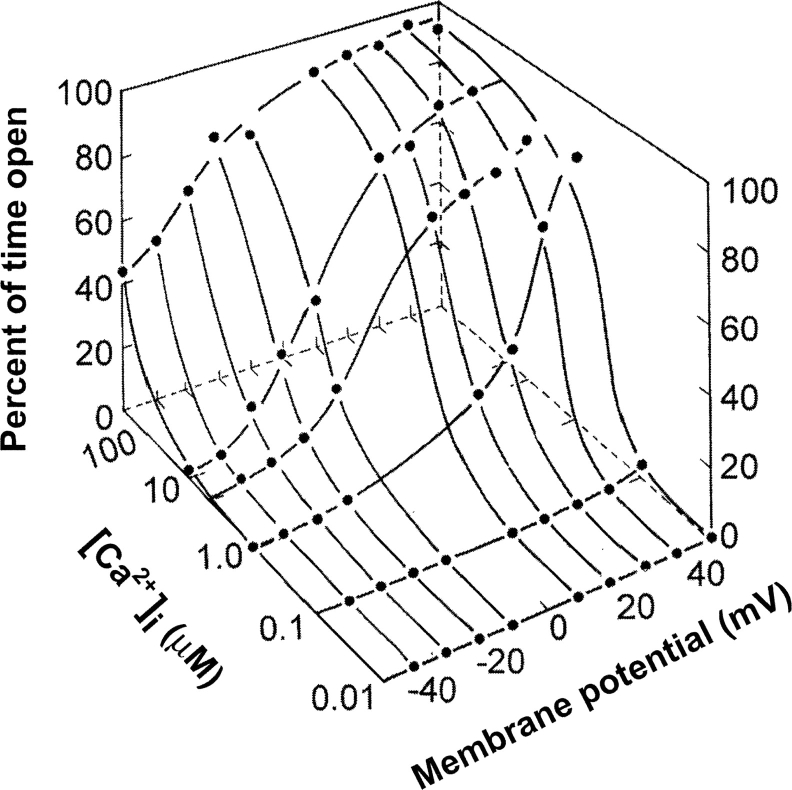

Large conductance calcium- and voltage-activated K+ channels (Slo1), also referred to as “BK” or “maxi K” channels because of their high single channel conductance (250–300 pS in symmetrical 150 mM KCl), are widely distributed in many different tissues (Kaczorowski et al., 1996). A signature feature of BK channels, in addition to their high K+ selectivity and conductance, is that they are activated in a highly synergistic manner by both intracellular calcium ion (Ca2+ i) and depolarization (Marty, 1981; Pallotta et al., 1981; Barrett et al., 1982; Latorre et al., 1982). This is shown in Fig. 1 , which plots channel open probability Po (z axis) versus Ca2+ i (y axis) and membrane potential (x axis). It is this synergistic activation that allows BK channels to play key roles in controlling excitability in a number of systems, including regulating the contraction of smooth muscle, the tuning of hair cells in the cochlea, and regulation of transmitter release (Robitaille et al., 1993; Ramanathan et al., 1999; Brenner et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2001). It is also this synergistic activation together with the high single-channel conductance and the infrequent gating transitions to subconductance levels that has made the BK channel such an attractive subject for the study of gating mechanism. The dual activation of the channel allows the Po to be biased into optimal ranges for the study of activation by either voltage or Ca2+ i by appropriate setting of the other parameter.

Figure 1.

BK channels are activated synergistically by Ca2+ i and depolarization (Barrett et al., 1982). Po, the percentage of time that the channel is open, is plotted against Ca2+ i and membrane potential. Appreciable channel activity requires both depolarization from the typical resting membrane potentials and elevation of Ca2+ i above the typical resting level of 0.1 μM.

This review will focus on this author's highly biased view of some of the key experiments and observations that have helped formulate our current concept of how BK channels gate. Due to space limitations, the modulation of the gating by β subunits is not included, and most of the papers to be discussed will be recent papers that are providing the final flashy assault to the summit, rather than the earlier studies providing the crucial stepwise slog up the mountain. The progress toward understanding how BK channels gate is based on three complimentary and essential approaches: kinetic analysis, molecular biology, and 3-D structure. The greatest progress has been made on kinetics and molecular biology. There is not yet a structure of BK channels, but there are structures of related K+ channels from bacteria.

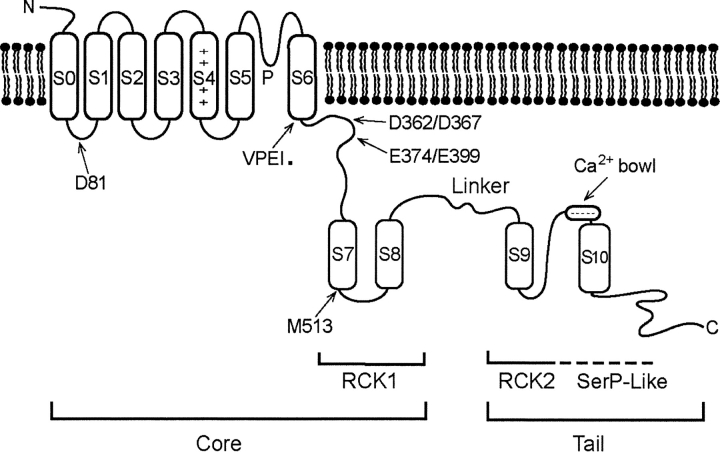

BK channels are tetramers (Shen et al., 1994). A schematic diagram of one of the four α subunits that assemble to form functional channels is shown in Fig. 2 . Similar to the superfamily of voltage gated K+ channels (Butler et al., 1990; Isacoff et al., 1990; Wei et al., 1990), BK channels contain transmembrane segments S1–S6, including an S4 voltage sensor and a P region to form the selectivity filter of the pore (Adelman et al., 1992; Butler et al., 1993; Diaz et al., 1998; Cui and Aldrich, 2000). In addition, BK channels have an S0 segment that places the NH2 terminus extracellular (Meera et al., 1997) and a very large intracellular COOH terminus that contains more than twice the number of amino acid residues that are contained in S0–S6 (Adelman et al., 1992; Butler et al., 1993). Wei et al. (1994) found that they could cut the channel at an unconserved linker between S8 and S9 (see Fig. 2) and then express functional channels from the separate cores and tails. The core can be further subdivided into the transmembrane segments S0–S6 and an intracellular RCK1 domain (regulator of the conductance of potassium; Jiang et al., 2001), to be discussed later. Further studies from Salkoff's laboratory identified the first Ca2+ regulatory site for BK channels, the Ca2+ bowl, which includes five consecutive aspartate residues just before S10 (Schreiber and Salkoff, 1997; Schreiber et al., 1998).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the α subunit of BK channels. The Ca2+ bowl, M513, and D362/D367 indicate sites on Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms that when mutated decrease the high affinity Ca2+ sensitivity. D81 is a similar type of site, but is much less effective. E374/E399 defines a site on a Ca2+/Mg2+ regulatory mechanism that when mutated decreases the low affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ sensitivity. VPEI precedes the position of the stop codon at 323 to make a truncated subunit (Piskorowski and Aldrich, 2002). The various named parts of the channel are indicated. The core and tail domain are connected by a nonconserved linker that also connects the RCK1 and the putative RCK2 domains (details in text).

