Abstract

RNAs that code for the major rice storage proteins are localized to specific subdomains of the cortical endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in developing endosperm. Prolamine RNAs are localized to the ER and delimit the prolamine intracisternal inclusion granules (PB-ER), whereas glutelin RNAs are targeted to the cisternal ER. To study the transport of prolamine RNAs to the surface of the prolamine protein bodies in living endosperm cells, we adapted a two-gene system consisting of green fluorescent protein (GFP) fused to the viral RNA binding protein MS2 and a hybrid prolamine RNA containing tandem MS2 RNA binding sites. Using laser scanning confocal microscopy, we show that the GFP-labeled prolamine RNAs are transported as particles that move at an average speed of 0.3 to 0.4 μm/s. These prolamine RNA transport particles generally move unidirectionally in a stop-and-go manner, although nonlinear bidirectional, restricted, and nearly random movement patterns also were observed. Transport is dependent on intact microfilaments, because particle movement is inhibited rapidly by the actin filament–disrupting drugs cytochalasin D and latrunculin B. Direct evidence was obtained that these prolamine RNA-containing particles are transported to the prolamine protein bodies. The significance of these results with regard to protein synthesis in plants is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

mRNA localization is a key mechanism in controlling the synthesis of proteins to specific regions of the cell. This process is involved in cell fate determination in yeast (Chartrand et al., 2001) and during early vertebrate development (Bashirullah et al., 1998; Palacios and Johnston, 2001). In somatic cells, RNA localization mediates the targeting of proteins to specific subcellular regions, especially in structurally polarized cells (Ainger et al., 1997; Carson et al., 1998; Shestakova et al., 2001). RNA localization also is observed in plants during embryogenesis and polarized cell growth (Okita and Choi, 2002). This process likely is involved in the intercellular transport of RNAs through the plasmodesmata (Haywood et al., 2002).

Rice synthesizes major quantities of two storage proteins, prolamines and glutelins. These proteins are synthesized on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), translocated to the ER lumen, and then packaged in separate compartments of the endomembrane system. Prolamines are sequestered within the ER lumen as intracisternal granules, whereas glutelins are transported via the Golgi to storage vacuoles. We demonstrated previously that the rice storage protein RNAs are localized to distinct subdomains of the ER (Li et al., 1993; Choi et al., 2000; Hamada et al., 2003). Glutelin RNAs, which code for the major storage protein, are localized to the cisternal ER, whereas prolamine RNAs are targeted to ER that surrounds the intracisternal prolamine protein bodies (PB-ER). Prolamine RNAs are localized to the PB-ER by an RNA-targeting mechanism (Choi et al., 2000). Interestingly, although the prolamine primary sequence is not essential for RNA targeting to the PB-ER, a translation AUG initiation codon is required. In the absence of an intact AUG, the prolamine RNA is mislocalized to the cisternal ER. These observations suggest that the regulated prolamine RNA pathway requires the participation of the translational machinery (Choi et al., 2000).

Results obtained from deletion studies of prolamine RNA indicate that PB-ER targeting requires the presence of two cis elements (Hamada et al., 2003) or “zip codes” (Singer, 1993). The presence of a single zip code results in localization not only to the PB-ER but also to the cisternal ER. These observations indicate that prolamine RNAs are directed to the PB-ER and that the absence of one or more zip codes results in RNAs transported along a default pathway to the cisternal ER. Interestingly, despite the existence of this constitutive RNA transport to the cisternal ER, glutelin RNAs are localized to the cisternal ER by a regulated pathway whose RNA signal determinant apparently is dominant over the zip codes that direct prolamine RNA to the PB-ER (Choi et al., 2000; Hamada et al., 2003).

The storage protein RNAs are transported to a region of the endosperm cell that is rich in ER. Optical sectioning of the developing endosperm cell by laser scanning confocal microscopy shows that the prolamine PBs are not distributed randomly in the cytoplasm but are concentrated predominantly in the peripheral regions of the cell (Muench et al., 2000). By contrast, the glutelin protein bodies are distributed throughout the cell, although in young cells they tend to cluster around the nucleus. The peripheral location of the prolamine PBs and their close proximity to microtubules and microfilaments indicate that these organelles are associated with the cortical ER, a complex network of tubule and cisternal membranes (Muench et al., 2000). Hence, the majority of the storage protein RNAs are transported from the nucleus, located centrally, or displaced to one end of the developing endosperm cell, to the peripheral cortex.

RNA transport is well characterized in several systems. In polarized somatic cells and during early vertebrate development, endogenous RNAs are observed as large granules (Barbarese et al., 1995; Ainger et al., 1997; Carson et al., 1998; Rook et al., 2000; Krichevsky and Kosik, 2001) or particles (Sundell and Singer, 1990; Ferrandon et al., 1994; Forristall et al., 1995; Kloc and Etkin, 1995) that move at rates ranging from 4 to 6 μm/min via cytoskeleton-associated motors (Bassell and Singer, 1997; Chartrand et al., 2001; Saxton, 2001; Kloc et al., 2002; Tekotte and Davis, 2002). When microinjected in oligodendrocytes, fluorescently labeled myelin basic protein RNA first condenses into granules that then move along microtubule tracks to the peripheral extensions, where they are localized (Ainger et al., 1993). Microinjection of the 3′ untranslated region of bicoid RNA into the Drosophila embryo results in the recruitment of the RNA binding protein Staufen into large particles that are transported to the anterior pole by a microtubule-dependent process (Ferrandon et al., 1994, 1997). Thus, RNA transport occurs by a multistep process that involves granule formation, cytoskeleton-mediated transport, and localization (Wilhelm and Vale, 1993).

The nature of the RNA transport particle (granules) is beginning to emerge. In neurons, direct microscopic evidence has been obtained showing that the RNA granules are large, tightly clustered aggregates of ribosomes. Hence, large translational complexes containing different RNA species are transported (Knowles et al., 1996; Krichevsky and Kosik, 2001; Mouland et al., 2001). It has been suggested that the formation of large RNA transport particles occurs by the assembly of hundreds of copies of localized RNAs and their corresponding RNA binding trans factors (Jansen, 2001).

Recent developments in microscopy and the introduction of fluorescent proteins coupled with recent advances in RNA biochemistry have resulted in the development of technology to monitor RNA movement and localization in living cells in real time (Bertrand et al., 1998; Takizawa and Vale, 2000). This technology takes advantage of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and the high affinity of specific RNA binding proteins (RBPs; e.g., MS2 coat protein and U1A) to small 18- and 19-nucleotide stem-loop structures. The RNA imaging system has two components: a GFP-RBP fusion protein and a hybrid RNA containing multiple copies of the stem-loop RNA binding sequences. When coexpressed, the GFP-RBP associates with the hybrid RNA, enabling one to monitor RNA transport by fluorescence microscopy in real time.

We have adapted the GFP monitoring system to follow the localization of rice storage protein RNAs in developing rice endosperm as well as in heterologous tobacco BY-2 cells. Expression in BY-2 cells established the utility of the two-gene system for monitoring RNA transport. The MS2-GFP fusion protein containing a nuclear localization signal (NLS) is found almost exclusively in the nucleus. When coexpressed with MS6X-prolamine RNA, MS2-GFP is found mainly in the cell's periphery, indicating nuclear export and transport to the cortical region, the main site of protein synthesis in plants. In developing endosperm expressing the two-gene system, prolamine RNAs are localized in particles that move to the surface of the prolamine PBs located in the cortical ER.

