Abstract

Background

The link between tooth loss and cognitive impairment has become increasingly significant. Recent findings suggest that mitochondrial alteration in hippocampal neurons may mediate this relationship.

Objective

This study aimed to explore the mediating role of mitochondria in the relationship between tooth loss and cognitive function in Wistar rats.

Method

Male Wistar rats (n = 20, 12 weeks old) were randomly divided into tooth extraction (TE) and sham groups. The model was established through upper molar extraction and sham operation respectively. Cognitive evaluations were performed using Morris water maze (MWM) test 8 weeks after the model establishment. Hippocampal neuron morphology was observed. Mitochondrial function was evaluated by ATP level and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). Mitophagy assessment involved conducting immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent staining of PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), Parkin (E3 ubiquitin ligase), translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOMM20), and microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3). Additionally, mitophagy protein alterations were analyzed using western blotting.

Results

Memory impairment in the TE group was obvious 8 weeks after model establishment. Substantial hippocampal mitochondrial dysfunction was observed in the TE group, evidenced by notably decreased ATP production, decreased MMP level, and abnormal mitochondrial morphology in the hippocampus. Diminished mitophagy was detected by immunofluorescent staining, and further confirmed by immunostaining and western blotting, indicating diminished mitophagy marker levels in PINK1 and Parkin, along with decreased LC3II/I ratios and elevated Sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1/P62) levels, highlighting hippocampal mitophagy deficiency following tooth loss.

Conclusions

Tooth loss leads to mitochondrial disturbance and inhibits PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in hippocampal neurons, inducing cognitive impairment.

Clinical Relevance

This study reveals mitochondria may mediate the effect of tooth loss on cognitive function, offering a theoretical basis for the prevention of oral health-associated cognitive decline.

Keywords: Dental Occlusion, Tooth Loss, Cognitive Dysfunction, Mitochondria, Mitophagy, Hippocampus

Graphical abstract

Tooth loss in rat results in notable cognitive deterioration, particularly affecting hippocampal function, which is associated with abnormal mitochondrial morphology changes, significant energy metabolism dysfunction, and concurrent mitophagy and autophagy suppression.

Introduction

As the global population ages, the increasing prevalence of dental deficiencies and tooth loss has also become a considerable health issue, influencing mastication, nutritional status, and overall life quality.1 Tooth loss has also been confirmed to be a risk factor for cognitive impairment in numerous clinical researches.2, 3, 4

The connection between tooth loss and cognitive impairment was demonstrated in many animal studies.5,6 For instance, we previously demonstrated that tooth loss animal models exhibited significant cognitive decline, reduced hippocampal neuron count, and various pathological or molecular alterations such as decreased cerebral blood flow, elevated hippocampal glucocorticoid levels, neuroinflammation, and nitric oxide concentrations.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Apoptotic gene activation and brain-derived neurotrophic factor-related pathway inhibition are also common in tooth loss-related cognitive decline.7,12 In animal models, cognitive function partially recovers following restoration using removable partial dentures or resin crowns.13,14 These findings suggest a complex and significant association between tooth loss and cognitive function.

Recently, mitochondrial dysfunction has become increasingly prominent in cognitive impairment disorders, particularly in Alzheimer’s disease.15,16 Damaged mitochondria contribute to neuronal dysfunction by limiting energy supply and promoting oxidative damage.15 Mitophagy, a specialized cellular autophagy pathway, maintains mitochondrial homeostasis and controls mitochondrial viability. The PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin (E3 ubiquitin ligase) pathway is the most common pathway for mitophagy. When mitochondria are damaged, PINK1 is activated and localized on the outer mitochondrial membrane to recruit and activate Parkin, which promotes outer mitochondrial membrane ubiquitination.17 Defects in PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy are commonly observed in neurodegeneration diseases.18 Inhibition of this pathway leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and exacerbates dementia, while stimulating mitophagy has been shown to reverse cognitive deficits.19

Interestingly, recent studies have suggested that oral health can also influence mitochondrial function. Clinical studies have indicated that tooth loss or severe periodontal disease can influence cognitive function via mitochondrial function modulation or synergistic effects.20,21 In animal experiments, tooth loss has been associated with morphological abnormalities in the mitochondria of hippocampal neurons, including swelling, inner membrane cristae disappearance, and a ring-like appearance.22 These findings underscore mitochondria are sensitive to tooth loss-related stimuli, suggesting a potential pathway for cognitive decline. However, the specific mitochondrial functions and mitophagy alterations due to tooth loss remain unclear.

Wistar rats are widely utilized in neuroscience and behavioral research due to their appropriate responsiveness to external stimuli, favorable synaptic plasticity, and stable performance in memory and learning tasks.23,24 Therefore, we established a tooth extraction model in Wistar rats to investigate mitochondrial function and mitophagy changes, aiming to further elucidate the mechanisms between oral health status and cognitive function.

