Abstract

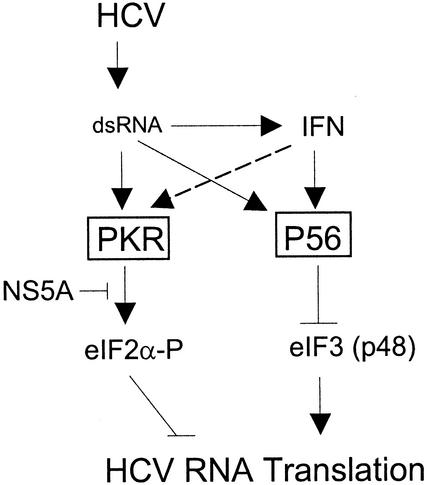

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is treated with interferon (IFN)-based therapy. The mechanisms by which IFN suppresses HCV replication are not known, and only limited efficacy is achieved with therapy because the virus directs mechanisms to resist the host IFN response. In the present study we characterized the effects of IFN action upon the replication of two distinct quasispecies of an HCV replicon whose encoded NS5A protein exhibited differential abilities to bind and inhibit protein kinase R (PKR). Metabolic labeling experiments revealed that IFN had little overall effect upon HCV protein stability or polyprotein processing but specifically blocked translation of the HCV RNA, such that the replication of both viral quasispecies was suppressed by IFN treatment of the Huh7 host cells. However, within cells expressing an NS5A variant that inhibited PKR, we observed a reduced level of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha subunit (eIF2α) phosphorylation and a concomitant increase in HCV protein synthetic rates, enhancement of viral RNA replication, and a partial rescue of viral internal ribosome entry site (IRES) function from IFN suppression. Assessment of the ribosome distribution of the HCV replicon RNA demonstrated that the NS5A-mediated block in eIF2α phosphorylation resulted in enhanced recruitment of the HCV RNA into polyribosome complexes in vivo but only partially rescued the RNA from polyribosome dissociation induced by IFN treatment. Examination of cellular proteins associated with HCV-translation complexes in IFN-treated cells identified the P56 protein as an eIF3-associated factor that fractionated with the initiator ribosome-HCV RNA complex. Importantly, we found that P56 could independently suppress HCV IRES function both in vitro and in vivo, but a mutant P56 that was unable to bind eIF3 had no suppressive action. We conclude that IFN blocks HCV replication through translational control programs involving PKR and P56 to, respectively, target eIF2- and eIF3-dependent steps in the viral RNA translation initiation process.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem. Conservative figures indicate that greater than 170 million people are persistently infected with HCV worldwide, and epidemiologic studies have identified the virus as the major cause of chronic hepatitis and liver disease in the human population (1, 2). HCV constitutes the Hepacivirus genus of the family Flaviviridae, and is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus (44). The features of the HCV genome include a 5′-nontranslated region (NTR) that encodes an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) that directs the translation of a single long open reading frame (ORF) encoding a polyprotein of ca. 3,010 amino acids. The HCV ORF is followed by a 3′-NTR of variable length that encodes the sequences required for the initiation of antigenomic strand synthesis (44). The HCV IRES and 3′-NTR both encode regions of extensive double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) structure that are required for genome translation and replication. The HCV polyprotein is posttranslationally processed into at least 10 mature viral proteins, including the structural proteins core, E1, and E2 and the nonstructural (NS) proteins NS2 to NS5B (see Fig. 1). Seminal work from Bartenschlager and coworkers has demonstrated that the regions encoding the HCV 5′-NTR/IRES and NS3-3′-NTR are sufficient to support the autonomous replication of a bicistronic HCV subgenomic replicon RNA in cultured human hepatoma cells (33). The development of this HCV subgenomic replicon system has partially overcome limitations placed on HCV research that are due to an inability to efficiently propagate native HCV in cultured cells.

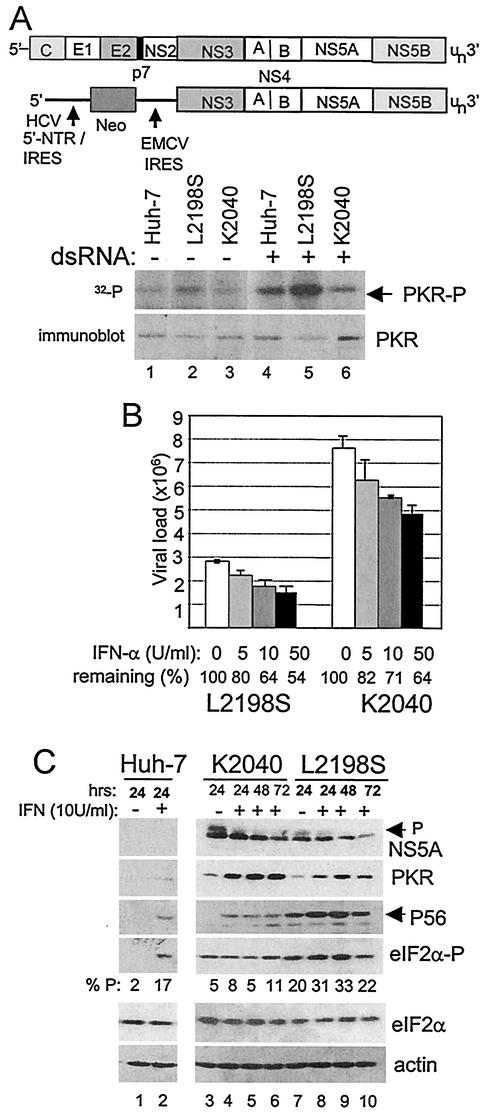

FIG. 1.

Assessment of PKR activity and viral RNA levels within Huh7 control and HCV replicon cells. (A) Analysis of in vivo PKR activity during HCV RNA replication. The diagram shows comparative structural representations of the HCV genome (upper) and subgenomic replicon, denoting the HCV 5′-NTR/IRES, the EMCV IRES, and regions encoding the neomycin-resistance protein (Neo) and the various cleavage products of the HCV polyprotein. The panels show protein analyses of Huh7 control and replicon cells that were cultured alone (lanes 1 to 3) or in the presence of 40 μg of dsRNA/ml (lanes 4 to 6) as described in Materials and Methods. In the upper panel, the phosphorylation state (activity) of PKR was assessed by 32P metabolic labeling of proteins, followed by anti-PKR immunoprecipitation anal-ysis of control Huh7 cells (lanes 1 and 4) and Huh7 cells harboring the L2198S (lanes 2 and 5) or K2040 HCV replicon quasispecies (lanes 3 and 6). The lower panel is an immunoblot analysis of PKR levels present within identical parallel cultures of Huh7 control and replicon cells. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) HCV RNA levels in IFN-treated HCV replicon cells. HCV RNA levels were quantified by real-time RT-PCR assay of total RNA extracted from Huh7 cells harboring the L2198S or K2040 HCV replicon that were cultured for 24 h alone or with the indicated concentrations of IFN-α. Bars show combined data from three independent experiments presenting the overall average and standard deviation of RNA copy number relative to the GAPDH mRNA levels present within each sample. The percent viral RNA remaining after each 24 h IFN treatment is shown beneath the respective bar. (C) Protein expression and eIF2α phosphorylation in HCV replicon cell cultures. Huh7 control cells (lanes 1 and 2) and Huh7 cells harboring the K2040 (lanes 3 to 6) or L2198S HCV replicon quasispecies (lanes 7 to 10) were cultured alone or with 10 U of IFN-α/ml for the time indicated above each lane. Protein levels in cell extracts were determined by immunoblot analysis. The arrows point to the positions of the high-mass, hyperphosphorylated NS5A isoform or to P56. eIF2α-P denotes the expression of the S51-phosphorylated species of eIF2α. The relative levels of eIF2α-P from total eIF2α were quantified by densitometric analysis and are presented below each corresponding lane. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Infection with HCV is currently treated with alpha interferon (IFN-α)-based therapy. Although the treatment outcome is variable among the six major HCV genotypes, only about one-half of all treated patients respond to therapy (38), suggesting that the virus encodes protein products that may directly or indirectly attenuate the antiviral actions of IFN. IFNs are naturally produced in response to virus infection, and cellular exposure to IFN leads to the induced expression of a variety of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), many of which have an antiviral function (16). ISG action can limit virus replication at multiple points within the replicative cycle (reviewed in reference 47). Although the mechanisms of IFN action against HCV replication have not been defined, recent studies suggest that IFN may impact HCV replication, in part, by inducing translational control programs that suppress the function of the HCV IRES (23, 49).

At least three distinct cellular pathways of translational control are responsive to IFN and virus infection, including the 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS)/RNase L pathway, the protein kinase R (PKR)-eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha subunit (eIF2α) pathway, and the P56-eIF3 pathway (13, 48). Activation of RNase L RNase activity by OAS can lead to translational suppression in part through the cleavage and subsequent inactivation of the 28S rRNA (50). Activation of PKR during virus infection leads to the PKR-catalyzed phosphorylation on serine-51 of eIF2α. This phosphorylation event blocks translation initiation by reducing the cellular pool of functional eIF2 and disrupting the critical delivery of methionyl-tRNA to the 40S ribosome (6). P56 has been identified as an eIF3-binding protein and a suppressor of translation (19, 47). The actual mechanism by which the P56-eIF3 interaction interferes with translation has not been defined, although P56-mediated translational suppression is conferred through P56 binding to the Int-6/p48 subunit of eIF3 (18). Importantly, each of these translational regulatory pathways may potentially impact translation from the HCV IRES, which, in addition to the ribosomal proteins, utilizes only eIF2 and eIF3 for initiation of HCV translation (39, 51).

