Abstract

The rdgB mutants depend on recombinational repair of double-strand breaks. To assess other consequences of rdgB inactivation in Escherichia coli, we isolated RdgB-dependent mutants. All transposon inserts making cells dependent on RdgB inactivate genes of double-strand break repair, indicating that chromosomal fragmentation is the major consequence of RdgB inactivation.

VARIOUS modifications of the four canonical DNA bases are called base analogs (Negishi et al. 1994). The base analogs hypoxanthine and xanthine are not normally present in RNA or DNA, but can be found in significant amounts in nucleoside monophosphate pools, serving as intermediates in the synthesis of canonical RNA precursors (Neuhard and Nygaard 1987). These nucleoside monophosphates may be converted with a low frequency into deoxynucleoside triphosphates and used by DNA polymerases as noncanonical DNA precursors. Since the pools of DNA precursors are constantly contaminated by noncanonical deoxyribonucleotides, the cell employs specialized NTPases that hydrolyze specific noncanonical nucleoside triphosphates to monophosphates (Bessman et al. 1996). In the absence of such “cleansing” of dNTP pools, the incorporation of base analogs into DNA may cause DNA damage or mutations (Michaels et al. 1992; Bradshaw and Kuzminov 2003; Kouzminova and Kuzminov 2004).

We study how the cell copes with the base analog toxicity by employing the rdgB mutants, originally isolated in Escherichia coli as synthetic lethals in combination with recA inactivation (Clyman and Cunningham 1987; Kouzminova et al. 2004) and later shown to be also synthetically lethal with recBC and ruvABC mutations (Bradshaw and Kuzminov 2003). The rdgB mutants experience increased levels of double-strand breaks in their chromosome, implicating the RdgB protein in avoidance of chromosomal fragmentation (Bradshaw and Kuzminov 2003; Kouzminova et al. 2004). Both the chromosomal fragmentation and the synthetic lethality of rdgB rec mutants are suppressed by inactivation of Endo V (Bradshaw and Kuzminov 2003), which nicks DNA near hypoxanthine and xanthine residues (Yao et al. 1994; Yao and Kow 1995; He et al. 2000). Moreover, DNA in rdgB mutants accumulates EndoV-recognized modifications (Bradshaw and Kuzminov 2003). Biochemically, the RdgB protein is an NTPase with a 100-fold preference for the noncanonical nucleotides ITP, XTP, and dITP (Chung et al. 2001, 2002). It is likely that RdgB hydrolyzes noncanonical DNA precursors dITP and dXTP to monophosphates, preventing incorporation of the base analogs hypoxanthine and xanthine into the chromosomal DNA (Bradshaw and Kuzminov 2003). There is still a possibility that RdgB also works in excision of hypoxanthines or xanthines from DNA after the EndoV-catalyzed nicking.

