Abstract

Background

The natural course of onset of cigarette use has been conceptualized as progressing sequentially through 5 stages (preparation, trying, irregular use, regular use, nicotine-dependent smoking). However, recent studies suggest that symptoms of nicotine dependence can occur early in the onset process, raising questions about the validity of this model. The objective of our study was to describe the sequence and timing of 12 milestones (6 related to cigarette use and 6 to symptoms of nicotine dependence) during onset of cigarette use.

Methods

Grade 7 students in 10 secondary schools in Montréal (n = 1293) were followed prospectively every 3–4 months for 5 years. Using Kaplan–Meier analysis, we computed the number of months after first puff at which the cumulative probability of attaining each milestone was 25%, among 311 participants who initiated cigarette use during follow-up.

Results

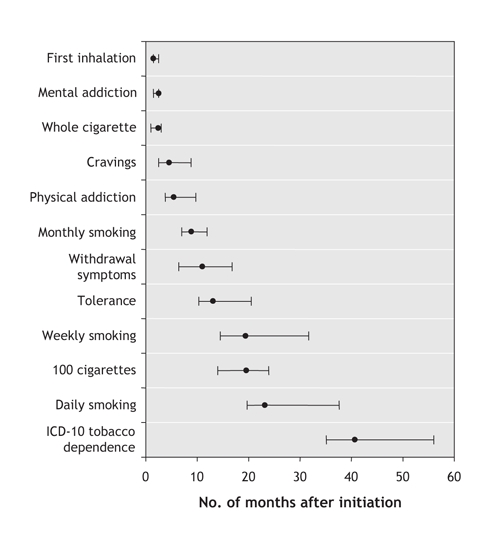

Inhalation rapidly followed first puff. The cumulative probability of inhalation was 25% at 1.5 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5–2.5). The cumulative probability (and 95% CI) was 2.5 months (1.5–2.5) for mental addiction, 2.5 (1.0–3.0) for smoking a whole cigarette, 4.5 (2.5–8.8) for cravings, 5.4 (3.8–9.7) for physical addiction, 8.8 (7.0–11.9) for monthly smoking, 11.0 (6.4–16.8) for withdrawal symptoms, 13.0 (10.3–20.5) for tolerance, 19.4 (14.5–31.7) for weekly smoking, 19.5 (14.0–23.9) for lifetime total of 100 cigarettes, 23.1 (19.7–37.6) for daily smoking and 40.6 (35.1– 56.0) for conversion to tobacco dependence.

Interpretation

Symptoms of nicotine dependence develop soon after first puff and can precede monthly, weekly and daily smoking. Cessation interventions that manage dependence symptoms may be needed soon after first puff.

Formal evaluations of many prevention programs targeted to youth show little or no long-term impact in preventing cigarette use,1,2 and programs to help young smokers quit have had limited success to date.3,4 The lack of sustained impact of tobacco control programs for youth, and the unanticipated reverse effects,5 may result from an incomplete understanding of how and why young people initiate smoking. Increased insight into the early natural course of onset of cigarette use in adolescence may enable the development of more relevant and effective tobacco control programs for youth.

The natural course of smoking onset in adolescence is usually conceptualized as progressing sequentially through distinct stages, beginning with a preparation period, during which interest in smoking is established, and ending with physiologic dependence.6–9 Progression from first puff to daily use is thought to take 2–3 years; progression to nicotine-dependent smoking is thought to take longer.10 However, several recent reports11–14 suggest that symptoms of nicotine dependence can occur early in the onset process, which raises questions about the validity of this sequential staged model. There is concern that early symptoms of nicotine dependence may contribute to continued smoking.

More studies are needed to describe the early natural course of onset of cigarette use from first puff, in order to characterize milestones such as first time inhaling smoke into the lungs, first time smoking a whole cigarette and first time experiencing symptoms of nicotine dependence. This information could provide stronger underpinnings for better informed tobacco control strategies for youth. The objectives of this analysis were to describe the temporal sequence of attaining selected milestones in the natural course of onset of cigarette use and, more specifically, the time interval between smoking initiation and each of these milestones.

