Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, has few clinical similarities to HIV-1-associated dementia (HAD). However, genes were identified related among these dementias. Discovering correlations between gene function, expression, and structure in the human genome continues to aid in understanding the similarities between pathogenesis of these two dementing disorders. The current work attempts to identify relationships between these dementias in spite of their clinical differences, based on genomic structure, function, and expression. In this comparative study, the NCBI Entrez Genome Database is used to detect these relationships. This approach serves as a model for future diagnosis and treatment in the clinical arena as well as suggesting parallel pathways of disease mechanisms. Identifying a correlation among expression, structure, and function of genes involved in pathogenesis of these dementing disorders, may assist to understand better their interaction with each other and the human genome.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease (AD), HIV associated dementia (HAD), gene function, expression, structure, human genome

Background

It is well known that clinically, Alzheimer's disease (AD) and HIV-1-associated dementia (HAD) are distinct incurable dementing disorders [1].For the present study we hypothesized that there is a correlation between expression and structure/function of some genes for AD with HAD.

AD is the most common form of dementia in the elderly population. The Alzheimer's association defines its warning signs as follows: memory loss, disorientation to time and place, poor or decreased judgment, misplacing objects, difficulty with performing familiar tasks as well as language and abstract thinking, and changes in mood, behavior, and personality, as well as loss of initiative [2].

Genetic factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD. Khachaturian and colleagues [3] summarized that amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin I (PSEN1), presenilin II (PSEN2) and apolipoprotein-E (APOE) alleles are directly related to AD (Table 1 in supplementary material) and characterized them according to the different types of AD. APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 are associated with patients of early-onset AD, while apolipoprotein-E with those patients of late-onset AD (Table 1 in supplementary material). Familial or early onset AD develops from the age of 40 up to 60 or 65 years and less than 10% of AD cases are of this type [4]. The other form of AD, sporadic or late-onset, is characterized by its abrupt development after the age of 60 to 65 and it is most frequently found in AD patients [4].

Unlike neurological diseases such as muscular dystrophy and Huntington's disease, AD is not caused by mutations in a single gene, but rather the mutations of genes found on multiple chromosomes, when familial. Most cases of AD are sporadic and genetic cause has not been established. However, mechanisms appear to operate that associate the actions of genes involved in familial disease [1]. Possibly what is termed Alzheimer's disease may actually compose sub-components with different pathogenesis, sharing similar clinical features. Those clinical features involve insidious and progressive impairment in forming new memories, accompanied by varying degrees of deficit in visuospatial functioning, confrontation naming, problems solving and other cognitive areas that are accompanied by a gradual loss of independent functioning [5]

Selkoe developed mechanisms for AD [6]. Pathogenesis of AD involves protein aggregation, termed neuritic plaques that mainly consist of the Aβ peptide. Aβ is a neurotoxic peptide that is coupled with plaque and tangle formation, eventually leading to neuron death (Figure 1a) [6]. Aβ is derived from proteolytic processed amyloid precursor protein gene (APP) [7]. The APP gene is located on chromosome 21 and mutations in this gene have been associated with AD [6]. The amyloid cascade hypothesis states that altered APP metabolism involving a reduction in sAPPα and increased levels of Aβ (processed into several related oligopeptides), is a common feature of AD [6].

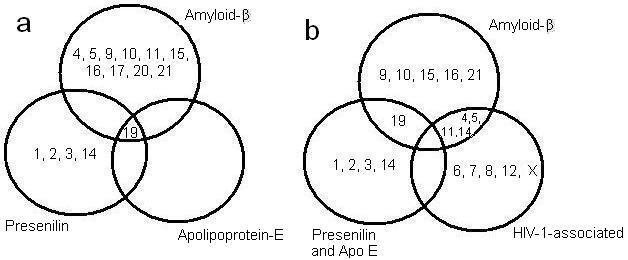

Figure 1.

(a) Venn diagram that demonstrates the chromosomal relationship found with the human genes associated with all the AD related genes found. The Aβ related genes found on the chromosomes represented in diagram, as well as those of presenilin, and Apolipoprotein-E. (b) Venn diagram that demonstrates the chromosomal relationship found with the human genes associated with the AD related genes and those of HIV-1-associated genes. The Aβ related genes were on the chromosomes represented in diagram, as well as those of presenilin, ApoE, and HIV-1 associated genes.

