Abstract

Previous studies have shown that the skeletal dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) pore subunit CaV1.1 (α1S) physically interacts with ryanodine receptor type 1 (RyR1), and a molecular signal is transmitted from α1S to RyR1 to trigger excitation-contraction (EC) coupling. We show that the β-subunit of the skeletal DHPR also binds RyR1 and participates in this signaling process. A novel binding site for the DHPR β1a-subunit was mapped to the M3201 to W3661 region of RyR1. In vitro binding experiments showed that the strength of the interaction is controlled by K3495KKRR _ _ R3502, a cluster of positively charged residues. Phenotypic expression of skeletal-type EC coupling by RyR1 with mutations in the K3495KKRR _ _ R3502 cluster was evaluated in dyspedic myotubes. The results indicated that charge neutralization or deletion severely depressed the magnitude of RyR1-mediated Ca2+ transients coupled to voltage-dependent activation of the DHPR. Meantime the Ca2+ content of the sarcoplasmic reticulum was not affected, and the amplitude and activation kinetics of the DHPR Ca2+ currents were slightly affected. The data show that the DHPR β-subunit, like α1S, interacts directly with RyR1 and is critical for the generation of high-speed Ca2+ signals coupled to membrane depolarization. These findings indicate that EC coupling in skeletal muscle involves the interplay of at least two subunits of the DHPR, namely α1S and β1a, interacting with possibly different domains of RyR1.

Keywords: confocal imaging, intracellular calcium, skeletal muscle, voltage-gated ion channels, protein–protein interaction

Skeletal muscle cells respond to membrane action potentials with an elevation in cytosolic Ca2+ that develops rapidly and is a graded function of voltage. The mechanism that couples muscle membrane excitation to the cytosolic Ca2+ increase, also known as excitation-contraction (EC) coupling, is made possible by the strict functional and structural relationship of the dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) and ryanodine receptor type 1 (RyR1) (1). Direct or indirect physical contact between these two Ca2+ channels is thought to ensure that charge movements in the DHPR are transduced at high speed into a conformational change that opens the RyR1 channel, leading to a massive release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Multiple approaches have suggested that the cytosolic loop linking repeats II and III of α1S binds RyR1 and/or is responsible for the conformational change that opens the RyR1 channel (2–10). However, α1S domains outside the II–III loop also bind RyR1 (11) and, furthermore, the functional recovery produced by the II–III loop, in the absence of other skeletal domains, is incomplete (12). Thus, despite the structural and functional significance of the II–III loop, other molecular determinants may influence coupling between the skeletal DHPR and RyR1.

The pore subunit of the DHPR is tightly bound to a β-subunit that modulates multiple processes ranging from the voltage dependence of the gating current to trafficking of the Ca2+ channel to the plasma membrane (13–16). Inactivation of the β1 gene in skeletal muscle led to a decrease in α1-subunit expression and the elimination of EC coupling (17). However, β1a and α1S coexpression experiments in dysgenic myotubes (lacking α1S) have shown that EC coupling could be observed in the absence of β1a (18). The common experience gained from heterologous expression systems has been that β-subunits from different tissues are highly interchangeable among Ca2+ channels (13). In skeletal myotubes, several nonmuscle β variants can be integrated into an otherwise skeletal DHPR to generate Ca2+ currents, but the EC coupling function specifically requires the endogenous variant β1a (19). A unique heptad repeat in the C terminus of β1a, unrelated to membrane trafficking, was found to be essential for skeletal-type EC coupling (19). The latter observation raises the question of whether the β1a-subunit binds RyR1 and in this way directly influences EC coupling. Recent crystallographic studies show that the common core of the β-subunit consists of a tandem of two protein modules, an N-terminal SH3 (Src homology region 3) domain and a C-terminal GK (guanylate kinase) domain (20, 21). The studies further show that the GK module interacts with α1, whereas the SH3 module, found in many protein–protein interactions, is exposed to the cytosol (20). Bearing in mind this topology and the tight coupling that exists between the cytosolic faces of the DHPR and RyR1, an interaction of β1a with RyR1 seems likely. The same conclusion can be reached from models depicting the arrangement of the skeletal DHPR over the foot structure of RyR1 (22, 23). In the present article, we mapped a binding domain in RyR1 for the skeletal DHPR β1a-subunit and described the EC coupling phenotype of mutations in RyR1 that disrupt binding of the β-subunit.

Materials and Methods

RyR1 Mutations. A pCI-neo vector (Promega) with a full-length RyR1 insert (GenBank accession no. X15209) was kindly provided by P. D. Allen (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston). To generate mutations in full-length RyR1, the NdeI (nucleotide 387) and NheI (nucleotide 1085) sites on the pCI-neo vector were destroyed, and unique silent EcoRV and NheI cloning sites were respectively introduced at nucleotide positions 9726 and 10014. KtoQ and ΔKtoR mutations described in the text were generated by three-step PCR (four primers and three reactions). The PCR products were subcloned into a pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen) and inserted into full length RyR1 by means of unique NheI and NdeI sites.

