Abstract

L-type Ca2+ currents determine the shape of cardiac action potentials (AP) and the magnitude of the myoplasmic Ca2+ signal, which regulates the contraction force. The auxiliary Ca2+ channel subunits α2δ-1 and β2 are important regulators of membrane expression and current properties of the cardiac Ca2+ channel (CaV1.2). However, their role in cardiac excitation–contraction coupling is still elusive. Here we addressed this question by combining siRNA knockdown of the α2δ-1 subunit in a muscle expression system with simulation of APs and Ca2+ transients by using a quantitative computer model of ventricular myocytes. Reconstitution of dysgenic muscle cells with CaV1.2 (GFP-α1C) recapitulates key properties of cardiac excitation–contraction coupling. Concomitant depletion of the α2δ-1 subunit did not perturb membrane expression or targeting of the pore-forming GFP-α1C subunit into junctions between the outer membrane and the sarcoplasmic reticulum. However, α2δ-1 depletion shifted the voltage dependence of Ca2+ current activation by 9 mV to more positive potentials, and it slowed down activation and inactivation kinetics approximately 2-fold. Computer modeling revealed that the altered voltage dependence and current kinetics exert opposing effects on the function of ventricular myocytes that in total cause a 60% prolongation of the AP and a 2-fold increase of the myoplasmic Ca2+ concentration during each contraction. Thus, the Ca2+ channel α2δ-1 subunit is not essential for normal Ca2+ channel targeting in muscle but is a key determinant of normal excitation and contraction of cardiac muscle cells, and a reduction of α2δ-1 function is predicted to severely perturb normal heart function.

Keywords: calcium, heart, action potential, dysgenic myotube

L-type Ca2+ currents occupy a key position for normal function and dysfunction of the heart. They contribute to the shape and duration of the cardiac action potential (AP) and to the cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients, which activate contraction. Mutations in the cardiac voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (CaV1.2) cause long QT syndrome and life-threatening arrhythmias (1, 2), and the Ca2+ channels are critical mediators of both the therapeutic actions and undesirable side effects of frequently used drugs (3).

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are composed of a pore-forming α1 subunit and auxiliary α2δ, β, and γ subunits. The auxiliary subunits determine the expression levels and biophysical properties of the channels and thus participate in the central role of the Ca2+ channel in cardiac excitation–contraction (EC) coupling. The importance of these subunits is underscored by the fact that attempts to generate knockout mice of the specific cardiac isoforms resulted in embryonic lethal phenotypes because of cardiac dysfunction (4, 5) (J. Offord, personal communication). Besides showing the essential role of the auxiliary channel subunits, the lack of viable knockout models hampered the analysis of their specific roles in shaping the cardiac AP and Ca2+ transients.

The α2δ subunit is a product of a single gene that is posttranslationally cleaved into α2 and δ peptides, which remain coupled via disulfide bonds. The δ subunit is a single-pass membrane protein and the α2 subunit is a highly glycosylated extracellular protein (6). A total of four genes code for α2δ subunits (α2δ-1 through α2δ-4), which display distinct tissue distributions (7). The α2δ-1 isoform is the major isoform in cardiac muscle. In addition, α2δ-1 is expressed at high levels in skeletal and vascular smooth muscle and in the brain, where it can also associate with different α1 subunit isoforms. Finally, α2δ-1 is the prime target for the anticonvulsant drugs gabapentin and pregabalin, two highly effective agents to medicate neuropathic pain (8, 9).

Coexpression of α2δ subunits with various α1 subunits in heterologous expression systems demonstrated that α2δ increases the number of ligand binding sites, enhances the membrane expression of functional Ca2+ channels, and alters the voltage dependence and kinetics of the Ca2+ currents (6). Interestingly, the extracellular α2 conveys the effects of increased membrane expression, whereas the δ peptide is sufficient for the modulation of current properties (10). The manifestation and the magnitude of these multiple effects vary with the combination of α1 and α2δ isoforms expressed in heterologous systems. However, so far the consequences of lost or altered α2δ-1 functions in the heart are elusive.

Homozygous dysgenic muscle cells specifically lack the Ca2+ channel α1S subunit and can readily be reconstituted by transfection with recombinant Ca2+ channels. Because skeletal and cardiac muscle cells share many molecular and structural properties, transfection with the cardiac CaV1.2 α1C subunit results in an EC coupling apparatus with cardiac properties (11–13). Here we use this unique muscle expression system in combination with computer modeling of ventricular myocyte function to analyze the role of the α2δ-1 subunit on cardiac-type EC coupling. Knockdown of α2δ-1 expression by siRNA did not perturb normal expression and targeting of CaV1.2 but altered the voltage dependence of activation and the current kinetics, indicating that α2δ-1 is a major determinant of L-type Ca2+ channel properties. Computer simulation predicted that a similar loss of α2δ-1 function in cardiac myocytes would give rise to prolonged cardiac APs and increased Ca2+ transients similar to those observed in cardiac arrhythmias caused by mutations in the CaV1.2 gene (1, 2).

