Abstract

For skin gene therapy, introduction of a desired gene into keratinocyte progenitor or stem cells could overcome the problem of achieving persistent gene expression in a significant percentage of keratinocytes. Although keratinocyte stem cells have not yet been completely characterized and purified for gene targeting purposes, lentiviral vectors may be superior to retroviral vectors at gene introduction into these stem cells, which are believed to divide and cycle slowly. Our initial in vitro studies demonstrate that lentiviral vectors are able to efficiently transduce nondividing keratinocytes, unlike retroviral vectors, and do not require the lentiviral accessory genes for keratinocyte transduction. When lentiviral vectors expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) were directly injected into the dermis of human skin grafted onto immunocompromised mice, transduction of dividing basal and nondividing suprabasal keratinocytes could be demonstrated, which was not the case when control retroviral vectors were used. However, flow cytometry analysis demonstrated low transduction efficiency, and histological analysis at later time points provided no evidence for progenitor cell targeting. In an alternative in vivo method, human keratinocytes were transduced in tissue culture (ex vivo) with either lentiviral or retroviral vectors and grafted as skin equivalents onto immunocompromised mice. GFP expression was analyzed in these human skin grafts after several cycles of epidermal turnover, and both the lentiviral and retroviral vector-transduced grafts had similar percentages of GFP-expressing keratinocytes. This ex vivo grafting study provides a good in vivo assessment of gene introduction into progenitor cells and suggests that lentiviral vectors are not necessarily superior to retroviral vectors at introducing genes into keratinocyte progenitor cells during in vitro culture.

Achieving persistent and high-level gene expression in a significant percentage of target cells is important for establishing successful clinical applications of gene therapy. For gene therapy of the skin, a renewable tissue undergoing constant turnover, and for achieving long-term expression in a significant percentage of keratinocytes, gene targeting to keratinocyte stem cells (KSC) or long-lasting keratinocyte progenitor cells will be required (36). In ex vivo skin gene therapy, keratinocytes are removed from the donor and transduced with retroviral vectors in vitro without selectively targeting KSC. The genetically modified keratinocytes can then be grafted back onto the donor. Even though progress in skin gene therapy has enabled gene expression from retroviral vectors to be detected for sustained periods in grafted keratinocytes (9, 24, 32, 56), transgene expression in vivo is frequently decreased over time, either in the duration of expression or in the percentage of keratinocytes expressing the gene (12, 14, 18, 35, 50). The factors contributing to this decreased expression may be similar to those for other tissues (14, 27, 41, 51) and may include inefficient introduction of transgenes into KSC during ex vivo culture and “silencing” of the integrated retroviral vector after grafting (4, 8; S. Eden, T. Hashimshony, I. Keshet, H. Cedar, and A. Thorne, Letter, Nature 394:842, 1998).

The epidermis is a renewable tissue composed of a proliferating basal layer, which is believed to contain KSC, and a suprabasal layer above the dividing layer, which is composed of nondividing keratinocytes undergoing progressive differentiation. KSC exist as slowly cycling cells in the hair follicles and basal layers of the epidermis in vivo (10, 11, 15, 28, 29, 31, 55) and are the progenitor cells for both the hair follicle and epidermis (30, 39). There is also evidence that KSC can be passaged in tissue culture and that they are subsequently present in skin grafts (1, 2, 24, 44). However, we lack unique cell surface markers for KSC identification, and the efficiency of gene introduction into KSC during keratinocyte culture is difficult to determine. Additionally, for efficient chromosomal integration, retroviral vectors require the loss of the nuclear membrane that occurs during mitosis (33, 49), and slowly dividing KSC may be much more difficult to target in tissue culture by retroviral vectors than the population of rapidly proliferating keratinocytes.

Lentiviral vectors are a promising new tool that, unlike retroviral vectors, have the unique ability to target desired genes and integrate them into quiescent, nonproliferating cells (37, 38, 47), since the viral preintegration complex can be transported through an intact nuclear membrane via the nucleopore. Lentiviral vectors have demonstrated efficient delivery and integration and stable expression of genes in nondividing cells, such as hematopoietic stem cells, neurons, and liver and muscle cells, both in vitro and in vivo (5, 7, 13, 22, 34, 37, 38, 47, 52–54). Consequently, lentiviral vectors may be superior to retroviral vectors in transducing the KSC subset during ex vivo culture and following direct in vivo injection into the skin. More recently, several studies have argued that cell cycle status is important for transduction of nondividing cells by lentiviral vectors, with efficient transduction requiring activation and entry into the cell cycle (G1) (3, 25, 43, 52). Nondividing cells that are quiescent in the G0 state have significantly lower efficiency of transduction by lentiviral vectors.

Here, we characterize the ability of lentiviral vectors to introduce genes into nondividing keratinocytes and, after optimization of lentiviral transduction, we determine if lentiviral vectors are superior to retroviral vectors at targeting the KSC subset in tissue culture. Since a unique specific marker for KSC is not yet available, the best method to assess KSC targeting is an in vivo assay of grafted skin equivalents or artificial skin that contains transduced keratinocytes (48). Human keratinocytes transduced with either lentiviral vectors or retroviral vectors expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) are grafted onto immunocompromised mice, and the percentage of human keratinocytes expressing GFP can be quantitatively assessed following many complete cycles of keratinocyte loss and replacement in the epidermis. In a renewable tissue, the percentage of keratinocytes expressing GFP after several cycles of epidermal turnover should correlate directly with the percentage of KSC or early progenitor cells transduced with the GFP gene. We also characterize the ability of lentiviral vectors to introduce genes into nondividing keratinocytes, including the slowly dividing basal KSC and the postmitotic suprabasal keratinocytes, following direct in vivo injection into the skin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vector production.

