Abstract

T4 Lysozyme has two easily distinguishable but energetically coupled domains: the N- and C-terminal domains. In earlier studies, an amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange pulse-labeling experiment detected a stable sub-millisecond intermediate that accumulates before the rate-limiting transition state. It involves the formation of structures in both the N- and C-terminal regions. However, a native-state hydrogen exchange experiment subsequently detected an equilibrium intermediate that only involves the formation of the C-terminal domain. Here, using stopped-flow circular dichroism and fluorescence, amide hydrogen exchange-folding competition, and protein engineering methods, we reexamined the folding pathway of T4-lysozyme. We found no evidence for the existence of a stable folding intermediate before the rate-limiting transition state at neutral pH. In addition, using native-state hydrogen exchange-directed protein engineering, we created a mimic of the equilibrium intermediate. We found that the intermediate mimic folds with the same rate of the wild type protein, suggesting that the equilibrium intermediate is an on-pathway intermediate that exists after the rate-limiting transition state.

Keywords: T4 lysozyme, hydrogen exchange, protein folding, hidden intermediate, protein engineering

INTRODUCTION

To understand the mechanism of protein folding, it is necessary to characterize the energy landscape of protein folding in detail, which includes partially unfolded intermediates, transition states, and their orders in the folding process. A number of methods have been developed to do so. Among them, amide hydrogen exchange (HX) has been particularly useful for obtaining the backbone structural information of folding intermediates at the level of residues and has been applied to study protein folding in both kinetic and equilibrium modes 1–4. For example, in the kinetic mode, an amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange pulse-labeling method has identified kinetic folding intermediates that transiently accumulate before the rate-limiting transition state 5–9. In the equilibrium mode, a native-state hydrogen exchange method has detected equilibrium folding intermediates that populate only in miniscule amount under native conditions 10–14. Both methods have been applied to T4 lysozyme 12, 15.

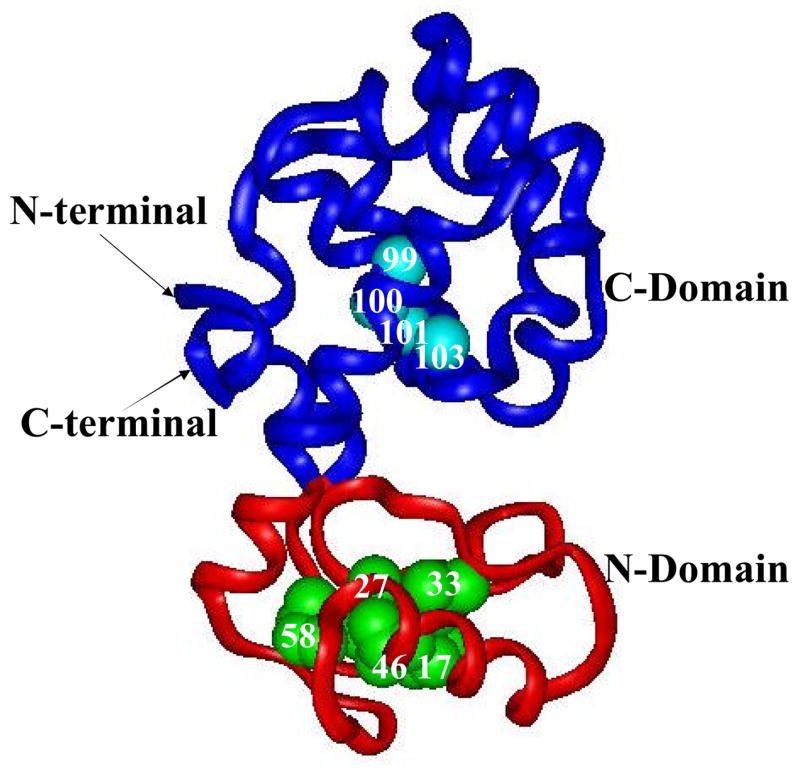

T4 lysozyme has two easily distinguishable but energetically coupled domains: the N- and C-terminal domains (see Fig. 1). The C-terminal domain has an α-helical structure, whereas the N-terminal domain includes both α-helices and β-strands. The earlier amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange pulse-labeling experiment on T4 lysozyme suggests that a stable submillisecond folding intermediate transiently accumulates before the rate-limiting transition state. It involves the partial formation of structures in both the N- and C-terminal domains 15 and is ≈3 kcal/mol more stable than the unfolded state in the presence of 1.5 M urea at pH 6 and 25°C. In contrast, the native-state hydrogen exchange experiment has identified an intermediate with the N-terminal domain (from residues 14 to 65) unfolded and C-terminal domain (from residues 1 to13 and 66 to 164) folded 12.

Fig. 1.

Structure of T4 lysozyme. The region with blue ribbon represents the N-terminal domain. The region with red ribbon represents the C-terminal domain. Small balls in cyan represent the four slowest exchanging amide protons, including residues 99, 100, 101, and 103. The hydrophobic residues I17, I27, L33, L46, and L58 in the N-terminal domain were shown in CPK models.

The simplest folding pathway for T4 lysozyme would be a sequential reaction with both intermediates on the folding pathway, as described in scheme (1):

| (1) |

Here, Ikin and Ieq represent the intermediates that are detected in the pulse-labeling and the native-state hydrogen exchange experiments, respectively. RLTS represents the rate-limiting transition state. Ieq is placed after the rate-limiting transition state because it is not observed in the kinetic folding experiment. However, the difference in the structures of the kinetic and equilibrium intermediates argues that it is unlikely that the two intermediates are on a sequential folding pathway. This is because it would require the unfolding of the N-terminal region in Ikin in order to form Ieq. Therefore, other possibilities need to be considered to define the folding pathway of T4 lysozyme. For example, the intermediate identified in the pulse-labeling experiment may be an on-pathway intermediate, whereas the intermediate detected by the native-state HX method is an off-pathway intermediate, as described in scheme (2):

| (2) |

However, the observation of an intermediate in a kinetic folding experiment alone does not necessarily mean that the intermediate is on the kinetic folding pathway 16–18. An off-pathway intermediate can also produce the same observable folding kinetics as an on-pathway intermediate when the folding rate from the unfolded state to the intermediate is too fast to be measurable by the conventional stopped-flow machine. In other words, the available experimental results can also be interpreted by assuming that the Ikin is an off-pathway intermediate, whereas the Ieq is an on-pathway intermediate that exists after the rate-limiting transition state, as shown in the folding reaction scheme (3):

| (3) |

Other possibilities include that both intermediates are off the folding pathway, as shown in scheme (4):

| (4) |

To investigate the kinetic role of the two intermediates, we re-examined the kinetic folding of T4 lysozyme by using a number of methods, including stopped-flow circular dichroism (CD) and fluorescence, hydrogen exchange-folding competition, and the native-state hydrogen exchange-directed protein engineering 19. We found no evidence for the population of a stable submillisecond folding intermediate under neutral pH. In contrast, we were able to create a mimic of the equilibrium intermediate identified in the native-state HX experiment. Importantly, the mimic of the equilibrium intermediate folded with the same rate of the native state, suggesting that the equilibrium intermediate is an on-pathway intermediate that exists after the rate-limiting transition state.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Sub-millisecond Folding Events