RESULTS

Localization of Prolamine mRNA Movement in Tobacco BY-2 Cells

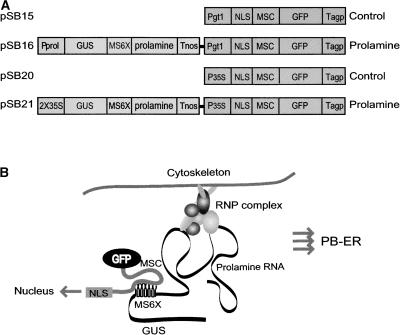

To visualize native RNA transport during rice endosperm development, we adapted the GFP two-gene system developed by Bertrand et al. (1998). In this approach, two synthetic genes are constructed and coexpressed. One gene encodes a translational fusion in which GFP is fused to the single-stranded RNA phage coat protein MS2, which binds a defined 19-nucleotide RNA stem loop (Figure 1). The MS2-GFP protein also contains a NLS to restrict the protein to the nucleus if it is not complexed to RNA. The second gene encodes a hybrid RNA containing prolamine RNA sequences fused downstream of the β-glucuronidase (GUS) coding sequence and tandem MS6X RNA binding sites. When the two genes are coexpressed, MS2-GFP binds to one or more of the MS6X binding sites, which enables one to follow the movement of the RNA in real time by fluorescence microscopy.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the Two-Gene System to Visualize RNA Transport.

(A) The two-gene system consists of one gene that encodes a translational fusion between the viral MS2 coat protein (MS2) and GFP. The MS2-GFP translational fusion also contains an in-frame NLS from SV40, which targets the fusion protein to the nucleus. The second gene codes for a hybrid GUS RNA that contains a 3′ untranslated region consisting of an MS2 RNA binding site tandemly repeated six times and prolamine RNA. The GUS enzyme activity produced by this hybrid RNA together with GFP was used to select for transgenic plants.

(B) When coexpressed, the NLS-MS2-GFP fusion protein interacts with the GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNA, enabling RNA transport to be monitored using GFP fluorescence. To monitor RNA transport in developing rice endosperm cells, the prolamine Prol and glutelin Gt1 promoters were used to drive the transcriptional and translational gene fusions, respectively. The CaMV 35S promoter was used to drive the expression of the two-gene system in tobacco BY-2 cells.

MS2, coat protein of bacteriophage MS; MS6X, hexa repeats of the MS2 RNA binding site; Pgt1, glutelin Gt1 promoter; Pprol, prolamine promoter; P35S, CaMV 35S promoter; 2x35S, CaMV 35S double enhancer; T35S, CaMV 35S terminator; Tagp, terminator of the rice ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase; Tnos, terminator of the nopaline synthase gene.

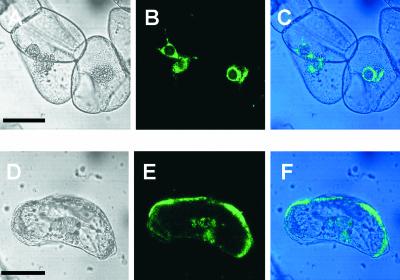

The utility of this two-gene system in monitoring RNA transport was first assessed in tobacco BY-2 cultured cells. This was accomplished by inserting the 35S promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) upstream of the NLS-MS2-GFP and GUS-MS6X-prolamine sequences and transforming these genes into BY-2 suspension cells. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the GFP fusion protein, NLS-MS2-GFP, in BY-2 cells in the absence (Figures 2A to 2C) or the presence (Figures 2D to 2F) of the expressed GUS-MS2-prolamine RNA. When expressed alone, the NLS-MS2-GFP gene is localized predominantly to the nucleus (Figure 2B). By contrast, the distribution of NLS-MS2-GFP when coexpressed with the prolamine-MS6X RNA fusion is observed mainly at the cell's periphery (i.e., in the cortical region) (Figure 2E). Therefore, expression of the two-gene system resulted in the nuclear export and transport of GFP-labeled RNA. These observations readily support the feasibility of this approach in monitoring RNA transport in plant cells.

Figure 2.

Assessment of Prolamine RNA Transport in Tobacco BY-2 Cells Using the Two-Gene System and Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy.

(A) to (C) When expressed alone, the NLS-MS2-GFP fusion protein is located predominantly within the nuclei of BY-2 cells.

(D) to (F) When coexpressed with GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNA, the fusion protein is distributed mainly to the cell's periphery, indicating RNA-mediated nuclear export and transport to the cell's cortical region.

(A) and (D) Transmitted light images. Bars = 50 μm.

(B) and (E) GFP fluorescence images.

(C) Merged image of (A) and (B).

(F) Merged image of (D) and (E).

Prolamine RNAs Form Particles in Developing Rice Endosperm

To visualize prolamine RNA movement in developing rice endosperm cells, the promoters from the rice glutelin Gt1 (Zheng et al., 1993) and prolamine pProl (Wu et al., 1998) were inserted upstream of NLS-MS2-GFP and GUS-MS6X-prolamine, respectively (Figure 1). These two genes then were cloned into the T-DNA vector pCAMBIA1301, which was used to transform rice via Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Candidate plants for RNA movement were screened initially by immunoblot analysis for the expression of the two-gene system (i.e., for the NLS-MS2-GFP fusion and the GUS protein as well as for GUS histochemical staining activity in endosperm tissue). Plants that accumulated readily detectable amounts of these reporter proteins were selected and grown for several generations before analysis. The results reported here were obtained from homozygous third- to fifth-generation plants.

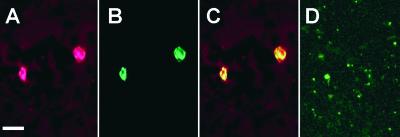

Figure 3 show the distribution of the NLS-MS2-GFP fusion protein in transgenic rice lacking GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNA sequences (Figures 3A to 3C) or coexpressing this prolamine transcriptional gene (Figure 3D). When expressed alone, the NLS-MS2-GFP is distributed mainly in the nucleus in the endosperm sections (Figures 3A to 3C). When coexpressed with GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNA, an entirely different distribution pattern of fluorescence is seen. Numerous small fluorescent particles ranging in size from 0.3 to 2 μm in diameter are readily evident (Figure 3D). These particles are distributed randomly in the focal plane across the cell. Several fluorescent particles move within the observed focal plane of the cell, indicating RNA movement. The movement patterns of this macromolecular complex were investigated further as described below.

Figure 3.

GFP Localization in Developing Rice Endosperm Using the Two-Gene System as Viewed by Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy.

(A) to (C) GFP fusion proteins are observed as large fluorescent clusters located in the nucleus when the NLS-MS2-GFP structural gene is expressed in the absence of the second GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNA coding gene. Nuclei were visualized by staining the endosperm section with propidium iodide (A), and native GFP fluorescence is depicted in (B). (C) is a merged image of (A) and (B) showing the localization of the GFP fusion protein to the nucleus. Bar in (A) = 10 μm.

(D) Expression of the two-gene system in developing rice endosperm results in the GFP fusion protein appearing as small fluorescent particles distributed randomly within the microscopic focal plane.

Movement of Prolamine RNA Transport Particles

Sections (75 to 100 μm) of developing endosperm were placed on a glass slide, bathed in MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing amino acids and sucrose, and observed by laser scanning confocal microscopy for RNA particle movement. Based on the observation of more than several hundred individual RNA transport particle movement patterns, the following observations are typical. Although many of the fluorescent particles are stationary, other particles could be seen moving in and out of the focal plane of observation. In many instances, we were able to capture the movement of particles within a focal plane, enabling its transport to be followed over time.