In addition to regulation through IFN, dsRNA plays a major role in regulating the enzymatic activities or protein levels involved in the aforementioned translational control programs. The activation of OAS and PKR enzymatic activity requires physical interaction with dsRNA, and both enzymes are efficiently activated by dsRNA replicative products of virus infection (6, 50). Moreover, dsRNA accumulation within virus-infected cells can trigger P56 expression independently of IFN (14, 19). The dual responsiveness of these translational control pathways to dsRNA and IFN allows immediate action within the cellular antiviral response and labels these pathways as important targets for regulation by virus-encoded processes. In particular, PKR is targeted for regulation by many eukaryotic viruses (reviewed in reference 11), and in many virus systems inhibition of PKR is a key feature that confers virulence, persistence, and pathogenesis (24, 31, 57).

Previous studies have identified the HCV E2 and NS5A proteins as IFN antagonists and PKR inhibitors (12, 54), suggesting that HCV encodes multiple mechanisms to block PKR action. The NS5A protein encodes a 64-amino-acid PKR-binding domain within its C-terminal region that mechanistically directs the disruption of active PKR dimers in vivo (9). Recent studies have independently confirmed these observations (20, 37), and others have shown that NS5A can also antagonize the IFN response and host apoptotic programs through mechanisms that do not involve PKR (53). Moreover, the use of the HCV subgenomic replicon system has identified NS5A as an important factor in supporting viral RNA replication. Analyses of cell culture-adapted HCV replicon quasispecies derived from the prototypic HCV replicon sequence (33) have identified mutations that cluster within the NS5A-coding region and dramatically influence HCV RNA replication efficiency (5, 29), in part through the regulation of PKR (40). Similarly, many molecular epidemiology sequencing studies of viral RNA isolated from infected patients have correlated the sequence of the PKR-binding domain and the inclusive IFN sensitivity determining region with HCV persistence and resistance to IFN therapy (53, 56). These results indicate that the NS5A protein may support HCV replication, in part, by mediating regulatory interactions with components of the host cell antiviral response. Taken together, these studies implicate a role for the viral NS5A protein in mediating HCV persistence and resistance to the current IFN therapy for the treatment of HCV infection.

The present study was undertaken to assess the mechanisms by which IFN limits HCV replication and to determine the role of NS5A and PKR in regulating IFN action. We hypothesized that IFN can limit HCV replication through mechanisms that involve PKR-dependent and -independent processes. Using the HCV subgenomic replicon system, we demonstrate that IFN dramatically impacts HCV protein synthesis and that this occurs through distinct translational control programs that involve PKR and P56. Our results indicate that NS5A inhibition of PKR can confer a partial resistance against the translational suppressive actions of IFN and that this regulatory interaction is critical for maintaining an overall high HCV RNA translation efficiency and viral load. Moreover, we identify P56 as a key antiviral effector that directs the PKR-independent suppression of HCV IRES function to suppress viral RNA translation during the IFN response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) products encoding the entire NS5A coding region of HCV were amplified by using the oligonucleotide primers 5′-AAGCTTATGTCCGGCTCGTGGCTAAGAGATG-3′ (sense) and 5′-TCTAGACTAGCAGCAGACGACGTCCTCACTAGC-3′ (antisense) encoding HindIII and XbaI restriction sites, respectively. The RNA template consisted of total cellular RNA isolated from Huh7 cells harboring the K2040 or L2198S HCV 1B replicon quasispecies (40). The resulting cDNA products were cloned into the HindIII/XbaI sites of pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) to yield p5A K2040 and p5A L2198S. The NS5A sequence was confirmed by Applied Biosystems automated sequence analysis. pcDNA1neo-HA-PKR K296R and pRc/CMV-eIF2αS51A were previously described and were gifts from M. Katze and N. Sonenberg, respectively. HA-PKR-K296R encodes the dominant-negative PKR mutant (25) fused in-frame to the human influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag. pRL-HL (a gift from S. Lemon) is a bicistronic expression construct encoding the Renilla and firefly luciferase cDNAs translated from the 5′ cap and internally from the HCV IRES, respectively (21). Similarly, pCMVRluc-EFluc (a gift from Michael Katze) is a bicistronic reporter construct encoding Renilla luciferase in the 5′ cistron, followed by the complete EMCV IRES that directs firefly luciferase translation internally from the downstream second cistron. pCMV-P56 and pCMV-MP56 were previously described and encode wild-type P56 or mutant P56 (MP56; encoding P56 amino acids 1 to 339), respectively (18).

Cell culture and transfection.

Huh7 (human hepatoma) cells were propagated in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 200 μM l-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin. Huh7 cells harboring the K2040 or L2198S variants of the HCV 1B subgenomic replicon were described previously (40) and were propagated in the presence of 200 μg of G418/ml except where indicated. For luciferase assays, 5 × 105 cells were seeded into the wells of a six-well dish. After 24 h the cells were transfected with various plasmid combinations by using the FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche). For simultaneous assessment of cap-dependent and viral IRES-dependent translation, cells were transfected with 1.0 μg of the bicistronic reporter plasmid pRL-HL (21) or pCMVRluc-EFluc. At 24 h after transfection cells were harvested, and extracts were prepared and subjected to dual luciferase assay (Promega) or immunoblot analysis. For IFN treatment, cells were cultured in the presence of IFNα-2A (Research Diagnostics, Inc.) by replacing the culture media with fresh medium containing the indicated IFN concentration.

Protein analyses.

For immunoblot and immunoprecipitation analysis cells were harvested by scraping the culture monolayer into 1 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were washed three times in ice-cold PBS, pellets resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM okadaic acid, 10 U of aprotinin/ml, and 10 μl of Sigma protease inhibitor cocktail), and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation and collected in a fresh tube. The protein concentration in each lysate was determined by using the Bio-Rad protein assay. For immunoblot analysis, 25 μg of protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-12.5% PAGE) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Membranes were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using the indicated antibody preparations and the ECL-Plus chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham) exactly as described previously (10). The primary antibodies used for immunoblot analysis were anti-HCV patient serum (obtained with informed consent from W. Lee), anti-PKR monoclonal antibody 71/10 (a kind gift from A. Hovanessian), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-eIF2α (Research Genetics, Inc.), anti-eIF2α monoclonal antibody (12), rabbit polyclonal anti-P56 antibody (19), goat polyclonal anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz), and rabbit polyclonal anti-eIF3 antibody (a gift from J. Hershey) (3). For immunoprecipitation analysis, lysates representing 5 × 105 total cells that were metabolically labeled were incubated with 1 μl of anti-NS3 or anti-NS5B monoclonal ascites (a kind gift from D. Moradpour), anti-PKR 71/10 monoclonal ascites (30), or polyclonal anti-NS4B serum (a kind gift from R. Bartenschlager) or polyclonal anti-NS5A serum (40) in a total volume of 500 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer. Immunocomplexes were recovered by a second incubation with protein G-agarose or protein A-agarose beads, washed extensively in lysis buffer containing 350 mM NaCl, and prepared for SDS-PAGE exactly as described previously (10). Labeled proteins were visualized by autoradiography of the dried gel. Radiolabel incorporation of the proteins was quantified by phosphorimager analysis.

For [35S]methionine metabolic labeling, 5 × 105 Huh7 control cells or Huh7 cells harboring the K2040 HCV replicon were seeded into the well of six-well dish. After 24 h the cells were rinsed, and the culture media was replaced with DMEM alone or with DMEM containing the indicated amount of IFN. Cultures were then incubated for a further 16 to 24 h, and the medium was replaced with 1 ml of methionine-free DMEM containing 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum and 200 μCi of [35S]methionine. Cultures were labeled for 30 min. For pulse-chase analysis, cells were cultured without IFN for 24 h, followed by a 30-min pulse-labeling period, after which IFN-α and excess cold methionine were added, and cells were harvested at the indicated intervals. Alternatively, cells were cultured in the presence or absence of IFN for 24 h, followed by constant labeling in the presence of [35S]methionine, and cells were harvested over a 2-h time period to assess the influence of IFN upon the kinetics of HCV polyprotein processing. Cell extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation analysis with HCV-specific antibodies as described above.

32P-metabolic labeling of proteins was conducted on cultures of 4 × 105 Huh7 cells alone or harboring the K2040 or L2198S HCV replicon that were seeded into the wells of a six-well dish. After 24 h, the cell monolayer was rinsed and the cells were mock transfected or transfected with 40 μg of poly(I-C) (pIC) by using the Effectine reagent and the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen). Cultures were incubated for a further 1 h, and the medium was replaced with 1 ml of DMEM or phosphate-free DMEM containing 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum. After 1 h, the culture medium was supplemented with 400 μCi of [32P]orthophosphoric acid, and cultures were incubated for a further 1-h period. Cells were harvested, and extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation analysis to assess the intracellular phosphorylation state of PKR.

Polyribosome distribution analysis.