Results

To study how the loss of function of the α2δ-1 subunit affects the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel in an environment similar to that of cardiac myocytes, we used siRNA gene silencing in the dysgenic muscle expression system reconstituted with cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. Whereas, to date, siRNA knockdown of channel proteins in differentiated cardiac myocytes is not feasible, dysgenic myotubes can be readily transfected and maintained in culture long enough to allow efficient siRNA depletion of α2δ-1 (14). In these α1S-null mutant muscle cells, the heterologous cardiac CaV1.2 α1C subunit associates with the endogenous α2δ-1 and β1a subunits and functionally incorporates in the EC coupling apparatus. Previous studies demonstrated cardiac characteristics of the structural organization of the channels in the junctions, the current properties, and the mechanism of EC coupling via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (11–13). Thus, in contrast to coexpression studies in heterologous cells, this expression system will reveal possible effects of α2δ-1 knockdown on targeting and functional incorporation of the channel into the EC coupling apparatus.

Coexpression of GFP-α1C and α2δ-1 siRNA Depletes the α2δ-1 Subunit Without Affecting Functional Expression and Targeting of GFP-α1C.

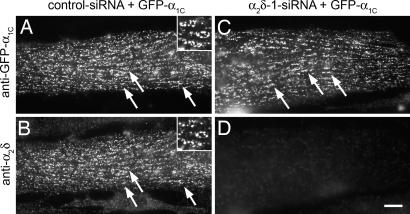

Previously we developed and characterized expression plasmids coding for short hairpin RNAs against specific sequences of α2δ-1 (14). Dysgenic myoblasts were cotransfected with GFP-α1C plus α2δ-1 or control siRNA plasmids at the onset of fusion and were analyzed 4 days later, which resulted in the expression of the heterologous channel in parallel with depletion of the endogenous α2δ-1 subunit. The GFP-tagged α1C enabled us to identify and select transfected myotubes in living cultures for the patch-clamp experiments, and it facilitated the analysis of channel targeting. Double immunofluorescence labeling of GFP-α1C and α2δ-1 in control myotubes showed that both Ca2+ channel subunits were colocalized in clusters corresponding to plasma membrane/sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and transverse (T)-tubule/SR junctions (Fig. 1 A and B) (11, 13). In myotubes transfected with α2δ-1 siRNA, expression of α2δ-1 mRNA and protein was suppressed to below 20% (14). With immunocytochemistry, α2δ-1 knockdown was evident in 90% of the transfected myotubes, and α2δ-1 levels were entirely below delectability in >50% of the transfected myotubes (14). Interestingly, even in the absence of α2δ-1, the GFP-α1C subunit was efficiently expressed and normally localized in clusters (Fig. 1 C and D). Also, electric field stimulation triggered AP-induced Ca2+ transients in α2δ-1 and control siRNA transfected cultures (data not shown). Thus, the lack of α2δ-1 did not interfere with the normal expression and functional targeting of the α1C subunit into the EC coupling apparatus.

Fig. 1.

siRNA knockdown of α2δ-1 does not perturb triad targeting of GFP-α1C. Dysgenic myotubes were cotransfected with GFP-α1C and either control or α2δ-1 siRNA. (A and B) Immunofluorescence labeling of control myotubes shows GFP-α1C colocalized with endogenous α2δ-1 in clusters. Examples are indicated by arrows and in the 2.5-fold-magnified Inset. (C and D) Coexpression of α2δ-1 siRNA caused a robust depletion of the α2δ-1 subunit (D) without affecting expression and targeting of GFP-α1C (C). (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

Depletion of α2δ-1 Changes the Voltage Dependence and Kinetics of Cardiac Muscle L-Type Ca2+ Currents.

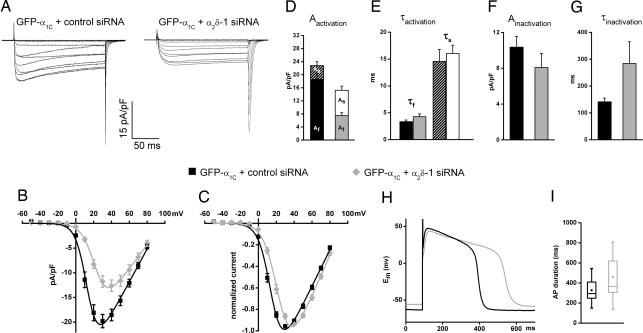

Because in the absence of α2δ-1 the pore-forming GFP-α1C subunit was still functionally incorporated into the junctions, the effects of α2δ-1-depletion on the properties of cardiac L-type currents could be analyzed using voltage-clamp recordings. Representative current traces in response to depolarizing test pulses show the effects of α2δ-1 siRNA-depletion on current amplitude and kinetics (Fig. 2 A and B). Compared with the control (Fig. 2A Left), Ca2+ currents in α2δ-1 siRNA-transfected myotubes (Fig. 2A Right) activate more slowly, peak at lower current densities, and show little inactivation during the 200-ms test pulse. Moreover, normalized current-to-voltage curves (Fig. 2C) demonstrate a statistically significant 9-mV shift toward more positive potentials in the voltage-dependence of activation (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