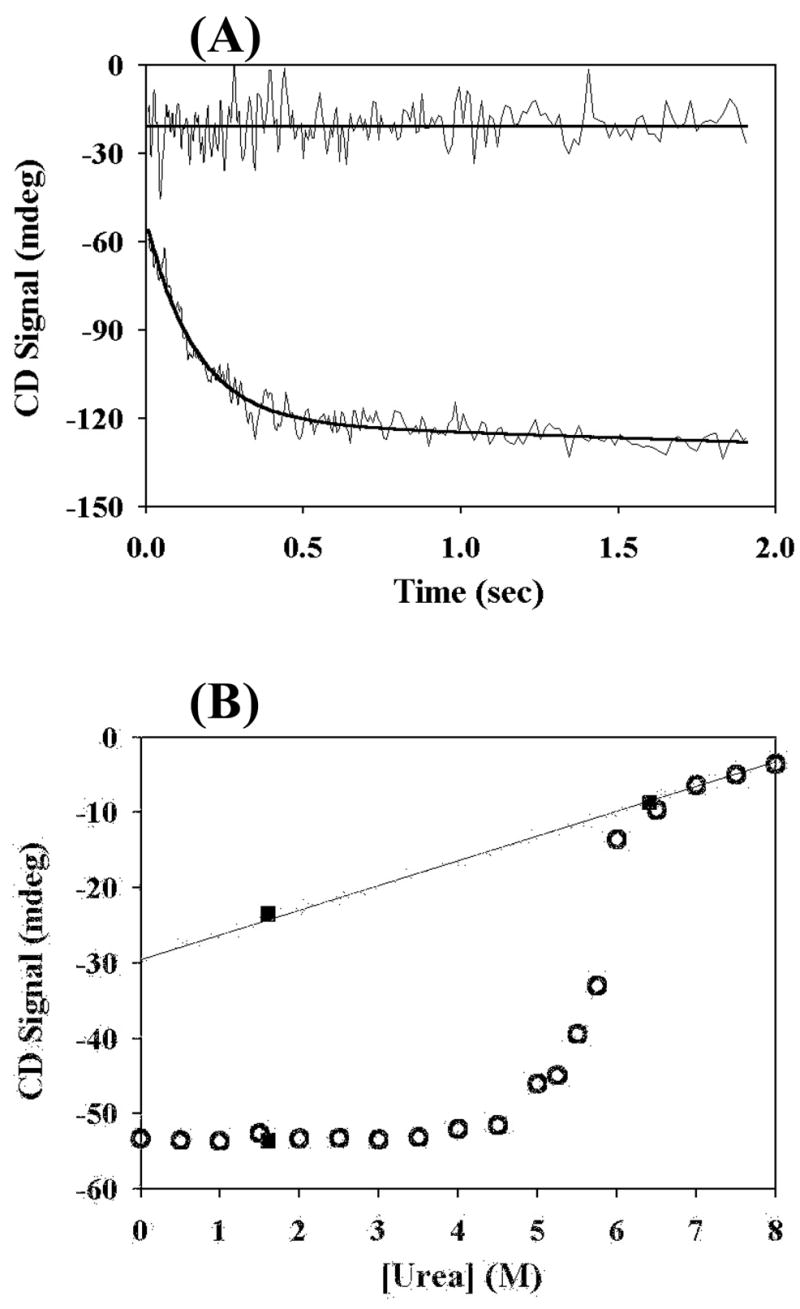

For the past several years, the views and experimental results regarding the sub-millisecond folding events have been controversial. Several proteins that were considered to have stable submillisecond intermediates based on earlier experiments have been caught into questions by more recent experiments 20. One of the problems is that transient aggregations have occurred in the folding of several proteins 21–23. Since the earlier pulse-labeling experiment on T4 lysozyme was done at extremely high protein concentrations (7 mg/ml during folding) and its kinetic folding intermediate is different from the equilibrium intermediate, a re-examination of the kinetic folding pathway appears to be necessary for clarifying this issue. Toward this goal, we first examined the CD and fluorescence signals at 3 msec after the initiation of the folding of T4 lysozyme. Folding of T4 lysozyme has two observable kinetic phases as monitored by both CD and fluorescence 15, 24. The fast phase has a rate constant ~17 sec−1 and occupies ≈80% of the observed amplitude. The slow phase has ≈20% of the total amplitude, which is attributed to the process of proline isomerization. Studies on the folding of T4 lysozyme have focused on the fast phase. Unfolding of the protein at high concentrations of denaturant shows a single exponential kinetic phase. Fig. 2A shows the kinetic traces of CD signals measured at 1.6 M urea and 6.0 M urea with the starting protein sample at 8 M urea (pH 6.0 and 25°C). Fig. 2B compares the results from the kinetic folding experiments with those from equilibrium unfolding experiments. No missing amplitude of the CD signal at 1.6 M urea was observed when the signals of the unfolded state at high concentrations of urea were linearly extrapolated to low concentrations of urea. It should be noted that in these studies T4 lysozyme is referred to a mutant WT* C54T/C97A.

Fig. 2.

Kinetic folding and equilibrium unfolding measured by CD. (A) Kinetic traces monitored by CD (222 nm) at 6.4 M (up curve) and 1.6 M (bottom curve) urea, respectively. (B) Equilibrium unfolding results (open circles) and the normalized values of the CD signals obtained at 3 msec (filled squares). The values have been normalized to the same protein concentration.

