Abstract

We show that, from the earliest morphologically recognisable stages of development, mouse skin papillomas induced by a chemical initiation-promotion regime are polyclonal. We have demonstrated polyclonality directly by immunohistochemical staining of the mosaic cell populations in embryo aggregation chimaeras, a method which removes some of the uncertainties of previous conclusions based on analysis using electrophoretic polymorphisms. The findings may imply that initiation within a single cell and promotion of its clonal descendents is not a sufficient explanation for the origin of these tumours and that interaction between cells of more than one clone is involved.

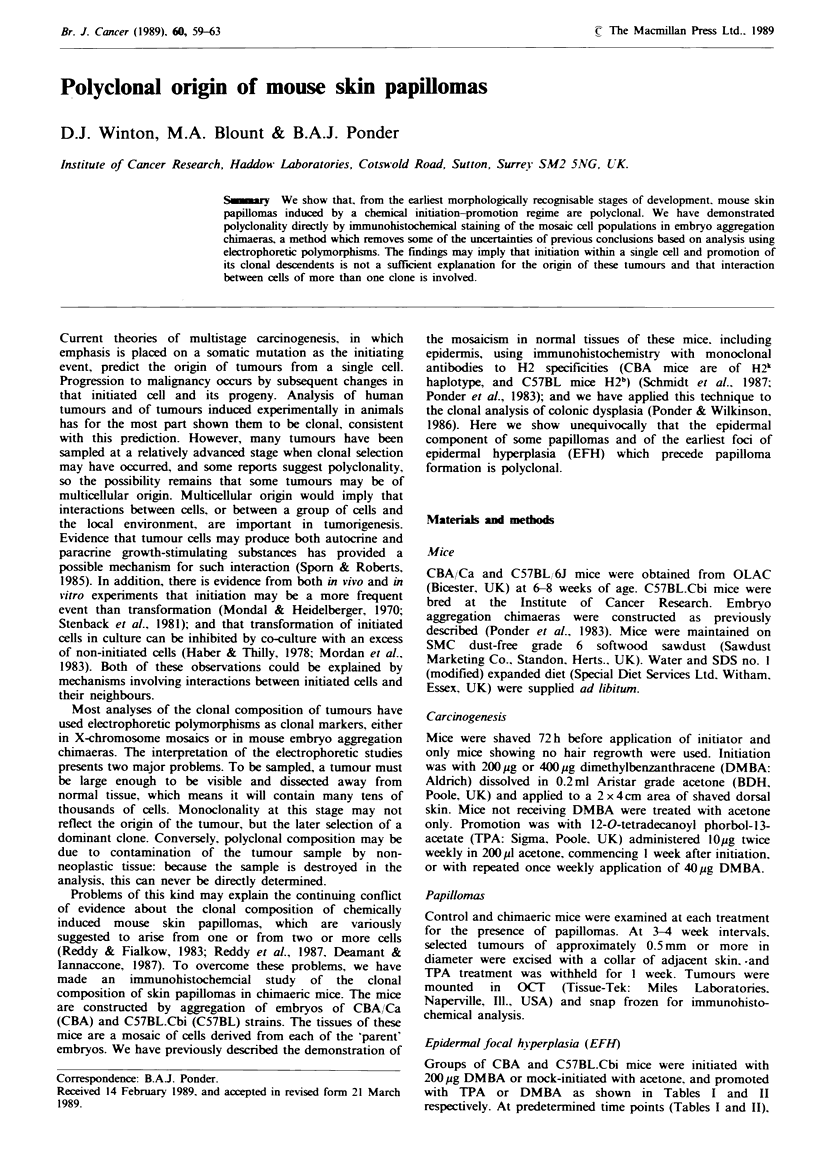

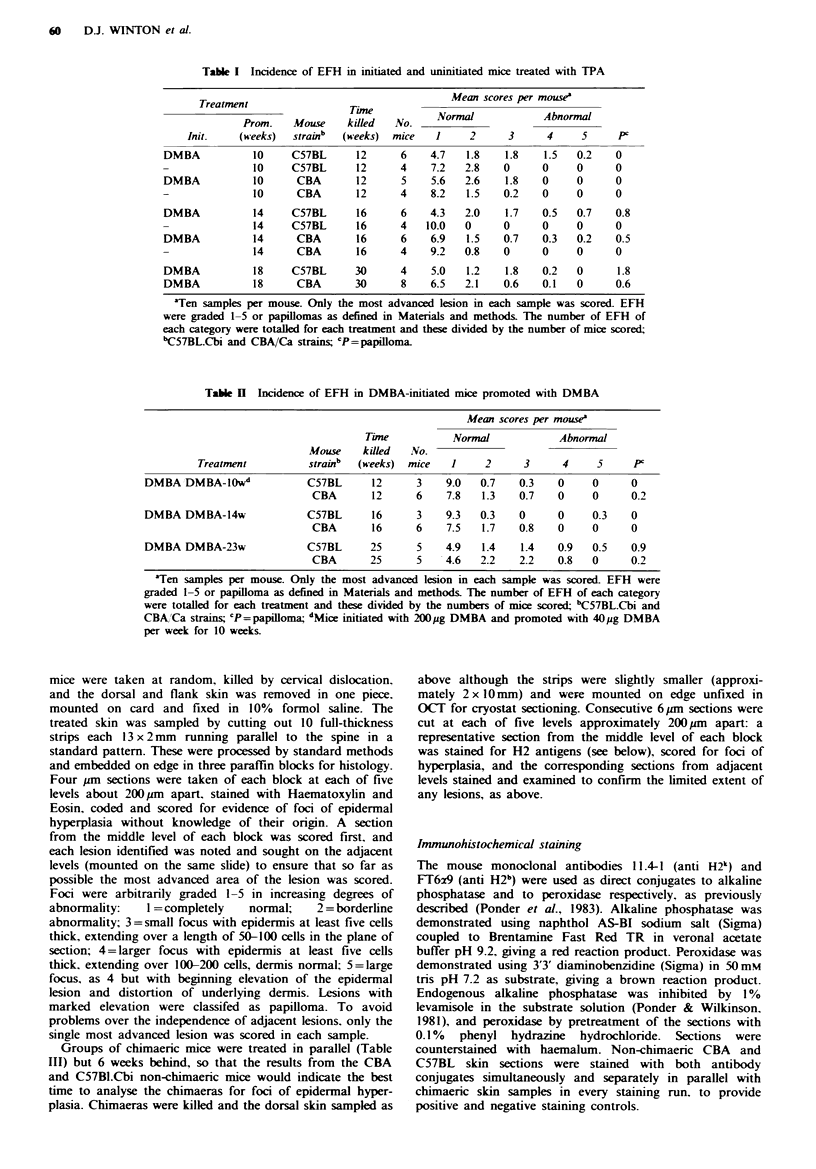

Full text

PDF

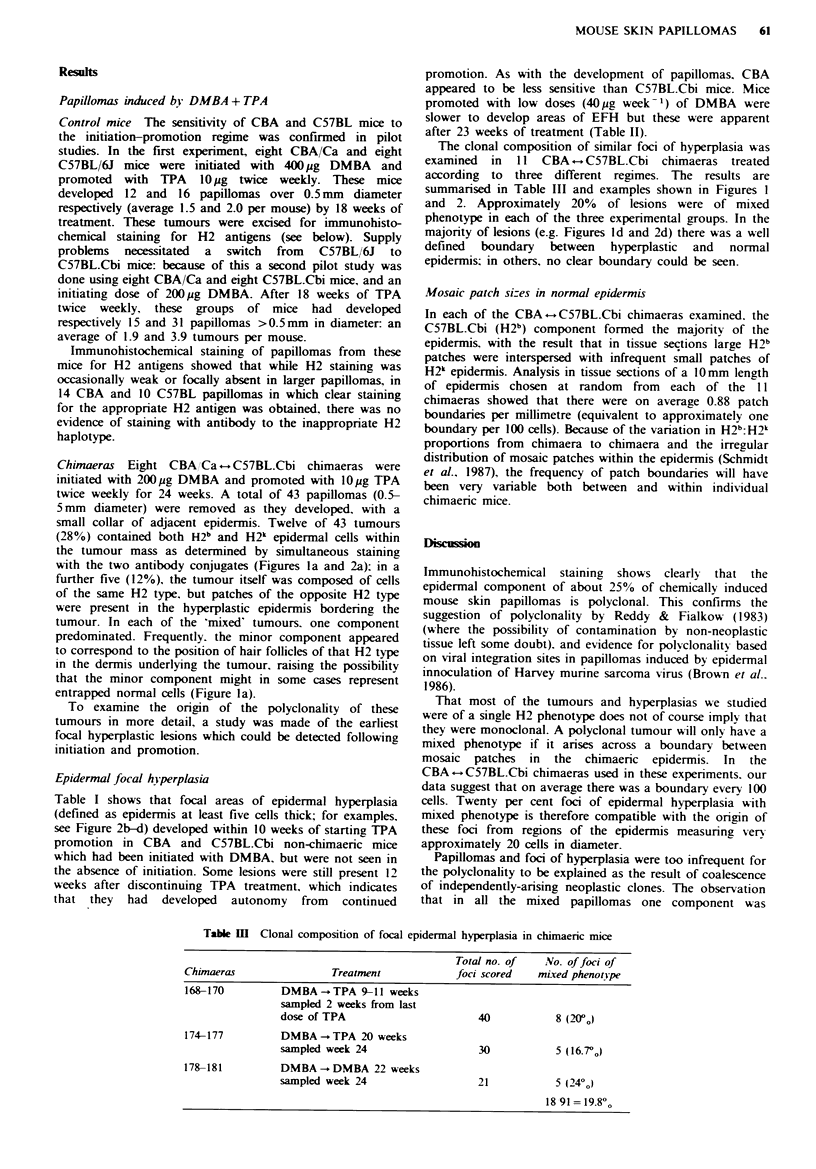

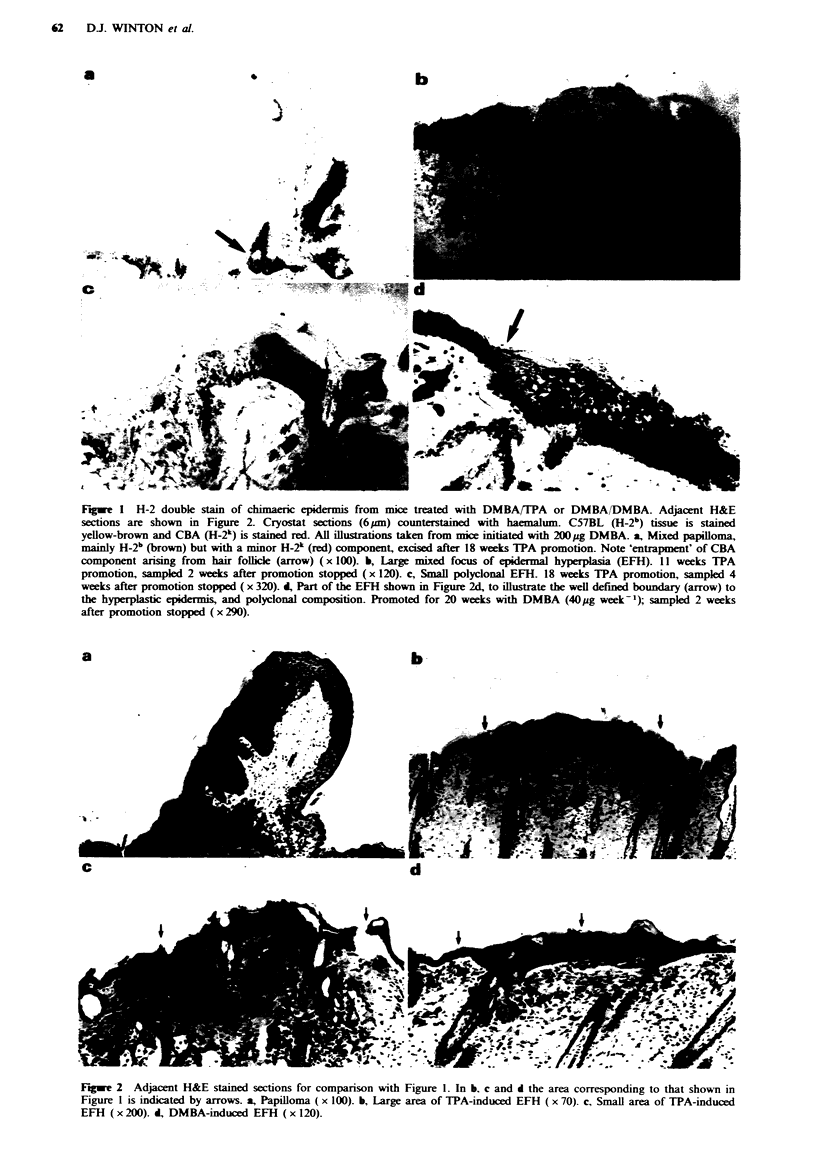

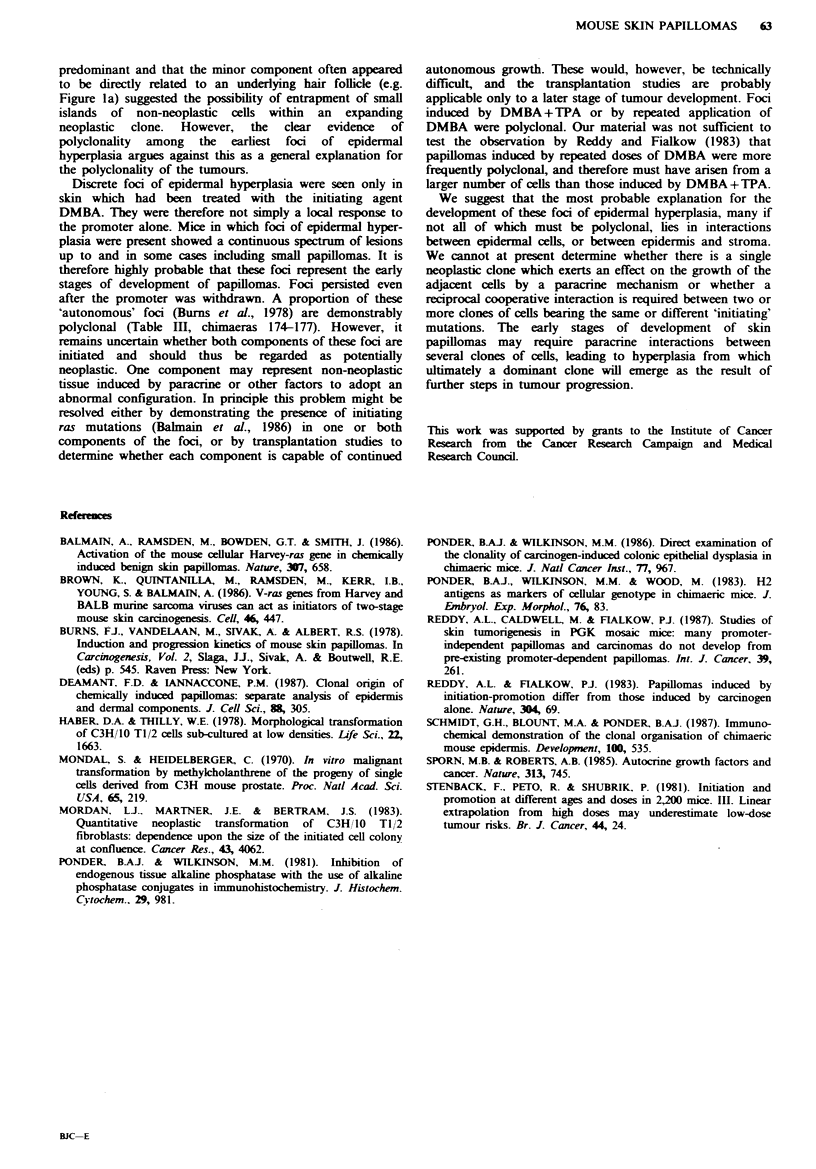

