Abstract

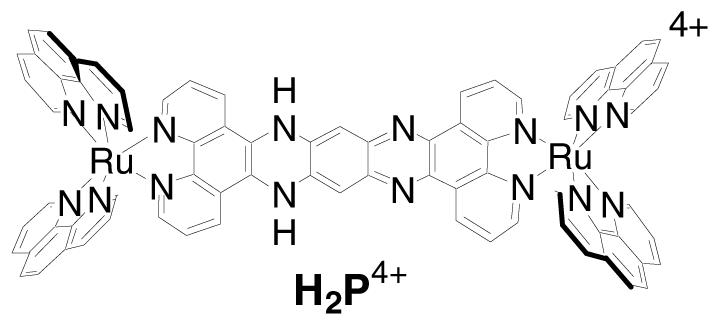

In the absence of O2, the cationic complex, [(phen)2Ru(tatpp)Ru(phen)2]4+ (P4+), undergoes in situ reduction by glutathione (GSH) to form a species that induces DNA cleavage. Exposure to air strongly attenuates the cleavage activity, even in the presence of a large excess of reducing agent (e.g., 40 equiv GSH per P4+) suggesting the complex may be useful in targeting cells with a low oxygen microenvironment (hypoxia) for destruction via DNA cleavage. The active species is identified as the doubly reduced, doubly protonated complex H2P4+ and a carbon-based radical species is implicated in the cleavage action.. We postulate that the pO2 regulates the degree to which carbon radical forms and thus regulates the DNA cleavage activity.

In the absence of O2, the cationic complex, [(phen)2Ru(tatpp)Ru(phen)2]4+ (P4+), undergoes in situ reduction by glutathione (GSH) to form a species that induces DNA cleavage. Exposure to air strongly attenuates the cleavage activity, even in the presence of a large excess of reducing agent (e.g., 40 equiv GSH per P4+) suggesting the complex may be useful in targeting cells with a low oxygen microenvironment (hypoxia) for destruction via DNA cleavage. The active species is identified as the doubly reduced, doubly protonated complex H2P4+ and a carbon-based radical species is implicated in the cleavage action.. We postulate that the pO2 regulates the degree to which carbon radical forms and thus regulates the DNA cleavage activity.

The use of transitions metal complexes in medicine has enjoyed extensive attention given the tremendous success of cisplatin as a chemotherapeutic agent1 and the ability of many metal complexes to interact with and damage cellular structures, particularly DNA.2-7

A large number of DNA cleaving metal complexes function via the activation of dioxygen to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydroxyl radical and superoxide radical.8,9 These ROS are ultimately responsible for the DNA cleavage. Others, including cisplatin and certain photoactivated,10-14 oxidizing15,16 or hydrolyzing complexes,8 do not require O2 to function, but they are also insensitive to the cellular [O2]. Compounds that show enhanced cleavage activity under a low oxygen microenvironment (hypoxia) are rare17-21 but offer a unique mechanism to target tumor cells under such conditions. These hypoxic tumor cells are often the most resistant to radiotherapy22,23 and chemotherapy24,25 and the most susceptible towards metastasis,26,27 making this subpopulation a particularly attractive chemotherapeutic target.

We have discovered that the cationic ruthenium dimer, [(phen)2Ru(tatpp)Ru(phen)2]4+ (P4+) (tatpp = 9,11,20,22 -tetraazatetrapyrido[3,2-a: 2′,3′-c: 3″,2″-1: 2‴,3‴-n]-pentacene and phen = 1,10-phenanthroline) shown above (water soluble as the chloride salt) not only induces DNA cleavage in the presence of mild reducing agents but shows enhanced activity under anaerobic conditions. The fact that exposure to air attenuates the cleavage activity suggests that ROS are not responsible for the observed cleavage and that such a complex might be useful in targeting cells under hypoxic conditions. Complex P4+ is known to intercalate and bind DNA tightly (Kb 1.1×107 M−1 at 25 mM NaCl).28,29 The strong interaction with DNA is not unusual for this class of cationic complexes and it has a number of structural similarities to many known metallointercalators13,14,30-33 including those that are know to thread their way through the DNA double-helix.34

