Abstract

Telomeric DNA usually consists of a repetitive sequence: C1–3A/TG1–3 in yeast, and C3TA2/T2AG3 in vertebrates. In yeast, the sequence-specific DNA- binding protein Rap1p is thought to be essential for telomere function. In a tlc1h mutant, the templating region of the telomerase RNA gene is altered so that telomerase adds the vertebrate telomere sequence instead of the yeast sequence to the chromosome end. A tlc1h strain has short but stable telomeres and no growth defect. We show here that Rap1p and the Rap1p-associated Rif2p did not bind to a telomere that contains purely vertebrate repeats, while the TG1–3 single-stranded DNA binding protein Cdc13p and the normally non-telomeric protein Tbf1p did bind this telomere. A chromosome with one entirely vertebrate-sequence telomere had a wild-type loss rate, and the telomere was maintained at a short but stable length. However, this telomere was unable to silence a telomere-adjacent URA3 gene, and the strain carrying this telomere had a severe defect in meiosis. We conclude that Rap1p localization to a C3TA2 telomere is not required for its essential mitotic functions.

Keywords: RAP1/RIF2/telomerase/telomere/yeast

Introduction

Telomeres, the DNA–protein complexes found at the ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes, usually consist of a short repeated sequence that is G-rich on the strand running 5′ to 3′ towards the telomere. For example, telomeres in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae contain about 350 bp of C1–3A/TG1–3 DNA, while the telomere sequence in all vertebrates, including humans, is C3TA2/T2AG3. In diverse organisms, including yeast and humans, the G-rich strand of the telomere extends to form a 3′ single-strand overhang (reviewed in Shore, 2001).

Telomeres have several important functions. They promote the complete replication of chromosome ends through the addition of repeated sequences by telomerase, a specialized reverse transcriptase. Telomeres have an essential role in capping chromosome ends, preventing the degradation and end-to-end fusions seen at double-stranded DNA breaks. In S.cerevisiae, loss of even a single telomere results in a cell-cycle arrest mediated by the DNA damage checkpoint (Sandell and Zakian, 1993). Cells that recover from this arrest without replacing the missing telomere lose the broken chromosome at a very high rate (Sandell and Zakian, 1993). In many species, from yeasts to mammals, a gene placed next to a telomere can be reversibly silenced, a phenomenon known as telomere position effect, or TPE (reviewed in Tham and Zakian, 2002). Telomeres also play an important role in chromosome pairing during meiosis. In many species, telomeres cluster early in meiosis, a process known as bouquet formation, which may help align homologous chromosomes (reviewed in Scherthan, 2001). In fission yeast, the telomere-associated proteins Taz1 and Rap1 are required for efficient meiosis (Cooper et al., 1997; Chikashige and Hiraoka, 2001; Kanoh and Ishikawa, 2001). In S.cerevisiae, the meiosis-specific telomere-associated protein Ndj1p, promotes chromosome pairing and is required for bouquet formation (Chua and Roeder, 1997; Conrad et al., 1997; Trelles-Sticken et al., 1999).

Several proteins are known to associate with Saccharomyces telomeres. Rap1p, an essential protein that binds to duplex S.cerevisiae telomeric DNA (Berman et al., 1986; Longtine et al., 1989), is the major in vivo telomere binding protein present in 10–20 copies per telomere (Conrad et al., 1990; Wright et al., 1992; Gilson et al., 1993). Rap1p recruits two groups of proteins, the Sir proteins that mediate TPE (Aparicio et al., 1991; Moretti et al., 1994) and the Rif proteins that inhibit both telomerase- and recombination-mediated telomere lengthening (Bourns et al., 1998; Teng et al., 2000). Cdc13p, which binds single-stranded TG1–3 DNA in vitro (Lin and Zakian, 1996; Nugent et al., 1996) and chromosome ends in vivo (Bourns et al., 1998; Tsukamoto et al., 2001), is essential because it helps protect chromosome ends from degradation (Garvik et al., 1995). Cdc13p also plays a positive role in regulation of telomerase (Nugent et al., 1996; Qi and Zakian, 2000). Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase includes the catalytic subunit, Est2p, as well as an RNA subunit, TLC1, which has a short template region consisting of the C-strand telomere sequence (reviewed in Nugent and Lundblad, 1998).

Rap1p is also required for transcriptional repression at the silent mating-type loci (Shore et al., 1987) and at telomeres (Liu et al., 1994; Moretti et al., 1994). However, since neither mating-type silencing nor TPE is essential, silencing is therefore not an essential function of Rap1p. Rap1p is also a transcriptional activator at many loci in Saccharomyces, binding in the upstream regions of ∼5% of yeast genes, which together account for ∼37% of all yeast mRNA transcripts (Huet et al., 1985). Since many Rap1p-regulated genes are essential, the role of Rap1p as a transcriptional activator is almost certainly essential.

Rap1p homologs have been identified in many species, including other yeasts (Larson et al., 1994; Chikashige and Hiraoka, 2001; Kanoh and Ishikawa, 2001) and humans (Li et al., 2000). Unlike the budding yeast Rap1p, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe and human Rap1p homologs (spRap1 and hRap1) do not bind DNA directly, but are recruited to the telomere through interactions with telomeric DNA-binding proteins (Li et al., 2000; Chikashige and Hiraoka, 2001; Kanoh and Ishikawa, 2001). In addition, spRap1 and hRap1 have not been shown to have any non-telomeric functions, such as transcriptional activation (Li et al., 2000; Chikashige and Hiraoka, 2001; Kanoh and Ishikawa, 2001). Although S.pombe rap1+ is not essential, a rap1– mutant has long telomeres, lacks TPE and has several meiotic defects, including loss of telomere clustering, reduced sporulation efficiency and low spore viability (Chikashige and Hiraoka, 2001; Kanoh and Ishikawa, 2001). These phenotypes are indistinguishable from those of a strain lacking Taz1, the telomere-binding protein that recruits spRap1 to the telomere (Cooper et al., 1997, 1998; Nimmo et al., 1998).

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains with rap1ts alleles that reduce the ability of Rap1p to bind DNA exhibit telomere shortening at semipermissive temperatures (Conrad et al., 1990; Lustig et al., 1990). Moreover, overexpression of Rap1p leads to increased rates of chromosome loss (Conrad et al., 1990). These data suggest that Rap1p is required not only for transcription but also for the stability function of yeast telomeres. However, the widespread role of Rap1p in transcription makes it difficult to use a standard genetic approach to determine if telomeres lacking Rap1p are functional. As an alternative, we altered the telomere sequence itself. A strain in which the yeast telomere sequence was changed to match the vertebrate sequence, the tlc1-human or tlc1h strain, is viable but has short telomeres (Henning et al., 1998). We constructed a tlc1h strain that had one telomere consisting solely of C3TA2/T2AG3 vertebrate telomeric DNA, a sequence that is not expected to bind Rap1p (Liu and Tye, 1991). As predicted, this telomere bound neither Rap1p nor the Rap1p-associated protein Rif2p, yet its role in chromosome stability was unimpaired. Thus, binding of Rap1p to a C3TA2 telomere is not essential in mitotic cells.

Results

A telomere with only vertebrate repeats can be maintained in yeast

TLC1 encodes the RNA subunit of yeast telomerase. The tlc1h gene is an allele of TLC1 in which the templating portion of the gene is modified to encode the vertebrate telomere repeat (Henning et al., 1998). Because only the distal third of yeast telomeres is subject to degradation and telomerase-mediated resynthesis (Wang et al., 1989), even after prolonged growth, telomeres in a tlc1h strain consist of a mixture of vertebrate C3TA2/T2AG3 and yeast C1–3A/TG1–3 repeats. These mixed-sequence telomeres are ∼150 bp shorter than wild type (Henning et al., 1998).