Materials and methods

Animal and experimental design

Male Wistar rats (n = 20, 12-week-old) (SPF Beijing Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) were used in this study. The rats were housed in an environment with a controlled temperature (23-25°C) and a regular light/dark cycle of 12 h (light period: 9 am to 9 pm; dark period: 9 pm to 9 am) and were provided solid food and water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. The experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics and Welfare Committee of Beijing Stomatology Hospital. (Approval No. KQYY-202203-001)

The rats were randomly assigned to 2 groups: TE and sham, each containing 10 rats. The rats were allowed to acclimatize for 7 days before any experimental procedures. The TE group underwent bilateral maxillary molar extraction. In the sham group, a surgical procedure was performed to remove the alveolar crest between the incisors and molars, creating an alveolar bone defect of similar length and extent to the tooth extraction in the TE group. After surgery, the rats regained consciousness and resumed a normal diet, and their general health and weight were monitored. Anesthesia was administered by continuous inhalation of 2–4% isoflurane (RWD Life Science Co., R510-22-10, China) in oxygen. Eight weeks after model establishment, the rats were euthanized under appropriate general anesthesia with constant inhalation of 2–4% isoflurane in oxygen and administration of sodium pentobarbital (35 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, P3761, USA) via intraperitoneal injection (Figure 1A, B).

Fig. 1.

Tooth loss rat model experimental procedure and body weight. (A) Rat model establishment and experimental procedure timeline (MWM, Morris water maze). (B) Bilateral maxillary molar extraction in model rats. (C) Weight changes from week 0-8 for the sham and tooth extraction (TE) groups following model establishment (all data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation [SD], Mann–Whitney U test, P > .05, n = 10).

Morris water maze (MWM) experiment

Eight weeks after the model establishment, the MWM test was performed by independent researchers according to the protocol of Morris.25 The experimental setup included a black circular pool with a diameter of 1.8 m, an invisible transparent platform beneath the water surface, and 4 distinct markers on the pool wall for directional guidance. The visual and motor abilities of the rats were assessed before the experiment to exclude any visual or motor impairment-related factors. The investigation consisted of 2 stages: training and probe trial. The training phase was performed over 4 consecutive days, with each rat undergoing 2 daily trials. The rats were allowed 60 s to find the hidden platform, and the elapsed time was noted as the escape latency. Those unable to locate the platform were guided to it and assigned an escape latency of 60 s. On the fifth day, the platform was removed for probe trials, in which the motion trajectory, time spent in the target quadrant, and platform crossing time were observed. The behavior of the rats was recorded using a digital camera connected to a computer and analyzed using Anymaze software (Stoelting Co., version 4.8, USA), ensuring adherence to blind testing procedures.

ATP content determination

After the MWM experiment, 4 rats were randomly selected from each group for ATP content analysis. Following euthanasia, the hippocampal region was separated from the brain tissue. The ATP content was then determined using an ATP assay kit (Beyotime, S0026, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The entire hippocampal regions were each homogenized as whole samples in ATP lysis buffer using an electronic homogenizer (Jingxin technology, MY-20, China) in an ice bath, followed by heat treatment and centrifugation. The ATP content was then calculated by chemiluminescence measurements using a microplate reader (SpectraMax iD3, Molecular Devices, USA), and normalized to protein concentration.

MMP level determination

The hippocampal region was isolated from 4 randomly selected rats in each group. Mitochondria were then isolated from the hippocampal tissues and resuspended according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a mitochondria isolation kit (Beyotime, C3606, China). For MMP measurement, the mitochondria were aliquoted and assayed using a JC-1 MMP assay kit (Beyotime, C2003S, China). The intensities of green fluorescence at 530 nm and red fluorescence at 590 nm were measured using a multi-mode microplate reader (SpectraMax iD3, Molecular Devices, USA). The ratio of green to red fluorescence was used to determine the MMP levels.

Transmission electron microscopy

Two rats per group were euthanized after proper anesthesia, and fresh hippocampal tissues were immediately isolated and fixed in precooled 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The tissues were rinsed with 0.1M phosphate buffer and fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, followed by dehydration in ascending alcohol concentrations and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (60 nm) were prepared by ultramicrotome (Leica, UC7, Germany), stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were examined under a transmission electron microscope (HITACHI, HT7800, Japan) to analyze the ultrastructure of hippocampal neurons.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on 3 randomly selected rats from each group by independent pathology laboratory technicians. After proper anesthesia, phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) perfusion, and fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde, brain tissues were acquired and subjected to post-fixation, dehydration, and paraffin embedding. Five micron-thick sections were generated using a microtome (Leica, HistoCore BIOCUT, Germany). Immunofluorescence staining was performed using a tricolor fluorescent reagent kit (ImmunoWay, RS0036, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protocol included pre-heating, deparaffinization, antigen retrieval, peroxide-blocking buffer incubation, and incubation with primary antibodies against translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOMM20) (1:250, Abcam, ab186735, UK), followed by secondary antibody incubation and fluorescent labeling with D-594. After treatment with an antibody stripping solution, the primary antibody was switched to Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) (1:500, Proteintech, 14600-1-AP, China), the fluorescent label was changed to D-488, and the above steps were repeated. Cover-slipping was performed using a sealing buffer with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) from the fluorescent kit, and the sections were observed under an Olympus BX61 fluorescence microscope. For quantitative analysis, 5 fields of view from the Dentate Gyrus (DG), Cornu Ammonis (CA) 3, and CA1 regions of each rat hippocampus were captured at 400 × magnification and analyzed using the ImageJ software (version 1.53k, Wayne Rasband and contributors, National Institutes of Health, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on the brain sections of 3 rats per group by independent pathology laboratory technicians. The brain sections were deparaffinized and prepared for antigen retrieval. The subsequent process included endogenous peroxidase inhibition, blocking, and incubation with primary antibodies against PINK1 (1:2000, Proteintech, 14060-1-AP, China) and parkin (1:600, Proteintech, 23274-1-AP, China). The sections were subsequently incubated with a biotin-conjugated secondary antibody developed using diaminobenzidine and counterstained with hematoxylin. Slides were examined under an Olympus BX61 microscope. For quantitative immunohistochemical analysis, 5 fields from each of the DG, CA3, and CA1 regions of the hippocampus were captured at 400 × magnification per rat and analyzed with ImageJ software.

