Abstract

Type IV secretion (T4S) systems translocate DNA and protein effectors through the double membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. The paradigmatic T4S system in Agrobacterium tumefaciens is assembled from 11 VirB subunits and VirD4. Two subunits, VirB9 and VirB7, form an important stabilizing complex in the outer membrane. We describe here the NMR structure of a complex between the C-terminal domain of the VirB9 homolog TraO (TraOCT), bound to VirB7-like TraN from plasmid pKM101. TraOCT forms a β-sandwich around which TraN winds. Structure-based mutations in VirB7 and VirB9 of A. tumefaciens show that the heterodimer interface is conserved. Opposite this interface, the TraO structure shows a protruding three-stranded β-appendage, and here, we supply evidence that the corresponding region of VirB9 of A. tumefaciens inserts in the membrane and protrudes extracellularly. This complex structure elucidates the molecular basis for the interaction between two essential components of a T4S system.

Keywords: TraO–TraN, structural biology, bacterial conjugation, pilus, DNA transfer

Type IV secretion (T4S) systems mediate the translocation of DNA and protein substrates across bacterial cell envelopes (1, 2). One T4S system subfamily, the conjugation machines, transmit DNA substrates to bacterial recipients and are responsible for widespread dissemination of antibiotic resistance and other virulence traits among bacterial pathogens (3). A second T4S subfamily, the effector translocators, deliver DNA or protein substrates to eukaryotic target cells to aid in establishment of infection (4).

In Gram-negative bacteria, the T4S systems are composed of a translocation channel spanning the inner and outer membranes and an extracellular pilus (3, 5–7). The translocation channel elaborated by the phytopathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens is composed of an inner membrane translocase whose subunits include the VirD4, VirB4, and VirB11 ATPases, the polytopic subunit VirB6, and bitopic subunits VirB8 and VirB10. In the periplasm, the channel likely is composed of VirB2 pilin and the periplasmic domains of VirB8 and VirB9. At the outer membrane (OM), a pore must form for passage of the substrate and the pilus, but, at this time, the composition or structure of this pore is not known. Extending from the cell surface is the pilus composed of VirB2 pilin and minor components VirB5 and VirB7. VirB7, a lipoprotein, interacts with VirB9 (see below) but also can be identified in the extracellular milieu even independently of other VirB protein production (1).

For the A. tumefaciens VirB/D4 machine and related T4S systems, the VirB9 subunit is the best candidate for assembling as an OM channel or pore (6–9). VirB9-like proteins share weak sequence similarities with pore-forming secretins associated with the types II and III secretion systems, which also export macromolecular substrates across the OMs of Gram-negative bacteria (10). As shown for many secretins, VirB9 fractionates with the OM as a complex with a cognate lipoprotein, in this case VirB7 (11). VirB7 interacts with and stabilizes VirB9, and formation of the VirB7–VirB9 heterodimer, in turn, stabilizes other type IV components (12). In the A. tumefaciens VirB/D4 T4S system, a disulfide bridge is formed between the reactive Cys-24 and Cys-262 residues of VirB7 and VirB9, respectively (12–15). VirB9 proteins and secretins also form higher-order multimers, with themselves or with other T4S proteins, detectable by chemical cross-linking (15–17). However, secretins typically are refractory to detergent solubilization from the OM and display a heat-modifiable mobility shift in SDS-polyacrylamide gels, as is also the case for OM β-barrel proteins, including porins and other small molecule transporters (18). VirB9 proteins instead migrate as monomers and do not show heat-modifiable mobility in protein gels (8). These differences may reflect a more dynamic or reversible self-association of VirB9 or suggest that VirB9-like proteins adopt a different architecture at the OM than the ring-shaped secretins.

In this study, we solved the NMR structure of a complex formed between the pKM101-encoded TraO C-terminal domain (TraOCT) and full-length TraN, homologs, respectively, of VirB9 and VirB7. TraOCT adopts a β-sandwich fold, around which TraN winds. This structure defines the molecular basis of VirB9 interaction with VirB7. In a mutational analysis of the A. tumefaciens VirB7 and VirB9 subunits, we supply corroborative experimental support for the heterodimer interface identified by the TraN–TraOCT NMR structure. Interestingly, two edge strands of the TraOCT β-sandwich (β4 and β6) together with the β5 strand, located opposite the TraN-binding site, form an appendage that protrudes markedly from the β-sandwich, and the equivalent loop in VirB9 is partially exposed on the A. tumefaciens bacterial surface.