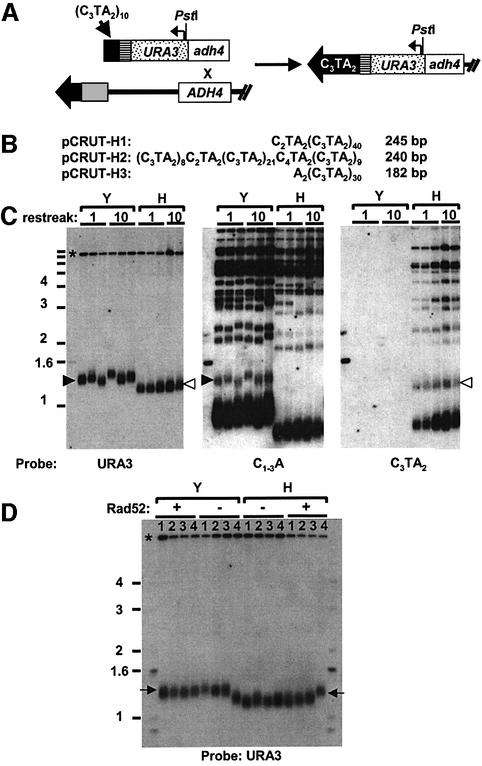

Rap1p does not bind the vertebrate C3TA2 telomere sequence in vitro (Liu and Tye, 1991). To determine if vertebrate telomeric DNA can supply all telomere functions in yeast, we constructed a strain called 499UT-H (UT for URA3 at telomere, H for human telomeric DNA) in which the left telomere of chromosome VII bears only C3TA2 repeats, rather than a mixture of vertebrate and yeast repeats. The VII-L telomere in a tlc1h strain was replaced with the URA3 gene and 60 bp of vertebrate telomere sequence that was lengthened in vivo by the addition of C3TA2 repeats (Figure 1A). The wild-type control strain for 499UT-H was 499UT-Y (Y for yeast telomeric DNA), an otherwise isogenic strain that contained a wild-type TLC1 gene, fully wild-type telomeres and URA3 adjacent to the VII-L telomere.

Fig. 1. A telomere consisting solely of vertebrate telomeric DNA can be stably maintained in yeast. (A) To generate a completely vertebrate-sequence telomere at chromosome VII-L, EcoRI–SalI-digested pUT-H was integrated at the ADH4 locus on chromosome VII-L in a tlc1h strain, in a manner that deletes the terminal ∼20 kb from the chromosome (Gottschling et al., 1990). The 60 bp C3TA2 sequence (black box) acts as a seed for telomere formation. The tlc1h telomerase can add only vertebrate repeats to this end, resulting in a VII-L telomere that contains no yeast telomeric repeats. A unique sequence (striped block) between the telomere seed and the URA3 gene was used as a PCR primer site for telomere sequencing and chromatin immunoprecipitations. The arrow above the spotted box indicates the URA3 promoter. The indicated PstI site is located upstream of the URA3 start codon. (B) Sequencing results for modified VII-L telomere. VII-L telomeres from the 499UT-H strain were cloned and sequenced. Clones were made ∼125 cell divisions after transformation in three independent integrants of the UT-H construct. Representative sequences for three clones, one from each integrant, are shown; the centromere-proximal end of the sequence is to the right. Seven modified telomeres were sequenced; none contained yeast telomeric DNA. While none of the sequenced telomeres contained the heterogeneous C1–3A repeats characteristic of yeast telomeres, the VII-L telomere in the 499UT-H2 transformant contained one copy each of two variants of the vertebrate repeat: C4TA2 and C2TA2. The 499UT-H1 strain, with 245 bp of pure vertebrate repeats, was used for all subsequent experiments. (C) Telomere length is stable in the 499UT-H strain over many generations. Telomere length in the 499UT-Y and 499UT-H strains was assayed after one and ten serial restreaks on YC plates. Genomic DNA was digested with PstI and XhoI; the Southern blot was probed sequentially with URA3, C1–3A and C3TA2. The upper band in the URA3-probed blot (*) is the endogenous ura3-52 allele. Two to three independent colonies from each strain are shown. Black arrowheads indicate the 499UT-Y VII-L telomere; white arrowheads indicate the 499UT-H C3TA2 VII-L telomere. (D) Effect of rad52Δ on telomere length. Southern blots of PstI-digested genomic DNA from four serial restreaks of rad52 and RAD52 versions of the 499UT-Y and 499UT-H strains were probed with URA3 which detects the VII-L telomere fragment. The upper band in the URA3-probed blot (*) is the endogenous ura3-52 allele. Arrows indicate the VII-L (URA3 probe) telomere band.

To confirm that the VII-L telomere in 499UT-H contained only vertebrate telomeric DNA, telomeres from three independent transformants obtained using the UT-H construct were cloned and sequenced ∼125 cell divisions after each received the modified telomere (Figure 1B). The amount of telomeric DNA present at individual VII-L telomeres from the tlc1h strain ranged from 210 to 240 bp. For comparison, VII-L telomeres cloned from the control 499UT-Y strain contained 320–370 bp of C1–3A DNA. None of the 499UT-H clones contained yeast C1–3A repeats but rather had up to 35 pure C3TA2 repeats. The VII-L telomere consisting solely of vertebrate telomeric DNA will hereafter be called the C3TA2 telomere.

Replication and length regulation of the C3TA2 telomere

As reported previously (Henning et al., 1998), the mixed vertebrate and yeast sequence telomeres in a tlc1h strain were ∼150 bp shorter than telomeres in a TLC1 wild-type strain (Figure 1C, center and right panels). A similar shortening was seen at the C3TA2 telomere (Figure 1C, left panel). The lengths of both the C3TA2 telomere and the mixed-sequence telomeres were stable over at least 500 cell divisions (Figure 1; data not shown).

Yeast telomeres are normally maintained by telomerase. In addition to TLC1, telomerase-mediated telomere lengthening requires at least four genes, including EST2, which encodes the catalytic subunit of telomerase (Lendvay et al., 1996; Lingner et al., 1997). In the absence of telomerase, telomeres can be maintained by RAD52-dependent homologous recombination, leading to an amplification of either sub-telomeric or telomeric repeats (Lundblad and Blackburn, 1993; Teng and Zakian, 1999). To determine which pathway, telomerase or recombination, was maintaining telomeres in the tlc1h strain, heterozygous deletions of EST2 and RAD52 were made in a diploid 499UT-H/500UT-H strain (500UT-H is identical to 499UT-H except for being of opposite mating type). The diploid was sporulated, tetrads dissected and spore products of the desired genotypes identified by replica plating.

Viability and telomere length in the 499UT-H strain were unaffected by deletion of the homologous recombination protein RAD52 (Figure 1D). In contrast, no viable est2 tlc1h spores were recovered (data not shown). The synthetic lethality observed for the est2 tlc1h strain was probably due to the fact that telomeres in the tlc1h/tlc1h strain were shorter than in a wild-type strain. Strains lacking an EST gene in an otherwise wild-type background senesce after 50–100 divisions (Lundblad and Szostak, 1989). Since the tlc1h strain started with telomeres that were ∼150 bp shorter than the wild-type length, telomerase-deficient tlc1h cells should senesce after ∼25–50 generations. Since it takes ∼25 generations for a spore to generate a colony, even those est2 tlc1h spores that were able to form a colony after germination would senesce upon the replica plating that was used to identify est2Δ spores. We conclude that the C3TA2 telomere is maintained by telomerase, not recombination.

