Abstract

The regulatory peptide gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) may play a role in human cancer as a stimulatory growth factor. To understand the potential role of GRP in human breast cancer, we have evaluated GRP receptor expression in human non-neoplastic and neoplastic breast tissues and in axillary lymph node metastases, using in vitro receptor autoradiography on tissue sections with [125I]Tyr4-bombesin and with [125I]d-Tyr6, β Ala11, Phe13, Nle14-bombesin(6–14) as radioligands. GRP receptors were detected, often in high density, in neoplastic epithelial mammary cells in 29 of 46 invasive ductal carcinomas, in 11 of 17 ductal carcinomas in situ, in 1 of 4 invasive lobular carcinomas, in 1 of 2 lobular carcinomas in situ, and in 1 mucinous and 1 tubular carcinoma. A heterogeneous GRP receptor distribution was found in the neoplastic tissue samples in 32 of 52 cases with invasive carcinoma and 12 of 19 cases with carcinoma in situ. The lymph node metastases (n = 33) from those primary carcinomas expressing GRP receptors were all positive, whereas surrounding lymphoreticular tissue was negative. GRP receptors were also present in high density but with heterogeneous distribution in ducts and lobules from all available breast tissue samples (n = 23). All of the receptors corresponded to the GRP receptor subtype of bombesin receptors, having high affinity for GRP and bombesin and lower affinity for neuromedin B. All tissues expressing GRP receptors were identified similarly with both radioligands. These data describe not only a high percentage of GRP receptor-positive neoplastic breast tissues but also for the first time a ubiquitous GRP receptor expression in nonneoplastic human breast tissue. Apart from suggesting a role of GRP in breast physiology, these data represent the molecular basis for potential clinical applications of GRP analogs such as GRP receptor scintigraphy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy.

Human neoplasias can sometimes express receptors for peptide hormones similar to those found in their respective physiological targets, such as brain, gastrointestinal tract, or endocrine or immune system. For instance, receptors for somatostatin, 1 vasoactive intestinal peptide, 2 gastrin, 3 and GRP 4 have been recently identified in vitro in various types of human cancers. Clinical implications of some of these in vitro observations have been formulated and have led to the development of radiolabeled peptides for in vivo receptor scintigraphy 5-7 or radiotherapy 8 in tumor patients. Further, peptides linked to cytotoxic drugs 9 or stable peptide agonists or antagonists 10 have been used for long-term targeted chemotherapy in tumor models.

Bombesin-like peptides include the amphibian peptide bombesin as well as the mammalian counterparts GRP and neuromedin B. 11 These peptides have been shown to be mitogenic, causing growth of 3T3 murine fibroblasts 12 and normal bronchial epithelial cells 13 in culture. They have been implicated in the development of the fetal lung 14 and of diseases of the lung. 15 Small-cell lung carcinoma cell lines produce and secrete GRP and express high affinity receptors for bombesin-like peptides, thus establishing an autocrine growth loop, involved in the abnormal growth of these tumors, 16 as established also for several polypeptide growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-α and insulin-like growth factor. 17

Likewise, GRP and bombesin may control growth in breast cancer cells as well. 18 For instance, bombesin stimulates early signal transduction mechanisms (eg, activation of inositol phospholipid signaling and Ca2+ efflux) in human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. 19 Human breast cancer cell lines were shown to bear GRP receptors by competitive binding of bombesin-like peptides. 20

GRP mediates its action through specific membrane-bound receptors. The receptors correspond to one of the subtypes of the bombesin-like peptide receptors, namely the GRP receptor, which is characterized by high-affinity binding for GRP and bombesin and only moderate binding for neuromedin B. These receptors are members of the large superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors with seven transmembrane domains. If GRP receptors, as stated above, mediate the mitogenic action of GRP and bombesin-like peptides in neoplasias, the information about the presence of GRP receptors in primary human tumors is crucial for the understanding of GRP action in this tissue. Moreover, to evaluate the potential clinical implications of GRP and GRP receptor in patients with cancer, it is mandatory to know the incidence and the density of GRP receptors in human primary carcinoma tissue. The method of choice is in vitro receptor autoradiography performed on tissue sections, 21 which allows localization in situ with high sensitivity of peptide receptors in tumor samples obtained after surgical resection. Such complex and heterogeneous tissue may contain, in addition to carcinoma tissue, contaminating tissues from the involved organs, vessels, nerves, and immune cells and needs to be analyzed morphologically. This in situ method, in comparison with methods using tissue homogenates, 22 allows the distinguishing of the receptor expression in non-neoplastic tissue and of its malignant counterparts in each individual tissue sample.

The aim of this study was to evaluate, with in vitro receptor autoradiography on tissue sections, using [125I]Tyr4-bombesin, as well as [125I]d-Tyr6, β Ala11, Phe13, Nle14-bombesin(6–14) 23,24 as radioligands, the incidence and the density of GRP receptors in breast carcinoma samples containing various stages of neoplastic transformation as well as non-neoplastic breast.

Materials and Methods

Patient Tissues

Breast tissue samples with primary breast neoplasias were obtained from 56 patients, aged 36 to 84, who were operated on in several institutions. Tissue samples were kept frozen at −80°C. Table 1 ▶ lists the histopathological types of the investigated breast carcinomas. The diagnosis was reviewed and formulated by use of cryostat sections, according to the WHO guidelines stated by Tavassoli. 25 Of 56 patients, 46 (82%) showed an invasive ductal carcinoma, representing almost the natural incidence of this carcinoma type. 25 Histological evaluation identified 23 cases with intermediate (G2), 18 cases with low (G1), and 5 cases with high (G3) grade, according to a modified Bloom-Richardson grading method. 25 There were four invasive lobular carcinomas and four ductal carcinomas in situ, as well as one tubular and one mucinous carcinoma. Of the tissue samples with invasive ductal carcinoma, 13 contained concomitant ductal carcinoma in situ, and 2 with invasive lobular carcinoma contained concomitant lobular carcinoma in situ. In 7 patients, we could investigate tissue samples obtained from the primary tumor and from all its axillary metastases; carcinoma type, age, tumor size, and progesterone and estrogen receptor status at the time of diagnosis are listed below. We investigated the non-neoplastic breast tissue adjacent to carcinoma tissue in 22 tissue samples and the breast tissue sample of a patient operated on for suspicion of carcinoma but with a final diagnosis of breast fibrosis. Those breast tissues were all found to be histopathologically inconspicuous.

Table 1.