Western blot analysis

Western Blot analysis was conducted using brain tissue samples obtained from the hippocampus of euthanized rats. Total protein was extracted using radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) solution supplemented with a proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Lablead technology, C0101-1ML, China), and the protein concentration was determined. Protein samples were normalized using a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) running buffer. Proteins were then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, blocked, and incubated with primary antibodies against LC3 (1:2000, Proteintech, 14600-1-AP, China), Sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1/P62) (1:1000, Abcam, ab109012, UK), PINK1 (1:600, Proteintech, 23274-1-AP, China), parkin (1:1000, Proteintech, 14060-1-AP, China), GAPDH (1:10000, Abcam, ab9485, UK), and secondary antibodies. Finally, chemiluminescent signals were detected and quantified using a chemiluminescence imager (Bio-Rad, ChemiDoc MP, USA) and ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (Version 9.4.1, GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). Due to the limited sample size in this study, Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare the 2 groups. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Tooth loss did not affect Wistar rat body weights

After model establishment, no notable differences were detected in vital signs or food and water consumption among the rats. Both TE and sham groups had a slightly decreased body weight at 1 week post-operation. However, body weights recovered to their preoperative values by the second week, and the weights of all groups gradually increased (Figure 1C). No significant differences in body weight were observed between the 2 groups (P > .05).

Tooth loss induced spatial learning and memory impairment in Wistar rats

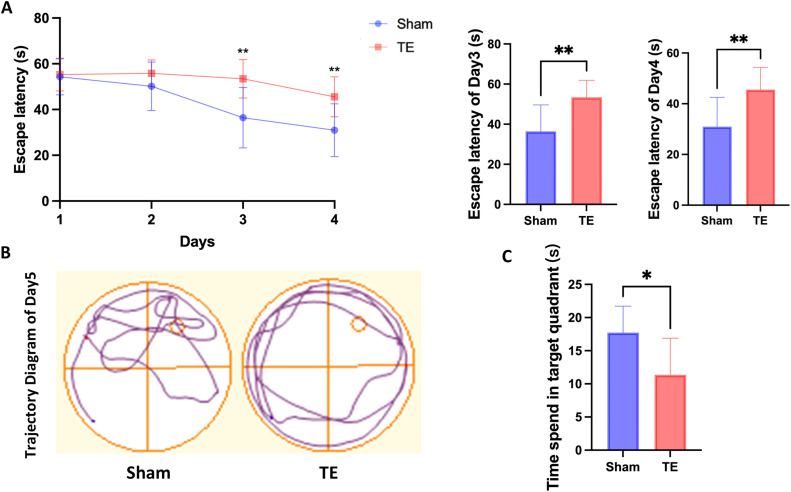

The MWM test was conducted 8 weeks after tooth loss. None of the rats displayed any conspicuous abnormalities in motor or visual function, and their swimming performance did not differ significantly. During the 4-day training phase, both groups of rats demonstrated a decline in escape latency; however, this decline was significantly less pronounced in the TE group (P < .05). By the third and fourth days, the escape latency was significantly longer in the TE group than in the sham group (P < .01; Figure 2A). On the fifth day, the sham group purposefully searched the area around the previous location of the platform, exhibiting a targeted searching behavior, whereas the TE group displayed aimless wall-hugging behavior, indicating different swimming trajectories (Figure 2B). The TE group also spent significantly less time in the target quadrant than the sham group (P < .05; Figure 2C).

Fig. 2.

