Abstract

The in-plane diffusivelike motion of membrane bound proteins on the surface of cells is considered. We suggest, on the basis of theoretical arguments and simulation, that thermally excited undulations of the lipid bilayer may serve as a mechanism for proteins to hop between adjacent regions on the cell surface separated by barriers composed of internal cellular structure (e.g., the cytoskeleton). We specifically investigate the mobility of band 3 dimer on the surface of red blood cells where the spectrin cytoskeletal meshwork defines a series of “corrals” on the cell surface known to hinder protein motion. Previous models of this system have postulated that the cytoskeleton must deform to allow passage of membrane bound proteins out of these corral regions and have ignored fluctuations of the bilayer. Our model provides a complementary mechanism and we posit that the mobility of real proteins in real cells is likely the result of several mechanisms acting in parallel.

INTRODUCTION

Proteins that span the cell membrane mediate communication between the cell and its surroundings (Lodish et al., 1995). Here we define communication in its broadest possible sense to include the exchange of information, materials and/or energy. A complete picture of how cells function and interact with their immediate surroundings requires a detailed understanding of how these membrane bound proteins function, not only as single protein units, but also as dynamic components of the membrane environment where they reside.

One fundamental, and easily studied, property of membrane bound proteins is protein mobility in the plane of the membrane surface. Such mobility has consequences for cellular functioning (Lauffenburger and Linderman, 1993; Giancotti and Ruoslahti, 1999; Berg and Purcell, 1977) and, interestingly, even such a simple observable can exhibit vastly different quantitative and qualitative behaviors depending on the specifics of the cellular system being studied (Saxton and Jacobson, 1997). Many proteins exhibit diffusive motion on the surface of the cell, which is consistent with the simplest traditional models of the cell membrane, e.g. the fluid mosaic model (Singer and Nicolson, 1972; Saffman and Delbruck, 1975). Some systems display other forms of motion however. In extreme examples, membrane bound proteins may show no motion on experimental time and length scales (Webb et al., 1981) or may exhibit ballistic motion with a well defined velocity (Wilson et al., 1996). Quite often it is impossible to characterize protein motion as simply being stationary, diffusive or ballistic (Saxton and Jacobson, 1997; Feder et al., 1996). In these cases the motion is often referred to as being anomalously diffusive, which simply means that the mean square displacement of the protein grows with a nonintegral power of time between 0 and 2. Many different models can be invoked to explain these various dynamical behaviors for membrane proteins (Jacobson et al., 1995; Saxton and Jacobson, 1997). Quite generally it is necessary to know something about the internal structure and biochemistry of the cell to have a hope of understanding what factors contribute to the observed mobilities.

The cellular cytoskeleton is often linked to the mobility (or lack thereof) of proteins spanning the membrane surface (Fleming, 1987; Saxton and Jacobson, 1997; Winckler et al., 1999; Saxton, 1990b). Erythrocytes and, in particular, band 3 protein on the surface of erythrocytes have been particularly well studied in this context (Cherry, 1979; Schindler et al., 1980; Sheetz et al., 1980; Koppel et al., 1981; Sheetz, 1983). The dense regular network of spectrin filaments attached to the red blood cell membrane creates a series of corrals in which proteins exhibit bound diffusive behavior (Fig. 1). Occasionally, a protein may escape from its corral to a neighboring corral and this infrequent hopping from corral to corral to corral defines a random walk on a much slower time scale than the diffusive motion observed within the confines of the corral. This model for protein mobility where two diffusion constants coexist (a microscopic diffusion constant for motion within a corral and a macroscopic diffusion constant for global motion over the surface of the cell) because of the interference of the cellular cytoskeleton has become known as the “matrix” (Sheetz, 1983) or “skeleton fence” (Kusumi et al., 1993) model.

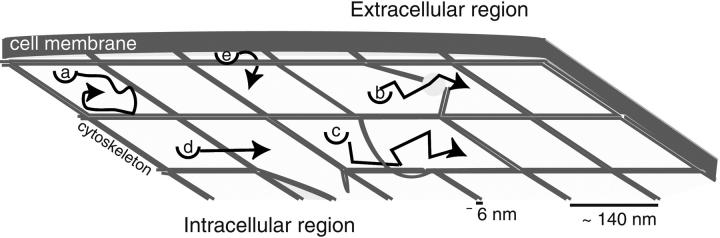

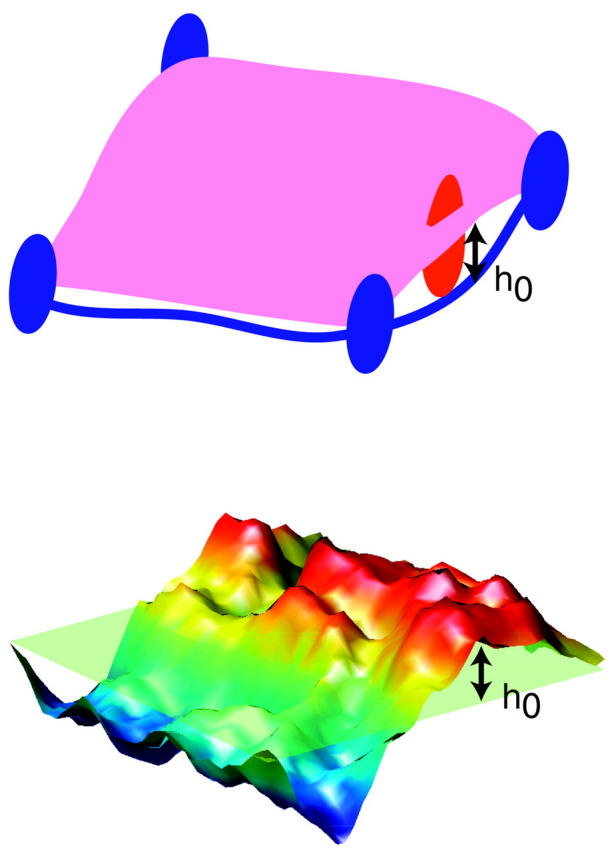

FIGURE 1.

Schematic illustration of the behavior of transmembrane proteins in the red blood cell. The cytoskeleton immediately below the membrane hinders protein transport by confining the protein temporarily to a localized corral (a). Jumps from one corral to another occur slowly and have previously been postulated to result from dynamic reorganization of the cytoskeletal matrix (either by dissociation of spectrin tetramers (b) or thermal fluctuations in the shape of the cytoskeleton (c)) or by infrequent crossing events where the protein is thermally kicked hard enough to force its way over a relatively static cytoskeleton (d). The present study considers a different possibility—shape fluctuations of the lipid bilayer may allow for corral hopping (e).

Though the basic picture of the skeleton fence model seems to have held up to increasingly stringent experimental tests (at least for red blood cells) (Tsuji and Ohnishi, 1986; Tsuji et al., 1988; Edidin et al., 1991; Corbett et al., 1994; Kusumi and Sako, 1996; Tomishige, 1997; Tomishige et al., 1998), we still do not fully understand how global motion over the cell surface occurs. Though we know that proteins are occasionally able to escape from corrals on the red blood cell, we do not know what conditions allow this to happen. In the language of physical chemistry, we have limited understanding of the reaction coordinate for passage between adjacent corrals. Previous theoretical studies have either utilized very general models to fit the experimental data (Saxton, 1995) or have assumed that rearrangements of the spectrin network are necessary for a protein to escape confinement (Saxton, 1989; Saxton, 1990a; Saxton, 1990b; Boal, 1994; Boal and Boey, 1995; Leitner et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2000). In this paper we present another alternative, that the lipid bilayer itself may deform in such a way as to promote passage of the membrane protein over a spectrin filament (Fig. 1).

