Abstract

Reducing cardiovascular disease disparities will require a concerted, focused effort to better adopt evidence-based interventions, particularly those that address social determinants of health, in historically marginalized populations (i.e., communities excluded based on social identifiers like race, ethnicity, sexuality and social class and subject to inequitable distribution of social, economic, physical, and psychological resources). Implementation science is centered around stakeholder engagement and by virtue of its reliance on theoretical frameworks, is custom-built for addressing research-to-practice gaps. However, little guidance exists for how best to leverage implementation science to promote cardiovascular health equity. This American Heart Association statement was commissioned to define implementation science with a cardiovascular health equity lens and to evaluate implementation research that targets cardiovascular inequities. We provide a 4-step roadmap and checklist with critical equity considerations for selecting/adapting evidence-based practices, assessing barriers and facilitators to implementation, selecting/using/adapting implementation strategies, and evaluating implementation success. Informed by our roadmap, we examine several organizational, community, policy and multi-setting interventions and implementation strategies developed to reduce health disparities. We highlight gaps in implementation science research to date aimed at achieving cardiovascular health equity, including lack of stakeholder engagement, rigorous mixed methods, and equity-informed theoretical frameworks. We provide several key recommendations, including the need for improved conceptualization and inclusion of social and structural determinants of health in implementation science, and the use of adaptive, hybrid effectiveness designs. In addition, we call for more rigorous examination of multi-level interventions and implementation strategies with the greatest potential for reducing both primary and secondary cardiovascular disparities.

Keywords: implementation science, equity, cardiovascular disease

INTRODUCTION

Historically marginalized populations, defined as groups and communities experiencing discrimination and exclusion (social, political and economic) because of unequal power relationships across economic, political, social, ideologic, or cultural dimensions,1 continue to have disproportionately high rates of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and CVD risk factors.2 Many evidence-based practices (EBPs), defined here and in Table 11-20 as interventions, guidelines, clinical practices, programs, or policies, have been tested and shown to be effective at improving CVD outcomes within historically marginalized populations. However, experts posit that gaps in the implementation of these EBPs may partially explain persistent CVD disparities, defined as differences in metrics/outcomes due to social, economic or environmental disadvantage.10, 11 Implementation science provides a useful lens for understanding and intervening on these “evidence-to-practice” gaps14 and offers a pathway to achieving population level CV health equity, where everyone has the opportunity to achieve their fullest health potential.10, 11, 21–23

Table 1.

Definitions of key implementation science and health equity terms used in this scientific statement

| Terms | Definitions in this Statement |

|---|---|

| Historically Marginalized Populations1 | Groups and communities that experience discrimination and exclusion across economic, political, social, ideologic and cultural dimensions (e.g., black, indigenous and people of color, low socioeconomic status, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, and their allies (LGBTQA), persons living in rural areas, people with disabilities, and women) |

| Evidence based Practice | Interventions, clinical practices, guidelines, programs, or policies with demonstrated effectiveness in trials or based on expert consensus in equitably improving cardiovascular disease outcomes. |

| Cardiovascular Disease2 | Coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease/stroke, peripheral vascular disease, or heart failure |

| Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors2 | Hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, physical inactivity, improper diet, tobacco use |

| Adaptation3–5 | The degree to which an EBP is changed or modified by a user during adoption and implementation to suit the needs of the setting or improve the fit to local conditions |

| Adaptive Design6 | A randomized controlled trial design in which data are collected and used informatively to make important anticipated decisions pertaining to a trial, with alternative choices enumerated in advance |

| Community Based Participatory Research7 | A population health approach to the patient-centered engagement model, the principles of which include trust among partners, respect for each partner’s expertise and contributions, mutual benefit among all partners, and a community-driven partnership with equitable and shared decision-making |

| Cultural Adaptation4,5 | Reviewing and changing the structure of a program or practice to fit the needs and preferences of a particular group, setting or community more appropriately |

| De-implementation8 | Stopping, abandoning or replacing practices that have not proved to be effective and are possibly harmful |

| Dissemination9 | Active approach of spreading EBPs to a target audience via determined channels using planned strategies |

| Fidelity3 | The degree to which an EBP is implemented as it is prescribed in the original protocol in terms of adherence to the program protocol, dose or amount of program delivered, quality of program delivery, and participant reaction and acceptance |

| Health Disparity10,11 | Differences in health or health care and outcomes between different groups based on social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage |

| Health Inequity10,11 | Systematic, unfair or avoidable differences in health status |

| Hybrid Effectiveness-implementation Studies12 | Study designs that blend the design characteristics of effectiveness and implementation studies to generate more timely uptake of desirable EBPs and more relevant information for future scale up activities; Hybrid type 1 includes a primary focus on testing the effectiveness of an EBP while collecting implementation-relevant data as a secondary outcome; Hybrid type 2 involves the parallel testing of intervention and implementation strategy effectiveness; Hybrid type 3 primarily focuses on testing the effectiveness of an implementation strategy while secondarily gathering information on the EBP impact on relevant outcomes |

| Implementation Outcomes13 | Effects of deliberate and purposive actions to implement new treatments, practices, and services, which are distinct from clinical outcomes and include acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, costs, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability |

| Implementation Science14 | Study of methods to promote the equitable and systematic uptake of research findings and other EBPs into healthcare policy and routine practice, and thus, improve the quality and effectiveness of health services |

| Implementation Strategy15 | Methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of an EBP |

| Learning Healthcare Systems16 | System of aligned science, culture, informatics, and incentives to promote continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices embedded in the delivery process and new knowledge captured as a by-product of the experience |

| Multi-level Approaches | Approaches that target some combination of levels that can include the individual, peers, clinicians and healthcare settings, community environments, and policies |

| Practice Facilitation15 | An implementation strategy aimed at assisting practices with developing capacity, via interactive problem solving and support, for sustained implementation of EBPs, often in response to a recognized need for improvement and a supportive interpersonal relationship |

| Social and Structural Determinants of Health11 | Non-medical factors that influence health outcomes (e.g., income, education, employment, food insecurity, housing, early childhood development, structural conflict, access) |

| Socio-Ecological Model17 | Models that recognize multiple levels of influence on health behaviors and outcomes, including societal, policy, community, organization, relational and individual levels of influence |

| Stepped Wedge Design18 | Clusters of clinics or settings are sequentially exposed to an intervention over time |

| Structural Racism10,19 | A system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity |

| Sustainability20 | The extent to which a newly implemented evidence-based intervention is delivered as intended over an extended period of time after external support is terminated in an ongoing and stable manner |

What is Implementation Science?

Implementation science is the scientific study of methods for promoting the systematic uptake of research findings and other EBPs into healthcare policy and routine practice and hence to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services.14 Several experts,22, 24 simplify this definition by distinguishing EBPs and their effects (does the EBP work) from implementation strategies (i.e., the “stuff” or bundle of interventions, methods or techniques needed to help people/settings do the EBP)13, 15 and their effects (how much or how well people/places perform the EBP). Implementation studies are complementary to and often combined with real-world effectiveness studies (in hybrid effectiveness-implementation studies) to address distinct questions.12 For example, effectiveness questions include Does this intervention achieve the expected change(s) in health outcomes? while implementation questions include To what degree is the intervention followed? or What factors influence the sustained use of the intervention?

