Abstract

Biofilms are bacterial communities surrounded by a polymeric matrix that can form on implanted materials and biotic surfaces, resulting in chronic infection that is recalcitrant to immune- and antibiotic-mediated clearance. Therefore, biofilm infections present a substantial clinical challenge, as treatment often involves additional surgical interventions to remove the biofilm nidus, prolonged antimicrobial therapy to clear residual bacteria, and considerable risk of treatment failure or infection recurrence. These factors, combined with progressive increases in antimicrobial resistance, highlight the need for alternative therapeutic strategies to circumvent undue morbidity, mortality, and resource strain on the healthcare system resulting from biofilm infections. One promising option is reprogramming dysfunctional immune responses elicited by biofilm. Here, we review the literature describing immune responses to biofilm infection with a focus on targets or strategies ripe for clinical translation. This represents a complex and dynamic challenge, with context-dependent host-pathogen interactions that differ across infection models, microenvironments, and individuals. Nevertheless, consistencies among these variables exist, which could facilitate the development of immune-based strategies for the future treatment of biofilm infections.

Keywords: Biofilm, Immunology, Granulocytes, Immunometabolism, Bioengineering, Infection

1. Introduction

Despite the advent of modern aseptic techniques, surgical site infections (SSIs) remain a relatively common postoperative complication, with an estimated incidence of 2.5% worldwide [1]. When compounded with estimates of per capita lifetime surgical procedures (5.97–9.17) [2], the significant burden of SSIs becomes apparent, with 15–23% of individuals likely to experience at least one postoperative infection in their lifetimes. Currently, many of these infections can be managed using various antimicrobial regimens; however, rising rates of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threaten the long-term viability of this strategy. Approximately 4.71 million deaths are attributed to AMR yearly, which is projected to rise to 8.22 million by 2050 [3]. Other factors complicating SSI treatment can include delayed symptom presentation, unreliable or lengthy culture periods to identify pathogenic species, sample contamination by skin flora, and non-specific clinical scores/indices that limit rapid and accurate infectious diagnoses [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8]]. In some cases, SSIs may not be identified in patients until months following their initial procedure [9]. These facts have inspired renewed interest in developing alternative therapeutic strategies to prevent and/or treat existing infections, such as immune modulation, to relieve pressure on antibiotics as the current sole tool to treat these devastating infections. An added benefit of a dual pronged approach (i.e., immune targeting and antibiotics) is that bacteria would need to circumvent two modes of attack, minimizing concerns about the development of rapid AMR that has plagued antibiotics shortly after they come into clinical use [10].

Therapeutic advances are urgently needed to mitigate SSIs that proceed to biofilm, which forms on implanted medical devices and biotic surfaces such as bone [[11], [12], [13]]. Clinically, these infections are exceedingly difficult to manage and are established with a low infectious inoculum [[14], [15], [16]], resulting in pathology that is recalcitrant to both antibiotics and immune-mediated clearance [12,13]. The current standard of care typically involves additional surgery to explant the biofilm nidus, debridement of affected tissues to disrupt remaining biofilm, and prolonged antibiotic therapy to safeguard against recurrence. Nevertheless, treatment failure rates can be appreciably high (10–25%) [[17], [18], [19], [20]], resulting in protracted morbidity and elevated mortality for patients that places a significant resource stress on the medical system [17].

As mentioned, biofilms are recalcitrant to antibiotics and immune antimicrobial activity. The former is at least partially linked to the formation of bacterial subpopulations termed ‘persister cells’ that are less metabolically active, which circumvents antibiotics that target cell wall and protein synthesis associated with rapidly dividing bacteria [21]. Therefore, even biofilms formed by bacteria that do not harbor genetic antibiotic resistance are largely recalcitrant to this treatment option. The mechanics of biofilm development have been summarized extensively elsewhere [13] and are beyond the scope of this review. Still, considerable work has been done to elucidate and target bacterial elements responsible for biofilm formation, with some success [[22], [23], [24], [25]]. However, these findings have not yet been translated into clinical efficacy, and difficulties with vaccine development against biofilm-forming species such as Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), despite the completion of >30 clinical trials, draw into question when, or if, this approach will become viable [[26], [27], [28], [29]]. Comparatively less attention has been paid to the immune response to biofilm infection. However, work from our laboratory and others has identified multiple examples of immune dysfunction during S. aureus biofilm infection, a common cause of SSIs [30,31]. Here, we review mechanisms of immune dysfunction during biofilm infection through the lens of well-characterized biofilm models (prosthetic joint, catheter/shunt, and craniotomy infection) and translational research on their clinical counterparts. Additionally, we discuss strategies to reverse immune system dysfunction, which may be fertile ground for developing novel therapies in the future.

2. Immune responses elicited by biofilm vs. non-biofilm infections: a brief overview

In general, planktonic (i.e., non-biofilm) infections elicit a rapid neutrophil (PMN) response and proinflammatory macrophage activation, both of which exert potent bactericidal activity to clear infection [32,33]. In many cases, Th1 and Th17 cells are also recruited to potentiate phagocyte activation and establish memory populations for a rapid response in the case of re-infection [[34], [35], [36]]. In contrast, biofilm infections are generally typified by macrophages that are polarized to an anti-inflammatory phenotype and, although PMNs are also observed, they are not capable of clearing infection [[37], [38], [39], [40], [41]]. Furthermore, many biofilm infections, such as those caused by S. aureus, result in the accumulation of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (G-MDSCs) that exhibit potent anti-inflammatory properties by their ability to inhibit T cell activation, monocyte/macrophage proinflammatory activity, and PMN bactericidal activity [9,11,15,42,43]. However, it is important to note that in vivo, biofilm infection is likely typified by organisms in both biofilm and planktonic growth states, since bacteria can disperse and disseminate from the biofilm [13] to seed new sites of infection. Therefore, it is plausible that biofilms share some degree of immune reactivity with planktonic infections; however, this can only prevent bacterial outgrowth at best, since by nature biofilms are not cleared by the immune system.

3. Major considerations for host-biofilm interactions

The immune response to biofilm infection is complex. Most work to date has examined innate immunity, where PMN, G-MDSC, and macrophage responses to biofilm are the most well-understood. More recent studies from our group have also identified a significant role for CD4+ T cells in coordinating the innate immune response during S. aureus craniotomy infection [44], which is discussed later. Work has also investigated the complement system in the context of biofilm formed during central nervous system (CNS) shunt infection [[45], [46], [47], [48]], in addition to immune interference from tissue damage sustained during surgery that provides a favorable environment for biofilm formation [49]. These aspects of immune-pathogen interactions during biofilm infection are summarized in Table 1 and discussed in the following sections.

Table 1.

Overview of select immune components with roles in biofilm immunity.

| Immune Component | Role in Biofilm Immunity | References |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | Mixed, likely beneficial. Granulocyte depletion worsens craniotomy but improves PJI [15,50]. Given their ability to infiltrate biofilm and antimicrobial capabilities [51], it is likely mature neutrophils are effective at containing biofilm, especially in infections where they may not acquire G-MDSC characteristics (i.e. CSF shunt) [52,53,54]. However, despite evidence for neutrophil activity, this is not capable of clearing biofilm. | [15,51,50,52,53,54] |

| Granulocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells | Detrimental. These pathologically activated granulocytes possess multiple immunosuppressive features and may arise from neutrophils in response to biofilm contact at the site of infection. | [9,15,39,42,55,50,56,57] |

| Macrophages | Mixed, likely ineffective. Macrophages exhibit anti-inflammatory gene signatures during biofilm infection and are unable to penetrate the biofilm structure [58] due, in part, to heightened susceptibility to bacterial toxins [59]. However, therapeutic targeting of macrophages by metabolic reprogramming [38] and inclusion in 3D printed scaffolds reduces biofilm burden [60]. | [9,37,38,40,41,47,60,52,58,59,61] |

| CD4+T cells | Beneficial. There are mixed findings regarding productive Th subsets in the literature that may be context-dependent. Evidence suggests Th1 and Th17 cells are beneficial [44] while other studies suggest they are detrimental, where Treg and Th2 cells are instead identified as productive subsets [62]. There is some evidence of T cell senescence and dysfunction during craniotomy infection [9]. | [9,44,62] |

| Complement | Unclear. May serve as a biomarker for CSF shunt infection, but genetic deletion of C3 or C5 did not alter the course of infection. Functional relevance is unknown, especially in other biofilm infection models. | [46,47,54,63,64] |

3.1. Granulocyte plasticity influences biofilm infection

Granulocytes are often the first leukocytes considered in the context of bacterial infections. Granulocytes include basophils, eosinophils, mast cells, and PMNs which are characterized by cytoplasmic granule composition and nuclear morphology [65]. For the purposes of this review, PMNs are the most relevant cell type in this group. PMNs are produced in the bone marrow and represent the most abundant leukocyte subset in human blood [51]. Intended for rapid antimicrobial action, PMNs have fewer mitochondria, reduced mRNA levels, and abbreviated lifespans in circulation relative to other leukocyte populations [51,66], which can complicate transcriptomic and metabolic analyses if not accounted for. For these reasons, PMNs were historically considered functionally restricted monoliths only capable of executing preprogrammed activities without significant functional shifts in response to environmental or cellular factors. However, enhanced ‘-omics’ workflows have revealed this is not the case. Instead, PMNs are functionally heterogeneous with many distinct subpopulations in circulation [67] and during pathologies such as malignancy [66] or infection [9,68]. Additionally, PMNs in the blood are epigenetically, transcriptionally, and functionally distinct from those infiltrating infected tissues [9,68,69] and respond uniquely in different tissue microenvironments [70]. Therefore, PMNs are complex players in the antimicrobial immune response.