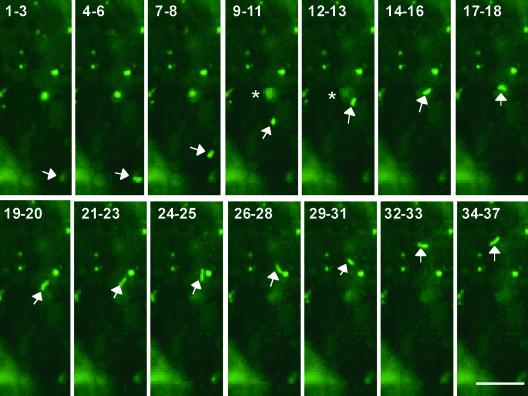

Figure 4 shows a series of snapshots taken at ∼15-s intervals depicting the movement of one particle. In time frame 1–3 (0 to 45 s), the particle appears in the focal plane, where it remains stationary until between frames 4–6 and 7–8 (90 to 105 s), where it commences nearly unidirectional movement. The velocity of the particle, which assumes an elongated shape, is not constant, for the particle moves in a saltatory manner. It remains stationary for several time frames before initiating movement again, eventually covering a distance of >30 μm.

Figure 4.

Movement of Prolamine RNA in Developing Rice Endosperm as Viewed by GFP Fluorescence Using the Two-Gene System and Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy.

Shown are snapshots taken at 15-s intervals depicting the movement of a prolamine RNA transport particle (arrows). The numbers represent the number of 15-s time frames taken since the acquisition of the first image. Unlike most particles observed, this movement particle assumes an elongated shape. The velocity of the particle is not constant; rather, it moves in a stop-and-go manner. In frames 9–11 and 12–13 (135 to 195 s), the particle moves very near a large stationary particle (asterisk), which apparently moves out of the focal plane between frames 9–11 and 14–16 (165 to 210 s). Overall, the particles move a linear distance of ∼30 μm in 10 min before the fluorescence signal disappears. Bar = 10 μm.

A large fluorescent particle (labeled with an asterisk in frame 9–11) appears stationary in the first four frames. In subsequent frames, this large fluorescent particle apparently moves out of the focal plane (between frames 12–13 and 14–16), whereupon the elongated particle transverses right over or very close to the site occupied by the larger particle. In later time frames, the elongated particle moves very close to and nearly contacts a second fluorescent particle, which remains stationary during this time sequence (see frames 24–25 and 26–28). The particle goes on to move another 6 μm before the fluorescent signal weakens and later disappears. The loss of the fluorescent signal may be attributable to movement of the particle out of the focal plane. In several instances, however, the fluorescent signal appears to expand with accompanying loss of fluorescence, a pattern suggesting that the particle dissociates.

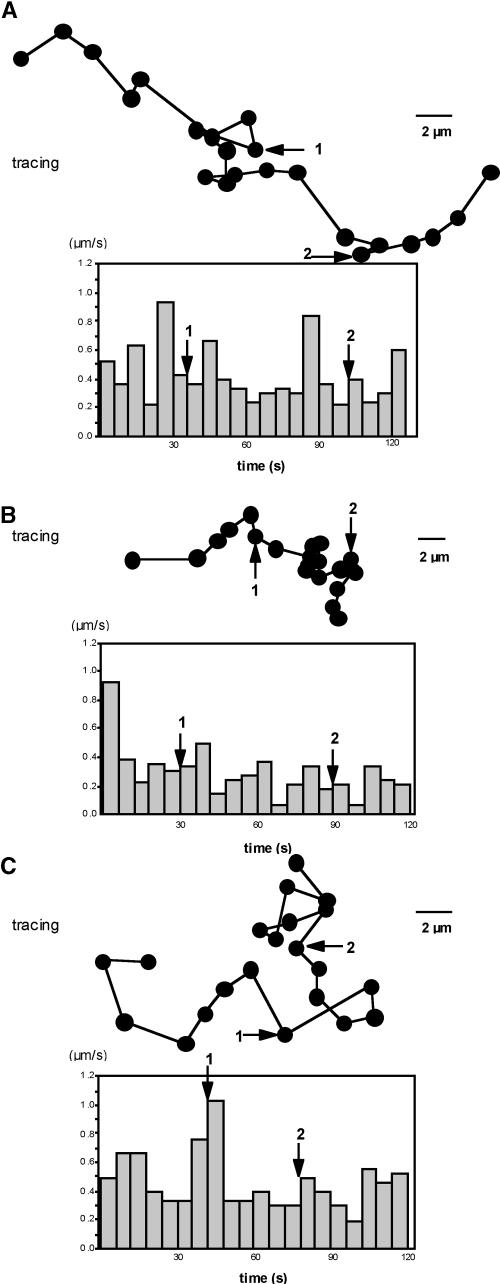

Figure 5 shows the tracings of movement behavior of three particles that exemplify the velocity and directional movement patterns typically observed in our study. Movement of the particles generally is unidirectional, although changes in direction for short distances also are observed, as shown in Figure 5A. A second typical characteristic of the movement of many particles is that during transport, movement of the particle is restricted to a small area before commencing longer distance movement, as indicated in Figure 5B. Another example of these movement behaviors can be seen in the supplemental data online (http://www.plantcell.org). A third type of particle movement is shown in Figure 5C. The particle changes direction repeatedly, so that the overall movement pattern appears stochastic.

Figure 5.

Variation in Particle Movement Patterns in Developing Rice Endosperm Cells.

The movement patterns of three particles were traced, and each time point was taken at 5-s intervals. These three types of movement were typical of the hundreds observed during the course of this study and represent nearly unidirectional movement (A), movement confined to a small area (B), and nearly random movement (constant changes in direction) (C). Below each particle movement tracing is a graph depicting the average velocity between two successive time points. Particle velocity ranges from a high of ∼1 μm/s to a low of ∼0.05 μm/s, with an average speed of 0.3 to 0.4 μm/s.

The average velocities of these particles were estimated by measuring the distance traveled by the particle between two adjacent frames, which ranged from a high of ∼1 μm/s to a low of less than ∼0.05 μm/s. Despite the different patterns of movement shown in Figures 5A to 5C, the average velocities were similar and varied only slightly between 0.3 and 0.4 μm/s. This speed is consistent with that expected for the involvement of a cytoskeleton-associated motor protein.

