Abstract

The outcome of Helicobacter pylori infection has been associated with specific virulence-associated bacterial genotypes. The present study aimed to investigate the gastric histopathology in Portuguese and Colombian patients infected with H. pylori and to assess its relationship with bacterial virulence-associated vacA, cagA, and iceA genotypes. A total of 370 patients from Portugal (n = 192) and Colombia (n = 178) were studied. Corpus and antrum biopsy specimens were collected from each individual. Histopathological features were recorded and graded according to the updated Sydney system. H. pylori vacA, cagA, and iceA genes were directly genotyped in the gastric biopsy specimens by polymerase chain reaction and reverse hybridization. Despite the significant differences between the Portuguese and Colombian patient groups, highly similar results were observed with respect to the relation between H. pylori genotypes and histopathology. H. pylori vacA s1, vacA m1, cagA+ genotypes were significantly associated with a higher H. pylori density, higher degrees of lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates, atrophy, the type of intestinal metaplasia, and presence of epithelial damage. The iceA1 genotype was only associated with epithelial damage in Portuguese patients. These findings show that distinct H. pylori genotypes are strongly associated with histopathological findings in the stomach, confirming their relevance for the development of H. pylori-associated gastric pathology.

Helicobacter pylori colonizes the human stomach and establishes a long-term infection of the gastric mucosa. 1 The persistent colonization induces gastritis and is associated with the development of peptic ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis, and gastric carcinoma. 2 In general, the prevalence of H. pylori-related diseases is not directly proportional to the prevalence of H. pylori colonization. This may be because of several factors, such as genetic diversity among humans, 3 environmental factors, such as diet 4-6 age at first infection, and the genetic variability of H. pylori. Despite the high degree of genetic heterogeneity among H. pylori isolates, 7 there is evidence for the existence of distinct genetic lineages, 8 that may play a role in its pathogenicity. The relevance of several specific H. pylori genes has been studied in the past. vacA encodes a vacuolating cytotoxin which is excreted by H. pylori and damages epithelial cells. 9,10 The gene is present in all strains, and comprises two variable parts. 11 The s region (encoding the signal peptide) is located at the 5′ end of the gene and exists as a s1 or s2 allele. Within type s1 several subtypes (s1a, s1b, and s1c) can be distinguished. 12 The m-region (middle) occurs as a m1 or m2 allele. The mosaic combination of s- and m-region allelic types determines the production of the cytotoxin and is associated with pathogenicity of the bacterium. 11 vacA m1 type strains have been associated with greater gastric epithelial damage than m2 strains. 13 cagA (cytotoxin-associated gene) is considered as a marker for the presence of the pathogenicity (cag) island of ∼35 kbp. 14 Infection with cagA+ strains increases the risk for the development of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer. 15,16 Recently, a novel gene has been discovered, designated iceA (induced by contact with epithelium). There are two main allelic variants of the gene, ie, iceA1 and iceA2. 17 The function of iceA1 is not yet clear, but there is significant homology to a type II restriction endonuclease. The expression of iceA1 is up-regulated on contact between H. pylori and human epithelial cells and is possibly associated with peptic ulcer disease, 17,18 although other studies failed to confirm these initial results 19 or found a reverse relationship. 20 The present study aimed to investigate the gastric histopathology in Portuguese and Colombian patients infected with H. pylori and to assess its relationship with bacterial virulence-associated vacA, cagA, and iceA genotypes.

Materials and Methods

Patients

A total of 370 H. pylori-infected patients from Portugal and Colombia were studied. Portuguese patients (n = 192, 173 males and 19 females; age 43.3 ± 6.9 years) were recruited from shipyard workers during a screening program for (pre)malignant lesions of the gastric mucosa. Patients provided informed consent and underwent standard gastroscopy in 1998 in Hospital de S. João (Porto, Portugal). None of the patients had gastric cancer, 21 (11.0%) had duodenal ulcer, and eight (4.2%) had a gastric ulcer. Biopsy specimens were taken from corpus and antrum.

Colombian patients (n = 178, 73 males and 105 females; age 55.9 ± 8.4 years) were from the Andean region of Nariño, a part of Colombia with an extremely high prevalence of gastric cancer. All patients were participants of a randomized 6-year chemoprevention trial of gastric dysplasia performed in the towns of Tuquerres and Pasto, Nariño. Only patients with atrophy were selected for this trial, which followed a factorial design comprising anti-H. pylori therapy, as well as vitamin C and β-carotene treatment. One of the patients had peptic ulcer disease and none had gastric cancer. Biopsy specimens were obtained in 1998 by gastroscopy from the corpus and antrum of the stomach.

Histopathology

Two gastric biopsy specimens from the antrum (one from the greater curvature and one from the incisura angularis) and one from the corpus were immersed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained by hematoxylin and eosin, Alcian blue-periodic acid Schiff, and modified Giemsa. Only cases with adequately sized biopsy specimens of both antral and corpus mucosa were accepted for histological assessment by experienced pathologists, who were blinded with respect to the clinical information of each patient.

The following histopathological parameters were scored on an ordinal scale (0 to 3) using the criteria as described in the updated Sydney classification system 21 : H. pylori density, chronic inflammation, polymorphonuclear activity (neutrophil activity), and glandular atrophy. Whenever present, intestinal metaplasia was typed as complete, mixed (complete and incomplete), or incomplete. Surface epithelial degeneration was scored as present or absent. Results from the two antrum biopsy specimens were combined and whenever differences were observed, the highest score was considered for statistical analyses.

