Abstract

A variety of stimuli, such as abscisic acid (ABA), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and elicitors of plant defense reactions, have been shown to induce stomatal closure. Our study addresses commonalities in the signaling pathways that these stimuli trigger. A recent report showed that both ABA and ROS stimulate an NADPH-dependent, hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+ influx current in Arabidopsis guard cells termed “ICa” (Z.M. Pei, Y. Murata, G. Benning, S. Thomine, B. Klüsener, G.J. Allen, E. Grill, J.I. Schroeder, Nature [2002] 406: 731–734). We found that yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) elicitor and chitosan, both elicitors of plant defense responses, also activate this current and activation requires cytosolic NAD(P)H. These elicitors also induced elevations in the concentration of free cytosolic calcium ([Ca2+]cyt) and stomatal closure in guard cells. ABA and ROS elicited [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in guard cells only when extracellular Ca2+ was present. In a 5 mm KCl extracellular buffer, 45% of guard cells exhibited spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations that differed in their kinetic properties from ABA-induced Ca2+ increases. These spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations also required the availability of extracellular Ca2+ and depended on the extracellular potassium concentration. Interestingly, when ABA was applied to spontaneously oscillating cells, ABA caused cessation of [Ca2+]cyt elevations in 62 of 101 cells, revealing a new mode of ABA signaling. These data show that fungal elicitors activate a shared branch with ABA in the stress signal transduction pathway in guard cells that activates plasma membrane ICa channels and support a requirement for extracellular Ca2+ for elicitor and ABA signaling, as well as for cellular [Ca2+]cyt oscillation maintenance.

Calcium acts as an intracellular second messenger, coupling extracellular stimuli to intracellular and whole-plant responses (Hepler and Wayne, 1985; Sanders et al., 1999). Guard cells have been developed as a model system for dissecting early signal transduction processes in plant cells. Guard cells respond to a great variety of external stimuli, including abscisic acid (ABA; McAinsh et al., 1990; Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1990), auxin (Gehring et al., 1990, 1998), ozone (Clayton et al., 1999), and reactive oxygen species (ROS; McAinsh et al., 1996; Pei et al., 2000) with an increase in the cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) and subsequent stomatal movements (for review, see Blatt, 2000; Schroeder et al., 2001a). Cytosolic Ca2+ increases down-regulate inward-rectifying K+ channels and activate anion channels, providing mechanisms for Ca2+-dependent stomatal closure (Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1989). Particularly well analyzed is the Ca2+ response of guard cells to the phytohormone ABA (McAinsh et al., 1990; Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1990; Blatt and Armstrong, 1993; Schmidt et al., 1995; Leckie et al., 1998; Allen et al., 1999a; Staxén et al., 1999; MacRobbie, 2000; Hugouvieux et al., 2001; for review, see Blatt, 2000; Schroeder et al., 2001b).

ABA has been shown to activate a hyperpolarization-dependent Ca2+-permeable current in the plasma membrane of guard cells, leading to Ca2+ influx and an increase in the cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration (Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that ABA elevates levels of ROS, and that elevated ROS levels stimulate Ca2+-permeable cation currents in the plasma membrane termed “ICa” (Pei et al., 2000). ICa channels have been shown to be permeable to several cations including Mg2+ (Pei et al., 2000). The ABA-insensitive mutants gca2, abi1-1, and abi2-1 disrupt ICa channel activation at distinct points, providing genetic evidence for this newly recognized branch in ABA signaling (Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001).

ROS production in guard cells is induced not only by ABA, but also by the elicitors of plant defense reactions chitosan and oligo-GalUA (Lee et al., 1999). These elicitors also promote stomatal closing (Lee et al., 1999). In plant cells other than guard cells, it is known that one of the first responses to elicitors is an elevation in cytosolic Ca2+, which lies upstream of NADPH-oxidase activation (Knight et al., 1991; Zimmermann et al., 1997; Mithöfer et al., 1999; Blume et al., 2000). Pathogen-induced Ca2+ influx has been reported to occur both before (Schwacke and Hager, 1992; Blume et al., 2000) and after (Price et al., 1994; Kawano and Muto, 2000) ROS production, indicating that two distinct plasma membrane Ca2+ channels may function during different phases of the response. The similarities between the elicitor-activated and hyperpolarization-induced Ca2+ channels in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) cells (Gelli et al., 1997) and ABA-activated Ca2+ channels in guard cells (Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000) suggest that these two stimuli may activate related influx currents.

Ca2+ oscillations have been shown to be critical for induction of stomatal closure (Allen et al., 2000), and are mediated from two general sources, proposed to work in parallel: influx of Ca2+ across the plasma membrane (Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1990; Hamilton et al., 2000; MacRobbie, 2000; Pei et al., 2000) and release of Ca2+ from internal stores (Leckie et al., 1998; Staxén et al., 1999; MacRobbie, 2000). The concentration of ABA favors either induction of Ca2+ influx or Ca2+ release mechanisms in Commelina communis guard cells (MacRobbie, 2000). At high ABA concentrations (> 1 μm), Ca2+ influx was reported to predominantly contribute to ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt increases, whereas at low ABA, Ca2+ release from internal stores is predominant in Commelina communis. To understand Ca2+-based signal transduction pathways in guard cells, therefore, it is necessary to closely analyze the conditions under which Ca2+ influx or Ca2+ release mechanisms occur. Manganese quenching experiments show that external Ca2+-induced oscillations in cytosolic Ca2+ include plasma membrane Ca2+ influx (McAinsh et al., 1995). Although extracellular Ca2+ is required for ABA-induced changes in stomatal aperture (De Silva et al., 1985; Schwartz, 1985; MacRobbie, 2000; Webb et al., 2001), and for ABA induction of a transient [Ca2+]cyt increase in Vicia faba guard cells (Romano et al., 2000), to date, ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in Arabidopsis guard cells have not been analyzed as a function of extracellular Ca2+ removal. Here, we have analyzed whether intracellular Ca2+ release pathways that contribute to Ca2+ oscillations are dependent on rapid extracellular Ca2+ removal.

In the present study, we analyze the degree of convergence of stomatal closure pathways induced by different stimuli. We test whether ICa Ca2+ channels represent a shared branch of ABA and elicitor signaling by testing whether elicitors activate hyperpolarization-induced ICa Ca2+ influx currents. We investigated further the effects of external Ca2+ and external [K+] on [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in multiple stomatal closure signaling pathways. We also reveal a new mode of ABA signaling in which ABA is shown to down-regulate spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations that occur in guard cells (Allen et al., 1999b; Staxén et al., 1999).

RESULTS

Elicitors Activate NADPH-Dependent Ca2+ Channel Currents

It has been shown that chitosan, an elicitor of phytoalexin production in pea (Pisum sativum) pods (Hadwiger and Beckman, 1980), induces the production of ROS and a reduction of stomatal aperture in guard cells of tomato and C. communis (Lee et al., 1999). We analyzed whether chitosan and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) elicitor, a well-studied elicitor of defense reactions in cell cultures of Eschcholtzia californica (Schumacher et al., 1987), could activate plasma membrane Ca2+ currents in guard cells similar to the ROS-induced Ca2+ currents during ABA signaling. We applied voltage ramps from −18 to −198 mV (after correction for liquid junction potentials). Both chitosan and yeast elicitor activated a hyperpolarization-dependent current in guard cell protoplasts (Fig. 1). In the absence of elicitors, only a small background current with a mean amplitude of −5.7 pA (n = 17 protoplasts) at −198 mV was observed. Upon addition of 10 μg mL−1 yeast elicitor to the bath solution, a hyperpolarization-activated inward current was observed. This current had a mean peak current amplitude of −59.9 pA at −198 mV (n = 10 protoplasts). Chitosan (10 μg mL−1) induced a hyperpolarization-activated current with a mean peak amplitude of −119.6 pA (n = 8 protoplasts). Average current/voltage relationships from untreated and elicitor treated cells are shown in Figure 1B. ROS- and ABA-activated ICa currents have been shown previously to have a “spiky” behavior (Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001), which was also observed for elicitor-activated currents (Fig. 1A) that are activated by hyperpolarization. Figure 1C shows currents produced by a voltage pulse protocol in the presence of H2O2 (n = 4). Note that ICa currents were not observed in voltage pulse protocols in the absence of H2O2 (Fig. 1C, −H2O2; n = 4).

