Abstract

Measles still remains a major cause of childhood morbidity and mortality worldwide. Measles virus (MV) vaccines are highly successful, but the mechanism underlying their efficacy has been unclear. Here we report the crystal structure of the MV attachment protein, hemagglutinin, responsible for MV entry. The receptor-binding head domain exhibits a cubic-shaped β-propeller structure and forms a homodimer. N-linked sugars appear to mask the broad regions and cause the two molecules forming the dimer to tilt oppositely toward the horizontal plane. Accordingly, residues of the putative receptor-binding site, highly conserved among MV strains, are strategically positioned in the unshielded area of the protein. These conserved residues also serve as epitopes for neutralizing antibodies, ensuring the serological monotype, a basis for effective MV vaccines. Our findings suggest that sugar moieties in the MV hemagglutinin critically modulate virus–receptor interaction as well as antiviral antibody responses, differently from sugars of the HIV gp120, which allow for immune evasion.

Keywords: x-ray crystallography paramyxovirus, morbillivirus, SLAM, infectious disease, paramyxovirus

The family Paramyxoviridae includes a number of important human and animal pathogens (1). Paramyxoviruses have two surface glycoproteins, a receptor-binding attachment protein and a fusion (F) protein. Attachment proteins of many paramyxoviruses (those belonging to the genera Respirovirus, Rubulavirus, and Avulavirus) have both hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (NA) activities and are thus called hemagglutinin–neuramidases (HNs). HNs recognize sialic acid-containing cell surface molecules as receptors and, upon receptor binding, promote fusion activity of the F protein, thereby allowing the virus to penetrate the cell membrane. HNs also act as NAs, removing sialic acid from infected cells and progeny virus particles to allow efficient virus production. The sialic acid recognition of the HN proteins of many paramyxoviruses, as well as of other NA/sialidase derived from a variety of species, has been well studied. Crystal structures of the HN protein from the Newcastle disease virus (NDV), parainfluenza virus 5 (SV5), and human parainfluenza virus 3 (hPIV3), alone and in complex with sialic acid, have been determined (2–4).

By contrast, the attachment protein of measles virus (MV), a member of the genus Morbillivirus, has properties different from those of these proteins. It lacks NA activity (thus called the H, not HN, protein) and uses the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM, also called CD150), instead of sialic acid, as a receptor (5, 6). SLAM is a membrane glycoprotein expressed on cells of the immune system, including activated T and B cells, activated monocytes, and mature dendritic cells. Other morbilliviruses, including canine distemper and rinderpest viruses, also use SLAM as receptors (7). The use of SLAM as a receptor offers a good explanation for both tropism and the immunosuppressive nature of morbilliviruses (6).

MV exhibits the serological monotype (8). Current MV vaccines, the progenies of the first MV isolate obtained half a century ago, are highly successful, and no mutant strains that escape the immune responses induced by the vaccines have been reported (8). Although the molecular basis for the single serotype nature of MV and successful vaccines has been unclear, the knowledge will provide insight into better vaccine design for various infectious diseases.

Despite the availability of efficacious live vaccines, measles remains a major cause of childhood morbidity and mortality, causing 4% of all deaths in children <5 years of age worldwide (9). Antiviral drugs are also desirable for the treatment of MV patients with complications, in particular subacute sclerosing panencephalitis caused by persistent MV infection in the central nervous system.

Here we present the crystal structure of the attachment protein H of MV (MV-H), which is required for viral entry and also serves as the major target for neutralizing antibodies (10). The structure provides the molecular basis for effective vaccination, as well as a framework for structure-based vaccine and antiviral drug design.

Results and Discussion

Expression, Purification, and SLAM Binding of MV-H.