Analysis of ribosome-HCV RNA association in Huh7 cells harboring HCV replicon quasispecies was conducted after the methods of Ruan et al. (46). Huh7 cells harboring the K2040 or L2198S HCV replicon were cultured in two 15-cm dishes each at ca. 80% confluency in the presence or absence of 10 U of IFN/ml for 24 h. We confirmed that a cell culture density of 80% confluency did not affect the steady-state HCV RNA level present in each replicon cell line (J. Pflugheber and M. Gale, Jr., unpublished observations). Prior to cell harvest, the culture medium was then replaced with prewarmed medium containing 100 μg of cycloheximide (CHX)/ml and incubated for 15′ at 37°C. Cells were rinsed twice with prewarmed PBS containing 100 μg of CHX (PBS-CHX)/ml, the solution was removed, and the cells were released from the dish by incubation in a prewarmed trypsin-CHX solution. Cells were washed from the culture dish with 10 ml of PBS-CHX containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and were pooled into a tube containing and additional 5 ml of ice-cold PBS-CHX. Tubes were subjected to centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, the supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was washed once with 10 ml of ice-cold PBS-CHX. Cell pellets were resuspended in 750 μl of ice-cold low-salt buffer (LSB; 20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 30 mM MgCl2), and tubes were placed on ice for a total time of 3 min to allow cell swelling. After the addition 250 μl of detergent buffer (LSB supplemented with 1.2% Triton N-101), cell suspensions were transferred into an ice-cold 7-ml Dounce homogenizer and homogenized with seven strokes of the pestle. The homogenate was transferred to an ice-cold microcentrifuge tube and subjected to a 1-min centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant was then collected and transferred to an ice-cold recipient tube containing 100 μl of LSB supplemented with 1 mg of heparin and containing a final concentration of 1.5 M NaCl. The lysate mixture was layered carefully on top of a 0.5 to 1.5 M sucrose gradient prepared in a 14-by-95-mm polyallomer centrifuge tube. Gradients were centrifuged for 2 h at 36,000 rpm in a Beckman SW40 rotor. Afterward, 12 1-ml fractions were collected in a top-to-bottom manner from each gradient tube by using an ISCO density gradient fractionator (ISCO, Inc.). Fractions were monitored for optical density by using a wavelength of 254 nm. All fractions were collected into microcentrifuge tubes containing 100 μl of 10% SDS, after which 220 μg of proteinase K was added to each tube. Tubes were incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and RNA was extracted from each by using the Trizol reagent and the manufacturer's protocol (Gibco). For some experiments, we also extracted and collected the protein constituents of each fraction. Proteins were extracted from the organic phase of the Trizol reagent by following the manufacturer's protocol and were precipitated in 100% ethanol, dried, and rehydrated in lysis buffer. For RNA extraction, purified RNA was resuspended in 30 μl of RNase-free water. The integrity of the recovered RNA was confirmed by running 10 μl of each sample on a standard 1% agarose gel and visualizing the ethidium bromide-stained rRNA bands. In addition, since the distribution of the 18S and 28S rRNAs associate with the presence of the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits, respectively (52), this procedure allowed us to confirm the ribosome subunit and polysome distribution of our fractionation procedure.

The gradient distribution (ribosome association) of actin and HCV RNAs was assessed by RT-PCR by using the titanium one-step RT-PCR kit (Clontech) and 1 μl of total RNA isolated from each gradient fraction. The oligonucleotide primer pairs consisted of 5′-TTGTTACCAACTGGGACGACATGG-3′ and 5-GATCTTGATCTTCATGGTGCTAGG-3′ (actin; sense and antisense, respectively) and the previously published KY78 and KY80 primers for HCV RNA amplification (58). PCR amplification was conducted for a total of 25 cycles, which we confirmed represented the mid-linear stage of the amplification cycle (Pflugheber and Gale, unpublished). HCV and actin RT-PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and digital imaging of the ethidium bromide-stained gel.

RNA methods and viral RNA quantification.

For viral RNA quantification and RT-PCR cloning of NS5A sequences, total RNA was first isolated from Huh7 control and replicon cells by using the Trizol reagent. RNA was resuspended in RNA Secure (Ambion) or RNase-free water, quantified, and stored at −80°C until used. HCV replicon RNA levels were quantified in duplicate by performing a single-tube real-time RT-PCR procedure for quantification of HCV RNA and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; gdh) RNA exactly as previously described (34) by using the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system. For viral RNA amplification, we used the oligonucleotide set of 5′-TGCGGAACCGGTGAGTACA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTTAAGGTTTAGGATTCGTGCTCAT-3′ (antisense). The sequence of the fluorescent probe used for the real-time quantification of the viral amplicon was 5′-(FAM)-CACCCTATCAGGCAGTACCACAAGGCC-(TAMRA)-3′. Standard curves for the real-time amplification of viral RNA were generated by using 107 −103 copies of purified template RNA that was transcribed in vitro from the HCV 1B 5′-NTR cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector System I (Promega). Viral copy number values were normalized to the relative level of gdh mRNA within the total input RNA sample. For each analysis at least three individual experiments were performed in duplicate.

For Northern blot analysis purified RNA was resuspended in water, quantified by spectometry, and mixed with RNA loading buffer (10). After being heated at 50°C for 10 min, 10 μg of RNA was separated through a 1% agarose gel containing 2.2 M formaldehyde, 20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (pH 7.0), 8 mM sodium acetate, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). To process the gel for transfer of RNA, the gel was soaked in water for 1 h with gentle agitation, followed by incubation in 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 15 min. RNA transfer onto Nytran membrane was performed by using the Schleicher & Schuell Turboblotter downward transfer system as recommended by the manufacturer. DNA probes specific to the firefly luciferase mRNA or to human GAPDH were generated from plasmid template DNA by using Klenow DNA polymerase and mixed nonomer random primers in a reaction that contained [α-32P]dCTP. Blot hybridization reactions were performed by using the ULTRAhyb reagent (Ambion) and 106 cpm of radiolabeled probe/ml at 42°C for 16 h. Blots were then rinsed twice for 5 min each time with preheated 2× SSC-0.1% SDS wash buffer, followed by two 15-min washes with 0.1× SSC-0.1% SDS wash buffer. Blots were subjected to autoradiography. In some experiments, probe hybridization was quantified by phosphorimager analysis.

In vitro translation assay for the functional analysis of P56.

RNA was transcribed in vitro by using ApaI-digested pRL-HL and the Ambion T7 Megascript kit and 5′ cap analog. A total of 1 μg of mRNA was used to program a rabbit reticulocyte lysate translation system (Promega) in the presence of [35S]methionine and buffer or increasing amounts of recombinant-purified P56 or MP56. The total volume for each reaction was 30 μl. Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 2 h. 35S-labeled proteins were analyzed by subjecting an equal volume of each reaction mixture to SDS-12.5% PAGE and were then quantified by using a phosphorimager.

RESULTS

PKR regulatory properties of distinct HCV RNA replicon quasispecies.

We utilized the HCV subgenomic replicon system to examine the molecular mechanisms by which IFN impacts HCV replication. The HCV subgenomic replicon was prepared according to previously described con1 sequence (33) and, as shown in Fig. 1, comprises a bicistronic RNA in which the 5′-NTR-IRES of HCV drives expression of a drug resistance gene (neo), which is followed by the encephalomyocarditis (EMCV) IRES controlling the translation of a second cistron encoding the HCV NS proteins NS3 to NS5B and 3′-NTR. Expression of the viral NS3 to NS5B proteins from the replicon RNA is sufficient to support HCV RNA replication (33) and allows for the study of viral NS protein-host interactions in the context of HCV RNA replication in cultured cells. We previously characterized and reconstructed distinct quasispecies of the HCV subgenomic replicon that exhibit different replication efficiencies and PKR-regulatory properties (40). Replicon variant K2040 encodes a single K insertion in the N terminus of NS5A located at HCV codon 2040. Our recent studies indicate that this mutation directs the intracellular localization of NS5A sufficiently to confer the formation of a stable inhibitory complex with PKR in vivo (40). In contrast, the L2198S variant encodes an L-to-S substitution at codon 2198 adjacent to the PKR-binding domain of the NS5A coding region. This mutation disrupts the PKR-regulatory properties of NS5A to render increased levels of PKR activity in Huh7 replicon cells (40). To confirm these results we assessed the activity of PKR in vivo directly within control and replicon cell cultures that were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate in the presence or absence of pIC, a potent dsRNA activator of PKR enzymatic activity (Fig. 1A). Immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that in the absence of dsRNA treatment only low levels of the active, phosphorylated form of PKR were present in control Huh7 cells and K2040 replicon cells. Cells harboring the L2198S replicon variant exhibited significantly higher basal levels of active PKR, a finding consistent with the dsRNA activation of PKR during HCV RNA replication (Fig. 1A, upper panel) (40). dsRNA treatment increased the specific activity of PKR within control Huh7 and L2198S replicon cells but had little overall impact on PKR activity in cells harboring the K2040 replicon. We observed an increase in PKR abundance in replicon K2040 cells (see Fig. 1A and C). Previous studies have demonstrated that PKR synthesis is autoregulated at the local site of translation (55) and that higher steady-state levels of the enzyme will accumulate under conditions when PKR activity is suppressed (9, 26). The differential PKR activity and steady-state abundance observed in our experiments is consistent with previous work demonstrating that the NS5A protein encoded within the K2040 replicon can bind and inhibit PKR (40). Our current results extend these observations to include a cellular analysis of PKR activity during HCV RNA replication. These results confirm that PKR is active in vivo within L2198S replicon cells but that this activity is blocked by the K2040 replicon.

Decreased PKR activity is associated with increased viral RNA load.