Lentiviral vectors that express GFP driven by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter were produced by transient transfection of the following plasmids into 293T cells: a packaging plasmid (pCMV8.2 or pCMV8.9, which contain different accessory genes), an envelope plasmid (MLV ampho or vesicular stomatitis virus G protein [VSV-G]), and the transducing vector pHR′CMV-GFP. Using the calcium phosphate transfection technique, 20 μg of DNA per 60-mm-diameter petri dish (7.5 μg of pCMV8.2 or pCMV8.9, 2.5 μg of env, and 10 μg of pHR′CMV-GFP) was used. After 48 and 72 h, we harvested the viral supernatant (SN), filtered the conditioned medium through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters, and used the SN either fresh or as frozen aliquots. The production of the Moloney murine leukemia virus-based control retrovirus pGC-GFP-loxP (kindly provided by O. Wildner, Clinical Gene Therapy Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health; GFP expression is driven by the retroviral long terminal repeat) was as previously described (57). For most experiments, lentiviral vectors were pseudotyped with both amphotropic and VSV-G envelopes, while retroviral vectors were pseudotyped with amphotropic envelope proteins.

Transduction of 293T cells and primary human foreskin keratinocytes and determination of virus vector titer.

A total of 105 293T cells per well or 4 × 104 human keratinocytes per well were transduced in a six-well plate with 1 ml of the viral SN in the presence of 8 μg of Polybrene/ml. After 4 h, the SN was replaced by fresh culture medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium [DMEM] plus 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS]for 293T cells; serum-free medium plus supplements for human keratinocytes). Seventy-two hours posttransduction, the cells were trypsinized and measured by FACScan analysis. Vector stock was considered helper free when no GFP+ cells were detected following repeated incubation of target cells with conditioned medium of transduced cells. In addition, culture medium of transduced cells after repeated splittings was checked for the presence of p24Gag protein to prove the absence of replicating virus.

To determine the specific titer of every new batch of virus vectors, serial dilutions of viral SN were used for transduction of either 293T cells or primary human keratinocytes. The transduction experiments were performed in six-well plates using 105 293T cells or 4 × 10 4 human keratinocytes per well and 1 ml of the SN dilution per well. Following transduction, GFP expression or fluorescence was measured directly by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis without any fixation; paraformaldehyde fixation (5 min; 2%, on ice) was performed only if further phenotyping of the transduced cells was required. The titer was determined to be the greatest SN dilution at which GFP-positive cells were still present, relative to a control well of untransduced cells (titer/ml). Typical titers for the lentiviral vectors were between 1 × 105 and 5 × 106 and between 1 × 107 and 5 × 108 after ultracentrifugation to concentrate the virus vectors, independent of the envelope pseudotype of the lentiviral vector (see below). For experiments, the viral SN was used immediately for experiments and not frozen, with precise titers subsequently determined. The titers of the control retroviral vector, pGC-GFP-loxP, were approximately 106. To obtain higher titers, lentiviral vector SN was ultracentrifuged at 50,000 × g for 90 min. Ultracentrifugation increased the titers of the VSV-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors by approximately 2 log units on average. Amphotropic-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors were also concentrated by ultracentrifugation, confirming recently published data that demonstrate that amphotropic envelopes are stable enough for high-speed ultracentrifugation and concentration (46). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for p24Gag protein (Beckman-Coulter) were used to determine the concentrations of viral p24Gag protein in the different viral SNs. For all transduction experiments comparing lentiviral and retroviral vectors, comparable virus titers were used.

Preparation and culture of human keratinocytes (and fibroblasts).

Single-cell suspensions of keratinocytes were prepared from human foreskin samples, foreskin grafts, and organotypic skin equivalents. Keratinocytes were obtained from samples by overnight treatment with dispase (Becton Dickinson Labware, Bedford, Mass.) at 4°C and subsequent enzymatic digestion of the separated and retained epidermal sheet with 0.05% trypsin-0.53 mM EDTA (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) at 37°C for 20 min. The dermis was minced and placed in a medium-size petri dish in DMEM-10% FBS to allow primary human fibroblasts to migrate out of the tissue. Keratinocytes were grown in serum-free medium supplemented with epidermal growth factor (0.15 ng/ml) and bovine pituitary extract (25 μg/ml) (all obtained from Gibco BRL) at a concentration of 4 × 104 cells per well in a six-well plate, and fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM-5% FBS (21, 45). Keratinocyte suspensions were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to analysis by FACScan.

FACS analysis.

Transduced cells (293T cells or human keratinocytes) were trypsinized, resuspended in 5 ml of culture medium, and washed in PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+. After being washed, the cells were diluted in PBS to a concentration of 106/ml. FACS analysis (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson) for cellular GFP and propidium iodide incorporation was performed with the CellQuest program (version 3.0.1f; Becton Dickinson). To distinguish human keratinocytes from mouse keratinocytes in biopsies of human foreskins grafted onto mice, keratinocyte suspensions were stained with an anti-human HLA-A, -B, -C monoclonal antibody conjugated to R-phycoerythrin (Pharmingen) and analyzed by FACS.

Direct in vivo injection of lentiviral vectors into grafted human foreskins.

Human foreskins were grafted onto nude mice and allowed to stabilize for 6 to 8 weeks. Subsequently, concentrated high-titer lentiviral vectors were intradermally injected into the foreskin grafts. After 2 to 10 days, the grafts were removed for FACS analysis or immunohistochemistry analysis for GFP expression (see below). Epidermal cell suspensions for FACS analysis were prepared as described above.

Production of skin equivalents or raft cultures from transduced human keratinocytes.