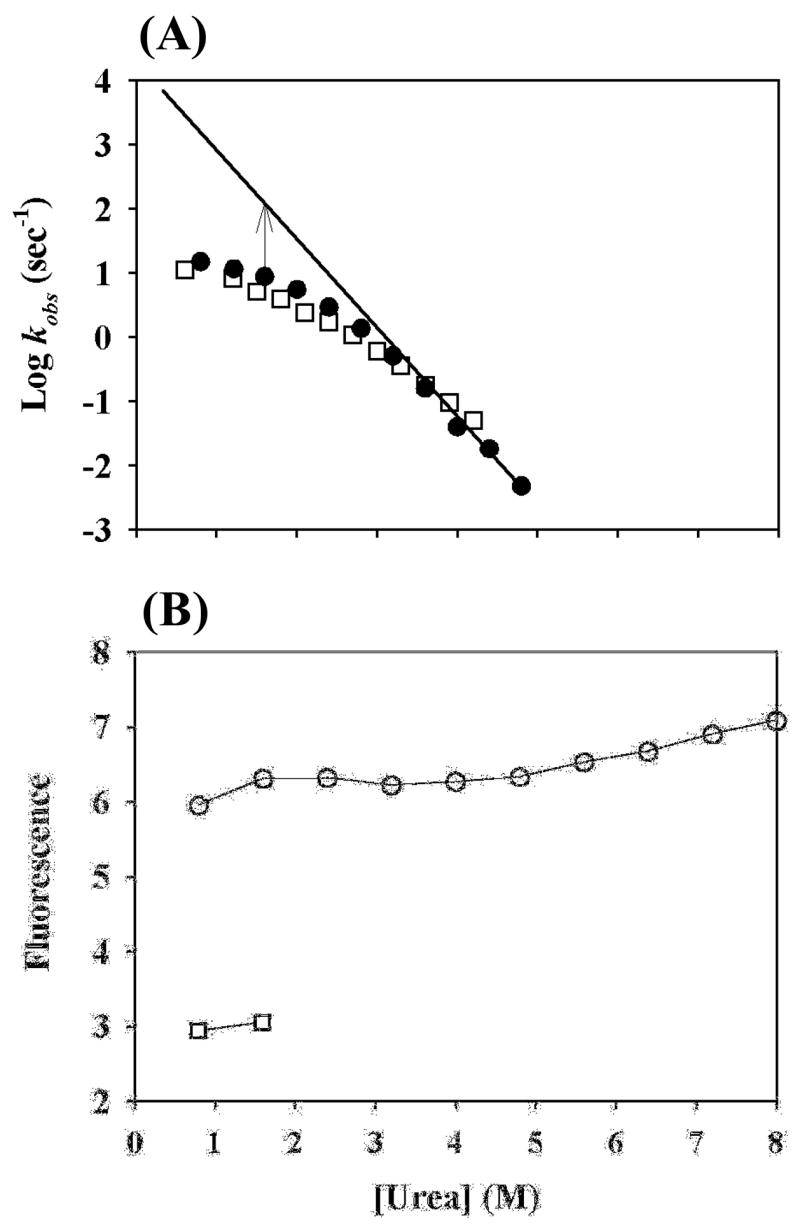

We further measured the folding rate by the stopped-flow fluorescence at pH 6.0 and 9.6, corresponding to the folding and pulse conditions in the earlier pulse-labeling experiment. Fig. 3A shows the logarithms of the folding rates as a function of denaturant concentrations. A non-linear behavior occurred. If one assumes that this non-linear behavior was caused by the existence of an early folding intermediate, it can be estimated that at 1.5 M urea, at which the earlier pulse-labeling experiment was performed, the putative intermediate would have a stability of ≈1.4 kcal/mol (see legends in Fig. 3A). This value, however, is significantly smaller than the value (≈2.8 kcal/mol) measured in the earlier pulse-labeling experiment 15. In addition, we also measured the fluorescence signal at 3 msec of the folding as a function of denaturant concentrations. At 3 msec, the putative intermediate should have formed without converting to the native state. Therefore, the fluorescence signal should fully come from the proposed intermediate. Since the signal shows no cooperative transition as a function of denaturant, it does not support the existence of a stable intermediate (see Fig. 3B). Therefore, these results do not support the existence of a stable sub-millisecond folding intermediate.

Fig. 3.

Folding rate constants and fluorescence signals for the early folding events determined in kinetic folding experiments. (A) Logarithms of the folding rate constants as a function of urea concentrations at pH 6 (filled circles) and pH 9.6 (open squares) determined in stopped-flow fluorescence experiments. At 1.5 M urea, the measured folding rate is smaller than the predicted value from the linear extrapolation by about a factor of 10, suggesting that a putative intermediate, if it exists, would be more stable than the unfolded state by ~1.4 kcal/mol. (B) Fluorescence signals (open circles) observed at 3 msec after the initiation of folding as a function of urea concentrations in stopped-flow fluorescence experiments. The non-cooperative unfolding suggests the absence of a stable intermediate at 1.5 M urea. The data (open squares) indicate fluorescence signals for the native state.

Hydrogen Exchange-Folding Competition and Dead-time Pulse-labeling

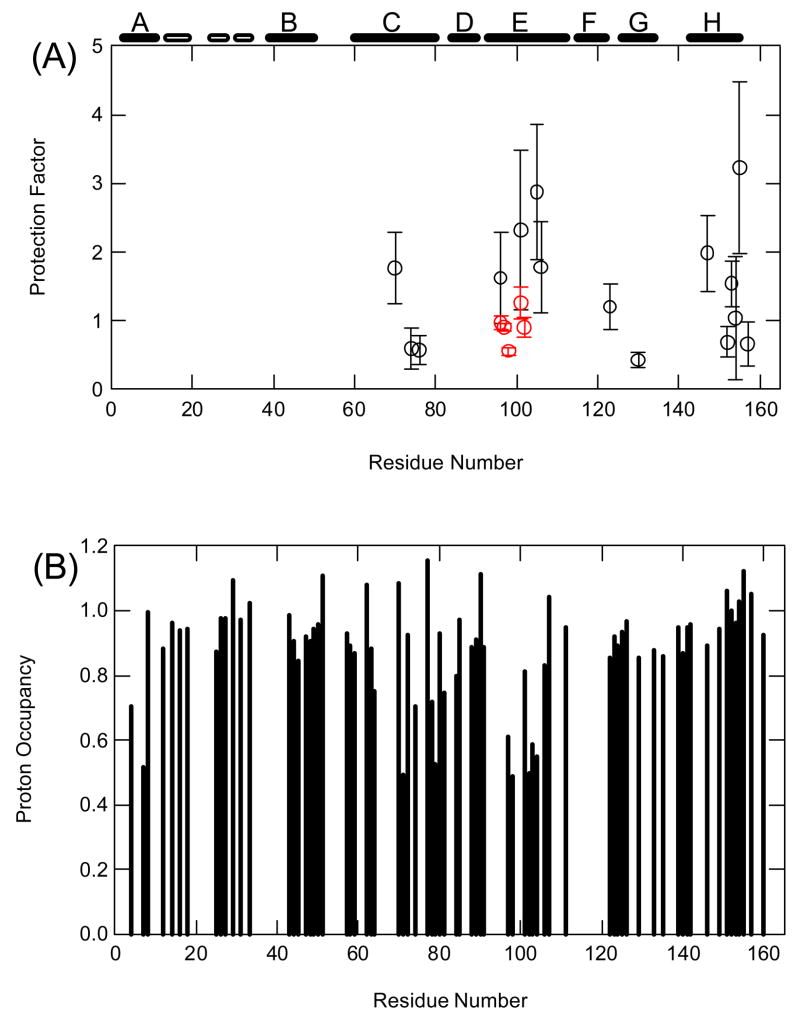

A hydrogen exchange pulse-labeling experiment involves two important steps: folding at neutral pH and pulse at high pH. If one of the two steps involves transient aggregations, it would lead to the protection of amide protons and the conclusion for the existence of early folding intermediates. To examine the two steps separately, we performed the hydrogen exchange-folding competition experiment at pH 6.8 and 25°C 25, 26. Under this condition, the folding rate is close to the intrinsic exchange rates of many amide protons of T4 lysozyme, which allows more accurate measurement of the protection factors (Pf = kint/kex) for amide protons in the submillisecond state (see methods). Here, kint and kex are the intrinsic exchange rate constant 27 and the measured exchange rate constant, respectively. Because most amide protons can exchange in the native state through local structure fluctuations, only 15 amide protons that are heavily protected in the native state could be used to characterize the structure formation of the submillisecond state in the competition experiment. We found that the protection factors for these amide protons ranged from 0.5 to 3.5, a typical range for amide protons in an unfolded polypeptide chain (Fig. 4A). These include four amide protons from residues R96, N101, Q105 and M106, which are shown to be heavily protected with Pf ~ 100 in the earlier pulse-labeling experiment 15. Thus, these results suggest that the observation of the protections of amide protons in the earlier pulse-labeling experiment is not due to the formation of a submillisecond intermediate at neutral pH.

Fig. 4.

Hydrogen exchange-folding competition and dead-time pulse-labeling experiments for WT* and its mutants. (A) Competition experiment for wild-type at pH 6.8 and 25°C (black) and the T4_IM at pH 7.1 and 25°C (red). (B) Dead-time pulse-labeling experiment for WT* with labeling time of 13 ms at pH 10.2. The error bars in (A) and (B) were estimated from three independent experiments. The location of the secondary structures is shown on top of the figure. The open bar indicates the position of β-strand. The folding rates (kf) used to calculate exchange rates (kex) by Eq. (9) are 14 and 34 sec−1 for wild-type and the T4_IM, respectively. The larger folding rate of the T4_IM is likely due to the shorter linker.