Verdile and colleagues [8] found a relationship between presenilins (PSEN) and their role in generation of Aβ. Mutations in PSEN1 and PSEN2 account for most autosomal dominant early-onset familial forms of AD. Verdile and colleagues stressed presenilin's vital role in the production of the Aβ protein that is found to accumulate in the brain of AD patients. It was previously shown by Khachaturian and colleagues [3] that intramembranous presenilin enzymes cleave the C-terminal fragment of APP resulting in Aβ release [8]. Consequently, it has been speculated by Popescu and colleagues [9] that PSEN1 and PSEN2 have a regulatory role in apoptosis of cells from patients with AD. Another protein, apolipoprotein-E, is associated with late-onset AD [10]. With three isoforms of the Apo-E gene, Apo-E2, -E3, and -E4, [11] Apo-E is found to be associated with AD. However, even with the discovery of these three AD-associated genes, recent studies suggest that they constitute less than 30% of the genetic variance (or the phenotypic variance found in a population of various genotypes) for AD and that, additional genetic factors remain to be identified [12].

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) enters the CNS during the early stages of HIV infection. HIV-associated dementia (HAD) consists of a progressive encephalopathy that results from impairment of normal CNS function by HIV-1 related injury. The symptoms that characterize HAD are broadly separated in categories that are termed: cognitive, motor, and behavioral as previously reviewed [13]. The cognitive related category of symptoms traditionally resembled subcortical dementias, and included difficulties with concentrating, memory retrieval eventual degradation of all mental functions as the dementia progressed. However, evidence indicates that in the post-HAART era, cognitive deficits are now including deficits in learning and complex attention [14]. The motor associated symptoms include poor coordination, weakness in legs, inability to maintain balance, lack of grip in hands, decline in clarity of handwriting, loss of bladder or bowel control. The behavioral related symptoms include changes in personality such as increased irritability, apathy, loss of initiative and withdrawal from social contact. Other behavioral symptoms include depression, excitability, emotional outbursts, impaired judgment, and, on occasion, symptoms of psychosis (hallucinations, paranoia, disorientation, sudden rages) [13]. However, a syndrome characterized by lesser degrees of cognitive and motor deficit and less impairment in day-to-day functioning is termed HIV-associated minor cognitive motor disorder (MCMD).

Neuropathogenesis of HAD involves infection of macrophage/microglia and astrocytes. Neurons are rarely infected directly by HIV-1 [13]. These cells produce toxins that initiate a series of biochemical reactions and signaling pathways that instruct neurons to commence apoptosis, leading to HAD. [15]. The macrophages and microglia also produce chemokines and cytokines that, in turn, affect neurons and other brain cells (e.g., astrocytes) [16]. The affected astrocytes that normally nurture and protect neurons, participate in the destruction of the healthy neurons [15].

Oxidative stress is another component of neuropathogenesis in neuropsychiatric disease [16]. One of many studies demonstrated that infected astrocytes produce highly toxic peroxynitrite from superoxide and nitric oxide radicals. Smith and colleagues [17] examined whether peroxynitrite is involved in Alzheimer's disease, and found the oxidative factor to result in carbonyl formation of macromolecules that, in turn, indicated peroxynitrite involvement. Smith's findings provide strong evidence that peroxynitrite is involved in the oxidative damage of Alzheimer's disease that is also found in HAD, in spite of its clinical differences. In addition, it is to be noted that Kuljis and colleagues [18] demonstrated that there was up to a 40-fold increase in the expression of the neuronal nitric oxide synthase in neurons associated with drug abuse and HIV infection.

The expression of several dementia-related genes may be similar in both AD and HAD despite the clinical differences of these two diseases as well as their non-viral and viral causes, respectively. It is thus a counter-intuitive hypothesis to implicate possible relationships between gene interactions on the same chromosomes. Moreover, along this reasoning, human genes related to HIV genes, interactively, may regulate the dementias. The HIV-1 Rev protein [19] is one of the HIV's regulator genes that stimulates the production of HIV proteins, but suppresses the expression of HIV's regulatory genes (Table 6 under supplementary material) [19-20]. This gene is involved in the transport of precursor mRNA from the nucleus into the cytoplasm. A similar sequence related to this protein was found in the human genome. Cullen [19] demonstrated an ancient family of viruses, known as HERV-K (human endogenous retrovirus K), derived from old world monkeys, and is hypothesized to have later evolved in Homo sapiens. According to Cullen, 30-50 copies of HERV-K exist in the human genome, and some of the copies appear to be transcriptionally active at low levels in normal testicular and placental tissue. Most importantly, Cullen and colleagues determined that the HERV-K viral protein, K-Rev, functions in a manner similar to the HIV Rev protein [19] in its ability to transport precursor mRNA to the cytoplasm of the host cell. The study provides evidence for the appearance of HIV-1-like interacting genes in the human genome.