The dynamic nature of phospholipid bilayers is well documented. In the red blood cell, for example, thermal undulations of the membrane surface have been implicated in the flicker effect (Brochard and Lennon, 1975). Under appropriate concentrations of osmolites, cells and vesicles enclose less volume than the surface area of the membrane would suggest (Dai and Sheetz, 1995; Helfrich and Servuss, 1984), a fact clearly demonstrated when external stimuli act to draw out the membrane surface (Fygenson et al., 1997). And, thermally excited membrane undulations have been implicated in microscopic mechanisms for cellular motility (Peskin et al., 1993). The above observations rely upon the fact that membranes typically enclose a volume less than maximal for a given surface area. For some simple cellular systems (e.g. the red blood cell where complex structures like microvilli, coated pits, etc. do not exist), this excess area is taken up by undulations of the bilayer surface. Such undulations evolve in time as a result of thermal motion.

Theoretical work on lipid bilayers and related systems has shown that fairly simple mathematical treatments of bilayer dynamics are often in good agreement with experiment. Models appropriate to the red blood cell under physiological conditions typically include only a bending rigidity for bilayer energetics (Helfrich, 1973) and treat dynamics within the framework of linear response (Milner and Safran, 1987; Schneider et al., 1984; Brochard and Lennon, 1975; Granek, 1997). The resulting equations for membrane dynamics are well suited for simple simulation as well as analytical study although we are unaware of previous studies to exploit this fact. We will outline a simple Fourier space Brownian dynamics algorithm that allows us to stochastically evolve a thermal membrane surface forward in time. The ensemble of evolving membrane shapes lead us to conclude that thermal membrane undulations are likely to play a role in global protein transport over the surface of erythrocytes.

The organization of this paper is as follows. In the next section we present a brief review of the equations governing membrane dynamics in the linear response regime and derive our Fourier space Brownian dynamics algorithm to exploit the simplicity of these equations within a simulation framework. The following sections make connection between these dynamic membrane undulations and the regulation of transmembrane protein transport on cell surfaces both through theoretical arguments and simulation. Our results indicate that thermal membrane undulations may play an important role in the motion of transmembrane proteins. In the last section we discuss our results and conclude.

A DYNAMIC MEMBRANE MODEL

A popular tool for dynamic studies of membrane systems is molecular dynamics (MD) simulation (Tieleman et al., 1997). MD simulation of lipid bilayers has become popular because it clear that much biology depends upon the dynamic properties of the lipid bilayer and the techniques of MD are very well established. There are, however, many interesting problems related to dynamic membrane behavior that are completely inaccessible to MD simulation under current computational limitations. The diffusion of membrane bound proteins is one example, but essentially any behavior that occurs on length scales longer than tens of nanometers and time scales slower than tens of nanoseconds is inaccessible to MD simulation. Dynamic simulations on simplified bilayer models (where lipids are represented as spheres or ellipsoids, etc.) have seen some discussion in the recent literature (Drouffe et al., 1991; Goetz and Lipowsky, 1998; Shelley et al., 2001; Ayton et al., 2001), but such techniques are in their infancy and it remains to be seen what role they will play in the study of biology.

Previous theoretical studies of the properties of biological membranes over length scales too large for direct MD simulation have, in large part, concentrated on the static elastic properties of lipid bilayers in the tradition of the work of Helfrich (Helfrich, 1973). Thermal fluctuations of the membrane surface have been theoretically implicated in the temperature dependent interactions between membrane bound inclusions (i.e. proteins) (Golestanian et al., 1996; Goulian et al., 1993) and in changes to membrane rigidity with temperature (Helfrich, 1985). The time dependence of thermal fluctuations has been analytically examined through the study of autocorrelation functions (Milner and Safran, 1987; Schneider et al., 1984; Brochard and Lennon, 1975; Granek, 1997), which led to a purely physical explanation of the flicker effect in erythrocytes (Brochard and Lennon, 1975). A recent study of the immunological synapse (Qi et al., 2001) has utilized a time-dependent Landau-Ginzburg model for membrane dynamics, but in a regime where thermal fluctuations do not play an important role. The only previous work we are aware of that has utilized a dynamically fluctuating elastic membrane simulation is a study by Laradji on polymer adsorption to membranes (Laradji, 1999). This study simplified computation by suppressing fluctuations in one of the two directions defining the membrane plane and by ignoring hydrodynamic contributions to the dynamics.

We shall model a thermally fluctuating membrane surface by converting the equations of linear response that have been previously derived for membrane dynamics (Brochard and Lennon, 1975; Schneider et al., 1984; Milner and Safran, 1987; Granek, 1997) into an efficient numerical scheme for evolving a free membrane sheet in time. The starting point for our algorithm is the Helfrich bending free-energy for small deformations (Helfrich, 1973)

|

(1) |

|

in its real space (top) and Fourier space (bottom) formulations. Here h(x,y) is the displacement of the membrane surface away from the xy plane that defines the zero energy configuration of the membrane. Kc is the bending modulus, L is the linear dimension of the membrane surface and k are the wavevectors defining the displacement in Fourier space,  . The Fourier description is appealing because each of the normal modes,

. The Fourier description is appealing because each of the normal modes,  , is independent.

, is independent.

Under the low Reynolds number conditions of the cellular environment (Purcell, 1977) an overdamped description of the membrane's dynamics is appropriate and the assumptions of linear response provide us with a Langevin description for the dynamics of each one of these modes

|

(2) |

where ω(k) is the relaxation frequency for mode  and

and  is the corresponding component of the (Gaussian white) noise that is related to ω(k) by the usual fluctuation-dissipation relationship (VanKampen, 1992). These relaxation frequencies, including hydrodynamic effects from coupling between membrane and cytoplasm, have been calculated (Brochard and Lennon, 1975; Schneider et al., 1984; Granek, 1997) as

is the corresponding component of the (Gaussian white) noise that is related to ω(k) by the usual fluctuation-dissipation relationship (VanKampen, 1992). These relaxation frequencies, including hydrodynamic effects from coupling between membrane and cytoplasm, have been calculated (Brochard and Lennon, 1975; Schneider et al., 1984; Granek, 1997) as

|

(3) |

with η the viscosity of the surrounding solvent. In the case of a cell membrane η is taken to be the viscosity of the cytoplasm which dominates the (much lower) viscosity of the surrounding water. To simulate the dynamics of Eq. 2 it is more convenient and completely equivalent to draw displacements from the associated Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process (VanKampen, 1992)

|

(4) |

|

|

Here,  is the equilibrium probability distribution for the mode

is the equilibrium probability distribution for the mode  and

and  is the conditional probability density for the mode to take a value of

is the conditional probability density for the mode to take a value of  at time t given a zero time value for the mode of

at time t given a zero time value for the mode of  . Temperature, which enters the through the random force and the fluctuation-dissipation relationship, is found in

. Temperature, which enters the through the random force and the fluctuation-dissipation relationship, is found in  where kb is Boltzmann's constant. These probability densities are solutions to the Fokker-Planck formulation of Langevin Eq. 2. Although we have used times t and 0 in the equation, the same probability arises for any times τ, τ′ with τ − τ′ = t because the process is Markovian. As the above probability distributions are Gaussian, it is a simple matter to evolve

where kb is Boltzmann's constant. These probability densities are solutions to the Fokker-Planck formulation of Langevin Eq. 2. Although we have used times t and 0 in the equation, the same probability arises for any times τ, τ′ with τ − τ′ = t because the process is Markovian. As the above probability distributions are Gaussian, it is a simple matter to evolve  forward in time utilizing standard normal deviate generators (Press et al., 1994).

forward in time utilizing standard normal deviate generators (Press et al., 1994).

The simplicity of Eq. 2 in k space has allowed for arbitrarily large time steps with perfect accuracy. The simulation scheme described here is essentially the traditional Brownian dynamics (BD) algorithm (Ermak and McCammon, 1978), although this implementation is unusual in that the dynamics are performed in Fourier space and the dynamics are ultrasimple because the system is completely harmonic. We believe this to be the first implementation of a Fourier space based dynamic simulation algorithm for membrane surfaces, but we note that Fourier space Monte Carlo algorithms have been introduced previously by Gouliaev and Nagle (Gouliaev and Nagle, 1998b, Gouliaev and Nagle, 1998a). Fig. 2 displays a representative time series of membrane structures computed using this algorithm with parameters (Kc,η,L,T) chosen to represent the red blood cell membrane and as tabulated in Table 1 .