Figure 1.

Elicitor activation of hyperpolarization-dependent currents in Arabidopsis guard cells. A, Whole-cell currents without or with 10 μg mL−1 yeast elicitor or chitosan present in the bath solution. Elicitor-activated currents were measured approximately 5 min after elicitor exposure. Voltage ramps (1-s duration) were from −18 to −198 mV (lower). The liquid junction potential of −18 mV was corrected for. Arrows on the right show zero current levels. Bath solution: 100 mm BaCl2, 0.1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), and 10 mm MES-Tris (pH 5.6). Pipette solution: 10 mm BaCl2, 0.1 mm DTT, 4 mm EGTA, 5 mm NADPH, and 10 mm HEPES-Tris (pH 7.1). B, Current/voltage relationship from control and elicitor-treated cells. Experimental conditions are the same as in A. Black circles, Untreated cells (n = 17); white circles, yeast elicitor-treated cells (n = 10); white squares, chitosan-treated cells (n = 8). C, Currents produced by voltage pulses (top) in the absence (middle) or presence (bottom) of 5 mm hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The liquid junction potential of −18 mV was corrected for.

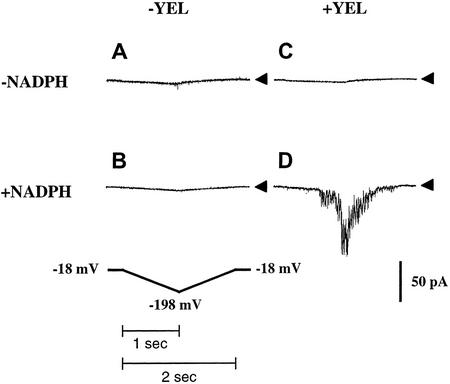

Interestingly, addition of NADPH to the pipette solution was necessary to activate elicitor- and hyperpolarization-dependent currents. Without NADPH present in the pipette solution, yeast elicitor could not induce hyperpolarization-activated currents (Fig. 2, A and C; n = 7). With NADPH in the pipette, yeast elicitor activated the hyperpolarization-activated current (Fig. 2, B and D; n = 10).

Figure 2.

NADPH dependence of elicitor-induced hyperpolarization-activated currents. A, Pipette solution, no NADPH; bath solution, no yeast elicitor (n = 4). B, Pipette solution, 5 mm NADPH; bath solution, no yeast elicitor (n = 17). C, Pipette solution, no NADPH; bath solution, 10 μg mL−1 yeast elicitor (n = 7). D, Pipette solution, 5 mm NADPH; bath solution, 10 μg mL−1 yeast elicitor (n = 10). In all experiments, 10 mm BaCl2 (+0.1 mm DTT, 4 mm EGTA, and 10 mm HEPES-Tris [pH 7.1]) were used as pipette solution and 100 mm BaCl2 (+0.1 mm DTT and 10 mm MES-Tris [pH 5.6]) as bath solution. The applied voltage ramp protocol is shown in the lower left. The liquid junction potential of −18 mV was corrected for. Arrows on the right show zero current levels.

Elicitor-Induced [Ca2+]cyt Elevations Require External Ca2+

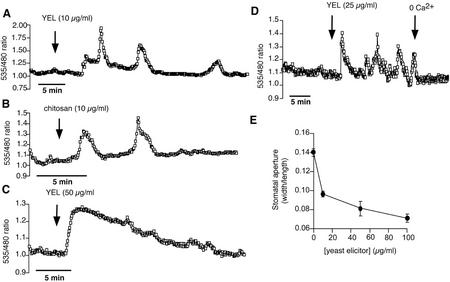

Both chitosan and yeast elicitor induced repetitive [Ca2+]cyt elevations in guard cells of Arabidopsis (Fig. 3, A and B). Elicitor concentrations as low as 10 μg mL−1 were sufficient to induce repetitive [Ca2+]cyt transients in guard cells treated with yeast elicitor (n = 12 of 15 cells) or chitosan (n = 9 of 9 cells). The relative amplitude and mean duration of yeast elicitor and chitosan-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients are summarized in Table I. When yeast elicitor was applied at higher concentrations (50 μg mL−1), only a single, slowly declining [Ca2+]cyt transient with a relative amplitude of Δratio585/480 = 0.41 ± 0.04 and a mean duration of 22.28 ± 2.67 min (duration at one-half amplitude of 10.9 ± 1.42 min) was observed (Fig. 3C; n = 14 cells).

Figure 3.

Elicitor-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients and stomatal closing. A, Repetitive [Ca2+]cyt transients induced by 10 μg mL−1 yeast elicitor. B, Repetitive [Ca2+]cyt transients induced by 10 μg mL−1 chitosan. C, Example of a [Ca2+]cyt transient, induced by 50 μg mL−1 yeast elicitor. Note that under the imposed conditions, only a single [Ca2+]cyt transient with a slow decay time was observed. D, Yeast elicitor-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients require external Ca2+. Epidermal peels were incubated in the standard bath solution (5 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES-Tris [pH 6.15]). At the indicated time point (first arrow), the bath was perfused with a solution containing 25 μg mL−1 yeast elicitor (5 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, 25 μg mL−1 yeast elicitor, and 10 mm MES-Tris [pH 6.15]). At the second time point (second arrow), the bath solution was exchanged with a Ca2+-free solution (5 mm KCl, 250 μm EGTA, and 10 mm MES-Tris [pH 6.15]). Immediately after the perfusion with zero Ca2+ started, the yeast elicitor-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients ceased. E, Yeast elicitor reduces stomatal aperture. Each data point represents the mean stomatal aperture of 100 analyzed stomata from n = 4 replicates. Error bars = sd. Stomatal aperture was measured 2 h after elicitor application.

Table I.

Elicitor-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients in guard cells of Arabidopsis

| Elicitor (10 mg mL−1) | Relative Amplitude | Transient Duration | Period | No. of Transients | Cells with Transients | Total No. of Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δratio535/480 | Δt/min | min | % | |||

| Yeast elicitor | 0.45 ± 0.10 | 2.83 ± 0.76 | 5.74 ± 1.52 | 2.58 ± 0.33 | 80 | 15 |

| Chitosan | 0.66 ± 0.28 | 2.97 ± 0.32 | 5.26 ± 0.834 | 2.44 ± 0.47 | 100 | 9 |

Data were obtained during the first 30 min after elicitor application. Errors represent se.

Yeast elicitor-induced transient increases in [Ca2+]cyt required the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 3D). Elicitor-induced cytoplasmic [Ca2+]cyt transients immediately ceased after the bath solution was perfused with a Ca2+-free bath solution (5 mm KCl, 250 μm EGTA, and 10 mm MES/Tris [pH 6.15]; n = 12 cells). Although long-term external Ca2+ removal treatment may deplete intracellular calcium stores, it appears unlikely that this depletion is rapid enough to account for the immediate cessation of Ca2+ oscillations upon external Ca2+ removal. Note also that store-operated calcium currents, which are activated by a depletion of intracellular calcium stores, are not activated by extracellular application of EGTA alone (Kwan et al., 1990; Patterson et al., 1999). Therefore, the cessation of yeast elicitor-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations by external EGTA (Fig. 3D), together with elicitor-induced ICa activation (Figs. 1 and 2), demonstrate a requirement of Ca2+ influx for this response. We also tested whether yeast elicitor has an effect on stomatal movements in Arabidopsis and found a concentration-dependent reduction of stomatal aperture using the same concentrations that elicited [Ca2+]cyt transients (Fig. 3E).