Human foreskin keratinocytes were transduced with either the pΔ8.9 lentiviral vector or the pGC-GFP-loxP retroviral vector in vitro at comparable transduction efficiencies. After expansion in culture for 7 days, keratinocytes were collected and analyzed for GFP expression by FACScan and adjusted so that GFP expression was present in approximately 50% of the grafted keratinocytes.

Organotypic raft cultures were constructed by seeding 5 × 105 of the transduced keratinocytes onto a collagen matrix containing 75,000 human fibroblasts (16, 42) and maintaining the rafts at the air-liquid interface for 3 days until grafting was performed. Grafting was performed on 4- to 5-week-old NIH male Swiss nu/nu mice (Taconic Farms). All animals were housed and used in accordance with institutional guidelines. A full-thickness, circular, 12- to 14-mm-diameter wound was created on the upper back of each mouse. Organotypic raft cultures were trimmed to be slightly smaller than the wounds (diameter, about 1.1 mm) and placed on the muscle fascia in correct anatomical orientation. The grafts were covered with sterile petrolatum gauze (Sherwood Medical, St. Louis, Mo.) and secured with a tape dressing (0.75 by 3 in.; Baxter Diagnostics, Deerfield, Ill.). The dressing was changed at 1 week and removed after 2 weeks. At different time points, pictures of the grafts were taken using a digital camera (Coolpix 990; Nikon). The grafts of human keratinocytes were removed by wide excision after 8 and 13 weeks and analyzed for GFP expression, either after preparing single-cell suspensions in FACS or by immunohistological methods (described below).

Immunohistochemical staining of human foreskin grafts and organotypic cultures.

Human foreskin grafts and/or organotypic raft cultures were excised from nude mice and fixed in 10% formalin. After being embedded in paraffin and sectioned, skin samples were stained with a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (JL-8; Clontech) (1:2,000) for 1 h at room temperature. For detection of the primary antibody, we used a detection kit (SK 5200) from Vector Laboratories which uses a biotinylated secondary antibody and alkaline phosphatase as the enzyme. All staining steps and the substrate incubation were performed at room temperature for 30 min each time. Control samples were stained with isotype control antibody from Pharmingen (final concentration, 0.5 μg/ml; catalog number 03181D)

RESULTS

Lentiviral vectors do not require accessory genes for efficient keratinocyte transduction.

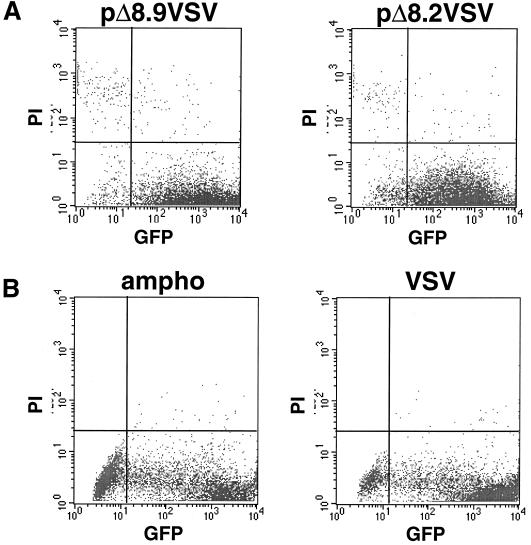

To determine the optimal experimental conditions for lentiviral vector transduction of both proliferating and nondividing primary human keratinocytes, we first examined the importance of the four lentiviral accessory genes vif, vpr, vpu, and nef for keratinocyte transduction. Lentiviral vectors that express GFP driven by a CMV promoter were produced with packaging plasmids that either express the vif, vpr, vpu, and nef accessory genes (pΔ8.2) or lack these accessory genes (pΔ8.9) (58). When pΔ8.2 and pΔ8.9 were used to transduce primary human keratinocytes (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 25; range, 2.5 to 25), quantitative FACS analysis demonstrated that both lentiviral vectors reproducibly transduced and expressed GFP in up to 90% of proliferating primary human keratinocytes 72 h after transduction (Fig. 1A, lower right quadrant). These data suggest that lentiviral accessory genes are not required for efficient transduction of proliferating primary human keratinocytes.

FIG. 1.

(A) FACS analysis demonstrating equivalent percentages of keratinocytes expressing GFP (approximately 90% in lower right quadrant) following transduction by lentiviral vectors that either contain (pΔ8.2) or lack (pΔ8.9) accessory genes and are pseudotyped with VSV-G envelope proteins in this experiment. (B) Percentages of keratinocytes expressing GFP following transduction by lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with either amphotropic (91%; range, 75 to 97%) or VSV-G (93%; range, 67 to 94%) envelope proteins. Propidium iodide (PI) was used to gate for living cells. The results are representative of numerous experiments.

Lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with either amphotropic or VSV-G envelope proteins efficiently transduce keratinocytes.

To assess how different envelope proteins influence the transduction efficiency of human keratinocytes, lentiviral vectors produced with the pΔ8.9 packaging plasmid (lacking lentiviral accessory genes), were pseudotyped with the amphotropic Moloney murine leukemia virus envelope, a commonly used envelope protein for retrovirus vectors, and the VSV-G envelope, which confers a high degree of stability on viral particles (6, 40). Both amphotropic- and VSV-G-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors (MOI, 25) achieved equivalent efficiencies of transduction of primary human keratinocytes: 91% (range, 75 to 97%) for amphotropic pseudotypes and 93% (range, 67 to 94%) for VSV-G pseudotypes (Fig. 1B, lower right quadrants). Higher lentivirus titers obtained by ultracentrifugation increased the transduction efficiency up to 99% (data not shown). Therefore, amphotropic- and VSV-G-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors have comparable abilities to transduce primary human keratinocytes.

Lentiviral vectors are superior to retroviral vectors in transducing nondividing or slowly dividing human keratinocytes.