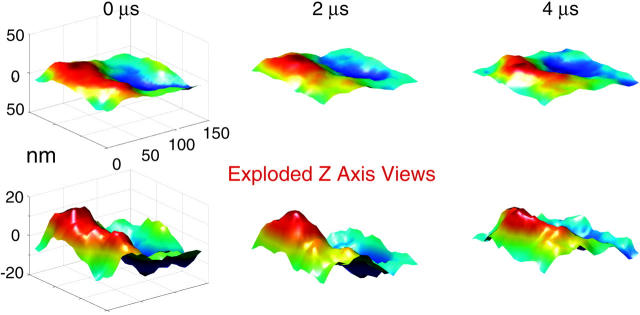

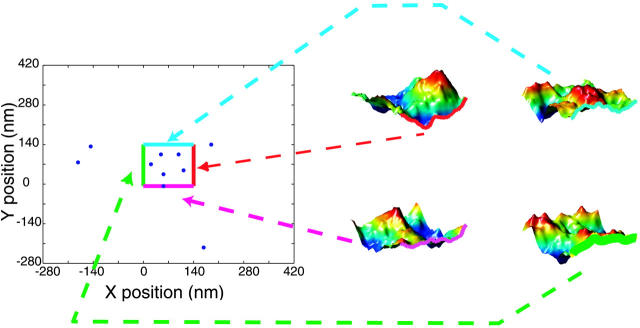

FIGURE 2.

A time series of snapshots for a dynamic membrane surface obtained from one realization of the stochastic formula Eq. 4 utilizing physical parameters appropriate for red blood cells under physiological conditions (Table 1). The bottom row is identical to the top row, but with the z axis expanded to emphasize small wavelength fluctuations. Note that the long wavelength modes are relatively stable over this time scale, but shorter wavelength excitations are evolving. This behavior is to be expected from the k dependence in Eq. 3.

TABLE 1.

Simulation parameters for band 3 on erythrocyte membrane

| Parameter | Description | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kc | Bending modulus |  |

* |

| η | Cytoplasm viscosity | 0.06 poise | * |

| T | Temperature | 37°C | Body temp. |

|

Depth of cytoplasmic domain of band 3 | 6 nm | † |

| L | Corral dimension | 140 nm | ‡,§,¶ |

| D | Band 3 diffusion constant |  |

‡,§ |

|

Initial number of dimers per corral | 33 | ¶ |

| l | Lattice spacing (diameter of dimer) | 7 nm | ¶ |

| Δt | Random walk time step | 2.3 × 10−5 s | ¶ |

CONNECTION TO PROTEIN MOBILITY

The motivating hypothesis for this study is that membrane undulations may serve as a mechanism for global protein transport over the surface of the red blood cell. In the previous section, we derived a set of probabilistic equations for the stochastic evolution of a square sheet of membrane in the absence of tension and with periodic boundary conditions. In this section we argue that these equations imply an effective dynamic gating at the edge of the corral regions that places the macroscopic diffusion coefficient approximately in the range observed by experiment. In the following section we discuss simulations that couple this dynamic gating to protein diffusion to assess the more quantitative implications of our model.

We shall approximate the geometry of a spectrin corral as a square with sides of length 140 nm (Brown et al., 2000; Tomishige, 1997; Tomishige et al., 1998). Though the geometry of a true erythrocyte spectrin corral would more correctly be represented as a triangle (Lodish et al., 1995; Steck, 1989), this approximation allows for a simple analytical treatment of the membrane surface (as shown above) and has been invoked previously for other models of transport in the band 3-red blood cell system (Leitner et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2000). Additionally, corral shape is not expected to strongly influence the escape of proteins out of a corral region once an effective gating mechanism at the corral boundary has been specified (Saxton, 1995).

We are interested in obtaining from the temporal evolution implied by Eq. 4 the statistical prevalence of height fluctuations larger than the dimension of the cytoplasmic domain of band 3 in the direction normal to the membrane plane. Recent experiments have shown this length to be ∼6 nm (Zhang et al., 2000). Our model assumes that a band 3 dimer will bump into the cytoskeleton as it laterally diffuses unless the membrane is 6 nm or higher than baseline. Inasmuch as the intention of this model is to assess the importance of thermal membrane undulations, we neglect motion of the cytoskeleton. The possibility of cytoskeletal dynamics affecting intercorral jumps has been examined elsewhere (Saxton, 1989, 1990a,b; Boal, 1994; Boal and Boey, 1995; Leitner et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2000).

A cartoon for the relation between membrane, band 3 dimer and the spectrin cytoskeleton is displayed in Fig. 3. Ideally, our model for membrane dynamics within the corral region would include pinning to the cytoskeleton at approximately four sites (the points of spectrin-membrane attachment via ankyrin (Steck, 1989) at approximately the midpoint of each spectrin chain segment). Unfortunately, such pinning would render a dynamic model beyond the realm of simple analytical treatment. Though theories do exist to predict the conformations and partition function of pinned or anchored membranes (see for example (Weikl and Lipowsky, 2000)) we are unaware of any work dealing with such interactions within a dynamic model and, as we will argue, dynamic fluctuations are of paramount importance in this system. We therefore simulate the membrane undulations as though the membrane were a free sheet. Interactions with the cytoskeleton are included indirectly by truncating the sheet to the size of the corral (thus eliminating modes of motion at longer wavelengths than the corral dimension) and setting the k = 0 mode of the sheet initially equal to zero. Inasmuch as ω0 = 0, this mode remains unexcited over all times. By virtue of  , h0 = 0 implies that the average height displacement of the membrane over the entire corral is zero. This restriction effectively pins the membrane to the plane of the cytoskeleton by requiring that any fluctuation above the cytoskeleton at a given r be compensated for by a negative fluctuation elsewhere. Large fluctuations are effectively quenched by this mechanism, albeit in a manner arguably different than that imposed by a series of pinning sites across the membrane surface. Interactions between the diffusing protein and the cytoskeleton are also indirectly included in our model. The local height of the membrane surface will be used to model a dynamic gating function at the corral boundaries. Proteins are free to pass when the gate is open, but are otherwise trapped. This gating behavior will be discussed further below.

, h0 = 0 implies that the average height displacement of the membrane over the entire corral is zero. This restriction effectively pins the membrane to the plane of the cytoskeleton by requiring that any fluctuation above the cytoskeleton at a given r be compensated for by a negative fluctuation elsewhere. Large fluctuations are effectively quenched by this mechanism, albeit in a manner arguably different than that imposed by a series of pinning sites across the membrane surface. Interactions between the diffusing protein and the cytoskeleton are also indirectly included in our model. The local height of the membrane surface will be used to model a dynamic gating function at the corral boundaries. Proteins are free to pass when the gate is open, but are otherwise trapped. This gating behavior will be discussed further below.

FIGURE 3.

A comparison between the structure of the membrane surface in erythrocytes and our simplified model. In the cell, the lipid bilayer is attached to the spectrin skeleton via ankyrin, a transmembrane protein that attaches to the midpoints of each spectrin chain. A mobile protein has a chance to escape the corral only when a fluctuation causes a gap of at least h0 between spectrin and the bilayer sheet. In this work we concentrate on membrane fluctuations as opposed to rearrangements of the spectrin network. In our model, the membrane within a corral region is modeled as an elastic sheet subject to curvature energetics and thermal fluctuations within a periodic square geometry. The sheet is pinned to baseline (the plane of the cytoskeleton) by virtue of a vanishing amplitude for the k = 0 Fourier mode of the system. Fluctuations in height of this sheet at a given point in the x,y plane mimic the shape fluctuations of the membrane surface within a corral. Heights greater than h0 allow for passage of a protein dimer within our model whereas smaller (or negative) displacements do not.

