Abstract

In addition to its role in controlling cell cycle progression, the tumor suppressor protein p53 can also affect other cellular functions such as cell migration. In this study, we show that p53 deficiency in mouse embryonic fibroblasts cultured in three-dimensional matrices induces a switch from an elongated spindle morphology to a markedly spherical and flexible one associated with highly dynamic membrane blebs. These rounded, motile cells exhibit amoeboid-like movement and have considerably increased invasive properties. The morphological transition requires the RhoA–ROCK (Rho-associated coil-containing protein kinase) pathway and is prevented by RhoE. A similar p53-mediated transition is observed in melanoma A375P cancer cells. Our data suggest that genetic alterations of p53 in tumors are sufficient to promote motility and invasion, thereby contributing to metastasis.

Introduction

A critical event during tumorigenesis is the conversion from a static primary tumor to an invasive, disseminating metastasis. Moreover, tumor cells show an increased capacity to migrate. Numerous intracellular signaling molecules have been implicated in migratory processes. Among them, the Rho GTPase family plays a pivotal role in regulating the biochemical and cytoskeletal pathways relevant to cell migration. The Rho GTPases Rac, Cdc42, and Rho control cell protrusions during migration. Aberrant regulation of Rho proteins is believed to associate with metastasis by promoting cell motility (Clark et al., 2000; Evers et al., 2000; Jaffe and Hall, 2002; Steeg, 2003).

The bona fide environment for migrating cells is the extracellular matrix, which permits movement in a 3D scaffold that is biochemically complex and shows dynamic flexibility. 3D tissue culture models reconstitute an environment that resembles the in vivo situation in regard to cell shape and movement. This model provides important insights into the mechanisms of cell motion during carcinogenesis. Recent advances have identified two modes of cell motility in 3D matrices. The elongated mode of migration is a consequence of Rac activity and generates membrane protrusions, the lamellipodia that drive motility. In contrast, a novel rounded mode of motility depends on RhoA and its main effector, Rho-associated coil-containing protein kinase (ROCK), and resembles the amoeboid movement. This involves a rounded bleb-associated movement that generates propulsive motion through the matrix independently of proteolysis (Sahai and Marshall, 2003).

Curiously, genes encoding Rho GTPases are rarely found mutated in human cancers, in which only their functional activities seem to be deregulated (Nakamoto et al., 2001; Rihet et al., 2001). This suggests that alterations in others genes account for functional modifications of Rho GTPases accompanying actin cytoskeleton remodeling during metastasis. We hypothesize that this set of genes controls the cell cycle. Their mutation during the initiation phase in cancer would modify the behavior of proteins involved in actin cytoskeleton dynamics, such as Rho GTPases, leading to a migratory and invasive phenotype.

Beyond these genes is the tumor suppressor p53, whose mutations occurs in >50% of human tumors (Hollstein et al., 1994). p53 protects cells from malignant transformation by regulating cell cycle arrest or by promoting apoptosis (Levine, 1997; Giaccia and Kastan, 1998). We and others have recently shown that p53 modulates cell migration: p53 negatively modulates Rho GTPases and regulates cell polarization and migration (Gadea et al., 2002, 2004; Guo et al., 2003). However, little is known about the role of p53 in cells moving in a 3D matrix that mimics the in vivo microenvironment of tumor cells.

Identifying the mechanisms by which p53 modulates cell migration is important to understand how invasive cells arise. In this study, we show that the elongated spindle-shaped fibroblastoid mode of motility can be converted to a rounded blebbing movement by blocking p53 function. This amoeboid mode of motility requires RhoA–ROCK signaling and confers higher velocity and invasive properties to p53-deficient cells. Thus, the range of p53 tumor suppressor activity extends to the control of the mode of migration of invasive cells.