siRNA depletion of α2δ-1 changes current kinetics and voltage dependence of cardiac L-type Ca2+ currents and AP duration. (A) Representative current traces in response to 200-ms test pulses to voltages between −50 and +80 mV in 10-mV increments recorded from dysgenic myotubes cotransfected with GFP-α1C and either control or α2δ-1-siRNA. (B and C) Current-to-voltage curves show that, in myotubes expressing α2δ-1 siRNA, the peak current amplitude is reduced by 36% (B) and that the voltage-dependence of activation is shifted by +9 mV (P < 0.0001) (C). Fitting the current traces with a triple exponential function reveals two components of activation and one of inactivation. (D and E) Depletion of α2δ-1 increases the contribution of the slow activation component without changing its specific time constant. (F and G) The third kinetic component reveals that α2δ-1 depletion doubles the time constant of inactivation. (H) Current clamp recordings in GFP-α1C + control siRNA expressing dysgenic myotubes reveal APs with cardiac shape. In α2δ-1-depleted myotubes (gray trace) the duration of the AP plateau is significantly prolonged. (I) In the box plots, the boxes contain 50% and the vertical bars 99% of data points; central dots represent the mean; horizontal lines represent the median; asterisks represent extreme values. Error bars represent the SEM.

Table 1.

Properties of α1C Ca2+ currents from control- and α2δ-1-siRNA-transfected myotubes

| Property | Parameters | GFP-α1C + |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control-siRNA | a2δ-1-siRNA | Significance (P value) | ||

| Activation | Ipeak (pA/pF) | −21.1 ± 1.5 | −13.5 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Gmax (nS/nF) | 360.3 ± 24.5 | 278.9 ± 26.1 | 0.02 | |

| V0.5 (mV) | 15.7 ± 1.2 | 24.7 ± 1.3 | <0.001 | |

| Kactivation (mV) | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | ns | |

| Vrev (mV) | 93.5 ± 1.1 | 93.4 ± 1.1 | ns | |

| n | 30 | 34 | — | |

| Kinetics | Afast contribution | 80% | 54% | <0.001 |

| Aslow contribution | 20% | 46% | <0.001 | |

| τfast(ms) | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | ns | |

| τslow(ms) | 14.5 ± 2.2 | 16.1 ± 1.5 | ns | |

| Ainactivation (pA/pF) | −10.3 ± 1.2 | −8.1 ± 1.6 | ns | |

| τinactivation (ms) | 141.3 ± 13.7 | 284 ± 81.1 | ns | |

| R200 | 37.3 ± 3.0 | 21.9 ± 1.6 | <0.001 | |

| n | 30 | 33 | — | |

| AP | Duration (ms) | 327.9 ± 30.1 | 458.8 ± 54.5 | 0.04 |

| n | 14 | 14 | ||

| QON vs ITail | QON (nC/μF) | 13.2 ± 1.5 | 9.5 ± 0.9 | 0.04 |

| ITail (pA/pF) | −76.8 ± 12.5 | −50.2 ± 5.7 | 0.05 | |

| Slope | 6.02 | 4.91 | — | |

| Correlation significance (p) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | — | |

| n | 23 | 25 | — | |

| Steady-state inactivation | V0.5 (mV) | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 3.2 ± 1.8 | ns |

| Kinactivation (mV) | 9.6 ± 1.3 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | ns | |

| n | 13 | 12 | — | |

| Recovery from inactivation | Rate (s) | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | ns |

| n | 9 | 10 | — | |

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Students t test. ns, not significant.

