Abstract

Ovarian cancer is the fifth most common cause of cancer-related death in women. Current interventional approaches, including debulking surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation have proven minimally effective in preventing the recurrence and/or mortality associated with this malignancy. Subtraction hybridization applied to terminally differentiating human melanoma cells identified melanoma differentiation associated gene-7/interleukin-24 (mda-7/IL-24), whose unique properties include the ability to selectively induce growth suppression, apoptosis, and radiosensitization in diverse cancer cells, without causing any harmful effects in normal cells. Previously, it has been shown that adenovirus-mediated mda-7/IL-24 therapy (Ad.mda-7) induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells, however, the apoptosis induction was relatively low. We now document that apoptosis can be enhanced by treating ovarian cancer cells with ionizing radiation (IR) in combination with Ad.mda-7. Additionally, we demonstrate that mda-7/IL-24 gene delivery, under the control of a minimal promoter region of progression elevated gene-3 (PEG-3), which functions selectively in diverse cancer cells with minimal activity in normal cells, displays a selective radiosensitization effect in ovarian cancer cells. The present studies support the use of IR in combination with mda-7/IL-24 as a means of augmenting the therapeutic benefit of this gene in ovarian cancer, particularly in the context of tumors displaying resistance to radiation therapy.

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer deaths among US women and has the highest mortality rate of all gynecologic cancers (Jemal et al., 2004). The majority of patients initially present with stage III or IV disease and display poor prognosis. Unfortunately, despite advances in initial debulking surgery and chemotherapy, many patients will have recurrence in the abdomen or pelvis that frequently is not responsive to further chemotherapy and carries a negative prognosis (Christian and Thomas, 2001). Therefore, treatments that improve initial disease control in the abdomen and pelvis have the potential to extend the progression-free interval and possibly also survival. Additionally, mortality from epithelial ovarian carcinoma has remained high for the past few decades. These facts underscore the need for development of new effective therapies.

Since human ovarian carcinoma is considered to be the result of acquired genetic alterations, gene therapy offers a novel approach for treating this neoplastic disease (Gomez-Navarro et al., 1998; Wolf and Jenkins, 2002). However, to realize the promise of gene therapy, identifying a gene therapeutic that does not harm normal cells and can kill only tumor cells would represent an ideal weapon to combat this prevalent female disease and cancer in general. A number of diverse gene therapy approaches for ovarian cancer have been endeavored using adenoviral vectors (Ad), in both animal models (Barnes et al., 1997; Robertson et al., 1998; Alvarez et al., 2000; Casado et al., 2001) and human clinical trials (Alvarez and Curiel, 1997; Collinet et al., 2000). Some of these approaches have included Ad-mediated delivery of p53, a tumor suppressor gene, or Bax, a pro-apoptotic gene, or toxin encoding genes, such as HSV-TK and cytosine deaminase. Although many therapeutic approaches have been developed, most of them are limited in their application due to their low therapeutic potential and high toxicity to normal tissues. Of note, a recent Phase II/III trial of p53 gene therapy failed due to low therapeutic benefit (Zeimet and Marth, 2003). Therefore, identification and development of novel genes with high therapeutic potential and minimal toxicity to normal tissues (high therapeutic index) are warranted. In principle, such genes would provide significant benefit in treating this prevalent cancer.

Melanoma differentiation associated gene-7 (mda-7) is a secreted cytokine belonging to the interleukin (IL)-10 family that has been designated IL-24. Multiple independent studies have confirmed that delivery of mda-7/IL-24 by a replication-incompetent adenovirus, Ad.mda-7, or as a GST-MDA-7 fusion protein selectively kills diverse cancer cells, without harming normal cells, and radiosensitizes various cancer cells, including non-small cell lung carcinoma, renal carcinoma, and malignant glioma (Kawabe et al., 2002; Su et al., 2003, 2005a; Yacoub et al., 2003a,b,c; Sauane et al., 2004; Lebedeva et al., 2005b). In addition, mda-7/IL-24 possesses potent anti-angiogenic, immunostimulatory, and bystander activities (Fisher, 2005). The sum of these attributes makes mda-7/IL-24 a significant candidate for cancer gene therapy (Fisher, 2005). Indeed, Ad.mda-7 has been successfully used for Phase I/II clinical trials for solid tumors and has shown promising results in tumor inhibition (Fisher et al., 2003; Cunningham et al., 2005; Fisher, 2005; Lebedeva et al., 2005a; Tong et al., 2005). Although the ultimate end-result of Ad.mda-7 infection is induction of apoptosis, it employs different signal transduction pathways, such as activation of p38 MAPK, PKR, TRAIL, in different tumor cell types to achieve this objective (Pataer et al., 2002; Saeki et al., 2002; Sarkar et al., 2002).

The therapeutic potential of mda-7/IL-24 gene therapy in the context of epithelial ovarian carcinoma has not been investigated extensively. We have previously demonstrated that Ad.mda-7 gene therapy induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells but not in normal mesothelial cells (Leath et al., 2004). However, the apoptosis induction efficiency was low. The purpose of the present study was: (1) to develop combinatorial approaches to improve apoptosis induction in ovarian carcinoma cells; and (2) to evaluate ovarian cancer cell targeted gene therapy by tumor-specific transgene expression using the novel promoter derived from progression elevated gene-3 (PEG-3) (Su et al., 1997, 1999). We now document that this resistance to Ad.mda-7 is reversible in ovarian cancer cells by employing ionizing radiation (IR). Additionally, we demonstrate that, mda-7/IL-24 gene delivery under the control of a minimal promoter region of PEG-3 (Su et al., 1997, 1999, 2000, 2001b) which functions selectively in diverse cancer cells with minimal activity in normal cells (Su et al., 2000, 2001b, 2005b; Sarkar et al., 2005a,b), displays a selective radiosensitization effect in ovarian cancer cells. The present study confirms that the therapeutic potential of mda-7/IL-24 can be augmented by IR with the added advantage of being able to sensitize both radiation- and mda-7/IL-24-resistant cells to programmed cell death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, culture conditions, and radiation protocol

The SKOV3 (p53 null), human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells, and human mesothelial cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell lines HEY (p53 wild-type), SKOV3.ip1 (p53 null), and OV-4 (p53 mutant) were kindly provided by Dr. Judy Wolf and Dr. Janet Price (M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX) and Dr. Timothy J. Eberlein (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), respectively. SKOV3, SKOV3.ip1, and OV-4 cells were cultured and maintained in complete medium composed of DMEM:F12 (Cellgro; Media-tech, Washington, DC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 5 mM glutamine (Cellgro; Mediatech), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Cellgro; Mediatech). HEY cells were cultured and maintained in complete medium composed of RPMI (Cellgro; Mediatech) supplemented with 10% FBS, 5 mM glutamine, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Human mesothelial cells were cultured and maintained in complete medium composed of a 1:1 mixture of Media 199 (Cellgro; Mediatech) and MCDB 105 Media (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 20% FBS, 5 mM glutamine, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 10 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). All cells were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Infections of all cells utilized respective infection medium which contained 2% FBS. Cells were irradiated with 2 Gy of IR using a 137Cs γ-irradiation source. SB203580 was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co.