Results and discussion

p53−/− fibroblasts show rounded blebbing movement

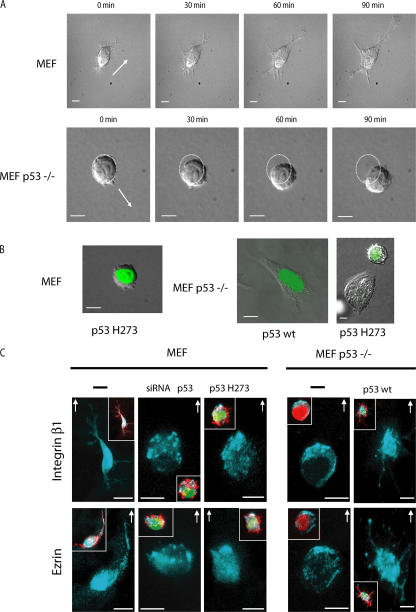

Initially, we compared the movement of p53-deficient primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs; p53−/− MEFs) with that of wild-type (wt) MEFs cultured in 3D Matrigel matrix using time-lapse video microscopy. The migration of the two cell types is strikingly different (Fig. 1 A and Videos 1 and 2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701120/DC1). wt MEF maintained a spindle-shaped elongated morphology, generated extensions, and moved slowly at 2 ± 1 μm/h−1, whereas p53−/− MEF moved as rounded cells using a translatory motion in the direction of the serum growth factor gradient. They show many dynamic bleblike structures, alternating rapid cycles of squeezing and expansion, and considerable deformability. p53−/− cells moved at 12 ± 5 μm/h−1, maintaining their rounded morphology. Expression of the GFP-tagged mutant p53 H273, a dominant-negative form of p53, converts the elongated morphology of MEF to a marked spherical and flexible one associated with highly dynamic membrane blebs similar to those observed in p53−/− MEFs (Fig. 1 B and Video 3). The expression of GFP-tagged wt p53 in p53−/− MEFs inhibits dynamic blebbing and leads to an elongated morphology (Fig. 1 B and Video 4), whereas that of GFP-tagged p53 H273 has no effect. Thus, the loss of wt p53 activity is sufficient to drive the switch from an elongated fibroblast-like to a rounded type of migration.

Figure 1.

Rounded blebbing movement is provoked by p53 deficiency. (A) Time-lapse analysis of MEFs and p53−/− MEFs moving within Matrigel. Still DIC time-lapse images from accompanying videos of wt MEFs (Video 1) and p53−/− MEFs (Video 2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701120/DC1). Cells were plated into a thick layer of Matrigel, and a gradient of serum growth factors was established. Frames show the cell migration at the indicated times. Arrows indicate the direction of cell movement. Dotted circles indicate the initial situation of the cell when the video starts. (B) Time-lapse analysis of the different modes of cell motility within Matrigel. DIC images of cells transfected with GFP-tagged plasmids (to enable the identification of transfected cells as visualized in green) expressing either p53 H273 in MEFs (still images from Video 3), p53 wt in p53−/− MEFs (still images from Video 4), or p53 H273 in p53−/− MEFs as control (right). Cells were plated within Matrigel as in A. (C) p53 regulates subcellular distributions of integrin β1 and ezrin in rounded migrating cells. Representative integrin β1 and ezrin fluorescent staining of MEFs and p53−/− MEFs transfected with p53 wt, p53 H273, siRNA p53, or plasmid EGFP. Insets show the covisualization of F-actin (red), GFP (green), and ezrin or integrin β1 (blue) as indicated. Cells were plated in Matrigel, and a gradient of serum growth factors was established. Arrows show the direction of cell movement in Matrigel. Bars, 10 μm.

In Matrigel, cells moving with a rounded or elongated morphology show a distinct subcellular distribution of integrin β1 and ezrin that helps in establishing the direction of movement (Sahai and Marshall, 2003). In Matrigel, rounded blebbing MEFs that arise from p53 inactivation show integrin β1 and ezrin relocalization to the moving front of the cell. A similar clustering was also observed in rounded p53−/− MEFs. In contrast, conversion of p53−/− MEFs to elongated morphology by the expression of p53 wt led to their relocalization throughout the cell, notably in the newly formed long extensions (Fig. 1 C). Thus, p53 controls the clustering of integrin β1 and ezrin in rounded cells.

Culture of fibroblastic cells in monolayers imposes an artificial polarity between the lower and upper surface of these apolar cells. Their morphology and migration change in a 3D matrix, suggesting that the spatial constraints and surrounding biochemical microenvironment are a better approximation of the in vivo situation (Friedl and Brocker, 2000; Cukierman et al., 2001). This is particularly striking for p53-deficient MEFs that become blebbing spherical cells once suspended in 3D matrices, losing their initial fibroblastoid morphology observed in 2D culture.