To examine the folding at pulse condition, we performed a dead-time pulse-labeling experiment, in which the unfolded protein sample in D2O and 8.5 M D-urea was mixed with a H2O solution at pH 10.2 by a ratio of 1:9. After 13 msec, the sample was quenched at pH 3.0. At pH 10.2 and 25°C, unprotected amide deuterons can exchange with solvent protons in less than 1 msec 27. Fig. 4B shows the proton occupancy measured at pH 3.0 and 20°C, the same condition used in the earlier pulse-labeling experiment. We found that some amide protons in the A, C, D, and E helices were strongly protected within the dead time (≈1 msec) of our quenched-flow instrument. However, no significant protections for amide protons in the N-terminal domain occurred. Thus, these results suggest that the protections observed in the earlier pulse-labeling experiment occurred during the pulse at high pH.

Although amide proton protections were observed in the dead-time pulse labeling experiment, the pattern of the protection is different from that in the earlier pulse-labeling experiment. For example, some amide protons in the N-terminal domain are also strongly protected in the earlier pulse-labeling experiment, whereas they are not protected in the current experiment (Fig. 4B), suggesting that pulse-labeling results are sensitive to subtle differences in experimental conditions. Since we observed no concentration dependent folding rates down to μM protein concentrations (unpublished results), it is intriguing that protections of amide protons occurred at high pH but the folding rate remains the same as that at neutral pH (see Fig. 3A). One possible interpretation is that the interactions formed in the early stage of the folding remain formed in the rate-limiting transition state.

Measurement of Unfolding Rate by Hydrogen Exchange at High pH

A non-linear logarithm of the folding rate constant as a function of denaturant concentration is commonly taken as the evidence for the existence of an early folding intermediate. However, it has been shown recently that the non-linear behavior could also be caused by the change of rate-limiting transition states 28 or a funnel-like energy landscape 29, 30. For example, in the case of barnase, the curvature in the folding arm of the logarithm of folding/unfolding rate constants versus denaturant concentration (chevron plot) is caused by the switch of the rate-limiting transition states rather than population of stable submillisecond intermediates. The evidence is that the logarithm of the unfolding rate constant is curved down equally as the logarithm of the folding rate constant at low concentrations of denaturant (for details, please read Takei et al. 26). In contrast, if the curvature of the logarithm of the folding rate constant is caused completely by the formation of a stable early folding intermediate, the logarithm of the unfolding rate constant should be a linear function of denaturant concentrations.

To distinguish the above two possibilities, we performed amide hydrogen exchange experiment at high pH at zero denaturant, which allows the measurement of unfolding rate constant under native conditions. Exchangeable amide hydrogens (NH) involved in the hydrogen-bonded structure can exchange with solvent hydrogens only when they are transiently exposed to solvent in some kind of closed-to-open reactions 31, as indicated in equation (3). Here, kop is the kinetic opening rate constant and kcl is the kinetic closing rate constant. kint is the intrinsic exchange rate constants in the open form, which is normally derived from unfolded peptide models 27.

| (5) |

When the closing reaction is faster than kint (EX2 condition), the exchange rate of any hydrogen, kex, is determined by its chemical exchange rate in the open form multiplied by the equilibrium opening constant, Kop.

| (6) |

This leads to free energy for the dominant opening reaction:

| (7) |

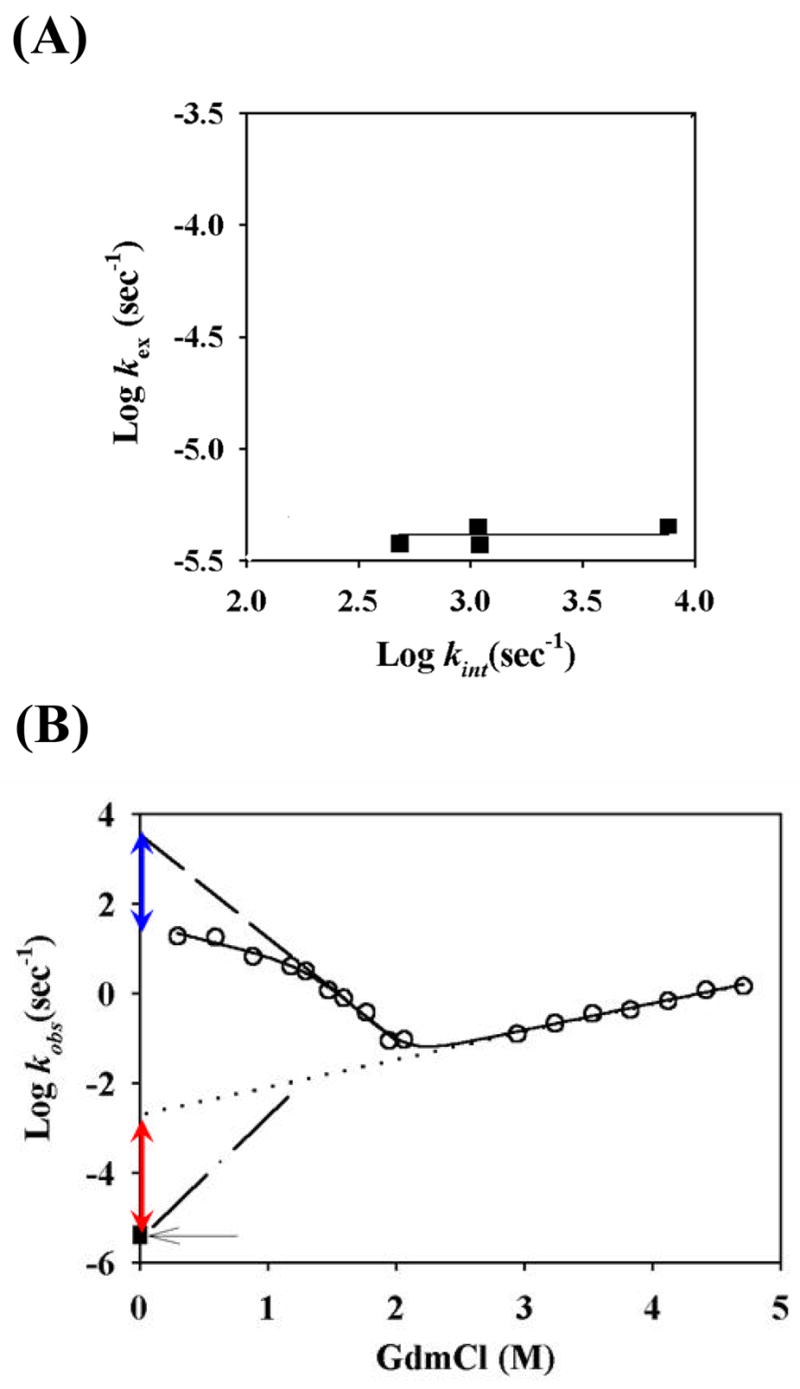

where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature. When the closing reaction is slower than kint (EX1 condition), the exchange rate, kex, is determined by the opening rate constant kop. For the slowly exchanging amide protons that can only exchange through global unfolding, the kop will be the global unfolding rate constants. Thus, under EX1 conditions, the measurement of the exchange rates of slowly exchanging amide protons provides a way to measure the global unfolding rates of proteins. Fig. 5A plots the logarithms of the measured exchange rates for the four slowest exchanging amide protons (99, 100, 101, and 103) versus their intrinsic exchange rates at pH 9.6 and 25°C. The measured values are very similar among the four protons even though their intrinsic exchange rates spread over an order of magnitude, suggesting the exchange indeed occurs through an EX1 mechanism. Therefore, the measured exchange rates are the unfolding rate of the native state.