Methodology

Using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website, data was obtained and organized to examine the genetic comparison between AD and NeuroAIDS (Table 2 see supplementary material). This tool was the main “instrument” used in the preparation of this comparative study. Additional databases were also used. The databases found in Entrez Genome, and on the NCBI websites were utilized and the following human genes located: amyloid β, presenilin, Apolipoprotein, and HIV-1 associated genes. After conducting the individual searches, a comparison of similar chromosomal locales was made and presented in a Venn diagram (Figure 1b). The same chromosomal comparison was conducted for AD related genes and presented in another Venn diagram (Figure 1a). In addition to location comparison, the genes' functions associated with AD were compared to those associated with HIV-1-interacting proteins. Using the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) link (Table 2 under supplementary material) the functions of the available genes were obtained, and compared to those found in the same chromosomes associated with both dementias as well as those found in different locales.

Hypothesis

This study targets three areas (gene structure, function, and expression) and explores genetic relationship between the AD and HIV-1 disease without ignoring the differences in pathology. We hypothesize that in spite of the differences between the clinical presentations of AD and HAD, there may be similarities in the dementia-associated gene structure, function, and expression and HIV-1-related genes. As a corollary hypothesis, we further postulate that there are functionally related groups of genes involved in each dementia. The dementia-associated genes previously mentioned for AD and HIV-1 have a series of functions that are not restricted to these specific dementias [16-21]. In addition, the association found between HIV-1-disease and AD, based on the peroxynitrite and the Rev-like sequence found in the human genome are both examples that support this hypothesis. Moreover, a further corollary to these hypotheses is that dementia-associated genes are in located in propinquity with one another on the chromosomes in the human genome. This may relate to chromatin structural changes and modifications that may occur when these genes undergo changes in genes expression [22].

Results

The NCBI's database (including GeneBank and OMIM) provided information regarding the position of those genes linked with the dementias in order to determine whether they have similar chromosomal positions. Some genes have similar positions. The first comparison examined the AD related genes only, and found that these were mostly different from one another in location. For example, the Amyloid β associated genes were on chromosomes different from those of Apolipoprotein and presenilin (Figure 1a). These Aβ and Aβ-related genes were found on chromosomes 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 15, 16, 17, 20 and 21 (Figure 1a). The greatest association was discovered between the following genes: APBA3 (related to Aβ), APOE (related to Apolipoprotein), and PEN2 (related to presenilin). These genes were all located in chromosome 19 and in propinquity, as shown in Table 3 in supplementary material.

The second comparison conducted for each AD gene compared them with those found related to HIV-1-associated genes. Amyloid β had genes related to HIV-1-associated genes on more than one chromosomal location. These locations were found on chromosomes 4, 5, 11 and 17 (Table 4 in supplementary material). Presenilin genes also shared chromosomal locations with HIV-1-related genes on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, and 14 (Table 5, see supplementary material).

However, it is important to note that there was a disparity discovered with Apolipoprotein E, as it was on chromosome 19, and had no loci relationships with the genes found linked with HIV-1-related genes. In addition, other genes found on chromosomes 6, 7, 8, 12, and 22, the X chromosome are HIV-1-interacting but had no shared chromosomal loci with AD-related genes (Table 6 in supplementary material). It is important to note also that there was no HIV-1 related gene found on the 23rd or Y chromosome. A possible target of research is to explore further the hereditary capabilities and molecular biology of these genes.

Discussion

This study describes and compares similar genes found related to AD vs. those related to HIV-1-associated disease at the level of structure, expression, and function. Specifically, genes linked with amyloid-β, presenilin and Apolipoprotein-E were compared to those found with HIV-1-related genes. Our study resulted in 19 genes related to each dementia as shown in Table 4 and Table 5 (tables in supplementary material). The amyloid precursor protein (APP) is closely linked to AD and previously reported, by Khachaturian and colleagues [3] found on chromosome 21. APP is characterized as the cerebral amyloid protein that forms the plaque core in Alzheimer's disease [23]. Although the chromosomal location of APP is not shared with any other gene associated to HIV-1, binding proteins that interact with APP are found to share this chromosome location with some of HIV-1 related genes (Table 3, see supplementary material). The cytoplasmic domain of APP binds to four human phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) proteins. With use of the yeast 2-hybrid screening applied to human brain, McLoughlin and Miller [24] discovered three of the four PTB to be amyloid beta precursor protein-binding, family B1 (APBB1), amyloid beta precursor protein-binding, family B2 (APBB2), and amyloid-beta precursor protein (cytoplasmic tail) binding protein 2 (APBA2) located on chromosomes 11, 4, and 15 respectably [24].

The HIV-1 interacting gene, HIV-1 induced protein HIN-1 (HSHIN1), was found in position 4q31.21 with close chromosomal location to the PTB, APBB2 (Table 2 under supplementary material). Although its function has not been discovered, HSIN1 is a binding protein and some studies indicate that two alternatively spliced transcript variants encoding distinct isoforms have been found only in HIV-1 infected cells [19]. Its chromosome partner, APBB2 is a Fe65-like protein, and is interrelated with a region of another amyloid precursor protein, amyloid beta (A4) precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2) found in chromosome 11 (Table 4 see supplementary material) with a shared chromosome location of another gene linked to HIV-1 [25].