Leveraging Implementation Science to Achieve CV Health Equity

Leveraging implementation science to achieve CV health equity requires an explicit understanding of how social and structural determinants of health (SDoH)11 contribute to inequities and thus poor CV health. According to the World Health Organization, SDoH are the non-medical factors (e.g., food/housing insecurity, lack of access to high quality treatment/medications, social isolation, poverty, structural racism, discriminatory policies)11 that influence health disparities (or differences in outcomes) and contribute to health inequities—the unfair and avoidable differences in health status.10, 11 In the context of implementation science, two key drivers of CV disparities are: (1) that EBPs are often less effective in historically marginalized populations because of under-representation in clinical trials and lack of trials designed with equity in mind,25, 26 and (2) the failure to adopt effective EBPs in historically marginalized populations, which represents a unique case of implementation failure. EBPs may be underutilized or appear less effective when they fail to mitigate barriers, including SDoH, or to leverage assets unique to historically marginalized populations.26 Implementation science starts with identifying high-quality EBPs with the greatest potential for reducing disparities. Second, it features diverse, multidisciplinary teams to systematically identify barriers to implementation and design implementation strategies that target these barriers and maximize both adoption and effectiveness of EBPs.

Objectives

The objectives of this American Health Association (AHA) statement are to (1) Examine EBPs for reducing CVD disparities using an implementation science equity lens; (2) Highlight studies that examine barriers and facilitators to implementation of such EBPs; (3) Summarize implementation strategies that promote adoption of such EBPs; and (4) Provide examples for evaluating implementation success. Our overarching goals are to provide a roadmap and checklist for leveraging implementation science to achieve CV health equity, and to highlight future directions for policymakers, researchers, and clinicians. Our aim as a multidisciplinary group of clinicians, implementation scientists, CV epidemiologists, and social scientists is to extend and improve the reach of implementation science for advancing CV health equity to clinical audiences.

METHODS

We conducted a scoping review—one designed to assess the size and scope of the available research literature on implementation science and equity and to identify the nature and extent of research evidence using a structured process.27 We searched four databases—PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and SCOPUS—for English-language published research available up to May 2021 (see Supplementary Material for search terms). Because implementation science is a relatively new field, limited by misclassification of keywords and overlap with health services research, we augmented the review by searching for qualitative and quantitative studies related to EBPs, disparities, equity, implementation science, and CVD on Google Scholar. We considered at least one of the following factors when evaluating studies for inclusion in the review: study design with preference for systematic reviews or randomized controlled trials; evaluation of primary or secondary CVD prevention in historically marginalized populations in the U.S.; use of implementation science frameworks; and distinction between EBPs and implementation strategies. Informed by the socio-ecologic model,17 we aimed to provide examples from policy, community (i.e., outside the healthcare system including schools, childcare centers, worksites, social service organizations and religious organizations),28 organizational or multiple settings most relevant to the field of implementation science while highlighting the level or intended audience (multi-, patient, clinician, or system) of a given intervention. We defined historically marginalized populations as individuals or communities excluded based on social identifiers such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and social class as well as inequitable distribution of social, economic, physical, and psychological resources.1 We were very careful about the use of the term marginalization and note that “individuals and communities are marginalized by, live in marginalized conditions or are forced into marginalization rather than being labelled as marginalized”.1

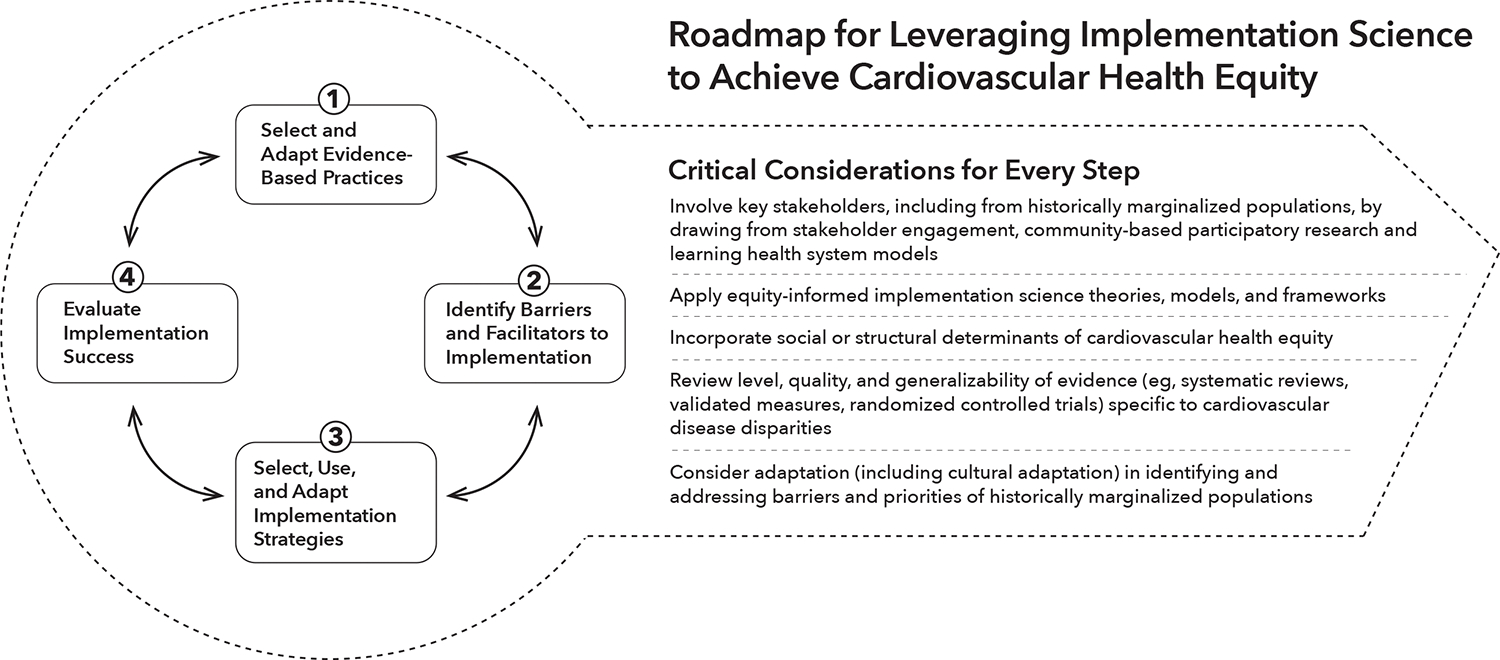

Concurrent with the review, our writing group met regularly from April 2021 to December 2021 to refine the search process, review and discuss articles retrieved from the review to ensure relevance, and propose additional articles based on group members’ knowledge of the field. The group used a consensus process to develop a roadmap for distilling implementation science and equity concepts for clinical audiences. Based on a few key publications we identified on implementation science and health equity,10, 14, 21–23, 25, 29–32 we identified 4 major implementation science steps and key equity considerations (Figure 1, Table 2). These steps include: (1) selecting and adapting EBPs shown to reduce disparities or improve CVD outcomes in historically marginalized populations; (2) identifying barriers and facilitators to implementing EBPs for CVD equity; (3) selecting, using and adapting implementation strategies; and (4) evaluation of implementation success. Though not a unique step, we considered stakeholder (e.g., public health and healthcare practitioners, patients, caregivers, policy makers, and payers across multiple cultures)33 engagement as a critical component of each step. We reviewed the extant literature for each step (see Supplementary Material) to identify reviews and articles. As depicted in Figure 1, the steps are meant to be bidirectional (e.g., step 4 implementation failure may warrant step 3 strategy adaptation or even step 2 re-evaluation of barriers and facilitators).

Figure.

Roadmap for leveraging implementation science to achieve cardiovascular health equity and critical equity considerations for every step.

Table 2.