MV-H, like attachment proteins of other paramyxoviruses, is a type II membrane protein consisting of an N-terminal cytoplasmic tail, a transmembrane region, a membrane-proximal stalk domain, and a large C-terminal receptor-binding head domain. Functional studies based on virus infection have shown that the Edmonston (Ed) vaccine strain of MV uses both SLAM and CD46 as receptors (11, 12), whereas most WT strains of MV use only SLAM (8, 13). Biochemical studies of MV-H–receptor interaction, however, have been performed only with MV-H (Ed) (14), not MV-H (WT). We have produced the soluble head domains (residues 149–617) of MV-H (Ed) and MV-H (WT) proteins by transfecting HEK293S cells lacking N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I (GnTI) activity (15) with expression plasmids encoding the respective molecules [see supporting information (SI) Fig. 5]. In this study, we used the IC-B WT strain of MV (16) to prepare MV-H (WT). The protein products exhibited restricted and homogeneous N-glycosylation composed of oligomannose-type sugars: two GlcNAcs and five mannoses (Man5GlcNAc2). Soluble receptor molecules were also produced in HEK293S cells lacking GnTI activity. The surface plasmon resonance-binding study using these soluble proteins provided definitive evidence that, unlike MV-H (Ed), MV-H (WT) fails to bind CD46, whereas both MV-H (WT) and MV-H (Ed) proteins bind SLAM with similar affinities (Kd of 0.29 and 0.43 μM, respectively) and kon and koff rates (Table 1). The results are consistent with functional assays as well as a previous binding study reporting a Kd value of 0.27 μM for the SLAM–MV-H (Ed) interaction (14).

Table 1.

Surface plasmon resonance-binding analysis for MV-H-receptor interactions.

| Analyte | Ligand | Kd, M | kon,M−1s−1 | koff, s−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLAM | MV-H (WT) | 2.9 × 10−7 | 1.7 × 104 | 5.0 × 10−3 |

| MV-H (Ed) | 4.3 × 10−7 | 0.84 × 104 | 3.6 × 10−3 | |

| CD46 | MV-H (WT) | ND | ND | ND |

| MV-H (Ed) | 2.2 × 10−6 | 4.5 × 103 | 1.0 × 10−2 | |

| SLAM (complex sugar) | MV-H (WT) | 3.1 × 10−7 | 1.5 × 104 | 4.7 × 10−3 |

| MV-H (Ed) | 4.1 × 10−7 | 1.1 × 104 | 4.5 × 10−3 |

ND, not detected. Ligand indicates the protein immobilized on the research-grade CM5 chip, and analyte indicates the protein injected in solution. SLAM and SLAM (complex sugar) were expressed with HEK293S (GnTI-) and 293T cells, respectively.

Structure Determination and Overall Structure.

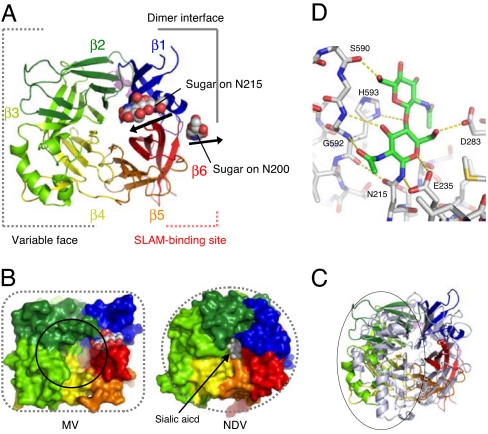

The selenomethionyl derivative of the soluble MV-H (Ed) head domain was then successfully crystallized. The initial experimental phases were determined by a single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) experiment, and the structure of the native molecule was refined at 2.6-Å resolution (detailed crystallographic statistics are summarized in SI Table 2). The MV-H head domain, encompassing residues 157–607, forms a disulfide-linked homodimer (described below) and exhibits a six-bladed β-propeller fold (β1–β6 sheets) (Fig. 1A). The structure is topologically similar to HN and NA/sialidases from viral, bacterial, or protozoan origin (17). However, the overall structure of MV-H is cubic-shaped, unlike the globular shape of other paramyxovirus HNs (Fig. 1B). Although amino acid alignment is possible based on secondary structures (SI Figs. 6 and 7), there are clear structural differences between MV-H and HN proteins of other paramyxoviruses; NDV (2) (rmsd = 3.3 Å for 300 Cα atoms), SV5 (3) (rmsd = 3.2 Å for 293 Cα atoms), and hPIV3 (4) (rmsd = 3.2 Å for 296 Cα atoms). The relative orientations of all β-sheets as well as the associated interstrand loops are quite different in MV-H compared with those in the HNs (Fig. 1C). The β2, β3, and β4 sheets show the most marked differences compared with the published structures (variable face in Fig. 1A and gray circle in Fig. 1C). As a result, the pocket on the top that accommodates the sialic acid receptor in HNs from other paramyxoviruses (Fig. 1B Right) is much more open and enlarged in the MV-H structure (solid circle in Fig. 1B Left).

