Abstract

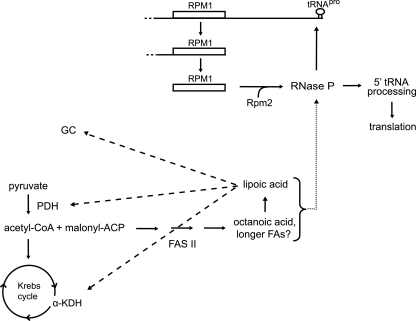

Distinct metabolic pathways can intersect in ways that allow hierarchical or reciprocal regulation. In a screen of respiration-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene deletion strains for defects in mitochondrial RNA processing, we found that lack of any enzyme in the mitochondrial fatty acid type II biosynthetic pathway (FAS II) led to inefficient 5′ processing of mitochondrial precursor tRNAs by RNase P. In particular, the precursor containing both RNase P RNA (RPM1) and tRNAPro accumulated dramatically. Subsequent Pet127-driven 5′ processing of RPM1 was blocked. The FAS II pathway defects resulted in the loss of lipoic acid attachment to subunits of three key mitochondrial enzymes, which suggests that the octanoic acid produced by the pathway is the sole precursor for lipoic acid synthesis and attachment. The protein component of yeast mitochondrial RNase P, Rpm2, is not modified by lipoic acid in the wild-type strain, and it is imported in FAS II mutant strains. Thus, a product of the FAS II pathway is required for RNase P RNA maturation, which positively affects RNase P activity. In addition, a product is required for lipoic acid production, which is needed for the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase, which feeds acetyl-coenzyme A into the FAS II pathway. These two positive feedback cycles may provide switch-like control of mitochondrial gene expression in response to the metabolic state of the cell.

Intersections of biological pathways previously thought to be distinct have emerged recently from genome-wide functional screens in model organisms (52, 62, 63). Through a genome-wide screen of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we have discovered the intersection of mitochondrial type II fatty acid synthesis (FAS II) with mitochondrial RNA processing.

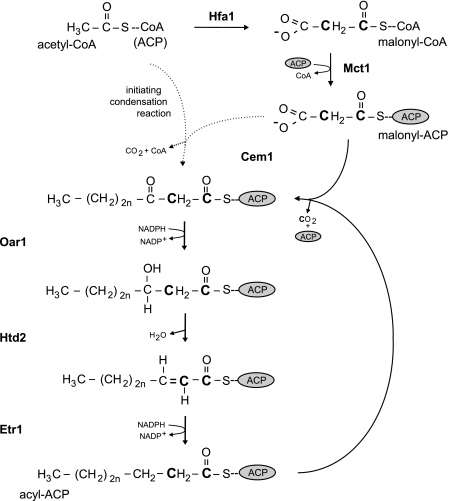

There are two distinct fatty acid synthesis pathways in eukaryotes. Fatty acid synthesis type I (FAS I) is catalyzed by cytosolic multifunctional enzyme complexes that produce the bulk of fatty acids in the cell (45). FAS II occurs in mitochondria and chloroplasts (as well as in prokaryotes) and is catalyzed by the sequential action of individual enzymes (21, 51). The mitochondrial FAS II pathway produces octanoic acid, which is the precursor molecule for the synthesis of lipoic acid. Lipoic acid is the “swinging arm” cofactor that serves to shuttle reaction intermediates between the active sites of several mitochondrial keto acid dehydrogenase complexes (35). In yeast, lipoic acid is covalently bound to conserved lysine residues on three different proteins, the E2 subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) (34) and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KDH) (38) and on the H protein of the glycine cleavage enzyme (GC) (33).

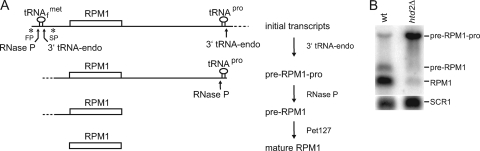

Mitochondrial genes are expressed through a coordinated effort between the nuclear and the mitochondrial genomes. Mitochondrial DNA in eukaryotes encodes a small number of proteins that are components of the respiratory chain complexes and ATP synthase, as well as mitochondrial rRNAs and most tRNAs (1, 15). Other proteins required for mitochondrial function are encoded on nuclear chromosomes, translated in the cytoplasm, and imported into the organelle (2). Mitochondrial genes are most often expressed in multigenic units, and the initial transcripts are processed to produce mature RNAs (10, 54). Mitochondrial tRNAs are cleaved from the initial multigenic transcripts by tRNA 3′ endonuclease (8, 31) and mitochondrial RNase P, which processes the 5′ leader sequences of tRNAs (16, 57). In yeast, mitochondrial RNase P is composed of nuclearly encoded Rpm2 protein (30) and mitochondrially encoded RPM1 RNA (55). As illustrated in Fig. 1A, RPM1 is transcribed either from the FP promoter with the upstream  and the downstream tRNAPro or from the SP promoter with only tRNAPro (49). Following tRNA removal, the 5′ extension sequence of RPM1 is processed in a Pet127-dependent reaction (12), and the 3′ end is processed either by the Dss1/Suv3 3′-to-5′ exonuclease (11) and/or by other enzymes not yet characterized. Because the production of mature RPM1 RNA requires the activity of a variety of mitochondrial RNA processing factors, including RNase P itself, RPM1 processing provides a good model for the study of mitochondrial RNA metabolism.

and the downstream tRNAPro or from the SP promoter with only tRNAPro (49). Following tRNA removal, the 5′ extension sequence of RPM1 is processed in a Pet127-dependent reaction (12), and the 3′ end is processed either by the Dss1/Suv3 3′-to-5′ exonuclease (11) and/or by other enzymes not yet characterized. Because the production of mature RPM1 RNA requires the activity of a variety of mitochondrial RNA processing factors, including RNase P itself, RPM1 processing provides a good model for the study of mitochondrial RNA metabolism.

FIG. 1.

Processing of RPM1-containing transcripts. (A) RPM1 is transcribed in a single transcription unit with both upstream  and downstream tRNAPro from the FP promoter (5′ end represented by *FP) or with only the downstream tRNAPro from the SP promoter (5′ end represented by *SP). 3′ tRNA endonuclease generates the high-molecular-weight precursor termed pre-RPM1-pro. The 5′ end of the precursor transcript is produced either by the SP promoter or by cleavage at the 3′ end of

and downstream tRNAPro from the FP promoter (5′ end represented by *FP) or with only the downstream tRNAPro from the SP promoter (5′ end represented by *SP). 3′ tRNA endonuclease generates the high-molecular-weight precursor termed pre-RPM1-pro. The 5′ end of the precursor transcript is produced either by the SP promoter or by cleavage at the 3′ end of  . The interval between the position of the SP promoter and

. The interval between the position of the SP promoter and  is indicated by a dotted line. RNase P processes the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA at the 5′ end of tRNAPro, generating the pre-RPM1 intermediate. Further processing at the 5′ end of this intermediate in a Pet127-dependent reaction produces mature RPM1 RNA. (B) A Northern blot of total RNA extracted from the wild-type (wt) and htd2Δ strains was hybridized with a probe complementary to RPM1. A probe complementary to SCR1, the RNA subunit of the cytoplasmic signal recognition particle, was used as a loading control.

is indicated by a dotted line. RNase P processes the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA at the 5′ end of tRNAPro, generating the pre-RPM1 intermediate. Further processing at the 5′ end of this intermediate in a Pet127-dependent reaction produces mature RPM1 RNA. (B) A Northern blot of total RNA extracted from the wild-type (wt) and htd2Δ strains was hybridized with a probe complementary to RPM1. A probe complementary to SCR1, the RNA subunit of the cytoplasmic signal recognition particle, was used as a loading control.