ABA-Regulated [Ca2+]cyt Elevations

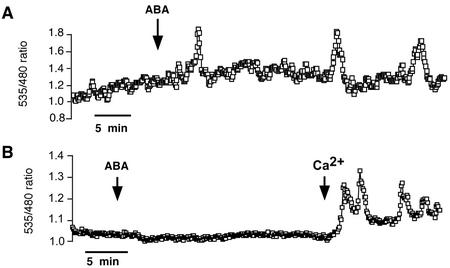

Having shown a requirement of extracellular calcium for elicitor-induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillations, we next tested whether ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillations share this requirement. As previously shown, ABA (10 μm) induces repetitive [Ca2+]cyt elevations in cells (n = 18 of 40 cells) incubated in a bath solution containing calcium and 10 mm KCl (Fig. 4A). However, when extracellular Ca2+ was buffered to sub-micromolar concentrations by adding 250 μm EGTA (n = 12) or 250 μm BAPTA (n = 31) 10 min before ABA treatment, ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations could not be observed (Fig. 4B). Re-addition of extracellular Ca2+ at the end of the experiments led to external Ca2+-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations, showing that these cells were competent to report [Ca2+]cyt elevations (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in Arabidopsis guard cells require extracellular Ca2+. A, Repetitive [Ca2+]cyt transients induced by 10 μm ABA. Extracellular solution: 5 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES/Tris (pH 6.15). B, Guard cells that were incubated in Ca2+-free solutions show no response to 10 μm ABA. Addition of 10 mm external Ca2+ at end of experiment caused [Ca2+]cyt increases.

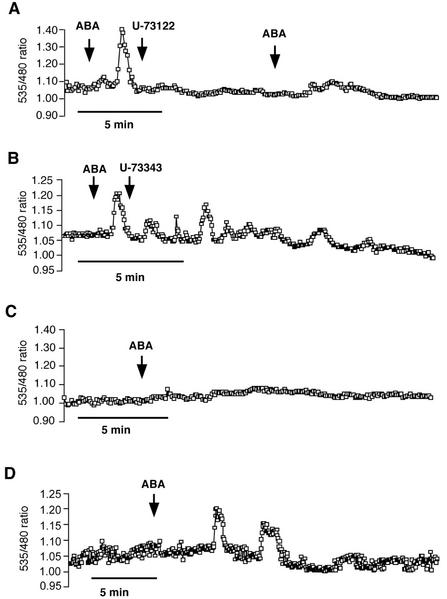

With evidence that external calcium is required for ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in guard cells, we next examined the role of intracellular Ca2+ release pathways during ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillations. We first tested the pharmacological phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor U-73122 and its physiologically inactive analog U-73343 (Staxén et al., 1999) in Arabidopsis guard cells. Ten micromolar ABA was added to the solution bathing epidermal peels. Immediately after ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients became visible, the cells were perfused either with 1 μm U-73122 or 1 μm U-73343. In the case of U-73122, a partial inhibition of ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients was observed (Fig. 5A; n = 6 cells). Perfusion of guard cells with the inactive analog U-73343 (1 μm) did not inhibit ABA-induced transients (Fig. 5B; n = 10 cells). In further experiments, epidermal peels were pre-incubated 30 min in 1 μm U-73122 or U-73343 before ABA (10 μm) was added to the bath solution. In the pre-incubation experiments with U-73122, no ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt increases were elicited (Fig. 5C; n = 6 cells). Guard cells that were pre-incubated with U-73343 still responded to ABA (Fig. 5D; n = 15 cells).

Figure 5.

The PLC inhibitor U-73122 has a negative effect on ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillations. A, Perfusion with 1 μm U-73122 partially inhibited ABA (10 μm) induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations in guard cells. Sequence of ABA and U-73122 perfusion: time point 1 (first arrow), 10 μm ABA (+standard bath solution); time point 2 (second arrow), 1 μm U-73122 (+standard bath solution and 10 μm ABA); and time point 3 (third arrow), 10 μm ABA (+standard bath solution, without U-73122). B, Perfusion with 1 μm U-73343, an inactive analog of U-73122, has no effect on ABA-induced Ca2+ transients. C, After a 30-min pre-incubation of guard cells in 1 μm U-73122, ABA (10 μm) did not activate [Ca2+]cyt transients in Arabidopsis guard cells. D, Thirty-min pre-incubation of guard cells in 1 μm U-73343 did not inhibit ABA (10 μm)-induced Ca2+ transients in guard cells.

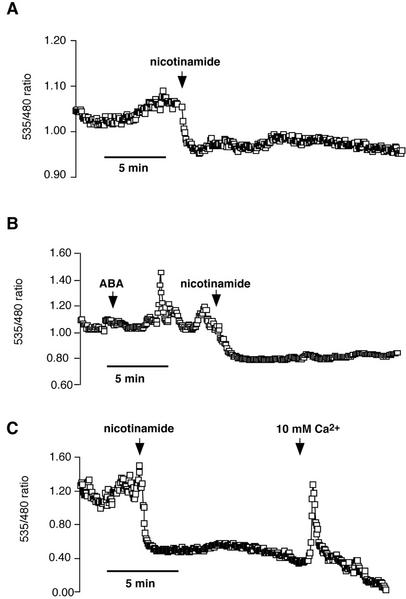

Studies have suggested that cADP Rib (cADPR) is a Ca2+-releasing second messenger in ABA signal transduction (Allen et al., 1995; Wu et al., 1997; Leckie et al., 1998). Therefore, we analyzed the effects of nicotinamide on cameleon-expressing guard cells. Nicotinamide blocks cADPR synthesis and has been used to analyze putative roles of cADPR in guard cells and tomato subepidermal cells (Wu et al., 1997; Leckie et al., 1998; Jacob et al., 1999; MacRobbie, 2000). Interestingly, nicotinamide consistently caused a rapid reduction in the cameleon fluorescence ratio of guard cells (Fig. 6; n = 44 of 50 cells), suggesting that nicotinamide has a relatively drastic effect on [Ca2+]cyt in Arabidopsis guard cells. Levels of basal [Ca2+]cyt dropped upon nicotinamide application in both cells that were not treated with ABA (Fig. 6A; n = 36) and ABA-treated cells (Fig. 6B; n = 8). ABA-induced oscillations were inhibited by nicotinamide. This effect of nicotinamide was not because of any influence of nicotinamide on the cameleon protein because in vitro experiments with recombinant yellow cameleon 2.1 protein showed that nicotinamide did not itself alter the fluorescence of cameleon, nor did it alter cameleon fluorescence ratio changes induced by calcium (data not shown). Nicotinamide-treated cells were still able to respond to 10 mm external Ca2+ with an increase in [Ca2+]cyt, indicating that these cells were still responsive to external stimuli (Fig. 6C). Our studies with PLC and cADPR inhibitors show that blocking these two calcium release pathways leads to distinct alterations in calcium homeostasis and signaling.

Figure 6.

Nicotinamide causes a drop in [Ca2+]cyt in Arabidopsis guard cells. A, Fifty millimolar nicotinamide reduced the baseline [Ca2+]cyt level in untreated guard cells. B, Nicotinamide reduced the baseline [Ca2+]cyt level and inhibited ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt increases. C, Nicotinamide (50 mm)-treated cells are still responsive to the addition of 10 mm external calcium (n = 7 of 10 cells).