Results and Discussion

Structure Description.

We identified a soluble fragment (residues 177–294; TraOCT) of TraO, the VirB9 homolog encoded by the pKM101 conjugation system, and purified it with a soluble version (residues 17–49) of TraN, the VirB7 homolog encoded by the same system. Details of how such fragments were identified, the complex produced, and the structure determined by NMR are provided in supporting information (SI) Figs.6 and 7 and SI Table 1.

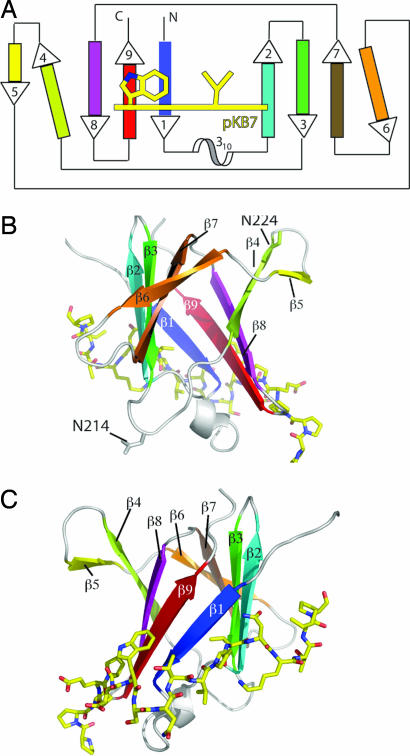

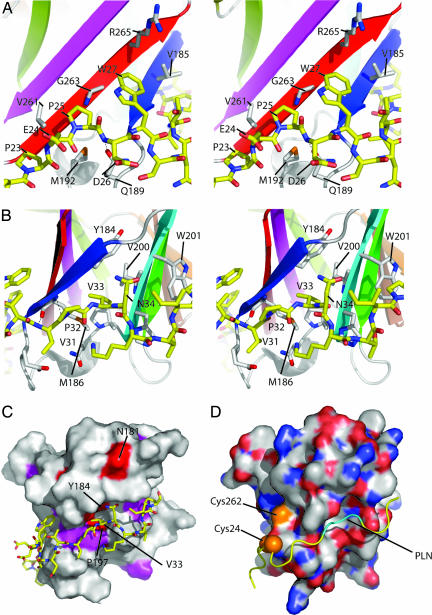

TraOCT has an immunoglobin-like β-sandwich fold consisting of nine β-strands and a short stretch of 310 helix between the first and second strands (Fig. 1). By using DALI (19) to compare TraOCT to known structures, the structure is most similar to the recently described Near Transporter domain of IsdH/HarA from Staphylococcus aureus (DALI Z-score 5.6) and the human interleukin 4 receptor (DALI Z-score 5.5). Immunoglobin-like folds are found in many proteins of diverse function, and thus the structural similarity does not yield any functional insight. Six strands (β1–3, β7–9) form the body of the sandwich; three (β4–6) are more loosely connected and form a distinctive β-appendage protruding out of the body of the sandwich. The first sheet comprises strands β5, β4, β8, β9, and β1; the second sheet comprises β2, β3, β7, and β6 (Fig. 1). Because the residue numbering for the two proteins does not overlap, it should be clear that, in the following analysis, residue numbers 21–42 refer to TraN, and residue numbers 177–271 refer to TraOCT (Fig. 2). Overall, TraN forms an extended structure that wraps around β1 of TraOCT and caps one of the two edges of the β-sandwich. In addition, TraN interacts with β9, β2, and N-terminal residues of the β1–β2 linker. The interface buries 1,680 Å2 of surface area. From N to C terminus along the TraN sequence, the first major contact with TraOCT is between carbon atoms of Pro-23, Glu-24, and Pro-25 (TraN) and Met-192 of the β1–β2 linker and Val-261, Gly-263 of β9 (TraO) (Fig. 3A). Asp-26 amide is H-bonded by Gln-189 in the β1-β2 linker. Trp-27 packs onto a shelf comprising Gly-263 and Arg-265 of β9 and Val 185 of β1 (Fig. 3A). Ser-28, Asn-29, and Thr-30 form a sharp turn in the TraN chain that positions the main-chain NH and O of Val-31 to H-bond with the O and NH of Met-186 in β1 (Fig. 3B). Pro-32 prevents this β-sheet-like H-bond pattern from developing down the TraN chain and positions Val-33 to insert into a hydrophobic pocket between the two sheets of the β-sandwich. This striking hydrophobic contact contributes to the TraOCT hydrophobic core as the deeply buried side chain of Val-33 inserts between Tyr-184, Met-186 of β1, and Val-200 of β2 (Fig. 3 B and C). Finally, the 1H,15N HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Correlation) spectrum of 15N TraN/unlabeled TraOCT clearly shows that the Nδ protons of Asn-34 are involved in a hydrogen bond with TraOCT, because it has an unusual chemical shift of δN118 ppm and δH 8.5 and 9.1 ppm and has a weaker intensity signal than the other Asn/Gln side-chain TraN amides, suggesting that it tumbles as part of the whole complex rather than exhibiting internal flexibility on a fast timescale (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, there is no information to indicate which TraOCT atoms form H bonds with Asn-34.

