Abstract

Candida albicans comprises over 80% of isolates from all forms of human candidiasis. Biofilm formation enhances their capacity to withstand therapeutic treatments. In addition to providing protection, biofilm formation by C. albicans enhances its pathogenicity. Understanding the fundamental mechanisms underlying biofilm formation is crucial to advance our understanding and treatment of invasive Candida infections. An initial screening of 57 Candida spp. isolates using CHROMagar Candida (CHROMagar) media revealed that 46 were C. albicans. Of these, 12 isolates (33.3%) had the capacity to form biofilms. These 12 isolates were subjected to multiple biochemical and physiological tests, as well as 18 S rRNA sequencing, to confirm the presence of C. albicans. Upon analysis of their sensitivity to conventional antifungal agents, the isolates showed varying resistance to terbinafine (91.6%), voriconazole (50%), and fluconazole (42%). Among these, only CD50 showed resistance to all antifungal agents. Isolate CD50 also showed the presence of major biofilm-specific genes such as ALS3, EFG1, and BCR1, as confirmed by PCR. Exposure of CD50 to gentamicin-miconazole, a commonly prescribed drug combination to treat skin infections, resulted in elevated levels of gene expression, with ALS3 showing the highest fold increase. These observations highlight the necessity of understanding the proteins involved in biofilm formation and designing ligands with potential antifungal efficacy.

Keywords: CHROMagar, Biofilm, Antimicrobial susceptibility, ALS3

Introduction

Nosocomial infections arise primarily in patients admitted to medical facilities for treatment purposes as well as in healthcare personnel. The 6th most common nosocomial pathogen is Candida species which is also a leading cause of bloodstream infections [1]. Candida sps. are normal components of the microbial flora of the human body, inhabiting the mouth, intestines, and vagina. They cause candidemia, which spreads mainly in immunocompromised patients, patients with pre-existing diseases, and patients with a long history of antibiotics [2]. Interestingly, increased incidences of Candida infections were correlated with previous antibiotic treatment (76.9%), presence of a central venous catheter (71.2%), and total parenteral nutrition (55.8%) [3]. Resistance to antifungal agents has emerged as a significant clinical challenge and major public health concern with respect to candidiasis [4]. Among the different species, Candida albicans is the major pathogen, accounting for more than 80% of candidemia cases, although other species have also shown pathogenicity [5, 6].

Candida albicans is a polymorphic fungus that exhibits various morphologies such as budding yeast form, pseudohyphae, hyphae, chlamydospores, and opaque cells [7]. One mechanism by which microbes achieve resistance to antimicrobial drugs is through the formation of biofilms. The ability of fungal biofilms to resist antimicrobial agents has emerged as a significant challenge for the treatment of these infections. Additionally, biofilms play a critical role in shielding them from host immune cells, as well as other external stressors [8]. Candida biofilms are found on a range of surfaces, including both living organisms (mucous membranes, organs, and blood vessels) and non-living organisms. They notably form on medical devices used in contact with patients’ bodies [9]. Biofilms envelop cells within an extracellular matrix and manifest distinct traits separate from their individual, free-floating forms [10]. This altered physiology includes changes in gene expression, metabolism, and stress response pathways that can affect the efficacy of antimicrobial agents.

Some of the genes involved in C. albicans biofilms are ALS3, EFG1, and BCR1. ALS3, belonging to the agglutin-like sequence, is known to be essential in C. albicans, where it plays a key role in biofilm formation, thus aiding adherence as well as invasion into host cells [11]. ALS3 deletion mutants of C. albicans have been observed to form disordered and thin biofilms with diminished binding to cells and material surfaces [12]. Two of the major transcription factors involved in biofilm formation by C. albicans are EFG1 and BCR1 [13]. Deletion mutants of EFG1 negatively modulate C. albicans filamentation and biofilm formation [14]. Interestingly, EFG1 has also been shown to modulate ASL3 expression through its binding to the ALS3 promoter region [15]. A better understanding of the mechanisms of biofilm formation and persistence is required to develop more effective treatment strategies for fungal biofilm-associated infections.

The present study aimed to isolate C. albicans from various clinical samples and evaluate them based on biofilm formation and antifungal resistance. This study also focused on the expression profiles of genes known to play a role in biofilm production in the presence of commercially available antifungal drugs. Identifying the genes involved in resistance mechanisms could help in designing effective treatment strategies for C. albicans infections.

Materials and methods

Screening for candida albicans

Clinical isolates of Candida strains were obtained from the Unibiosys Research Laboratory, Kochi, following strict aseptic procedures. The samples were collected over a period of to 6–7 months in 2022. This three-year analytical study included 57 Candida isolates obtained from patients with clinical manifestations of candidiasis. Yeast-like growth on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) was inoculated onto CHROMagar, prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (HiMedia, India). Light green-colored smooth colonies were identified as C. albicans, while blue to purple, dark green, and purple colonies were considered indicative of Candida tropicalis, C. dubliniensis, and Candida krusei, respectively [5, 16, 17]. The detection of C. albicans in this specialised medium is based on the degradation of chromogenic hexosaminidase by N-acetyl galactosaminidase [17].

Screening for biofilm forming Candida albicans

Biofilm screening was performed using a microtitre plate biofilm assay [18, 19], The confirmed cultures were inoculated in Sabouraud’s dextrose broth and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Diluted cultures (100 µl) were added to a 96-well microtitre plate and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, crystal violet solution (0.1%) (CV) was added to stain the biofilm, followed by washing and drying of the plate. For quantification, 30% acetic acid was added to solubilise the stain and the absorbance was measured at 590 nm [20].