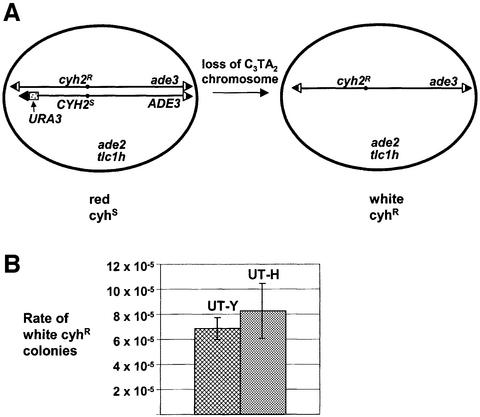

The C3TA2 telomere does not increase the loss rate of chromosome VII

Removal of the yeast VII-L telomere results in a dramatic increase in the rate at which this chromosome is lost (Sandell and Zakian, 1993). Although the growth rate of the tlc1h strain with the C3TA2 telomere was indistinguishable from wild type, loss of a single chromosome must increase by ∼1000-fold before it affects the overall growth rate of a strain. To determine if the C3TA2 telomere affects the mitotic stability of chromosome VII, the loss rate of this chromosome was measured using fluctuation analysis in a tlc1h strain that was disomic for chromosome VII, but had only one copy of each of the other 15 yeast chromosomes (Figure 2A). One copy of chromosome VII carried the C3TA2 telomere while the other copy and all other telomeres in the cell had mixed-sequence telomeres. Whereas the original disome strain produced red colonies that die on cycloheximide plates, cells that lost the chromosome with the C3TA2 telomere generated white, cycloheximide-resistant colonies. As a control, we also determined the loss rate of chromosome VII from an otherwise isogenic TLC1 strain, with completely wild-type telomeres. This analysis revealed that the loss rate of chromosome VII with the C3TA2 telomere was statistically indistinguishable from the loss rate of chromosome VII in a TLC1 strain: ∼7–8 × 10–5 losses per cell division (Figure 2B). The rate of mitotic recombination on the VII-L disome can be determined by counting the number of red, cycloheximide-resistant colonies that have recombined between the CYH2 and ADE3 markers on opposite arms of chromosome VII. This rate was <10–5 in both the tlc1h strain with the C3TA2 telomere and the TLC1 wild-type control. Thus, the stability of the chromosome with the C3TA2 telomere was not due to it having increased mitotic recombination.

Fig. 2. The C3TA2 telomere has a wild-type loss rate. (A) Disome strain for chromosome stability assay. Loss of the test copy of chromosome VII was measured in a chromosome VII disome strain with the tlc1h mutation by selecting for white, cycloheximide-resistant colonies. URA3 with a vertebrate telomere seed was integrated at the VII-L telomere on the test copy of chromosome VII, generating a telomere containing solely vertebrate telomeric DNA. The control strain was a VII-L disome with URA3 at the VII-L telomere on the test copy of the chromosome and wild-type TLC1 (Sandell and Zakian, 1993). C3TA2 repeats are in black portion of triangles; C1–3A DNA is in white. (B) Rates of chromosome loss. The average rates of chromosome loss for UT-Y (TLC1, wt telomeres) and UT-H (tlc1h, C3TA2 VII-L telomere) disome strains. Error bars are standard deviation.

The C3TA2 telomere does not silence expression of an adjacent URA3 gene

TPE in wild-type yeast is the phenomenon where transcription of genes next to telomeres is reversibly repressed (Gottschling et al., 1990). TPE is often monitored by determining the fraction of cells with a telomeric URA3 gene that are able to grow on medium containing 5-fluoro orotic acid (FOA), a compound that kills cells expressing Ura3p. To determine if the C3TA2 telomere exhibited TPE, 10-fold serial dilutions of the 499UT-H strain were spotted on plates containing FOA. The same dilutions were also plated on complete medium lacking FOA (YC plates) to monitor viability. While the TLC1 499UT-Y strain grew well on FOA plates, almost no growth was observed for the tlc1h 499UT-H strain (Figure 3A). This loss of silencing was quantitated by comparing plating efficiency on complete medium versus FOA plates. The frequency of silencing at the C3TA2 telomere was reduced ∼30 000-fold, from 0.54 ± 0.24 (average ± standard deviation) in the TLC1 499UT-Y strain to 1.8 ± 0.59 × 10–5 at the C3TA2 telomere (Figure 3A).

Fig. 3. TPE and nuclear organization of a tlc1h strain. (A) TPE of 499UT-Y and 499UT-H strains. Ten-fold serial dilutions of 499UT-Y (Y) and 499UT-H (H) were plated on YC plates (to control for viability) and FOA plates (to select for cells that did not express the telomeric URA3 gene). TPE was also quantitated by comparing plating efficiency of the 499UT-Y and 499UT-H strains on FOA and non-selective medium. (B) Localization of myc-Tbf1p and Rap1p by immunofluorescence. 499UT-Y (Y) and 499UT-H (H) strains expressing myc-tagged Tbf1p were stained with α-Rap1p polyclonal antibodies and DAPI stain or with α-myc monoclonal antibodies.

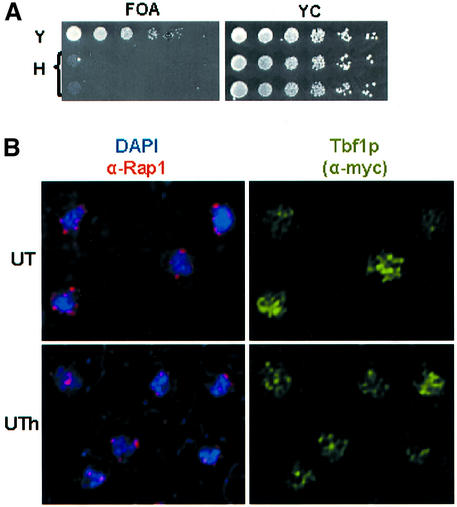

The tlc1h strain has a severe meiotic defect

To determine the behavior of the C3TA2 telomere in meiosis, we sporulated a diploid strain that was homozygous for tlc1h and the C3TA2 telomere (H/H strain) and compared it with an otherwise isogenic TLC1/TLC1 diploid that also had URA3 at the left telomere on both copies of chromosome VII but had fully yeast sequence telomeres (Y/Y strain) (Figure 4A). We also sporulated a tlc1h/tlc1h diploid that had one copy of the C3TA2 telomere (H/YH strain; the rest of the telomeres were mixed-sequence telomeres) and a tlc1h/tlc1h diploid in which neither of the VII-L telomeres was modified by insertion of URA3 (YH/YH strain; all telomeres were a mixture of yeast and vertebrate repeats).

Fig. 4. The tlc1h strain has altered meiosis. (A) Diploid strains used in meiosis experiments. Diploid strains containing URA3 on both copies of chromosome VII-L with either solely yeast telomere sequence and wild-type TLC1 (Y/Y) or homozygous for both the C3TA2 telomere and the tlc1h mutation (H/H), as well as diploids homozygous for the tlc1h mutation and carrying URA3 with the C3TA2 telomere on only one (H/YH) or neither (YH/YH) copy of chromosome VII-L were sporulated (Y indicates solely yeast repeats at VII-L telomere; H indicates solely human telomeric repeats on the VII-L telomere; YH indicates a mixture of yeast and human telomeric DNA at the VII-L telomere; the rest of the telomeres in the tlc1h strains were a mixture of yeast and C3TA2 repeats). Yeast C1–3A telomeric repeats are in gray; vertebrate C3TA2 telomeric repeats are in black. (B) The number of asci was divided by the number of asci plus unsporulated cells to give the percent sporulated cells. The number of spores per ascus was also determined, and used to calculate the percentage of asci containing dyads and tetrads. Graphs display averages ± standard deviation.