Here, we describe and analyze the unexpected finding that the deletion of any gene in the mitochondrial FAS II pathway results in inefficient 5′ processing of precursors containing tRNAs by RNase P (Fig. 1A). A model is presented for the regulation of mitochondrial gene expression by cellular catabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

S. cerevisiae strains and their genotypes are listed in Table 1. The deletions in the strains of interest in the EUROSCARF collection (http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/fb15/mikro/euroscarf/) were verified by PCR using a gene-specific 5′ upstream primer and a kanamycin resistance gene 3′ primer. Cells were grown in medium containing 1% (wt/vol) yeast extract, 2% (wt/vol) peptone, and 2% (wt/vol) glucose (YEPD) or 3% glycerol (YEPG) instead of glucose. Solid media contained 2% (wt/vol) agar.

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| MY6/[rho0] | MATα [rho0] lys1 | This study |

| BY4741 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | EUROSCARF |

| cbp2Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cbp2::kanMX4 | This study |

| hfa1Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hfa1::kanMX4 | This study |

| mct1Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 mct1::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| cem1Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cem1::kanMX4 | This study |

| oar1Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 oar1::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| htd2Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 htd2::kanMX4 | This study |

| etr1Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 etr1::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| pet127Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 pet127::kanMX4 | This study |

| htd2Δ pet127Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 htd2::kanMX4 pet127::LEU2 | This study |

| lpd1Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 lpd1::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| lat1Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 lat1::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| kgd2Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 kgd2::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| gcv3Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 gcv3::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| Rpm2-GFP wild type | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 RPM2-GFP::HIS3 | 23 |

| Rpm2-GFP cbp2Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cbp2::kanMX4 RPM2-GFP::HIS3 | This study |

| Rpm2-GFP htd2Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 htd2::kanMX4 RPM2-GFP::HIS3 | This study |

Genomic screen.

The ∼5,000 EUROSCARF nonessential yeast deletion strains were plated on YEPD and YEPG media and grown at 18°C, 24°C, 30°C, and 37°C. Of the 266 respiration-deficient strains that were found, 181 strains that harbored deletions of well-studied genes were not followed, while 85 that harbored deletions of uncharacterized open reading frames (ORFs) were further analyzed (YHR067w was uncharacterized at the time the screen was done). The results from our screen were similar to those of other screens that have been performed in search of nuclearly encoded mitochondrial factors (215 respiration-deficient strains [54] and 214 strictly respiration-deficient strains out of 466 with respiratory growth deficiencies [46]). The 85 strains that remained in our study were checked for their ability to maintain mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) by mating them to the MY6 tester strain, which lacks mtDNA ([rho0]). Resulting heterozygous diploids were respiration competent if they contained wild-type mtDNA or were respiration deficient if they had mutations in or sustained loss of mtDNA. Strains with wild-type mtDNA were surveyed for mitochondrial RNA processing defects by Northern blotting. Oligonucleotide probes complementary to the ATP8/6, ATP9, COB, COX1, COX2, COX3, and VAR1 mRNAs, the 15S and 21S rRNAs, and the RPM1 RNA were used.

Disruption of ORFs.

The HTD2, CEM1, CBP2, HFA1, and PET127 genes were deleted in BY4741 to confirm the phenotypes of the EUROSCARF strains. Each ORF was deleted by homologous recombination with the kanamycin resistance (kanMX4) cassette. The htd2Δ::kanMX4, cbp2Δ::kanMX4, hfa1Δ::kanMX4, and pet127Δ::kanMX4 constructs were generated by amplification of the kanMX4 cassette, using the corresponding primers listed in Table 2. The PCR products were gel purified and transformed into the wild-type strain, using the lithium acetate method (17), followed by selection for kanamycin resistance. The Rpm2-green fluorescent protein (GFP) cbp2Δ and Rpm2-GFP htd2Δ strains were made by transformation of the Rpm2-GFP wild-type strain (23). The cem1Δ::kanMX4 construct was generated by amplification of the kanMX4 cassette, using the CEM1-5′kan and CEM1-3′kan primers (Table 2), which are complementary to both the CEM1 untranslated regions and the kanMX4 cassette. The resulting PCR product was transformed into the wild-type strain, using the same method as mentioned above. To make the htd2Δ pet127Δ double-deletion strain, the PET127 ORF was amplified by PCR using the PET127-up and PET127-down primers and ligated to the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The LEU2 gene from the plasmid pUC18/LEU2 was digested with XbaI and XmaI and ligated to the NheI and AgeI sites in the PET127 ORF. The pet127::LEU2 construct was digested with NotI, and the gel-purified fragment was transformed into the htd2Δ::kanMX4 strain followed by selection for growth on plates lacking leucine.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide probes and primers used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Probe | Sequence 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|

| Probea | ||

| RPM1 | 3 | ACTTTTTATTAATATATATATATGGACTCCTGCGGGG |

| tRNAfMet | 1 | GCAATAATACGATTTGAACG |

| tRNAPro | 5 | AAGAAAGCGCCTGACCTTTTG |

| 5′ junction | 2 | ATAATATAAATATCTTATTCAAATTAAT |

| 3′ junction | 4 | AAATTAATTATGAATATGGATATTATATT |

| tRNAGlu | AGGTGATGTCGTAACCATTAGACG | |

| tRNASer | ATCACACTTTAAACCACTCAGTCAAC | |

| SCR1 | GTCTAGCCGCGAGGAAGG | |

| Primer | ||

| CEM1-5′kan | CTGTCCTCGGTGTTGCCTAATTTTAAATTAAAGATCATTTCTTTACGATGTCCACGAGGTC | |

| CEM1-3′kan | TTAAGTTTTTGCTAATATTACCCTATATATATATTCAAATTATTATAATCGGTGTCGGTCTCG | |

| HTD2-A | CTTTTAAATCATAGCCCAAA | |

| HTD2-B | CACCTTTTTTTCAGTTCTTC | |

| CBP2-A | ATAAGACAGTTCATTGTGGCA | |

| CBP2-B | AAAGGAAAGAGTGAAGATTGC | |

| HFA1-A | ATGAGATCTATAAGAAAATGGGC | |

| HFA1-B | CTATCTCTTTCGCTTACTGTCC | |

| PET127-A | TCATCTTTGAGTATATCACGTC | |

| PET127-B | CATAATATGTACCAAGGGACT | |

| PET127-up | CAGGGCACTTGAGAGAGCAC | |

| PET127-down | CCCAACGCTGACTACTGTCT |

Probes are antisense.

The hfa1Δ mutation reported by Hoja et al. (22), which was made in a different strain background, causes a very-slow-growth phenotype on glycerol. Since the mutation had little effect on respiratory growth at 30°C in our strain, the deletion was made anew in the BY4741 (S288C derivative) strain and confirmed that our strain truly displayed a conditional phenotype on rich glycerol medium.

Isolation of whole-cell RNA.

Total RNA was isolated from mid-logarithmic cultures after they were grown in liquid YEPD medium at 30°C or 37°C as described previously (7).

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA (10 or 30 μg) was separated on a 1.2% (wt/vol) agarose gel (a 2% agarose gel was used for tRNA analysis) in TB buffer (83 mM Tris base, 89 mM boric acid [pH 8.3]). The RNAs were transferred onto a Nytran membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) overnight in 20× SSC ([1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] 3 M sodium chloride, 0.3 M sodium citrate [pH 7.0]) and hybridized (6× SSC, 10× Denhardt's solution, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 50 μg/ml carrier DNA) overnight at 5 to 10°C below the melting temperature of the oligonucleotide probes. All blots were stripped and hybridized with the SCR1 loading control probe. Oligonucleotide probes (listed in Table 2) were 32P end labeled using T4 DNA kinase (Fermentas, Hanover, MD). Blots were analyzed on a PhosphorImager (Typhoon 9410; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Isolation and fractionation of mitochondria.