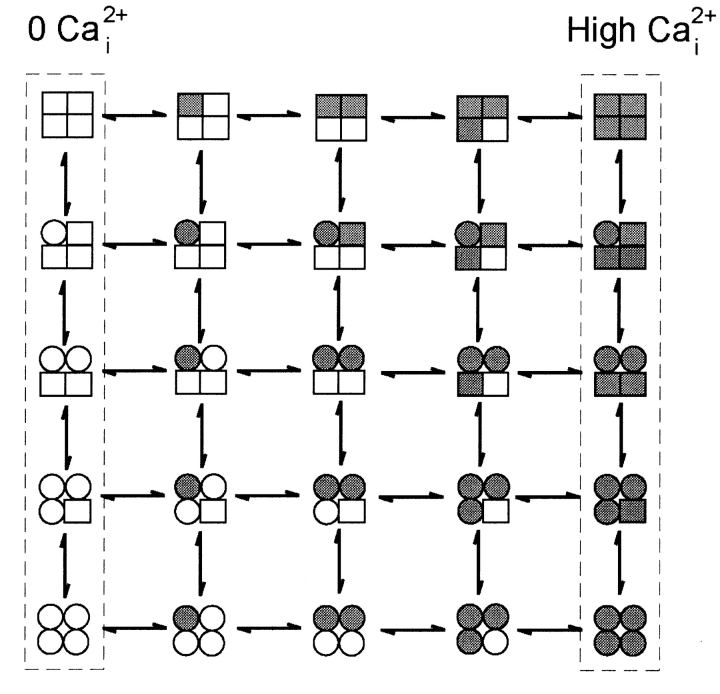

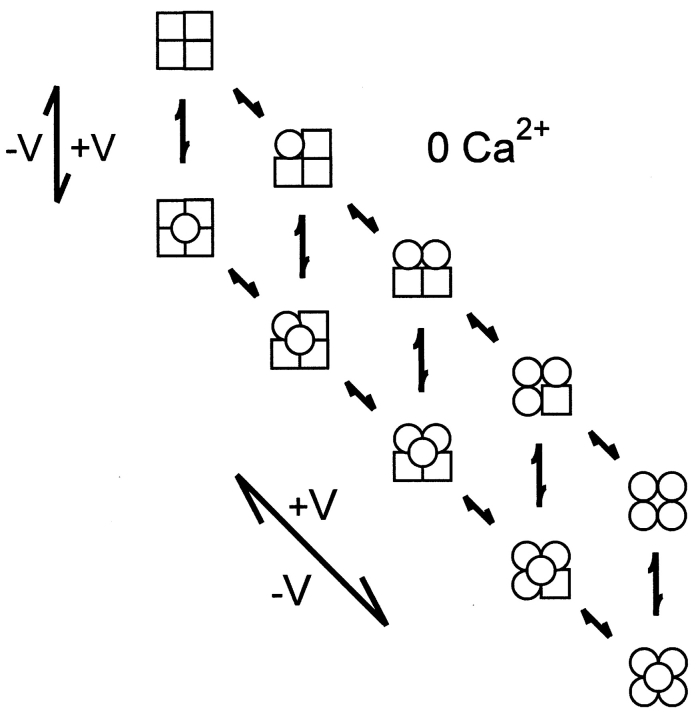

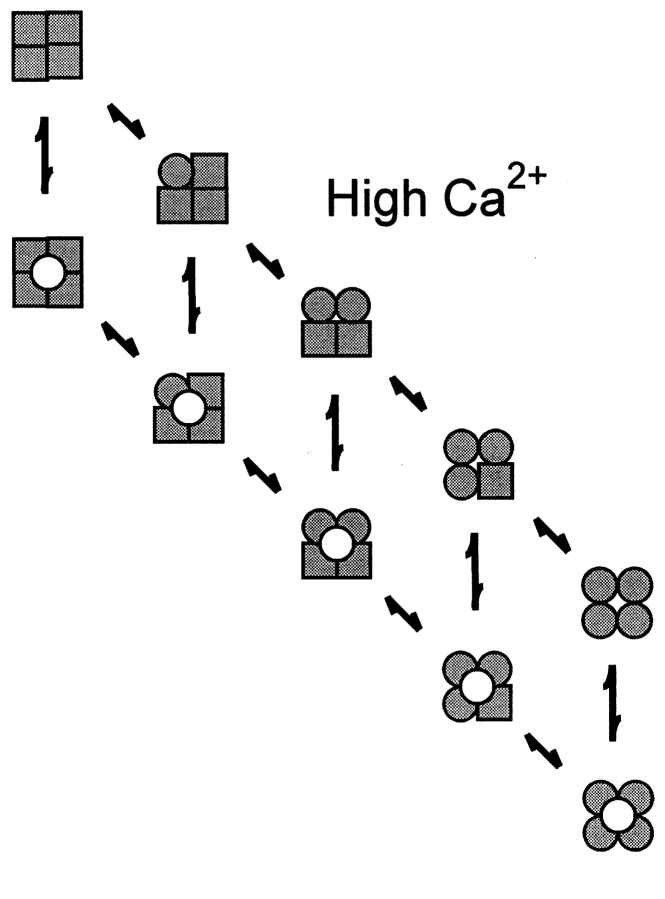

The Minimal Theoretical Kinetic Model for the Gating of a Tetrameric Channel with both Voltage and Ca2+ Sensors on Each Subunit Is Given by the Eigen Model

Given the information of one voltage sensor per subunit and at least one Ca2+ binding site per subunit (it will be argued later that there are at least three Ca2+ binding sites per subunit), what might be the minimal expected kinetic gating mechanism for BK channels? This question was addressed indirectly by Eigen (1968) for hemoglobin (also a ligand binding tetramer) long before the first single-channel recordings. A simplified diagram of the Eigen model (Fersht, 1984), as applied to BK channels, is shown in Scheme I, where there are 25 states. The large numbers of states arise because each of the four subunits can exist in four different configurations. Squares indicate voltage sensors in the relaxed conformation, circles indicate voltage sensors in the active conformation, unshaded squares and circles indicate the absence of bound Ca2+, and shaded squares and circles indicate that a Ca2+ is bound to the subunit. Since binding and conformational changes would not be expected to occur exactly simultaneously, there are no diagonal pathways connecting the different states. Scheme I is a simplification of the 35–55 possible states that would arise if channels with diagonal and adjacent subunits in different configurations have different properties (Eigen, 1968; Cox et al., 1997; Rothberg and Magleby, 1999). Twenty-five states may seem overwhelming, but this number follows immediately from a tetramer in which each subunit can exist in four different configurations due to activation by voltage and Ca2+. Notice in Scheme II that the Eigen model condenses to the 10-state MWC model (Monod et al., 1965) if the four voltage sensors always move in a concerted manner.

SCHEME I.

SCHEME II.

While the Eigen model is complex and is difficult to test without simplifying assumptions about which of the states are open and which are closed and the types of interactions among the subunits, it can be reduced to a much simpler gating mechanism with only five states by experimental manipulation. With 0 Ca2+ i, the gating would be confined to the five states in the leftmost column where no Ca2+ is bound, and with saturating Ca2+ i, the gating would be effectively confined to the five states in the rightmost column with four bound Ca2+ per channel (Scheme I). A simple test of the Eigen model, then, would be to determine whether the channel gates in five or fewer states, as all states may not be entered or be detected, under the conditions of 0 and saturating concentrations of Ca2+ i. The same approach can be used to test the MWC model, where the channel should gate in a maximum of two states with 0 and saturating concentrations of Ca2+ i.

The Eigen and MWC Models Are too Simple for the Gating of BK Channels

Proposed gating mechanisms for ion channels, such as Scheme I, are typically assumed to represent discrete state Markov models, in which the rate constants for leaving any given state remain constant in time for constant experimental conditions (Colquhoun and Hawkes, 1981). This assumption appears valid for BK channels, where the kinetic time constants of the gating are independent of previous single-channel activity (McManus and Magleby, 1989). The number of kinetic states can be estimated for discrete state Markov models by fitting the distributions of the open and closed interval durations (dwell-time distributions) with sums of exponential components. The number of significant exponential components then indicates the minimal number of kinetic states, as not all states may be detected due to overlapping time constants and/or small magnitudes of the exponential components (Colquhoun and Hawkes, 1981; McManus and Magleby, 1988). Estimates of the numbers of kinetic states entered during gating in 0 Ca2+ typically give 2–3 open states plus 4–5 closed states for a total of 6–9 kinetic states (Nimigean and Magleby, 2000; Talukder and Aldrich, 2000), and estimates in saturating Ca2+ i give 3–4 open plus 5–6 closed states for a total of 8–10 kinetic states (Rothberg and Magleby, 1999). Clearly, experimentally observed gating in a minimum of 6–9 kinetic states in 0 Ca2+ and 8–10 kinetic states in saturating Ca2+ i are inconsistent with both the Eigen model, which predicts gating in a maximum of five kinetic states under each extreme condition (Scheme I), and also the MWC model, which predicts gating in a maximum of two states under each extreme condition (Scheme II).

An alternative method of testing the Eigen and MWC models is to examine whether there is correlation between the durations of adjacent open and closed intervals. In both 0 Ca2+ i and saturating Ca2+ i, these models predict a linear gating mechanisms, shown by the dashed boxes in Schemes I and II. While the Eigen model (which was for hemoglobin) does not specify which of the states are open and which are closed, if, for purposes of discussion, it is assumed that the top three rows in Scheme I are closed states and the bottom two rows are open states, then the gating mechanism in saturating Ca2+ i is given by Scheme III, which has a single transition pathway between the open and closed states. Consequently, this scheme predicts that there would be no correlation between the durations of adjacent intervals (Fredkin et al., 1985; McManus et al., 1985; Colquhoun and Hawkes, 1987). Examination of the durations of adjacent intervals from BK channels in saturating Ca2+ i indicates a very pronounced correlation: shorter open intervals are preferentially adjacent to longer closed intervals, and longer open intervals are preferentially adjacent to briefer closed intervals (McManus et al., 1985; Rothberg and Magleby, 1998, 1999). Such a correlation requires that there be at least two independent transition pathways between open and closed states, in contrast to Scheme III from the Eigen model in saturating Ca2+, which has a single transition pathway. Thus, the observation under 0 and saturating Ca2+ of gating in more than five kinetics states and also of correlations between adjacent open and closed intervals in saturating Ca2+ indicates that the Eigen model is too simple to account for the gating of BK channels, and can be rejected. On the same basis, the MWC model (Scheme II) can also be rejected, as it predicts only two states and also no correlations under extreme gating conditions.

SCHEME III.