Comparative cognitive function of the sham and tooth extraction (TE) groups post-model establishment. (A) Escape latency of the sham and TE group in the training phase from day 1-4. On the third and fourth days, the TE group exhibited significantly longer escape latencies (P < .01). (B) Swim trajectories of the sham and TE groups in the probe trail. (C) Dwell time in the quadrant previously containing the platform in the probe trial. The time of the TE group was significantly lower than that of the sham group (P < .05). (All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation [SD], Mann–Whitney U test, *P < .05, **P < .01, n = 10)

Tooth loss led to mitochondrial dysfunction and morphological changes in Wistar rats

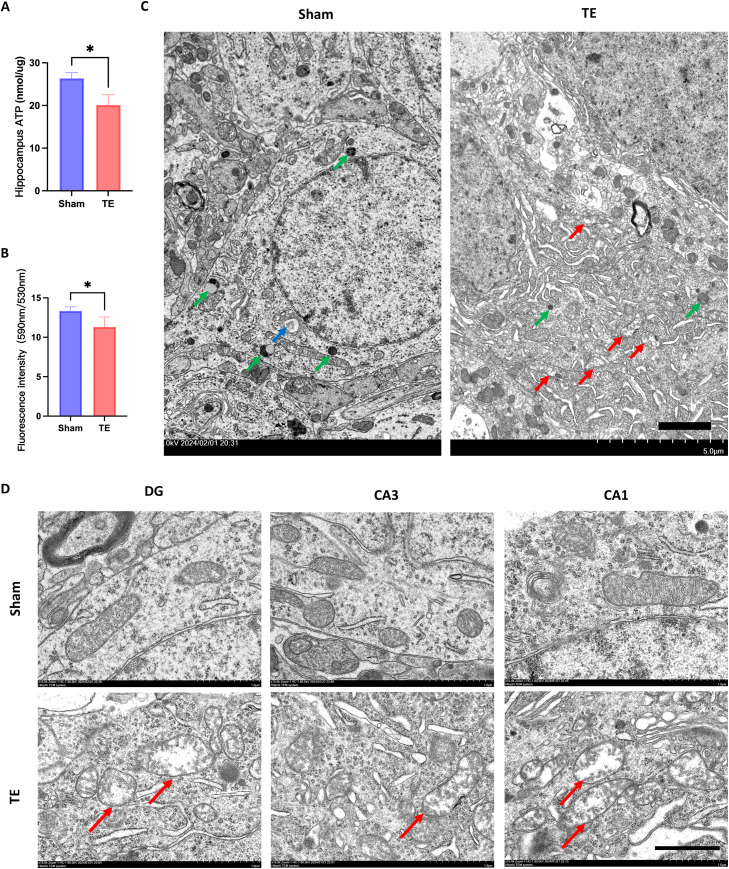

We quantified the ATP and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) levels in the hippocampus of each group. Tooth loss significantly attenuated ATP production in the hippocampus (Figure 3A P < .05): 20.14 ± 2.38 nmol/μg in the hippocampus, as compared to the sham group’s hippocampal ATP levels of 26.36 ± 1.34 nmol/μg. Following JC-1 staining, TE group's hippocampal mitochondria exhibited a significantly reduced ratio of fluorescence intensity at 590 nm to 530 nm, as compared to the sham group (Figure 3B, P < .05), indicating a reduction in MMP level in the hippocampus of the TE group.

Fig. 3.

Mitochondrial function and ultrastructure assessment in the rat hippocampus. (A) ATP concentration in the hippocampus of the sham and tooth extraction (TE) groups. (B) The ratio of fluorescence intensity at 590 nm to 530 nm in hippocampal cell mitochondria, following JC-1 staining, in both sham and TE group (all data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation [SD]; Mann–Whitney U test, **P < .01, n = 4). (C) Transmission electron microscopy images of rat hippocampal neurons, abnormal mitochondria indicated by red arrows, lysosomes indicated by green arrows, and autophagosomes indicated by blue arrows (transmission electron microscopy; 2500 × magnification; scale bar = 2μm). (D) Mitochondrial morphology in subregions of hippocampal neuronal cells, abnormal mitochondria indicated by red arrows (transmission electron microscopy; 15000 × magnification; scale bar = 1μm).

Transmission electron microscopy of hippocampal neurons revealed that in the Sham group, neurons exhibited normal mitochondrial morphology and quantity, normal lysosomal morphology and number, with visible autophagosome formation. In contrast, neurons in the TE group displayed swollen mitochondria and extensive cytoplasmic membrane structures, reduced lysosomal numbers, and fewer autophagosome formations (Figure 3C). Further examination of mitochondrial morphology in hippocampal subregions revealed that in the Sham group, mitochondria maintained a clear double-membrane structure with clear cristae. In contrast, the mitochondrial morphology in the TE group’s neurons showed an obvious swelling structure with cristae degradation, especially pronounced in the DG and CA1 subregions (Figure 3D).

Tooth loss inhibited mitophagy in Wistar rats

Brain sections from each group were subjected to double immunofluorescence staining to assess mitophagy activity. TOMM20, a mitochondrial localization and quantity marker, was visualized with red fluorescence, whereas LC3 was labeled with green fluorescence to indicate autophagic vesicle activity and localization (Figure 4A). Microscopic observations and quantification revealed that the TOMM20 fluorescence intensity remained consistent within the DG and CA1 regions (P > .05), while LC3 fluorescence was less condensed in the TE group than in the sham group (P < .05). Furthermore, the co-localized puncta of LC3 and TOMM20 were significantly decreased in the DG and CA1 regions compared to those in the sham group. In contrast, there was no significant difference in fluorescence intensity in the CA3 region between the groups (P > .05, Figure 4B).

Fig. 4.

