably linked to colorectal cancer, and continuing to explore the changes in the intestinal flora of colorectal cancer patients through experimental analysis is an important way for us to decipher the role of key bacteria in colorectal cancer.

Other tumors

In addition to the major organs mentioned above, intratumoral microbiota are also present in other types of cancer, including cervical cancer (Norenhag et al. 2020; Shannon et al. 2017), ovarian cancer, bone cancer, and glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) (Banerjee et al. 2018; Hieken et al. 2016; Nejman et al. 2020; Urbaniak et al. 2016). In a study by Nejman et al., it was revealed that the intratumoral microbiota is widespread in different types of cancer and that different microbial compositions and metabolites encoded by the intratumoral microbiota undergo different functions (Nejman et al. 2020). In oesophageal cancer, the presence of F. nucleatum in cancer tissue is associated with a poor prognosis. Yamamura et al. (Yamamura et al. 2016) suggested that F. nucleatum promotes infiltration of Treg lymphocytes into tumors in a chemokine-dependent manner (especially CCL20), thereby promoting aggressive tumor behavior. In skin cancer, the skin’s symbiotic microorganism Staphylococcus epidermidis produces 6-N-hydroxyaminopurine, a DNA polymerase inhibitor theat inhibits tumor cell proliferation in culture (Nakatsuji et al. 2018). In pancreatic cancer, limited PDAC progression was observed in both germ-free and antibiotic-treated mice using a preclinical mouse model, suggesting that the intratumoral microbiota promote PDAC progression through innate and adaptive immunosuppression mechanisms, whereas microbial ablation with antibiotics fosters T cell proliferation and immune activation, including tumor responsiveness to checkpoint inhibitor therapy (Pushalkar et al. 2018). In addition, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, although there is no conclusive evidence that the intratumoral microbiota can contribute to its development, it has been suggested that oral bacteria may contribute to tumorigenesis through specific metabolic activity and widespread inflammatory properties. The reason for this is that oral bacteria promote the metabolism of alcohol into the carcinogenic by-product acetaldehyde, the level of which induces DNA damage and enhances epithelial cell proliferation (Fan et al. 2018). The function and mechanism of action of the intratumoral microbiota in other types of cancer are still unclear and need to be supported by more experimental data.

Use of the intratumor microbiota in cancer prevention and treatment

Genomics-based studies have shown that most major types of human cancer contain an intratumoral microbiota (Kalaora et al. 2021; Nejman et al. 2020). These microbial communities vary by cancer type, and specific bacteria can contribute to the initiation and progression of cancer, affect the response of patients to treatment and thus affect surviva (Bullman et al. 2017; Geller et al. 2017; Nejman et al. 2020; Pernigoni et al. 2021; Poore et al. 2020; Riquelme et al. 2019; Serna et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2017). As the human microbiome is increasingly studied, the link between microbiota and various cancers is gradually being deciphered, which also provides a new design idea for improving existing cancer treatments or developing new cancer therapies.

The microbiota has been shown to be a key regulator of the carcinogenic process and the immune response to cancer cells, but most studies of tumor-associated microbiota have focused on tumors in the GI tract that are in communication with the outside world, such as colorectal, gastric, and lung cancers. Only recently has it been discovered that cancer types other than those of the digestive and respiratory tracts, such as breast, ovarian, and brain cancers, may also have microbiota of unique composition. It has been demonstrated that the intratumor microbiota can influence the treatment of related cancers. In chemotherapy, mycoplasma and bacteria can reduce the activity of chemotherapeutic drugs through metabolic pathways such as cytidine deaminase (CDDL). Geller et al. showed that intratumoral microbiota, mainly Aspergillus, in pancreatic tumors can metabolize the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine (2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine) to its inactive form 2',2'-difluorodeoxyuridine by cytidine deaminase (CDDL), thus reducing the efficacy of the chemotherapeutic drug. It also verified that intra-tumor bacteria have the ability to inhibit chemotherapeutic agents such as oxaliplatin in addition to the CDDL pathway, but the exact mechanism is unclear (Geller et al. 2017). The impact of intra-tumor microorganisms on the tumor immune response is not limited to affecting enzyme activity. In colorectal cancer, F. nucleatum alters the chemotherapy response in colorectal cancer by targeting TLR4 and MYD88 innate immune signaling pathways and activating autophagic pathways via specific microRNAs (Yu et al. 2017), or by increasing intestinal permeability, allowing bacterial translocation and thus maturation of TH17 cells in the lamina propria and effector lymph nodes, and enhancing the anti-tumor effect by promoting the chemotherapeutic effect of phosphoramidites (Viaud et al. 2013).

