Abstract

Extracellular Zn2+ has been identified as an activator of pancreatic KATP channels. We further examined the action of Zn2+ on recombinant KATP channels formed with the inward rectifier K+ channel subunit Kir6.2 associated with either the pancreatic/neuronal sulphonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1) subunit or the cardiac SUR2A subunit. Zn2+, applied at either the extracellular or intracellular side of the membrane appeared as a potent, reversible activator of KATP channels. External Zn2+, at micromolar concentrations, activated SUR1/Kir6.2 but induced a small inhibition of SUR2A/Kir6.2 channels. Cytosolic Zn2+ dose-dependently stimulated both SUR1/Kir6.2 and SUR2A/Kir6.2 channels, with half-maximal effects at 1.8 and 60 μm, respectively, but it did not affect the Kir6.2 subunit expressed alone. These observations point to an action of both external and internal Zn2+ on the SUR subunit. Effects of internal Zn2+ were not due to Zn2+ leaking out, since they were unaffected by the presence of a Zn2+ chelator on the external side. Similarly, internal chelators did not affect activation by external Zn2+. Therefore, Zn2+ is an endogenous KATP channel opener being active on both sides of the membrane, with potentially distinct sites of action located on the SUR subunit. These findings uncover a novel regulatory pathway targeting KATP channels, and suggest a new role for Zn2+ as an intracellular signalling molecule.

Zinc is an essential component of many proteins. As a cofactor or as a key structural element, it is required for enzyme catalysis and is involved in gene transcription or metalloenzyme function (Vallee & Falchuk, 1993). Ionic zinc is also an important factor involved in cell–cell communication, notably in the nervous and endocrine systems. Indeed, Zn2+ has been shown to accmulate in synaptic vesicles or secretion granules and to be coreleased with neurotransmitters and hormones (Huang, 1997; Dodson & Steiner, 1998; Frederickson & Bush, 2001). In glutamatergic neurones, Zn2+ is secreted with glutamate during neuronal activity and is believed to act as a modulator of synaptic transmission (Huang, 1997; Lin et al. 2001).

In pancreatic beta-cells, Zn2+ is necessary to maintain the crystalline structure of insulin in secretory granules (Dodson & Steiner, 1998), and has been proposed to exert a negative feedback upon hormone release by reducing the electrical activity and insulin secretion of beta-cells (Ghafghazi et al. 1981; Ferrer et al. 1984; Aspinwall et al. 1997). These actions of Zn2+ are likely to result from direct interaction with membrane ion channels (Harrison & Gibbons, 1994; Smart et al. 1994; Frederickson & Bush, 2001).

Bloc et al. (2000) proposed that the inhibitory effect of Zn2+ on insulin secretion from pancreatic beta-cells could result at least partly from its potentiating action on ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP). These channels are widely distributed among most types of excitable cells, where they couple metabolic status to membrane excitability (Ashcroft & Ashcroft, 1990; Seino & Miki, 2003). In pancreatic beta-cells, KATP channels are involved in glucose-induced insulin secretion whereas in cardiac and neuronal cells, they could have a protective effect against ischaemic damage (Standen, 2002). The KATP channel is a hetero-octameric complex composed of two distinct proteins: the sulphonylurea receptor (SUR), an ATP-binding-cassette (ABC) protein, and an inward rectifier potassium channel, Kir6.x. In pancreatic and cardiac KATP channels, four Kir6.2 assemble to form a K+-selective pore, which is constitutively associated with four SUR subunits (Seino & Miki, 2003). SUR serves as a sensor of metabolic adenine nucleotide changes and is the target of pharmacological modulators of the channel: blockers, like the sulphonylureas, and potassium channel openers such as cromakalim and pinacidil. Pancreatic and neuronal KATP channels contain the SUR1 isoform, whereas the channel in cardiac and skeletal muscle cells is formed with the SUR2A isoform (Terzic & Vivaudou, 2001).

Apart from its extracellular action, Zn2+ can also enter cells via various routes and act as an intracellular messenger (Li et al. 2001; Frederickson & Bush, 2001). Zn2+ can permeate membranes either directly through ligand-gated channels such as glutamate or nicotinic receptors (Sensi et al. 1997; Ragozzino et al. 2000; Jia et al. 2002), voltage-activated Ca2+ channels (Kerchner et al. 2000; Sheline et al. 2002) and other channels (Monteilh-Zoller et al. 2003), or through transporters (Weiss et al. 2000; Gaither & Eide, 2001). Entry of Zn2+ may alter protein structure and function, as well as gene expression (Weiss et al. 2000; Frederickson & Bush, 2001), but may also modulate channels from the intracellular compartment (Tabata & Ishida, 1999; Wang et al. 2001).

We here report the potentiation of KATP channels by intracellular Zn2+, and compare it with that induced by extracellular application of Zn2+ (Bloc et al. 2000). We further investigate these effects of Zn2+ as a function of the subunit composition of the channel and show that, on either side of the membrane, SUR is the most probable target of Zn2+.

Methods

Cell culture and heterologous expression

Clones

Rat Kir6.2 (GenBank accession X97041) and rat SUR1 (GenBank accession X97279) cDNAs were cloned from the rat insulinoma cell line RINm5F, using a RT-PCR-based strategy. Rat SUR2A cDNAs (GenBank accession D83598) and mouse Kir6.2 (GenBank accession D50581) were kindly provided by Dr S. Seino. Hamster SUR1 (GenBank accession L40623) was kindly provided by Dr J. Bryan.

Cell lines

For expression in COS-7 cells, rat Kir6.2, SUR1, and SUR2A cDNAs were subcloned into the expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). Transfections were performed overnight by CaCl2 precipitation with 4 μg per well of Kir6.2 + SURx combinations (ratio 1:3), together with 0.5 μg of vector pE-GFP (Invitrogen). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were plated and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) for 1–3 days before recordings. Cells expressing GFP were identified by fluorescence microscopy and used for electrophysiology.

Xenopus oocyte expression

Mouse Kir6.2, hamster SUR1 and rat SUR2A were subcloned in Xenopus oocyte expression vectors derived from the vector pGEMHE (Liman et al. 1992). Mutations were introduced in these plasmids by PCR (QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, Stratagene). For the Kir6.2ΔC36 construct, a premature stop codon was introduced at the correct position. After amplification and linearization, plasmid DNAs were transcribed in vitro by using the T7 mMessage mMachine Kit (Ambion) to produce cRNA for subsequent oocyte microinjection.