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of McGill University's Faculty of Medicine, Montréal. Parents of participants provided written informed consent, and participants provided assent. Data were drawn from the McGill University Study on the Natural History of Nicotine Dependence in Teens, a prospective investigation involving 1293 students, recruited from among all grade 7 classes in a convenience sample of 10 Montréal-area secondary schools.13

Baseline data were collected in self-report questionnaires in the fall of 1999, and follow-up data were collected at 3–4 month intervals over the next 5 years. Copies of the study questionnaire are available online in English (Appendix 1) and French (Appendix 2) at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/175/3/255/DC1. About half (55.4%) of the eligible students participated at baseline. Nonparticipation was due to student reluctance to give a blood sample (for genotyping) and to a provincial labour dispute that resulted in some teachers refusing to collect consent forms. For our analysis, we included only those participants who reported that they had never smoked at baseline and who initiated cigarette smoking in any of the 19 follow-up survey cycles.

We used data on lifetime smoking to identify participants who reported at baseline that they had never smoked and who initiated cigarette smoking during follow-up. In each survey cycle, lifetime smoking was measured with the question “Have you ever in your life smoked a cigarette, even just a puff (drag, hit, haul)?” (No; Yes, 1 or 2 times; Yes, 3 or 4 times; Yes, 5 to 10 times; Yes, more than 10 times). Among 1293 students who participated in the baseline data collection, 814 had never smoked (not even a puff). Of these 814, 352 (43.2%) initiated smoking during follow-up (herein referred to as “initiators”), as measured by any affirmative response to the lifetime smoking question.

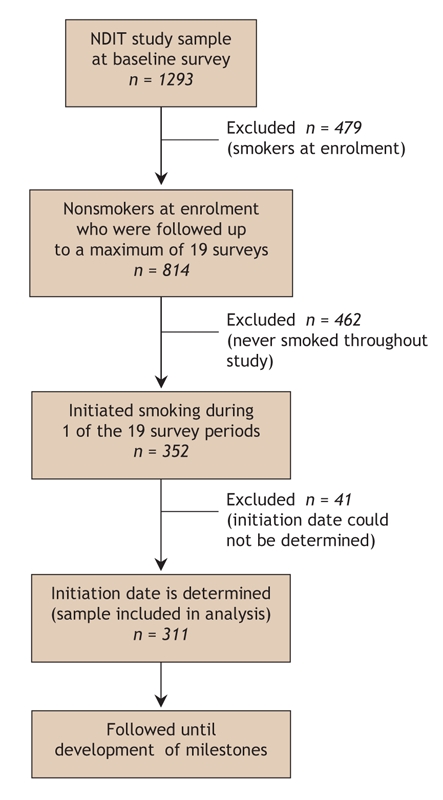

On the follow-up questionnaires, participants reported data on cigarette smoking during the 3 months preceding each questionnaire, including the number of days during each month that the subject had smoked and the number of cigarettes smoked per day on average during that month. Three-month test–retest reliability for these 2 items was good (kappa value 0.78 and 0.75, respectively).15 For 253 of the 352 initiators, time (day/month/year) of first puff was designated as the midpoint of the month during which the respondent first reported smoking cigarettes in the 3-month recall. For initiators who did not report smoking cigarettes in the 3-month recall, time of first puff was designated as the date of data collection in which lifetime use was first reported (n = 25) or the midpoint of the year preceding the questionnaire in which they reported smoking in the past year in the self-perceived smoking status item (n = 33). Self-perceived smoking status was measured with the item “Check the one box that describes you best” (I have never smoked a cigarette, even just a puff; I have smoked cigarettes, even just a puff, but not at all in the past 12 months; I smoked cigarettes once or a couple of times in the past 12 months; I smoke cigarettes once or a couple of times each month; I smoke cigarettes once or a couple of times each week; I smoke cigarettes every day). A total of 41 initiators were excluded from the analysis because time of first puff could not be determined, which left 311 initiators eligible for inclusion in this analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Flow of participants through the study. NDIT = McGill University Study on the Natural History of Nicotine Dependence in Teens.