Although the frequency of sporulation, as measured by comparing the number of asci with the total number of asci plus unsporulated cells, was only 27% in the H/H strain (compared with 41% for the Y/Y wild-type strain), this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 4B). A much more severe defect was seen when the percentages of asci containing complete tetrads were compared between the two strains; while 82% of asci in the Y/Y wild-type diploid contained four spores, only 11% did so in the H/H strain. Most asci in the H/H strain, 69%, contained only two spores. A similarly low fraction of four-spore asci and high fraction of dyads was seen in the H/YH and YH/YH strains, in which all telomeres contained a mixture of C3TA2 and C1–3A telomeric DNA. The viability of spores from either the rare tetrads (66% spore viability) or the more common dyads (64% viability) was modestly reduced in the H/H strain compared with wild type (90% spore viability). Spore viability was similarly reduced in H/YH and YH/YH dyads (46 and 55% viability, respectively).

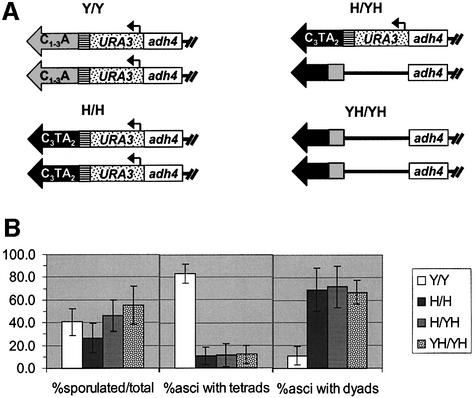

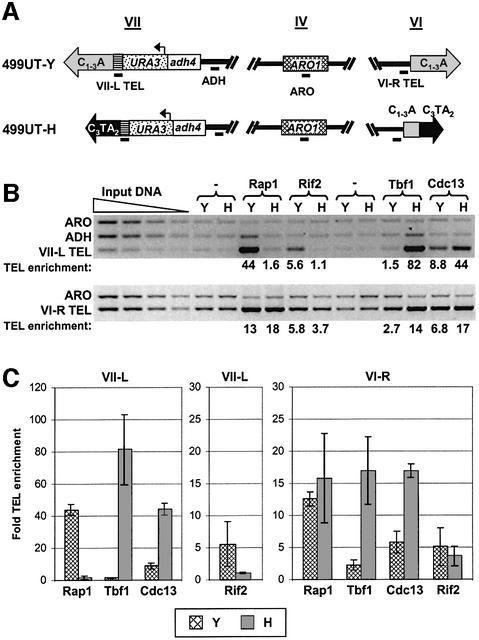

Protein composition of the C3TA2 telomere: Cdc13p and Tbf1p but not Rap1p or Rif2p are bound in vivo

To determine which proteins bound the C3TA2 telomere in vivo, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) (Figure 5). In this assay, proteins are crosslinked to each other and to DNA using formaldehyde. The crosslinked DNA is sheared into small pieces by sonication, and precipitated using antibodies to the protein of interest. The crosslinks are then reversed, the DNA is deproteinized, and the precipitated DNA is PCR amplified. To examine whether telomeric sequences were preferentially associated with the proteins of interest, we used a multiplex PCR strategy that was developed to examine telomere- associated proteins (Tsukamoto et al., 2001; Taggart et al., 2002). Four sequences were PCR amplified from the immunoprecipitated DNA (Figure 5A): ARO, a 372 bp segment of ARO1, a gene on chromosome IV that is far from either telomere and serves as a negative control for telomere binding; ADH, a 301 bp fragment from within ADH4, a sub-telomeric gene that is 5 kb from the left telomere of chromosome VII; VII-L TEL, a 252 bp sequence that is immediately adjacent to the modified VII-L telomere; and VI-R TEL, a 265 bp sequence adjacent to the VI-R telomere.

Fig. 5. Protein composition of the C3TA2 telomere. (A) Sequences assayed in ChIPs. Sequences amplified by PCR are indicated by a black bar below the chromosome. Multiplex PCR was performed on the immunoprecipitated samples as well as input DNA dilutions, amplifying four sequences: the internal control sequence ARO, the sub- telomeric sequence ADH and the telomere-adjacent sequences VII-L TEL and VI-R TEL (representing the completely vertebrate VII-L telomere and the mixed-sequence VI-R telomere, respectively). (B) ChIP results. ChIPs were performed using polyclonal antibodies to Rap1p and Rif2p, and myc-tagged Tbf1p and Cdc13p. An N-terminal 9-myc tag was integrated at the chromosomal copy of Tbf1p; the tagged protein was expressed from the endogenous TBF1 promoter. Since myc-TBF1 cells grew nearly as well as wild-type, the tagged protein fulfilled the essential function of Tbf1p. Cdc13p with a C-terminal 9-myc tag was expressed from the CDC13 promoter on a centromere plasmid in a strain that also expressed wild-type Cdc13p from the endogenous locus; when the 9-Myc-Cdc13p is the only Cdc13p in the cell, it supports wild-type telomere length and growth rate (Taggart et al., 2002). Input DNA represents the total chromatin isolated, before immunoprecipitation; two-fold serial dilutions of the input DNA were amplified by PCR to establish the linear range of the PCR amplifications. Negative control samples were immunoprecipitated from untagged strains with either polyclonal antibodies to the non-telomere protein Ypt1 (this was used to define background levels for the polyclonal Rap1p and Rif2p sera) or α-myc monoclonal antibodies (the control for the myc-Tbf1 and Cdc13-myc strains). (C) Quantitation of ChIP data. The fold enrichment of the VII-L and VI-R TEL bands over background levels are shown; error bars indicate standard deviations. The fold enrichment was normalized to the ARO1 control band. Note that because the fold enrichments of Rap1p, Tbf1p and Cdc13p at the VII-L telomere are considerably higher than the other signals obtained, the leftmost plot is on a different scale than the center and right plots.

Rap1p and Rif2p, a Rap1p-interacting protein involved in telomere length regulation (Wotton and Shore, 1997), were precipitated using polyclonal sera. Tbf1p, an essential yeast protein of unknown function, binds to duplex C3TA2 DNA in vitro (Liu and Tye, 1991). Cdc13p, a known in vivo single-stranded TG1–3 DNA binding protein (Bourns et al., 1998; Taggart et al., 2002), also binds single-stranded T2AG3 DNA in vitro, albeit with ∼10-fold lower affinity (Lin and Zakian, 1996; Nugent et al., 1996). The endogenous TBF1 locus was tagged with nine tandem Myc epitopes, while Myc-tagged Cdc13p was expressed under its own promoter from a centromere plasmid. The Myc-tagged proteins were precipitated with α-myc monoclonal antibodies. The fold TEL enrichment was determined by first normalizing each TEL band to the ARO control band, and then comparing the normalized TEL band for each sample with a negative control immunoprecipitated with a non-telomeric polyclonal antibody (for Rap1p and Rif1p samples) or from an untagged strain using α-myc monoclonal antibody (for the Tbf1p and Cdc13p samples).