Construction of adenovirus (Ad) and infection protocol

The recombinant replication-incompetent Ads, Ad.CMV-GFP, Ad.PEG-GFP, Ad.CMV-Luc, Ad.PEG-Luc, Ad.CMV-mda-7 (CMV promoter driving mda-7/IL-24 expression), and Ad.PEG-mda-7 (PEG-Prom driving mda-7/IL-24 expression) were created in two steps as described previously and plaque purified by standard procedures (Su et al., 2005a). As a control, a replication-incompetent Ad.vec without any transgene was used. Cells were infected with a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 100 plaque-forming units (pfu) per cell with different Ads.

Fluorescence microscopy for GFP evaluation

Cells (2 × 105/well) were plated in triplicate in 6-well plates. The next day, cells were infected with Ad.CMV-GFP and Ad.PEG-GFP at a moi of 100 pfu/cell for 2 h in 2% infection medium. Subsequently, 2 ml of complete media was added and incubated at 37°C. After 48 h, the cells were analyzed for green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression by observing under a fluorescent microscope.

Luciferase assay

Cells were plated in 12-well plates in 2 ml of complete medium. The next day, supernatant was aspirated and the cells were infected with Ad.CMV.Luc and Ad.PEG.Luc at a moi of 100 pfu/cell in 200 μl of 2% medium. Following incubation for 2 h, complete medium was added. Luciferase assays were performed using commercial kits (Promega, Madison, WI) 48 h after infection. Protein concentration was determined using BCA Protein Assay Kit from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL) as per manufacturer’s recommendations. The luciferase activity was then determined by calculating relative luciferase activity (RLU)/mg of protein as previously described (Leath et al., 2004).

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates (1.5 × 103 cells per well) and treated the next day as described in the figure legends. At the indicated time points, the medium was removed, and fresh medium containing 0.5 mg/ml MTT was added to each well. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h and then an equal volume of solubilization solution (0.01 N HCl in 10% SDS) was added to each well and mixed thoroughly. The optical density from the plates was read on a Dynatech Laboratories MRX microplate reader at 540 nm.

Apoptosis and necrosis (Annexin-V binding assay)

Cells were trypsinized and washed with complete media and then twice with PBS. The aliquots of the cells (2 × 105) were resuspended in 1× binding buffer (0.5 ml) and stained with APC (allophycocyanin)-labeled Annexin-V (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DAPI was added to the samples after staining with Annexin-V to exclude late apoptotic and necrotic cells. The flow cytometry was performed immediately after staining.

Clonogenic survival assay

Cells were treated as described in the Figure legends. The following day, after trypsinization and counting, cells were replated in 60-mm dishes (500 cells per dish) in triplicates. After 2 or 3 weeks, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 5% (w/w) solution of Giemsa stain in water. Colonies >50 cells were scored and counted.

Western blot assay

Cell lines were grown on 10-cm plates and protein extracts were prepared with RIPA buffer containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors. A measure of 50 μg of protein was applied to 12% SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose/PVDF membranes. The membranes were probed with polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies to mda-7/IL-24, anti-PEA-3, anti-c-JUN, phospho-P38 MAPK, total P38 MAPK, and EF-1α

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the Qiagen RNeasy mini kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol and was used for Northern blotting as previously described (Su et al., 2001b). Briefly, 10 μg of RNA for each sample was denatured, electrophoresed in 1.2% agarose gels with 3% formaldehyde, and transferred onto nylon membranes. The blots were probed with an α-32P[dCTP]-labeled, full-length human mda-7/IL-24 cDNA probe. Following hybridization, the filters were washed and exposed for autoradiography.

Statistical analysis

All of the experiments were performed at least three times. Results are expressed as mean ±SE. Statistical comparisons were made using an unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

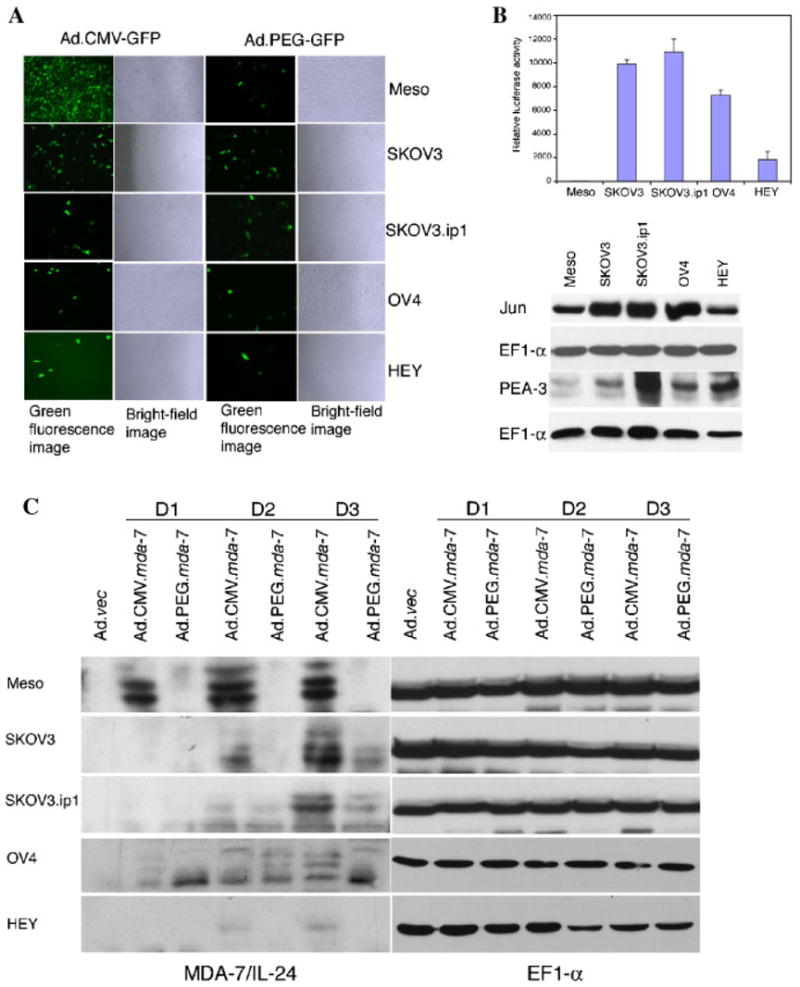

Ovarian cancer cell lines exhibits low levels of adenoviral-mediated gene expression