At each survey cycle following initiation, attainment of 12 events (milestones) related to either cigarette use (6 items) or to experiencing symptoms of nicotine dependence (6 items) was assessed. Of the 6 indicators of cigarette use, 5 indicators (first inhalation, monthly, weekly and daily smoking, and lifetime consumption of 100 cigarettes) have been used in surveys on smoking in youth16,17 or in studies on initiation of smoking in youth.11–14 Lifetime consumption of 100 cigarettes is commonly used to define the point at which smoking becomes established, and numerous studies only test cessation interventions among participants who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.3,4 The 6 milestones describing symptoms of nicotine dependence were the most frequently reported symptoms among novice smokers in an earlier analysis of this database13 and are components of current diagnostic criteria for nicotine dependence in the DSM-IV18 and ICD-10.19 The 6 milestones related to cigarette use included:

• Time of first inhalation: the survey date on which the participant first indicated ever taking cigarette smoke into his or her lungs for more than one puff

• Time of first whole cigarette: survey date on which the participant first reported ever smoking a whole cigarette (down to or close to the filter)

• Time of first monthly smoking: survey date on which the participant first responded “I smoke cigarettes once or a couple of times each month” in the self-perceived smoking status item

• Time of first weekly smoking: survey date on which the participant first responded “I smoke cigarettes once or a couple of times each week” in the self-perceived smoking status item

• Time of first daily smoking: survey date on which the participant first responded “I smoke every day” in the self-perceived smoking status item

• Time of first lifetime consumption of 100 cigarettes: survey date on which the participant first responded Yes to the question “Have you smoked 100 or more whole cigarettes in your life? (100 cigarettes = 4 packs of 25)”

The 6 milestones related to symptoms of nicotine dependence were as follows:

• Time of first self-report of physical addiction: survey date on which the participant first responded “a little,” “quite” or “very” to the question “How physically addicted to smoking cigarettes are you?” (Not at all; A little; Quite; Very)

• Time of first self-report of mental addiction: survey date on which the participant first responded “a little,” “quite” or “very” to the question “How mentally addicted to smoking cigarettes are you?” (Not at all; A little; Quite; Very)

• Time of first symptom of tolerance: survey date on which the participant first responded “a bit true” or “very true” to the statement “Compared to when I first started smoking, I can smoke much more now before I start to feel nauseated or ill” (Not at all true; A bit true; Very true)

• Time of first craving: survey date on which the participant first responded Yes to the question “Do you ever have cravings to smoke cigarettes? (No; Yes)

• Time of first withdrawal symptom: survey date on which the participant first responded “rarely,” “sometimes” or “often” to the question “Now think about the times when you have cut down or stopped using cigarettes or when you haven't been able to smoke for a long period (like most of the day). How often did you experience feeling a strong urge or need to smoke?” (Never; rarely; sometimes; often)

• Time of conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence: survey date on which the participant first met 3 or more of the 6 ICD-10 criteria for tobacco dependence.19 The development, as well as the psychometric properties, of our measure of ICD-10 tobacco dependence for adolescents has been described previously.20

Data on the first 2 milestones of nicotine-dependence symptoms — mental and physical addiction — were collected in all survey cycles from all respondents whether or not they reported smoking cigarettes. These items were developed based on earlier qualitative work in which adolescents were asked to describe their experiences of nicotine dependence and were able to distinguish between what they perceived to be mental and physical addiction.21 Data on the remaining 4 milestones were collected in each survey cycle, but only among subjects who reported smoking cigarettes in the 3 months preceding the questionnaire. The test–retest reliability and the convergent construct validity of several of these indicators were tested in earlier work and are uniformly excellent.20

We described the natural course of onset of cigarette use among the 311 initiators in terms of the cumulative probability of having attained the milestone of interest according to time in months from smoking initiation (first puff). Probabilities were computed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, which is the method of choice when the length of follow-up differs between respondents and when censoring occurs (i.e., when a participant is lost to follow-up or reaches the end of the study without having experienced the milestone). The Kaplan–Meier curve is interpreted as the cumulative probability that the milestone of interest has occurred by a particular point.

We repeated this analysis for 3 subgroups of initiators: the subjects who had inhaled into their lungs (n = 253), the subjects who smoked a whole cigarette (n = 214) and the subjects who had experienced cravings (n = 141). We hypothesized that the temporal sequence of, and time interval between, milestones might differ in these subgroups.