Incidence and Distribution of GRP-R in Primary Breast Carcinomas

| Histopathological types | n* | GRP receptors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Tissue distribution | ||

| Invasive carcinomas | |||

| IDC | 46 | 29 /46 | Heterogeneous 16/29 |

| ILC | 4 | 1 /4 | Heterogeneous |

| Tubular carcinoma | 1 | 1 /1 | Homogeneous |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 1 | 1 /1 | Heterogeneous |

| Subtotal | 52 | 32 /52 | Heterogeneous 18/32 |

| Carcinomas in situ | |||

| DCIS | |||

| Alone | 4 | 2 /4 | Heterogeneous 2/2 |

| Concomitant with IDC | 13 | 9 /13 | Heterogeneous 6/9 |

| LCIS concomitant with ILC | 2 | 1 /2 | Homogeneous |

| Subtotal | 19 | 12 /19 | Heterogeneous 8/12 |

| Total of tested neoplasias | 71 | 44 /71 (62%) | Heterogeneous 26/44 (59%) |

IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; ILC, invasive lobular carcinoma; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ.

* n, Number of neoplasias; tissues with concomitant carcinomas and carcinomas in situ in the same patient were listed separately.

GRP Receptor Autoradiography

Twenty-μm-thick cryostat sections of the tissue samples were processed for GRP receptor autoradiography as described in detail previously for other peptide receptors. 26 One radioligand used was [125I]Tyr4-bombesin, known to specifically label GRP receptors. 4,27 The other radioligand used was [125I]d-Tyr6, β Ala11, Phe13, Nle14-bombesin(6–14) known to label all four bombesin receptor subtypes. 23,24 For autoradiography, tissue sections were mounted on precleaned microscope slides and stored at −20°C for at least 3 days to improve adhesion of the tissue to the slide. Sections were then processed according to Vigna et al. 27 They were first preincubated in 10 mmol/L N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′−2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.4, for 5 minutes at room temperature. They were then incubated in 10 mmol/L N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′−2-ethanesulfonic acid, 130 mmol/L NaCl, 4.7 mmol/L KCl, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethylether)-N-N′-tetraacetic acid, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 100 μg/ml bacitracin (pH 7.4), and approximately 100 pmol/L [125I]Tyr4-bombesin (2000 Ci/mmol; Anawa, Wangen, Switzerland) in the presence or absence of 10−6 mol/L bombesin for 1 hour at room temperature. Additional sections were incubated in the presence of increasing amounts of nonradioactive bombesin, GRP, neuromedin B, or somatostatin to generate competitive inhibition curves. After incubation, the sections were washed four times for 2 minutes each in 10 mmol/L N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′−2-ethanesulfonic acid with 0. 1% bovine serum albumin (pH 7.4) at 4°C. Finally, the slides were rinsed twice for 5 seconds each at 4°C in distilled water. The slides were then dried at 4°C under a stream of cold air. The slides were placed in apposition to 3H-Hyperfilms (Amersham, Aylesbury, UK) and exposed for 4 to 7 days to X-ray cassettes. All cases tested with [125I]Tyr4-bombesin were also evaluated with [125I]d-Tyr6, β Ala11, Phe13, Nle14-bombesin(6–14) as ligand, using the same methodology, except that 20 pmol/L of this radioligand (2000 Ci/mmol; Anawa, Wangen, Switzerland) was given in the incubation solution.

The autoradiograms were quantified using a computer-assisted image processing system, as described previously. 4,26 Tissue standards for iodinated compounds (Amersham) were used for this purpose. A tissue was defined as receptor-positive when the optical density measured in the total binding section was at least twice that of the nonspecific binding section (in the presence of 10−6 mol/L bombesin).