Previous studies document that ovarian cancer cell lines have low coxsackie adenovirus receptor (CAR) expression (Leath et al., 2004), which is a primary receptor for adenovirus infection. Two replication-incompetent adenoviruses expressing GFP, one under the control of the CMV promoter (Ad.CMV-GFP) and the other under the control of the PEG-Prom (Ad.PEG-GFP) were constructed (Su et al., 2005b). To determine the status of adenoviral infectivity we examined GFP expression by fluorescence microscopy following infection with Ad.CMV-GFP and Ad.PEG-GFP at a moi of 100 pfu/cell 2 days post-infection. Infection with Ad.CMV-GFP resulted in high GFP expression in normal human mesothelial cells and in SKOV3 cells and low level GFP expression in SKOV3.ip1, OV-4, and HEY cells. With Ad.PEG-GFP infection, none to barely detectable GFP could be observed in normal human mesothelial cells and in ovarian cancer cell lines the GFP expression level was comparable to that observed after Ad.CMV-GFP infection (Fig. 1A). These findings indicate that ovarian cancer cells have variable levels of CAR that preclude efficient adenoviral transduction and subsequent transgene expression.

Fig. 1.

GFP, Luc, and MDA-7/IL-24 expression following infection of normal mesothelial and ovarian carcinoma cells with various adenoviruses and de novo levels of Jun, PEA-3, and EF-1α protein in mesothelial and ovarian carcinoma cells. A: Variable infectivity of ovarian cancer cells by adenovirus as determined by GFP expression. The indicated cells were infected with either Ad.CMV-GFP or Ad.PEG-GFP at a moi of 100 pfu/cell, and GFP expression was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy at 2d post-infection. B: Upper part: PEG-promoter drives high luciferase expression in ovarian cancer cells, but not in normal human mesothelial cells. The indicated cells were infected with Ad.PEG-luc at a moi of 100 pfu/cell, and luciferase activity was measured at 48 h post-infection and expressed as RLU/mg protein. The data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Lower part: The expressions of JUN, PEA-3, and EF-1α protein were analyzed by Western blot analysis in ovarian cancer cells and normal human mesothelial cells. C: Infection of ovarian cancer cells and normal human mesothelial cells with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 results in variable amounts of intracellular MDA-7/IL-24 protein. Cells were infected with the indicated viruses at a moi of 100 pfu/cell and total cell lysates were prepared at d 1, d 2, and d 3 post-infection. The cell lysate used for Ad.vec was the lysate prepared at d 3 post-infection. The expression of MDA-7/IL-24 and EF-1α proteins were evaluated by Western blot analysis.

PEG-Prom functions selectively in cancer cells

To quantify PEG-Prom activity in ovarian cancer and normal human mesothelial cells a luciferase-based reporter gene assay was employed. We constructed Ad.PEG-Luc in which the expression of the luciferase reportergenewasunderthecontrolofthePEG-Prom in a replication-incompetent adenoviral vector and infected normal mesothelial cells or the different ovarian cancer cell lines. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h after infection and expressed as RLU per mg protein. Normal human mesothelial cells demonstrated no activity supporting the limited GFP expression detected immunohistochemically following infection with Ad.PEG-GFP (Fig. 1B, upper part). When compared to normal human mesothelial cells, all of the ovarian cancer cells showed significantly increased PEG-Prom activity, although the activity in HEY cells was much lower than that in the other three ovarian cancer cell lines. The findings from GFP expression and luciferase reporter studies further confirm that the PEG-Prom functions selectively in cancer cells and is a useful tool to ensure cancer cell-targeted transgene expression.

PEA-3 and AP-1 controls PEG-Prom activity in ovarian cancer cells

PEA-3 and AP-1 are two transcription factors conferring cancer cell-selective function of the PEG-Prom in multiple cancer cell types, such as prostate, breast, central nervous system (malignant glioma), and pancreatic cancers (Sarkar et al., 2005a,b; Su et al., 2005b). To determine the involvement of these two factors in regulating PEG-Prom activity in ovarian cancer cells, the relative abundance of PEA-3 and Jun, a component of AP-1, proteins in ovarian cancer, and normal human mesothelial cells was analyzed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B, lower part). The expression of PEA-3 and Jun was significantly higher in all of the ovarian cancer cells when compared to that in normal human mesothelial cells, except for HEY cells, which showed comparable level of Jun expression to normal human mesothelial cells. These findings confirm that like other cell types previously examined, PEA-3 and AP-1 also control PEG-Prom activity in ovarian cancer cells.

Infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 and Ad.PEG-mda-7 generates MDA-7/IL-24 protein

To extend our studies further we used two additional replication-incompetent adenoviruses expressing mda-7/IL-24, one under the control of CMV promoter (Ad.CMV-mda-7) and the other under the control of PEG-Prom (Ad.PEG-mda-7). The authenticity of these Ad were confirmed by Western blot analysis for MDA-7/IL-24 following infection of ovarian cancer cells and normal human mesothelial cells at a moi of 100 pfu/cell. Normal human mesothelial cells showed abundant MDA-7/IL-24 protein following Ad.CMV-mda-7 infection, but no MDA-7/IL-24 protein after Ad.PEG-mda-7 infection (Fig. 1C). In ovarian cancer cells, infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 resulted in more intracellular MDA-7/IL-24 protein than infection with Ad.PEG-mda-7. The relative levels of MDA-7/IL-24 and GFP proteins correlated well in different ovarian cancer cell lines, with SKOV3 cells showing the highest level of trans-genes and HEY cells showing the lowest. These findings further confirm that although the PEG-Prom is functionally less active than CMV promoter, it ensures cancer cell-specific expression of MDA-7/IL-24.