Fitting the maximum current sweep with a triple-exponential function revealed two activation components and one inactivation component. In the control, the fast activating current component dominated with 80%:20% over the slowly activating component (Fig. 2D). Whereas depletion of α2δ-1 did not alter the time constants of either activating components (Fig. 2E and Table 1), their ratio was dramatically shifted so that in the α2δ-1-depleted group, the contributions of both components were approximately equal (Fig. 2D and Table 1). The third kinetic component describes the inactivating phase of the Ca2+ currents. In the α2δ-1 siRNA group, the time constant of inactivation was doubled, and the ratio of inactivation at the end of the 200-ms pulse (R200) was significantly decreased compared with the control siRNA group (Fig. 2G and Table 1). Slowed inactivation could either represent another direct effect of α2δ-1 depletion or it could result indirectly from reduced Ca2+-induced inactivation at reduced current amplitudes. The latter however, seems unlikely, because slowed inactivation kinetics were also observed when comparing pairs of currents with matched peak amplitudes (data not shown), where the contribution of Ca2+-induced inactivation should be equal for the α2δ-1 siRNA and control sample. Thus, depletion of α2δ-1 from cardiac Ca2+ channels makes channel gating less responsive to depolarization and slows down the kinetics of activation and inactivation.

Next we analyzed steady-state inactivation and recovery from inactivation. In contrast to the effects of α2δ-1 depletion on the voltage dependence of activation, the voltage dependence and the degree of the steady-state inactivation during 4 second prepulses were not altered [supporting information (SI) Methods and SI Fig. 5]. However, the rate of recovery from inactivation was reduced by α2δ-1 depletion by one-third (Table 1, SI Methods, and SI Fig. 5). A reduced recovery from inactivation may limit Ca2+ entry during repetitive stimulation. Together with the observed effects on inactivation kinetics (Fig. 2 F and G), these results indicate that depletion of α2δ-1 slows down both the rate of inactivation and the rate of recovery from inactivation but that, given enough time, the same number of channels reach the inactivated state with and without α2δ-1.

To examine whether expression of GFP-α1C reconstitutes cardiac-like APs in dysgenic myotubes, and if so, whether they are affected by α2δ-1 depletion, we performed current-clamp recordings. APs were stimulated at a rate of 0.5 Hz, and the 20th AP was analyzed. The APs showed a distinctive plateau phase similar to that of cardiac APs (Fig. 2H), although their absolute duration was considerably longer. The AP plateaus were absent in myotubes transfected with the skeletal muscle GFP-α1S (data not shown), demonstrating that they arise from the L-type Ca2+ conductance of the cardiac α1C subunit. Most importantly, in α2δ-1 siRNA-transfected myotubes, the AP duration was significantly longer (40%, P < 0.05) than in the controls (Fig. 2I and Table 1). This finding indicated that α2δ-1 is a determinant of AP duration that may be physiologically relevant in cardiac EC coupling.

Minor Effects of α2δ-1 Depletion on Functional Expression and Gating Properties of Cardiac Ca2+ Channels.

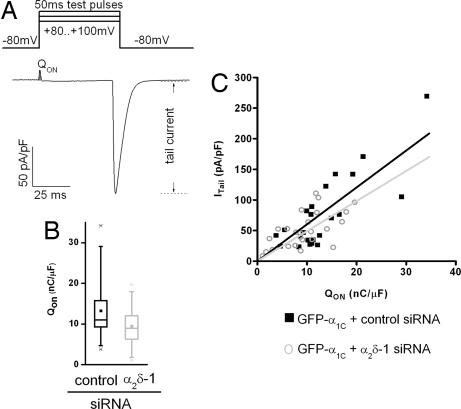

The reduced current density observed in α2δ-1-depleted myotubes (Fig. 2B) can in part be explained by the right-shifted voltage dependence because of the decreased driving force at more positive potentials. In addition, reduced current densities might result from a reduced number of functional channels in the membrane or from altered gating properties. To examine this possibility, ON-gating charges and tail currents were analyzed. Measuring the ON-gating charge (QON) at the reversal potential (Fig. 3A) provides a simple measure of the number of channels in the membrane (15, 16). In myotubes expressing α2δ-1 siRNA, QON was on average reduced by 28% (P = 0.04) compared with controls (Fig. 3B and Table 1). The amplitude of the tail current is a function of the number of channels and their open probability. The reduced slope of the linear regression of ITail vs. QON for the myotubes expressing α2δ-1 siRNA (Fig. 3C) suggests only a small contribution of altered gating properties to the observed reduction of current density.

Fig. 3.

Functional membrane expression (QON) and gating properties (PO) of CaV1.2 are reduced by depletion of α2δ-1. (A) Gating charge movement and tail currents were recorded during a 50-ms test pulse at the reversal potential. (B) In myotubes expressing GFP-α1C and α2δ-1 siRNA, QON was reduced by 28% (P = 0.04). For information regarding the box blot, see the legend to Fig. 2I. (C) Plotting the amplitude of the tail current density (ITail) against the gating charge movement (QON) reveals that depletion of α2δ-1 (gray circles) reduced the slope of a linear regression forced through zero (k = 4.91, P < 0.0001), suggesting a nearly 20% reduction of the open probability (PO) compared with channels in myotubes with normal α2δ-1 levels (k = 6.02, P < 0.0001) (control n = 23, α2δ-1-siRNA n = 25).