The first question we may ask is what is the equilibrium probability for h(r) to exceed the h0 = 6 nm minimum fluctuation height to allow protein hopping to occur? Inasmuch as our membrane Hamiltonian is quadratic in h(r), we know that the probability distribution for h(r) must be Gaussian and, consequently, may be calculated from the second moment of h(r) alone (VanKampen, 1992). This calculation is conveniently carried out in Fourier space to yield (angular brackets indicate averaging over the canonical distribution defined by the Hamiltonian of Eq. 1)

|

(5) |

so that

|

(6) |

From this we see that the probability for h to exceed h0 is given by an error function

|

(7) |

Here, Θ(x) is the Heaviside step function. Fig. 4 plots this function for h0 in the range of 2–10 nm. We see that for h0 = 6 nm the probability is ∼15%. On this basis, we might expect that we could model the macroscopic diffusion over the surface of the cell as resulting from diffusion on a plane with semipermeable barriers (spectrin filaments) that allow passage of the protein in 15% of the cases when a protein bumps into it. In fact, such a model would give agreement with experiment only when the transmission probability is lower by two orders of magnitude (Brown et al., 2000). The resolution to this discrepancy is to consider the dynamics of the system as opposed to the statics. Yes, there is a protein sized gap between membrane and cytoskeleton ∼15% of the time, but this number is irrelevant if such openings are too short-lived to allow a protein to diffuse over the cytoskeletal barrier (see a related discussion on transition regions in the paper by Leitner et al. (Leitner et al., 2000)). To address this question, consider the number correlation function for greater than h0 fluctuations defined by

|

(8) |

This function serves as a measure of the statistical prevalence for a fluctuation with amplitude greater than h0 to last for time t. We have evaluated this function by generating a time series of membrane conformations in Fourier space via eq. 4, transforming to real space and averaging over time. We emphasize that the maximal k vector included in this procedure was π/7 nm−1 which was chosen to neglect fluctuations at the length scale of the band 3 dimer or shorter. The result of this process is plotted in Fig. 5. The relevant time scale to consider is the time associated with diffusive motion of the protein over a distance comparable to traversing the spectrin barrier. Because the radius of the dimer and spectrin filament are each ∼3–4 nm (Boal and Boey, 1995; Tomishige, 1997; Zhang et al., 2000; Leitner et al., 2000), we want to know the characteristic time for diffusion of the dimer a distance of approximately l = 7 nm (this scale also corresponds to the level of precision in our previous study (Brown et al., 2000) and will be used in the simulations of the next section). Given that the microscopic diffusion coefficient for a band 3 dimer is 0.53 μm2 s−1 we estimate the time for barrier traversal to be approximately  . Our correlation function at a time of 2.3 × 10−5 s (the ending point for the data in Fig. 5) is ∼9%.

. Our correlation function at a time of 2.3 × 10−5 s (the ending point for the data in Fig. 5) is ∼9%.

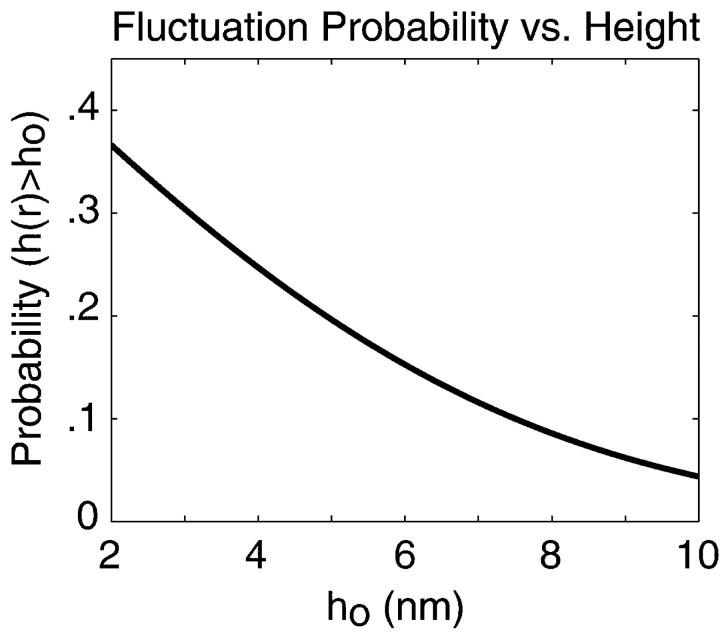

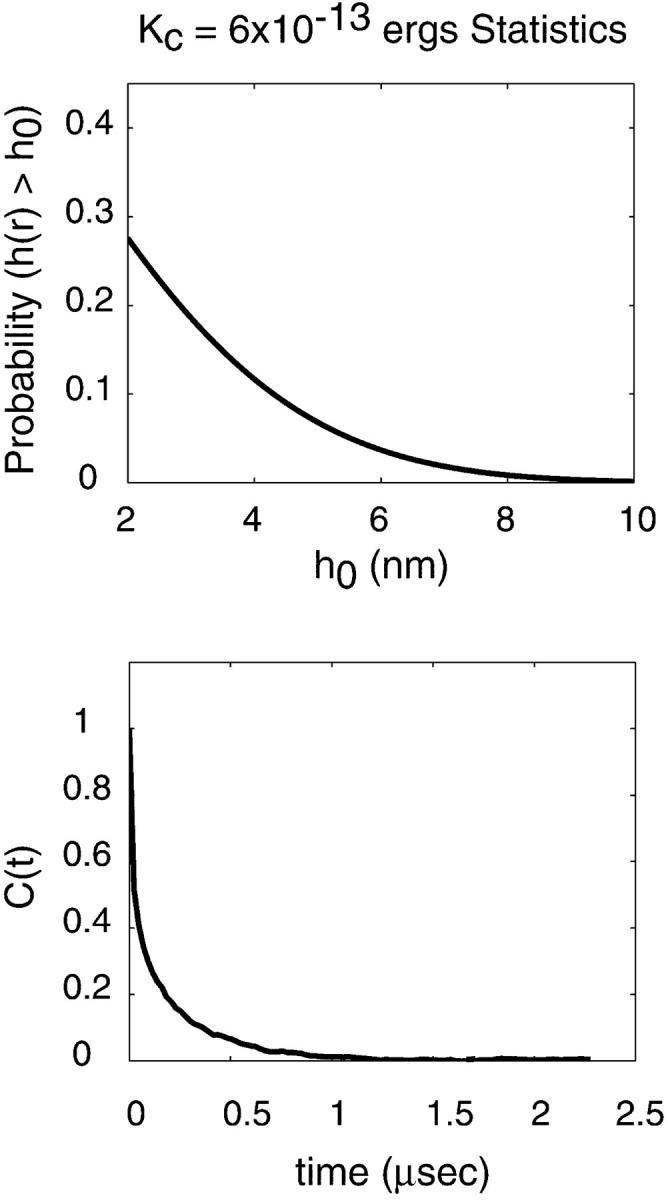

FIGURE 4.

The equilibrium probability that h(r) exceeds h0 as a function of h0. This plot is simply an error function as defined by Eq. 7. For h0 = 6 nm, this probability is ∼15%.

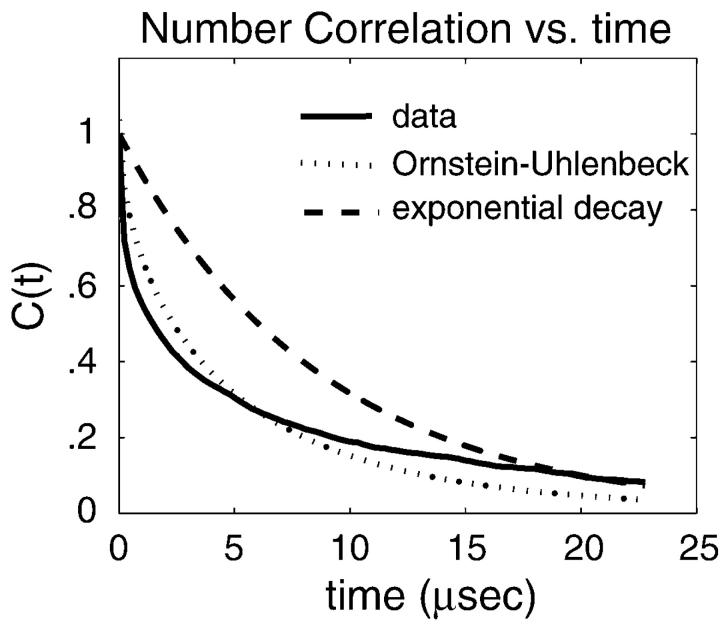

FIGURE 5.