Mitophagy activity accessed by brain section immunofluorescent double staining of TOMM20, LC3, and DAPI. (A) Immunofluorescence stain of the hippocampus. Mitochondrial marker TOMM20 (red) and autophagic vesicle marker LC3 (green), merged images show co-localization, reflecting the mitophagy intensity in the DG, CA1, and CA3 regions. The nucleus was marked with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). (B) Quantitative analysis of Tomm20 and LC3 fluorescence intensity in the DG, CA3, and CA1 regions. (immunofluorescence; × 400 magnification; the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation [SD]; Mann–Whitney U test, *P < .05, **P < .01; n = 3, with analyses conducted on 5 fields per region for each of the 3 animals; scale bar = 50 μm)

Tooth loss reduced PINK1 and parkin expression in Wistar rats

To further confirm the alteration in mitophagy in the hippocampus, Mitophagy-related hippocampal protein expression was assayed by western blotting in 4 rats from each group (Figure 5A). Compared to the sham group, PINK1 and parkin expression in the TE group decreased significantly (P < .05). Furthermore, there was a notable decrease in the LC3II/I ratio in the TE group compared to that in the sham group (P < .05), accompanied by an increase in P62 levels (P < .05), suggesting an overall decline in hippocampal autophagy (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5.

Autophagy and mitophagy marker changes in the rat hippocampus after tooth loss. (A) Western blot analysis of hippocampal PINK1, P62, parkin, LC3, and GAPDH. (B) Western blot result quantification of hippocampal PINK1, P62, parkin, LC3, and GAPDH (the data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation [SD], Mann–Whitney U test, *P < .05, **P < .01, n = 4.)

Additionally, Immunohistochemical staining for PINK1 and parkin was performed on brain sections from 3 rats in each group (Figure 6A, 6C) to further investigate their localization and changes in expression levels in the hippocampus. Quantification results revealed that compared to the sham group, there was a significant reduction in the staining intensity of PINK1 and parkin proteins in the DG and CA1 regions of the hippocampus in the TE group (P < .05, Figure 6B, 6D). However, these intergroup differences were not significant in the CA3 region (P > .05; Figure 6B, 6D).

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemical staining and quantitative analysis of PINK1 and parkin in the rat hippocampus. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of PINK1 in the DG, CA3, and CA1 regions of the hippocampus. (B) Quantitative analysis of PINK1 staining intensity in the DG, CA3, and CA1 regions. (C) Immunohistochemical staining of parkin in the DG, CA3, and CA1 regions of the hippocampus. (D) Quantitative analysis of parkin staining intensity in the DG, CA3, and CA1 regions (immunohistochemical staining, × 400 magnification, the mean optical density (MOD) values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation [SD], Mann–Whitney U test, *P < .05, **P < .01; n = 3, with analyses conducted on 5 fields per region for each of the 3 animals; scale bar = 50 μm.)

Discussion

Tooth loss may lead to decreased cognitive function and molecular and pathological changes in the brain.5 Some studies have found that tooth loss may cause abnormal mitochondrial morphology.22 However, it is unclear whether tooth loss leads to mitochondrial function and mitophagy alterations. In this study, we focused on the effects of tooth loss on mitochondria and cognitive function. We determined the minimum number of animals for our study based on our prior publication, a systematic review that focused on animal experiments related to tooth loss and cognitive impairment. This review indicated that the typical sample size in most of the reviewed articles ranged from 6 to 13 per group.5 Additionally, we concluded that the development of our tooth loss animal model is stable and effective, as evidenced by our previous studies.9,12 Therefore, we estimated a sample size of 10 for each group to ensure statistically significant outcomes while minimizing animal deaths.

The Wistar rat lineage is widely used in animal research due to its long-established genetic stability.26 Young Wistar rats display sensitive and moderate response to external stimuli, exhibit robust learning behaviors, and reliably maintain long-term potentiation and long-term depression, making them ideal for neuroscience and behavioral studies.23,24 However, studies have indicated that hormonal fluctuations in female rats may introduce potential confounding factors in behavioral experiments.27, 28, 29 We established a tooth loss model by extracting the bilateral maxillary molars, a widely recognized method for creating tooth loss models.5,30,31 Concurrently, a sham operation was performed on the sham group to produce a trauma comparable to that of the TE group, controlling confounding factors related to surgical trauma and postoperative pain. Changes in cognitive function and hippocampal region were monitored after 8 weeks, a period shown in previous studies sufficient for significant alterations.8,14 After model establishment, we observed that both the TE and sham groups had decreased body weight after 1 week, which returned to preoperative levels 2 weeks after surgery and continued to increase, with no intergroup differences throughout the experiment. This finding suggests that interference related to trauma or malnutrition can be effectively eliminated.32

The MWM test is 1 of the most widely used and reliable behavioral test for assessing spatial learning and memory abilities in animals.25 After 8 weeks of tooth loss, the TE group exhibited significantly longer escape latency, an aimless searching strategy, and spent less time in the target quadrant than the sham group in the MWM test, suggesting a decline in cognitive ability. According to our previous research and other studies, a measurable decline in cognitive function can be observed within 8–12 weeks of tooth loss.7,10,33 Longer monitoring periods further illustrated that the effects on the nervous system and cognitive capabilities are either maintained or intensified,30,34 indicating a strong correlation between tooth loss and cognitive impairment.