Key considerations for conducting implementation science research to achieve cardiovascular health equity

|

(1) Select and Adapt an EBP □ Has the EBP proven effective at: closing disparity gaps (between historically marginalized population and non-historically marginalized population) or improving outcomes within historically marginalized population AND is there an evidence-to-practice gap (e.g., is the EBP being delivered equally and as intended in historically marginalized population to address CVD inequities)? □ Does the EBP mitigate social or structural barriers faced by historically marginalized populations? □ Was selection of the EBP based on high level/quality and generalizable efficacy/effectiveness studies in the historically marginalized population of interest (e.g., are there meta-analyses/systematic reviews/simulation modeling/cost-effectiveness analyses/practice guidelines available that support implementation readiness? Is there evidence that the EBP does not worsen disparities)? □ Did researchers examine needs, priorities, and values of historically marginalized populations, address power dynamics, align priorities among researchers, policymakers and community members when selecting the EBP (e.g., What are stakeholders’ perceptions of the EBP itself—lack of stakeholder interest may suggest that you have selected an inappropriate EBP). □ Has the EBP been culturally adapted or targeted to address barriers unique to historically marginalized population of interest and CVD disparities experienced at the intersection of individuals identities? □ Is the EBP informed by an equity-informed conceptual model or framework? □ Did the effectiveness studies examine meaningful CVD equity outcomes (e.g., avoid use of equity proxies). |

|

(2) Assess Barriers and Facilitators □ Is there a lack of understanding as to why an EBP isn’t being delivered equally or as intended in a given historically marginalized population? □ Were contextual factors beyond traditional system, provider and patient level determinants of implementation gaps examined (i.e., social and structural determinants of health)? □ Were the barriers and facilitators to implementation in a historically marginalized population generalizable and determined using rigorous methods (e.g., rigorous qualitative methods, systematic reviews of barriers and facilitators to summarize barriers and facilitators in historically marginalized population)? □ Were key stakeholders from historically marginalized populations engaged in the process of assessing barriers and facilitators? □ Is lack of cultural adaptation a key reason an EBP is not being implemented? Has a needs assessment been conducted to understand how and why an EBP needs to be redesigned/adapted to address barriers specific to historically marginalized population? □ Were equity-informed theories, frameworks, or models used to examine contextual and behavioral determinants of implementation? □ Were rigorous mixed methods used to examine barriers, facilitators, and contextual factors in historically marginalized population? |

|

(3) Select, Use and Adapt Implementation Strategies □ Was the strategy differentiated from the EBP and selected to address unique barriers and facilitators to implementation in a given context or historically marginalized population? □ Does the strategy mitigate social or structural determinants of suboptimal uptake of a given EBP? □ Was the selection of the strategy based on preliminary, high-level/quality/generalizability of evidence for strategy effectiveness, particularly in historically marginalized population? □ Were key stakeholders involved in selecting and using the implementation strategy, particularly using stakeholder engaged strategy selection methods (i.e., conjoint analysis, implementation mapping, group modeling)? □ Is the strategy culturally/contextually relevant, adapted to support implementation in a given historically marginalized population or setting or both? □ Was a theoretical framework used to identify, design and use the implementation strategy? □ Was the strategy identifiable and specified (e.g., actor, implementation outcome targeted, timing, dose, frequency)? |

|

(4) Evaluate Implementation Success □ Did researchers examine the why, the how and the extent to which and the mechanisms by which a given strategy, approach, or adaptation succeeded or failed in equitably improving uptake of an EBP in a given historically marginalized population or setting (e.g., do all the settings/staff have the capacity and resources to deliver the EBP on an ongoing basis)? □ Did researchers examine how and whether social and structural determinants of health influenced implementation outcomes? □ Were high-quality study designs considered and valid measures of CVD and implementation outcomes used to support replicability and reliable results in historically marginalized population? □ Were key stakeholders, including historically marginalized populations, engaged in the process of evaluating implementation processes and outcomes? □ Were EBP and strategy adaptations considered, tracked, measured, and recorded? □ Was a theoretical framework used to evaluate impact of the implementation strategy and EBP on CVD disparities? □ Were key implementation outcomes examined from an equity lens (e.g., EBP sustainability, reach, costs, fidelity, acceptability in historically marginalized population) not just CVD outcomes? If CV health outcomes were evaluated (e.g., in a hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial), was the study powered to examine improvement in historically marginalized populations or reductions in CVD disparities between historically marginalized population and non-historically marginalized population? |

ROADMAP FOR LEVERAGING IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE TO ACHIEVECARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH EQUITY

Figure 1 outlines a 4-step roadmap to leveraging implementation science to achieve equity in CV health. For all steps, we highlight critical equity considerations (Table 2), including involvement of key stakeholders to improve the rigor in which CV health equity research is conducted and evaluated.

Step 1. Selecting and Adapting EBPs to Promote CV Health Equity

Key questions in identifying whether to select an EBP to advance health equity is whether the EBP is (1) specifically designed to effectively close a disparity gap or improve outcomes within historically marginalized populations (2) sub-optimally implemented in historically marginalized populations or (3) both.21 Selecting an appropriate EBP involves collecting rigorous evidence for the quality, strength and generalizability of effectiveness findings. This also involves making the case that the suboptimal implementation of a given EBP is generalizable (i.e., not just a quality improvement problem in a single healthcare system, but with broader implications for implementation across healthcare systems and communities). Critical to selecting EBPs is understanding the processes, people and structures that decide whether and how implementation will be carried out and considering the ways in which some stakeholders may benefit from structures that propagate inequities. This process involves critical self-reflection by team members, inclusion of diverse members, less hierarchical decision-making processes, recognizing power imbalances and seeking to even them out, and a focus on holding institutions/systems accountable to equity.34

Most CVD EBPs are not developed for or tested in culturally diverse groups that often face unique barriers to achieving CV health due to social and political factors.35 If suitable EBPs do not exist, it may be necessary to adapt an existing EBP. Adaptation,3–5 including cultural adaptation, involves reviewing and changing the structure of an EBP to more appropriately fit the needs, preferences, resources, beliefs, norms, and customs of a particular group or setting.4, 5 There are several multi-step frameworks and “best practices” to guide adaptation including: 1) engaging stakeholders/assess community; 2) adapting, translating and pilot testing materials for specific groups; 3) mitigating barriers to participation in target groups; 4) understanding EBP components and deciding what if anything to adapt (e.g., content, mode delivery, setting); and 5) tracking and evaluating the adaptation process.5, 36, 37

Step 2. Identifying Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing EBPs that Promote CV Health Equity

The next step involves identifying barriers and facilitators (referred to as determinants or “contextual factors” in the implementation science literature) to implementation of the EBP and using this information to guide both the selection of implementation strategies (step 3) and if needed the adaptation of the EBP itself to fit local needs. Theory-driven and stakeholder-engaged approaches may be particularly useful to elucidate why EBPs are sub-optimally—or not at all—implemented in historically marginalized populations. Of great relevance to health equity is the application of an intersectionality lens to existing frameworks to better account for how intersecting social experiences and identities (e.g., race, class, gender, sexuality) affect stakeholders, patients, and clinicians alike.38, 39 To truly advance CV health equity, recent equity-informed frameworks also call for identifying and mitigating barriers in upstream SDoH, which are often the root causes of CV health inequities that drive implementation gaps.26, 29

Several guides exist for selecting the appropriate framework, including model selection webtools.40 Moullin and colleagues provide practical guidance, in the form of ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks in research and practice.41 Successful evaluation of contextual factors requires partnering with qualitative and social sciences experts to apply rigorous qualitative and mixed methods (e.g., focus groups, site visits, surveys, semi-structured interviews) to collect data specified in the frameworks above.42 Further discussions/examples of frameworks in implementation science and health equity are included throughout this statement and summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Future application of these frameworks will establish their validity, indications, as well as pros and cons of use.