The number correlation function, C(t) as a function of time for  height fluctuations as expressed in Eq. 8. The solid line represents the results for our model. For comparison, the dashed line is an exponential fit to this data and the dotted line is a fit to the data assuming the stochastic process could be modeled as a diffusive motion in a 1D harmonic well (see text and Eq. 9). The comparisons demonstrate that correlations decay over multiple time scales (as expected from the wavevector dependence of the decay constants in the model) and that the process is more complex than might be expected. At a time of

height fluctuations as expressed in Eq. 8. The solid line represents the results for our model. For comparison, the dashed line is an exponential fit to this data and the dotted line is a fit to the data assuming the stochastic process could be modeled as a diffusive motion in a 1D harmonic well (see text and Eq. 9). The comparisons demonstrate that correlations decay over multiple time scales (as expected from the wavevector dependence of the decay constants in the model) and that the process is more complex than might be expected. At a time of  the function has decayed to 9%.

the function has decayed to 9%.

Also plotted in Fig. 5 are two simpler functional forms for correlation functions that we have fit to the data. The first fit is a simple exponential decay. Clearly, this is a very poor approximation—decaying much too slowly at early times and too quickly at later times. This is not unexpected because we would expect exponential decay for Markovian jumping between two well-defined states with a physical barrier to cross and we have no such barrier in this case; h0 is just an arbitrary height within the context of the fluctuating membrane equations. The second functional form is obtained by assuming the membrane motion normal to the plane at a given x,y point may be described as diffusion in a harmonic well (i.e., the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process) of width implied by the Gaussian form of the equilibrium probability distribution (Eq. 6). The value of the effective diffusion constant, obtained by fitting to the true correlation function, is determined to be  . We note that the functional form for this decay is given as (Zhou et al., 1998)

. We note that the functional form for this decay is given as (Zhou et al., 1998)

|

(9) |

|

|

|

Though this functional form does a better job of reproducing the decay of the correlation function, it still decays too slowly at early times and too quickly at long times. The superposition of all the modes of the membrane sheet contribute to C(t) and so we should not be surprised that a simple one-dimensional model is unable to reproduce the decay exactly. In a qualitative sense, C(t) reflects many superposed stochastic processes with a similar form to Eq. 9, but with differing  values and variances. The superposition of these modes gives rise to decays over many different time scales and hence we see both quickly and slowly decaying components in the total correlation function. Long wavelength undulations provide the slowly decaying tail of C(t) and the short time dynamics are given by short wavelength excitations superposed upon this. The fact that the correlation function reflects relaxation over a distribution of timescales suggests that it might be possible to fit the data to stretched-exponential relaxation. Over the time scale displayed, we find that we can indeed fit the correlation function with the functional form

values and variances. The superposition of these modes gives rise to decays over many different time scales and hence we see both quickly and slowly decaying components in the total correlation function. Long wavelength undulations provide the slowly decaying tail of C(t) and the short time dynamics are given by short wavelength excitations superposed upon this. The fact that the correlation function reflects relaxation over a distribution of timescales suggests that it might be possible to fit the data to stretched-exponential relaxation. Over the time scale displayed, we find that we can indeed fit the correlation function with the functional form  . Within the resolution of Fig. 5, this fit is indistinguishable from the data.

. Within the resolution of Fig. 5, this fit is indistinguishable from the data.

Returning to the question of protein mobility across the cell surface, we now realize that both the equilibrium probability to find a large membrane-cytoskeleton gap and the probability that this gap will persist for Δt must contribute to an effective permeability of the spectrin network. Inasmuch as both of these contributions are of order 10%, we expect a reasonable value for a transmission probability to be of order 1%. This number is in better agreement with previous statistical analyses (Brown et al., 2000), but is still in error by an order of magnitude. To see this, consider a simple mean-field type approach to calculating the escape rate implied by such a permeability. Breaking up the corral interior into a grid of points 7 nm apart (as we shall do in the next section) leads to 400 enclosed points within a 140 nm × 140 nm corral. Of these, 76 (19%) are adjacent to the corral boundary. The probability for a single protein to escape over a Δt time step will be approximately equal to  (i.e., the probability that the protein is next to the barrier times the probability that the barrier is open over the characteristic diffusive timescale times the probability that the protein moves out of the corral as opposed to another direction). This corresponds to a protein exit rate from the corral of about 20 s−1 which is approximately an order of magnitude faster than that observed experimentally (Tomishige et al., 1998).

(i.e., the probability that the protein is next to the barrier times the probability that the barrier is open over the characteristic diffusive timescale times the probability that the protein moves out of the corral as opposed to another direction). This corresponds to a protein exit rate from the corral of about 20 s−1 which is approximately an order of magnitude faster than that observed experimentally (Tomishige et al., 1998).

For completeness, we note that a threefold higher value of the assumed bending modulus for the membrane, Kc, leads to an effective permeability of 1.5 × 10−4 (Fig. 6). This strong dependence on Kc and the complicated nature of C(t) should make it clear that ambiguities in our physical parameters will strongly affect the numerical value of these results. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that the underlying stochastic process is complex and hence characterizing the dynamics of h(r) through a single two time correlation function is insufficient to fully understand the dynamics of the coupled protein-membrane-bilayer system. In the following section we carry out further simulations to make this ambiguity manifest. Still, on a qualitative level we see that all physical parameters in the right ballpark for an undulating membrane to contribute to the observed macroscopic diffusion of band 3 on erythrocytes. This certainly does not exclude other mechanisms, but serves as a reminder that in complex systems it is difficult, if not impossible, to guess what the reaction coordinate for any particular process may be. Based on very simple physical principles, the above arguments suggest that membrane undulations are expected to play a role in protein mobility on red blood cells.

FIGURE 6.

Figures analogous to Figs. 4 and 5, but using a value of  for the bending modulus. The stiffening of the membrane by a factor of three leads to obvious lowering of the probability for the sheet to attain a height of h0 = 6 nm as well as a reduced probability that such a fluctuation will persist over the time scale of band 3 diffusion.

for the bending modulus. The stiffening of the membrane by a factor of three leads to obvious lowering of the probability for the sheet to attain a height of h0 = 6 nm as well as a reduced probability that such a fluctuation will persist over the time scale of band 3 diffusion.

SIMULATIONS

The arguments of the preceding section are appealing in their simplicity, but required certain approximations. Some of these approximations are physical in nature (square corrals, homogeneous bending rigidity for the membrane, exclusion of cytoskeletal motion, periodic boundary conditions with pinning to the cytoskeleton approximated by no net translation of the sheet) and were invoked to provide a simplified model to pinpoint the effect of a particular physical phenomenon. The relationship between P(h), C(t) and the protein's macroscopic diffusion constant, on the other hand, was treated very qualitatively and this may be viewed as a mathematical approximation that requires verification. In this section we describe simulations that couple protein diffusion to the membrane undulations, thus explicitly demonstrating the shortcomings of the simplified treatment above. These simulations lead us to the conclusion that our lack of detailed microscopic understanding of the membrane-protein-cytoskeleton system makes it impossible to compare to experiment without introducing a fitting parameter in our model. The presence of such a parameter (and indeed of similar parameters in all other dynamic models discussed in the literature (Saxton, 1989, 1990a,b; Leitner et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2000)) makes it impossible to distinguish a membrane undulation mechanism as proposed here from mechanisms involving cytoskeletal rearrangement as discussed elsewhere. Given the qualitative agreement of all these models with existing experiments, we feel it is likely that some or all such mechanisms may contribute to the global diffusion of proteins across the spectrin barriers present in the red blood cell.