Female Xenopus laevis were anaesthetized with 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (1 g l−1 of water). Part of one ovary was removed with a minilaparotomy, the incision was sutured, and the animal was allowed to recover. Animal handling and experiments fully conformed with French regulations and were approved by local governmental veterinary services (authorization No. 28-03-15 delivered by the Ministère de l'Agriculture, Direction des Services Vétérinaires to M.V). Frogs were humanely killed by decapitation after final collection of oocytes from both ovaries.

Stage V or VI oocytes were defolliculated by a 60-min incubation at 19°C with 2 mg ml−1 type A collagenase (Sigma). Selected oocytes were injected the next day with cRNAs encoding wild-type or truncated Kir6.2 (2 ng) and wild-type or modified SURs (6 ng). Injected oocytes were stored at 19°C in Barth's solution (in mm: 1 KCl, 0.82 MgSO4, 88 NaCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 0.41 CaCl2, 0.3 Ca(NO3)2, 16 Hepes, pH 7.4) supplemented with 100 U ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 100 μg ml−1 gentamycin. Three to five days after injection, oocytes were devitellinized and recombinant KATP channels were characterized by the patch-clamp technique in the excised inside-out or outside-out configuration.

Electrophysiology

All experiments were carried out at room temperature (20–22°C). ATP-containing solutions were prepared immediately before the experiments. Diazoxide, tolbutamide and glibenclamide (Sigma) were diluted to their final concentrations from stock solutions in DMSO at 100, 100, and 20 mm, respectively. At the concentrations used, DMSO had no effect on channel activity (D'hahan et al. 1999a). The indicated concentrations of Zn2+ (chloride salt; Fluka) represent free zinc as calculated by the program ALEX (Vivaudou et al. 1991). In our experimental conditions, ATP was the only Zn2+ complexant. Since Zn2+ binds to ATP with a dissociation constant ∼15 μm, we used Zn2+ concentrations low enough to limit effects due solely to interactions with ATP. Thus in our experimental conditions, the fraction of ATP complexed with Zn2+ was at most 11% (a value reached when 31 μm Zn was mixed with 100 μm ATP to yield 20 μm free Zn2+ and 11 μm ZnATP2−).

Cell lines

For whole-cell recording, the external bath solution contained (mm): 145 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 10 d-glucose, pH 7.2, and patch pipettes (2–3 MΩ) contained (in mm): 10 NaCl, 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 1 EGTA, 1 Mg-ATP, pH 7.2. In the inside-out configuration, bath and pipette (5–10 MΩ) solutions were identical with (in mm): 10 NaCl, 140 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, pH 7.2. Applications of the various solutions were performed using a gravity solution-changer controlled by electrovalves. Capacitive transients and series resistance were compensated. Signals were analysed with pClamp8 software (Axon Instruments).

Xenopus oocytes

For inside-out recordings, patch pipettes (2–10 MΩ) contained (mm): 136 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 10 PIPES, 18 KOH, pH 7.1. DTPA (diethyle-netriaminepentaacetic acid; Sigma) and EGTA were added when specified. Patches were bathed in solutions that contained (in mm): 38 KCl, 92 KCH3SO3, 1 MgCl2, 10 PIPES, 20 KOH, pH 7.1. Except where noted, EGTA was used at 1 mm. ATP (potassium salt; Sigma) was added as specified. For outside-out recordings, above pipette and bath solutions were switched to yield the same intra- and extracellular solutions. Unless otherwise specified, experiments were conducted at the Cl− reversal potential (∼−30 mV) determined for each patch as the potential at which no current was induced by the removal of the Ca2+ chelator EGTA. Applications of the various solutions to the patch were performed using an RSC-100 rapid-solution-changer (Bio-Logic). Acquisition and analysis were performed with in-house software. Slow fluctuations of the baseline were removed by interactive fitting with a spline curve and subtraction of this fit from the signal. Single channel analysis (all-point histograms and fits) were performed with Origin software (OriginLab). Open probability was calculated as the overall time spent in open states over total recording time. Model fitting to the currents measured in 100 μm ATP normalized to the current measured in 0 ATP was done with Origin using a standard Hill equation:

where i0 is the control normalized current in absence of Zn2+, K½ the concentration for half-maximal inhibition and n the Hill coefficient.

Results are displayed as the mean ± s.e.m.