Fig. 1.

Overview of TraOCT/TraN complex structure. (A) Schematic topology diagram of TraOCT with β-strands color-ramped as in SI Fig. 7C. The 310 helix is colored white. TraN is represented as a yellow line crossing strands β1, β2, and β9 of TraOCT. Residues Trp-27 and Val-33, two major contact points with TraOCT, are shown. Strands β4 and β6 are shown at an angle to their adjacent strands to reflect their weaker H-bonding interactions. (B) Rotation of the model through 180° about the vertical axis with respect to C to show strands β4, β5, and β6 on the opposite face to the TraN-binding site. Residues N214 and 224 (N216 and N226 in A. tumefaciens) VirB9 are shown in ball-and-stick representation. (C) Stereo diagram of structure showing TraOCT in cartoon representation with loops, 310 helix, and β-strands colored as in A. TraN is shown as a stick model with carbon atoms colored yellow, nitrogen atoms colored blue, and oxygen atoms colored red. The same representations and color scheme is used in B and C. PyMOL was used for all structure figures (www.pymol.org).

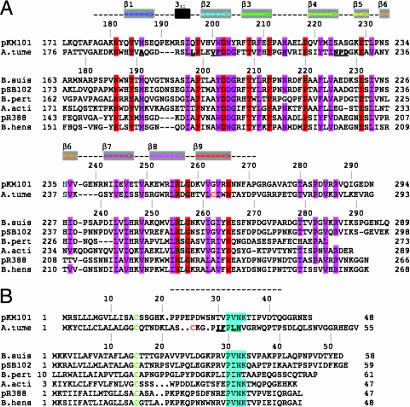

Fig. 2.

Sequence conservation of the VirB9–VirB7 interaction site. (A) Sequence alignment of VirB9 homologs: pKM101 TraO (pKM101, NP#511196); A. tumefaciens VirB9 (A. tume, NP#396496); B. suis VirB9 (B. suis, NP#699268); pSB102 TraK (pSB102, NP#361041); Bordetella pertussis VirB9 (B. pert, NP#882293); Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans magB09 (A. acti, NP#067575); pR388 TrwF (pR388, CAA57030); Bartonella henselae TrwF (B. hens, CAF28337). Identical residues are shaded red, and conserved residues are shaded pink. The portion of the sequence modeled as structure is shown as a dashed line above the sequence, gray boxes containing colored arrows show the β-strands, and the 310 helix is shown as a black box. (B) Sequence alignment of VirB7 homologs: pKM101 TraN (pKM101, NP#511194); A. tumefaciens VirB7 (A. tume, NP#536291); B. suis VirB7 (B. suis, AAN33275); pSB102 TraI (pSB102, NP#361043); Bordetella pertussis VirB7 (B.pert, NP#882291); Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans magB07 (A. acti, NP#067577); pR388 TrwH (pR388, FAA00034); B. henselae TrwH (B. hens, AAM82208). VirB7 homologs were manually aligned based on the lipid-modified cysteine (green), the position of the A. tumefaciens cysteine, and the conserved “P[ILV]NK” VirB9-interaction motif (cyan). The portion of the sequence modeled as structure is shown as a dashed line above the alignment. In A and B, the cysteine residues involved in A. tumefaciens VirB9–VirB7 disulfide bond formation are colored orange, and key residues mutated in the A. tumefaciens proteins are shown in bold and underlined.