Cells were grown to stationary phase in YEPD medium at 30°C. Mitochondria were prepared as described previously (13), except that zymolyase 20T (Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan) was used instead of glusulase to produce spheroplasts. Mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.5]) containing protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A). For Western blots, Laemmli sample buffer was added to the resuspended mitochondrial pellets. For immunoprecipitations, the mitochondrial pellets were sonicated 10 times for 10 s each at 35% output (Fisher sonic Dismembrator model 300). The mitochondrial matrix and membrane fractions were separated by ultracentrifugation for 30 min at ∼100,000 × g in a TLA 100.3 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) at 4°C. Mitochondrial matrix supernatants were frozen at −20°C until used.

Western blot analysis.

Approximately 40 μg of mitochondrial protein was resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, following the protocol described by Laemmli (27). Proteins were transferred onto BioTrace polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Pall, Pensacola, FL) at 22 V overnight in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris base [pH 8.3], 200 mM glycine, 2% methanol, 0.01% SDS). The blots were preincubated in low-salt buffer (150 mM NaCl, 40 mM Tris base [pH 8.0], 0.05% Tween 20) containing 5% (wt/vol) non-fat dried milk for 1 h. For visualization of lipoylated proteins, the blots were reacted with anti-lipoic acid polyclonal antibody (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) diluted 1:7,500 in a 1% milk solution in low-salt buffer. Secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was diluted 1:5,000. Proteins were visualized using an ECL (Pierce) substrate. For visualization of Rpm2-GFP, the blots were reacted with anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (Covance, Berkeley, CA) diluted 1:2,000. Secondary antibody conjugated to HRP (Pierce) was diluted 1:5,000. Proteins were visualized using SuperSignal Pico and Femto chemiluminescent substrates at a 70:30 ratio (Pierce). Anti-isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) antiserum (a gift from Lee McAlister-Henn, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) was used as a loading control at a 1:500 dilution. Secondary antibody conjugated to HRP (Pierce) was diluted 1:5,000, and proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence. Prestained Rainbow molecular marker proteins (GE Healthcare) were used to estimate relative molecular mass.

Light microscopy.

Strains were grown overnight in YEPD medium, diluted, and grown until mid-logarithmic phase. MitoTracker Red dye (CMXRos; Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added 45 min before the cells were harvested by centrifugation. The harvested cells were washed in minimal medium, and the C-terminally tagged Rpm2-GFP chimera was localized by directly viewing the fluorescence signal through a GFP-optimized filter, using a Leica DM-RXA microscope equipped with a mercury-xenon light source. Images were captured by a Retiga EX digital camera (Q Imaging, Surrey, BC, Canada) and processed using Metamorph 6.0 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Immunoprecipitation.

Protein A-Sepharose (0.2 mg) was washed three times in wash buffer (150 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], and 0.1% Triton X-100). All subsequent steps were done at 4°C. The mitochondrial matrix fraction (∼3.5 mg of protein) was brought to a 500-μl volume in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (150 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitors as listed above). The sample was added to the protein A-Sepharose beads for 3 h at 4°C to preclear the supernatant. The beads were centrifuged, the sample was moved to a new tube containing newly washed protein A-Sepharose beads, and polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (Molecular Probes) was added at a 1:200 dilution. The tube was rotated at 4°C overnight. After centrifugation, the immunoprecipitation supernatant was collected, and proteins were precipitated in 10% trichloroacetic acid (VWR, West Chester, PA) and 80% acetone. The beads were washed twice in IP buffer for 30 s and twice for 15 min each at 4°C, once in IP buffer without detergent for 30 s, and once in IP buffer without detergent or salt for 30 s. One hundred microliters of 1× loading buffer were added to the beads, which were then boiled for 5 min at 100°C. Thirty percent of the immunoprecipitated and trichloroacetic acid-precipitated protein was resolved on a 7 to 17% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel and blotted as described above.

RESULTS

Mitochondrial pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA accumulates in the htd2Δ strain.

In an effort to uncover novel nuclearly encoded factors involved in mitochondrial RNA processing in yeast, the EUROSCARF haploid deletion strains (Frankfurt, Germany) were screened for respiratory deficiency (inability to grow on rich glycerol medium [see Materials and Methods]). Mutants that maintained stable mitochondrial genomes were then surveyed for mitochondrial RNA processing defects by Northern blotting using probes specific for each of the mitochondrial multigenic transcripts. Hybridization of the Northern blots with a probe specific for RPM1, the RNA component of mitochondrial RNase P, revealed accumulation of the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA and lower levels of the pre-RPM1 intermediate and of the mature RPM1 in the yhr067wΔ strain (Fig. 1B). YHR067w encodes a 3-hydroxyacyl thioester dehydratase 2 (Htd2) enzyme in the mitochondrial FAS II pathway (25). This finding suggested a novel connection between an enzyme in the fatty acid synthesis pathway, or the pathway itself, and mitochondrial RNA processing.

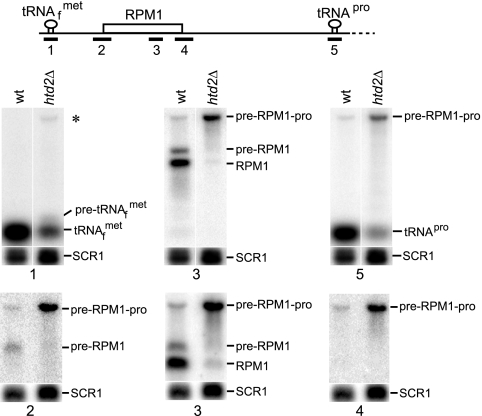

Production of mature RPM1 RNA requires processing of  from the 5′ end of the initial multigenic transcript by 3′ tRNA endonuclease and processing of tRNAPro from the 3′ end of the transcript by RNase P (Fig. 1A). Following tRNA processing, the resulting transcript is trimmed at the 5′ and 3′ ends. To analyze the unprocessed sequences of the high-molecular-weight pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA in the htd2Δ strain, Northern blots were hybridized with five probes complementary to different regions of the transcript (Fig. 2). Hybridization with a tRNAPro-specific probe confirmed that the pre-RPM1-pro precursor contains unprocessed tRNAPro (Fig. 2, probe 5), which supports the conclusion that RNase P activity is compromised in the htd2Δ strain. Hybridization with a probe complementary to the sequence spanning the mature 5′ end of RPM1 revealed that the pre-RPM1-pro precursor and pre-RPM1 intermediate RNAs also contain 5′ extension sequences, the 5′ ends of which were previously mapped to the SP promoter and the 3′ end of the upstream

from the 5′ end of the initial multigenic transcript by 3′ tRNA endonuclease and processing of tRNAPro from the 3′ end of the transcript by RNase P (Fig. 1A). Following tRNA processing, the resulting transcript is trimmed at the 5′ and 3′ ends. To analyze the unprocessed sequences of the high-molecular-weight pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA in the htd2Δ strain, Northern blots were hybridized with five probes complementary to different regions of the transcript (Fig. 2). Hybridization with a tRNAPro-specific probe confirmed that the pre-RPM1-pro precursor contains unprocessed tRNAPro (Fig. 2, probe 5), which supports the conclusion that RNase P activity is compromised in the htd2Δ strain. Hybridization with a probe complementary to the sequence spanning the mature 5′ end of RPM1 revealed that the pre-RPM1-pro precursor and pre-RPM1 intermediate RNAs also contain 5′ extension sequences, the 5′ ends of which were previously mapped to the SP promoter and the 3′ end of the upstream  (Fig. 2, probe 2) (49). These results show that the htd2Δ mutation has two effects on the processing of the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA: inefficient cleavage of tRNAPro by RNase P and impaired trimming of the 5′ end of the transcript.

(Fig. 2, probe 2) (49). These results show that the htd2Δ mutation has two effects on the processing of the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA: inefficient cleavage of tRNAPro by RNase P and impaired trimming of the 5′ end of the transcript.

FIG. 2.