Results

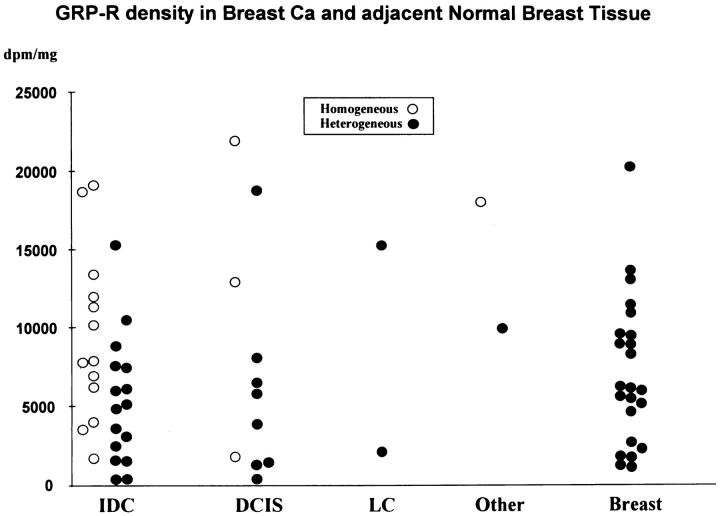

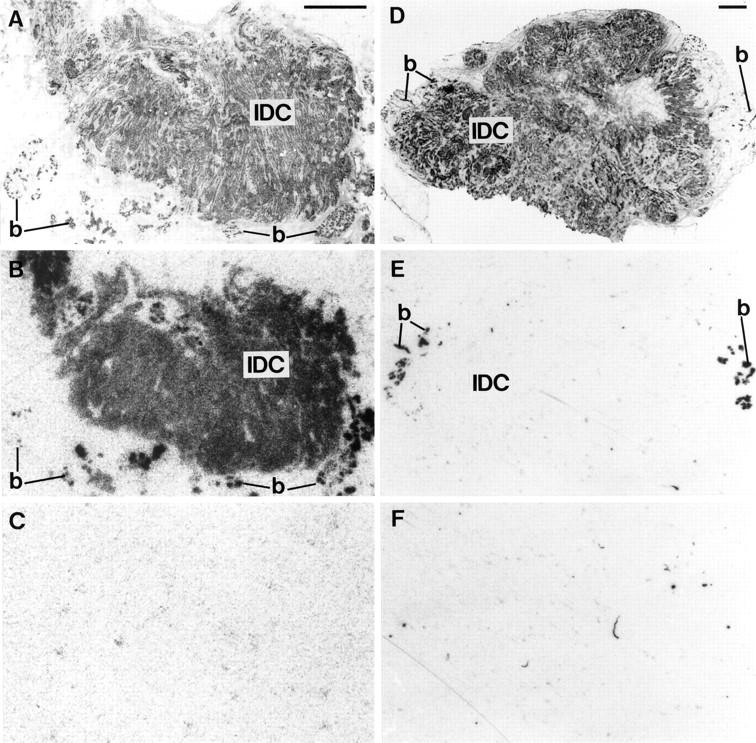

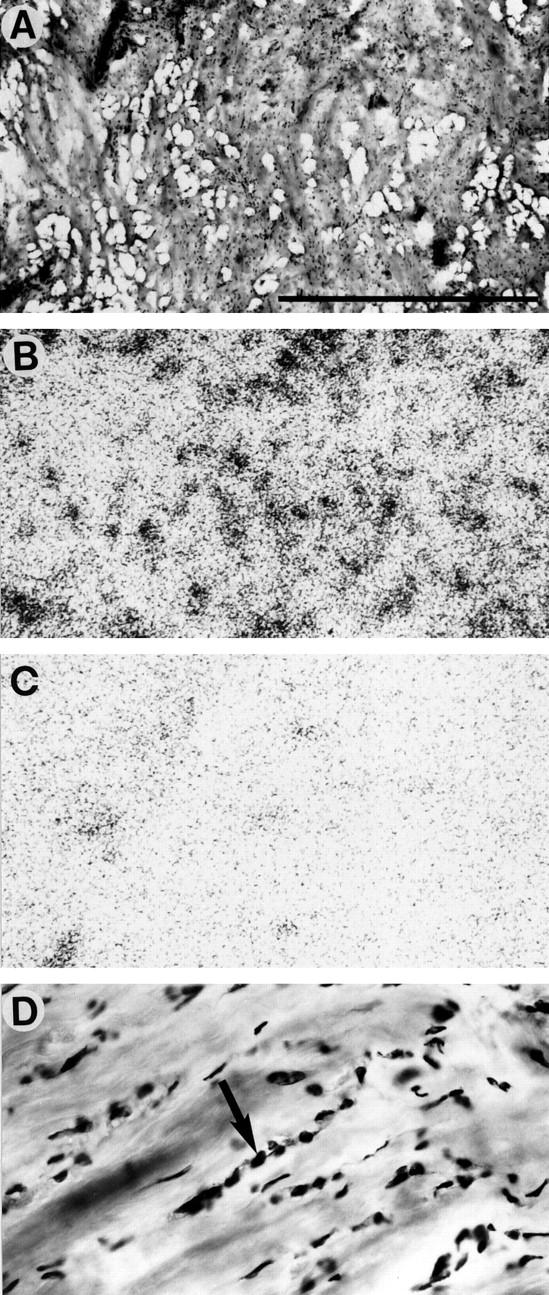

Table 1 ▶ summarizes the GRP receptor incidence in breast carcinoma tissue. GRP receptors were expressed in a total of 29 of the 46 invasive ductal carcinomas. Furthermore, there was a limited number of tested cases of invasive lobular carcinoma and tubular and mucinous carcinomas, also often expressing GRP receptors (Table 1) ▶ . Finally, carcinomas in situ, both ductal and lobular, expressed GRP receptors in 12 of 19 cases. The receptor distribution in the tumor samples was heterogeneous in more than half of the cases. As shown in Figure 1 ▶ , the density of the receptors varied very much from one case to another and encompassed low (417 dpm/mg of tissue) to very high (19,126 dpm/mg of tissue) values. Even within a single tumor, large variations of GRP receptor density were observed in different areas. Figure 1 ▶ also compares the GRP receptor density values of the tumors with that of non-neoplastic breast tissues (n = 23), most of them adjacent to the tumor tissue samples, and illustrates the same broad range of density levels in both tissues. Interestingly, non-neoplastic breast tissues showed, without exception, a heterogeneous distribution of the GRP receptors. Figure 2 ▶ illustrates two typical cases of invasive ductal carcinoma samples, one receptor-positive (Figure 2, A–C) ▶ and one receptor-negative (Figure 2, D–F) ▶ , both, however, with receptor-positive adjacent breast tissue. Figure 3 ▶ shows a GRP receptor-positive invasive lobular carcinoma sample, with the tumor distributed diffusely in the breast stroma, showing characteristic lines of a few carcinoma cells between collagenous fibers, so called Indian files (Figure 3D) ▶ . This typical distribution of tumor cells is also reflected in the radioactivity pattern of the autoradiogram (Figure 3B) ▶ as small dots. The apparent lower receptor density in this lobular carcinoma may be due partly to the lower tumor cellularity that is frequent in this type of tumor.

Figure 1.

GRP receptor density (dpm/mg of tissue) in breast carcinomas and adjacent normal breast tissue, using [125I]Tyr4-bombesin as radioligand. IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; LC, lobular invasive and in situ carcinoma; Other, mucinous and tubular carcinoma. The GRP receptor density encompasses low (417 dpm/mg) to very high (21,940 dpm/mg) values for carcinomas (IDC, DCIS, LC, and Other) and moderate (1144 dpm/mg) to very high (20,282 dpm/mg) values for the adjacent normal breast tissue (Breast), which shows without exception a heterogeneous distribution.

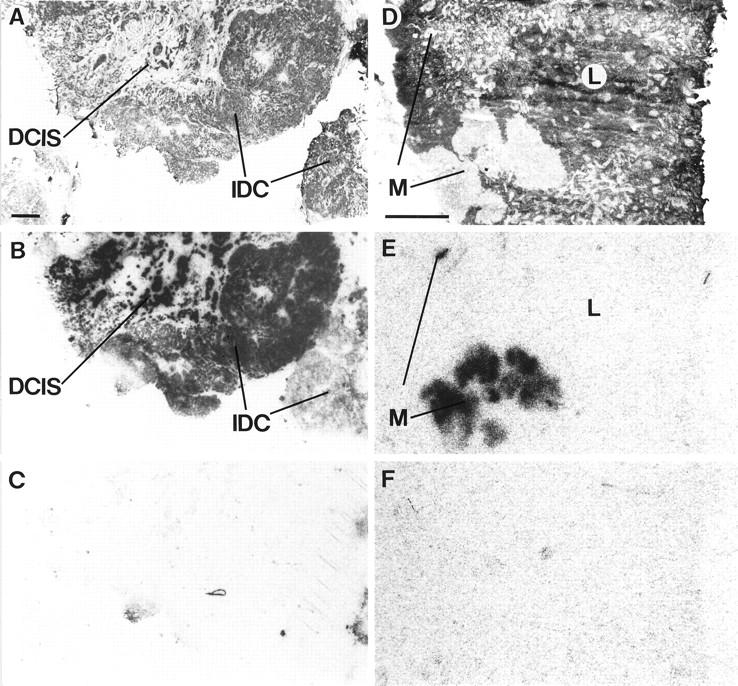

Figure 2.

GRP receptors in two examples of invasive ductal carcinomas, containing adjacent normal human breast tissue. A: H&E-stained section. IDC, Invasive ductal carcinoma; b, normal breast tissue.Scale bar = 1 mm. B: Autoradiogram showing total binding of [125I]Tyr4-bombesin. There is strong and homogeneous labeling of the carcinoma (IDC). Normal breast tissue (b) is also strongly but heterogeneously labeled. C: Autoradiogram showing nonspecific binding of [125I]Tyr4-bombesin (in the presence of 10−6 mol/L bombesin). D: H&E-stained section. IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; b, normal breast tissue. Scale bar = 1 mm. E: Autoradiogram with completely negative carcinoma tissue. b, normal breast tissue. F: Autoradiogram showing nonspecific binding of [125I]Tyr4-bombesin (in the presence of 10−6 mol/L bombesin).