Intratumor microbiota play an important role in modulating drug efficacy in cancer therapy. Some evidence also suggests that intratumor microbiota can synergize with cancer immunotherapy, mainly because the presence of intratumor microbiota may increase tumor “heterogeneity” and promote anti-tumor immune responses (Cogdill et al. 2018). For example, the presence of HPV is associated with large aggregations of lymphocytes, such as IFN-g + CD8 + T lymphocytes and IL-17 + CD8 + T cells, in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (Partlová et al. 2015). Furthermore, HPV-positive tumors are more radiosensitive than HPV-negative tumor cells because HPV positivity causes more double-stranded DNA breaks and G2 phase cell cycle arrest (Rieckmann et al. 2013). Also, the intratumor microbiota is able to enhance the anti-tumor immune effect by generating an immunosuppressive microenvironment. In clinical models, recognition of bacteria by intratumoral innate immune cells (PRR) activates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, promotes the entry of various immune cells, and improves antigen presentation, thereby enhancing anti-tumor immune function.

Some studies have shown in patient biopsies that the intratumor microbiota can transfer with the host tumor cells from the primary site to the distant metastatic site, and the ability to carry bacteria is maintained after several passages, suggesting that treatment with antibiotics and reduction of bacterial load reduces tumor growth to some extent (Bullman et al. 2017; Fu et al. 2022). Therefore, the combination of antibiotic therapy with cancer treatment is also very common in clinical practice. For example, treatment of H. pylori-derived gastric lymphoma with triple or quadruple antibiotic therapy, administering direct-acting antivirals against active hepatitis C virus, and vaccinating against major human papillomavirus serotypes and hepatitis B virus to prevent urogenital, cervical, head and neck, and liver cancers (IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans 2012; Lowy and Schiller 2017; Stolte et al. 2002). However, there is conflicting evidence against the use of antibiotics in cancer treatment. Several studies on lung, colon, and pancreatic cancers have shown that elimination of intratumoral flora can inhibit tumor-promoting inflammatory processes, reduce cell proliferation, or convert tolerogenic TME to immunogenic TME (Bullman et al. 2017; Jin et al. 2019; Le Noci et al. 2018; Pushalkar et al. 2018). There is also clinical evidence that systemic antibiotics abolish the effects of immune checkpoint blockade and reduce patient survival (Derosa et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2019; Pinato et al. 2019). Patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who receive antibiotics before or just after initiating treatment have reduced survival. Patients receiving concomitant anti-Gram-positive antibiotics with cyclophosphamide therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or cisplatin therapy for relapsed lymphoma had lower overall response rates and reduced overall survival (Pflug et al. 2016).

