Abstract

F1-ATPase is an ATP-driven rotary motor in which a rod-shaped γ subunit rotates inside a cylinder made of α3β3 subunits. To elucidate the conformations of rotating F1, we measured fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between a donor on one of the three βs and an acceptor on γ in single F1 molecules. The yield of FRET changed stepwise at low ATP concentrations, reflecting the stepwise rotation of γ. In the ATP-waiting state, the FRET yields indicated a γ position ≈40° counterclockwise (= direction of rotation) from that in the crystal structures of mitochondrial F1, suggesting that the crystal structures mimic a metastable state before product release.

The F1-ATPase is a part of FoF1-ATP synthase that synthesizes ATP in F1, the water-soluble portion of the ATP synthase, from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) when protons pass through Fo, the membrane-embedded portion. Isolated F1, consisting of α3β3γδε subunits, hydrolyzes ATP as the reverse reaction. The minimum ATPase unit, α3β3γ (hereafter referred to as F1), is pseudo 3-fold symmetric: a rod-shaped, asymmetric γ subunit is surrounded by an α3β3 cylinder (1). Rotation of γ inside the α3β3 cylinder has been suggested (2–5) and confirmed by chemical (6) and optical (7, 8) methods. Direct observation under an optical microscope (8–11) has shown that F1 rotates in discrete 120° steps, each fueled by a single ATP molecule.

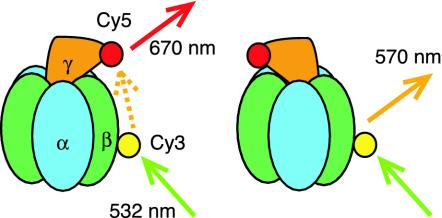

Several kinds of high-resolution crystal structures of mitochondrial F1 (MF1) have been solved (1, 12, 13), but it is unknown which rotation states these crystal structures correspond to or how closely these are related to the structure of actively rotating F1. To investigate the transient structures in rotating F1, we applied a single-pair fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) technique (14). We measured FRET between a donor (Cy3) on one of three βs and an acceptor (Cy5) on γ in single thermophilic F1 molecules fixed on a glass surface (Fig. 1). Because the FRET yield strongly depends on the distance between the two fluorophores, the FRET yield will change cyclically as the γ subunit rotates (15). The distance between labeled residues were estimated from the FRET yield and used to analyze the transient conformation of F1.

Fig. 1.

Visualization of the rotation of F1 through single-pair FRET: principle of the experiment.

Materials and Methods

Proteins. Cy5-maleimide was prepared as in ref.

16. The sole cysteine of a

mutant subcomplex of F1, α(C193S)3β(His-10

tag at N terminus)3γ(S107C) derived from thermophilic

Bacillus PS3, was labeled with Cy5-maleimide (molar ratio 1:2) in 20

mM Mops-KOH (pH 7.0), 100 mM KCl, and 5 mM glycine at 23°C for 30 min. The

cysteine of a mutant β(S205C) (without His tag) was labeled with

Cy3-maleimide at 1:2 in the same buffer excluding glycine at 23°C for 30

min. Free dyes were removed on a PD10 column (Amersham Pharmacia). The

(Cy5-γ)F1 was incubated with Cy3-β at 1:10 at 45°C

for 2 days, and free β subunit was removed on a size exclusion column

(Superdex 200, Amersham Pharmacia). The final preparation contained

0.7–1 mol Cy5 and 0.05–0.2 mol Cy3 per mol F1

(estimated from absorption spectra, using

,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

and

,

and  .

A solution of 0.05–0.5 nM labeled F1 in 50 mM KCl, 2 mM

MgCl2, 10 mM Mops-KOH (pH 7.0), 0.06–1 μM ATP, 70 mM

2-mercaptoethanol, 200 μg/ml glucose oxidase, 20 μg/ml catalase, and 4.5

mg/ml glucose was sandwiched between two KOH-cleaned quartz coverslips for

microscopic observation. Resulting thickness of the solution was ≈3 μm.

Previously, we found that His-tagged F1 rotates on a clean glass

surface (11), presumably bound

by the negatively charged surface. To determine the activity of labeled

β, a construct

α(C193S)3β(S205C)3γ(S107C) was

expressed and labeled with Cy3 at 1:8–20, resulting in 0.5–1.0 mol

of Cy3 per cysteine. ATPase activity was measured as described

(9).

.

A solution of 0.05–0.5 nM labeled F1 in 50 mM KCl, 2 mM

MgCl2, 10 mM Mops-KOH (pH 7.0), 0.06–1 μM ATP, 70 mM

2-mercaptoethanol, 200 μg/ml glucose oxidase, 20 μg/ml catalase, and 4.5

mg/ml glucose was sandwiched between two KOH-cleaned quartz coverslips for

microscopic observation. Resulting thickness of the solution was ≈3 μm.