Figure 3.

GRP receptors in an invasive lobular carcinoma. A: H&E-stained section. Invasive lobular carcinoma is arranged in many Indian files. Scale bar = 1 mm. B: Autoradiogram showing total binding of [125I]Tyr4-bombesin. Diffusely and moderately labeled dots and lines represent the receptor-positive Indian files of the carcinoma tissue. C: Autoradiogram showing nonspecific binding. D: Detail of A at high magnification, showing carcinoma cells lined up in an Indian file-pattern (arrow).

Carcinomas in situ often expressed GRP receptor: 11 of 17 ductal carcinomas in situ and 1 of 2 lobular carcinomas in situ were positive (Table 1 ▶ , Figure 1 ▶ ). In the present series, 15 of the samples contained concomitant carcinomas and carcinomas in situ (13 invasive ductal and 2 invasive lobular). In most cases, the GRP receptor expression was comparable in both carcinoma and carcinoma in situ (11 invasive ductal and 1 invasive lobular).

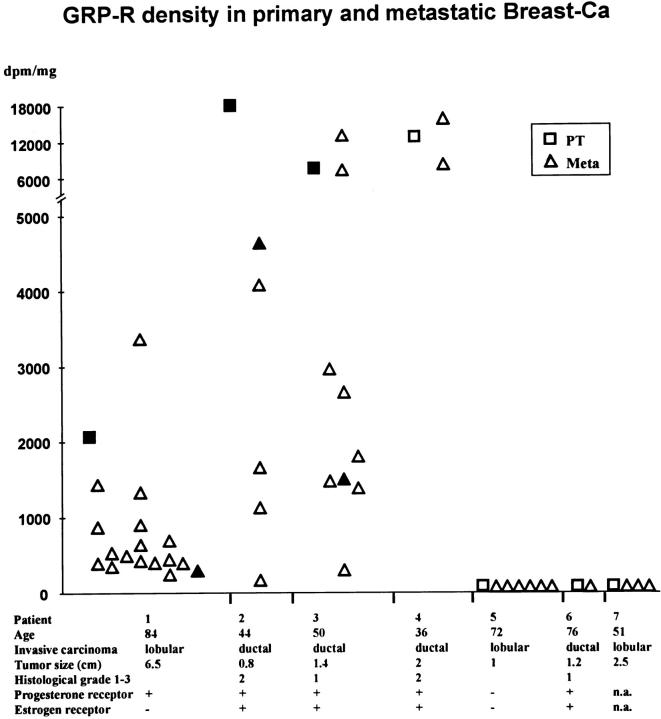

In seven patients with metastatic breast cancer, we have investigated the tissue samples containing the primary tumor and all of its axillary metastases. The summarized clinical data, including patient age, carcinoma type, tumor size, and steroid receptor status, show these patients to be a representative group with invasive mammary carcinomas. Figure 4 ▶ depicts that four of the seven primaries were GRP receptor-positive and that metastases of receptor-positive primary carcinomas were all positive, with usually a comparable range in GRP receptor density levels in primary tumors and in metastases. Most of these metastases had a homogeneous GRP receptor distribution, even those arising from heterogeneously positive primary carcinomas. In this series, GRP receptor-negative primary carcinomas had only receptor-negative metastases. Figure 5 ▶ illustrates a case with a GRP receptor-positive primary tumor and a positive axillary metastasis of the same patient. The primary tumor represents an example of a GRP receptor-positive invasive ductal carcinoma next to a receptor-positive ductal carcinoma in situ, as reported above. The lymph node metastasis is homogeneously positive, with receptor-negative adjacent lymphatic tissue.

Figure 4.

GRP receptor density (dpm/mg of tissue) in primary breast carcinomas and corresponding axillary metastases of seven patients, using [125I]Tyr4-bombesin. Primary tumor is with either homogeneous (□) or heterogeneous (▪) GRP receptor distribution. Axillary metastases are with either homogeneous (▵) or heterogeneous (▴) GRP receptor distribution.

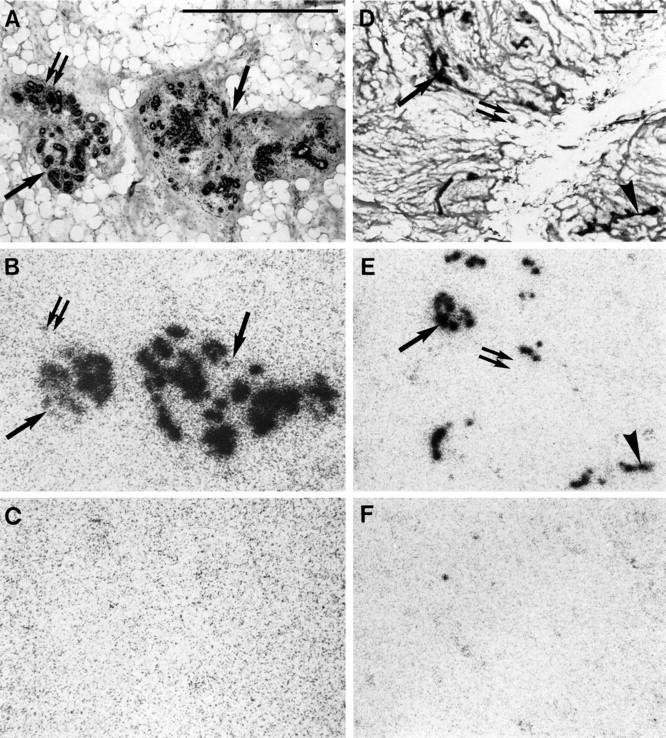

Figure 5.

High density (dpm/mg of tissue) of GRP receptors in an invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) adjacent to carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (A–C) and a GRP receptor-positive axillary lymph node metastasis (D–F) from the same patient. A: H&E-stained section.Scale bar = 1 mm. B: Autoradiogram showing total binding of [125I]Tyr4-bombesin. The carcinoma (IDC) labels strongly and homogeneously with the exception of the part in the lower right. The carcinoma in situ (DCIS) shows a strong and homogeneous labeling throughout the sample. C: Autoradiogram showing nonspecific binding. D: H&E-stained section. L, Lymphoreticular tissue; M, carcinoma metastasis. Scale bar = 1 mm. E: Autoradiogram showing total binding of [125I]Tyr4-bombesin. Shown is strong labeling of the metastasis but completely negative lymphoreticular tissue. F: Autoradiogram showing nonspecific binding.