Step 3. Selecting, Using and Adapting Implementation Strategies that Promote CV Health Equity

Implementation strategies can be identified, built, used, and often adapted to help put the EBP(s) identified in step 1 into place while considering the barriers and facilitators identified in step 2. Powell and colleagues describe 73 discrete implementation strategies to implement EBPs,15 including reminders for clinicians, promotion of adaptability, and quality monitoring/improvement. For example, a study may examine the effect of practice facilitation—an implementation strategy whereby experts help clinicians solve problems related to capacity building and clinic workflow challenges15 to enhance adoption of guidelines for aspirin use, blood pressure, cholesterol or smoking (the EBP).43, 44 To achieve CV health equity, implementation strategies themselves should be culturally and contextually relevant, address social and structural determinants of implementation in historically marginalized populations and fit within the identified setting. Several guides exist for engaging stakeholders in mapping implementation strategies to barriers identified in step 2.45 Stakeholder relationships across sectors will also be essential to delivering/using and testing strategies while tracking adaptations and refining them based on collected data and feedback.

Step 4. Evaluating Implementation Success

Finally, evaluation involves determining whether an implementation strategy improved the feasibility, acceptability, adoption, fidelity (or adherence to the EBP protocol), costs, sustainability and appropriateness of the EBP5, 13, 20; these outcomes are distinct from effectiveness outcomes related to improvements in health behaviors and CVD indices.13 Further, researchers should examine whether implementation outcomes, like fidelity or adherence to guidelines, differ between historically marginalized and non-historically marginalized populations. This process goes beyond patient-level (e.g., medication adherence) outcomes and requires assessment of multi-level (i.e., patient, clinician, system) equity indices in organizational, community, policy or multiple settings.25 Sustainability and equity-informed implementation science frameworks (Supplementary Table 1) and rigorous mixed methods are essential to elucidating the mechanisms by which implementation failed or succeeded, and to examining fluctuations in perceived barriers and facilitators (see step 2) to implementation once an implementation strategy is in place.42 Qualitative, objective or passive data collection of both implementation and effectiveness outcomes at multiple levels can be supported by community-based participatory research or learning health system model approaches.7, 16 Researchers should also consider using existing data or simulation modeling to evaluate implementation gaps and success.46 Finally, “unintended consequences” of implementation studies should be examined, given that disparities may worsen when EBPs or implementation strategies are not designed to meet the needs, priorities, and available resources of the target group (particularly for historically marginalized populations) or setting.25, 47

In the sections below, we provide examples for each step in our roadmap. We aimed to provide examples from policy, community, organizational or multiple settings which often have distinct equity considerations. We then highlight key gaps in the literature and suggest areas for future effectiveness and implementation research.

APPLICATION OF ROADMAP STEP 1: SELECTING AND ADAPTING EBPS TO PROMOTE CV HEALTH EQUITY

Below, we apply our roadmap and equity considerations (Figure 1, Table 2) to analyze the quality and implementation readiness of a few EBPs specifically designed to address CVD disparities

Multi-Setting EBPs

Key to selecting an EBP across all settings is identifying its effect on CVD disparities. Informed by the ecologic model, one systematic review identified EBPs addressing multi-level determinants of BP disparities in multiple settings; of 39 interventions, only 6 reported effects on disparities – 3 reduced, 3 increased or had no effect on disparities.48 This review provides an example of critical gaps in our understanding of whether EBPs reduce CVD disparities but also illustrates the need to highlight interventions that worsen disparities in preparation for de-implementation.8 The article also touches on issues of representation/inclusion (i.e., most studies were conducted in predominantly African American groups). Future application of our roadmap will require that such reviews explicitly comment on EBP strength/quality, generalizability, and readiness for implementation, to guide stakeholders in EBP prioritization and selection.

Policy EBPs

One equity consideration particularly salient to policy EBPs is the need to target SDoH. The Department of Housing and Urban Development randomized families living in public housing in high poverty census tracts to receive rent-subsidy vouchers to move to low-poverty neighborhoods versus rent-subsidy vouchers with no moving restrictions versus a control group that was offered no new assistance.49 Follow-up in 2008–2010 indicated that those randomized to the low-poverty voucher had lower rates of obesity and glycated hemoglobin levels than controls, suggesting that this EBP is effective in primary prevention of CVD. In examining whether EBPs like this are ready for implementation, one must consider priorities and needs of key stakeholders, replicability, unintended negative consequences (e.g., sense of community and emotional health), as well as adaptations needed to improve the fit of this intervention in other populations or non-urban settings. Key considerations include examining power dynamics and structural racism that may drive suboptimal implementation of policy based EBPs.

Community EBPs

Many community-based interventions solely target individuals (vs. families or settings), limiting their ability to achieve CVD equity. A 2014 systematic review of community-based interventions to improve CVD health behaviors/risk factors among black, indigenous and people of color, low socioeconomic status, low literacy, or geographically isolated or impoverished areas populations found mostly multi-component, individual-level interventions involving patient education, counseling and support or exercise classes, with interventions aimed at reducing BP the most promising and those aimed at behavior change the least.50 Per our roadmap, the review commented on intervention levels, settings, rigor (most were proof-of-concept, efficacy trials), generalizability and representation, all of which are needed to prepare for implementation. Future reviews of community-based EBPs should comment on whether the EBP leveraged assets in a given community, targeted SDoH, and examined meaningful equity outcomes (i.e., impacted SDoH and CVD disparities between historically marginalized and non-historically marginalized groups).

In an example of a community-based, implementation-ready EBP that leveraged historically marginalized population assets, Black-owned barbershops were linked to community-based pharmacists; the authors found that intervention barbershops attained a 68% BP control prevalence after 1 year of intervention, whereas control barbershops attained only 11% prevalence (<130/80 mmHg).51 As for readiness of implementation, this study used rigorous trial methods and engaged key stakeholders. Generalizability to other settings and groups will need to be examined.

Particularly salient to community-based EBPs is the possible need for cultural adaptation to fit community needs. One multi-sector coalition of academic institutions, community-based organizations, and Asian American-serving faith-based organizations adapted nutrition and hypertension EBPs for local Asian American communities.52 The coalition used marketing and community-based participatory research to guide the adaptation process, which involved translating health materials into four relevant languages, emphasizing cultural values to frame goals, offering traditional, healthy foods during communal meals, and enhancing roles for faith-based organization leadership. Per our roadmap, this process was informed by an adaptation framework to support replicability and widespread implementation, the results of which are described below in step 3.

Organizational EBPs

Many EBPs were tested in healthcare settings, focus on quality improvement, and align with reimbursement models that make them ripe for implementation. In a secondary prevention example, Sisk and colleagues conducted a study of non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults with heart failure in Harlem, New York. Patients were interviewed about knowledge and behaviors; medical records were evaluated for appropriate medication prescriptions. The intervention consisted of nurse-led heart failure management (i.e., diet, medication, self-management, follow-up telephone calls) and resulted in significant reductions in hospitalizations over 12 and 18 months.53 While likely not generalizable beyond Black and Hispanic adults, this was a high-quality, adapted (to local diets), stakeholder-engaged randomized control trial that may be ready for widespread implementation and sustainability. However, organizational EBPs like these often face the challenge of identifying how best and whether to incorporate SDoH (e.g., literacy, access to healthy foods or low-cost medications), an area ripe for adaptation.

