Abstract

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in DNA sequences are composed of tandem iterations of short oligonucleotides and may have functional and/or structural properties that distinguish them from general DNA sequences. They are variable in length because of slip-strand mutations and may also affect local structure of the DNA molecule or the encoded proteins. Long SSRs (LSSRs) are common in eukaryotes but rare in most prokaryotes. In pathogens, SSRs can enhance antigenic variance of the pathogen population in a strategy that counteracts the host immune response. We analyze representations of SSRs in >300 prokaryotic genomes and report significant differences among different prokaryotes as well as among different types of SSRs. LSSRs composed of short oligonucleotides (1–4 bp length, designated LSSR1–4) are often found in host-adapted pathogens with reduced genomes that are not known to readily survive in a natural environment outside the host. In contrast, LSSRs composed of longer oligonucleotides (5–11 bp length, designated LSSR5–11) are found mostly in nonpathogens and opportunistic pathogens with large genomes. Comparisons among SSRs of different lengths suggest that LSSR1–4 are likely maintained by selection. This is consistent with the established role of some LSSR1–4 in enhancing antigenic variance. By contrast, abundance of LSSR5–11 in some genomes may reflect the SSRs' general tendency to expand rather than their specific role in the organisms' physiology. Differences among genomes in terms of SSR representations and their possible interpretations are discussed.

Keywords: comparative genomics, phase variation-slip, strand mutations, tandem repeats, microsatellites

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes represent hypermutable loci subject to reversible changes in the SSR length (1–6). Some pathogens use SSRs in a strategy that counteracts the host immune response by increasing the antigenic variance of the pathogen population (4, 5, 7). In this scenario, SSRs located in protein coding regions or in upstream regulatory regions can reversibly deactivate or alter genes involved in interactions with the host (4, 8). Some SSRs may also affect local structure of the DNA molecule (9–12). Trinucleotide and hexanucleotide repeats in genes translate into amino acid runs and alternating patterns, which may play special roles in protein structure (13, 14) and are enriched in human proteins associated with genetic diseases (15). The best studied cases of SSRs expansion relate to triplet repeats that can cause genetic disorders in humans. Such repeats may be located in both protein-coding and regulatory regions and can alter the structure of the encoded proteins or the DNA molecule when they expand beyond a certain length (16).

Long SSRs tend to be dramatically overrepresented (i.e., found significantly more often than expected by chance) in eukaryotic genomes (2, 17, 18).¶ In prokaryotes, long SSRs are generally less common and may be subject to negative selection (19). Significant differences in SSR representations exist even among closely related species (20), suggesting that the SSR abundance may change relatively rapidly during evolution.

Assessments of SSR representations generally rely on stochastic models used as a null hypothesis. Previous analyses used a homogeneous Bernoulli model (19, 21). In this work, we analyze SSR representations in >300 prokaryotic genomes using more realistic stochastic models of varying complexity. Our results indicate large differences among prokaryotes in terms of SSR representations and point to possible functional differences among SSRs of different types.

Results

Comparison of Long SSR Representations Among Prokaryotic Genomes.

SSR representations in most prokaryotic genomes show few deviations from expectations based on random models except for the suppression of mononucleotide SSRs exceeding a length of 8 bp [Fig. 1 and supporting information (SI) Fig. 4], which is common among prokaryotes (19, 20). SI Table 5 displays counts Nk* of LSSRs for k between 1 and 11 bp and for 378 complete prokaryotic chromosomes (plasmids and megaplasmids are not included). Data for selected species are shown in Table 1. The largest numbers of LSSRs are found in the closely related cyanobacteria Nostoc and Anabaena, followed by Burkholderia species, Frankia, Streptomyces, Methanosarcina, Xanthomonas, and Polaromonas, all with >100 LSSRs. The LSSR counts appear unrelated to taxonomical or phylogenetic relationships beyond the level of genus. The absence of correlations with phylogeny suggests that long SSRs can spread through a genome relatively quickly during evolution. Firmicutes (except Mollicutes) are the only well represented group that always has low LSSR counts. Interestingly, long heptameric repeats (k = 7) are far more common than other types of repeats. Long tri-, hexa- and nonanucleotide repeats are often located in genes, whereas long SSRs of oligonucleotides whose lengths are not multiples of three are generally found in intergenic regions. These SSRs may cause frameshift mutations and are probably selected against in protein coding genes.

Fig. 1.

Mono- and dinucleotide SSRs in the E. coli K12 genome. The plots show the counts Nk(l) for mononucleotide (k = 1, Upper) and dinucleotide (k = 2, Lower) SSRs in the genomic DNA sequence (filled circles) and in random sequences generated by six different stochastic models (gray lines): homogeneous Bernoulli and first-order Markov (dashed lines), and four heterogeneous models of varying complexity (solid lines; see Methods).

Table 1.

