Abstract

Background

Traditional medicinal plants are central to healthcare, nutrition, and cultural practices in rural Ethiopia, yet ethnobotanical knowledge is underdocumented and increasingly threatened. This study aimed to document medicinal plant diversity, usage, preference, and conservation status in Menz Keya Gebreal District, North Shewa Zone, to inform sustainable management and pharmacological research.

Methods

Data were collected from 80 informants using semi-structured interviews, guided field walks, focus group discussions, and field observations. Quantitative ethnobotanical analyses included Informant Consensus Factor (ICF), Fidelity Level (FL), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), Relative Popularity Level (RPL), Rank Order Priority (ROP), Cultural Value Index (CVI), paired and preference ranking, and direct matrix ranking. Similarity with other Ethiopian districts was assessed using Jaccard’s and Rahman’s indices. Statistical analyses, including t-tests, ANOVA, correlation, and regression, were conducted using R to evaluate variation in knowledge across demographic groups.

Results

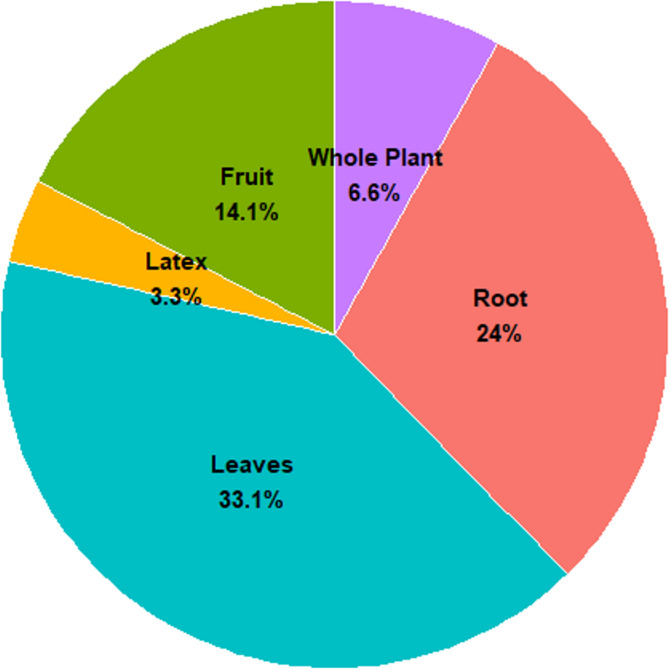

A total of 121 medicinal plant species from 61 families were documented, with Asteraceae, Fabaceae, and Euphorbiaceae being the most represented. Leaves were the most frequently used plant part, and oral administration was the predominant route of remedy preparation. High ICF values were observed for skin (0.87) and digestive disorders (0.82). Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce) J.F.Gmel., Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. ex Benth., and Echinops kebericho Mesfin exhibited high FL, RFC, and ROP values, while Clutia abyssinica Jaub. & Spach and Euphorbia abyssinica J.F.Gmel.were prioritized for hepatitis treatment. Major threats to medicinal plants included agricultural expansion, overharvesting, and firewood collection. Ethnobotanical knowledge varied significantly by informant groups (P < 0.05). RSI and JSI revealed both shared and unique knowledge patterns across regions. Knowledge transfer occurred primarily within families, while sacred groves, home gardens, and cultural practices contributed to in situ conservation.

Conclusion

Menz Keya Gebreal District harbors rich medicinal plant diversity and traditional knowledge, but anthropogenic pressures threaten their persistence. Integrating community-based conservation, sustainable harvesting, pharmacological validation, and youth-focused knowledge preservation is essential to safeguard this ethnobotanical heritage.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12906-025-05158-5.

Keywords: Conservation, Ethiopia, Ethnobotany, Medicinal plants, Menz keya gebreal, Traditional knowledge

Background

Traditional medicinal knowledge remains central to primary healthcare in many parts of the world, particularly in rural and underserved areas where biomedical infrastructure is limited [1–3]. Ethnobotany the study of human–plant relationships within cultural and ecological contexts offers critical insights into healing practices, biodiversity use, and cultural heritage [4–6]. Recognizing its importance, the World Health Organization has emphasized the integration of traditional medicine into national health systems [7].

Ethiopia, home to over 6,000 higher plant species across diverse agro-ecological zones, is one of Africa’s richest centers of ethnomedicinal practice [8, 9]. In remote districts such as Menz Keya Gebreal (North Shewa Zone), traditional medicine remains a primary healthcare strategy, relying on species such as Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. ex Benth., Ruta chalepensis L., Croton macrostachyus Hochst. ex Delile, and Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce) J.F. Gmel. However, this orally transmitted knowledge is increasingly threatened by deforestation, agricultural expansion, climate variability, sociocultural change, and weakening intergenerational transfer [10–14]. As in other biodiversity-rich countries, the erosion of ethnobotanical knowledge coincides with global shifts toward integrating traditional medicine into sustainable healthcare frameworks [15–18]. Growing reliance on biomedical care and formal education further disrupts oral traditions, diminishing interest among younger generations [19, 20].

While countries such as India, Brazil, and China have established policies integrating traditional medicine and promoting key species like Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal and Ocimum sanctum L [5, 21]., Ethiopia’s institutional frameworks remain underdeveloped [22, 23]. Local initiatives, including community medicinal gardens and sustainable harvesting projects, exist [24, 25], but coordinated policy development and research investment are urgently needed to ensure long-term sustainability. Documenting indigenous knowledge held by healers and elder informants supports intergenerational transmission, strengthens community resilience, and contributes to holistic public health strategies [26–28].

Despite Ethiopia’s rich cultural and ecological diversity, systematic ethnobotanical studies remain fragmented, and knowledge from many districts including Menz Keya Gebreal remains undocumented. This gap threatens not only cultural heritage but also biodiversity conservation and the potential for novel pharmacological discoveries.

Accordingly, this study aims to: (i) document medicinal plant species and their therapeutic applications in Menz Keya Gebreal; (ii) analyze variations in knowledge across informant groups using the Botanical Ethnoknowledge Index (BEI); (iii) identify common ailments and their remedies; (iv) compare findings with prior Ethiopian and regional studies; and (v) highlight culturally significant species through quantitative ethnobotanical measures. We hypothesize that demographic factors particularly age, gender, and education influence ethnobotanical knowledge, with older, male, and less formally educated individuals retaining deeper knowledge than their younger or more educated counterparts. We further anticipate signs of knowledge decline among youth due to modernization and lack of documentation, while conservation awareness and sustainable practices are more prevalent among elders and traditional healers.

Addressing these objectives is significant for supporting intergenerational knowledge transfer, informing culturally appropriate health strategies, and promoting biodiversity conservation. Situating this work within regional and global ethnobotanical initiatives also strengthens Ethiopia’s role in safeguarding traditional knowledge while aligning with international efforts to conserve medicinal plant resources and integrate ethnomedicine into sustainable healthcare systems.

Materials and methods

Description of the study area

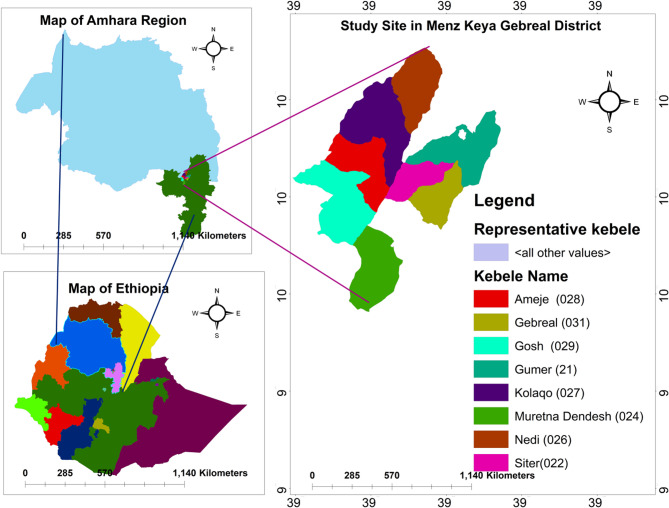

The study was conducted in Menz Keya Gebreal District, one of five administrative districts in the Menz region of Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia (Fig. 1). The district, part of North Shewa Zone, was reorganized in 1991 from the former Gera Midirna Keya Gebreal District. It covers about 595 km² and consists of 13 kebeles (12 rural, 1 urban), with Zemero as its administrative center. Geographically, it lies between 10°00′–10°21′N and 39°12′–39°30′E, at altitudes of 1,400–2,960 m a.s.l. The terrain is predominantly mountainous, with considerable climatic variability. It borders Jamma (South Wollo Zone) to the north, Merhabiete to the west, Menz Gera Midir to the east, and Menz Lalo Midir and Moretna Jiru to the south. The Jamma and Qechene Rivers, part of the Blue Nile watershed, form natural boundaries [29].

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area (Generated by ArcGis 10.4.1)

The district is culturally conservative and predominantly Ethiopian Orthodox Christian. According to the 2007 CSA census, its population was 46,219, of which 5.7% were urban residents. Agriculture is the main livelihood, practiced through mixed farming of crops and livestock. Agroecological zones range from lowland (kolla) to highland (dega), supporting crops such as teff (Eragrostis tef (Zuccagni) Trotter), barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), wheat (Triticum spp.), chickpeas (Cicer arietinum), and Niger seed (Guizotia abyssinica). Productivity is affected by seasonal variability, especially erratic Belg rains and frost at higher altitudes. Cash crops including coffee (Coffea Arabica L.), chat (Catha edulis Forsk), pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.), and Rhamnus prinoides (“Gesho”) are cultivated near irrigation sources, while cotton, fruits, and vegetables are grown in smaller areas, mostly for market sale. Livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys, horses, and mules are central to the local economy, with sheep valued for meat and hides. Due to fuelwood scarcity, dried cow dung (kubet) is commonly used as household fuel [29].

Traditional medicine remains important, with healers (Ye-bahel medihanit awaki) treating conditions such as fractures and dislocations. Handicrafts including weaving, pottery, basketry, and metalwork supplement household income and are traded in local markets held on Saturdays, Mondays, and Tuesdays.