The reason for this may be related to the fact that the microbiota in the tumor responds differently to various antibiotics than the microbiota in the rest of the body, including the intestinal microbiota. Aikun Fu et al. (Fu et al. 2022) found that these intracellular microbes survived upon cell-impermeable antibiotic treatment (Ampicillin and Gentamicin) (Kumar et al. 2017) but not upon cell-penetrating doxycycline treatment. On this basis, they also found that administration of an antibiotic cocktail (ATBx) via drinking water (DW) to MMTV-PyMT spontaneous breast cancer mice (Iida et al. 2013; Pushalkar et al. 2018) was effective in eliminating the gut and tumor microbiota. However, either by tail vein injection of ATBx or DW administration of the penetrating antibiotic doxycycline only eliminates the intratumoral microbiota while the intestinal microbiota remains intact (Fig. 2). These results suggest that different types of antibiotics can have different consequences for the gut microbiota, extracellular tumor microbiota, and intracellular tumor microbiota through different routes of administration, leading to more complex clinical outcomes for patients treated with combination antibiotics in cancer therapy.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram depicting various antibiotic administration strategies and their effects on the gut and tumor microbiota. Different combinations of antibiotics and routes of administration can lead to different outcomes for the flora

Conclusion

With the progress of research on the human microbiome and the upgrading of technology, it is increasingly recognized that human tumors contain a large number of viable symbiotic microorganisms, and it has been found that intratumor microbiota play an important role in the tumor microenvironment that regulates tumor progression and affects tumor prognosis (Banerjee et al. 2015, 2018; Costantini et al. 2018; Hieken et al. 2016; Nejman et al. 2020; Riquelme et al. 2019; Urbaniak et al. 2016; Xuan et al. 2014). In many cases, genomic instability due to increased mutations, activation of oncogenic pathways, suppression of anti-tumor immune responses, and the ability to counteract circulatory fluid shear by increasing host tumor cells could provide potential explanations for the interrelationship between intratumor microbiota and cancer.

Tumor cells hijacked by microbes may be more common in cancer patients than hitherto known, and the relationship between the intratumor microbiota, the tumor microenvironment, and cancer cells may be more complex than hitherto known. In this review, we describe the origin of the intratumoral microbiota, how specific bacterial microbial members and the composition of microbiome community influence tumor development, and the role of intratumoral microbes in cancer therapy. Notably, recent studies have now demonstrated that the intratumor microbiota can enable host tumor cells to survive fluid shear in the circulatory system to aid in their metastatic colonization without affecting tumor growth. Therefore, is it not better to prevent the metastasis of multiple cancer types at an early stage in cancer treatment than to have a comprehensive approach on how to inhibit the growth of tumors. Second, in cancer treatment, the response of the microbiota within the tumor to various antibiotics may differ from the commensal microbiota in the rest of the site, which explains to some extent the conflicting results in the use of antibiotics in cancer treatment in the past. Predictions that studies targeting intratumor microbiota could provide insights for better use of antimicrobial therapy.

The field is still very young, and we still have many questions to solve. As in the past, infection was thought to be one of the sources of microorganisms in tumors, but current studies show that microbiota can still be found in tumors of both patients and mice in the absence of any infection, and that the composition does not differ significantly. Does this suggest in another way that the intratumor microbiota may be an inherent and integral component of the tumor tissue rather than an incidental occurrence of pathogenic infection? Are there other ways in which the intratumor microbiota can influence tumor metastasis? Is the same low-load intratumor microbiota as important as tumor stem cells in metastasis? How should antibiotics be matched to the oncological microbiota in cancer treatment? What can be done about the inevitable stratification of therapeutic response due to the different composition of the microbiota? As advances are made in the treatment of cancer and other diseases, there is still a need to develop multifaceted strategies to detect and modulate these factors to optimize existing treatment options and effectively treat the disease.

The gut microbiota has been extensively studied in the context of carcinogenesis and tumor response to immunotherapy, but the impact and mechanisms of action of the microbiota at other sites, particularly within tumors, are still less well studied. More experimental studies are needed to understand whether these microbes are passengers or participants in the development of tumors. Further research and elucidation of the mechanisms of action of the intratumoral microbiota and their impact on tumor therapy are therefore necessary in future to provide valuable insights into potential cancer treatments and to improve existing cancer treatments to maximize the effectiveness of anti-tumor therapy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by YG and MW. Figures are created with XH. The first draft of the manuscript was written by YG and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81472449).