Recombinant Proteins. The glutathione S-transferase (GST)-his vector was generated by inserting six histidines in tandem into a pGEX-2T vector (Amersham Pharmacia) by PCR via unique BstBI and EcoRI sites. The GST-β1a-his vector was generated by inserting the β1a cDNA (GenBank accession no. NM_031173) into the GST-his vector via unique BamHI and EcoRI sites. Transformed BL21(DE3) bacterial cells were grown at 37°C and induced with 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were spun, resuspended in PBS containing 20 mM imidazole with protease inhibitors, and briefly sonicated on ice with a Branson Ultrasonics Sonifier 250 (Danbury, CT). Triton X-100 (Sigma) was adjusted to 1% at 4°C, and the suspension was centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was incubated with 0.5 ml Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for 1 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose beads were packed into a polyprep column (Bio-Rad), washed with PBS containing 20 mM imidazole, and eluted with 3 ml of PBS containing 250 mM imidazole. The eluate was combined with 1 ml of a 50% slurry of glutathione Sepharose (GS) 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia), incubated for 30 min at 4°C with gentle agitation, and washed with PBS. Sepharose beads covered with full length GST-β1a-his were then stored frozen.

In Vitro Translation and Pull-Down Assays. With exception of the RyR1 fragment I cDNA, all other RyR1 fragment cDNAs tested in Fig. 1 were generated by PCR with primers containing EcoRI–BamHI, EcoRI–NotI, BamHI–NotI, or NheI–NotI restriction sites. PCR products were inserted into a T7-driven pSG5 vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) via the unique restriction sites mentioned above. Fragment I cDNA was made by cutting the pCI-neo-RyR1 vector with XhoI, followed by self-ligation. Fragment G mutations tested in Fig. 2 were generated by PCR and inserted into the pCI-neo-RyR1 vector via EcoRV–NheI or NheI–NdeI sites. The 3201–3661 region bearing the mutation of interest was amplified by PCR and inserted into a T7-driven pSG5 vector via EcoRI and BamHI sites for in vitro translation. RyR1 protein fragments were generated in a TNT T7 reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) with the incorporation of [35S]methionine (Amersham Pharmacia) following the manufacturer's protocol. For pull-down of in vitro-transcribed RyR1 fragments, 100 μl of the GS beads/GST-β-his mixture (≈200 pmol of recombinant GST-β-his protein) were incubated with 30 μl of in vitro-translated RyR1 fragment (≈30 fmol) in 1 ml of binding buffer {50 mM Tris, pH 7.4/100 mM NaCl/1 mM MgCl2/0.1 mM DTT/0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS)} at 4°C for 15 h with agitation. Beads were washed extensively with binding buffer, mixed with 30 μl of SDS/PAGE loading buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 6.8/10% β-mercaptoethanol/4% SDS/0.2% bromophenol blue/20% glycerol), and boiled for 5 min. For autoradiograms, 15% SDS/PAGE gels were air-dried and exposed to Kodak X-Omat AR film (Eastman Kodak) for 4 h at -80°C. Rabbit skeletal muscle RyR1 was purified as described (24). For pull-down of purified RyR1, 100 μl of the GS beads/GST-β mixture was incubated with 200 μl of purified RyR1 (≈40 pmol) in 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM CaCl2, pCa5 and 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight. Beads were spun and washed extensively with the same buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with SDS/PAGE loading buffer and analyzed by 15% SDS/PAGE.

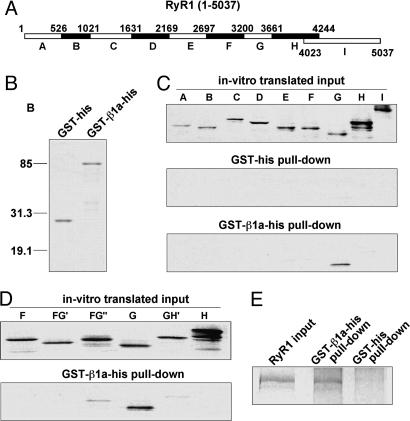

Fig. 1.

Mapping of DHPR β-binding to the G region (residues 3201–3661) of RyR1. (A) Library of RyR1 fragments used for mapping the β1a-binding region. A, 1–526; B, 527-1021; C, 1022–1631; D, 1632–2169; E, 2170–2697; F, 2698–3200; G, 3201–3661; H, 3662–4244; and I, 4023–5037. (B) Purified recombinant GST-his and GST-β1a-his proteins on a SDS/PAGE (15%) gel stained with Coomassie blue. (C) Autoradiograms of in vitro-translated RyR1 fragments, RyR1 fragments pulled down by GST-his protein, and RyR1 fragments pulled down by purified GST-β1a-his protein. (D) Autoradiograms of in vitro-translated overlapping fragments in the F through H regions (F, 2698–3200; FG′, 2894–3356; FG″, 3048–3508; G, 3201–3661; GH′, 3509–3969; and H, 3662–4244) and RyR1 fragments pulled down by purified GST-β1a-his protein. (E) Coomassie-blue stained SDS/PAGE shows pull-down of purified skeletal muscle tetrameric RyR1 with GS/GST-β1a-his beads.