Infrastructure, however, is limited. Roads are underdeveloped though improving through regional projects. Healthcare services remain inadequate, with only four health centers serving the 13 kebeles. Common health problems include dyspepsia, pneumonia, helminthiasis, typhoid, scabies, injuries, hypertension, dental issues, and amebiasis, particularly in rural areas where modern healthcare is costly and inaccessible. A recently opened traditional medicine shop provides some additional support.

Social cohesion in the district is reinforced by strong religious institutions, customary governance, and local dialects. Dispute resolution is commonly facilitated by the Yegobez Aleqa (council of elders), reflecting the enduring significance of traditional institutions in community life.

Climate of the study area

Menz Keya Gebreal encompasses three agro-climatic zones shaped by elevation and temperature: highland (Dega), which dominates the district, followed by mid-altitude (Weyna Dega) and lowland (Kolla) areas. Much of the district lies within the cool, wind-exposed Shewa highlands [29]. Its topography is characterized by elevated plateaus, basalt cliffs, and deep river gorges, creating a rugged landscape that limits mobility and accessibility.

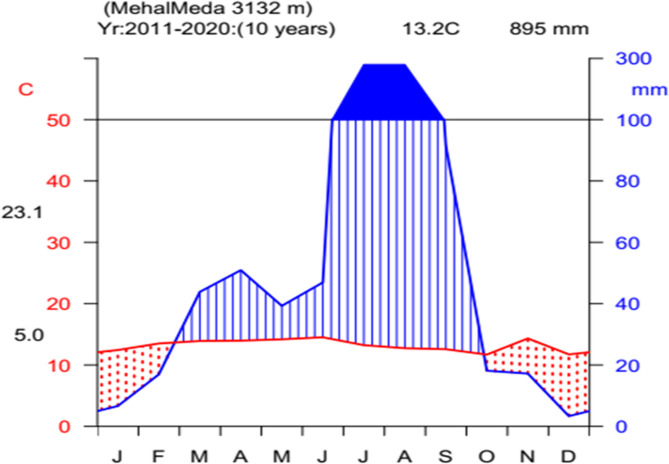

Rainfall follows a bimodal pattern. The main rainy season (Kiremt) extends from June to September, with peak precipitation in July and August. The short rainy season (Belg), occurring from March to April, is less reliable, particularly in mid- and low-altitude zones where onset is often delayed and rainfall insufficient. Meteorological data from Kombucha station (2011–2020) show a mean annual rainfall of 894.7 mm. August is the wettest month, averaging 280.2 mm, while December is the driest, with only 33.5 mm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Climadiagram of the study area. (source: NMSA, 2020)

Temperature patterns reflect the district’s high elevation. The mean monthly maximum is 21.4 °C, typically in June, while the lowest mean minimum of 2.5 °C occurs in December (Fig. 2). These climatic conditions directly influence agricultural productivity and water availability in the district.

Reconnaissance survey, study site and informant selection

This ethnobotanical study was conducted in Menz Keya Gebreal District, North Shewa Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia, to document and analyze traditional knowledge of medicinal plants. Both qualitative and quantitative methods were applied to capture data on plant use, knowledge variation among informants, cultural significance, and conservation concerns.

A reconnaissance survey was undertaken from September 10–17, 2021, to familiarize the research team with the district’s biophysical and socio-cultural context, identify suitable study sites, and establishes rapport with local stakeholders. During this phase, meetings were held with community elders, traditional healers, and local leaders to locate areas of intensive medicinal plant use and to assess biodiversity hotspots and resource accessibility. Data collection followed between October 8, 2021, and March 7, 2022.

Study sites were purposively selected, focusing on kebeles with rich vegetation and strong traditions of medicinal plant use. Prior studies, health professionals, elders, and traditional practitioners informed this process. Eight kebeles Amija, Gebreal, Gumer, Kolaqo, Mureyna Dendesh, Nedi, Siter, and Gosh were chosen, representing 61.5% of the district’s 13 kebeles (Table 1). These predominantly rural sites maintain strong oral traditions of ethnobotanical knowledge.

Table 1.

Sampled study sites: altitude, coordinates, agro-ecology, number of households, and sociodemographic characteristics of informants

| Name of study sites | Altitude | GPS Coordinates | Gender | Ethnicity | Age categories | Language | Occupation | NH | AE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude (N, S) | Longitude (E, W) | M | F | 20–30 | 31–50 | 51–85 | |||||||

| Amija | 2684 m | 10°12’10"N | 39°19’19"E | 7 | 3 | Am | 2 | 4 | 4 | Amc | Far, Mer, HW, Stu, Tch | 684 | Highland |

| Gebreal | 2712 m | 10°09’00"N | 39°24’22"E | 6 | 4 | Am | 2 | 3 | 5 | Amc | Far, Mer, HW, Stu, Tch | 763 | Highland |

| Gumer | 2770 m | 10°12’41"N | 39°25’46"E | 7 | 3 | Am | 2 | 4 | 4 | Amc | Far, Mer, HW, Stu, Tch | 698 | Highland |

| Kolaqo | 2095 m | 10°16’46"N | 39°21’02"E | 6 | 4 | Am | 2 | 3 | 5 | Amc | Far, Mer, HW, Stu, Tch | 682 | Highland |

| Mureyna dendesh | 2640 m | 10°04’40"N | 39°21’00"E | 8 | 2 | Am | 1 | 4 | 5 | Amc | Far, Mer, HW, Stu, Tch | 656 | Highland |

| Nedi | 2255 m | 10°17’11"N | 39°21’58"E | 6 | 4 | Am | 2 | 2 | 6 | Amc | Far, Mer, HW, Stu, Tch | 545 | Highland |

| Siter | 1915 m | 10°10’23"N | 39°21’55"E | 7 | 3 | Am | 2 | 3 | 5 | Amc | Far, Mer, HW, Stu, Tch | 453 | Mid-highland |

| Gosh | 1748 m | 10°07’15"N | 39°19’50"E | 6 | 4 | Am | 2 | 2 | 6 | Amc | Far, Mer, HW, Stu, Tch | 645 | Mid-highland |

| Total | 53 | 27 | 15 | 25 | 40 | 5126 | |||||||

Key: Am Amhara, Amc Amharic, M Male, F Female, AE Agro-ecology, NH Number of households, Far Farmer, Mer Merchant, HW House wife, Stu Student, Tch Teacher

Informant selection combined purposive and systematic random sampling. In total, 80 participants (53 males, 27 females) aged 20–85 were included, with 10 informants drawn from each kebele. Of these, 60 general informants were randomly selected, while 20 key informants primarily traditional healers were purposively chosen based on community recommendations. Informants were further grouped into three age categories: young adults (20–30 years), middle-aged (31–50 years), and elderly (51–85 years), to explore generational differences in knowledge transmission. Selection emphasized participants’ willingness, experience with medicinal plants, and recognition within the community. Criteria were refined in collaboration with local leaders to ensure the inclusion of individuals with authentic and valuable knowledge.

Ethnobotanical data collection

Ethnobotanical data were collected through semi-structured interviews, guided field walks, direct observation, and focus group discussions (FGDs) to document traditional knowledge on medicinal plants in Menz Keya Gebreal District. These methods provided complementary perspectives on plant identification, preparation, application, and conservation.

Semi-structured interviews

Interviews formed the primary data source and were conducted using a pre-tested checklist of 31 open-ended questions. Initially prepared in English and translated into Amharic, the checklist covered demographic details (age, sex, address) and ethnobotanical information, including vernacular plant names, treated ailments (human, animal, or both), plant parts used, sources of collection (wild or cultivated), abundance, preparation methods, duration of treatment, routes of administration, conservation practices, and seasonal availability. This approach allowed flexible probing of each informant’s experiences [30, 31]. Plant collection was authorized by landowners and the district administrative and agricultural offices, ensuring compliance with ethical guidelines.

Guided field walks and observations

Field visits with local guides and key informants enabled in situ observation of medicinal plants. Transect walks were used to verify species cited during interviews and to document growth habits, ecological distribution, abundance, harvested parts, preparation methods, therapeutic applications, and indigenous conservation measures [32, 33].

Focus group discussions

FGDs were organized in each study kebele with 5–8 participants, including traditional healers, elders, religious leaders, and local administrators. Discussions addressed preparation techniques, dosage forms, additive ingredients, side effects, administration routes, and systems of knowledge transmission. A structured checklist, translated into Amharic, guided the sessions. These group interactions enriched the dataset by validating individual reports, capturing community perspectives, and highlighting consensus or divergence in knowledge [34].

Voucher specimen collection, identification, and herbarium Preparation

Medicinal plant specimens were collected from both wild and cultivated habitats with the assistance of local herbalists and agricultural experts. Two specimens per species were taken, each labeled with a collection number and collector’s name. Specimens were pressed between blotting papers, oriented to capture all morphological features, and air-dried under sunlight, with regular inspections to prevent insect damage [30].

Preliminary identification was carried out at the Mini Herbarium, Debre Berhan University, and further taxonomic verification was performed using the Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea and standard taxonomic keys. Final confirmation was conducted at the National Herbarium (ETH), Addis Ababa University, through comparison with authenticated herbarium specimens and published descriptions [31, 35]. Additional references included field guides on Ethiopian trees and shrubs as well as multiple online taxonomic databases, such as Plants of the World Online (Kew), PlantNet, Flora Finder, USDA Plants Database, African Plant Database, the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, and JSTOR Global Plants for authoritative nomenclature verification [36].

The formal identification of plant material was carried out by Dr. Abiyou Tilahun. Voucher specimens of all documented species were deposited in the Mini Herbarium, Department of Biology, Debre Berhan University, under the deposition number DBU002023, for future reference and taxonomic research.

Quantitative ethnobotanical analysis

To assess the reliability, depth, and community consensus surrounding traditional medicinal plant knowledge, a range of established quantitative ethnobotanical indices were applied. These included the Botanical Ethnoknowledge Index (BEI), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), Relative Popularity Level (RPL), Rank-Order Priority (ROP), Fidelity Level (FL), Cultural Value Index, and Informant Consensus Factor (ICF). Additionally, participatory ranking techniques such as preference ranking, direct matrix ranking, and paired comparison were employed to capture local perceptions and prioritization of plant species. Similarity analyses were also conducted using Rahman’s Similarity Index (RSI) and the Jaccard Similarity Index to compare ethnobotanical patterns within and across study sites.