Prolamine RNA Particle Movement Is Dependent on Intact Microfilaments

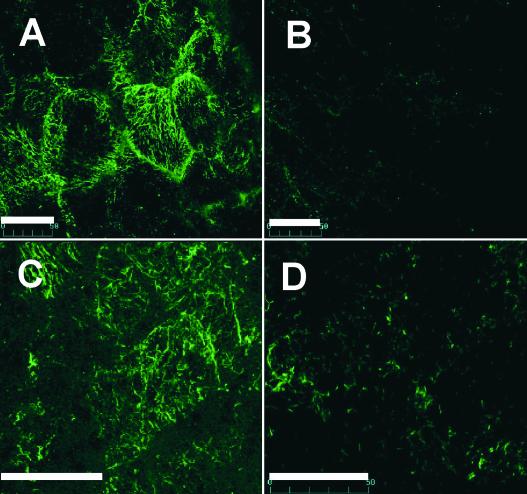

To determine the role of the cytoskeleton, the movement behavior of particles was investigated after treatment with different cytoskeleton-disrupting drugs. Treatment of developing endosperm sections for 20 min with 100 μM nocodazole or 20 μM latrunculin B disrupted the arrays of microtubules (Figures 6A and 6B) and actin filaments (Figures 6C and 6D), respectively, present in developing endosperm. Actin filaments also were sensitive to cytochalasin D (data not shown). Developing endosperm sections showing particle movement were bathed in MS medium containing 100 μM nocodazole, 20 μM latrunculin B, or 100 μM cytochalasin D and examined for particle movement by laser scanning confocal microscopy. The earliest measurement for assessing RNA movement was at ∼3 to 5 min under the experimental conditions. The results of three different experiments are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Structure of Microtubules and Microfilament Arrays in Developing Rice Endosperm and Their Disruption by Nocodazole and Latrunculin B.

(A) Microtubules were visualized by indirect immunofluorescence labeling methods using α-tubulin monoclonal antibody followed by fluorescein-tagged goat anti-mouse antibody.

(B) and (D) Preincubation of developing endosperm sections (∼300 μm thick) in 100 μM nocodazole (B) or 20 μM latrunculin B (D) for 20 min results in the disruption of these cytoskeletal elements.

(C) Microfilaments were visualized directly with phalloidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor 488.

Bars = 50 μm.

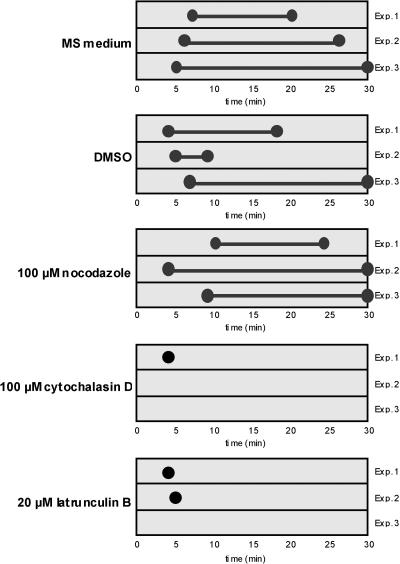

Figure 7.

Inhibition of Particle Movement by Cytoskeleton-Disrupting Drugs.

Developing endosperm sections (∼75 to 100 μm thick) were bathed in amino acid– and sucrose-supplemented MS medium containing DMSO, 100 μM nocodazole, 100 μM cytochalasin D, or 20 μM latrunculin B. Sections then were viewed by laser scanning confocal microscopy for particle movement for up to 30 min. The earliest observation took place 3 to 5 min after the addition of the cytoskeletal inhibitor. The duration of particle movement is indicated by two connected circles. Control sections incubated in supplemented MS medium alone showed particle movement up to 20, 26, and 30 min in three separate experiments. The actin filament drugs cytochalasin D and latrunculin B rapidly stopped particle movement within 3 to 5 min, whereas the microtubule inhibitor nocodazole had little effect. No particle movement was evident after 3 to 5 min in endosperm sections treated with cytochalasin D in experiments 2 and 3 or with latrunculin B in experiment 3. Even when particle movement was detected in the presence of these microfilament inhibitors, as denoted by single circles, many of the particles stopped moving while the rest oscillated in position very slowly.

Under normal conditions, particle movement could be detected easily for up to 30 min. The addition of DMSO, the solvent used to dissolve the cytoskeleton-disrupting agents, or the microtubule drug nocodazole had minimal effect on RNA movement except for one experiment in which particle movement was not observed after 9 min of treatment. By contrast, the microfilament inhibitors cytochalasin D and latrunculin B rapidly inhibited particle movement. Even at the earliest observation time (3 to 5 min), particle movement was affected significantly by these microfilament inhibitors, because most particles stopped moving and others simply oscillated very slowly in position. In all cases, particle movement was inhibited completely within 5 min. These results are consistent with the view that RNA particle movement is dependent on intact microfilaments.

Prolamine RNA Particle Transport to the Prolamine Protein Bodies

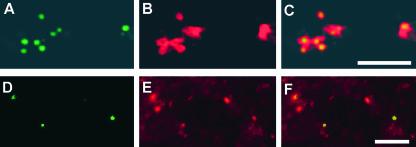

Prolamine RNAs are distributed specifically to the ER that bound the prolamine PBs (Li et al., 1993; Choi et al., 2000). To identify the location of the GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNA, in situ reverse transcriptase–PCR was performed using primers specific for GUS and Oregon Green dUTP followed by laser scanning confocal microscopy to assess the distribution of the fluorescently labeled RNA (Figure 8). As expected, the GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNA (Figure 8A) is localized specifically to the prolamine PBs (Figure 8C), which are labeled preferentially with rhodamine hexyl ester (Figure 8B) as a result of its preferential binding to the hydrophobic prolamine polypeptides. These results indicate that the hybrid GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNAs are transported and localized to the PB-ER.

Figure 8.

Prolamine RNA Transport Particles Are Transported to the Prolamine PBs.

(A) The distribution of GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNAs was visualized by confocal microscopic analysis of endosperm sections subjected to in situ reverse transcriptase–PCR in the presence of GUS primers and Oregon Green-488 dUTP.

(B) The same section stained with rhodamine hexyl ester, which specifically labels the prolamine PBs as a result of the affinity of this dye for the hydrophobic prolamine polypeptides.

(C) A merged image of (A) and (B) depicting the localization of the GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNAs to prolamine PBs. Bar = 10 μm.

(D) to (F) Colocalization of GFP-tagged particles (F) as viewed by native GFP fluorescence (D) with prolamine PBs stained with rhodamine hexyl ester (E). Note that only three of the five prolamine PBs seen in these images show colocalization with GFP-tagged particles, indicating that green fluorescence is not the result of spillover from rhodamine hexyl ester staining. Bar = 10 μm.

Further evidence that GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNAs were transported to the prolamine PBs was discovered by assessing the distribution of the GFP-associated RNA transport particles in endosperm thick sections relative to prolamine PBs by observing native GFP fluorescence in live endosperm sections. Because rhodamine fluorescence (red emission) partially overlaps the green portion of the spectra, the endosperm section was treated only lightly with this vital stain by reducing the concentration and exposure time. Under these conditions, the amount of spillover by rhodamine hexyl ester fluorescence in the green channel was negligible compared with the native fluorescent signal emitted by GFP. Figure 8 shows the distribution of the RNA transport particles as viewed by native GFP fluorescence (Figure 8D) relative to prolamine PBs (Figure 8E) in a native endosperm section. Three GFP-containing RNA transport particles are evident that colocalize with prolamine PBs (Figure 8F). Not all of the prolamine PBs had associated RNA transport particles, indicating that the green fluorescent signal is not the result of spillover fluorescence from rhodamine hexyl ester staining.

Efforts were made to capture the movement of the RNA transport particle to the prolamine PBs in real time. Such a visual capture of the transport of RNA particles to prolamine PBs was a rare event. Figure 9 shows a tracing of the movement of an RNA transport particle as viewed by GFP fluorescence. The particle moves to a prolamine PB before the fluorescent signal fades and disappears.