ROS-Induced [Ca2+]cyt Elevations

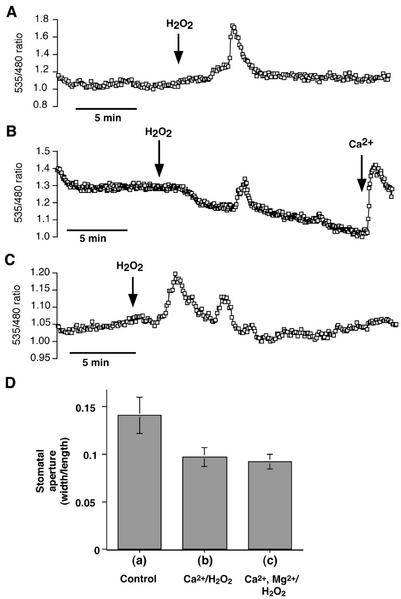

Recent work suggests that ROS participate in the induction of [Ca2+]cyt elevations by ABA in Arabidopsis guard cells, and ROS have been shown to trigger [Ca2+]cyt elevations. To further investigate whether the [Ca2+]cyt elevations induced by these two stimuli are part of a shared pathway, we investigated whether ROS-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations are more prevalent at hyperpolarized membrane potentials, as has been shown previously for ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations (Grabov and Blatt, 1998). We tested this by recording ROS-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations in bath solutions with different concentrations of K+. A lower extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]ext) leads to a more hyperpolarized membrane (Saftner and Raschke, 1981; Clint and Blatt, 1989; Grabov and Blatt, 1998). In 5 mm KCl, extracellular application of 100 μm H2O2 induced a [Ca2+]cyt transient in all 12 cells tested (Fig. 7A), either consisting of one (n = 9 of 12 cells) or two (n = 3 of 12 cells) transients. These transients had a mean duration of 3.18 ± 0.31 min, similar to that reported previously (Pei et al., 2000), and a mean relative peak [Ca2+]cyt increase of Δratio535/480 (=0.49 ± 0.06; n = 12). In solutions containing 100 mm KCl, H2O2 induced [Ca2+]cyt transients in only 12 of 29 (41%) cells (Fig. 7B); in all cases, only a single [Ca2+]cyt transient was observed, and these transients showed smaller [Ca2+]cyt increases (mean Δratio535/480 of 0.18 ± 0.02) than those induced in 5 mm KCl. As reported previously (McAinsh et al., 1996; Pei et al., 2000), guard cells that were incubated in Ca2+-free solutions showed no [Ca2+]cyt elevation in response to H2O2. Thus, ROS-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations and ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations showed enhanced activity at lower external K+ concentrations, and both required external Ca2+ (Fig. 4B).

Figure 7.

H2O2-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations in guard cells of Arabidopsis are dependent on the extracellular K+ concentration and are not blocked by external Mg2+. A, [Ca2+]cyt transient measured in a guard cell in response to 100 μm H2O2. Extracellular solution: 5 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES/Tris (pH 6.15). B, One hundred micromolar H2O2-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations in 12 of 29 cells in high extracellular potassium (100 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES/Tris [pH 6.15]). C, Five hundred micromolar Mg2+ did not block H2O2-induced Ca2+ elevations with 50 μm CaCl2 in the bath. Extracellular solution: 500 μm MgCl2, 50 μm CaCl2, 5 mm KCl, and 10 mm MES/Tris (pH 6.15). D, H2O2-induced stomatal closure is not affected by magnesium. Each data point represents the mean stomatal aperture of 50 analyzed stomata from n = 6 replicates. Error bars show se of mean (relative to n = 6). Stomatal aperture was measured 2 h after application of: (a) 0.2 mm CaCl2 (Control), (b) 0.2 mm CaCl2 and 0.2 mm H2O2, or (c) 0.2 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, and 0.2 mm H2O2. In all experiments, 0.1 mm EGTA was added to the bath solution to buffer external [Ca2+] close to 0.1 mm (Pei et al., 2000). H2O2 did not induce stomatal closure in the absence of this buffering, perhaps because external Ca2+, including locally released cell wall Ca2+, was too high, which can in itself cause partial stomatal closing (McAinsh et al., 1995; Allen et al., 1999a).

Previous experiments showed that ROS-activated ICa channels in guard cells are nonselective cation channels with a permeability to Mg2+, suggesting that Mg2+ might compete with Ca2+ for passage through the channel (Pei et al., 2000). To test whether external Mg2+ can compete with Ca2+ signaling, we monitored ROS-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients in the presence of an extracellular Mg2+ concentration (500 μm) 10-fold higher than that of Ca2+ (50 μm). These conditions had no influence on the induction of [Ca2+]cyt transients by H2O2 (Fig. 7C; n = 13 cells). We also performed stomatal closing assays to analyze whether H2O2-induced stomatal closure is affected by magnesium. Replacement of 0.2 mm CaCl2 in the bath solution by 2 mm MgCl2 + 0.2 mm CaCl2 had no influence on H2O2-induced stomatal closure (Fig. 7D). Exposing guard cells to 10 mm MgCl2 did not cause [Ca2+]cyt oscillations (n = 4, data not shown), in contrast to the external Ca2+ response (Fig. 4B). These data show that external Mg2+ cannot replace Ca2+ in inducing Ca2+ oscillations. Similarly, in the absence of external Ca2+, shifts in the extracellular KCl concentration from 0.1 to 100 mm caused no changes in cameleon fluorescence ratios (Allen et al., 2001; http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v411/n6841/extref/4111053aa.html). These data support the premise that oscillations in cameleon ratios were not because of oscillations in cytosolic Cl− concentrations.

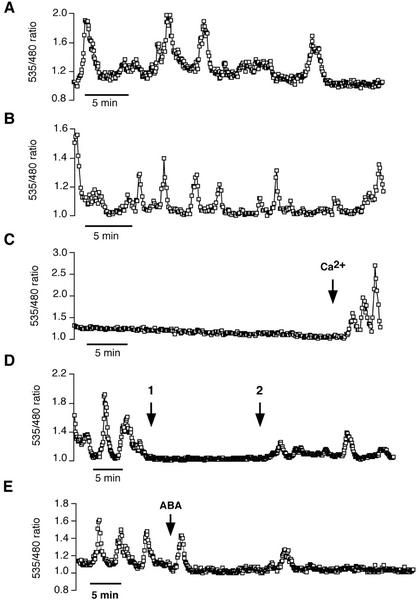

Spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt Oscillations Require External Calcium

There is now quite compelling evidence that [Ca2+]cyt elevations are an important component of guard cell signal transduction for multiple stimuli, such as ABA, external Ca2+, and ROS. Interestingly, guard cells also frequently show spontaneously arising [Ca2+]cyt oscillations, i.e. oscillations that are not induced by the extracellular application of such stimuli (Fig. 8; Allen et al., 1999b, 2001; Staxén et al., 1999). We examined whether these spontaneous oscillations share properties with induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillations by testing their dependence on extracellular K+ and external Ca2+. As occurred with ABA- and ROS-induced oscillations, lower extracellular potassium concentrations led to increases in the occurrence of spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations (Table II). Guard cells that were incubated in 5 mm KCl showed spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients in approximately 45% of the 33 cells analyzed in this study. Note that the percentage of cells showing spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations varies in different preparations, but they are commonly observed in guard cells (Grabov and Blatt, 1998; Allen et al., 1999b; Staxén et al., 1999). Cells that showed spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients (n = 15 of 33 cells) exhibited an average of 2.07 ± 0.29 transients in 5 mm KCl (30-min recording interval; Table II; Fig. 8A). In 0.1 mm KCl, the percentage of guard cells exhibiting spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients was increased to 88% (n = 42 of 48 cells), and the average number of transients per cell was increased to 3.71 ± 0.25 (Table II; Fig. 8B). Spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillation periods were shorter than those reported for ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillation periods (Table II; Allen et al., 2001). In solutions containing 100 mm KCl, spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations were not observed (Fig. 8C). Interestingly, however, these same cells still produced transient [Ca2+]cyt elevations when exposed to high extracellular Ca2+ (10 mm; Fig. 8C).

Figure 8.

Spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in guard cells of Arabidopsis are dependent on the Ca2+ and K+ concentration in the bath solution. A, Spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in a 5 mm KCl-solution (+50 μm CaCl2 and 10 mm MES/Tris [pH 6.15]). B, The frequency of spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients is increased in solutions containing low K+ concentrations (0.1 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES/Tris [pH 6.15]; see also Table II). C, Guard cells showed no spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients in high potassium solutions (100 mm KCl and 50 μm CaCl2). Note that 10 mm external Ca2+ triggered Ca2+ transients in guard cells, incubated in the same high-potassium solutions. D, Perfusion with a Ca2+-free solution (perfusion start at time point 1) inhibited spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients. When cells were reperfused with a 50 μm Ca2+-containing standard bath solution (time point 2), a recovery of spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients was observed (n = 19 cells). E, Spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations were suppressed in 62 of 101 of guard cells (61%) by the application of 5 μm ABA. ABA was applied at the time indicated by the arrow.

Table II.

Spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients in guard cells of Arabidopsis

| [KCl] | Relative Peak [Ca2+]cyt Increase | Transient Duration | Period | No. of Transients | Cells with Transients | Total no. of Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | Δratio535/480 | Δt/min | min | % | ||

| 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 1.47 ± 0.13 | 5.91 ± 0.71 | 3.71 ± 0.25 | 88 | 48 |

| 5 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 2.68 ± 0.32 | 6.75 ± 1.43 | 2.07 ± 0.29 | 45 | 33 |

| 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

Summarized is the dependence of spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients on the external K+ concentration. Data were obtained during the first 30 min of each experiment. Errors represent se.

Upon removal of extracellular Ca2+, as with ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt oscillations, spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations rapidly ceased to occur (Fig. 8D; n = 19 cells). A guard cell displaying spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt transients under continuous perfusion with the standard bath solution (containing 5 mm KCl) was perfused with an EGTA-containing solution at time point 1. The [Ca2+]cyt oscillations immediately ceased after the perfusion with zero Ca2+ (Fig. 8D). At time point 2, the cell was perfused again with the standard bath solution containing 50 μm CaCl2, which induced a rapid recovery of [Ca2+]cyt oscillations.

In Ca2+ imaging experiments to date, ABA was added to cells that showed no spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations (e.g. McAinsh et al., 1990; Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1990; Gilroy et al., 1991; Allan et al., 1994; Staxén et al., 1999; Allen et al., 1999b; 2001). Here, we analyzed the effect of ABA on spontaneously oscillating guard cells. The spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation period (Table II) was shorter than that of ABA-induced Ca2+ oscillations (Allen et al., 2001). Interestingly, in cells that were showing spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations at the beginning of the experiment, ABA, in a substantial number of experiments, led to a rapid cessation of [Ca2+]cyt oscillation activity. Complete spontaneous oscillation suppression occurred within 10 to 15 min after ABA application via the continuous perfusion stream and occurred in n = 62 of 101 spontaneously oscillating cells treated with ABA (61%; Fig. 8E). In the remaining cells, ABA did not cause cessation of spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations. In a few of the cells (n = 14) where ABA suppressed spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations, oscillations reactivated after a 30- to 40-min quiescent period. The ability of ABA to abolish spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations is a novel finding and may be associated with a retuning of signal transduction components for ABA signaling and/or ABA-induced depolarization.

DISCUSSION

Elicitor-Induced [Ca2+]cyt Oscillations

In tomato (Gelli et al., 1997) and parsley (Petroselinum crispum; Zimmermann et al., 1997), two distinct types of plant defense elicitor-activated Ca2+ influx currents have been described. The elicitor-induced currents in tomato cells activate at hyperpolarizing membrane potentials similar to those found here (Gelli et al., 1997), and show similarities to the ABA, ROS, and hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+ currents (ICa) of Arabidopsis guard cells (Pei et al., 2000), whereas in parsley cells, elicitors activate very large conductance channels (>250 pS) at more depolarized potentials (Zimmermann et al., 1997). We attempted to establish whether ICa can be activated by elicitors in Arabidopsis guard cells. We used two different elicitors of plant defense reactions in our studies. Chitosan, which has been shown previously to cause the production of ROS and stomatal closing in tomato and C. communis guard cells (Lee et al., 1999) and yeast elicitor, an elicitor with broad activity (induction of benzophenanthridine alkaloids, generation of ROS, and induction of intracellular pH shifts) in many diverse plant species (Blechert et al., 1995; Roos et al., 1998). We demonstrate that both chitosan and yeast elicitor activate a hyperpolarization-dependent current in guard cells, which resembles ICa in its voltage dependence. Furthermore, cytosolic NAD(P)H was necessary to activate this current (Fig. 2), which correlates with recent findings of the NAD(P)H requirement for ABA activation of ICa (Murata et al., 2001). Therefore, the chitosan- and yeast elicitor-induced production of ROS in guard cells (Lee et al., 1999) may occur via modulation of NAD(P)H-dependent mechanisms, as has been demonstrated in plant defense responses (Keller et al., 1998). Thus, the ROS produced could activate ICa, leading to the observed elicitor-induced increases in [Ca2+]cyt.

The presented findings support the previously proposed model that ROS activation of ICa channels is part of a shared branch or “cassette” of stress signaling pathways (Pei et al., 2000; Schroeder et al., 2001b) and suggests that NAD(P) H-dependent activation of ICa channels represents a cross talk mechanism between ABA and defense signaling. For both elicitor signaling and ABA signaling, the specific reactive oxygen intermediate(s) that mediates signal transduction remains to be determined and could include H2O2, O2−, 1O2, and OH−, among others. In addition, production of the reactive oxygen molecule NO has been shown recently to be induced by ABA in guard cells (Neill et al., 2002). The abi1-1 and abi2-1 protein phosphatase 2Cs (PP2Cs) have been shown to impair ABA signaling in guard cells upstream of ICa activation (Murata et al., 2001). Recent findings show that H2O2 inhibits the PP2C activities of both ABI1 (Meinhard and Grill, 2001) and ABI2 (Meinhard et al., 2002), which in turn could contribute to ICa activation.

Yeast elicitor evoked stomatal closing in guard cells in a concentration-dependent manner. Ca2+ imaging experiments demonstrated that both elicitors induce transient elevations in the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration of guard cells. The elicitor concentrations that induced [Ca2+]cyt transients (10 μg mL−1) were sufficient to trigger stomatal closing responses. Yeast elicitor-induced [Ca2+]cyt increases required the availability of extracellular Ca2+ ions. This indicates that an initial Ca2+ influx is necessary for the observed [Ca2+]cyt increases. This observation is in accordance with studies showing that extracellular Ca2+ is necessary for the induction of plant defense responses against pathogens (Yang et al., 1997; Scheel, 1998; Blume et al., 2000).

Influx and Internal Release of Ca2+ in Guard Cell Signaling

Although other studies have recently addressed the requirement of extracellular Ca2+ for guard cell Ca2+ increases (MacRobbie, 2000; Romano et al., 2000), the contribution of external Ca2+ to long-term [Ca2+]cyt oscillations, which have been shown to be an important part of Ca2+ signaling in guard cells (Allen et al., 2000), has not yet been determined. The abundance of Ca2+ release mechanisms in guard cells could lead to the hypothesis that ABA-induced Ca2+ elevations in Arabidopsis guard cells can occur after external Ca2+ removal. Here, we show that [Ca2+]cyt oscillations do not occur in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. This was shown for oscillations induced by ABA and plant defense elicitors, as well as for spontaneously arising [Ca2+]cyt oscillations. This is consistent with previous work that showed that the earliest increases in [Ca2+]cyt in response to ABA [Ca2+]cyt elevations can occur near the plasma membrane (McAinsh et al., 1992) as well as with a recent tracer flux study showing that extracellular Ca2+ contributes to ABA-induced K+ (Rb+) efflux at >1 μm ABA in C. communis guard cells (MacRobbie, 2000).