Microbiological analysis

Gram staining was conducted directly on isolates showing gram-positive budding yeast cells obtained from both Chlamydospore formation assessment (CMA) and SDA plates to detect gram-positive yeast and pseudo hyphae [16, 17]. The Reynolds-Braude phenomenon, used for presumptive Candida albicans identification, involves treating isolates with pooled human serum (0.5 mL), followed by incubation for 2 to 4-hour incubation at 37 °C. Examination under 40X magnification revealed germ tube formation, identified by long tube-like projections from cells [21]. CMA involved inoculating corn meal agar plates (with 1% Tween 80) with cells from a 16-hour SDA slant and incubating for 2–4 days at 25–30 °C. Microscopic examination at 10X magnification estimated chlamydospore presence [22], characterized by thick-walled round structures. Ball-like clusters of budding cells indicate the presence of C. albicans.

Physiological studies

The urease test was performed after inoculation of the isolates on urea agar, and the medium was incubated at 25–30 °C for up to 4 days. A change in the colour of the medium to pink with growth was considered positive. Most Candida species, except C. krusei, do not hydrolyse urea.Carbohydrate fermentation tests were performed by inoculating isolates (200 µl) into 2% sugar broth (glucose, maltose, sucrose, lactose, galactose, cellobiose) in Durham’s tubes and incubating at 30 °C for 3–5 days. The carbohydrate assimilation test was performed using an isolate suspension in saline, adjusted to McFarland standard 4 (12 × 108 cells), which was spread on Yeast Nitrogen Base agar (HiMedia). Filter paper disks soaked in 4% sugar solutions (glucose, maltose, lactose, sucrose, inositol, and xylose) were placed on the plate and incubated at 25 °C for 24–48 h. Growth around the disk indicated positive assimilation of the respective carbohydrate [23].

Antifungal susceptibility analysis of C. albicans

The antifungal susceptibility test(disc diffusion method) for Candida albicans involved placing Clotrimazole, Fluconazole, Gentamicin, Terbinafine, and Voriconazole disks (1 µg/ml, Himedia) on Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) swabbed with C. albicans inoculum adjusted to McFarland standards of 0.5. After incubation at 37 °C for 18–24 h, the zones of inhibition were measured and interpreted based on the CLSI-approved M44-A2 guidelines (CLSI., 2009) [24]. This procedure was conducted on 12 isolates to determine their susceptibility to the tested antifungal agents.

Evaluation of antibiotic resistance of biofilm by resazurin microtiter plate method

In this study, we examined the susceptibility of 12 isolates to Clotrimazole, Fluconazole, Gentamicin, Terbinafine, and Voriconazole. The cultures were grown in Sabouraud broth for 48 h at 37 °C in a 96-well plate. Upon biofilm formation, varying concentrations of antibiotics (0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 µg/ml) were added and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, 20 µL of 0.5% resazurin was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The pink colour indicates growth [25].

Identification of Candida sps. by sequencing

PCR amplification of the domain of the large subunit of 18 S rRNA was performed using the D1/D2 primers (D1 5’-ACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC-3’, D2 5’-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG-3’), The PCR reaction followed by an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles each at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 52 °C for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 45 s, and a final elongation at 72 °C for 8 min. The amplified product was verified on 1% agarose gel stained with 1 µg/ml ethidium bromide. The amplified PCR product was then eluted using a gel purification kit and procedure performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (company). The PCR products were sequenced using Sanger sequencing. The derived sequence was analysed using BLASTn to identify the fungal species. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using MEGA X [26], in which the tree was inferred using the Neighbour-joining method [27] with evolutionary distances computed using the maximum composite likelihood method [28].

Screening for biofilm specific genes

Genomic DNA of fungal isolate CD50 was collected from biofilms formed in 48 h culture grown in Sabouraud broth. The biofilm was collected by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 5 min, followed by multiple washes with Tris EDTA buffer. The biofilm was resuspended in Tris EDTA for 1 h, followed by incubation with lysozyme (50 µL), Proteinase K (25 µL), and SDS (100 µL of 10%) at 55 °C for 45 min. After incubation, 160 µL CTAB solution and 200 µL of 5 M NaCl were added to the lysate. The mixture was incubated at 65 °C for 10 min. After incubation, equal volumes of phenol, chloroform, and isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) were added and mixed. The mixture was centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 rpm. The upper aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, followed by the addition of ice-cold isopropanol and incubated for 1 h at -20 °C. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, the DNA was pelleted and washed with 70% ethanol, followed by another round of centrifugation. The pellet was air-dried and dissolved in 50 µL Tris-EDTA buffer. Primers used for the detection of EFG1, BCR1, and ALS3 are listed in Table S1. The PCR reaction was carried out with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 12 min, followed by 30 cycles each at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 63 °C for 30 s, and extension at 68 °C for 30 s, and a final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified products were verified on 1% agarose gel stained with 1 µg/ml ethidium bromide.

cDNA synthesis

Cellular RNA was extracted from the CD50 isolate using the TRIzol reagent. The isolated RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using a cDNA kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit). The reaction mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, followed by incubation for 120 min at 37 °C. cDNA synthesis was stopped by heating the mixture at 85 °C for 5 min. The cDNA was then used for quantitative expression analysis.