Our simulation methodology is similar to one published previously (Brown et al., 2000). Global diffusivity of band 3 is studied by calculating the decay rate for proteins out of a single corral. Proteins interact with the spectrin network as described below, but not with one another. Individual stochastic runs are seeded with an initial random distribution of N0 = 33 band 3 dimers per corral and the population is allowed to decay over the course of 50,000 time steps as this distribution of proteins slowly escape confinement. Statistics were generated by repeating this process 10 times to generate approximate decay curves. Protein diffusion is simulated as a random walk on a square lattice with lattice spacing of 7 nm. The microscopic diffusion coefficient of the band 3 dimer, 0.53 μm2 s−1 then sets our simulation time step at 2.3 × 10−5 s. This spacing in time and space was chosen for computational convenience and because further refining of the mesh in space is impossible without a detailed knowledge of the band 3, spectrin interactions. We do not know the form of interaction between these two proteins and hence spatial resolution at the scale (or below) of the individual proteins would be ill defined. We shall see that this lack of resolution does prove problematic, but no more so than in other theoretical studies of this system.

We assume that undulations of the membrane surface only affect diffusion of band 3 through modulation of interaction between band 3 and spectrin and that this modulation is entirely due to the z direction motion of band 3 relative to spectrin as defined by the height of the membrane sheet above the cytoskeletal network. Furthermore, we assume that passage of band 3 over spectrin is only allowed when the undulation is higher than h0 for some significant fraction of the time step of our simulation. We will define “significant fraction” in the following paragraphs. Our simulation procedure is then as follows. We evolve the random walk in time on the lattice. When a random step carries the protein through a corral barrier we determine if that move is allowed by the conformation of the membrane sheet over the entire time step (the membrane fluctuations are sampled more frequently than the random walk). If yes, the move proceeds as anticipated. If no, the protein is returned to its position before the attempted barrier jump. To avoid possible spurious correlation effects resulting from our simplified pinning procedure, we sample not one, but 4 equivalent but stochastically independent membrane surfaces—one for each of the sides of the square corral (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

An illustration of our simulation methodology. 33 noninteracting protein dimers (blue circles) are randomly paced within a corral at t = 0 and are allowed to undergo a random walk. Proteins that attempt to cross over a barrier in a given time step are reflected back or allowed to make the jump depending on the local height of the membrane surface at the attempted crossing site over the duration of the walk time step. Passage of the protein is allowed only if  at the site of attempted crossing for each intermediate sampling time within the random walk time step. Different membrane sampling rates affect the rate of protein loss from the corral (see Fig. 8). The height distribution along each edge of the corral is independently simulated as a single line across a given realization of the stochastic process of Eq. 4. In total, four independent membrane sheets are evolved forward in time—one for each edge of the corral. Four sheets were used to eliminate artificial correlation artifacts arising from the periodic boundary conditions on each sheet.

at the site of attempted crossing for each intermediate sampling time within the random walk time step. Different membrane sampling rates affect the rate of protein loss from the corral (see Fig. 8). The height distribution along each edge of the corral is independently simulated as a single line across a given realization of the stochastic process of Eq. 4. In total, four independent membrane sheets are evolved forward in time—one for each edge of the corral. Four sheets were used to eliminate artificial correlation artifacts arising from the periodic boundary conditions on each sheet.

In Fig. 8 we have plotted population decay curves for four different sampling rates of membrane conformations ranging from 10 to 100 sampling points over the duration of each random walk step time. Clearly there is a dependence on sampling frequency in these decay curves. Naively, one might expect the limit of infinite sampling to be the case we are interested in (unobstructed passage of band 3 over spectrin) and presumably the most direct comparison to the analytical work described above. We argue that this is not necessarily true. As stressed earlier, we are not certain of the microscopic interactions between all the components in this system. Requiring the membrane to remain above h0 for the duration of the diffusive crossing event is tantamount to us saying that the only way for the protein to get over the barrier is for the barrier to be completely unobstructed for 2.3 × 10−5 s. We simply can not make this determination and, indeed, to find agreement with experiment (decay rate ∼2–6 s−1 (Tomishige, 1997; Tomishige et al., 1998)) we must assume a sampling rate of ∼10/Δt–40/Δt (4.4 × 105 s−1−1.7 × 106 s−1). We also point out that our analytical work involving the number correlation function does not require the fluctuations to remain above h0 at all times. Instead it looks for the extra probability (beyond that expected for measurement infinitely separated in time) that a system which started above h0 is later above h0 again. Because our system displays fluctuations of differing amplitudes and time scales it is possible for a slow mode (long wavelength) to remain excited over a time long compared to protein diffusive motion. Superimposed on top of this we will see short-lived short wavelength excitations which may knock the surface under h0 without drastically changing the shape of the membrane surface and with only minimal incursion below h0 (see Fig. 2). It is the relative importance of such brief incursions that we are unable to account for theoretically and which lead to the ambiguity in the model.

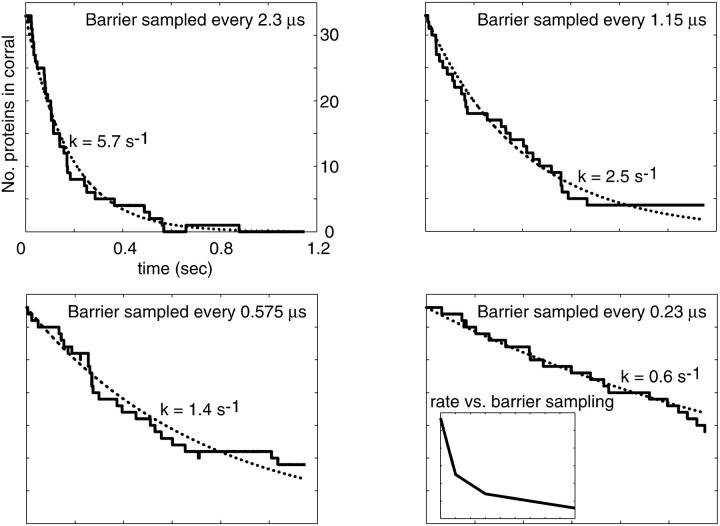

FIGURE 8.

Simulation results for different membrane gating sampling rates corresponding to 10×, 20×, 40×, and 100× the random walk sampling rate (1/Δt) of  The solid lines represent individual simulations with 33 random walkers and the dashed lines exponential fits to decay curves obtained by averaging over 10 such simulations. The inset shows the decay rate as a function of sampling, which demonstrates that even at a gate sampling rate of 4.4 × 106 s−1 the results are not converged. If viewed as a fitting parameter, a gate sampling rate in the neighborhood of 10× to

The solid lines represent individual simulations with 33 random walkers and the dashed lines exponential fits to decay curves obtained by averaging over 10 such simulations. The inset shows the decay rate as a function of sampling, which demonstrates that even at a gate sampling rate of 4.4 × 106 s−1 the results are not converged. If viewed as a fitting parameter, a gate sampling rate in the neighborhood of 10× to  would lead to the best agreement with experimental results. Histograms of escape waiting times lead to exponential wait time distributions

would lead to the best agreement with experimental results. Histograms of escape waiting times lead to exponential wait time distributions  as expected for infrequent opportunities to escape the corral.

as expected for infrequent opportunities to escape the corral.