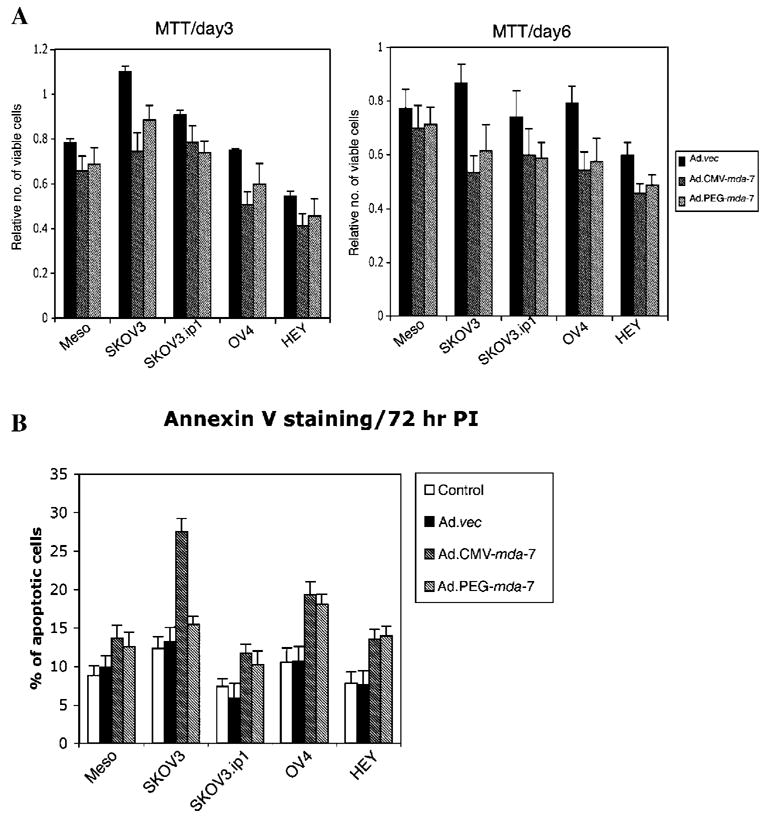

Ad.CMV-mda-7 and Ad.PEG-mda-7 induce apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells

Experiments were next performed to determine whether infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 could induce growth suppression and apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. Cell viability was assessed by standard MTT assay 3 and 6 days after Ad infection. As expected neither Ad.CMV-mda-7 nor Ad.PEG-mda-7 affected the viability of normal human mesothelial cells (Fig. 2A). Although both Ad.CMV-mda-7 and Ad.PEG-mda-7 decreased cell viability in all the ovarian cancer cells, the effect, although significant, was marginal, except for SKOV3 cells, which displayed a more pronounced effect (Fig. 2A). Analysis of apoptosis by Annexin-V staining produced similar corroborating results as the MTT assays (Fig. 2B). No significant increase in apoptotic cells was observed in normal human mesothelial cells upon infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG.mda-7. Both of these Ads induced marginal but significant increases in apoptotic cells in the ovarian cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

Effect of infection of normal mesothelial and ovarian carcinoma cells with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 on cell viability and apoptosis induction. A: Infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 results in a decrease in cell viability in ovarian cancer cells. Cells were infected with the indicated viruses and cell viability was assessed by MTT assay at 3 d and 6 d post-infection. A significant loss in cell viability was evident in the SKOV3 and OV-4 cell lines. Results are the average from at least three experiments ±SD. B: Infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 variably induces apoptosis in different ovarian cancer cells. The indicated cell type was infected with the designated viruses for 72 h, and Annexin-V binding assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Results are the average from at least three experiments ±SD.

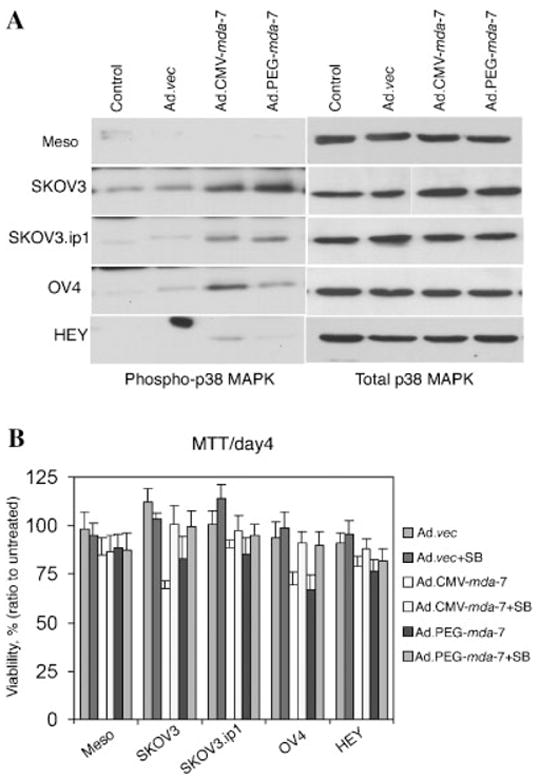

Ad.CMV-mda-7 and Ad.PEG-mda-7 induce apoptosis by activating p38 MAPK

Experiments were performed to determine whether Ad.CMV-mda-7 and Ad.PEG.mda-7 infection in ovarian cancer cells activates the p38 MAPK pathway that has been shown to mediate apoptosis induction by Ad.mda-7. In normal human mesothelial cells, infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG.mda-7 did not increase phospho-p38 MAPK levels 2 days post-infection (Fig. 3A). In SKOV3, SKOV3.ip1, and OV-4 cells, which showed significant susceptibility to growth inhibition, Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG.mda-7 infection resulted in a significant increase in phospho-p38 MAPK levels. However, in HEY cells, which are relatively resistant to growth inhibition, the increase in phospho-p38 MAPK was marginal. Treatment with the specific p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 protected the cells from growth inhibition following infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG.mda-7 (Fig. 3B). These findings indicate that activation of p38 MAPK also plays an important role in mediating growth inhibition by mda-7/IL-24 in ovarian cancer cells.

Fig. 3.

Infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 induces p38 MAPK phosphorylation and treatment with SB203580 protects ovarian cancer cells from mda-7-mediated apoptosis. A: Cells were infected with the indicated viruses as described in Figure 1C. Total cellular extracts were prepared at 48 h post-infection and the levels of phospho-p38 and total p38 MAPK were analyzed by Western blot analysis. B: Cells were infected with the indicated viruses and treated with 1 μM SB203580. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay at 4 d post-infection. Results are the average from at least three experiments ±SD.