The initial RPM1-containing transcript is shown with the position of the probes used for Northern blot analysis. A Northern blot of total RNA extracted from the wild-type and htd2Δ strains was hybridized with a probe complementary to  (upper panel, probe 1). The asterisk denotes a high-molecular-weight pre-met-RPM1-pro RNA, which contains unprocessed

(upper panel, probe 1). The asterisk denotes a high-molecular-weight pre-met-RPM1-pro RNA, which contains unprocessed  . pre-

. pre- contains the presumed short-leader sequence, while mature tRNA is labeled

contains the presumed short-leader sequence, while mature tRNA is labeled  . The blot was stripped and probed for RPM1 (probe 3). pre-RPM1-pro and pre-RPM1 are the precursor RNAs, while RPM1 is the mature RNA. The blot was again stripped and probed for tRNAPro (probe 5). Mature tRNA is labeled tRNAPro. A Northern blot of 30 μg of total RNA extracted from the wild-type (wt) and htd2Δ strains was hybridized with a probe complementary to a sequence spanning the mature 5′ end of RPM1 (lower panel, 5′ junction probe, probe 2). The blot was stripped and probed for RPM1 (probe 3). The blot was again stripped and hybridized with a probe complementary to a sequence spanning the mature 3′ end of RPM1 (3′ junction probe, probe 4). The 5′ junction probe and the 3′ junction probe were designed such that hybridization would occur only when both the upstream and the downstream sequences spanning the mature ends were present in the transcript. SCR1 was used as a loading control.

. The blot was stripped and probed for RPM1 (probe 3). pre-RPM1-pro and pre-RPM1 are the precursor RNAs, while RPM1 is the mature RNA. The blot was again stripped and probed for tRNAPro (probe 5). Mature tRNA is labeled tRNAPro. A Northern blot of 30 μg of total RNA extracted from the wild-type (wt) and htd2Δ strains was hybridized with a probe complementary to a sequence spanning the mature 5′ end of RPM1 (lower panel, 5′ junction probe, probe 2). The blot was stripped and probed for RPM1 (probe 3). The blot was again stripped and hybridized with a probe complementary to a sequence spanning the mature 3′ end of RPM1 (3′ junction probe, probe 4). The 5′ junction probe and the 3′ junction probe were designed such that hybridization would occur only when both the upstream and the downstream sequences spanning the mature ends were present in the transcript. SCR1 was used as a loading control.

The mitochondrial FAS II pathway is required for efficient processing of pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA.

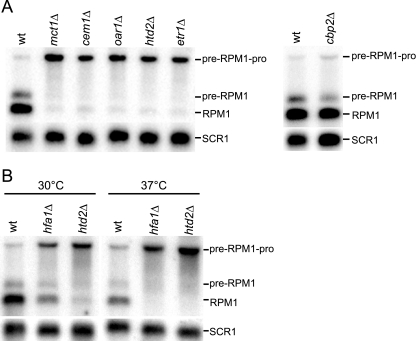

We determined whether the defect in the processing of pre-RPM1-pro RNA by RNase P was specific to a deletion of HTD2 or if a disruption of any enzyme in the FAS II pathway resulted in the same phenotype (Fig. 3 shows details of the FAS II pathway). To answer this question, RNA from mutant strains, each harboring a deletion of a gene encoding a FAS II enzyme, was analyzed by Northern blotting using the RPM1 probe (Fig. 4A). As disruption of the FAS II pathway leads to respiratory deficiency (21, 51), RNA from cbp2Δ, which is defective in COB mRNA intron processing (29), was also analyzed as a control for a general effect of respiratory deficiency on tRNA processing. The Northern blots revealed that a deletion of any of the FAS II pathway genes led to decreases in the mature RPM1 RNA and the pre-RPM1 intermediate, as well as an increase in accumulation of the pre-RPM1-pro precursor transcript compared to that of the wild-type and cbp2Δ strains. Processing of mitochondrially encoded mRNAs or rRNAs was not affected in the mutant strains (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

The mitochondrial FAS II pathway in yeast. Acyl carrier protein (ACP) (6) is depicted as a gray oval. Acetyl-CoA is converted to malonyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Hfa1) (22). The malonyl moiety is transferred onto ACP by malonyl-CoA:ACP transferase (Mct1) (41). Acetyl-CoA (ACP) and malonyl-ACP are condensed by 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (Cem1) to form 3-ketoacyl-ACP (18). It is not known whether acetyl-CoA or acetyl-ACP is utilized in the initiating condensation reaction, which is denoted by dotted arrows. The reduction to 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP is catalyzed by 3-ketoacyl:ACP-reductase (Oar1) (41). The dehydration reaction producing trans-2-enoyl-ACP is catalyzed by 3-hydroxyacyl-thioester dehydratase (Htd2) (25). Trans-2-enoyl-ACP is reduced by 2-enoyl thioester reductase (Etr1) (53). The resulting acyl-ACP molecule is condensed with malonyl-ACP by Cem1, cyclically elongating the acyl chain by two carbon units to produce octanoic acid. It is unclear whether longer fatty acids are produced by the mitochondrial FAS II pathway in yeast. The letter “n” in the acyl chains signifies the number of cycles, with n = 0 representing the product of the initiating condensation reaction. Boldface C's denote the carbon atoms donated by malonyl-CoA in the most recent condensation reaction.

FIG. 4.

Northern analysis of RNase P activity on the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA in FAS II deletion and control strains. Northern blots of total RNA extracted from (A) the FAS II deletion strains (Fig. 3) and cbp2Δ, a respiration-deficient control strain, grown at 30°C, and (B) the hfa1Δ and htd2Δ strains grown at 30°C and 37°C were hybridized with the RPM1 probe. The SCR1 probe was used as a loading control. wt, wild type.

Unlike the FAS II mutant strains shown in Fig. 4A, the hfa1Δ strain exhibited a conditional growth phenotype on respiratory medium. The pre-RPM1-pro RNA was inefficiently processed when hfa1Δ was grown at both the permissive temperature of 30°C and the nonpermissive temperature of 37°C, but processing was more retarded at the higher temperature (Fig. 4B). The fact that a deletion of any of the FAS II pathways genes leads to inefficient removal of tRNAPro indicates that a product of the FAS II pathway is required for efficient processing of the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA by RNase P.

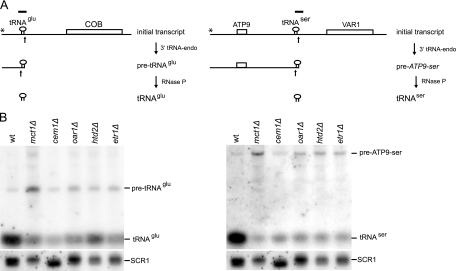

Disruption of the FAS II pathway affects processing of other mitochondrial tRNAs.

Since the action of RNase P on the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA in FAS II mutants is impeded, we examined other RNase P cleavage reactions. tRNAGlu and tRNASer were chosen as examples (10). These two tRNAs are also expressed in large multigenic transcripts (Fig. 5A). tRNA abundance and processing were assessed in the wild-type and FAS II mutant strains by Northern blotting (Fig. 5B). Levels of both mature tRNAGlu and tRNASer were decreased dramatically in the mutant strains, while levels of the precursor RNAs were increased somewhat, though the total of both species was lower than that in the wild type. These data indicate that the FAS II pathway is generally required for efficient cleavage of mitochondrial tRNA 5′ leader sequences by RNase P.

FIG. 5.

Northern analysis of mitochondrial tRNA processing by RNase P in FAS II deletion strains. (A) The primary transcripts containing tRNAGlu and tRNASer are shown as cartoons (5′ ends are represented by asterisks). The positions of the probes used for Northern blot analysis are shown above the transcripts. (B) A Northern blot was hybridized with a tRNAGlu probe, stripped, and hybridized with a tRNASer probe. 3′ tRNA endonuclease generates the precursor transcripts pre-tRNAGlu and pre-ATP9-ser. RNase P processes the 5′ ends of the tRNAs, producing mature tRNAGlu and tRNASer. The asterisks denote transcription start sites. wt, wild type. SCR1 was used as a loading control.