One example of how adaptation might be achieved is Aschbrenner and colleagues’ application of the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications-Expanded (FRAME) to addressing inequities in adoption of EBPs related to SDoH. The team categorized adaptations to a behavioral EBP targeting obesity in persons with serious mental illness. The authors found that social and economic disadvantage were key obstacles to exercising in facilities, which was addressed by adapting the EBP to offer sessions at the mental health center.47

APPLICATION OF ROADMAP STEP 2: IDENTIFYING BARRIERS AND FACILITATORS TO IMPLEMENTATION

Barriers to Implementing EBPs across settings

Across all settings, theoretical frameworks are essential for comprehensively and mechanistically examining implementation barriers, facilitators, and processes. A systematic review of studies examining the implementation of community health worker programs (an EBP shown to reduce health inequities) into healthcare settings found that only 6 of the 50 studies used implementation science frameworks.54 Along with frameworks, community-based partnerships will be important for understanding the needs, priorities, and values of historically marginalized populations; aligning priorities; and identifying determinants of suboptimal implementation.

Barriers to Implementing Community EBPs

Community settings often face multi-level barriers limiting the utility of one-size-fits-all interventions. In stakeholder interviews of 62 residents in rural communities in Missouri, authors found that barriers to adopting physical activity guidelines differed by town and were related to community size, resources like formal organizations to promote physical activity and infrastructure, particularly in impoverished settings.55 Nonetheless, both individual-level barriers like motivation, life priorities, health status, knowledge, and time as well as environmental barriers such as location, accessibility and safety were salient, suggesting the need for multi-level interventions (e.g., community fairs, park clean up days, etc). Applying the recent intersectionality-informed Theoretical Domains Frameworks38 to these findings might elucidate whether these barriers differ by social experiences and identities.

Barriers to Implementing Organizational EBPs

Several determinants to implementing EBPs that reduce CVD disparities in organizational settings are emerging. While not informed by a framework, a qualitative analysis of stakeholder interviews with several national healthcare organizations tasked with improving CVD and diabetes quality found that key determinants of reducing disparities included external accountability, alignment of incentives with quality/disparities reduction, organizational commitment, population health focus, and use of race/ethnicity data to inform solutions.56 Future examination should consider barriers related to SDoH and use of theoretical frameworks like race-conscious Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [CFIR] to elucidate determinants like leaders’ unwillingness to implement EBPs specific to historically marginalized populations.57

Overall, while work is evolving, we found a dearth of examples of theory-informed, rigorous qualitative studies summarizing barriers and facilitators to implementing EBPs that promote CV health equity, particularly those related to SDoH and policy EBPs.

APPLICATION OF ROADMAP STEP 3: SELECTING, USING AND ADAPTING IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES

Below, we present a set of examples of implementation strategies across multiple settings aimed at promoting the uptake of EBPs in historically marginalized populations. Achieving CVD equity requires a shift from solely examining the effect of an intervention on CVD outcomes (see Step 1) to examining whether the EBP was equitably and sustainably adopted in a group or setting. For each study, writing group members categorized implementation strategies based on Powell and colleagues taxonomy of strategies to illustrate the difference between EBPs and strategies, prompt shared language in our field, and allow for comparisons between studies.15 We then applied our checklist of critical equity considerations (Table 2) to identify gaps in the implementation literature to date (Table 3).44, 52, 58–66

Table 3.

Identifying implementation strategies and applying critical equity considerations to studies aimed at improving the uptake of evidence-based practices for reducing cardiovascular disease disparities

| Implementation Science Equity Considerations | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | EBP (setting) | Possible Implementation Strategy according to Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) (Definition) | Implementation Strategy Description | Theory-informed | Stakeholder engagement | Adaptation/Fit | Specified implementation strategy details (actor, dose, frequency) | Targets SDoH | Evidence Level/Quality of study design AND strategy | Improved EBP implementation AND CVD outcomes AND disparities among historically marginalized populations | Funding Source |

| Multi- and Community Settings | |||||||||||

| Jenkins (2004) 62 | Diabetes guidelines-A1c, BP, lipid testing/ control (Urban/rural communities in South Carolina) | Coalition Building (recruit and cultivate relationships with partners in the implementation effort) | Combined health care and academic institutions, community- and faith-based organizations, civic groups, government, and business organizations; focused on coalition power, expansion, advocacy, and sustainability | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes (access, social support, finances) |

Study: Low (non-randomized comparison) Strategy: Low (quality/ evidence supporting selection not reported) |

EBP: Yes (diabetes diagnosis and prevention guidelines like eye exams) CVD: Yes (lipid, BP and A1c control) Reduced disparities: Mixed results based on outcome |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Prepare patients/consumers to be active participants (prepare patients/consumers to be active in their care, to ask questions, and specifically to inquire about care guidelines, the evidence behind clinical decisions, or about available evidence-supported treatments) | Community development, empowerment, and education by CHWs, nurses to build skills and promote self management- like health fairs, support groups, educational programs | ||||||||||

| Audit and Feedback (collect and summarize clinical performance data over a specified time-period and give it to clinicians and administrators to monitor, evaluate, and modify provider behavior) | Chart audits and feedback to primary care partners and patients to promote healthcare systems change | ||||||||||

| Centralized Technical Assistance (develop and use a centralized system to deliver technical assistance) | Focused on implementation issues to team of coordinators/advocates providing education by CDC | ||||||||||

| Access new Funding (access new or existing money to facilitate the implementation) | Federal and local funding to support implementation | ||||||||||

|

Kwon (2017)

52

Yi (2019) 53 |

Healthy food policies and hypertension management program (Faith-Based Organizations of Asian Americans) |

Coalition Building (recruit and cultivate relationships with partners in the implementation effort) | Coalition of funders, social service agencies, academic partners, community-based organizations, and advocacy organizations | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes (access to healthy foods) |

Study: low (pre-post) Strategy: Low (quality/ evidence supporting selection not reported) |

EBP: Yes (uptake of screening, health promotion activities, food labels/signs but varied by denomination/ Asian-American sub-groups) CVD: Yes (pre-post BP, varied by Asian American subgroup) Reduced disparities: Unclear |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences |

|

Use train-the-trainer strategies (train designated clinicians or organizations to train others in the clinical innovation) |

Train-the-trainer (i.e., congregants) on blood pressure screening program to promote community-clinical linkage | ||||||||||

| Promote Adaptability (identify the ways a clinical innovation can be tailored to meet local needs and clarify which elements of the innovation must be maintained to preserve fidelity) | Adaptation program (e.g., incorporated costs/benefits of healthy eating and integrated into program) | ||||||||||

| Record (2015) 63 | Hypertension, cholesterol, smoking, diet, and physical activity guidelines (low-income, rural community settings in Maine from 1970–2010) | Coalition Building (recruit and cultivate relationships with partners in the implementation effort) | Integrated clinical/ community resources, hospital-supported healthy community coalition; | No | Yes | Unknown (included “indigent residents”) | No | Yes (access, insurance) |

Study: Low (pre-post) Strategy: Low (quality/ evidence supporting selection not reported) |

EBP: Yes (CVD screening) CVD: Yes (BP control, cholesterol and smoking quit rates over time) Reduced disparities: Unclear (though rates improved compared to other counties in Maine) |