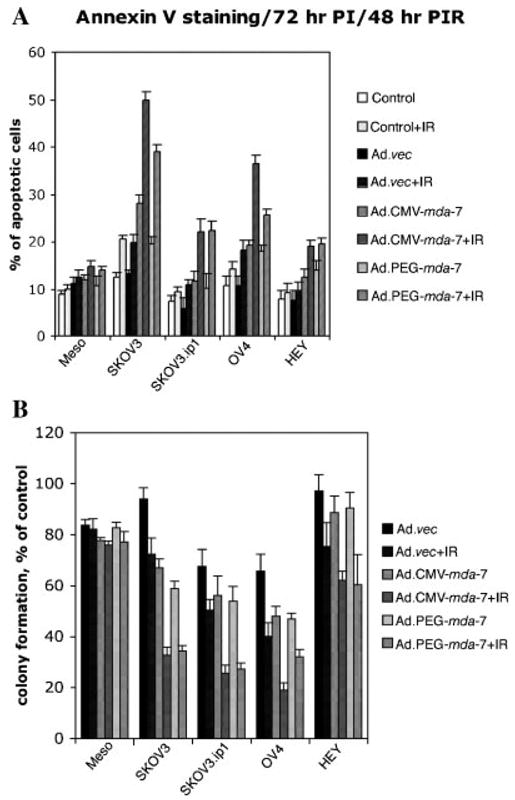

Combination of γ-irradiation and Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG.mda-7 infection overcomes resistance of ovarian cancer cells to both ionizing radiation and mda-7/IL-24

Since Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG.mda-7 alone showed relatively low apoptosis induction in ovarian cancer cells, we hypothesized that a combinatorial approach with other anti-cancer strategies might be useful in augmenting growth suppression and apoptosis. Previous studies confirm that mda-7/IL-24 is a potent radiosensitizer in multiple cancer subtypes, including non-small cell lung carcinoma, breast carcinoma, prostate carcinoma, and glioblastoma multiforme (Kawabe et al., 2002; Su et al., 2003; Yacoub et al., 2003a,b,c). These studies prompted us to test the effect of γ-radiation (IR) in combination with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG.mda-7 in the context of ovarian cancer. In all four ovarian cancer cell lines, Ad.CMV-mda-7, Ad.PEG-mda-7, or 2 Gy of IR alone produced a marginal enhancement in the percentage of Annexin-V positive cells. However, a combination of 2 Gy of IR with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 significantly enhanced Annexin-V staining in all four ovarian cancer cell lines (Fig. 4A). Similarly, in colony formation assays, infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 alone significantly reduced colony formation only in the SKOV3 cell line; however, a combination treatment with 2 Gy IR further reduced the number of colonies not only in SKOV3 cell but also in the other three ovarian cancer cell lines (Fig. 4B). No significant induction of apoptosis or reduction in colony formation was apparent with this combinatorial treatment approach in normal human mesothelial cells. These results suggest that the combination of mda-7/IL-24 and IR might be a useful and efficacious approach for treating ovarian cancer patients.

Fig. 4.

Combination of Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 plus IR induces enhanced killing and apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. A: Effect of single and combination treatment with Ad. CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 plus IR on apoptosis induction in ovarian cancer cells. The indicated cell type was either uninfected or infected with Ad.vec, Ad.CMV-mda-7, or Ad.PEG-mda-7 and the next day was exposed to 2 Gy of IR. An Annexin-V binding assay was performed at 48 h post-irradiation as described in Materials and Methods. Results are the average from at least three experiments ±SD. B: Effect of combination treatment with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 plus IR on growth of ovarian cancer cells. Cells were either uninfected or infected and untreated or treated with IR as described in Figure 4A and colony forming assays were performed as described in the Materials and Methods section. Data are presented as a percentage of colony formation to that of the uninfected and untreated group. Results shown are averages ±SD of triplicate samples.

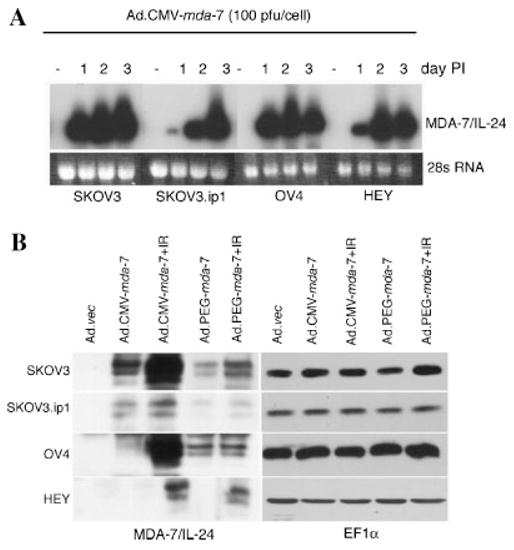

MDA-7/IL-24 protein production in ovarian cancer cells directly correlates with a decrease in cell survival by combination treatment with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7 and IR

We next endeavored to define the possible mechanism of augmentation of mda-7/IL-24-induced cell killing by IR. Infection with Ad.CMV-mda-7 generated high levels of mda-7/IL-24 mRNA as early as 1 day after infection in SKOV3 and OV-4 cells (Fig. 5A). Although in SKOV3.ip1 and HEY cells mda-7/IL-24 mRNA level was not high 1 day after infection, which can be explained by low infectivity, it accumulated gradually and by 3 days post-infection all four ovarian cancer cells had high and comparable levels of mda-7/IL-24 mRNA. This finding contrasts with the observation that in HEY cells very little MDA-7/IL-24 protein levels were observed even at 2 days post-infection (Fig. 1C and 5B). An inherent block in mda-7/IL-24 mRNA translation into protein has been observed in pancreatic cancer cells that can be overcome by multiple combinatorial approaches such as inhibition of K-ras or induction of reactive oxygen species (Su et al., 2001a; Lebedeva et al., 2005b, 2006). When ovarian cancer cells were treated with γ-radiation elevated levels of MDA-7/IL-24 protein were detected upon infection with both Ad.CMV-mda-7 and Ad.PEG.mda-7 in all four ovarian cancer cells. These findings indicate that γ-radiation treatment helps overcome the translational block delimiting MDA-7/IL-24 protein production, thus facilitating augmentation of apoptosis induction.

Fig. 5.