We have also investigated non-neoplastic breast tissues (n = 23), which have been found to be GRP receptor-positive without exception (Figure 6A ▶ , cancer-bearing breast; and Figure 6D ▶ , non-cancer-bearing breast). The receptor distribution was ubiquitously heterogeneous with lobules and ducts strongly GRP receptor-positive while others were completely negative (Figure 6) ▶ . The number of the identified receptor-positive ducts and lobules varied between 20% and more than 80% of the total number detected in a section, based on estimates by visual inspection. The range of density values of the positive tissues varied from moderate (1144 dpm/mg of tissue) to very high (20,282 dpm/mg of tissue) values (Figure 1) ▶ . The presence of GRP receptors in the non-neoplastic breast did not correlate with the degree of GRP receptor expression of the adjacent carcinoma (Figure 2) ▶ or with the distance of the investigated breast tissue from the carcinoma tissue.

Figure 6.

High density (dpm/mg of tissue) of GRP receptors in normal breast tissue in a cancer-bearing (A–C) or normal (D–F) breast. A: H&E-stained section, showing terminal duct-lobular unit (arrows and double arrow). Scale bar = 1 mm. B: Autoradiogram showing total binding of [125I]Tyr4-bombesin. Epithelial cells of the terminal duct-lobular unit label strongly in most (arrow) but not all (double arrow) parts. C: Autoradiogram showing nonspecific binding. D: H&E-stained section, showing lobules (arrow and double arrow) and subsegmental duct (arrowhead). Scale bar = 1 mm. E: Autoradiogram showing total binding of [125I]Tyr4-bombesin, showing strong labeling of the lobules in most (arrow) but not all (double arrow) parts. Also the subsegmental duct is labeled in part (arrowhead). F: Autoradiogram showing nonspecific binding.

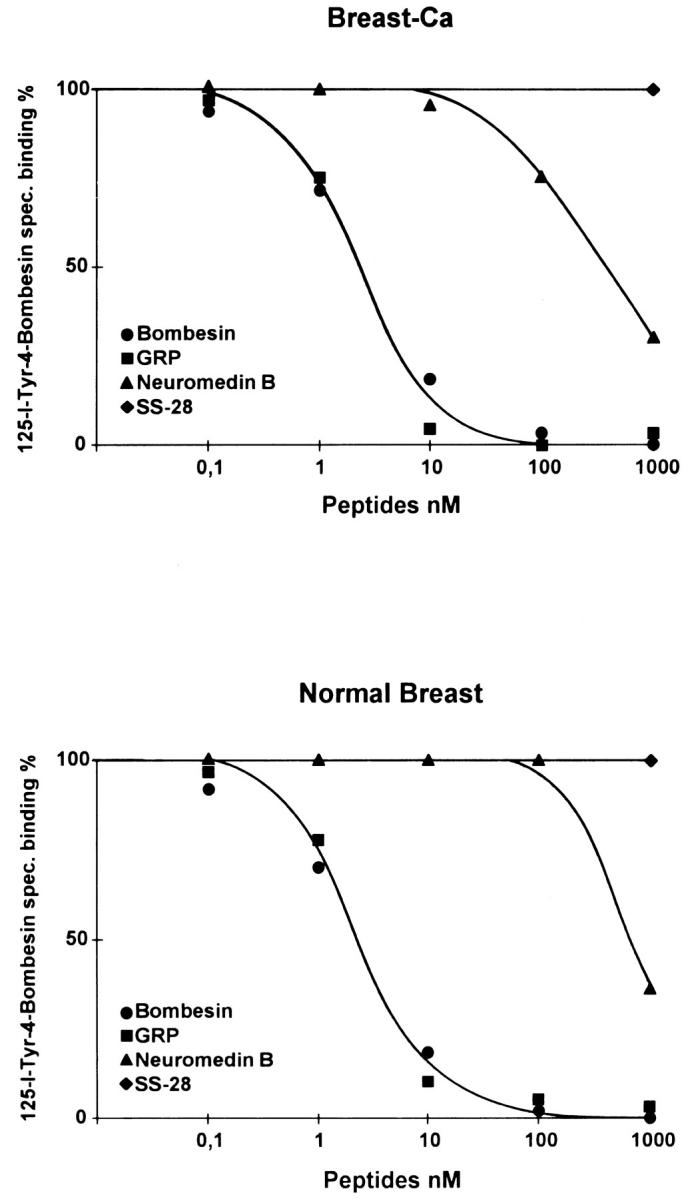

The receptor subtype identified in the breast carcinoma and non-neoplastic breast tissue corresponded to the GRP receptor subtype of the bombesin-like peptide receptor family. As shown in Figure 7 ▶ , there was a high-affinity binding in the nanomolar range for GRP and bombesin and a lower-affinity one for neuromedin B, characteristic for the GRP receptor subtype.

Figure 7.

High affinity and specificity of the [125I]Tyr4-bombesin binding in displacement experiments. Sections of tissue samples with breast carcinoma (upper graph), and normal breast tissue (lower graph) were incubated with [125I]Tyr4-bombesin and increasing concentrations of unlabeled bombesin (•), GRP (▪), neuromedin B (▴), and 1000 nmol/L somatostatin (♦). High-affinity displacement of the trace is found with bombesin and GRP, whereas neuromedin B shows lower affinity. Somatostatin has no effect. Nonspecific binding was subtracted from all of the values. The observed rank order of potencies of these analogs is characteristic for the GRP receptor subtype.