When crosslinked chromatin from the TLC1 499UT-Y strain was immunoprecipitated with α-Rap1p polyclonal antibodies, a strong enrichment (44 ± 3.5-fold; average ± standard deviation) of the VII-L telomere-adjacent TEL sequence was observed (Figure 5B and C). In contrast, no significant enrichment of the VII-L TEL band was observed at the C3TA2 telomere (1.6 ± 1.0) in the 499UT-H strain. To confirm the Rap1p result, the Rap1p-interacting factor Rif2p was also immunoprecipitated. In the TLC1 strain, Rif2p co-immunoprecipitated the VII-L TEL DNA (5.6 ± 3.5-fold enrichment), confirming earlier work using a one-hybrid assay which showed that Rif2p interacts with wild-type telomeres in vivo (Bourns et al., 1998). Consistent with the Rap1p results, the C3TA2 VII-L TEL was not precipitated by the α-Rif2p serum (1.1 ± 0.16). The inverse result was obtained when precipitating myc-Tbf1p. The C3TA2 VII-L TEL band was enriched 82 ± 22-fold in the 499UT-H strain, but was at background levels (1.5 ± 0.30) in the 499UT-Y strain that contained only yeast telomeric DNA. In contrast, Cdc13p-myc co-precipitated the VII-L TEL DNA in both the 499UT-Y and 499UT-H strains, although the enrichment was even greater in the 499UT-H strain (44 ± 3.8-fold) than in the wild-type control (8.8 ± 1.9-fold). For each protein, the telomere association was dependent on in vivo crosslinking, demonstrating that these associations occurred in vivo (data not shown). The enrichments for Rap1p in 499UT-Y and Tbf1p in 499UT-H are minimal estimates, as these TEL bands were outside the linear range for quantitation.

In the 499UT-H strain, the VI-R telomere contained a mixture of vertebrate and yeast telomeric DNA, and thus was expected to bind Rap1p, Rif2p, Cdc13p and Tbf1p. Consistent with this expectation, Cdc13p and Tbf1p bound well to both the VI-R and VII-L telomeres in the 499UT-H strain (Figure 5B and C). In contrast to the results with the C3TA2 telomere, Rap1p and Rif2p both localized to the VI-R telomere in the 499UT-H strain.

Nuclear localization of Rap1p and Tbf1p is unchanged in a tlc1h strain

Immunolocalization reveals that several proteins needed for telomeric silencing, including Rap1p, are concentrated in 6–8 foci that localize to the nuclear periphery (Gotta et al., 1996). In situ hybridization shows that many telomeres localize to these Rap1p foci (Gotta et al., 1996). In contrast, Tbf1p has a punctate staining throughout the yeast nucleus (Koering et al., 2000). Given the altered telomere binding of Rap1p and Tbf1p in the tlc1h strain, we determined if the nuclear localization of either protein was also affected. To ensure that telomeres had high levels of vertebrate telomere repeats, the tlc1h strain was examined after >150 cell divisions of growth. Localiz ation of Rap1p and Tbf1p in nuclei was analyzed by immunofluorescence using either an affinity purified anti-Rap1p polyclonal serum or anti-myc serum (Figure 3B). As reported previously (Koering et al., 2000), Tbf1p exhibited punctate staining in the TLC1 strain, a pattern that was unaltered in the tlc1h strain (Figure 3B, right). Rap1p was concentrated in foci in both the TLC1 and tlc1h strains (Figure 3B, left panels). This analysis demonstrates that the nuclear organization of Rap1p foci, and by inference of telomeres, is not grossly altered in the tlc1h strain.

Discussion

The essential protein Rap1p was thought to be critical both to protect chromosome ends from degradation (Conrad et al., 1990; Lustig et al., 1990) and, in concert with the associated Rif proteins, for telomere length homeostasis (Marcand et al., 1997). We show here that a telomere consisting solely of C3TA2/T2AG3 repeats (Figure 1B) did not bind Rap1p or Rif2p (Figure 5). Nonetheless, the length of this telomere was stable for >500 cell divisions (Figure 1C), suggesting that yeast also has a Rap1p-independent mechanism for monitoring telomere length. The absence of Rif proteins, which limit telomerase action (Teng et al., 2000), is normally associated with telomere lengthening (Hardy et al., 1992; Wotton and Shore, 1997). The fact that the C3TA2 telomere that lacked Rif2p (and presumably Rif1p) stabilized at a length shorter than that of a wild-type telomere suggests that Rap1p does help protect telomeres from degradation.

Remarkably, a chromosome with the C3TA2 telomere had a wild-type loss rate (Figure 2). Since loss of only one telomere is sufficient to dramatically destabilize chromosome VII (Sandell and Zakian, 1993), the C3TA2 telomere must be able to supply the critical telomere functions that ensure the stable maintenance of chromosomes. A wild-type telomere is estimated to bind 10–20 Rap1p molecules (Conrad et al., 1990; Wright et al., 1992; Gilson et al., 1993). The VII-L telomere with wild-type telomeric DNA was enriched ∼30-fold more than the C3TA2 telomere in the anti-Rap1p immunoprecipitate (Figure 5), suggesting that Rap1p did not bind the C3TA2 telomere in vivo. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the C3TA2 telomere sometimes bound one or a very few Rap1p molecules, our data suggest that the stability functions of yeast telomeres may not require Rap1p. In contrast, both Cdc13p and Tbf1p bound the C3TA2 telomere efficiently (Figure 5). Although no sequence or functional similarities have been shown between Rap1p and Tbf1p outside of the Myb-like DNA binding domain (Bilaud et al., 1996), Tbf1p may provide the stability functions of Rap1p at the modified telomere.

Although the C3TA2 telomere did not impair chromosome stability, meiosis was compromised in the tlc1h strain, as demonstrated by a paucity of four spore tetrads (Figure 4B). Because Rap1 is required for efficient meiosis in S.pombe (Chikashige and Hiraoka, 2001; Kanoh and Ishikawa, 2001), it is tempting to speculate that the meiotic defect of the tlc1h strain is due to the lack of Rap1p at the C3TA2 telomere. However, by the criterion of ChIP, Rap1p bound as well to the mixed-sequence VI-R telomere as it did to telomeres consisting solely of yeast telomeric DNA (Figure 5). Since the YH/YH diploid, with its mixture of yeast and vertebrate telomeric DNA at all telomeres, was as defective in meiosis as the H/H strain that was homozygous for the C3TA2 telomere (Figure 4B), the meiotic defect of the tlc1h strain can not be attributed solely to the absence of Rap1p at the VII-L telomere. Ndj1p is a meiosis-specific telomere protein that affects homolog pairing and telomere clustering (Chua and Roeder, 1997; Conrad et al., 1997; Trelles-Sticken et al., 2000). Although we did not examine Ndj1p binding in the tlc1h strain, an ndj1Δ strain does not have a preponderance of two-spore asci. Thus, even if Ndj1p were improperly localized in the tlc1h strain, it would not be sufficient to explain the meiotic defects in this strain. Tbf1p bound well to both the C3TA2 telomere and the mixed-sequence VI-R telomere (Figure 5). Since Tbf1p is not normally telomere bound (Figure 5), perhaps its presence perturbs one or more aspects of meiotic telomere behavior, even in strains that have some C1–3A (as well as C3TA2) telomeric repeats.