Counts of LSSRs in selected genomes

| Genome | Length of the repeated oligonucleotide, bp |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| B. mallei ATCC 23344 chr. 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6/5 | 27/15 | 74/74 | 49/49 | 35/17 | 10/9 | 12/10 |

| B. mallei ATCC 23344 chr. 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4/0 | 34/19 | 92/70 | 55/30 | 75/21 | 18/15 | 15/12 |

| B. pseudomallei 1710b chr. 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/0 | 0 | 9/4 | 43/22 | 83/57 | 74/45 | 58/16 | 7/5 | 14/10 |

| B. pseudomallei 1710b chr. 2 | 0 | 0 | 1/0 | 0 | 8/5 | 53/13 | 116/88 | 79/64 | 74/23 | 32/23 | 18/6 |

| B. pseudomallei K96243 chr. 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9/8 | 45/37 | 81/80 | 68/67 | 56/36 | 18/18 | 22/21 |

| B. pseudomallei K96243 chr. 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 | 8/7 | 64/42 | 117/116 | 79/76 | 86/40 | 19/19 | 13/13 |

| B. thailandensis E264 chr. 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/0 | 1/0 | 8/5 | 16/6 | 20/16 | 18/15 | 15/5 | 9/7 | 7/7 |

| B. thailandensis E264 chr. 2 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 | 0 | 4/4 | 28/11 | 30/23 | 17/14 | 32/6 | 8/6 | 3/3 |

| L. intracellularis PHE-MN1–00 | 3/3 | 4/4 | 27/18 | 1/1 | 0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0 | 1/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| M. barkeri str. fusaro | 1/1 | 0 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 5/5 | 4/4 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 14/8 | 36/36 | 44/43 |

| M. mazei Go1 | 0 | 0 | 9/6 | 9/8 | 2/2 | 6/5 | 4/4 | 10/10 | 8/5 | 18/18 | 25/24 |

The first number indicates the counts in the complete genome, whereas the second number signifies the LSSRs in the intergenic regions. See Methods for definition of LSSRs.

Table 2 shows correlations among counts of different SSR types across different genomes. The counts of LSSR5–11 (k ≥ 5) correlate well among each other. Weaker correlations are also observed among LSSR1–3 (k ≤ 3) but not between LSSR5–11 and LSSR1–3 counts. We include tetranucleotide LSSRs in the LSSR1–4 group, although they exhibit no consistently strong correlations with either LSSR1–3 or LSSR5–11. The lack of correlations between LSSR1–4 and LSSR5–11 indicate that the two LSSR types tend to occur in different organisms. Tables 3 and 4 display lists of prokaryotes with high counts of LSSR1–4 and LSSR5–11, respectively. Both collections include species from diverse taxa. Few prokaryotic genomes contain many LSSR1–4, whereas LSSR5–11 are more common. The two groups are distinct with respect to their genome sizes, G+C content, and pathogenic lifestyle. Most genomes with seven or more LSSR1–4 (Table 3) are small in size, generally ≈2 Mb or less. By contrast, the smallest genome among the 33 with at least 60 LSSR5–11 (Table 4) is 2.5 Mb in size (Xylella fastidiosa) and most are >4 Mb. Genomes with many LSSR5–11 tend to have high G+C content (mostly >60%, Table 4) whereas genomes with LSSR1–4 generally have low G+C content (mostly <40%). Most genomes in Table 3 belong to host-adapted pathogens, including several but not all Mycoplasma species (20), which are not known to survive readily outside the host. The other three are mesophilic archaeal methanogens Methanosarcina mazei, Methanosarcina barkeri, and Methanococcoides burtonii. The two Methanosarcina genomes are unusual in possessing high counts of both LSSR1–4 and LSSR5–11. No thermophiles feature among the genomes with high LSSR counts.

Table 2.

Correlations among counts of LSSRs of different types

| k | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| 2 | * | 0.29 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| 3 | * | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.09 | |

| 4 | * | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.23 | ||

| 5 | * | 0.71 | 0.27 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.53 | |||

| 6 | * | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.52 | ||||

| 7 | * | 0.74 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.19 | |||||

| 8 | * | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.48 | ||||||

| 9 | * | 0.73 | 0.56 | |||||||

| 10 | * | 0.82 |

Pearson correlation coefficients among counts of LSSRs of different types (differentiated by the length of the repeated oligonucleotide, k) in 378 prokaryotic chromosomes are displayed. High values indicate that the LSSRs of the two types tend to occur in the same genomes, whereas values close to zero suggest that the two LSSR types are unrelated. Values ≥0.30 are shown in bold type.

Table 3.