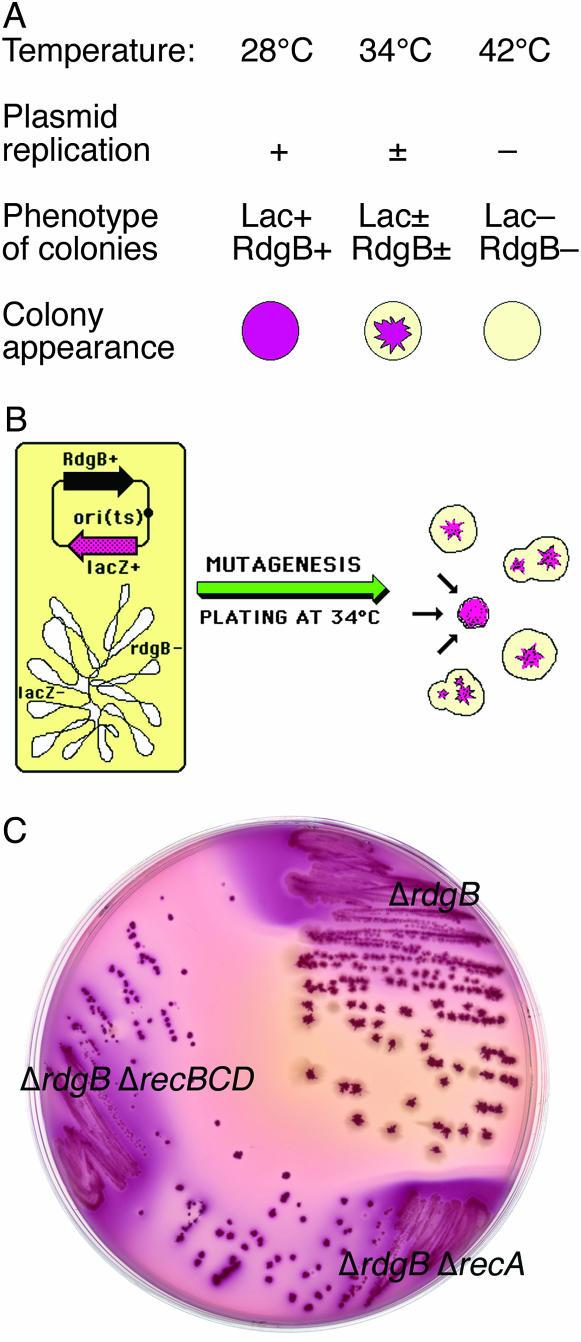

To reveal all the consequences of rdgB inactivation, we identified mutants dependent on RdgB for survival (synthetically lethal with rdgB inactivation). To reveal synthetic-lethal interactions, we utilize a color screen for inability to lose a plasmid (Kranz and Holm 1990; Kouzminova et al. 2004). To build a genetic system for isolation of RdgB-dependent mutants, an rdgB lacZ double-mutant strain was first complemented with rdgB+ and lacZ+ genes from a plasmid that has a temperature-sensitive origin of replication (Figure 1). The resulting strain is rdgB+ lacZ+ when grown at 28° but becomes rdgB− lacZ− mutant when grown at temperatures 37° or higher (Figure 1A). When grown at 34° on MacConkey plates, the plasmid is lost from the cells at a rate of ∼5% per generation. Since it takes ∼25 generations for a cell to grow into a 3- to 4-mm colony, this seemingly low rate of plasmid loss nevertheless results in a colony in which only ∼30% of the cells still keep the plasmid (0.9525 ∼0.3). Therefore, when colonies of the strain are plated on MacConkey plates at 34°, they have dark-purple star-shaped centers surrounded by broad colorless borders (Figure 1A). This sectoring phenotype indicates loss of the plasmid in ∼70% of the cells in the colony. However, if an RdgB-dependent mutant forms a colony, the cells become inhibited when they lose the plasmid (and the rdgB+ gene with it), so the colony is made up only of cells that still keep the plasmid. As a result, this colony is expected to be smaller and solidly colored without sectoring (Figure 1B). Plating of the original ΔrdgB strain and two positive controls (ΔrdgB ΔrecA and ΔrdgB ΔrecBCD double mutants) at 34° confirms the reasoning (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

The color screen for RdgB-dependent mutants. The screen looks for the inability to lose a temperature-sensitive plasmid carrying the rdgB+ gene. (A) The properties of the strain for the screen [LL12 = ΔlacZ ΔrdgB p(ori-Ts)-lacZ+-rdgB+] at three temperatures, plated on MacConkey + lactose agar. (B) The scheme of the experimental strain (LL12) and the expected colony phenotype of RdgB-independent (sectoring) mutants, as well as a single RdgB-dependent mutant (converging arrows). (C) The colony phenotype of the parental color screen strain [LL12 ΔrdgB prdgB + (Ts)] and its two derivatives, carrying either ΔrecA (LL13) or ΔrecBCD (LL14) mutations, on MacConkey–lactose at 34°. The parental strain forms sectoring colonies, whereas the double mutants form smaller nonsectoring colonies, serving as positive controls.

Insertional mutagenesis with a Tn5-based element was carried out as before (Kouzminova et al. 2004) with subsequent screening for the nonsectoring phenotype of colonies on MacConkey medium as an indicator of potential dependence on RdgB. The primary candidates were then confirmed: (1) for the inability to sector upon restreaking on MacConkey-lactose at 34°; (2) for growth inhibition after plasmid loss at 42°; and (3) for sensitivity to DNA damage (UV light). The UV-sensitive mutants were sequenced directly from a DH5α background. UV-resistant mutants were first transduced into an AB1157 background to confirm RdgB dependence; however, none of the UV-resistant mutants proved to be dependent on RdgB in an AB1157 background. Since the insertions are supposed to completely inactivate the affected genes, we did not expect isolating partial inactivation mutants in indispensable genes. The screen statistics are in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