Recent evidence suggests that granulocyte plasticity may be co-opted by biofilm to program an anti-inflammatory phenotype that promotes bacterial survival at the expense of the host. This was first noted by Heim et al. using a mouse model of prosthetic joint infection (PJI) with bona fide biofilm formation on the infected implant confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [15]. In this model, 70–75 % of infiltrates at the site of biofilm infection were classified as CD11b+Gr-1+ cells. However, since Gr-1 detects both Ly6G and Ly6C, subsequent studies assessing each antigen identified that a subset of Ly6G+Ly6C+ granulocytes were capable of suppressing T cell proliferation and proinflammatory cytokine production [15]. This contrasted with other less abundant infiltrates, namely PMNs and monocytes, as well as blood granulocytes, which did not exhibit immunosuppressive activity. Further, depletion of Ly6G+ granulocytes significantly reduced bacterial burdens during PJI while augmenting monocyte proinflammatory activity. Although Ly6G depletion eliminated both G-MDSCs and PMNs, the beneficial effects observed were interpreted as G-MDSCs having a dominant effect on preventing bacterial clearance. When both granulocytes and monocytes were depleted using anti-Gr-1+ this dramatically worsened infection, revealing a role for monocyte antibacterial activity in reducing S. aureus burden in the absence of anti-inflammatory G-MDSCs. This was the first evidence linking MDSCs to the deleterious immune response during biofilm infection [15]. MDSCs are reviewed in more detail in the following section with an expanded discussion about their roles in other S. aureus infection models.

3.1.1. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

MDSCs are pathologically activated myeloid cells with immunosuppressive features such as heightened production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., IL-10), inhibition of T cell proliferation mediated by inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), arginase-1 (Arg-1), and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) among others, and suppression of PMN bactericidal activity [[71], [72], [73]]. MDSCs are generally divided into two broad classes: monocytic or M-MDSCs and granulocytic or G-MDSCs (also referred to as PMN-MDSCs) that have been associated with numerous infectious and non-infectious pathologies [71,72,74]. Heim et al. would later refine the initial description of MDSC infiltrates during PJI as G-MDSCs, which were transcriptionally similar to, yet distinct from, PMNs and could be discriminated from peripheral blood PMNs by elevated CD11b expression [43]. As such, these cells are referred to as G-MDSCs throughout this review, although earlier literature reports them as MDSCs. G-MDSCs are also detected in infected tissues during human PJI [55] and the relative lack of these cells in the peripheral blood and during sterile arthroplasty in both mice [42] and humans [55,75] suggest that the infectious milieu is responsible for programming this anti-inflammatory phenotype. Underscoring this point, even PMN and monocyte infiltrates acquired suppressive activity (as indicated by T cell suppression assays) at later intervals during PJI [43], whereas G-MDSCs possessed inhibitory activity at all time points.

Recent studies have also explored G-MDSC action during S. aureus craniotomy infection, where biofilm forms on a skull segment that is briefly explanted to access the intracranial space for numerous indications including tumor resection, evacuation of brain bleeds, or implantation of medical devices [9,11]. Similar to PJI, G-MDSCs are abundant in tissues from mouse [60,50] and human craniotomy infection [9] but are absent in peripheral blood, supporting the idea that signals in the biofilm milieu likely play a critical role in programming G-MDSC development. Interestingly, Ly6G depletion during craniotomy infection led to increased bacterial burden [50], opposite to PJI [15]. This underscores that, while aspects of the immune response to biofilm infection may be conserved across infectious modalities, site-specific factors can play a significant role in dictating pathology. Indeed, recent studies comparing transcriptional profiles of granulocytes recovered from craniotomy vs. PJI revealed that granulocytes associated with PJI are significantly more G-MDSC-like than those found during craniotomy infection as determined by expression of G-MDSC marker genes obtained from published datasets [70]. Therefore, since anti-Ly6G targets both PMNs and G-MDSCs, granulocyte depletion during craniotomy infection also removed bactericidal PMNs, which presumably outweighed G-MDSC action. Indeed, G-MDSCs have been shown to inhibit PMN killing of S. aureus [50], so a balance between these cell types is likely at play; however, this remains difficult to directly assess since no unique markers have been identified to specifically target each population. Collectively, G-MDSCs are abundant in two distinct models of S. aureus biofilm infection and influence subsequent immune responses. In addition to biofilm, a growing list of S. aureus infections have been linked with MDSCs [71,76], including sepsis [77] and skin and soft tissue infection [78,79]. One outstanding question pertains to the signal(s) that promote G-MDSC anti-inflammatory activity and how this is shaped by the biofilm environment.

3.2. Soluble factors regulating immunity during biofilm infection

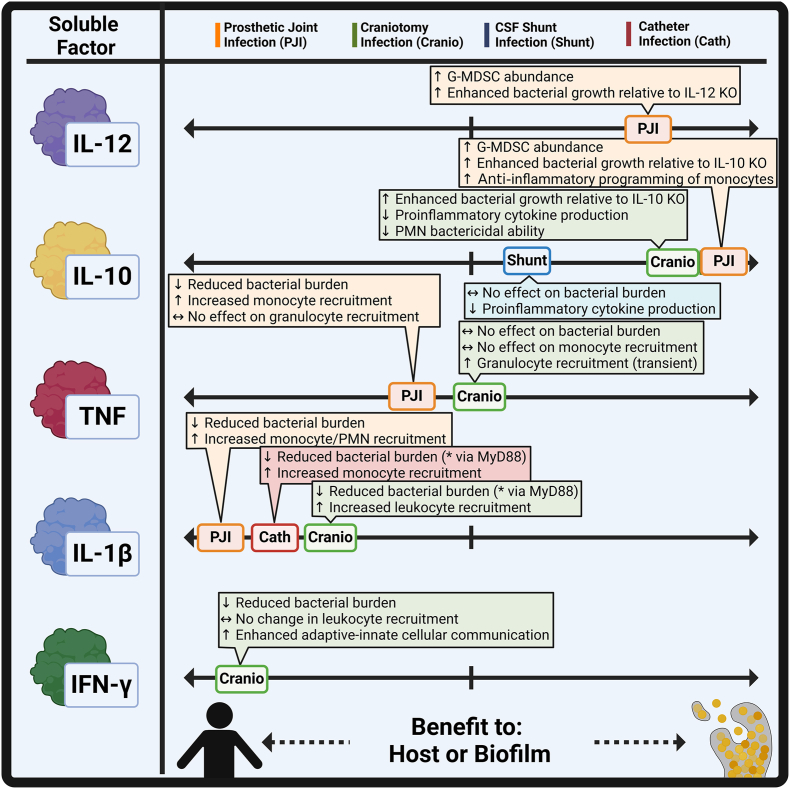

Several cytokines have been explored in the context of biofilm infection with divergent roles (Fig. 1), which are discussed below.

Fig. 1.

Cytokine production benefits both the biofilm and host during infection. Various cytokines, including IL-12, IL-10, TNF, IL-1β, and IFN-γ, exert differential effects in the context of biofilm infection. Created in BioRender. Van Roy, Z. (2025) https://BioRender.com/k53z680.