Computer Simulation of the Effects of α2δ-1 siRNA on Ca2+ Currents Predicts Altered Cardiac APs and Cytoplasmic Ca2+ Signals.

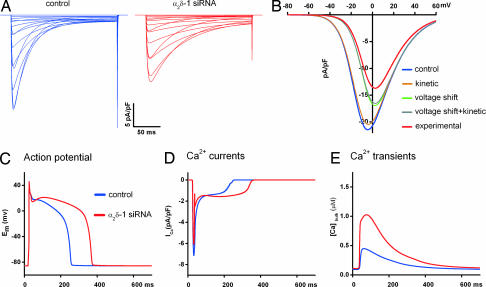

Knowing the effects of α2δ-1 depletion on cardiac Ca2+ currents, it was important to determine the possible consequences on heart function. Homozygous α2δ-1 knockout mice die during early embryonic development (J. Offord, personal communication), indicating the importance of α2δ-1 in heart function. Therefore, we used state-of-the-art computer models of mammalian ventricular myocytes (17) to simulate the effects of the altered L-type current properties induced by α2δ-1 siRNA on the AP and cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. Current parameters found to be altered by α2δ-1 depletion in the muscle expression system (see above) were modified in the model as follows (see also SI Methods): The difference in the mean values of the voltage of half-maximal activation (V0.5) was inserted as experimentally determined (Table 1). The terms describing the activation and inactivation kinetics (τd,τf) were left unaltered for the control but were multiplied by a factor corresponding to the relative change determined experimentally in the α2δ-1-depleted myotubes. Such simulated Ca2+ currents exhibited the current properties of freshly dissociated cardiac muscle cells, with faster current kinetics and left-shifted voltage dependence compared with the currents recorded in dysgenic myotubes. Nevertheless, the modeled Ca2+ currents faithfully reproduced the effects of α2δ-1 depletion observed in our muscle-expression system (Fig. 4A). Using this model, we simulated the effects of α2δ-1 depletion on the current-to-voltage relationship of each altered parameter individually (Fig. 4B). As expected because of the diminished driving force at more positive potentials, the 9-mV shift in the voltage-dependence of activation reduced the maximal current amplitude by 23% (Fig. 4B, green trace). This mechanism explains about two-thirds of the 36%-reduced current amplitude observed in our experiments (see Fig. 2B). The remaining reduction of current amplitude most likely reflects the combined contribution of reduced channel numbers and Po (see Fig. 3). To accommodate this additional effect of α2δ-1 depletion in the model, a correction factor was introduced to adjust the simulated current amplitude to the experimentally determined mean value (Fig. 4B, red trace).

Fig. 4.

Simulated effects of α2δ-1 depletion on cardiac APs and Ca2+ transients. (A) Experimentally determined effects of α2δ-1 depletion on cardiac L-type Ca2+ currents (compare Figs. 2 and 3) were simulated by introducing the relative changes of τactivation, τinactivation, voltage-dependence, and amplitude into a dynamic computer model of ventricular myocytes (see also SI Methods). (B) The simulated I–V curves show the contribution of each parameter affected by α2δ-1 depletion to the observed reduction of the current amplitude. Whereas the voltage shift contributed strongly to the reduced current amplitude, kinetic changes showed little effects. (C–E) Simulating the consequences of α2δ-1 depletion on cardiac APs, Ca2+ currents and cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration during the AP (red trace) predicts a decreased rate of repolarization during the plateau phase and a 60%-increased duration of the AP measured at AP/2. Peak [Ca2+] is predicted to increase by 123%.

Simulating the cumulative effects of α2δ-1 depletion on the AP, the Ca2+ current, and the cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentrations during an AP revealed a drastic increase in Ca2+ currents particularly in the late phase of the AP (Fig. 4D, red trace). The prolonged Ca2+ influx in turn resulted in an elevated and 60%-prolonged plateau of the cardiac AP (Fig. 4C, red trace) and a 2-fold-increased Ca2+ transient (Fig. 4E, red trace). The increase in AP duration upon α2δ-1 depletion was consistent with a similar effect observed in the current clamp recordings of the dysgenic myotubes (Fig. 2 H and I). To test the predicted effects on Ca2+ currents and transients during the AP, we performed AP voltage-clamp in dysgenic myotubes expressing GFP-α1C (SI Methods and SI Fig. 6). Depolarizing the cells with the AP shapes generated by the model resulted in an increase of the total Ca2+ influx and an increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ (integrals of current and transient, respectively), similar to those predicted by the myocyte model.