DNA Isolation from Gastric Biopsies and vacA, cagA, and iceA Genotyping

Antral biopsies were obtained, immediately placed in liquid nitrogen, and then transferred in dry ice to −80°C freezers. Total DNA was extracted from gastric biopsy specimens using the method described by Boom and colleagues. 22 Briefly, biopsies were homogenized in guanidinium isothiocyanate, using a sterile micropestle (Merck). DNA was captured onto silica particles, washed, and eluted in 100 μl of 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3. Two μl was used for each polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Subsequently, vacA and cagA genotypes were determined by multiplex PCRs followed by reverse hybridization on a line probe assay (LiPA) as described earlier 12,23 For amplification of the iceA1 and iceA2 genes, allele-specific PCR reactions were performed as described 18,24

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed in SPSS version 8.0. The Pearson chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess the relationships between individual genotypes and the presence of epithelial damage, atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia. Only cases containing single genotypes were included, and cases containing multiple genotypes were excluded. The t-test was used to analyze the age distributions between the different patient groups. Histopathological parameters, scored on ordinal scales (from 0 to 3), were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney test. Logistic regression analysis was used to relate the vacA, cagA, and iceA genotypes of H. pylori. Age (in 5-year classes) and gender were included as possible confounders. Selection of variables was based on a likelihood ratio test, using a significance level of 0.05 for inclusion or elimination.

Results

A total of 370 patients from Portugal and Colombia were endoscoped and gastric biopsy specimens were obtained from corpus and antrum. Comparison of the Portuguese and Colombian patients (Table 1) ▶ revealed several differences between the two groups. The mean age of the Colombian patients was significantly higher than that of the Portuguese patients (P < 0.001). Also, the gender distribution was different, because 90.1% of the Portuguese patients were male, versus only 40.4% of the Colombian patients (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Portuguese and Colombian Patients Participating in this Study

| Portugal n = 192 | Colombia n = 178 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean | 43.3 ± 6.9 | 55.9 ± 8.4 |

| Range | 24–62 | 37–74 |

| Gender (M/F) | 173/19 | 72/106 |

| vacA genotype | ||

| s1a/m1 | 3 (1.6%) | 7 (3.9%) |

| s1a/m2a | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| s1b/m1 | 60 (31.3%) | 145 (81.5%) |

| s1b/m2a | 12 (6.2%) | 5 (2.8%) |

| s2/m2a | 57 (29.7%) | 13 (7.3%) |

| Multiple* | 59 (30.7%) | 8 (4.5%) |

| cagA genotype | ||

| Positive | 116 (60.4%) | 161 (90.4%) |

| Negative | 76 (39.6%) | 17 (9.6%) |

| iceA genotype | ||

| A1 | 54 (28.1%) | 55 (30.9%) |

| A2 | 68 (35.4%) | 77 (43.3%) |

| Multiple† | 63 (32.8%) | 39 (21.9%) |

| Untyped‡ | 7 (3.7%) | 7 (3.9%) |

*More than one vacA genotype detected.

†More than one iceA genotype detected.

‡The iceA genotype could not be determined.

Histopathological parameters were scored according to the updated Sydney classification system in biopsy specimens from antrum and corpus and the grades of various parameters were determined using visual analogue scales. 21 Genotypes were only determined in the antral biopsy specimens and not in the corpus biopsies.

The vacA, cagA, and iceA status was analyzed for all 370 H. pylori-infected patients (Table 1) ▶ . The prevalence of vacA subtypes was different between Colombian and Portuguese patients. Subtype s1b was less prevalent in Portuguese (37.5%) as compared to Colombian patients (84.3%). Conversely, type s2 was more often found in Portuguese patients (29.7%) than in Colombian patients (7.3%). Type m1 seemed to be more prevalent in Colombian patients (85.4%) than in Portuguese cases (32.9%). Similarly, the cagA-positivity rate was higher among Colombian patients (90.4%) than among Portuguese patients (60.4%). The prevalence of the different iceA genotypes seemed to be similar among the two patient groups.

The prevalence of cases containing multiple vacA or iceA genotypes was much higher among the Portuguese patients than among Colombian cases (P < 0.001). Multiple vacA as well as iceA genotypes were found in 30 (15.6%) of the 192 Portuguese cases, whereas of the Colombian patients, only three (1.6%) of the 178 cases contained multiple genotypes for vacA as well as iceA (P < 0.001).