3.2.1. IL-12

IL-12 was the first mediator described to influence G-MDSC abundance in the context of PJI [62], where prior work reported its stimulatory effect on MDSCs, primarily in cancer models [80,81]. In PJI, IL-12 deficiency significantly reduced G-MDSCs at the site of infection coinciding with less biofilm burden; however, the G-MDSCs that remained retained suppressive activity, indicating that IL-12 likely influences G-MDSC expansion but not function during S. aureus PJI [42]. Interestingly, because G-MDSCs are absent in the blood or tissues following sham arthroplasty [42,55,75] and PMN recruitment was increased with IL-12 loss, this raises the possibility that IL-12 may promote the potential acquisition of G-MDSC characteristics in PMNs at the site of PJI, as opposed to recruiting G-MDSCs. The apparent negative effects of IL-12 on PJI outcome are surprising given its proinflammatory properties which promote Th1 polarization and associated macrophage activation [82]. A recent study reported that IL-12α can exert anti-inflammatory effects in human PBMCs [83] and IL-12 loss exacerbates collagen-induced arthritis in mice [84]; however, the potential of anti-inflammatory effects of IL-12 in the context of PJI remains to be determined. Subsequent studies in PJI [85] and craniotomy infection [9,50] revealed transcriptional evidence of a PMN to G-MDSC transition using scRNA-seq trajectory analysis, suggesting that G-MDSCs may originate from blood PMNs although more work is needed to address this possibility.

3.2.2. IL-10

IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine linked to G-MDSC function [71], was mainly produced by G-MDSCs during S. aureus PJI compared to other leukocyte infiltrates [39]. IL-10 deficiency decreased both G-MDSC abundance and bacterial burden at the site of infection, which was reversed upon adoptive transfer of wild type (WT) G-MDSCs. The loss of IL-10 resulted in heightened proinflammatory (iNOS, IL1b, IL12p40, and TNF) and depressed anti-inflammatory (Arg1) transcriptional profiles in monocytes [39], indicating that G-MDSCs are deleterious during PJI, partly due to IL-10-mediated reprogramming of monocyte activity towards an anti-inflammatory state. Similar findings were observed during craniotomy infection [16], where granulocytes (G-MDSCs and PMNs) were the primary source of IL-10. Global IL-10 loss reduced bacterial burden during S. aureus craniotomy infection [86] that was recapitulated in granulocyte-specific IL-10 conditional knockout (KO) mice, where exogenous IL-10 delivered by a microparticle formulation restored bacterial counts to WT levels. IL-10 production was also found to inhibit PMN antibacterial activity and proinflammatory mediator production, in particular tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [86], indicative of anti-inflammatory programming. Finally, IL-10 effects have been explored in a third biofilm infection model, namely cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunt infection with Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) [87], which is typified by macrophage and Ly6G+ granulocyte infiltrates [52]. The potential delineation between PMNs and G-MDSCs was not explored in this study since it predated the first report of G-MDSCs in biofilm infection [15]. Interestingly, while IL-10 production was enhanced during S. epidermidis CNS shunt infection relative to sham mice, IL-10 deficiency had no effect on bacterial burden [53]. It did, however, result in heightened proinflammatory cytokine production and increased weight loss. The reason for the disconnect between bacterial burden and inflammatory mediator expression was not explored further; however, a few possibilities exist, given the context of findings in biofilm models from other groups. First, IL-10 production was only transiently elevated during acute infection, with no differences at later intervals [53]. Given that G-MDSCs are a primary source of IL-10 during craniotomy and PJI, the minor elevations in IL-10 would suggest that G-MDSCs are not abundant in CSF shunt infection, although this remains speculative. Second, given that the CSF shunt model utilized S. epidermidis biofilm instead of S. aureus as was examined in craniotomy and PJI, this discrepancy may be explained by S. aureus-specific factors that uniquely promote IL-10 production, which is supported by the literature [56] and will be discussed in a later section of this review. Subsequent work uncovered distinct metabolic programming in human macrophages treated with IL-10 [88], including decreases in glycolytic intermediates indicative of an anti-inflammatory state [[89], [90], [91]]. However, IL-10 polarized macrophages enhanced biofilm formation in vitro and induced the expression of a distinct set of bacterial genes for intracellular survival [88]. Thus, IL-10 treatment not only modulates host responses, but bacteria respond in kind to this altered phenotypic state. Nonetheless, in multiple models of biofilm infection, IL-10 is a key component of the counterproductive granulocyte response to infection, although this may be context- and site-dependent.

Given its importance in multiple models of biofilm infection, an obvious potential therapeutic strategy may involve modulating IL-10 activity. Such a therapy would likely need to be locally administered, given the importance of IL-10 in maintaining mucosal immunity, a consideration highlighted by the spontaneous development of irritable bowel disease in IL-10 KO mice [92]. An interesting avenue for IL-10 targeted therapy is epigenetic regulation. Our group [56,93] and others [92,[94], [95], [96]] have linked two epigenetic systems to IL-10 production, namely histone acetylation (activating) and DNA methylation (repressive). In the case of the former, HDAC6 and HDAC11 opposingly regulate IL-10 levels in G-MDSCs in response to S. aureus biofilm [94], however, HDAC1 and HDAC2 can also augment IL-10 production [93]. While selectively regulating IL-10 is a plausible treatment strategy given the numerous HDAC inhibitors developed and in clinical use [[97], [98], [99], [100], [101]], histone acetylation also regulates the production of numerous other cytokines during infection, some of which are proinflammatory. For example, global HDAC inhibition increased infectious burdens during craniotomy infection likely influenced by the widespread reduction in inflammatory mediator production [93], highlighting the fact that although this biofilm infection is chronic, there is a degree of proinflammatory activation that is essential for preventing bacterial outgrowth. Given this, DNA methylation may be another target for consideration. This process is catalyzed by a group of enzymes called DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), and while now recognized as an active and reversible process, DNA methylation is considered one of the more stable epigenetic modifications. DNMT3a has been linked to MDSC function in various pathologies [[102], [103], [104]] and regulates IL-10 production during S. aureus infection [105]. Therefore, targeted modulation of Il10 promoter methylation, perhaps with a modified CRISPR-targeted epigenetic editing approach [106], may help abrogate the negative effect of G-MDSC action during biofilm infection. Further, if the epigenetic steps facilitating G-MDSC development from their precursor population were identified, this could be leveraged to prevent their emergence in the first place. While an exciting possibility, there is still much work to be done before this becomes a viable option, and other factors besides IL-10 contribute to the chronicity of biofilm infection, as evident from the lack of biofilm clearance with IL-10 deficiency in the models discussed above [39,86,53].

3.2.3. TNF

TNF is a prototypical proinflammatory cytokine produced in response to tissue damage or infection [107,108] and is present at the site of biofilm infection [[109], [110], [111]]. TNF exerts beneficial effects in a number of infections, including S. aureus sepsis [112], brain abscess [113,114], and skin abscess [115], as well as Listeria monocytogenes infection [116], to name a few. TNF has also been reported to be protective during S. aureus PJI [109], where it promoted monocyte recruitment to the site of infection with no effect on granulocyte abundance. Curiously, opposite results were found during S. aureus craniotomy infection, where bacterial burden and monocyte recruitment were unaffected by TNF deficiency [111]. Instead, granulocyte recruitment was significantly reduced between days 7–14 post-infection but rebounded to WT levels by day 28. Further analysis revealed that granulocytes upregulated lymphotoxin-α (LTA) expression to potentially compensate for TNF deficiency, as LTA can bind TNFR1 and TNFR2 [107]. Deletions in either receptor identified some functional losses in granulocyte activity, supporting this possibility; however, bacterial burdens remained unchanged. Prior work in S. aureus PJI revealed that loss of both IL-1β and TNF led to more severe pathology than either cytokine alone, with IL-1β playing a more dominant role [109]. Therefore, in contrast to planktonic infection [[112], [113], [114], [115]], current evidence suggests that TNF plays a more nuanced role in response to S. aureus biofilm. In support of this, TNF induces neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [115], which are inefficient at clearing biofilm [117], dispensable during craniotomy infection [111], and may even contribute to biofilm structure [118]. However, it remains possible that TNF levels are insufficient in the biofilm milieu to overcome the cellular anti-inflammatory bias. In this case, exogenous delivery of TNF or receptor agonism may be a potential treatment strategy, which has shown efficacy in non-biofilm models [115]. However, this possibility remains speculative and warrants further investigation.