Fig. 1.

Overview structure and N-glycan sites of MV-H protein. (A) Top view of MV-H shown in cartoon model. MV-H exhibits a six-bladed β-propeller fold. The sphere models indicate N-linked sugars on N200 and N215. B and C are shown at almost the same angle as A. (B) The surface presentation of MV-H (Left) and NDV-HN (Right). MV-H exhibits a cubic head, whereas HN proteins of other paramyxoviruses (NDV, hPIV3, and SV5), influenza virus NA (monomer), and human sialidase 2, all of which also have a six-bladed β-propeller fold, exhibit a globular head. The black circle indicates the pocket assumed to accommodate the invisible Man5 of the N215-linked sugar. The sphere model in NDV indicates a sialic acid molecule. (C) Superimposition of MV-H (rainbow) and NDV (gray). Variable face is indicated by the circle. (D) The interactions of N215-linked GlcNAc2 with MV-H residues. The dotted yellow lines indicate polar interactions. H593 forms stacking interactions with GlcNAc.

N-Linked Sugars.

The homogeneous oligomannose-type sugar molecule, GlcNAc2Man5, was expected to be attached on N-linked glycosylated sites of MV-H, and in the crystals, GlcNAc2 was observed on N215 (shown in the 2Fo−Fc map in SI Fig. 8A). The direction of the sugar is fixed by typical stacking interactions between the aromatic ring of H593 and a hydrophobic face of the GlcNAc residue together with polar interactions (Fig. 1D), suggesting that the sugar moiety of the invisible Man5 of the GlcNAc2Man5 may shield the top pocket [Figs. 1B (solid circle) and 2]. The enlarged pocket in MV-H seems suitable for accommodating these N-linked sugars, which are much larger than a single sialic acid residue. Furthermore, the pocket is fully solvent-exposed with no crystal contacts (SI Fig. 8 B and C).

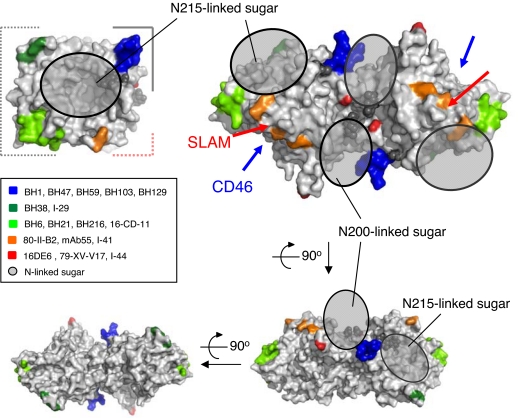

Fig. 2.

Epitope mapping of anti-MV-H mAbs on the MV-H structure with N-linked sugars. Anti-MV-H mAbs are described in the box (19–21). The top view of the MV-H monomer is shown at almost the same angle as Fig. 1A in Upper Left. The top, side, and bottom views of MV-H homodimer are shown in Upper Right, Lower Right, and Lower Left, respectively. The gray shaded circles indicate the N200- and N215-linked sugars. The N215-linked sugars appear to shield the pocket, blocking antibody binding. The N200-linked sugars are located very close to each other at the dimer interface. N168- and N187-linked sugars are not visible in the crystal. Red and blue arrows indicate the SLAM- and CD46-binding sites, respectively. mAb epitopes are limited to areas excluding the sugar-shielded areas and dimer and stalk interfaces.