The deduced polypeptide of APLP2 contains a segment with high homology to the transmembrane-cytoplasmic domains of the A4 amyloid protein found in brain plaques of Alzheimer disease patients [26-27]. The other PTB found in chromosome 11, is APBB1 with an alternative name of Fe65 [28]. It contains 14 exons ranging in size from 6 to 735 bp [28]. Human Fe65 was discovered by Cao and Sudhof to be linked to the cytoplasmic tail of APP, and was found to form a multimeric complex with Fe65 as a nuclear adaptor protein [29]. A Fe65 like protein, APBB3 (Fe65-Like2) found in chromosome 5 showed binding capabilities to the intracellular domain of the Alzheimer disease amyloid precursor protein, both in vitro and in vivo [7]. The gene structure was determined by Tanahashi and Tabira [30] and this gene contained 13 exons, distributed over 6 kilodaltons (kD).

The HIV-1 associated genes also located on chromosome 11 are HIV-1 Tat interactive protein (HTATIP) and HIV-1 Tat interactive protein 2 (HTATIP2) (Table 4, shown in supplementary material). With the use of affinity chromatography and the human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) Tat protein, Xiao and colleagues [31] identified two Tat-interacting proteins, TIP30 (HTATIP2) and TIP56. Co-expression of TIP30 specifically enhanced transcription of Tat, the regulatory gene found related to the acceleration in the production of more HIV virus in transfected cells [20-31-32]. Their results not only identified TIP30 as one of the Tat-interacting proteins, but also as a specific coactivator that may enhance formation of a Tat-RNA polymerase II holoenzyme complex ex vivo and in vitro [32]. HTATIP that the authors called TIP60 (Tat-interactive protein, 60-kD) is a gene with close relationship to APP. Cao and Sudhof [29] demonstrated that the cytoplasmic tail of APP forms a multimeric complex with the adaptor protein Fe65 (APBB2) and the histone acetyl-transferase Tip60 (HTATIP). This complex potently stimulates transcription, suggesting that release of the cytoplasmic tail of APP by gamma-cleavage may function in gene expression [29].

Zheng and colleagues [27] isolated a cDNA encoding amyloid beta precursor protein-binding protein-2 (APPBP2) that is also called PAT1 (protein interacting with APP tail-1) and mapped it to chromosome 17 [33]. APPBP2 is a deduced 585-amino acid hydrophilic protein, identical to the uncharacterized KIAA0228 protein identified by Nagase and colleagues [33].It also lacks signal or transmembrane sequences, but contains N- and C-terminal, a coiled domain, several protein kinase C phosphorylation sites, and 4 imperfect C-terminal tandem repeats. Several binding analysis determined that APPBP2 binds specifically to the tyrosine-containing APP-BaSS, and if a mutation of the tyrosine occurs, it will result in nonpolarized transport of APP. The same study also indicated that APPBP2 does not bind to the mutant APP-BaSS. Immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated APPBP2 present in the Golgi region and overlaps the distribution of APP [25]. Along with its other functions, SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting showed that APPBP2 interacts with microtubules and is functionally associated with APP transport and processing [33]. On the same chromosome 17, the HIV-1 associated gene CCL5 is found [34]. CCL5 that was designated as Regulated upon Activation, Normally T-Expressed, and presumably Secreted (RANTES), encodes a T cell-specific molecule [35]. By analysis of somatic cell hybrids and by in situ hybridization, using the cDNA probe, Donlon and colleagues [36] assigned the RANTES locus to 17q11.2-q12, with a secondary hybridization peak noted in the region 5q31-q34, which may represent the location of other members of the gene family With close proximity to APBB3, (Table 4 given under supplementary material) this second possible RANTES representative may have a genetic correlation with APBB3, whose function and structure was previously mentioned. Cocchi and colleagues [37] who demonstrated that the chemokines RANTES, MIP-1-alpha, and MIP-1-beta are the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells that are involved in the control of HIV infection in vivo. Arenzana-Seisdedos and colleagues [38] investigated a possible therapeutic agent for inhibition of HIV infection as a derivative of RANTES. The derivative, called RANTES (9-68), lacks the first 8 N-terminal amino acids, and has no chemotactic properties for leukocyte activation. This study found that the anti-HIV activity of RANTES and RANTES (9-68) showed some variability depending on the donor cells. The authors concluded that structurally modified chemokines can retain receptor affinity, inhibit HIV infection, though lack activation functions [38].