3.2.4. IL-1β

As mentioned above, IL-1β deficiency worsens PJI and impairs monocyte and PMN recruitment, especially in the context of TNF deficiency [109]. The reason for this additive effect may be explained, in part, by the signaling pathways for each cytokine. TNF signaling is complex but primarily acts in a NF-κB-dependent manner along with MAP kinase activation [119]. IL-1β also signals through NF-κB and MAP kinase activation, but does so via the adaptor protein MyD88, which transmits pathogen-associated signals from receptors on the cell surface to downstream proteins involved in coordinating the immune response [120,121]. The muted effect of TNF loss on bacterial burden during PJI and lack of effect during craniotomy infection suggest that MyD88-dependent pathways may be more critical for immune responses to biofilm. This is supported by findings where MyD88 deficiency worsened pathology in multiple biofilm models including craniotomy [16] and catheter infection [58], and in some cases was associated with increased mortality [16]. In a mouse model of subcutaneous catheter infection where biofilm forms on the implant surface [41,122,123], MyD88 KO animals displayed elevated S. aureus burden on the catheter that disseminated to peripheral sites concomitant with an enhanced fibrotic response [58]. This was associated with impaired macrophage recruitment that displayed an anti-inflammatory transcriptional profile. During craniotomy infection, MyD88 KO mice exhibited similar trends with increased bacterial burden and less leukocyte recruitment [16]. Both results corroborate findings with IL-1β deficient animals following PJI as discussed above, where monocyte influx was also reduced that translated to elevated bacterial burden [109], given the ability of IL-1β to signal through MyD88. Proinflammatory macrophages polarized with TNF or IFN-γ were able to phagocytose biofilm and, when injected at the site of catheter infection, markedly reduced S. aureus burden to a greater extent than non-polarized cells. This approach remained efficacious even when delayed until 7- or 9-days post-infection, establishing the activity of proinflammatory macrophages against biofilm [40]. MyD88 KO macrophages had no effect in this treatment paradigm, in agreement with their skewing towards an anti-inflammatory state and poor antimicrobial activity against biofilm. IL-1β is produced in an inactive form that requires cleavage by the caspase-1 inflammasome for activity [124]. Studies in the craniotomy model have shown a beneficial role for IL-1β in bacterial containment, where S. aureus burdens were significantly higher in caspase-1-deficient mice that was reversed following exogenous IL-1β delivery by microparticles [125]. Therefore MyD88-targeted therapies, such as those that may employ IL-1β, would likely have strong footing for efficacy in reprogramming the anti-inflammatory biofilm milieu, especially in the context of macrophage biology, and may be an effective strategy for future translation.

3.2.5. IFN-γ

IFN-γ is another cytokine that has recently been shown to influence the immune response to biofilm in the context of craniotomy infection. Infiltrating T cells preferentially acquired a Th1 phenotype, which is associated with cell-mediated immunity, heightened activity against intracellular bacteria and viruses, and was critical for eliciting strong IFN-γ-dependent gene signatures in innate immune cells [36,44]. The mechanism behind this Th1 bias is unclear, however several groups have identified staphylococcal toxins as potent inducers of IFN-γ, including staphylococcal enterotoxin A [126] (SEA), staphylococcal enterotoxin B [127] (SEB), alpha-toxin [128], and protein A (Spa) [129]. Given that S. aureus biofilms produce elevated levels of virulence factors [130], this may account, in part, for preferential Th1 skewing during biofilm infection, although this remains speculative. Exaggerated bacterial burdens were observed during IFN-γ deficiency, confirming the importance of this cytokine for S. aureus containment. Subsequent work supported this observation, where Ifngr1-deficient mice also displayed elevated bacterial burdens without alterations in immune cell recruitment [131]. Granulocyte- or macrophage/microglia-specific deficiency in Ifngr1 did not recapitulate phenotypes observed with global KO mice, suggesting the combined action of IFN-γ on several immune populations. Ifngr1 KO displayed a decreased Th1/Th17 ratio and abrogated cellular crosstalk between Th cells and various innate immune cell populations. Similar studies are needed to establish a definitive role for IFN-γ in other biofilm models; however, initial findings support a role for Th1 cytokines in promoting antibacterial responses to biofilm.

Collectively, although current evidence has uncovered a functional role for many proinflammatory cytokines in regulating the immune response to biofilm it is important to note that none of these are successful at eradicating infection. This fact highlights the challenge that future immune modulatory strategies will have to overcome.

3.3. Immunometabolism: A double-edged sword

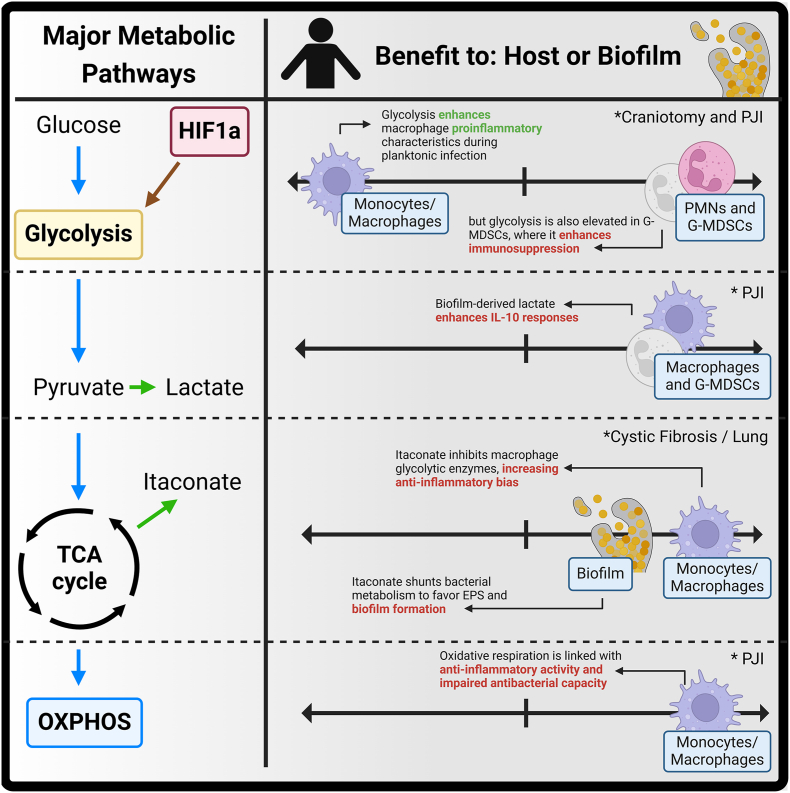

3.3.1. Glycolysis and HIF1a in granulocytes

In recent years, metabolism has emerged as a critical determinant of immune cell function [91,132,133] (Fig. 2). Alterations in glycolytic flux have been linked to MDSC function in general [134,135] and during biofilm infection, first in mouse models and patient samples during PJI [85] and later in craniotomy infection [110]. During PJI, granulocytes were transcriptionally biased towards glycolysis, in both in the mouse model and human subjects [85]. More detailed analysis revealed a higher glycolytic bias in G-MDSCs, whereas PMNs favored fatty acid metabolism and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) that generates reducing equivalents to fuel reactive oxygen species (ROS) production via NOX2 [136]. Glycolytic flux was also linked to functional activity, as inhibiting glycolysis reduced mitochondrial ROS and H2O2 production by G-MDSCs, both of which are linked to immunosuppressive properties [71,137]. Attenuating glycolysis in vivo negated G-MDSC T cell suppressive activity, which translated into less biofilm burden. Subsequent transcriptional analysis validated the idea that attenuating granulocyte glycolysis translated to heightened proinflammatory signatures. Furthermore, animals that lacked Hif1a in granulocytes displayed similar phenotypes, stemming from the ability of HIF1a to augment glycolysis. During craniotomy infection [110], G-MDSCs from both mice and human subjects displayed marked upregulation of glycolysis and ROS transcriptional pathways [110,138]. These results highlight that during biofilm infection, granulocyte glycolysis is associated with anti-inflammatory activity given the fact that most infiltrating granulocytes are G-MDSCs. This contrasts with macrophages, where glycolysis is typically linked to proinflammatory characteristics, whereas oxidative metabolism programs anti-inflammatory activity [90,135]. Interestingly, although G-MDSC infiltrates during craniotomy [110] or PJI [43,85] exhibited a glycolytic bias, they also expressed numerous proinflammatory genes at higher levels than PMNs at the site of biofilm infection. This may represent a positive feedback loop to augment G-MDSCs [15,55,50], given the fact that growth factors and proinflammatory cytokines have been shown to promote MDSC expansion and activation. Nevertheless, these results highlight the complexity in PMNs and G-MDSCs and that the line between pro- and anti-inflammatory activity can be blurred. These cells likely represent two distinct activation states of the same lineage, a concept that is currently supported by the field [139,140]. Extending this idea further, the heightened glycolytic profile of G-MDSCs combined with increased proinflammatory cytokines at the site of biofilm infection may reflect a potential ‘safeguard’ program in granulocyte biology, where excessive proinflammatory stimuli may feedback to induce compensatory anti-inflammatory programming to limit tissue damage and prevent aberrant inflammation.