Fig. 3.

Structural detail of the TraOCT–TraN interaction site. (A) Detail of the interaction between TraN residues 23–27 and TraOCT. TraOCT main chain is depicted as a cartoon colored according to the scheme in Fig. 1. TraN and interacting side chains of TraOCT are shown as sticks colored white or yellow for carbon atoms in TraOCT or TraN, respectively, blue for nitrogen, red for oxygen, and orange for sulfur. (B) Detail of the interaction between TraN residues 31–34 and TraOCT using the same representation as A. (C) Surface representation of TraOCT colored white for no/low conservation, magenta for high conservation, and red for identical residues as defined by Fig. 2A. Identical residues on the surface of TraOCT and V33 of TraN are labeled. (D) Surface representation of modeled A. tumefaciens VirB9CT with the backbone ribbon of TraN superposed, shown in the same orientation as the pKM101 structure in C. VirB9CT is colored white for carbon, blue for nitrogen, red for oxygen, and orange for sulfur. Potential locations of VirB7 cysteine residue 24 are marked with orange spheres, and the “PLN” sequence predicted to bind to the hydrophobic pocket is marked as cyan backbone.

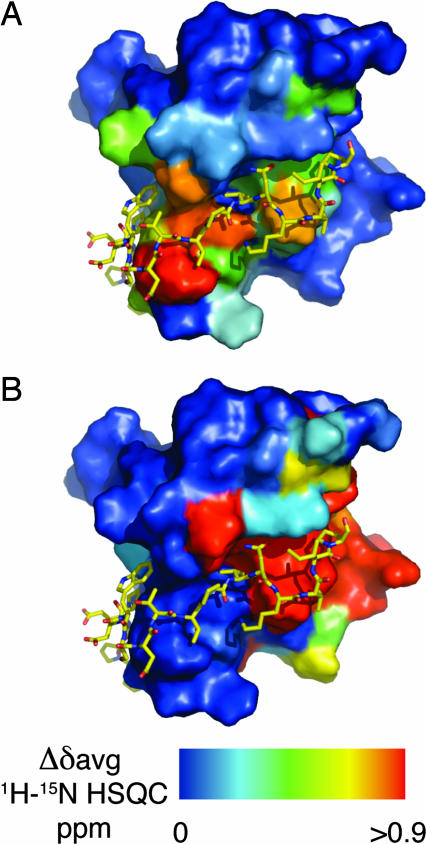

The differences in the average chemical shifts (Δδavg) between the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled TraOCT alone or in a 1:1 molar ratio with unlabeled TraN were mapped onto the structure of the TraOCT/TraN complex. All of the major differences lie very close to the interface of the two proteins, which is consistent with no global conformational changes in TraOCT upon TraN binding (Fig. 4A and B). We also examined the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled TraOCT fractions that eluted from the gel filtration column as a higher-molecular-weight species. When compared with monomeric TraOCT, one extensive surface patch exhibited either large differences in chemical shifts or ablation of cross-peak intensity. This region covered strands β2, β3, β7, residues Lys-180, Gln-183, and Tyr-184 in and around β1, and the β6–β7 linker, and overlaps partially with the TraN-binding site (Fig. 4B). This partial overlap may explain how TraN prevents TraOCT oligomerization.

Fig. 4.

Conformational changes in VirB9 upon binding of TraN. TraOCT shows no global conformational change upon TraN binding. Differences in the average chemical shift 1H-15N HSQC (Δδavg) are plotted as a color ramp on the surface of TraOCT. Blue surface represents residues that exhibit Δδavg <0.1ppm, and red denotes Δδavg >0.9ppm or ablation of cross peak intensity. (A) Difference between 15N-labeled TraOCT monomer alone and bound to unlabeled TraN, shown from the same view as Fig. 1C. (B) Difference between 15N-labeled TraOCT monomer and dimer shown from same view as in A. TraN is shown to indicate the partial overlap of residues at the TraN interface with those exhibiting a high Δδavg.

