Abstract

Recognition of a ligation site in a protein molecule is important for identifying its biological activity. The model for in silico recognition of ligation sites in proteins is presented. The idealized hydrophobic core stabilizing protein structure is represented by a three-dimensional Gaussian function. The experimentally observed distribution of hydrophobicity compared with the theoretical distribution reveals differences. The area of high differences indicates the ligation site.

Availability

Keywords: hydrophobicity, active site, function recognition, protein structure

Background

The classic model of an oil drop representing the hydrophobic core in proteins given by Kauzmann [1] was intended to visualize the importance of hydrophobic interactions responsible for forming and stabilizing the protein tertiary structure. [2,3,4] The hydrophilic surface with the hydrophobic center of the molecule is generally accepted [5,6] as the model according to which the amino acid sequence partitions a protein into its inside and outside. [7]

The model oriented on localization of the area responsible for ligand binding, based on characteristics of spatial distribution of hydrophobicity which changes from protein interior (maximal hydrophobicity) to exterior (close to zero level of hydrophobicity), can be represented by a three-dimensional Gaussian function. [8,9,10 ] The simple comparison of theoretical (Gaussian function) and empirical spatial distributions of hydrophobicity in protein allows identification of the areas of high discrepancy, which, as observed in crystal forms of protein-ligand complexes, can be recognized as ligation sites in proteins.

Methodology

Data

Complexes selected for analysis presented in this paper are: cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PDB ID: 1CDK), cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2 (PDB ID: 1E1V), proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase ABL (PDB ID: 1IEP), S-lectin (PDB ID: 1SLT).

Grid system

The grid system (with constant step size) is constructed for the protein molecule localized with its geometrical center in the origin of the coordinate system (0,0,0)and oriented as follows: longest inter-effective atoms (side chains represented by the geometrical centers) distance along the X-axis and longest distance between projections (on YZ plane) of effective atoms along the Y-axis. The size of the ellipsoid can be calculated by taking the maximum and minimum values of the X, Y and Z coordinates found in the molecule, oriented as above.

Theoretical hydrophobicity distribution:

The theoretical hydrophobicity value for each grid point can be calculated according to a three-dimensional Gaussian function: as given in the PDF file linked below

Empirical hydrophobicity distribution

The empirical hydrophobicity distribution can be calculated using the original function introduced by Levitt [11]:as given in the PDF file linked below

Prediction results

Theoretical versus empirical hydrophobicity distribution

Since theoretical (Equation 1) and empirical (Equation 2) hydrophobicity distributions are standardized, the hydrophobicity values attributed to each grid point can be compared by a simple subtraction:

| (Equation 3) |

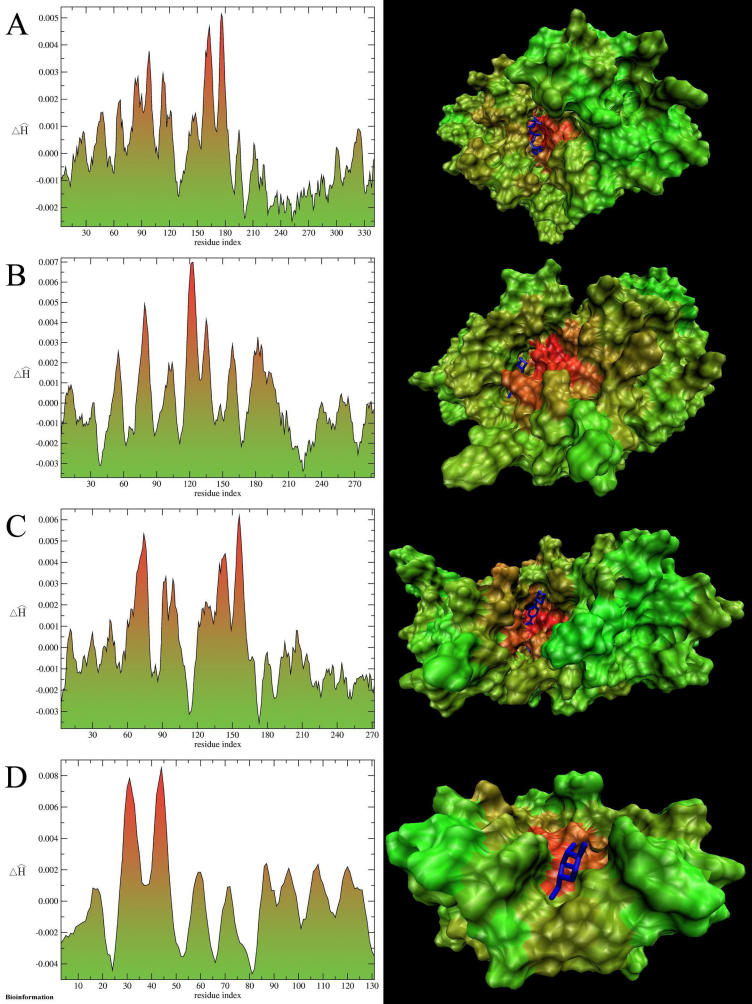

The color scale introduced to express the magnitude of difference ΔĤ in a particular protein (Figure 1) area enables the visualization of the localization of these discrepancies in the protein molecule. The profile of ΔĤi along the polypeptide chain (also in color scale) reveals the fragments of polypeptide of high difference between idealized and empirical hydrophobicity density. The same color scale applied to a three-dimensional representation of protein molecule allows for the localization of the ligation site in the protein molecule. The results of analysis of selected protein molecules are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

One-dimensional profiles of ΔĤ per amino acid (color scale) (left column) and three-dimensional distribution of ΔĤ on protein surface (right column): A AMP-dependent protein kinase complexed with 5'-adenyly-imido-triphosphate, B cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2 complexed with 6-O-cyclohexylmethyl guanine, C proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase ABL complexed with STI-571, D S-lectin complexed with D-galactose. The ligands (dark blue thick line) are localized at their binding sites according to crystal structure

Conclusion

The many proteins of unknown biological function, identified on the basis of genome analysis, await a unified automated method for determining their biological activity. [12] The next step is to develop methods able to predict a protein's function from an examination of its structure. Some of the techniques used to identify functionally important residues from the sequence or structure are based on searching for homologues of proteins of known function. [13,14] However, homologues need not have related activity, particularly when the sequence identity is below 25%. [15] The model presented in this paper is oriented on localizing the area responsible for ligand binding, based on the characteristics of the spatial distribution of hydrophobicity in a protein molecule. It is generally accepted that the core region is not well described by a spheroid of buried residues surrounded by surface residues due to hydrophobic channels that permeate the molecule. [16,17] This being so, we should be able to identify regions with high deviation versus the ideal model by making a simple comparison of the theoretical (idealized according to the Gaussian function) and empirical spatial distribution of hydrophobicity in a protein. The regions recognized by high hydrophobicity density differences seem to reveal functionally important sites in proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Prof. Marek Pawlikowski (Faculty of Chemistry, Jagiellonian University) for fruitful discussions. This research was supported by the Polish State Committee for Scientific Research (KBN) grant 3 T11F 003 28 and Collegium Medicum grants 501/P/133/L and WŁ/222/P/L.

Footnotes

Citation:Brylinskiet al., Bioinformation 1(4): 127-129 (2006)

References

- 1.Kauzmann W. Adv Protein Chem. 1959;14:1. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klapper MH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;229:557. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(71)90271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klotz IM. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1970;138:704. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(70)90401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meirovitch H, Scheraga HA. Macromolecules. 1980;13:1398. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meirovitch H, Scheraga HA. Macromolecules. 1981;14:340. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose GD, Roy S. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1980;77:4643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brylinski M, et al. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2006;23:519. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2006.10507076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brylinski M, et al. Biochimie. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konieczny L, et al. In Silico Biol. 2006;6:0002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levitt M. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:59. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burley SK, et al. Nat Genet. 1999;23:151. doi: 10.1038/13783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bork P, et al. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:707. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skolnick J, Fetrow JS. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:34. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devos D, Valencia A. Proteins. 2000;41:98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crippen GM, Kuntz ID. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1978;12:47. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1978.tb02867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuntz ID, Crippen GM. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1979;13:223. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1979.tb01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.