The differential PKR-regulatory properties of the K2040 and L2198S HCV replicon quasispecies presented a unique system by which to assess the PKR-dependent and -independent actions of IFN on HCV replication and allowed us to assess the functional role of NS5A in these processes. We therefore characterized the response to IFN treatment upon these HCV replicon quasispecies and their Huh7 host cells. As shown in Fig. 1B, real-time RT-PCR quantification of HCV RNA levels revealed a dose-dependent antiviral effect of IFN upon HCV RNA levels in Huh7 cells, and both replicon quasispecies exhibited sensitivity to IFN over the doses used. Of note is the observation that >50% of RNA from each replicon remained, even after 24 h of high-dose IFN treatment, demonstrating that IFN does not completely eliminate HCV RNA within a 24-h treatment in vitro. We found that inhibition of PKR by the K2040 replicon corresponded to significantly higher viral RNA levels (referred to as viral RNA load) that declined more slowly than with the L2198S quasispecies across all IFN doses. In fact, the K2040 HCV replicon maintained a >3-fold increase in viral RNA load versus the L2198S replicon both basally and within IFN-treated cells.

We therefore examined the impact of IFN on steady-state viral and cellular protein expression over a 3-day time course in control Huh7 cells and Huh7 cells harboring the HCV replicons. Cells were cultured with or without 10 U of IFN/ml, which is a physiologic-relevant dose that reflects local tissue IFN levels elicited during virus infection in vivo (4). As seen in Fig. 1C, throughout this time course we observed a reduction in the initial high levels of HCV protein (NS5A) abundance within the K2040 replicon cells, but this was associated with only low levels of the S51-phosphorylated form of eIF2α. In contrast, whereas IFN treatment reduced the overall viral protein abundance within parallel cultures of L2198S replicon cells, this was associated with comparably higher levels of S51-phosphorylated eIF2α (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 3 to 6 with lanes 7 to 10). IFN treatment specifically induced ISG expression in control Huh7 and replicon cell cultures, and we observed the induction of PKR and P56 expression in all cells. Increased basal and IFN-induced levels of PKR were again apparent in extracts from K2040 replicon cultures, a finding consistent with an inhibition of PKR activity and autoregulation in these cells (55). We previously demonstrated that HCV RNA replication of the L2198S replicon actually stimulated dsRNA response pathways in the host cell (40). Consistent with this, we noted an increased basal level of P56 expression, a known dsRNA-responsive ISG (19), within cells harboring this HCV replicon, and P56 levels were further increased in response to IFN treatment (see Fig. 1C). Together, these results demonstrate that HCV replicon cells can respond to IFN to induce ISG expression and limit HCV RNA replication.

IFN suppresses viral protein production from the HCV replicon through PKR-dependent and PKR-independent mechanisms.

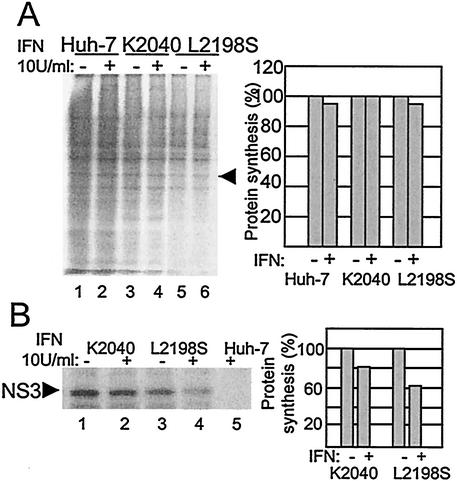

The potential interaction between HCV replication and PKR-mediated translational control programs within HCV replicon cells prompted us to examine the influence of IFN upon cellular and viral protein synthesis within our HCV replicon system. We therefore cultured Huh7 control and replicon cells for 16 h in the absence or presence of IFN. During the final 30 min of the 16-h incubation period cells were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine, and extracts were prepared and analyzed for protein synthetic levels. We found that IFN treatment of control and replicon cell cultures had little overall effect on total cellular protein synthesis (Fig. 2A). However, IFN treatment resulted in a specific and differential decrease in viral protein production within cells harboring the different replicon quasispecies. As shown in Fig. 2B, we observed an approximately 40% reduction in the production of the viral NS3 protein upon IFN treatment of cells harboring the L2198S replicon. In contrast, NS3 production from the K2040 HCV replicon was only reduced by less than 20% after the 16-h IFN treatment, and this result correlated with the higher viral RNA load observed within K2040 replicon cells (see Fig. 1). Thus, the block in PKR activity and eIF2α phosphorylation mediated by the K2040 HCV replicon conferred a significant rescue of viral protein production from the suppressive actions of IFN that were otherwise functional in cells harboring the L2198S HCV replicon. These results indicate that IFN induces PKR-dependent and -independent cellular pathways that limit viral protein production from the HCV replicon.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of cellular and viral protein synthesis in Huh7 cells. (A) Cellular protein synthesis. The left panel shows an autoradiogram from an SDS-PAGE analysis of total cellular proteins within extracts harvested from Huh7 control cells (lanes 1and 2) and Huh7 cells harboring HCV replicon K2040 (lanes3 and 4) or L2198S (lanes 5 and 6) that were cultured in medium alone or in medium containing 10 U of IFN-α/ml for 16 h, followed by [35S]methionine pulse-labeling for 30 min. The band marked by the arrow denotes a cellular protein that was selected for phosphorimager quantification of incorporated radioactivity. The right panel displays the values as a percentage of the amount of the protein produced within cells cultured in the absence of IFN. (B) Synthesis of the HCV NS3 protein. The cell extracts shown in panel A were subjected to immunoprecipitation analysis with a specific antibody against the NS3 protein. The left panel shows an autoradiogram of the NS3 protein (denoted by the arrow) recovered from Huh7 cells harboring the indicated HCV replicon quasispecies (lanes 1 to 4). Lane 5 shows a parallel immunoprecipitation analysis of an extract prepared from IFN-treated Huh7 control cells. The NS3 protein band was quantified by phosphorimager analysis of the dried gel. The right panel shows the phosphorimager quantification of the relative amount of NS3 produced during the labeling period. Values are shown as a percentage relative to the amount of NS3 recovered from cells cultured in the absence of IFN. “+” and “-” denote cell culture in the presence or absence of IFN, respectively. Similar results were obtained from cells cultured in 50 or 100 U of IFN/ml. The results shown were reproduced in three separate experiments.

Effects of IFN on HCV protein stability and polyprotein processing.

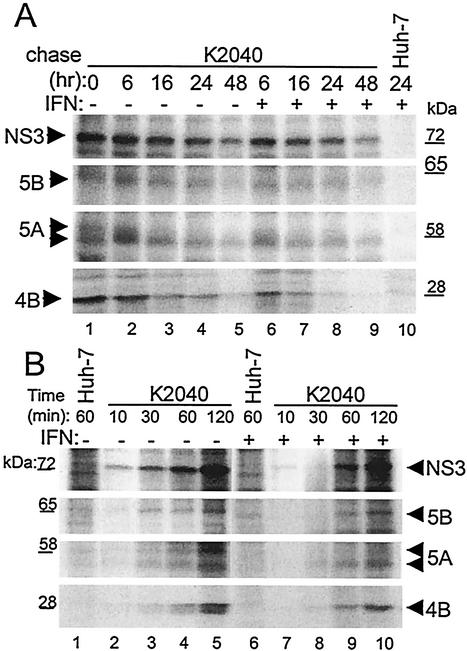

Previous studies have demonstrated that IFN can induce cellular pathways that impact viral protein stability or that alter the maturation kinetics of viral proteins that are processed from a polyprotein precursor (42). To determine whether the PKR-independent IFN-mediated suppression of viral protein production during HCV RNA replication was due to a reduced stability of viral proteins or was a result of altered processing kinetics of the HCV polyprotein, we assessed these features within cells harboring the K2040 HCV replicon. We first conducted pulse-chase experiments of [35S]methionine-labeled cells to examine the effect of IFN treatment on viral protein stability. Control Huh7 or K2040 replicon cells were metabolically labeled for 30 min, followed by a chase period that extended to 24 h (control cells) or 48 h (replicon cells) either in the absence or presence of IFN. Immunoprecipitation analysis of cell extracts demonstrated the production of the mature viral proteins within the initial 30-min pulse period (Fig. 3A). Analysis of cells harvested over the chase period demonstrated that the HCV NS proteins were overall remarkably stable and exhibited a moderate rate of decay and that all proteins were detected through the 48-h time point. With the exception of NS4B, IFN treatment did not significantly impact viral protein stability during the time course examined, and the HCV NS proteins were detected throughout the chase period. We observed an accelerated decay rate of the NS4B protein within the first 6 h of IFN treatment that resulted in an approximately fourfold reduction in protein level compared to untreated cells (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 1 and 6). However, this IFN-induced decay stabilized for the remainder of the chase period to a rate comparable to that in the untreated cells.

FIG. 3.

HCV protein stability and polyprotein processing kinetics within IFN-treated cells. (A) Pulse-chase analysis. Huh7 cells harboring the K2040 HCV replicon were cultured for 24 h, followed by a 30-min pulse-labeling period in the presence of [35S]methionine. After being labeled, the cells were harvested (lane 1, 0 h time point) or were cultured with excess cold methionine alone (− [lanes 2 to 5]) or in the presence of 50 U/ml of IFN-α (+ [lanes 6 to 9]) for the time period indicated (in hours) above each lane. Lane 10 shows a parallel analysis of Huh7 control cells. The indicated HCV proteins were recovered from cell extracts by immunoprecipitation. The panels show an autoradiogram from SDS-PAGE analyses of the recovered immunoprecipitation products (indicated by the arrows). For NS5A, the upper arrow denotes the position of the putative hyperphosphorylated isoform. The incorporation of radiolabel into each protein was quantified by phosphorimager analysis over three separate experiments, and resulting values were used to determine the protein t1/2 (see Table 1). The positions of the molecular mass standards are shown in kilodaltons. Similar results were obtained from cells treated with 10 or 100 U of IFN/ml. (B) HCV polyprotein processing kinetics. Huh7 control cells (lanes 1 and 6) or those harboring the K2040 HCV replicon were cultured alone (lanes 1 to 5) or in the presence of 50 U of IFN-α/ml for 24 h, after which the cells were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine for the time period shown above each lane. Panels show an SDS-PAGE analysis and autoradiogram of viral proteins (indicated by arrows) that were recovered by immunoprecipitation of extracts prepared from the respective cultures. The positions of the molecular mass standards are shown in kilodaltons.