Botanical ethnoknowledge index (BEI)

The Botanical Ethnoknowledge Index (BEI) is designed to quantify the complex interplay of factors influencing ethnobotanical knowledge within a specific group and enables comparative analysis across groups sharing similar ecological and floristic settings [37]. The index incorporates several key variables: the total number of plant species reported by all members of a group, the mean number of species reported per participant, the mean number of citations per species, the number of participants in the group, and the total number of species reported across all groups in the study. BEI values range from just above 0 to a maximum of 2. A higher BEI indicates a greater depth of ethnobotanical knowledge within the group. Although values between 1 and 2 are theoretically possible, they are relatively rare and typically reflect distinct or highly specialized knowledge compared to other groups.

The BEI is calculated using the following formula:

|

Where, BEI: Botanical Ethnoknowledge Index. ms: mean number of species reported per participant in a particular group. Sg: total number of species reported by all participants in a particular group. mc: mean number of citations per species in a particular group. N: number of participants in the particular group. St: total number of species reported by all compared groups in the study. The above-presented index is designed to compare groups with similar sample sizes [37]. However, in order to overcome this limitation when comparing groups with diferent sample sizes, the index value can be relatively corrected by multiplying it with a coefcient as follows:

|

Where, F: correcting factor. N mean: mean number of participants among all compared groups. √N min: square root of the number of participants in the smallest group.

Calculation of the relative frequency of citation (RFC)

The relative frequency of citation (RFC) was calculated for each species to highlight its local importance. RFC was given by the following formula [38]:

|

Where; FC = the number of informants citing the use of the species and N = the total number of respondents participating in the survey.

Relative popularity level (RPL)

The Relative Popularity Level (RPL) is a metric used in ethnobotanical studies to evaluate how commonly a medicinal plant is known or used among informants. It helps distinguish between popular and less popular medicinal species [38].

|

Where: P = Number of informants who cited the plant species for medicinal use, Pmax= Number of informants who cited the most popular plant species (i.e., the highest frequency among all species). The Relative Popularity Level (RPL) value ranges between 0 and 1 and provides a comparative measure of a plant species cultural popularity among informants. An RPL value of 1 indicates the most popular plant, cited by the highest number of informants. In contrast, values less than 1 represent less popular species, cited by fewer individuals. This index is useful for distinguishing widely recognized medicinal plants from those with more limited traditional use.

Fidelity level (FL)

The Fidelity Level (FL) quantifies the percentage of informants who consistently report the use of a specific plant for treating a particular ailment. It reflects the degree of specificity and reliability associated with the therapeutic application of a given species. A higher FL value indicates greater agreement among informants regarding a plant’s use, suggesting its cultural and medicinal prominence within the community [32]. The FL was calculated using the formula:

|

Where: FL = Fidelity Level (expressed as a percentage), Ip = Number of informants who independently cited a species for a specific ailment, Iu = Total number of informants who mentioned the species for any use.

This index enabled the identification of species with high therapeutic specificity and potential pharmacological interest.

Calculation of the rank-order priority (ROP)

The Rank-Order Priority (ROP) is an ethnobotanical index that combines both the Relative Popularity Level (RPL) and Fidelity Level (FL) to help prioritize medicinal plants for further pharmacological investigation [38].

|

Cultural value index (CVI)

The Cultural Value Index (CVI) is an ethnobotanical measure used to assess the cultural significance of a plant species based on its use diversity, frequency of citation, and the number of use categories [39]. The cultural value index was calculated using the formula:

|

Where: FC = Number of informants citing the species, Ni = Total number of informants, Nu = Number of use reports for the species, Nc = Total number of use categories.

Informant consensus factor (ICF)

The Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) was used to evaluate the level of agreement among informants regarding the use of medicinal plants for specific categories of ailments. A high ICF value implies that a few species are widely used to treat a particular condition, which may indicate both the cultural salience and potential effectiveness of those plants [33, 40]. In contrast, a low ICF suggests a lack of consensus and potentially random or individualized plant usage. The ICF was computed using the following formula:

|

Where: Nur = Number of use-reports for a particular illness category, Nt = Number of species used for that illness category. Values range from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 denoting a higher consensus among informants.

Preference ranking

Preference ranking was utilized to determine the relative importance and perceived efficacy of selected medicinal plant species in treating specific ailments. Following the approach of [33], ten key informants were asked to rank five medicinal plants based on their effectiveness against intestinal parasites. Rankings ranged from 1 (least effective) to 5 (most effective). The cumulative scores were then used to determine the overall ranking of each species, highlighting those considered most efficacious by the local community [34]. This method provided crucial insights into community priorities and treatment preferences.

Direct matrix ranking

To assess the multipurpose utility of medicinal plant species beyond their therapeutic applications, direct matrix ranking was conducted. Five frequently cited tree species were evaluated by ten key informants across seven use categories: medicinal value, construction material, firewood, charcoal production, furniture, agricultural tools, and food. Informants assigned scores from 1 (least important) to 5 (most important) for each use category. The cumulative scores helped determine which species were most valued for their multifunctional roles, guiding conservation strategies accordingly [33, 34]. This approach also highlighted the broader socio-economic contributions of medicinal plants within rural livelihoods.

Paired comparison

To explore the relative preference of informants regarding specific medicinal plant species or uses, paired comparison analysis was employed. All possible pairs of selected items were generated using the formula:

|

Where n is the number of items being compared and each informant was asked to select the more preferred item from each pair. The number of times each item was chosen was tallied to determine its overall ranking [34]. This method facilitated a nuanced understanding of community values and priorities concerning medicinal plant use. Together, these quantitative techniques provided robust insights into the local ethnopharmacological landscape, guiding both research prioritization and sustainable resource management.

Jaccard similarity index

To evaluate the degree of overlap in medicinal plant knowledge between different groups or regions, the Jaccard Similarity Index (JSI) was applied. The JSI quantifies the proportion of shared species between two datasets and is especially useful in comparing knowledge among traditional healers, elders, and general community members, or between distinct geographic regions [2, 41]. The index was computed using the following formula:

|

Where: JSI = Jaccard Similarity Index (as a percentage), a = Number of species recorded in the comparison area, b = Number of species recorded in the current study area, c = Number of species common to both areas. The JSI ranges from 0 to 100%, where 0% indicates no similarity and 100% indicates complete similarity. This approach provides insights into how traditional medicinal knowledge is shared or differs across communities and environments.

Rahman’s similarity index (RSI)

Rahman’s Similarity Index (RSI) was employed to assess the cultural congruence of medicinal plant usage across different study areas. Unlike JSI, RSI emphasizes not just shared species but also the similarity in their therapeutic applications, offering a more nuanced view of ethnobotanical overlap [41]. The RSI was calculated as follows:

|

Where: Na = Number of unique species in area A (previous study area), Nb = Number of unique species in area B (current study area), Nc = Number of species common to both areas, Nd = Number of species used for the same ailments in both areas. This index ranges from 0% to 100%, with higher values indicating greater cultural similarity in medicinal plant knowledge and usage between study areas.

Data analysis

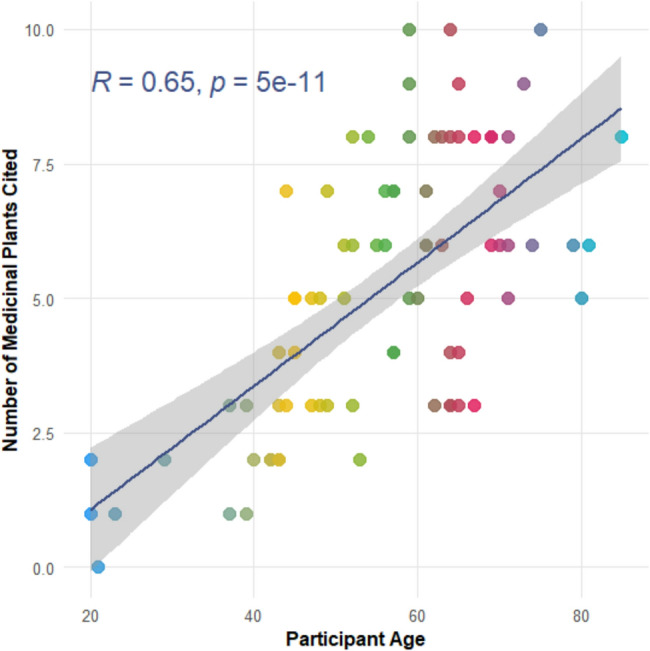

A mixed-methods approach integrating both qualitative and quantitative analyses was employed to interpret the ethnobotanical data. Qualitative information obtained through semi-structured interviews and field observations was analyzed thematically to identify patterns in plant use and cultural perceptions. Quantitative data were processed using descriptive statistics (mean,) and ethnobotanical indices, notably the Botanical Ethnoknowledge Index (BEI). Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.3). The Shapiro–Wilk test assessed data normality, while analysis of variance (ANOVA) evaluated differences among age groups. Pearson correlation and linear regression were used to explore the relationship between age and the number of medicinal plants reported [20, 21]. This integrated analytical framework facilitated a comprehensive understanding of traditional plant knowledge, its demographic drivers, and regional patterns.

Ethical considerations

This research was conducted in accordance with established ethical guidelines for ethnobotanical studies. Prior informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study’s objectives, methods, and voluntary nature. Confidentiality was maintained throughout, and personal identifiers were omitted from the dataset. Ethical approval was granted by the appropriate local authorities and community leaders. The research team ensured cultural sensitivity, particularly when documenting knowledge about sacred or ritually significant plants. The study adhered to international ethical frameworks, including the Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE), to protect indigenous knowledge and promote its sustainable and respectful use.

Results and discussion

Sociodemographic attributes of informants

A total of 80 informants participated in this study, comprising 53 males (66.2%) and 27 females (33.8%). General community members accounted for 75% (n = 60), while 25% (n = 20) were key informants recognized for their specialized ethnomedicinal knowledge and long-standing experience. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 85 years, with half (50%, n = 40) belonging to the 51–85 age group, followed by 31.3% (n = 25) in the 31–50 group. Educationally, 73.7% (n = 59) were illiterate and 26.3% (n = 21) had some formal education (Table 1).