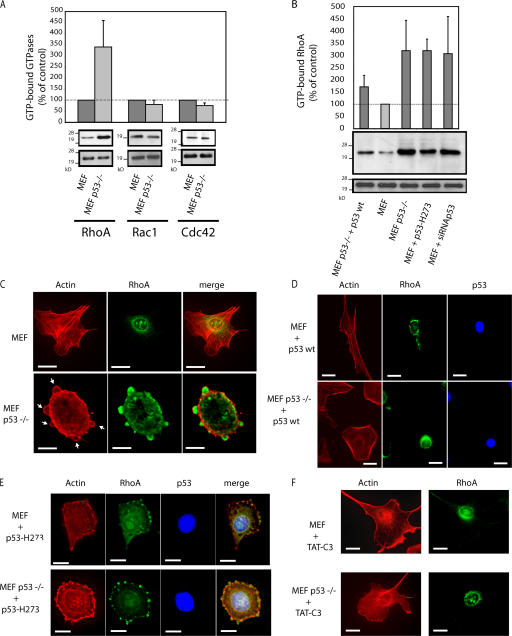

RhoA activity is enhanced in p53−/− MEFs

This rounded blebbing movement observed in p53−/− MEFs is strikingly similar to amoeboid-like motility, which is dependent on Rho–ROCK signaling in a 3D matrix (Sahai and Marshall, 2003). We compared the level of GTP-bound RhoA in p53−/− and wt MEFs. GTP-RhoA was increased 3.4-fold in p53−/− MEFs, whereas GTP-Rac and Cdc42 were barely affected (Fig. 2 A). This change was functional because protein expression levels were unaltered by p53 deletion. Reintroduction of wt p53 in p53−/− MEFs lowered the level of GTP-RhoA to that of wt MEFs (Fig. 2 B). Conversely, p53 H273 did not affect the overactivation of RhoA in p53−/− MEFs. Finally, blocking p53 in MEFs using p53 H273 or siRNA-mediated knockdown of p53 was sufficient to increase GTP-RhoA (Fig. 2 B). These results show that wt p53 inhibits RhoA activation and has a role in regulating RhoA signaling pathways.

Figure 2.

p53 regulates RhoA activation. (A) GTPase activities in wt MEFs and p53−/− MEFs. Cells were lysed 24 h after plating, and the levels of GTP-bound RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 were assayed. (B) RhoA activity in transfected MEFs and p53−/− MEFs. Cells transfected with p53 wt and p53 H273 were assayed for RhoA activity. (A and B) The values are the mean ± SD (error bars) of three independent experiments. (C–F) Representative F-actin and RhoA fluorescent staining of wt MEFs and p53−/− MEFs untreated (C), treated with TAT-C3 (F), or transfected with plasmids expressing either p53 wt (D) or p53 H273 (E). Panels show phalloidin-stained F-actin (red) and RhoA labeling (green). Arrows point to blebbing structures. Bars, 10 μm.

Distinct localization of RhoA in p53−/− MEFs

Translocation from the cytoplasm to the membrane area is essential for both the activation and function of RhoA (Takaishi et al., 1995). We compared the localization of RhoA and filamentous actin (F-actin) in p53−/− and wt MEFs. In wt MEFs, RhoA exhibits a punctuate distribution throughout the cytoplasm with a marked concentration in the perinuclear region. F-actin stress fibers cross the cytoplasm and accumulate slightly around the edge of the cell (Fig. 2 C, top). In p53−/− MEFs, RhoA shows its punctuate cytoplasmic localization but is excluded from the perinuclear region (Fig. 2 C, bottom). Instead, RhoA colocalizes with large patches of polymerized actin in bleblike globular structures that are distributed over and protruding from the cell surface (Fig. 2 C, arrows). In addition, MEFs lacking p53 activity show more peripheral microspikes, which were previously characterized as filopodia (Gadea et al., 2002). They also show an accumulation of peripheral polymerized actin bundles (i.e., a redistribution of F-actin stress fibers; Fig. 2 C). The expression of wt p53 led to loss of the bleblike protrusions and recovery of the punctuate RhoA localization in the perinuclear region. This was not seen with p53 H273, indicating that wt p53 activity is required for RhoA localization (Fig. 2, compare D with E). Treatment of p53−/− MEFs with TAT-C3, which inactivates RhoA, RhoB, and RhoC (Coleman et al., 2001), abolished bleblike structures and led to RhoA redistribution in the perinuclear region (Fig. 2 F). Thus, RhoA activation is required for bleb formation in p53−/− cells.