The hippocampus is crucial in memory formation and spatial navigation, and can be subdivided into several regions, including the DG, CA1, CA2, and CA3 regions.35 Among these, the DG is primarily involved in encoding novel information, the CA3 region supports pattern completion and associative memory, while the CA1 region is crucial for the retrieval and integration of spatial memory.36 Considering the established connection between cognitive impairment and hippocampal alterations, we performed a detailed hippocampal examination.

The role of mitochondrial disturbance in cognitive disorders has recently been further confirmed, which may be a key mechanism that affects cognitive function.37 Here, both decreased ATP concentrations and MMP were observed in the hippocampus of the TE group, suggesting that tooth loss may contribute to mitochondrial energy metabolism dysfunction in hippocampal cells. Additionally, transmission electron microscopy of hippocampal neurons of the TE group showed that some mitochondria, especially in the DG and CA1 regions, exhibited swelling and loss of cristae, indicating that mitochondria are sensitive to tooth loss stimuli, which is consistent with the previously noted mitochondrial function abnormalities. Our previous findings suggest that tooth loss can reduce cerebral blood flow and elevate brain inflammation levels.7,9,11 Recent researches reveal that reduced cerebral perfusion may impair mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by altering the expression and activity of related proteins and disrupting mitochondrial protein turnover and import processes.29 In addition, under neuroinflammatory conditions, elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines can disrupt mitochondrial dynamic balance and energy metabolism. Damaged mitochondria, in turn, can further amplify neuroinflammation and ultimately contribute to the development of neurodegenerative diseases.38,39 Thus, the observed mitochondrial disturbances can be secondary effects to these changes, resulting in insufficient energy for neurological functions and subsequent cognitive decline.

Double immunofluorescence staining of TOMM20 and LC3 has been used to reveal mitophagy activity.40 We found no significant difference in TOMM20 intensity between the sham and TE groups, but the TE group exhibited a reduced intensity of LC3 fluorescence and combined fluorescence in the DG and CA1 regions. The results indicated that although the quantity of mitochondria was not significantly different, the co-localization of autophagosomes and mitochondria was less prevalent in the TE group in the DG and CA1 regions, suggesting that tooth loss could lead to reduced mitophagy activity in the hippocampus.

The PINK1/Parkin pathway is a classical pathway in mitophagy. When a damage-induced transmembrane potential decrease occurs in the mitochondria, PINK1 activates and localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane. It activates and recruits parkin to the mitochondria, and assists parkin in ubiquitinating the outer mitochondrial membrane. Eventually, the ubiquitinated mitochondria are recognized by membrane surface receptors of autophagic vesicles and degraded via the mitochondrial autophagic pathway.17,41 In neurodegenerative diseases, the PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy pathway is commonly impaired, as evidenced by a discernible decrease in PINK1 and parkin expression.19,42,43 Autophagic activity reduction has also been observed in neurodegenerative diseases, especially Alzheimer’s disease.44 The LC3II/I ratio and P62 levels serve as critical indicators for assessing autophagic flux, with the former reflecting autophagosome formation and the latter being degraded upon autophagosome-lysosome fusion.45

In this study, to further evaluate alterations in mitophagy levels in hippocampal neurons, the expression levels of these related proteins were assessed by western blot analysis. The findings revealed a reduction in PINK1 and parkin protein levels in the hippocampus of the TE group, indicating a decrease in mitophagy activity. Additionally, a diminished LC3II/I ratio and elevated P62 levels were also observed, indicating an overall decrease in autophagy. Insufficient mitophagy and autophagy may lead to the ineffective clearance of damaged mitochondria, disrupting mitochondrial homeostasis and resulting in reduced energy production and intensified electron leakage, which could act as an initiating factor for memory impairment or as a consequence of hippocampal energy metabolism deficiency.46

Through immunohistochemical staining for PINK1 and Parkin, we investigated their localization and changes in expression levels within the subregions of the hippocampus. Significant reduction in the expression of both proteins were observed in the DG and CA1 regions of the TE group, suggesting that mitophagy is more likely to be impaired in these specific subregions, which may correspond with higher susceptibility of the DG and CA1 regions to external stimuli.47 These findings are consistent with the results from immunofluorescence staining and transmission electron microscopy, which also indicated impaired mitophagy in the DG and CA1 regions, potentially leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and morphological alterations. Such changes may contribute to functional deficits in DG and CA1 regions, interfering information encoding and spatial memory retrieval respectively, and subsequently leading to cognitive decline.

This study has several limitations, including using a single-sex animal and restricted observation duration. Despite these limitations, our study provides new insights into the mechanism between tooth loss and impaired cognitive function, offering a theoretical basis for the prevention of oral health-associated cognitive decline. Future studies should involve larger and more diverse samples, including both sexes, and extend the observation period to comprehensively investigate the dynamic impacts of tooth loss on mitochondrial functionality and mitophagy, further discovering the underlying molecular mechanism.