Bakhiet and colleagues [39] showed that, unlike other chemokines, expression of RANTES mRNA and protein, increases with age, thus producing possible dealings of AD and its pathogenesis. The effects produced by their study were then suppressed by anti-RANTES or anti-RANTES receptor antibodies and were enhanced by recombinant RANTES. Interferon-gamma (IFN-α) is induced by RANTES and is required for RANTES' effects and only 10-week-old astrocytes expressed the IFN-α receptor. Blocking IFN-α with antibody, reversed the effects of RANTES, indicating that cytokine/chemokine networks are critically involved in brain development, thus, creating another possible interaction of AD related genes [39]. Yet another gene relationship was found, with the diminished transcription of RANTES, afforded by a regulatory allele In1.1C, which is consistent with increased HIV-1 spread in vivo. It is this spread of viral infection that leads to the accelerated progression of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) [40]. An, and colleagues [40] observed the influence of four RANTES single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and their haplotypes on HIV-1 infection and AIDS progression. Three of the four (403A in the promoter, In1.1C in the first intron, and 3-prime 222C in the 3-prime UTR) on chromosome 17, were related with increased frequency of HIV-1 infection. This study demonstrated In1.1C-bearing genotypes to account for 37% of the risk for rapid progression among African Americans, thus, a possibly important control of AIDS progression as well, in Africa.

In addition to the Amyloid-β related genes, presenilin was another protein found to share chromosome locations with HIV-1-related genes (Table 5 in supplementary material). The mutations in PSEN1 and PSEN2, account for most of all autosomal dominant early-onset familial AD [8]. These genes have been previously found in chromosomes 14 and 1 respectively [41-42]. By linkage mapping, Sherrington and colleagues [42] defined a region containing the gene for early-onset Alzheimer disease type 3, which had been linked to chromosome 14 and encoded by 10 exons with at least 23 kD [43]. The structural analysis predicted an integral membrane protein with at least 7 transmembrane helical domains that was identified as presenilin 1 (PSEN1) [42]. Presenilins regulate APP processing through their effects on gamma-secretase, an enzyme that cleaves APP [44]. It is this cleavage that, according Scheuner and colleagues [45], that leads to the amyloid plaque formation caused by the mutations in PSEN1. Another role played by PSEN1 is its interaction with Cadherin proteins that Zhang and colleagues [27] showed in their study. They demonstrated that PSEN1 forms a complex with beta-catenin in vivo that increases beta-catenin stability. These PSEN1 mutations reduce its ability to stabilize beta-catenin leading to the increased degradation of beta-catenin in the brains of transgenic mice. The beta-catenin levels are reduced in the brains of Alzheimer disease patients with these mutations. If beta-catenin signaling decreases or is lost, it will increase neuronal vulnerability to apoptosis induced by APP. Thus, mutations in the PSEN1 gene may increase neuronal apoptosis by varying beta-catenin stability, predisposing individuals to early-onset Alzheimer disease [27]. Along with PSEN1, the HIV-1 associated gene, LOC145414, was found with very limited information regarding its structure and function. It is similar to ribosomal protein L3 and HIV TAR binding protein, one that has 403 amino acids. Adams and colleagues [46] isolated the 3-prime region of an L3 cDNA as a human brain EST, and by somatic cell hybrid and radiation hybrid mapping analyses, Kenmochi and colleagues [47] mapped the human L3 gene to chromosome 22. This same similarity was found in other genes located on chromosomes 12 and X (Table 6 in supplementary material).

The PSEN2 gene is located in chromosome 1, and Kovacs and colleagues [48] demonstrated its expression patterns to be very similar to those of PSEN1 in the brain. PSEN2 has been identified to contain 12 exons, with ten coding and two derived from the 5-prime untranslated region [49]. It is also marked as a critical component of PSEN1 and gamma-secretase complexes, and its formation of Amyloid-β. Li and colleagues [50] suggested that PSEN2 and PSEN1 play a role in chromosome organization and segregation. They discussed a pathogenic mechanism for familial AD, in which mutant presenilins cause chromosome mis-segregation during mitosis, resulting in apoptosis. An alternative hypothesis is that mutant presenilins that are not transported out of the endoplasmic reticulum appropriately may interfere with normal APP processing [50]. All possible interactions in the overall pathogenesis of AD can be observed with this interaction. The HIV-1 associated gene located on the same chromosome as PSEN2 is TAR (HIV) RNA binding protein 1 (TARBP1) (Table 5 in supplementary material). This gene has been identified by Wu and colleagues [51] as a 185-kD protein that binds to the loop region of TAR RNA. This region (TAR RNA) is bound by the HIV Tat protein, a transcription-activating protein that activates the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR). The HIV-1 LTR with the HIV genome is integrated into host DNA via the integrase protein and the LTR acts as a promoter-enhancer post-integration. Moreover, it influences the host cell's transcription machinery and alters the quantity of transcription.