TPE was abolished at the C3TA2 telomere (Figure 3A). Tbf1p, which bound efficiently to the C3TA2 telomere, is proposed to halt the spread of telomeric silencing within sub-telomeric DNA (Fourel et al., 1999). The absence of Rap1p, which recruits the Sir silencing proteins to the telomere (Liu et al., 1994; Moretti et al., 1994), and the presence of Tbf1p are sufficient to explain the loss of TPE at the C3TA2 telomere (Figure 3A).

Although Cdc13p binds both single stranded TG1–3 and T2AG3 DNAs in vitro, its affinity for the vertebrate telomeric sequence is considerably lower (Lin and Zakian, 1996; Nugent et al., 1996). Nonetheless, in the tlc1h strain, Cdc13p bound well to both the C3TA2 and the mixed-sequence VI-R telomere. In fact, the telomeric fragments from both the VII-L C3TA2 telomere and the mixed-sequence VI-R telomere were enriched by ∼5-fold more in the anti-Cdc13p precipitates from the tlc1h strain than from a TLC1 strain that had solely yeast telomeric DNA. The higher telomere enrichment in the anti-Cdc13p immunoprecipitate might reflect an altered telomere structure in the tlc1h strain, such as longer or constitutive single-stranded TG1–3 tails that results in more telomere-bound Cdc13p, or an altered telomeric chromatin, that results in more efficient precipitation of telomere-bound Cdc13p. Although Cdc13p clearly associated with the C3TA2 telomere, the tlc1h strain was particularly sensitive to changes in Cdc13p. For example, although replacing the chromosomal CDC13 gene with the Myc-tagged CDC13 was readily accomplished in a TLC1 strain (Tsukamoto et al., 2001), we were unable to construct a tlc1h strain expressing only Myc-tagged Cdc13p. To circumvent this problem, we expressed Myc-tagged Cdc13p from a centromeric plasmid in a CDC13 background.

In summary, although Rap1p has been thought to play a central role in organizing the telomeric chromatin structure in S.cerevisiae, surprisingly, telomere binding of Rap1p is not required for the stability functions of a C3TA2 telomere during mitotic growth. A strain carrying an entirely vertebrate-sequence telomere that did not bind Rap1p had no growth defect and no increase in chromosome loss. Although the C3TA2 telomere was somewhat shorter than a wild-type telomere, its length was constant over many generations, indicating that Rap1p is also not essential for regulating telomere length. Consistent with our data, Brevet et al. (2003) found that a fully C3TA2 telomere could be maintained indefinitely, did not bind Rap1p by ChIP, and did not elongate in rap1t, rif1 or rif2 strains, as predicted if Rap1p did not bind this telomere (V.Brevet and E.Gilson, personal communication). These data suggest that transcriptional activation may be the only essential function of Rap1p, while Cdc13p and its associated proteins Stn1p and Ten1p (Grandin et al., 1997, 2001; Pennock et al., 2001) may suffice for the essential function of telomeres in end protection.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and strains

pUT-H was constructed by excising 81 bp of yeast telomere sequence from pADH4UCA III mod(–) (Tsukamoto et al., 2001) and replacing it with 60 bp of vertebrate telomere sequence, obtained by annealing the UT-H-5′ and UT-H-3′ oligos (Table I), which consist of the sequence (T2AG3)10 or (C3TA2)10 flanked by BamHI and EcoRI sites. The pRS304-myc-TBF1 plasmid (constructed using the method of Michaelis et al., 1997) was used to integrate a 9-myc epitope tag at the N-terminus of the chromosomal copy of TBF1. An ∼200 bp region upstream of the TBF1 gene that included the start codon was PCR amplified using primers TBF1-N1 and TBF1-N2 (Table I), which introduced an EcoRI site at the 5′ end and a SpeI site following the start codon. Another 200 bp from the beginning of the TBF1 gene was PCR amplified with primers TBF1-N3 and TBF1-N4 (Table I), which introduced a SpeI site following the start codon and a SacI site at the end of the fragment. These two PCR products, which share 42 bp of sequence around the TBF1 start codon, were used as the template for a PCR with primers TBF1-N1 and TBF1-N4. The resulting 400 bp fragment was cloned into the EcoRI–SacI site of pRS304 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989), and a 360 bp 9-myc epitope tag (Michaelis et al., 1997) was inserted into the SpeI site downstream of the TBF1 start codon. A 9-myc epitope tag was integrated at the N-terminus of the chromosomal copy of TBF1 by transforming NdeI-digested pRS304-myc-TBF1 into 499UT-Y and 499UT-H. Myc-tagged Cdc13p was expressed from the centromeric plasmid pRS314-CDC13-myc9 (Taggart et al., 2002). All strains were constructed in the YPH499 or YPH500 strain background (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989). The control strains were MATa and MATα versions of TEL::URA3/VII-L strains (Tsukamoto et al., 2001), referred to here as 499UT-Y and 500UT-Y, respectively. These strains contain URA3 adjacent to the VII-L telomere, and a 73 bp unique sequence between URA3 and the telomere; this unique sequence is in the opposite orientation to that of the strains in Tsukamoto et al. (2001).

Table I. Primer sequences.

| UT-H-5′ | CGCGGATCCGGACG(T2AG3)10GAATTCCGG |

| UT-H-3′ | CCGGAATTC(C3TA2)10CGTCCGGATCCGCG |

| UT(+) | TCCGGATCCAGAAAAGCAGGCTGGGATATC |

| UT-H(–) | GGATATCCCAGCCTGCTTTTCTGGATGCGG |

| TBF1-N1 | CCACGGAATTCGTAGAAGCCCGGCGAGACC |

| TBF1-N2 | GGGCACTTGCGAATCACTAGTCATGACAAATGGGGAAAGAAG |

| TBF1-N3 | CACTTCTTTCCCCATTTGTCATGACTAGTGATTCGCAAGTGC |

| TBF1-N4 | CCACGGAGCTCTTAGCTTAGGAAAGCCGTCTGGTCC |

| est2HISa | ATGAAAATCTTATTCGAGTTCATTCAAGACAAGCTTGACATCGTTCAGAATGACACG |

| est2HISb | AGCATCATAAGCTGTCAGTATTTCATGTATTATTAGTACTCTCTTGGCCTCCTCTAG |

A strain expressing a TLC1 allele in which the template region encodes the vertebrate telomere sequence instead of the yeast sequence was constructed by a two-step integration of the tlc1h allele from pTLC1h (Henning et al., 1998) into YPH500. Correct integrants were identified by colony PCR as previously described (Henning et al., 1998) and by Southern blots of XhoI-digested genomic DNA hybridized with an 800 bp C3TA2 probe from pSP73-Sty11 (from T.de Lange) to monitor incorporation of the vertebrate sequence at the telomeres. The 500UT-H strain, carrying an entirely vertebrate telomere, was constructed by integrating the 2.4 kb EcoRI–SalI fragment of pUT-H at the VII-L telomere of the YPH500 tlc1h strain (Figure 1A). The mating type of 500UT-H was switched from MATα to MATa to generate 499UT-H. Diploid strains homozygous for the tlc1h allele and the UT-H telomere were made by mating 499UT-H to 500UT-H. A diploid strain homozygous for the tlc1h mutation and heterozygous for the UT-H telomere was produced by mating 499UT-H to YPH500 tlc1h.