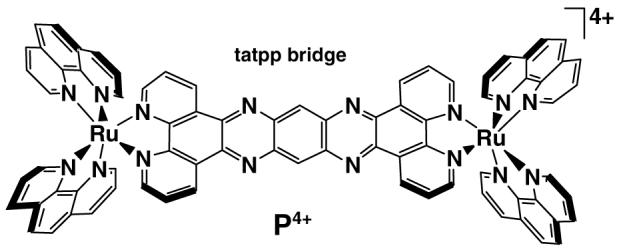

The ability of P4+ to cut DNA was examined by following the conversion of supercoiled plasmid DNA (form I) to the circular form (form II) or linear form (form III) using agarose gel electrophoresis to separate the products (experimental details given in ESI). As shown in Figure 1, P4+ alone does not cause appreciable DNA cleavage (lane 2), however, addition of a mild reducing agent such as glutathione (GSH) leads to cleavage activity (lanes 4 &5). However the yield of cleavage products is clearly higher under anaerobic conditions (compare lane 4 vs lane 5) Yields of cleavage products (Forms II+III) under aerobic and anaerobic conditions are 55 % and 97 %, respectively.35 The appearance of linear DNA in lane 5 appears to result from sequential ss cuts, not ds cleavage, thus the overall cleavage activity is single-strand (ss) sission.

Figure 1.

Cleavage of supercoiled pUC18 DNA (0.154 mM) by P4+ in 7 mM Na3PO4 buffer (pH 7.0) at 25°C. Lane M, marker lane containing Form I, II and III DNA; lane 1, DNA control; lane 2, DNA + P4+ (0.0128 mM); lane 3, DNA + GSH (0.513 mM); lane 4, DNA + GSH (0.256 mM) + P4+ (0.0128 mM) under aerobic conditions; lane 5, same as lane 4 under anaerobic conditions; lane 6, DNA + GSH (0.512 mM) + Fe-Blm (0.0128 mM) under aerobic conditions; lane 7, same as lane 6 under anaerobic conditions. Incubation time for all these cases was limited for 1 hour.

Given the importance of excluding trace O2 as playing a role in the observed cleavage activity, a positive control was included. Under anaerobic conditions, Iron(II)-Bleomycin (Fe-Blm) is known to induce DNA nicks but not ds cuts. When exposed to O2, however, Fe-Blm is an effective ds-nuclease.36-38 As seen in Figure 1, lane 6, Fe-Blm in the presence of O2 causes extensive DNA-ds breaks whereas when O2 was excluded (lane 7), only ss nicking is observed. These studies were carried out side by side with the P4+ cleavage experiments demonstrating unequivocally that P4+ is a more effective DNA cleaving agent under reducing and hypoxic conditions. Due to the known photoreactivity of P4+, all experiments were conducted in the dark so that photochemically induced cleavage reactions could be ruled out. All cleavage experiments were conducted under low light conditions as P4+ is known to be photoactive under some conditions.39-41 Control experiments conducted in the dark or under ambient laboratory lighting gave identical results, showing that this cleavage reaction is not a photochemical reaction.

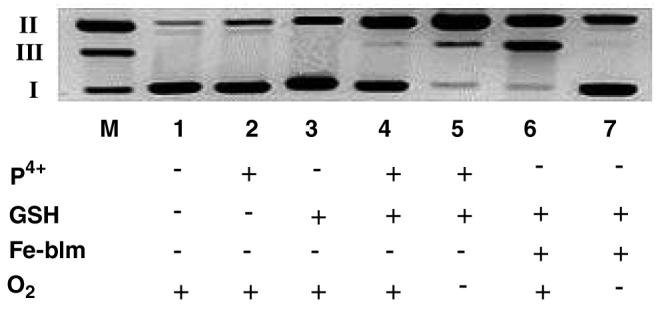

We have previously examined the redox chemistry of P4+ in water at various pH's by electrochemical, spectroelectrochemical and chemical reduction methods.39-41 Reaction 1 shows the two reduction products of P4+ in water at pH 7.0. The redox reactions are reversible and easily followed by visible spectroscopy as distinct changes in the absorption spectrum are observed for each reduction and protonation event. It is readily apparent that GSH reacts with P4+ as the solution color changes from yellow to green

| (1) |

upon addition of the GSH. As seen in Figure 2, the absorption spectra of P4+ in aqueous buffer (pH 7.0) after addition of GSH is identical to that of H2P4+ as prepared by stoichiometric reduction and protonation or electrochemically.40,42 Thus, it appears that P4+ is a prodrug, which is converted to the H2P4+ by in situ reduction.