Relative gene expression analysis

The relative gene expression of biofilm- specific genes ALS3, EFG1, and BCR1 of Candida albicans isolate CD50 in the absence and presence of gentamycin-miconazole combination drug was performed using quantitative PCR (qPCR). qPCR was done in BIO-RAD CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System using SYBR Green Quantitect Kit (Qiagen). 3 µl of 1:10 diluted cDNA was used for the PCR reaction along with gene-specific primers (Table S2). The 18 S rRNA gene was used as the housekeeping control. After 15 min of activation of the modified Taq polymerase at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 20s at 95 °C (denaturation), 20s at 60 °C (annealing), and 30s at 72 °C (extension) were performed. Data were acquired at 72 °C, and Ct values were determined for each reaction. Relative gene expression (2 − ∆∆Ct) was determined from the derived Ct values and plotted. 18 S rRNA was used as the internal control [29, 30].

Results

Screening for Candida albicans

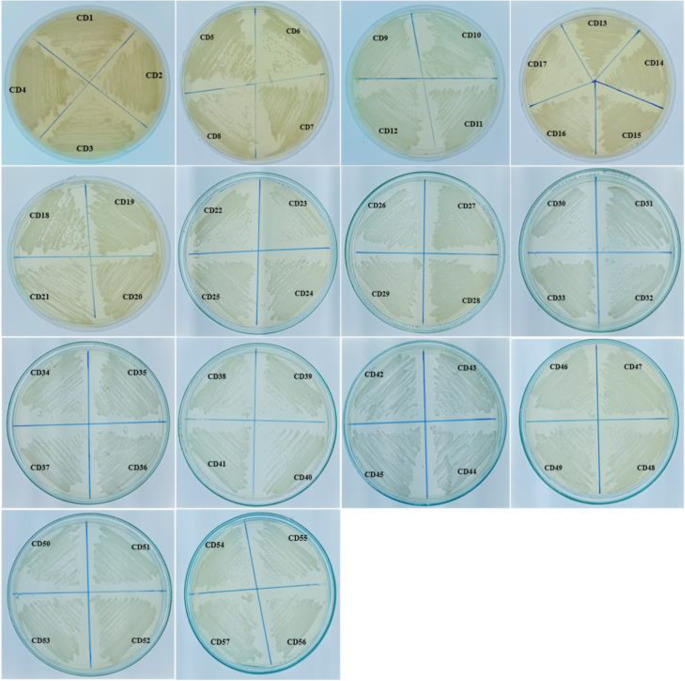

In this study, both Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) and CHROMagar were utilised as primary plating media for the isolation of Candida sp. Discrepancies were observed between the two media in terms of growth rate but not colony size. SDA and HiCrome agar supported the growth of all 57 Candida isolates and were named CD1–CD57 (Table 1; Fig. 1). The typical opaque, smooth, creamy white pasty colonies on SDA were suggestive of Candida sp. (Sumathi and Devipriya, 2016). Of the 57 isolates, 36 were identified as C. albicans based on the characteristic green-blue colonies observed on CHROMagar (Fig. 2). CHROMagar offers a significant advantage in clinical settings due to its capability to detect mixed cultures of yeast in clinical specimen [31].

Table 1.

Total Candida isolates on Sabouraud’s Dextrose Agar and CHROM agar media

| Isolates on SDA (57 isolates) | Isolates on CHROM agar media (57 isolates) | Light green-Blue Isolates on CHROMagar indicating C.albicans (36 isolates) |

|---|---|---|

| CD1 to CD57 | CD1 to CD57 | CD1, CD2, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD9, CD10, CD12, CD13, CD15, CD16, CD17, CD19, CD21, CD22, CD25, CD26, CD27, CD31, CD32, CD34 to CD41, CD43, CD44, CD48 to CD51, CD55, CD57. |

Fig. 1.

The colonial characteristics of different Candida species on Sabouraud’s Dextrose Agar medium

Fig. 2.

The colonial characteristics of different Candida species on CHROMagar medium. Blue-Green colonies (paler edges) are representative of C. albicans