We also determined the 3.0-Å resolution crystal structure of MV-H (Ed) produced in 293T cells with GnTI activity, which has complex-type N-linked sugars. Although the second GlcNAc of the N215-linked sugar was hardly visible, the density for the first GlcNAc residue of the N215-linked sugar was similar to that in the oligomannose-type MV-H, indicating that heterogeneous complex-type sugars probably shield the top pocket. Furthermore, the N200-linked sugars are located very close to each other at the dimer interface (Figs. 1A and 2), defining their orientation and possibly excluding spatial proximity of the N215-linked sugars. Previous studies (18) showed that two other potential N-linked sites (N168 and N187) are also sugar-modified, although those sugars were not visible in our crystal. Thus, wide areas of MV-H appear to be covered with N-linked sugars (SI Fig. 9). The complex-type sugars confer conformational and chemical variability on these sites, suppressing their potential antigenicity, and only unshielded side areas of MV-H are allowed to interact with antibodies. Epitopes of anti-MV-H antibodies (19–21) seem to be located in unshielded areas of MV-H (Fig. 2), supporting this notion.

Inability of MV-H to Bind Silalic Acid.

Several highly conserved amino acids responsible for sialic acid recognition by NA/sialidases are missing in MV-H (SI Table 3). The corresponding residues have different properties and show markedly different locations. To confirm that MV-H does not bind sialic acid, soaking and cocrystallization of MV-H (Ed) with sialyllactose were performed. The crystals obtained under both conditions did not show any electron density for sialyllactose (data not shown). Furthermore, both MV-H (Ed) and MV-H (WT) bind SLAM with oligomannose-type sugars (produced in HEK293S cells lacking the GnTI activity) and that with complex sugars (produced in 293T cells) at almost identical affinities (Table 1). The second sialic acid-binding site has been proposed at the dimer interface of the NDV HN protein, on the basis of its crystal structure complexed with silalic acid (22). However, the N-glycan molecule attached to N200 is closely located to this site in MV-H, possibly disturbing sialic acid binding. All these results exclude the presence of any binding site for sialic acid in MV-H.

Receptor-Binding Sites.