Conclusion

Eight-week tooth loss led to cognitive impairment in Wistar rats. Furthermore, tooth loss was associated with disturbances in mitochondrial function and inhibition of PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in hippocampal neurons, contributing to cognitive decline.

Author contribution

Shixiang Meng: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft; Yunping Lu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review and editing; Jiangqi Hu: Methodology, Writing-review and editing; Bin Luo: Methodology, Writing – review and editing; Xu Sun: Methodology, Writing - review and editing; Xiaoyu Wang: Methodology, Writing - review and editing; Qingsong Jiang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - review and editing. All the authors agree with the version of this manuscript submitted for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82170980, 82301110] and the Beijing Stomatological Hospital, Capital Medical University [grant number YSP202106].

References

- 1.Brennan D.S., Spencer A.J., Roberts-Thomson KF. Tooth loss, chewing ability and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(2):227–235. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saito S., Ohi T., Murakami T., et al. Association between tooth loss and cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older Japanese adults: a 4-year prospective cohort study from the Ohasama study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:8. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0602-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarenga M.O.P., RdO Ferreira, Magno M.B., Fagundes N.C.F., Maia L.C., Lima RR. Masticatory dysfunction by extensive tooth loss as a risk factor for cognitive deficit: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2019;10:832. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maria MTS, Hasegawa Y, Khaing AMM, Salazar S, Ono T. The relationships between mastication and cognitive function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Japanese Dental Science Review. 2023;59:375-88. 10.1016/j.jdsr.2023.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Wang X.Y., Hu J.Q., Jiang QS. Tooth Loss-Associated Mechanisms That Negatively Affect Cognitive Function: a Systematic Review of Animal Experiments Based on Occlusal Support Loss and Cognitive Impairment. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:19. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.811335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebrahimpour S., Esmaeili A., Esmaeili A., Sattari K., Hafshejani KF. Molar tooth shortening induces learning and memory impairment in Wistar rat. Oral Dis. 2023;29(3):1356–1366. doi: 10.1111/odi.14093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo B., Pang Q., Jiang Q. Tooth loss causes spatial cognitive impairment in rats through decreased cerebral blood flow and increased glutamate. Arch Oral Biol. 2019;102:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pang Q., Wu Q., Hu X., Zhang J., Jiang Q. Tooth loss, cognitive impairment and chronic cerebral ischemia. J Dent Sci. 2020;15(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun X., Lu Y., Pang Q., Luo B., Jiang Q. Tooth loss impairs cognitive function in SAMP8 mice via the NLRP3/Caspase-1 pathway. Oral Dis. 2023 doi: 10.1111/odi.14646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang Q., Hu X., Li X., Zhang J., Jiang Q. Behavioral impairments and changes of nitric oxide and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the brains of molarless KM mice. Behav Brain Res. 2015;278:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y.P., Pang Q., Wu Q.Q., Luo B., Tang X.F., Jiang QS. Molar loss further exacerbates 2-VO-induced cognitive impairment associated with the activation of p38MAPK/NF kappa B pathway. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.930016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu J.Q., Wang X.Y., Kong W., Jiang QS. Tooth loss suppresses hippocampal neurogenesis and leads to cognitive dysfunction in juvenile Sprague-Dawley rats. Front Neurosci. 2022;16(8) doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.839622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakamoto S., Hara T., Kurozumi A., et al. Effect of occlusal rehabilitation on spatial memory and hippocampal neurons after long-term loss of molars in rats. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41(10):715–722. doi: 10.1111/joor.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekuni D., Tomofuji T., Irie K., et al. Occlusal disharmony increases amyloid-β in the rat hippocampus. Neuromol Med. 2011;13(3):197–203. doi: 10.1007/s12017-011-8151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W., Zhao F., Ma X., Perry G., Zhu X. Mitochondria dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: recent advances. Mol Neurodegener. 2020;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s13024-020-00376-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang C.H., Yan S., Zhang ZJ. Maintaining the balance of TDP-43, mitochondria, and autophagy: a promising therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative diseases. Transl Neurodegener. 2020;9(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s40035-020-00219-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen T.N., Padman B.S., Lazarou M. Deciphering the Molecular Signals of PINK1/Parkin Mitophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(10):733–744. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pradeepkiran J.A., Reddy PH. Defective mitophagy in Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Research Reviews. 2020;64 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang E.F., Hou Y.J., Palikaras K., Adriaanse B.A., Kerr J.S., Yang B.M., et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-beta and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(3):401. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao W., Wang X., Wang X., Cai Y., Luan Q. Association of cognitive function with tooth loss and mitochondrial variation in adult subjects: a community-based study in Beijing, China. Oral Dis. 2016;22(7):697–702. doi: 10.1111/odi.12529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li A., Du M., Chen Y., Marks L.A., Visser A., Xu S., et al. Periodontitis and cognitive impairment in older adults: The mediating role of mitochondrial dysfunction. J Periodontol. 