Fig. 5.

Folding and unfolding rates at pH 9.6 and 25°C. (A) Test of hydrogen exchange mechanism. The independence of the measured hydrogen exchange rates for the slowest exchanging amide protons on the intrinsic exchange rates suggests that the exchange occurs in EX1 mechanism and the measured exchange rate represents the unfolding rate. (B) Folding and unfolding rate constants measured by stopped-flow and hydrogen exchange. The solid curve is a fit to a three-state model with equations of [8]–[10]. GdmCl was used to obtain the broad unfolding arm of the chevron plot. The dashed line in the folding arm of the chevron plot represents the linear extrapolation of the data near the bottom region of the chevron plot. The linear dotted line represents the extrapolation of the unfolding arm of the chevron plot. The dashed dotted line connected to the measured unfolding rate (solid square indicated by the single arrow) by the HX method represents a possible deviation of log ku from the linear region. At zero denaturant, the measured unfolding rate by HX under EX1 condition is much smaller than that extrapolated from the unfolding arm of the chevron plot. The difference in the unfolding rate (red double arrow) is similar to that between the measured folding rate and the linearly extrapolated folding rate (blue double arrow), suggesting that the curvature in the folding arm of the chevron plot is caused by the movement or switch of the rate-limiting transition state rather than the existence of a stable early folding intermediate.

We also performed stopped-flow folding/unfolding experiments at pH 9.6 and 25°C. In this experiment, we used GdmCl since it allows the unfolding arm of the chevron plot to be measured in a broader range. Fig. 5B compares the unfolding rate measured by the hydrogen exchange method with those measured in the kinetic unfolding experiments at high denaturant concentrations. The unfolding rate constant measured by the hydrogen exchange method at zero denaturant is ≈2 orders of magnitude smaller than the value extrapolated linearly from the logarithm of the unfolding rates at high concentrations of denaturant. This difference is very close to that between the measured folding rate at zero denaturant and the value extrapolated from the linear region near the bottom of the chevron plot. In other words, the directly measured ku/kf at zero denaturant is close to that linearly extrapolated from the linear region near bottom of the chevron plot. Thus, the change of the rate-limiting transition state rather than the population of a stable early folding intermediate caused the curvature of the chevron plot.

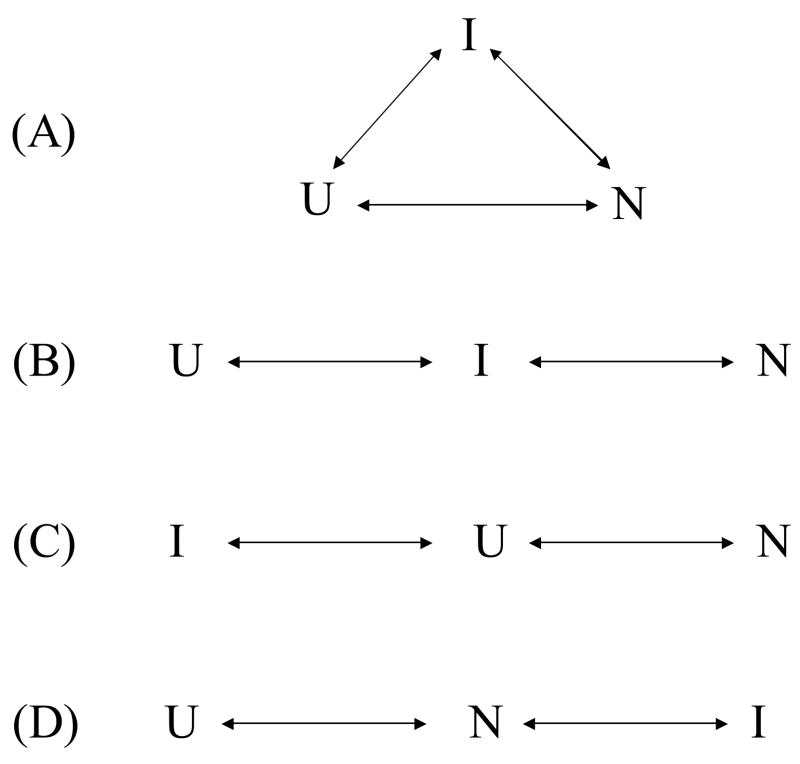

The Order of a Folding Reaction with an Intermediate

A general description of a protein folding reaction with an intermediate is the triangle scheme as shown in Fig. 6A. Depending on the relative conversion rate of each folding step, three special cases can occur. The first case is that the direct folding from “U” to “N” is the slowest and “I” is considered as on-pathway (Fig. 6B). The second case is that the direct folding from “I” to “N” is the slowest and “I” is considered as off-pathway (Fig. 6C). The third case is that the folding from “U” to “I” is the slowest and “I” is considered as kinetically isolated from “U” or “I” is a conformation state that fluctuates in the ensemble of the native state (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Folding reaction schemes with an intermediate. (A) A general triangle scheme. (B) On-pathway intermediate. Direct folding from U to N is the slowest. (C) Off-pathway intermediate. Folding from I to N is the slowest. (D) The intermediate is kinetically isolated. Folding from U to I is the slowest.

Accordingly, if the apparent folding from “U” to “I” can be shown to have the same rate for the apparent folding from “U” to “N”, the third case, i.e., a kinetically isolated “I”, can be excluded. Moreover, if “I” can be shown to be undetectable in the kinetic folding experiment, then the second case can be further disproved, which would leave the first case as the reaction scheme. In the following, we use protein engineering to obtain and a mimic of the Ieq of T4 lysozyme and demonstrate that it folds from the unfolded state with the same rate of the folding of the WT*.