Results

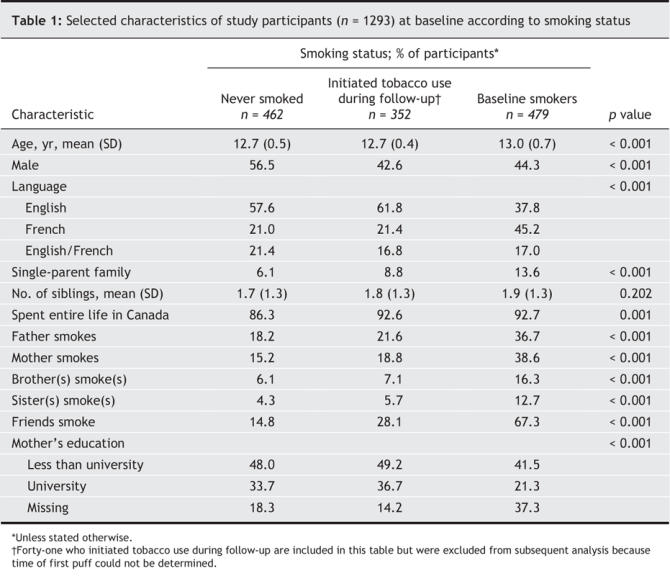

Among the 311 participants included in our analysis who initiated cigarette smoking during follow-up (initiators), the median length of follow-up from collection of baseline data was 53 months (range 5–56 months), and the median length of follow-up from first puff was 31 months (range 0–54 months). The characteristics of the 311 initiators were similar to those of participants who reported having never smoked; however, they differed from the characteristics of participants who reported current or past cigarette smoking at baseline (i.e., baseline smokers) in age, language spoken, family characteristics, and family members' and friends' smoking status. (Table 1). The characteristics of the 41 initiators excluded from our analysis were similar to those of the 311 included in the analysis.

Table 1

Attainment of milestones

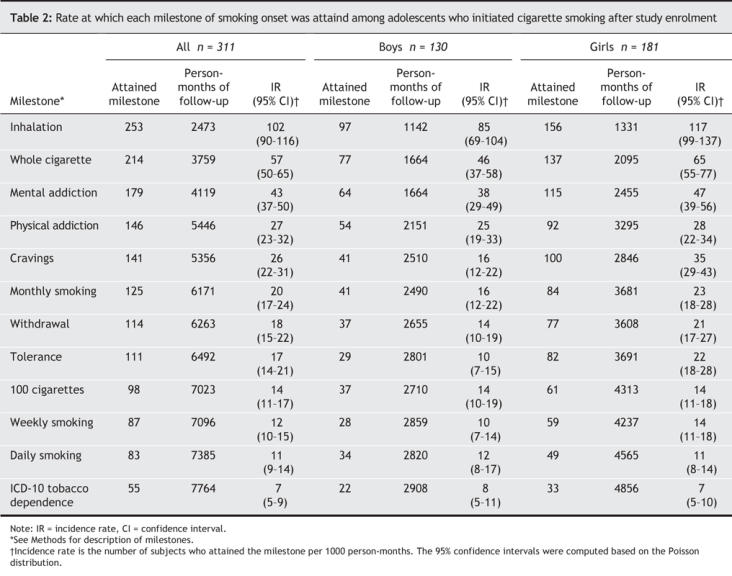

Table 2 summarizes the rate at which the initiators attained the 12 milestones investigated. The incidence rate of inhalation was relatively high (102 per 1000 person-months). It was substantially lower for smoking a whole cigarette and self-reported mental addiction, and substantially lower again for self-reported physical addiction, cravings, monthly smoking, withdrawal symptoms, tolerance, lifetime consumption of 100 cigarettes, weekly smoking and daily smoking. The incidence rate of conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence was 7 per 1000 person-months. Incidence rates were notably higher among girls than among boys for most early milestones in the onset process. However, except for cravings and tolerance, the confidence intervals for all other milestones overlapped. Incidence rates among girls and boys were similar for milestones that occurred late in the onset process, including lifetime consumption of 100 cigarettes, daily smoking and conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence.