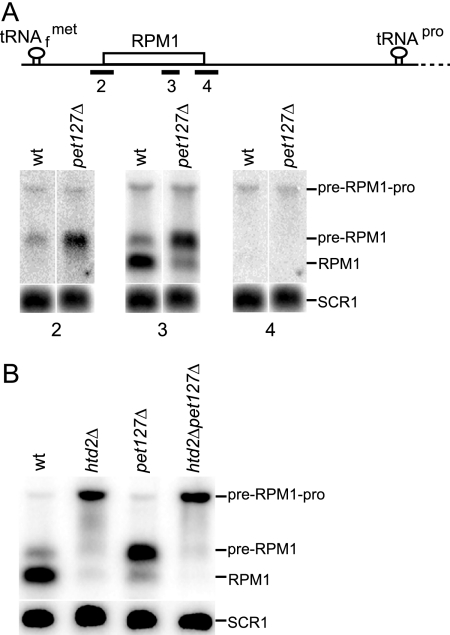

The mitochondrial FAS II pathway is required for efficient 5′ processing of pre-RPM1-pro RNA in a Pet127-driven reaction.

The pre-RPM1-pro precursor, which accumulates in FAS II mutant strains, contains a 5′ end extension sequence (Fig. 1). Thus, 5′ processing of the intermediate in a Pet127-driven reaction that follows the RNase P processing step is severely retarded in these strains. Pet127 is a nuclearly encoded protein that is required for exonucleolytic processing of 5′ end extension sequences of several mitochondrial precursor RNAs (14, 58, 59), including RPM1 (12). Deletion of PET127 causes accumulation of precursor RNAs, as well as temperature-sensitive respiratory deficiency (58). The blockage of this Pet127-dependent reaction in FAS II mutant strains is specific to the pre-RPM1-pro precursor; all other Pet127-dependent processing reactions (e.g., COB, VAR1, and ATP8/6 mRNAs and 15S rRNA) are the same as those in the wild-type strain (data not shown). To analyze the 5′ ends of pre-RPM1-pro and pre-RPM1 RNA in the pet127Δ strain, a Northern blot was hybridized with the RPM1 5′ junction probe (Fig. 6A, probe 2). The probe revealed accumulation of the pre-RPM1 intermediate, which contains a 5′ end extension, in the pet127Δ mutant compared to the wild-type strain. Hybridization of the same blot with the RPM1 3′ junction probe (probe 4) verified that the pre-RPM1 intermediate does not contain a 3′ extension sequence in pet127Δ. As expected, 5′ processing of tRNAPro by RNase P was not affected in the pet127Δ mutant. The identities of the bands were verified by hybridization of the blot with the RPM1 probe (Fig. 6A, probe 3).

FIG. 6.

Northern analysis of pre-RPM1-pro and pre-RPM1 processing in the pet127Δ strain. (A) The initial RPM1-containing transcript is shown with the position of the probes (2 to 4) used for Northern blot analysis. A Northern blot of 30 μg of total RNA from pet127Δ was hybridized with a probe complementary to sequence spanning the mature 5′ end of RPM1 (5′ junction probe, probe 2). The blot was stripped and probed for RPM1 (probe 3). The blot was again stripped and hybridized with a probe complementary to the sequence spanning the mature 3′ end of RPM1 (3′ junction probe, probe 4). The 5′ junction probe and the 3′ junction probe were designed such that hybridization would occur only when both upstream and downstream sequences spanning the mature ends were present in the transcript. wt, wild type. (B) A Northern blot of total RNA from the htd2Δ, pet127Δ, and htd2Δpet127Δ strains was hybridized with the RPM1 probe, stripped, and hybridized with the SCR1 loading control probe.

Given that Pet127 is required for 5′ end processing of RPM1 RNA, we determined whether a defect in the FAS II pathway is epistatic to pet127Δ. A Northern blot containing RNA from the htd2Δ pet127Δ double mutant, as well as the htd2Δ and pet127Δ single mutants, was hybridized with the RPM1 probe (Fig. 6B). The htd2Δ pet127Δ double mutant accumulated the same longer pre-RPM1-pro precursor with a 5′ end extension that was observed for the htd2Δ single mutant. These results indicate that htd2Δ is epistatic to pet127Δ and that trimming of the 5′ end of the pre-RPM1-pro in a Pet127-driven reaction requires prior FAS II pathway-dependent removal of tRNAPro from the 3′ end of the precursor transcript.

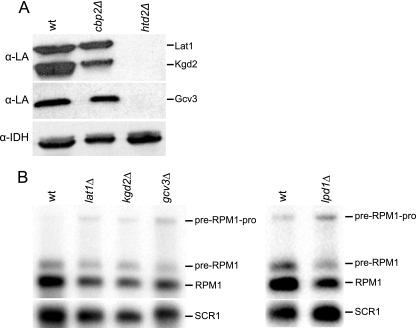

The FAS II pathway is required for lipoylation of three mitochondrial proteins.

Brody et al. (6) and Wada et al. (56) proposed that the mitochondrial FAS II pathway exists to provide the octanoic acid precursor for lipoic acid biosynthesis. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the lipoylation state of three lipoic acid-modified mitochondrial proteins in wild-type and FAS II mutant strains. Western blots of mitochondrial proteins were probed with an antibody specific for lipoic acid (24) (Fig. 7A). In the wild type, the anti-lipoic acid antibody detected all of the known lipoylated proteins, Lat1, the E2 subunit of PDH, Kgd2, the E2 subunit of α-KDH, and Gcv3, the H protein of GC. In the htd2Δ strain, however, none of these lipoylated proteins were detected, even following overexposure of the film. These data support the long-standing hypothesis (6, 56) that the FAS II pathway is the sole source of the octanoic acid precursor required for lipoylation of the E2 subunits and the H protein assayed here. These data also suggest that elimination of lipoylation may be sufficient to cause the respiration-deficient phenotype of the FAS II mutant strains.

FIG. 7.

The FAS II pathway is the sole source of octanoic acid for protein lipoylation. (A) Western blot analysis of lipoylated proteins in a FAS II mutant strain. Mitochondrial extracts from the wild-type strain (wt), the cbp2Δ strain, a respiration-deficient control strain, and the htd2Δ strain were analyzed by Western blotting using an antibody directed against lipoic acid (α-LA). Lat1 and Kgd2 are the lipoylated E2 proteins of PDH and α-KDH, respectively, and Gcv3 is the lipoylated H protein of GC. Antiserum IDH (α-IDH) was used as a loading control. (B) Northern blot analysis of pre-RPM1-pro processing in the lat1Δ, kgd2Δ, and gcv3Δ strains, as well as in the lpd1Δ strain, was done using the RPM1 probe. Lpd1 is a common subunit shared by the three lipoic acid-dependent enzyme complexes. SCR1 was used as the loading control.

In light of these results, we asked whether the enzymatic function of the lipoic acid-dependent mitochondrial multienzyme complexes is important for pre-RPM1-pro RNA processing. To address this question, we examined the RNA processing phenotype of strains harboring deletions of LAT1, KGD2, and GCV3. In these strains, processing of pre-RPM1-pro is partially affected (Fig. 7B), but the phenotype is not as severe as that of the FAS II mutant strains. We also analyzed RNA processing in lpd1Δ (the LPD1 gene encodes dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase, a subunit common to all three complexes [40]). These data indicate that the enzymatic function of the lipoic acid-dependent complexes is not required for processing of the pre-RPM1-pro transcript by RNase P but rather that synthesis of a fatty acid, such as octanoic or lipoic acid, is necessary for efficient processing.