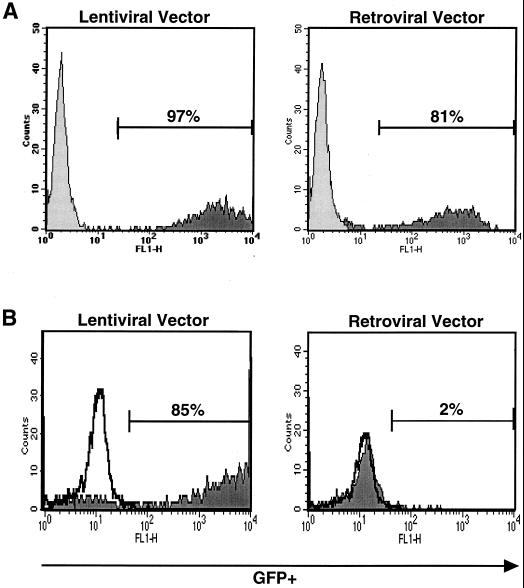

We next determined how well lentiviral vectors transduce both proliferating and nondividing keratinocytes compared to retroviral vectors. Both the pΔ8.9 lentiviral and the pGC-GFP-loxP retroviral vectors (MOI, 25), pseudotyped with amphotropic (or VSV-G) envelope proteins, were able to transduce proliferating primary human keratinocytes with comparable transduction efficiencies greater than 70% at 72 h posttransduction (Fig. 2A). A higher average level of GFP expression per transduced keratinocyte is seen in keratinocytes transduced with the Δ8.9 lentiviral vector (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI], >103) than in those transduced with the pGC-GFP-loxP retroviral vector (MFI <103), which may be due to higher GFP expression from the internal CMV promoter in the lentiviral vector.

FIG. 2.

(A) FACS analysis demonstrating percentages of proliferating human keratinocytes expressing GFP following transduction with either lentivirus (pΔ8.9) or retrovirus (pGC-GFP-loxP). (B) Percentages of gamma-irradiated and nondividing human keratinocytes expressing GFP following transduction. The x axis measures GFP expression, and the y axis measures cell numbers. All gated keratinocytes were propidium iodide negative (living). All results shown are representative of at least four experiments.

In order to compare the abilities of lentiviral vectors and retroviral vectors to introduce genes into nondividing primary human keratinocytes in culture, gamma irradiation (2,000 to 3,000 rads) was utilized to block keratinocyte proliferation. In contrast to the retroviral vectors, which were unable to transduce nonproliferating keratinocytes (transduction efficiency, less than 2%), pΔ8.9 lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with either amphotropic or VSV-G envelopes were able to efficiently transduce approximately 85% of gamma-irradiated nonproliferating keratinocytes (Fig. 2B). Additionally, lentiviral accessory proteins were not required for efficient transduction of nondividing keratinocytes. These in vitro data suggest that lentiviral vectors might be superior to retroviral vectors at transducing nondividing keratinocytes in the skin following direct injection and, importantly, may be superior to retroviruses at introducing genes into slowly dividing keratinocyte progenitor cells during in vitro tissue culture.

Lentiviral vectors can transduce nondividing keratinocytes following direct in vivo introduction into the skin.