Fig. 2.

Overview of metabolic pathways that influence leukocyte-pathogen crosstalk during biofilm infection. Summary of major metabolic pathways that influence immune cell responsiveness to biofilm. Created in BioRender. Van Roy, Z. (2025) https://BioRender.com/v93m458.

The transcription factor HIF1a has been shown to regulate the immune response to biofilm infection and likely contributes to glycolytic programming in granulocytes. HIF1a is a master regulator of the cellular response to hypoxia, which augments glycolytic enzyme gene expression and other responses that play an integral role in immune function [133]. In PJI, HIF1a was linked to G-MDSC function, as HIF pathways were enriched in G-MDSCs vs. PMNs, and granulocyte-specific deletion of HIF1a decreased bacterial burden and enhanced proinflammatory signatures, reminiscent of phenotypes when G-MDSC abundance is reduced in experimental models [39,42]. Granulocytes also upregulated HIF1a at the site of craniotomy infection, that again was most robust in G-MDSCs [110]. However, in contrast to PJI, HIF1a inhibition did not alter biofilm burden during acute intervals. Instead, HIF1a controlled chemokine production and leukocyte recruitment, since mice treated with a HIF1a inhibitor displayed heightened levels of both that led to microabscess formation. Since HIF1a regulates the expression of hundreds of genes [141], it is possible that HIF1a may be one factor responsible for promoting the G-MDSC phenotype during biofilm infection. Additional research is needed to explore this possibility and how hypoxia influences this response.

3.3.2. Metabolic reprogramming of monocytes/macrophages

Monocytes are another key component of the innate immune response to S. aureus and differentiate into macrophages following migration to sites of infection [11]. In several models of biofilm infection [15,16,41,50,52] as well as available data on human subjects [9,55], monocytes/macrophages are the second most abundant infiltrate after granulocytes. Because monocytes have a longer half-life than granulocytes (>4 days vs. ∼12–24 h, respectively) [40,51] this allows for a potential greater influence on the inflammatory milieu. However, this could represent a double-edged sword, as macrophages can achieve alternative activation states that affect their characteristics and the biofilm microenvironment can polarize macrophages to an anti-inflammatory state [39,41,86,53], inadvertently promoting signals that lead to persistent infection. Compounding this problem, macrophage invasion into S. aureus biofilm in vivo [41] is limited. This was later explained by the production of biofilm-derived factors that inhibited macrophage phagocytosis and promoted cell death, namely leukocidin AB (LukAB) and alpha-toxin (Hla) [142] and confirmed in vivo, where macrophage abundance was increased following infection with a S. aureus lukAB/hla mutant concomitant with reduced bacterial titers in a mouse PJI model [142]. Therefore, the apparent sensitivity of macrophages to toxin-induced cell death may be one reason to explain the paucity of macrophages at the site of PJI. This is compounded by the fact that the macrophages that do survive are skewed towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype by G-MDSC-derived IL-10 and likely other factors in the infectious milieu that remain to be defined. In addition, IL-10 exposure promotes macrophage metabolic reprogramming typified by reduced glycolytic flux [88], which reduces substrate availably for anabolic reactions needed for proinflammatory activity [135]. Importantly, evidence of monocyte/macrophage anti-inflammatory reprogramming has been detected in human subjects with both craniotomy and PJI [9,70].

This begs the question: if monocyte/macrophage metabolic dysregulation is a key determinant for promoting biofilm infection, can this be targeted to skew cells towards a proinflammatory state? Yamada et al. [38] confirmed that monocyte/macrophage oxidative respiration was increased during biofilm formation concomitant with decreased glycolytic flux, indicative of an anti-inflammatory metabolic phenotype. Indeed, attenuating oxidative respiration with the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin enhanced macrophage proinflammatory and antibacterial activity in vitro. Further, targeting oligomycin to monocytes/macrophages in vivo using tuftsin-coated nanoparticles resulted in a heightened proinflammatory profile at the site of infection, as revealed by elevations in Hif1a, Nos2, Tnf, Trem1, Il1b, and Il1a and decreased anti-inflammatory gene expression (Arg1, Il10, and Trem2). Reactive oxygen species production was also enhanced [38] following oligomycin nanoparticle treatment, a trend linked to phagocytosis and bacterial clearance in biofilm infection [138]. This reprogramming dramatically reduced bacterial burden during PJI and, when paired with antibiotic treatment, was able to clear infection in most mice examined [38]. This was particularly notable since oligomycin treatment was not administered until a mature biofilm had formed (i.e., day 7 post-infection) and only a single dose was given. Interestingly, monocyte/macrophage metabolic reprogramming also altered the metabolic profile of non-targeted cells, in particular G-MDSCs, revealing direct cellular crosstalk. This highlights the promise of monocyte/macrophage metabolic reprogramming for mitigating biofilm infection in combination with antibiotics, and this dual pronged approach would make it less likely for bacteria to acquire resistance mechanisms to evade killing.

3.3.3. Biofilm metabolism influences immune responses

In addition to immunometabolic programming, consideration must be given to how pathogen metabolism conditions the infection milieu and immune crosstalk (Fig. 2). Much work has been done exploring the metabolic requirements for bacterial survival, which has been extensively reviewed elsewhere [[143], [144], [145], [146]], including during biofilm formation [147,148]. This section will focus on immune-pathogen metabolic interactions. The repertoire of essential genes for S. aureus intracellular survival in macrophages differs between anti-inflammatory polarized vs. resting macrophages [88]. Recent evidence also demonstrates that bacterial metabolism can shape immune responses, as S. aureus mutants unable to produce formate elicited less G-MDSC and elevated PMN recruitment, which decreased bacterial burden in a mouse PJI model [149]. This relationship was also shown using an S. aureus ATP synthase mutant, where bacterial titers and G-MDSC abundance were decreased and led to a heightened proinflammatory milieu during PJI [150], although a specific mechanism was not delineated in this work. In perhaps the most mechanistic description of immune-biofilm metabolic communication to date, Heim et al. [56] demonstrated that bacterial D- and l-lactate epigenetically reprogram G-MDSCs and macrophages during S. aureus PJI, enhancing IL-10 production. Specifically, biofilm-derived lactate was imported via the MCT1 transporter, where it inhibited HDAC11, a negative regulator of HDAC6. Once disinhibited, HDAC6 augmented IL-10 transcription, resulting in a heightened anti-inflammatory state, increased G-MDSC abundance, and worsened bacterial burden. This was driven by lactate produced by the biofilm and not intrinsic to leukocyte metabolism. Furthermore, l-lactate levels were significantly elevated in the synovial fluid of patients with PJI and augmented IL-10 production by human macrophages, suggesting that lactate may be a key pathway of biofilm-mediated immune programming given its conservation between the mouse model and humans.

On the other side of the coin, host metabolism can be co-opted by S. aureus to promote biofilm formation and survival. One example is itaconate, a TCA cycle intermediate generated by Acod-1 using citrate when the cycle is interrupted during aerobic glycolysis. Tomlinson et al. [151] reported that macrophage-derived itaconate promoted S. aureus biofilm formation in a mouse pneumonia model. The impact of itaconate production was two-fold; first, it inhibited succinate dehydrogenase and glycolytic enzymes in macrophages, resulting in an anti-inflammatory bias. Second, itaconate inhibited S. aureus aldolase, where resultant carbohydrate accumulation shunted bacterial metabolism towards pyrimidine and extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) production, facilitating biofilm formation [151]. These findings were also observed in human subjects with cystic fibrosis, where longitudinal recovery of isolates from individuals with chronic infections acquired greater biofilm forming attributes in the face of continued itaconate elevations in the airway [151]. This demonstration of host-pathogen metabolic interaction demonstrates the complexity of the biofilm problem, and it remains to be seen if similar trends occur in other models of biofilm infection. We have recently detected increased Acod-1 expression and itaconate levels during mouse and human craniotomy and PJI infection [9,70]; however, the functional impact of itaconate in these settings remains unknown.