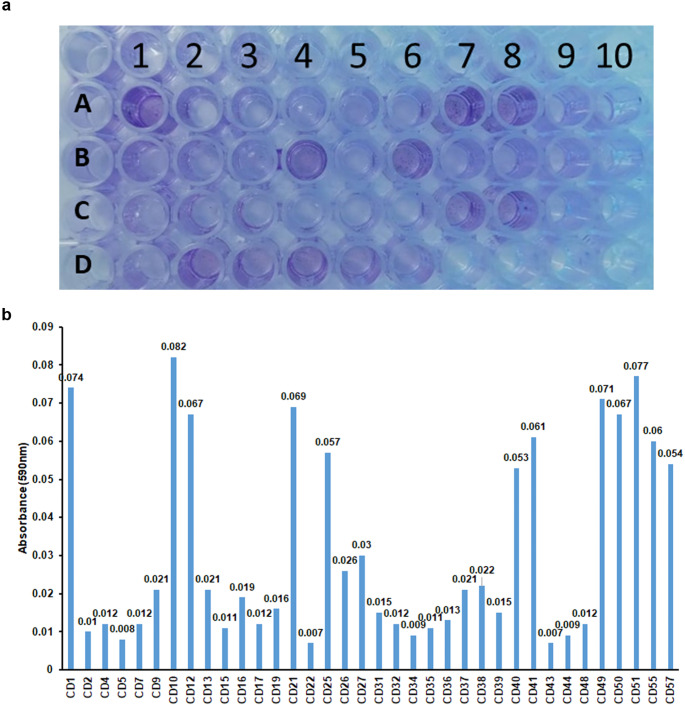

Biofilm formation capacity of C. albicans

The biofilm-forming capacity of the isolates was assessed using CV. The amount of biofilm stained was quantified at a wavelength of 590 nm. Values above 0.05 were taken as positive for strong biofilm formation (Fig. 3a, b, and Table 2). Twelve isolates-CD1, CD10, CD12, CD21, CD25, CD40, CD41, CD49, CD50, CD51, CD55, and CD57, demonstrated strong biofilm-forming capabilities (Fig. 3; Table 2). This accounted for 33.3% (12 of 36) of the tested strains. These 12 isolates were used for further characterisation.

Fig. 3.

Biofilm formation capacity of C. albicans a) Micro titre plate showing the biofilm assay of the different isolates of C. albicans. b) Graph representing the absorbance of crystal violet corresponding to biofilm formation

Table 2.

Table showing the well’s positions of C. Albicans isolates

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | CD1 | CD2 | CD4 | CD5 | CD7 | CD9 | *CD10 | *CD12 | CD13 | CD15 |

| B | CD16 | CD17 | CD19 | *CD21 | CD22 | *CD25 | CD26 | CD27 | CD31 | CD32 |

| C | CD34 | CD35 | CD36 | CD37 | CD38 | CD39 | CD40 | CD41 | CD43 | CD44 |

| D | CD48 | *CD49 | *CD50 | *CD51 | *CD55 | *CD57 |

(*- indicates well showing positive result)

Microbiological, physiological, and molecular characterization

The 12 isolates were gram-positive and showed positive results for chlamydospore formation. Among them, nine isolates (CD1,CD10,CD12,CD21,CD49,CD50,CD51,CD55, and CD57) were positive in the germ tube test. All 12 isolates also showed negative results in the urease test (S Figure S1–S4). Carbohydrate fermentation and assimilation tests were noted are tabulated. All 12 isolates fermented glucose, while none fermented lactose or sucrose (Figure S5). For carbohydrate assimilation, CD 41, CD49, and CD50 assimilated glucose, sucrose, and xylose. CD 21 assimilated sucrose and inositol, CD 25 assimilated sucrose and xylose, and CD49 assimilated glucose (Table S3 and Figure S6). Contradictory results in germ tube and carbohydrate assimilation tests necessitated sequencing for further confirmation. Following PCR amplification of 18SrRNA (Figure S7), sequencing of the genes showed that all 12 isolates were Candida albicans(Fig.4). The sequence of the isolates was submitted to NCBI, and the accession numbers of the sequence are as follows. CD1 (OQ704297), CD10( OQ704298), CD12(OQ704325), CD21(OQ704329), CD25 (OQ704331), CD40(OQ704332), CD41(OQ704333), CD49(OQ704334), CD50(OQ704340), CD51 (OQ706957), CD55(OQ706978), CD57(OQ706956).Further experiments were performed on the 12 isolates.