H. pylori Genotypes and the Density of H. pylori Colonization

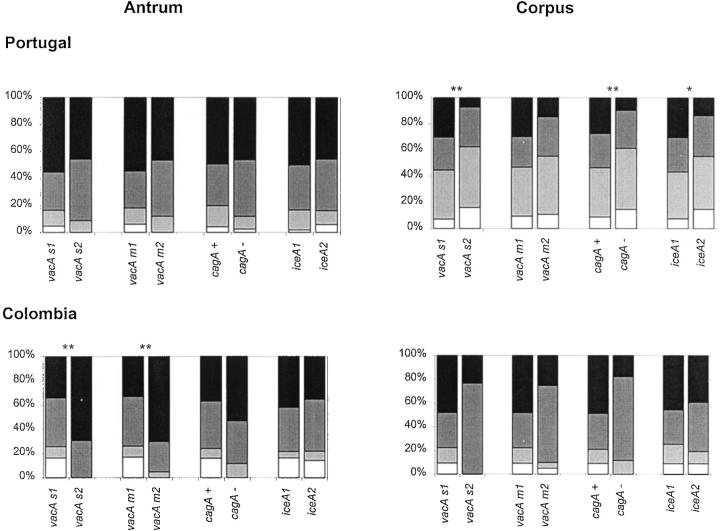

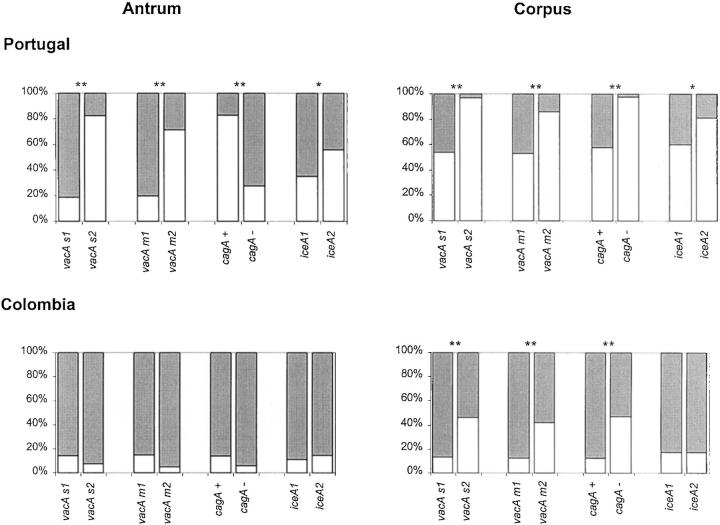

The density of H. pylori was scored in antral and corpus biopsy specimens and the results are shown in Figure 1 ▶ . In Portuguese patients, the average density scores in the antrum were significantly higher than in the corpus (P < 0.001). There also was a significant relationship between the density of H. pylori colonization in the corpus and vacA s1 (P = 0.003), cagA+ (P = 0.008), and iceA1 (P = 0.048) genotypes, but not with the vacA m type. No significant relationships were observed between vacA s or m region, cagA status, or iceA genotypes and the density of H. pylori in the antrum biopsy specimens. In a total of seven (3.6%) antral biopsies no bacteria were observed (density = 0), whereas they were found positive by PCR.

Figure 1.

Density of H. pylori colonization in Portuguese and in Colombian patients, according to the updated Sydney system. White = absent, light gray = rare, dark gray = moderate, black = abundant. Figures at the left show results for antral biopsy specimens, figures at the right show results for corpus biopsy specimens. A single asterisk above a pair of bars marks a significant difference at P < 0.05; double asterisks above a pair of bars marks a significant difference at P < 0.01 (Mann-Whitney test). Only cases containing a single genotype were included in the statistical analysis. Cases containing multiple genotypes were excluded.

Among Colombian patients the average H. pylori density scores in the antrum were lower than in the corpus (P = 0.019). The H. pylori density in the antrum was associated with the vacA s1 (P = 0.006) and m1 (P = 0.001) genotypes, but not with the cagA or iceA status. There were no significant relationships between genotypes and H. pylori density in the corpus. In 26 (14.6%) of the antral biopsies no bacteria were observed (density = 0), whereas they were found positive by PCR.