Previously, we found that His-tagged F1 rotates on a clean glass

surface (11), presumably bound

by the negatively charged surface. To determine the activity of labeled

β, a construct

α(C193S)3β(S205C)3γ(S107C) was

expressed and labeled with Cy3 at 1:8–20, resulting in 0.5–1.0 mol

of Cy3 per cysteine. ATPase activity was measured as described

(9).

Microscope. A laser beam (532 nm, DPSS 532–200, Coherent Radiation, Palo Alto, CA) was introduced into an inverted microscope (IX70, Olympus) through a water-immersion objective (PlanApo ×60, numerical aperture 1.2, Olympus). Fluorescence was divided into <620-nm (Cy3) and >620-nm (Cy5) components (17) and focused onto an intensified (VS4–1845, Videoscope, Dallas) charge-coupled device (CCD-300T-IFG, Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN) camera. Bandpass filters (Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT) reduced the cross talk between Cy3 and Cy5 channels to <3%. The excitation efficiency of Cy5 at 532 nm was <0.03 times that of Cy3. Images recorded on a videotape were captured in a personal computer (LG3, Scion, Frederick, MD) and analyzed off-line with custom software. Because only Cy5 close to a donor emitted fluorescence, we could find FRET pairs (F1 having both Cy3 and Cy5) by looking for fluorescence of Cy5. Most FRET pairs (>99%) did not show time-dependent change of the FRET yield, presumably because of surface denaturation (18). In the Cy3 channel, we observed many more fluorescent spots that lack companion spots in the Cy5 channel. Most of them photo-bleached in a single step. These presumably represent F1 carrying a single Cy3 fluorophore without Cy5 acceptor.

Calculation of Distance Between FRET Pairs. The FRET yield

f was obtained experimentally as f = aCy5/(Cy3 +

aCy5), where Cy5 and Cy3 denote the fluorescence intensities above

the background and a is the ratio of the intensity change of two

dyes, ΔCy3/ΔCy5 (see Fig.

3E). The distance between the donor and acceptor was

calculated as R = Ro(1/f –

1)1/6, where f is the experimental FRET yield and

Ro is the Förster distance

(19). Ro

was determined as [(8.79 ×

1017)·n–4·κ2·QD·J]1/6

(nm), where J, the overlap integral, was calculated from measured

emission spectrum of (Cy5-γ)F1 and absorption spectrum of

(Cy3-β)F1 to be 8.85 × 10–13

M–1·cm3, QD

= 0.25 is the quantum yield of the donor measured with rhodamine-B (quantum

yield = 0.49; ref. 20) as

reference, n = 1.33 is the refractive index of water, and

κ2 = 0.667 ± 0.524 (see below) is the orientation

factor. The error in Ro was mainly from

κ2 and was estimated as δRo =

Ro·δ(κ2)/(6κ2).

Resulting Ro was 5.9 ± 0.8 nm. The error in

R was estimated as

( ,

where δf is the standard error for f.

,

where δf is the standard error for f.

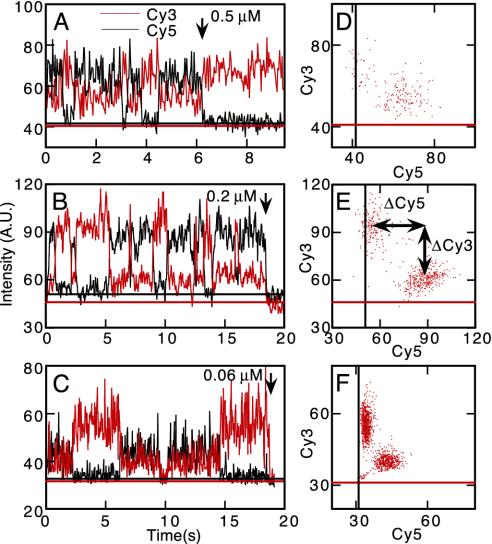

Fig. 3.

Changes in the FRET yield accompanying rotation. (A–C) Time courses of Cy3 (red) and Cy5 (black) fluorescence at different [ATP]. Arrows indicate photobleaching of Cy5 (A) or Cy3 (B and C). (D–F) Correlation between Cy3 and Cy5 intensities in A–C (data up to the arrow are scored). Straight lines in A–F represent the background intensities for Cy3 (red) and Cy5 (black) channels measured near the FRET pair.