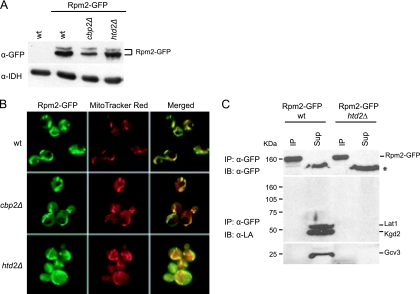

The tRNA processing defect is not due to mislocalization of Rpm2 in the htd2Δ strain.

The tRNA processing defect in FAS II mutant strains may result from a reduction in RNase P activity due to either a partial blockage of import from the cytoplasm of Rpm2, the RNase P protein subunit, or to Rpm2 instability. Indeed, certain rpm2 mutant alleles result in accumulation of the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA (48, 49), a phenotype similar to that of the FAS II mutant strains. It is known that a disruption of the FAS II pathway affects mitochondrial morphology (25, 53), which may in turn affect import of Rpm2 from the cytoplasm. To investigate these possibilities, fluorescence microscopy and Western blotting were used to analyze localization and levels of a chromosomally expressed Rpm2-GFP fusion protein in the wild-type as well as in the htd2Δ and cbp2Δ mutant backgrounds. The Rpm2-GFP wild-type strain respires and displays wild-type RPM1 and tRNA processing (data not shown), suggesting that the Rpm2-GFP protein is imported into the mitochondrial compartment and is functional. Expression of Rpm2-GFP was analyzed by Western blotting of mitochondrial extracts, using an anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 8A). The protein detected in the wild type and the htd2Δ strain was of similar abundance, which indicates that a defect in fatty acid synthesis does not markedly affect steady-state levels of the Rpm2-GFP protein. In cells containing either an intact or a disrupted FAS II pathway, green fluorescent signal from Rpm2-GFP coincided with the red fluorescent signal from MitoTracker red dye that was added to the cells before harvesting (Fig. 8B). However, cells containing the htd2Δ mutation appeared to have more cytoplasmic green fluorescence than wild-type cells, indicating perhaps inefficient import of Rpm2-GFP or leaky mitochondrial membranes. These data show that Rpm2-GFP is localized primarily in mitochondria in the fatty acid biosynthetic-deficient strain.

FIG. 8.

Analysis of Rpm2-GFP. Strains used were Rpm2-GFP wild-type, Rpm2-GFP cbp2Δ, a respiration-deficient control strain, and Rpm2-GFP htd2Δ. (A) Rpm2-GFP protein levels were analyzed by a Western blot of mitochondrial extracts, using an antibody against GFP (α-GFP) to detect Rpm2-GFP. IDH (antiserum α-IDH) was used as a loading control. (B) Rpm2-GFP is localized to mitochondria. Cells harvested at mid-log phase were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. MitoTracker Red was added to the cultures 45 min before harvesting. (C) Rpm2-GFP is not lipoylated. Proteins from mitochondrial matrix fractions from Rpm2-GFP wild-type (wt) and Rpm2-GFP htd2Δ were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-GFP antibody and protein A-coupled beads. Nonimmunoprecipitated protein (Sup) was trichloroacetic acid precipitated, and 30% of both the IP and Sup fractions were loaded onto a 7 to 17% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were immunoblotted (IB) with anti-lipoic acid antibody (α-LA, lower panels). The blot was stripped and incubated with anti-GFP antibody (α-GFP, upper panel). The asterisk marks a nonspecific background band.

Rpm2-GFP is not lipoylated.

One simple hypothesis to explain the requirement of the FAS II-lipoic acid-dependent pathways for tRNA processing is that Rpm2 is lipoylated and that lipoylation is required for RNase P activity. In response to this hypothesis, Rpm2-GFP was immunoprecipitated from the soluble matrix fraction of mitochondrial extracts from the wild-type, Rpm2-GFP wild-type, and Rpm2-GFP htd2Δ strains by using a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody. Lipoylation of the immunoprecipitated protein was then analyzed by Western blotting with the anti-lipoic acid antibody (Fig. 8C, lower panels). No lipoylated proteins of the same mass as Rpm2-GFP were detected in the immunoprecipitated lanes. Also, no lipoylated proteins were observed in the Rpm2-GFP htd2Δ lanes, as expected. The blot was stripped and subsequently probed with a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody, which showed that most of the Rpm2-GFP protein had been immunoprecipitated from the GFP-tagged strains (Fig. 8C, upper panel). These data indicate that Rpm2-GFP is not lipoylated.

DISCUSSION

Here we show that disruption of the mitochondrial FAS II pathway in yeast results in inefficient processing at the 5′ ends of mitochondrial tRNAs by RNase P. Specifically, in FAS II mutant strains, removal of tRNAPro from the 3′ end of the pre-RPM1-pro transcript is inhibited, resulting in low levels of mature RPM1, the RNA subunit of mitochondrial RNase P. We conclude that a product of the FAS II pathway is required either for (i) RNase P cleavage of all pre-tRNAs or (ii) maturation of the RNase P RNA itself, thus affecting assembly and/or activity of RNase P and subsequent processing of all other tRNA-containing multigenic transcripts. Our data reveal a novel connection between fatty acid metabolism and gene expression in mitochondria.

RNase P complexes exist in all kingdoms of life, although their components vary in homology and number (57, 61). Mitochondrial RNase P activity has been found in vertebrates, fungi, protists, and plants (57), but mitochondrially encoded RNase P RNA has been identified only in a number of ascomycete fungi, the protist Reclinomonas americana, and the green alga Nephroselmis olivacea (43). In these organisms, RNase P RNA is most often transcribed as part of a multigenic transcription unit that includes at least one tRNA gene (43, 44). In some instances, RNase P RNA 5′ and 3′ ends are formed by tRNA processing enzymes, unlike S. cerevisiae, in which multiple processing events must occur to produce mature RPM1 RNA. Despite differences in the details of the pathway for processing the RNA component, RNase P plays a critical role in the expression of mitochondrial genes and is in many cases involved in the maturation pathway of its own RNA subunit.

The purpose of the mitochondrial FAS II pathway in eukaryotes has been under debate. Brody et al. (6) and Wada et al. (56) have proposed that the production of octanoic acid, the precursor to the cofactor lipoic acid, is the sole purpose of this separate organelle pathway. The FAS II pathway may play a role in the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology as deletion or overexpression of genes encoding pathway enzymes causes morphological defects (25, 53). It has also been suggested that the FAS II pathway may provide fatty acids for phospholipid repair (42) or for insertion of membrane proteins (19), but no evidence has been generated to support these hypotheses. While it has been shown for other organisms that the mitochondrial FAS II pathway is capable of synthesis of fatty acids longer than C8 (60), the physiological relevance of these fatty acids still remains to be demonstrated. Our results suggest that the mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis pathway is the sole source of octanoic acid used as the precursor for synthesis of lipoic acid.

There are two basic models one can build to explain the intersection of RNase P activity or assembly and fatty acid biosynthesis. The first model posits that the biosynthetic pathway provides a product that directly modifies the RNase P enzyme, either on the Rpm2 protein or the RPM1 RNA component. The second model suggests that a pathway product indirectly affects RNase P assembly or activity.

In pursuit of the direct modification hypothesis, we have eliminated the possibility that Rpm2 is modified in a detectable amide linkage by lipoic acid, a downstream product of the FAS II pathway. However, the protein may be modified by octanoic acid or a longer fatty acid product of the pathway. Probing a Northern blot of mitochondrial RNA with the anti-lipoic acid antiserum did not detect a modification (data not shown). The antiserum may be ineffective in detecting lipoic acid attached to RNA, or the RNA may be modified by another fatty acid. It is possible that fatty acid or lipoic acid could directly affect the conformation of the protein or RNA directly but in a noncovalent association. We have no evidence yet for a direct covalent or noncovalent modification of the enzyme.