Genomes with high counts of LSSR1–4

| Genome | Taxonomy | LSSR1–4 count | Genome size, Mb | G+C, % | Dependence on a host |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma gallisepticum R | Mollicutes | 37 | 1.0 | 31.5 | Fastidious growth in laboratory |

| Lawsonia intracellularis PHE/MN1–00 | δ-Proteobacteria | 35 | 1.7 | 33.3 | Obligate intracellular pathogen |

| Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae 7448, J, 232 | Mollicutes | 27–33 | 0.9 | 28.5–28.6 | Fastidious growth in laboratory |

| Methanosarcina mazei Go1 | Euryarchaeota | 18 | 4.1 | 41.5 | None |

| Mycobacterium leprae TN | Actinobacteria | 16 | 3.3 | 57.8 | Does not grow in a laboratory culture |

| Haemophilus influenzae 86–028NP, Rd | γ-Proteobacteria | 13–14 | 1.8–1.9 | 38.1–38.2 | Obligate parasites or commensal organisms |

| Methanosarcina barkeri str. Fusaro | Euryarchaeota | 13 | 4.9 | 39.3 | None |

| Mycoplasma capricolum ATCC 27343 | Mollicutes | 12 | 1.0 | 23.8 | Fastidious growth in laboratory |

| Methanococcoides burtonii DSM 6242 | Euryarchaeota | 11 | 2.6 | 40.8 | None |

| Mycoplasma pulmonis UAB CTIP | Mollicutes | 11 | 1.0 | 26.6 | Fastidious growth in laboratory |

| Mycoplasma mycoides SC str. PG1 | Mollicutes | 9 | 1.2 | 24.0 | Fastidious growth in laboratory |

| Helicobacter pylori 26695, J99, HPAG1 | ε-Proteobacteria | 7–8 | 1.6–1.7 | 38.9–39.2 | Extracellular pathogen |

| Mycoplasma genitalium G37 | Mollicutes | 8 | 0.6 | 31.7 | Fastidious growth in laboratory |

| Xanthomonas oryzae MAFF 311018 | γ-Proteobacteria | 8 | 4.9 | 63.7 | Plant pathogen |

List of prokaryotic genomes with ≥7 LSSR1–4. Data for multiple strains of the same species are listed as a range of values. The ″dependence on a host″ information was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information's Genome Project Database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and references therein.

Table 4.

Genomes with high counts of LSSR5–11

| Genome | Taxonomy | LSSR5–11 counts | Genome size, Mb | G+C, % | Habitat and host association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burkholderia pseudomallei K96243, 1710b | β-Proteobacteria | 668–685 | 7.3 | 68.5 | Terrestrial habitats, opportunistic pathogen |

| Burkholderia mallei ATCC 23344 | β-Proteobacteria | 506 | 5.8 | 69 | Host adapted, not found outside the host |

| Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 | Cyanobacteria | 501 | 6.4 | 41.4 | Multiple habitats, not associated with a host |

| Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 | Cyanobacteria | 434 | 6.4 | 41.3 | Multiple habitats, not associated with a host |

| Frankia sp. CcI3 | Actinobacteria | 262 | 5.4 | 70.1 | Nitrogen-fixing symbiont of plants |

| Burkholderia thailandensis E264 | β-Proteobacteria | 215 | 6.7 | 68.1 | Nonpathogenic, found mainly in soil |

| Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 | Actinobacteria | 206 | 9 | 70.7 | Soil and other habitats, not associated with a host |

| Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 | β-Proteobacteria | 163 | 9.7 | 62.8 | May be associated with white-rot fungus |

| Streptomyces coelicolor A32 | Actinobacteria | 151 | 8.7 | 72.1 | Soil and other habitats, not associated with a host |

| Xanthomonas campestris 8004, ATCC 33913, 85–10 | γ-Proteobacteria | 79–131 | 5.0–5.2 | 64.7–65.1 | Plant pathogen |

| Burkholderia sp. 383 | β-Proteobacteria | 129 | 8.7 | 66.7 | Multiple habitats |

| Methanosarcina barkeri str. Fusaro | Euryarchaeota | 117 | 4.9 | 39.3 | Mesophilic methanogen, not associated with a host |

| Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri str. 306 | γ-Proteobacteria | 101 | 5.2 | 64.8 | Plant pathogen |

| Polaromonas sp. JS666 | β-Proteobacteria | 100 | 5.2 | 62.5 | Artificial, contaminated environments, not associated with a host |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP 32953 | γ-Proteobacteria | 81 | 4.7 | 47.6 | Multiple habitats, opportunistic pathogen |

| Xylella fastidiosa Temecula1 | γ-Proteobacteria | 75 | 2.5 | 51.8 | Plant pathogen, spreads by an insect vector |

| Saccharophagus degradans 2–40 | γ-Proteobacteria | 74 | 5.1 | 45.8 | Marine habitat, not associated with a host |

| Methanosarcina mazei Go1 | Euryarchaeota | 73 | 4.1 | 41.5 | Mesophilic methanogen, not associated with a host |

| Xanthomonas oryzae KACC10331, MAFF 311018 | γ-Proteobacteria | 70–73 | 4.9 | 63.7 | Plant pathogen |

| Shewanella denitrificans OS217 | γ-Proteobacteria | 70 | 4.5 | 45.1 | Marine habitat, not associated with a host |

| Yersinia pestis KIM, Nepal516, CO92, 91001, Antiqua | γ-Proteobacteria | 61–66 | 4.5–4.7 | 47.6–47.7 | Multiple habitats, pathogen, survives in macrophages |

| Mycobacterium bovis AF2122–97 | Actinobacteria | 61 | 4.3 | 65.6 | Host associated, survives in macrophages, slow growth in culture |

| Sodalis glossinidius str. morsitans | γ-Proteobacteria | 61 | 4.2 | 54.7 | Host associated, endosymbiont of tsetse flies |

List of prokaryotic genomes with ≥60 LSSR5–11. See Table 3 legend.