These sociodemographic patterns mirror findings from other Ethiopian ethnobotanical studies, where knowledge is predominantly concentrated among older, often illiterate men who serve as primary custodians through oral transmission and experiential learning [2, 20, 26, 42]. Similar trends have been observed in Kenya and Nigeria, where elder men often retain the most comprehensive ethnomedicinal knowledge due to their roles as community leaders and healers [39, 43].

The lower representation of women reflects cultural norms that limit their participation in formal knowledge sharing, despite their central role in home-based healthcare and informal healing practices [16, 17, 22]. Comparable gender dynamics are reported in South Asia and Latin America, where women hold significant medicinal plant knowledge that is less visible in formal ethnobotanical research [44, 45].

The predominance of elderly informants with limited formal education highlights the oral, undocumented nature of indigenous knowledge, typically transmitted through storytelling, apprenticeship, and family networks [2, 10]. This reliance on oral transmission makes the knowledge vulnerable to erosion amid sociocultural change. Consequently, systematic documentation is critical. Ethiopian studies recommend incorporating visual and oral methods into ethnomedicine education and conservation initiatives to overcome literacy barriers [20, 21, 46], while international research emphasizes gender-inclusive approaches and youth engagement to strengthen intergenerational transfer and sustain traditional practices [12, 13].

Cultural naming of medicinal plants in the study area

In Menz Keya Gebreal District, the naming of medicinal plants reflects deep cultural connections, often based on therapeutic properties, morphological traits, or social significance. All documented species had local names derived from indigenous languages, frequently describing a plant’s function or distinctive characteristics such as stem color, leaf shape, aroma, or taste. For instance, Becium polystachya is called Nech Anfar (“white stem”) for its pale stalk, Rosmarinus officinalis is Siga Metibesha, referencing its culinary use as a meat seasoning, and Agave sisalana is Yeset Qest, linked to Ensirt, a traditional cotton-processing tool, highlighting its cultural importance. Other examples include Rumex nepalensis (Yewusha Milas, “dog’s tongue”) for its leaf shape and Ruta chalepensis (Tena Adam, “Adam’s health”) for its general healing properties.

These findings align with research from Ethiopian regions such as Kaffa, Sheka, and Gamo-Gofa, where plant names similarly encode functional, morphological, and symbolic information, reflecting shared ethno-linguistic patterns and cultural heritage [20, 36, 47, 48]. Comparable practices are reported across Africa, China, India, and Latin America, where vernacular names serve as repositories of indigenous knowledge and cultural identity [1, 3, 43, 44]. Locally embedded names function not only as taxonomic labels but also as mnemonic devices, teaching tools, and central elements of oral knowledge transmission in largely unwritten ethnomedicinal traditions [47–49]. These names often endure beyond precise botanical identification, helping preserve ethnobotanical knowledge despite environmental and cultural changes.

However, assigning identical or similar names to different species with overlapping uses can lead to confusion or misapplication of remedies, an issue documented in Ethiopian districts such as Metema and Quara, as well as in traditional communities worldwide [2, 3, 6, 50].

The cultural naming system has important implications. First, vernacular names constitute vital intangible cultural heritage that should be safeguarded alongside medicinal plant conservation. Documenting both scientific and local names supports cultural continuity, educational initiatives, and cross-disciplinary research. Second, these names provide valuable leads for pharmacological studies by highlighting species with notable therapeutic roles based on traditional classification and use [2, 6, 23]. Finally, integrating cultural naming traditions into conservation policies, community healthcare planning, and sustainable development strategies can strengthen respect for indigenous knowledge systems, promote biodiversity preservation, and enhance the role of traditional medicine in rural livelihoods [24, 25, 34].

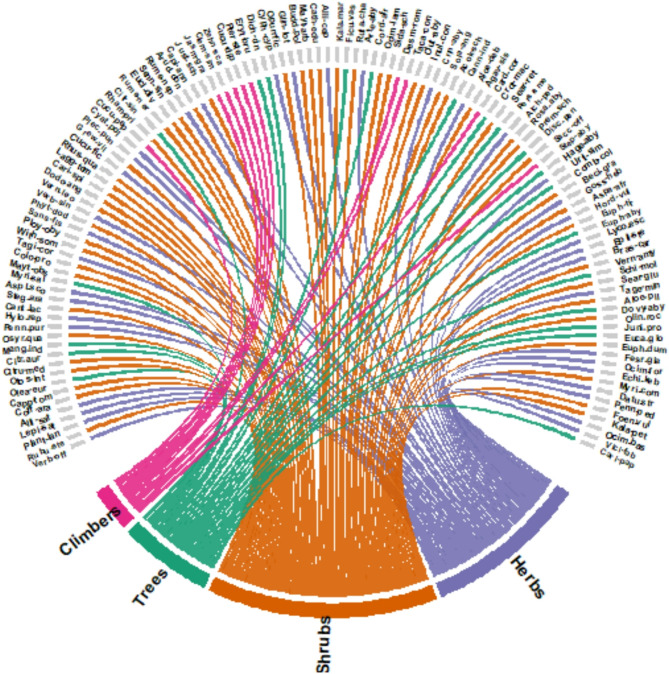

Diversity and distribution of medicinal plants in Menz Keya Gebreal District

A total of 121 medicinal plant species were documented in Menz Keya Gebreal District, representing 105 genera and 61 families. This richness reflects substantial phytomedicinal diversity and underscores the district’s exceptional ethnobotanical heritage. Compared with nearby Ethiopian districts reporting 73–85 species [8, 42, 51], the diversity in Menz Keya Gebreal is relatively high. Globally, documented medicinal plant diversity varies, ranging from 42 to 55 species in Tanzania and China [50, 52] to 122–168 species in other Ethiopian regions [3, 20, 22], reflecting differences in biodiversity, ecological conditions, and cultural ethnopharmacological practices.

Among plant families, Asteraceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Fabaceae were the most represented, each with seven species (5.8%), followed by Poaceae and Solanaceae with six species each (4.9%), and Anacardiaceae with five species (4.1%) (Table 2). The prominence of Asteraceae aligns with other Ethiopian and global ethnobotanical studies, where Asteraceae and Fabaceae are widely cited for their ecological adaptability and pharmacological importance [6, 21, 53, 54]. These families are commonly used for anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and gastrointestinal remedies, reflecting both local therapeutic priorities and sophisticated botanical knowledge.

Table 2.

Lists of medicinal plants used to treat different ailments in the study area

| Scientific Name | Short code | Family | Local Name | GF | HB | PU | CP | Disease treated | Mode of preparation | RA | VN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acokanthera schimperi (A.DC.) Schweinf. | Acok-sch | Apocynaceae | Mirez | Sh | W | Rt | D | Ayne wog for animal | The roots of Machid Seber, Shenbeko, Chifirg, Jibra Kestencha, Gumaro, Gizewa, Yemidir Embuay, Ameraro, Koshim, Mirez, Zert Embuay, and Kitkta are pounded and then burned. As the animal inhales the smoke, the harmful spirit is believed to be driven away. | Nasal | MY075 |

| Agave sisalana Perrine | Agav-sis | Asparagaceae | Sete Qacha | Sh | W | Lf | F | Kimajir | The leaf-like structures of Qacha are crushed, pounded, and soaked in a small amount of water. This liquid is then used to wash the infected area of the animal. | Dermal | MY078 |

| Alchemilla pedata Hochst. ex A.Rich. | Alch-ped | Rosaceae | yemidir koso | H | W | Wp | F | Ymirech | All parts are pounded, soaked for three days, and the resulting liquid is sprinkled onto the infected areas of the baby. | Dermal | MY083 |

| Allium cepa L. | Alli-cep | Amaryllidaceae | Key Shinkurt | H | HG/MK | Bu | F | Hypertension | The harvested fruit of Key Shinkurt is eaten together with fresh meat. | Oral | MY060 |

| Allium sativum L. | Alli-sat | Amaryllidaceae | Nech shinkurt | H | HG/MK | Bu | D | Eczema | The fruit is first crushed and dried. Once fully dried, it is ground into a fine powder. This powder is then mixed with butter and applied directly to the affected area. | Dermal | MY005 |

| Eye disease | The fruit of nech shinkurt, the leaf of dedho, and cotton fruit are pounded together. The mixture is then squeezed to extract the juice, which is carefully applied to the affected area of the eye. | Nasal | |||||||||

| Aloe debrana Christian | Aloe-deb | Asphodelaceae | Wonde ret | H | W | Lf | F | Athlete foot | Heat the inner moist parts and apply them to the infected areas. | Dermal | MY077 |

| Rt | F | Venom of scorpion | When a person is bitten by a scorpion, they eat the fruit as a remedy. | Oral | |||||||

| Aloe pulcherrima M.G.Gilbert & Sebsebe | Aloe-pil | Asphodelaceae | Sete Eret | Sh | W | Lf | F | Cancroid | The residue is mixed with suet and applied directly to the affected areas. | Dermal | MY105 |

| Rt | D | Evil eye | The roots of Etse Sabe’e, Gizewa, Kestenicha, Yemidir Embuay, Zert Embuay, Jibira, Ahiya Joro Agam, and Sete Ret are pounded together. The dried mixture is then ground into powder and used as incense smoke for a person believed to be afflicted by the evil eye spirit. | Dermal | |||||||

| Artemisia abyssinica Sch.Bip. ex Oliv. & Hiern | Arte-aby | Asteraceae | Chiqugn | H | W/MK | Wp | F/D | Evil sprit | The whole plants of Chiqugn, Tiena Adam, and Nech Shinkutr are crushed together, and the mixture is then inhaled. | Nasal | MY064 |

| Arundo donax L. | Arud-don | Poaceae | Shenbeko | Sh | HG/W | Rt | D | Evil eye | The moist roots of Shenbeko Kentefa, Wuyign, Gumaro, Dediho, and Gizewa are cut into very small pieces and dried. These are then mixed with the leaves of Keskeso and the whole parts of Chikugn. Finally, the dried mixture is powdered and smoked over a fire. | Nasal | MY044 |

| St | F/D | Bone fracture | The stem of Arundo donax is crushed into equal-sized pieces and then used to wrap the broken bone. This is kept in place for three days and the process is repeated until the bone heals and connects properly. | Dermal | |||||||