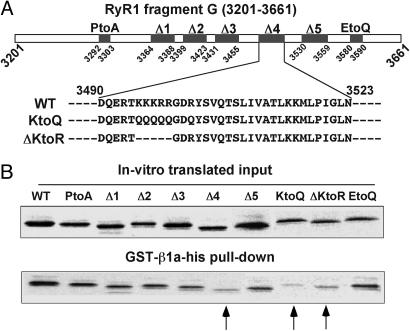

Fig. 2.

Charged residues in the 3490–3523 region of RyR1 diminish binding to DHPR β1a. (A) Mutations examined in fragment G are as follows. PtoA: P3292PPALPAGAPPP3303 to A3292AAAAAAAAAAA3303; Δ1: Δ(R3364–E3388); Δ2: Δ(S3399–W3423); Δ3: Δ(A3431–E3455); Δ4: Δ(D3490–N3523); Δ5: Δ(Q3530–L3559); KtoQ: K3495KKRRGDR3502 to Q3495QQQQGDQ3502; ΔKtoR: Δ(K3495–R3499); and EtoQ: P3580GREEDADDP3589 to A3580ARQQQAQQL3589.(B)(Upper) Autoradiogram of in vitro-translated fragment G mutants. (Lower) Fragment G mutants pulled down by GST-β1a-his. Arrows indicate Δ4, KtoQ, and ΔKtoR. The amount of KtoQ and ΔKtoR represent, respectively, 15% and 36% of the input, indicating an approximate 6.5- and 3-fold decrease of pull down efficiency compared to WT G fragment.

Primary Cultures and cDNA Transfection. Dyspedic mice founders were a gift of P. D. Allen. Primary cultures were prepared from enzyme-digested mouse hind limbs of dyspedic (RyR1 knockout) embryos as described (25). The RyR1 cDNA of interest and a separate expression vector encoding the T cell membrane antigen CD8 were mixed and cotransfected with the polyamine LT-1 (Panvera, Madison, WI). Whole-cell recordings were made 3–5 days after transfection. Cotransfected cells were recognized by incubation with CD8 antibody beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway).

Whole-Cell Voltage Clamp. Myotubes were whole-cell clamped with an Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) amplifier as described (19). The external solution was 130 mM tetraethylammonium-methanesulfonate, 10 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Hepes-tetraethylammonium(OH) (pH 7.4). The pipette solution was 140 mM Cs-aspartate, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EGTA (for Ca2+ transients) or 5 mM EGTA (for Ca2+ currents), and 10 mM 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid-CsOH (pH 7.2).

Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy. Cells were loaded with 4 μM fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 min at room temperature as described (19). Cells were viewed with an inverted Olympus microscope with a ×20 objective (numerical aperture = 0.4) and a Fluoview confocal attachment (Olympus). Excitation light was provided by a 5-mW argon laser attenuated to 6% with neutral density filters. Line scans images were taken at a speed of 2.05 ms per line (512 pixels per line) and integrated along the cell dimension to obtain the space-averaged time course of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ transient.

Curve Fitting. The voltage dependence of peak intracellular Ca2+ (ΔF/F), and Ca2+ conductance (G) was fit with the Boltzmann equation, A = [Amax]/[1 + exp((Vm - V1/2)/k)], where Amax is ΔF/Fmax or Gmax; Vm is the membrane potential; V1/2 is the potential at which A = Amax/2; and k is the slope factor. Ca2+ transient kinetics were analyzed at +30 mV (in the absence of Cd2+) by using transforms CBESPLN1.XFM and CBESPLN2.XFM in sigmaplot. These transforms take time and ΔF/F data sets with increasing ordered time values (in ms) and compute the cubic spline interpolation. The first and second derivatives of the spline also are computed.