We used Fisher's exact test to evaluate statistical significance of the differences between the collections of genomes with high LSSR1–4 and LSSR5–11 counts (Tables 3 and 4, respectively) in terms of genome size (>4 MB versus <3 MB), G+C content (>55% versus <45%), and ability to grow outside the host. To reduce bias resulting from some genera being represented by multiple species, we counted only one species per genus in each collection. The differences were statistically significant with respect to genome size (P = 0.006) and dependence on a host (P = 0.017) but not with respect to G+C content (P = 0.11). When counting all species, the relevant probabilities are 10−5 for genome size, 0.001 for dependence on a host, and 0.0008 for G+C content. The statistical analysis is described in detail in the SI Text.

SSRs in Selected Genomes.

Lawsonia intracellularis.

This obligate intracellular parasite of domestic animals features three long mononucleotide SSRs, four long dinucleotide SSRs, and 27 long trinucleotide SSRs (Fig. 2 and SI Table 6). The N2(l) plot (dinucleotide SSRs) shows a peak around the length 15 bp, preceded by low SSR counts ≈10 bp in length. Likewise, the counts of trinucleotide SSRs decrease in agreement with the random models up to the length 15, followed by a sudden increase at length 16 (Fig. 2). These bimodal distributions resemble SSRs in some Mycoplasma species (20) and suggest that the LSSRs in L. intracellularis may be maintained by selection. By contrast, the genomes of nonpathogenic Desulfovibrio vulgaris and Desulfovibrio desulfuricans, phylogenetically close to L. intracellularis (22), contain no LSSR1–4 and few LSSR5–11 (SI Table 5 and SI Fig. 4). The mono- and dinucleotide LSSRs are exclusively intergenic, whereas trinucleotide SSRs are mostly in genes. The LSSRs in L. intracellularis are located near genes of diverse functions including many hypothetical genes (SI Table 6).

Fig. 2.

Mono- (Top), di- (Middle), and tri- (Bottom) nucleotide SSRs in L. intracellularis. See Fig. 1 legend.

Burkholderia species.

Burkholderia are found in a wide range of environmental niches and include host-adapted pathogens (B. mallei), opportunistic pathogens (B. pseudomallei) as well as nonpathogens such as some strains of B. thailandensis (23–25). Their genomes generally comprise two or three chromosomes of ≈4, 3, and 1 Mb in length, respectively. Our data confirm the abundance of LSSRs previously reported in B. mallei (25). In fact, all Burkholderia genomes contain LSSRs, but the counts vary from a moderate 53 in B. cenocepacia to nearly 700 in the two B. pseudomallei strains, which is the most among the >300 prokaryotic genomes analyzed. As in most genomes with many LSSR5–11, the heptanucleotide SSRs are the most abundant excepting B. xenovorans and Burkholderia sp. 383. Interestingly, the counts of LSSRs are generally higher in chromosome 2 than in chromosome 1 (Tables 1 and 4) possibly reflecting less stringent selective constraints in the secondary chromosomes. Hexa- and nonanucleotide LSSRs show comparable counts in genes and intergenic regions whereas LSSRs of oligonucleotides whose length is not divisible by 3 are mostly confined to intergenic regions, possibly because of selection against frameshift mutations. Surprisingly, the two strains of B. pseudomallei, K96243 and 1710b, have similar overall counts of SSRs but differ in their distribution between genes and intergenic regions with many more intergenic SSRs in the strain K96243. We believe that this discrepancy could be due to differences in gene annotations and may not have biological roots. The LSSR5–11 in the Burkholderia genomes include repeats of many different oligonucleotides, and it is unlikely that the SSRs arose by amplification of a single or few seed SSRs. The LSSR5–11 tend to be G+C rich in parallel with the high overall genomic G+C content ≈68% (SI Table 7).

Methanosarcinaspecies.