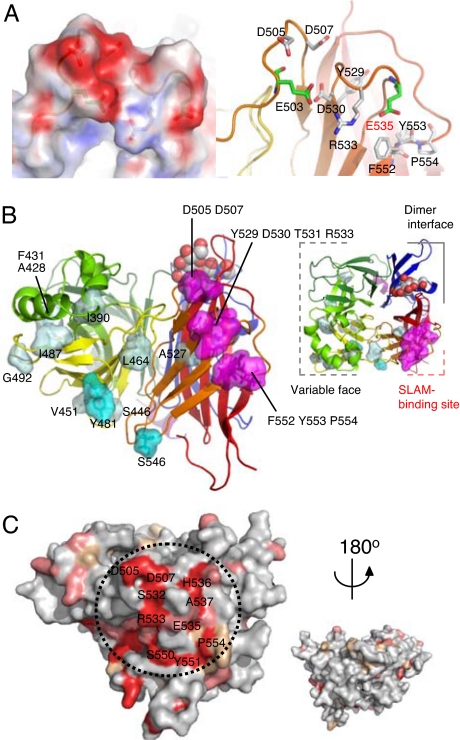

Previous studies on the receptor-dependent fusion-inducing activity of mutant MV-H proteins identified several amino acid residues important for interaction with SLAM: D505, D507, Y529, D530, T531, R533, F552, Y553 and P554 (23, 24) (Fig. 3A). These residues can be mapped to a small localized area on the interstrand loops of the β5 sheet, forming the putative SLAM-binding site (Fig. 3B, SI Fig. 7). The site includes several negatively charged residues such as E503, D505, D507, D530, and E535, forming an “acid patch” area (Fig. 3A). Our previous studies have determined that the putative MV-H-binding site on SLAM includes I60, H61, and V63 on the N-terminal variable domain (25, 26). From the structural model for SLAM built based on the crystal structure of the closely related molecule NTB-A (27) (data not shown), these residues plausibly exist in the area extending from one face of the β-sheet to membrane-distant loops. It includes several positively charged amino acids (K54, K58, H61, and K77), forming a “basic patch” area. The surface electrostatic distributions of the two proteins in these regions seem to be complementary and suitable for complex formation. These areas on H and SLAM are highly conserved in morbilliviruses (Fig. 3C) and host species (7), respectively, reconfirming that H–SLAM interaction plays an essential role in morbillivirus entry (6). Importantly, the SLAM-binding site includes the reported epitopes of neutralizing antibodies. Escape mutants from mAb 55 that neutralizes the SLAM-dependent MV infection had an R533G substitution (23), whereas those from I-41 that blocks MV-H binding to SLAM had an F552V substitution (14, 20) (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the key residues for interaction of MV-H (Ed) with CD46 (23, 24, 28) span the β3 to β5 sheets of the side face of the head domain and are located differently from the key residues at the SLAM-binding site (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The receptor-binding sites of MV-H protein. (A) Putative SLAM-binding site. Electrostatic representation (Left) and ribbon-and-stick model (Right; at the same angle as Left) of the putative SLAM-binding site located on the loops of the β5 sheet. Red and blue surfaces indicate negatively and positively charged areas, respectively. The residues predicted by mutagenesis studies (23, 24) to be involved in SLAM binding are indicated in white stick models. The acidic residues comprising the “acidic patch” of the putative SLAM-binding site are shown in green stick models. (B) Putative SLAM- and CD46-binding sites on the MV-H structure: side (Left) and top (Right) views. The amino acid residues predicted to be involved in receptor binding (23, 24, 28) are shown in magenta (SLAM) and cyan/light blue (CD46, strong/weak effect). The color scheme used is the same as Fig. 1. (C) The conserved residues in H proteins of seven morbilliviruses (measles, rinderpest, peste-des-petits ruminants, canine distemper, dolphin distemper, porpoise distemper, and phocine distemper) are indicated on the MV-H protein. Red, identical; salmon, strong similarity; wheat, weak similarity; gray, little similarity. The residues of the putative SLAM-binding site (dotted circle) are strongly conserved.

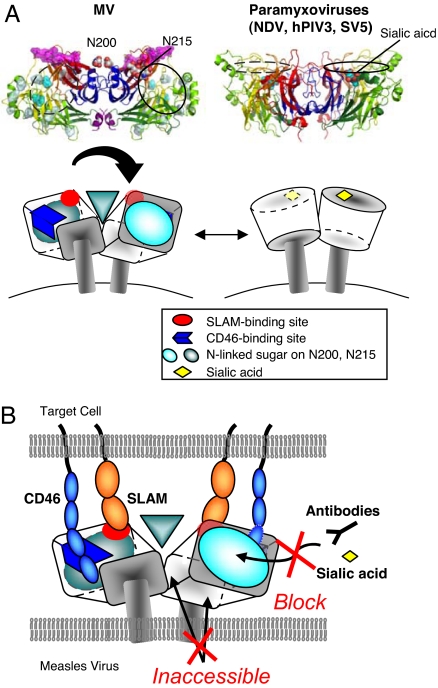

Tilted Orientation of Molecules Forming a Dimer.

Size-exclusion chromatography and nonreduced SDS/PAGE have suggested that MV-H forms a disulfide-linked dimer (SI Fig. 5), which was confirmed by our structural study (Fig. 4A). The disulfide bond between interchain cysteine residues (position 154) is clearly observed in the crystals of MV-H (complex-sugar type). The relative orientation of the two molecules forming the homodimer is highly tilted, in contrast to HN dimers of other paramyxoviruses (Fig. 4A). The dimer interface of MV-H has the area of 1,296 Å2, much smaller than those of other paramyxovirus HNs (≈1,800–2,000 Å2) but within normal range for protein–protein interactions (1,200–2,000 Å2) (29). This tilted orientation may result from the presence of the N200-linked sugars, which are located very close to the dimer interface and must be separated from each other to avoid spatial occlusion (Fig. 2). As a result, the putative SLAM-binding sites are oriented upward from the lipid bilayer, such that they are readily accessible for interaction with SLAM (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the sialic acid-binding sites of HNs from other paramyxoviruses tend to be directed upward because of less-tilted orientation of the homodimer.

Fig. 4.