Calculation of Orientation Factor. The orientation factor κ2 is defined as κ2 = 〈(cosθT – 3 cosθD cosθA)2〉, where θT is the angle between μD and μA, the donor emission and acceptor absorption transition moments, and θD is the angle between μD and d and θA between μA and d, where d is the vector connecting the donor and acceptor (19). Because none of these angles are known, we assigned arbitrary orientations to μD, μA, and d and calculated average κ2 for that combination while allowing μD and μA to wobble within a cone around the assigned axis. This calculation was repeated for all combinations of μD, μA, and d, giving the average and standard deviation for κ2. The cone angle ϕX (X = A or D) for the subnanosecond wobble of the fluorophore is related to the limiting and residual fluorescence anisotropy ro and rinf (21) by rinf = ro·[cosϕX(1 + cosϕX)/2]2. ro and rinf in turn are related with the steady-state anisotropy rs (21) by rs = (ro – rinf)/(1 + τ/τr) + rinf, in which τ is the fluorescence lifetime and τr the rotation correlation time of the dye. τ/τr was estimated, by assuming that τr is not much different from the correlation time of free dye in water, as (τ/τr)waterQprotein/Qwater, where Qprotein and Qwater are the quantum yields of the dye on protein and in water, and (τ/τr)water is the quantity for free dye in water that was measured as (τ/τr)water = (ro/rwater – 1), where rwater is the steady-state anisotropy of the free dye in water. The steady-state fluorescence anisotropy rs was measured in a cuvette by using a spectrofluorometer (F-4500, Hitachi, Tokyo) to be 0.29, 0.30, 0.26, and 0.17 for (Cy3-β)F1 (some proteins contain multiple Cy3), (Cy5-γ)F1, free Cy3, and free Cy5, respectively (λex = 550 and 650 nm, λem = 590 and 690 nm, respectively for Cy3 and Cy5). Lower limit of ro (giving lower limit of the cone angle) was measured as the steady-state anisotropy of the dyes in glycerol at 0°C to be 0.36 for Cy3 and 0.39 for Cy5. The quantum yield Q was measured as 0.25, 0.26, 0.03, and 0.25, respectively, for Cy3-F1, Cy5-F1, free Cy3, and free Cy5, using rhodamine-B as a reference. From measured rs, ro, and Q, the wobble cone semiangles were obtained as ϕD >25° and ϕA >33° for Cy3 and Cy5 on F1.

Derivation of Possible Positions of FRET Pair. The linker length

from the dye center to the labeled cysteine sulfur was estimated to be 1.2 and

1.7 nm for Cy3 and Cy5, respectively, from the bond angles and lengths. The

donor and acceptor were assumed to be within the linker lengths of the labeled

cysteines (β205 and γ107; β203 and γ99 in the

MF1 sequence). Because γ97–100 in MF1 are

unresolved in the crystals, possible positions of γ99-S (mutated to

cysteine) were calculated as follows: the peptide backbone was extended from

the visible γ101 to γ99 by assigning standard bond lengths and

angles while allowing arbitrary rotations around N—Cα

(Φ) and C—Cα (Ψ) bonds. If resultant γ99-C

is not within 1.0 nm (maximum possible length between γ99-C and

γ96-C) from γ96-C, the structure was discarded. Carbonyl oxygens

and amino nitrotgens and γ99-Cβ were modeled

automatically assuming the standard l-amino acid configuration (no

need to model a side chain for γ100 glycine). Finally,

Cα—Cβ bond in γ99 was rotated into

an arbitrary angle to locale γ99S. During the construction, if an added

atom (excluding hydrogen) was within 0.15 nm of the visible atoms in the

crystal, that structure was also discarded. After 5,000 trials, we obtained

562, 462, and 2,323 possible γ99S locations for native MF1,

, and

MF1-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD). For each location, we assigned

a sphere of radius 1.7 nm and assumed that the acceptor could be anywhere in

the sphere with the same probability. The acceptor spheres seen in

Fig. 5 show the outermost

circumference enclosing all possible acceptor position. In the native

MF1 (1),

γ91–96 and γ101 are also missing, and we adopted the

, and

MF1-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD). For each location, we assigned

a sphere of radius 1.7 nm and assumed that the acceptor could be anywhere in

the sphere with the same probability. The acceptor spheres seen in

Fig. 5 show the outermost

circumference enclosing all possible acceptor position. In the native

MF1 (1),

γ91–96 and γ101 are also missing, and we adopted the

structure (12) for this

part.

structure (12) for this

part.

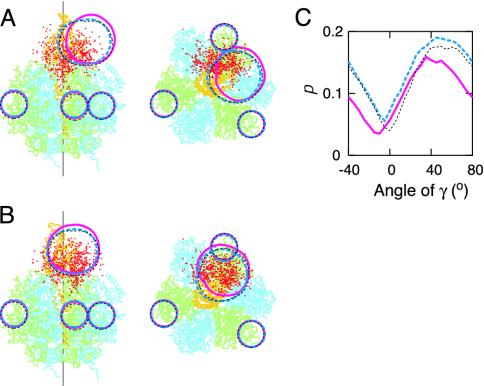

Fig. 5.