Conservation of the VirB7–VirB9 Interaction.

Close homologs of TraO were identified by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) and were aligned by using ClustalW. The TraO/VirB9 homologs are phylogenetically conserved, and the sequence alignment of pKM101 TraO and A. tumefaciens VirB9 C-terminal domains shows many identical or well-conserved residues. We used the sequence alignment as the basis for modeling the A. tumefaciens VirB9CT domain using Modeller (20) and default settings (Fig. 3D). In A. tumefaciens, the interacting VirB7/VirB9 proteins form a disulfide bridge between Cys-24 of VirB7 and Cys-262 of VirB9. These residues are highlighted in the sequence alignments and on the modeled structure (orange, Figs. 2 and 3D), showing that Cys-262 of A. tumefaciens VirB9 is equivalent to Gly-263 of TraO. TraO Gly-263 is very close to Pro-25 and Trp-27 of TraN, and it is conceivable that the Cys-24 of A. tumefaciens VirB7 could be in an equivalent position to either of those TraN residues.

It was not possible to identify all of the corresponding TraN/VirB7 homologs by using BLAST or to align them by using ClustalW because the sequences are short and divergent. However, one strikingly conserved feature of the TraN/VirB7 homologs is a P[ILV]NK motif that in TraN (residues 32–35) interacts with a deep hydrophobic pocket on TraOCT (Figs. 2B and 3C). This motif is located 15–17 residues from the lipidated cysteine residue, a distance that might be crucial in defining the position of VirB9 with respect to the membrane.

Mutational Analysis of the VirB7-VirB9CT Interface of A. tumefaciens.

We introduced mutations at residues predicted to form the interface in the VirB7–VirB9 heterodimer of A. tumefaciens and assayed for effects on dimerization, protein stability, and virulence of the corresponding A. tumefaciens strains. In VirB7, we mutated residues I28, F29, L31, and N32 in and around the conserved “P[ILV]NK” motif (Fig. 2B) to alanine (SI Table 2). Strains producing the two double mutants I28A/F29A and L31A/N32A as well as the triple mutant I28A/F29A/N32D (L31 of A. tumefaciens is equivalent to V33 of TraN; Fig. 2) accumulated the VirB7 derivatives at WT levels, but VirB9 was undetectable, consistent with a predicted heterodimerization defect (12). Strains producing the VirB7 mutant proteins accumulated low levels of VirB10. These strains also were defective for assembly of the disulfide bridge between Cys-24 residues of two VirB7 monomers. As expected, strains producing the VirB7 mutant proteins failed to assemble T pili, transfer oncogenic T-DNA to plants, and transfer a mobilizable IncQ plasmid to recipient A. tumefaciens cells.

In VirB9, we introduced mutations in and around the hydrophobic pocket into which L31 (V33 in TraN) inserts (SI Table 2). The VirB9 F203W (equivalent to residue W201 in TraOCT) and A191M (equivalent to residue M186 in TraOCT) mutant proteins could not be detected, consistent with a predicted heterodimerization defect, although we cannot rule out the possibility of other destabilizing effects, e.g., misfolding. These mutant proteins also did not support pilus production, virulence, or gene transfer. The V202W (equivalent to V200 in TraOCT) mutant protein was stable and formed the VirB7 disulfide cross-link but showed defects in functional assays. This mutation might still perturb the dimer interface or formation of higher-order VirB7–VirB9 multimers. Another mutation, L198F in the β1–β2 linker, also resulted in loss of detectable VirB9, pilus production, and DNA transfer. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the mutations may result in protein instability, taken together, engineered mutants in A. tumefaciens VirB7 and VirB9 appear to indicate that noncovalent interactions between VirB7 and VirB9 (notably between the P[ILV]NK motif of VirB7 and the hydrophobic pocket of VirB9) are necessary to promote not only the formation of the disulfide bridge between the proteins but also to generate an active complex.

Evidence for Surface Accessibility of VirB9.