Methanosarcina species are strictly anaerobic, mesophilic, archaeal methanogens. All three Methanosarcina genomes feature multiple LSSRs, mostly LSSR5–11 with particularly high counts of 10-mer and 11-mer LSSR (SI Table 5). M. mazei and M. barkeri also have multiple LSSR1–4. Moreover, some of the tri- and tetranucleotide LSSRs in both M. mazei and M. barkeri genomes are very long, exceeding 50 bp in length. All trinucleotide LSSRs in both genomes are of the type (TAA)n or the inverted complement (TTA)n except one (AAG)7 repeat in M. mazei. Likewise, the tetranucleotide LSSRs are mostly repeats of tetranucleotides AAAT/ATTT, and some AATC, TAGA, AACT, AAGT, and AATG (SI Table 8). Several LSSR in M. mazei and M. barkeri exceed 50 bp in length and appear unlikely to be generated solely by mutational drift (Fig. 2). However, the SSRs that modulate gene expression are typically located in upstream regulatory regions or in genes where they cause frameshift mutations (1, 4), whereas the very long LSSR1–4 in Methanosarcina are located between convergent genes, downstream of genes, and some trinucleotide SSRs are in genes but these do not cause frameshifts (SI Table 8). Such locations argue against a direct role of these SSRs in gene regulation although they may have an indirect effect, e.g., by affecting properties of the DNA molecule or the encoded protein.

Discussion

Diversity of SSR Representations in Prokaryotic Genomes.

Representations of SSRs in prokaryotic genomes have been assessed in several studies. Field and Wills (19) analyzed SSR occurrences in several complete genomes and summarized the trends in prokaryotes as overrepresentation of short SSRs (up to the length of 7–8 bp for mononucleotide SSRs, k = 1) and active selection against long SSRs except where they promote reversible mutations affecting specific genes (typically those encoding surface antigens in pathogens) (4, 7). These results were confirmed by others (2, 5). By contrast, we found that the perceived overrepresentation of short SSRs can mostly be explained by models that take into account the nearest neighbor associations, which likely result from mutational biases and/or selective constraints unrelated to the SSRs (26) (SI Fig. 4). Some Mycoplasma genomes exhibit overrepresentations of mononucleotide SSRs of lengths 4–7 bp (20), but this not common in other prokaryotic genomes.

SSR representations in most prokaryotic genomes exhibit few deviations from random models. One general exception is a sharp decline in mononucleotide SSRs beyond the length of 8 bp, which is common among prokaryotes and applies to both genes and intergenic regions (20). For example, the only other deviation in the Escherichia coli K12 genome relates to two very long octanucleotide SSRs of exactly 52 bp in length, but both are located in prophage regions and are probably not native to the E. coli genome. However, prokaryotic genomes vary significantly in terms of LSSR content and some feature many LSSRs unlikely to occur by chance. Specifically, 50% of the 378 prokaryotic chromosomes analyzed contain <7 LSSRs (SI Table 5), whereas the Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413 chromosome contains 502 long SSRs, and >700 are present in the B. pseudomallei genome (both chromosomes). Note that the general scarcity of LSSRs does not mean that SSRs are underrepresented (i.e., less frequent than expected) because the cutoff is set such that no LSSRs are expected to be found. Abundance of LSSRs in some genomes is not related to taxonomy or phylogeny and differs significantly even among closely related species. Although shorter SSRs are also variable in length and may play roles in physiology and/or evolution (3, 4, 8, 20, 27), our approach, centering on LSSRs, is suitable for comparisons of SSR representations among different genomes.

Differences Between LSSR5–11 and LSSR1–4.