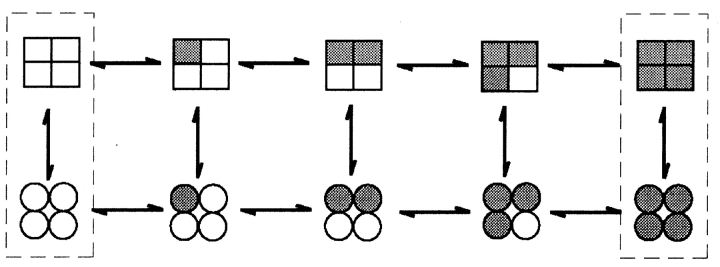

Two-tiered Gating Mechanisms Are Minimal Gating Mechanisms for BK Channels

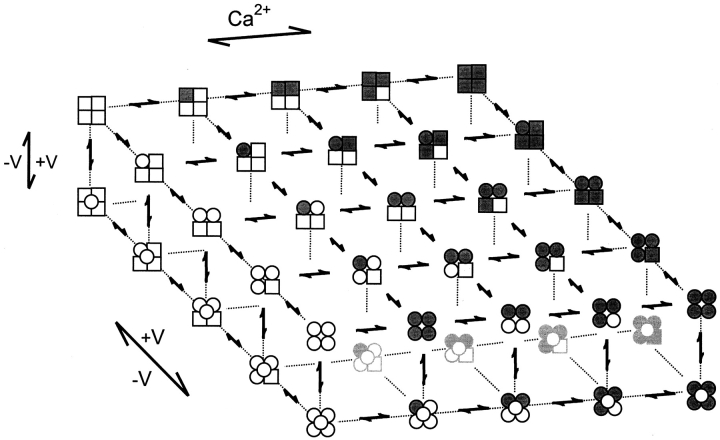

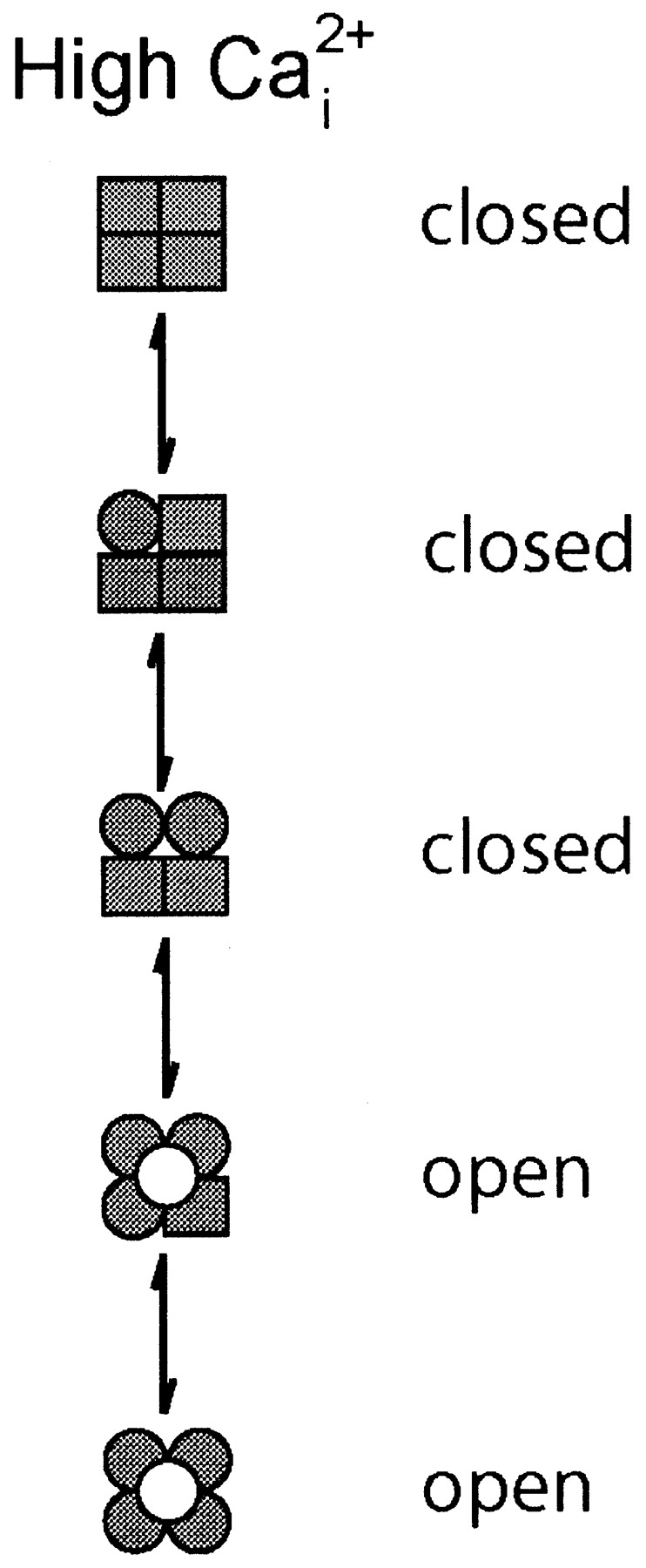

If the Eigen model is too simple, how then does the channel gate? Detailed kinetic analysis suggests that the gating at 0 Ca2+ (Horrigan and Aldrich, 1999, 2002; Horrigan et al., 1999; Nimigean and Magleby, 2000; Rothberg and Magleby, 2000) and saturating Ca2+ (Rothberg and Magleby, 1999, 2000) are both consistent with at least a 10-state model in each case, as indicated by Schemes IV and V. These schemes are expansions of the Eigen model at the extreme conditions of 0 Ca2+ i (Scheme IV) and saturating Ca2+ i (Scheme V), with the further assumption that each of the states predicted by the Eigen model can exist in two major conformations: closed (top tier) and open (bottom tier). The requirement for two-tiered gating mechanisms suggests that the Ca2+ sensors and voltage sensors move separately from the open-closed conformational change. Such separation of the sensor movement from the opening/closing transitions is also observed for other channels (Marks and Jones, 1992; Rios et al., 1993; McCormack et al., 1994). It immediately follows from Schemes I, IV, and V that the complete gating mechanism for all ranges of Ca2+ i, rather than just extreme conditions, would be given by the 50-state two-tiered model in Scheme VI (Horrigan and Aldrich, 1999; Horrigan et al., 1999; Rothberg and Magleby, 1999, 2000; Cox and Aldrich, 2000; Cui and Aldrich, 2000).

SCHEME IV.

SCHEME V.

SCHEME VI.

Rothberg and Magleby (2000) examined Scheme VI to identify the voltage-dependent steps and determine whether it could account for the Ca2+ and voltage dependence of the gating. They approached this problem by reducing Scheme VI to a simpler two-tiered scheme that would be more amenable to kinetic analysis by reducing the numbers of states by combining some of the states and deleting others that would be seldom entered, and by reducing the number of possible transition pathways from 105 to 33. Computation time for Q-matrix calculations is related to the square of the numbers of states, so such a reduction in states allowed the fitting to be performed about fourfold faster, saving years of computing time. Rothberg and Magleby (2000) estimated parameters for rate constants and their voltage and Ca2+ dependence by simultaneously fitting 6–10 sets of single-channel data obtained over wide ranges of voltages and Ca2+ i, using two-dimensional methods to take into account the correlation information. Most parameters were allowed to be free, with some limits being placed by also fitting at the extremes of 0 and saturating Ca2+ i, which confined the gating to Schemes IV and V, respectively. They found that a reduced Scheme VI could account for the Ca2+ and voltage dependence of the single-channel kinetics (dwell-time distributions) over wide ranges of Ca2+ i (0–1024 μM), voltage (−80 to 80 mV), and Po (10−4 to 0.96). The reduced Scheme VI also predicted single-channel current records visually indistinguishable from those observed experimentally.

The voltage dependence of the gating was found to arise mainly from voltage-dependent transitions among closed states (-C-C-) and among open states (-O-O-) associated with movement of the voltage sensors, with less voltage dependence for transitions between open and closed states (C-O), and with no voltage dependence for Ca2+ binding and unbinding. Since a reduced Scheme VI could account for the data, they concluded that the full Scheme VI should give as good or better descriptions of the single-channel kinetics than the reduced scheme.

Horrigan et al. (1999) and Horrigan and Aldrich (1999) in a pair of elaborate papers have also carefully examined the underlying mechanism of the voltage-dependent gating of BK channels through studies of the ionic and gating currents in 0 Ca2+ i. Some of their key observations are that a fast component of gating charge moves faster than the opening and closing of the channel, and that there is an additional component of gating charge that moves at the same time as the channel opening and closing. These observations suggest that the voltage sensors can move independently and before the closing-opening transitions, and that the closing-opening transition itself is also voltage dependent. They also observed that the deactivation of the K+ current was not strictly exponential but started with a brief delay, which would suggest that the deactivation can proceed through several opening states before closing. With these and many additional observations, they were able to define the rate constants and their voltage dependence for gating in 0 Ca2+ i for the 10-state model described by Scheme IV (see commentary by Jones, 1999). This model could account for the relative positions of the channels G/V and Q/V curves and the kinetics of ionic current activation and deactivation as well as the anomalous curvature of the G/V relations at very low open probability. Further studies, measuring macro currents over very wide ranges of Ca2+ and voltage (Cox and Aldrich, 2000; Cui and Aldrich, 2000; Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002; see commentary by Lingle, 2002), found that Scheme VI with an assumption of independent Ca2+ and voltage sensors that modulate gating through allosteric action on the opening-closing conformational changes, was consistent with the gating of the channel, including the pronounced Ca2+ dependence of the kinetics.

The relative voltage dependencies of the various transitions from the study of single-channel kinetics by Rothberg and Magleby (2000) after correcting for the reduced numbers of states in their model, were the same (within experimental error) as those determined by Horrigan et al. (1999) and Horrigan and Aldrich (1999) from their exhaustive study of the macroscopic currents in the absence of Ca2+ (see Rothberg and Magleby (2000), where this comparison is made). Similar conclusions from two such different approaches by different laboratories lends support to the voltage-dependent steps indicated in Scheme VI, as well as the general applicability of Scheme VI to BK channels. Thus, Scheme VI can serve as a working hypothesis for the gating of BK channels. In terms of Scheme VI, with 0 Ca2+ i and −300 mV (Po < 10−6), the channel spends most of its time in the top left closed state on the top tier, and with 100 μM Ca2+ and 300 mV (Po > 0.96) the channel spends most of its time in the bottom right open state on the bottom tier.

The large multistate multitier Scheme VI is consistent with most of the observations on BK channels. For example, Scheme VI predicts charge movement can occur for BK channels after they are open due to movement between the rows of open states on the lower tier. Such charge movement is observed (Stefani et al., 1997; Horrigan and Aldrich, 1999). BK channels gate with Hill slopes for activation by Ca2+ ranging from 1–6, but typically between 2–4 (McManus, 1991), consistent with the four Ca2+ binding sites per channel. Scheme VI is also consistent with the observations that MWC type models (Scheme II) can describe the gating over wide ranges of Ca2+ at a fixed voltage, as long as the extremes approaching 0 and saturating Ca2+ are excluded (McManus and Magleby, 1991; Wu et al., 1995). The reason for this is that for any fixed voltage, the gating of Scheme VI could be effectively collapsed into the much simpler MWC model (Rothberg and Magleby, 1999, 2000). For the same reason, MWC-like models with voltage sensors replacing the Ca2+ sensors are generally consistent with the effects of voltage on the gating for extreme Ca2+ i (Horrigan et al., 1999; Cox and Aldrich, 2000; Cui and Aldrich, 2000), where the gating would be confined to the leftmost (Scheme IV) or rightmost (Scheme V) columns of states for 0 and saturating Ca2+ i, respectively.