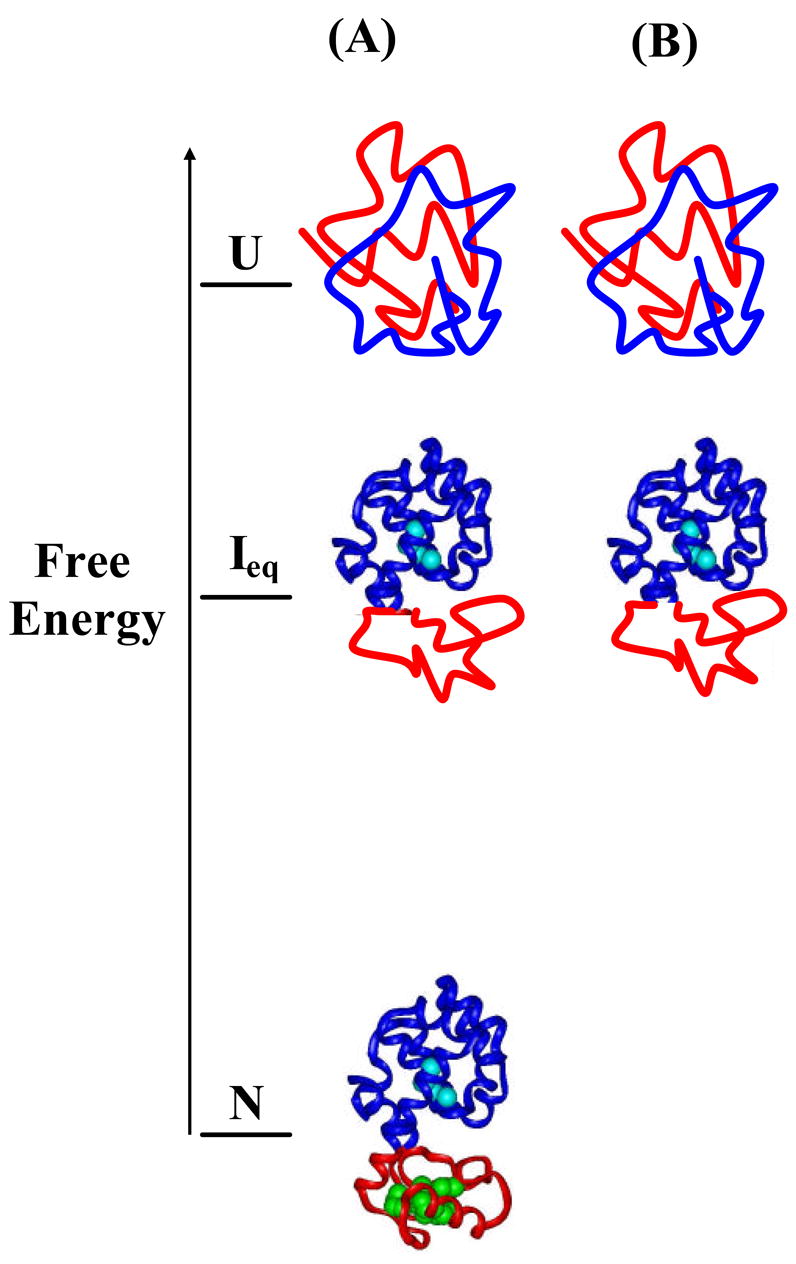

Populating Ieq by a Native-State Hydrogen Exchange-Directed Protein Engineering

To measure the apparent folding rate from the unfolded state to the Ieq, we used the native-state hydrogen exchange-directed protein engineering to populate the Ieq.19 Fig. 7A illustrates the free energy and the structures of the fully unfolded state, the equilibrium intermediate, and the fully folded state, characterized by the native-state hydrogen exchange. Under native conditions, the native state is the most stable state and dominantly populates in solution. Although the intermediate and the unfolded state also exist in solution, they are not directly observable due to their miniscule population. To populate the intermediate without disrupting the folded region of the protein, mutations can be made in the unfolded region of the intermediate to destabilize the native state (see Fig. 7B). In this case, we substituted five large hydrophobic residues (I17, I27, L33, L46, I58) in the N-terminal domain with Glycines (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 7.

Illustration of a native-state hydrogen exchange-directed protein engineering for populating the partially unfolded intermediate. (A) Free energies and structures of the WT*, intermediate, and unfolded state. The intermediate was identified by the native-state hydrogen exchange method. (B) Mutations in the N-terminal domain, which destabilize the native state have no effect on the stability of the intermediate, make the intermediate the most stable species. Hydrophobic core residues in the N-terminal domain, including I17, I27, L33, L46, and L58, were mutated to Glys (see Fig. 1).

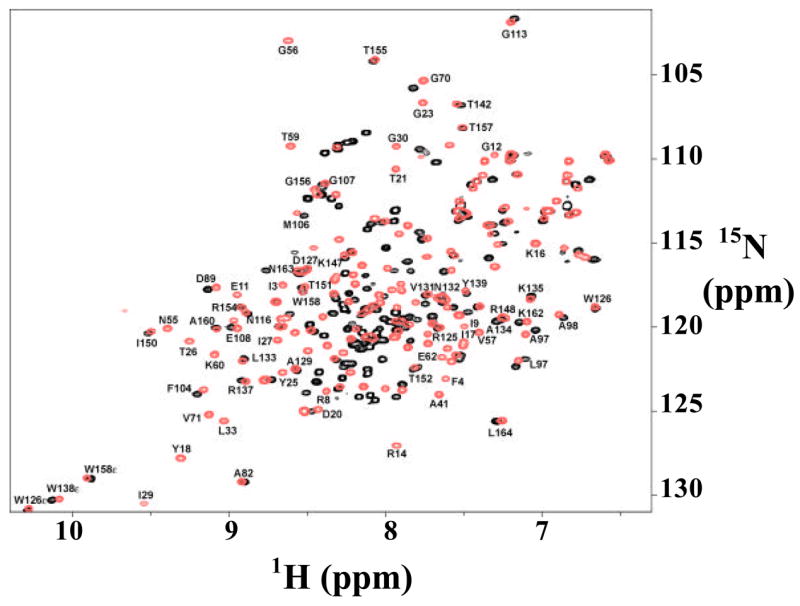

To test whether the intermediate has been populated, we assigned the resonances of the mutant by multi-dimensional NMR. Fig. 8 shows the overlay of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the WT* and the mutant. The chemical shifts of the amides in the C-terminal domain of the mutant showed little change when compared with those of WT*, whereas those of the N-terminal domain all move to the narrow region of 8.0 ± 0.5 ppm, a typical range for unfolded peptides. Thus, the NMR spectrum of this 5G-mutant is consistent with the structure of the intermediate detected by the native-state hydrogen exchange experiment.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of the HSQC spectra between WT* (black) and the 5-Glycine mutant (red).

Kinetic Folding Rates of the Ieq and the Native-State

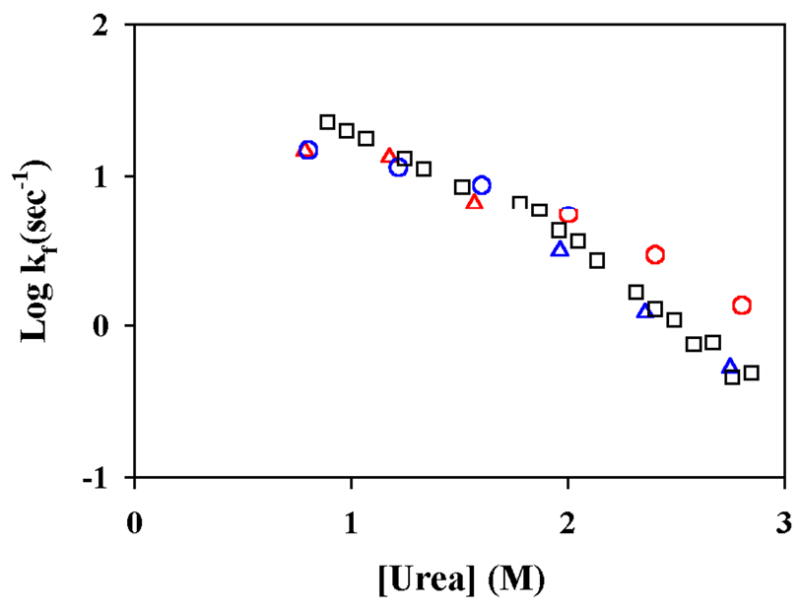

Fig. 9 compares the logarithms of the folding and unfolding rates of the 5G-mutant and the WT*. Both proteins have similar folding rate at low concentrations of denaturant, indicating folding from the unfolded state to the Ieq is not slower than the folding from the unfolded state to the native state. Therefore, the Ieq is not kinetically isolated from the unfolded state under such conditions. This conclusion was further confirmed with a new intermediate mimic T4_IM that has the region from residues 17 to 58 substituted by a short glycine linker (see Fig. 9 and accompanying paper). For this second mutant, a high-energy native state does not exist 32. Therefore, folding of the intermediate cannot go through the native state, providing more unequivocal evidence that the Ieq is an on-pathway intermediate and exists after the rate-limiting transition state. These results are consistent with an earlier experiment that showed that single mutations in the N-terminal domain in WT* did not affect the folding rate 24. In addition, we also performed the hydrogen exchange-folding competition experiment on T4_IM. The protection factors of the amide protons that can be studied were very close to 1, suggesting that these protons do not form any stable structures on the submillisecond time scale (Fig. 4A). It should be noted that, T4_IM is less stable than WT*. Only four amide protons in the E-helix (A97, A98, N101 and M102) can be studied in this experiment.