Gatignol and colleagues [52] discovered a second TAR binding gene (TARBP2) only difference is that this gene does not share chromosomal location with any of the AD genes found in this study (Table 6 shown in supplementary material). They purified a cDNA, TARBP2, and found that it encoded a 345-amino acid protein and Kozak and colleagues [53] mapped the TARBP2 gene on chromosome 12. with the same method, they also mapped the pseudogene (TARBP2P) on chromosome 8. TARBP2P was another HIV-1-related gene that did not share a chromosomal location with any of the AD associated genes.

PSEN2 interacts with PSARL located on chromosome 3 (Table 2, see supplementary material) [8]. PSARL is a 379-amino acid protein with molecular mass of 42.2 kD. The HIV-1 related gene located on the same chromosome is CMKBR5 (also known as CCR5). Mummidi and colleagues [54] analyzed the structure of CMKBR5, and discovered that this gene contains four exons, and two introns. It was by radiation hybrid mapping that Liu and colleagues [55] localized it on chromosome 3p21. Dragic and colleagues [56] identified CMKBR5 as a co-receptor for the HIV-1. It was not only a co-receptor but also a primary cofactor for the mediated entry of the HIV-1 envelope gp120. Later, Rottman and colleagues [57] showed CMKBR5 expression by bone marrow-derived cells that are targets for HIV-1 infection. Expression also included a subpopulation of lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages, primary and secondary lymph organs and noninflamed tissues, neurons, astrocytes and microglia. CMKBR5 showed expression in other tissues like epithelium, endothelium, vascular smooth muscle, and fibroblasts. Rottman's results suggested that CCR5+ cells are engaged to inflammatory regions or sites resulting in the facilitated transmission of macrophage-tropic strains of HIV-1.

Concurrently, the gene Interleukin-10 (IL10) was mapped on chromosome 1 by Kim and colleagues [44]. The study also showed the mouse IL10 to contain 5 exons at about 5.2 kilobase (kb). Shin and colleagues [58] identified associations for HIV-1 infection and progressions to AIDS with markers in the IL10 promoter region. Individuals who carried the 5′ promoter allele showed an increased risk in HIV-1 infection and progressed to AIDS. Protection or susceptibility was related to the CCR5 on chromosome 3 and previously mentioned [58]. T10 also showed to be closer to the AD related gene PSEN2 in comparison to the other HIV-1 associated gene on chromosome 1 (Table 5 in supplementary material). Shin and colleagues [58] also noted studies by Rosenwasser and Borish who suggested that AIDS progression might be hindered by immunotherapeutic strategies similar to those of IL10.

An additional gene found was Calsenilin (CSEN), a presenilin binding protein, identified as a neuronal protein found on chromosome 2, and binds to calcium [59] (Table 2, under supplementary material). Using the yeast 2-hybrid system with the last 103 amino acids of the presenilin-2 protein, Buxbaum and colleagues [59] identified CSEN to interact with both presenilin-1 and presenilin-2 in cultured cells and regulated the levels of a proteolytic product of presenilin-2. Their conclusions led to the understanding that calsenilin may mediate the effects of wild type and mutant presenilins on apoptosis and on Aβ formation. Later studies by Leissring and colleagues [60] suggested that calsenilin, or its downstream effectors, may represent feasible targets for therapeutic intervention in Alzheimer disease. The presenilin C-terminus is the domain relevant for calcium signaling effects and offers a method for future clinical AD therapy.

On the same chromosome, the HIV-1 associated gene is HIV-1 Rev-binding protein (HRB) (Table 5 see supplementary material) [61]. Bogerd and colleagues [62] showed that HRB binds to the Rev activation domain in vitro and in vivo and to functionally equivalent domains in Rev proteins from diverse viruses. Another study, by Sanchez-velar and colleagues [63], concluded that HRB is a cellular Rev cofactor that is essential for the nuclear support of the viral RNAs, a crucial factor needed for the survival of its pathology. An additional Rev interacting protein is also found in chromosome 12, although with no AD associated genes located on this chromosome, it is still cited for its function. It has been assumed that its function and interaction with HIV-1 Rev is only a name analysis with no publications describing this interaction. An additional gene (HRBL) related to the Rev/Rex activating domain-binding protein on chromosome 7, with also no sharing of AD associated genes.