(Relatively) Independent Ca2+ and Voltages Sensors Act Jointly to Activate BK Channels

While a number of detailed kinetic studies have found that an assumption of independent voltage and Ca2+ sensors working through separate allosteric activators is consistent with the experimental observations (Cui and Aldrich, 2000; Cox and Aldrich, 2000; Zhang et al., 2001), two recent studies have examined this assumption more directly. Both find that the high affinity Ca2+ sensors and voltage sensors work relatively independently of one another to increase the open equilibrium, but that there are some interactions. In the first of these studies, Horrigan and Aldrich (2002), in a tour de force study using gating and ionic currents recorded from macro patches, found that Ca2+ i has little effect on the on-component of gating current, suggesting that Ca2+ binding has little effect on the voltage sensors. They also found that Ca2+ i can increase Po >1,000-fold at extreme negative potentials when the voltage sensors are not activated, suggesting the Ca2+ sensors can act relatively independently from the voltage sensors (see commentary by Lingle, 2002). Thus, each activated Ca2+ and voltage sensor acts relatively independently to further increase Po from a very low level (∼10−6 at 0 mV and 0 Ca2+ i) to ∼0.96 at depolarized voltages and high Ca2+ i.

In the second recent study examining the contributions of the sensors to the gating, Niu and Magleby (2002) focused on the Ca2+ sensors. They mutated the Ca2+ bowl to inactivate a high affinity Ca2+ regulatory mechanism, and then examined channels with different numbers of functional Ca2+ bowls. For channels with 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 functional Ca2+ bowls, the Hill coefficients for activation by Ca2+ i were 1.4, 1.7, 2.5, 3.5, and 4.1, respectively, and the Ca2+ i for half activation, KD, was 687, 54.5, 16.4, 5.44, 3.4 μM, respectively. They found that these stepwise increases in Hill coefficients and stepwise decreases in apparent KDs that occurred as the number of Ca2+ bowls was increased could be accounted for with a model (Shi and Cui, 2001; Zhang et al., 2001) with 0–4 high affinity Ca2+ sensors (given by the number of functional Ca2+ bowls), four low affinity Ca2+ sensors, and four voltage sensors. In this model, which is an extension of Scheme VI (see below), the various sensors were independent of one another, acting jointly (synergistically) to increase the open equilibrium. The stepwise shifts in the data as the number of functional Ca2+ bowls increased was well described by changing a single parameter in the model, the number of functional high affinity Ca2+ sensors to match the known number for each channel. Although an assumption of independence exactly described the shifts in KDs, there were some differences between the observed and predicted Hill coefficients, indicating that additional factors not included in the model were involved, such as interactions between the various sensors or additional Ca2+ binding sites. In this model with an assumption of independence among the Ca2+ and voltage sensors, the cooperativity in activation of the channel by Ca2+ i does not arise from interactions among the Ca2+ binding sites, as the binding at each site is the same independent of the number of bound sites, but from the combined action of the Ca2+ sensors on the opening-closing transitions.

Functionally, BK Channels Are Ca2+ and Voltage-activated Channels

It has been contemplated over the years whether BK channels are Ca2+-activated channels modulated by voltage, or voltage-activated channels modulated by Ca2+ i. From a mechanistic viewpoint, neither answer appears correct, since BK channels can be activated by either Ca2+ or voltage acting through separate allosteric mechanisms that converge on a common step, the opening/closing transition (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002). Thus, Ca2+ and voltage can both activate and modulate channel activity. In living cells, where voltage is between −90 and 30 mV and Ca2+ ranges from 0.1 to perhaps as much as 20 μM (near a Ca2+ channel), both depolarization and increased Ca2+ i are required for any appreciable activation of BK channels. For example, with high Ca2+ i (20 μM), but little depolarization (V = −90 mV), or maximum depolarization (30 mV) and little Ca2+ i (0.1 μM), Po is insignificant (<0.001). Only with both depolarization and increased Ca2+ i is there appreciable activation of the channel, as shown by the synergistic action in Fig. 1. In addition to activation by Ca2+ and voltage, BK channels are also activated by millimolar Mg2+ (see below).

Scheme VI Must be Expanded to Include an Additional Tier of Closed States

Scheme VI has been presented in detail since it is the simplest scheme that captures the major features of the gating of BK channels over a wide range of voltages and Ca2+ i (<100 μM). Scheme VI with essentially free rate constants does generate the kinetics of the single-channel data including the flickers (brief closings) that are a characteristic of channel gating (Rothberg and Magleby, 1999, 2000), but Scheme VI with reasonably constrained rate constants, as required for independence of the voltage and Ca2+ sensors, generates too few flickers (Cox et al., 1997; Rothberg and Magleby, 2000), suggesting that more states may be needed. An additional tier of brief closed states does significantly improve the fits to single channel data at high Ca2+ i (Rothberg and Magleby, 1999), and preliminary data obtained at the extremes of Ca2+ and voltage also suggest that an additional tier of brief closed states is required (Niu and Magleby, 2001). Direct examination of the flickers and opening/closing transitions indicates that the channel can open through at least two states, one of brief duration and reduced conductance, and that at least some of the flickers may involve closings to this state (Ferguson et al., 1993). Finally, the kinetics of single-channel and macroscopic currents suggest more than one step in the opening/closing transition (Rothberg and Magleby, 1998; Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002), and detailed kinetic studies with the β3 subunit unmask two distinct voltage-dependent activation steps (Zeng et al., 2001). Together, these observations suggest an additional tier of brief closed states, interposed as a middle tier between the two tiers in Scheme VI, although it has not yet been excluded that the additional tier is below the bottom (open) tier. Adding this additional tier to Scheme VI would increase the states to 75.

Scheme VI Must be Expanded to Include Additional Ca2+ Sensors

As presented, Scheme VI has only one Ca2+ sensor on each subunit that is associated with a high affinity (<10 μM) Ca2+ binding site. However, as pointed out by Zhang et al. (2001), the Ca2+ sensitivity of BK channels spans four orders of magnitude, a much wider range than would be expected for a single class of Ca2+ binding sites. Consistent with this observation, Schreiber and Salkoff (1997) have presented data for additional Ca2+ binding sites, and Shi and Cui (2001) and Zhang et al. (2001) have characterized at least two classes of Ca2+ sensors: the high affinity Ca2+ sensor associated with the Ca2+ bowl characterized previously, and a low affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ sensor that is activated by either mM Ca2+ i or Mg2+ i. With a high and low affinity Ca2+ sensor on each subunit, Scheme VI would need to be expanded to 250 states (Zhang et al., 2001). It was this 250-state model with independent high and low affinity Ca2+ sensors and voltage sensors that Niu and Magleby (2002) used to account for the changes in gating associated with changes in the number of functional Ca2+ bowls. As will be discussed below, there is evidence for a second high affinity Ca2+ sensor in addition to the Ca2+ bowl. Adding this additional Ca2+ sensor, giving three per subunit would increase the potential number of states to 1,250, and adding an additional tier of closed states (as discussed above), would then increase the number of potential states to 1,875.

While a goal in kinetic modeling is to find the models with the fewest numbers of states that are consistent with the experimental results, for tetrameric channels with multiple classes of allosteric activators, large multistate models with multiple tiers are the simplest models that are consistent with the known structural and kinetic properties of BK channels. These models extend the concepts conceived by Eigen (1968) over three decades ago for allosteric tetrameric proteins to ion channels. While the number of potential states of the BK channel is high, the basic working hypothesis of how the channel functions remains simple: each allosteric activator works (almost) independently to increase the open probability. With this simplifying assumption, which, incredibly enough, appears reasonably consistent with the gating of BK channels, the complex gating of BK channels can then described with a limited number of parameters (Cox and Aldrich, 2000; Magleby and Rothberg, 2001; Shi and Cui, 2001; Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002; Niu and Magleby, 2002; Shi et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2002). Furthermore, since it is possible to study each type of activator in relative isolation by controlling the experimental conditions and/or through mutations that uncouple the various classes of sensors singly or in combination, it should be possible to clearly specify the parameters that will describe the gating of the channel, even for the most complex models.

Where Are the Voltage Sensors?

The kinetic model for the gating of BK channels summarized by Scheme VI includes two different types of voltage-dependent steps. The first is the movement of the four voltage sensors indicated by transitions between circles and squares. These conformational changes occur on both the closed and open tiers by movement between the rows on each tier. The second is the opening/closing transitions between the closed states on the top tier and the open states on the bottom tier. Whether these two different types of voltage-dependent steps arise from a single voltage sensor is not clear. Consistent with the idea that the charged S4 transmembrane segment forms a voltage sensor for BK channels (Diaz et al., 1998; Cui and Aldrich, 2000), the voltage dependence of BK channels (11–15 mV per e-fold change in Po) is less than for Shaker (2.3–3.5 mV per e-fold change in Po), as might be expected since BK channels have only four positive charges on each S4 segment, two of which appear to contribute to the gating (Diaz et al., 1998), whereas Shaker K+ channels have seven positive charges on each S4 segment, four of which appear to contribute to the gating (Gonzalez et al., 2001). Although the kinetic properties of the voltage sensors are well characterized in BK channels (Horrigan et al., 1999; Horrigan and Aldrich, 1999, 2002), there has been little direct study of the structural mechanism by which the movement of the voltage sensors in BK channels is coupled to channel opening, but some features may have similarities to those extensively studied in other K+ channels where S4 is also a voltage sensor (Papazian et al., 1987; Perozo et al., 1994; Aggarwal and MacKinnon, 1996; Seoh et al., 1996; Yellen, 1998, 2002; Bezanilla, 2000; Horn, 2002). Extending the extensive structural studies of voltage-dependent gating for K+ channels to the voltage-dependent gating of BK channels will be a necessary step toward understanding gating mechanism.

Philosophy of Mutational/Substitutional Studies to Locate Ca2+ Sensors

Before considering where the Ca2+ binding sites may be located, it is useful to review the well-known limitations of assigning function to structure using mutational studies or substitutional studies in which parts from different channels are swapped. Only Ca2+ sensors will be considered in this discussion, although many of the same arguments would apply to voltage sensors. Assume for purposes of discussion that each Ca2+ sensor in a BK channel consists of at least two parts: the Ca2+ binding site and the linker that connects the binding site to the gate for channel opening and closing. If a mutation/substitution removes or greatly decreases the functional Ca2+ sensitivity, but otherwise the channel gates normally, then there are at least three possible explanations: (a) the mutation/substitution disrupts the Ca2+ binding site so that Ca2+ no longer binds; (b) the mutation/substitution disrupts the linker between the Ca2+ binding site and the gate, so that the binding information is not transferred to the gate; or (c) the mutation/substitution alters some other part of the channel that prevents the binding site/linker combination from opening the channel. These three types of responses could occur through direct action, or through allosteric action from a distance. For ease of writing, the sites of the mutations that alter the Ca2+ sensitivity will be referred to as the Ca2+ sensors or Ca2+ regulatory sites, with the full understanding that mutations at such sites may be acting either directly or indirectly to alter Ca2+ sensitivity in one or more of the three different ways discussed above.