Figure 2.

Absorption spectra of P4+ (12.8 μM) before (solid line) and after (dotted line) addition of 10 equiv. GSH in anaerobic 7 mM Na3PO4 buffer (pH 7.0). Dashed line is the absorption spectrum of H2P4+ in MeCN when prepared by stioichiometeric cobaltocene reduction and trifluoroacetic acid protonation.42

In order to identify the chemical species responsible for the observed anaerobic cleavage and to rule out participation by glutathyl radical species, we examined the cleavage activity of the P4+, P3+ and H2P4+(see ESI for synthetic procedures) under anaerobic conditions without GSH present.40,42

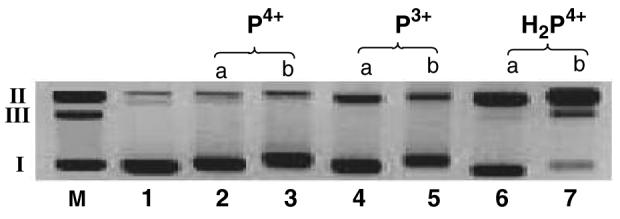

As seen in Figure 3, P4+ does not induce appreciable DNA cleavage under aerobic or anaerobic conditions (lanes 2 and 3). P3+ (lanes 4 and 5) does show some enhanced nicking ability, however, H2P4+ is clearly the most potent nicking agent (lanes 6 and 7). As seen in lanes 6 and 7 (Figure 3), the amount of DNA cleavage increases with increased [H2P4+] as would expected if this complex is the actual cleaving agent. Thus one simple explanation for the attenuated cleaving activity under aerobic conditions would be reoxidation of H2P4+ to P4+. Exposure of an aqueous solution of H2P4+ to air is known to result in a rapid reoxidation of this complex to P4+, as measured by UV-visible absorbtion spectroscopy.39

Figure 3.

Agarose gel of supercoiled pUC18 DNA (0.154 mM) in the presence of P4+, P3+ and H2P4+. All incubations were performed under anaerobic conditions with an incubation time of 2 h at 25°C. The ratio of complex to DNA-bp was (a) 0.083 or (b) 0.20 as indicated above each lane. Lane M, marker; lane 1, DNA control; lane 2, DNA + P4+ (0.0128 mM); lane 3, DNA + P4+ (0.0307 mM), lane 4, DNA + P3+ (0.0128 mM); lane 5, DNA + P3+ (0.0307 mM), lane 6, DNA + H2P4+ (0.0128 mM); lane 7, DNA + H2P4+ (0.0307 mM).

The mechanism of DNA cleavage is still unclear, however Yamaguchi and coworkers have shown that dihydropyrazines cleave DNA by both oxygen dependent and independent pathways.43-46 H2P4+ contains the dihydropyrazine substructure and thus could function in a similar manner with the high DNA binding affinity further enhancing its activity. For dihydropyrazines, the oxygen independent cleavage activity is attributed to the formation of a carbon-based radical on the drihydropyrazine moiety. Thus, we speculate that DNA bound H2P4+ is cleaving DNA in a similar manner via the generation of reactive carbon-based radicals that are in close proximity to the DNA due to the tight DNA binding.