Although the presence of external Ca2+ was a prerequisite for the induction of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients under our experimental conditions, these data do not contradict the importance of internal Ca2+ release mechanisms. Experiments in C. communis with U-73122, an inhibitor of plant phospholipase C (Staxén et al., 1999), showed that ABA-induced cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients were suppressed in guard cells that were pre-incubated in 1 μm U-73122. Experiments on Arabidopsis guard cells correlate with these results (Fig. 5, A and C). These findings suggest that inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate triggered Ca2+ release mechanisms may contribute to ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt increases in Arabidopsis. Present simplified models consider parallel functioning of Ca2+ influx and PLC-dependent Ca2+ release mechanisms. Interestingly, however, our results, as well as the requirement of calcium for plant PLC activity (Kopka et al., 1998; Hernández-Sotomayor et al., 1999) suggest that PLC activation and Ca2+ influx may be interdependent. Genetic analyses will be important to test this proposed linkage in activation of Ca2+ influx and PLC-dependent pathways.

Experiments using the cADPR blocker nicotinamide showed a rapid reduction in basal calcium levels in 88% of guard cells (Fig. 6, A–C). Detailed microinjection studies strongly support a role for cADPR in ABA signaling (Wu et al., 1997; Leckie et al., 1998). The results presented here show a difference in the actions of cADPR and PLC inhibitors. The reduction in basal [Ca2+]cyt levels by nicotinamide may contribute to the additive effects of nicotinamide and U-73122 on inhibition of ABA-induced stomatal closing and Rb+ efflux (Jacob et al., 1999; MacRobbie, 2000). The present findings are consistent with models suggesting that cADPR functions parallel to other Ca2+-dependent pathways (Jacob et al., 1999; MacRobbie, 2000). In the present study, nicotinamide also reduced ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations, which correlates with models including cADPR as a second messenger in ABA signaling (Wu et al., 1997; Leckie et al., 1998). It is also possible that nicotinamide reduces overall [Ca2+]cyt levels, thus increasing the threshold required for ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations to proceed. Genetic alteration and inducible silencing of individual mechanisms and Ca2+ imaging will be important for dissecting the underlying differential contributions of Ca2+ release mechanisms to Ca2+ signaling. In addition, the effect of nicotinamide suggests that cADPR may play a role in cytosolic calcium homeostasis.

ABA Inhibition of Spontaneous Oscillations

Surprisingly, we show that ABA causes cessation of spontaneously occurring [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in the majority of guard cells (n = 62 of 101). These data reveal a new, not previously investigated mode of ABA action. A recent study has shown that a “window” of [Ca2+]cyt oscillation parameters encodes steady-state stomatal closing in Arabidopsis (Allen et al., 2001). Interestingly, the periods of spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations found here (6 min; Table II), based on the data of Allen et al. (2001), would correspond to little or no stomatal closure. (Note, however, that we expect that the range of [Ca2+]cyt oscillation parameters that mediate stomatal movements are dynamic and exhibit a dependence on environmental and cellular conditions.) The data presented here indicate that ABA may repress [Ca2+]cyt oscillations not associated with ABA signaling for ABA responses to proceed. ABA-induced depolarization is predicted to cause cessation of spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt elevations (Grabov and Blatt, 1998). This hypothesis is supported by our data indicating that high external K+, which causes depolarization (Grabov and Blatt, 1998), also mitigate ROS-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations (Fig. 8C); thus, depolarization may contribute to the ABA inhibition of spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt elevations revealed here.

Effect of [K+]ext on [Ca2+]cyt Oscillations

We show that the percentage of cells that show either spontaneous or ROS-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations is reduced at elevated extracellular potassium concentrations. Earlier work in V. faba demonstrated that the membrane potential of guard cells exhibits a near-Nernstian dependence on [K+]ext, i.e. the lower the [K+]ext, the more hyperpolarized the plasma membrane (Saftner and Raschke, 1981; Clint and Blatt, 1989). Furthermore, the nonselective nature of an ABA-activated Ca2+ influx current in V. faba guard cells results in reversal potentials that are more negative (e.g. −10 mV) than a Ca2+-selective channel would show (e.g. > +60 mV; Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1990). Consistent with these findings, 50 mm KCl produced a low probability of ABA-induced Ca2+ elevations in previous studies (Gilroy et al., 1991; Allan et al., 1994). Thus, these data suggest that [Ca2+]cyt elevations are favored by hyperpolarized membranes. This is in agreement with other studies in V. faba guard cells that show that [Ca2+]cyt elevations accompany membrane hyperpolarization (Grabov and Blatt, 1998) and low external K+ concentrations (Gilroy et al., 1991; Allen et al., 2000).

Conversely, we found that [Ca2+]cyt elevations induced by high extracellular calcium did not appear affected by [K+]ext (end of trace in Fig. 8C). Previous research has shown that Ca2+ influx mediates the initial phase of [Ca2+]cyt transients induced by external Ca2+ (McAinsh et al., 1995). Even in 100 mm KCl, a large rise in [Ca2+]cyt was always seen immediately after extracellular application of 10 mm CaCl2 (Fig. 8C). This suggests that a hyperpolarization-independent mechanism for generation of [Ca2+]cyt elevations is acting under these conditions or that 10 mm Ca2+ shifts the reversal potential of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels sufficiently positive to allow Ca2+ influx as would be expected for nonselective Ca2+-permeable channels found in V. faba guard cells (Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1990). Note that more than one plasma membrane Ca2+ channel is likely to contribute to cytosolic Ca2+ elevations in guard cells (Hamilton et al., 2000), assuming that the open probability of hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+ channels is not altered by physiological factors and ion gradients.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study demonstrates that elicitors activate plasma membrane ICa channels in an NADPH-dependent manner providing strong evidence for a shared signaling cassette of early ABA and elicitor signaling in guard cells. Furthermore, removal of extracellular Ca2+ causes rapid cessation of elicitor- and ABA-induced as well as spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in guard cells, suggesting an absolute requirement of Ca2+ influx for operation of the guard cell Ca2+ signaling system. Detailed analyses of spontaneous [Ca2+]cyt oscillations in guard cells show that these differ from typical ABA-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations and that ABA can inhibit spontaneous oscillations. In addition, data suggest that Ca2+ influx and phospholipase C are interdependent rather than simply acting in parallel in mediating ABA-induced cytosolic Ca2+ elevations, whereas the pharmacological cADPR inhibitor nicotinamide has a unique effect of lowering baseline cytosolic Ca2+ levels in Arabidopsis guard cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth

Plants of Arabidopsis (ecotype Landsberg erecta) stably expressing yellow cameleon 2.1 under the control of the constitutive 35 S promoter (Allen et al., 1999b) were used in our experiments to measure [Ca2+]cyt levels in guard cells. Arabidopsis seedlings were grown at 20°C in a controlled environment growth chamber (Conviron model E 15, Controlled Environments, Asheville, NC) under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle with a photon fluency rate of 75 μmol m−2 s−1. Pots were watered every 2 to 3 d with deionized water and plants were misted with deionized water daily to keep the humidity close to 70%.

Stomatal Movement Analyses

Stomatal movement analyses were performed as described previously (Pei et al., 1997, Allen et al., 1999a). Rosette leaves from 4- to 6-week-old plants were detached and floated for 2 h in opening solution in the light (photon fluency rate of 75 μmol m−2 s−1). Depending on the type of experiment, we used two different opening solutions. Opening solution I (5 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES-Tris [pH 6.15]) was used to study the effect of elicitors on stomatal aperture, and opening solution II (10 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EGTA, and 10 mm MES-KOH [pH 6.15]) was used to analyze the effect of H2O2. After 2 h, yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) elicitor or chitosan was added to opening solution I. In the case of the H2O2 experiments, the following solutions were added to opening solution II as indicated: (a) control, 0.2 mm CaCl2; (b) 0.2 mm CaCl2 and 0.2 mm H2O2; or (c) 0.2 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, and 0.2 mm H2O2 (free external Ca2+ was about 0.1 mm). After a further incubation period, the leaves were blended in a blender (Waring, Torrington, CT), the resulting epidermal fragments were filtered out with a 30-μm nylon mesh, and guard cell aperture ratios were measured as described (Pei et al., 1997).