(A) Side (Left) and top (Right) views of the

backbone trace of the structure of

MF1

(13), color-coded as in

Fig. 1 A. Small and

large spheres represent geometrically allowed positions of the donor (Cy3) and

acceptor (Cy5), respectively, on the native MF1,

MF1

(13), color-coded as in

Fig. 1 A. Small and

large spheres represent geometrically allowed positions of the donor (Cy3) and

acceptor (Cy5), respectively, on the native MF1,  , and

MF1-DCCD structures (blue, black, and pink); the degree of twist in

γ varies among the three structures, resulting in the slight deviations

of large circles. Red dots indicate possible acceptor positions calculated

from the FRET results (see Materials and Methods). The black line

indicates the putative rotation axis. (B) The acceptor sphere (and

γ) is rotated counterclockwise by 40°.(C) Probability

(p) of finding red dots in the acceptor sphere as functions of

γ angle (θ) for native MF1 (blue), MF1-DCCD

(pink), and

, and

MF1-DCCD structures (blue, black, and pink); the degree of twist in

γ varies among the three structures, resulting in the slight deviations

of large circles. Red dots indicate possible acceptor positions calculated

from the FRET results (see Materials and Methods). The black line

indicates the putative rotation axis. (B) The acceptor sphere (and

γ) is rotated counterclockwise by 40°.(C) Probability

(p) of finding red dots in the acceptor sphere as functions of

γ angle (θ) for native MF1 (blue), MF1-DCCD

(pink), and  (black). Larger values between p(θ) and p(θ +

120°) are plotted.

(black). Larger values between p(θ) and p(θ +

120°) are plotted.

Positions of the acceptor compatible with our FRET results (see

Fig. 5 A and

B, red dots) were obtained as follows. First, we randomly

assigned a donor position from the donor sphere, removing the positions inside

the protein by discarding the positions within 0.4 nm of the atoms in the

crystal structure. We also chose μD and μA

randomly. Instead of rotating the acceptor, we rotated the donor into three

equivalent positions, assuming the same linker vector and μD for

the three (simple 120° rotations). Then we selected three FRET efficiency

values f, one for a high-FRET state and two for low-FRET states,

assuming a Gaussian distribution for f with half-width at

1/e maximum equaling the experimental standard error. The remaining

task was to find three donor-acceptor vectors d that are

compatible with the chosen conditions. This was done in an iterative search

for the orientation and absolute value of d by first assigning

random orientations to the three vectors d. (i) We

calculated three orientation factors from the chosen orientations of

d, μD, and μA, while allowing

μD and μA to wobble in the respective cones.

(ii) This gave three distances |d|,

from which we determined the acceptor position. Two answers were obtained,

above and below F1, and we always chose the one above.

(iii) From the acceptor position, we extracted three orientations of

d, disregarding the absolute values, and repeated steps

i-iii. We stopped the iteration when the differences in the

three orientations between two adjacent iteration cycles all became

<0.5°.In ≈10% of trials, the calculation did not converge within 500

iterations and we gave up. For a chosen set from ≈1,800 donor positions,

μd and μA, we always attempted five independent

iterations starting from different and randomly selected orientations of

d. These gave consistent results within 0.2 ± 0.04 nm

(mean ± SD), when converged. Finally, if the obtained acceptor position

was within 0.4 nm of the crystal atoms that position was discarded (to avoid

physical conflicts). Red dots seen in Fig.

5 A and B represent results obtained in this

way. When we rotated γ for a better fit with the experimental FRET

efficiencies (see Fig. 5), the

final check of physical conflicts was made for each γ orientation; the

number of remaining red dots did not depend significantly on the γ

angle, ranging from 1,340 to 1,414, 1,144 to 1,308, and 1,078 to 1,187,

respectively, for native MF1,  , and

MF1-DCCD.

, and

MF1-DCCD.

The probability of finding a FRET-compatible acceptor position (see red dots in Fig. 5 A and B) among the possible acceptor positions in the crystal structures was estimated by counting the number of red dots within the acceptor-linker length of a possible γ99-S position, averaging this number over all possible γ99-S positions, and dividing the average by the total number of the red dots. We also calculated the probabilities for rotated γ by rotating the acceptor spheres.