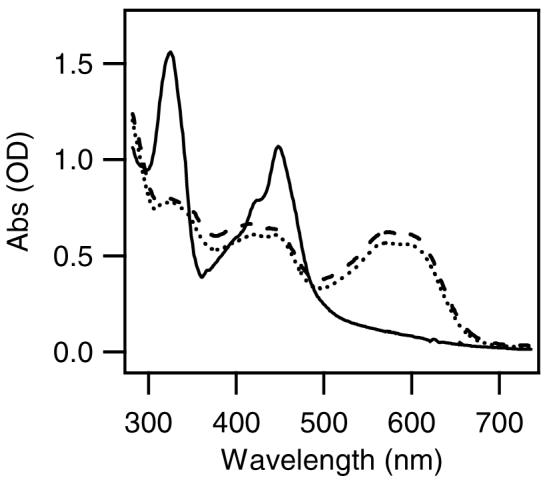

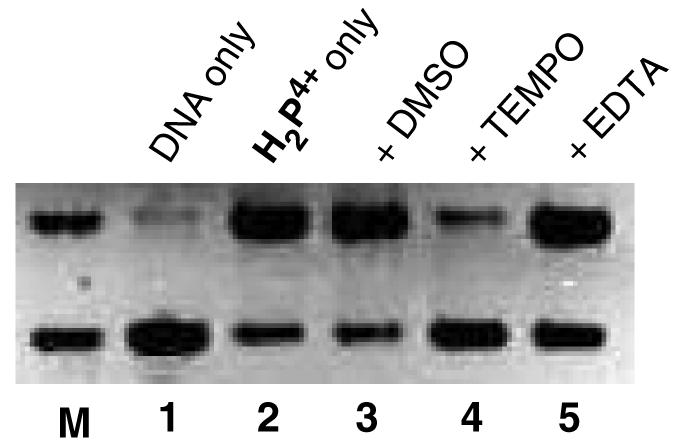

To test, this hypothesis, the cleavage activity of H2P4+ was examined in the presence of various radical trapping and metal complexing reagents. DMSO is an effective scavenger of diffusible oxygen-based radicals such as .OH, and superoxide.47,48 On the other hand, TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperdinyloxy) is an effective scavenger of carbon radicals or metal-based radicals but ineffective with oxygen-based radicals.49,50 As seen in Figure 3, addition of up to 5% DMSO by volume has no effect on the cleavage activity (lane 3) whereas addition of 2 mM TEMPO stops most of the DNA cleavage (lane 4). This data clearly supports the role of carbon-based radicals in the cleavage mechanism. Yamaguchi and coworkers postulated that trace metals ions, such as Cu2+, activated the dihydropyrazines to the reactive form.43-46 This does not seem to be the case here as added EDTA, at concentrations up to 1 mM, has little effect on the cleavage activity (Figure 4, lane 5) of H2P4+. We are further investigating this unusual behavior and hope to elucidate the cleavage mechanism with the help of EPR spectroscopy. We note that the carbon-based radical species would likely be very reactive towards O2 in solution and this ‘quenching’ reaction could also explain the observed sensitivity of this cleavage activity to oxygen.

Figure 4.

Agarose gel of supercoiled pUC18 DNA (0.154 mM) in the presence of H2P4+ (0.0256 mM). All incubations were performed in 7mM Na3PO4 buffer (pH 7.0) at 250C under anaerobic conditions with an incubation time of 2 h. The ratio of complex to DNA-bp was 0.16. Lane M, marker lane containing Form I and II DNA; lane 1, DNA control; lane 2, DNA + H2P4+; lane 3, DNA + H2P4++ DMSO (0.64 M); lane 4, DNA + H2P4+ + TEMPO (2.04 mM); lane 5, DNA + H2P4+ + EDTA (1.02 mM).