Heterozygous deletions of EST2 were constructed by PCR amplifying HIS3 with primers containing homology to the flanking regions of the EST2 gene (est2HISa and est2HISb; Table I) and transforming the product into the 499UT-Y/500UT-Y and 499UT-H/500UT-H diploid strains. Heterozygous strains carrying a rad52::LEU2 allele were made by introducing the 5 kb BamHI fragment of pSM20 (Schild et al., 1983) into the 499UT-Y/500UT-Y and 499UT-H/500UT-H diploid strains. Haploid spore products carrying est2 or rad52 mutations were identified by replica plating spore clones of dissected tetrads to medium lacking histidine or leucine, respectively.

The control disome strain for chromosome loss analysis was LS20xLS18 (Sandell and Zakian, 1993). The disome strain with vertebrate-sequence telomeres was constructed by integrating the tlc1h allele in LS20 (Sandell and Zakian, 1993), mating LS20 with the kar1 strain LS15 [parent strain of LS18 with unmodified VII-L telomere (Sandell and Zakian, 1993)], and selecting on YC Can-Arg-Lys-Tyr low Ade to isolate a chromosome VII disome strain. The 2.4 kb EcoRI–SalI fragment of pUT-H was integrated at the VII-L telomere of the LYS5 aro2 CYH2 ADE3 copy of chromosome VII (the test chromosome). The tlc1h disomic strain with the C3TA2 telomere was grown for >100 generations before chromosome loss was measured. Chromosome loss assays were performed similarly to Sandell and Zakian (1993). Recombination was monitored by counting the number of red, cycloheximide-resistant colonies that arose.

Diploid strains were sporulated for 5–6 days at room temperature in 0.5% potassium acetate. Sporulated cells were incubated 15 min at 30°C with 0.5 mg/ml zymolyase in 1 M sorbitol and dissected on YC plates.

Analysis of telomeres

The VII-L telomere was PCR-amplified as in Forstemann et al. (2000), using primers dG18-Bam (Forstemann et al., 2000) and UT-Y(+) for wild-type telomeres or UT-H(–) for C3TA2 telomeres (Table I). The resulting products were cloned into the pCRII-TOPO vector using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and sequenced using M13 primers on an Applied Biosystems 3100 automated DNA sequencer (MWG Biotech AG, Ebersberg, Germany). Telomere length was monitored by Southern blots of yeast genomic DNA digested with PstI and XhoI and probed sequentially with the URA3 gene, ∼300 bp C1–3A from pCT300 and 800 bp C3TA2 from pSP73-Sty11 (from T.de Lange). TPE was measured qualitatively by spotting 10-fold serial dilutions of overnight cultures onto YC, YC –Ura and FOA plates. Quantitative silencing assays were performed as in Gottschling et al. (1990).

ChIP was performed essentially as in Taggart et al. (2002) except that protein A and G Dynabeads were used (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). PCR products were quantitated using the Scion Image program (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD). Polyclonal sera were used to precipitate Rap1p (Conrad et al., 1990) and Rif2p (S.-C.Teng, unpublished data), while anti-Myc monoclonal antibodies (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) were used for myc-tagged proteins. The Rif2p antiserum was raised in rabbits against full-length, glutathione S-transferase-tagged Rif2p purified from Escherichia coli and affinity purified (S.-C.Teng, unpublished data). The negative control for samples precipitated with polyclonal antibodies was a sample immunoprecipitated with polyclonal serum to the non-telomere protein Ypt1p (provided by G.Waters).

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence localization (Tham et al., 2001), diploid cells were labeled using a 1:2000 dilution of affinity-purified (W.-H.Tham, unpublished data) α-Rap1 polyclonal antibody (Conrad et al., 1990) or haploid myc-Tbf1p cells were labeled with a 1:200 dilution of α-myc monoclonal antibody (Clontech). The secondary antibodies were 1:100 dilutions of Alexa Fluor 546 and Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank P.P.Liu for the tlc1h allele; S.-C.Teng, M.G.Waters and W.-H.Tham for antibodies; A.Taggart and L.Goudsouzian for help with chromatin immunoprecipitation; and M.Mondoux for help with immunofluorescence. We also thank V.Brevet and E.Gilson for communicating results prior to publication, and T.Fisher, M.Mondoux, M.Sabourin and A.Taggart for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM43265 to V.A.Z.; M.K.A. was supported by a HHMI predoctoral fellowship and through NIH cancer training grant CA09528 to the Department of Molecular Biology at Princeton University.

Note added in proof

Using chromatin immunoprecipitation, we find that Yku80p, a subunit of the heterodimeric Ku complex, binds well to the C3TA2 telomere.