One of the most intriguing features of the NMR structure of TraOCT and the modeled structure of VirB9CT is the β4–β6 region extending from the C-terminal globular domain. We tested whether this region spans the OM. Previously, we showed that dipeptide LG insertions at several positions along the length of VirB9, including insertions after N216 and N226, were permissive for VirB9 function (8). N216 is in the β3–β4 loop, and the TraO equivalent, N214, is on the surface of the protein at the furthest point of the loop; N226 (N224 in A. tumefaciens VirB9) is located at the end of β4 (Figs. 1B and 2). We thus introduced a FLAG epitope after N216 and N226 as well as Cys substitution mutations at N216, N226, P227, and D228 to test for surface accessibility.

We initially observed that anti-VirB9 polyclonal antibodies reacted with native VirB9 produced in WT cells by immunofluorescence microscopy (SI Fig. 8). Most fluorescent foci were located at A. tumefaciens cell poles, although foci also were evident at other sites on the cell periphery, consistent with previous findings (21, 22). These antibodies did not react with intact cells of a ΔvirB9 mutant strain, establishing the specificity of the reaction for VirB9.

Next, we assayed for surface accessibility of the FLAG epitopes. As shown in Fig. 5A, the anti-FLAG antibodies reacted with VirB9FL epitope-tagged at residue N226 but not with material on the surfaces of intact cells producing native VirB9 or cells producing the VirB9FL variant epitope-tagged at residue N216. Most cells had polar foci, although foci were evident elsewhere at the cell periphery similar to findings for native VirB9 (21, 22). Upon conversion of cells to spheroplasts, both VirB9FL variants reacted with the FLAG antibodies (Fig. 5A). Fluorescence was more uniform than observed with whole cells, possibly because of redistribution of the VirB9 variants upon spheroplasting.

Fig. 5.

Surface accessibility of VirB9 Cys substitution mutations and FLAG epitope tagged VirB9 derivatives. (A) Intact cells (Upper) and spheroplasts (Lower) were reacted with anti-FLAG antibodies and examined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Strains: B9, PC1009 with pBLC373 producing native VirB9; 216 & 226, PC1009 producing VirB9FL derivatives with FLAG epitope at these residues. (B) (Upper) Intact cells were incubated with the Cys reactive reagent MPB with (+) or without (-) preblocking with AMS. (Lower) Intact cells were untreated (-) or treated (+) with mPEG-maleimide (mPEG) (5 kDa). Strains: ΔB9, PC1009; ΔB9(B9), PC1009(pBLC373) producing native VirB9; PC1009 with pBLC373 derivatives carrying Cys substitutions at positions indicated.

We also tested for surface accessibility of VirB9 by introducing Cys residues at positions N216, N226, P227, and D228 and then assaying for alkylation of these residues. The sulfhydryl reactive reagent 3-(N-maleimidylpropionyl) biocytin (MPB) readily crosses the OM, whereas 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (AMS) only inefficiently crosses the OM because its molecular mass of 536 Da exceeds the exclusion limit for porins. Thus, pretreatment of intact cells with AMS thus should block surface-displayed Cys residues from MPB labeling (23). As shown in Fig. 5B, most or all of native VirB9, which dimerizes via its unique C262 residue with VirB7, reacted only weakly with MPB, and labeling was unaffected by AMS pretreatment. The N216C mutant protein reacted with MPB, but labeling was unaffected by AMS pretreatment, adding to evidence that this residue resides in the periplasm. In contrast, MPB strongly labeled the N226C substitution mutant in the absence of AMS pretreatment, and labeling was significantly diminished in AMS-pretreated cells. MPB also labeled the P227C and D228C mutant proteins, albeit less strongly than N226C, and again AMS pretreatment diminished MBP labeling. Similarly, native VirB9 and the N216C mutant protein did not react with mPEG-maleimide, whose large size (5 kDa) restricts labeling exclusively to surface-accessible Cys residues (Fig. 5B). By contrast, mPEG-maleimide reacted with the N226C and P227C mutant proteins and more weakly with the D228C mutant protein, as shown by a mobility shift of ≈5 kDa. As observed with MPB labeling, mPEG-maleimide labeled the N226C mutant protein most strongly and the P227C and D228C mutant proteins progressively more weakly. All of VirB9FL variants and Cys-substitution mutants under study were fully functional insofar as the corresponding strains translocated T-DNA and the IncQ plasmid RSF1010 at WT frequencies and elaborated T pili (data not shown). Taken together, therefore, results of the immunofluorescence microscopy and scanning cysteine accessibility method studies, supplied strong evidence that residues N226 and P227 of native VirB9 are surface-displayed, indicating that the protruding β4–6 region identified in the NMR structure spans the A. tumefaciens OM.