It is interesting to observe that the loading of P4+ onto the DNA in the following studies (ranging from 1 complex per 12 DNA-bp to 5 complexes per DNA-bp) is relatively low compared to many metal-based DNA cleaving agents. In fact, the [Fe Blm] used in the cleavage experiment shown in Figure 1 was purposefully kept the same as the [P4+] in the same experiment. As can be seen, the cleavage activity of P4+ under reducing, anaerobic conditions is comparable with Fe-Blm under aerobic conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first example of a metal complex with potentiated DNA cleavage activity under hypoxic conditions, suggesting potential therapeutic applications. Future studies will establish the mode of action and it effects on tumor cells in vitro.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Sanjay Awasthi for useful discussions and acknowledge the NIH (R15 CA113747-01A) and Robert A. Welch Foundation for financial support.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE Procedures for the DNA cleavage assay and synthetic methods for preparation of [P][Cl]3 and [H2P][Cl]4 (one page). Absorption spectrum of GSH reduced P4+ (one page).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wong E, Giandomenico M. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:2451–2466. doi: 10.1021/cr980420v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.N. Farrell. Comp.Coord. Chem. II. 2004;9:809–840. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke MJ. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003;236:207–231. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blower PJ. Ann. Rep. Prog. Chem., Sec A. 2002;98:615–633. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norden B, Lincoln P, Akerman B, Tuite E. Metal ions in biological systems. 1996;33:177–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long EC, Barton JK. Acc. Chem. Res. 1990;23:273–279. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorp HH. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polymers. 1993;3:41–57. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigman DS, Mazumder A, Perrin DM. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:2295–2316. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadler PJ, Guo Z. Pure Appl. Chem. 1998;70:863–871. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu K-LP, Bradley PM, Turro C. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:2476. doi: 10.1021/ic010118w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu PKL, Bradley PM, van Loyen D, Duerr H, Bossmann SH, Turro C. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:3808–3810. doi: 10.1021/ic020136t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holder AA, Swavey S, Brewer KJ. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:303–308. doi: 10.1021/ic035029t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elias B, Kirsch-De Mesmaeker A. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006;250:1627–1641. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierard F, Kirsch-De Mesmaeker A. Inorg. Chem. Comm. 2006;9:111–126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta N, Grover N, Neyhart GA, Singh P, Thorp HH. Inorg. Chem. 1993;32:310–316. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta N, Grover N, Neyhart GA, Liang W, Singh P, Thorp HH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1992;31:1048–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown JM. Drug Resistance Updates. 2000;3:7–13. doi: 10.1054/drup.2000.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy KA. Anticancer Drug Res. 1987;2:181–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denny WA, Wilson WR. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2000;9:2889–2901. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.12.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denny WA. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2001;36:577–595. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(01)01253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson LH, McKeown SR. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;83:1589–1593. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatenby RA, Kessler HB, Rosenblum JS, Coia LR, Moldofsky PJ, Hartz WH, Broder GJ. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1988;14:831–838. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(88)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hockel M, Knoop C, Schlenger K, Vorndran B, Baubmann E, Mitze M, Knapstein PG, Vaupel P. Radiother. Oncol. 1993;26:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sartorelli AC. Cancer Res. 1988;48:775–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tannock I, Guttman P. Br. J. Cancer. 1981;42:245–248. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1981.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundfor K, Lyng H, Rofstad EK. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;78:822–827. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Røfstad EK, Danielson T. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;80:1697–1707. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajput C, Rutkaite R, Swanson L, Haq I, Thomas JA. Chem. Eur. J. 20096;12:4611–4619. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eriksson M, Mehmedovic M, Westman G, Akerman B. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:524–532. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradley PM, Angeles-Boza AM, Dunbar KR, Turro C. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:2450–2452. doi: 10.1021/ic035424j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Che C-M, Yang M, Wong K-H, Chan H-L, Lam W. Chem. Eur. J. 1999;5:3350–3356. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erkkila KE, Odom DT, Barton JK. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:2777–2795. doi: 10.1021/cr9804341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lincoln P, Norden B. Chem. Comm. 1996;18:2145–2146. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onfelt B, Lincoln P, Norden B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3630–3637. doi: 10.1021/ja003624d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.note dna densiometry.

- 36.Sausville EA, Peisach J, Horwitz SB. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1976;73:814–822. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90882-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lown JW, Sim S. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1977;77:1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(77)80099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi T, Guo LL, Nishida Y. Zeitschrift fuer Naturforschung, C: Biosciences. 1998;53:867–870. doi: 10.1515/znc-1998-9-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Tacconi NR, Lezna RO, Konduri R, Ongeri F, Rajeshwar K, MacDonnell FM. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:4327–4339. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Konduri R, de Tacconi NR, Rajeshwar K, MacDonnell FM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11621–11629. doi: 10.1021/ja047931l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Konduri R, Ye H, MacDonnell FM, Serroni S, Campagna S, Rajeshwar K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3185–3187. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3185::AID-ANIE3185>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Tacconi NR, Lezna RO, Konduri R, Ongeri F, Rajeshwar K, MacDonnell FM. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:4327–4329. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi T, Nomura H, Matsunaga K, Ito S, Takata J, Karube Y. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003;26:1523–1527. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamaguchi T, Matsumoto S, Watanabe K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:8311–8312. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamaguchi T, Kashige N, Mishiro N, Miake F, Watanabe K. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1996;19:1261–1265. doi: 10.1248/bpb.19.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamaguchi T, Eto M, Harano K, Kashige N, Watanabe K, Ito S. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:675–686. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tu C, Shao Y, Gan N, Xu Q, Guo Z. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:4761–4766. doi: 10.1021/ic049731g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ren R, Yang P, Zheng W, Hua Z. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:5454. doi: 10.1021/ic0000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Connolly TJ, Baldový´ MV, Mohtath N, Scaiano JC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:4919–4922. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohler DL, Downs JR, Hurley-Predecki AL, Sallman JR, Gannett PM, Shi X. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:9093–9102. doi: 10.1021/jo050338h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.