Since mitochondrial morphology is affected in FAS II mutant strains (25, 53), we tested one example of an indirect effect on RNase P. We showed that Rpm2-GFP is imported into mitochondria (Fig. 8B), though there is some cytoplasmic staining, suggesting that the process may not be as efficient as in the wild type. Many other indirect scenarios have not been investigated yet, including covalent or noncovalent modification of other proteins that may interact with RNase P.

All FAS II mutant strains, except the hfa1Δ strain, are respiration deficient at all temperatures. All of the strains maintain stable mitochondrial genomes when grown at 30°C, which suggests that, despite the inefficiency of tRNA processing, enough mature tRNAs are produced to support mitochondrial translation, which is required for the maintenance of mtDNA (9, 32). When the mutant strains are grown at temperatures higher than 30°C, however, tRNA processing is further blocked (Fig. 4B), and after ∼50 generations of growth at 37°C, the strains lose their mtDNA (data not shown).

The hfa1Δ strain respires at 30°C but not at 37°C in our strain background (S288C). HFA1 encodes mitochondrial acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) carboxylase, which produces malonyl-CoA from acetyl-CoA (6). The additional source of malonyl-CoA that supports respiration in the mutant strain at 30°C is not known. In a global tandem affinity purification (TAP) tag study of protein-protein interactions (26), Hfa1 purified with Acc1, the cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA carboxylase. It is possible that Acc1 is imported inefficiently into mitochondria and produces malonyl-CoA at a reduced rate compared to Hfa1. An alternative hypothesis is that malonyl-CoA is imported into the mitochondrial compartment from the cytosol. It has been shown that exogenous [14C]malonyl-CoA supports fatty acid synthesis in mitochondria isolated from Trypanosoma brucei (47). It would be interesting to understand why increased temperature exacerbates the mitochondrial tRNA processing defect in the FAS II mutant strains.

Why does mitochondrial fatty acid biosynthesis and tRNA processing intersect? Our hypothesis is that this intersection has evolved to allow the cell to regulate mitochondrial gene expression in response to levels of cellular catabolites. The organization of the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA is particularly interesting in that it houses a tRNA downstream of RPM1. Since RNase P activity is required for the maturation of the RNase P RNA subunit, a positive feedback loop exists for RNase P maturation and activity (Fig. 9). A product of the FAS II pathway is involved in this cycle because it is required for directly stimulating RNase P activity and/or for efficiently processing the precursor RNA containing RNase P RNA. A second positive feedback loop could be operative under some conditions for PDH activity and the FAS II pathway. PDH requires lipoic acid for the production of acetyl-CoA (36), which is fed into the FAS II pathway, which produces the octanoic acid precursor for lipoic acid synthesis (Fig. 9). However, cells containing inactive PDH lipoylate target proteins and have wild-type mitochondrial tRNA processing when grown in rich medium containing glucose, indicating that acetyl-CoA from another source, such as the PDH bypass pathway (5), amino acid breakdown (20), or β-oxidation of fatty acids (4), can be fed into the FAS II pathway. The two feedback cycles described above may provide a switch-like character for turning mitochondrial function on or off in response to the availability of acetyl-CoA entering the organelle.

FIG. 9.

Positive feedback loops governing fatty acid-lipoic acid biosynthesis and RNase P activity. The intersection of the FAS II pathway and RNase P activity in yeast mitochondria is depicted as a cartoon. In the FAS II pathway, acetyl-CoA (or acetyl-acyl carrier protein [ACP]) and malonyl-ACP are condensed on ACP, and the carbon chain is elongated in several iterative steps to produce octanoic acid (21) (Fig. 3). Other enzymes convert octanoic acid to lipoic acid (50) and attach the cofactor to target proteins (28). Lipoic acid is required for pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, creating one positive feedback loop. Fatty acid and/or lipoic acid is required for efficient RNase P activity. The second positive feedback loop is created because RNase P activity is required for the maturation of its own RNA subunit, RPM1, via an endonucleolytic cleavage of tRNAPro from the pre-RPM1-pro precursor RNA. The dashed arrows represent the requirement of lipoic acid for PDH, α-KDH, and GC enzymatic activity. The dotted arrow (at right) represents the requirement of a product of the FAS II pathway for RNase P activity or assembly.

Recently, an intersection between the FAS II pathway and tRNA processing has emerged in mammals. The human 3-hydroxyacyl-thioester dehydratase 2 (HsHTD2) of the mitochondrial FAS II pathway was found to be encoded on a bicistronic cDNA downstream of RPP14, a protein subunit of RNase P (3). This genetic organization has been conserved over 400 million years of vertebrate evolution. It is currently under debate whether mammalian RNase P processes both nuclearly encoded and mitochondrial tRNA precursors (37) or whether mammalian cells contain two distinct RNase P activities (39). Clearly, though the nature of the connection between the mitochondrial FAS II pathway and tRNA processing is different in yeast and vertebrates, both systems have the potential to be regulated by the availability of acetyl-CoA. The biological importance of the intersection of the FAS II pathway and RNase P function in tRNA processing is just beginning to be understood.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to Stuart Brody, who discovered the acyl carrier protein in yeast (6) and launched the study of mitochondrial fatty acid biosynthesis.

We thank Telsa Mittelemeier and John Little for critical reading of the manuscript, Zsuzsanna Fekete for helpful discussions and suggestions, and Mike Rice and Tim Ellis for help in the laboratory. We also thank Lee McAlister-Henn for the generous gift of anti-IDH antisera.