Fig. 9.

The folding rate of WT* (blue open circles), T4_IM (red open triangle), 5G-mutant (black open square).

Hidden Folding Intermediates

Most protein folding studies have focused on identifying and characterizing folding intermediates that exist before the rate-limiting transition states by studying the kinetic process of protein folding 33, 34. Hidden intermediates that exist after the rate-limiting transition state are studied only recently. They are identified in two different ways. Some are observed directly in kinetic unfolding experiments under denaturing conditions, which include RNase A 35, DHFR 36, lysozyme 37, and IL-1β 38. Others are identified as equilibrium intermediates by native-state hydrogen exchange methods, which include Cyt c10,39,40, T4 Lysozyme12, Rd-apocyt b56241, a PDZ-3 construct 42, and Barnase 43,44. Structural information on hidden intermediates is mainly derived from native-state hydrogen exchange experiments. For T4 lysozyme, earlier protein engineering studies have also shown the C-terminal region can fold independently 45.

The observation of hidden intermediates in both single- and multi-domain proteins with different folds suggests that they occur generally in protein folding, providing further evidence for the hypothesis that proteins use partially unfolded intermediates to solve the large-scale conformational search problem30, 46, 47.

CONCLUSION

The kinetic folding of T4 lysozyme was reexamined using a number of methods, including stopped-flow CD and fluorescence, hydrogen exchange-folding competition, and protein engineering. No stable submillisecond folding intermediates were detectable at neutral pH. The intermediate identified in the earlier native-state hydrogen exchange experiment was populated by a native-state hydrogen exchange-directed protein engineering method. It folded with the similar rate of WT* at low concentrations of denaturant. These results suggest that the intermediate is on the folding pathway and exists after the rate-limiting step, consistent with the folding behavior of several other small proteins. The folding behavior of T4 lysozyme at high pH, however, is more complex and remains to be investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein Expression and Purification

The expression system of a psuedo wild-type (C54T/C97A), WT*, of T4 lysozyme was kindly provided by Dr. Brian Matthews (University of Oregon). Glycine mutations were made using a quick-change mutation kit (Stratgen, CA). Proteins were expressed in E. coli (BL21DE3) and purified using ion exchange and reversed-phase HPLC. 15N and 13C labeled proteins were grown on minimum media with 15NH4Cl and 13C-Glucose as the sole sources for nitrogen and carbon.

NMR Characterization of Intermediates

1H-15N NMR spectra for both WT* and the 5G-mutant were collected at 25°C and pH 5.0 on a Bruker (Bellerica, MA) DRX 500-MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm x, y, z-shielded pulse field gradient triple resonance probe. The concentrations of the protein samples are ≈1 mM. 3D CBCACONH and HNCACAB spectra were collected for backbone resonance assignment. The NMR spectra were processed using NMRPipe48 and analyzed using NMRView 49 and Sparky (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky).

Kinetic Folding and Unfolding Experiments

Kinetic folding and unfolding experiments were done by using a stopped-flow apparatus (Biologic, France) with a dead time of ≈1 msec. In the kinetic folding experiments, proteins in 8 M urea or 6 M GdmCl were diluted quickly to initiate folding at different final concentrations of urea or GdmCl. The folding traces were fitted with two exponentials. Unfolding was initiated by mixing the folded proteins in the buffer solution with high concentrations of denaturant. A single exponential kinetics was observed for unfolding. The following equations were used to fit the measured folding rate constants of the fast phase and unfolding rate constants as a function of denaturant concentrations:

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

where KIUH2O is the unfolding equilibrium constant of the putative intermediate in water, kINH2O and kNIH2O are the values of the corresponding microscopic rate constants in the absence of denaturant, and m‡IN and m‡NI are the coefficients for the denaturant dependence of the microscopic rate constants. Den is either urea or GdmCl.

Hydrogen Exchange Experiments

Hydrogen exchange experiments were initiated by loading 0.5 ml protein sample in D2O at pDread 9.6 (100 mM Glycine and 50 mM Na3PO4) to the spin column (Sephdex 25, bed volume 3 ml) that was pre-equilibrated with H2O at pH 9.6 (100 mM Glycine and 50 mM Na3PO4). The column was spun for 1 min at 4000 rpm using a bench top centrifuge. The eluted protein sample was immediately transferred into an NMR tube for collecting a series of 1H-15N HSQC spectra. The concentration of the protein sample was ≈1 mM. The NMR spectra were processed using NMRPipe 47 and analyzed using NMRView 48 to obtain the exchange rate constants.

Hydrogen Exchange-folding Competition Experiments

The competition experiments were performed with the same stopped-flow apparatus. Folding of denatured lysozyme (≈5 mg/ml) in 8.5 M deuterated urea (pD 6.8, 10 mM MES/D2O) solution was initiated by 10-fold dilution with a buffer solution (pH 6.8, 10 mM MES/H2O). Reactions were allowed to proceed for several minutes before pH was adjusted to 3.1. Sample solutions were concentrated, and buffer was exchanged with a 10 % D2O and 25 mM Gly-HCl (pH 3.0) solution with Amicon cells. The HSQC spectra were measured at 20°C. Additional experiments were performed for T4-IM. In this case, the denatured protein in 6.0 M deuterated GdmCl (pD 7.1, 10 mM HEPES/D2O) was diluted into a refolding buffer (pH 7.1, 10 mM HEPES/H2O) by 10-fold. After the reaction, the buffer was exchanged with 10 % D2O and 50 mM NaAc (pH 5.0). Peak intensities were used to measure the proton occupancies with side-chain amides of 3 Trps (W126, W138 and W158) averaged as internal reference. The following relationship holds when the competition proceeded until native proteins were completely formed 19:

| (11) |

where Pocc(H) is proton occupancy and kex and kf are exchange and folding rates, respectively. The factors 0.8 and 0.2 represent the fraction of the trans and cis proline isomers responsible for fast and slow folding phases, respectively. Once one measures Pocc(H) and kf, kex can be calculated by eq. (9), and protection factors were calculated by kint/kex.