3.4. Adaptive immunity during biofilm infection

3.4.1. T cells

Compared to the innate immune system, less information is available regarding the role of adaptive immunity during biofilm infection, where most work has focused on CD4+ T cells that coordinate immune responses via cytokine production and cellular communication. One of the first explorations of CD4+ T cells during S. aureus biofilm infection leveraged C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice that are skewed towards Th1 and Th2 responses, respectively [62]. Th2 responses are traditionally known to promote humoral immunity and target parasitic infections, whereas Th1 cells augment immunity to intracellular and extracellular pathogens [36]. Using a PJI model with pre-coated implants, BALB/c mice were often found to spontaneously clear infection along with higher expression of the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 and lower PMN abundance at the site of infection, in contrast to C57BL/6 animals. This phenomenon was STAT6- and regulatory T cell-dependent (Treg-dependent), implicating Th2 and Treg cells in this phenotype. In contrast, Th1 and Th17 cells were deemed detrimental, as IL-12 and IL-6 neutralization increased infection incidence [62]. Th17 cells, are largely implicated in coordinating immunity to extracellular bacteria and fungi at mucosal surfaces. However, Th subsets have diverse roles and much is still being uncovered about their roles in different inflammatory conditions [36]. While this evidence suggested that Th1 and Th17 responses may be poorly equipped to clear biofilm infection, or potentially counterproductive, alternative explanations also exist. First, besides Th cell biases, C57BL/6 and BALB/c strains also possess alternative major histocompatibility complex (MHC) alleles [152], and MHC-II haplotypes have recently been shown to be critical in dictating vaccine and memory responses to S. aureus in non-biofilm models [153]. Furthermore, differences in Toll-like receptor (TLR) receptor expression and activity [154] and innate immune responses [155] have been described in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice, which are crucial for biofilm immunity. Second, other studies have reported few T cell infiltrates at the site of PJI [70,85]; therefore, the cytokine depletion strategies and C57BL/6 and BALB/c strains used in this earlier study [62] may have affected other immune responses. Further supporting this, other work in a mouse PJI model showed that IL-12-deficient mice have lower biofilm burdens [42] and myeloid-specific loss of Arg1, a key enzyme utilized by G-MDSCs to inhibit T cell activation, had no effect on biofilm growth [156]. Although speculative, it is possible that divergent Th cell contributions to PJI could be explained by the initial bacterial inoculum used (i.e., pre-coated implants [62] vs. infection at the time of surgery [70,85]), since higher doses have been shown to elicit divergent immune responses [157]. Additionally, quorum sensing molecules have been shown to promote Treg accumulation during catheter biofilm infection, presumably a negative event [158]; although this work was performed with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, so its applicability to S. aureus biofilm is unclear. Subsequent work using RAG KO mice, adoptive transfer techniques with select Th cell populations, and depletion strategies are needed to further interrogate the importance of T cells and their functional role during PJI.

In contrast to S. aureus PJI, Th1 and Th17 responses were beneficial during S. aureus craniotomy infection [44], and both subsets were detected in human infection [110]. Additionally, T cells exhibited broad transcriptional profiles of senescence and exhaustion in human craniotomy infection [110]. To further explore this finding, craniotomy infection was established in mice engrafted with human adaptive immune cells and compared to those lacking any adaptive immune system (NSG). Strikingly, despite being reconstituted with adaptive immune cells, humanized mice exhibited increased bacterial burden relative to non-engrafted animals [110], potentially implicating superantigens [[159], [160], [161]] or other virulence factors with selectivity for human leukocytes as detrimental factors, a finding not captured by traditional mouse models. Worth noting, this work also identified increased expression of genes encoding HIF1a and glycolytic enzymes in human T cells, similar to what was observed in monocytes and granulocytes [110], which bolsters these factors as potentially broad regulators of the immune response to biofilm infection.

In summary, the importance of Th1, Th17, Th2, and Treg cells during biofilm infection has yet to be fully delineated and likely differs across infectious modalities. Therefore, further work exploring the importance of adaptive immunity during PJI and other biofilm models is warranted.

3.4.2. Vaccines

A discussion of adaptive immunity during biofilm infection requires a brief summary of efforts to develop a S. aureus vaccine. This has long been a goal of the Staphylococcal research community, with dozens of vaccine candidates reaching clinical trials [[26], [27], [28], [29]] but failing to advance due to lack of efficacy, which has been summarized in recent reviews [[162], [163], [164]]. Progress has been made in defining immune roadblocks to S. aureus vaccination, particularly with respect to the role of IL-10 [[165], [166], [167]], S. aureus Hla [165,166], immune tolerance [168], antibody efficacy [169], and novel antibody constructs [170,171]. However, another factor to consider is the myriad of tissue niches that S. aureus can infect, each with unique attributes that can influence the immune response. This has been shown for S. aureus SSTI where distinct roles for various immune factors have been identified in the epidermis vs. dermis [172,173] and more recently biofilm [70], where the same S. aureus strain elicits unique transcriptional and metabolic profiles in granulocytes at different sites of infection (i.e., craniotomy vs. PJI) despite similar bacterial burdens. Therefore, achieving a vaccine platform that provides protection against the wide array of infections caused by S. aureus, including biofilm formation, will undoubtedly continue to be a challenge for the field. In the future, a multipronged approach combining vaccination strategies, immunomodulation, and antibiotics may be effective in combatting biofilm infection although this will be difficult when trying to establish the efficacy of three independent variables.

3.5. Technological advances in diagnostics and treatment of biofilm infection

3.5.1. Proteomics as a potential diagnostic tool

While most of this review has focused on the immune response to biofilm and how this may be leveraged for therapeutic development, another issue exists surrounding accurate and timely diagnosis of biofilm infection. This has been most extensively explored in the context of pediatric CSF shunt infection. CSF shunt infection can be challenging to diagnose due to the difficulty of obtaining positive cultures from slow growing or metabolically dormant organisms typical of biofilm. CSF shunt infection in the pediatric population has been linked with an approximate two-fold increase in patient mortality and enhanced morbidity in the form of seizures and IQ loss [[174], [175], [176]]. Models of CSF shunt infection have been developed that recapitulate biofilm morphology, induce leukocyte recruitment [87,52], and permit serial CSF collection [47], enabling efforts to identify more sensitive diagnostic markers. Initial approaches explored the utility of chemokine and cytokine levels as a proxy for infection, many of which were increased relative to sterile CSF shunt placement [52,53], including CXCL1, CXCL2, IL-17, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10. However, many of these elevations in inflammatory mediators were transient [52,53], and later work analyzing patient CSF samples found similar cytokine and chemokine levels during Gram-negative and Gram-positive infection [54], making these less discriminatory diagnostic targets. Subsequently, mass spectrometry analysis of CSF obtained from a rat model of S. epidermidis CSF shunt infection identified distinct proteomes at multiple time points post-infection. Strikingly, numerous factors in the complement cascade were elevated in CSF as early as 1 day post-infection [47], suggesting these targets may have diagnostic value. This trend was present but less apparent in the context of C. acnes infection [45], hinting that proteomic responses may be somewhat pathogen-specific. Indeed, comparative proteomics on CSF samples from S. epidermidis, C. acnes, and P. aeruginosa shunt infection identified 40–204 proteins unique to each pathogen, depending on the post-infectious interval assessed [46]. Interestingly, 11 proteins were shared across pathogens and elevated above CSF from non-infected catheters, including many complement proteins, S100-A8, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and CD14 [46]. Given the prevalence of complement-related proteins across diverse CSF shunt infections, this pathway was assessed for a role in brain pathology; however, infection severity was unaffected in C3 or C5 KO mice, suggesting these proteins could serve as biomarkers, but may not represent tractable therapeutic targets. These results suggest that proteomics may be a promising diagnostic tool to discriminate sterile from infected conditions as well as potentially between different pathogens.

Infectious diagnoses can also be difficult or delayed in other forms of biofilm infection. For example, some patients with craniotomy infection have been documented to not receive a diagnosis until up to 6 months following infection [110], during which time inflammation and associated tissue damage are likely compounding factors. Additional work on the use of proteomics to identify alternative biomarkers for PJI diagnosis has been conducted with some success [177,178] and expanded efforts have been reviewed elsewhere [179,180]. Regarding the metabolic implications discussed earlier in this review, some work suggests that lactate may have utility as a diagnostic metabolic biomarker for PJI [56,181,182]. However, similar investigation has not been conducted on many other biofilm modalities. Therefore, identifying additional biomarkers to aid in the broader diagnosis of biofilm infections is warranted and has the potential to have a large positive impact on the clinical care of these patient populations.