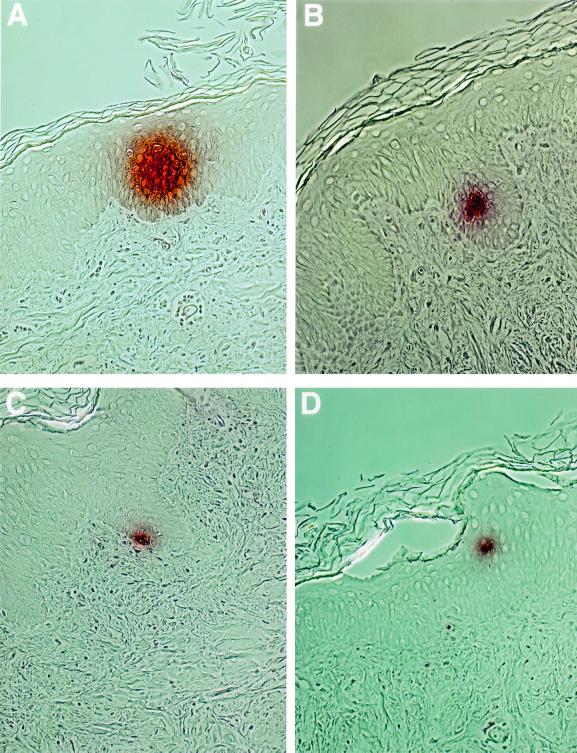

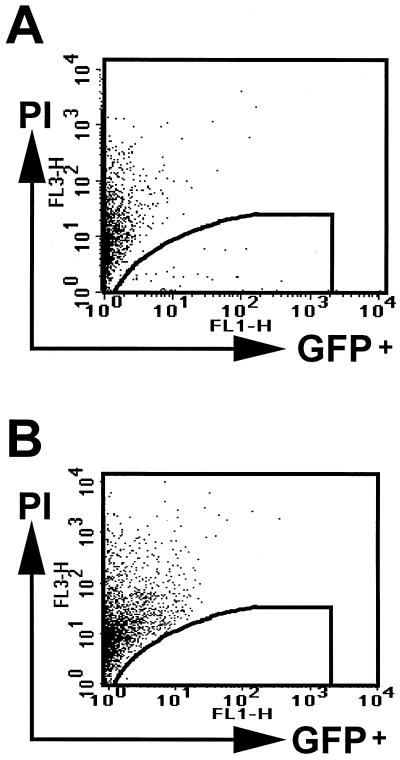

To assess lentiviral vector transduction of human keratinocytes in vivo, human foreskins were grafted onto immunocompromised mice, and pΔ8.9 lentiviral vectors were injected intradermally into the human skin grafts (107 infectious lentiviral particles per graft [range, 105 to 107]). Biopsy specimens were taken at different time points following injection (2 to 10 days) and assessed for GFP expression by immunohistochemistry and FACS analysis. Vertical histology sections demonstrated scattered areas of GFP expression in the human epidermal keratinocytes at 2 days post-intradermal injection (Fig. 3). Interestingly, most of the GFP expression was detected in the differentiating suprabasal keratinocytes, which are nondividing (Fig. 3A, B, and D), and not in the proliferating basal layer (Fig. 3C). GFP expression was also noted in cells present in the dermis, such as fibroblasts (data not shown). Gene expression could not be detected histologically in the epidermis following direct injection of retroviral vectors. FACS analysis performed on epidermal cell suspensions demonstrated quantitatively that a very low percentage (less than 1%) of human keratinocytes were expressing GFP following direct injection of lentiviral vectors (Fig. 4). Because a very low percentage of keratinocytes expressed GFP, a precise time course was difficult to determine, although no GFP expression was detected in the day 10 biopsies. Lentiviral accessory genes do not increase transduction efficiency, since pΔ8.2 lentiviral vectors also transduced less than 1% of human keratinocytes following intradermal injection. Although it is possible that some proliferating keratinocytes were transduced in the basal layer and subsequently moved into the suprabasal layer during the experiment, these results suggest that lentiviral vectors can transduce and express genes in a small percentage of nondividing or postmitotic keratinocytes following direct in vivo injection.

FIG. 3.

GFP expression demonstrated immunohistochemically in keratinocytes of human skin grafts. Human skin was grafted onto immunocompromised mice, injected intradermally with pΔ8.9 lentiviral vectors, and removed after 2 days for analysis. (A, B, and D) GFP expression in suprabasal keratinocytes; (C) GFP expression in a basal keratinocyte (magnification, ×400). Isotype controls were negative for GFP expression.

FIG. 4.

(A) FACS analysis demonstrating percentages of keratinocytes (0.5% in enclosed area) expressing GFP following direct intradermal injection of pΔ8.9 lentiviral vectors. Human skin was grafted onto immunocompromised mice, injected intradermally, and removed 2 days later for analysis. (B) Control injections of PBS have no detectable GFP expression. The x axis measures GFP expression, and the y axis measures propidium iodide (PI) uptake. The results shown are representative of numerous experiments.

Lentiviral vectors are not superior to retroviral vectors at transducing keratinocyte progenitor cells during ex vivo tissue culture.

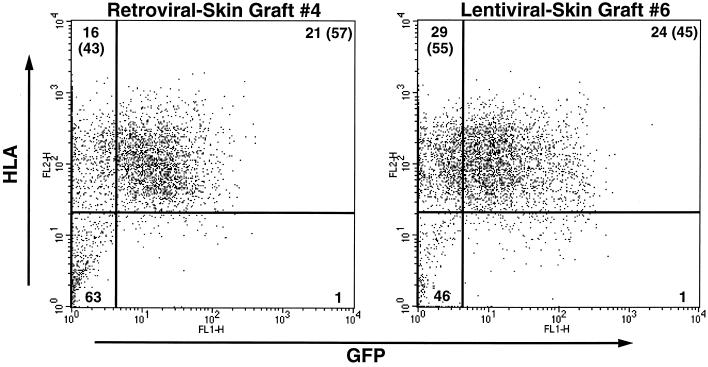

In order to assess lentiviral vector transduction of keratinocyte progenitor cells during ex vivo culture, human keratinocytes were transduced with either lentiviral or retroviral vectors while growing in tissue culture, were incorporated into skin equivalents (or artificial skin), and were grafted onto immunocompromised mice (24, 45, 48). In our ex vivo model, the grafted human keratinocytes would be expected to completely turn over every 2 to 3 weeks, and all genetically engineered keratinocytes would be lost unless progenitor cells were stably transduced (17, 19, 20, 48). Therefore, the ability of lentiviral vectors (or retroviral vectors) to introduce genes into keratinocyte progenitor cells can be determined by the percentage of human keratinocytes expressing GFP after several epidermal turnovers, analogous to biological models assessing hematopoietic stem cell targeting (7, 13, 34, 52–54). Human skin equivalents were prepared for grafting with keratinocytes transduced with either pΔ8.9 lentiviral vectors or pGC-GFP-loxP retroviral vectors and adjusted so that approximately 55% of the grafted keratinocytes in each group expressed GFP (data not shown). The transduced human skin grafts removed from the mice at 8 weeks (three to four epidermal turnovers) demonstrated, somewhat surprisingly, that keratinocytes transduced with pΔ8.9 lentiviral vectors (n = 2) and pGC-GFP-loxP retroviral vectors (n = 2) had comparable average percentages of GFP-expressing human (HLA+) keratinocytes (41% for pΔ8.9 and 45% for pGC-GFP-loxP) (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Furthermore, at 13 weeks postgrafting (four to six epidermal turnovers), comparable percentages of human keratinocytes continued to express GFP in grafts transduced with either pΔ8.9 lentiviral vectors (n = 2) or pGC-GFP-loxP retroviral vectors (n = 3) (Fig. 5 and Table 1). At this later time point, two grafts transduced by retroviral vectors experienced graft failure accompanied by a significant loss of human keratinocytes and scarring, and they are difficult to interpret accurately. These in vivo grafting assays do not support the hypothesis that lentiviral vectors are superior to retroviral vectors in transducing keratinocyte progenitor cells during ex vivo culture.

FIG. 5.