Dead-time Pulse-labeling Experiments

The pulse labeling experiments were performed with Bio-Logic QFM-4 instrument. Experiments were performed at 25 °C. 15N-labeled WT* was initially dissolved in 8.5 M deuterated urea solution and left overnight at room temperature to complete the amide hydrogen exchange process. The initial protein concentration was ~5.0 mg/ml. Refolding was initiated by a 10-fold dilution with high pH buffer (0.5 M CAPS, pH 10.2). After 13 ms, amide hydrogen exchange was quenched by diluting the sample with 1:2.5 into the quench buffer (25% acetic acid, pH 1.5) so that final pH was 3.1. The sample was concentrated using an Amicon cell with 10,000 molecular weight cut-off and adjusted to pH 3.0 with buffer solution (10% D2O, 25 mM Gly-HCl, pH 3.0). The 1H-15N HSQC spectra were collected at 20°C. The reference sample for the quantitative measurement of proton occupancy was prepared by heating 10 mg/ml protein solution in 10 % D2O for 1h.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Frederic Dahlquist for comments on the paper. H.K. was supported by the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS) Research Fellowships for Young Scientists. This research is supported by the intramural research program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baldwin RL, Roder H. Characterizing protein folding intermediates. Curr Biol. 1991;1:218–220. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(91)90061-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Englander SW, Mayne L. Protein folding studied using hydrogen-exchange labeling and two-dimensional NMR. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:243–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.001331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Englander SW. Protein folding intermediates and pathways studied by hydrogen exchange. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:213–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishna MM, Hoang L, Lin Y, Englander SW. Hydrogen exchange methods to study protein folding. Methods. 2004;34:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roder H, Elove GA, Englander SW. Structural characterization of folding intermediates in cytochrome c by H-exchange labelling and proton NMR. Nature. 1988;335:700–704. doi: 10.1038/335700a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Udgaonkar JB, Baldwin RL. NMR evidence for an early framework intermediate on the folding pathway of ribonuclease A. Nature. 1988;335:694–699. doi: 10.1038/335694a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miranker A, Robinson CV, Radford SE, Aplin RT, Dobson CM. Detection of transient protein folding populations by mass spectrometry. Science. 1993;262:896–900. doi: 10.1126/science.8235611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jennings PA, Wright PE. Formation of a molten globule intermediate early in the kinetic folding pathway of apomyoglobin. Science. 1993;262:892–896. doi: 10.1126/science.8235610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raschke TM, Marqusee S. The kinetic folding intermediate of ribonuclease H resembles the acid molten globule and partially unfolded molecules detected under native conditions. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:298–304. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai Y, Sosnick TR, Mayne L, Englander SW. Protein folding intermediates: native-state hydrogen exchange. Science. 1995;269:192–197. doi: 10.1126/science.7618079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain AK, Handel TM, Marqusee S. Detection of rare partially folded molecules in equilibrium with the native conformation of RNaseH. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:782–787. doi: 10.1038/nsb0996-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llinas M, Gillespie B, Dahlquist FW, Marqusee S. The energetics of T4 lysozyme reveal a hierarchy of conformations. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:1072–1078. doi: 10.1038/14956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan S, Kennedy SD, Koide S. Thermodynamic and kinetic exploration of the energy landscape of Borrelia burgdorferi OspA by native-state hydrogen exchange. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:363–375. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00882-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman JA, Harbury PB. The equilibrium unfolding pathway of a beta/alpha8 barrel. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu J, Dahlquist FW. Detection and characterization of an early folding intermediate of T4 lysozyme using pulsed hydrogen exchange and two-dimensional NMR. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4749–4756. doi: 10.1021/bi00135a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bai Y. Kinetic evidence for an on-pathway intermediate in the folding of cytochrome c. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:477–480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heidary DK, O’Neill JC, Jr, Roy M, Jennings PA. An essential intermediate in the folding of dihydrofolate reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5866–5870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100547697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capaldi AP, Shastry MC, Kleanthous C, Roder H, Radford SE. Ultrarapid mixing experiments reveal that Im7 folds via an on-pathway intermediate. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:68–72. doi: 10.1038/83074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takei J, Pei W, Vu D, Bai Y. Populating partially unfolded forms by hydrogen exchange-directed protein engineering. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12308–12312. doi: 10.1021/bi026491c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krantz BA, Mayne L, Rumbley J, Englander SW, Sosnick TR. Fast and slow intermediate accumulation and the initial barrier mechanism in protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:359–371. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu RA, Takei J, Barchi JJ, Jr, Bai Y. Relationship between the native-state hydrogen exchange and the folding pathways of barnase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14119–14124. doi: 10.1021/bi991799y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silow M, Oliveberg M. Transient aggregates in protein folding are easily mistaken for folding intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6084–6086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nawrocki JP, Chu RA, Pannell LK, Bai Y. Intermolecular aggregations are responsible for the slow kinetics observed in the folding of cytochrome c at neutral pH. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:991–995. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gassner NC, Baase WA, Lindstrom JD, Lu J, Dahlquist FW, Matthews BW. Methionine and alanine substitutions show that the formation of wild-type-like structure in the carboxy-terminal domain of T4 lysozyme is a rate-limiting step in folding. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14451–14460. doi: 10.1021/bi9915519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roder H, Wuthrich K. Protein folding kinetics by combined use of rapid mixing techniques and NMR observation of individual amide protons. Proteins. 1986;1:34–42. doi: 10.1002/prot.340010107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takei J, Chu RA, Bai Y. Absence of stable intermediates on the folding pathway of barnase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10796–10801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190265797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bai Y, Milne JS, Mayne L, Englander SW. Primary structure effects on peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins. 1993;17:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silow M, Oliveberg M. High-energy channeling in protein folding. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7633–7637. doi: 10.1021/bi970210x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan HS, Shimizu S, Kaya H. Cooperativity principles in protein folding. Methods Enzymol. 2004;380:350–379. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bai Y. Energy barriers, cooperativity, and hidden intermediates in the folding of small proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:976–983. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hvidt A, Nielsen SO. Hydrogen exchange in proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 1966;21:287–386. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Z, Huang Y, Bai Y. An on-pathway hidden intermediate and the early rate-limiting transition state of Rd-apocytochrome b562 characterized by protein engineering. J Mol Biol. 2005;352:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim PS, Baldwin RL. Specific intermediates in the folding reactions of small proteins and the mechanism of protein folding. Annu Rev Biochem. 1982;51:459–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.51.070182.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthews CR. Pathways of protein folding. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:653–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.003253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiefhaber T, Baldwin RL. Kinetics of hydrogen bond breakage in the process of unfolding of ribonuclease A measured by pulsed hydrogen exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2657–2661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoeltzli SD, Frieden C. Stopped-flow NMR spectroscopy: real-time unfolding studies of 6-19F-tryptophan-labeled Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9318–9322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiefhaber T, Bachmann A, Wildegger G, Wagner C. Direct measurement of nucleation and growth rates in lysozyme folding. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5108–5112. doi: 10.1021/bi9702391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roy M, Jennings PA. Real-time NMR kinetic studies provide global and residue-specific information on the non-cooperative unfolding of the beta-trefoil protein, interleukin-1beta. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:693–703. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sosnick TR, Mayne L, Englander SW. Molecular collapse: the rate-limiting step in two-state cytochrome c folding. Proteins. 1996;24:413–426. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199604)24:4<413::AID-PROT1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bai Y, Englander SW. Future directions in folding: the multi-state nature of protein structure. Proteins. 1996;24:145–151. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199602)24:2<145::AID-PROT1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chu R, Pei W, Takei J, Bai Y. Relationship between the native-state hydrogen exchange and folding pathways of a four-helix bundle protein. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7998–8003. doi: 10.1021/bi025872n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng H, Vu ND, Bai Y. Detection of a hidden folding intermediate of the third domain of PDZ. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fersht AR. A kinetically significant intermediate in the folding of barnase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14121–14126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260502597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vu ND, Feng H, Bai Y. The folding pathway of barnase: the rate-limiting transition state and a hidden intermediate under native conditions. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3346–3356. doi: 10.1021/bi0362267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Llinas M, Marqusee S. Subdomain interactions as a determinant in the folding and stability of T4 lysozyme. Protein Sci. 1998;7:96–104. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levinthal C. Are there pathways for protein folding? J Chim Phys. 1968;65:44–45. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wetlaufer DB. Nucleation, rapid folding, and globular intrachain regions in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:697–701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.3.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson BA, Blevins RA. NMRView: A computer program for the visulization and analysis of NMR data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]