Elicitor Preparation

Chitosan was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego), prepared as previously described (Walker-Simmons et al., 1984), then dissolved in stomatal opening solution I. Yeast elicitor was prepared according to the method of Schumacher et al. (1987). In brief, 1 kg of commercial baker's yeast was dissolved in 1.5 L of sodium citrate buffer (20 mm, pH 7.0) and autoclaved at 121°C and 11 Nm−2 bar for 60 min. The autoclaved suspension was centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 min. The resulting supernatant was mixed with 1 volume of ethanol and stirred gently overnight. The resulting precipitate was then centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 min. The supernatant of this centrifugation step was subjected to another ethanol precipitation overnight. The elicitor precipitate was lyophilized and stored at −20°C until use.

[Ca2+]cyt Imaging Experiments

Epidermal strips of Arabidopsis leaves were mounted on coverslips with medical adhesive (Hollister Inc., Libertyville, IL) and incubated in a solution containing 5 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES/Tris (pH 6.15). To promote stomatal opening, the strip was illuminated for 2 h (photon fluency rate of 125 μmol m−2 s−1) at 22°C before measurements started. YC 2.1 [Ca2+]cyt imaging experiments were performed as described previously (Allen et al., 1999b, 2000). The present imaging system differed from the one described by Allen et al. (1999) and was outfitted with a 440- ± 10-nm filter with a 455 DCLP dichroic mirror (Chroma, Brattleboro, VT) for excitation and interchanging 485- ± 20-nm and 535- ± 15-nm filters for emission. Note that in the present and also recent studies (Allen et al., 2000, 2001; Hugouvieux et al., 2001), Arabidopsis lines were used that show higher cameleon expression levels than the initially reported studies (Allen et al., 1999b) and that these lines allowed imaging at a reduced excitation intensity that did not excite measurable chloroplast fluorescence. A slow baseline drift because of yellow fluorescent protein bleaching was linearly subtracted. The lowest ratio value in each individual experiment was defined as ratio 1. Transient duration was defined as the time interval between the start and end of a transient unless otherwise noted; period was defined as the average time between two peaks of consecutive transients. Results are reported as average ± se of the mean.

In Vitro Cameleon Assay

Fluorescence emission profiles of purified YC 2.1 protein were measured using a fluorimeter. Measurement was made in buffer (100 mm KCl and 10 mm MOPS [pH 7.2]) with or without 50 mm nicotinamide and with either nominally zero calcium (100 μm EDTA) or 4 mm CaCl2.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp experiments on Arabidopsis guard cells were performed by using an Axopatch 200 amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) as described (Pei et al., 1997). Liquid junction potentials were corrected. For data analysis, AXOGRAPH 3.5 (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) was used. Standard solutions contained 100 mm BaCl2, 0.1 mm DTT, and 10 mm MES-Tris (pH 5.6) in the bath and 10 mm BaCl2, 0.1 mm DTT, 4 mm EGTA, 0 or 5 mm NADPH, and 10 mm HEPES-Tris (pH 7.1) in the pipette. Exchange of initial bath solution with bath solution containing 10 μg mL−1 elicitor or chitosan was achieved by pipetting. Bath and pipette osmolalities were adjusted to 485 and 500 mmol kg−1, respectively, using d-sorbitol.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stephen Adams and Roger Tsien for support with in vitro measurements on recombinant cameleon and discussions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant no. GM 60396 to J.I.S. and training grant no. 3T32GM07240–25S1 to J.J.Y.), by the Department of Energy (grant no. 94ER2018–07 to J.I.S.), by the National Science Foundation (grant no. MCB 0077791 to J.I.S.), by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Feodor-Lynen fellowship to B.K.), and in part by the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (fellowship to Y.M.).

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Gethyn Allen.

Corresponding author; e-mail julian@biomail.ucsd.edu; fax 858–534–7108.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.012187.

LITERATURE CITED

- Allan AC, Fricker MD, Ward JL, Beale MH, Trewavas AJ. Two transduction pathways mediate rapid effects of abscisic acid in Commelina guard cells. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1319–1328. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GJ, Chu SP, Harrington CL, Schumacher K, Hoffman T, Tang YY, Grill E, Schroeder JI. A defined range of guard cell calcium oscillation parameters encodes stomatal movements. Nature. 2001;411:1053–1057. doi: 10.1038/35082575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GJ, Chu SP, Schumacher K, Shimazaki CT, Vafeados D, Kemper A, Hawke SD, Tallman G, Tsien RY, Harper JF et al. Alteration of stimulus-specific guard cell calcium oscillations and stomatal closing in Arabidopsis det3 mutant. Science. 2000;289:2338–2342. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GJ, Kuchitsu K, Chu SP, Murata Y, Schroeder JI. Arabidopsis abi1-1 and abi2-1 phosphatase mutations reduce abscisic acid-induced cytoplasmic calcium rises in guard cells. Plant Cell. 1999a;11:1785–1798. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.9.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GJ, Kwak JM, Chu SP, Llopis J, Tsien RY, Harper JF, Schroeder JI. Cameleon calcium indicator reports cytoplasmic calcium dynamics in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J. 1999b;19:735–747. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GJ, Muir SR, Sanders D. Release of Ca2+ from individual plant vacuoles by both InsP3 and cyclic ADP-ribose. Science. 1995;268:735–737. doi: 10.1126/science.7732384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR. Ca2+ signaling and control of guard-cell volume in stomatal movements. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2000;3:196–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR, Armstrong F. K+ channels of stomatal guard cells: abscisic acid-evoked control of the outward rectifier mediated by cytoplasmic pH. Planta. 1993;191:330–341. [Google Scholar]