FACS analysis demonstrating percentages of human keratinocytes expressing GFP (upper right quadrants) in human skin equivalents at 13 weeks postgrafting. Human skin equivalents that had been transduced with either lentiviral or retroviral vectors were grafted onto immunocompromised mice, removed by wide excision at 8 and 13 weeks postgrafting, and assayed for GFP expression in human keratinocytes. The x axis measures GFP expression, and the y axis measures human HLA expression in order to distinguish human from murine keratinocytes. Isotype antibody controls are not shown. The percentages of cells in each quadrant are indicated. The numbers in parentheses indicate the percentages of human keratinocytes that are GFP+ or GFP−. See Table 1 for a summary of the data.

TABLE 1.

GFP expression in human keratinocytesa

| Skin graft type and no. | 8 wks

|

13 wks

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % HLA+ | % GFP+ | % HLA+ | % GFP+ | |

| Lentiviral vector | ||||

| 4 | 37 | 40 | ||

| 9 | 17 | 41 | ||

| 5 | 56 | 39 | ||

| 6 | 54 | 45 | ||

| Retroviral vector | ||||

| 1 | 46 | 29 | ||

| 3 | 40 | 60 | ||

| 4 | 38 | 57 | ||

| 2b | 12 | 7 | ||

| 5b | 12 | 5 | ||

Summary of quantitative FACS analysis demonstrating the percentages of human keratinocytes expressing GFP in human skin equivalents at 8 and 13 weeks postgrafting. Human skin equivalents that had been transduced with either lentiviral or retroviral vectors were grafted onto immunocompromised mice, removed by wide excision at 8 and 13 weeks postgrafting, and assayed for GFP expression in human keratinocytes. HLA+ indicates the percentage of human keratinocytes present in cell suspensions prepared from the grafts, and GFP+ indicates the percentage of human keratinocytes expressing GFP.

Two grafts had graft failure with significant loss of keratinocytes and scar formation.

DISCUSSION

Since human skin is a renewable tissue that undergoes loss and replacement of all keratinocytes approximately every 21 days or less in the wound-like environment of a skin graft (17, 20, 48), successful skin gene therapy requires gene targeting to keratinocyte progenitor cells for persistent expression in a high percentage of keratinocytes. These studies represent the first comprehensive assessment of keratinocyte transduction by lentiviral vectors and also demonstrate the advantages of using grafts of human skin equivalents as an in vivo assay to assess the ex vivo transduction of keratinocyte progenitor cells. We present in vitro data showing that lentiviral vectors, without the accessory genes vif, vpr, vpu, and nef, are able to efficiently transduce nondividing primary human keratinocytes while retroviral vectors are not, regardless of envelope pseudotype. The efficient transduction of the irradiated keratinocytes by lentiviral vectors may be due in part to their active entry into the cell cycle (G1 or later), even though they are nondividing during transduction (3, 25, 43, 52). Furthermore, we demonstrate that following direct in vivo injection of both lentiviral and retroviral vectors into the skin, only lentiviral vectors are able to transduce and express genes in nondividing suprabasal keratinocytes, albeit at very low frequency (<1%). Since the virus vectors cannot be injected into the epidermis but only into the underlying dermis, the efficiency of direct in vivo transduction by lentiviral vectors may be influenced by tissue barriers that limit vector access in addition to intracellular conditions, such as cell cycle status (23). The tissue junction between the epidermis and dermis may prevent lentiviral vectors from gaining access to the epidermis, especially the proliferating keratinocytes present in the basal layer that might be expected to be readily transduced. Additionally, the postmitotic suprabasal keratinocytes may be inefficiently transduced because of their cell cycle status as quiescent G0 cells (even though they are likely to have high mRNA content) (26).

The ability to transduce nondividing keratinocytes suggests that lentiviral vectors might also be superior at transducing keratinocyte progenitor cells during ex vivo culture if they divide only very slowly or infrequently. However, somewhat surprisingly, our ex vivo grafting assays that assess transduction of progenitor cells do not demonstrate that lentiviral vectors are superior to retroviral vectors. After a significant number of epidermal turnovers, these assays demonstrate that comparable percentages of keratinocyte progenitor cells have been transduced in vitro by lentiviral vectors and retroviral vectors. Additionally, the percentages of GFP-expressing keratinocytes for both virus vectors decline only slightly over time from the initial percentage (approximately 55%) expressing keratinocytes in the grafts at the beginning of the assay.

There are several potential explanations for these results. The first is that although keratinocyte progenitor cells may divide and cycle more slowly than other keratinocytes in tissue culture, they are still proceeding through the cell cycle and undergoing mitosis and thus may be transduced equally well by both lentiviral and retroviral vectors. There is certainly circumstantial evidence from long-term studies of skin grafts placed on burn victims suggesting that keratinocyte progenitor cells do divide during in vitro (ex vivo) culture (44). Another theoretical concern is that assessment of the ex vivo results would potentially be difficult because the promoters driving GFP expression on the lentiviral and retroviral vectors are not identical. However, since equivalent percentages of GFP-expressing human keratinocytes were present at the different time points, there is no evidence that the different promoters materially affected the results.

At present there is much that we do not yet know about the biological behavior of keratinocyte progenitor cells or KSC, both in vivo and during in vitro culturing. Increased knowledge about these progenitor cells, including the identification of unique cell surface markers, will allow us to better assess these cells that are so critical for successful skin gene therapy. Even though the above-mentioned data suggest that keratinocyte progenitor cells do divide during ex vivo culture, the ability to identify and enrich these cells for efficient transduction promises to significantly improve our chances to achieve persistent expression in a high percentage of keratinocytes.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Dermatology Branch, including Mark Udey and Kim Yancey, for their many helpful suggestions and input; Jim Panagis for technical help; Oliver Wildner and Michael Blaese for generously providing the retroviral vector; and the laboratory of Inder Verma for generously providing the lentiviral vectors.