Table 2

Temporal sequence and time interval between milestones

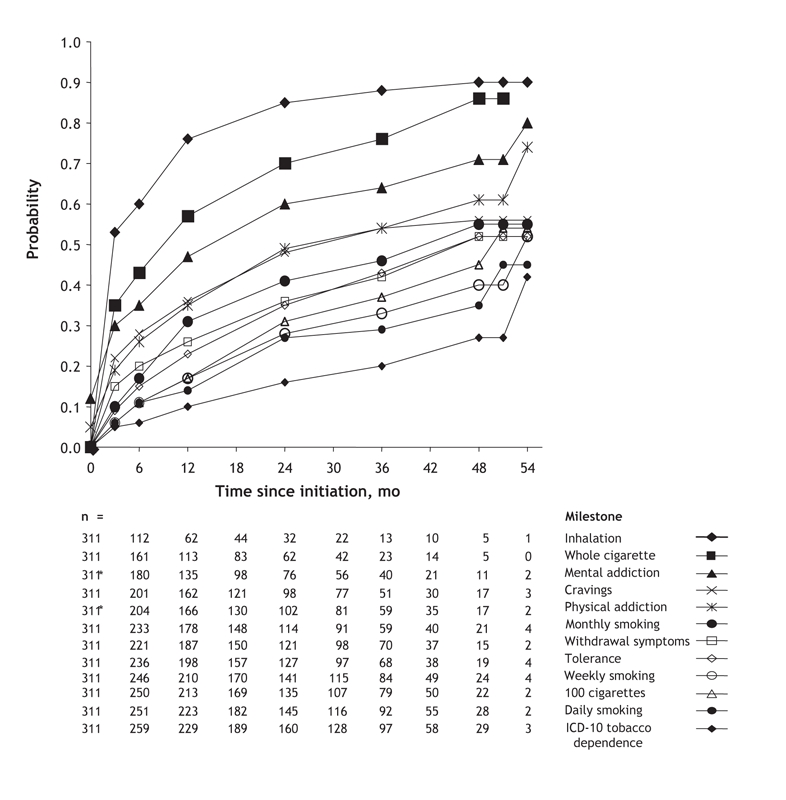

Fig. 2 depicts the cumulative probability of attaining each of the 12 milestones according to time from first puff. Except for the curve for inhalation, which leveled off at about 24 months after first puff, the cumulative probability of attaining most other milestones continued to increase over time. The cumulative probability of inhalation, smoking a whole cigarette and self-reported mental addiction increased sharply during the first 3 months after first puff; the rate of increase was slower thereafter. There was little overlap between the cumulative probability curves except for tight alignment and overlap between the curves for self-reported physical addiction and cravings, and between the curves for tolerance and withdrawal symptoms. The sharp increase in the probability of attaining several milestones at 54 months is difficult to interpret because of the small number of participants available for observation at 54 months. Overall, the figure suggests that, for most subjects, inhalation occurred after initiation, followed sequentially by smoking a whole cigarette, self-reported mental addiction, cravings, self-reported physical addiction, monthly smoking, withdrawal symptoms, tolerance, lifetime consumption of 100 cigarettes, weekly smoking and daily smoking. Conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence was a relatively late and infrequent occurrence.

Fig. 2: Cumulative probability of attaining milestones of onset of cigarette smoking from time since initiation among 311 participants who were nonsmokers at baseline and who initiated cigarette smoking during follow-up. See Methods for definitions of the milestones. *Thirty-six subjects reported mental addiction and 15 reported physical addiction before initiation. These subjects were considered to be incident cases at baseline; they contributed zero person-months to the denominator in the computation of time at risk for selected milestone.

Fig. 3 depicts the natural course of onset of cigarette smoking according to the milestones studied. More specifically, it gives the estimated number of months after first puff when the cumulative probability of attaining each milestone was 25%. Inhalation and smoking a whole cigarette occurred rapidly within a few months; it took almost 9 months to attain the milestone of monthly smoking and about 20 months each to attain that of weekly smoking and a lifetime total of 100 cigarettes, and an additional 4 months to attain the daily smoking milestone. Among the milestones related to nicotine dependence, mental addiction, cravings and physical addiction appeared rapidly (2–5 months after initiation). Withdrawal symptoms, tolerance and conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence took longer to develop (11–41 months after initiation).