Results

Visualization of F1 Rotation Through Single-Pair

FRET. To label one of the three βs with Cy3

(Fig. 1), we expressed β

alone with an engineered cysteine and labeled it with Cy3. The labeled β

was exchanged into an independently expressed F1 of which γ

had been labeled with Cy5, resulting in 0.05–0.2 mol of labeled β

and 0.7–1.0 mol of labeled γ per mol of F1. The effect

of β mutation and labeling was checked in yet another F1

construct where all three βs had the cysteine and were fully labeled

(Fig. 2): at low [ATP] where

hydrolysis rate was proportional to [ATP], the apparent rate of ATP binding

was estimated as

and

and

for the labeled and unlabeled F1. When only one of three β was

labeled, therefore, the rotation at low [ATP] where ATP binding is rate

limiting will consist of alternate one slow and two fast steps, as has been

demonstrated for an F1 chimera of normal and slow β subunits

(22).

for the labeled and unlabeled F1. When only one of three β was

labeled, therefore, the rotation at low [ATP] where ATP binding is rate

limiting will consist of alternate one slow and two fast steps, as has been

demonstrated for an F1 chimera of normal and slow β subunits

(22).

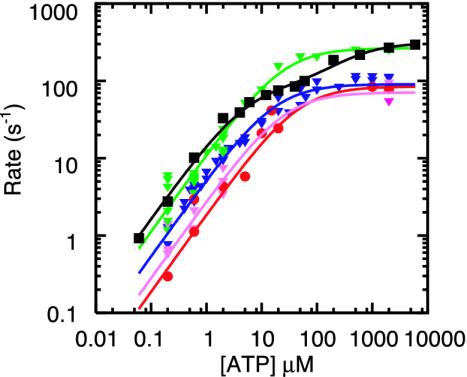

Fig. 2.

Effect of labeling on ATPase activity (11). F1 with a sole cysteine at γ was labeled with Cy3 (green) or unlabeled (black). F1 with four cysteines (one each in βs and γ) were fully labeled (red), 50% labeled (pink), or unlabeled (blue). Smooth curves are fits with Vmax[ATP]/([ATP] + kM) (green, red, pink, blue) or with (VmaxkM + Vmax2[ATP]2)/([ATP]2 + kM2[ATP] + kMkM2) (black). The rate of ATP binding, kon, was estimated as Vmax/kM = (1.1 ± 0.3) × 107 M–1·s–1 (green), (5.4 ± 0.9) × 106 M–1·s–1 (blue), (1.9 ± 1.1) × 106 M–1·s–1 (red), (2.8 ± 1.2) × 106 M–1·s–1 (pink), and (1.65 ± 0.32) × 107 M–1·s–1 (black).

Under an epi-fluorescence microscope, Cy3 was selectively excited at 532 nm, and emissions from Cy3 and Cy5 were simultaneously imaged. The two showed alternate and stepwise intensity changes in the presence of ATP (Fig. 3 A–C), indicating alternation of the FRET yield between high and low states. The rate of alternation was faster at higher [ATP], as expected for ATP-dependent stepwise rotation of γ. When Cy3 lost its companion acceptor by photobleaching of Cy5, the fluorescence of Cy3 increased (arrow in Fig. 3A). If Cy3 bleaches before Cy5, both are expected to disappear simultaneously, as was indeed observed (arrows in Fig. 3 B and C). There was a clear correlation between Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence, showing the existence of two FRET states (Fig. 3 D–F).

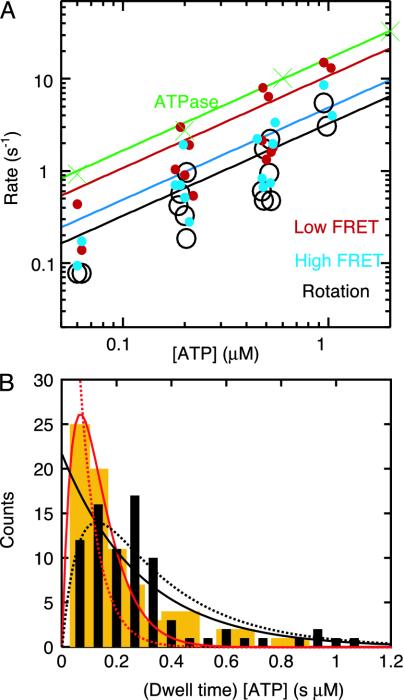

The transition rates between the high- and low-FRET states, defined as the inverse of the averaged dwell times, (1/〈τH〉 and 1/〈τL〉), were each proportional to [ATP] (Fig. 4), confirming that the change in the FRET yield represents rotation steps. The rate of rotation, estimated as 1/(〈τH〉 + 〈τL〉), was also proportional to [ATP] (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