Results

Prompted by structure–function studies linking the DHPR β1a-subunit to the mechanism of skeletal-type EC coupling (19), we searched for a binding site for β1a in RyR1. Recombinant β1a prebound to GS beads was used to pull-down in vitro-expressed [35S]methionine-labeled RyR1 fragments of ≈500 residues, which is a fragment size comparable to that of full-length β1a (Fig. 1 A). Recombinant GST-β1a-his fusion protein was purified on Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose and GS. The presence of GST and his tag on N terminus and C terminus of β1a, respectively, allowed the enrichment of full-length protein during purification. Purified GST-β1a-his fusion had the appropriate mobility on SDS/PAGE (Fig. 1B), and the estimated purity was >85% based on densitometry. Pull-downs were performed in a >1,000-fold molar excess of recombinant β protein relative to in vitro-translated RyR1 fragment. Saturation of the efficiency of the pull-down was confirmed by serial dilution of the GS/GST-β1a-his beads (data not shown). All RyR1 fragments, except H, were expressed essentially as single polypeptides with minor degradation (Fig. 1C). Fragments were incubated with purified GST-his or GST-β1a-his prebound to GS and pulled-down essentially as described (26). GST-β1a-his showed strong binding to RyR1 fragment G (M3201–W3661). Controls with GST-his lacking the insert indicated that pull-down did not occur in the absence of β1a. We further optimized the assay by testing several overlapping fragments in the F-G-H region (Fig. 1D). The results indicated that the 3201–3661 region covered by fragment G had the strongest binding and that the N- and C-terminal halves of the G region needed to be present in the same fragment for binding to occur, i.e., we found noticeably weak pull-down of fragment FG″ and GH' (Fig. 1D). To validate the pull-down experiments, the purified recombinant GST-β1a-his protein was subjected to several controls described elsewhere.§ S/GST-β1a-his beads efficiently pulled-down in vitro-translated α1S I–II loop (α1S G335–R432), the α1 domain that binds the β-subunit (27). In addition, a recombinant β1a lacking the so-called BID region required for I–II loop binding, namely β1a Δ(I278–Y287), was unable to pull-down the I–II loop, but interaction with fragment G was unaffected. Finally, Fig. 1E demonstrates the ability of GS/GST-β1a-his beads to efficiently pull-down RyR1 purified from rabbit skeletal muscle SR, demonstrating the ability of the recombinant fusion protein to interact with a RyR1 tetramer.

Residues of RyR1 with a high impact on β1a binding were identified by examining structural motifs in the G region (see Fig. 2 A). Fig. 2B shows that elimination of a polyproline stretch (P3292–P3303), a common binding partner for SH3 domains (28), or of an R3499G3500D3501 motif (data not shown), a common cell adhesion motif that binds to extracellular matrix protein integrins (29), did not affect the ability of GST-β1a-his to pull-down the mutated fragment G. We further tested deletions of 25 to 34 residues to eliminate predicted secondary structures. With this approach we found that deletion of residues D3490–N3523 (labeled 4), but not the flanking regions, significantly weakened β1a binding to fragment G. The most salient feature of the stretch eliminated by this deletion is a cluster of six positive charges, K3495KKRR _ _ R3502, concentrated near the N terminus of the deleted region. Fig. 2B shows that neutralization of the charges in the cluster (labeled KtoQ) or deletion of the first five charges (labeled ΔKtoR) significantly reduced the ability of the mutated fragment G to interact with β1a (see arrows in Fig. 2 and its legend for details).

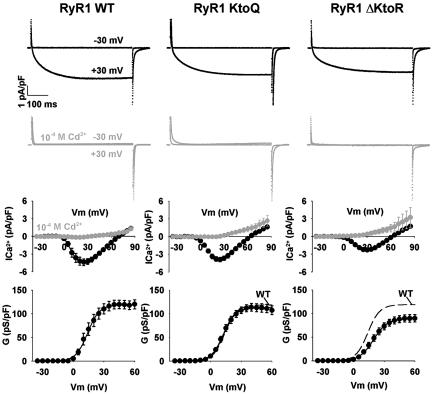

Mutations affecting β1a binding were introduced in an otherwise full-length RyR1, and the changes in the EC coupling phenotype were investigated by cDNA expression in dyspedic myotubes (30). DHPR Ca2+ current density depends on RyR1 expression via a mechanism that requires physical coupling of the RyR1 to the DHPR, the so-called retrograde coupling (30, 31). Hence, it was important to determine whether the RyR1 mutations affected Ca2+ current expression. We found that deletion of the 34 residues comprising region 4 (RyR1 ΔD3490–N3523) substantially reduced DHPR Ca2+ current expression (of 36 dyspedic myotubes expressing RyR1 ΔD3490–N3523, 11 did not rescue current, and 25 rescued small currents with mean Gmax of 62.5 pS/pF) preventing a clear analysis of the effect of this deletion on the depolarization-induced Ca2+ release, i.e., the orthograde coupling between DHPR and RyR1. For this reason large deletions were not pursued further. In contrast, the two mutations in the K3495KKRR _ _ R3502 motif that were shown to weaken β–RyR1 interaction preserved the expression of the DHPR Ca2+ current. Ca2+ currents expressed in the presence of WT RyR1 and RyR1 mutants with the neutralized (KtoQ) or deleted (ΔKtoR) cluster of charges are shown in Fig. 3. Ca2+ currents recovered by expression of either WT RyR1 or RyR1 KtoQ were typical of cultured skeletal myotubes (25) with a slow kinetics of activation, a peak current at approximately +30 mV, and a maximum density that was entirely normal. In RyR1 ΔKtoR-expressing cells, the slow kinetics of the Ca2+ current and the voltage dependence were preserved, but the maximum density decreased slightly (Student's t test significance P = 0.015). Kinetic analysis of the DHPR Ca2+ currents expressed in the presence of RyR1 KtoQ or RyR1 ΔKtoR shows that activation time constant of the fast component of the current was not significantly affected, whereas the activation time constant of the slow component was slightly but significantly increased: τslow, 68.2 ± 5.3 ms, 85.4 ± 4.5 ms (P = 0.024), and 95.7 ± 5.9 ms (P = 0.002) and τfast, 9.8 ± 1.1 ms, 11.5 ± 0.9 ms (P = 0.271), and 12.8 ± 1.2 ms (P = 0.085) for WT RyR1, RyR1 KtoQ, and RyR1 ΔKtoR, respectively. As indicated by the gray traces and symbols in Fig. 3, Ca2+ currents were effectively blocked by 0.1 mM Cd2+ added to the bath solution, consistent with previous reports (6, 12). These results show that neutralization and, to a lesser extent, deletion of the charges in the K3495KKRR _ _ R3502 cluster preserve DHPR–RyR1 retrograde coupling as manifested in DHPR Ca2+ current expression.