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aceto N, Bardia A, Miyamoto DT, Donaldson MC, Wittner BS, Spencer JA, Maheswaran S (2014) Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis. Cell 158(5):1110–1122. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Sears CL (2019) Impact of the gut microbiome on the genome and epigenome of colon epithelial cells: contributions to colorectal cancer development. Genome Med 11(1):11. 10.1186/s13073-019-0621-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida A, Mitchell AL, Boland M, Forster SC, Gloor GB, Tarkowska A, Finn RD (2019) A new genomic blueprint of the human gut microbiota. Nature 568(7753):499–504. 10.1038/s41586-019-0965-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieva MR, Vogelmann R, Covacci A, Tompkins LS, Nelson WJ, Falkow S (2003) Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacterpylori CagA. Science 300(5624):1430–1434. 10.1126/science.1081919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apopa PL, Alley L, Penney RB, Arnaoutakis K, Steliga MA, Jeffus S, Orloff MS (2018) PARP1 is up-regulated in non-small cell lung cancer tissues in the presence of the cyanobacterial toxin microcystin. Front Microbiol 9:1757. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baban CK, Cronin M, O’Hanlon D, O’Sullivan GC, Tangney M (2010) Bacteria as vectors for gene therapy of cancer. Bioeng Bugs 1(6):385–394. 10.4161/bbug.1.6.13146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Wei Z, Tan F, Peck KN, Shih N, Feldman M, Robertson ES (2015) Distinct microbiological signatures associated with triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep 5:15162. 10.1038/srep15162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Tian T, Wei Z, Shih N, Feldman MD, Peck KN, Robertson ES (2018) Distinct microbial signatures associated with different breast cancer types. Front Microbiol 9:951. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes BB, Steindorf K, Hein R, Flesch-Janys D, Chang-Claude J (2011) Population attributable risk of invasive postmenopausal breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes for modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. Cancer Epidemiol 35(4):345–352. 10.1016/j.canep.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman RP, Thorpe JE, Staneck J, Rashkin M, Frame PT (1987) Use of the protected specimen brush in patients with endotracheal or tracheostomy tubes. Chest 91(2):233–236. 10.1378/chest.91.2.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y, Hand TW (2014) Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 157(1):121–141. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y, Naik S (2013) Compartmentalized and systemic control of tissue immunity by commensals. Nat Immunol 14(7):646–653. 10.1038/ni.2604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudes D, Low B, Pawelek J (2000) Tumor-targeted salmonella. Highly selective delivery vectors. Adv Exp Med Biol 465:57–63. 10.1007/0-306-46817-4_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertocchi A, Carloni S, Ravenda PS, Bertalot G, Spadoni I, Lo Cascio A, Rescigno M (2021) Gut vascular barrier impairment leads to intestinal bacteria dissemination and colorectal cancer metastasis to liver. Cancer Cell 39(5):708-724.e711. 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan CA, Garrett WS (2019) Fusobacterium nucleatum - symbiont, opportunist and oncobacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol 17(3):156–166. 10.1038/s41579-018-0129-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchta Rosean C, Bostic RR, Ferey JCM, Feng TY, Azar FN, Tung KS, Rutkowski MR (2019) Preexisting commensal dysbiosis is a host-intrinsic regulator of tissue inflammation and tumor cell dissemination in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Res 79(14):3662–3675. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-18-3464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullman S, Pedamallu CS, Sicinska E, Clancy TE, Zhang X, Cai D, Meyerson M (2017) Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science 358(6369):1443–1448. 10.1126/science.aal5240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron SJS, Lewis KE, Huws SA, Hegarty MJ, Lewis PD, Pachebat JA, Mur LAJ (2017) A pilot study using metagenomic sequencing of the sputum microbiome suggests potential bacterial biomarkers for lung cancer. PLoS ONE 12(5):e0177062. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrega P, Bonaccorsi I, Di Carlo E, Morandi B, Paul P, Rizzello V, Ferlazzo G (2014) CD56(bright)perforin(low) noncytotoxic human NK cells are abundant in both healthy and neoplastic solid tissues and recirculate to secondary lymphoid organs via afferent lymph. J Immunol 192(8):3805–3815. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti PA (1994) Oxy-radicals and cancer. Lancet 344(8926):862–863. 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92832-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung KJ, Padmanaban V, Silvestri V, Schipper K, Cohen JD, Fairchild AN, Ewald AJ (2016) Polyclonal breast cancer metastases arise from collective dissemination of keratin 14-expressing tumor cell clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(7):E854-863. 10.1073/pnas.1508541113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I, Blaser MJ (2012) The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat Rev Genet 13(4):260–270. 10.1038/nrg3182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churin Y, Al-Ghoul L, Kepp O, Meyer TF, Birchmeier W, Naumann M (2003) Helicobacterpylori CagA protein targets the c-Met receptor and enhances the motogenic response. J Cell Biol 161(2):249–255. 10.1083/jcb.200208039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogdill AP, Gaudreau PO, Arora R, Gopalakrishnan V, Wargo JA (2018) The impact of intratumoral and gastrointestinal microbiota on systemic cancer therapy. Trends Immunol 39(11):900–920. 10.1016/j.it.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini L, Magno S, Albanese D, Donati C, Molinari R, Filippone A, Merendino N (2018) Characterization of human breast tissue microbiota from core needle biopsies through the analysis of multi hypervariable 16S-rRNA gene regions. Sci Rep 8(1):16893. 10.1038/s41598-018-35329-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbre PD, Fernandez MF (2013) Environmental oestrogens and breast cancer: long-term low-dose effects of mixtures of various chemical combinations. J Epidemiol Community Health 67(3):203–205. 10.1136/jech-2012-201362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, Plummer M (2012) Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol 13(6):607–615. 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70137-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejea CM, Fathi P, Craig JM, Boleij A, Taddese R, Geis AL, Sears CL (2018) Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science 359(6375):592–597. 10.1126/science.aah3648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M, Halpenny D, Fidelle M, Rizvi H, Routy B (2018) Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 29(6):1437–1444. 10.1093/annonc/mdy103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Freeman CM, McCloskey L, Beck JM, Huffnagle GB, Curtis JL (2015) Spatial variation in the healthy human lung microbiome and the adapted island model of lung biogeography. Ann Am Thorac Soc 12(6):821–830. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-029OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzutsev A, Badger JH, Perez-Chanona E, Roy S, Salcedo R, Smith CK, Trinchieri G (2017) Microbes and cancer. Annu Rev Immunol 35:199–228. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwell CA, Dreyfus LA (2000) DNase I homologous residues in CdtB are critical for cytolethal distending toxin-mediated cell cycle arrest. Mol Microbiol 37(4):952–963. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa VO, Gerardo NM, Inouye DW, Medina M, Xavier JB (2012) Microbiology. Animal behavior and the microbiome. Science 338(6104):198–199. 10.1126/science.1227412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Peters BA, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM, Purdue MP, Freedman ND, Ahn J (2018) Drinking alcohol is associated with variation in the human oral microbiome in a large study of American adults. Microbiome 6(1):59. 10.1186/s40168-018-0448-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig DI, Reid TM, Loeb LA (1994) Reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 54(7 Suppl):1890s–1894s [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemer B, Lynch DB, Brown JM, Jeffery IB, Ryan FJ, Claesson MJ, O’Toole PW (2017) Tumour-associated and non-tumour-associated microbiota in colorectal cancer. Gut 66(4):633–643. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu A, Yao B, Dong T, Chen Y, Yao J, Liu Y, Cai S (2022) Tumor-resident intracellular microbiota promotes metastatic colonization in breast cancer. Cell 185(8):1356-1372.e1326. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeano Niño JL, Wu H, LaCourse KD, Kempchinsky AG, Baryiames A, Barber B, Bullman S (2022) Effect of the intratumoral microbiota on spatial and cellular heterogeneity in cancer. Nature 611(7937):810–817. 