| Asparagus africanus Lam. | Aspa-afr | Asparagaceae | Kestenicha | Sh | W | Lf | F | Herpes | The leaves are finely chopped and pounded, then left to macerate for three days. Finally, the preparation is either applied as a cream to the affected area or consumed as a drink until recovery. | Dermal/Oral | MY094 |

| Rt | D | Evil eye | The roots of Etse Sabe’e, Gizewa, Kestenicha, Yemidir Embuay, Zert Embuay, Jibira, Ahiya Joro Agam, and Sete Ret are pounded together. After drying, the mixture is ground into a powder and smoked for a person believed to be afflicted by an evil eye spirit. | Nasal | |||||||

| Asplenium aethiopicum (Burm.f.) Bech. | Aspl-aet | Aspleniaceae | Goliba | H | W | Rt | F | Diarrhea | The leaves are pounded and crushed, then mixed with water and salt. This mixture is given to drink to those suffering from diarrhea. | Oral | MY018 |

| Becium grandiflorum (Lam.) Pic.Serm. | Beci-gra | Lamiaceae | Muatish | Sh | W | Rt | D | Abdominal pain | The root is powdered, mixed with water, and then filtered. Finally, a cup of the filtered liquid is taken every morning for five days. | Oral | MY092 |

| Brassica carinata A.Braun | Bras-car | Brassicaceae | Habesha Gomen | H | HG/MK | Lf | F | Fibril illness | It is cooked, and the water is then drunk to help recover from a febrile illness. | Oral | MY100 |

| Buddleja polystachya Fresen. | Budd-pol | Scrophulariaceae | Anfar | Sh | HG/W | Lf | F | Leech | The crushed leaves are mixed with water, and the resulting liquid is given to the infected animal to drink. | Oral | MY057 |

| Calotropis procera (Aiton) W.T.Aiton | Colo-pro | Apocynaceae | Kinbo | Sh | W | Lx | F | Kunchir | Apply cream to the infected areas. | Dermal | MY021 |

| Lx | F | Wound | The collected latex from Calotropis procera is applied as a cream on wounds until they heal. | Dermal | |||||||

| Canna indica L. | Cann-ind | Cannaceae | Koba | T | HG | Rt | F | Stomachache | The root is crushed and mixed with water, then drunk. | Oral | MY076 |

| Capparis tomentosa Lam. | Capp-tom | Capparaceae | Gumero | Sh | W | Rt | D | Evil eye | The fresh root is chopped into very small pieces and dried. Once fully dried, it is ground into a powder, which is then used for smoking. | Oral/Nasal | MY007 |

| Capsicum annuum L. | Capi-ann | Solanaceae | Berbere | H | HG/MK | Fr | F | Hepatitis | The fruits of Berbere and Nech Shinkurt, leaves of Tenbelel, and lemon juice are mixed and soaked together. After soaking, the mixture is filtered, and the person drinks one glass of the filtered medicine daily for three days. Finally, they consume one glass of honey. | Oral | MY045 |

| Cardiospermum corindum L. | Card-cor | Sapindaceae | Semeg | Cl | W | Lf | F | Leech | The leaves are pounded into a powder, which is then sniffed. | Nasal | MY079 |

| Lf | F | Abscess | The fresh leaves are chewed with milk, and then the resulting mixture is applied to the infected areas for six days. | Dermal | |||||||

| Rt | F/D | Infertility | The root of Semeg is pounded, then squeezed and filtered. The filtered liquid is consumed as a drink. | Oral | |||||||

| Wp | F | Abscess | The whole parts of Semeg, bark of Seghed, leaves and whole parts of Dediho, and leaves of Jib Mirkuz are mixed and massaged with milk, then applied to the body experiencing trembling and bitterness. The infected areas are then smeared with this mixture for six days. | Dermal | |||||||

| Carica papaya L. | Cari-pap | Caricaceae | Papaya | T | HG/MK | Fr | F | Gastric | The fruits of papaya, Qimmo, Woyira, the juice from Eret, and the leaves of Sunsel are mixed and ground together. The mixture is taken daily before meals. | Oral | MY121 |

| Lf | D | Malaria | The collected papaya leaves are crushed and dried, then boiled like tea. One cup is taken daily for seven days. | Oral | |||||||

| Carissa spinarum L. | Cari-spi | Apocynaceae | Agam | Sh | W | Lf | F | Snake bite | The leaves are finely cut into small pieces and pounded. The prepared mixture is then consumed until full recovery. | Oral | MY030 |

| Rt | D | Ayne Tila | The fresh root is cut into very small pieces and then dried. Once dried, it is ground into powder, which can be either consumed as a drink or smoked for treatment. | Oral | |||||||

| Rt | D | Evil eye | The roots of Etse Sabe’e, Gizewa, Kestenicha, Yemidir Embuay, Zert Embuay, Jibira, Ahiya Joro Agam, and Sete Ret are pounded together. After drying, the mixture is powdered and smoked to treat individuals believed to be affected by an evil eye spirit. | Nasal | |||||||

| Catha edulis (Vahl) Forssk. ex Endl. | Cath-edu | Celasteraceae | Kenbet(chat) | Sh | HG | Lf | F | Wound | The dried and powdered leaves of chat are combined with salt, lemon juice, and ladybird honey. First, the affected areas of the body are coated with white honey, then the prepared mixture is applied and gently massaged onto the infected parts until healing occurs. | Dermal |

MY/ 059 |

| Cenchrus purpureus (Schumach.) Morrone | Cenc-pur | Poaceae | Gosh mika | H | W | Rt | D | Kunchir | The root is pounded, dried, and ground into powder. Then, the powdered Goshmika is mixed with black teff dough and applied as a cream to the infected areas until recovery. | Dermal | MY014 |

| Citrus × aurantium L. | Citr-aur | Rutaceae | Lomi | T | W/HG | Lx | D | Kunchir | The fruit of yejib shinkurt, root of shimbrut, sindedo, goshmika, and the entire tenadam plant are pounded and dried, then ground into powder. Finally, this powder is applied by smearing it on the infected area. | Dermal | MY011 |

| Fr | Eye disease | The fruit of nech shinkurt, the leaf of dedho, and the fruit of cotton are pounded together, then squeezed to extract the juice. This pure liquid is finally applied to the infected parts of the eye. | Optical | ||||||||

| Citrus × sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Citr-sin | Rutaceae | Birtukan | T | W/HG | Fr | Gastric | Eat the fruit of birtucan directly before the daily meal. | Oral | MY039 | |

| Citrus medica L. | Citru-med | Rutaceae | Trngo | Sh | W/HG | Ba | F | Apetite | The bark of tiringo is eaten directly as a remedy. | Oral | MY010 |

| Fr | Liver | The fruit of the plant is eaten directly. | Oral | ||||||||

| Clematis simensis Fresen. | Clem-sim | Ranunculaceae | Azo Hareg | Cl | W | Rt | D | Wart | The dried root is ground into powder and mixed with barley batter. This mixture is then applied to all the infected areas. | Dermal | MY048 |

| Clutia abyssinica Jaub. & Spach | Clut-aby | Peraceae | Fiyele feji | Sh | W | Rt | D | Rabies | The roots of Ensilal, Fiyele Feji, Lutt, Woinagift, Gizewa, and Yemidir Enbuay are pounded together. After drying, the mixture is kneaded with teff flour and then formed into bread, which the sick person consumes. | Oral | MY071 |

| Lf | F | Jaundice | The collected leaves of Fiyelefeji are pounded and then squeezed with tella. The filtered liquid is then consumed as a drink. | Oral | |||||||

| Coffea arabica L. | Coff-ara | Rubiaceae | Buna | Sh | W/HG | Sd | D | Headache | Powdered coffee is steamed and then mixed with lemon before use. | Oral | MY006 |

| Sd | D | Diarrhea | To treat diarrhea, coffee (buna) is pounded and mixed with honey before consumption. | Oral | |||||||

| Combretum collinum Fresen. | Comb-col | Combretaceae | Abalo | T | W | Lf | D | Skin Rash | The leaves of Abalo and Kitikta are pounded and dried. Then, they are roasted and mashed before being kneaded into a paste, which is applied to the diseased areas of the body. | Dermal | MY091 |

| Cordia africana Lam. | Cord-afr | Boraginaceae | Wanza | T | HG | Fr | D | Wound | The fruits of Wanza and Injiry are pounded, dried, and ground into a powder. This powder is then sprinkled onto the infected areas. | Dermal | MY065 |

| Crinum abyssinicum Hochst. ex A.Rich. | Crin-aby | Amaryllidaceae | Yejib Shinkurt | H | W | Fr | D | Ayne Tila | The fresh root is cut into small pieces and dried. Once dry, the root is ground into powder, which is then smoked. | Nasal | MY073 |

| Croton macrostachyus Hochst. ex Delile | Crot-mac | Euphorbiaceae | Bisana | T | W | Ba | D | Eczema | The bark is crushed and dried. Once dried, it is further ground into a powder. Finally, the powdered bark is mixed with butter and applied to the infected area. | Dermal | MY080 |

| Lf | D | Wart | The dried leaves are ground into a powder and mixed with barley batter to form a paste. This paste is then applied to all the infected areas. | Dermal | |||||||

| Cucumis dipsaceus Ehrenb. ex Spach | Cucu-dip | Cucurbitaceae | Buhie hareg | Cl | W | Lf | F | Fibril illness | The fresh leaves of Haregresa are crushed, squeezed, and the liquid is filtered. Then, the liquid is mixed with sugar and consumed as a drink. | Oral | MY050 |

| Lf | F | Fibril illness | The fresh leaves of Haregresa are crushed, squeezed, and the fluid filtered. Then, this fluid is simply applied as a cream on the body. | Dermal | |||||||

| Cucumis ficifolius A.Rich. | Cucu-fic | Cucurbitaceae | yemidir Embuay | H | HG | Rt | D | Ayne Tila | The fresh root is cut into small pieces and dried. Once dry, it is powdered, and the medicine is either taken orally or inhaled as smoke. | Oral | MY033 |