Table 1 shows the influence of IFN upon the calculated half-life (t1/2) of each viral protein examined. In the absence of IFN, HCV NS proteins exhibited t1/2 values ranging from ca. 16 to 18 h (NS3) to 9 to 12 h (NS4B), and the t1/2 values were within the range previously reported by Bartenschlager and coworkers (41). Overall, IFN treatment did not have a significant effect on viral protein stability. However, in the case of NS4B, IFN rendered a reduction in the calculated protein t1/2; this reduction was largely due to the accelerated protein decay that occurred within the first 6 h of IFN treatment. It is important to note that we also observed an IFN-induced decrease in the low-mobility form of NS5A within the first 6 h of IFN treatment (Table 1). This NS5A isoform likely represents the hyperphosphorylated species of NS5A (22). Indeed, we also observed an IFN-induced reduction in the steady-state level of the phospho-NS5A isoform present within both K2040 and L2198S replicon cells (see Fig. 1C). These observations suggest that the stability of the viral NS4B protein might be regulated through the action(s) of ISG products that are synthesized during the early phase of the IFN response and that, similarly, IFN may either induce the destabilization of the phosphorylated form of NS5A, stimulate NS5A dephosphorylation, and/or block an NS5A kinase. Taken together, our results demonstrate an overall stability of the replicon-encoded HCV proteins in vivo. With the noted exception of NS4B and phospho-NS5A, this stability is maintained during IFN treatment.

TABLE 1.

Mean half-lives of HCV replicon NS proteins within cells cultured in the presence or absence of 50 U of IFN-α/mla

| Protein | Mean t1/2 (SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Without IFN | With IFN | |

| NS3 | 18 (2.5) | 16 (2.0) |

| NS4B | 12 (0.8) | 9 (0.8) |

| NS5A | 18 (1.8) | 16 (1.6) |

| NS5A-Pb | 8 (0.9) | 5 (0.7) |

| NS5B | 16 (2.0) | 14 (1.8) |

Cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 30 min, followed by a chase period for various intervals in the presence or absence of IFN-α. Values shown indicate the half-life (in hours) and are inclusive of the data shown in Fig. 3A.

We next examined the potential effect of IFN upon HCV polyprotein processing and protein maturation in the context of HCV RNA replication. Cells (Huh7 control or K2040 replicon cells) were first cultured for 24 h with or without IFN, and then proteins were metabolically labeled by incubating the cultures with [35S]methionine over a 2-h time course in the continued absence or presence of IFN. As seen in Fig. 3B, immunoprecipitation analysis demonstrated that the mature HCV NS3 protein was present in replicon cells within a 10-min labeling period, and protein levels continued to increase over the 2-h time course. The HCV NS3 protein mediates the cleavage events that liberate NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B, and the kinetics of appearance of these proteins is dependent upon accumulation of NS3 (44). In the absence of IFN, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B displayed maturation kinetics that followed the first appearance of the NS3 protein, and each of these proteins began to accumulate within 30 min of labeling. Similar polyprotein processing kinetics were observed within cells cultured in the presence of IFN, although lower overall HCV protein levels were apparent throughout the entire labeling period (Fig. 3B, see lanes 7 to 10). Again, we noted an IFN-induced decrease in the high-molecular-weight isoform of NS5A, suggesting that IFN had a specific effect on the metabolism of phospho-NS5A. Overall, our results demonstrate that IFN does not significantly alter the processing kinetics of the HCV polyprotein but rather induces a specific suppression of HCV protein synthesis. Although we cannot rule out a possible role for phospho-NS5A in regulating HCV replication and/or viral RNA translation, our data largely exclude IFN-induced aberrations in protein processing or stability as major factors that limit HCV replication during the IFN response.

IFN renders a dominant suppression of translation from the HCV IRES.

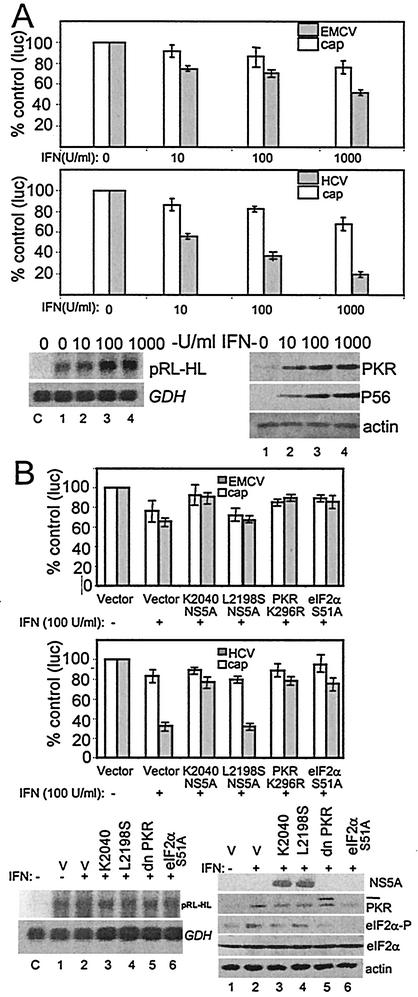

The suppression of viral protein production in HCV replicon cells and the absence of any major effects of IFN upon HCV protein stability or processing indicated that the IFN-induced suppression of viral protein production was mediated through one or more IFN-responsive host translational control processes. Moreover, our results suggested that in cells harboring the K2040 HCV replicon, this translational suppression was likely mediated through PKR-independent mechanisms. We therefore hypothesized that such translational control processes would function by limiting the translational activity of the viral IRES elements encoded within the replicon genome. For example, IFN-induced suppression of HCV IRES function, and the resulting lower levels of neo expression could indirectly render reduced viral protein levels through a general translational suppression that accompanies G418 and/or neomycin drug action in mammalian cells. In addition, IFN-induced programs could directly suppress the production of the HCV polyprotein by limiting the function of the EMCV IRES, which directs the translation of the HCV NS proteins from the HCV replicon genome (see Fig. 1). To examine these possibilities and to determine the role of the PKR-dependent and -independent pathways in regulating HCV and EMCV IRES function, we assessed the translation of luciferase reporter genes from bicistronic expression constructs. Plasmids encoding a 5′ cistron directing the translation of Renilla luciferase from the 5′ cap, followed by a second cistron in which the HCV or EMCV IRES directs the translation of the firefly luciferase gene, were employed to simultaneously assess 5′ cap and viral IRES-dependent translation in Huh7 cells (Fig. 4). Translation from the viral IRES elements exhibited a dose-dependent suppression that exceeded the suppressive effects upon translation directed from the 5′ cap (Fig. 4A). We found that, compared to the translation from the EMCV IRES or 5′ cap, translation from the HCV IRES exhibited a dominant sensitivity to IFN. Analysis of protein expression in transfected cells demonstrated a response to IFN and induction of ISG expression, whereas analysis of RNA levels confirmed that IFN did not affect luciferase mRNA expression (Fig. 4A, lower panel set). These results demonstrate that human liver cells respond to IFN to induce cellular translational control programs that specifically suppress translation from the HCV and EMCV IRES elements.

FIG. 4.

Influence of IFN and the PKR pathway upon HCV and EMCV IRES function. (A) Suppression of IRES function by IFN. Huh7 cells were transfected with the bicistronic plasmid reporter constructs pCMVRluc-EFluc or pRL-HL to simultaneously assess 5′ cap-dependent Renilla luciferase translation (cap) and EMCV IRES (upper panel) or HCV IRES-dependent firefly luciferase translation (middle panel), respectively. Cells were transfected and cultured for 24 h., followed by a 24-h incubation in medium alone or with medium containing increasing amounts of IFN-α. Luciferase activity, protein expression, and RNA levels were assessed from cell extracts. Each panel shows the luciferase values (an average from three experiments) derived from the 5′ cap (open bars) or viral IRES (shaded bars) as a percentage with standard deviations relative to cells cultured without IFN. The lower panel set shows Northern blot analyses of 3.3-kb pRL-HL bicistronic RNA (pRL-HL) and GAPDH (GDH) RNA levels (left) and a representative immunoblot analysis of PKR, P56, and actin protein levels (right) within the cultures corresponding to the pRL-HL transfected cells shown in the middle panel. Lanes show untransfected control cells (denoted as “C” on the Northern blot) or cells transfectedwith pRL-HL that were cultured for 24 h in the absence of IFN (lane 1) or increasing concentrations of IFN (lanes 2 to 4). We also conducted Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from cells that were transfected with pCMVRluc-EFluc, and we confirmed that the corresponding bicistronic luciferase RNA was expressed to similar levels across all conditions (data not shown). (B) The PKR pathway influences IRES translation. Huh7 cells were cotransfected with bicistronic plasmid reporter constructs to simultaneously assess 5′ cap-dependent Renilla luciferase translation (cap) and EMCV IRES (upper panel) or HCV IRES-dependent firefly luciferase translation (middle panel) in the presence of an additional plasmid encoding the vector alone, the NS5A protein from the K2040 or L2198S HCV replicon, PKR K296R, or eIF2α S51A. At 24 h after transfection the culture medium was replaced with DMEM alone (IFN−) or DMEM containing 100 U of IFN-α/ml (IFN+) and, after an additional 24 h, the cells were harvested and extracts were subjected to the dual luciferase assay. Bars show the percentages of the luciferase levels relative to the values obtained from cultures cotransfected with the vector control (an average and standard deviation from three experiments) derived from 5′cap-dependent translation (open bars) or viral IRES-dependent translation (shaded bars). The lower panel set shows Northern blot analysis of the pRL-HL bicistronic luciferase RNA (pRL-HL) and GAPDH (GDH) RNA levels (left panel) and immunoblot analyses of NS5A, PKR, phospho-eIF2α (eIF2α-P), total eIF2α, and actin levels (right panel) in extracts derived from cells that were cotransfected with pRL-HL and expression constructs encoding the vector control (lanes 1 and 2), K2040 NS5A (lane 3), L2198S NS5A (lane 4), PKR K296R (lane 5; the hash mark denotes the position of HA-PKR K296R), or eIF2α S51A (lane 6), either treated or not treated with IFN as indicated. “C” (left panel set) denotes untransfected control cultures. In similar analyses, we confirmed that equal RNA and protein levels were present in cells cotransfected with pCMVRluc-Efluc (data not shown).