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of 12 C. albicans isolates

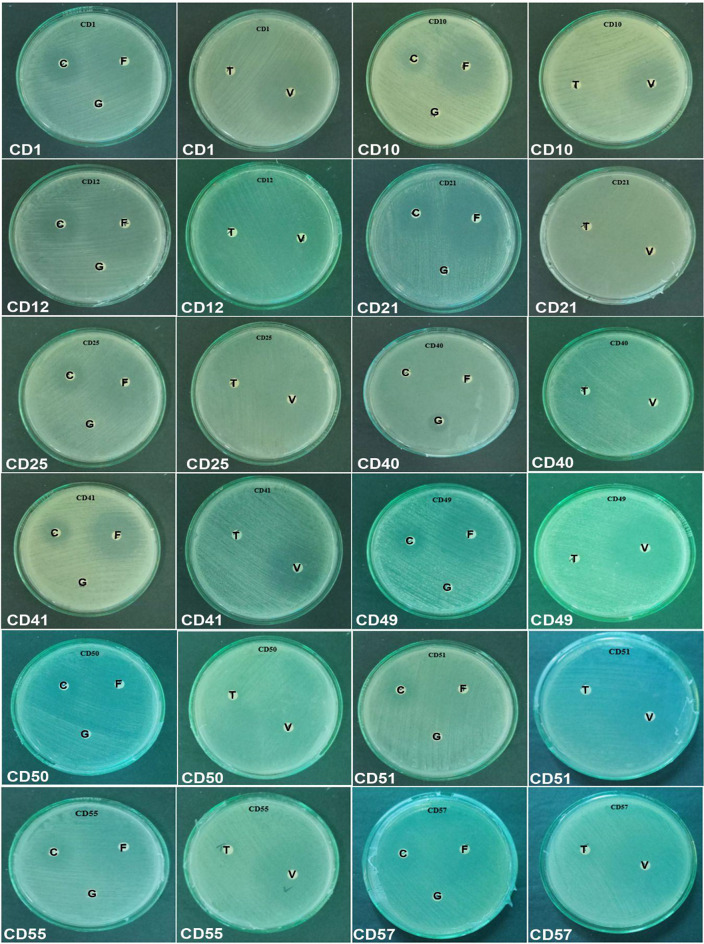

Anti-fungal susceptibility test

In vitro susceptibility testing of antifungal agents is gaining importance because of the emergence of new antifungal drugs and the detection of clinical isolates that demonstrate either inherent or acquired resistance to antibiotics. Early detection of antifungal susceptibility of Candida isolates through in vitro testing not only limits the empirical use of antifungal agents but also significantly affects treatment options for clinicians, thereby benefiting patients. Antifungal susceptibility testing was conducted on C. albicans isolates that exhibited biofilm production. The disc diffusion method was used with the following antifungal drugs: Clotrimazole, Fluconazole, Gentamicin, Terbinafine, and Voriconazole. The results revealed a range of susceptibility levels, as evidenced by the presence and size of the halos surrounding the discs. All 12 isolates tested were resistant to gentamicin, 91.6% were resistant to terbinafine, and 1 was intermediate. Among the 12 isolates, 16.67% were resistant to clotrimazole, 66.7% showed intermediate resistance, and the remaining 17% were susceptible. In terms of fluconazole, 58% of the isolates were susceptible, whereas 42% were resistant. Six of 12 (50%) isolates were susceptible to voriconazole, while the remaining 50% were resistant. Further analysis showed that Candida albicans isolate, CD 50 showed antibiotic resistance to all antibiotics (Table 3; Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Sensitivity and resistance pattern of C.albicans for antifungal drugs

| Zone diameter in mm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolates | Clo | Flu | Gen | Ter | Vor |

| CD1 | 20 - S | 29 - S | R | R | 30 - S |

| CD10 | 16 - I | 35 - S | R | R | 30 - S |

| CD12 | 18 - I | 33 - S | R | R | R |

| CD21 | 23 - S | 3 - S | R | R | R |

| CD25 | 16 - I | 33 - S | R | R | R |

| CD40 | R | R | R | 19 - I | 30 - S |

| CD41 | 18 - I | 29 - S | R | R | 30 - S |

| CD49 | 16 - I | 35 - S | R | R | 35 - S |

| CD50 | R | R | R | R | R |

| CD51 | 15 - I | R | R | R | R |

| CD55 | 15 - I | R | R | R | 30 - S |

| CD57 | 15 - I | R | R | R | R |

(S- Sensitive; I- Intermediate; R- Resistant) Clo-Clotrimazole,Flu- Fluconazole,Gen- Gentamicin,Ter-Terbinafine,Vor-Voriconazole

Fig. 5.

The Antifungal Susceptibility of C. albicans. C-Clotrimazole, F- Fluconazole, G- Gentamicin, T-Terbinafine, V-Voriconazole

Resazurin assay for susceptibility test

The resazurin assay was conducted to test antibiotic susceptibility at four different concentrations. Twelve previously selected isolates were tested for five antifungal agents. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antifungals was determined using this assay, and MIC value of 1.5 µg/ml or 2 µg/ml were obtained for various antibiotics. Among these, CD50 was the least susceptible (Table 4 and Figure S8). As both disc diffusion and resazurin assays showed that the CD50 isolate was highly resistant to all antifungal agents tested, further studies were carried out on this specific isolate.

Table 4.

Resazurin Dye Test for determining the susceptibility of antibiotics to C. albicans.

| Isolates | Clo | Flu | Gen | Ter | Vor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD1 | S | 2 µg/ml | S | S | 2 µg/ml |

| CD10 | 2 µg/ml | S | S | S | S |

| CD12 | 2 µg/ml | S | 2 µg/ml | S | 2 µg/ml |

| CD21 | S | 2 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml |

| CD25 | 2 µg/ml | S | S | 1.5 µg/ml | S |

| CD40 | 2 µg/ml | S | 2 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml |

| CD41 | S | S | S | S | 2 µg/ml |

| CD49 | S | 2 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml | S |

| CD50 | S | S | S | S | S |

| CD51 | S | S | 2 µg/ml | S | 2 µg/ml |

| CD55 | 1.5 µg/ml | S | 2 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml | 2 µg/ml |

| CD57 | S | S | S | S | S |

(S-indicates that the isolate was not susceptible for the range of antibiotics tested). Clo-Clotrimazole,Flu- Fluconazole,Gen- Gentamicin,Ter-Terbinafine,Vor-Voriconazole

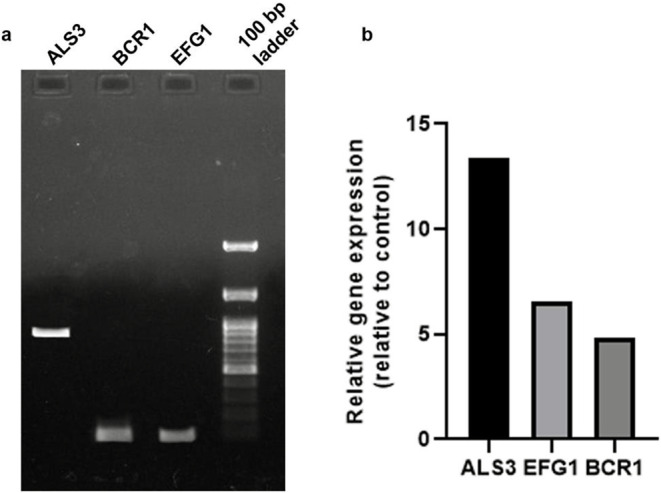

Screening for biofilm associated genes

The CD50 isolate was then analysed for the presence of biofilm- and invasion-specific genes such as ASL3, EFG1, and BCR1. All three genes were detected in the CD50 isolate (Fig. 6a). The expression of these genes in response to stress induced by the addition of a combination drug (gentamicin-miconazole) was determined. A significant increase in the relative expression of all three biofilm-associated proteins was observed compared with that in the control (Fig. 6b). Among these, ALS3 showed the greatest increase in gene expression. This suggests that targeting the ALS3 protein might help combat the resistance of C. albicans, as a reduction in biofilm formation could aid in reducing the pathogenicity of C. albicans.