| Rt | Rabies | The roots of Ensilal, Fiyele Feji, Lutt, Woinagift, Gizewa, and Yemidir Enbuay are pounded together. The resulting dry mixture is then kneaded with teff flour, and the sick person consumes it as bread. | Oral | ||||||||

| Cucurbita pepo L. | Cucu-pep | Cucurbitaceae | Duba | Cl | HG/MK | Fr | F | Abdominal disease | The cooked fruit is eaten by women experiencing the disorder locally known as marat. | Oral | MY037 |

| Cyathula polycephala Baker | Cyat-pol | Amaranthaceae | Chegogot | H | W | Lf | F | Fibril illness | The pounded leaves are squeezed, and the extracted juice is mixed with tea or coffee before being consumed. | Oral | MY036 |

| Cyphostemma cyphopetalum (Fresen.) Desc. ex Wild & R.B.Drumm. | Cyph-cyp | Vitaceae | Gindosh | H | W | Rt | F | Body abscission | The root is crushed into a fine powder, then mixed with a small amount of water and consumed as a drink. | Oral | MY054 |

| Datura stramonium L. | Datu-str | Solanaceae | Astenagr | H | W | Lf | F | Fowel pest | A mixture of Astenagir, Kebercho, garlic, Ahiya Joro, and Woina Gift is pounded and squeezed. The extracted juice is then given to animals suffering from fowl pest. | Oral | MY115 |

| Desmodium ramosissimum G.Don | Desm-rom | Fabaceae | Dirie | Cl | W | Lf | F | Girsha | The leaves are pounded and crushed, then soaked in water. The resulting mixture is applied as a cream to any affected area of the sick person. | Dermal | MY068 |

| Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight & Arn. | Dich-cin | Fabaceae | Ader | T | W | Lf | F | Wart | The dried leaves are crushed, ground into a fine powder, and mixed with barley batter to make a paste. This paste is then applied to the infected areas. | Dermal | MY053 |

| Lf | F | Common cold | The leaves of Ader are steamed, and the resulting vapour is used to fumigate the person affected. | Nasal | |||||||

| Discopodium penninervium Hochst. | Disc-pen | Solanaceae | Ameraro | T | W | Rt | D | Evil eye | The roots of Ameraro, Koshim, and Kitkta are pounded and burned. As the animal inhales the smoke, the harmful spirit is believed to be driven away. | Nasal | MY086 |

| Dodonaea angustifolia L.f. | Dodo-ang | Sapindaceae | kitikta | Sh | W | Lf | D | Plague | The leaves are pounded and dried, then the resulting powder is smoked to treat the plague symptoms. | Nasal | MY029 |

| Lf | F | Fracture | The leaves are pounded and then applied directly to the injured area or tied in place. | Dermal | |||||||

| Lf | D | Skin rash | The leaves of Abalo and Kitikta are pounded and dried, then roasted and mashed. Finally, the resulting mixture is kneaded and applied as a coating to the affected areas of the body. | Dermal | |||||||

| Dovyalis abyssinica (A.Rich.) Warb. | Dovy-aby | Salicaceae | Koshim | T | W | Rt | D | Ayne wog for animal | The roots of Koshim, Ameraro, and Ktkta are first ground and dried, then ground again into a fine powder. Finally, the powder is burned to produce smoke for use in treatment. | Nasal | MY106 |

| Dracaena fischeri Baker | Drac-fis | Dracaenaceae | Wondie-kacha | H | W | Rt | D | Eczema | The root is crushed and dried. After burning, it is powdered, then mixed with butter and finally applied to the infected area. | Dermal | MY025 |

| Echinops kebericho Mesfin | Echi-keb | Asteraceae | Kebercho | H | W/MK | Rt | D | Evil Eye | The root is cut into very small pieces and burned to produce smoke, which is used to fumigate a person suffering from Buda. | Nasal | MY113 |

| Epilobium stereophyllum Fresen. | Epil-ste | Onagraceae | Bega sergie | H | W | Lf | F | Sirey | The leaves of Bega Sergie are pounded and mixed with a small amount of water, then filtered. Finally, a cup of the filtered liquid is drunk before meals for seven days. | Oral | MY099 |

| Erythrina brucei Schweinf. | Eryt-bru | Fabaceae | Gurgo | T | W | Fr | F | Wart | The dried fruit is ground into a powder and mixed with a barley batter to form a paste. This paste is then applied directly to the affected areas. | Dermal | MY052 |

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Euca-glo | Myrtaceae | Nech Baherzaf | T | W/HG | Lf | F | Fibril illness | The steam from the boiled leaves of Nech Baherzaf is used to fumigate the water. | Nasal | MY109 |

| Euclea divinorum Hiern | Eucl-div | Ebenaceae | Dediho | Sh | W | Lf | F | Abscess | The fresh leaves are chewed together with milk, and then the infected areas are smeared with the mixture for six consecutive days. | Dermal | MY041 |

| Rt | D | Ayne Tila | The fresh root is cut into small pieces and dried. Once dried, the root is ground into powder, which is then used for smoking. | Nasal | |||||||

| Lf | F | Eye disease | The fruit of Nesch Shinkurt, the leaves of Dedho, and the fruit of cotton are pounded together. After squeezing, the pure fluid is applied to the infected parts of the eye. | Nasal | |||||||

| Lf | F | Abscess | The whole parts of Tibtibo, bark of Seghed, leaves of Dediho, whole parts of Semeg, and leaves of Jib Mirkuz are massaged with milk and then applied to areas affected by trembling and bitterness. This treatment is repeated by smearing the infected parts for six days. | Dermal | |||||||

| Euphorbia abyssinica J.F.Gmel. | Euph-aby | Euphorbiaceae | Kulkual | T | W | Lf | F | Wound | The leaves of Kulkual are mixed with salt, lemon juice, and ladybird honey. First, the affected areas of the body are coated with white honey, then the prepared medicine is applied to the infected parts repeatedly until they improve. | Dermal | MY097 |

| Euphorbia dumalis S.Carter | Euph-dum | Euphorbiaceae | Anterfa | Sh | W | Lf | D | Haemorrhoid | The entire Anterfa plant and the root of Endohahila are pounded and dried, then ground into a fine powder. This powder is mixed with white powder and finally blended with Vaseline before being applied to the skin. | Dermal | MY110 |

| Euphorbia tirucalli L. | Euph-tir | Euphorbiaceae | Kinchib | Sh | W | Lx | F | Kunchir | Apply the liquid obtained from cutting the stem as a cream to the affected areas. | Dermal | MY096 |

| Festuca glauca Vill. | Fesr-gla | Poaceae | Guassa | H | W | Lf | D | Eczema | The leaves are chopped into small pieces, crushed, and dried. Once dried, they are ground into a fine powder. Finally, the powdered leaves are mixed with butter and applied to the infected area. | Dermal | MY111 |

| Ficus vasta Forssk. | Ficu-vas | Moraceae | Warka | T | W | Ba | D | Eczema | The bark is crushed and dried. Once dry, it is crushed further into a powder, which is then mixed with butter and applied to the infected area. | Dermal | MY062 |

| Lx | F | Wound | The milky white substance from Warka is mixed with salt, lemon juice, and ladybird honey. First, the affected areas of the body are coated with white honey, then the prepared mixture is applied and gently massaged onto the infected parts until healing is achieved. | Dermal | |||||||

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Foen-vul | Apiaceae | Ensilal | Sh | W | Lf | F | Stomachache | The leaves of Ensilal and Timatim are pounded together, and the squeezed juice is consumed as a drink. | Oral | MY117 |

| Glinus lotoides L. | Glin-lot | Molluginaceae | Metere | H | W | Wp | D | Tape warm | All the dried parts of the Metere climber are ground into powder and mixed with powdered barley or Baher Kel. This mixture is then given to a person infected with Kosso to eat. | Oral | MY056 |

| Gossypium herbaceum L. | Goss-heb | Malvaceae | Tit | H | HG/MK | Sd | D | Eye disease | The fruit of Nesch Shinkurt, leaves of Dedho, and cotton seeds are pounded together and then squeezed. The pure liquid extracted is applied to the infected parts of the eye. | Dermal | MY093 |

| Sd | D | Ear | The cotton seeds are boiled and filtered. The filtered liquid is then mixed with Tej and left to ferment for about four days. Finally, the mixture is dropped into the ear. | Ear | |||||||

| Grewia villosa Willd. | Grew-vil | Malvaceae | Lenkuata | Sh | W | Br | F | Retained placenta | The bark is pounded and squeezed, and the extracted pure juice is then drunk by the person suffering from the mentioned ailment. | Oral | MY034 |

| Gymnosporia obscura (A.Rich.) Loes. | Gymn-obs | Celastraceae | Kombel | Sh | W | Lf | D | Ayne Tila | The fresh leaves are cut into very small pieces and then dried. The dried leaves are powdered, and the medicine can be either taken orally or the powder smoked. | Oral | MY020 |

| Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce) J.F.Gmel. | Hage-aby | Rosaceae | Kosso | T | W | Fr | D | Tape warm | The dried fruit of the Kosso tree is powdered and mixed with barley flour. This mixture is then eaten by a person infected with Kosso. | Oral | MY089 |

| Hordeum vulgare L. | Hord-vul | Poaceae | Gebs | H | HG/MK | Lf | F | Dandruff | The pounded leaves of Gebs are squeezed, and the extracted liquid is applied to areas affected by dandruff. | Dermal | MY095 |

| Hylodesmum repandum (Vahl) H.Ohashi & R.R.Mill | Hylo-rep | Fabaceae | Moider | H | W | Rt | F | Wound | The dry, powdered root of Moider is mixed with salt, lemon juice, and ladybird honey. First, the affected areas are coated with white honey, then the prepared mixture is applied on the infected parts and left until healing occurs. | Dermal | MY015 |

| Inula confertiflora A.Rich. | Inul-con | Asteraceae | Woyinagift | Sh | W | Rt | D | Rabies | The roots of Ensilal, Fiyele Feji, Lutt, Woinagift, Gizewa, and Yemidir Enbuay are pounded together. After drying, the mixture is kneaded with teff flour and formed into bread, which the sick person then eats. | Oral | MY072 |

| Jasminum grandiflorum L. | Jasm-gra | Oleaceae | Tenbelel | Cl | W | Lf | F | Snake bite | The leaves are cut into very small pieces and pounded. Then, the preparation is taken as a drink until recovery. | Oral | MY047 |