Simulating the individual current parameters affected by α2δ-1 depletion one by one revealed distinct and partially opposing contributions to the altered AP and Ca2+ transient (SI Methods and SI Fig. 7). Consistent with the fact that L-type Ca2+ currents primarily shape the plateau phase of the cardiac AP, the slowed inactivation kinetics produced a drastic prolongation of the AP. In contrast, the slowed activation kinetics was of little consequence. The shift of the voltage-dependence of activation to more positive potentials exerted small effects in the direction opposite to that of inactivation. It shortened the AP and reduced the peak of the Ca2+ transient. Thus, the reduction of the rate of inactivation is the physiologically most relevant effect of depleting CaV1.2 of α2δ-1. Altogether, computer modeling of cardiac myocyte function predicts severe consequences of α2δ-1 depletion on cardiac APs and Ca2+ handling, both of which primarily result from the slowed inactivation kinetics of L-type Ca2+ currents.

Discussion

The experiments described above demonstrate that the α2δ-1 subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels is a major determinant of cardiac L-type Ca2+ current properties and that the loss of function of α2δ-1 is predicted to result in severe effects on cardiac excitability and EC coupling. This is the first time that the role of α2δ-1 in the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel has been studied in a muscle cell, enabling us to directly analyze possible effects of α2δ-1 on functional targeting of the Ca2+ channel into the EC coupling apparatus. Myotubes in which α2δ-1 was completely depleted showed normal expression and triad targeting of the cardiac CaV1.2 α1C subunit. This finding is consistent with findings for the skeletal muscle α1S subunit (14) and clearly indicates that α2δ-1 is not essentially involved in the targeting and immobilization of the channel into the junctions between the surface membrane and sarcoplasmic reticulum. Previously we demonstrated that, in the absence of α1 subunits, α2δ-1 is misstargeted (14, 18). Thus, for proper targeting, the α2δ-1 subunit needs to associate with an α1 subunit, which contains a C-terminal triad-targeting signal (19), but α2δ-1 itself does not contribute to triad targeting of the Ca2+ channel complex.

Moreover, upon α2δ-1 depletion we observed only a modest reduction of current density, two-thirds of which could be explained by the right-shifted voltage dependence of activation. This observation indicates that in muscle cells the α2δ-1 subunit plays only a minor role in membrane expression of L-type Ca2+ channels. This finding was unexpected in light of data from heterologous cells in which coexpression of α2δ-1 resulted in severalfold increases of current amplitudes and ligand-binding sites (10, 20–22). Whereas in heterologous cells the association of auxiliary subunits frequently appears to be the limiting factor for membrane expression of Ca2+ channels, this seems to be much less the case in differentiated cells in which the channels are incorporated in complex signaling machines. Using qualitative (14) and quantitative RT-PCR (B. Schlick, G.K., B.E.F., G.J.O., unpublished results) we ruled out that other α2δ isoforms were present in amounts large enough to compensate for the lost function of α2δ-1. Thus, in the native environment of a muscle cell the importance of α2δ-1 for the functional membrane expression of Ca2+ channels is negligible.

On the contrary, depletion of α2δ-1 had substantial effects on several current properties. It resulted in a shift of the voltage dependence of activation to more positive potentials, and it slowed down activation and inactivation kinetics as well as the recovery from inactivation. The observed changes in voltage dependence and current kinetics are consistent with results from coexpression studies in heterologous cells (10, 20, 23). The modest decrease in Po deduced from the correlation of gating currents and tail currents is consistent with the decreased single channel Po observed on α1C/α2δ-1 coexpression in oocytes (24). These effects on several current properties can best be explained by a role of α2δ-1 in facilitating the transitions between channel states. In myotubes with depleted α2δ-1, Ca2+ channels require a stronger depolarization and more time to enter the open state, to go from the open into the inactivated state, and then to recover from inactivation into the closed activatable state. This interpretation is consistent with the conclusion reached by a thorough analysis of inactivating gating currents recorded in heterologous cells cotransfected with α1C/β2b with and without α2δ-1 (25). Thus, whereas major effects of α2δ-1 on membrane expression of CaV1.2 could not be confirmed in the muscle cells, the effects on biophysical channel properties are quite similar in heterologous expression systems and in muscle cells.

α2δ-1 is the major α2δ subunit isoform in both cardiac and skeletal muscle. But is its function the same in channel complexes containing CaV1.1 or CaV1.2? In both cases, (ref. 14 and this work) α2δ-1 was neither necessary for membrane expression and triad targeting of the Ca2+ channel, nor essential for EC coupling. Also, in both CaV1.1- and CaV1.2-containing channel complexes, α2δ-1 determined the characteristic Ca2+ current kinetics. Interestingly however, the effects of α2δ-1 depletion on current kinetics were opposite in dysgenic myotubes reconstituted with skeletal and cardiac α1 subunits. Here we show that depletion of α2δ-1 slowed down activation and inactivation kinetics of CaV1.2, whereas depletion of α2δ-1 from CaV1.1 accelerated current kinetics (14). Thus, the specific fast and slow current kinetics of cardiac and skeletal L-type Ca2+ channels, respectively, are intrinsic properties of the α1 subunits. However, in both cases the association with the α2δ-1 subunit is required to express these characteristic current kinetics.