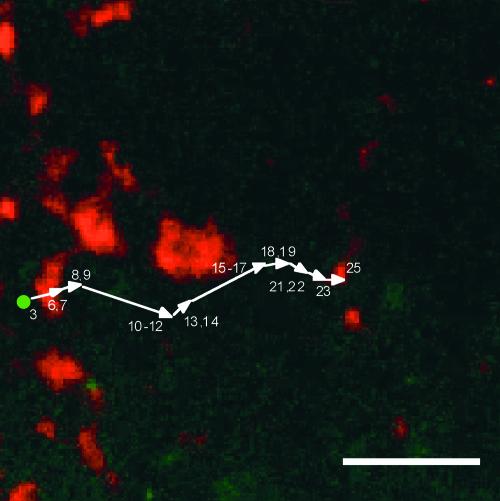

Figure 9.

Movement of a Prolamine RNA Transport Particle to a Prolamine PB.

A developing endosperm section was stained with rhodamine hexyl ester, washed to remove excess stain, and then analyzed for native GFP fluorescence by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Images were captured at 15-s intervals. The numbers represent the number of 15-s time frames taken since the acquisition of the first image. The distance between the start and the final destination is 21 μm. A video depicting this transport is available in the supplemental data online (http://www.plantcell.org). Bar = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

The two-gene system used in this study shows that RNA transport in plants shares many of the properties seen in other eukaryotic systems (Wilhelm and Vale, 1993; Barbarese et al., 1995; Ferrandon et al., 1997; Bertrand et al., 1998; Wilkie and Davis, 2001). First, RNA transport occurs via a large multi-macromolecular complex, a “particle.” Moving particles typically had an observable size of ∼0.5 to 1 μm in diameter, although larger particles also were evident in developing rice endosperm. The actual size of these particles likely is smaller because of the diffuse nature of the fluorescent signal (Barbarese et al., 1995) and the use of six MS2 binding sites to amplify the fluorescent signal via the interactive GFP fusion protein. The larger particles, which may be formed by the fusion of smaller particles, as seen in budding yeast (Bertrand et al., 1998), were stationary and had variable sizes up to 2 μm in diameter. Some transport particles also were seen as elongated entities, as shown in Figure 4. These elongated particles appear to move by a process similar to that of a Slinky toy, in which one end serves as a pivot allowing the other end to move and then pivot, thereby reinitializing the movement cycle.

Particle formation also was evident in tobacco BY-2 cells, although such particles were much larger (>2 to 3 μm in diameter) than those seen in developing rice endosperm. In several instances, two or three closely associated particles were observed to move back and forth in unison (data not shown). Although there are several explanations that could account for the particle size differences between the two cell types, they are likely the result of differences in expression of the two-gene system (Bertrand et al., 1998). The potent modified CaMV 35S promoter from pRTL2, which contains double enhancer elements and a TEV leader, was used to drive GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNA expression in BY-2 cells, whereas the rice seed–specific prolamine Prol promoter was used to drive the expression of this gene in developing rice endosperm cells. In our hands, the Prol promoter was found to be a relatively weak promoter (our unpublished observations), especially compared with the Gt1 promoter, which is one of the strongest rice seed–specific promoters available (Zheng et al., 1993). Increased constitutive expression has been suggested to account for the formation of a single large particle containing ASH1 RNA instead of the several smaller particles evident under controlled expression (Bertrand et al., 1998). Hence, the smaller particles in rice endosperm cells likely are attributable to the lower transcript levels of GUS-MS6X-prolamine RNA compared with the levels expressed in BY-2 cells.

A common feature of RNA localization is their final destination site in the plant cell. In tobacco BY2 cells and developing rice endosperm, RNAs are localized to the cortical region. In both cell types, RNA transport particles are not prevalent in the perinuclear region. Such a condition should be readily conspicuous in BY-2 cells because of their highly vacuolated nature. Other than their predominant location at the cell's periphery, fluorescent RNA particles are evident on the cytoplasmic transvacuolar strands. Because these “strands” contain actin filaments, the association of RNA particles with transvacuolar strands may represent their transport via actomyosin (see below).

The transport and localization of RNAs to the cortical region may be essential for the expression of these gene sequences in plants. Other than the perinuclear region and cytoplasmic transvacuolar strands, the cortical region is the only intracellular site rich in actin filaments. These cytoskeletal elements have been suggested to be essential for efficient protein synthesis because they may provide a scaffold for polysomes or serve as a site enriched for translation factors, such as eEF1A (Lenk and Penman, 1979; Davies et al., 1991, 1996; Hesketh and Pryme, 1991).

The visualization of RNA movement in real time provides several insights into the localization mechanism. The movement of the RNA particle generally was directional, although nonlinear bidirectional movement also was seen. In many instances, the particles transverse a wandering path whose total length spans much longer than the shortest distance between two points. Irrespective of the path taken, the transport particles move with an average speed of ∼0.3 to 0.4 μm/s, a value similar to the estimated velocity of β-actin RNA in fibroblasts (Oleynikov and Singer, 2003). The highest instantaneous velocity measured was 1 μm/s, slower than the peak velocities (2 to 10 μm/s) observed for the movement of the Golgi apparatus (Boevink et al., 1998; Nebenfuhr et al., 1999) and peroxisomes (Jedd and Chua, 2002) in plant cells. At least part, if not all, of the apparent differences in peak velocities between the RNA particles and plant organelles is the result of our inability to capture images by confocal microscopy at a sufficient rate to accurately measure peak velocities. In this study, RNA movement images were captured at one frame every 5 s, a time frame that includes periods of discontinuous movement behavior. By contrast, the estimation of plant organellar movement was obtained at rates of one frame per second or greater (Boevink et al., 1998; Nebenfuhr et al., 1999; Jedd and Chua, 2002).

The movement patterns and average speeds of the RNA transport particles are consistent with the involvement of a cytoskeletal motor protein (Bassell et al., 1999; Jansen, 1999, 2001; Tekotte and Davis, 2002). Indeed, RNA particle movement is inhibited by latrunculin B and cytochalasin D, two drugs that disrupt microfilaments. A specific motor protein, Myo4, an unconventional, nonmuscle class-V myosin, is essential for the transport of ASH1 RNA to the daughter cell in budding yeast (Long et al., 1997; Takizawa et al., 1997). Interestingly, analysis of the Arabidopsis genome identified 17 myosin sequences (Reddy and Day, 2001). Surprisingly, none of these myosins belongs to class V; instead, they fall into class VIII and class XI, myosin types unique to plant species. Myosin XI has many structural features similar to those of myosin V, including six light chain binding motifs (IQ motifs) and a C-terminal tail with coiled-coil segments interspersed with nonhelical regions (Reck-Peterson et al., 2000). Based on structural similarities, it is likely that a member of this myosin class plays a role in RNA transport.

In addition to the yeast ASH1 and the rice storage protein RNAs, the only known examples of RNA transport by actomyosin involve β-actin in fibroblasts and possibly prospero mRNA in Drosophila neuroblasts (Palacios and Johnston, 2001). The bulk of the RNAs transported in animal cells are microtubule based (Pokrywka, 1995; Bogucka-Glotzer and Ephrussi, 1996; Carson et al., 1997; Arn and Macdonald, 1998; Bloom and Beach, 1999; Tekotte and Davis, 2002). The use of microtubules in RNA transport may reflect the fact that this cytoskeleton component is capable of forming long structures, especially in polarized, differentiated cell types of vertebrate cells and oocytes (Steebings, 2001).