| Kunchir | The root is pounded, dried, and ground into powder. This powder is then mixed with black teff dough. Finally, the mixture is applied as a cream on the infected areas until healing occurs. | Dermal | |||||||||

| Juniperus procera Hochst. ex Endl. | Juni-pro | Cuppressaceae | Tsid | T | W | Lf | F | Stomach aches | The leaves are ground into a powder and mixed with water. | Oral | MY108 |

| Justicia schimperiana (Hochst. ex Nees) | Just-sch | Acanthaceae | Sensel | Sh | HG/W | Lf | F | Gastric | The leaves of Sensel, fruits of Woyira, Papaya, and Kimmo, along with fluid from Eret, are mixed and ground together. This mixture is then taken daily before meals. | Oral | MY046 |

| Kalanchoe marmorata Baker | Kala-mar | Crassulaceae | Yezinjero kita | Sh | W | Lf | F | Fire burn | The collected leaves of Yezinjero Kita are ground into a paste and applied by tying it onto the injured area. | Dermal | MY061 |

| Kalanchoe petitiana A.Rich. | Kala-pet | Crassulaceae | Endohehila | Sh | W | Lf | F | Wound/lesion | The leaves of Endohehila are heated on embers, then the warm leaves are placed on the wounded area. | Dermal | MY118 |

| Rt | F | Uvula illness | The root is pounded and squeezed to extract the juice. The droplets are then placed in the nose until the infected person sneezes. | Nasal | |||||||

| Keetia lactescens (Hiern) Bridson | Keet-lac | Rubiaceae | Seghed | Sh | W | Br | F | Abscess | The entire parts of Semeg, bark of Seghed, leaves and whole parts of Dediho, along with leaves of Jib Mirkuz, are mixed and massaged with milk, then applied to trembling areas with bitterness. Afterward, the infected parts are smeared with this mixture for six days. | Dermal | MY016 |

| Laggera tomentosa (A.Rich.) Sch.Bip. ex Oliv. & Hiern | Lagg-tom | Asteraceae | keskeso | Sh | W | Rt | D | Evil eye | The fresh root is cut into very small pieces and then dried. After drying, the root is powdered, and the powder is smoked. | Oral | MY031 |

| Lepidium sativum L. | Lepi-sat | Brassicaceae | Feto | H | HG/MK | Wp | D | Malaria | The powdered and crushed leaves of Feto are mixed with water and taken orally as a remedy. | Oral | MY004 |

| Lobelia giberroa Hemsl. | Campanulaceae | Jibira | Sh | W | Rt | D | Evel eye | The roots of Etse Sabe’e, Gizewa, Kestenicha, Yemidir Embuay, Zert Embuay, Jibira, Ahiya Joro Agam, and Sete Ret are pounded together. Once dried, the mixture is ground into a powder and smoked for a person believed to be affected by an evil eye spirit. | Nasal | MY070 | |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. | Lyco-esc | Solanaceae | Timatim | H | HG/MK | Lf | F | Stomach | The leaves are pounded and squeezed, and the extracted liquid is then drunk. | Oral | MY098 |

| Fr | F | Leech for animal | The fruit is pounded, mixed with water, and then drunk. | Oral | |||||||

| Mangifera indica L. | Mang-ind | Anacardiaceae | Mango | T | W/HG | Fr | F | Gastric | The ripe mango fruit is eaten regularly by the sick person before their daily meals. | Oral | MY012 |

| Maytenus arbutifolia (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) R.Wilczek | Mayt-arb | Celasteraceae | Atat | Sh | W | Lf | F | Herpes | The leaves are finely chopped and then pounded. The mixture is left to macerate for three days before being either applied as a cream to the affected areas or consumed as a drink until recovery. | Dermal/Oral | MY058 |

| Morella salicifolia (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Verdc. | More-sal | Myricaceae | Shinet | T | W | Lf | F | Leech | The pounded leaves are mixed with salt and water, then the mixture is used to wash the infected area. | Oral | MY019 |

| Myrtus communis L. | Myri-com | Myrtaceae | Ades | Sh | W | Lf | F | Wart | The dried leaves are pounded, ground, and mixed with barley batter. The mixture is then applied to the infected areas. | Dermal | MY114 |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Ocim-bas | Lamiaceae | Besobila | H | HG/MK | Lf | D | Headache | The leaves of Besobila are dried and powdered to be brewed as a tea, which helps promote a quick recovery. | Oral | MY119 |

| Ocimum forskaolii Benth. | Ocim-for | Lamiaceae | Nana | H | HG | Lf | F | Stress | The leaves of Nana are collected and pounded, then boiled with tea. The tea is consumed after meals. | Oral | MY112 |

| Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. ex Benth. | Ocim-lam | Lamiaceae | Dama kessie | Sh | W/HG | Lf | F | Fibril illness | The leaves of Dama Kessie are cut, squeezed, and the liquid is filtered. This liquid can either be consumed with tea or applied topically to any affected area. | Dermal/Oral | MY066 |

| Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata (Wall. ex G.Don) Cif. | Olea-eur | Oleaceae | Woira | T | W/HG | Lf | F | Herpes | The leaves are finely chopped and pounded, then soaked (macerated) for three days. Afterward, the resulting mixture is applied as a cream to the affected area of the body. | Dermal | MY008 |

| Fr | Gastric | The fruits of kimmo, woyira, and papaya are combined with the juice from *eret* and the leaves of sunsel. This mixture is ground together, and the resulting preparation is taken daily on an empty stomach. | Oral | ||||||||

| Olinia rochetiana A.Juss. | Olin-roc | Oliniaceae | Tifie | Sh | W | Lf | F | Eye disease | The seven leaves of Tfie are cut, then squeezed and filtered. The extract is then applied directly into the infected eye. | Dermal | MY107 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. | Opun-fic | Cactaceae | Baher Qulqual | Sh | W | Fruit | F | Wound | The fruits of Baher Kulkual are mixed with salt, lemon juice, and ladybird honey. First, the affected areas of the body are coated with white honey. Then, the prepared mixture is applied and gently massaged into the infected areas repeatedly until healing occurs. | Dermal | MY055 |

| Osyris quadripartita Salzm. ex Decne. | Osyr-qua | Santalaceae | Keret | Sh | W | Lf | F | Herpes | The leaves are cut into very small pieces and pounded, then macerated for three days. Afterward, the preparation is either applied as a cream to the affected area or consumed as a drink until recovery. | Dermal/Oral | MY013 |

| Rt | Wart | The dried root is ground into powder and mixed with barley batter. This mixture is then applied by smearing it onto all the infected areas. | Dermal | ||||||||

| Otostegia integrifolia Benth. | Otos-int | Lamiaceae | Tinzhut | Sh | W | Rt | F | Snake bite | The root is cut into very small pieces and pounded, then the preparation is consumed regularly until recovery. | Oral | MY009 |

| Lf | Malaria | The powdered and crushed leaves of the plant are taken orally for a duration of seven days. | Oral | ||||||||

| Pennisetum pedicellatum Trin. | Penn-ped | poaceae | Sindedo | H | W | Rt | D | Kunchir | The roots of Sindedo, Goshmika, Shimbrut, and the bulbs of Yejibshinkurt are pounded together and dried. The powdered mixture is then kneaded with Lumen tint and applied as a cream to the infected area. | Dermal | MY116 |

| Persea americana Mill. | Pers-ame | Lauraceae | Avokado | T | W/HG | Fr | F | Madat | Apply cream to the infected area, then wash it with soap after 30 to 60 min. | Dermal | MY082 |

| Fr | F | Dandruff | The infected areas are coated with fresh avocado fruit, and the cream is washed off after 12 h. | Dermal | |||||||

| Phytolacca dodecandra L’Hér. | Phyt-dod | Phytolaccaceae | Mekan endod | Sh | W/HG | Rt | D | Jaundice | The dry root is pounded, then mixed with honey, and a spoonful of this mixture is taken daily before meals. | Oral | MY026 |

| Plantago lanceolata L. | Plant-lan | Plantaginaceae | Worteb | H | W | Lf | D | Wound | The leaves are pounded, dried, and ground into a powder. This powder is then sprinkled or applied to the infected areas. | Dermal | MY003 |

| Plectranthus punctatus (L.f.) L’Hér. | Plec-pun | Lamiaceae | Tibtibo | H | W | Lf | F | Herpes | The leaves are cut into very small pieces and pounded. They are then macerated for three days, after which the resulting preparation is either applied as a cream to the affected area or taken orally until recovery. | Dermal/Oral | MY035 |

| Wp | F | Abscess | The entire parts of Tibtibo, the bark of Seghed, leaves of Dediho, whole parts of Semeg, and leaves of Jib Mirkuz are mixed and massaged with milk. This mixture is then applied to areas experiencing trembling and bitterness. Finally, the infected parts are smeared with the preparation daily for six days. | Dermal | |||||||

| Polygala abyssinica R.Br. ex Fresen. | Ploy-oby | Polygalaceae | Etse- libona | Sh | W | Rt | F | Snake Bite | The root is cut into very small pieces and pounded. The resulting preparation is then drunk regularly until full recovery. | Oral | MY024 |

| Rt | D | Ayne Tila | The fresh root is cut into small pieces and dried. Once dried, it is ground into powder, which can be either ingested as medicine or smoked. | Oral/Nasal | |||||||

| Premna schimperi Engl. | Prem-sch | Lamiaceae | Chocho | Sh | W | Lf | F | Choq | The leaves of Chocho are pounded and mixed with a small amount of warm water. The resulting mixture is then used to wash the infected parts of the animal until it fully recovers. | Dermal | MY085 |

| Pterolobium stellatum (Forssk.) Brenan | Pter-ste | Fabaceae | kentefa | Cl | W | Rt | Evil eye | The fresh roots of Kentefa, Wuyign, Gumaro, Dediho, Shenbeko, and Gizewa are finely chopped and thoroughly dried. Alongside these, the dried leaves of Keskeso and the entire Chikugn plant are also prepared. Once all the ingredients are dried, they are ground into a powder, mixed together, and then burned to produce smoke for use. | Nasal | MY051 | |