10.1038/s41586-022-05435-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Li S, Ma Z, Liang S, Shan T, Zhang M, Feng X (2016) Presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis in esophagus and its association with the clinicopathological characteristics and survival in patients with esophageal cancer. Infect Agent Cancer 11:3. 10.1186/s13027-016-0049-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett WS (2015) Cancer and the microbiota. Science 348(6230):80–86. 10.1126/science.aaa4972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett WS, Gordon JI, Glimcher LH (2010) Homeostasis and inflammation in the intestine. Cell 140(6):859–870. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller LT, Barzily-Rokni M, Danino T, Jonas OH, Shental N, Nejman D, Straussman R (2017) Potential role of intratumor bacteria in mediating tumor resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine. Science 357(6356):1156–1160. 10.1126/science.aah5043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer ES, Saglani S, Trompette A, Yadava K, Sherburn R, McCoy KD, Marsland BJ (2014) Lung microbiota promotes tolerance to allergens in neonates via PD-L1. Nat Med 20(6):642–647. 10.1038/nm.3568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greathouse KL, White JR, Vargas AJ, Bliskovsky VV, Beck JA, von Muhlinen N, Harris CC (2018) Interaction between the microbiome and TP53 in human lung cancer. Genome Biol 19(1):123. 10.1186/s13059-018-1501-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra L, Guidi R, Frisan T (2011) Do bacterial genotoxins contribute to chronic inflammation, genomic instability and tumor progression? Febs j 278(23):4577–4588. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08125.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur C, Ibrahim Y, Isaacson B, Yamin R, Abed J, Gamliel M, Mandelboim O (2015) Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity 42(2):344–355. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ (2014) Breaking bad: manipulation of the host response by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Eur J Immunol 44(2):328–338. 10.1002/eji.201344202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T, Zhang X, Mima K, Bullman S, Sukawa Y, Nowak JA, Ogino S (2018) Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer relates to immune response differentially by tumor microsatellite instability status. Cancer Immunol Res 6(11):1327–1336. 10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-18-0174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassane DC, Lee RB, Mendenhall MD, Pickett CL (2001) Cytolethal distending toxin demonstrates genotoxic activity in a yeast model. Infect Immun 69(9):5752–5759. 10.1128/iai.69.9.5752-5759.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst T, Sichelstiel A, Schär C, Yadava K, Bürki K, Cahenzli J, Harris NL (2011) Dysregulation of allergic airway inflammation in the absence of microbial colonization. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184(2):198–205. 10.1164/rccm.201010-1574OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieken TJ, Chen J, Hoskin TL, Walther-Antonio M, Johnson S, Ramaker S, Degnim AC (2016) The microbiome of aseptically collected human breast tissue in benign and malignant disease. Sci Rep 6:30751. 10.1038/srep30751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi H, Tsutsumi R, Muto S, Sugiyama T, Azuma T, Asaka M, Hatakeyama M (2002) SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase as an intracellular target of Helicobacterpylori CagA protein. Science 295(5555):683–686. 10.1126/science.1067147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilty M, Burke C, Pedro H, Cardenas P, Bush A, Bossley C, Cookson WO (2010) Disordered microbial communities in asthmatic airways. PLoS ONE 5(1):e8578. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hix LM, Shi YH, Brutkiewicz RR, Stein PL, Wang CR, Zhang M (2011) CD1d-expressing breast cancer cells modulate NKT cell-mediated antitumor immunity in a murine model of breast cancer metastasis. PLoS ONE 6(6):e20702. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XZ, Gao P, Song YX, Xu Y, Sun JX, Chen XW, Wang ZN (2019) Antibiotic use and the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients: a pooled analysis of 2740 cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 8(12):e1665973. 10.1080/2162402x.2019.1665973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffnagle GB, Dickson RP, Lukacs NW (2017) The respiratory tract microbiome and lung inflammation: a two-way street. Mucosal Immunol 10(2):299–306. 10.1038/mi.2016.