To determine the role of the PKR pathway in the IFN-induced suppression of HCV and EMCV IRES function, we conducted luciferase translation experiments in cells cotransfected the bicistronic reporter plasmids and mutant PKR or eIF2α. In addition, we assessed the potential role of the NS5A protein, derived from the K2040 or L2198S HCV replicons, to regulate translation from the HCV replicon IRES elements. In control cells cotransfected with the vector alone, IFN induced a specific suppression of luciferase production from the HCV or EMCV IRES elements (Fig. 4B). We observed a partial rescue of both cap-dependent and IRES-dependent luciferase production in IFN-treated cells expressing the NS5A protein from the K2040 replicon. However, no significant rescue of luciferase production was observed in IFN-treated cells expressing the L2198S NS5A protein.

The partial rescue to IRES function by the K2040 NS5A protein, coupled with the actions of this protein as a PKR inhibitor (see reference 40 and Fig. 1B), suggested that IFN might regulate IRES function through mechanisms that involve PKR. We investigated this possibility by examining luciferase production in cells that were cotransfected with the respective bicistronic reporter construct and dominant-negative PKR mutant (PKR K296R) (25) or a S51A mutant of eIF2α that lacks the phosphorylation site required to mediate PKR-dependent translational control (7). Although coexpression of these mutant constructs stimulated cap-dependent translation, each had a differential effect on HCV and EMCV IRES function in IFN-treated cells (Fig. 4B). In particular, a nearly complete rescue of luciferase production from the 5′ cap or the EMCV IRES from IFN was achieved through expression of K2040 NS5A, mutant PKR, or eIF2α. In contrast, expression of these constructs rendered only a partial rescue of luciferase production from the HCV IRES, which remained insensitive to increased amounts of the transfected plasmids (data not shown). We confirmed that luciferase RNA was expressed to similar levels in all conditions and that NS5A and mutant PKR and eIF2α were efficiently expressed (Fig. 4B, lower panel set). These results demonstrate that the PKR pathway plays a role in mediating the translational-suppressive action of IFN upon the HCV and EMCV IRES elements and that the PKR-regulatory actions of NS5A can partially rescue the HCV IRES from the antiviral actions of IFN. Moreover, this work identifies important distinctions in the mechanisms of IFN action against HCV and EMCV IRES translation to indicate that the PKR pathway is the primary mediator of IFN action against EMCV IRES function. In contrast, the partial rescue of HCV IRES function conferred by the K2040 NS5A protein, mutant PKR or S51A eIF2α indicates that IFN action against this IRES is only partially dependent upon the PKR pathway and likely involves other PKR-independent mechanisms of translational control.

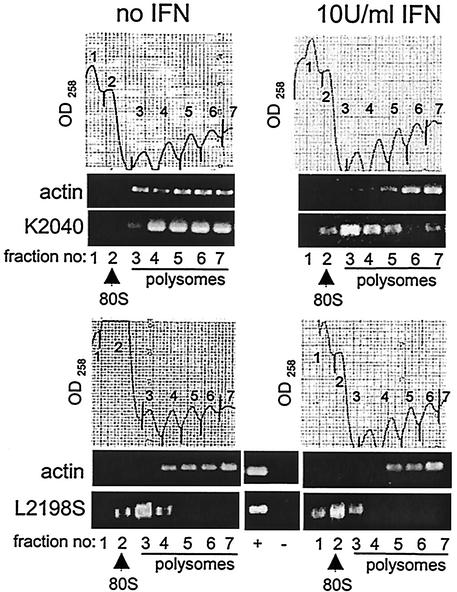

IFN disrupts the recruitment of the HCV RNA into polyribosome complexes in vivo.

To confirm these results and to determine the effects of IFN action upon translation of the HCV replicon genome in the context of actual viral RNA replication, we examined the ribosomal recruitment and distribution of the HCV replicon RNA in vivo. Huh7 cells harboring the HCV replicon K2040 or L2198S quasispecies were cultured for 24 h in the absence or presence of IFN, after which cell extracts were prepared and fractionated by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation. This procedure efficiently separates ribosomal subunits and ribosome-RNA complexes by order of increasing complexity (46). We note that although this analysis will not define the separate contributions of the HCV or EMCV IRES elements upon the recruitment of ribosomes onto the HCV replicon genome, it does allow us to globally examine the overall efficiency of viral RNA-ribosome association in the context of HCV RNA replication. We examined the association of HCV replicon RNA and β-actin (control) mRNA within individual fractions recovered from the gradient fractionation procedure. A marked difference was observed in the polyribosome distribution of the K2040 and L2198S replicon RNA genomes. As shown in Fig. 5 (compare the upper and low panel sets), in the absence of IFN the K2040 genome was predominantly associated with high-molecular-weight polyribosomes. In contrast, the L2198S genome was associated mainly with monoribosome and only low-molecular-weight polyribosome complexes. This difference in ribosome association paralleled the differential protein synthetic rates of the HCV replicon quasispecies (see Fig. 2). IFN treatment induced a shift of the K2040 HCV replicon genome from high-molecular-weight polyribosome complexes into lower-molecular-weight polyribosome and monoribosome complexes. Similarly, IFN induced a shift of the L2198S genome from association with low-molecular-weight polyribosomes to a predominant association with unassembled ribosomal subunits or a monoribosome complex (Fig. 5, compare right panel sets). IFN did not significantly impact the distribution of β-actin mRNA, which remained associated with polyribosomes in all conditions. These results demonstrate that IFN treatment specifically alters the translation efficiency of the HCV replicon RNA in vivo by inducing a redistribution or dissociation of the HCV RNA within the ribosome pool. In the absence of IFN the reduced levels of PKR activity in cells harboring the K2040 replicon corresponded with an enhanced HCV RNA basal translation efficiency and polyribosome association compared to the distribution of the L2198 replicon genome. This, along with the high levels of PKR activity and eIF2α phosphorylation within L2198S replicon cells and the correspondingly low translation efficiency of this replicon genome, provides strong evidence that the PKR pathway plays a role in regulating viral genome translation during HCV RNA replication. However, these results demonstrate that despite virus-directed inhibition of the PKR pathway within K2040 replicon cells, the polyribosome distribution of this replicon genome was partially sensitive to IFN action and resulted in a dissociation of high-molecular-weight polyribosome-HCV RNA complexes. Overall, our results indicate that IFN induces cellular pathway(s) of translational control that function in parallel with but independently of PKR to limit HCV RNA translation.

FIG. 5.

Polyribosome distribution analysis. Huh7 cells harboring the K2040 or L2198S HCV replicon were cultured for 24 h alone (no IFN; left panel sets) or in the presence of 10 U of IFN-α/ml (right panel sets). Cell extracts were prepared and fractionated by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation, and fractions were collected while the optical density at 258 nm (OD258) was monitored. The gradient distribution of β-actin mRNA and HCV replicon RNA was assessed by semiquantitative RT-PCR of an equal volume of total RNA isolated from each fraction. The OD258 profile and RT-PCR analysis for the fractionation procedures are shown. In each case the gradient positions of the 80S ribosome and polysomes are indicated and were confirmed by assessing the rRNA distribution pattern within the gradient fractions (data not shown). Fraction numbers shown below each lane of the RT-PCR panels correspond to the numbers shown on the associated OD258 profile. “+” and “−” indicate PCR plasmid control and a control RT-PCR of template RNA without the RT step. The results shown are representative of three separate experiments.

P56 suppresses viral IRES translation through in vivo association with HCV RNA-translation initiation complexes.