Ongoing studies in this laboratory indicate the existence of multiple RNA transport pathways from the nucleus to the cortical region in developing rice endosperm cells (Hamada et al., 2003). In addition to the prolamine RNA pathway to the PB-ER, there exists a glutelin RNA pathway as well as a constitutive pathway to the cisternal ER. Analysis of glutelin RNA transport using the two-gene system reveals no apparent differences in RNA movement from that seen for prolamine RNAs (our unpublished observations). Glutelin RNAs are transported as particles with movements similar, if not identical, to those described here for prolamine RNA transport (data not shown). The formation of a particle may be a requisite step for RNA transport to the cortical region in developing rice endosperm. Although not studied directly, it is likely that RNAs engaged in the constitutive pathway are transported and localized to the cortical region by a process similar to that seen for the storage protein RNAs. The formation of the particle is likely to involve generalized localization elements that direct transport to the cortical ER and specialized signal determinants (zip codes) that target the RNA to specific subdomains of the cortical ER. These specialized cis elements or zip codes have been identified for the prolamine RNA and are sufficient to direct reporter RNAs to the PB-ER (Hamada et al., 2003). The glutelin 3′ untranslated region also has one or more specialized cis elements to direct the RNA to the cortical ER (Choi et al., 2000; Hamada et al., 2003).

The intensity of the fluorescent signal and the size of the particle suggest that multiple RNAs are cotransported within the same entity (Fusco et al., 2003). In Drosophila, bicoid RNA forms a particle in conjunction with Staufen, a helicase-like protein that contains five double-stranded RNA binding domains. The recruitment of Staufen into particles is dependent on intermolecular RNA–RNA interactions, suggesting that the particle is a large multimolecular complex containing many RNAs (Ferrandon et al., 1997). Microinjected fluorescently labeled wingless and pair-rule transcripts coassemble into a particle and move to the apical end of the Drosophila blastoderm along microtubules (Wilkie and Davis, 2001). The presence of multiple RNA species within a transport particle also is supported by the cotransport of fluorescently tagged Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) RNAs in oligodendrocytes. Both the HIV gag and vpr RNAs contain the A2RE zip code that is recognized by hnRNP A2, which mediates anterograde transport of the A2RE-containing RNA granules (particles) along microtubules (Barbarese et al., 1995; Ainger et al., 1997; Carson et al., 1997). Based on ratiometric analysis, each transport particle was estimated to contain 29 molecules of these fluorescently tagged RNA species (Mouland et al., 2001). This estimated RNA content probably is much lower than the actual levels, because the transport RNA granules likely contain other endogenous unlabeled A2RE-containing RNAs. Studies now under way are aimed at isolating these GFP-tagged RNA transport particles and assessing their RNA composition.

METHODS

Plasmid DNA Construction and Plant Transformation

To visualize the movement of prolamine RNAs in living cells, the two-gene system from Bertrand et al. (1998) was adapted. Plasmid expressing the MS2-GFP translational fusion gene in BY-2 tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) cells was obtained as follows. GFP (Davis and Vierstra, 1998) DNA coding sequence was amplified using primers (5′-GTATCAGCGGCCGCGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTT-3′ and 5′-GAAATTCGAGCTCTT- ATTTGTATAGTTCATCC-3′) and then cloned into the NotI-SalI sites of pBluescript KS II− (Stratagene). A BamHI-NotI fragment encoding an SV40 nuclear localization sequence and MS2 viral capsid protein was obtained from pG14-MS2-GFP (Bertrand et al., 1998) and cloned into the upstream BamHI-NotI site of the GFP sequence. The resulting NLS-MS2-GFP was removed with BamHI and SacI digestion and inserted into pBluescript KS II− containing the nos 3′ terminator (Tnos) cloned into the SacI and EcoRI sites. The NLS-MS2-GFP-Tnos DNA fragment then was obtained by digestion with BamHI and HindIII and transferred into pET30a(+) (Novagen, Madison, WI). The 35S promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) was cloned into the NcoI and BamHI sites of pET30a(+) containing NLS-MS2-GFP-Tnos. The CaMV 35S-NLS-MS2-GFP-Tnos DNA then was generated by digestion with BglII and HindIII and subsequently cloned into the BamHI and HindIII sites of pCAMBIA1300 to produce a control plasmid, pSB20.

To generate the hybrid RNA gene fusion consisting of β-glucuronidase (GUS)-MS6X-prolamine, prolamine7 cDNA was isolated by digestion of pProl7 (Kim et al., 1988) with HincII and NotI and then cloned into the EcoRV and NotI sites of pSL-MS2-6 (Bertrand et al., 1998). The resulting plasmid then was digested with BamHI, and the MS6X-prolamine sequences were cloned subsequently at the filled-in XhoI-NcoI sites downstream of the GUS coding sequence of pRTL2 to produce CaMV 35S 2X-GUS-MS6X-T35S. This transcriptional fusion gene was obtained by HindIII digestion, and the resulting fragment was cloned into the same site of pSB20 to yield pSB21 for prolamine.

pSB15 and pSB16 were constructed for expression in rice (Oryza sativa) endosperm cells. A NotI-SalI fragment containing the GFP gene from pG14-MS2-GFP (Bertrand et al., 1998) and a ClaI-HpaI fragment containing the ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase terminator (Tagp) were cloned into the NotI-HindIII and ClaI-HincII sites, respectively of pBluescript II KS. The BamHI-NotI insert from pG14-MS2-GFP containing the NLS-MS2 fusion was cloned into pSL1180 (Pharmacia). To combine NLS-MS2 and GFP-Tagp, a NotI-XhoI fragment containing GFP-Tagp was cloned into the same sites of pSL1180 containing the NLS-MS2 sequence. A BamHI-BglII fragment containing NLS-MS2-GFP-Tagp then was transferred into the BglII site of pSP72, which contains the 1.8-kb Gt1 promoter fragment (Zheng et al., 1993) inserted at the EcoRI-BglII sites (Choi et al., 2000).

The RNA transcriptional gene fusion was driven by the prolamine Pprol promoter (Wu et al., 1998) and was prepared as follows. A SacI-HindIII fragment containing the nos terminator (Tnos) was cloned into pSL1180. To form the Pprol-MS6X fusion, the MS6X fragment (BamHI-SacI) from pSL-MS2-6 was cloned into the BamHI-SacI of pProl (Wu et al., 1998). The resulting plasmid was digested with EcoRI and NotI, and the Pprol:MS6X fragment was cloned upstream of Tnos. The GUS sequence was amplified using the primers 5′-GAGGATCCCCGGGTAGGTCAGTCCC-3′ and 5′-CAGGATCCTTGTTGATTCATTGTTTGC-3′ and cloned into the BamHI site after digestion of Pprol:MS6X:Tnos. Prolamine cDNA that had been digested with HincII-NotI was cloned into the HpaI-NotI sites of the plasmid containing Pprol-GUS-MS6X-Tnos to yield Pprol-GUS-MS6X-prolamine cDNA-Tnos.

The MS2-GFP and GUS-MS6X-prolamine-Tnos DNA fragments were combined into a single plant expression vector, pCAMBIA1300. The XbaI-BglII fragment containing the MS2:GFP gene was cloned into the XbaI and BamHI sites of pCAMBIA1300 and designated pSB15. A HindIII fragment containing Pprol-GUS-MS6X-prolamine cDNA-Tnos was inserted into the HindIII site of pSB15 to produce pSB16.