Our methodology does not allow for coupling between protein motion and membrane dynamics except through the gating effect we have used to model the band 3-spectrin steric interaction. Because we cannot include more realistic forms of coupling without resorting to a massive simulation, which would require interaction strengths, etc. as inputs, we have halted our study at this semi-quantitative level with a fitting parameter. It is unlikely that a realistic simulation could be performed on these length and time scales with current computer capabilities, even if we were privy to the molecular forces involved at the nanometer scale. Our study is thus limited in its quantitative predictive power, but the qualitative message seems clear. Membrane fluctuations are expected to exist in erythrocytes under physiological conditions and the magnitude and dynamics of these fluctuations are in qualitative agreement with the observed mobility of band 3 on the surface of red blood cells. Without much more sophisticated modeling we are unable to speculate as to the relative importance of this mechanism as opposed to mechanisms involving cytoskeletal rearrangement. We point out that our studies here are at a level of detail comparable to previous studies and our results are similarly robust. In all likelihood, the transport of transmembrane proteins relies on a variety of different thermal motions to enable passage through obstacles on the cell surface.

DISCUSSION

We regard this report to be a confirmation of plausibility. Our model has used the simplest possible physical representation of the lipid bilayer and has not properly accounted for the interactions between bilayer, protein and spectrin cytoskeleton. Nevertheless, this picture has merit as a zeroth-order model. The simplicity of the model has allowed for analytical and semi-analytical results to be obtained that surely would not be derivable from more complicated theories/simulations. Also, we have performed simple simulations on the length scale of hundreds of nanometers and time scale of seconds. It would be extremely difficult (if not impossible given current computing limitations) to pursue traditional simulation techniques such as molecular dynamics or Brownian dynamics (even with simplified lipid/fluid models) over such scales.

Over the course of this study we were forced to invoke approximations to make the model more tractable to simplified simulation and analysis. Among the most obvious are our lack of pinning to the cytoskeleton, the use of a constant Kc (even in the vicinity of the protein), and the numerical value chosen for Kc which is based upon experimental measurement over length scales far exceeding those discussed here. Though these approximations are quite severe, we believe that they represent the natural assumptions one comes to in studying this system. It is worth mentioning that the value of 2 × 10−13 ergs used for Kc in this study was taken directly from experimental measurements on intact red cells (Brochard and Lennon, 1975). Effects arising from protein inclusions and attachment to the cytoskeleton are therefore present in this number in an averaged sense. In the absence of more microscopically obtained experimental data, we have used the numbers available to us. This study has also implicitly assumed protein lateral diffusion and membrane undulations to be uncoupled processes (except for the gating effect at the corral edge). It is possible for two such motions to become coupled under certain circumstances (see for example (Kumar et al., 2001)), but again we appeal to the fact that the band 3 diffusion constant D is an experimentally determined parameter. Any correlations that we have neglected are thus accounted for in D in an averaged sense (though explicit correlation is neglected).

Though the quantitative results of our study are surely affected by such assumptions, we do not believe that they should alter our qualitative conclusion that thermal membrane undulations play a role in protein transport over membrane surfaces with underlying cellular structure. Thermal fluctuations surely influence the behavior of lipid bilayer surfaces and the estimates discussed in the current work strongly suggest that such fluctuations may be just as important as other mechanisms that have previously been implicated in the global diffusivity of proteins on the surface of cells.

For concreteness, we have concentrated in this work on the diffusion of band 3 in red cells, but the physical principles at play in this system should be applicable to other cellular systems. Epithelial cells, nerve cells and fibroblasts, as well as red blood cells, all seem to exhibit characteristics of systems where the cytoskeleton hinders free diffusion of membrane bound proteins (Fleming, 1987; Saxton and Jacobson, 1997; Winckler et al., 1999; Sako and Kusumi, 1995). The physical constants necessary for our analysis are less firmly characterized for these other systems than for erythrocytes, but it seems reasonable to expect that dynamic membrane undulations will affect the motion of membrane bound proteins in these other cells as well.

In conclusion, we have presented a simple algorithm to generate time series of thermal membrane undulations derived from the elasticity equations of Helfrich (Helfrich, 1973) and the equations of linear response derived by many authors (Milner and Safran, 1987; Schneider et al., 1984; Brochard and Lennon, 1975; Granek, 1997). We have utilized this approach to generate statistics on the duration and amplitude of thermal membrane undulations over the length scale of red blood cell corrals and have concluded that these undulations appear to be capable of contributing to the observed macroscopic diffusion constant of band 3 dimer over erythrocyte membranes. Though the physical principles discussed here were applied to the system of band 3 dimer on the surface of erythrocytes, it seems plausible that similar effects may exist in other cellular systems. Recent experiments on cellular membranes utilizing single molecule techniques (Fujiwara et al., 2002) and laser tweezers and related mechanical techniques (Discher, 2000) hold promise for investigating the effects discussed in this work and for providing the necessary data to test advanced models of protein mobility in red blood cells and other cellular systems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant MCB-0203221).

APPENDIX

The text has referred to exponential fits on a number of occasions. We used the following procedure to obtain approximate decay constants for data collected over the range [0,X].

Suppose the data to fit is represented as the function f(x) (assumed normalized to 1 at x = 0). If this data was an exponentially decaying function with decay constant k it would integrate to

|

(A-1) |

In general f(x) is not a simple exponential and the integral over [0,X] is just a number, but we find the exponential approximation to f(x) by requiring the two integrals to equal one another

|

(A-2) |

so that we may obtain k from the relation

|

(A-3) |

which is solved by Newton's method. Numerical estimates of I(X) are calculated by quadrature.

References

- Ayton, G., S. G. Bardenhagen, P. McMurty, D. Sulsky, and G. A. Voth. 2001. Interfacing continuum and molecular dynamics: An application to lipid bilayers. J. Chem. Phys. 114:6913–6924. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, H. C., and E. M. Purcell. 1977. Physics of chemoreception. Biophys. J. 20:193–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boal, D. H. 1994. Computer simulation of a model network for the erythrocyte cytoskeleton. Biophys. J. 67:521–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boal, D. H., and S. K. Boey. 1995. Barrier-free paths of directed protein motion in the erythrocyte plasma membrane. Biophys. J. 69:372–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochard, F., and J. F. Lennon. 1975. Frequency spectrum of the flicker phenomenon in erythrocytes. J. Phys. (Paris). 36:1035–1047 [Google Scholar]

- Brown, F. L. H., D. M. Leitner, J. A. McCammon, and K. R. Wilson. 2000. Lateral diffusion of membrane proteins in the presence of static and dynamic corrals: suggestions for appropriate observables. Biophys. J. 78:2257–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, R. J. 1979. Rotational and lateral diffusion of membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 559:289–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, J. D., P. Agre, J. Palek, and D. E. Golan. 1994. Differential control of band 3 lateral and rotational mobility in intact red cells. J. Clin. Invest. 94:683–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J., and M. P. Sheetz. 1995. Regulation of endocytosis, exocytosis and shape by membrane tension. In Protein Kinesis: Dynamics of Protein Trafficking and Stability. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York. 567–571 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Discher, D. E. 2000. New insights into erythrocyte membrane organization and microelasticity. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 7:117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouffe, J.-M., A. C. Maggs, and S. Leibler. 1991. Computer simulations of self-assembled membranes. Science. 254:1353–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edidin, M., S. C. Kuo, and M. P. Sheetz. 1991. Lateral movements of membrane glycoproteins restricted by dynamic cytoplasmic barriers. Science. 254:1379–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermak, D. L., and J. A. McCammon. 1978. Brownian dynamics with hydrodynamic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 69:1352–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Feder, T. J., I. Brust-Mascher, J. P. Slattery, B. Baird, and W. W. Webb. 1996. Constrained diffusion or immobile fraction on cell surfaces: a new interpretation. Biophys. J. 70:2767–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, T. P. 1987. Trapped by a skeleton – the maintenance of epithelial membrane dynamics. Bioessays. 7:179–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, T., K. Ritchie, H. Murakoshi, K. Jacobson, and A. Kusumi. 2002. Phospholipids undergo hop diffusion in compartmentalized cell membrane. J. Cell Biol. 157:1071–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fygenson, D. K., J. F. Marko, and A. Libchaber. 1997. Mechanics of microtubule-based membrane extension. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79:4497–4500. [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti, F. G., and E. Ruoslahti. 1999. Integrin signaling. Science. 285:1028–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, R., and R. Lipowsky. 1998. Computer simulations of bilayer membranes: Self assembly and interfacial tension. J. Chem. Phys. 108:7397–7409. [Google Scholar]