We acknowledge financial support for Ulrich Kuhn from the DFG (KU 1187/1-1) and for Atsushi Terunuma from a JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) Research Fellowship award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrandon, Y., and H. Green. 1985. Cell size as a determinant of the clone-forming ability of human keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:5390–5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrandon, Y., V. Li, and H. Green. 1987. Three clonal types of keratinocytes with different capacities for multiplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:2302–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrette, S., J. L. Douglas, N. E. Seidel, and D. M. Bodine. 2000. Lentivirus-based vectors transduce mouse hematopoietic stem cells with similar efficiency to Moloney murine leukemia virus-based vectors. Blood 96:3385–3391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bestor, T. H. 2000. Gene silencing as a threat to the success of gene therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 105:409–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blomer, U., L. Naldini, T. Kafri, D. Trono, I. M. Verma, and F. H. Gage. 1997. Highly efficient and sustained gene transfer in adult neurons with a lentivirus vector. J. Virol. 71:6641–6649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns, J. C., T. Friedmann, W. Driever, M. Burrascano, and J. K. Yee. 1993. Vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein pseudotyped retroviral vectors: concentration to very high titer and efficient gene transfer into mammalian and nonmammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8033–8037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Case, S. S., M. A. Price, C. T. Jordan, X. J. Yu, L. Wang, G. Bauer, D. L. Haas, D. Xu, R. Stripecke, L. Naldini, D. B. Kohn, and G. M. Crooks. 1999. Stable transduction of quiescent CD34+/CD38− human hematopoietic cells by HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2988–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, W. Y., E. C. Bailey, S. L. McCune, J.-Y. Dong, and T. M. Townes. 1997. Reactivation of silenced, virally transduced genes by inhibitors of histone deacetylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5798–5803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choate, K. A., and P. A. Khavari. 1997. Sustainability of keratinocyte gene transfer and cell survival in vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 8:895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotsarelis, G., S. Z. Cheng, G. Dong, T. T. Sun, and R. M. Lavker. 1989. Existence of slow-cycling limbal epithelial basal cells that can be preferentially stimulated to proliferate: implications on epithelial stem cells. Cell 57:201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotsarelis, G., P. Kaur, D. Dhouailly, U. Hengge, and J. Bickenbach. 1999. Epithelial stem cells in the skin: definition, markers, localization and functions. Exp. Dermatol. 8:80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng, H., Q. Lin, and P. A. Khavari. 1997. Sustainable cutaneous gene delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:1388–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans, J. T., P. F. Kelly, E. O’Neill, and J. V. Garcia. 1999. Human cord blood CD34+/CD38− cell transduction via lentivirus-based gene transfer vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 10:1479–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenjves, E. S., S.-N. Yao, K. Kurachi, and L. B. Taichman. 1996. Loss of expression of a retrovirus-transduced gene in human keratinocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 106:576–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs, E., and J. A. Segre. 2000. Stem cells: a new lease on life. Cell 100:143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garlick, J. A., and L. B. Taichmani. 1994. Fate of human keratinocytes during reepithelialization in an organotypic culture model. Lab. Investig. 70:916–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelfant, S. 1982. “Of mice and men”: the cell cycle in human epidermis in vivo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 78:296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerrard, A. J., D. L. Hudson, G. G. Brownlee, and F. M. Watt. 1993. Towards gene therapy for haemophilia B using primary human keratinocytes. Nat. Genet. 3:180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghazizadeh, S., R. Harrington, and L. B. Taichman. 1999. In vivo transduction of mouse epidermis with recombinant retroviral vectors: implications for cutaneous gene therapy. Gene Ther. 6:1267–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halprin, K. 1972. Epidermal turnover time—a re-examination. Br. J. Dermatol. 84:277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hengge, U. R., E. F. Chan, R. A. Foster, P. S. Walker, and J. C. Vogel. 1995. Cytokine gene expression in epidermis with biological effects following injection of naked DNA. Nat. Genet. 10:161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kafri, T., U. Blomer, D. A. Peterson, F. H. Gage, and I. M. Verma. 1997. Sustained expression of genes delivered directly into liver and muscle by lentiviral vectors. Nat. Genet. 17:314–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kay, M. A., J. C. Glorioso, and L. Naldini. 2001. Viral vectors for gene therapy: the art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat. Med. 7:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolodka, T., J. A. Garlick, and L. B. Taichman. 1998. Evidence for keratinocyte stem cells in vitro: long-term engraftment and persistence of transgene expression from retrovirus-transduced keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:4356–4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korin, Y. D., and J. A. Zack. 1999. Nonproductive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in nucleoside-treated G0 lymphocytes. J. Virol. 73:6526–6532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korin, Y. D., and J. A. Zack. 1998. Progression to the G1b phase of the cell cycle is required for completion of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcription in T cells. J. Virol. 72:3161–3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange, C., and T. Blankenstein. 1997. Loss of retroviral gene expression in bone marrow reconstituted mice correlates with down-regulation of gene expression in long-term culture initiating cells. Gene Ther. 4:303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavker, R. M., S. Miller, C. Wilson, G. Cotsarelis, Z. G. Wei, J. S. Yang, and T. T. Sun. 1993. Hair follicle stem cells: their location, role in hair cycle, and involvement in skin tumor formation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 101(Suppl. 1):16S–26S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavker, R. M., and T.-T. Sun. 1983. Epidermal stem cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 81:121S–127S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavker, R. M., and T. T. Sun. 2000. Epidermal stem cells: properties, markers, and location. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:13473–13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehrer, M. S., T. T. Sun, and R. M. Lavker. 1998. Strategies of epithelial repair: modulation of stem cell and transit amplifying cell proliferation. J. Cell Sci. 111:2867–2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levy, L., S. Broad, A. Zhu, J. Carroll, I. Khazaal, B. Peault, and F. Watt. 1998. Optimised retroviral infection of human epidermal keratinocytes: long-term expression of transduced integrin gene following grafting on to SCID mice. Gene Ther. 5:913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller, D. G., M. A. Adam, and A. D. Miller. 1990. Gene transfer by retrovirus vectors occurs only in cells that are actively replicating at the time of infection. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:4239–4242. (Erratum, 12:433, 1992.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mochizuki, H., J. P. Schwartz, K. Tanaka, R. O. Brady, and J. Reiser. 1998. High-titer human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based vector systems for gene delivery into nondividing cells. J. Virol. 72:8873–8883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan, J. R., Y. Barrandon, H. Green, and R. C. Mulligan. 1987. Expression of an exogenous growth hormone gene by transplantable human epidermal cells. Science 237:1476–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris, R. J., S. M. Fischer, and T. J. Slaga. 1985. Evidence that the centrally and peripherally located cells in the murine epidermal proliferative unit are two distinct cell populations. J. Investig. Dermatol. 84:277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naldini, L., U. Blomer, F. H. Gage, D. Trono, and I. M. Verma. 1996. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11382–11388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naldini, L., U. Blomer, P. Gallay, D. Ory, R. Mulligan, F. H. Gage, I. M. Verma, and D. Trono. 1996. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 272:263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oshima, H., A. Rochat, C. Kedzia, K. Kobayashi, and Y. Barrandon. 2001. Morphogenesis and renewal of hair follicles from adult multipotent stem cells. Cell 104:233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Page, K. A., N. R. Landau, and D. R. Littman. 1990. Construction and use of a human immunodeficiency virus vector for analysis of virus infectivity. J. Virol. 64:5270–5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer, T., G. Rosman, W. Osborne, and A. Miller. 1991. Genetically modified skin fibroblasts persist long after transplantation but gradually inactivate introduced genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:1330–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parenteau, N., P. Bilbo, C. Nolte, V. Mason, and M. Rosenberg. 1992. The organotypic culture of human skin keratinocytes and fibroblasts to achieve form and function. Cytotechnology 9:163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park, F., K. Ohashi, W. Chiu, L. Naldini, and M. A. Kay. 2000. Efficient lentiviral transduction of liver requires cell cycling in vivo. Nat. Genet. 24:49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pellegrini, G., R. Ranno, G. Stracuzzi, S. Bondanza, L. Gurerra, G. Zambruno, G. Micali, and M. DeLuca. 1999. The control of epidermal stem cells (holoclones) in the treatment of massive full-thickness burns with autologous keratinocytes cultured on fibrin. Transplantation 68:868–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfutzner, W., U. R. Hengge, M. A. Joari, R. A. Foster, and J. C. Vogel. 1999. Selection of keratinocytes transduced with the multidrug resistance gene in an in vitro skin model presents a strategy for enhancing gene expression in vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 10:2811–2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reiser, J. 2000. Production and concentration of pseudotyped HIV-1-based gene transfer vectors. Gene Ther. 7:910–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reiser, J., G. Harmison, S. Kluepfel-Stahl, R. O. Brady, S. Karlsson, and M. Schubert. 1996. Transduction of nondividing cells using pseudotyped defective high-titer HIV type 1 particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:15266–15271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robbins, P. B., Q. Lin, J. B. Goodnough, H. Tian, C. Xinjian, and P. A. Khavari. 2001. In vivo restoration of laminin 5 β3 expression and function in junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5193–5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roe, T., T. C. Reynolds, G. Yu, and P. O. Brown. 1993. Integration of murine leukemia virus DNA depends on mitosis. EMBO J. 12:2099–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stockschlader, M., F. Schuening, T. Graham, and R. Storb. 1994. Transplantation of retrovirus-transduced canine keratinocytes expressing the β-galactosidase gene. Gene Ther. 1:317–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strauss, M. 1994. Liver-directed gene therapy: prospects and problems. Gene Ther. 1:156–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sutton, R. E., M. J. Reitsma, N. Ochida, and P. O. Brown. 1999. Transduction of human progenitor hematopoietic stem cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based vectors is cell cycle dependent. J. Virol. 73:3649–3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sutton, R. E., H. T. M. Wu, R. Rigg, E. Bohnlein, and P. O. Brown. 1998. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vectors efficiently transduce human hematopoietic stem cells. J. Virol. 72:5781–5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uchida, N., R. E. Sutton, A. M. Friera, D. He, M. J. Reitsma, W. C. Chang, G. Veres, R. Scollay, and I. L. Weissman. 1998. HIV, but not murine leukemia virus, vectors mediate high efficiency gene transfer into freshly isolated G0/G1 human hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11939–11944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watt, F. M. 1998. Epidermal stem cells: markers, patterning and the control of stem cell fate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Biol. Sci. 353:831–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White, S. J., S. M. Page, P. Margaritis, and G. G. Brownlee. 1998. Long-term expression of human clotting factor IX from retrovirally transduced primary human keratinocytes in vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 9:1187–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wildner, O., F. Candotti, E. G. Krecko, K. G. Xanthopoulos, W. J. Ramsey, and R. M. Blaese. 1998. Generation of a conditionally neo(r)-containing retroviral producer cell line: effects of neo(r) on retrovirus titer and transgene expression. Gene Ther. 5:684–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zufferey, R., D. Nagy, R. J. Mandel, L. Naldini, and D. Trono. 1997. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:871–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]