Along with those genes found to share the same chromosome location, there were still several that did share the same chromosome locus with AD related genes and have indirect similarity with other genes found in this study. Those related to HIV-1 found on chromosome 6, 7, 8, 12, and 22 or X are LOC442267 and LOC401233 on 6; HRBL on 7; LOC442391 and TARBP2P on 8; HRB2, HIVE1 and TARBP2 on 12; and HTATSF1 on X (Table 2 and Table 6 in supplementary material). The gene, LOC442267, found in chromosome 6 is an HIV-1 Nef interacting protein. The Nef protein in the HIV genome is one that interacts with the host cell signal transduction proteins to provide it with long-term survival of the infected T cells and to destroy non-infected T cells [10]. Baur and colleagues [15] reported that Nef associates with two different kinases. This study concluded that deletion of a short α-helix in the N-terminus (composed of all Nef proteins) significantly reduces virion infectivity. In turn, this gene (LOC442267) interacts with this crucial protein found in the HIV-1 genome. The HIVE1 gene on chromosome 12 had no chromosomal partner with AD associated genes studied (Table 6 under supplementary material). Findings by Hart and colleagues [64] attempted to identify the human chromosomes that encode cellular factors that in the presence of tat, support enhanced HIV gene expression. Their study of hybrid cell clones from the fusion of human and Chinese hamster ovary cells showed that human chromosome 12 and the HIV tat gene are necessary for high levels of viral gene expression. Although, with similar findings reported by Newstein and colleagues [65], this mechanism is not likely to be true, because cell surface CD4, detected by immunostaining and flow cytometry, was present in only one of the four hybrid clones that produced a high level of the virus. Probably this alone is capable of stimulating HIV gene expression and replication. Apolipoprotein-E the allele was correlated with late-onset AD did not have an HIV-1 related gene in its same chromosome, a possible indication that late-onset AD has no genetic relationship to that of the genes found to interact with HIV-1 genes. Another HIV-1 related gene, HTATSF1, was located on the 22nd chromosome, the X chromosome. HTATSF1 is a stimulatory factor of the tat gene, and the regulatory gene found related to acceleration in the production of more HIV virus in transfected cells previously mentioned [19] (Table 2 see supplementary material). This tat stimulator has shown, with the use of immunoblot analysis as a 140 kD phosphoprotein. This study suggested, HTATSF1, to mediate a broadly active cellular process. Another analysis (binding) showed it to weakly associate with the tar RNA, another HIV regulatory gene.

Conclusion

In spite of the differences between AD and HAD clinically, we hypothesize a relationship in gene location, function, and expression between AD and HIV-associated disease. AD and HIV-1-associated disease were reported to share series of genes that directly deal with their organization and pathology. The functionality of a related group of genes involved in each disease was shared between those in this comparison. The dementia related genes were closely located on the chromosomes with the HIV-1-associated genes.

Those AD-associated genes are functionally related to one another as APP-related and binding proteins. Briefly, some of their functions were to link to the cytoplasmic tail of APP and to other amyloid-β precursor-like proteins (APLP2). This conclusion suggests further research in this particular area of AD pathology, by questioning the detailed function of these specific proteins and creating a possible alternative treatment. Along with this association, the connection between some of the Amyloid-β precursor protein and HIV-1 interacting genes generated the following genes: HSHIN1, LOC391810, HTATIP2, HTATIP, and CCL5. Another possible relationship and a target of future research, is the possibility of having a RANTES (CCL5) representative in the same chromosomal region of an Amyloid-β related gene. With continued research in this region, the gene may be located and eventually lead to analyzing its structure, function, and expression, with a possible creation of a therapeutic agent for inhibition of HIV-1 infection and ascertaining its relationship with AD.

The presenilins also are genes needing further investigation. PSEN1 and PSEN2, have regulatory control of APP processing. The investigation of this issue provides a better understanding a possible treatment of AD. Briefly, they show a role in chromosome organization and segregation, two very important factors related to chromosomal disease as well as their effects on gamma-secretase and APP formation. Their binding protein, CSEN regulates the levels of a proteolytic product of presenilin-2. This finding may lead to the understanding of calsenilin on its ability to mediate the effects of wild type and mutant presenilins on apoptosis and on beta-amyloid formation. CSEN could then be characterized as a critical gene in the pathogenesis of AD and possible target for therapeutic involvement in AD. This produces another aim of research to find how this capability might prevent APP regulation in AD patients.

It can be concluded that those genes able to bind to the HIV-1 regulatory genes (tat, rev, Nef, and env) were found to have specific function in pathogenesis within HIV-1-related disease. This possibility produces a further goal to examine how these regulatory genes can be altered by the interaction of their binding-related genes. With the speculation that there already exists Rev-like sequences in our genome, one can further study their interaction with their binding protein (HRB) to possibility control its ability to control HIV-1 proteins in host cells. Another possible area of research is generated with the gene LOC442267, in which this gene is able to interact with nef. If its complete function and expression were known, this might be another key to fully understand the pathogenesis of HIV-1 and possibly produce treatments to aid in its suppression. Along with these HIV-1 associated genes, CCL5, has a possible relationship with an Aβ binding protein, APBB3. This gene has the ability to suppress the development of AIDS, block HIV infection, and diminish transcription. A possible result of this research may be to reverse transcription induction processes and, thus, decrease the chances of the development of AIDS. Future work will correlate possible statistical relationships as well as a detailed functional analysis. In addition, sequence similarities among the various gene groups will be analyzed.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Lissette Diaz and Daniel Yanez for their assistance with the manuscript. We also thank Professor Carl Eisdorfer (University of Miami Miller School of Medicine) for comments. Support was received in part from the University of Miami Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Bridge Program and from NIH (DA 14533, DA 12580, DA 07909, DA 04787, AG 19952, and GM 56529).