Transformation of tobacco BY-2 calli was achieved by cocultivation with Agrobacterium tumefaciens Agl1 for 3 days at 28°C. Calli then were transferred onto an MS medium plate (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing 0.2 mg/L 2,4-D, 150 μg/mL timentin, and 50 μg/mL hygromycin. Cell suspension lines were prepared by growing calli on liquid MS selection medium. Transformation of rice and rice growth conditions were as described previously (Choi et al., 2000).

In Situ Localization of GUS-MS6X-Prolamine RNA

In situ reverse transcriptase–PCR was conducted with tissue sections from developing seeds of pSB16 plants using specific primers for GUS (sense, 5′-CAGCGAAGAGGCAGTCAACGGGGAA-3′; antisense, 5′-CATTGTTTGCCTCCCTGCTGCGGTT-3′) as described previously (Choi et al., 2000). The initial reverse transcriptase reaction cycle was performed for 3 min at 94°C, 20 min at 60°C, and 5 min at 72°C, which was followed by eight amplification cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 90 s.

Tissue Preparation and Confocal Microscopy

Tobacco BY-2 suspension-cultured cells were mounted on microscope slides in MS medium and observed using a standard fluorescein filter set. Confocal images were obtained on a Zeiss 410-series laser scanning confocal microscope (Jena, Germany) and a Bio-Rad View Scan VDC-250 laser scanning confocal microscope using a ×40 objective. Untransformed BY2 cells were imaged to set the lower limits of detection for GFP fluorescence without interference from native autofluorescence.

Glumes from developing rice seeds were removed by hand. Thick sections (75 to 100 μm) from 10- to 14-day-old rice seeds were obtained using a vibratome and mounted on a microscope slide in MS medium containing an amino acid mixture and 2% sucrose using a recipe developed by Donovan and Lee (1977). Confocal analysis was performed using the same conditions used for tobacco except that a ×60 objective was used. Developing sections from wild-type plants were used to set the lower limits of detection for GFP fluorescence without interference from native autofluorescence.

Cytoskeletal Inhibitor Studies

Sections of developing endosperm were obtained and bathed in MS medium containing amino acids and 2% sucrose (Donovan and Lee, 1977) and nocodazole, latrunculin B, or cytochalasin D. The cytoskeletal inhibitors were prepared as concentrated (100 to 200 times) stock solutions in DMSO and stored at −20°C. The endosperm sections then were observed continuously for particle movement by laser scanning confocal microscopy for up to 30 min. Sections treated with MS medium containing an equivalent concentration of DMSO (5%, v/v) were used as controls.

Immunofluorescence Studies for Microtubules and Actin Filaments

The glumes of 12- to 18-day-old developing rice seeds were removed by hand. The developing seeds were sectioned by free hand into 300-μm-thick specimens. The sections were placed immediately in a Teflon-coated depression slide (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA) containing 150 μL of cytoskeleton-stabilizing buffer (CSB; 50 mM Pipes, pH 6.9, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgSO4, 1.0% DMSO, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 200 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing various amounts of nocodazole or latrunculin B. After 20 min of incubation at room temperature, the CSB solution was replaced with 100 μM cross-linking agent (m-maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester [Pierce, Rockford, IL] in CSB) and incubated for another 20 min. The sections then were fixed with freshly prepared 4% formaldehyde solution in CSB for 1 h and washed three times in PBS. Sections were incubated with cell wall digestion solution (1% cellulose, 0.4 M mannitol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.3 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 5 mM EGTA, pH 5.5) at 37°C for 3 min followed by a 15-min wash in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST). The sections then were blocked in PBS containing 2% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 45 min at 37°C.

To visualize microtubules, the permeabilized sections were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (N356; Amersham) diluted 300-fold in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed three times with PBST and then incubated for 1 h with fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody diluted 300-fold. To visualize actin filaments, the permeabilized sections were incubated directly in 330 nM Alexa 488 phalloidin in PBS for 1 h. The sections were washed with PBST and twice with PBS. A drop of FluoroGuard Anti-Fade reagent (Bio-Rad) was added to the sections and examined by laser scanning confocal microscopy as described (Muench et al., 2000).

Upon request, materials integral to the findings presented in this publication will be made available in a timely manner to all investigators on similar terms for noncommercial research purposes. To obtain materials, please contact T. W. Okita, okita@wsu.edu.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert H. Singer (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) for the generous use of pG14-MS2-GFP and pSL-MS2-6, James Carrington (Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR) for pRTL2 plasmid, and Fumio Takaiwa (National Institute of Agrobiological Resources, Tsukuba, Japan) for the prolamine promoter Pprol. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.013466.

Footnotes

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Ainger, K., Avossa, D., Diana, A.S., Barry, C., Barbarese, E., and Carson, J.H. (1997). Transport and localization elements in myelin basic protein mRNA. J. Cell Biol. 138, 1077–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainger, K., Avossa, D., Morgan, F., Hill, S.J., Barry, C., Barbarese, E., and Carson, J.H. (1993). Transport and localization of exogenous myelin basic protein mRNA microinjected in oligodendrocytes. J. Cell Biol. 123, 431–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arn, E., and Macdonald, P. (1998). Motor driving mRNA localization: New insights from in vivo imaging. Cell 95, 151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarese, E., Koppel, D.E., Deutscher, M.P., Smith, C.L., Ainger, K., Morgon, F., and Carson, J.H. (1995). Protein translation components are colocalized in granules in oligodendrocytes. J. Cell Sci. 108, 2761–2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashirullah, A., Cooperstock, R.L., and Lipshitz, H.D. (1998). RNA localization in development. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 335–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell, G., and Singer, R.H. (1997). mRNA and cytoskeletal elements. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9, 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell, G.J., Oleynikov, Y., and Singer, R.H. (1999). The travels of mRNAs through all cells large and small. FASEB J. 13, 447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, E., Chartrand, P., Schaefer, M., Shenoy, S.M., Singer, R.H., and Long, R.M. (1998). Localization of ASH1 mRNA particles in living cells. Mol. Cell 2, 437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, K., and Beach, D.L. (1999). mRNA localization: Motile RNA, asymmetric anchors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2, 604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boevink, P., Oparka, K., Santa Cruz, S., Martin, B., Betteridge, A., and Hawes, C. (1998). Stacks on tracks: The plant Golgi apparatus traffics on an actin/ER network. Plant J. 15, 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogucka-Glotzer, J., and Ephrussi, A. (1996). mRNA localization and the cytoskeleton. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 7, 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, J.H., Kwon, S., and Barbarese, E. (1998). RNA trafficking in myelinating cells. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 8, 607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson, J.H., Worboys, K., Ainger, K., and Barbarese, E. (1997). Translocation of myelin basic protein mRNA in oligodendrocytes requires microtubules and kinesin. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 38, 318–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand, P., Singer, R.H., and Long, R.M. (2001). RNP localization and transport in yeast. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.-B., Wang, C., Muench, D.G., Ozawa, K., Franceschi, V.R., Wu, Y., and Okita, T. (2000). Messenger RNA targeting of rice seed storage proteins to specific ER subdomains. Nature 407, 765–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, E., Fillingham, B.D., and Abe, S. (1996). The plant cytoskeleton. In The Cytoskeleton, J.E. Hesketh and I.F. Pryme, eds (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press), pp. 405–409.