Conclusion

The structure of the VirB7-interacting domain of VirB9 bound to VirB7 elucidates the molecular basis of the interaction between the two proteins. The domain itself is an independent folding unit, suggesting that full-length VirB9 is a modular protein. The interface between the TraN and TraOCT is extensive and unusual. Many interactions involving β-fold-containing proteins are mediated through β-strand addition (termed β-addition), whereby a β-strand of one interacting partner is added to the edge of a β-sheet in the other interacting partner (24, 25). TraN instead wraps around its binding partner perpendicularly to the direction of the sandwich and wedges one of its residues (V33) in the gap between the two β-sheets. VirB9 exhibits a defined structural scaffold, and sequence homology within the VirB9 family of proteins is high, and, thus, the surface position of interacting residues is likely to be similar across the VirB9 family of proteins. This may not be the case for the VirB7 family of proteins, where sequence homology is low and no defined structure was observed. However, the structure-based functional studies presented here indicate that the VirB9/VirB7 interface is conserved.

The T4S apparatus is a macromolecular machine that actively assists protein or nucleoprotein secretion through the double membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. This process should require passage through a pore at the OM, but identification of the pore has not yet been possible. One possible candidate is the VirB9 protein that is known to fractionate from the OM and is strongly associated with VirB7, a small lipoprotein, which is found only at the OM (8, 26). Here, we supply experimental evidence that VirB9 is surface-exposed, and we identify a minimal structure in the C-terminal domain, the β4–β6 region, involved in the OM topology. Our findings support a general model that VirB9 is a component of an OM channel complex; however, further studies are needed to determine the VirB9 stoichiometry, subunit composition, and overall structure of this proposed channel.

T4S systems contribute to infectious diseases through the exchange of genetic material, including antibiotic-resistance genes, among bacterial pathogens, and by the direct secretion of macromolecules into eukaryotic cells. VirB7 and VirB9 form a keystone interaction essential for assembly of the apparatus into a functioning secretion system. The structure of the VirB7–VirB9 interaction we present here provides the basis for a rational approach to the disruption of this interaction in other bacterial systems. Small molecules targeted against this interaction may be useful drugs to combat human infectious diseases where T4S plays a crucial role.

Materials and Methods

Protein Preparation, NMR Spectroscopy, and Structure Calculations.

Details of protein preparation, NMR spectroscopy, and structural calculations can be found in SI Text.

A. tumefaciens Strains and Plasmids, Protein Analyses and Immunodetection, Virulence, and Conjugation Assays.

Details of this section can be found in SI Text.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy.

A. tumefaciens cells were preinduced for 4 h for synthesis of VirB proteins in broth induction medium and then placed on a sterile microscope slide coverslip and induced for an additional 24 h. Cells were fixed by sequential additions of 0.1% polylysine (60 μl) and 16% paraformaldehyde–0.5% glutaraldehyde (100 μl). After fixation, cells were treated with 100 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4 (100 μl), with or without lysozyme (2 mg/ml) and EDTA (100 μM). Cells were incubated overnight with primary antibody (1:100 in PBS 1% BSA) specific for the FLAG epitope (M2) or VirB9 and then with the second antibody, Rhodamine red-X goat anti-mouse IgG/M (for detection of the FLAG epitope) or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit antibodies (for detection of VirB9). Labeled cells were visualized in a BX60 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) equipped with a magnification ×100 oil immersion phase-contrast objective by either fluorescence or differential interference contrast microscopy.

Labeling with MPB.