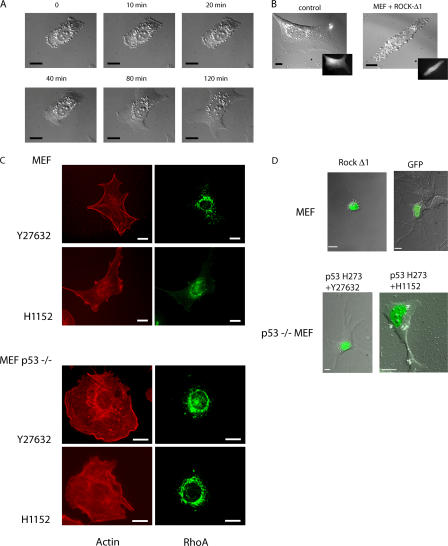

p160 ROCK controls morphological changes observed in p53−/− fibroblasts

RhoA-driven actin reorganization largely depends on the serine–threonine protein kinase ROCK (Amano et al., 1997; Ishizaki et al., 1997). To determine whether ROCK mediates membrane blebbing in p53−/− MEFs cultured in monolayer, we used Y27632 and H1152, which are two distinct, structurally unrelated pharmacological inhibitors of ROCK. p53−/− MEFs promptly lost their extensive dynamic bleblike activities and their rounded morphology within 40 min, adopting a flattened, spread shape when treated with Y27632 (Fig. 3 A and Video 5, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701120/DC1) or H1152 (not depicted). Consistent with this, the expression of ROCK-Δ1, an active mutant, in wt MEF promoted a rounded morphology accompanied by numerous dynamic bleblike extensions similar to p53−/− MEF (Fig. 3 B and Video 6). GFP alone had no effect (Fig. 3 B). The spreading of p53−/− MEFs induced by Y27632 or H1152 was accompanied by the reorganization of F-actin from cortical bundles into scattered cytoplasmic dotlike structures concomitant with the loss of filopodia (Fig. 3 C). Similar to other studies (Ishizaki et al., 2000; Totsukawa et al., 2000), ROCK inhibitors strongly reduced the number of stress fibers in both wt and p53−/− MEFs. In addition, ROCK inhibition in p53−/− MEFs led to RhoA relocalization to the perinuclear region (compare Fig. 3 C with Fig. 2 C). Thus, ROCK inhibition causes RhoA to lose its membrane localization.

Figure 3.

ROCK activity is required for rounded blebbing morphology driven by p53 deficiency. (A) Still DIC time-lapse images from Video 5 (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701120/DC1) of p53−/− MEFs treated with Y27632. Frames show the spreading of a p53−/− MEF at the indicated times. (B) DIC images show wt MEFs cotransfected with GFP to identify transfected cells (insets) and ROCK-Δ1 (still images from Video 6; Fig. S1) or with GFP alone as a control. (C) Representative F-actin and RhoA fluorescent staining of wt MEFs and p53−/− MEFs treated either with Y27632 or H1152. (D) Time-lapse analysis of different modes of cell motility within Matrigel. Still DIC images of MEFs transfected either with ROCK-Δ1 (still DIC images from Video 7) or GFP alone as a control. (bottom) Still DIC images of p53−/− MEFs treated with Y27632 or H1152 and transfected with p53 H273 (from Video 8 and Video 9, respectively). The transfected cells expressing either ROCK-Δ1 or p53 H273 are visualized using GFP. Cells were plated within Matrigel as in Fig. 1. Bars, 10 μm.

We tested whether ROCK activity is required for the rounded blebbing movement of p53−/− MEFs cultured in Matrigel. Transfection of ROCK-Δ1 converts MEFs from an elongated to a rounded blebbing morphology; GFP alone had no effect (Fig. 3 D and Video 7, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701120/DC1). In contrast, treatment of p53−/− MEFs with Y27632 or H1152 inhibits dynamic blebbing and leads to an elongated morphology even upon the expression of p53 H273 (Fig. 3 D and Videos 8 and 9). This transition is accompanied by the redistribution of integrin β1 and ezrin to the moving front of the cell (Fig. S1). Thus, ROCK activity is required for the amoeboid-like rounded morphology driven by p53 deficiency.

Collectively, our results indicate that characteristics of the fibroblast type of motility (i.e., that using elongation and traction) are lost when p53 function is abrogated using either p53 H273 or siRNA. Cells adopt a rounded bleb morphology similar to that observed in p53−/− MEFs cultured in 3D matrices. A p53 defect leads to the aberrant overactivation of RhoA, which consequently translocates to specific membrane blebbing structures. Importantly, we show that the RhoA–ROCK signaling pathway is involved in p53-dependent morphological changes by modulating round blebbing. It also appears to promote blebbing in p53−/− cells. Notably, RhoA signaling through ROCK was previously shown to be important in the rounded blebbing movement but not for the elongated protrusive movement of cancer cells cultured in 3D matrices (Sahai and Marshall, 2003).

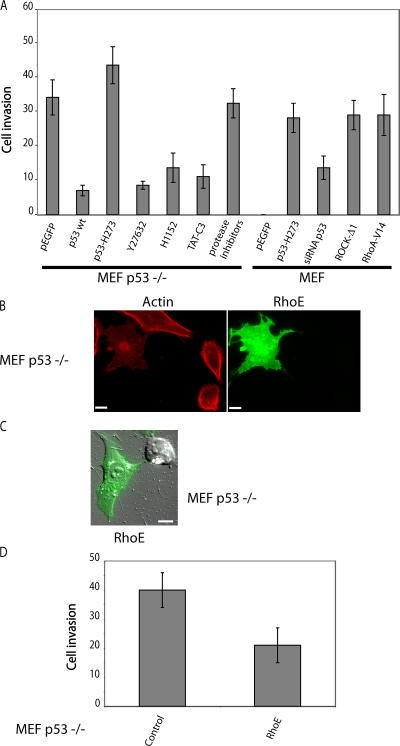

Invasion of p53-deficient cells requires ROCK activity and is prevented by RhoE

RhoA–ROCK signaling also plays a key role in invasion by blebbing cells moving in 3D matrix (Sahai and Marshall, 2003). Similarly, p53−/− MEFs, which have an overactivation of this pathway, showed substantially higher invasiveness than wt MEFs in Matrigel (Fig. 4 A). Inhibition of Rho or ROCK by treatment with TAT-C3, Y27632, or H1152 diminished the ability of p53−/− MEFs to invade Matrigel by around 60%. Expression of wt p53 but not p53 H273 blocked this behavior.