Combination treatment with mda-7/IL-24 and IR reverses the translational block in ovarian cancer cells. A: Infection of Ad.CMV-mda-7 induces an abundant amount of MDA-7/IL-24 RNA. Total RNA was isolated at d 1, d 2, and d 3 after infection as described in Materials and Methods, and analyzed by Northern blotting. The blots were probed with a α-32P[dCTP]-labeled, full-length human mda-7/IL-24 cDNA probe and exposed for autoradiography. B: Combination treatment of IR plus MDA-7/IL-24 enhances mda-7/IL-24 protein. Cells were infected with Ad.vec, Ad.CMV-mda-7, or Ad.PEG-mda-7 and untreated or treated with IR the next day. Protein lysates were prepared 24 h after IR and Western blotting was performed as described in Materials and Methods to determine the levels of MDA-7/IL-24 protein. Equal protein loading was confirmed by Western blotting with an EF-1α antibody.

DISCUSSION

We presently demonstrate a potentially clinically relevant phenomenon that a combination of mda-7/IL-24 with IR promotes apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells that are initially resistant to either agent used alone. In ovarian cancer cells, IR (at 2 Gy) or mda-7/IL-24 (either as Ad.CMV-mda-7 or as Ad.PEG-mda-7) alone did not significantly affect cell growth, except for SKOV3 cells, whereas a combination of both agents significantly reduced cell viability in all four ovarian cancer cell lines examined in the present study. Furthermore, we demonstrate that simultaneous treatment of IR plus mda-7/IL-24 could override the translational block of mda-7/IL-24 mRNA into protein in ovarian cancer cells, which could explain the enhanced efficacy of this combinatorial approach.

Several tumor-specific or ovarian cell carcinoma-specific promoters have been investigated in the preclinical settings. Robertson et al. (1998) found that a plasmid containing the HSV/TK gene, under the SLP1 (secretory leukoproteinase inhibitor gene, which is highly expressed in a variety of epithelial tumors, including ovarian cancer) promoter, could kill ovarian cancer cell. Another study (Tanyi et al., 2002) reported increased Luc production in several types of epithelial cancer cell lines, including ovarian cancer cell lines, with minimal activity in non-epithelial and immortalized normal cell lines when delivered under the control of SLP1 promoter. However, the same group found some non-specific Luc activity in many cell types, using OSP1, a retroviral promoter reported to be transcriptionally active only in rat ovaries. In our present study, besides the CMV promoter, we used the PEG-Prom to control mda-7/IL-24 gene expression (Su et al., 2000, 2001b, 2005b) selectively in cancer cells. We demonstrate that Ad.PEG-mda-7 induced apoptosis selectively in cancer cells without inducing harmful effects to normal human mesothelial cells. The advantage of using the PEG-Prom is that its cancer cell specificity is attributed to two transcription factors, PEA-3 and AP-1, which are overexpressed in >90% of cancers. Additionally, the PEG-Prom is functionally active in all cancer cells irrespective of their p53, Rb, or other tumor suppressor gene status. Thus, employing the PEG-Prom to drive transgene expression only in cancer cells has selective advantages over other tissue- or cancer-specific promoters.

Consistent with a previous report (Leath et al., 2004), this study demonstrates that mda-7/IL-24 induces a low and variable degree of apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells when delivered via a replication-incompetent adeno-virus under the control of either the CMV or PEG promoters. One of the reasons for this finding is low expression of MDA-7/IL-24 protein due to low Ad-mediated mda-7/IL-24 gene delivery. However, defects (or blocks) in signaling mechanisms contributing to this low apoptosis induction require investigation. Currently, the signaling mechanisms involved in mda-7/IL-24-mediated apoptosis induction in specific ovarian cancer cells remain incompletely understood. Previous studies showed that activation of p38 MAPK plays an important role in mediating Ad.mda-7-induced apoptosis in melanoma, prostate carcinoma, and malignant glioma cells (Sarkar et al., 2002; Lebedeva et al., 2005a; Gupta et al., 2006). Using only one ovarian cancer cell line, a recent report showed that induction of the FAS-FASL pathway mediates Ad.mda-7-mediated cell killing (Gopalan et al., 2005). However, in this study we demonstrate that both Ad.CMV-mda-7 and Ad.PEG-mda-7 activated the p38 MAPK pathway in ovarian cancer cells and the level of phosphorylated p38 MAPK correlated with the killing effect of Ad.CMV-mda-7 and Ad.PEG-mda-7 in these cells. Additionally, SB203580, a selective p38 MAPK inhibitor significantly abolished the mda-7/IL-24-induced killing effect. Thus, activation of p38 MAPK might be a key element in mda-7/IL-24-induced apoptosis induction in multiple cell types, including ovarian carcinoma.

To circumvent the limitation of low transduction efficiency, we were interested in defining strategies that could be utilized to improve delivery of mda-7/IL-24, especially to those cells that were most resistant (SKOV3.ip1, HEY). Treatment options for ovarian cancer patients frequently involve debulking surgery combined with various therapeutic approaches, including radiation, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and recently anti-angiogenic therapy (Wolf and Jenkins, 2002; Jemal et al., 2004). In this context, methods enhancing the effectiveness of anti-cancer agents, without promoting toxicity, would be of immense value and could provide a means of significantly improving clinical responses. Studies in NSCLC (Kawabe et al., 2002) and malignant gliomas (Su et al., 2003; Yacoub et al., 2003b,c) formally showed that radiation enhances tumor cell sensitivity to mda-7/IL-24. In two recent studies (Su et al., 2005a, 2006), we have uncovered an important property of mda-7/IL-24: an ability to induce a potent radiation enhancement “bystander anti-tumor effect” not only in cancer cells inherently sensitive to this cytokine but also in tumor cells overexpressing the anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-2 or BCL-xL and exhibiting resistance to the cytotoxic effects of both radiation and MDA-7/IL-24. These findings offer promise for dramatically expanding the use of mda-7/IL-24 for cancer therapy, especially in the context of radiation therapy. Additionally, recent reports indicate that Ad.mda-7 lethality in NSCLC cells can also be augmented by combination treatment with the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug sulindac (Oida et al., 2005) and that Ad.mda-7 amplifies the anti-tumor effects of Herceptin (trastuzumab), an anti-p185ErbB2 murine monoclonal antibody (mAb) that binds to the extracellular domain of ErbB2, in breast carcinoma cells overexpressing HER-2/neu (McKenzie et al., 2004). Overall, these studies employing radiation, a chemotherapeutic agent, and a mAb reinforce the possibility of augmenting the anti-cancer activity of mda-7/IL-24 and increasing its therapeutic index as a gene therapy for diverse cancers by using combinatorial therapy approaches (Fisher, 2005; Gupta et al., 2006). Our present studies reveal that radiation might be an effective component of the combinatorial treatment for ovarian cancer cells along with Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7.