The color screen statistics

| Statistics for the:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| First run | Second run | Third run | |

| Colonies screened | 30,250 | 42,100 | 20,000 |

| Restreaked at 34° | 190 | 367 | Skipped |

| Streaked at 42° | 49 | 78 | 140 |

| UV tested | 16 | 12 | 21 |

| Sequenced from DH5α | 6 | 10 | 4 |

| Transduced into AB1157 | 9 | 2 | None |

| Sequenced from AB1157 | None | None | Not applicable |

We expected to isolate RdgB-dependent mutants in at least four major categories:

Mutants defective in excision repair of DNA modifications that cause repair intermediates to accumulate. The details of the excision repair pathway for DNA hypoxanthines downstream of the EndoV-catalyzed incision step are still unknown. It was anticipated that mutants affecting the post-incision stages of the repair mechanism would be lethal with the rdgB deletion, similar to the lethality of dut mutants in combination with inactivation of exonuclease III (Taylor and Weiss 1982).

Mutants defective in recombinational repair of double-strand breaks. recA, recBC, and ruv mutants are known synthetic lethals with rdgB inactivation (Bradshaw and Kuzminov 2003), so their finding would be “proof-of-principle” for our screen. It was also possible that new genes, previously unknown to be involved in recombinational repair, would be identified.

Mutants defective in avoidance of chromosomal fragmentation. Usually, inactivating one system that avoids chromosomal lesions does not kill the cell (Kouzminova et al. 2004); however, inactivation of two such systems simultaneously may result in an overwhelming amount of chromosomal damage (Reid et al. 1999). Such damage would prevent the cell from replicating its chromosome and would make the double mutant a synthetic lethal.

Mutants with deregulated nucleotide metabolism that accumulate noncanonical DNA precursors (like dITP), normally detoxified by RdgB. For example, overproduction of purA suppresses rdgB rec synthetic lethality (Clyman and Cunningham 1991); therefore, inactivation of purA may cause synthetic lethality in combination with rdgB inactivation. In addition to these categories, there could be mutants inhibited by high levels of the ribonucleotides ITP and XTP.

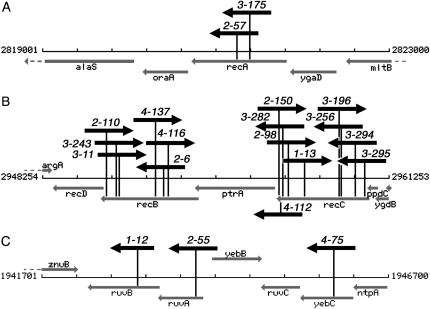

After three runs of the screen, we isolated 20 RdgB-dependent mutants (Table 1). Unexpectedly, all of them turned out to be defective in recombinational repair of double-strand breaks. We obtained nine independent inserts in recC, six independent inserts in recB, two independent inserts in recA, and single inserts in ruvA, ruvB, and yebC genes just upstream of ruvC (Figure 2). Isolation of recA, recB, recC, ruvA, and ruvB mutants, all known synthetic lethals with rdgB (Bradshaw and Kuzminov 2003), proves that the screen works as designed. Isolation of these mutants, all deficient in recombinational repair of double-strand breaks, also provides a strong evidence for double-strand DNA breakage in rdgB mutants. If the combined length of recA, recB, recC, and ruvABC genes (10,119 bp) is divided by the total number of inserts in these genes (20), the density of the inserts in recombinational repair genes comes close to 1/500 bp. The high density of inserts in recB and recC genes and their complete absence in the neighboring recD and ptr genes suggests that (1) the latter two genes have no role in the double-strand break repair; (2) our insertion cassette does not have polar or antisense effects on neighboring genes. Our failure to isolate other known recombinational repair mutants as dependent on RdgB makes it unlikely that there are yet-to-be-identified nonessential genes 2 kbp or longer involved in the double-strand break repair in E. coli. Since double-strand break repair mutants compose the only class of RdgB-dependent mutants, double-strand DNA breaks must be the major consequence of rdgB inactivation.

Figure 2.

The position and orientation of inserts, conferring RdgB dependence, in recombinational repair genes. The vicinity maps of the disrupted genes showing the chromosomal coordinates were generated with Colibri server (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/Colibri/genome.cgi). Open reading frames and their direction are shown by lightly shaded arrows, identified by gene names. The positions of pRL27 inserts are shown by darkly shaded arrows on sticks, identifying the orientation of the kan gene of the insert. The numbers near inserts identify individual mutants. Note that the three maps have different scales. (A) The 4-kbp recA region. (B) The 13-kbp recBCD region. (C) The 5-kbp ruvABC region.