In cardiac muscle, L-type Ca2+ currents determine the plateau phase of the AP and control Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Therefore, it is important to know how the altered current properties would affect these functions in cardiac myocytes. Simulation of the effects of α2δ-1 depletion in a computer model of ventricular myocytes (17) demonstrated that, compared with the control group, the AP plateau was elevated and elongated by 60% and that myoplasmic Ca2+ transients during the AP were elevated ≈2-fold. Running the simulation for each of the altered current parameters individually showed that the slowed inactivation kinetics is the major source of these effects on APs and Ca2+ transients. In contrast, the slowed activation kinetics had little influence on the AP and Ca2+ transients, and the right-shifted voltage dependence of activation partially compensated the effects of inactivation.

Interestingly the modeled consequences of α2δ-1 dysfunction on the cardiac AP and Ca2+ transients qualitatively and quantitatively resemble those reported for CaV1.2 mutants associated with Timothy disease (1, 2). These CaV1.2 gain-of-function mutations also produce noninactivating Ca2+ currents, prolonged APs and elevated Ca2+ transients. Consequently, Timothy disease patients show prolonged QT intervals in the electrocardiogram and suffer from cardiac arrhythmias. A similar phenotype would be expected for loss-of-function mutations of the α2δ-1 subunit. To date, no mutations in the α2δ-1 gene have been linked to human disease, and of the >1,700 single nucleotide polymorphisms known in the α2δ-1 gene, only a handful are located within the coding region [PolyPhen, nonsynonymous (ns)SNP prediction], suggesting that most changes in the α2δ-1 protein have deleterious effects. Nonetheless, mutations may exist that influence cardiac EC coupling within the physiological range or contribute to arrhythmias. Thus, α2δ-1 is a highly interesting candidate gene that influences the cardiac AP and Ca2+ handling, and the prediction of the cardiac phenotype in our study might be a first step to identify inherited mutations in α2δ-1 with milder effects or de novo mutations similar to those in Timothy disease.

The siRNA depletion of the Ca2+ channel α2δ-1 subunit in a muscle expression system combined with computer modeling of myocyte function revealed that α2δ-1 is an important determinant of cardiac excitability and Ca2+ handling. This innovative experimental approach offers a highly valuable and feasible strategy for analyzing the role of proteins critically involved in cardiac function, in particular in those cases where a vital role of the protein precludes its analysis with classical knockout approaches.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Transfections.

Myotubes of the homozygous dysgenic (mdg/mdg) cell line GLT were cultured as described in ref. 26. At the onset of differentiation, GLT cell cultures were cotransfected with plasmids coding for the rabbit cardiac GFP-α1C (27) and α2δ-1-specific short hairpin RNA (14) expressed from a pSilencer1.0-U6 expression vector (Ambion, Huntington, U.K.) by using FuGene transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). A total of 2 μg of plasmid DNA was used per 35 mm culture dish while the amount of the siRNA plasmid was chosen to ensure a 12-fold molar excess in combination with GFP-α1C. Three to 5 days later, the transfected cells were analyzed as described in ref. 14.

Antibodies.

The monoclonal α2δ-1 antibody mAb 20A (1:1,000) (28) was used with Alexa-594-conjugated secondary antibody and the affinity-purified anti-GFP antibody (1:4,000; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) together with an Alexa-488 secondary antibody so that the antibody label and the intrinsic GFP signal were both recorded in the green channel. Images were recorded on a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) Axiophot microscope with a cooled CCD camera and METAVUE image-processing software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA).

Electrophysiology.

Ruptured-patch whole-cell voltage and current clamp were used to measure Ca2+ currents and membrane potential (Em), respectively. Ca2+ currents were recorded at room temperature by using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Patch pipettes had resistances of 1.5–3 MΩ when filled with 145 mM Cs-aspartate, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 0.1 mM Cs-EGTA, 2 mM Mg-ATP, and 0.2 mM Fluo-4 to record Ca2+ transients in AP-clamp mode (pH 7.4 with CsOH). The bath solution contained 10 mM CaCl2, 145 mM tetraethyl ammonium chloride, and 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4 with tetraethylammonium hydroxide). Data acquisition and command potentials were controlled by pClamp software (version 8.0; Axon Instruments); analysis was performed using Clampfit 8.0 (Axon Instruments) and SigmaPlot 8.0 (SPSS Science, Chicago, IL) software. The kinetic properties of activation and inactivation were determined by fitting the entire current trace with a three-exponential function (see also SI Methods and SI Table 2) by using Clampfit 8.0 software.