Figure 4.

p53 controls cell invasion through the RhoA–ROCK pathway. (A) Matrigel invasion of wt MEFs and p53−/− MEFs. Cells were treated with either TAT-C3, Y27632, H1152, or protease inhibitors or were transfected with plasmids encoding either p53 wt, p53 H273, siRNA p53, ROCK-Δ1, or RhoA-V14 as indicated. The changes in Matrigel invasion were analyzed as described in Materials and methods. For each data point, GFP-positive cells were scored. (B) Representative RhoE and actin fluorescent staining of p53−/− MEFs transfected with GFP-RhoE. (C) DIC images of p53−/− MEFs transfected with GFP-tagged RhoE (still images from Video 10, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701120/DC1). Cells were plated in Matrigel as in Fig. 1 A. (D) Matrigel invasiveness of p53−/− MEFs transfected either with vector alone (control) or with RhoE. Quantification was performed as in A. (A and D) Values are the means ± SD (error bars) of three independent experiments. Bars, 10 μm.

The ability of MEFs to invade Matrigel was increased when p53 activity was blocked either by expression of the H273 p53 mutant or using siRNA to p53 in MEFs. Similarly, invasiveness was enhanced by an active mutant of RhoA (RhoA-V14) and ROCK-Δ1. Invasiveness of blebbing cells is independent of protease activities (Sahai and Marshall, 2003); accordingly, the invasive activity of p53−/− MEFs was unaffected by the inhibition of proteases. Thus, the Rho–ROCK signaling module is necessary for the invasive behavior of p53−/− cells in Matrigel.

RhoE, a member of the Rho family that blocks actin stress fibers (Guasch et al., 1998; Nobes et al., 1998), is a transcriptional target of p53 in response to genotoxic stress; RhoE promotes cell survival through the inhibition of ROCK1-mediated apoptosis (Ongusaha et al., 2006). The overexpression of RhoE clearly prevented actin polymerization and abolished the bleblike protrusions in p53−/− MEFs, converting them to an elongated morphology (Fig. 4, B and C; and Video 10, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701120/DC1). RhoE also considerably reduced the invasiveness of p53−/− MEFs (Fig. 4 D), suggesting that RhoE helps mediate the control of cell morphology and invasiveness by p53.

p53 inactivation promotes rounded blebbing movement in A375P melanoma cancer cells

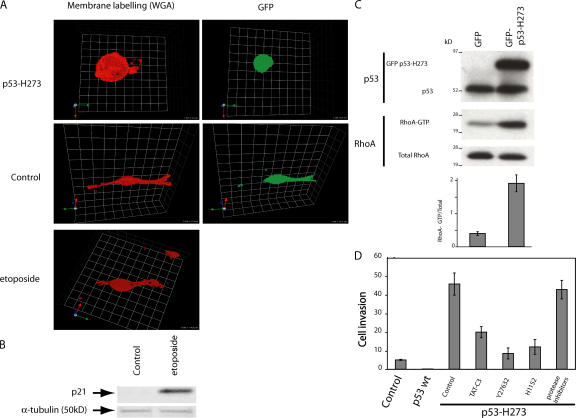

We sought to extend these observations to cancer cells. We chose A375P melanoma cells, which have a wt form of p53 and show an elongated mode of migration in 3D matrix (Sahai and Marshall, 2003). Cell morphology was visualized using fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin, which provides highly selective labeling of the external plasma membrane. The expression of GFP-tagged p53 H273 confers a rounded blebbing morphology to A375P cells, which associates with membrane blebs similar to those observed in p53−/− MEFs (Fig. 5 A). In contrast, the elongated morphology of A375P was unchanged when p53 accumulation was induced by etoposide, which was verified using the induction of p21WAF, a transcriptional target of p53 (Fig. 5 B). These morphologic changes correlated with the level of GTP-RhoA, which was 4.6-fold higher upon the expression of p53 H273 (Fig. 5 C). Thus, the amoeboid-like motility of A375P melanoma cells induced by the loss of p53 activity is dependent on RhoA activation.

Figure 5.

A375 melanoma cell invasiveness is regulated by p53 activity. (A) Confocal images of A375P cells expressing plasmid EGFP alone or p53 H273. Cells were plated in Matrigel, and a gradient of serum growth factors was established to observe the mode of migration. The transfected cells are visualized using GFP, and plasma membranes were labeled with fluorescent WGA (wheat germ agglutinin; red). (B) p21 induction in A375P cells. A375P cells were untreated or treated with etoposide. Total protein lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis using antibodies to p21. Normalization was performed with an anti–α-tubulin antibody. (C) RhoA activity in transfected A375P. Cells expressing GFP-tagged p53 H273 or plasmid EGFP (control) were compared for GTP-RhoA levels as in Fig. 2. The image is representative of three independent experiments. The values are the mean ± SD (error bars). (D) Invasiveness in 3D matrigel matrix of A375P-expressing p53 wt or p53 H273 treated with TAT-C3, Y27632, or H1152 as indicated. Results are expressed as in Fig. 4.