| Rhamnus prinoides L’Hér. | Rham-pri | Rhamnaceae | Gesho | Sh | HG/MK | Fr | D | Itch | The fruit is pounded and mixed with butter, then applied to moisten the infected areas. | Dermal | MY038 |

| Rhus quartiniana A.Rich. | Rhus-qua | Anacardiaceae | Chakima | Sh | HG/W | Lf | F | Scorpion | The crushed leaves are bundled and applied to the area where the scorpion has stung. | Dermal | MY032 |

| Rosa abyssinica R.Br. ex Lindl. | Rosa-aby | Rosaceae | Kega | Sh | W | Lf | F | Body swelling | The leaves of Kega, Agam, Woira, and Kenbet are pounded and then squeezed. The resulting liquid is either drunk or applied as a compress to the affected areas. | Dermal/Oral | MY084 |

| Rubus steudneri Schweinf. | Rubu-ste | Rosaceae | Enjori | Sh | W | Fr | D | Wound | The fruit of Enjori is first pounded, dried, and then ground into a fine powder. This powder is then applied directly to the affected areas. | Dermal | MY002 |

| Rumex nepalensis Spreng. | Rume-nep | polygonaceae | Tult | H | W | Rt | D | Rabbis | The roots of Ensilal, Fiyele Feji, Lutt, Woinagift, Gizewa, and Yemidir Enbuay are pounded together. The dried mixture is then kneaded with teff flour, and the resulting dough is consumed by the sick person as bread. | Oral | MY043 |

| Rumex nervosus Vahl | Rume-ner | Polygonaceae | Embuacho | Sh | W | Lf | F | Wound | The leaves of Embuacho are mixed with salt, lemon juice, and ladybird honey. First, the affected body parts are coated with white honey, then the locally prepared medicine is applied repeatedly to the infected areas until healing occurs. | Dermal | MY040 |

| Ruta chalepensis L. | Ruta-cha | Rutaceae | Tenaadam | Sh | HG/MK | Wp | D | Kunchir | The root is crushed, dried, and ground into a powder. This powder is then mixed with black teff dough to form a paste, which is applied as a cream to the infected areas until healing occurs. | Dermal | MY063 |

| Wp | F | Evil sprit | The entire parts of Chiqugn, Tiena Adam, and Nech Shinkutr are crushed together, and the resulting substance is then sniffed. | Nasal | |||||||

| Saccharum officinarum L. | Sacc-off | Poaceae | Shenkora | Sh | HG/MK | St | F | Gastric | The stem of Shenkora is eaten directly before meals. | Oral | MY087 |

| Schinus molle L. | Schi-mol | Anacardiaceae | Kundo Berbere | T | W/HG | Lf | D | Plague | The leaves are pounded and dried, then smoked during a plague outbreak. | Nasal | MY102 |

| Fr | D | Evil eye | The dried fruit is burned in front of the person believed to be affected by an evil eye spirit. | Nasal | |||||||

| Searsia glutinosa (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Moffett | Sear-glu | Anacardiaceae | Qimmo | Sh | W | Fr | D | Gastric | The fruits of Kimmo, Woyira, Papaya, the juice of Eret, and leaves of Sunsel are mixed and ground together. This mixture is then taken daily before meals. | Oral | MY103 |

| Searsia retinorrhoea (Steud. ex Oliv.) Moffett | Sear-ret | Anacardiaceae | Tilem | Sh | W | Lf | F | Liver infection | The leaves are dried, crushed, and boiled. The resulting liquid is then filtered through a clean cloth and consumed as a drink. | Oral | MY081 |

| Senna singueana (Delile) Lock | Senn- sin | Fabaceae | Gufa | Sh | W | Lf | F | Herpes | The leaves are cut into very small pieces and pounded. They are then macerated for three days before being used either as a cream applied to the affected area or taken orally until recovery. | Dermal/Oral | MY042 |

| Sida schimperiana Hochst. ex A.Rich. | Sida-sch | Malvaceae | Chifrig | Sh | W | Rt | D | Evil eye | The roots of Etse Sabe’e, Gizewa, Kestenicha, Yemidir Embuay, Zert Embuay, Jibira, Ahiya Joro Agam, Chifrig, and Sete Ret are pounded together. After drying, the mixture is ground into a powder and smoked for a person believed to be affected by an evil eye spirit. | Nasal | MY067 |

| Solanum anguivi Lam. | Sola-ang | Solanaceae | Zert Embuay | Sh | W | Rt | D | Evil eye | The roots of Etse Sabe’e, Gizewa, Kestenicha, Yemidir Embuay, Zert Embuay, Jibira, Ahiya Joro Agam, and Sete Ret are pounded together. After drying, the mixture is ground into a powder and smoked for a person believed to be affected by an evil eye spirit. | Nasal | MY074 |

| Steganotaenia araliacea Hochst. | Steg-ara | Apiaceae | Jib mirkuz | H | W | Lf | F | Abscess | Leaves of Yejib Mirkuz, Dediho, and the whole parts of Tibtibo, Semeg, along with the bark of Seged, are pounded and soaked. Then, the resulting mixture is applied to the infected areas and smeared for six days. | Dermal | MY017 |

| Stephania abyssinica (Quart.-Dill. & A.Rich.) Walp. | Step-aby | Menispermaceae | Etse Iyesus | Cl | W | Rt | D | Ayne tila | The roots of Etse-Eyesus, Aleblabit, Yemidir Embuay, Qestenicha, Sete-Eret, and Chifirg are ground, dried, and milled. The resulting powder is then mixed with white honey and eaten before any other food. | Oral | MY088 |

| Rt | F | Body swelling | The root of Etse-Iyesus is ground and squeezed, and the extracted liquid is applied as a cream to the infected area. | Dermal | |||||||

| Tacazzea conferta N.E.Br. | Taca-con | Apocynaceae | Shimbrut Hareg | Cl | W | Lf | F | Snake Bite | The leaves are finely chopped and pounded, then consumed as a drink until recovery. | Oral | MY069 |

| Tagetes minuta L. | Tage-min | Asteraceae | Gimie | H | W | Lf | F | Moybagegn for animal | The leaves of Gimie are first crushed and squeezed to extract their juice. This extract is then diluted with water and given to infected animals as a treatment through drenching. | Oral | MY104 |

| Tragia brevipes Pax. | Tagi-bre | Euphorbiaceae | Alebilabit | H | W | Rt | D | Ayne tila | The fresh root is cut into small pieces and dried. Once dried, it is ground into powder, which is then either taken orally or smoked for medicinal purposes. | Oral/Nasal | MY022 |

| Urtica simensis Hochst. ex A.Rich. | Urti-sim | Urticaceae | Sama | H | W | Lf | F | Gastric | The leaves of Sama are gathered and cooked like wot (stew), then eaten plain with injera. | Oral | MY090 |

| Lf | F | Gonorrhea | The leaves of Sama and the bark of Bisana are pounded and powdered, then mixed with water and filtered. Finally, a cup of the filtered liquid is taken every morning for five days. | Oral | |||||||

| Verbascum sinaiticum Benth. | Verb-sin | Scrophulariaceae | Ahiya joro/Ketetina | H | W | Rt | F | Snake bite | The root is cut into very small pieces and pounded, then the resulting preparation is consumed until recovery. | Oral | MY027 |

| Lf | Wound | The dried and powdered leaves of ketetina were mixed with salt, lemon juice, and ladybird honey. First, the affected areas were coated with white honey, then the locally prepared mixture was applied and left on the infected parts until healing occurred. | Dermal | ||||||||

| Rt | Jaundice | The roots of ketetina along with the roots and leaves of atuch were pounded together, then crushed into smaller pieces, and finally brewed into tea for the patient to drink. | Oral | ||||||||

| Verbena officinalis L. | Verb-off | Verbenaceae | Atuch | H | W | Rt/Lf | F | Jaundice | The root of ketetina is combined with either the root or leaves of atuch, and the mixture is pounded together. After being thoroughly crushed, it is prepared like tea, which the sick person then drinks. | Oral | MY001 |

| Vernonia amygidalia Del. | Vern-amy | Asteraceae | Girawa | Sh | W/HG | Lf | F | Dandruff | The leaves are pounded and squeezed to extract the liquid, which is then applied to the infected areas of the body. | Dermal | MY101 |

| Lf | F | Athlet foot | The leaves of Girawa are ground, and the extracted liquid is applied to the foot. | Dermal | |||||||

| Vernonia leopoldi (Sch.Bip. ex Walp.) Vatke | Vern-leo | Asteraceae | Wuyign | Sh | W | Lf | F | Herpes | The leaves were finely chopped into small pieces and pounded. They were then soaked for three days before the resulting mixture was applied as a cream to the affected area until the person fully recovered. | Dermal | MY028 |

| Rt | D | Haemorrhoid | The cut root of wuyign is first heated over a fire until it burns, then it is applied directly to the hemorrhoid to cauterize the area. | Dermal | |||||||

| Vicia faba L. | Vici-fab | Fabaceae | Bakela | H | HG/MK | Sd | D | Diarrhea | The seeds of Bakela are soaked in water and then perforated. Afterwards, they are worn around the neck as conchoidal or mollusk-like ornaments. | Dermal | MY120 |

| Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal | With-som | Solanaceae | Gizewa | Sh | W/HG | Rt | D | Ayne tila | The fresh root is cut into small pieces and dried. After drying, the root is ground into powder, which is then either consumed as a drink or inhaled by smoking. | Oral/Nasal | MY023 |

| Rt | D | Rabies | The roots of Ensilal, Fiyele Feji, Lutt, Woinagift, Gizewa, and Yemidir Enbuay are pounded together. The resulting mixture is dried, then kneaded with teff flour, and finally consumed by the patient in the form of bread. | Nasal | |||||||

| Zehneria scabra (L.f.) Sond. | Zehn-sca | Cucurbitaceae | Etse- Sabeq | Cl | W | Rt | D | Evil eye | The roots of Etse Sabe’e, Gizewa, Kestenicha, Yemidir Embuay, Zert Embuay, Jibira, Ahiya Joro Agam, and Sete Ret are pounded together. The dried mixture is then powdered and smoked for a person suffering from an evil eye spirit. | Nasal | MY049 |