Office of Economic Opportunity and the Rural Health Care Service Outreach Grant |

| Use capitated payments (pay providers or care systems a set amount per patient/consumer for delivering clinical care) | Capitated health insurance plans for indigent and employed | ||||||||||

| Develop and organize quality monitoring systems (develop and organize systems and procedures that monitor clinical processes and/or outcomes for the purpose of quality assurance and improvement) | Continuous quality improvement, medical practice self-audit, information systems to facilitate risk assessment, longitudinal tracking, and reporting | ||||||||||

| Conduct educational outreach visits (have a trained person meet with providers in their practice settings to educate providers about the clinical innovation with the intent of changing the provider’s practice) | Trained indigenous outreach workers in communities/primary care practices; health coaches/ nurses for education and site visits; in-class tobacco curriculums, volunteer citizens heart healthy menu campaigns, health van screenings | ||||||||||

| Policy Setting | |||||||||||

| Johnson (2012) 64 | Chronic disease management (e.g., diabetes, asthma, congestive heart failure) (Medicaid managed care enrollees in New Mexico) | Use capitated payments (pay providers or care systems a set amount per patient/consumer for delivering clinical care); alter Incentive/allowance structures (work to incentivize the adoption and implementation of the clinical innovation) | State negotiated with the state Medical Assistance Division to establish a billing code for the program to hire and reimburse community health workers (CHWs) per member per month | No | Yes | Unknown | No | Yes (access, social support, literacy) |

Study: Low (non-randomized) Strategy: Low (quality/evidence supporting selection not reported) |

EBP: Yes (uptake of CHWs) CVD: No or unknown Reduced disparities: Unclear |

DHHS-HRSA Health Community Access Program; WK Kellogg Foundation |

| Organizational Setting (Primary Prevention) | |||||||||||

| Bartolome (2016) 59 | Hypertension control guidelines (primary care healthcare practice in California) | Distribute educational materials (including guidelines, manuals, and toolkits in person, by mail, and/or electronically) | Provider and staff education by physician champions, disseminating guidelines | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes (access) |

Study: Low (pre-post) Strategy: Low (quality/evidence supporting selection not reported) |

EBP: Yes (BP quality metrics and processes improved) CVD: Yes (BP control) Reduced disparities: Yes |

Department of Hospitals, Quality and Care Delivery Excellence, Kaiser Permanente |

| Revise professional roles (shift and revise roles among professionals who provide care, and redesign job characteristics) | Define role and responsibilities, staff engagement, build strong care teams, redesign care delivery like task shifting and interval BP visits with staff | ||||||||||

| Promote Adaptability (identify the ways a clinical innovation can be tailored to meet local needs and clarify which elements of the innovation must be maintained to preserve fidelity) | Communication model to build awareness of black culture and improve communication and build trust based on systematic review | ||||||||||

|

Boonyasai (2017);

60

Cooper (2013) 61 |

Hypertension measurement and control guidelines (6 primary care clinics in Baltimore) | Audit and Feedback (collect and summarize clinical performance data over a specified time-period and give it to clinicians and administrators to monitor, evaluate, and modify provider behavior) | Dashboard of disparities (i.e., race-stratified hypertension dashboard) and web-based video training targeting communication skills that promote patient adherence | Yes | Yes (advisory board) | Yes (tailored strategy to address disparities at patient, provider, clinic level) | No | Yes (literacy, access, resource guide/care manager for complex psycho-social needs) |

Study: Low (pre/post) Strategy: High (selection informed by CVD inequity evidence) |

EBP: Yes (use of devices, checking BP) CVD: Yes (BP control) Reduced disparities: Unclear |

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute |

| Distribute educational materials (including guidelines, manuals, and toolkits) in person, by mail, and/or electronically | Provider education/communication training (e.g., web-based video training targeting communication skills that promote patient adherence) | ||||||||||

| Alter incentive/allowance structures (work to incentivize the adoption and implementation of the clinical innovation) | Financial incentives for providers for referrals | ||||||||||

| Cykert (2020) 44 | Hypertension control, aspirin for established CVD, and counseling for tobacco cessation (217 small, primary care clinics in North Carolina) |

Practice Facilitation (a process of interactive problem solving and support that occurs in a context of a recognized need for improvement and a supportive interpersonal relationship | Quality improvement techniques with clinics | No | Unknown | No | No | No |

Study: High (stepped wedge design) Strategy: Moderate (report evidence for practice facilitation, unclear if reduces disparities) |

EBP: Yes (statin/aspirin prescriptions/BP control) CVD: Yes (ASCVD risk) Reduced disparities: Unclear |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| Data warehousing techniques (integrate clinical records across facilities and organizations to facilitate implementation across systems) | Dashboard identifies ASCVD | ||||||||||

| Ogedegbe (2014) 67 | Hypertension guidelines (Black patients at 30 community health centers) | Distribute educational materials (including guidelines, manuals, and toolkits) in person, by mail, and/or electronically | Multi-level intervention of computerized patient education, home BP monitoring, and individual and group behavioral sessions on lifestyle modification; provider monthly case rounds and feedback on process measures/home BP measures | Yes (chronic care model, reviewed multi-level determinant of adherence) | Yes (trained health center staff) | No | No | No |

Study: High (cluster randomized trial) Strategy: Low (quality/evidence for educational strategy unclear) |

EBP: No (no impact on Treatment intensification, medication adherence) CVD: No effect on BP control Reduced disparities: unclear, only black participants |

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities |

| Audit and Feedback (collect and summarize clinical performance data over specified time-period and give to clinicians/administrators to monitor, evaluate, and modify provider behavior) | |||||||||||

| Organizational Setting (Secondary Prevention/Treatment) | |||||||||||

| DeVore (2021) 66 | Heart Failure guidelines (82 intervention hospital settings) | Distribute educational materials (including guidelines, manuals, and toolkits) in person, by mail, and/or electronically | Site level clinician education | No | Yes | No | No | No |

Study: High (cluster randomized trial) Strategy: Low (quality/evidence supporting selection not reported) |

EBP: No difference in quality-of-care metrics between intervention and control hospitals) CVD: No difference in heart failure hospitalizations or mortality Reduced disparities: unclear, though no differences by race- 38% Black participants |

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation |

| Audit and Feedback (collect and summarize clinical performance data over a specified time-period and give it to clinicians and administrators to monitor, evaluate, and modify provider behavior) | Monthly reports on processes and outcomes for guideline-based heart failure care | ||||||||||

| Develop and organize quality monitoring systems: (develop and organize systems and procedures that monitor clinical processes and/or outcomes for the purpose of quality assurance and improvement) | Quality improvement strategic planning with site-specific gap analysis and action plans | ||||||||||

| Howard (2018) 65 | Evidenced based stroke management (tissue plasminogen activator, antithrombotic, statins) (hospital settings) | Distribute educational materials (including guidelines, manuals, and toolkits) in person, by mail, and/or electronically | Get with the Guidelines-Stroke Education / Patient Management Tool on treatment | No | Yes | No | No | No |

Study: Low (observational) Strategy: Low (quality/evidence supporting selection not reported) |

EBP: Unclear (Overall TPA, education, evaluation by neurologist, etc with no difference by race) CVD: CVD outcomes not reported Reduced disparities: unclear, though no differences by race |

National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; American Heart Association |

| Alter incentive/allowance structures (work to incentivize the adoption and implementation of the clinical innovation) | Hospital recognition program | ||||||||||

|

Inform local opinion leaders (inform providers identified by colleagues as opinion leaders or “educationally influential” about the clinical innovation to influence colleagues to adopt it) Use advisory boards and workgroups (create and engage formal group of multiple kinds of stakeholders to provide input and advice on implementation efforts and to elicit recommendations for improvements) |

Organizational stakeholder and opinion leader meetings, collaborative workshops for hospital teams | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: CVD Cardiovascular Disease; EBP Evidence based practices; SDoH social and structural determinants of Health; TPA tissue plasminogen Antigen

Strategies identified in policy, community, organizational or multiple settings

First, we illustrate that implementation is often setting specific. For multi-, policy and community settings, there is often a need for strategies centered around meaningful partnerships between community, educational, healthcare government and local institutions/organizations.2, 52, 61, 62 Sustained impact also requires policy-driven, fiscal strategies. For example, one study demonstrated that imbedding CHWs into clinical settings to screen/address SDoHs (the EBP) could be implemented, sustained and scaled up throughout New Mexico’s Medicaid system and beyond by incorporating costs into capitated payments to managed care and using contract-based hiring of CHWs into clinical care (implementation strategy).63 For organizational EBPs, we identified several effective multi-component strategies, including a combination of clinician education, care team re-organization, case-management by non-physician team members (e.g., pharmacists, dieticians), communication training, clinical decision-support, audit and feedback (e.g., of a race-specific dashboard), healthcare delivery redesign, cultural tailoring and standardized protocols.58–60, 64, 65 Further work is needed to identify methods for sustained delivery of these strategies in diverse healthcare systems.