References

- Aparicio O.M., Billington,B.L. and Gottschling,D.E. (1991) Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S.cerevisiae. Cell, 66, 1279–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman J., Tachibana,C.Y. and Tye,B.-K. (1986) Identification of a telomere-binding activity from yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 3713–3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilaud T., Koering,C.E., Binet-Brasselet,E., Ancelin,K., Pollice,A., Gasser,S.M. and Gilson,E. (1996) The telebox, a Myb-related telomeric DNA binding motif found in proteins from yeast, plants and human. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 1294–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourns B.D., Alexander,M.K., Smith,A.M. and Zakian,V.A. (1998) Sir proteins, Rif proteins and Cdc13p bind Saccharomyces telomeres in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 5600–5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brevet V., Berthiau,A.-S., Civitelli,L., Donini,P., Schvamke,V., Géli,V., Ascenzioni,F. and Gilson,E. (2003) The number of vertebrate repeats can be regulated at yeast telomeres by Rap1-independent mechanisms. EMBO J., 22, 1697–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikashige Y. and Hiraoka,Y. (2001) Telomere binding of the Rap1 protein is required for meiosis in fission yeast. Curr. Biol., 11, 1618–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua P.R. and Roeder,G.S. (1997) Tam1, a telomere-associated meiotic protein, functions in chromosome synapsis and crossover interference. Genes Dev., 11, 1786–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad M.N., Wright,J.H., Wolf,A.J. and Zakian,V.A. (1990) RAP1 protein interacts with yeast telomeres in vivo: overproduction alters telomere structure and decreases chromosome stability. Cell, 63, 739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad M.N., Dominguez,A.M. and Dresser,M.E. (1997) Ndj1p, a meiotic telomere protein required for normal chromosome synapsis and segregation in yeast. Science, 276, 1252–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J.P., Nimmo,E.R., Allshire,R.C. and Cech,T.R. (1997) Regulation of telomere length and function by a Myb-domain protein in fission yeast. Nature, 385, 744–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J.P., Watanabe,Y. and Nurse,P. (1998) Fission yeast Taz1 protein is required for meiotic telomere clustering and recombination. Nature, 392, 828–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstemann K., Hoss,M. and Lingner,J. (2000) Telomerase-dependent repeat divergence at the 3′ ends of yeast telomeres. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 2690–2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourel G., Revardel,E., Koering,C.E. and Gilson,E. (1999) Cohabitation of insulators and silencing elements in yeast subtelomeric regions. EMBO J., 18, 2522–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvik B., Carson,M. and Hartwell,L. (1995) Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 6128–6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson E., Roberge,M., Giraldo,R., Rhodes,D. and Gasser,S.M. (1993) Distortion of the DNA double helix by RAP1 at silencers and multiple telomeric binding sites. J. Mol. Biol., 231, 293–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta M., Laroche,T., Formenton,A., Maillet,L., Scherthan,H. and Gasser,S.M. (1996) The clustering of telomeres and colocalization with Rap1, Sir3 and Sir4 proteins in wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol., 134, 1349–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschling D.E., Aparicio,O.M., Billington,B.L. and Zakian,V.A. (1990) Position effect at S.cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of Pol II transcription. Cell, 63, 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin N., Reed,S.I. and Charbonneau,M. (1997) Stn1, a new Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein, is implicated in telomere size regulation in association with Cdc13. Genes Dev., 11, 512–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin N., Damon,C. and Charbonneau,M. (2001) Ten1 functions in telomere end protection and length regulation in association with Stn1 and Cdc13. EMBO J., 20, 1173–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy C.F., Sussel,L. and Shore,D. (1992) A RAP1-interacting protein involved in transcriptional silencing and telomere length regulation. Genes Dev., 6, 801–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning K.A., Moskowitz,N., Ashlock,M.A. and Liu,P.P. (1998) Humanizing the yeast telomerase template. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 5667–5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huet J., Cottrelle,P., Cool,M., Vignais,M.L., Thiele,D., Marck,C., Buhler,J.M., Sentenac,A. and Fromageot,P. (1985) A general upstream binding factor for genes of the yeast translational apparatus. EMBO J., 4, 3539–3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanoh J. and Ishikawa,F. (2001) spRap1 and spRif1, recruited to telomeres by Taz1, are essential for telomere function in fission yeast. Curr. Biol., 11, 1624–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koering C.E., Fourel,G., Binet-Brasselet,E., Laroche,T., Klein,F. and Gilson,E. (2000) Identification of high affinity Tbf1p-binding sites within the budding yeast genome. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 2519–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson G.P., Castanotto,D., Rossi,J.J. and Malafa,M.P. (1994) Isolation and functional analysis of a Kluyveromyces lactis RAP1 homologue. Gene, 150, 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendvay T.S., Morris,D.K., Sah,J., Balasubramanian,B. and Lundblad,V. (1996) Senescence mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a defect in telomere replication identify three additional EST genes. Genetics, 144, 1399–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Oestreich,S. and de Lange,T. (2000) Identification of human Rap1: implications for telomere evolution. Cell, 101, 471–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.J. and Zakian,V.A. (1996) The Saccharomyces CDC13 protein is a single-strand TG1–3 telomeric DNA binding protein in vitro that affects telomere behavior in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 13760–13765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingner J., Cech,T.R., Hughes,T.R. and Lundblad,V. (1997) Three Ever Shorter Telomere (EST) genes are dispensable for in vitro yeast telomerase activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 11190–11195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Mao,X. and Lustig,A.J. (1994) Mutational analysis defines a C-terminal tail domain of RAP1 essential for telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 138, 1025–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.P. and Tye,B.K. (1991) A yeast protein that binds to vertebrate telomeres and conserved yeast telomeric junctions. Genes Dev., 5, 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M.S., Wilson,N.M., Petracek,M.E. and Berman,J. (1989) A yeast telomere binding activity binds to two related telomere sequence motifs and is indistinguishable from RAP1. Curr. Genet., 16, 225–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad V. and Szostak,J.W. (1989) A mutant with a defect in telomere elongation leads to senescence in yeast. Cell, 57, 633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad V. and Blackburn,E.H. (1993) An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est-senescence. Cell, 73, 347–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig A.J., Kurtz,S. and Shore,D. (1990) Involvement of the silencer and UAS binding protein RAP1 in regulation of telomere length. Science, 250, 549–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcand S., Gilson,E. and Shore,D. (1997) A protein-counting mechanism for telomere length regulation in yeast. Science, 275, 986–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C., Ciosk,R. and Nasmyth,K. (1997) Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell, 91, 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti P., Freeman,K., Coodly,L. and Shore,D. (1994) Evidence that a complex of SIR proteins interacts with the silencer and telomere-binding protein RAP1. Genes Dev., 8, 2257–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmo E.R., Pidoux,A.L., Perry,P.E. and Allshire,R.C. (1998) Defective meiosis in telomere-silencing mutants of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature, 392, 825–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent C.I. and Lundblad,V. (1998) The telomerase reverse transcriptase: components and regulation. Genes Dev., 12, 1073–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent C.I., Hughes,T.R., Lue,N.F. and Lundblad,V. (1996) Cdc13p: a single-strand telomeric DNA-binding protein with a dual role in yeast telomere maintenance. Science, 274, 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennock E., Buckley,K. and Lundblad,V. (2001) Cdc13 delivers separate complexes to the telomere for end protection and replication. Cell, 104, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H. and Zakian,V.A. (2000) The Saccharomyces telomere-binding protein Cdc13p interacts with both the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase α and the telomerase-associated Est1 protein. Genes Dev., 14, 1777–1788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell L.L. and Zakian,V.A. (1993) Loss of a yeast telomere: arrest, recovery and chromosome loss. Cell, 75, 729–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherthan H. (2001) A bouquet makes ends meet. Nat. Rev., 2, 621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild D., Calderon,I.L., Contopolou,R. and Mortimer,R.K. (1983) Cloning of yeast recombination repair genes and evidence that several are nonessential genes. In Friedberg,E.C. and Bridges,B.A. (eds), UCLA Symposia on Molecular and Cellular Biology. Vol. 11. A.R.Liss, Keystone, Colorado, CO, pp. 417–427.

- Shore D. (2001) Telomeric chromatin: replicating and wrapping up chromosome ends. Curr. Opin. Genet. Devel., 11, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore D., Stillman,D.J., Brand,A.H. and Nasmyth,K.A. (1987) Identification of silencer binding proteins from yeast: possible roles in SIR control and DNA replication. EMBO J., 6, 461–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R.S. and Hieter,P. (1989) A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 122, 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart A.K.P., Teng,S.-C. and Zakian,V.A. (2002) Est1p as a cell cycle-regulated activator of telomere-bound telomerase. Science, 297, 1023–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng S.-C. and Zakian,V.A. (1999) Telomere–telomere recombination is an efficient bypass pathway for telomere maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 8083–8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng S.-C., Chang,J., McCowan,B. and Zakian,V.A. (2000) Telomerase-independent lengthening of yeast telomeres occurs by an abrupt Rad50p-dependent, Rif-inhibited recombinational process. Mol. Cell, 6, 947–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham W.H. and Zakian,V.A. (2002) Transcriptional silencing at Saccharomyces telomeres: implications for other organisms. Oncogene, 21, 512–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham W.H., Wyithe,J.S., Ferrigno,P.K., Silver,P.A. and Zakian,V.A. (2001) Localization of yeast telomeres to the nuclear periphery is separable from transcriptional repression and telomere stability functions. Mol. Cell, 8, 189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trelles-Sticken E., Loidl,J. and Scherthan,H. (1999) Bouquet formation in budding yeast: initiation of recombination is not required for meiotic telomere clustering. J. Cell Sci., 112, 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trelles-Sticken E., Dresser,M.E. and Scherthan,H. (2000) Meiotic telomere protein Ndj1p is required for meiosis-specific telomere distribution, bouquet formation and efficient homologue pairing. J. Cell Biol., 151, 95–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto Y., Taggart,A.K.P. and Zakian,V.A. (2001) The role of the Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 complex in telomerase-mediated lengthening of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomeres. Curr. Biol., 11, 1328–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.S., Pluta,A.F. and Zakian,V.A. (1989) DNA sequence analysis of newly formed telomeres in yeast. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res., 318, 81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotton D. and Shore,D. (1997) A novel Rap1p-interacting factor, Rif2p, cooperates with Rif1p to regulate telomere length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev., 11, 748–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J.H., Gottschling,D.E. and Zakian,V.A. (1992) Saccharomyces telomeres assume a non-nucleosomal chromatin structure. Genes Dev., 6, 197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]