BK Channels have Three or More Ca2+ Sensors

At least three different types of Ca2+ sensors that act relatively independent of one another to increase the activity of BK channels have been associated with each subunit of the BK channel. The locations of these sensors are indicated in Fig. 2, and the properties of the sensors are summarized in Table I . The high affinity sensors are the Ca2+ bowl, D362/D367, M513, and D81. D362/D367 and M513 may identify the same regulatory mechanism, although this in not entirely clear. E374/E399 is a low affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ site.

TABLE I.

Ca2+ and Mg2+ Regulatory Mechanisms for Slo1 BK Channels

| Mutation site | Ion | KD closed | KD open | Location | V equivalenta | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μM | μM | mV | ||||

| High affinity | Ca2+ | |||||

| Ca2+ bowl | 3.5–4.5 | 0.6–2.0 | RCK2? | 60–80 |

Schreiber and Salkoff, 1997; Bian et al., 2001; Braun and Sy, 2001; Bao et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2002 |

|

| M513 | 3.5–3.8 | 0.8–0.9 | RCK1 | 70–80 | Bao et al., 2002 | |

| D362/D367 | 17.2 ± 4.0 | 4.6 ± 1.0 | RCK1 | 60–80 | Xia et al., 2002 | |

| D81 | S0–S1 | 10–30 | Braun and Sy, 2001 | |||

| Low affinity | Ca2+/Mg2+ | RCK1 | ∼60 | |||

| E374/E399 | Mg2+ | 60–70 | Shi et al., 2002 | |||

| Ca2+ | 4.1 ± 3.5 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 50–70 | Xia et al., 2002 | ||

| 2.3–3.1 | 0.5–0.9 | 50–70 | Zhang et al., 2001 | |||

| Mg2+ | 9–22 | 2–6 | 70 | Zhang et al., 2001 | ||

| 15 | 3.6 | 75 | Shi and Cui, 2001 | |||

| High affinity | Ca2+ | |||||

| Δ896–903 + M513I | ∼125 | Bao et al., 2002 | ||||

| D(897–901)N + D362A/D367A | ∼140 | Xia et al., 2002 | ||||

| D895N + D81N | ∼80 | Braun and Sy, 2001 |

V equivalent is the shift required in the voltage to maintain the same Po of 0.5 after the indicated mutations in the presence of 10–100 μM Ca2+ i for the high affinity sites and 10 mM Ca2+ i or Mg2+ i for the low affinity sites.

All sequence numbers are adjusted to the sequence with EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ accession no. L16912 (Butler et al., 1993) from Nucleotide in PubMed with the numbering starting at the second M (MDALI). The mutations that identify each site and identifying sequence are: The Ca2+ bowl is defined by Sequence I in the text. Various mutations in this region that greatly reduce Ca2+ sensitivity typically include one or more of the five consecutive aspartates (D897–901), such as D(897–901)N or D897–898 deleted, or the D895N which changes the D two residues before the string of aspartates. M513I identified by MRSFIK. D362A/D367A identified by DFLHKD. D81N identified by DEKEE. E399A identified by EFYQG.

The High Affinity Ca2+ Regulatory Mechanism Associated with the Ca2+ Bowl

Schreiber and Salkoff (1997) and Schreiber et al. (1999) were the first to identify the Ca2+ bowl as a high affinity Ca2+ regulatory site. The Ca2+ bowl is located just before S10 in the tail domain of the COOH terminus (Fig. 2), and includes 10 negative charges, 5 of which are derived from five consecutive aspartate residues, as evident in the Ca2+ bowl sequence from the mouse:

883 TELVNDTNVQFLDQDDDDDPDTELYLTQ

(Sequence 1)

Except for one residue (889), this sequence is completely conserved between nematode, fly, mouse, and human (Schreiber and Salkoff, 1997). The evidence that the Ca2+ bowl is associated with a high affinity Ca2+ regulator site is considerable. Removing or replacing negative charges in the Ca2+ bowl greatly decreases the Ca2+ sensitivity (Schreiber and Salkoff, 1997). Slo3, a BK-like channel that lacks an obvious Ca2+ bowl, has considerably less Ca2+ sensitivity than Slo1 (Schreiber et al., 1998). Replacing the tail of Slo1 with the tail from Slo3 to form a Slo1 core/Slo3 tail channel greatly reduces the Ca2+ sensitivity, which can be partially restored by replacing residues in the Slo3 tail with 34 residues including the Ca2+ bowl from the Slo1 tail (Schreiber et al., 1999). Finally, Slo2, a BK-like channel that is synergistically activated by both Ca2+ and Cl−, has both positive and negative charges in the Ca2+ bowl region (Yuan et al., 2000).

Because BK channels can be activated by either Ca2+ or depolarization (Fig. 1), it is possible to quantify the effect of a mutation on the loss of Ca2+ sensitivity in terms of the depolarization required to compensate for the loss of Ca2+ sensitivity. For example, for a fixed Ca2+ i, the voltage required to half activate the channel before the mutation is compared with the voltage required to half activate the channel after the mutation. The rightward shift (depolarization) required to restore the activity of the mutated channel then gives a quantitative measure of the loss in Ca2+ sensitivity. It is the dual activation of BK channels by voltage and Ca2+ that enables BK channels to provide such a powerful tool to study mechanism. Manipulations of the channel that would normally shift the Po to values either too low or too high to study can be examined by using either Ca2+ or voltage to bias the activity of the channel into a suitable range of Po for study, just as the position knob on an oscilloscope moves the response into a range that can be seen.

Bao et al. (2002) and Xia et al. (2002) have extended the characterization of the Ca2+ bowl using additional mutations and analysis. They find, consistent with the observations of Schreiber and Salkoff (1997), that mutations that either replace (with alanine or asparagine) or delete 5–9 amino acids in the heart of the Ca2+ bowl (including the five consecutive aspartate residues) right shift the voltage required to half activate the channel ∼70 mV in the depolarizing direction in the presence of 10 μM Ca2+ i. From Fig. 1 it can be seen that a 70 mV shift represents a large equivalent decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity due to mutation of the Ca2+ bowl. Yet in the absence of Ca2+ i, the mutations had little effect on either the voltage required to half activate the channel or on the steepness of the G-V curves. This lack of effect on the gating in the absence of Ca2+ i, compared with the pronounced effects with Ca2+ i, suggest that the mutations are acting on a specific Ca2+ regulatory mechanism, rather than by interfering with the general gating machinery of the channel (Schreiber and Salkoff, 1997; Bao et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2002).

More specifically, Bao et al. (2002) argue from theoretical grounds that the mutations must either be reducing the change in affinity at the binding site for Ca2+ that occurs with channel opening, or reducing the number of Ca2+ binding sites. Both of these possibilities would be consistent with the idea that the mutations to the Ca2+ bowl are either destroying a high affinity Ca2+ binding site directly or uncoupling the binding site from the gating machinery. Further evidence that the Ca2+ bowl is a critical part of a high affinity Ca2+ regulatory mechanism are the observations of Niu and Magleby (2002) that each functional Ca2+ bowl adds a step increase of 0.3–0.8 to the cooperativity (Hill coefficient) for activation by Ca2+ i. Estimates of the KDs for the Ca2+ regulatory site associated with the Ca2+ bowl are ∼4 μM for the closed channel and ∼1 μM for the open channel (Bao et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2002), consistent with a high affinity site (Table I).

While all of the observations discussed above are consistent with the idea that the Ca2+ bowl is a key part of a high affinity Ca2+ regulatory site, they do not directly establish that the Ca2+ bowl is the Ca2+ binding site, because, as discussed above, the various mutations and substitutions could act either directly by disrupting binding or indirectly by uncoupling or blocking coupling. To draw an example from another channel, a cluster of negative charges modulates the activity of the CFTR channel at a step that is downstream of ATP binding, perhaps by establishing interdomain linkage (Fu et al., 2001). On a similar basis, if the Ca2+ bowl is not the binding site, then it might provide a critical structural linkage to a cluster of positive charges located on another domain of the channel. Mutating or removing the Ca2+ bowl would then uncouple this linkage, and replacing the negative charges in the Ca2+ bowl could then restore this linkage.

Nevertheless, binding experiments do suggest that the Ca2+ bowl can act as a Ca2+ binding site. Braun and Sy (2001) found that a bacterial protein incorporating a ∼240 amino acid fragment from the COOH terminus of the BK channel that included the Ca2+ bowl bound Ca2+, whereas the bacterial protein alone did not. Similarly, Bian et al. (2001) found that 280 residues, including the Ca2+ bowl from the COOH terminus of BK channels bound Ca2+, and that mutating the negative aspartate residues in the Ca2+ bowl to the uncharged asparagine, then reduced the Ca2+ binding by 56%. The binding of Ca2+ to Ca2+ bowl containing fragments of the channel suggests that the Ca2+ bowl may be the binding site, but this is not conclusive, as it might be expected that five consecutive negative charges, as found in the Ca2+ bowl, would bind Ca2+. Dynamic studies of Ca2+ binding to the Ca2+ bowl in intact functioning channels of known open and closed configuration would help resolve this question.

The High Affinity M513 Ca2+ Regulatory Mechanism

Even though mutations to the Ca2+ bowl greatly shifted the Ca2+ sensitivity, Schreiber and Salkoff (1997) found that BK channels were still Ca2+ sensitive over a wide range of concentrations (from 5 μM to 1 mM) after mutation of the Ca2+ bowl, suggesting one or more additional Ca2+ regulatory sites. In addition, Schreiber and Salkoff (1997) found that the Ca2+ bowl sensor was only sensitive to Ca2+, whereas the residual Ca2+ sensitivity after mutating the Ca2+ bowl could be activated by Cd2+ as well as Ca2+. This differential effect suggests that the residual Ca2+ sensitivity arose from a physically different site than the Ca2+ bowl.