Differential H/HN dimer formation and a schematic model of interactions between MV-H and its receptors. (A) Paramyxovirus (NDV, hPIV3, and SV5) HNs form dimers at a slight angle between monomers, whereas the MV-H dimer is tilted toward the horizontal plane to orient the receptor-binding sites upward. MV-H has sugar shield over the region corresponding to the active site in other paramyxoviruses. The cartoon model on the right is a representation of NDV. (B) A model of MV-H–receptor interaction. The putative SLAM- (red) and CD46- (blue) binding sites are oriented upward from the virus surface, easily accessible to the receptors. The N215-linked sugar shield (cyan circle) blocks any binding of the top pocket to antibodies, sialic acid, and other receptors. Additionally, the dimer and stalk interfaces, as well as the N-200-linked sugars, are not accessible.

Structural and Functional Insights into Antiviral Drug Design and Effective Vaccines.

In addition to currently available live vaccines, antiviral drugs are desirable for the treatment of MV patients. Our study clearly shows that the negatively charged SLAM-binding site, which seems to electrostatically complement the MV-H-binding site on SLAM (25, 26), serves as the main target for drugs/antibodies that block MV entry. Our model (SI Fig. 9) indicates that the N215-linked sugar is located close to the SLAM-binding site on the top of the molecule. However, no difference is found in the SLAM-binding affinities between oligomannose- and complex sugar-types of MV-H. This suggests that SLAM likely approaches the side surface of MV-H during the interaction, helping define the more detailed binding site.

The structure also suggests that extensive masking by sugars limits the availability of potential epitopes on the surface of MV-H for antibody recognition, although accessible regions do include the highly conserved SLAM-binding site, which is crucial for MV entry (the strong conservation of the SLAM-binding site is observed not only among MV strains but also among different species of morbilliviruses). This explains the serological monotype characteristic of MV, ensuring the production of effective neutralizing antibodies during vaccination, by contrast with sugar shields of the HIV gp120 that facilitate immune escape (30). It appears that escape from neutralizing antibodies directed against the SLAM-binding site (by either amino acid changes or sugar shields) compromises the ability of MV-H to bind SLAM. Our results support the idea that sugar shields could be exploited for the development of effective vaccines, such that the immune responses are almost exclusively directed against relevant and unchangeable epitopes (31).

Materials and Methods

Construction of Expression Plasmids.

The DNA fragment encoding the ectodomain (amino acid residues D149 to R617) of MV-H (Ed or WT) was amplified by PCR by using as template the p(+)MV2A (a gift from M. A. Billeter, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland) or p(+)MV323 encoding the antigenomic full-length cDNA of the Edmonston B (32) or IC-B strain of MV (33), respectively. The amplified fragment was cloned into a derivative of the expression vector pCA7 (34). This derivative vector contains the signal sequence and His6 tag sequence (up- and downstream of the protein-coding sequence, respectively), both of which are derived from the pHLsec vector (35). For some constructs, the biotin-tag sequence was also included upstream of the protein-coding sequence. The fragment encoding the authentic signal sequence and ectodomain of SLAM or CD46 was also amplified and similarly cloned into pCA7 with the His6 tag sequence. The SLAM ectodomain was constructed as a chimera comprising the human V (T25 to Y138) and mouse C2 domains (E140 to E239). The CD46 ectodomain contained short consensus repeats 1–4 (M1 to K285).

Protein Expression, Purification, and Characterization.

The expression plasmid encoding the soluble recombinant molecule (MV-H, SLAM, or CD46) was transiently transfected by using polyethyleneimine, together with the plasmid encoding the SV40 large T antigen, into 90% confluent HEK293S cells lacking N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I (GnTI) activity or 293T cells (15, 35). The cells were cultured in DMEM (MP Biomedicals), supplemented with 10% FCS (Invitrogen), l-glutamine, and nonessential amino acids (GIBCO). The concentration of FCS was lowered to 2% immediately after transfection. A selenomethionyl (SeMet) derivative of MV-H was expressed in cells cultured in l-methionine-free DMEM supplemented with l-selenomethionine. The His6-tagged protein was purified 4 days after transfection from the culture media by using the Ni2+-NTA affinity column and superdex 200 GL 10/300 gel filtration chromatography (Amersham Biosciences). All buffers were adjusted to pH 8.0. Molecular weights of the proteins were assessed by SDS/PAGE (under reducing and nonreducing conditions) and gel filtration chromatography. The recombinant MV-H proteins separated by SDS/PAGE were detected by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue or by immunoblotting by using penta-His antibody (Qiagen), followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. The proteins were treated with ECLplus (Amersham Biosciences) and visualized with the Versa Doc imaging system (Bio-Rad).