- Golestanian, R., M. Goulian, and M. Kardar. 1996. Fluctuation-induced interactions between rods on a membrane. Phys. Rev. Lett. 54:6725–6734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouliaev, N., and J. F. Nagle. 1998a. Simulations of a single membrane between two walls using a monte carlo method. Phys. Rev. E. 58:881–888. [Google Scholar]

- Gouliaev, N., and J. F. Nagle. 1998b. Simulations of interacting membranes in the soft confinement regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81:2610–2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulian, M., M. Bruinsma, and P. Pincus. 1993. Long-range forces in heterogeneous fluid membranes. Europhys. Lett. 22:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Granek, R. 1997. From semi-flexible polymers to membranes: anomalous diffusion and reptation. J. Phys. II (Paris). 7:1761–1788. [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich, W. 1973. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: Theory and possible experiments. Z. Naturforsch. [C]. 28:693–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich, W. 1985. Effect of thermal undulations on the rigidity of fluid membranes and interfaces. J. Phys. (Paris). 46:1263–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich, W., and R. M. Servuss. 1984. Undulations, steric interactions and cohesion of fluid membranes. Nuovo Cimento D. 3:137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, K., E. D. Sheets, and R. Simson. 1995. Revisiting the fluid mosaic model of membranes. Science. 268:1441–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppel, D. E., M. P. Sheetz, and M. Schindler. 1981. Matrix control of protein diffusion in biological membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 78:3576–3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P. B. S., G. Gompper, and R. Lipowsky. 2001. Budding dynamics of multicomponent membranes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86:3911–3914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumi, A., and Y. Sako. 1996. Cell surface organization by the membrane skeleton. Curr. Opin. Cell Bio. 8:566–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumi, A., Y. Sako, and M. Yamamoto. 1993. Confined lateral diffusion of membrane receptors as studied by single particle tracking. effects of calcium-induced differentiation in cultured epithelial cells. Biophys. J. 65:2021–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laradji, M. 1999. Polymer adsorption on fluctuating surfaces. Europhys. Lett. 47:694–700. [Google Scholar]

- Lauffenburger, D. A., and J. J. Linderman. 1993. Receptors: Models for Binding, Trafficking and Signaling. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Leitner, D. M., F. L. H. Brown, and K. R. Wilson. 2000. Regulation of protein mobility in cell membranes: a dynamic corral model. Biophys. J. 78:125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodish, H., D. Baltimore, A. Berk, S. L. Zipursky, P. Matsudaira, and J. Darnell. 1995. Molecular Cell Biology. 3rd ed. Scientific American Books, New York.

- Milner, S. T., and S. A. Safran. 1987. Dynamical fluctuations of droplet microemulsions and vesicles. Phys. Rev. A. 36:4371–4379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskin, C. S., G. M. Odell, and G. F. Oster. 1993. Cellular motions and thermal fluctuations: the brownian ratchet. Biophys. J. 65:316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press, W. H., S. A Teukolsky, W. T. Vetterling, and B. P. Flannery. 1994. Numerical Recipes in C. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Purcell, E. M. 1977. Life at low reynolds number. Am. J. Phys. 45:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, S. Y., J. T. Groves, and A. K. Chakraborty. 2001. Synaptic pattern formation during cellular recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:6548–6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffman, P. G., and M. Delbruck. 1975. Brownian motion in biological membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 73:3111–3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako, Y., and A. Kusumi. 1995. Barriers for lateral diffusion of transferrin receptor in the plasma membrane as characterized by receptor dragging by laser tweezers: fence versus tether. J. Cell. Bio. 129:1559–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, M. J. 1989. The spectrin network as a barrier to lateral diffusion in erythrocytes: A percolation analysis. Biophys. J. 55:21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, M. J. 1990a. The membrane skeleton of erythrocytes: A percolation model. Biophys. J. 57:1167–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, M. J. 1990b. The membrane skeleton of erythrocytes: Models of its effect on lateral diffusion. Int. J. Biochem. 22:801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, M. J. 1995. Single-particle tracking: Effects of corrals. Biophys. J. 69:389–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, M. J., and K. Jacobson. 1997. Single particle tracking: Applications to membrane dynamics. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 26:373–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, M., D. E. Koppel, and M. P. Sheetz. 1980. Modulation of protein lateral mobility by polyphosphates and polyamines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 77:1457–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M. B., J. T. Jenkins, and W. W. Webb. 1984. Thermal fluctuations of large quasi-spherical bimolecular phospholipid vesicles. J. Phys. (Paris). 45:1457–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheetz, M. P. 1983. Membrane skeletal dynamics: Role in modulation of red blood cell deformability, mobility of transmembrane proteins, and shape. Semin. Hematol. 20:175–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheetz, M. P., M. Schindler, and D. E. Koppel. 1980. The lateral mobility of integral membrane proteins is increased in spherocytic erythrocytes. Nature. 285:510–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley, J. C., M. Y. Shelley, R. C. Reeder, S. Bandyopadhyay, and M. L. Klein. 2001. A coarse grain model for phospholipid simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 105:4464–4470. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, S. J., and G. L. Nicolson. 1972. The fluid mosaic model of the structure of cell membranes. Science. 175:720–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck, T. L. 1989. Red cell shape. In Cell Shape: Determinants, Regulation and Regulatory Role. W. Stein, and F. Bronner, editors. Academic Press, New York. 205–246.

- Tieleman, D. P., S. J. Marrink, and H. J. Berendsen. 1997. A computer perspective of membranes: molecular dynamics studies of lipid bilayer systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1331:235–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomishige, M. 1997. Regulation mechanism of the lateral diffusion of band 3 in erythrocyte membranes: corralling and binding effects of the membrane skeleton. Ph.D. thesis. The University of Tokyo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tomishige, M., Y. Sako, and A. Kusumi. 1998. Regulation mechanism of the lateral diffusion of band 3 in erythrocyte membranes by the membrane skeleton. J. Cell Bio. 142:989–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, A., K. Kawasaki, S. Ohnishi, H. Merkle, and A. Kusumi. 1988. Regulation of band 3 mobilities in erythrocyte ghost membranes by protein association and cytoskeletal meshwork. Biochemistry. 27:7447–7452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, A., and S. Ohnishi. 1986. Restriction of the lateral motion of band 3 in the erythrocyte membrane by the cytoskeletal network: Dependence on spectrin association state. Biochemistry. 25:6133–6139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanKampen, N. G. 1992. Stochastic Processes in Physics and Chemistry. North-Holland, Amsterdam.

- Webb, W. W., L. S. Barak, D. W. Tank, and E.-S. Wu. 1981. Molecular mobility on the cell surface. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 46:191–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weikl, T. R., and R. Lipowsky. 2000. Local adhesion of membranes to striped surface domains. Langmuir. 16:9338–9346. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K. M., I. E. G. Morrson, P. R. Smith, N. Fernandez, and N. Cherry. 1996. Single particle tracking of cell-surface hla-dr molecules using r-phycoerythrin labeled monoclonal antibodies and fluorescence digital imaging. J. Cell Sci. 109:2101–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winckler, B., P. Forscher, and I. Mellman. 1999. A diffusion barrier maintains distribution of membrane proteins in polarized neurons. Nature. 397:698–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D., A. Klyatkin, J. T. Bolin, and P. S. Low. 2000. Crystallographic structure and functional interpretation of the cytoplasmic domain of erythrocyte membrane band 3. Blood. 96:2925–2933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.-X., S. T. Wlodek, and J. A. McCammon. 1998. Conformation gating as a mechanism for enzyme specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:9280–9283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]