Results

Extracellular Zn2+ activates recombinant pancreatic KATP channels

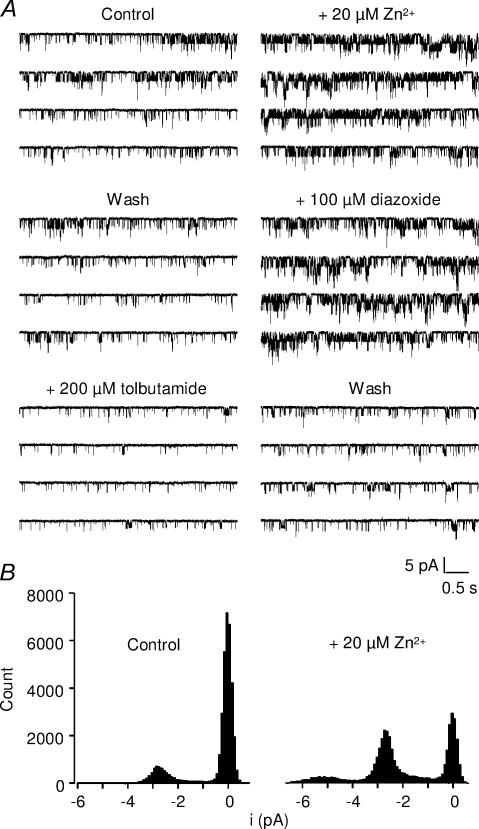

Previous experiments showed that extracellular Zn2+ activates KATP channels in the pancreatic cell line RIN5mF (Bloc et al. 2000). In order to better understand the effects of Zn2+ on KATP channels, experiments were conducted on recombinant KATP channels formed with the pancreatic combination of subunits SUR1 and Kir6.2. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed on COS-7 cells transfected with SUR1/Kir6.2 (Fig. 1). Large currents elicited by slow voltage ramps were suppressed in the presence of the SUR1-selective KATP blocker tolbutamide (300 μm) and reversed close to the K+ equilibrium potential. These currents were potentiated by bath application of Zn2+ (20 μm). Potentiation was absent in the presence of tolbutamide, confirming that Zn2+ activated KATP currents. On average, 20 μm Zn2+ potentiated the current measured at −40 mV by 42 ± 9% (Fig. 1C), a value similar to that reported for native channels of RIN5mF cells (Bloc et al. 2000). Similarly, outside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes expressing SUR1/Kir6.2 showed channel activity that was enhanced both by the SUR1 opener diazoxide (100 μm) and by bath application of Zn2+ (20 μm), and was inhibited by tolbutamide (200 μm; Fig. 2A). The increase in open probability (Po) was variable from patch to patch, depending on the initial level of activity of the channels. On average, Po increased from 0.22 ± 0.06 to 0.42 ± 0.07 (131 ± 40% increase; n = 6).

Figure 1. Differential effect of extracellular Zn2+ on SUR1/Kir6.2 and SUR2A/Kir6.2 whole-cell currents.

A, sulphonylurea-sensitive currents are activated by zinc in cells expressing SUR1/Kir6.2 but not in cells expressing SUR2A/Kir6.2. Whole-cell currents of COS-7 cells transfected with Kir6.2 and either SUR1 or SUR2A were elicited by voltage ramps from −120 to −40 mV (holding potential =−80 mV). Conductances were measured by fitting the ramp currents with a linear regression line between −100 mV and −60 mV and plotted as a function of time. The KATP channel blockers used here were tolbutamide for SUR1 and glibenclamide for SUR2A. B, relative effects of 20 μm extracellular Zn2+ on KATP currents as a function of subunit composition, measured at a holding potential of −40 mV. C and D, ramp protocol used for experiments of panel A and representative current recordings taken at the different times indicated by the circled numbers in A.

Figure 2. Activation by extracellular Zn2+ of single SUR1/Kir6.2 channels.

A, recordings of KATP channels in outside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes expressing SUR1/Kir6.2 channels, at a holding potential of −43 mV with 300 μm ATP in the pipette. Single-channel activity was strongly enhanced by 20 μm extracellular Zn2+. Channels were also activated by diazoxide and inhibited by tolbutamide. B, amplitude histograms of the recordings shown in A, top traces, in the absence and in the presence of Zn2+. Zn2+ increased open probability with no change in single-channel current amplitude.

The effect of extracellular Zn2+ depends on the SUR subunit

In order to assess which subunit was responsible for the potentiating effect of Zn2+, we also tested Zn2+ on cells expressing the cardiac isoform of the channel composed of the SUR2A and Kir6.2 subunits. The cardiac SUR2A/Kir6.2 channel is characterized by a lower sensitivity to sulphonylureas than the pancreatic form of the channel (SUR1/Kir6.2), and is activated by openers such as cromakalim and pinacidil, but not by diazoxide (in absence of internal ADP; D'hahan et al. 1999b).

In contrast to its action on SUR1/Kir6.2 channel, application of 20 μm extracellular Zn2+ did not potentiate the SUR2A/Kir6.2 channel expressed either in COS-7 cells (n = 12; Fig. 1) or in Xenopus oocytes (n = 4 outside-out patches, data not shown). Rather, Zn2+ induced a small reversible inhibition of the KATP current (Fig. 1). This indicates that the SUR subunit is critical to extracellular Zn2+ action, with a specificity towards SUR1-containing channels.

Modulation of recombinant KATP channels by intracellular Zn2+

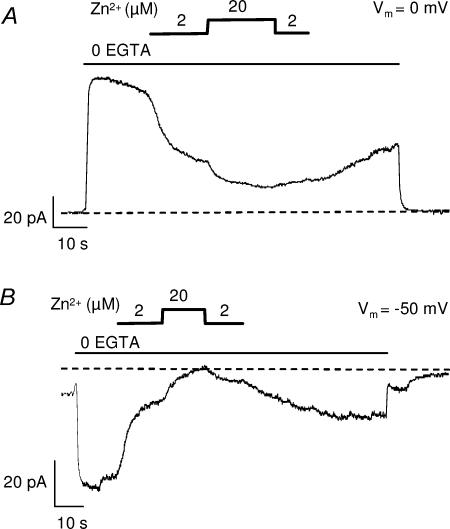

Unexpectedly, Zn2+ applied to the intracellular face of the channel also had profound effects on channel activity. Characterization of this effect was performed on Xenopus oocytes coinjected with SUR and Kir6.2, from which KATP currents of hundreds of pA can be recorded in a single patch (D'hahan et al. 1999a). In Xenopus oocytes, inside-out patch recordings are routinely performed in the presence of the Ca2+ chelator EGTA in the bath to prevent activation by residual Ca2+ of endogenous Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (ICl(Ca)). Because EGTA also chelates Zn2+, application of Zn2+ requires removal of EGTA from the bath solution, and experiments were therefore conducted at the Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) to prevent contamination by ICl(Ca). ECl was precisely measured in each patch as the membrane potential at which no current was induced by removal of EGTA. These precautions were necessary because Zn2+ was found to block the endogenous ICl(Ca) conductance, identified as such because it reversed at ECl and was activated by removal of EGTA. Intracellular Zn2+ (2 and 20 μm) had an inhibitory effect on Cl− current, reducing both the outward current at 0 mV and the inward currents at −50 mV (Fig. 3). At ECl, the potential used to record KATP channels, Zn2+ had no effect in uninjected oocytes.

Figure 3. Effect of intracellular Zn2+ on endogenous Ca2+-activated Cl− currents of Xenopus oocytes.

Currents recorded at a membrane potential of 0 mV (A) and −50 mV (B) from inside-out patches excised from non-injected oocytes. On the cytosolic side, in the continuous presence of 100 μm ATP, removal of EGTA triggered activation of large currents reversing at ECl (−30 mV) which were blocked by Zn2+.