Amoeboid cancer cell motility is particularly efficient in promoting the invasiveness of metastatic cells in 3D environments. Therefore, we performed invasion assays in Matrigel using this model. The expression of p53 H273 strongly increased the invasiveness of A375P, whereas wt p53 inhibited it (Fig. 5 D). TAT-C3, Y27632, or H1152 treatment largely reduced this response in p53 H273–expressing A375P cells, arguing that mutated p53 drives this behavior through RhoA–ROCK signaling. In contrast, protease inhibition did not alter p53 H273–driven invasiveness (Fig. 5 D). This stresses the role of the amoeboid-like rounded morphology of p53-deficient A375P cells in their invasive potential.

Our results show that blocking p53 function is sufficient to convert melanoma cells to a rounded locomotion, indicating that cancer cells may also be subject to this regulation. This switch would favor the illegitimate dissemination of cancer cells containing mutant p53, possibly increasing their invasiveness.

The tumor suppressor p53 is mutated in >50% of human cancers (Hollstein et al., 1994) and, thus, constitutes an appealing target for anticancer therapy. Diverse therapeutic strategies already exist that attempt to restore wt p53 function in cancer cells, including the rescue of mutant p53 function and reactivation of wt p53 (Blagosklonny, 2002). Given that there is no obvious selection for a metastatic phenotype, Bernards and Weinberg (2002) proposed that classic oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes implicated in the early stages of tumorigenesis may also play a role in metastasis. Our studies indicate that p53 is an ideal candidate, as it is involved both in the control of tumor cell apoptosis and tumor cell invasion. This extends the applications for anticancer agents aimed at restoring p53 wt functions: such agents may combine antiproliferative and antiinvasive activities.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, transfection, plasmids, reagents, and Rho GTPase activity assays

wt and p53−/− MEFs were generated, cultured, and transfected as previously described (Gadea et al., 2002). A375P cells were cultured in DME with 10% FCS and transfected using electroporation (Nucleofector; Amaxa). In brief, 106 cells were suspended in 100 μl of solution R and mixed with 3 μg DNA for electroporation (program T-016). The primary antibodies used were anti-p21 (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-p53 (DO-1; Novocastra), and anti–α-tubulin (DM1A; Sigma-Aldrich). The inhibitors used were 10 μM Y27632 (Calbiochem) and 5 μM H1152 (Calbiochem). Etoposide (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 25 μg/ml−1. GFP-tagged p53 wt and p53 H273 were previously described (Gadea et al., 2002). pSuper-siRNA p53 and plasmid EGFPC1-RhoE were gifts from J.-C. Bourdon (University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland, UK) and Ph. Fort (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Montpellier, France), respectively. The Rho GTPase activities were processed as previously described (Gadea et al., 2002).

Invasion assay

The quantification of cell invasion was performed in transwell cell culture chambers containing fluorescence-blocking polycarbonate porous membrane inserts (pore size of 8 μm; Fluoroblock; BD Biosciences). 100 μl Matrigel with reduced growth factors (a commercially prepared reconstituted basement membrane from Englebreth-Holm-Swarm tumors; BD Biosciences) were prepared in a transwell. Cells were transfected and treated with TAT-C3 for 16 h and Y27632 or H1152 for 2 h as monolayer before trypsinization and plating (5 × 104) in serum-free media on top of a thick layer (around 500 μm) of Matrigel contained within the upper chamber of a transwell. Controls were left untreated. The upper and lower chambers were then filled with serum-free DME and DME with 10% FCS, respectively, thus establishing a soluble gradient of chemoattractant that permits cell invasion throughout the Matrigel. Inhibitors were added immediately after cell plating at the aforementioned concentrations. Cells were allowed to invade at 37°C and 5% CO2 through the gel for 36 h (for MEF and p53−/− MEF) or for 24 h (for A375P) before fixing for 15 min in 3.7% formaldehyde. Cells that had invaded through the Matrigel were detected on the lower side of the filter by GFP fluorescence and counted for cell number. Six fields per filter were counted, and each assay was performed twice in triplicate for each cell line.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were transfected and/or treated with TAT-C3, Y27632, or H1152 on coverslips at a confluence of ∼30% before fixation in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS followed by a 5-min permeabilization in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and were incubated in PBS containing 0.1% BSA before staining with primary antibodies as follows: RhoA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), antiezrin polyclonal antibody (provided by P. Mangeat, Centre de Recherche en Biochimie Macromoléculaire, Montpellier, France), and integrin β1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). All of the antibodies were revealed with either an AlexaFluor546- or -488–conjugated goat anti–mouse or anti–rabbit antibody (Invitrogen and Interchim). Cells were stained for F-actin using TRITC-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich) or for membrane morphology using cell-impermeant AlexaFluor594 wheat germ agglutinin, which binds selectively to N-acetylglucosamin and N-acetylneuraminic (sialic) acid residues and provides highly selective labeling of the plasma membrane (Invitrogen). Cells were prepared as described previously (Gadea et al., 2002). Stacks of 16-bit fluorescent images (z step of 0.1 μm) were captured with a MetaMorph-driven microscope (DMRB; Leica) using a 63× NA 1.4 Apochromat oil immersion objective (Leica), a piezo stepper (E662; Physik Instruments), and a camera (CoolSNAP HQ2; Photometrics). Epifluorescence of all images (in 2D and 3D) were restored and deconvolved with Huygens (Scientific Volume Imaging) using the maximum likelihood estimation algorithm. Restored stacks were processed with Imaris (Bitplane) for visualization. The restored images were saved as tiff files that were mounted using Photoshop and Illustrator (Adobe).