In summary, a combination of IR plus mda-7/IL-24 (administered as Ad.CMV-mda-7 or Ad.PEG-mda-7) enhances apoptosis induction in ovarian cancer cells, which initially demonstrated relative resistance to either of these agents alone. In contrast, similar experimental protocols applied to normal human mesothelial cells do not induce significant harmful effects. The unique synergy in ovarian cancer cells correlates with the ability of IR to relieve the translational block preventing conversion of mda-7/IL-24 mRNA into protein. These in vitro data suggest that combination treatment of Ad.mda-7 and IR has potential to increase tumor response to radiotherapy and/or gene therapy and warrants further investigation using in vivo tumor models.

Acknowledgments

The present studies were supported in part by NIH grants R01 CA083821, R01 CA097318, R01 CA098712, P01 CA104177, UAB ovarian SPORE career development award NIH/NCIP50 CA83591, and Gynecology Foundation pilot Award; Army DOD Idea Development Award W81XWH-05-1-0035; the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation; and the Chernow Endowment. PBF is a Michael and Stella Chernow Urological Cancer Research Scientist and a SWCRF Investigator.

Footnotes

Contract grant sponsor: NIH; Contract grant numbers: R01 CA083821, R01 CA097318, R01 CA098712, P01 CA104177; Contract grant sponsor: Army DOD Idea Development Award; Contract grant number: W81XWH-05-1-0035; Contract grant sponsor: The Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation; Contract grant sponsor: Chernow Endowment.