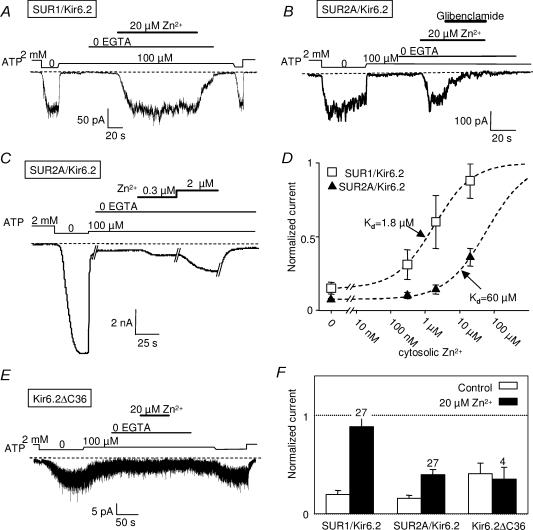

In the presence of a concentration of ATP (100 μm) sufficient to produce ∼80% channel inhibition, bath application of 20 μm Zn2+ activated both SUR1/Kir6.2 and SUR2A/Kir6.2 KATP channels (Fig. 4A and B). Potentiation by Zn2+ was dose dependent (Fig. 4C), with a clearly greater affinity for SUR1/Kir6.2 than SUR2A/Kir6.2 channels (Fig. 4D). Since Zn2+ concentrations above 20 μm could not be used for fear of indirect effects due to ATP chelation (see Methods), the degree of maximal activation could not be ascertained. Assuming channel activity could be raised by Zn2+ to the level obtained in the absence of ATP, Hill equation fitting yielded K½ of 1.8 and 60 μm for SUR1 and SUR2A, respectively (Fig. 4D). These values became 1.3 and 5.1 μm if the levels obtained in 20 μm Zn2+ were taken as maximal.

Figure 4. Effect of intracellular Zn2+ on recombinant pancreatic and cardiac KATP channels.

Channel activity was measured at −30 mV in inside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes coinjected with Kir6.2 and SUR1 or SUR2A. A, activation by 20 μm Zn2+ of SUR1/Kir6.2 channels. B, as for A but with SUR2A/Kir6.2. Zn2+-activated currents were blocked by 10 μm glibenclamide. C, dose-dependent effect of intracellular Zn2+ on SUR2A/Kir6.2 channels. D, average SUR1 and SUR2A/Kir6.2 currents in 100 μm ATP, measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of Zn2+. Currents are normalized to the current measured in absence of ATP. The data were collected from 17 (SUR1) and 9 (SUR2A) patches in which at least two concentrations of Zn2+ were tested sequentially. Best fits with a Hill equation (see Methods), represented by the dashed lines, yielded K½ = 1.8 μm and n = 0.78 for SUR1 and K½ = 60 μm and n = 0.74 for SUR2A. E, effect of intracellular Zn2+ on Kir6.2 modified to be expressed alone (Kir6.2ΔC36). F, average currents in 100 μm ATP (normalized to current obtained in 0 ATP) measured before or during application of 20 μm Zn2+. Numbers above bars indicate the number of patches included in the average.

To identify the subunit, SUR or Kir6.2, which is the target of intracellular Zn2+, experiments were conducted on a truncated form of Kir6.2, Kir6.2ΔC36, from which the last 36 amino acids were deleted (Tucker et al. 1997), removing the endoplasmic reticulum retention signal present on the C-terminal extremity (Zerangue et al. 1999). This allows the expression at the plasma membrane of functional channels formed solely by the Kir6.2 subunit, albeit at a lower density than wild-type KATP channels. Application of internal Zn2+ (20 μm) on inside-out patches from oocytes expressing Kir6.2ΔC36 channels, either in the absence (data not shown) or in the presence of ATP (100 μm), caused a slight reduction in current which was not statistically significant (P > 0.2; Student's paired t test). These results point to the SUR protein as the target of both extra- and intracellular Zn2+.

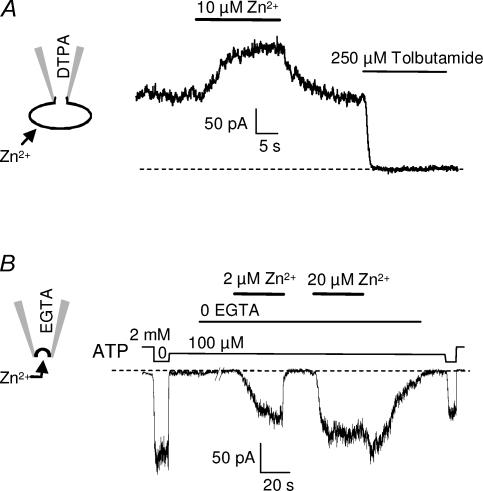

The bilateral effects of Zn2+ do not entail crossmembrane transit

Although it would be unlikely in our recording configurations, the possibility exists that Zn2+ could somehow cross the membrane to reach its site of action, thus explaining how internal and external Zn2+ can have similar effects. In order to test for such a mechanism, experiments were reproduced in the presence of the Zn2+ chelators EGTA (100 μm; n = 3) or DTPA (100 μm; n = 5) in the patch pipette. Neither chelator on the intracellular face prevented the extracellular effect of Zn2+, which still increased SUR1/Kir6.2 currents to a similar extent (Fig. 5A). Similarly, the presence of the chelators DTPA (100 μm; n = 3) or EGTA (100 μm; n = 9) on the extracellular side of the membrane did not prevent the increase in KATP currents induced by application of Zn2+ on the intracellular side of the membrane (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Activation by Zn2+ on either side of the membrane is unaffected by the presence of chelators on the opposite side.

A, whole-cell recording from a COS-7 cell expressing SUR1/Kir6.2 channels, in the presence of 100 μm DTPA added to the pipette solution. The Zn2+ chelator inside the cell did not prevent the potentiation by extracellular Zn2+. Holding potential is −40 mV. B, current recorded at −30 mV from an inside-out patch excised from a Xenopus oocyte coinjected with SUR1 and Kir6.2, with 100 μm EGTA added to the pipette solution. The presence of the chelator on the extracellular side of the membrane did not alter channel activation by intracellular Zn2+.