H. pylori Genotypes and Chronic Inflammation

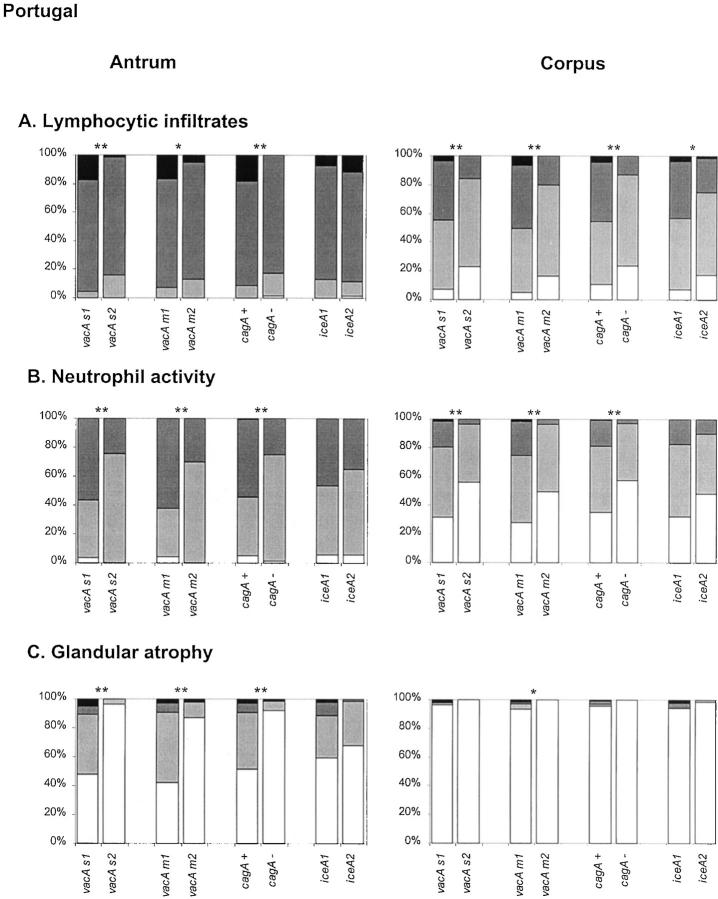

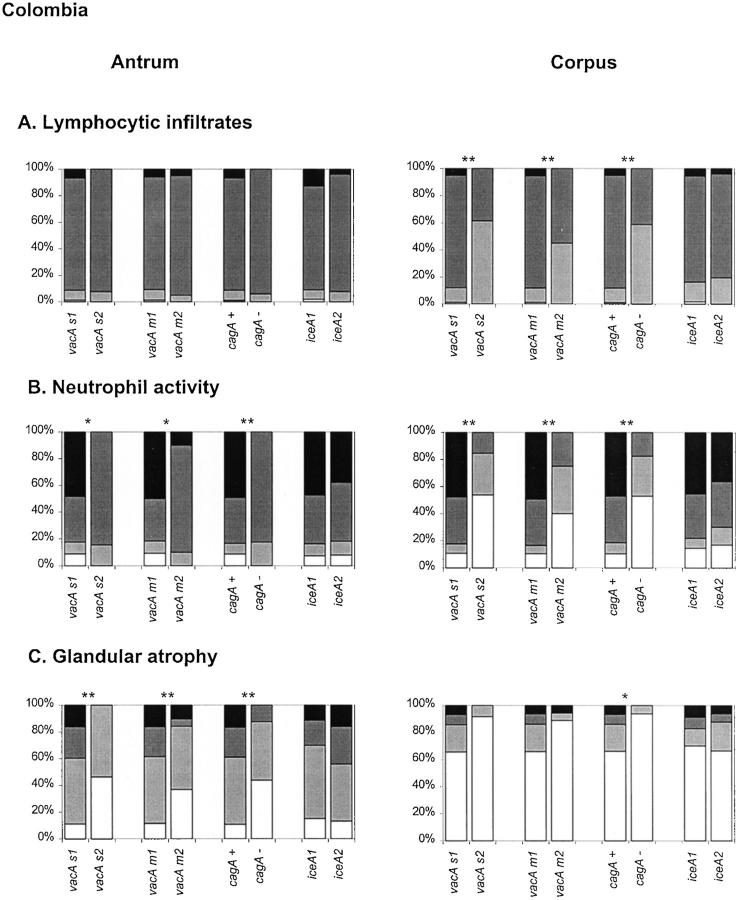

Among the Portuguese patients (Figure 2A) ▶ , there was a significant association between vacA s1, m1, and cagA+ genotypes and higher inflammation scores in both corpus and antrum biopsy specimens. The iceA status was only associated to the degree of inflammation in the corpus. Among Colombian patients (Figure 3A) ▶ , vacA s1, m1, and cagA+ genotypes are associated to higher inflammation scores in the corpus, but not in the antrum. The iceA genotype was not associated to the degree of inflammation.

Figure 2.

Histological parameters determined in gastric biopsy specimens from Portuguese patients, according to the updated Sydney system. Patterns for lymphocytic infiltrates (A), neutrophil activity (B), and glandular atrophy (C) are as follows: white = absent, light gray = mild, dark gray = moderate, black = severe. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. Asterisks are identical to those in Figure 1 ▶ .

Figure 3.

Histological parameters determined in gastric biopsy specimens from Colombian patients, according to the updated Sydney system. Patterns are identical to those in Figure 2 ▶ and asterisks are identical to those in Figure 1 ▶ .

H. pylori Genotypes and Neutrophil Activity

Neutrophilic activity was investigated and results are shown in Figures 2B and 3B ▶ ▶ . In both Portuguese and Colombian patients, vacA s1, vacA m1, and cagA+ genotypes were strongly associated with higher activity in the corpus and in the antrum. The iceA status was not significantly associated with the neutrophil infiltration scores.

H. pylori Genotypes and Glandular Atrophy

Overall, the prevalence of atrophy among the Portuguese patients was lower than among Colombian cases. It should be taken into account that the Colombian patients were selected for presence of atrophy at baseline. Therefore, the association between presence of atrophy and H. pylori genotypes could not be assessed in Colombian patients. Nevertheless, the association between the degree of atrophy and H. pylori genotypes could still be analyzed.

Among the Portuguese patients, the ages were not normally distributed, and patients with atrophic gastritis (45.8 ± 6.8 years) were significantly older than patients with nonatrophic gastritis (42.0 ± 6.6 years) (P < 0.001). There was a strong association between the presence of glandular atrophy in the antrum and the individual vacA s1, m1, and cagA+ genotypes, as compared to the vacA s2, m2, and cagA− genotypes, respectively, but not with the iceA genotype. The odds ratio of vacA s1 versus s2, vacA m1 versus m2, and cagA+ versus cagA− strains for glandular atrophy were 32.21 (95% CI, 7.3 to 141.7), 15.18 (95% CI, 5.7 to 40.3), and 13.12 (95% CI, 4.7 to 36.6), respectively.

For both patient groups, the associations between the H. pylori genotypes and the degree of atrophy were further analyzed, and results are shown in Figures 2C and 3C ▶ ▶ . In both Portuguese and Colombian patients, vacA s1, vacA m1, cagA+ (but not the iceA) genotypes were each strongly correlated with the degree of glandular atrophy in the antrum. In the corpus of the Portuguese patients atrophy was found only in five cases, thus not permitting reliable analyses. In the corpus of Colombian patients, only an association between glandular atrophy and the cagA genotype was found.