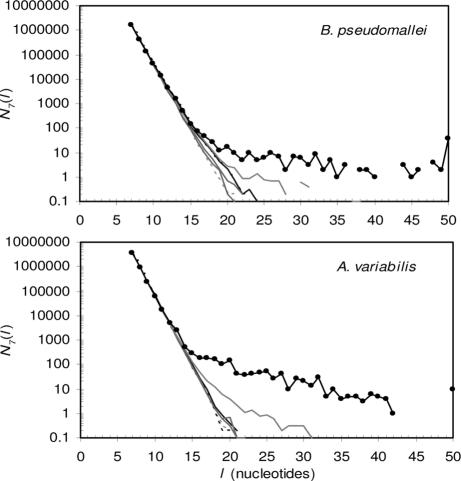

Based on our data, we hypothesize that LSSR1–4 and LSSR5–11 may arise by different mechanisms. Several pieces of evidence support this hypothesis. First, the LSSR counts Nk* correlate well across different genomes among LSSR5–11. Weaker correlations also occur among the LSSR1–4 counts but no significant correlations are observed between the two classes of LSSRs (Table 2). Second, the two classes of LSSRs tend to occur in different types of organisms. Multiple LSSR1–4 are rare and mostly found in Mycoplasma and several other host-adapted pathogens with reduced genomes (mostly <2 Mb) and low G+C content whereas LSSR5–11 occur in a diverse collection of pathogens and environmental organisms with large genomes and mostly high G+C content (Tables 3 and 4). Moreover, the Nk(l) plots for LSSR1–4 and LSSR5–11 often have different shapes. For LSSR1–4 (k ≤ 4), the plots are often discontinuous and/or bimodal, initially following the random models or dropping below the expected counts but featuring a separate peak or a flat tail of longer than expected SSRs (Fig. 2, ref. 20, and SI Fig. 4). The discontinuity suggests that most SSRs in the separate peak may be functionally relevant and maintained by selection, whereas shorter SSRs are either unaffected by selection or subject to negative selection. By contrast, the Nk(l) plots for LSSR5–11 (k ≥ 5) tend to gradually deviate from the expected counts and feature convex tails or linear tails of a lower slope (Fig. 3 and SI Fig. 4). This observation is consistent with a general tendency of the SSRs to expand when they reach some critical length. The LSSR5–11 counts start to deviate from the random models at lengths just exceeding 2k (double the length of the repeated oligonucleotide), suggesting that two full tandem copies of an oligonucleotide are sufficient for the SSR to expand. It is possible that most LSSR5–11 are generated by mutational drift in absence of negative selection. Slip-strand mutations may lead to both expansion and contraction of an SSR, and the shape of the Nk(l) plots for LSSR5–11 is consistent with a model where SSRs expand more frequently that they contract. Along these lines, many SSR-containing DNA fragments did expand during PCR amplification, although the expansion was sequence-dependent and did not apply to all SSRs (28). Interestingly, A+T-rich SSRs were generally more likely to expand in these PCR experiments, seemingly contradicting our observation that LSSR5–11 are more common in G+C-rich genomes. However, large genomes tend to be G+C rich, and the weak correlation between LSSR5–11 counts and G+C content may arise as an artifact of correlations of both with the genome size.

Fig. 3.

Heptanucleotide SSRs in B. pseudomallei (Upper) K96243chromosome 2 and in Anabaena variabilis (Lower). See Fig. 1 legend. SSRs exceeding a length of 50 bp are reported at l = 50 bp.

Mutations resulting in SSR expansion or contraction can be introduced during various cellular processes affecting the DNA, including replication, recombination and different repair mechanisms (29). There is little known about differences in precise functioning of these processes among different prokaryotes and we can only speculate as to why the LSSR5–11 expand in some genomes but not in most. Presumably, two prerequisites have to exist to facilitate the LSSR5–11 expansion: (i) a mutational bias promoting expansion of the LSSR5–11 and (ii) a lack of strong negative selection against the LSSR5–11. The latter is consistent with LSSR5–11 not being found in small genomes where the constraints against expansion may be stronger. However, some large genomes (e.g., Myxococcus xanthus) also lack LSSRs. The differences in LSSR5–11 representations may reflect differences in replication and repair machineries among different prokaryotes.

LSSR1–4 in Pathogens.

There are several well documented examples where LSSR1–4 influence gene activity by reversible mutations (27, 30–33). In pathogens, such SSRs can help counteract the host immune response and often affect families of genes encoding surface antigens (4, 5). The fact that LSSR1–4 are often found in host-adapted pathogens, which depend on the ability to avoid the host immune response to a larger degree than opportunistic pathogens, is consistent with a possible role of these SSRs in pathogen-host interactions. However, perhaps contrary to intuitive expectations, and even in pathogens where such regulation is known or thought to take place, many or even most LSSRs are not located proximal to genes encoding surface antigens (1, 8, 20) (see also SI Table 6). The effect of some SSRs on surface antigens might be indirect and facilitated by actions of other proteins (8) or possibly by alterations of DNA or protein structural properties.

Benefits of SSRs in pathogens depend on the degree to which the pathogen is exposed to the immune system of the host and on availability of other strategies to avoid the host immune response. Hence, it is not surprising that many LSSR1–4 are found in Mycoplasma, which are mostly believed to be extracellular and therefore exposed to the host immune system, although some Mycoplasma can enter the host cells (27, 30, 31, 33) (Tables 3 and SI Table 9). Note that several Mycoplasma (e.g., M. penetrans, M. mobile, M. pneumoniae) have few or no LSSR and the differences in SSR representations among Mycoplasma could relate to differences in how they interact with the host (20). In a consistent manner, Mycobacterium leprae features 16 LSSR1–4, whereas all other mycobacteria have no more than one (SI Table 5). M. leprae is a host-adapted pathogen that has not been successfully cultivated outside a host, and its genome size and G+C content are reduced compared with closely related mycobacteria (34). Interestingly, L. intracellularis, which has the second-highest count of LSSR1–4 among the genomes analyzed in this work, is intracellular. In contrast, the genomes of other obligate intracellular pathogens, such as Chlamydia or Rickettsia, contain virtually no LSSRs of any kind (SI Table 5). Likewise, obligate intracellular endosymbionts with reduced genomes do not contain LSSRs. L. intracellularis causes proliferative enteropathy in the infected animals. The bacteria reside in the host cells after colonization but little is known about the early stages of the infection, including colonization, cell adhesion, and cell entry (35). We speculate that differences in the early stages of infection between L. intracellularis and other intracellular pathogens may require effective defense mechanisms in L. intracellularis facilitated by the LSSR1–4. Unlike L. intracellularis, chlamydiae undergo a developmental cycle involving two distinct cell types: reticular bodies and elementary bodies. The reticular bodies are found strictly in vacuoles in the host cells. Outside the host cells, chlamydiae persist as metabolically dormant and physically resilient elementary bodies (36). Perhaps the chlamydial developmental cycle and lack of metabolic activity of the extracellular elementary bodies renders the increased antigenic variance facilitated by LSSR1–4 less important.