Fig. 6.

Expression of biofilm-specific genes. (a) Detection of biofilm specific genes ALS3, BCR1, and EFG1 in CD50 isolate. (b) Relative gene expression of biofilm genes in CD50 compared to control, upon exposure to the gentamicin-miconazole drug combination

Discussion

Infections caused by yeasts of the genus Candida pose a significant therapeutic challenge, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems. Candidemia and related diseases are among the most severe fungal infections and are characterised by elevated rates of illness and mortality. Medically relevant species, such as C. albicans, pose a specific threat, notably in hospital environments, where they may emerge as nosocomial pathogens among chronically ill and postoperative patients. Notably, C. albicans accounted for over 80% of the isolates in all forms of human candidiasis. The present study included 57 Candida isolates from patients exhibiting clinical manifestations of candidiasis and identified C. albicans isolates among them. Recent microbiological advancements, such as CHROMagar and streamlined Candida species identification through colony appearance and colour on differential media. CHROMagar achieved species-level identification within 48 h with 100% sensitivity and specificity for Candida [32]. In the present study, 63% of the isolates were identified as C. albicans or C. dublieniensis.

Biofilms can serve as initiators or prolongers of infections by creating a protective environment that withstands treatment and enables cells to invade nearby tissue, while simultaneously establishing new infection sites concurrently [33]. In the present study, 33.3% of the isolates showed a biofilm-forming capability. Non-Candida albicans species produce significantly less biofilms than C. albicans, which is recognised for its higher pathogenicity [34]. This observation was corroborated by Kuhn et al., who confirmed that C. albicans isolates consistently displayed higher biofilm production in vitro than non-C isolates. albicans isolates [35]. Shin and co-workers found no significant correlation between biofilm production and the clinical outcome of candidemia caused by C. albicans [36]. In contrast, Tumbarello [37] reported that among infections caused by biofilm-producing isolates, only those attributed to C. albicans showed a correlation with heightened mortality rates. This suggests that the ability to form biofilms may play a crucial role in C. albicans virulence. Jain and his team [38] stated that biofilm formation is a consistent trait among Candida strains but varies significantly among clinical isolates. Among all medically significant Candida species, C. albicans is recognized as the predominant and most significant producer of biofilms [39]. In addition to their role in virulence, biofilms also confer protection against host defence mechanisms. The resistance of C. albicans biofilms to neutrophil killing is linked to glucans in the extracellular matrix, which inhibit neutrophil activation [40]. Our screening showed 33% of biofilm-forming C. albicans out of 57 samples, which further highlights the importance of investigating the relationship between biofilm formation and clinical outcomes in high-risk patient groups.

Microscopic analysis, germ tube test, and chlamydospore formation test are routine tests performed to identify C. albicans. Carbohydrate metabolism, encompassing both carbohydrate assimilation and fermentation, has been used for the identification of Candida species [41]. Sugar fermentation tests have been reported to exhibit variability and poor sensitivity [5]. Based on these findings, screening using CHROMagar was more suitable for the identification of C. albicans. The behaviour observed in the carbohydrate assimilation test in our study was not consistent with the typical characteristics of C. albicans where out of the 12 isolates, only CD41, CD49, CD50, and CD57 showed glucose assimilation. Since variations were observed with biochemical assays, confirmation of all 12 strains as C. albicans was obtained by 18 S rRNA sequencing.

Resistance to antifungal agents presents a significant challenge in the clinical setting and poses a substantial public health concern. Azoles such as fluconazole are widely prescribed as antifungal agents for both systemic and topical infections. They inhibit ergosterol biosynthesis primarily by targeting the demethylase ERG11, leading to the accumulation of toxic sterol intermediates within the fungal cell [42]. Candida albicans biofilms pose a formidable challenge owing to their inherent resistance to many antifungal drugs. For instance, traditional formulations of azoles and polyenes are largely ineffective against C. albicans biofilms. This resistance complicates treatment strategies, making infections associated with biofilms difficult to combat. In the current study, only the C. albicans isolate (CD 50) showed antibiotic resistance to all antibiotics. All 12 C. albicans isolates were resistant to gentamicin, 92% to terbinafine, 17% to clotrimazole, 42% to fluconazole, and 50% to voriconazole. CD50 also showed the least susceptibility against all antifungals tested using the Resazurin plate method. Resistance of C. albicans biofilms to standard antifungal drugs is multifactorial and complex. This is primarily attributed to three major factors: upregulated efflux pumps, the extracellular matrix, and the presence of metabolically inactive “persister” cells [40].

Identifying the key proteins involved in biofilm formation would aid in the design of potential drugs against these proteins. Exposure of the gentamicin-miconazole combination to CD50 significantly increased the expression of EFG1, BCR1, and ALS3. All of these proteins have been implicated in the pathogenesis of C. albicans. ALS3 has been reported to mimic human cadherins and thus allow their entry into host cells via endocytosis process [43]. Recently, the deletion of EFG1 in clinical isolates of C. albicans showed a considerable reduction in biofilm formation by the isolate, emphasising the paramount role of EFG1 [44].BCR1, a transcription factor, is required specifically for biofilm formation, but plays no role in the generation of hyphal structures. As a transcription factor, it regulates the expression of Als3, HYPR1, and other cell surface proteins [45].