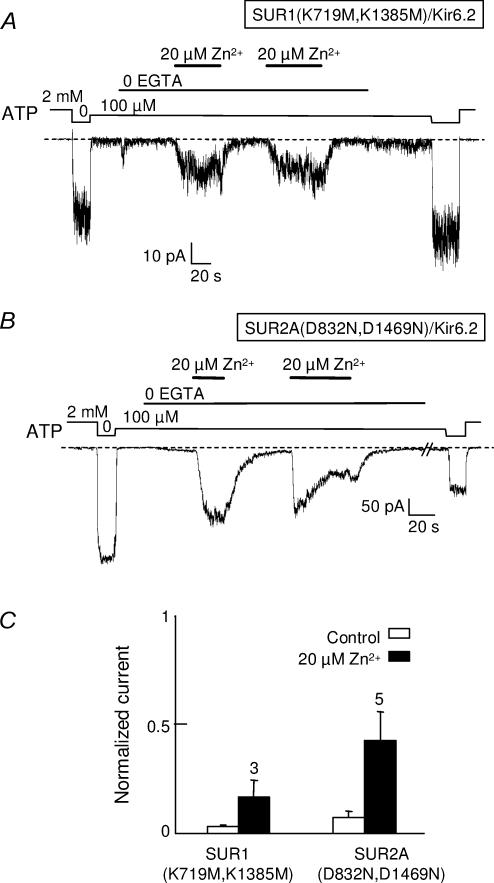

These observations make it unlikely that Zn2+ could cross the membrane and reach its target by diffusion. They do not dispel an alternative mechanism where a single target site would be accessible from either side of the membrane through a protein-delimited pathway. Indeed, SUR presents strong homologies with other ATP-binding-cassette (ABC) proteins like Ycf1p, which are known to transport heavy metals, including divalent cations such as Cd2+ (Li et al. 1997). Although SUR has no known transport activity, it might, like Ycf1p, possess metal-binding sites accessible from both sides of the membrane in a nucleotide-dependent manner. We therefore investigated the responses to Zn2+ of channels incorporating debilitating mutations in both nucleotide-binding domains of either SUR1 or SUR2A. The key residues targeted were either the Walker A lysines of SUR1 (K719 and 1385) or the Walker B aspartates of SUR2A (D832 and 1469). As is obvious in Fig. 6, both mutants retained the capacity to be activated by internal Zn2+ although the extent of activation was diminished for the SUR1 mutant.

Figure 6. KATP channels with impaired nucleotide binding domains are still activated by intracellular Zn2+.

Channel activity was measured at −30 mV in inside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes coinjected with Kir6.2 and SUR1(K719M,K1385M) or SUR2A(D832N,D1469N). A, activation by 20 μm Zn2+ of SUR1(K719M,K1385M)/Kir6.2 channels. B, average currents in 100 μm ATP measured before or during application of 20 μm Zn2+. Currents were normalized to the current measured in the absence of ATP. Numbers above bars indicate the number of patches included in the average.

Discussion

The results presented here identify Zn2+ as a unique endogenous regulator of KATP channels, able to activate them reversibly at low concentrations from either side of the membrane in an isoform-dependent manner. They suggest a new role for Zn2+ as an intracellular signalling molecule (Maret, 2001).

Inhibition of Xenopus oocyte Ca2+-activated Cl− currents by Zn2+

During the course of this work, we discovered that intracellular Zn2+ inhibited the most prominent endogenous currents of Xenopus oocytes, Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (ICl(Ca)). Previous studies have reported that micromolar concentrations of extracellular divalent cations, including Zn2+, induced ICl(Ca) in Xenopus oocytes, but that internal injections of Zn2+ had no effect (Miledi et al. 1989). However, when applied onto excised patches, intracellular Zn2+ (2–20 μm) inhibited a current identified as ICl(Ca) by its activation upon EGTA removal and its reversal at the predicted Cl− equilibrium potential. Although we did not further characterize this effect, which represented the only effect of Zn2+ on endogenous conductances under our experimental conditions, we did consider it carefully when recording effects of Zn2+ on KATP channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Ionic concentrations were adjusted to have ECl (∼−30 mV) and EK (∼0 mV) sufficiently distant so that sizable K+ currents could be measured at ECl. Furthermore, the actual ECl was determined in each patch to within 1 mV, as the reversal potential of ICl(Ca). In this manner, effects of intracellular Zn2+ on endogenous Cl− and exogenous K+ conductances could be characterized separately with minimal interference.

Pancreatic KATP channels are activated by extra- and intracellular Zn2+

Bloc et al. (2000) reported that micromolar concentrations of Zn2+ increased the open-state probability of endogenous KATP channels in the pancreatic RIN5mF cell line. We substantiated this observation by showing that extracellular Zn2+ also activated recombinant SUR1/Kir6.2 channels heterologously expressed in either COS-7 cells or Xenopus oocytes. Potentiation was rapid, reaching its maximum within a few seconds, and reversed with similarly fast kinetics.

Unexpectedly, application of Zn2+ to the intracellular side of the membrane also led to activation of KATP channels. Intracellular Zn2+ at submicromolar concentrations has been shown to inhibit Cl− channels in neurones (Tabata & Ishida, 1999), but to our knowledge, this is the first observation of the agonist effect of an internal transition metal on identified potassium channels, (Miledi et al. (1989) did report activation by high external Zn2+ of a K+ conductance in Xenopus oocyte follicular cells), and the first reported case of a channel activated by a non-permeant ligand from both sides of the membrane. For SUR1/Kir6.2 channels expressed in oocytes, measurements over a number of experiments gave a half-maximal concentration of 1.8 μm but there were significant differences in the responses of individual patches. This value is remarkably close to the value of 1.7 μm measured under different experimental conditions as being the concentration for half-maximal activation by extracellular Zn2+ (Bloc et al. 2000). The amplitude of the effect was comparable to that of pharmaceutical potassium channel openers since, in most patches, 20 μm Zn2+ was sufficient to fully reverse the inhibition caused by the 100 μm ATP present during our tests.