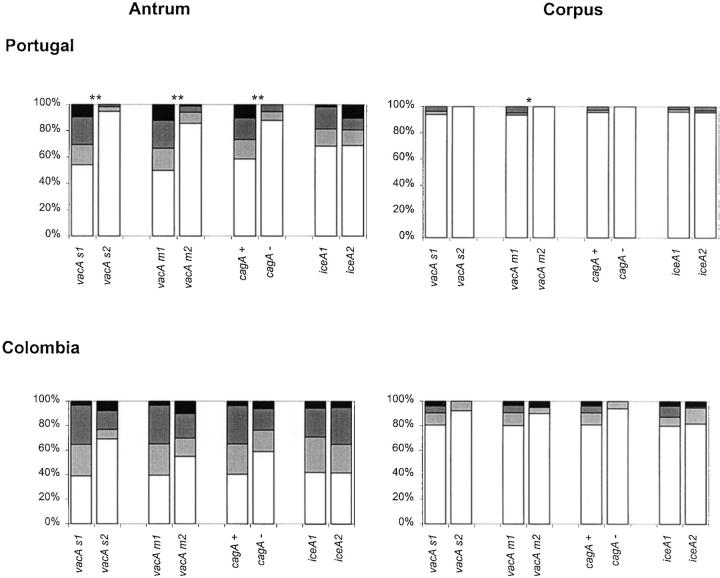

H. pylori Genotypes and Intestinal Metaplasia

Firstly, a highly significant association was observed between the presence of intestinal metaplasia in the antrum and H. pylori genotypes. The prevalence of vacA s1, m1, or cagA+ strains was much higher among patients with intestinal metaplasia than in cases without intestinal metaplasia. Among Portuguese patients, the odds ratios for intestinal metaplasia in the antrum of vacA s1 versus s2, vacA m1 versus m2, and cagA+ versus cagA− strains were 16.2 (95% CI, 4.7 to 56.4), 9.3 (95% CI, 3.7 to 23.4), and 8.1 (95% CI, 3.1 to 21.2), respectively. In the corpus, intestinal metaplasia was observed in only a small number of patients. Among Colombian patients, the presence of metaplasia in the antrum was only significantly associated with the vacA s genotype with and odds ratio of 3.5 (95% CI, 1.0 to 12.0). Presence of metaplasia in the corpus was not associated to any of the genotypes.

Secondly, the association between H. pylori genotypes and the type of intestinal metaplasia is shown in Figure 4 ▶ . There was a strong association between the vacA s1, m1, and cagA+ genotypes and the type of metaplasia in the antrum of the Portuguese patients. In Colombian patients, a similar trend was observed in the antrum, but this failed to reach statistical significance. In the corpus biopsy specimens, there were no significant associations observed, except for the vacA m type in Portuguese patients, although it should be noted that there were only five Portuguese patients with intestinal metaplasia in the corpus.

Figure 4.

Type of intestinal metaplasia in Portuguese and in Colombian patients. White = absent, light gray = complete, dark gray = mixed, black = incomplete. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. Asterisks are identical to those in Figure 1 ▶ .

H. pylori Genotypes and Epithelial Damage

The presence or absence of epithelial damage was assessed and results are shown in Figure 5 ▶ . Presence of vacA s1, vacA m1, and cagA+ genotypes are strongly associated with the presence of epithelial damage in the corpus of both Portuguese and Colombian patients and in the antrum of the Portuguese patients. The iceA status was significantly associated with the presence of epithelial damage in the antrum and corpus of the Portuguese patients.

Figure 5.

Epithelial damage in Portuguese and in Colombian patients. White = absent, light gray = present. Statistical analyses were performed using the chi-square test. Asterisks are identical to those in Figure 1 ▶ .

The association between the presence or absence of atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia and the H. pylori vacA (s and m regions), cagA, or iceA genotypes, was analyzed by means of logistic regression in Portuguese patients. Because the cagA, vacA, and iceA genotypes were strongly associated, each was analyzed individually in separate regression models, correcting for age and gender as possible confounders. Presence of atrophy was associated with vacA s1 (OR, 46.9; 95% CI, 8.6 to 256.4), vacA m1 (OR, 10.1; 95% CI, 4.3 to 23.7), and cagA (OR, 11.2; 95% CI, 4.5 to 27.8), but not with the iceA genotype. Similarly, presence of intestinal metaplasia was associated with vacA s1 (OR, 14.9; 95% CI, 4.2 to 53.2), vacA m1 (OR, 6.8; 95% CI, 2.9 to 15.9), and cagA (OR, 4.8; 95% CI, 2.1 to 10.6), but not with the iceA genotype.

Separate analysis of a subgroup of 77 cagA-negative Portuguese cases revealed that in these patients, vacA s1 genotypes are significantly associated with the presence of atrophy (P = 0.008), the degree of atrophy (P = <0.001), presence of intestinal metaplasia (P = 0.016), the type of intestinal metaplasia (P < 0.001), and epithelial damage (P = 0.024) in the antrum. Similarly, the vacA m1 strains are associated with presence of atrophy (P = 0.003), the degree of atrophy (P < 0.001), the presence of intestinal metaplasia (P = 0.006), and the type of intestinal metaplasia (P = 0.001) in the antrum, but not with the presence of epithelial damage.