Immunofluorescence in 3D matrices

For immunofluorescence of cells in 3D Matrigel network, cultures were transfected and treated with TAT-C3, Y27632, or H1152 as monolayer followed by trypsinization and embedding into Matrigel in transwell cell culture chambers (as previously described in the Invasion assay section except that cells were allowed to invade through the gel for 6 h). Controls were left untreated. 50-μm cryosections were then cut at −20°C before fixation in 4% PFA in PBS followed by a 2-min permeabilization in 0.5% Triton X-100. Immunolabeling with various antibodies was performed as in the previous section. Cells were analyzed using a microscope (LSM510 Meta; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) with a 63× NA 1.32 Apochromat water immersion objective (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) and a photomultiplicator. Stacks of images were captured with LSM510 expert mode and were restored as described in the previous section.

Time-lapse imaging

Time-lapse microscopy was performed on an inverted microscope (DL IRBE; Leica) equipped with differential interference contrast (DIC) and GFP optics using a 63× NA 1.3 oil-immersion objective (Leica), sample heater (37°C), and a CO2 incubation chamber (Leica). Images were captured with a CCD camera (MicroMax 1300; Princeton Instruments) using MetaMorph 6 software (Molecular Devices), converted to tiff files that were edited with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health), and compiled into QuickTime videos (Macintosh). The exposure time was set to 50 ms. All videos were recorded at the frequency of one image every 5 s.

For 3D videos, we devised home-made bicompartment chambers comprised of an 8-mm metal ring placed in the center of a 30-mm Petri dish. The cells were mixed with serum-free Matrigel, and the resultant suspension was poured into the well formed by the metal ring. The assembly was placed in an incubator for 30 min while the Matrigel solidified, after which the metal ring was removed. The resultant disc of Matrigel was surrounded with 10% serum-complemented medium, taking care not to allow any medium to flow on top, thus exposing the cells to a lateral serum gradient. Cells close to the periphery of the Matrigel disc were time lapsed to monitor their ability to migrate along the serum gradient. Z sections recorded over a series of time points were combined into QuickTime videos. Cell velocity (Fig. 1 A) was determined by measuring the speed of 10–12 cells, and the values are the means of three independent experiments.

Online supplemental material

Video 1 shows MEFs move using an elongated mode of motility in 3D matrix. Video 2 shows p53−/− MEFs move using a rounded mode of motility in 3D matrix. Video 3 shows that rounded blebbing movement is provoked by p53 deficiency in 3D matrix. Video 4 shows that elongated movement is driven by p53 activity in 3D matrix. Video 5 shows the spreading of a p53−/− MEF treated with Y27632. Video 6 shows that ROCK-Δ1 promotes a rounded morphology. Video 7 shows that rounded movement is promoted by ROCK-Δ1 in 3D matrix. Videos 8 and 9 show that p53 deficiency–driven rounded morphology depends on ROCK activity in 3D matrix. Video 10 shows that p53 deficiency–driven rounded morphology is prevented by RhoE in 3D matrix. Fig. S1 shows that ROCK mediates p53-dependent regulation of the subcellular distribution of integrin β1 and ezrin in rounded migrating cells cultured in 3D Matrigel. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701120/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Montpellier Rio Imaging for constructive microscopy and to R. Hipskind, C. Marshall, and A. Self for critical comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr. Ph. Fort and Dr. J.-C. Bourdon for providing plasmids.

This work was supported by the Fondation de France, Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (contrat 4028), Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

G. Gadea's present address is Institute of Cancer Research, London SW3 6JB, UK.

Abbreviations used in this study: DIC, differential interference contrast; F-actin, filamentous actin; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; ROCK, Rho-associated coil-containing protein kinase; wt, wild type.