Equity considerations in implementation and quality improvement studies

In applying our equity considerations to the examples above, we found that most studies successfully engaged stakeholders in strategy design and addressed SDoH but few employed rigorous trial design to test high-quality, adapted, theory-informed strategies selected to target known implementation barriers. In addition, none of the implementation strategies were specified (i.e., who delivered them, how often, when) (Table 3). These equity implementation considerations are essential to replicability, refinement, and a better understanding of the mechanistic underpinnings of findings (e.g., did disparities improve because of improved adoption of EBPs?). For those studies with null results, our roadmap calls for re-examination of prior steps and use of theoretical frameworks to elucidate how or why implementation failed and for which outcomes to spur adaptation or selection of different implementation strategies.

APPLICATION OF ROADMAP STEP 4: EVALUATING IMPLEMENTATION SUCCESS

In this section, we highlight several theoretical frameworks and design features for evaluating implementation success.

Using mixed methods informed by evaluation frameworks can elucidate how and why an implementation effort to reduce disparities succeeded or failed. In an example of a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study, Glasgow and colleagues used the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework to evaluate the effect of an implementation strategy involving stakeholder engagement, a remote tool, and cultural tailoring on adoption of a weight loss and hypertension self-management EBPs in urban community health centers. The authors demonstrated high clinician referral to the program (adoption), higher fidelity/completion in lower-income participants (implementation), and significant improvements in BP control at 24 months which did not differ by race/ethnicity, income, gender, income or language (effectiveness) but the effects were not sustained beyond the study period (maintenance). Recent efforts to apply equity and sustainability considerations to the RE-AIM framework call for mixed methods to pose questions like whether low-resourced settings/staff have the capacity and resources to deliver an EBP in on an ongoing basis.67

Frameworks can also be leveraged to describe intervention design aspects and propose adaptations needed for widespread implementation. In a narrative review of community-based behavioral and educational interventions to promote hypertension control in immigrant populations, Ali and colleagues used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [CFIR] to propose key innovations, including adapting to unique socio-demographic and acculturation level of immigrant communities, exploring new intervention designs (both shorter and longer, culturally sensitive activities), employing different types of intervention delivery agents from the community, collaborating with diverse stakeholders at multiple stages of the research process, and using mixed methods to efficiently adapt the intervention.68 Future work should consider how these innovations might target SDoH like education, income and housing.

Finally, implementation science research may benefit from rigorous but more feasible designs like stepped wedge designs (e.g., clusters of clinics are sequentially exposed to an intervention over time).18 In one stepped wedge cluster randomized trial combining practice facilitation and a population-based dashboard for risk stratification found substantial atherosclerotic CVD risk reduction in high-risk patients in small, rural practices.44 While stepped wedge designs are increasingly used in implementation science, researchers need to be aware of the power considerations, inefficiencies when clusters are few, and confounding by temporal trends in policy, service delivery and other external factors.18 Future work should consider incorporating an evaluation framework. For example, in another practice facilitation study of New York City’s HealthyHearts initiative to improve adoption of CV disease EBPs in diverse primary care practices, the authors used the Conceptual Framework for Implementation Fidelity to specify frequency, duration, content and coverage of the implementation strategy (practice facilitation) itself, finding that most practices received an adequate dose of the strategy.43 Inadequate fidelity to the strategy itself can often explain why an implementation study fails.

SUMMARY OF GAPS IN THE LITERATURE/RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

In this statement, we propose key steps and critical equity considerations for using implementation science to achieve CV health equity. We illustrate how best to apply our checklist in organization, community, policy or multiple settings, drawing on decades of intervention, quality improvement and implementation research in CVD disparities. Below we summarize key gaps in the literature and provide several important recommendations.

First, while we highlight examples of studies examining or targeting SDoH (e.g., housing vouchers), this is still an emerging area of interest. Progress will require conceptual clarity around how to address, collect, and track SDoH in future implementation science studies. This can be facilitated by emerging validated, freely available measures of SDoH such as those in the most recent version of the PhenX Toolkit.69 Calls are out for better examination and targeting of structural racism, a key driver of CVD disparities, and for incorporating anti-racist approaches to implementation science methods.19, 26 Salient to the cardiovascular field is better elucidating whether targeting SDoH differentially or additively impacts health behaviors, cardiometabolic risk factors, and cardiovascular events.

Second, while we did not conduct a systematic review, most of the identified studies across all steps focused on Black, Hispanic, rural or low-income groups. Future studies should examine groups with disparately high CVD burden or suboptimal adoption of CVD EBPs, such as American Indians/Alaska Natives, Asian or Pacific Islander communities, both urban and rural settings,2 as well as sexual and gender minority populations.70

For step 1, we demonstrate the equity-informed criteria for selecting EBPs that are sub-optimally implemented yet effective in historically marginalized populations. Our findings highlight the need for better specification of EBP quality, generalizability and implementation readiness in clinical trials and systematic reviews. Drawing from community-based participatory research methods,7 further work is needed to understand how best to engage stakeholders in selecting and often adapting EBPs that impact multiple CVD indices. While most of the identified EBPs (and implementation strategies) focused on health behaviors, cardiometabolic risk factors (specifically hypertension & diabetes), stroke, or heart failure, identifying other targets for EBP implementation, such as peripheral vascular disease, myocardial infarction, and behavioral cardiology, will be essential. Finally, we found few examples of studies adequately powered to examine whether EBPs and implementation strategies, particularly those that target SDoH and impact CVD disparities, an area ripe for hybrid effectiveness-implementation trials.12 The field will need to reconcile the need for proven efficacy in historically marginalized groups often underrepresented in these trials with the need to rapidly proceed to implementation of EBPs in the face of markedly suboptimal uptake and CVD disparities.

For step 2, we also found suboptimal use of implementation science frameworks and rigorous qualitative methods in evaluating barriers and facilitators to implementation, particularly in policy settings. In examining determinants of implementation, policymakers and thought leaders in communication with other stakeholders will need to consider how and whether the inability to scale housing (or education, affordable care, income) programs, which require political willpower and funding, demonstrates the unwillingness to dismantle racist policies that contribute to CVD disparities. Future research should continue to leverage community/stakeholder engagement and use frameworks from implementation science and health equity to understand barriers, facilitators and other contextual factors (like resources, costs, SDoH) around implementation and to design theory-informed implementation strategies that promote better understanding of mechanisms by which studies address CVD disparities. There have been calls for consolidating and sharing knowledge on barriers and facilitators to implementation across multiple (vs. single) settings to prepare for scaling out implementation strategies and EBPs,71 which may also provide an avenue for early-stage investigators with pilot or training grants to significantly contribute to the field.