Isoform-dependent modulation of KATP channels by extracellular and intracellular Zn2+

The potentiation of KATP channels by extracellular Zn2+ appeared specific to the pancreatic channel, since Zn2+ failed to activate the cardiac form of KATP channels (SUR2A/Kir6.2), and even elicited a weak inhibition of these channels at the highest concentration tested of 20 μm. Kwok & Kass (1993) showed that such a concentration also inhibited native channels but to a much greater extent. Since they recorded Zn2+ effects on pinacidil-activated currents, the discrepancy could arise from a possible antagonism between K+ channel openers and Zn2+, not unlike that between openers and protons (Forestier et al. 1996).

Kwok & Kass (1993) also tested internal Zn2+ on ventricular myocyte channels and, even though they concluded a lack of inhibition, an activation, evident in their Fig. 4, could have been overlooked. In our hands, intracellular Zn2+ activated both the pancreatic and cardiac forms of KATP channels with a strong preference for the former. This dose-dependent effect, when modelled with sigmoidal functions, yielded K½ in the range of 1–2 μm for SUR1/Kir6.2 and 5–60 μm for SUR2A/Kir6.2 channels. In both cases, the Hill coefficient was close to 1, indicative of a simple bimolecular reaction. This SUR-dependent difference, together with the lack of effects of Zn2+ on truncated Kir6.2 channels expressed alone, designates the sulphonylurea receptor as the primary target of intracellular Zn2+.

Possible mechanisms for Zn2+ potentiation of KATP currents

The first hypothesis that one could put forward about the effects of Zn2+ is that of an unspecific action related to the ionic nature of the effector. However, no such effects have been described for the other physiological divalent cations, Mg2+ and Ca2+. Furthermore, Zn2+ effects were recorded in the presence of Mg2+, present on both sides of the membrane throughout our experiments in large excess (>1 mm), and Ca2+, present outside in millimolar concentrations and inside in micromolar concentrations (as evidenced by the potent activation of ICl(Ca) upon removal of the chelator EGTA). A mechanism involving alterations of membrane surface charge (Vivaudou & Forestier, 1995) is therefore implausible. Likewise, interaction of intracellular Zn2+ with nucleotides could not lead to significant activation: first, Zn2+ will reduce free ATP by chelating it, possibly affecting the inhibitory potency of ATP on the Kir6.2 subunit, but our experimental conditions were designed to minimize this effect by keeping zinc-bound ATP at less than 11% of total ATP. Second, low concentrations of Mg–ATP have been shown to activate KATP channels through the SUR subunit (Gribble et al. 1998), but a similar effect of Zn–ATP would not be consistent with the available evidence demonstrating that Zn2+ cannot mimic Mg2+ in supporting nucleotide binding to ABC transporters (Cai et al. 2002).

This line of reasoning pleads for a more sophisticated mechanism involving Zn2+-specific receptor sites. The finding for SUR1 that the same molecule has the same, singular effects on an integral membrane protein when applied from either side of the membrane, intuitively suggests a single site of action. However, when we applied Zn2+ on one side, with a chelator on the other side, neither intra- nor extracellular effects were disturbed even though the concentration dependence of channel activation showed that Zn2+ has a 104-higher affinity for the chelator, EGTA or DTPA, than for its receptor. This experiment suggests that the intracellular Zn2+ site is not seen from outside and vice versa. This evidence favours the existence of two distinct sites mediating the same effect. These sites would be located near or on the SUR protein itself since, first, the effects were dependent on the SUR isoform and were not seen with SUR-less channels, and second, the rapid onset and reversal of Zn2+ activation appears incompatible with long-range signalling mechanisms, such as a receptor-regulated metabolic process involving the zinc-sensing receptor ZnR (Hershfinkel et al. 2001). This G-protein-coupled receptor linked to phospholipase C is probably present in Xenopus oocytes as this would nicely explain the effects of external Zn2+ recorded by Miledi et al. (1989). Activation of phospholipase C by ZnR would result in a decrease in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate which would increase ATP sensitivity of the KATP channels and cause an inhibition of the channel (Xie et al. 1999; Kakei, 2003). Such a mechanism could sustain the delayed inhibition subsequent to application of external Zn2+ observed by Bloc et al. (2000), but cannot account for a potentiating effect of Zn2+. Cytosolic Zn2+ interacts nonetheless with a number of enzymes (Beyersmann & Haase, 2001) one of which is protein kinase C (PKC), which has been linked to KATP channel activation (Light, 1996). With a Zn2+-dependent PKC having been reported to downregulate a Cl− conductance (Tabata & Ishida, 1999), a PKC role in intracellular Zn2+ activation of KATP channels cannot be ruled out but remains highly speculative because PKC activation of KATP channels depends on the Kir6.2 subunit (Light et al. 2000), but Zn2+ activation does not.

Considering a more direct pathway, the hypothesis of metal binding sites on SUR seems plausible because other IIb transition metals, such as Cd2+, can be transported by Ycf1p and Mrp1, ABC proteins that present a high degree of homology with SUR (Li et al. 1997; Tommasini et al. 1996), and because some prok aryotic ABC proteins are known to transport Zn2+ (Hantke, 2001). Zn2+ could even act as a substrate of SUR, not unlike the hypothesis raised for K+ channel openers (Moreau et al. 2000). However, SUR having mutations known to disable nucleotide-dependent transport activity of ABC transporters, retained sensitivity to Zn2+. This experiment argues against the necessity of a transport of Zn2+ for activating the channel, but it leaves open for further studies the possibility that a unique site of action of Zn2+ could lie within a transport pathway where chelators would not have access.

Physiological significance

In neurones, Zn2+ is concentrated in synaptic vesicles and cosecreted with neurotransmitters upon stimulation, and it is believed to act as a neuromodulator at excitatory synapses (Huang, 1997). In pancreatic beta-cells, Zn2+ accmulates in secretory granules, where it forms hexamers with insulin. These microcrystals dissolve during exocytosis and large amounts of Zn2+ are coreleased with insulin. It has been proposed that by activating KATP channels and hyperpolarizing cells, Zn2+ could exert a negative feedback on insulin secretion (Bloc et al. 2000). Aspinwall et al. (1999) have shown that released insulin stimulates insulin secretion via a positive feedback mechanism, and they suggested that some mechanism should take over to counteract this feedback. Stimulating KATP channels by Zn2+ coreleased with insulin could constitute one such mechanism. Zn2+ was also postulated to be responsible for the cross-talk between beta-cells and alpha-cells in pancreatic islets, whereas insulin secretion by beta-cells induces suppression of glucagon release by alpha-cells (Ishihara et al. 2003).