3.5.2. Bioengineering approaches to prevent and treat biofilm infections

Since many surgical site infections progressing to biofilm formation are thought to originate from contamination by skin flora at the time of surgery, this provides a unique opportunity to incorporate modifications to medical implants to prevent infection. Furthermore, opportunities exist to apply this strategy to treat device-associated infections. In the context of PJI, while a two-staged revision is often performed to remove infected hardware and place an antibiotic-impregnated spacer in the joint space to clear residual infection before a new device is inserted [183], the use of prophylactic antimicrobial coated hardware has yet to become widespread. Recent research at the intersection of biotechnology and immunology has produced exciting possibilities that could be leveraged to deliver immunomodulatory compounds and antimicrobials directly to the site of infection, avoiding concerns of systemic toxicity. One example is a bioresorbable minocycline/rifampin-impregnated polymer coating for implants that exhibited strong antibacterial activity up to 10 days post-infection in a mouse PJI model [184]. In a subsequent study [185], compound properties were altered to facilitate the titrated release of different compounds in the same coating, enabling a modular platform that can be tailored for pathogens based on antibiotic susceptibility profiles. This approach prevented biofilm formation on the implant surface and dramatically reduced infectious burden in surrounding tissue without compromising implant stability, integrity, or biocompatibility [185]. This work highlights an important point- a preferred strategy is to prevent biofilm formation in the first place to maximize the activity of antibiotics and the immune system that are better equipped for clearing planktonic infections. However, the long-term efficacy of this approach remains unclear, as depletion of the antibiotic coating eventually occurs, and biofilm formation could be initiated at later intervals if residual bacteria remain in the tissue. The same approach could theoretically be used for delivering immunomodulatory compounds with antibiotics, which would be expected to have greater efficacy than either modality alone. This strategy has been used in craniotomy infection [60], where antibiotic scaffolds composed of alternating layers of rifampin- and daptomycin-impregnated gels were used to replace infected bone flaps to clear residual infection. Implantation of antibiotic scaffolds at day 7 after craniotomy infection significantly reduced biofilm burden and was potentiated by bioprinting viable macrophages in the scaffold [60], providing proof-of-concept for immune-mediated treatment strategies. While this approach limited S. aureus growth up to 28 days post-infection, bacterial outgrowth eventually occurred due to antibiotic depletion from the scaffold, underscoring the difficulty of biofilm eradication. Although designed to treat infection, the 3D bioprinted scaffold may serve a dual purpose. Prolonged absence of the skull flap that often occurs during the management of craniotomy infection can result in ‘syndrome of the trephined [186],’ a condition characterized by seizures, changes in mood, and behavioral disturbances. Treatment for this disorder involves cranioplasty [187,188]; therefore, a bioprinted scaffold could be developed to treat both infection and trephine syndrome simultaneously. Finally, microparticle and nanoparticle formulations for local delivery of metabolic- or immune-modulatory compounds have shown efficacy in biofilm infection models for at least 14 days post-administration [9,69,86,125]. One benefit of this approach over implant modification strategies is the potential ease of re-dosing micro-/nanoparticles by injection at the site of infection.

3.6. Conceptual considerations regarding the immune response to biofilm infection

3.6.1. Heterogeneity in immune responses across the human population

While animal models and in vitro studies are indispensable in the effort to understand the immune response to biofilm, eventual therapies must be durable to the natural variation across individuals that can be influenced by genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors. While there have been few investigations of human population-level differences in immune responses during biofilm infection, multiple reports have described phenotypic alterations in immune characteristics from cells obtained from different donors in the context of planktonic infection. For example, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from human subjects pre- and post-arthroplasty exhibited variable antimicrobial activity, with differences in bacterial killing spanning multiple orders of magnitude [75]. A later study identified substantial donor variability in the metabolomes of human monocyte-derived macrophages (HMDMs) in response to S. aureus, particularly in nucleotide and amino acid species [88], both of which have been shown to have profound effects on immune function [70,189,190] and bacterial virulence and growth [[191], [192], [193]]. Finally, substantial variability in several immune responses in human subjects with craniotomy biofilm infection has also been reported [110], some of which may be explained by genetic diversity at the host and pathogen levels. Therefore, not surprisingly, human immune responses to biofilm infection exhibit variability across the population, a factor that will need to be considered when developing treatment strategies to combat biofilm growth.

3.6.2. Site-specific heterogeneity in immune responses during biofilm infection

Not only is it important to consider how immune responses are influenced at the human population-level, different tissue niches can also impact immune characteristics [11,16,50,194,195], which has been described in S. aureus skin and soft tissue infection [172,173] and recently across biofilm infections [70]. Specifically, granulocytes recovered from S. aureus craniotomy or PJI exhibited spatial and temporal differences in cytokine production, despite similarities in bacterial burden and leukocyte infiltrates between the sites. This was associated with distinct transcriptional and metabolic profiles that were tissue-specific and time-dependent. Furthermore, transcriptional diversity was also observed in granulocytes isolated from patients with craniotomy and PJI. These findings support recent discussions [196] regarding the importance of understanding how the tissue microenvironment shapes immune responses to infection. Diversity in immune responses identified across biofilm infection models, either by direct comparison [70] or by divergent findings in different systems [39,86,53,109,111,115], supports that anti-biofilm immunity is shaped by microenvironmental cues.

3.6.3. Open questions on how tissue damage influences biofilm infections

Another question in the field of biofilm immunology is when pathogens breach tissues following injury/surgery, how do they evade immune-mediated clearance to establish biofilm infection? Most S. aureus biofilm models discussed in this review are established with low infectious inoculums (∼103 CFU), which almost universally establish chronic infection [85,52,111,58]. This is in contrast to rodent models that lack surgical damage such as abscesses [197], sepsis [198], or pneumonia [199], which instead require 106–107 CFU to initiate infection that either resolves or is lethal, depending on the model, and does not typically result in chronic disease. Furthermore, the same inoculum used to initiate catheter-associated biofilm infection was unable to establish abscess formation at the same site [41]. As mentioned earlier, IL-12 deficiency results in less severe PJI [42]; however, this phenotype was masked when the infectious inoculum was increased from 103 to 105 CFU [157]. Therefore, the number of bacteria introduced at a tissue site can influence immune responses and subsequent pathology in complex and poorly understood ways. This is an important point to consider when leveraging animal models for translation to humans.

Beyond pathogen abundance, tissue damage itself may promote biofilm formation. A potential mechanism for this is poorly understood, but a report identified evidence of elevated anti-inflammatory mediators in the circulation of 26 patients post-arthroplasty when compared to matched pre-surgical samples [75], suggesting that surgery itself may be an important and overlooked ‘virulence factor’.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Current limitations and future directions

The expanding field of immunology and biofilm crosstalk has produced multiple animal models with similarities to human disease. This has provided important insights into the insufficient, and sometimes counterproductive, immune responses elicited by biofilm. Advances have also been made to characterize the complexity of immune responses to biofilm, which are influenced by genetic diversity, tissue niche, metabolism, and likely other determinants that remain to be defined. As the field takes steps towards developing immunomodulatory therapeutics, several knowledge gaps should be addressed.

First, it is becoming increasingly clear that age, metabolic status, infection site, and genetic diversity likely all influence susceptibility to and severity of biofilm infection. Each of these factors deserves exploration with attention paid to nuanced differences across animal models and human subjects. Second, where treatment is concerned, candidate therapeutics must be robust enough to transcend immune diversity in the human population. Therefore, experimental approaches that elicit heightened anti-biofilm responses across genetically diverse model organisms [200], confirming efficacy with multiple bacterial strains and clinical isolates, examining how responses are shaped by infectious inoculums, and expanded use of human samples will be indispensable for accurate modeling of human biofilm infection. These approaches will also help address potential adverse effects from bystander tissue damage or development of autoimmunity that have been associated with immunomodulatory therapies in non-infectious pathologies [201]. Third, bacterial burdens have been a staple in the field for indicating enhanced pathology in animal models. However, it is uncertain whether marginal increases in bacterial abundance translate to clinically worsened infection or poorer outcomes for patients. In the same vein, the identification of factors that trigger bacteria to initiate biofilm formation in vivo is critical, as the easiest biofilm to clear is the one that never forms. Shared attention to aspects of the immune response that alter bacterial abundance as well as those that affect infection incidence are important factors to consider in future work. Finally, given the rising number of surgical procedures [[202], [203], [204]], the incidence of SSIs will also continue to increase; therefore, identifying potential host genetic determinants linked with biofilm infection should be addressed. This would require large-scale multi-center genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to achieve sufficient sample sizes for statistical power and could prove invaluable to clinicians in predicting individuals at heightened risk of infection and advising surgical measures to patients.