It’s important to highlight that approaches aimed at weakening C. albicans biofilm formation or maintenance have the potential to enhance the susceptibility of the organism to conventional antifungal drugs. This possibility opens new avenues for combination therapies, where traditional antifungal drugs could be more effective when used in conjunction with drugs that target biofilm integrity.

Conclusion

A critical aspect of virulence of certain Candida species is their ability to form biofilms. This ability confers substantial resistance to antifungal therapies by restricting the penetration of substances through the matrix, shielding cells from the host immune responses, and posing a persistent threat as a potential source of infection. The lack of biofilm-specific drugs complicates treatment strategies because conventional antimicrobial agents may be less effective against biofilm-embedded pathogens. Therefore, addressing biofilm-based infections remains a complex and problematic issue in clinical practice. Our findings provide a foundation for future studies to examine the correlation between biofilm formation and treatment strategies. In our study, we observed the emergence of Candida albicans as a notable nosocomial pathogen with the capability to produce biofilms. This species is inherently resistant to commonly used antifungals. We recommend further investigation into the relationship between biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance, as well as advocating routine antifungal susceptibility testing to augment treatment effectiveness and improve patient outcomes.

Data availability

The sequence of the 12 isolates were submitted to the NCBI and can be accessed using the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article andits supplementary materials. Any further information regarding this study is available from the corresponding author, Dr.Sivasubramani Kandasamy upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abhishek M, Vidya S (2021) Determination of incidence of different Candida spp. in clinical specimens and characterisation of Candida species isolates. Indian J Microbiol Res 2021:3022 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astekar M, Bhatiya PS, Sowmya GV (2016) Prevalence and characterization of opportunistic candidal infections among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J Oral MaxillofacPathol 20(2):183–189. 10.4103/0973-029X.185913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yapar N, Uysal U, Yucesoy M, Cakir N, Yuce A (2006) Nosocomial bloodstream infections associated with Candida species in a Turkish University Hospital. Mycoses 49(2):134–138. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01187.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yesudhason BL Candida tropicalis as a Predominant Isolate from Clinical Specimens and its Antifungal Susceptibility Pattern in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Southern India. JCDR. Published online 2015. 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13460.6208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Pravin Charles MV, Kali A, Joseph NM (2015) Performance of chromogenic media for Candida in rapid presumptive identification of Candida species from clinical materials. Pharmacognosy Res 7(Suppl 1):S69–73. 10.4103/0974-8490.150528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciurea CN, Kosovski IB, Mare AD, Toma F, Pintea-Simon IA, Man A (2020) Candida and Candidiasis—Opportunism Versus pathogenicity: a review of the virulence traits. Microorganisms 8(6):857. 10.3390/microorganisms8060857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallick EM, Bergeron AC, Jones SK et al (2016) Phenotypic plasticity regulates Candida albicans interactions and virulence in the Vertebrate host. Front Microbiol 7:780. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma D, Misba L, Khan AU (2019) Antibiotics versus biofilm: an emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 8(1):76. 10.1186/s13756-019-0533-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pohl CH (2022) Recent advances and opportunities in the study of Candida albicans Polymicrobial Biofilms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12:836379. 10.3389/fcimb.2022.836379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nobile CJ, Johnson AD (2015) Candida albicans Biofilms and Human Disease. Annu Rev Microbiol 69:71–92. 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Filler SG (2011) Candida albicans Als3, a multifunctional adhesin and Invasin. Eukaryot Cell 10(2):168–173. 10.1128/EC.00279-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao X, Oh SH, Cheng G et al (2004) ALS3 and ALS8 represent a single locus that encodes a Candida albicans adhesin; functional comparisons between Als3p and Als1p. Microbiology 150(7):2415–2428. 10.1099/mic.0.26943-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nobile CJ, Fox EP, Nett JE et al (2012) A recently evolved Transcriptional Network Controls Biofilm Development in Candida albicans. Cell 148(1–2):126–138. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García-Sánchez S, Aubert S, Iraqui I, Janbon G, Ghigo JM, d’Enfert C (2004) Candida albicans Biofilms: a Developmental State Assocwithd With SpecifistableSgeneeexpressionepatternstterns. Eukaryot Cell 3(2):536–545. 10.1128/EC.3.2.536-545.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leng P, Lee PR, Wu H, Brown AJP (2001) Efg1, a Morphogenetic Regulator in Candida albicans, is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. J Bacteriol 183(13):4090–4093. 10.1128/JB.183.13.4090-4093.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernal S, Martín Mazuelos E, García M, Aller AI, Martínez MA, Gutiérrez MJ (1996) Evaluation of CHROMagar candida medium for the isolation and presumptive identification of species of candida of clinical importance. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 24(4):201–204. 10.1016/0732-8893(96)00063-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odds FC, Bernaerts R (1994) CHROMagar Candida, a new differential isolation medium for presumptive identification of clinically important Candida species. J Clin Microbiol 32(8):1923–1929. 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1923-1929.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mack D, Nedelmann M, Krokotsch A, Schwarzkopf A, Heesemann J, Laufs R (1994) Characterization of transposon mutants of biofilm-producing Staphylococcus epidermidis impaired in the accumulative phase of biofilm production: genetic identification of a hexosamine-containing polysaccharide intercellular adhesin. Infect Immun 62(8):3244–3253. 10.1128/iai.62.8.3244-3253.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Toole GA, Pratt LA, Watnick PI, Newman DK, Weaver VB, Kolter R (1999) Genetic approaches to study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol 310:91–109. 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)10008-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merritt JH, Kadouri DE, O’Toole GA (2005) Growing and analyzing static biofilms. Curr ProtocMicrobiol Chap1–Unit1B1. 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b01s00 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Chander J (2011) Opportunistic mycoses. In: Chander J, Chander J (eds) Textbook of Medical Mycology. Mehta, pp 266–290