For step 3, we found a dearth of theory-informed, high-quality studies on selecting, using, and adapting implementation strategies to improve equitable adoption of CV health EBPs, particularly those that sought to understand the reach, quality, implementation processes, and sustainability in historically marginalized populations. Nonetheless, we provide a guide for helping audiences distinguish implementation strategies from EBPs, identifying active ingredients using shared language and employing more rigorous designs.15 We also found numerous protocol papers of trials testing implementation strategies, the results of which will likely impact clinical practice but also our understanding of how implementation science can best be suited to achieve CV equity. For implementation scientists, the taxonomy of implementation strategies and methods for selecting and tailoring strategies15 may need to be refined, adapted, and/or expanded to better fit equity research. Future research should continue to identify implementation strategies best suited (or not) for particular settings (community vs. organizational) and for multiple EBPs (e.g., can practice facilitation simultaneously improve adoption of EBPs in hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and health behaviors?). In addition to adapting strategies for historically marginalized populations, incorporating novel approaches like user-centered design72 may further improve the fit between EBPs, strategies, and contexts.. While our focus was on U.S. studies, much can also be learned from the rich history of global implementation efforts. True impact on CVD disparities will likely require multi-level, stakeholder-priority-driven EBPs and implementation strategies in policy and community settings. De-implementation8 of interventions that exacerbate disparities may also be needed.

For step 4, we found few examples of rigorous implementation science evaluations in policy settings. Future study designs should extend beyond testing one strategy at a time and compare the effectiveness of theory-informed implementation strategies (like audit and feedback vs. practice facilitation) on the equitable implementation of multiple EBPs, perhaps through adaptive designs that allow researchers and policymakers to isolate effects of individual strategies.6 Furthermore, study designs and mixed methods should be equity-relevant, rigorous, and specifically focused on targeting a historically marginalized population or collecting data to assess differential effects of the study EBP and implementation strategy.31 While some implementation science evaluation criteria are emerging,26, 73 future work should refine and validate the CV health equity-specific checklist proposed in this statement.

Finally, achieving CV health equity will require understanding the limitations of implementation science. There are times when theoretical frameworks may be too structured and resource intensive, inadequately focused on equity, not validated, or ill-fitted to address needs of historically marginalized populations. Further, it may not always be possible to distinguish implementation strategies from EBPs, particularly in health services/quality improvement research. Implementation science is a relatively young, rapidly changing field, and lack of consistent implementation science language in the literature affected our ability to conduct a systematic review, a key limitation of this statement, which is not intended to answer a specific research question(s) or to provide evidence to inform clinical decision-making. Thinking about implementation too early may also inadvertently stymie innovation efforts at early efficacy stages. Nonetheless, implementation science provides a process for better distinguishing between studies aimed at examining clinical and implementation outcomes. Most importantly, implementation science is a useful lens for improving the reach and sustainability of decades of disparities research to achieve CV health equity.

Conclusion

Funders, researchers, and policymakers alike have called for leveraging implementation science to promote health equity.21, 23, 25 However, little guidance exists around identifying EBPs ready for implementation and how best to leverage implementation science to address CVD inequities. Applying several equity considerations to four key implementation science steps (Figure 1, Table 2), we provide a checklist for employing rigorous implementation science methods to advance CV health equity. We highlight key gaps in the literature and identify areas for future equity-informed implementation science research, with the aim of spurring rigorous implementation science research to address evidence-to-practice gaps to promote CV health equity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We like to acknowledge Ethan C. Lennox for copy-editing, Darlene Straussman for organizing meetings and John Usseglio for conducting the systematic review. We would also like to acknowledge the Research in Implementation Science for Equity (RISE) program.

ABBREVIATIONS

Commonly used in Implementation Science or CV Equity

- BP

Blood Pressure

- CHWs

Community Health Workers

- CVD

Cardiovascular Disease

- EBPs

Evidence-based Practices

- RE-AIM

Reach, Effectiveness- Adoption, Implementation Maintenance

- SDoH

Social and Structural Determinants of Health

References

- 1.National collaborating centre for determinants of health. (2014). Glossary of essential health equity terms. Antigonish, ns: National collaborating centre for determinants of health, st. Francis xavier university.;2021 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mensah GA, Cooper RS, Siega-Riz AM, Cooper LA, Smith JD, Brown CH, et al. Reducing cardiovascular disparities through community-engaged implementation research: A national heart, lung, and blood institute workshop report. Circulation research. 2018;122:213–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabin B, Brownson R. Developing the terminology for dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Graham CA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2012:23–52. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R, Smith P, Bellamy N. Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions. Prev Sci. 2002;3:241–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen JD, Linnan LA, Emmons KM. Fidelity and its relationship to implementation effectiveness, adaptation, and dissemination In: Brownson RC, Graham CA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and implementation research in health. New York, NY Oxford University Press, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown CH, Ten Have TR, Jo B, Dagne G, Wyman PA, Muthén B, et al. Adaptive designs for randomized trials in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:1–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman MS, Sanders Thompson VL. The science of stakeholder engagement in research: Classification, implementation, and evaluation. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7:486–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers E Diffusion of innovations. New York, NY: The Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National partnership for action. National stakeholder strategy for achieving health equity. Us department of health & human services, office of minority health. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 11.World health organization. Health equity. Revised 2017. Available at: Https://www.Who.Int/topics/health_equity/en/. Accessed july 23, 2021.

- 12.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50:217–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science. 2006;1:1 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (eric) project. Implementation Science. 2015;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of medicine roundtable on evidence-based m. The national academies collection: Reports funded by national institutes of health. In: Olsen l, aisner d, mcginnis jm, eds. The learning healthcare system: Workshop summary. Washington (dc): National academies press (us) copyright © 2007, national academy of sciences.; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:351–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, Girling AJ, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: Rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2015;350:h391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, et al. Call to action: Structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: A presidential advisory from the american heart association. Circulation. 2020;142:e454–e468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: Conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res. 1998;13:87–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinman M, Woodward EN, Curran GM, Hausmann LRM. Harnessing implementation science to increase the impact of health equity research. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 9 Suppl 2:S16–S23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper la, purnell ts, engelgau m, weeks k, marsteller ja. Using implementation science to move from knowledge of disparities to achievement of equity. In: The science of health disparities research.2021:289–308.:289–308. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterling MR, Echeverria SE, Commodore-Mensah Y, Breland JY, Nunez-Smith M. Health equity and implementation science in heart, lung, blood, and sleep-related research: Emerging themes from the 2018 saunders-watkins leadership workshop. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e005586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curran GM. Implementation science made too simple: A teaching tool. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ. Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shelton RC, Adsul P, Oh A, Moise N, Griffith DM. Application of an antiracism lens in the field of implementation science (is): Recommendations for reframing implementation research with a focus on justice and racial equity. Implementation Research and Practice. 2021;2:26334895211049482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzucca S, Arredondo EM, Hoelscher DM, Haire-Joshu D, Tabak RG, Kumanyika SK, et al. Expanding implementation research to prevent chronic diseases in community settings. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:135–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodward EN, Matthieu MM, Uchendu US, Rogal S, Kirchner JE. The health equity implementation framework: Proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis c virus treatment. Implement Sci. 2019;14:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eslava-Schmalbach J, Garzon-Orjuela N, Elias V, Reveiz L, Tran NT, Langlois EV. Conceptual framework of equity-focused implementation research for health programs (equir). International Journal for Equity in Health. 2019;18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brownson RC, Kumanyika SK, Kreuter MW, Haire-Joshu D. Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implement Sci. 2021;16:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]