Our inability to isolate other classes of RdgB-dependent mutants, if not a limitation of our specific protocol (see below), is an interesting result in itself. The absence of mutants inactivating steps in the excision of DNA hypoxanthines downstream from the initial EndoV-incision step suggests that either (i) no nonessential enzymes are involved in the subsequent steps (both DNA pol I and DNA ligase are essential under our screen conditions) or (ii) RdgB itself catalyzes this later step before DNA pol I and DNA ligase finish the repair. On the other hand, the absence of inactivational mutants in the nucleotide metabolism that would overproduce dITP suggests that there are no such mutants (at least in dispensable genes) and that there are no activities other than RdgB that detoxify dITP and dXTP. Indeed, our genetic findings from a different approach indicate that dITP is produced in the cell via multiple spurious and therefore difficult-to-control reactions, rather than via one major, tightly controlled reaction (B. Budke, J. Bradshaw, S. Horrell and A. Kuzminov, unpublished results).

There is a possibility that our failure to isolate other classes of RdgB-dependent mutants is due to certain restrictions of our screen, for example, the confirmation of UV-resistant mutants in a different background in which double mutants happen to be viable. Also, our screen, by employing a P1 transduction step, is biased against slow-growing (low-viability) mutants. This may be the reason why we did not isolate low-viability recombinational repair-deficient mutants like priA, a likely candidate for another RdgB-dependent mutant. Employing less restrictive confirmation protocols in the future may broaden the scope of RdgB-dependent mutants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jill Bradshaw for guidance at the initial stages of the project and Elena Kouzminova for providing strains and general support and for commenting on the manuscript.

References

- Bessman, M. J., D. N. Frick and S. F. O'Handley, 1996. The MutT proteins or “Nudix” hydrolases, a family of versatile, widely distributed, “housecleaning” enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 25059–25062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, J. S., and A. Kuzminov, 2003. RdgB acts to avoid chromosome fragmentation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 48: 1711–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J. H., J. H. Back, Y. I. Park and Y. S. Han, 2001. Biochemical characterization of a novel hypoxanthine/xanthine dNTP pyrophosphatase from Methanococcus jannaschii. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 3099–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J. H., H. Y. Park, J. H. Lee and Y. Jang, 2002. Identification of the dITP- and XTP-hydrolyzing protein from Escherichia coli. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35: 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyman, J., and R. P. Cunningham, 1987. Escherichia coli K-12 mutants in which viability is dependent on recA function. J. Bacteriol. 169: 4203–4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyman, J., and R. P. Cunningham, 1991. Suppression of the defects in rdgB mutants of Escherichia coli K-12 by the cloned purA gene. J. Bacteriol. 173: 1360–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, B., H. Qing and Y. W. Kow, 2000. Deoxyxanthosine in DNA is repaired by Escherichia coli endonuclease V. Mutat. Res. 459: 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzminova, E. A., and A. Kuzminov, 2004. Chromosomal fragmentation in dUTPase-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli and its recombinational repair. Mol. Microbiol. 51: 1279–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzminova, E. A., E. Rotman, L. Macomber, J. Zhang and A. Kuzminov, 2004. RecA-dependent mutants in E. coli reveal strategies to avoid replication fork failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 16262–16267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz, J. E., and C. Holm, 1990. Cloning by function: an alternative approach for identifying yeast homologs of genes from other organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87: 6629–6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, M. L., J. Tchou, A. P. Grollman and J. H. Miller, 1992. A repair system for 8-oxo-7,8-dihydrodeoxyguanine. Biochemistry 31: 10964–10968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi, K., T. Bessho and H. Hayatsu, 1994. Nucleoside and nucleobase analog mutagens. Mutat. Res. 318: 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhard, J., and P. Nygaard, 1987. Purines and pyrimidines, pp. 445–473 in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology, edited by F. C. Neidhardt. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- Reid, R. J., P. Fiorani, M. Sugawara and M. A. Bjornsti, 1999. CDC45 and DPB11 are required for processive DNA replication and resistance to DNA topoisomerase I-mediated DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 11440–11445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. F., and B. Weiss, 1982. Role of exonuclease III in the base excision repair of uracil-containing DNA. J. Bacteriol. 151: 351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, M., and Y. W. Kow, 1995. Interaction of deoxyinosine 3′-endonuclease from Escherichia coli with DNA containing deoxyinosine. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 28609–28616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, M., Z. Hatahet, R. J. Melamede and Y. W. Kow, 1994. Purification and characterization of a novel deoxyinosine-specific enzyme, deoxyinosine 3′ endonuclease, from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 16260–16268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]