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium (2012) Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486(7402):207–214. 10.1038/nature11234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussell T, Bell TJ (2014) Alveolar macrophages: plasticity in a tissue-specific context. Nat Rev Immunol 14(2):81–93. 10.1038/nri3600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2012) Biological agents. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 100(8):1–441 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida N, Dzutsev A, Stewart CA, Smith L, Bouladoux N, Weingarten RA, Goldszmid RS (2013) Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science 342(6161):967–970. 10.1126/science.1240527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar NM, Zhou XK, Gucalp A, Morris PG, Howe LR, Giri DD, Dannenberg AJ (2016) Systemic correlates of white adipose tissue inflammation in early-stage breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 22(9):2283–2289. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-15-2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janney A, Powrie F, Mann EH (2020) Host-microbiota maladaptation in colorectal cancer. Nature 585(7826):509–517. 10.1038/s41586-020-2729-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Lagoudas GK, Zhao C, Bullman S, Bhutkar A, Hu B, Jacks T (2019) Commensal microbiota promote lung cancer development via γδ T cells. Cell 176(5):998-1013.e1016. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobin C (2018) Precision medicine using microbiota. Science 359(6371):32–34. 10.1126/science.aar2946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaora S, Nagler A, Nejman D, Alon M, Barbolin C, Barnea E, Samuels Y (2021) Identification of bacteria-derived HLA-bound peptides in melanoma. Nature 592(7852):138–143. 10.1038/s41586-021-03368-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawanishi S, Ohnishi S, Ma N, Hiraku Y, Murata M (2017) Crosstalk between DNA damage and inflammation in the multiple steps of carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 10.3390/ijms18081808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keum N, Giovannucci E (2019) Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 16(12):713–732. 10.1038/s41575-019-0189-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidane D (2018) Molecular Mechanisms of H. pylori-induced DNA double-strand breaks. Int J Mol Sci. 10.3390/ijms19102891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinjo Y, Wu D, Kim G, Xing GW, Poles MA, Ho DD, Kronenberg M (2005) Recognition of bacterial glycosphingolipids by natural killer T cells. Nature 434(7032):520–525. 10.1038/nature03407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Hussein F, Woeste A, Gründker C, Frontzek K, Emons G, Hawighorst T (2011) CD36-mediated activation of endothelial cell apoptosis by an N-terminal recombinant fragment of thrombospondin-2 inhibits breast cancer growth and metastasis in vivo. Breast Cancer Res Treat 128(2):337–346. 10.1007/s10549-010-1085-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Garrett WS (2013) Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 14(2):207–215. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM, Meyerson M (2012) Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res 22(2):292–298. 10.1101/gr.126573.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Herold JL, Schady D, Davis J, Kopetz S, Martinez-Moczygemba M, Xu Y (2017) Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus promotes colorectal tumor development. PLoS Pathog 13(7):e1006440. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu JK, Surh YJ (2008) Inflammation: gearing the journey to cancer. Mutat Res 659(1–2):15–30. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Tejero M, Galán JE (2000) A bacterial toxin that controls cell cycle progression as a deoxyribonuclease I-like protein. Science 290(5490):354–357. 10.1126/science.290.5490.354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Noci V, Guglielmetti S, Arioli S, Camisaschi C, Bianchi F, Sommariva M, Sfondrini L (2018) Modulation of pulmonary microbiota by antibiotic or probiotic aerosol therapy: a strategy to promote immunosurveillance against lung metastases. Cell Rep 24(13):3528–3538. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.08.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Sung JY, Yong D, Chun J, Kim SY, Song JH, Park MS (2016) Characterization of microbiome in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with lung cancer comparing with benign mass like lesions. Lung Cancer 102:89–95. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]