While searching for the additional Ca2+ sensors, Bao et al. (2002) found that mutating residue M513 in the RCK1 domain at the end of S7 (Fig. 2), reduced Ca2+ sensitivity equivalent to an ∼70 mV depolarization in 10 μM Ca2+ i, the same magnitude shift as a Ca2+ bowl mutation. Combining a Ca2+ bowl mutation with the M513I mutation then reduced the Ca2+ sensitivity equivalent to a ∼125 mV shift in voltage (Table I). Hence, the combined effects of the Ca2+ bowl mutations (∼70 mV) and M513I (∼70 mV) were almost additive, suggesting that these two sites define two separate and relatively independent Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms of the channel. The high affinity (<10 μM) response for Ca2+ i was lost after mutating both the Ca2+ bowl and M513. In 100 μM Ca2+ i, the Ca2+ bowl plus M513I mutant still displayed some Ca2+ sensitivity, equivalent to a 25–50 mV shift, which can be compared with a ∼200 mV shift without the mutation. Thus, the double mutant removed the high Ca2+ sensitivity and also much of the intermediate Ca2+ sensitivity.

The High Affinity D362/D367 Regulatory Mechanism

While searching for Ca2+ sensors in addition to the Ca2+ bowl, Xia et al. (2002) explored three aspartate residues that are conserved in Slo1 channels (D362, D367, and D369), but are positively charged or neutral in Slo3, a channel with little or no high affinity Ca2+ sensitivity (Schreiber et al., 1998; Moss and Magleby, 2001). They found that the D362A/D367A mutation reduced Ca2+ sensitivity equivalent to a 60-mV depolarization at 10 μM Ca2+ i and a 80-mV depolarization for 100 μM Ca2+ i (Table I). The combination of a Ca2+ bowl mutation together with D362A/D367A removed all of the Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel for Ca2+ i < 1 mM. The shift from mutating both sites was 120 mV at 10 μM Ca2+ i and 160 mV at 100 μM Ca2+ i. The summed shifts from the combined Ca2+ bowl mutation and D362A/D367A were similar to the shift induced by both mutations together, and this was the case over a wide range of Ca2+ i, suggesting that these two high affinity Ca2+ sites work relatively independently of one another. This observation of independence for the Ca2+ bowl and D362/D367 sites is similar to the observation of independence for the Ca2+ bowl and M513 sites (Bao et al., 2002), and indicates that the individual mutations do not act by blocking the gating mechanism of the channel. If this were the case, then one mutation should knock out the effects of the other mutation.

Estimates of the KDs for the Ca2+ binding site controlled by M513 were 3.5–3.8 μM for the closed state and 0.8–0.9 μM for the open state (Bao et al., 2002), and for the site controlled by D362/D367 were 17.2 μM for the closed state and 4.6 μM for the open state (Xia et al., 2002). These estimates differ by a factor of four between the two studies, suggesting possible differences in action of the mutations. In addition, the Ca2+ bowl paired with the D262/D367 site removes all the Ca2+ sensitivity for Ca2+ i < 1 mM, whereas the Ca2+ bowl paired with the M513 site only removes all Ca2+ sensitivity for Ca2+ i < 10 μM. Thus, the M513A and D362A/D367A mutations may be acting in a different manner, although they may still be affecting a common regulatory mechanism.

The Low Affinity E374/E399 Ca2+/Mg2+ Regulatory Mechanism

Shi and Cui (2001) and Zhang et al. (2001) have characterized a low affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ regulatory site that is associated with a nonselective divalent cation sensor activated by millimolar concentrations of Ca2+ or Mg (see commentary by Magleby, 2001). Activation of the Ca2+/Mg2+ regulatory site by either 10 mM Ca2+ or 10 mM Mg2+, or 10 mM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+ applied together all produced an ∼60 mV shift (Shi and Cui, 2001; Zhang et al., 2001), indicating that Ca2+ and Mg2+ activate a common site. The contribution of the low affinity regulatory site to the gating could be accounted for with a 250 state model (discussed above) in which the low affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ sensors were independent of the high affinity Ca2+ and voltage sensors. The KDs for Mg2+ binding to the low affinity regulatory site ranged from 9–22 mM for the closed state and 2–6 mM for the open state, and the KDs for Ca2+ binding to the low affinity site ranged from 2–6 mM for the closed state and 0.5–2 mM Ca2+ for the open state. Since the free Ca2+ i under physiological conditions is 2–4 orders of magnitude less than that of the typically millimolar Mg2+ i inside cells, the low affinity site would be occupied by Mg2+ rather than Ca2+ under physiological conditions.

In addition to binding to the low affinity site, Mg2+ can also bind to the high affinity sites with equal KDs of ∼5 mM for the open and closed states (Shi and Cui, 2001; Zhang et al., 2001). With equal KDs for the high affinity sites in the open and closed states of the channel, Mg2+ alone would not activate the channel through binding to the high affinity sites, but could displace Ca2+ from these sites, decreasing the activating effects of low levels of Ca2+ i. While Mg2+ binding to the low affinity site would act to enhance the function of BK channels under physiological conditions, the inhibitory effects on the high affinity sites lead to a complex overall effect of Mg2+ i as the Ca2+ i is changed (Shi and Cui, 2001).

Shi and Cui (2001) localized the low affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ regulatory site to the core of the BK channel (Fig. 2) by observing that when the tail of Slo1 channels is replaced with the tail from Slo3 channels, that the chimeric Slo1 core/Slo3 tail channels still retained their low affinity Mg2+ sensitivity. Since Slo3 channels are not activated by Mg2+ i, then the Mg2+ regulatory sites must be on the core rather than the tail.

Recent studies from the laboratories of Cui and Lingle have more specifically located the low affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ regulatory mechanism to the RCK1 domain of the core of the channel and shown that it includes E374 and E399 (Shi et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2002). As a guide to localize this site, Xia et al. (2002) compared the sequence of Slo3 to Slo1 and found that the negatively charged glutamate residue, E399, is conserved in mammalian, fly, and worm Slo1 sequences, but is a neutral asparagine in Slo3. Mutation of E399 to alanine greatly decreases the activation of the channel by mM Ca2+ or Mg2+ (Shi et al., 2002; Xia et al., 2002). In addition, E374A and Q397C also reduce the shift induced by mM Mg2+ (Shi et al., 2002). Using the RCK domain of E. coli K+ channels as a structural guide (Jiang et al., 2001, 2002a), Shi et al. (2002) suggest that E374, E399, and Q397 in the RCK1 domain of BK channels form a Mg2+ binding site. Interestingly, this proposed low affinity binding site for Ca2+/Mg2+ in the RCK1 domain of BK channels is a different site and shifted from the low affinity site described for Ca2+ binding by Jiang et al. (2002a) in the RCK1 domain of bacterial K+ channels.

Xia et al. (2002) were able to account for the effects of eight various combinations of mutations of the high affinity (Ca2+ bowl and D362/D367) and low affinity (E399) regulatory mechanisms by assuming an allosteric model with three different independent Ca2+ binding sites. Interestingly, they also found that Ca2+ may act as an inverse agonist on one of the regulators in a triple mutated channel (Ca2+ bowl, D362/D367 and E399), indicating that the mutations may strengthen the binding affinity of the closed state for one of the sites.

A Physical Gating Mechanism for a Bacterial Ca2+-sensitive K+ Channel

Structural studies by Jiang et al. (2002a)(b) suggest that the Ca2+-dependent gating of MthK, a bacterial channel activated by millimolar Ca2+, is controlled by eight identical RCK domains (regulators of the conductance of K+). Four of these (RCK1) arise from a COOH terminus domain attached to each of the four α subunits, and four are assembled from solution (RCK2). These eight RCK domains form a proposed gating ring that hangs beneath the channel in the intracellular solution. Each of the eight RCK domains has a fixed and a flexible interface. Jiang et al. (2002a) propose that the binding of two Ca2+ at each of the four flexible interfaces then induces conformational changes in the gating ring that pull on the linkers connecting each RCK1 to the intracellular end of the inner helix, opening the channels.

By comparison to MthK, Jiang et al. (2002a) have proposed that BK channels have two tandem RCK domains in the COOH terminus. On this basis, RCK1 in BK channels would include S7 and S8 and RCK2 would start at S9 (see Fig. 2). Thus, RCK2 domains for BK channels would not assemble from solution, as in MthK channels, but are connected directly to the RCK1 domains through the nonconserved linker (Fig. 2). Interestingly, it was the nonconserved amino acids in the COOH terminus between S8 and S9 that suggested to Wei et al. (1994) that it might be possible to separate the channel into core and tail domains. They found that when the cores and tails of BK channels were expressed separately, that the tails would assemble from solution to form functional channels with the cores, just as the RCK2 domains can assemble from solution for MthK channels.

While there are stretches of semiconserved sequence throughout the RCK domain of MthK channels and the RCK1 domain of BK channels (Jiang et al., 2001, 2002a), and also between the first ∼100 amino acids of the RCK domain of MthK and the putative RCK2 domain of BK channels (Lingle, C., personal communication), any similarity after the first ∼100 amino acids of the putative RCK2 domain is less clear. The Ca2+ bowl, which starts after ∼180 residues into the putative RCK2 domain of BK channels is absent from the RCK1 domains of both MthK and BK channels. Since the RCK1 and RCK2 domains of MthK are identical, the Ca2+ bowl is absent from MthK. Either included in the putative RCK2 domain of BK channels, or tacked on as additional sequence, is a serine proteinase–like domain (Moss et al., 1996) which is also absent from RCK1 domains of MthK and BK channels.