Fig. 3.

Ca2+ currents are weakly affected by mutations in RyR1 that diminish binding to DHPR β1a. Data from dyspedic myotubes transfected with RyR1 WT (Left), RyR1 KtoQ (Center), and RyR1 ΔKtoR (Right) are shown. In black are typical Ca2+ currents at -30 mV and +30 mV for a depolarization of 500 ms from a holding potential of -40 mV. In gray are Ca2+ currents in the same conditions with 10-4 M CdCl2 in the external solution. Ca2+ currents at the end of the depolarization are plotted as a function of voltage for the case of myotubes in external solution (black) and external solution with 10-4 M CdCl2 (gray). A Boltzmann fit of the voltage dependence of the Ca2+ conductance is shown by the black line in the bottom graphs. The segmented line repeats the fit of myotubes transfected with RyR1 WT for reference. The Boltzmann fit produced the following averages (mean ± SE) for Gmax in pS/pF units, V1/2 in mV, and k in mV, respectively: for RyR1 WT myotubes, 120.4 ± 9.3, 15.3 ± 1.7, and 4.8 ± 0.5 (n = 14); for RyR1 KtoQ myotubes, 114.8 ± 9.1, 9.2 ± 1.5, and 8.8 ± 1.5 (n = 11); and for RyR1 ΔKtoR myotubes, 89.1 ± 7.9, 19.7 ± 1.2, and 5.7 ± 0.2 (n = 20).

Ca2+ transients elicited by depolarization of myotubes expressing WT RyR1 and β-binding-deficient RyR1 are shown in Fig. 4. To determine SR Ca2+ content in transfected myotubes, we used the RyR1-specific agonist 4-chloro-m-cresol (4-CMC) (32). Cells were loaded with fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester, and SR Ca2+ release was induced by fast perfusion of external solution supplemented with 0.5 mM 4-CMC (Fig. 4A). The time course of the space-averaged confocal fluorescence intensity was computed from the line-scan image and is shown in ΔF/F units. The line diagrams mark the 4-s perfusion. A rapid increase in myotube fluorescence was observed in response to 4-CMC in RyR1-transfected but not in nontransfected myotubes (Fig. 4A, dotted trace). Histograms of the mean maximum fluorescence induced by 4-CMC are shown in Fig. 4B. We found that Ca2+ release responses to 4-CMC were similar in all cases, indicating that mutations in the K3495KKRR _ _ R3502 did not affect SR Ca2+ loading capacity of the myotubes. Fig. 4C shows Ca2+ transients elicited in RyR1 expressing myotubes under voltage clamp. The line diagrams mark the 50-ms depolarization. In WT RyR1-expressing cells, cytosolic Ca2+ increased more rapidly than those in mutant RyR1-expressing cells during the depolarization. The peak Ca2+ during the transient was maximum at large positive potentials, and the overall shape of the fluorescence vs. voltage curve was sigmoidal, rather than bell-shaped, in all cases (Fig. 4D), as expected for skeletal-type EC coupling. The main finding was that the KtoQ and ΔKtoR mutations significantly decrease the maximum amplitude of the Ca2+ transients (see Fig. 4 legend). A derivative analysis indicated that the maximum Ca2+ transient release rates of myotubes expressing KtoQ and ΔKtoR mutants were significantly slower than that expressing RyR1 WT (P < 0.001 for both cases, Fig. 4E). To confirm that the mutations preserved a bona fide skeletal-type Ca2+ release mechanism, experiments were repeated in external solution with 0.1 mM Cd2+ to block the Ca2+ current according to the results of Fig. 3. The results are shown in Fig. 4 C and D by the gray traces and symbols. As it can be seen, the amplitude of the Ca2+ transients and the voltage dependence of SR Ca2+ release were not changed. The results confirmed that depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients observed with KtoQ and ΔKtoR RyR1 mutants were independent of DHPR Ca2+ current and therefore corresponded to a skeletal type EC coupling mechanism.