If extracellular Zn2+ can reach the micromolar levels used in this study (Weiss et al. 2000), intracellular free Zn2+ concentration is tightly controlled and maintained in the low nanomolar range (Sensi et al. 1997; Beyersmann & Haase, 2001). Since we have measured half-maximal activation of pancreatic/neuronal and muscle KATP channels at 1.8 and 60 μm, respectively, one could confidently conclude that cytosolic Zn2+ activation is a laboratory artefact that will never be seen under physiological conditions. The same could be said of ATP which inhibits KATP channels with micromolar affinities, but never goes below millimolar concentrations in living cells. Cook et al. (1988) settled that controversy by demonstrating that KATP channels can efficiently modulate membrane potential by operating at the very bottom of the dose–response curve for ATP, where inhibition is 99% or more. This argument applies to cytosolic Zn2+ activation as well: using the model curves fit to the data, it is predicted that 1% activation above control of SUR1/Kir6.2 and SUR2A/Kir6.2 can be achieved with 0.5 nm and 4 nm Zn2+, respectively. These concentrations are well within the limits of the feasible, without even postulating the existence of Zn2+-enriched microdomains which might well play a role due to tight coupling between KATP channels and Zn2+-permeant Ca2+ channels (Shibasaki et al. 2003).

What could then be the physiological role of intracellular Zn2+ potentiation of KATP channels? One possible role would be to protect cells against the cytotoxic effects of elevated internal Zn2+ (Kim et al. 2000; Frederickson & Bush, 2001). Depolarizing stimuli can drive Zn2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in the presence of physiological amounts of other cations, including Ca2+ in cardiac myocytes (Atar et al. 1995) or in neurones (Sensi et al. 1997; Kerchner et al. 2000). Maintaining cells hyperpolarized by opening KATP channels could thus prevent further entry of Zn2+ through Ca2+ channels, by keeping them from being activated. Such a scheme could reinforce the negative feedback effect of external Zn2+ on insulin secretion discussed above (Bloc et al. 2000). In cardiac myocytes, Zn2+ could act as an endogenous opener of KATP channels, reducing the force of contraction of the myocardium, and thus preventing ischaemia–reperfusion injury as do classical potassium channel openers (Terzic & Vivaudou, 2001).

In pancreatic beta-cells or neurones, an increase in cytosolic Zn2+ could potentially occur during perturbation of the Zn2+-accmulating machinery of secretory granules. This could happen during metabolic distress or after sustained secretion leading to penury of secretory granules and reduction in the cytosolic Zn2+-storage capacity of cells. In both cases, opening of KATP channels would provide a resting period for the cell by decreasing its excitability, thus reducing metabolic demand, and at the same time would decrease ambient Zn2+ by reducing secretion.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr J. Bryan (Houston, TX) for hamster SUR1, Dr S. Seino (Chiba, Japan) for mouse Kir6.2 and rat SUR2A, and to Dr C. Faure (Reuil-Malmaison, France) for the Kir6.2 and SUR1 clones used in the work on transfected cells. This work was made possible by grants from C.E.A. (Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique; programme Toxicologie nucléaire environnementale) and C.N.R.S. (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique). A grant from Swiss FNRS (Fonds National pour la Recherche Scientifique, no. 31–057135.99 to A.B) also supported this study. A.L.P and R.D. were recipients of doctoral and postdoctoral fellowships from C.E.A.