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

Crystals of native MV-H (Ed) expressed in HEK293S(GnTI-) or 293T cells were grown by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion at 20°C. The drops contained 1 μl each of protein (9.7 mg/ml in 20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0; 100 mM NaCl) and mother liquor (100 mM sodium acetate trihydrate, pH 4.6; 2.0 M sodium formate; 10% ethylene glycol). Crystals of SeMet derivative (oligomannose-type) were grown at 30°C with constant shaking. The drops contained 1 μl each of protein (8.0 mg/ml in 20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0; 100 mM NaCl) and mother liquor (200 mM NaCl; 100 mM Na/K phosphate, pH 6.2; 7% polyethylene glycol 8000). For data collection, the crystals were cryocooled (by nitrogen gas stream, 100 K) in the original mother liquor containing 30% (vol/vol) ethylene glycol or glycerol, and diffraction data sets were collected on BL-41XU at SPring8 (Harima) or on BL6A at Photon Factory (Tsukuba). The diffraction data were processed and scaled with the HKL2000 package (36).

The structure was solved by SAD by using a SeMet crystal. Selenium site search and phasing were done by using SOLVE (37), followed by density modification and initial model building was performed with RESOLVE (38). Model refinement calculations were carried out with CNS (39) and model building was done by using COOT (40). The final model of the oligomannose-type MV-H protein was refined to an Rfree factor of 24.8% and an R factor of 22.5%. The structure of the complex-sugar-type MV-H protein was solved by molecular replacement. Detailed crystallographic statistics are shown in SI Table 2. Ramachandran plot was calculated by PROCHECK (41). Figs. 1–4 and SI Figs. 8 and 9. were generated by using PyMOL (http://pymol.sourceforge.net).

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR).

SPR experiments were performed by using BIAcore2000 (BIAcore). The biotinylated MV-H proteins were immobilized on research-grade CM5 chips (BIAcore), onto which streptavidin had been covalently coupled. All samples, after buffer exchange into HBS (10 mM Hepes; 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) or HBS-P (10 mM Hepes; 150 mM NaCl; 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4), were injected over the immobilized MV-H proteins. The binding response at each concentration was calculated by subtracting the equilibrium response measured in the control flow cell from the response in the each sample flow cell. Kinetic constants were derived by using the curve-fitting facility of Biaevaluation 3.0 (BIAcore) to fit rate equations derived from the simple 1:1 Langmuir binding model (A + B ↔ AB). Affinity constants (Kd) were derived by Scatchard analysis or nonlinear curve fitting of the standard Langmuir binding isotherm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Wakatsuki, N. Igarashi, N. Matsugaki, M. Kawamoto, H. Sakai, N. Shimizu, and K. Hasegawa for assistance in data collection at the Photon Factory and SPring-8. We also thank B. Byrne, M. Matsushima, E. Y. Jones, A. R. Aricescu, and S. Kollnberger for critical reading. This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, and the Japan Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institute (BRAIN).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 2ZB6 (oligomannose type of MV-H) and 2ZB5 (complex sugar type of MV-H)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0707830104/DC1.