Unlike BK channels that are regulated by both high and low affinity Ca2+ sensors, MthK channels appear to lack high affinity Ca2+ sensors all together, as MthK channels are activated by millimolar Ca2+ i (Jiang et al., 2002a). Consistent with this difference, the sites associated with the high affinity Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms in BK channels are absent in MthK channels. There is no indication of a Ca2+ bowl in MthK (as mentioned above), and the equivalent of D367 and M513 are also missing from RCK1 in MthK, being represented by dashes in the alignment (Jiang et al., 2002a). Another major difference between MthK and BK channels is that the Ca2+-coordinating sites for the low affinity activation of MthK (D184, E210, and E212) appear to be replaced with the uncharged L, Q, and L, respectively, in the RCK1 of BK channels (Jiang et al., 2002a). This is consistent with the observation (mentioned previously) that the proposed low affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ site for BK channels (E399, E374, Q397) is located in a different position than is found in the Rossmann fold in MthK (Shi et al., 2002). Thus, even if BK channels have the equivalent of eight RCK domains as MthK does, some striking differences in sequence and Ca2+ activation of these two different channels suggests that there will be differences in the regulation of the gating. Focusing on these differences in future studies could help resolve the gating mechanisms of both channels.

Alternative and/or Additional Ca2+ Regulatory Mechanisms

Since all the Ca2+ sensitivity of BK channels can be removed by mutating three sites in the RCK1 and putative RCK2 domains (the Ca2+ bowl, D362/D367, and E374/E399), the question arises whether all of the functional Ca2+ binding sites for the Ca2+ sensors are also located in the RCK1 and RCK2 domains? A recent study by Piskorowski and Aldrich (2002) suggests that this does not have to be the case. Piskorowski and Aldrich (2002) chopped the entire COOH terminus, which would include the RCK domains from the BK channel by placing a stop codon within the end of the S6 transmembrane segment at I323 to convert VPEIIEL to VPEI(STOP) (Fig. 2). The ∼2.4 kb of wild-type coding sequence after the inserted stop condon was removed from the vector. They found that the Ca2+ sensitivity of the truncated channel was similar to that of the wild-type channel over the examined range of Ca2+, from 2–300 μM. They argued against endogenous channels by identifying the truncated channels with a mutation to change the sensitivity to block by TEA. They also reported similar findings for truncated channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes and HEK cells, which would reduce, but not exclude the possibility, that endogenous RCK like domains might assemble with the chopped channels to provide Ca2+ sensitivity.

If the truncated channels were expressed without any endogenous RCK type domains, then the observations of Piskorowski and Aldrich (2002) would require that there are high affinity Ca2+ binding sites on the intracellular domains between S0 and S6 that can regulate the gating of the channel. Braun and Sy (2001) did identify one site on the intracellular linker between S0 and S1, but this site in the intact channel was only sufficient to account for ∼10–30% of the high affinity Ca2+ sensitivity. To account for the observations of Piskorowski and Aldrich (2002), either this site would have to be much more effective in the truncated channel, or an additional site would need to be found. Piskorowski and Aldrich (2002) did not look at low affinity activation, so it is not known whether the truncated channel possess a low affinity site.

As briefly summarized in earlier sections, the data suggest overwhelming that BK channels have at least three relatively independent Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms identified by mutations to the Ca2+ bowl, D362/D367 (or M513), and E374/E399 that remove all Ca2+ sensitivity for intact channels. The mutations that identify these three sites are located on the RCK domains that are missing from the truncated channel, and there is indirect evidence, summarized previously, suggesting that at least two of these sites may bind Ca2+. In addition, swapping the tail of the BK channel (an RCK domain) with the tail from Slo3, a BK-like channel, has pronounced effects on the kinetics (Schreiber et al., 1998; Moss and Magleby, 2001). Thus, the observations of Piskorowski and Aldrich (2002) that are the most difficult to explain are that the Ca2+ sensitivity and kinetics of the truncated channels appear so similar to those of wild-type channels. This is best seen in the single-channel records and plots in their Fig. 2 (although they also show a decrease in mean open time in their Fig. 3). Since tampering with the RCK domains contained in the ∼800 amino acids attached to S6 in the wild-type channels can have such pronounced effects on the Ca2+ sensitivity and gating, as reviewed above, it is not clear why the complete removal of all ∼800 amino acids in the truncated channels would have such little effect.

If the observations of Piskorowski and Aldrich (2002) do arise from truncated channels that are not associated with any endogenous RCK-like domains, then their findings would indicate that high affinity Ca2+-dependent gating for truncated channels does not require RCK domains or the gating ring that they form. Such an observation does not exclude that RCK domains and gating rings are key structures involved in the Ca2+-dependent gating of intact channels, nor does it exclude that the Ca2+ binding sites for the three regulatory mechanisms are located on the RCK domains. Perhaps two different systems, one associated with S0–S6, and the other with the RCK domains provide Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms. Repeating all the same detailed kinetic experiments and analysis on the truncated channels that have been performed on the wild-type channels, as well as searching for binding sites on S0–S6 that have appreciable effects on the Ca2+ sensitivity could clarify which properties of the channel arise from S0–S6 and which from the RCK domains. Another possibility is that truncating the channel may reveal a Ca2+ regulatory system that is not functional in wild-type channels (gain of function mutation).

Conclusion

Considerable progress has been made toward understanding the underlying basis for the Ca2+ and voltage-dependent gating of BK channels. To a first approximation, the kinetic-gating mechanism appears consistent with large multitiered, multistate models in which the voltage sensors and three (or more) different types of Ca2+ sensors function relatively independently of one another to facilitate the opening/closing transitions. While such models with assumptions of independence among the sensors can approximate the data, there is experimental evidence suggesting some interactions among the sensors. Unanswered questions for the kinetic-gating mechanism are the nature and types of interactions. In addition, while it has been shown that the large multitiered, multistate models can account for the single-channel kinetics without an assumption of independence, practically no work has been done to determine whether the large multitiered, multistate models with an assumption of independence can account for the single-channel kinetics.

Given a kinetic model, the next step is to relate the kinetics (function) to structure. The voltage sensor appears to be associated with S4, but few experiments have been done in BK channels (in contrast to other K+ channels) to relate movement of S4 to gating. This is an area in need of attention. A model has been presented for the Ca2+ regulation of a bacterial channel (MthK), but the proposed low affinity Ca2+ binding site in MthK appears to be in a different location in BK, and the high affinity regulatory sites in BK do not appear to be in MthK. While various sites have been found in BK channels, which, when mutated, remove the Ca2+ regulatory systems, and Ca2+ binding has been measured for a proposed high affinity site (the Ca2+ bowl), the gap in information between the proposed sites and the induced conformational changes associated with gating for BK channels is wide indeed. Finally, recent experiments suggest that BK channels may retain high affinity Ca2+-sensitive gating when the entire COOH terminus beyond S6 including all the structures crucial for the proposed Ca2+-dependent gating mechanism of MthK, is removed. More experiments will be required to fully exclude the possible contributions of endogenous proteins to the gating of the truncated channel, to determine if truncating the channel creates an artifactual gating mechanism or isolates a true gating mechanism, and in either case, how the Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms that have been previously localized by mutations to the severed tail domain interact with those in the truncated channel.

As is often the case in the process of scientific discovery, new questions continue to arise somewhat faster than old questions are put to rest. How far is there to go? If the physical, chemical, and biological principles of channels were fully understood, it would be possible to predict directly from the genomic DNA all of the information required to fully understand the structure and function of the BK channel, including: the crystal structure, selectivity, conductance, Po as a function of Ca2+ and voltage, all the various conformational states and their lifetimes, the rate constants for all the transitions among the various states, and, of course, the detailed single-channel kinetics for all possible experimental conditions. With the need to understand hundreds of different channels and thousands of potential splice variants, and also the actions of multiple accessory subunits, it will be essential to have the tools to calculate structure and function, so it is not necessary to spend decades of experimental work characterizing each of the separate channel types and their individual mechanisms. This can be a goal to be completed before the end of the twenty-first century, with the current research contributing the essential scientific underpinning necessary to develop such a quantitative approach.

Acknowledgments

I thank Xiang Qian for help with the figures.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health AR32805 and the Florida Department of Health, Biomedical Research Program.

References

- Adelman, J.P., K.Z. Shen, M.P. Kavanaugh, R.A. Warren, Y.N. Wu, A. Lagrutta, C.T. Bond, and R.A. North. 1992. Calcium-activated potassium channels expressed from cloned complementary DNAs. Neuron. 9:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, S.K., and R. MacKinnon. 1996. Contribution of the S4 segment to gating charge in the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 16:1169–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao, L., A.M. Rapin, E.C. Holmstrand, and D.H. Cox. 2002. Elimination of the BK(Ca) channel's high-affinity Ca2+ sensitivity. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:173–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, J.N., K.L. Magleby, and B.S. Pallotta. 1982. Properties of single calcium-activated potassium channels in cultured rat muscle. J. Physiol. 331:211–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla, F. 2000. The voltage sensor in voltage-dependent ion channels. Physiol. Rev. 80:555–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian, S., I. Favre, and E. Moczydlowski. 2001. Ca2+-binding activity of a COOH-terminal fragment of the Drosophila BK channel involved in Ca2+-dependent activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:4776–4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, A.F., and L. Sy. 2001. Contribution of potential EF hand motifs to the calcium-dependent gating of a mouse brain large conductance, calcium-sensitive K+ channel. J. Physiol. 533:681–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, R., G.J. Perez, A.D. Bonev, D.M. Eckman, J.C. Kosek, S.W. Wiler, A.J. Patterson, M.T. Nelson, and R.W. Aldrich. 2000. Vasoregulation by the beta1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature. 407:870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, A., S. Tsunoda, D.P. McCobb, A. Wei, and L. Salkoff. 1993. mSlo, a complex mouse gene encoding “maxi” calcium-activated potassium channels. Science. 261:221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, A., A. Wei, and L. Salkoff. 1990. Shal, Shab, and Shaw: three genes encoding potassium channels in Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:2173–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, D., and A.G. Hawkes. 1981. On the stochastic properties of single ion channels. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 211:205–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, D., and A.G. Hawkes. 1987. A note on correlations in single ion channel records. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 230:15–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.H., and R.W. Aldrich. 2000. Role of the beta1 subunit in large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel gating energetics. Mechanisms of enhanced Ca2+ sensitivity. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:411–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.H., J. Cui, and R.W. Aldrich. 1997. Allosteric gating of a large conductance Ca-activated K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 110:257–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J., and R.W. Aldrich. 2000. Allosteric linkage between voltage and Ca2+-dependent activation of BK-type mslo1 K+ channels. Biochemistry. 39:15612–15619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, L., P. Meera, J. Amigo, E. Stefani, O. Alvarez, L. Toro, and R. Latorre. 1998. Role of the S4 segment in a voltage-dependent calcium-sensitive potassium (hSlo) channel. J. Biol. Chem. 273:32430–32436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen, M. 1968. New looks and outlooks on physical enzymology. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1:3–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, W.B., O.B. McManus, and K.L. Magleby. 1993. Opening and closing transitions for BK channels often occur in two steps via sojourns through a brief lifetime subconductance state. Biophys. J. 65:702–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht, A. 1984. Enzyme Structure and Mechanism. W. H. Freeman and Co., New York.