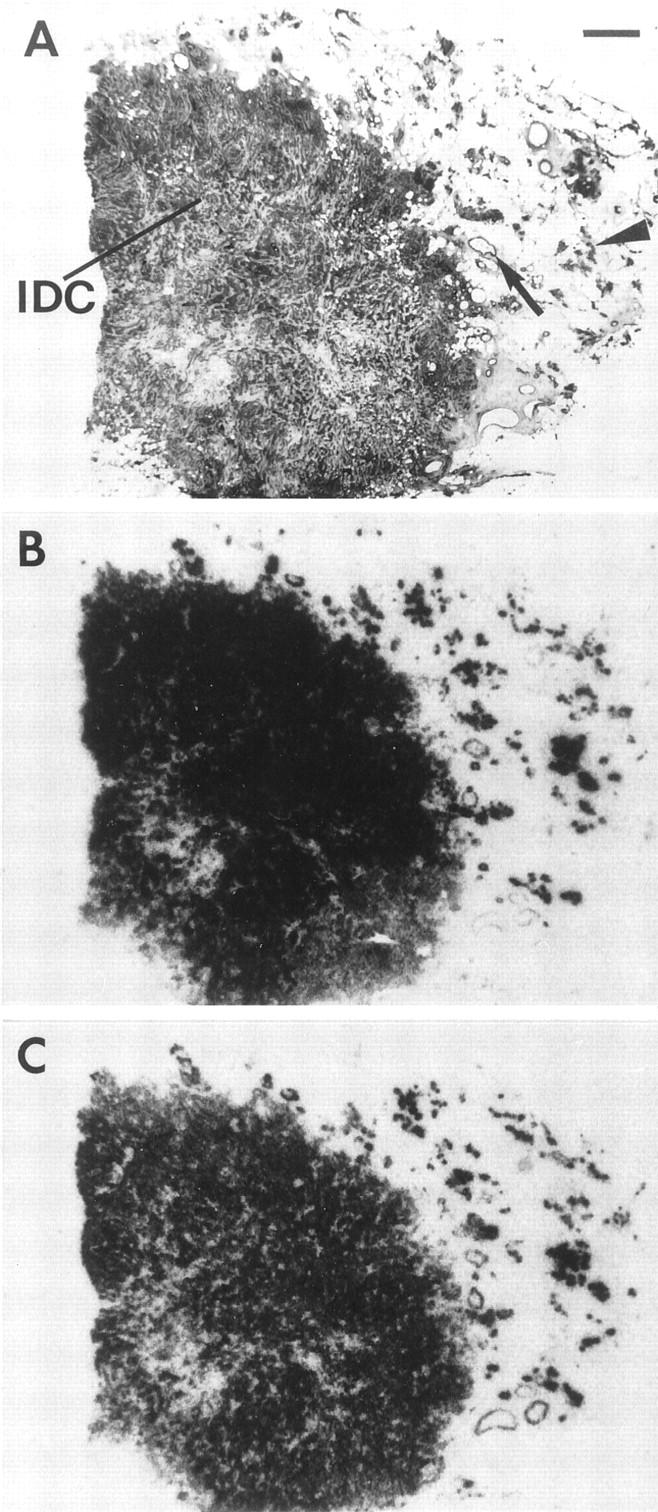

All tissues labeled with [125I]Tyr4-bombesin were also labeled with the universal radioligand [125I]d-Tyr6, β Ala11, Phe13, Nle14-bombesin(6–14) known to identify all four bombesin receptor subtypes. 23,24 The same receptor distribution was observed with both ligands in primary tumors, their lymph node metastases as well as non-neoplastic breast tissue; the same distribution was also noticed in all cases with a heterogeneous receptor expression. Moreover, [125I]d-Tyr6, β Ala11, Phe13, Nle14-bombesin(6–14) did not label an additional tissue present in those samples, which was not labeled by [125I]Tyr4-bombesin. Figure 8 ▶ illustrates a typical case with similar labeling of non-neoplastic and neoplastic breast tissue with both radioligands.

Figure 8.

Comparison of GRP receptor distribution in non-neoplastic and neoplastic breast tissues in a single case tested with [125I]Tyr4-bombesin (B) and [125I]d-Tyr6, β Ala11, Phe13, Nle14-bombesin(6–14) (C). A: H&E-stained section. IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; arrow, duct; arrowhead, lobules. Scale bar = 1 mm. Nonspecific binding is negligible. Non-neoplastic breast tissues, including ducts and lobules as well as invasive ductal carcinoma, are similarly labeled with both radioligands.

Discussion

This morphological receptor study shows the following most salient findings regarding breast carcinoma: First, primary breast carcinomas have a 62% incidence of GRP receptors. Second, a majority of carcinomas in situ, alone or concomitant with invasive carcinoma, are GRP receptor-positive as well, with a similarly high incidence. Third, the metastases of GRP receptor-positive tumors are GRP receptor-positive. The density values of the GRP receptors of primary tumors and of metastases are generally high.

The GRP receptors in the primary carcinomas are often heterogeneously distributed. It is well established that breast carcinomas may contain different tumor clones with distinct biological parameters. These clones may have different GRP receptor expression. A highly heterogeneous distribution has been reported previously in breast carcinoma for other receptors, ie, somatostatin, estrogen, and progesterone receptors. 28,29 Interestingly, this study shows that the metastases of the receptor-positive primary tumors have mostly a homogeneous receptor distribution. One may speculate that, if there are different tumor clones with distinct GRP receptor expression, the receptor-positive clones would metastasize easier than negative ones.

Although GRP receptors were previously detected in cell lines of breast carcinoma by receptor-binding techniques, 20,22 this is the first morphological study of GRP receptor in breast cancer by autoradiography. Compared with binding studies in cell lines or tissue homogenates, in which a 33% incidence of GRP receptor-positive breast carcinomas was found, 22 a significantly higher incidence of receptor-positive cases could be identified, however. The different incidence numbers may be due to methodological differences. Different assay conditions may be responsible for different sensitivities of detection. Moreover, the autoradiographic technique, as a morphological method, can assign the identified receptors to the various tissue compartments of the whole sample, ie, to the tumor tissue as well as to parenchyma, stroma, adipose tissue, vessels, or nerves. The use in this study of two different radioligands specific for bombesin receptors and giving identical results is a strong argument in favor of the specificity of the reported findings.

Another main result of this study is the demonstration of GRP receptors in non-neoplastic breast glands in all investigated tissue samples. Both lobules and ductules express receptors, ranging from moderate- to very high-density values. It is interesting that, in all tissues, the receptor distribution is heterogeneous, namely with groups of receptor-positive lobules or ducts adjacent to receptor-negative ones. The high incidence of GRP receptors found in the breast in this study contrasts with the much lower incidence of hormone receptors such as estrogen and progesterone receptors in normal human breast tissue. In the mean, 7% of mammary epithelial cells or even less expressed estrogen receptors, 30,31 and 12% expressed progesterone receptors. 30 The distribution pattern of these receptors has also been described to be heterogeneous in ductules and lobules, 32 as it is found for GRP receptors. The reason for such a GRP receptor heterogeneity in normal tissue is not clear and needs further investigations. Because in our study the sample size containing non-neoplastic breast tissue was often small, the percentage of receptor heterogeneity may not be representative for the whole breast. The observed heterogeneity could be related to a heterogeneous innervation pattern of the glands and lobules, assuming that GRP plays a neurotransmitter role in the breast, as it does in the gastrointestinal tract. 14

The pharmacological characterization by competition experiments reveals the GRP receptor as the main bombesin receptor subtype involved in non-neoplastic and malignant breast tissue. Bombesin and GRP show a very high affinity, and neuromedin B a lower one, as expected for this receptor subtype; 33 unrelated peptides like somatostatin show no affinity. The use of picomolar concentrations of radioligand (as low as 20 pmol/L) that can be fully displaced by nanomolar amounts of unlabeled bombesin and GRP is a strong argument of the very high affinity of these binding sites. The receptor subtyping is important information considering the large number of synthetic analogs having a high affinity for precisely this GRP receptor subtype.

The autoradiographic method allows also to investigate peritumoral vessels and other tumor-surrounding tissues. 34 It is important to note that the lymphatic tissues surrounding the lymph node metastases were always GRP receptor-negative. Moreover, in breast cancer, peritumoral vessels and stromal tissues were not expressing GRP receptors at difference to what is seen with somatostatin receptors in several tumor types. 34,35 Therefore, in the resected tissue samples and with the methodology used, only breast tissue, non-neoplastic or neoplastic, is massively GRP receptor-positive.