References

- 1. http://www.alzheimers.org/pubs/genefact.html.

- 2. http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=17139.

- 3.Khachaturian ZS, Radebaugh TS. Alzheimer's disease: Cause(s), Diagnosis, Treatment, and Care. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emilien G, et al. Alzheimer's disease: Neuropsychology and Pharmacology. Basel: Birkhauser Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKhann G, et al. Neurology. 1984;939:944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selkoe DJ. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landthaler M. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2162. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verdile G, et al. Focus on Alzheimer's disease research. 1999;258:385. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popescu BO, Ankarcrona M. Journal of Alzheimer's disease. 2004;6:123. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. http://www.clunet.edu/BioDev/omm/hiv1nef/molmast.htm.

- 11.Weisgraber KH, et al. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1981;256:9077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanzi E, Bertram L. Neuron. 2001;32:181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00476-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minagar A, Shapshak P. Neuro-AIDS. New York: Nova Science Publication; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cysique LA, et al. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:350. doi: 10.1080/13550280490521078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baur S, et al. Immunity. 1997;6:283. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minagar A, et al. J Neurological Sciences. 2002;202:13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith MA, et al. Cell. 1997;17:2653. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuljis RO, et al. J NeuroAIDS. 2002;2:19. [Google Scholar]

- 19. http://www.hhmi.org/news/cullen.html.

- 20. http://www.mcld.co.uk/hiv/?q=rev.

- 21.Shapshak P, et al. Inflammatory Disorders Of The Nervous System: Clinical Aspects, Pathogenesis, and Management. New Jersey: Humana Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapshak P, et al. Frontiers in Biosciences. 2006;11:1774. doi: 10.2741/1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masters CL, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1985;82:4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLoughlin DM, Miller CC. FEBS Lett. 1996;397:197. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guénette SY, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1996;93:10832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von der Kammer H, et al. Genomics. 1994;10:308. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng P, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1998;95:14745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu Q, et al. Human Genetics. 1998;103:295. doi: 10.1007/s004390050820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao X, Südhof TC. Science. 2001;293:115. doi: 10.1126/science.1058783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanahashi H, Tabira T. Neurosci Lett. 1999;261:143. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00995-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao H, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1998;95:2146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan YC, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1990;87:2405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagase T. DNA Resources. 1996;3:321. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glass JD. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1996;19:1. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schall T, et al. J Immun. 1988;141:1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donlon TA, et al. Genomics. 1990;5:548. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90485-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cocchi F, et al. Science. 1995;270:1811. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arenzana-Seisdedos F, et al. Nature. 1996;383:400. doi: 10.1038/383400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bakhiet M, et al. Nature Cell Biol. 2001;3:150. doi: 10.1038/35055057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.An P, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2002;99:1002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levy-Lahad E, et al. Science. 1995;269:973. doi: 10.1126/science.7638622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherrington R, et al. Nature. 1995;375:754. doi: 10.1038/375754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogaev EI, et al. Genomics. 1997;40:415. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim JM, et al. J Immun. 1992;148:3618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheuner D, et al. Nature Med. 1981;2:864. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams M, et al. Nature. 1992;355:632. doi: 10.1038/355632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kenmochi N, et al. Genome Res. 1998;8:509. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kovacs DM, et al. Nature Med. 1996;2:224. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levy-Lahad E, et al. Genomics. 1996;34:198. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J, et al. Cell. 1997;90:917. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu F, et al. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2128. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gatignol A, et al. Science. 1991;251:1597. doi: 10.1126/science.2011739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kozak CA, et al. Genomics. 1995;25:66. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mummidi S, et al. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu R, et al. Cell. 1996;86:367. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dragic T, et al. Nature. 1996;381:667. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rottman JB, et al. Am J Path. 1997;151:1341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shin HD, et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2000;97:14467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buxbaum JD, et al. Nat Med. 1998;4:1177. doi: 10.1038/2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leissring MA, et al. et al. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2000;97:8590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones T, et al. Genomics. 1997;40:198. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bogerd HP, et al. Cell. 1995;82:485. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90437-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sánchez-Velar N, et al. Genes Dev. 2004;18:23. doi: 10.1101/gad.1149704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hart CE, et al. Science. 1998;246:488. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Newstein M, et al. et al. J Virol. 1990;64:4565. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4565-4567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.