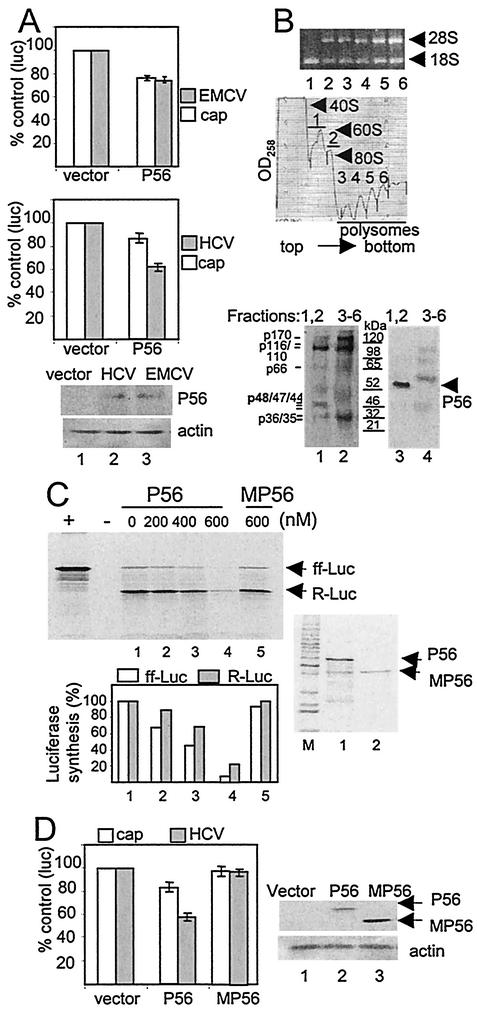

The IFN-induced, PKR-independent redistribution of HCV RNA into low-molecular-weight polyribosome complexes prompted us to examine the role of other IFN-responsive cellular pathways of translational control. We identified a basal level of P56 expression within cells harboring the L2198S replicon that was not apparent in K2040 replicon cells (see Fig. 1C). This basal level of P56 expression was consistent with our previous observations that HCV RNA replication can induce a cellular antiviral state (8, 40) and suggested that the translational suppressive actions of P56 could in part be responsible for the poor basal translation efficiency and low replication levels of the L2198S HCV replicon. To address this possibility, we characterized the effects of P56 expression upon 5′ cap-dependent and HCV or EMCV IRES translation within Huh7 cells. As shown in Fig. 6A, in the absence of IFN treatment the forced expression of P56 resulted in a dominant suppression of translation directed by the HCV IRES. P56 expression had less of an effect upon both cap-dependent and EMCV IRES translational activity. In the context of IFN and the HCV replicon this suggests that P56 may suppress HCV RNA replication by disrupting IRES-directed translation independently of PKR, perhaps through interactions with eIF3 and the translation initiation complex (18).

FIG. 6.

Polysome distribution of P56 and eIF3 proteins, and analysis of P56 action on viral IRES function. (A) Regulation of viral IRES function by P56. Huh7 cells were cotransfected with vector alone or a P56 expression plasmid and the pCMVRluc-EFluc or pRL-HL bicistronic luciferase reporter construct to simultaneously assess 5′ cap-dependent Renilla luciferase translation (cap; open bars) and EMCV IRES (shaded bars; upper panel) or HCV IRES-dependent firefly luciferase translation (shaded bars; middle panel), respectively, in the presence of P56 expression. Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection, and cell extracts were subjected to luciferase assay and immunoblot analysis. In addition, total RNA was extracted from an aliquot of each culture to assess luciferase mRNA levels, which were similar in all cultures (data not shown). The upper and middle panels show the average and standard deviation luciferase expression levels derived from three independent experiments and are presented as a percentage of the control cultures that were cotransfected with an empty expression vector. The lower panel set shows an immunoblot of P56 and actin protein levels expressed in extracts prepared from the cul-tures that were cotransfected with pRL-HL and vector alone (lane 1), pRL-HL and the P56 expression plasmid (lane 2), or pCMVRluc-EFluc and the P56 expression plasmid (lane 3). (B) P56 is codistributed with the p48 subunit of eIF3. Proteins were extracted from the indicated fractions recovered from the polyribosome fractionation procedure depicted in the rRNA gel and OD258 profile (upper panels). For these experiments the fractions were collected in the absence of proteinase K. The top panel shows rRNA within equal volumes of total RNA isolated from the sucrose gradient fractions numbered below each lane, and fractions correspond the peaks depicted in the OD258 profile (middle panel). Proteins isolated from fractions containing the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits and 80S monosomes (fractions 1 and 2) or those isolated from polyribosome fractions (fractions 3 to 6) were pooled. A total of 25 μg of each protein pool was separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis. The lower panels show the same blot that was first probed with antiserum against eIF3 (left panel), stripped, and then reprobed with antiserum to P56 (right panel). Lanes of each panel correspond to proteins pooled from fractions 1 and 2 (lane 1) or fractions 3 to 6 (lane 2). The positions of P56 and the eIF3 subunits are indicated. p48 is indicated in boldface. Molecular mass standards are shown in kilodaltons. (C) Functional analysis of P56 on HCV IRES translation in vitro. Rabbit reticulocyte lysates were incubated with increasing nanomolar amounts of purified recombinant P56 or MP56 in the presence of [35S]methionine and equal amounts of in vitro-transcribed RNA generated from the bicistronic pRL-HL construct. The pRL-HL RNA directs Renilla and firefly luciferase translation from the 5′ cap and HCV IRES, respectively. Equal volumes of the translation products were resolved on SDS-PAGE. The upper panel shows an autoradiogram of the dried gel. The positions of firefly (ff-Luc) and Renilla (R-Luc) luciferase are shown. “+” and “−” denote control translation reactions programmed with RNA encoding firefly luciferase or with buffer only, respectively. The level of Renilla (shaded bars) and firefly luciferase translation products (open bars) in lanes 1 to 5 were quantified by phosphorimager analysis and are presented as a percentage of the lane 1 translation reaction, which was conducted in the absence of P56. The right panel shows an image from a Coomassie blue-stained gel containing resolved aliquots of purified recombinant P56 and MP56 preparations that were used in the translation reactions. The results were reproduced in three separate experiments. (D) Functional analysis of P56 on HCV IRES translation in vivo. Huh7 cells were cotransfected with pRL-HL and either an empty control expression vector or an expression plasmid encoding P56 or MP56. After 24 h the cells were harvested, and extracts were subjected to luciferase assay and immunoblot analysis. The left panel shows the average and standard deviation (obtained from three independent experiments) of 5′ cap-dependent (open bars) and HCV IRES-dependent luciferase values (shaded bars) expressed as a percentage of the values derived from cultures cotransfected with the vector control. The right panel set shows P56, MP56, and actin expression within the corresponding cell extracts. Expression of P56 resulted in an average 35% reduction in HCV IRES translation.

To further characterize the potential role of P56 in suppressing HCV RNA replication, we examined the ribosome-associated protein constituents for the presence of P56 and eIF3 within pooled sucrose gradient fractions of extracts prepared from IFN-treated cells harboring the K2040 HCV replicon. As shown in Fig. 6B (upper panels), analysis of the rRNA pattern within the sucrose gradient fractions confirmed that the ribosomal subunits and 80S monosome (translation initiation complexes) were distributed within fractions 1 and 2, respectively, whereas fractions 3 to 6 contained polyribosome complexes representing both initiation and elongation complexes. As expected, the eIF3 subunits were present within both pooled fractions, reflecting the critical role of this factor in the translation initiation process (Fig. 6B, lower left panel) (35). However, a polypeptide corresponding to the expected size of the p48 subunit of eIF3 was highly enriched within pooled fractions containing predominantly translation initiation complexes (3). When the same blot was probed with P56 antiserum, we detected a strong P56 band that was localized specifically within fractions 1 and 2 containing the p48 subunit of eIF3. P56 was not present in pooled fractions 3 to 6 containing polyribosome complexes. These results are in accordance with previous in vitro and in vivo studies that demonstrated the physical interaction, cofractionation, and colocalization of P56 with the p48 subunit of eIF3 (18). Taken together, our results extend this work to indicate that (i) P56 can suppress RNA translation, possibly through mechanisms that involve interaction with eIF3 within the active translation initiation complex, and that (ii) P56 plays an important role in mediating the antiviral actions of IFN against HCV RNA replication by suppressing IRES function. Moreover, our results demonstrate that P56 can partially suppress translation directed from 5′ cap or the EMCV IRES (Fig. 6A). Thus, disruption of eIF3 function by P56 may represent an effective strategy that functions in parallel with but independent of PKR to contribute to the translational suppressive actions of IFN.

Suppression of HCV IRES function requires the p48-binding properties of P56.

With respect to the HCV IRES, previous work has demonstrated that this translation element is critically dependent upon a direct recruitment of eIF3 and that, with the exception of ribosomal subunits, it does not require other canonical translation initiation factors for directing viral protein synthesis (39). We therefore assessed the relative sensitivity of cap-dependent and HCV IRES translation to the suppressive actions of P56. In addition, we assessed the role of the p48-P56 interaction in P56-mediated translational regulation. In vitro translation reactions were conducted in the presence or absence of recombinant purified P56 or mutant P56 (MP56) with a C-terminal truncation that abolishes the interaction with p48 (18). Rabbit reticulocyte lysates were programmed with capped RNA generated in vitro from the bicistronic pRL-HL construct directing 5′ cap-dependent Renilla luciferase translation and HCV IRES-dependent firefly luciferase translation (Fig. 6C). Translation reactions conducted in the presence of buffer alone revealed that in this system cap-dependent translation was overall more robust than translation directed by the HCV IRES, and we observed an approximate 10:1 ratio of cap-IRES translation of the luciferase products (Fig. 6C, upper panel, lane 1). Titration of wild-type P56 into the translation reaction resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in translation that demonstrated an increased sensitivity of the HCV IRES to P56 action over cap-dependent translation, and translation was globally suppressed under the highest concentration of P56. In contrast, translation was insensitive to high concentrations of MP56 (see Fig. 6C, upper and middle panels). In fact, we failed to observe any translational effects imposed by mutant P56 even at protein concentrations that exceeded 1 μM (data not shown).