- Fredkin, D.R., M. Montal, and J.A. Rice. 1985. Identification of aggregated Markovian models: application to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. In Proceedings of the Berkeley Conference in Honor of Jerzy Neyman and Jack Kiefer. L.M. LeCam and R.A. Olshen, editors. Wadsworth Press, Belmont. 269–289.

- Fu, J., H.L. Ji, A.P. Naren, and K.L. Kirk. 2001. A cluster of negative charges at the amino terminal tail of CFTR regulates ATP-dependent channel gating. J. Physiol. 536:459–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, C., E. Rosenman, F. Bezanilla, O. Alvarez, and R. Latorre. 2001. Periodic perturbations in Shaker K+ channel gating kinetics by deletions in the S3-S4 linker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:9617–9623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn, R. 2002. Coupled movements in voltage-gated channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:449–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan, F.T., and R.W. Aldrich. 1999. Allosteric voltage gating of potassium channels II. Mslo channel gating charge movement in the absence of Ca2+. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:305–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan, F.T., and R.W. Aldrich. 2002. Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel opening in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:267–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan, F.T., J. Cui, and R.W. Aldrich. 1999. Allosteric voltage gating of potassium channels I. Mslo ionic currents in the absence of Ca2+. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:277–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isacoff, E., D. Papazian, L. Timpe, Y.N. Jan, and L.Y. Jan. 1990. Molecular studies of voltage-gated potassium channels. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 55:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., A. Lee, J. Chen, M. Cadene, B.T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2002. a. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 417:515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., A. Lee, J. Chen, M. Cadene, B.T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2002. b. The open pore conformation of potassium channels. Nature. 417:523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., A. Pico, M. Cadene, B.T. Chait, and R. MacKinnon. 2001. Structure of the RCK domain from the E. coli K+ channel and demonstration of its presence in the human BK channel. Neuron. 29:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.W. 1999. Commentary: a plausible model. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorowski, G.J., H.G. Knaus, R.J. Leonard, O.B. McManus, and M.L. Garcia. 1996. High-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels; structure, pharmacology, and function. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 28:255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, R., C. Vergara, and C. Hidalgo. 1982. Reconstitution in planar lipid bilayers of a Ca2+-dependent K+ channel from transverse tubule membranes isolated from rabbit skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:805–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingle, C.J. 2002. Setting the stage for molecular dissection of the regulatory components of BK channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby, K.L. 2001. Kinetic gating mechanisms for BK channels: when complexity leads to simplicity. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:583–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby, K.L., and B.S. Rothberg. 2001. Cooperative allosteric gating for voltage- and Ca2+-activation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels. Biophys. J. 80:222a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks, T.N., and S.W. Jones. 1992. Calcium currents in the A7r5 smooth muscle-derived cell line. An allosteric model for calcium channel activation and dihydropyridine agonist action. J. Gen. Physiol. 99:367–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty, A. 1981. Ca-dependent K channels with large unitary conductance in chromaffin cell membranes. Nature. 291:497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, K., W.J. Joiner, and S.H. Heinemann. 1994. A characterization of the activating structural rearrangements in voltage-dependent Shaker K+ channels. Neuron. 12:301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, O.B. 1991. Calcium-activated potassium channels: regulation by calcium. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 23:537–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, O.B., A.L. Blatz, and K.L. Magleby. 1985. Inverse relationship of the durations of adjacent open and shut intervals for C1 and K channels. Nature. 317:625–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, O.B., and K.L. Magleby. 1988. Kinetic states and modes of single large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in cultured rat skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 402:79–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, O.B., and K.L. Magleby. 1989. Kinetic time constants independent of previous single-channel activity suggest Markov gating for a large conductance Ca-activated K channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 94:1037–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, O.B., and K.L. Magleby. 1991. Accounting for the Ca2+-dependent kinetics of single large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in rat skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 443:739–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meera, P., M. Wallner, M. Song, and L. Toro. 1997. Large conductance voltage- and calcium-dependent K+ channel, a distinct member of voltage-dependent ion channels with seven N-terminal transmembrane segments (S0-S6), an extracellular N terminus, and an intracellular (S9-S10) C terminus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:14066–14071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monod, J., J. Wyman, and J.P. Changeux. 1965. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 12:88–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, B.L., and K.L. Magleby. 2001. Gating and conductance properties of BK channels are modulated by the S9-S10 tail domain of the alpha subunit. A study of mSlo1 and mSlo3 wild-type and chimeric channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:711–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, G.W., J. Marshall, and E. Moczydlowski. 1996. Hypothesis for a serine proteinase-like domain at the COOH terminus of Slowpoke calcium-activated potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 108:473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimigean, C.M., and K.L. Magleby. 2000. Functional coupling of the beta(1) subunit to the large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in the absence of Ca2+. Increased Ca2+ sensitivity from a Ca2+-independent mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 115:719–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu, X., and K.L. Magleby. 2001. Single-channel data obtained at the extremes of voltage and calcium place restrictions on the gating mechanism for BK channels. Biophys. J. 80:222a. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, X., and K.L. Magleby. 2002. Stepwise contribution of each subunit to the cooperative activation of BK channels by Ca2+. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:11441–11446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallotta, B.S., K.L. Magleby, and J.N. Barrett. 1981. Single channel recordings of Ca2+-activated K+ currents in rat muscle cell culture. Nature. 293:471–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazian, D.M., T.L. Schwarz, B.L. Tempel, Y.N. Jan, and L.Y. Jan. 1987. Cloning of genomic and complementary DNA from Shaker, a putative potassium channel gene from Drosophila. Science. 237:749–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozo, E., L. Santacruz-Toloza, E. Stefani, F. Bezanilla, and D.M. Papazian. 1994. S4 mutations alter gating currents of Shaker K channels. Biophys. J. 66:345–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskorowski, R., and R. Aldrich. 2002. Calciuim activation of BKca potassium channels lacking calcium bowl and RCK domains. Nature. 420:499–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan, K., T.H. Michael, G.J. Jiang, H. Hiel, and P.A. Fuchs. 1999. A molecular mechanism for electrical tuning of cochlear hair cells. Science. 283:215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios, E., M. Karhanek, J. Ma, and A. Gonzalez. 1993. An allosteric model of the molecular interactions of excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 102:449–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille, R., M.L. Garcia, G.J. Kaczorowski, and M.P. Charlton. 1993. Functional colocalization of calcium and calcium-gated potassium channels in control of transmitter release. Neuron. 11:645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, B.S., and K.L. Magleby. 1998. Kinetic structure of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels suggests that the gating includes transitions through intermediate or secondary states. A mechanism for flickers. J. Gen. Physiol. 111:751–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, B.S., and K.L. Magleby. 1999. Gating kinetics of single large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in high Ca2+ suggest a two-tiered allosteric gating mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:93–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, B.S., and K.L. Magleby. 2000. Voltage and Ca2+ activation of single large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels described by a two-tiered allosteric gating mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:75–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, M., and L. Salkoff. 1997. A novel calcium-sensing domain in the BK channel. Biophys. J. 73:1355–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, M., A. Wei, A. Yuan, J. Gaut, M. Saito, and L. Salkoff. 1998. Slo3, a novel pH-sensitive K+ channel from mammalian spermatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273:3509–3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, M., A. Yuan, and L. Salkoff. 1999. Transplantable sites confer calcium sensitivity to BK channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2:416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoh, S.A., D. Sigg, D.M. Papazian, and F. Bezanilla. 1996. Voltage-sensing residues in the S2 and S4 segments of the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 16:1159–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, K.Z., A. Lagrutta, N.W. Davies, N.B. Standen, J.P. Adelman, and R.A. North. 1994. Tetraethylammonium block of Slowpoke calcium-activated potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes: evidence for tetrameric channel formation. Pflugers Arch. 426:440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J., and J. Cui. 2001. Intracellular Mg2+ enhances the function of BK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 118:589–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J., G. Krishnamoorthy, Y. Yang, L. Hu, N. Chaturvedi, D. Harilal, J. Qin, and J. Cui. 2002. Mechanism of magnesium activation of calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 418:876–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani, E., M. Ottolia, F. Noceti, R. Olcese, M. Wallner, R. Latorre, and L. Toro. 1997. Voltage-controlled gating in a large conductance Ca2+-sensitive K+ channel (hslo). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:5427–5431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talukder, G., and R.W. Aldrich. 2000. Complex voltage-dependent behavior of single unliganded calcium-sensitive potassium channels. Biophys. J. 78:761–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.W., O. Saifee, M.L. Nonet, and L. Salkoff. 2001. SLO-1 potassium channels control quantal content of neurotransmitter release at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 32:867–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, A., M. Covarrubias, A. Butler, K. Baker, M. Pak, and L. Salkoff. 1990. K+ current diversity is produced by an extended gene family conserved in Drosophila and mouse. Science. 248:599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, A., C. Solaro, C. Lingle, and L. Salkoff. 1994. Calcium sensitivity of BK-type KCa channels determined by a separable domain. Neuron. 13:671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.C., J.J. Art, M.B. Goodman, and R. Fettiplace. 1995. A kinetic description of the calcium-activated potassium channel and its application to electrical tuning of hair cells. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 63:131–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]