- Blechert S, Brodschelm W, Hölder S, Kammerer L, Kutchan TM, Mueller MJ, Xia ZQ, Zenk MH. The octadecanoic pathway: signal molecules for the regulation of secondary pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4099–4105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume B, Nürnberger T, Nass N, Scheel D. Receptor-mediated increase in cytoplasmic free calcium required for activation of pathogen defense in parsley. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1425–1440. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.8.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton H, Knight MR, Knight H, McAinsh MR, Hetherington AM. Dissection of the ozone-induced calcium signature. Plant J. 1999;17:575–579. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clint GM, Blatt MR. Mechanisms of fusicoccin action: evidence for concerted modulations of secondary K+ transport in a higher plant cell. Planta. 1989;178:495–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00963820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva DLR, Hetherington AM, Mansfield TA. Synergism between calcium ions and abscisic acid in preventing stomatal opening. New Phytol. 1985;100:473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring CA, Irving HR, Parish RW. Effects of auxin and abscisic acid on cytosolic calcium and pH in plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9645–9649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring CA, McConchie RM, Venis MA, Parish RW. Auxin-binding-protein antibodies and peptides influence stomatal opening and alter cytoplasmic pH. Planta. 1998;205:581–586. doi: 10.1007/s004250050359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelli A, Higgins VJ, Blumwald E. Activation of plant plasma membrane Ca2+-permeable channels by race-specific fungal elicitors. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:269–279. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.1.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy S, Fricker MD, Read ND, Trewavas AJ. Role of calcium in signal transduction of Commelina guard cells. Plant Cell. 1991;3:333–344. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.4.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabov A, Blatt MR. Membrane voltage initiates Ca2+ waves and potentiates Ca2+ increases with abscisic acid in stomatal guard cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4778–4783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadwiger LA, Beckman JM. Chitosan as a component of pea-Fusarium solani interactions. Plant Physiol. 1980;66:205–211. doi: 10.1104/pp.66.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DWA, Hills A, Köhler B, Blatt MR. Ca2+ channels at the plasma membrane of stomatal guard cells are activated by hyperpolarization and abscisic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4967–4972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080068897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Wayne RO. Calcium and plant development. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1985;36:397–439. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sotomayor SMT, Santos-Briones CDL, Muñoz-Sánchez JA, Loyola-Vargas VM. Kinetic analysis of phospholipase C from Catharanthus roseus transformed roots using different assays. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:1075–1082. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.4.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugouvieux V, Kwak JM, Schroeder JIS. An mRNA cap binding protein, ABH1, modulates early abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2001;106:477–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Ritchie S, Assmann SM, Gilroy S. Abscisic acid signal transduction in guard cells is mediated by phospholipase D activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12192–12197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Muto S. Mechanism of peroxidase actions for salicylic acid-induced generation of active oxygen species and an increase in cytosolic calcium in tobacco cell suspension culture. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:685–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller T, Damude HG, Werner D, Doerner P, Dixon RA, Lamb C. A plant homolog of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase gp91phox subunit gene encodes a plasma membrane protein with Ca2+ binding motifs. Plant Cell. 1998;10:255–266. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.2.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight MR, Campbell AK, Smith SM, Trewavas AJ. Transgenic plant aequorin reports the effects of touch and cold-shock and elicitors on cytoplasmic calcium. Nature. 1991;352:524–526. doi: 10.1038/352524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopka J, Pical C, Hetherington AM, Müller-Röber B. Ca2+/phospholipid-binding (C2) domain in multiple plant proteins: novel components of the calcium-sensing apparatus. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;36:627–637. doi: 10.1023/a:1005915020760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan CY, Takemura H, Obie JF, Thastrup O, Putney JW. Effects of MeCh, thapsigargin and La3+ on plasmalemmal and intracellular Ca2+ transport in lacrimal acinar cells. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:C1006–C1015. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.6.C1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckie CP, McAinsh MR, Allen GJ, Sanders D, Hetherington AM. Abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure mediated by cyclic ADP-ribose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15837–15842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Choi H, Suh S, Doo IS, Oh KY, Choi EJ, Taylor ATS, Low PS, Lee Y. Oligogalacturonic acid and chitosan reduce stomatal aperture by inducing the evolution of reactive oxygen species from guard cells of tomato and Commelina communis. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:147–152. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRobbie EAC. ABA activates multiple Ca2+ fluxes in stomatal guard cells, triggering vacuolar K+(Rb+) release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12361–12368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220417197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh MR, Brownlee C, Hetherington AM. Abscisic acid-induced elevation of guard cell cytosolic Ca2+ precedes stomatal closure. Nature. 1990;343:186–188. [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh MR, Brownlee C, Hetherington AM. Visualizing changes in cytosolic-free Ca2+ during the response of stomatal guard cells to abscisic acid. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1113–1122. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.9.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh MR, Clayton H, Mansfield TA, Hetherington AM. Changes in stomatal behavior and guard cell cytosolic free calcium in response to oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:1031–1042. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh MR, Webb AAR, Taylor JE, Hetherington AM. Stimulus-induced oscillations in guard cell cytosolic free calcium. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1207–1219. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.8.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhard M, Grill E. Hydrogen peroxide is a regulator of ABI1, a protein phosphatase 2C from Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:443–446. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhard M, Rodriguez PL, Grill E. The sensitivity of ABI2 to hydrogen peroxide links the abscisic acid-response regulator to redox signalling. Planta. 2002;214:775–782. doi: 10.1007/s00425-001-0675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mithöfer A, Ebel J, Bhagwat AA, Boller T, Neuhaus-Url G. Transgenic aequorin monitors cytosolic calcium transients in soybean cells challenged with β-glucan or chitin elicitors. Planta. 1999;207:566–574. [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Pei ZM, Mori IC, Schroeder JI. Abscisic acid activation of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels in guard cells requires cytosolic NAD(P)H and is differentially disrupted upstream and downstream of reactive oxygen species production in the abi1-1 and abi1-2 protein phosphatase 2c mutants. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2513–2523. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill SJ, Desikan R, Clarke A, Hancock JT. Nitric oxide is a novel component of abscisic acid signaling in stomatal guard cells. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:13–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson RL, van Rossum DB, Gill DL. Store-operated Ca2+ entry: evidence for a secretion-like coupling model. Cell. 1999;98:487–499. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81977-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Kuchitsu K, Ward JM, Schwarz M, Schroeder JI. Differential abscisic acid regulation of guard cell slow anion channels in Arabidopsis wild-type and abi1 and abi2 mutants. Plant Cell. 1997;9:409–423. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Murata Y, Benning G, Thomine S, Klüsener B, Allen GJ, Grill E, Schroeder JI. Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature. 2000;406:731–734. doi: 10.1038/35021067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AH, Taylor A, Ripley SJ, Griffiths A, Trewavas AJ, Knight MR. Oxidative signals in tobacco increase cytosolic calcium. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1301–1310. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano LA, Jacob T, Gilroy S, Assmann SM. Increases in cytosolic Ca2+ are not required for abscisic acid-inhibition of inward K+ currents in guard cells of Vicia faba L. Planta. 2000;211:209–217. doi: 10.1007/s004250000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos W, Evers S, Hieke M, Tschöpe M, Schumann B. Shifts of intracellular pH distribution as a part of the signal mechanism leading to the elicitation of benzophenanthridine alkaloids. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:349–364. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftner RA, Raschke K. Electrical potentials in stomatal complexes. Plant Physiol. 1981;67:1124–1132. doi: 10.1104/pp.67.6.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders D, Brownlee C, Harper JF. Communicating with calcium. Plant Cell. 1999;11:691–706. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.4.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel D. Resistance response physiology and signal transduction. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:305–310. doi: 10.1016/1369-5266(88)80051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C, Schelle I, Liao YJ, Schroeder JI. Strong regulation of slow anion channels and abscisic acid signaling in guard cells by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9535–9539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Allen GJ, Hugouvieux V, Kwak JM, Waner D. Guard cell signal transduction. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001a;52:627–658. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Hagiwara S. Cytosolic calcium regulates ion channels in the plasma membrane of Vicia faba guard cells. Nature. 1989;338:427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Hagiwara S. Repetitive increases in cytosolic Ca2+ of guard cells by abscisic acid activation of nonselective Ca2+ permeable channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9305–9309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Kwak JM, Allen GJ. Guard cell abscisic acid signaling and engineering drought hardiness in plants. Nature. 2001b;410:327–330. doi: 10.1038/35066500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher HM, Gundlach H, Fiedler F, Zenk MH. Elicitation of benzophenanthridine alkaloid synthesis in Eschscholtzia cell cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 1987;6:410–413. doi: 10.1007/BF00272770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacke R, Hager H. Fungal elicitors induce a transient release of active oxygen species from cultured spruce cells that is dependent on Ca2+ and protein kinase activity. Planta. 1992;187:136–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00201635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A. Role of calcium and EGTA on stomatal movements in Commelina communis. Plant Physiol. 1985;79:1003–1005. doi: 10.1104/pp.79.4.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staxén I, Pical C, Montgomery LT, Gray JE, Hetherington AM, McAinsh MR. Abscisic acid induces oscillations in guard-cell cytosolic free calcium that involve phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1779–1784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Simmons M, Jin D, West CA, Hadwiger L, Ryan CA. Comparison of proteinase inhibitor-inducing activities and phytoalexin elicitor activities of a pure fungal endopolygalacturonase, pectic fragments, and chitosans. Plant Physiol. 1984;76:833–836. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb AAR, Larman MG, Montgomery LT, Taylor JE, Hetherington AM. The role of calcium in ABA-induced gene expression and stomatal movements. Plant J. 2001;26:351–362. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Kuzma J, Maréchal E, Graeff R, Lee HC, Foster R, Chua N-H. Abscisic acid signaling through cyclic ADP-ribose in plants. Science. 1997;278:2126–2130. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Shah J, Klessig DF. Signal perception and transduction in plant defense responses. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1621–1639. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann S, Nürnberger T, Frachisse JM, Wirtz W, Guern J, Hedrich R, Scheel D. Receptor mediated activation of a plant Ca2+-permeable ion channel involved in pathogen defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2751–2755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]