Fig. 4.

Ca2+ transients are strongly affected by mutations in RyR1 that diminish binding to DHPR β1a. (A) The spatial integral of the confocal fluo-4 fluorescence after fast perfusion of a myotube with 0.5 mM 4-CMC present in external solution. The line diagrams with the square pulse indicate the time of perfusion (4 s). The dotted line in Left shows the time course of fluo-4 fluorescence in a nontransfected myotube perfused with the 4-CMC solution. (B) Histograms of the Ca2+ transients elicited by 4-CMC perfusion for nontransfected dyspedic myotubes (NT), and dyspedic myotubes transfected with WT RyR1 and RyR1 carrying the KtoQ and ΔKtoR mutations. The number of myotubes is indicated in brackets. The averages (mean ± SE) for peak fluorescence in ΔF/F unit are as follows: for NT myotubes, 0.40 ± 0.08 (n = 8); for RyR1 WT myotubes, 6.32 ± 0.87 (n = 22); for RyR1 KtoQ myotubes, 6.45 ± 0.53 (n = 31); and for RyR1 ΔKtoR myotubes, 6.34 ± 0.53 (n = 32). (C) Representative Ca2+ transient traces produced by depolarization to +30 mV from a holding potential of -40 mV, in the presence (gray) and absence (black) of 10-4 M CdCl2 in the external solution. The line diagrams with the square pulse indicate the duration of the depolarization (50 ms). Only part of the traces (100–250 ms) is shown. Note the pulses start from 110 ms. (D) Voltage dependence of the peak fluorescence in the presence (gray) and absence (black) of Cd2+. A Boltzmann fit produced the following averages (mean ± SE) values of ΔF/Fmax in ΔF/F units, V1/2 in mV, and k in mV, respectively: for RyR1 WT myotubes in external solution, 2.0 ± 0.2, 2.6 ± 1.5, and 6.4 ± 0.7 (n = 14); for RyR1 WT myotubes in external solution with Cd2+, 1.6 ± 0.2, 4.9 ± 1.1, and 6.6 ± 0.6 (n = 15); for RyR1 KtoQ myotubes in external solution, 1.1 ± 0.2, 11.7 ± 3.3, and 13.2 ± 1.6 (n = 13); for RyR1 KtoQ myotubes in external solution with Cd2+, 0.8 ± 0.1, 8.6 ± 3.9, and 10.0 ± 3.1 (n = 8); for RyR1 ΔKtoR myotubes in external solution, 1.0 ± 0.1, 19.0 ± 4.9, and 14.2 ± 2.4 (n = 10); and for RyR1 ΔKtoR myotubes in external solution with Cd2+, 1.1 ± 0.1, 17.3 ± 2.8, and 11.7 ± 1.1 (n = 11). (E) Histograms of the initial Ca2+ release rate in myotubes expressing RyR1 WT and mutants. The Ca2+ transient traces at +30 mV (in the absence of Cd2+) are analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. The histograms show the maximum first derivatives from 90 to 160 ms, with 2-ms interval for the interpolation. The number of myotubes is indicated in brackets. The averages (mean ± SE) values of the maximum Ca2+ transient release rate in Δ(ΔF/F)/ms unit are: for RyR1 WT myotubes, 0.099 ± 0.009 (n = 14); for RyR1 KtoQ myotubes, 0.046 ± 0.007 (n = 13); and for RyR1 ΔKtoR myotubes, 0.036 ± 0.006 (n = 10).

Discussion

In this study we investigated the interaction of RyR1 calcium channel with the DHPR β1a-subunit. We defined a unique domain of RyR1 encompassing the amino acids M3201 to W3661 as a β1a-subunit-binding domain. Neutralization or deletion of the charged amino acids within this RyR1 region induced a loss of interaction with the β1a-subunit. Expression in dyspedic myotubes of RyR1 mutants carrying the mutations or deletion of the β1a-subunit-binding domain led to the expression of DHPR Ca2+ currents similar in density and voltage dependence but with a slightly modified kinetics compared to the current recorded in the presence of WT RyR1. In contrast, both amplitude and rate constant of the depolarization-induced Ca2+ release were strongly reduced in myotubes expressing RyR1 KtoQ and RyR1 ΔKtoR. Therefore these results demonstrate that physical interaction between RyR1 and the β-subunit of the DHPR plays an important role in the orthograde coupling between the two channels.