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Balmain A., Ramsden M., Bowden G. T., Smith J. Activation of the mouse cellular Harvey-ras gene in chemically induced benign skin papillomas. Nature. 1984 Feb 16;307(5952):658–660. doi: 10.1038/307658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K., Quintanilla M., Ramsden M., Kerr I. B., Young S., Balmain A. v-ras genes from Harvey and BALB murine sarcoma viruses can act as initiators of two-stage mouse skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 1986 Aug 1;46(3):447–456. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90665-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deamant F. D., Iannaccone P. M. Clonal origin of chemically induced papillomas: separate analysis of epidermal and dermal components. J Cell Sci. 1987 Oct;88(Pt 3):305–312. doi: 10.1242/jcs.88.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber D. A., Thilly W. G. Morphological transformation of C3H/10T1/2 cells subcultured at low cell densities. Life Sci. 1978 May 8;22(18):1663–1673. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S., Heidelberger C. In vitro malignant transformation by methylcholanthrene of the progeny of single cells derived from C3H mouse prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970 Jan;65(1):219–225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.65.1.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordan L. J., Martner J. E., Bertram J. S. Quantitative neoplastic transformation of C3H/10T1/2 fibroblasts: dependence upon the size of the initiated cell colony at confluence. Cancer Res. 1983 Sep;43(9):4062–4067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder B. A., Wilkinson M. M. Inhibition of endogenous tissue alkaline phosphatase with the use of alkaline phosphatase conjugates in immunohistochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1981 Aug;29(8):981–984. doi: 10.1177/29.8.7024402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy A. L., Caldwell M., Fialkow P. J. Studies of skin tumorigenesis in PGK mosaic mice: many promoter-independent papillomas and carcinomas do not develop from pre-existing promoter-dependent papillomas. Int J Cancer. 1987 Feb 15;39(2):261–265. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910390223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt G. H., Blount M. A., Ponder B. A. Immunochemical demonstration of the clonal organization of chimaeric mouse epidermis. Development. 1987 Jul;100(3):535–541. doi: 10.1242/dev.100.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn M. B., Roberts A. B. Autocrine growth factors and cancer. 1985 Feb 28-Mar 6Nature. 313(6005):745–747. doi: 10.1038/313745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenbäck F., Peto R., Shubik P. Initiation and promotion at different ages and doses in 2200 mice. III. Linear extrapolation from high doses may underestimate low-dose tumour risks. Br J Cancer. 1981 Jul;44(1):24–34. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1981.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]