Discussion

H. pylori infection causes chronic gastritis and is associated with the development of peptic ulcer disease, gastric carcinoma, and MALT lymphoma. 2,25,26 Although H. pylori infection causes chronic gastritis in virtually all patients, not all individuals develop more severe gastric pathology. Thus, there is a marked discrepancy between the number of individuals colonized and those with clinical symptoms. Although host and environmental factors are considered important, 3 there is also evidence for a role of specific H. pylori virulence-associated genotypes. Patients infected with less virulent genotypes are more likely to have mild gastritis throughout their entire life, whereas patients infected with more virulent genotypes have a higher probability of developing peptic ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis, and eventually gastric carcinoma. Gastric carcinogenesis is a complex, multifactorial process, in which persistent H. pylori infection can play an important role. 26 Prolonged infection may lead to the loss of glands, resulting in multifocal atrophic gastritis, which can be followed by the development of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia. 5 As compared to the general population, patients with duodenal ulcer disease may have a reduced risk for the development of gastric cancer. 27 This finding, as well as other epidemiological observations, 28 suggest the existence of at least two distinct pathways, one resulting in duodenal ulcer disease, and the other associated with gastric ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis, and possibly gastric carcinoma. Atrophy is the first recognizable step in the multifocal atrophic gastritis complex that in more advanced stages may lead to intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia. vacA s- and m-region mosaicism can play an important role in such a chain of events. Several studies have consistently shown that the vacA s genotype is associated with disease in patients from various countries 11,30-33 although others did not confirm these findings. 19 The vacA m region genotype was not significantly associated with peptic ulcer disease. 13 However, the present study revealed the strong significance of the vacA m1 genotype with respect to epithelial damage, neutrophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates, atrophic gastritis, and intestinal metaplasia in patients from two geographically distinct regions. Atherton and colleagues 34 also presented evidence that m1 strains were associated with greater gastric epithelial damage than m2 strains in North American patients. Increased epithelial damage may be explained by a higher level of cytotoxin production by vacA s1/m1 strains as compared to vacA s1/m2 strains. 11 Earlier studies 35 also revealed a significant relationship between the level of cytotoxin production and the severity of atrophy, confirming that the cytotoxin is a disease-associated factor. Because the production of cytotoxin primarily depends on the mosaic structure of the vacA gene, especially of the s and m regions, 11 the association between vacA genotypes and atrophy as presented here, is consistent with these earlier observations. Moreover, the present study showed that vacA and cagA genotypes not only are related to the presence, but also with the degree of atrophy and the type of intestinal metaplasia, suggesting that these genotypes may play an important role in the development of lesions considered as precursors of gastric carcinoma. Our findings that severe damage to the gastric epithelium is associated with vacA s1/m1 mosaicism suggests that such damage represents the primary effect of the cytotoxin 10 and that leukocyte infiltrates and atrophy may be sequential in the cascade that characterizes the precancerous process. Furthermore, the m1 and m2 forms of the VacA cytotoxin may recognize different receptors on human gastric epithelial cells. 36

The iceA genotype, which has been associated with peptic ulcer disease in some populations 17,18 seems to be of limited use in the patient populations studied here. iceA1 was significantly associated to the degree of lymphocyte infiltrates and epithelial damage in Portuguese patients, but not with neutrophil activity, atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia. Therefore, the clinical relevance of iceA remains to be studied in more detail in patients from different geographic origins.

Several genes of the cag pathogenicity island encode proteins that enhance the virulence of the strain, eg, by increasing the production of interleukin-8 by gastric epithelial cells, 37 causing infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, resulting in more severe inflammatory activity of the gastric epithelium. The present study showed that the great majority of patients have lymphocytic infiltrates in the corpus and antrum but neutrophil activity is found less frequently, and is strongly associated with vacA-s1, vacA-m1, and cagA+ genotypes. Several European and North American studies have shown that infection withcagA-positive H. pylori strains also increases the risk for atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer. 15,38 However, several studies in Asian populations did not confirm these relationships, 39 indicating that there are important geographic differences. In general, the incidence of H. pylori-associated diseases, such as gastric cancer is not uniformly distributed over the globe and does not parallel the prevalence of H. pylori infection. The highest incidence of gastric cancer is found in East Asia (Japan and Korea), and in Central America and South America (especially the Andean countries). 40 Within Europe, the highest incidence is found in Portugal, Austria, Italy, and Spain. 41 In contrast, high prevalence of infection is reported from such areas with low gastric cancer risk, such as Africa, 42 India, and the coastal regions of Latin America. 43

We and others have recently shown that the vacA and cagA genotypes of H. pylori are not equally distributed over the world. 19,20,44-46 There are significant differences between patient populations from Asia, different parts of Europe, and North and South America. Given the geographic distribution of specific H. pylori genotypes, it could be speculated that there might be an epidemiological relationship with the incidence of gastric cancer. The present study confirmed earlier findings in Portuguese patients showing that a high proportion are infected with multiple H. pylori strains. 44,47

With respect to age, gender, distribution of genotypes, as well as the prevalence of atrophy, there were significant differences between the Portuguese and Colombian patients, reflecting the different strategy used for selection of these cases. However, despite these differences, the highly similar relationships between bacterial genotypes and histopathological findings in both populations indicate that our observations are accurate and reliable.

Our study has several limitations. The biopsy specimens from each patient group were analyzed by two different pathologists, although they used the same scoring system. 21 Also, only biopsies from the antrum of the stomach were used for genotyping analysis in each patient, and the influence of sampling errors cannot be excluded. Therefore, there may not be an absolute concordance between the genotype of the colonizing strain and underlying pathological observations in the corpus, because patients may carry different strains in the antrum and corpus. However, the antrum is the predominant site of H. pylori colonization 48 and the chance of false-negative results is lower than in corpus biopsies. 49

Furthermore, other possibly relevant factors, such as smoking, acid output, HLA-status, and other bacterial virulence factors were not studied. Despite the limitations of the present study, analysis of the vacA, cagA, and iceA virulence-associated genes directly in gastric biopsies permitted clinically relevant discrimination between H. pylori strains.