High Counts of Heptanucleotide LSSRs.

In most prokaryotes with LSSRs, heptanucleotide LSSRs are significantly more abundant than other LSSR types (Table 1 and SI Table 5). It is feasible that the structural characteristics of DNA polymerases and/or their interactions with the DNA may promote polymerase slippage specifically in heptanucleotide repeats and to a lesser extent in hexa-, octa-, and nonanucleotide repeats. Unfortunately, relevant experimental data are scarce. Analogies can be drawn from protein–DNA interactions involving distantly related enzymes. For example, during DNA repair by human polymerase β, 6 base pairs of template-primer can tether into a flexible single-stranded DNA gap, which covers ≈6–7 bp (37). Likewise, E. coli DNA endonuclease VIII interacts with the 7- to 9-bp central region of DNA (38). It is possible that the preferred 7-bp length of oligonucleotides involved in long SSRs is related to the length of the DNA segment that interacts with the active site of the polymerase.

Materials and Methods

DNA Sequences.

Annotated sequences of complete prokaryotic genomes were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information ftp server ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Bacteria/. Each replicon (chromosome or plasmid) was analyzed separately. We relied on the existing annotation (the “CDS” features) in differentiating protein-coding and noncoding regions.

Simple Sequence Repeats.

SSRs consist of tandem iterations of an oligonucleotide in a DNA sequence. We measure the length of an SSR in nucleotides (bp) rather than the number of repetitive units, which allows accounting for partial copies and facilitates comparisons among SSRs of different lengths.

Definition.

An SSR of length l composed of iterations of a k-mer starts at the position i in a sequence of nucleotides if xj = xj+k for all j ≥ i, j ≤ i + l − k − 1 and simultaneously xi−1 ≠ xi−1+k and xi+l−k ≠ xi+l.

This definition can be applied to all SSRs of length l ≥ k. Repeats of a longer oligonucleotide that also qualify as repeats of a shorter oligonucleotide are only counted as the shorter oligonucleotide SSR. We analyze the SSR counts N in a given genome as a function of k and l, and we refer to the SSR counts as Nk(l).

Statistical Assessments of SSR Representations.

We employ two different approaches in assessing over- or underrepresentation of SSRs in a DNA sequence: (i) We use multiple stochastic models of varying complexity, which provide an expected range of counts serving as a null hypothesis (20). (ii) The functions Nk(l) are expected to decrease exponentially under homogeneous models. Hence, deviations from exponential dependence may signal over- or underrepresentation of SSRs of the type k and a particular range of lengths l.

Random Sequence Models.

Homogeneous Bernoulli or Markov models are often used in analyses of DNA sequences whereas real DNA sequences are intrinsically inhomogeneous (39–41). We use a combination of 11 previously described models (20) that reproduce different properties of the DNA sequence (SI Table 9). Heterogeneous models were constructed by dividing the original sequence into segments corresponding to individual genes and intergenic regions, generating a random sequence corresponding to each segment with a homogeneous model (Bernoulli, Markov, or periodic Markov), and finally reassembling the segments into a contiguous randomized genome. This procedure reproduces sequence heterogeneity at the scale of individual genes and, depending on the models used, nearest-neighbor associations, codon frequencies, and/or the periodic character of protein-coding sequences. The expected SSR counts for each model were estimated from simulations. Ten random sequences were generated by each model, the counts were averaged over the 10 simulations, and the results with different models provides a range of expected counts Nk(l) (see Figs. 1–3 and SI Fig. 4). A program to generate random sequences by the 11 models is available for download at www.cmbl.uga.edu/software.html.

Definition of Long SSRs.

The Nk(l) representation of SSR counts is impractical for comparisons of hundreds of different genomes. To simplify the representation, we only report counts of LSSRs unlikely to occur by chance. This reduces the Nk(l) representation to k numbers Nk* for each genome, which signify the counts of SSRs of the type k that exceed a given cutoff Lk. The cutoff Lk is derived from the “m1c1” random model (SI Table 9), which reproduces the dinucleotide frequencies for each intergenic region and codon frequencies and nearest-neighbor associations for each gene of the genome. First, we find the largest length lk(0) such that the expected SSR count based on the m1c1 model Nkm1c1(lk(0)) ≥ 1. The cutoff is set as Lk = lk(0) + 4. The increase by 4 bp is arbitrary, and it is based on our observation that longer SSRs are rare in most genomes. The Nk* representation is suitable for comparisons among different genomes while taking into account specific characteristics of each genome. Pattern Locator (42) was used in the analysis of LSSR distribution with respect to annotated genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Ishla Seager for help in the initial stages of this project and Drs. Larry Shimkets and Mark Schell for comments on the manuscript and stimulating discussions.

