Abstract

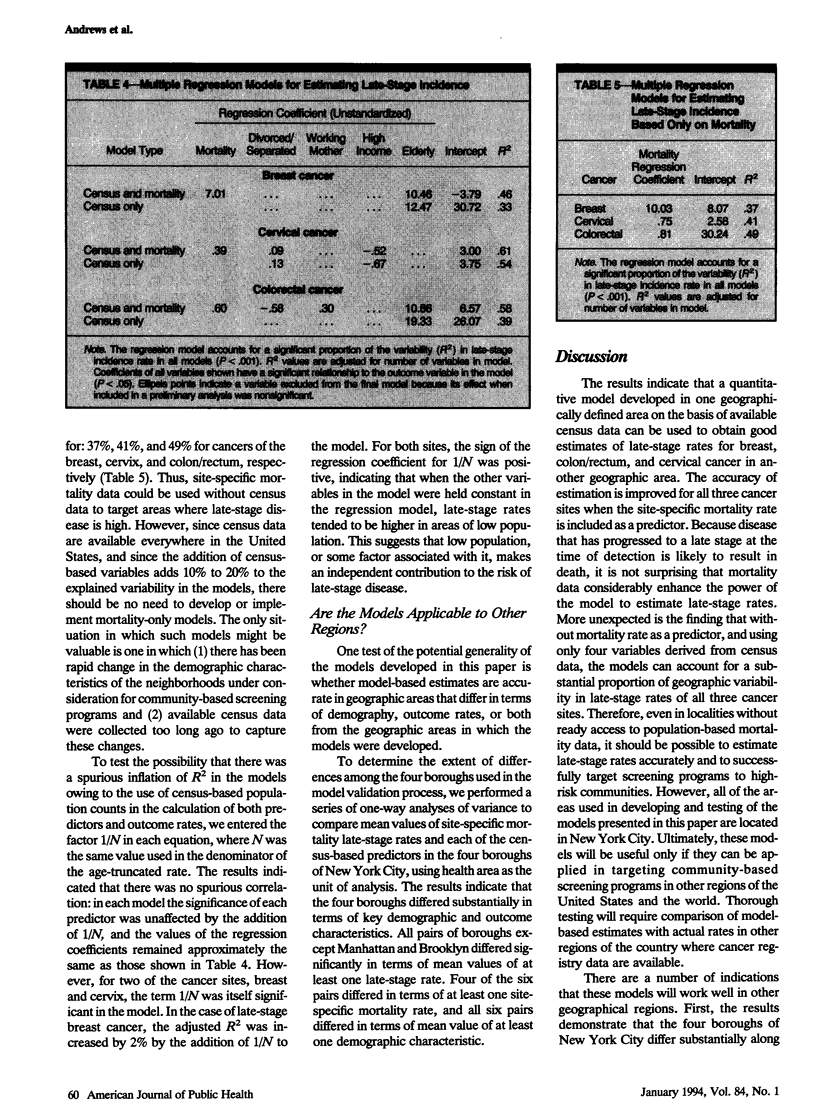

OBJECTIVES: The goal of this study was to develop and validate quantitative models for estimating cancer incidence in small areas. METHODS. The outcome for each cancer site was the incidence of disease that had reached a late stage at the time of diagnosis. Two sets of predictors were used: (1) census-based demographic variables and (2) census-based demographic variables together with the cancer-specific mortality rate. RESULTS. The best models accounted for a substantial percentage of between area variability in late-stage rates for cancer of the breast (46%), cervix (61%), and colon/rectum (58%). A validation procedure indicated that correct identification of small areas with high rates of late-stage disease was two to three times more likely when model-based estimates were used than when areas were selected at random. CONCLUSIONS. Additional testing is needed to establish the generality of the geographic targeting methodology developed in this paper. However, there are strong indications that small-area estimation models will be useful in many regions where planners wish to target cancer screening programs on a geographic basis.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baquet C. R., Horm J. W., Gibbs T., Greenwald P. Socioeconomic factors and cancer incidence among blacks and whites. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991 Apr 17;83(8):551–557. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.8.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehr P., Cain K., Connell F., Volinn E. What is too much variation? The null hypothesis in small-area analysis. Health Serv Res. 1990 Feb;24(6):741–771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehr P., Grembowski D. A small area simulation approach to determining excess variation in dental procedure rates. Am J Public Health. 1990 Nov;80(11):1343–1348. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.11.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner J. F., Andrews H., Zauber A., Struening E. Geographically-based cancer control: methods for targeting and evaluating the impact of screening interventions on defined populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(6):543–553. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelblatt J., Andrews H., Kerner J., Zauber A., Burnett W. Determinants of late stage diagnosis of breast and cervical cancer: the impact of age, race, social class, and hospital type. Am J Public Health. 1991 May;81(5):646–649. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman J., Andrews H., Struening E. The use of zip coded population data in social area studies of service utilization. Eval Program Plann. 1986;9(4):309–317. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(86)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struening E. L., Wallace R., Moore R. Housing conditions and the quality of children at birth. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1990 Sep-Oct;66(5):463–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace R., Wallace D. Origins of public health collapse in New York City: the dynamics of planned shrinkage, contagious urban decay and social disintegration. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1990 Sep-Oct;66(5):391–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]