(A) ATP dependence of the transition rate from the high and low

FRET states (1/〈τH〉 and

1/〈τL〉) and the rotation rate estimated as

1/(〈τH〉 + 〈τL〉) (160 FRET

states were analyzed in 15 FRET pairs). For comparison, the rate of ATP

hydrolysis in F1 without the subunit labeling is shown

(Fig. 2 A). Lines show

linear fits with slopes (± SE) of (4.9 ± 0.7), (10.9 ±

1.3), (3.3 ± 0.4), and (16.5 ± 0.2) × 106

M–1·s–1 for

1/〈τH〉, 1/〈τL〉, rotation,

and ATPase, respectively. (B) Histogram of dwells, τ, of the high

(black) and low (orange) FRET states. Solid curves show fit for case

i in the text: low FRET dwell (red) with

constant·τ[ATP]exp( ),

where

),

where

is the ATP binding constant of unlabeled F1 from

Fig. 2, and high FRET dwells

(black) with

constant·exp(

is the ATP binding constant of unlabeled F1 from

Fig. 2, and high FRET dwells

(black) with

constant·exp( ),

where

),

where

is for labeled β (χ2 = 257, 80 dwells, 15 FRET pairs).

Dashed curves show fit for case ii in the text: low FRET dwells (red)

with

constant·exp(

is for labeled β (χ2 = 257, 80 dwells, 15 FRET pairs).

Dashed curves show fit for case ii in the text: low FRET dwells (red)

with

constant·exp( ),

and high FRET dwells (black) with

constant·{exp

),

and high FRET dwells (black) with

constant·{exp ,

where

,

where  and

and

are fixed to the experimental values

above (χ2 = 497, 80 dwells, 15 FRET pairs).

are fixed to the experimental values

above (χ2 = 497, 80 dwells, 15 FRET pairs).

For 120° stepping, three FRET states are expected, as observed for a

different donor-acceptor pair

(15). In our experiments, two

of three states were indistinguishable, leading to two possibilities:

(i) the high-FRET state with a longer dwell

(〈τH〉/〈τL〉 = 2.3 ±

0.3) involved one slow step associated with the labeled β and the

low-FRET state involved two normal steps, or (ii) the high-FRET state

involved one normal and one slow steps and the low-FRET state involved one

normal step. For each case, the rates of ATP binding,

and

and

were calculated from the observed

dwell times and compared with the rates estimated from ATP hydrolysis. For

case i,

were calculated from the observed

dwell times and compared with the rates estimated from ATP hydrolysis. For

case i,  is given as

〈τH〉–1[ATP]–1

= (3.8 ± 0.7) × 106

M–1·s–1 and

is given as

〈τH〉–1[ATP]–1

= (3.8 ± 0.7) × 106

M–1·s–1 and

as

2〈τL〉–1[ATP]–1

= (1.6 ± 0.3) × 107

M–1·s–1, both

of which agree with

as

2〈τL〉–1[ATP]–1

= (1.6 ± 0.3) × 107

M–1·s–1, both

of which agree with  and

and

estimated from the ATPase activity.

For case ii,

estimated from the ATPase activity.

For case ii,

and

and

,

inconsistent with the ATPase results. Thus, the low-FRET state involved two

normal steps, and the high-FRET state involved one slow step. Histograms of

dwell times (Fig. 4B)

were also better fit with model i.

,

inconsistent with the ATPase results. Thus, the low-FRET state involved two

normal steps, and the high-FRET state involved one slow step. Histograms of

dwell times (Fig. 4B)

were also better fit with model i.

ATP-Waiting Conformation of F1. The FRET yields in the high- and low-FRET states were calculated from the observed fluorescence intensities as 0.56 ± 0.06 and 0.15 ± 0.03, respectively, corresponding to the donor-acceptor distances of 5.7 ± 0.9 and 7.9 ± 1.0 nm. Because the low-FRET state involves two rotation steps, the distance between the two dyes will change as 5.7, 7.9, and 7.9 nm during rotation. These values are to be compared with the known crystal structures of F1.

Three different crystal structures of MF1 have been solved: a

“native MF1” structure in which AMP-PNP, ADP, and none

occupy the three catalytic sites

(1), an

“MF1-DCCD” structure that is inhibited with DCCD and

has the same nucleotides as the native MF1

(12), and an

“ ”

structure, which is inhibited with aluminum fluoride and has two ADP

”

structure, which is inhibited with aluminum fluoride and has two ADP

and one ADP

(13). To compare these

structures, we adopt the triangle made of three α-carbons of

α-GLU26 as the frame of reference

(23); a line perpendicular to,

and passing through the center of, the triangle is assumed to be the rotation

axis. The conformation of γ inside the

α3β3 cylinder varies little among the three

crystal structures, whereas part of γ near the upper orifice of the

α3β3 cylinder is twisted clockwise (opposite

to the rotation direction) up to 20° and 11° in

and one ADP

(13). To compare these

structures, we adopt the triangle made of three α-carbons of

α-GLU26 as the frame of reference

(23); a line perpendicular to,

and passing through the center of, the triangle is assumed to be the rotation

axis. The conformation of γ inside the

α3β3 cylinder varies little among the three

crystal structures, whereas part of γ near the upper orifice of the

α3β3 cylinder is twisted clockwise (opposite

to the rotation direction) up to 20° and 11° in  ) and

MF1-DCCD, respectively, compared with the native MF1

when viewed from above in Figs.