Fig. 3: Number of months after initiation of cigarette smoking (first puff) at which the probability of attaining each milestone is 25%. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. (See Methods for definitions of the milestones.)

The temporal sequence of the 12 milestones observed in the main analysis was similar across the subgroup analyses of participants who had inhaled into their lungs (n = 253) and those who had smoked a whole cigarette (n = 214) (see online Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/175/3/255/DC1). In particular, symptoms of nicotine dependence, including cravings and self-reported mental and physical addiction, consistently preceded indicators of heavier smoking, including lifetime consumption of 100 cigarettes, weekly smoking and daily smoking. The sequence was slightly different in the analysis that included only participants who had experienced cravings (n = 141) (see online Appendix 5, available at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/175/3/255/DC1). Mental and physical addiction occurred first in this subgroup, followed by withdrawal symptoms and tolerance, and then by monthly smoking, consumption of 100 cigarettes, weekly smoking, daily smoking and finally conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence.

Overall, the probability of attaining each milestone was higher in each subgroup than in the total sample of initiators, which suggests that, as a person progresses through the milestones, the probability of attaining subsequent milestones increases. This was most prominent among subjects who reported cravings. Relative to all subjects and to those who reported inhalation or smoking a whole cigarette, initiators who reported cravings were at substantially increased risk of progressing to heavier smoking and to conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence during follow-up. For example, by 48 months, the cumulative probability of attaining daily smoking and of conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence was 68% and 49%, respectively, among those who reported cravings. These probabilities were 35% and 27%, respectively among all initiators, 54% and 33% among those who had inhaled into their lungs, and 64% and 37% among those who had smoked a whole cigarette, respectively.

Interpretation

This investigation documents the natural course of onset of cigarette use according to 12 milestones. After first puff, the participants who initiated cigarette smoking during follow-up (initiators) progressed rapidly to inhalation, and symptoms of nicotine dependence developed soon thereafter, well before weekly or daily smoking. Mental addiction was concomitant with smoking a whole cigarette and sometimes occurred even before initiation, possibly reflecting high susceptibility to initiating tobacco use. Cravings occurred early, and once present, there was a relatively high probability of attaining daily smoking and conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence. Withdrawal symptoms occurred shortly after monthly smoking, and tolerance was the last symptom reported. Incidence rates for milestones that appeared early after onset were higher among girls than among boys, but those for later milestones were similar across the sexes.

Challenging staged models of onset that do not incorporate early symptoms of nicotine dependence,6–8 several recent reports suggest that symptoms of nicotine dependence precede daily cigarette use and that they are prevalent among young smokers.11–14 In a 30-month follow-up in the DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth) study,12 symptoms of nicotine dependence were reported by 40% of all participants who had ever used tobacco, and symptoms developed before daily smoking in 70% of these subjects. The median latency to development of dependence symptoms was 54 days from monthly smoking (21 for girls, 183 for boys). “Strong cravings” and “real need for a cigarette” were the 2 earliest, and most frequently reported, symptoms, with median latencies of 141 and 179 days, respectively. “Strong cravings” were reported by 28% of subjects and “real need” by 31%. The need or urge to smoke on trying to stop (a withdrawal symptom), and feeling addicted, which were each reported by about 25% of all youth who had smoked, appeared 202 and 215 days after monthly smoking. In the McGill University Study on the Natural History of Nicotine Dependence in Teens, the proportion of subjects who reported conversion to ICD-10 tobacco dependence at baseline increased from 0% and 3% among those who tried smoking and sporadic smokers, to 5%, 19% and 66% among monthly, weekly and daily smokers, respectively. Girls reported more symptoms of nicotine dependence than did boys in all subgroups of smokers.13 Overall, 57%, 41%, 44% and 33% of monthly smokers reported cravings, strong urge to smoke on stopping, mental addiction and physical addiction, respectively; similarly, 93%, 83%, 82% and 89% of daily smokers reported these symptoms.13