Although a possible physiological action of GRP in normal breast tissue is so far unknown, the strong GRP receptor expression in non-neoplastic human breast tissues suggests a specific GRP action in this tissue. For such an in vivo action, not only a functional receptor is required but also the presence of the corresponding endogenous ligand in the immediate surroundings. GRP has not been detected in normal human breast tissue so far. 36 However bombesin-like immunoreactivity was shown in human breast cyst fluids 37 and in human milk. 38 The concentration of bombesin-like immunoreactivity in human breast milk was threefold greater than the corresponding plasma concentration. 39 Moreover, patients with benign breast disease showed a significantly higher bombesin-like immunoreactivity concentration in the blood than did healthy patients. 40 Moreover, in other species, for instance the cow, GRP could be identified in the mammary glands. 15 These data may represent indirect evidence of an endogenous source of bombesin-like peptides in normal breast tissue or, at least, that the endogenous peptide may be reaching the breast tissue.

The presence of endogenous bombesin-like peptides in breast carcinomas is more extensively documented and may support the proposal of a functionality of GRP receptors. Bombesin-like peptides in breast carcinoma tissues have been detected by immunological methods, 41 by Northern blot analysis for GRP-mRNA, 42 and, in the blood of breast carcinoma patients, by immunoassays. 40 Moreover, there is evidence for a role of bombesin-like peptides in the growth of breast cancer cells. 18 An autocrine growth-stimulatory effect of bombesin has been shown in small-cell lung carcinoma in vivo. 16 Such a mechanism of action was also proposed for breast carcinomas. 42 Our study, therefore, by showing clearly the presence of an essential constituent of this regulatory feedback loop, namely the GRP receptors, in breast carcinomas, supports such a proposal.

The expression of GRP receptors in breast carcinomas may have clinical implications. For diagnostic purposes, the identification of a high expression of tumoral GRP receptors with GRP receptor scintigraphy may be a potentially valuable tool to visualize breast tumors, in particular their axillary lymph node metastases. The high receptor density and homogeneous distribution in axillary lymph node metastases compared with the lack of GRP receptors in surrounding lymphoreticular tissue (high tumor to background ratio) may represent a crucial argument for optimal diagnosis of metastases. From a therapeutic point of view, it should be noticed that, over the last few years, potent and selective bombesin antagonists have been developed. 43-45 These compounds show, in animal tumor models and human cell lines, a strong inhibition of breast cancer growth. 18,46 Further, bombesin analogs have been designed as carriers for cytotoxic drugs, which were also shown to inhibit the growth of cancer cell lines. 47 Therefore, the application of this type of compound as a long-term treatment of breast cancer may be considered as a future therapeutic goal. In addition to a possible cytotoxic drug therapy, the recent synthesis of bombesin analogs linked to β-emitters may permit their use for radiotherapy 48 to destroy GRP receptor-positive tumors, comparable with the use of 90Y-labeled octreotide to destroy somatostatin receptor-positive tumors. 8

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. J. C. Reubi, M.D., Division of Cell Biology and Experimental Cancer Research, Institute of Pathology, University of Berne, Murtenstrasse 31, PO Box 62, CH-Berne, Switzerland. E-mail: reubi@patho.unibe.ch.