For current-clamp experiments, the patch pipette had a resistance of 2–3.5 MΩ when filled with 120 mM potassium aspartate, 8 mM KCl, 7 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 5 mM Mg-ATP, 0.3 mM Na-GTP, and 0.2 mM Fluo-4 (pH 7.2 with KOH); the bath solution contained 145 mM NaCl2, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4 with NaOH). APs were triggered at 0.5 Hz by 2-ms square pulses, and the 20th AP was selected for analysis. Recordings were made with an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments) controlled by pClamp software (version 10.0; Axon Instruments). AP duration was measured at AP/2.

Computer Modeling.

A detailed model of Ca2+ dynamics and ionic currents (18) was used to simulate the effects of α2δ-1 depletion on cardiac myocytes. The programming of the AP and Ca2+ dynamics was done on an IBM PC desktop computer in standard C programming language running on Linux (Mandriva 2006). Differential equations were solved using the CVODE package (www.netlib.org/ode/index.html). The properties of the differential equations defining the Ca2+ current were modeled and analyzed with Maple software (Maplesoft, Ontario, Canada).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Angebrand, S. Baumgartner, and Dr. G. Kugler for excellent technical help; Dr. D. Bers (Maywood, IL) for kindly providing the myocyte computer model; and Dr. F. Kronenberg for helpful discussions. This work was supported by European Commission Grant HPRN-CT-2002-00331, the Austrian Science Ministry, and Austrian Science Fund Grants P16532-B05, P17806-B05 (both to B.E.F.) and P17807-B05 (to G.J.O.).

Abbreviations

- AP

action potential

- EC

excitation–contraction.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0700577104/DC1.

References

- 1.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Decher N, Kumar P, Sachse FB, Beggs AH, Sanguinetti MC, Keating MT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8089–8096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502506102. discussion 8086–8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, Decher N, Kumar P, Bloise R, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Joseph RM, Condouris K, et al. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Striessnig J. Cell Physiol Biochem. 1999;9:242–269. doi: 10.1159/000016320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seisenberger C, Specht V, Welling A, Platzer J, Pfeifer A, Kuhbandner S, Striessnig J, Klugbauer N, Feil R, Hofmann F. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39193–39199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball SL, Powers PA, Shin HS, Morgans CW, Peachey NS, Gregg RG. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1595–1603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arikkath J, Campbell KP. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:298–307. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klugbauer N, Marais E, Hofmann F. J Bionenerg Biomembr. 2003;35:639–647. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000008028.41056.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bian F, Li Z, Offord J, Davis MD, McCormick J, Taylor CP, Walker LC. Brain Res. 2006;1075:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo ZD, Calcutt NA, Higuera ES, Valder CR, Song YH, Svensson CI, Myers RR. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:1199–1205. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felix R, Gurnett CA, De Waard M, Campbell KP. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6884–6891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-06884.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takekura H, Paolini C, Franzini-Armstrong C, Kugler G, Grabner M, Flucher BE. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5408–5419. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanabe T, Mikami A, Numa S, Beam KG. Nature. 1990;344:451–453. doi: 10.1038/344451a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasielke N, Obermair GJ, Kugler G, Grabner M, Flucher BE. Biophys J. 2003;84:3816–3828. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obermair GJ, Kugler G, Baumgartner S, Tuluc P, Grabner M, Flucher BE. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2229–2237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi SX, Miriyala J, Colecraft HM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7193–7198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306665101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei X, Neely A, Lacerda AE, Olcese R, Stefani E, Perez-Reyes E, Birnbaumer L. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1635–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon TR, Wang F, Puglisi J, Weber C, Bers DM. Biophys J. 2004;87:3351–3371. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flucher BE, Phillips JL, Powell JA. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1345–1356. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flucher BE, Kasielke N, Grabner M. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:467–478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao B, Sekido Y, Maximov A, Saad M, Forgacs E, Latif F, Wei MH, Lerman M, Lee JH, Perez-Reyes E, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12237–12242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hitzl M, Striessnig J, Neuhuber B, Flucher BE. FEBS Lett. 2002;524:188–192. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sipos I, Pika-Hartlaub U, Hofmann F, Flucher BE, Melzer W. Pflügers Arch. 2000;439:691–699. doi: 10.1007/s004249900201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klugbauer N, Lacinova L, Marais E, Hobom M, Hofmann F. J Neurosci. 1999;19:684–691. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00684.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shistik E, Ivanina T, Puri T, Hosey M, Dascal N. J Physiol. 1995;489:55–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shirokov R, Ferreira G, Yi J, Rios E. J Gen Physiol. 1998;111:807–823. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.6.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell JA, Petherbridge L, Flucher BE. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:375–387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabner M, Dirksen RT, Beam KG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1903–1908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morton ME, Froehner SC. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:11904–11907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.