References

- Amano, M., K. Chihara, K. Kimura, Y. Fukata, N. Nakamura, Y. Matsuura, and K. Kaibuchi. 1997. Formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions enhanced by Rho-kinase. Science. 275:1308–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernards, R., and R.A. Weinberg. 2002. A progression puzzle. Nature. 418:823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. 2002. P53: an ubiquitous target of anticancer drugs. Int. J. Cancer. 98:161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, E.A., T.R. Golub, E.S. Lander, and R.O. Hynes. 2000. Genomic analysis of metastasis reveals an essential role for RhoC. Nature. 406:532–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, M.L., E.A. Sahai, M. Yeo, M. Bosch, A. Dewar, and M.F. Olson. 2001. Membrane blebbing during apoptosis results from caspase-mediated activation of ROCK I. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukierman, E., R. Pankov, D.R. Stevens, and K.M. Yamada. 2001. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 294:1708–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers, E.E., R.A. van der Kammen, J.P. ten Klooster, and J.G. Collard. 2000. Rho-like GTPases in tumor cell invasion. Methods Enzymol. 325:403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl, P., and E.B. Brocker. 2000. The biology of cell locomotion within three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57:41–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadea, G., L. Lapasset, C. Gauthier-Rouviere, and P. Roux. 2002. Regulation of Cdc42-mediated morphological effects: a novel function for p53. EMBO J. 21:2373–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadea, G., L. Roger, C. Anguille, M. de Toledo, V. Gire, and P. Roux. 2004. TNF{alpha} induces sequential activation of Cdc42- and p38/p53-dependent pathways that antagonistically regulate filopodia formation. J. Cell Sci. 117:6355–6364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaccia, A.J., and M.B. Kastan. 1998. The complexity of p53 modulation: emerging patterns from divergent signals. Genes Dev. 12:2973–2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guasch, R.M., P. Scambler, G.E. Jones, and A.J. Ridley. 1998. RhoE regulates actin cytoskeleton organization and cell migration. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:4761–4771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F., Y. Gao, L. Wang, and Y. Zheng. 2003. p19Arf-p53 tumor suppressor pathway regulates cell motility by suppression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Rac1 GTPase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14414–14419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollstein, M., K. Rice, M.S. Greenblatt, T. Soussi, R. Fuchs, T. Sorlie, E. Hovig, B. Smith-Sorensen, R. Montesano, and C.C. Harris. 1994. Database of p53 gene somatic mutations in human tumors and cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:3551–3555. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki, T., M. Naito, K. Fujisawa, M. Maekawa, N. Watanabe, Y. Saito, and S. Narumiya. 1997. p160ROCK, a Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein kinase, works downstream of Rho and induces focal adhesions. FEBS Lett. 404:118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki, T., M. Uehata, I. Tamechika, J. Keel, K. Nonomura, M. Maekawa, and S. Narumiya. 2000. Pharmacological properties of Y-27632, a specific inhibitor of rho-associated kinases. Mol. Pharmacol. 57:976–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, A.B., and A. Hall. 2002. Rho GTPases in transformation and metastasis. Adv. Cancer Res. 84:57–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, A.J. 1997. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 88:323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto, M., H. Teramoto, S. Matsumoto, T. Igishi, and E. Shimizu. 2001. K-ras and rho A mutations in malignant pleural effusion. Int. J. Oncol. 19:971–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobes, C.D., I. Lauritzen, M.G. Mattei, S. Paris, A. Hall, and P. Chardin. 1998. A new member of the Rho family, Rnd1, promotes disassembly of actin filament structures and loss of cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 141:187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongusaha, P.P., H.G. Kim, S.A. Boswell, A.J. Ridley, C.J. Der, G.P. Dotto, Y.B. Kim, S.A. Aaronson, and S.W. Lee. 2006. RhoE is a pro-survival p53 target gene that inhibits ROCK I-mediated apoptosis in response to genotoxic stress. Curr. Biol. 16:2466–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Rihet, S., P. Vielh, J. Camonis, B. Goud, S. Chevillard, and J. de Gunzburg. 2001. Mutation status of genes encoding RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 GTPases in a panel of invasive human colorectal and breast tumors. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 127:733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahai, E., and C.J. Marshall. 2003. Differing modes of tumour cell invasion have distinct requirements for Rho/ROCK signalling and extracellular proteolysis. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeg, P.S. 2003. Metastasis suppressors alter the signal transduction of cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 3:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaishi, K., T. Sasaki, T. Kameyama, S. Tsukita, and Y. Takai. 1995. Translocation of activated Rho from the cytoplasm to membrane ruffling area, cell-cell adhesion sites and cleavage furrows. Oncogene. 11:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totsukawa, G., Y. Yamakita, S. Yamashiro, D.J. Hartshorne, Y. Sasaki, and F. Matsumura. 2000. Distinct roles of ROCK (Rho-kinase) and MLCK in spatial regulation of MLC phosphorylation for assembly of stress fibers and focal adhesions in 3T3 fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 150:797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.