Cysteine-accessibility experiments were carried out as described (27, 28). Briefly, 2 OD600 of a induced A. tumefaciens strain PC1009 producing Cys-substituted VirB9 derivatives were resuspended in 500 μl of buffer A [100 mM Hepes (pH 7.5)/250 mM sucrose/25 mM MgCl2/0.1 mM KCl). Cells were untreated or treated with AMS (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (100 μM final concentration) for 7 min at room temperature, then treated with MPB (Molecular Probes) (100 μM final concentration) for 5 min at 25°C. Biotinylation was quenched with 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Labeling with Monomethoxy Polyethylene Glycol (mPEG)-Maleimide.

vir-induced cultures of A. tumefaciens strain PC1009 producing Cys-substituted VirB9 derivatives were concentrated to an OD600 = 20, washed, and resuspended in 500 μl of 50 mM NaHPO4 buffer, pH 7.0. Cells were untreated or treated with AMS (100 μM final concentration) for 7 min at room temperature, washed to remove the AMS, and suspended in 500 μl of 50 mM NaHPO4 buffer, pH 7.0. mPEG-maleimide (5-kDa molecular mass; Nektar Therapeutics, San Carlos, CA) (5 mM final concentration) was added, and cells were incubated for 5 min at 25°C. 2-Mercaptoethanol (20 mM final concentration) was added to quench the reaction. Cells were incubated in protein sample buffer at 65°C for 15 min, and mPEG-maleimide modification of VirB9 variants was assessed by SDS/PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis with anti-VirB9 antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation and Detection of Labeled Cys Residues.

MPB-labeled cells were solubilized, and VirB9 variants were immunoprecipitated to recover VirB9 from extracts containing other MPB-labeled proteins as described (7). After SDS/PAGE and protein transfer, nitrocellulose membranes were incubated in the presence of avidin HRP (1:10,000 dilution of 2 mg/ml stock solution; Pierce, Rockford, IL). Biotinylated proteins were detected by chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr G. Kelly for providing assistance with the 800-MHz spectrometer at the Medical Research Council National NMR Centre at the National Institute of Medical Research, Mill Hill, London, U.K., and Dr. Robert Sarra (Birkbeck College) for mass spectrometry analysis. This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Grant 065932 (to G.W.) and National Institutes of Health Grant GM48746 (to P.J.C.).

Abbreviations

- AMS

4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid

- MPB

3-(N-maleimidylpropionyl) biocytin

- T4S

type IV secretion

- TraOCT

TraO C-terminal domain.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2OFQ).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0609535104/DC1.

References

- 1.Christie PJ, Atmakuri K, Krishnamoorthy V, Jakubowski S, Cascales E. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:451–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeo HJ, Waksman G. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1919–1926. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.1919-1926.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroder G, Lanka E. Plasmid. 2005;54:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cascales E, Christie PJ. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:137–150. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christie PJ. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2004;1694:219–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cascales E, Christie PJ. Science. 2004;304:1170–1173. doi: 10.1126/science.1095211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atmakuri K, Cascales E, Christie PJ. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:1199–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakubowski SJ, Cascales E, Krishnamoorthy V, Christie PJ. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3486–3495. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.10.3486-3495.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawley TD, Klimke WA, Gubbins MJ, Frost LS. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;224:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thanassi DG. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;4:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayan N, Guilvout I, Pugsley AP. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez D, Spudich GM, Zhou XR, Christie PJ. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3168–3176. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3168-3176.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spudich GM, Fernandez D, Zhou XR, Christie PJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7512–7517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron C, Thorstenson YR, Zambryski PC. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1211–1218. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1211-1218.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson LB, Hertzel AV, Das A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8889–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan Q, Carle A, Gao C, Sivanesan D, Aly KA, Hoppner C, Krall L, Domke N, Baron C. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26349–26359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoppner C, Carle A, Sivanesan D, Hoeppner S, Baron C. Microbiology. 2005;151:3469–3482. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nouwen N, Ranson N, Saibil H, Wolpensinger B, Engel A, Ghazi A, Pugsley AP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8173–8177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holm L, Sander C. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sali A, Blundell TL. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar RB, Xie YH, Das A. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:608–617. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judd PK, Kumar RB, Das A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11498–11503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505290102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson NS, So SS, Martin C, Kulkarni R, Thanassi DG. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53747–53754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrison SC. Cell. 1996;86:341–343. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remaut H, Waksman G. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao TB, Saier MH., Jr Microbiology. 2001;147:3201–3214. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-12-3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bogdanov M, Heacock PN, Dowhan W. EMBO J. 2002;21:2107–2116. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Bogdanov M, Dowhan W. EMBO J. 2002;21:5673–5681. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.