References

- Ashcroft SJH, Ashcroft FM. Properties and functions of ATP-sensitive K-channels. Cell Signal. 1990;2:197–214. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(90)90048-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall CA, Brooks SA, Kennedy RT, Lakey JR. Effects of intravesicular H+ and extracellular H+ and Zn2+ on insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31308–31314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall CA, Lakey JR, Kennedy RT. Insulin stimulated insulin secretion in single pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6360–6365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atar D, Backx PH, Appel MM, Gao WD, Marban E. Excitation–transcription coupling mediated by zinc influx through voltage-dependent calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2473–2477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyersmann D, Haase H. Functions of zinc in signaling, proliferation and differentiation of mammalian cells. Biometals. 2001;14:331–341. doi: 10.1023/a:1012905406548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloc A, Cens T, Cruz H, Dunant Y. Zinc-induced changes in ionic currents of clonal rat pancreatic beta-cells: activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. J Physiol. 2000;529:723–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Daoud R, Alqawi O, Georges E, Pelletier J, Gros P. Nucleotide binding and nucleotide hydrolysis properties of the ABC transporter MRP6 (ABCC6) Biochemistry. 2002;41:8058–8067. doi: 10.1021/bi012082p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DL, Satin LS, Ashford MLJ, Hales CN. ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pancreatic β-cells – Sparechannel hypothesis. Diabetes. 1988;37:495–498. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'hahan N, Jacquet H, Moreau C, Catty P, Vivaudou M. A transmembrane domain of the sulfonylurea receptor mediates activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels by K+ channel openers. Mol Pharmacol. 1999a;56:308–315. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'hahan N, Moreau C, Prost AL, Jacquet H, Alekseev AE, Terzic A, et al. Pharmacological plasticity of cardiac ATP-sensitive potassium channels toward diazoxide revealed by ADP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999b;96:12162–12167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson G, Steiner D. The role of assembly in insulin's biosynthesis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer R, Soria B, Dawson CM, Atwater I, Rojas E. Effects of Zn2+ on glucose-induced electrical activity and insulin release from mouse pancreatic islets. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:C520–527. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.246.5.C520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forestier C, Pierrard J, Vivaudou M. Mechanism of action of K channel openers on skeletal muscle K–ATP channels – Interactions with nucleotides and protons. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:489–502. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson CJ, Bush AI. Synaptically released zinc: physiological functions and pathological effects. Biometals. 2001;14:353–366. doi: 10.1023/a:1012934207456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaither LA, Eide DJ. Eukaryotic zinc transporters and their regulation. Biometals. 2001;14:251–270. doi: 10.1023/a:1012988914300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafghazi T, McDaniel ML, Lacy PE. Zinc-induced inhibition of insulin secretion from isolated rat islets of Langerhans. Diabetes. 1981;30:341–345. doi: 10.2337/diab.30.4.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble FM, Tucker SJ, Haug T, Ashcroft FM. MgATP activates the beta cell K–ATP channel by interaction with its SUR1 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7185–7190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantke K. Bacterial zinc transporters and regulators. Biometals. 2001;14:239–249. doi: 10.1023/a:1012984713391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison NL, Gibbons SJ. Zn2+: an endogenous modulator of ligand- and voltage-gated ion channels. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:935–952. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershfinkel M, Moran A, Grossman N, Sekler I. A zinc-sensing receptor triggers the release of intracellular Ca2+ and regulates ion transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11749–11754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201193398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang EP. Metal ions and synaptic transmission: think zinc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13386–13387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara H, Maechler P, Gjinovci A, Herrera PL, Wollheim CB. Islet beta-cell secretion determines glucagon release from neighbouring a-cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:330–335. doi: 10.1038/ncb951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia YS, Jeng JM, Sensi SL, Weiss JH. Zn2+ currents are mediated by calcium-permeable AMPA/kainate channels in cultured murine hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 2002;543:35–48. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakei M. Receptor-operated regulation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels via membrane phospholipid metabolism. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:235–243. doi: 10.2174/0929867033368475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Canzoniero LM, Yu SP, Ling C, Choi DW. Zn2+ current is mediated by voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and enhanced by extracellular acidity in mouse cortical neurones. J Physiol. 2000;528:39–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BJ, Kim YH, Kim S, Kim JW, Koh JY, Oh SH, et al. Zinc as a paracrine effector in pancreatic islet cell death. Diabetes. 2000;49:367–372. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok WM, Kass RS. Block of cardiac ATP-sensitive K+ channels by external divalent cations is modulated by intracellular ATP – evidence for allosteric regulation of the channel protein. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:693–712. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.4.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Hough CJ, Suh SW, Sarvey JM, Frederickson CJ. Rapid translocation of Zn2+ from presynaptic terminals into postsynaptic hippocampal neurons after physiological stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2597–2604. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZS, Lu YP, Zhen RG, Szczypka M, Thiele DJ, Rea PA. A new pathway for vacuolar cadmium sequestration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: YCF1-catalyzed transport of bis (glutathionato) cadmium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:42–47. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light P. Regulation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels by phosphorylation. BBA-Rev Biomembranes. 1996;1286:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(96)00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light PE, Bladen C, Winkfein RJ, Walsh MP, French RJ. Molecular basis of protein kinase C-induced activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9058–9063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160068997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman ER, Tytgat J, Hess P. Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DD, Cohen AS, Coulter DA. Zinc-induced augmentation of excitatory synaptic currents and glutamate receptor responses in hippocampal CA3 neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1185–1196. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. Crosstalk of the group IIa and IIb metals calcium and zinc in cellular signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12325–12327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231481398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miledi R, Parker I, Woodward RM. Membrane currents elicited by divalent cations in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1989;417:173–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteilh-Zoller MK, Hermosura MC, Nadler MJS, Scharenberg AM, Penner R, Fleig A. TRPM7 provides an ion channel mechanism for cellular entry of trace metal ions. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:49–60. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau C, Jacquet H, Prost AL, D'Hahan N, Vivaudou M. The molecular basis of the specificity of action of K-ATP channel openers. EMBO J. 2000;19:6644–6651. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino D, Giovannelli A, Degasperi V, Eusebi F, Grassi F. Zinc permeates mouse muscle ACh receptor channels expressed in BOSC 23 cells and affects channel function. J Physiol. 2000;529:83–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino S, Miki T. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;81:133–176. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(02)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensi SL, Canzoniero LMYuSP, Ying HS, Koh JY, Kerchner GA, et al. Measurement of intracellular free zinc in living cortical neurons: routes of entry. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9554–9564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline CT, Ying HS, Ling CS, Canzoniero LM, Choi DW. Depolarization-induced 65zinc influx into cultured cortical neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:41–53. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki T, Sunaga Y, Fujimoto K, Kashima Y, Seino S. Interaction of ATP sensor, cAMP sensor, Ca2+ sensor, and voltage-dependent calcium channel in insulin granule exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;279:7956–7961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart TG, Xie X, Krishek BJ. Modulation of inhibitory and excitatory amino acid receptor ion channels by zinc. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42:393–341. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standen NB. Cardioprotection by preconditioning: K-ATP channels, metabolism, or both? J Physiol. 2002;542:666. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.025601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata T, Ishida AT. A zinc-dependent Cl− current in neuronal somata. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5195–5204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05195.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzic A, Vivaudou M. Molecular pharmacology of ATP-sensitive K+ channels: how and why? In: Archer SL, Rusch NJ, editors. Potassium Channels in Cardiovascular Biology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Tommasini R, Evers R, Vogt E, Mornet C, Zaman GJ, Schinkel AH, et al. The human multidrug resistance-associated protein functionally complements the yeast cadmium resistance factor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6743–6748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft FM. Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387:179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallee BL, Falchuk KH. The biochemical basis of zinc physiology. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:79–118. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivaudou MB, Arnoult C, Villaz M. Skeletal muscle ATP-sensitive potassium channels recorded from sarcolemmal blebs of split fibers: ATP inhibition is reduced by magnesium and ADP. J Membr Biol. 1991;122:165–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01872639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivaudou M, Forestier C. Modification by protons of frog skeletal muscle KATP channels: effects on ion conduction and nucleotide inhibition. J Physiol. 1995;486:629–645. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wei QQ, Cheng XY, Chen KY, Zhu PH. Inhibition of ryanodine binding to sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles of cardiac muscle by Zn2+ ions. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2001;11:83–92. doi: 10.1159/000047795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JH, Sensi SL, Koh JY. Zn2+: a novel ionic mediator of neural injury in brain disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:395–401. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LH, Horie M, Takano M. Phospholipase C-linked receptors regulate the ATP-sensitive potassium channel by means of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15292–15297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Schwappach B, Jan YN, Jan LY. A new ER trafficking signal regulates the subunit stoichiometry of plasma membrane K-ATP channels. Neuron. 1999;22:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]