In conclusion, distinct H. pylori genotypes seem to be associated to the outcome of the infection and may have important clinical and epidemiological implications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Els Stet and Nathalie Nouhan for preparation of the LiPA strips; and Profs. M. Sobrinho-Simões, L. David, M. Cardoso de Oliveira, and L. Tomé Ribeiro for their support.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to L. J. van Doorn, Delft Diagnostic Laboratory, R. de Graafweg 7, 2625 AD, Delft, the Netherlands. E-mail: l.j.van.doorn@ddl.nl.

Supported by a grant from the Luso-American Foundation (FLAD, project number 492/97); the PRAXIS XXI program from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (to C. F. and C. N.); and the Colombian work was supported by grant P01-CA-28842 of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, United States Public Health Service. Part of the biopsies of the Portuguese patients were obtained under a protocol established between ARS-Norte, Estaleiros Navais de Viana do Castelo, Hospital de S. João and IPATIMUP.

C. G. and C. F. contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Blaser MJ: Ecology of Helicobacter pylori in the human stomach. J Clin Invest 1997, 100:759-762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn BE, Cohen H, Blaser MJ: Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997, 10:720-741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azuma T, Ito S, Sato F, Yamazaki Y, Miyaji H, Ito Y, Suto H, Kuriyama M, Kato T, Kohli Y: The role of the HLA-DQA1 gene in resistance to atrophic gastritis and gastric adenocarcinoma induced by Helicobacter pylori infection. Cancer 1998, 82:1013-1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correa P: Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 1995, 19 Suppl 1:S37-S43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correa P: Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process—First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res 1992, 52:6735-6740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varis K, Taylor PR, Sipponen P, Samloff IM, Heinonen OP, Albanes D, Harkonen M, Huttunen JK, Laxen F, Virtamo J: Gastric cancer and premalignant lesions in atrophic gastritis: a controlled trial on the effect of supplementation with alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene. The Helsinki Gastritis Study Group. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998, 33:294-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go MF, Kapur V, Graham DY, Musser JM: Population genetic analysis of Helicobacter pylori by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis: extensive allelic diversity and recombinational population structure. J Bacteriol 1996, 178:3934-3938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Achtman M, Azuma T, Berg DE, Ito Y, Morelli G, Pan ZJ, Suerbaum S, Thompson SA, van der Ende A, van Doorn LJ: Recombination and clonal groupings within Helicobacter pylori from different geographic regions. Mol Microbiol 1999, 32:459-470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cover TL: The vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol 1996, 20:241-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leunk RD: Production of a cytotoxin by Helicobacter pylori. Rev Infect Dis 1995, 13:S686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atherton JC, Cao P, Peek RMJ, Tummuru MK, Blaser MJ, Cover TL: Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:17771-17777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Sanna R, Pena AS, Midolo P, Ng EK, Atherton JC, Blaser MJ, Quint W: Expanding allelic diversity of Helicobacter pylori vacA. J Clin Microbiol 1998, 36:2597-2603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atherton JC: The clinical relevance of strain types of Helicobacter pylori. Gut 1997, 40:701-703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree JE, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A: cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:14648-14653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, Cover TL, Peek RM, Chyou PH, Stemmermann GN, Nomura A: Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res 1995, 55:2111-2115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuipers EJ, Perez-Perez GI, Meuwissen SG, Blaser MJ: Helicobacter pylori and atrophic gastritis: importance of the cagA status. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995, 87:1777-1780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peek RM, Thompson SA, Donahue JP, Tham KT, Atherton JC, Blaser MJ, Miller GG: Adherence to gastric epithelial cells induces expression of a Helicobacter pylori gene, iceA, that is associated with clinical outcome. Proc Amer Assoc Phys 1998, 110:531-544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Sanna R, Plaisier A, Schneeberger P, de Boer WA, Quint W: Clinical relevance of the cagA, vacA, and iceA status of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 1998, 115:58-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Gutierrez O, Kim JG, Kashima K, Graham DY: Relationship between Helicobacter pylori iceA, cagA, and vacA status and clinical outcome: studies in four different countries. J Clin Microbiol 1999, 37:2274-2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukhopadhyay AK, Kersulyte D, Jeong JY, Datta S, Ito Y, Chowdhury A, Chowdhury S, Santra A, Bhattacharya SK, Azuma T, Nair GB, Berg DE: Distinctiveness of genotypes of Helicobacter pylori in Calcutta, India. J Bacteriol 2000, 182:3219-3227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P: Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. Am J Surg Pathol 1996, 20:1161-1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boom R, Sol CJ, Salimans MM, Jansen CL, Wertheim-vanDillen PM, van der Noordaa J: Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol 1990, 28:495-503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Rossau R, Jannes G, van Asbroeck M, Sousa JC, Carneiro F, Quint W: Typing of the Helicobacter pylori vacA gene and detection of the cagA gene by PCR and reverse hybridization. J Clin Microbiol 1998, 36:1271-1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figueiredo C, Quint WGV, Sanna R, Sablon E, Donahue JP, Xu Q, Miller GG, Peek RMJ, Blaser MJ, van Doorn LJ: Genetic organisation and heterogeneity of the iceA locus of Helicobacter pylori. Gene 2000, 246:59-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wotherspoon AC: Gastric MALT lymphoma and Helicobacter pylori. Yale J Biol Med 1997, 69:61-68 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham DY: Helicobacter pylori infection is the primary cause of gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol 2000, 35:90-97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansson LE, Nyren O, Hsing AW, Bergstrom R, Josefsson S, Chow WH, Fraumeni JFJ, Adami HO: The risk of stomach cancer in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer disease. N Engl J Med 1996, 335:242-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Correa P: A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 1988, 48:3554-3560 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deleted in proof.