References

- 1.Lamb RA, Parks GD. In: Fields Virology. 5th Ed. Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1449–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crennell S, Takimoto T, Portner A, Taylor G. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1068–1074. doi: 10.1038/81002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan P, Thompson TB, Wurzburg BA, Paterson RG, Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS. Structure (London) 2005;13:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence MC, Borg NA, Streltsov VA, Pilling PA, Epa VC, Varghese JN, McKimm-Breschkin JL, Colman PM. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:1343–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tatsuo H, Ono N, Tanaka K, Yanagi Y. Nature. 2000;406:893–897. doi: 10.1038/35022579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yanagi Y, Takeda M, Ohno S. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2767–2779. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatsuo H, Ono N, Yanagi Y. J Virol. 2001;75:5842–5850. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5842-5850.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffin DE. In: Fields Virology. 5th Ed. Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1551–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE. Lancet. 2005;365:1147–1152. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Swart RL, Yuksel S, Osterhaus AD. J Virol. 2005;79:11547–11551. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11547-11551.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorig RE, Marcil A, Chopra A, Richardson CD. Cell. 1993;75:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80071-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naniche D, Varior-Krishnan G, Cervoni F, Wild TF, Rossi B, Rabourdin-Combe C, Gerlier D. J Virol. 1993;67:6025–6032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6025-6032.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlenhofer C, Duprex WP, Rima BK, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies J. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:1431–1436. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-6-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santiago C, Bjorling E, Stehle T, Casasnovas JM. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32294–32301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves PJ, Callewaert N, Contreras R, Khorana HG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobune F, Takahashi H, Terao K, Ohkawa T, Ami Y, Suzaki Y, Nagata N, Sakata H, Yamanouchi K, Kai C. Lab Anim Sci. 1996;46:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langedijk JP, Daus FJ, van Oirschot JT. J Virol. 1997;71:6155–6167. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6155-6167.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu A, Cattaneo R, Schwartz S, Norrby E. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1043–1052. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-5-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fournier P, Brons NH, Berbers GA, Wiesmuller KH, Fleckenstein BT, Schneider F, Jung G, Muller CP. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1295–1302. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-6-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu A, Sheshberadaran H, Norrby E, Kovamees J. Virology. 1993;192:351–354. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ertl OT, Wenz DC, Bouche FB, Berbers GA, Muller CP. Arch Virol. 2003;148:2195–2206. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaitsev V, von Itzstein M, Groves D, Kiefel M, Takimoto T, Portner A, Taylor G. J Virol. 2004;78:3733–3741. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3733-3741.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masse N, Ainouze M, Neel B, Wild TF, Buckland R, Langedijk JP. J Virol. 2004;78:9051–9063. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9051-9063.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vongpunsawad S, Oezgun N, Braun W, Cattaneo R. J Virol. 2004;78:302–313. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.1.302-313.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohno S, Seki F, Ono N, Yanagi Y. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2381–2388. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono N, Tatsuo H, Tanaka K, Minagawa H, Yanagi Y. J Virol. 2001;75:1594–1600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1594-1600.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao E, Ramagopal UA, Fedorov A, Fedorov E, Yan Q, Lary JW, Cole JL, Nathenson SG, Almo SC. Immunity. 2006;25:559–570. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tahara M, Takeda M, Seki F, Hashiguchi T, Yanagi Y. J Virol. 2007;81:2564–2572. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02449-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo Conte L, Chothia C, Janin J. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:2177–2198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scanlan CN, Offer J, Zitzmann N, Dwek RA. Nature. 2007;446:1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature05818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pantophlet R, Wilson IA, Burton DR. J Virol. 2003;77:5889–5901. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5889-5901.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radecke F, Spielhofer P, Schneider H, Kaelin K, Huber M, Dotsch C, Christiansen G, Billeter MA. EMBO J. 1995;14:5773–5784. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeda M, Takeuchi K, Miyajima N, Kobune F, Ami Y, Nagata N, Suzaki Y, Nagai Y, Tashiro M. J Virol. 2000;74:6643–6647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6643-6647.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeda M, Ohno S, Seki F, Nakatsu Y, Tahara M, Yanagi Y. J Virol. 2005;79:14346–14354. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14346-14354.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aricescu AR, Assenberg R, Bill RM, Busso D, Chang VT, Davis SJ, Dubrovsky A, Gustafsson L, Hedfalk K, Heinemann U, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 2006;62:1114–1124. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906029805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terwilliger TC. Acta Crystallogr D. 2000;56:965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, Delano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laskowsky R, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.