Several limitations may affect the interpretation of our results. We studied adolescents who initiated cigarette use during secondary school, but the natural course of onset may differ for those who initiate smoking earlier or later in life. The sample was too small for sex-specific analyses. Data were based on self-reports; however, recall of cigarette use over 3 months is very good,15 and our measures of symptoms of nicotine dependence are reliable, internally consistent and demonstrate convergent construct validity.17

In summary, our data suggest that a person's first puff may represent the beginning of a process that leads rapidly to symptoms of nicotine dependence and escalating cigarette use in some young smokers. Novice smokers may not recognize the symptoms they experience as related to nicotine dependence, and consequently they may view tobacco control messages as irrelevant. Young people, their parents and health professionals must be made aware that symptoms of nicotine dependence can manifest long before regular smoking and that, once cravings are experienced, the likelihood of progression to daily use and tobacco dependence is greatly increased. This information should be incorporated into interventions to encourage and support novice smokers to stop smoking, and to provide help for those experiencing difficulty quitting because of symptoms of nicotine dependence.

@ See related article page 262

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: André Gervais coordinated the analysis and writing team, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the article and completed the final version of the manuscript. Jennifer O'Loughlin designed the study, obtained the funding, developed the survey instruments, supervised data collection, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Christina Bancej reviewed the literature and contributed to data interpretation and preparation of the manuscript. Garbis Meshefedjian performed data analysis and contributed to data interpretation. Michèle Tremblay contributed to planning the data analysis and contributed to the data interpretation. All of the authors reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Jennifer O'Loughlin, Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health, McGill University, 1020 Pine Ave. W, Montréal QC H3A 1A2; fax 514 398-4501; jennifer.oloughlin@mcgill.ca

REFERENCES

- 1. Thomas R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking [review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(4):CD001293. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Sowden A, Arblaster L, Stead L. Community interventions for preventing smoking in young people [review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(1):CD001291. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Sussman S. Effects of sixty-six adolescent tobacco use cessation trials and seventeen prospective studies of self-initiated quitting. Tobacco Induced Diseases 2002;1:35-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.McDonald P, Colwell B, Backinger CL, et al. Better practices for youth tobacco cessation: evidence of review panel. Am J Health Behav 2003;27(Suppl 2):S144-58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Renaud L, O'Loughlin J, Dery V. The St-Louis du Parc heart health project: a critical analysis of the reverse effects on smoking. Tob Control 2003;12:302-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Mayhew KP, Flay BR, Mott JA. Stages in the development of adolescent smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend 2000;59:S61-81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Flay BR. Youth tobacco use: risk patterns, and control. In: Slade J, Orleans CT, editors. Nicotine addiction: principles and management. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. p. 365-84.

- 8.Preventing tobacco use among young people: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1994.

- 9.Lerman C, Berrettini W. Elucidating the role of genetic factors in smoking behavior and nicotine dependence. Am J Med Genet B 2003;118(B):48-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Breslau N, Fenn N, Peterson E. Early smoking initiation and nicotine dependence in a cohort of young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 1993;33:129-37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.DiFranza JR, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, et al. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tob Control 2000;9:313-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, et al. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: 30 month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tob Control 2002;11:228-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.O'Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale R, et al. Nicotine dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:219-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Wellman RJ, DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, et al. Short term patterns of early smoking acquisition. Tob Control 2004;13:251-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Eppel A. O'loughlin J, Paradis G, Platt R. Reliability of self-reports of cigarette use in novice smokers. Addict Behav. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Choi WS, Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. Which adolescent experimenters progress to established smoking in the United States. Am J Prev Med 1997;13:385-91. [PubMed]

- 17.Pierce JP, Gilpin E. How long will today's new adolescent smoker be addicted to cigarettes? Am J Public Health 1996;86:253-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington (DC): The Association; 1994.

- 19.World Health Organization (WHO). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision. Geneva: WHO,1992.

- 20.O'Loughlin J, Tarasuk J, DiFranza JR, et al. Reliability of selected measures of nicotine dependence among adolescents. Ann Epidemiol 2002;12:353-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.O'Loughlin J, Kishchuk N, DiFranza JR, et al. The hardest thing is the habit: a qualitative investigation of adolescent smokers' experience of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res 2002;4:201-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.