References

- 1.Reubi JC: Neuropeptide receptors in health and disease: the molecular basis for in vivo imaging. J Nucl Med 1995, 36:1825-1835 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reubi JC: In vitro identification of vasoactive intestinal peptide receptors in human tumors: implications for tumor imaging. J Nucl Med 1995, 36:1846-1853 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reubi JC, Schaer JC, Waser B: Cholecystokinin(CCK)-A, and CCK-B/gastrin receptors in human tumors. Cancer Res 1997, 57:1377-1386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markwalder R, Reubi JC: Gastrin-releasing peptide receptors in the human prostate: relation to neoplastic transformation. Cancer Res 1999, 59:1152-1159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krenning EP, Kwekkeboom DJ, Pauwels S, Kvols LK, Reubi JC: Somatostatin Receptor Scintigraphy. Freeman LM eds. Nuclear Medicine Annual. 1995, :pp 1-50 Raven Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virgolini I, Raderer M, Kurtaran A, Angelberger P, Banyai S, Yang Q, Li S, Banyai M, Pidlich J, Niederle B, Scheithauer W, Valent P: Vasoactive intestinal peptide-receptor imaging for the localization of intestinal adenocarcinomas and endocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 1994, 331:1116-1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behr TM, Jenner N, Radetzky S, Behe M, Gratz S, Yucekent S, Raue F, Becker W: Targeting of cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptors in vivo: preclinical and initial clinical evaluation of the diagnostic and therapeutic potential of radiolabelled gastrin. Eur J Nucl Med 1998, 25:424-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otte A, Mueller-Brand J, Dellas S, Nitzsche EU, Herrmann R, Maecke HR: Yttrium-90-labelled somatostatin-analogue for cancer treatment. Lancet 1998, 351:417-418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagy A, Schally AV, Halmos G, Armatis P, Cai RZ, Csernus V, Kovacs M, Koppan M, Szepeshazi K, Kahan Z: Synthesis and biological evaluation of cytotoxic analogs of somatostatin containing doxorubicin or its intensely potent derivative, 2-pyrrolinodoxorubicin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:1794-1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zia H, Hida T, Jakowlew S, Birrer M, Gozes Y, Reubi JC, Fridkin M, Gozes I, Moody TW: Breast cancer growth is inhibited by vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) hybrid, a synthetic VIP receptor antagonist. Cancer Res 1996, 56:3486-3489 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erspamer V: Discovery, isolation, and characterization of bombesin-like peptides. Ann NY Acad Sci 1988, 547:3-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozengurt E, Sinnett-Smith J: Bombesin stimulation of DNA synthesis and cell division in cultures of Swiss 3T3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1983, 80:2936-2940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willey JC, Lechner JF, Harris CC: Bombesin and the C-terminal tetradecapeptide of gastrin-releasing peptide are growth factors for normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res 1984, 153:245-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunnett N: Gastrin-releasing peptide. Walsh JH Dockray GJ eds. Gut Peptides: Biochemistry and Physiology. 1994, :pp 423-445 Raven Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunday ME, Kaplan LM, Motoyama E, Chin WW, Spindel ER: Gastrin-releasing peptide (mammalian bombesin) gene expression in health and disease. Lab Invest 1988, 59:5-24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuttitta F, Carney DN, Mulshine J, Moody TW, Fedorko J, Fischler A, Minna JD: Bombesin-like peptides can function as autocrine growth factors in human small-cell lung cancer. Nature 1985, 316:823-826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickson RB, Lippman ME: Estrogenic regulation of growth and polypeptide growth factor secretion in human breast carcinoma. Endocr Rev 1987, 8:29-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyazaki M, Lamharzi N, Schally AV, Halmos G, Szepeshazi K, Groot K, Cai RZ: Inhibition of growth of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer xenografts in nude mice by bombesin/gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) antagonists RC- 3940-II and RC-3095. Eur J Cancer 1998, 34:710-717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel KV, Schrey MP: Activation of inositol phospholipid signaling and Ca2+ efflux in human breast cancer cells by bombesin. Cancer Res 1990, 50:235-239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giacchetti S, Gauville C, de Cremoux P, Bertin L, Berthon P, Abita JP, Cuttitta F, Calvo F: Characterization, in some human breast cancer cell lines, of gastrin-releasing peptide-like receptors which are absent in normal breast epithelial cells. Int J Cancer 1990, 46:293-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reubi JC: Relevance of somatostatin receptors and other peptide receptors in pathology. Endocr Pathol 1997, 8:11-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halmos G, Wittliff JL, Schally AV: Characterization of bombesin/gastrin-releasing peptide receptors in human breast cancer and their relationship to steroid receptor expression. Cancer Res 1995, 55:280-287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mantey SA, Weber HC, Sainz E, Akeson M, Ryan RR, Pradhan TK, Searles RP, Spindel ER, Battey JF, Coy DH, Jensen RT: Discovery of a high affinity radioligand for the human orphan receptor, bombesin receptor subtype 3, which demonstrates that it has a unique pharmacology compared with other mammalian bombesin receptors. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:26062-26071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pradhan TK, Katsuno T, Taylor JE, Kim SH, Ryan RR, Mantey SA, Donohue PJ, Weber HC, Sainz E, Battey JF, Coy DH, Jensen RT: Identification of a unique ligand which has high affinity for all four bombesin receptor subtypes. Eur J Pharmacol 1998, 343:275-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tavassoli FA: General considerations. Tavassoli FA eds. Pathology of the Breast. 1992, :pp 25-62 Appleton & Lange, Norwalk, CT, [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reubi JC, Kvols LK, Waser B, Nagorney DM, Heitz PU, Charboneau JW, Reading CC, Moertel C: Detection of somatostatin receptors in surgical and percutaneous needle biopsy samples of carcinoids and islet cell carcinomas. Cancer Res 1990, 50:5969-5977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vigna SR, Mantyh CR, Giraud AS, Soll AH, Walsh JH, Mantyh PW: Localization of specific binding sites for bombesin in the canine gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology 1987, 93:1287-1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reubi JC, Waser B, Foekens JA, Klijn JG, Lamberts SW, Laissue J: Somatostatin receptor incidence and distribution in breast cancer using receptor autoradiography: relationship to EGF receptors. Int J Cancer 1990, 46:416-420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiner A, Neumeister B, Spona J, Reiner G, Schemper M, Jakesz R: Immunocytochemical localization of estrogen and progesterone receptor and prognosis in human primary breast cancer. Cancer Res 1990, 50:7057-7061 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams G, Anderson E, Howell A, Watson R, Coyne J, Roberts SA, Potten CS: Oral contraceptive (OCP) use increases proliferation and decreases oestrogen receptor content of epithelial cells in the normal human breast. Int J Cancer 1991, 48:206-210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen OW, Hoyer PE, van Deurs B: Frequency and distribution of estrogen receptor-positive cells in normal, nonlactating human breast tissue. Cancer Res 1987, 47:5748-5751 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ricketts D, Turnbull L, Ryall G, Bakhshi R, Rawson NS, Gazet JC, Nolan C, Coombes RC: Estrogen and progesterone receptors in the normal female breast. Cancer Res 1991, 51:1817-1822 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Battey J, Wada E: Two distinct receptor subtypes for mammalian bombesin-like peptides. Trends Neurosci 1991, 14:524-528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reubi JC, Mazzucchelli L, Hennig I, Laissue JA: Local up-regulation of neuropeptide receptors in host blood vessels around human colorectal cancers. Gastroenterology 1996, 110:1719-1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denzler B, Reubi JC: Expression of somatostatin receptors in peritumoral veins of human tumors. Cancer 1999, 85:188-198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bostwick DG, Bensch KG: Gastrin releasing peptide in human neuroendocrine tumours. J Pathol 1985, 147:237-244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber CJ, O’Dorisio TM, McDonald TJ, Howe B, Koschitzky T, Merriam L: Gastrin-releasing peptide-, calcitonin gene-related peptide-, and calcitonin-like immunoreactivity in human breast cyst fluid and gastrin-releasing peptide-like immunoreactivity in human breast carcinoma cell lines. Surgery 1989, 106:1134-1140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ekman R, Ivarsson S, Jansson L: Bombesin, neurotensin, and pro-γ-melanotropin immunoreactants in human milk. Regul Pept 1985, 10:99-105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berseth CL, Michener SR, Nordyke CK, Go VL: Postpartum changes in pattern of gastrointestinal regulatory peptides in human milk. Am J Clin Nutr 1990, 51:985-990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milewicz A, Daroszewski J, Jedrzejak J, Bielanski W, Tupikowski W, Marciniak M, Jedrzejuk D: Bombesin plasma levels in patients with benign and malignant breast disease. Gynecol Endocrinol 1994, 8:45-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKillop JM, Carragher A, Johnston CF, Murphy RF, Buchanan KD: Identification of GRP in a small population of human breast carcinomas. Regul Pept 1988, 22:420 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pagani A, Papotti M, Sanfilippo B, Bussolati G: Expression of the gastrin-releasing peptide gene in carcinomas of the breast. Int J Cancer 1991, 47:371-375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Castiglione R, Gozzini L: Bombesin receptor antagonists. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 1996, 24:117-151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinski J, Reile H, Halmos G, Groot K, Schally AV: Inhibitory effects of somatostatin analogue RC-160 and bombesin/gastrin- releasing peptide antagonist RC-3095 on the growth of the androgen-independent Dunning R-3327-AT-1 rat prostate cancer. Cancer Res 1994, 54:169-174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen RT, Coy DH: Progress in the development of potent bombesin receptor antagonists. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1991, 12:13-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yano T, Pinski J, Szepeshazi K, Halmos G, Radulovic S, Groot K, Schally AV: Inhibitory effect of bombesin/gastrin-releasing peptide antagonist RC- 3095 and luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone antagonist SB-75 on the growth of MCF-7 MIII human breast cancer xenografts in athymic nude mice. Cancer 1994, 73:1229-1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagy A, Armatis P, Cai RZ, Szepeshazi K, Halmos G, Schally AV: Design, synthesis, and in vitro evaluation of cytotoxic analogs of bombesin-like peptides containing doxorubicin or its intensely potent derivative, 2-pyrrolinodoxorubicin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:652-656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Safavy A, Khazaeli MB, Qin H, Buchsbaum DJ: Synthesis of bombesin analogues for radiolabeling with rhenium-188. Cancer 1997, 80:2354-2359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]