Abbreviations

- SSR

simple sequence repeat

- LSSR

“long” SSR (see Methods for definition)

- LSSR1–4

LSSR composed of iterations of 1-mer to 4-mer

- LSSR5–11

LSSR composed of iterations of 5-mer to 11-mer.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Mrázek, J., Kypr, J. (1994) Miami Biotechnol Short Rep 5:39.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0702412104/DC1.

References

- 1.Karlin S, Mrázek J, Campbell AM. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4263–4272. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.21.4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kashi Y, King DG. Trends Genet. 2006;22:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metzgar D, Thomas E, Davis C, Field D, Wills C. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:183–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moxon ER, Rainey PB, Nowak MA, Lenski RE. Curr Biol. 1994;4:24–33. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocha EP. Genome Res. 2003;13:1123–1132. doi: 10.1101/gr.966203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tautz D, Schlötterer C. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:832–837. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groisman EA, Casadesus J. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocha EP, Blanchard A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2031–2042. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Htun H, Dahlberg JE. Science. 1989;243:1571–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.2648571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordheim A, Rich A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1821–1825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.7.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shafer RH, Smirnov I. Biopolymers. 2000;56:209–227. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000/2001)56:3<209::AID-BIP10018>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Holde K, Zlatanova J. BioEssays. 1994;16:59–68. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunker AK, Cortese MS, Romero P, Iakoucheva LM, Uversky VN. FEBS J. 2005;272:5129–5148. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perutz MF, Pope BJ, Owen D, Wanker EE, Scherzinger E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5596–5600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042681599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karlin S, Brocchieri L, Bergman A, Mrázek J, Gentles AJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:333–338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012608599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timchenko LT, Caskey CT. FASEB J. 1996;10:1589–1597. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.14.9002550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matula M, Kypr J. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1999;17:275–280. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1999.10508360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tóth G, Gáspári Z, Jurka J. Genome Res. 2000;10:967–981. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field D, Wills C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1647–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mrázek J. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1370–1385. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msk023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gur-Arie R, Cohen CJ, Eitan Y, Shelef L, Hallerman EM, Kashi Y. Genome Res. 2000;10:62–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebhart CJ, Barns SM, McOrist S, Lin GF, Lawson GH. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:533–538. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-3-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holden MT, Titball RW, Peacock SJ, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Atkins T, Crossman LC, Pitt T, Churcher C, Mungall K, Bentley SD, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14240–14245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403302101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HS, Schell MA, Yu Y, Ulrich RL, Sarria SH, Nierman WC, DeShazer D. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nierman WC, DeShazer D, Kim HS, Tettelin H, Nelson KE, Feldblyum T, Ulrich RL, Ronning CM, Brinkac LM, Daugherty SC, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14246–14251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403306101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karlin S, Mrázek J, Campbell AM. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3899–3913. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3899-3913.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willems R, Paul A, van der Heide HG, ter Avest AR, Mooi FR. EMBO J. 1990;9:2803–2809. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vondrušková J, Pařízková N, Kypr J. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2007;26:65–82. doi: 10.1080/15257770601052299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bichara M, Wagner J, Lambert IB. Mutat Res. 2006;598:144–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glew MD, Baseggio N, Markham PF, Browning GF, Walker ID. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5833–5841. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5833-5841.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hood DW, Deadman ME, Jennings MP, Bisercic M, Fleischmann RD, Venter JC, Moxon ER. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11121–11125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stern A, Brown M, Nickel P, Meyer TF. Cell. 1986;47:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90366-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wassenaar TM, Wagenaar JA, Rigter A, Fearnley C, Newell DG, Duim B. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;212:77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith DG, Lawson GH. Vet Microbiol. 2001;82:331–345. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(01)00397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cole ST, Eiglmeier K, Parkhill J, James KD, Thomson NR, Wheeler PR, Honore N, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, et al. Vet Microbiol. 2001;82:331–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rockey DD, Matsumoto A. In: Prokaryotic Development. Brun YV, Shimkets LJ, editors. Washington, DC: Am Soc Microbiol Press; 1999. pp. 403–425. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pelletier H, Sawaya MR, Wolfle W, Wilson SH, Kraut J. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12742–12761. doi: 10.1021/bi952955d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zharkov DO, Golan G, Gilboa R, Fernandes AS, Gerchman SE, Kycia JH, Rieger RA, Grollman AP, Shoham G. EMBO J. 2002;21:789–800. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fickett JW, Torney DC, Wolf DR. Genomics. 1992;13:1056–1064. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90019-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karlin S, Blaisdell BE, Sapolsky RJ, Cardon L, Burge C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:703–711. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larhammar D, Chatzidimitriou-Dreismann CA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5167–5170. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.22.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mrázek J, Xie S. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:3099–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.