LITERATURE CITED

- Alvarez RD, Curiel DT. A phase I study of recombinant adenovirus vector-mediated delivery of an anti-erbB-2 single-chain (sFv) antibody gene for previously treated ovarian and extraovarian cancer patients. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:229–242. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.2-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez RD, Gomez-Navarro J, Wang M, Barnes MN, Strong TV, Arani RB, Arafat W, Hughes JV, Siegal GP, Curiel DT. Adenoviral-mediated suicide gene therapy for ovarian cancer. Mol Ther. 2000;2:524–530. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes MN, Deshane JS, Rosenfeld M, Siegal GP, Curiel DT, Alvarez RD. Gene therapy and ovarian cancer: A review. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado E, Gomez-Navarro J, Yamamoto M, Adachi Y, Coolidge CJ, Arafat WO, Barker SD, Wang MH, Mahasreshti PJ, Hemminki A, Gonzalez-Baron M, Barnes MN, Pustilnik TB, Siegal GP, Alvarez RD, Curiel DT. Strategies to accomplish targeted expression of transgenes in ovarian cancer for molecular therapeutic applications. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2496–2504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian J, Thomas H. Ovarian cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27:99–109. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2001.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinet P, Lanvin D, Vereecque R, Quesnel B, Querleu D. (Gene therapy and ovarian cancer: Update of clinical trials) J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2000;29:532–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CC, Chada S, Merritt JA, Tong A, Senzer N, Zhang Y, Mhashilkar A, Parker K, Vukelja S, Richards D, Hood J, Coffee K, Nemunaitis J. Clinical and local biological effects of an intratumoral injection of mda-7 (IL24; INGN 241) in patients with advanced carcinoma: A phase I study. Mol Ther. 2005;11:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PB. Is mda-7/IL-24 a “magic bullet” for cancer? Cancer Res. 2005;65:10128–10138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PB, Gopalkrishnan RV, Chada S, Ramesh R, Grimm EA, Rosenfeld MR, Curiel DT, Dent P. mda-7/IL-24, a novel cancer selective apoptosis inducing cytokine gene: From the laboratory into the clinic. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:S23–S37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Navarro J, Siegal GP, Alvarez RD, Curiel DT. Gene therapy: Ovarian carcinoma as the paradigm. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;109:444–467. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/109.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan B, Litvak A, Sharma S, Mhashilkar AM, Chada S, Ramesh R. Activation of the Fas-FasL signaling pathway by MDA-7/IL-24 kills human ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3017–3024. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, Su ZZ, Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Sauane M, Emdad L, Bachelor MA, Grant S, Curiel DT, Dent P, Fisher PB. mda-7/IL-24: Multifunctional cancer-specific apoptosis-inducing cytokine. Pharmacol Ther. 2006 2006 Feb 3; doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.11.005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, Ward E, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:8–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe S, Nishikawa T, Munshi A, Roth JA, Chada S, Meyn RE. Adenovirus-mediated mda-7 gene expression radiosensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells via TP53-independent mechanisms. Mol Ther. 2002;6:637–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leath CA, III, Kataram M, Bhagavatula P, Gopalkrishnan RV, Dent P, Fisher PB, Pereboev A, Carey D, Lebedeva IV, Haisma HJ, Alvarez RD, Curiel DT, Mahasreshti PJ. Infectivity enhanced adenoviral-mediated mda-7/IL-24 gene therapy for ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedeva IV, Sauane M, Gopalkrishnan RV, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Gupta P, Nemunaitis J, Cunningham C, Yacoub A, Dent P, Fisher PB. mda-7/IL-24: Exploiting cancer’s Achilles’ heel. Mol Ther. 2005a;11:4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedeva IV, Su ZZ, Sarkar D, Gopalkrishnan RV, Waxman S, Yacoub A, Dent P, Fisher PB. Induction of reactive oxygen species renders mutant and wild-type K-ras pancreatic carcinoma cells susceptible to Ad.mda-7-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2005b;24:585–596. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Gopalkrishnan RV, Athar M, Randolph A, Valerie K, Dent P, Fisher PB. Molecular target-based therapy of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2403–2413. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie T, Liu Y, Fanale M, Swisher SG, Chada S, Hunt KK. Combination therapy of Ad-mda7 and trastuzumab increases cell death in Her-2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Surgery. 2004;136:437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oida Y, Gopalan B, Miyahara R, Inoue S, Branch CD, Mhashilkar AM, Lin E, Bekele BN, Roth JA, Chada S, Ramesh R. Sulindac enhances adenoviral vector expressing mda-7/IL-24-mediated apoptosis in human lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:291–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pataer A, Vorburger SA, Barber GN, Chada S, Mhashilkar AM, Zou-Yang H, Stewart AL, Balachandran S, Roth JA, Hunt KK, Swisher SG. Adenoviral transfer of the melanoma differentiation-associated gene 7 (mda7) induces apoptosis of lung cancer cells via up-regulation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) Cancer Res. 2002;62:2239–2243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MW, III, Barnes MN, Rancourt C, Wang M, Grim J, Alvarez RD, Siegal GP, Curiel DT. Gene therapy for ovarian carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:397–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki T, Mhashilkar A, Swanson X, Zou-Yang XH, Sieger K, Kawabe S, Branch CD, Zumstein L, Meyn RE, Roth JA, Chada S, Ramesh R. Inhibition of human lung cancer growth following adenovirus-mediated mda-7 gene expression in vivo. Oncogene. 2002;21:4558–4566. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Lebedeva IV, Sauane M, Gopalkrishnan RV, Valerie K, Dent P, Fisher PB. mda-7 (IL-24) mediates selective apoptosis in human melanoma cells by inducing the coordinated overexpression of the GADD family of genes by means of p38 MAPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10054–10059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152327199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Vozhilla N, Park ES, Gupta P, Fisher PB. Dual cancer-specific targeting strategy cures primary and distant breast carcinomas in nude mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005a;102:14034–14039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506837102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Vozhilla N, Park ES, Randolph A, Valerie K, Fisher PB. Targeted virus replication plus immunotherapy eradicates primary and distant pancreatic tumors in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2005b;65:9056–9063. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauane M, Gopalkrishnan RV, Choo HT, Gupta P, Lebedeva IV, Yacoub A, Dent P, Fisher PB. Mechanistic aspects of mda-7/IL-24 cancer cell selectivity analysed via a bacterial fusion protein. Oncogene. 2004;23:7679–7690. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Shi Y, Fisher PB. Subtraction hybridization identifies a transformation progression-associated gene PEG-3 with sequence homology to a growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9125–9130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Goldstein NI, Jiang H, Wang MN, Duigou GJ, Young CS, Fisher PB. PEG-3, a nontransforming cancer progression gene, is a positive regulator of cancer aggressiveness and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15115–15120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Shi Y, Fisher PB. Cooperation between AP1 and PEA3 sites within the progression elevated gene-3 (PEG-3) promoter regulate basal and differential expression of PEG-3 during progression of the oncogenic phenotype in transformed rat embryo cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:3411–3421. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Lebedeva IV, Gopalkrishnan RV, Goldstein NI, Stein CA, Reed JC, Dent P, Fisher PB. A combinatorial approach for selectively inducing programmed cell death in human pancreatic cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001a;98:10332–10337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171315198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Shi Y, Friedman R, Qiao L, McKinstry R, Hinman D, Dent P, Fisher PB. PEA3 sites within the progression elevated gene-3 (PEG-3) promoter and mitogen-activated protein kinase contribute to differential PEG-3 expression in Ha-ras and v-rafoncogene transformed rat embryo cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001b;29:1661–1671. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.8.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Gopalkrishnan RV, Sauane M, Sigmon C, Yacoub A, Valerie K, Dent P, Fisher PB. Melanoma differentiation associated gene-7, mda-7/IL-24, selectively induces growth suppression, apoptosis and radiosensitization in malignant gliomas in a p53-independent manner. Oncogene. 2003;22:1164–1180. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Emdad L, Sauane M, Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Gupta P, James CD, Randolph A, Valerie K, Walter MR, Dent P, Fisher PB. Unique aspects of mda-7/IL-24 antitumor bystander activity: Establishing a role for secretion of MDA-7/IL-24 protein by normal cells. Oncogene. 2005a;24:7552–7566. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Sarkar D, Emdad L, Duigou GJ, Young CS, Ware J, Randolph A, Valerie K, Fisher PB. Targeting gene expression selectively in cancer cells by using the progression-elevated gene-3 promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005b;102:1059–1064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409141102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZZ, Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Emdad L, Gupta P, Kitada S, Dent P, Reed JC, Fisher PB. Ionizing radiation enhances therapeutic activity of mda-7/IL-24: Overcoming radiation- and mda-7/IL-24-resistance in prostate cancer cells overexpressing the antiapoptotic proteins bcl-xL or bcl-2. Oncogene. 2006;25:2339–2348. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanyi JL, Lapushin R, Eder A, Auersperg N, Tabassam FH, Roth JA, Gu J, Fang B, Mills GB, Wolf J. Identification of tissue- and cancer-selective promoters for the introduction of genes into human ovarian cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:451–458. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong AW, Nemunaitis J, Su D, Zhang Y, Cunningham C, Senzer N, Netto G, Rich D, Mhashilkar A, Parker K, Coffee K, Ramesh R, Ekmekcioglu S, Grimm EA, van Wart Hood J, Merritt J, Chada S. Intratumoral injection of INGN 241, a nonreplicating adenovector expressing the melanoma-differentiation associated gene-7 (mda-7/IL24): Biologic outcome in advanced cancer patients. Mol Ther. 2005;11:160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf JK, Jenkins AD. Gene therapy for ovarian cancer (review) Int J Oncol. 2002;21:461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacoub A, Mitchell C, Brannon J, Rosenberg E, Qiao L, McKinstry R, Linehan WM, Su ZS, Sarkar D, Lebedeva IV, Valerie K, Gopalkrishnan RV, Grant S, Fisher PB, Dent P. MDA-7 (interleukin-24) inhibits the proliferation of renal carcinoma cells and interacts with free radicals to promote cell death and loss of reproductive capacity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003a;2:623–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacoub A, Mitchell C, Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, McKinstry R, Gopalkrishnan RV, Grant S, Fisher PB, Dent P. mda-7 (IL-24) inhibits growth and enhances radiosensitivity of glioma cells in vitro via JNK signaling. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003b;2:347–353. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacoub A, Mitchell C, Lister A, Lebedeva IV, Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Sigmon C, McKinstry R, Ramakrishnan V, Qiao L, Broaddus WC, Gopalkrishnan RV, Grant S, Fisher PB, Dent P. Melanoma differentiation-associated 7 (interleukin 24) inhibits growth and enhances radiosensitivity of glioma cells in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2003c;9:3272–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeimet AG, Marth C. Why did p53 gene therapy fail in ovarian cancer? Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:415–422. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]