The β-binding M3201–W3661 region of RyR1 was previously shown to house a calmodulin-binding domain (33) as well as a binding site for both a 20-mer fragment of the II–III loop known as domain A and the toxin maurocalcine (34). Based on the 3D reconstruction studies of RyR tetramer (33), this β-binding region lies between morphological regions 3 and 4 that form a “handle-like” structure connecting the surface of the foot structure to the transmembrane pore-forming domains buried in the SR membrane. The β-binding region may thus be critical for funneling signals into the channel proper. We suggest that the β1a-subunit when bound to region 3 and 4 may serve as a conduit for the conformational change transmitted to the RyR1 after DHPR charge movements.

Several studies have previously demonstrated the important role of the cytoplasmic II–III loop of the DHPR α1-subunit in the transmission of the information from the DHPR to the RyR1 (orthograde coupling) (2, 35). Therefore β1a may amplify molecular signals produced by the II–III loop elsewhere in the RyR1. Regardless of which of the two possibilities is more valid, i.e., whether β is a stand-alone signaling element or is part of the molecular cascade of the II–III loop, the results suggest that the vicinity of the DHPR β-binding site is a structurally sensitive part of the RyR1 channel and that the bulk of the EC coupling signal requires the interaction of β1a with RyR1.

Grabner et al. (5) have shown that the motif of the II–III loop required for orthograde signal leading to the opening of RyR1 channel also is required for retrograde signal allowing the control of the DHPR Ca2+ channel by RyR1. Interestingly, expression of RyR1 bearing KtoQ mutation in dipedic myotubes led to a normal density of DHPR Ca2+ current. Moreover, RyR1 KtoQ and RyR1 ΔKtoR remain sensitive to the agonist 4-CMC, and the SR of transfected myotubes retains the control of Ca2+ levels as determined by the in situ release assay. Hence the low-level activity of the expressed RyR1, when cells are at rest, does not appear to be compromised. Finally, DHPR charge movements were not found to be altered by the aforementioned RyR1 mutations indicating that surface trafficking of endogenous DHPR is not altered (data not shown), in agreement with the fact that the absence of RyR1 has only a small effect on DHPR charge movements (30, 31). These results strongly suggest that the β1a–RyR1 interaction described here is mostly involved in the orthograde signal process.

The proposed mechanisms of EC coupling have been influenced by models in which the outward movement of DHPR voltage sensors is coupled to Ca2+ release from the SR by mechanical torque exerted on the foot structure of RyR1 (36). A central role has been attributed to the α1S II–III loop in this mechanical coupling model. However, a molecular scenario in which the EC coupling signal is transmitted by single domain of the DHPR seems highly unlikely. The structural evidence, based on 3D reconstruction of the purified DHPR complex, indicates that the area of potential contact between a DHPR α1S/β1a/γ1/α2-δ heterotetramer and a juxtaposed RyR1 monomer, within the tetrameric foot structure, is exceedingly large (22, 23). Hence, the number of potential binding sites is large. The biochemical evidence indicates that the II–III loop, or sections thereof, interact with RyR1 sequences covered by fragments herein designated C (3), D (8), and/or the N-terminal third of G (34). Other RyR1-binding regions have been proposed for the III–IV loop (3) and the C-terminal domain of α1S (11). Even though the latters do not trigger EC coupling per se, a recent report indicates that cytoplasmic domains of α1S other than II–III loop affect the magnitude of the Ca2+ transients (12). The fact that part of the II–III loop may be anchored to the G region (34), where it could interact with β1a, may serve as a basis to understand the functional equivalence of the II–III loop and β1a and the nonlinearity of the EC coupling signaling system noticed previously (37). However, specific proposal on the hierarchy of the signals by the II–III loop, β1a, and other regions cannot be specified at this time. Signals generated in separate DHPR domains could converge onto a single RyR1 domain, or separate DHPR domains could activate separate RyR1 domains. The biochemical and structural data, taken together with the present data, suggest that many DHPR domains appear to be physically docked to RyR1, and that at least two of them, namely the α1S II–III loop and β1a, might be responsible for transmission of the EC coupling signal to RyR1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR46448), the European Commission (HPRN-CT-2002–00331), Association Française contre les Myopathies, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique, and Université Joseph Fourier. X.A. is recipient of a fellowship from the European Commission.

Author contributions: W.C., X.A., M.R., and R.C. designed research; W.C., X.A., and M.R. performed research; W.C. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; W.C., X.A., M.R., and R.C. analyzed data; and W.C., X.A., M.R., and R.C. wrote the paper.

Part of this data has been presented previously in abstract form [Cheng, W., Carbonneau, L., Sheridan, D., Keys, L., Altafaj, X., Ronjat, M. & Coronado, R. (2004) Biophys. J. 86, 220a (abstr.)].

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: DHPR, dihydropyridine receptor; RyR1, ryanodine receptor type 1; EC, excitation-contraction; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; GS, glutathione Sepharose; 4-CMC, 4-chloro-m-cresol.

Footnotes

Cheng, W., Carbonneau, L., Sheridan, D., Keys, L., Altafaj, X., Ronjat, M. & Coronado, R. (2004) Biophys. J. 86, 220a (abstr.).