- Davies, E., Fillingham, B.D., Oto, Y., and Abe, S. (1991). Evidence for the existence of cytoskeleton-bound polysomes in plants. Cell Biol. Int. Rep. 15, 973–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.J., and Vierstra, R.D. (1998). Soluble, highly fluorescent variants of green fluorescent protein (GFP) for use in higher plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 36, 521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, G., and Lee, J. (1977). The growth of detached wheat heads in liquid culture. Plant Sci. Lett. 9, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandon, D., Elphick, L., Nusslein-Volhard, C., and St. Johnston, D. (1994). Staufen protein associates with the 3′UTR of bicoid mRNA to form particles that move in a microtubule-dependent manner. Cell 79, 1221–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandon, D., Koch, I., Westhof, E., and Nusslein-Volhard, C. (1997). RNA-RNA interaction is required for the formation of specific bicoid mRNA 3′ UTR-STAUFEN ribonucleoprotein particles. EMBO J. 16, 1751–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forristall, C., Pondel, M., Chen, L.H., and King, M.L. (1995). Patterns of localization and cytoskeletal association of two vegetally localized RNAs, Vg1 and Xcat-2. Development 121, 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, D., Accornero, N., Lavoie, B., Shenoy, S.M., Blanchard, J.-M., Singer, R.H., and Bertrand, E. (2003). Single mRNA molecules demonstrate probabilistic movement in living mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 13, 161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, S., Ishiyama, K., Sakulsingharo, C., Choi, S.-B., Wu, Y., Hwang, C., Singh, S., Kawai, N., Messing, J., and Okita, T.W. (2003). Dual regulated RNA transport pathways to the cortical region in developing rice endosperm. Plant Cell 15, 2265–2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood, V., Kragler, F., and Lucas, W.J. (2002). Plasmodesmata: Pathways for protein and ribonucleoprotein signaling. Plant Cell 14 (suppl.), S303.–S325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh, J.E., and Pryme, I.F. (1991). Interaction between mRNA, ribosomes and the cytoskeleton. Biochem. J. 277, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, R.P. (1999). RNA-cytoskeletal associations. FASEB J. 13, 455–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, R.P. (2001). mRNA localization: Message on the move. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedd, G., and Chua, N.H. (2002). Visualization of peroxisomes in living plant cells reveals acto-myosin-dependent cytoplasmic streaming and peroxisome budding. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.T., Franceschi, V.R., Krishnan, H.B., and Okita, T.W. (1988). Formation of wheat protein bodies: Involvement of the Golgi apparatus in gliadin transport. Planta 173, 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc, M., and Etkin, L.D. (1995). Two distinct pathways for the localization of RNAs at the vegetal cortex in Xenopus oocytes. Development 121, 287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc, M., Zearfoss, N.R., and Etkin, L.D. (2002). Mechanisms of subcellular mRNA localization. Cell 108, 533–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, R.B., Sabry, J.H., Martone, M.E., Deerinck, T.J., Ellisman, M.H., Bassell, G.J., and Kosik, K.S. (1996). Translocation of RNA granules in living neurons. J. Neurosci. 16, 7812–7820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky, A.M., and Kosik, K.S. (2001). Neuronal RNA granules: A link between RNA localization and stimulation-dependent translation. Neuron 32, 683–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenk, R., and Penman, S. (1979). The cytoskeletal framework and poliovirus metabolism. Cell 16, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Franceschi, V.R., and Okita, T.W. (1993). Segregation of storage protein mRNAs on the rough endoplasmic reticulum membranes of rice endosperm cells. Cell 72, 869–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, R.M., Singer, R.H., Meng, X., Gonzalez, I., Nasmyth, K., and Jansen, R.-P. (1997). Mating type switching in yeast controlled by asymmetric localization in ASH1 mRNA. Science 277, 383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouland, A.J., Xu, H., Cui, H., Krueger, W., Munro, T.P., Prasol, M., Mercier, J., Rekosh, D., Smith, R., Barbarese, E., Cohen, E.A., and Carson, J.H. (2001). RNA trafficking signals in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2133–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muench, D.G., Chuong, S.D.X., Franceschi, V.R., and Okita, T.W. (2000). Developing prolamine protein bodies are associated with the cortical cytoskeleton in rice endosperm cells. Planta 211, 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T., and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473.–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nebenfuhr, A., Gallagher, L.A., Dunahay, T.G., Frohlick, J.A., Mazurkiewicz, A.M., Meehl, J.B., and Staehelin, L.A. (1999). Stop-and-go movements of plant Golgi stacks are mediated by the acto-myosin system. Plant Physiol. 121, 1127–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita, T.W., and Choi, S.-B. (2002). mRNA localization in plants: Targeting to the cell's cortical region and beyond. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleynikov, Y., and Singer, R.H. (2003). Real-time visualization of ZBP1 association with beta-actin mRNA during transcription and localization. Curr. Biol. 13, 199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, I.M., and Johnston, D.S. (2001). Getting the message across: The intracellular localization of mRNAs in higher eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 569–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokrywka, N.J. (1995). RNA localization and the cytoskeleton in Drosophila oocytes. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 31, 139–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reck-Peterson, S.L., Provance, D.W., Jr., Mooseker, M.S., and Mercer, J.A. (2000). Class V myosins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1496, 36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, A., and Day, I. (2001). Analysis of the myosins encoded in the recently completed Arabidopsis thaliana genome sequence. Genome Biol. 2, RESEARCH0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook, M.S., Lu, M., and Kosik, K.S. (2000). CaMKIIα 3′ untranslated region-directed mRNA translocation in living neurons: Visualization by GFP linkage. J. Neurosci. 20, 6385–6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, W.M. (2001). Microtubules, motors, and mRNA localization mechanisms: Watching fluorescent messages move. Cell 107, 707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shestakova, E.A., Singer, R.H., and Condeelis, J. (2001). The physiological significance of beta-actin mRNA localization in determining cell polarity and directional motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7045–7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer, R.H. (1993). RNA zipcodes for cytoplasmic addresses. Curr. Biol. 3, 719–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steebings, H. (2001). Cytoskeleton-dependent transport and localization of mRNA. Int. Rev. Cytol. 211, 1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundell, C.L., and Singer, R.H. (1990). Actin mRNA localizes in the absence of protein synthesis. J. Cell Biol. 111, 2397–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa, P.A., Sil, A., Swedlow, J.R., Herskowitz, I., and Vale, R.D. (1997). Actin-dependent localization of an RNA encoding a cell-fate determinant in yeast. Nature 389, 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa, P.A., and Vale, R.D. (2000). The myosin motor, Myo4p, binds Ash1 mRNA via the adapter protein, She3p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5273–5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekotte, H., and Davis, I. (2002). Intracellular mRNA localization: Motors move messages. Trends Genet. 18, 636–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, J.E., and Vale, R.D. (1993). RNA on the move: The mRNA localization pathway. J. Cell Biol. 123, 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, G.S., and Davis, I. (2001). Drosophila wingless and pair-rule transcripts localize apically by dynein-mediated transport of RNA particles. Cell 105, 209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.-Y., Adachi, T., Hatano, T., Washida, H., Suzuki, A., and Takaiwa, F. (1998). Promoters of rice seed storage protein genes direct endosperm-specific gene expression in transgenic rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 39, 885–889. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z., Kawagoe, Y., Xiao, S., Li, Z., Okita, T., Hau, T.H., Lin, A., and Murai, N. (1993). 5′ distal and proximal cis-acting regulator elements are required for developmental control of a rice seed storage protein glutelin gene. Plant J. 4, 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.