2022;93(9):1302–1313. doi: 10.1002/JPER.21-0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katano M., Kajimoto K., Iinuma M., Azuma K., Kubo K-y. Tooth loss early in life induces hippocampal morphology remodeling in senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 (SAMP8) mice. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17(4):517–524. doi: 10.7150/ijms.40241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manahan-Vaughan D., Schwegler H. Strain-dependent variations in spatial learning and in hippocampal synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus of freely behaving rats. Front Behav Neurosci. 2011;5 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armario A., Belda X., Gagliano H., et al. Differential hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to stress among rat strains: methodological considerations and relevance for neuropsychiatric research. Current Neuropharmacology. 2023;21(9):1906–1923. doi: 10.2174/1570159x21666221129102852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Meth. 1984;11(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakanishi S., Serikawa T., Kuramoto T. Slc:Wistar outbred rats show close genetic similarity with F344 inbred rats. Experimental Animals. 2015;64(1):25–29. doi: 10.1538/expanim.14-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blokland A., Rutten K., Prickaerts J. Analysis of spatial orientation strategies of male and female Wistar rats in a Morris water escape task. Behav Brain Res. 2006;171(2):216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Souza D., Sadananda M. Estrous Cycle Phase-Dependent Changes in Anxiety- and Depression-Like Profiles in the Late Adolescent Wistar-Kyoto Rat. Annals of neurosciences. 2017;24(3):136–145. doi: 10.1159/000477151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tukacs V., Mittli D., Hunyadi-Gulyás E., et al. Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion-Induced Disturbed Proteostasis of Mitochondria and MAM Is Reflected in the CSF of Rats by Proteomic Analysis. Molecular Neurobiology. 2023;60(6):3158–3174. doi: 10.1007/s12035-023-03215-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawahata M., Ono Y., Ohno A., Kawamoto S., Kimoto K., Onozuka M. Loss of molars early in life develops behavioral lateralization and impairs hippocampus-dependent recognition memory. BMC Neurosci. 2014;15:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murakami A., Hara T., Yamada-Kubota C., Kuwahara M., Ichikawa T., Minagi S. Lack of occlusal support did not impact amyloid β deposition in APP knock-in mice. J Prosthodont Res. 2022;66(1):161–166. doi: 10.2186/jpr.JPR_D_20_00205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Q.S., Liang Z.L., Wu M.J., Feng L., Liu L.L., Zhang JJ. Reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in cortex and hippocampus involved in the learning and memory deficit in molarless SAMP8 mice. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124(10):1540–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taslima F., Abdelhamid M., Zhou C., Chen Y., Jung C-G, Michikawa M. Tooth Loss Induces Memory Impairment and Glial Activation in Young Wild-Type Mice. Journal of Alzheimer's disease reports. 2022;6(1):663–675. doi: 10.3233/adr-220053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubo K.Y., Murabayashi C., Kotachi M., et al. Tooth loss early in life suppresses neurogenesis and synaptophysin expression in the hippocampus and impairs learning in mice. Arch Oral Biol. 2017;74:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sekeres M.J., Winocur G., Moscovitch M. The hippocampus and related neocortical structures in memory transformation. Neurosci Lett. 2018;680:39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hainmueller T., Cazala A., Huang L.W., Bartos M. Subfield-specific interneuron circuits govern the hippocampal response to novelty in male mice. Nature Communications. 2024;15(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-44882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tashiro R., Ozaki D., Bautista-Garrido J., et al. Young Astrocytic Mitochondria Attenuate the Elevated Level of CCL11 in the Aged Mice, Contributing to Cognitive Function Improvement. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6) doi: 10.3390/ijms24065187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peggion C., Calì T., Brini M. Mitochondria Dysfunction and Neuroinflammation in Neurodegeneration: Who Comes First? Antioxidants. 2024;13(2) doi: 10.3390/antiox13020240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin M.M., Liu N., Qin Z.H., Wang Y. Mitochondrial-derived damage-associated molecular patterns amplify neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2022;43(10):2439–2447. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-00879-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duan K., Gu Q., Petralia R.S., et al. Mitophagy in the basolateral amygdala mediates increased anxiety induced by aversive social experience. Neuron. 2021;109(23):3793–3809.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer F., Hamann A., Osiewacz HD. Mitochondrial quality control: an integrated network of pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37(7):284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kerr J.S., Adriaanse B.A., Greig N.H., et al. Mitophagy and alzheimer’s disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40(3):151–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy P.H., Oliver DM. Amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau-induced defective autophagy and mitophagy in Alzheimer's disease. Cells. 2019;8(5) doi: 10.3390/cells8050488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang W., Xu C., Sun J., Shen H-M, Wang J., Yang C. Impairment of the autophagy–lysosomal pathway in Alzheimer's diseases: Pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(3):1019–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogov V., Dötsch V., Johansen T., Kirkin V. Interactions between autophagy receptors and ubiquitin-like proteins form the molecular basis for selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 2014;53(2):167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fischer T.D., Hylin M.J., Zhao J., Moore A.N., Waxham M.N., Dash P.K. Altered Mitochondrial Dynamics and TBI Pathophysiology. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2016;10 doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2016.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]