1 and

5

(13).

) and

MF1-DCCD, respectively, compared with the native MF1

when viewed from above in Figs.

1 and

5

(13).

In these structures, the position of the residue labeled with the acceptor, which is on the protruding portion of γ, varies to some extent, while the donor residues occupy the same positions. Possible positions of the donor and acceptor in the three MF1 structures are essentially the same (Fig. 5A, small and large spheres for the donor and acceptor, respectively). The acceptor spheres are larger, because several residues around the acceptor site are unresolved in the structures and linker length of the acceptor is longer than that of the donor. Starting with the donor positions that are common to all structures, we calculated acceptor positions that are compatible with the three FRET efficiencies above (red dots in Fig. 5 A and B). The FRET-estimated acceptor positions overlap best with the acceptor sphere (large ones) when γ was rotated counterclockwise by ≈40° in all MF1 crystals (Fig. 5C). Because FRET measurements were done at low ATP concentrations where binding of ATP limits the rotation rate, this conformation corresponds to the ATP-waiting state of F1.

Discussion

Rotation Mechanism of F1-ATPase. Our FRET results suggest that the conformation of γ in the ATP-waiting state of F1 is ≈40° counterclockwise, or ≈40° in the rotation direction, from that in the MF1 crystal structures. Then, which kinetic state do the MF1 structures correspond to? At least one intermediate state during rotation, other than the ATP-waiting state, has so far been resolved: binding of ATP to F1 in the ATP-waiting state induces a counterclockwise ≈90° substep, and F1 remains at this intermediate angle for ≈2 ms before undergoing a further ≈30° substep induced by product release (11). When F1 is inhibited on tight binding of MgADP, the rotation stalls at ≈80° (24), suggesting that the inhibited conformation resembles that of the intermediate state after the ≈90° substep. Naively, crystal structures are expected to be close to the 90°/80° conformation rather than the ATP-waiting conformation, because crystallization involves long incubation with MgADP or MgATP, a condition that favors the formation of the MgADP-inhibited enzyme (25), as has been suggested in cross-linking studies (26). If so, expected acceptor positions in the ATP-waiting state should be 30°/40° ahead the crystal structures (Fig. 5B). Our FRET results (Fig. 5, red dots) indeed point to this position, suggesting that the crystal structures are closer to the 90°/80° conformation rather than the ATP-waiting conformation (0° or 120°).

Whether rotation of F1-ATPase requires filling of all three catalytic sites with a nucleotide (27) or filling two is sufficient (28) is an important, but unresolved, issue. Because γ orientation in both the 2- and 3-nt crystal structures differ from our results by 40°, the ATP-waiting conformation likely binds a single nucleotide. If so, rotation under our experimental conditions occurs by filling at most two catalytic sites.

The protruding part of γ in crystals of F1 from Escherichia coli (29) or the thermophilic bacterium (Y. Shirakihara, personal communication) is twisted counterclockwise compared with the MF1 structures, such that possible acceptor positions in these bacterial crystals are close to the large circles in Fig. 5B. Our FRET results obtained with the thermophilic F1 are consistent with these positions. In particular, the thermophilic bacterial crystal contained only 1 nt, suggesting again that the ATP-waiting state corresponds to a single-nucleotide state.

Our interpretations above rest on the assumption that the crystal

structures closely mimic an active rotation intermediate hosting the same

number of nucleotides. However, the lattice packing may have deformed the

F1 structure in the crystals

(12,

13). The twist of γ in

and

MF1-DCCD, relative to native MF1, is maximal around the

orifice of the α3β3 cylinder and is smaller

both above and below the orifice, suggesting some distortion. In particular,

native MF1 and MF1-DCCD both have two catalytic

nucleotides, and yet γ in MF1-DCCD is twisted clockwise up to

11°. Significantly, the MF1-DCCD crystal is more closely packed

than the native MF1 crystal, and the bacterial crystals in which

γ is twisted counterclockwise are less densely packed. A possibility

thus exists that 2-nt MF1 in a relaxed crystal might show a γ

orientation similar to the bacterial one. If so, our FRET results might point

to the necessity of three-site filling. FRET with different donor-acceptor

pairs will help resolve the remaining ambiguity.

and

MF1-DCCD, relative to native MF1, is maximal around the

orifice of the α3β3 cylinder and is smaller

both above and below the orifice, suggesting some distortion. In particular,

native MF1 and MF1-DCCD both have two catalytic

nucleotides, and yet γ in MF1-DCCD is twisted clockwise up to

11°. Significantly, the MF1-DCCD crystal is more closely packed

than the native MF1 crystal, and the bacterial crystals in which

γ is twisted counterclockwise are less densely packed. A possibility

thus exists that 2-nt MF1 in a relaxed crystal might show a γ

orientation similar to the bacterial one. If so, our FRET results might point

to the necessity of three-site filling. FRET with different donor-acceptor

pairs will help resolve the remaining ambiguity.