- 22.Balish E (1973) Chlamydospore production and germ-tube formation by auxotrophs of Candida albicans. Appl Microbiol 25(4):615–620. 10.1128/am.25.4.615-620.1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devadas SM, Ballal M, Prakash PY, Hande MH, Bhat GV, Mohandas V (2017) Auxanographic Carbohydrate Assimilation Method for large scale yeast identification. J Clin Diagn Res 11(4):DC01–DC03. 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25967.9653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Society for Microbiology (2004) M44-A: Method for Antifungal Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Guideline. Vol 24

- 25.Pfaller MA, Barry AL (1994) Evaluation of a novel colorimetric broth microdilution method for antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast isolates. J Clin Microbiol 32(8):1992–1996. 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1992-1996.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K (2018) MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing platforms. Mol BiolEvol 35(6):1547–1549. 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol BiolEvol 4(4):406–425. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S (2004) Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101(30):11030–11035. 10.1073/pnas.0404206101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Synnott JM, Guida A, Mulhern-Haughey S, Higgins DG, Butler G (2010) Regulation of the hypoxic response in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 9(11):1734–1746. 10.1128/EC.00159-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng S, Chang W, Li C, Lou H (2016) Als1 and Als3 regulate the intracellular uptake of copper ions when Candida albicans biofilms are exposed to metallic copper surfaces. FEMS Yeast Res 16(3). 10.1093/femsyr/fow029 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Baradkar V, Mathur M, Kumar S (2010) Hichrom candida agar for identification of candida species. Indian J PatholMicrobiol 53(1):93. 10.4103/0377-4929.59192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fotedar R, Al-Hedaithy SSA (2003) Identification of chlamydospore‐negative Candida albicans using CHROMagar Candida medium. Mycoses 46(3–4):96–103. 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2003.00867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lohse MB, Gulati M, Johnson AD, Nobile CJ (2018) Development and regulation of single- and multi-species Candida albicans biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol 16(1):19–31. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawser SP, Douglas LJ (1994) Biofilm formation by Candida species on the surface of catheter materials in vitro. Infect Immun 62(3):915–921. 10.1128/iai.62.3.915-921.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuhn DM, Chandra J, Mukherjee PK, Ghannoum MA (2002) Comparison of biofilms formed by Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis on bioprosthetic surfaces. Infect Immun 70(2):878–888. 10.1128/IAI.70.2.878-888.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin JH, Kee SJ, Shin MG et al (2002) Biofilm production by isolates of Candida species recovered from nonneutropenic patients: comparison of bloodstream isolates with isolates from other sources. J Clin Microbiol 40(4):1244–1248. 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1244-1248.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tumbarello M, Posteraro B, Trecarichi EM et al (2007) Biofilm production by Candida species and inadequate antifungal therapy as predictors of mortality for patients with candidemia. J Clin Microbiol 45(6):1843–1850. 10.1128/JCM.00131-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jain N, Kohli R, Cook E, Gialanella P, Chang T, Fries BC (2007) Biofilm formation by and antifungal susceptibility of Candida isolates from urine. Appl Environ Microbiol 73(6):1697–1703. 10.1128/AEM.02439-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malinovská Z, Čonková E, Váczi P (2023) Biofilm formation in medically important Candida Species. J Fungi (Basel) 9(10):955. 10.3390/jof9100955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gulati M, Nobile CJ (2016) Candida albicans biofilms: development, regulation, and molecular mechanisms. Microbes Infect 18(5):310–321. 10.1016/j.micinf.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chander J (2002) A Textbook of Medical Mycology, 2 edn. ed.). Mehta, p 227

- 42.Kane A, Carter DA (2022) Augmenting Azoles with Drug Synergy to Expand the Antifungal Toolbox. Pharmaceuticals 15(4). 10.3390/ph15040482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Phan QT, Myers CL, Fu Y et al (2007) Als3 Is a Candida albicans Invasin That Binds to Cadherins and Induces Endocytosis by Host Cells. Heitman J, ed. PLoS Biol.;5(3):e64. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Huang MY, Woolford CA, May G, McManus CJ, Mitchell AP (2019) Circuit diversification in a biofilm regulatory network. Lin X, ed. PLoS Pathog.;15(5):e1007787. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Cavalheiro M, Teixeira MC (2018) Candida Biofilms: threats, challenges, and promising strategies. Front Med 5:28. 10.3389/fmed.2018.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The sequence of the 12 isolates were submitted to the NCBI and can be accessed using the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article andits supplementary materials. Any further information regarding this study is available from the corresponding author, Dr.Sivasubramani Kandasamy upon reasonable request.