References

- 1.Flucher, B. E. & Franzini-Armstrong, C. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 8101-8106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakai, J., Tanabe, T., Konno, T., Adams, B. & Beam, K. G. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 24983-24986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leong, P. & Maclennan, D. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29958-29964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saiki, Y., El-Hayek, R. & Ikemoto, N. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 7825-7832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grabner, M., Dirksen, R. T., Suda, N. & Beam, K. G. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21913-21919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkens, C. M., Kasielke, N., Flucher, B. E., Beam, K. G. & Grabner, M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5892-5897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahern, C. A., Bhattacharya, D., Mortenson, L. & Coronado, R. (2001) Biophys. J. 81, 3294-3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proenza, C., O'Brien, J., Nakai, J., Mukherjee, S., Allen, P. D. & Beam, K. G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6530-6535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Reilly, F., Robert, M., Jona, I., Szegedi, C., Albrieux, M., Geib, S., De Waard, M., Villaz, M. & Ronjat, M. (2002) Biophys. J. 82, 145-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takekura, H., Paolini, C., Franzini-Armstrong, C., Kugler, G., Grabner, M. & Flucher, B. E. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 5408-5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sencer, S., Papineni, R. V., Halling, D. B., Pate, P., Krol, J., Zhang, J. Z. & Hamilton, S. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38237-38241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbonneau, L., Bhattacharya, D., Sheridan, D. C. & Coronado, R. (2005) Biophys. J. 89, 243-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birnbaumer, L., Qin, N., Olcese, R., Tareilus, E., Platano, D., Constantin, J. & Stefani, E. (1998) J. Bionenerg. Biomembr. 30, 357-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao, T., Chien, A. J. & Hosey, M. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2137-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bichet, D., Cornet, V., Geib, S., Carlier, E., Volsen, S., Hoshi, T., Mori, Y. & De Waard, M. (2000) Neuron 25, 177-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neely, A., Garcia-Olivares, J., Voswinkel, S., Horstkott, H. & Hidalgo, P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21689-21694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregg, R. G., Messing, A., Strube, C., Beurg, M., Moss, R., Behan, M., Sukhareva, M., Haynes, S., Powell, J. A., Coronado, R. & Powers, P. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 13961-13966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuhuber, B., Gerster, U., Döring, F., Glossmann, H., Tanabe, T. & Flucher, B. E. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5015-5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheridan, D. C., Cheng, W., Carbonneau, L., Ahern, C. A. & Coronado, R. (2004) Biophys. J. 87, 929-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opatowsky, Y., Chen, C. C., Campbell, K. P. & Hirsch, J. A. (2004) Neuron 42, 387-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Petergem, F., Clark, K. A., Chatelain, F. C. & Minor, D. L., Jr. (2004) Nature 429, 671-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serysheva, I. I., Ludtke, S. J., Backer, M. R., Chui, W. & Hamilton, S. L. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10370-10375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf, M., Eberhart, A., Glossmann, H., Striessnig, J. & Grigorieff, N. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 332, 171-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai, F. A., Erickson, H. P., Rousseau, E., Liu, Q. Y. & Meissner, G. (1988) Nature 331, 315-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beurg, M., Sukhareva, M., Strube, C., Powers, P. A., Gregg, R. G. & Coronado, R. (1997) Biophys. J. 73, 807-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker, D., Bichet, D., Campbell, K. P. & De Waard, M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2361-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pragnell, M., De Waard, M., Mori, Y., Tanabe, T., Snutch, T. P. & Campbell, K. P. (1994) Nature 368, 67-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kay, B. K., Williamson, M. P. & Sudol, M. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 231-241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruoslahti, E. & Pierschbacher, M. D. (1986) Cell 44, 517-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakai, J., Dirksen, R. T., Nguyen, H. T., Pessah, I. N., Beam, K. G. & Allen, P. D. (1996) Nature 380, 72-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avila, G. & Dirksen, R. T. (2000) J. Gen. Physiol. 115, 467-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fessenden, J. D., Wang, Y., Moore, R. A., Chen, S. R., Allen, P. D. & Pessah, I. N. (2000) Biophys. J. 79, 2509-2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samso, M. & Wagenknecht, T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1349-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altafaj, X., Cheng, W., Esteve, E., Urbanie, J., Grunwald, D., Sabatier, J. M., Coronado, R., De Waard, M. & Ronjat, M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4013-4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanabe, T., Beam, K. G., Adams, B. A., Niidome, T. & Numa, S. (1990) Nature 346, 567-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rios, E., Karhanek, M., Ma, J. & Gonzalez, A. (1993) J. Gen. Physiol. 102, 449-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coronado, R., Ahern, C. A., Sheridan, D. C., Cheng, W., Carbonneau, L. & Bhattacharya, D. (2004) Basic Appl. Myol. 14, 291-298. [Google Scholar]