Analysis of Protein Conformation Through Single-Pair FRET. FRET is a standard technique for measuring distances in the 1- to 10-nm range and often used for analyzing conformation of proteins and nucleotides in solution (30). For analysis of transient protein conformations, FRET measurement on individual donor-acceptor pairs is essential because protein molecules behave stochastically and their operations cannot be synchronized.

In this study, we have demonstrated that single-pair FRET reveals a transient conformation of F1-ATPase with nanometer precision. The resolution, limited mainly by the ambiguity in the orientation factor and the relatively large linker length between the fluorophore and target residue, could be improved by synthesizing short-linker fluorophores and searching for a proper fluorophore-residue combination that warrants an extensive wobble of the fluorophore on the protein surface.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Nishizaka, T. Ariga, and Y. Shirakihara for critical discussions. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to R.Y.), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to R.Y.), Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology, and Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; MF1, mitochondrial F1; DCCD, dicyclohexylcarbodiimide.

References

- 1.Abrahams, J. P., Leslie, A. G., Lutter, R. & Walker, J. E. (1994) Nature 370, 621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyer, P. & Kohlbrenner, W. (1981) in Energy Coupling in Photosynthesis, eds. Selman, B. R. & Selman-Reimer, S. (Elsevier, Amsterdam), pp. 231–240.

- 3.Cox, G., Jans, D. A., Fimmel, A., Gibson, F. & Hatch, L. (1984) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 849, 62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oosawa, F. & Hayashi, S. (1986) Adv. Biophys. 22, 151–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer, P. D. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1458, 252–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan, T. M., Bulygin, V. V., Zhou, Y., Hutcheon, M. L. & Cross, R. L. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 10964–10968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabbert, D., Engelbrecht, S. & Junge, W. (1996) Nature 381, 623–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noji, H., Yasuda, R., Yoshida, M. & Kinosita, K., Jr. (1997) Nature 386, 299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuda, R., Noji, H., Kinosita, K., Jr., & Yoshida, M. (1998) Cell 93, 1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adachi, K., Yasuda, R., Noji, H., Itoh, H., Harada, Y., Yoshida, M. & Kinosita, K., Jr. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7243–7247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasuda, R., Noji, H., Yoshida, M., Kinosita, K., Jr., & Itoh, H. (2001) Nature 410, 898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbons, C., Montgomery, M. G., Leslie, A. G. W. & Walker, J. E. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menz, R. I., Walker, J. E. & Leslie, A. G. (2001) Cell 106, 331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelley, A., Michalet, X. & Weiss, S. (2001) Science 292, 1671–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Börsch, M., Diez, M., Zimmermann, B., Reuter, R. & Graber, P. (2002) FEBS Lett. 527, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funatsu, T., Harada, Y., Tokunaga, M., Saito, K. & Yanagida, T. (1995) Nature 374, 555–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinosita, K., Jr., Itoh, H., Ishiwata, S., Hirano, K., Nishizaka, T. & Hayakawa, T. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 115, 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinosita, K., Jr., Yasuda, R., Noji, H. & Adachi, K. (2000) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 355, 473–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Förster, T. (1948) Annalen Physik 2, 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishikawa, M., Hirano, K., Hayakawa, T., Shigeru, H. & Brenner, S. (1994) Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 33, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinosita, K., Jr., Kawato, S. & Ikegami, A. (1984) Adv. Biophys. 17, 147–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ariga, T., Masaike, T., Noji, H. & Yoshida, M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 24870–24873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, H. & Oster, G. (1998) Nature 396, 279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirono-Hara, Y., Noji, H., Nishiura, M., Muneyuki, E., Hara, K. Y., Yasuda, R., Kinosita, K., Jr., & Yoshida, M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13649–13654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milgrom, Y. M. & Boyer, P. D. (1990) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1020, 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsunoda, S. P., Muneyuki, E., Amano, T., Yoshida, M. & Noji, H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 5701–5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber, J. & Senior, A. E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35422–35428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyer, P. D. (2002) FEBS Lett. 512, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hausrath, A. C., Gruber, G., Matthews, B. W. & Capaldi, R. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13697–13702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selvin, P. R. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]