To confirm and extend these results, we compared the impact of P56 or MP56 expression upon 5′ cap and HCV IRES translation in Huh7 cells. Consistent with our in vitro observations, we found that expression of MP56 had no effect on luciferase production from the 5′ cap or HCV IRES (Fig. 6D), whereas the expression of wild-type P56 rendered a dominant suppression of luciferase production from the HCV IRES in Huh7 cells. We confirmed that luciferase RNA expression was similar in the transfected cells (data not shown). These results demonstrate that P56 can suppress translation mediated from the HCV IRES and that intracellular P56 action requires p48-binding function. We conclude that P56 plays an important role in mediating IFN action against HCV replication, possibly through interactions with eIF3 that regulate HCV IRES function.

DISCUSSION

HCV infection is currently treated with IFN-based therapy, either alone or in combination with ribavirin (32). Mathematical models derived from examining viral dynamics within HCV-infected patients undergoing IFN therapy propose that IFN exerts its antiviral effects at two levels that involve an acute block in de novo virus production and potentiation of infected cell death (36). In the present study we used the HCV replicon system to characterize the mechanisms by which IFN limits HCV replication. Our results demonstrate that IFN induces cellular programs that predominantly target viral protein synthesis to thereby limit HCV RNA replication. Consistent with the proposed model of IFN action in vivo, our results project that, in addition to limiting the components required for viral genome replication, the therapeutic disruption of viral protein synthesis within HCV-infected patients undergoing IFN treatment would be expected to block de novo virus production by imposing limitations upon components required for virion assembly. Overall, our results support a model in which IFN limits HCV replication and virus production, in part, by imposing a translational blockade to viral protein synthesis. Our study also demonstrates that, similar to HCV in vivo, quasispecies diversity within the HCV replicon system can impact IFN sensitivity of viral RNA replication in cultured cells. Consistent with previous reports (17), we found that the HCV RNA replicon can persist and replicate, albeit at a low level, in the presence of continuous high-dose IFN exposure (C. Wang and M. Gale, Jr., unpublished observations). These results warrant caution when assigning IFN sensitivity to the HCV replicon system and suggest that certain quasispecies of the HCV replicon can partially resist IFN pressure in cell culture.

IFN imposes a translational block on HCV RNA replication.

Metabolic labeling of cells harboring distinct HCV RNA replicon quasispecies revealed that IFN imposes a major translational-suppressive effect upon the HCV RNA without significantly reducing global cellular mRNA translation. Moreover, the effects of IFN were specific to HCV RNA translation and did not significantly impact HCV polyprotein processing or viral protein stability. In the case of the NS4B protein, we did observe an increased rate of decay early after IFN administration, which stabilized at later time points (Table 1). IFN may therefore transiently induce immediate-early events that target NS4B for degradation to possibly contribute to the immediate decline in viral load observed after IFN administration in vivo (36). We also observed a more rapid decay of the high-mass species of NS5A in IFN-treated cells. This species of NS5A likely represents the hyperphosphorylated protein isoform that previous studies have shown to be more labile in general (41). Thus, this NS5A isoform is particularly sensitive to IFN, which may destabilize the protein, induce its dephosphorylation, or block the actions of an NS5A protein kinase (45). The role of NS5A phosphorylation in HCV RNA replication remains obscure, and mutation of the various phosphorylation sites has shown little overall impact on viral RNA replication (5). Consistent with this, significant differences in phospho-NS5A stability were not observed between the cells harboring the K2040 or L2198S HCV replicon variants, although we did observe major differences in viral RNA translation and replication efficiency. However, since IFN suppressed the replication of both replicon variants concomitantly with a reduction in phospho-NS5A levels, we cannot exclude a role for the phospho-NS5A isoform in modulating the host response to IFN.

The PKR pathway impacts overall HCV RNA translation efficiency and is modulated by NS5A.

Our examination of the effects of IFN upon HCV replicons encoding functionally distinct NS5A variants that confer inhibition or activation of PKR during viral RNA replication has revealed that IFN influences the rate of viral protein production by directing PKR-dependent and PKR-independent translational control programs in the host cell. Our previous work has demonstrated that the L2198S mutation in NS5A, which is located adjacent to the PKR-binding domain (9), abolishes the potential PKR-regulatory function of this protein, most likely by impacting the PKR-binding properties of NS5A and/or affecting the protein's subcellular localization (40). Our analysis of cells harboring the L2198S replicon has revealed that, similar to the replication of other positive-strand RNA viruses, HCV RNA replication has the potential to activate PKR, leading to increased levels of eIF2α phosphorylation even in the absence of exogenous IFN. Thus, it is likely that dsRNA structures within the HCV genome or replication intermediates can act as PKR activator RNAs. Accordingly, we found that in the absence of exogenous IFN protein synthesis from the L2198S HCV replicon was inefficient, and this viral RNA was predominantly associated with only monoribosome complexes in vivo. Moreover, this replicon RNA exhibited an increased rate of RNA decline during IFN treatment compared to the K2040 HCV replicon RNA. We therefore conclude that translational control through NS5A regulation of PKR activity is an important determinant of basal HCV RNA replication efficiency, sensitivity to IFN, and overall viral fitness. Along with the aforementioned results, we base this conclusion on the following observations: (i) Cells harboring the K2040 HCV replicon, whose NS5A protein is an effective inhibitor of PKR (40), exhibited only very low levels of PKR activity and eIF2α phosphorylation, and this replicon variant directed robust levels of viral protein synthesis, was associated with polyribosome complexes in vivo, and replicated very efficiently; (ii) IFN suppressed HCV IRES and EMCV IRES-driven reporter activity in vivo, and this suppression was partially rescued by expression of the K2040 NS5A protein, dominant-negative mutant PKR, or an S51A mutant of eIF2α that lacks the PKR phosphorylation site. Taken together, these observations demonstrate that the sequence of NS5A is an important viral determinant that can control the PKR-regulatory pathway and that mutations that alter the PKR-binding properties of NS5A may impact overall viral translation efficiency.

Several other groups have suggested a role for NS5A in supporting HCV replication through mechanisms that involve PKR or that can function independently of PKR (reviewed by Tan and Katze [53]). Shimotohno and coworkers (37) recently reported that the HCV NS5A protein could complement and enhance virus replication by binding and inhibiting PKR, a finding consistent with our current study. Moreover, He et al. demonstrated that NS5A could complement a vaccinia virus mutant lacking the E3L protein (20), a well-characterized PKR inhibitor. In this case complementation was attributed to NS5A inhibition of PKR and enhancement of viral mRNA translation. These reports and the current study present further positive data to demonstrate that NS5A can function as a PKR inhibitor in the context of virus replication. It is important to note that NS5A can also antagonize the actions of IFN through mechanisms that do not impact translational control pathways but rather impinge upon specific signal transduction processes (53). For example, the expression of certain NS5A quasispecies can limit the antiviral properties of IFN by modulating ISG expression (15) and inducing the expression of interleukin-8 (43), a known IFN antagonist. Our analyses revealed that Huh7 cells harboring HCV replicon quasispecies or expressing NS5A constructs were still able to respond to IFN overall. However, these results do not exclude a role for NS5A in disrupting IFN signaling processes in parallel with perturbing translational control mechanisms. Our results do show that, in the context of HCV RNA replication, inhibition of PKR-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation was associated with enhanced recruitment of viral RNA into polyribosome complexes. This suggests that translation of the HCV replicon RNA is sensitive to eIF2α phosphorylation levels and that NS5A can function as a positive effector of HCV translation.

A recent report by Kato and coworkers presented evidence that IFN exerts suppressive effects on both cap-dependent and HCV IRES translation in which these effects are comparably dominant on the HCV IRES (23). Consistent with our own results, it was found that study that the expression of a nonfunctional PKR mutant could stimulate translation in Huh7 cells to partially relieve the translational-suppressive actions of IFN. However, this stimulation was global and was not specific to the HCV IRES. Koev et al. recently reported that IFN only had minor suppressive effects upon HCV IRES function and that these effects were independent of increased levels of eIF2α phosphorylation (28). Since the observations in the present study demonstrate that expression of the K2040 NS5A protein or mutants of PKR or eIF2α could only partially rescue HCV IRES translation from IFN suppression, we interpret the collective results from these studies to indicate that PKR plays a role in the IFN-mediated suppression of HCV IRES translation and that PKR-independent processes are responsible for the dominant inhibition of HCV IRES function that is induced by IFN. In addition, others have suggested that the La autoantigen, an HCV IRES-binding protein, may play a role in the PKR-independent actions of IFN. Analysis of La expression revealed that exposure of cells to IFN or dsRNA resulted in a marked decrease in La protein levels (49). Thus, IFN may attenuate HCV IRES translation, in part, by limiting the amount of La, which has been identified as a translation stimulator (reviewed in reference 13). Moreover, our work now identifies the IFN-stimulated P56 protein as an effector of PKR-independent IFN action that impacts viral RNA translation (discussed below). Overall, these results indicate that PKR-independent processes function in parallel with the PKR pathway to limit HCV translation during the host response to IFN.

P56 contributes to IFN-induced suppression of HCV RNA replication by disrupting viral IRES function independently of the PKR pathway.