- 30.Gunn MC, Stephens JC, Stewart JA, Rathbone BJ, West KP: The significance of cagA and vacA subtypes of Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of inflammation and peptic ulceration. J Clin Pathol 1998, 51:761-764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hennig EE, Trzeciak L, Regula J, Butruk E, Ostrowsky J: vacA genotyping directly from gastric biopsy specimens and estimation of mixed Helicobacter pylori infections in patients with duodenal ulcer and gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999, 34:743-749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kidd M, Lastovica AJ, Atherton JC, Louw JA: Heterogeneity in the Helicobacter pylori vacA and cagA genes: association with gastroduodenal disease in South Africa? Gut 1999, 45:499-502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans DG, Queiroz DM, Mendes EN, Evans DJ, Jr: Helicobacter pylori cagA status and s and m alleles of vacA in isolates from individuals with a variety of H. pylori-associated gastric diseases. J Clin Microbiol 1998, 36:3435-3437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atherton JC, Peek RMJ, Tham KT, Cover TL, Blaser MJ: Clinical and pathological importance of heterogeneity in vac A, the vacuolating cytotoxin gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 1997, 112:92-99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox JG, Correa P, Taylor NS, Thompson N, Fontham E, Janney F, Sobhan M, Ruiz B, Hunter FM: High prevalence and persistence of cytotoxin-positive Helicobacter pylori strains in a population with high prevalence of atrophic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol 1992, 87:1554-1560 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagliaccia C, de Bernard M, Lupetti P, Ji X, Burroni D, Cover TL, Papini E, Rappuoli R, Telford J, Reyrat JM: The m2 form of the Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin has cell type-specific vacuolating activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:10212-10217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimoyama T, Crabtree JE: Mucosal chemokines in Helicobacter pylori infection. J Physiol Pharmacol 1997, 48:315-323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cover TL, Glupczynski Y, Lage AP, Burette A, Tummuru MK, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ: Serologic detection of infection with cagA+ Helicobacter pylori strains. J Clin Microbiol 1995, 33:1496-1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maeda S, Ogura K, Yoshida H, Kanai F, Ikenoue T, Kato N, Shiratori Y, Omata M: Major virulence factors, VacA and CagA, are commonly positive in Helicobacter pylori isolates in Japan. Gut 1998, 42:338-343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forman D: Helicobacter pylori infection and cancer. Br Med Bull 1998, 54:71-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Black RJ, Bray F, Ferlay J, Parkin DM: Cancer incidence and mortality in the European Union: cancer registry data and estimates of national incidence for 1990. Eur J Cancer 1997:33:1075–1107 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Holcombe C: Helicobacter pylori: the African enigma. Gut 1992, 33:429-431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sierra R, Munoz N, Pena AS, Biemond I, van Duijn W, Lamers CB, Teuchmann S, Hernandez S, Correa P: Antibodies to Helicobacter pylori and pepsinogen levels in children from Costa Rica: comparison of two areas with different risks for stomach cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1992, 1:449-454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Mégraud F, Pena AS, Midolo P, Queiroz DM, Carneiro F, Vandenborght B, Pégado MGF, Sanna R, de Boer WA, Schneeberger P, Correa P, Ng EK, Atherton JC, Blaser MJ, Quint WGV: Geographic distribution of vacA allelic types of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 1999, 116:823-830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kersulyte D, Mukhopadhyay AK, Velapatino B, Su W, Pan Z, Garcia C, Hernandez V, Valdez Y, Mistry RS, Gilman RH, Yuan Y, Gao H, Alarcon T, Lopez-Brea M, Balakrish NG, Chowdhury A, Datta S, Shirai M, Nakazawa T, Ally R, Segal I, Wong BC, Lam SK, Olfat FO, Boren T, Engstrand L: Differences in genotypes of Helicobacter pylori from different human populations. J Bacteriol 2000, 182:3210-3218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Doorn LJ, Figueiredo C, Sanna R, Blaser MJ, Quint WGV: Distinct variants of Helicobacter pylori cagA are associated with vacA subtypes. J Clin Microbiol 1999, 37:2306-2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Figueiredo C, van Doorn LJ, Nogueira C, Soares J, Pinho C, Figueira P, Quint WGV, Carneiro F: Helicobacter pylori genotypes are associated with clinical outcome in Portuguese patients and reveal a high prevalence of infections with multiple strains. Scand J Gastroenterol (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Misra V, Misra S, Dwevedi M, Singh UP, Bhargava V, Gupta SC: A topographic study of Helicobacter pylori density, distribution and associated gastritis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000, 15:737-743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Genta RM, Graham DY: Comparison of biopsy sites for the histopathologic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: a topographic study of H. pylori density and distribution. Gastrointest Endosc 1994, 40:342-345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]