4.2. Final perspective

The available evidence to date suggests that non-productive immune responses during biofilm infection are influenced by multiple factors, which by extension will likely require complex solutions. This includes targets that are important across distinct infection sites, post-surgical intervals, and genetic diversity at both the host and pathogen levels, which represents a proverbial ‘needle in the haystack’ challenge. Alternatively, combined treatment with immune modulatory agents and antibiotics may achieve biofilm clearance without the need for additional surgery. The potential of this effort invites the need for additional research on defining critical regulatory mechanisms to modulate productive immune responses to biofilm. The majority of work addressing immune responses to biofilm has been conducted by a handful of groups over the past 15 years. During this time, the field has identified multiple aspects of immune malfunction as key determinants for biofilm formation and chronicity. The next step lies in reversing these trends. Given the substantial progress during the past few years defining the problem, there is much optimism for foundational discoveries and meaningful treatment options in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zachary Van Roy: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Tammy Kielian: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a NIH T32 and UNMC Fellowship (to ZVR) and 3P01 AI083211 Project 4 and R01 AI169788 (to TK).

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue entitled: Approaching Zero published in Biofilm.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Mengistu D.A., et al. Global incidence of surgical site infection among patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inquiry. 2023;60 doi: 10.1177/00469580231162549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee P.H.U., Gawande A.A. The number of surgical procedures in an american lifetime in 3 states. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:S75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.06.186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naghavi M., et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet. 2024;404:1199–1226. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01867-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forgacs P., Geyer C.A., Freidberg S.R. Characterization of chemical meningitis after neurological surgery. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:179–185. doi: 10.1086/318471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman B.A., Tunkel A.R., Pryor J.C., Dacey R.G., Jr. Meningitis in the neurosurgical patient. Infect Dis Clin. 1990;4:677–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross D., Rosegay H., Pons V. Differentiation of aseptic and bacterial meningitis in postoperative neurosurgical patients. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:669–674. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.69.5.0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivasan L., Kilpatrick L., Shah S.S., Abbasi S., Harris M.C. Cerebrospinal fluid cytokines in the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis in infants. Pediatr Res. 2016;80:566–572. doi: 10.1038/pr.2016.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schifman R.B., Pindur A. The effect of skin disinfection materials on reducing blood culture contamination. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993;99:536–538. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/99.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Roy, Z. et al. Single-cell profiling reveals a conserved role for hypoxia-inducible factor signaling during human craniotomy infection. Cell Reports Medicine https://doi.org:10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Livermore D.M. The need for new antibiotics. Clin Microbiol Infection. 2004;10:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-0691.2004.1004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Morais S.D., Kak G., Menousek J.P., Kielian T. Immunopathogenesis of craniotomy infection and niche-specific immune responses to biofilm. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.625467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schilcher K., Horswill A.R. Staphylococcal biofilm development: structure, regulation, and treatment strategies. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2020;84 doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00026-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sauer K., et al. The biofilm life cycle: expanding the conceptual model of biofilm formation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20:608–620. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00767-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandy-Hodgetts K., et al. Uncovering the high prevalence of bacterial burden in surgical site wounds with point-of-care fluorescence imaging. Int Wound J. 2022;19:1438–1448. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heim C.E., et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to staphylococcus aureus orthopedic biofilm infection. J Immunol. 2014;192:3778–3792. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheatle J., Aldrich A., Thorell W.E., Boska M.D., Kielian T. Compartmentalization of immune responses during staphylococcus aureus cranial bone flap infection. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold C., Kournoutas I., Seaman S.C., Greenlee J. Bone flap management strategies for postcraniotomy surgical site infection. Surg Neurol Int. 2021;12:341. doi: 10.25259/SNI_276_2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadhwani N., et al. Comparison of infection rates following immediate and delayed cranioplasty for postcraniotomy surgical site infections: results of a meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2023;173:167–175.e162. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kandel C.E., et al. Predictors of treatment failure for hip and knee prosthetic joint infections in the setting of 1- and 2-stage exchange arthroplasty: a multicenter retrospective cohort. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ricciardi B.F., et al. Staphylococcus aureus evasion of host immunity in the setting of prosthetic joint infection: biofilm and beyond. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018;11:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s12178-018-9501-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis K. Persister cells and the riddle of biofilm survival. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2005;70:267–274. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenney D., et al. The ica locus of staphylococcus epidermidis encodes production of the capsular polysaccharide/adhesin. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4711–4720. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4711-4720.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKenney D., et al. Broadly protective vaccine for staphylococcus aureus based on an in vivo-expressed antigen. Science. 1999;284:1523–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pérez M.M., et al. Protection from staphylococcus aureus mastitis associated with poly-n-acetyl β-1, 6 glucosamine specific antibody production using biofilm-embedded bacteria. Vaccine. 2009;27:2379–2386. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gening M.L., et al. Synthetic β-(1→ 6)-linked n-acetylated and nonacetylated oligoglucosamines used to produce conjugate vaccines for bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun. 2010;78:764–772. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01093-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai C.-M., Caldera J., Hajam I.A., Liu G.Y. Toward an effective staphylococcus vaccine: why have candidates failed and what is the next step? Expet Rev Vaccine. 2023;22:207–209. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2023.2179486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redi D., Spertilli Raffaelli C., Rossetti B., De Luca A., Montagnani F. Staphylococcus aureus vaccine preclinical and clinical development: current state of the art. New Microbiol. 2018;41:208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller L.S., Fowler Jr V.G., Shukla S.K., Rose W.E., Proctor R.A. Development of a vaccine against staphylococcus aureus invasive infections: evidence based on human immunity, genetics and bacterial evasion mechanisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2020;44:123–153. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuz030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armentrout E.I., Liu G.Y., Martins G.A. T cell immunity and the quest for protective vaccines against staphylococcus aureus infection. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1936. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8121936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saadatian-Elahi M., Teyssou R., Vanhems P. Staphylococcus aureus, the major pathogen in orthopaedic and cardiac surgical site infections: a literature review. Int J Surg. 2008;6:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mangram A.J., et al. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:247–280. doi: 10.1086/501620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva M.T., Correia-Neves M. Neutrophils and macrophages: the main partners of phagocyte cell systems. Front Immunol. 2012;3:174. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benoit M., Desnues B.t., Mege J.-L. Macrophage polarization in bacterial infections. J Immunol. 2008;181:3733–3739. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shepherd F.R., McLaren J.E. T cell immunity to bacterial pathogens: mechanisms of immune control and bacterial evasion. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21176144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou L., Chong M.M., Littman D.R. Plasticity of cd4+ t cell lineage differentiation. Immunity. 2009;30:646–655. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu J., Paul W.E. Heterogeneity and plasticity of t helper cells. Cell Res. 2010;20:4–12. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertrand B.P., et al. Metabolic diversity of human macrophages: potential influence on staphylococcus aureus intracellular survival. Infect Immun. 2024;92 doi: 10.1128/iai.00474-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamada K.J., et al. Monocyte metabolic reprogramming promotes pro-inflammatory activity and staphylococcus aureus biofilm clearance. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heim C.E., Vidlak D., Kielian T. Interleukin-10 production by myeloid-derived suppressor cells contributes to bacterial persistence during staphylococcus aureus orthopedic biofilm infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:1003–1013. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4VMA0315-125RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanke M.L., Heim C.E., Angle A., Sanderson S.D., Kielian T. Targeting macrophage activation for the prevention and treatment of staphylococcus aureus biofilm infections. J Immunol. 2013;190:2159–2168. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thurlow L.R., et al. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms prevent macrophage phagocytosis and attenuate inflammation in vivo. J Immunol. 2011;186:6585–6596. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heim C.E., et al. Il-12 promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell recruitment and bacterial persistence during staphylococcus aureus orthopedic implant infection. J Immunol. 2015;194:3861–3872. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heim C.E., West S.C., Ali H., Kielian T. Heterogeneity of ly6g(+) ly6c(+) myeloid-derived suppressor cell infiltrates during staphylococcus aureus biofilm infection. Infect Immun. 2018;86 doi: 10.1128/IAI.00684-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kak G., Van Roy Z., Fallet R., Korshoj L.E., Kielian T. Cd4+ t cell–innate immune crosstalk is critical during staphylococcus aureus craniotomy infection. JCI Insight. 2025;10 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.183327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]