M.S.S. was supported by a fellowship from the National Science Foundation Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship Program in Evolutionary, Functional and Computational Genomics at the University of Arizona and by the National Institutes of Health Graduate Training in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology grant T3208659. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM34893 to C.L.D.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, S., A. T. Bankier, B. G. Barrell, M. H. de Bruijn, A. R. Coulson, J. Drouin, I. C. Eperon, D. P. Nierlich, B. A. Roe, F. Sanger, P. H. Schreier, A. J. Smith, R. Staden, and I. G. Young. 1981. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 290457-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attardi, G., and G. Schatz. 1988. Biogenesis of mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 4289-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Autio, K. J., A. J. Kastaniotis, H. Pospiech, I. J. Miinalainen, M. S. Schonauer, C. L. Dieckmann, and J. K. Hiltunen. 2008. An ancient genetic link between vertebrate mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis and RNA processing. FASEB J. 22569-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black, P. N., and C. C. DiRusso. 2007. Yeast acyl-CoA synthetases at the crossroads of fatty acid metabolism and regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771286-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boubekeur, S., O. Bunoust, N. Camougrand, M. Castroviejo, M. Rigoulet, and B. Guerin. 1999. A mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase bypass in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 27421044-21048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brody, S., C. Oh, U. Hoja, and E. Schweizer. 1997. Mitochondrial acyl carrier protein is involved in lipoic acid synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 408217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caponigro, G., D. Muhlrad, and R. Parker. 1993. A small segment of the MATα1 transcript promotes mRNA decay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a stimulatory role for rare codons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 135141-5148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, J.-Y., and N. C. Martin. 1988. Biosynthesis of tRNA in yeast mitochondria. An endonuclease is responsible for the 3′-processing of tRNA precursors. J. Biol. Chem. 26313677-13682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Contamine, V., and M. Picard. 2000. Maintenance and integrity of the mitochondrial genome: a plethora of nuclear genes in the budding yeast. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64281-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieckmann, C. L., and R. R. Staples. 1994. Regulation of mitochondrial gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, p. 145-181. In K. W. Jeon and J. W. Jarvik (ed.), International review of cytology. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, CA. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Dziembowski, A., J. Piwowarski, R. Hoser, M. Minczuk, A. Dmochowska, M. Siep, H. van der Spek, L. Grivell, and P. P. Stepien. 2003. The yeast mitochondrial degradosome. Its composition, interplay between RNA helicase and RNase activities and the role in mitochondrial RNA metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2781603-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis, T. P., M. S. Schonauer, and C. L. Dieckmann. 2005. CBT1 interacts genetically with CBP1 and the mitochondrially encoded cytochrome b gene and is required to stabilize the mature cytochrome b mRNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 171949-957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faye, G., C. Kujawa, and H. Fukuhara. 1974. Physical and genetic organization of petite and grande yeast mitochondrial DNA. IV. In vivo transcription products of mitochondrial DNA and localization of 23 S ribosomal RNA in petite mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 88185-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fekete, Z., T. P. Ellis, M. S. Schonauer, and C. L. Dieckmann. 2008. Pet127 governs a 5′-> 3′-exonuclease important in maturation of apocytochrome b mRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2833767-3772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foury, F., T. Roganti, N. Lecrenier, and B. Purnelle. 1998. The complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 440325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank, D. N., and N. R. Pace. 1998. Ribonuclease P: unity and diversity in a tRNA processing ribozyme. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67153-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gietz, R. D., and R. A. Woods. 2002. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 35087-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harington, A., C. J. Herbert, B. Tung, G. S. Getz, and P. P. Slonimski. 1993. Identification of a new nuclear gene (CEM1) encoding a protein homologous to a beta-keto-acyl synthase which is essential for mitochondrial respiration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 9545-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harington, A., E. Schwarz, P. P. Slonimski, and C. J. Herbert. 1994. Subcellular relocalization of a long-chain fatty acid CoA ligase by a suppressor mutation alleviates a respiration deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 135531-5538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hazelwood, L. A., J. M. Daran, A. J. van Maris, J. T. Pronk, and J. R. Dickinson. 2008. The Ehrlich pathway for fusel alcohol production: a century of research on Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 742259-2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiltunen, J. K., F. Okubo, V. A. Kursu, K. J. Autio, and A. J. Kastaniotis. 2005. Mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis and maintenance of respiratory competent mitochondria in yeast. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 331162-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoja, U., S. Marthol, J. Hofmann, S. Stegner, R. Schulz, S. Meier, E. Greiner, and E. Schweizer. 2004. HFA1 encoding an organelle-specific acetyl-CoA carboxylase controls mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 27921779-21786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huh, W. K., J. V. Falvo, L. C. Gerke, A. S. Carroll, R. W. Howson, J. S. Weissman, and E. K. O'Shea. 2003. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425686-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humphries, K. M., and L. I. Szweda. 1998. Selective inactivation of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase: reaction of lipoic acid with 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Biochemisty 3715835-15841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastaniotis, A. J., K. J. Autio, R. T. Sormunen, and J. K. Hiltunen. 2004. Htd2p/Yhr067p is a yeast 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase essential for mitochondrial function and morphology. Mol. Microbiol. 531407-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krogan, N. J., G. Cagney, H. Yu, G. Zhong, X. Guo, A. Ignatchenko, J. Li, S. Pu, N. Datta, A. P. Tikuisis, T. Punna, J. M. Peregrin-Alvarez, M. Shales, X. Zhang, M. Davey, M. D. Robinson, A. Paccanaro, J. E. Bray, A. Sheung, B. Beattie, D. P. Richards, V. Canadien, A. Lalev, F. Mena, P. Wong, A. Starostine, M. M. Canete, J. Vlasblom, S. Wu, C. Orsi, S. R. Collins, S. Chandran, R. Haw, J. J. Rilstone, K. Gandi, N. J. Thompson, G. Musso, P. St Onge, S. Ghanny, M. H. Lam, G. Butland, A. M. Altaf-Ul, S. Kanaya, A. Shilatifard, E. O'Shea, J. S. Weissman, C. J. Ingles, T. R. Hughes, J. Parkinson, M. Gerstein, S. J. Wodak, A. Emili, and J. F. Greenblatt. 2006. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 440637-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marvin, M. E., P. H. Williams, and A. M. Cashmore. 2001. The isolation and characterisation of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene (LIP2) involved in the attachment of lipoic acid groups to mitochondrial enzymes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 199131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGraw, P., and A. Tzagoloff. 1983. Assembly of the mitochondrial membrane system. Characterization of a yeast nuclear gene involved in the processing of the cytochrome b pre-mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2589459-9468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morales, M. J., Y. L. Dang, Y. C. Lou, P. Sulo, and N. C. Martin. 1992. A 105-kDa protein is required for yeast mitochondrial RNase P activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 899875-9879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morl, M., and A. Marchfelder. 2001. The final cut. The importance of tRNA 3′-processing. EMBO Rep. 217-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers, A. M., L. K. Pape, and A. Tzagoloff. 1985. Mitochondrial protein synthesis is required for maintenance of intact mitochondrial genomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 42087-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagarajan, L., and R. K. Storms. 1997. Molecular characterization of GCV3, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene coding for the glycine cleavage system hydrogen carrier protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2724444-4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niu, X. D., K. S. Browning, R. H. Behal, and L. J. Reed. 1988. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene for dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 857546-7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perham, R. N. 2000. Swinging arms and swinging domains in multifunctional enzymes: catalytic machines for multistep reactions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69961-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pronk, J. T., S. H. Yde, and J. P. van Dijken. 1996. Pyruvate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 121607-1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puranam, R. S., and G. Attardi. 2001. The RNase P associated with HeLa cell mitochondria contains an essential RNA component identical in sequence to that of the nuclear RNase P. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21548-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Repetto, B., and A. Tzagoloff. 1990. Structure and regulation of KGD2, the structural gene for yeast dihydrolipoyl transsuccinylase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 104221-4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossmanith, W., and R. M. Karwan. 1998. Characterization of human mitochondrial RNase P: novel aspects in tRNA processing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 247234-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy, D. J., and I. W. Dawes. 1987. Cloning and characterization of the gene encoding lipoamide dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133925-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneider, R., B. Brors, F. Burger, S. Camrath, and H. Weiss. 1997. Two genes of the putative mitochondrial fatty acid synthase in the genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 32384-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider, R., B. Brors, M. Massow, and H. Weiss. 1997. Mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis: a relic of endosymbiontic origin and a specialized means for respiration. FEBS Lett. 407249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seif, E. R., L. Forget, N. C. Martin, and B. F. Lang. 2003. Mitochondrial RNase P RNAs in ascomycete fungi: lineage-specific variations in RNA secondary structure. RNA 91073-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shu, H. H., and N. C. Martin. 1991. RNase P RNA in Candida glabrata mitochondria is transcribed with substrate tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 196221-6226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith, S. 1994. The animal fatty acid synthase: one gene, one polypeptide, seven enzymes. FASEB J. 81248-1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinmetz, L. M., C. Scharfe, A. M. Deutschbauer, D. Mokranjac, Z. S. Herman, T. Jones, A. M. Chu, G. Giaever, H. Prokisch, P. J. Oefner, and R. W. Davis. 2002. Systematic screen for human disease genes in yeast. Nat. Genet. 31400-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stephens, J. L., S. H. Lee, K. S. Paul, and P. T. Englund. 2007. Mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 2824427-4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stribinskis, V., G. J. Gao, P. Sulo, Y. L. Dang, and N. C. Martin. 1996. Yeast mitochondrial RNase P RNA synthesis is altered in an RNase P protein subunit mutant: insights into the biogenesis of a mitochondrial RNA-processing enzyme. Mol. Cell. Biol. 163429-3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stribinskis, V., G. J. Gao, P. Sulo, S. R. Ellis, and N. C. Martin. 2001. Rpm2p: separate domains promote tRNA and Rpm1r maturation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 293631-3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sulo, P., and N. C. Martin. 1993. Isolation and characterization of LIP5: a lipoate biosynthetic locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 26817634-17639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tehlivets, O., K. Scheuringer, and S. D. Kohlwein. 2007. Fatty acid synthesis and elongation in yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771255-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teixeira, M. T., B. Dujon, and E. Fabre. 2002. Genome-wide nuclear morphology screen identifies novel genes involved in nuclear architecture and gene-silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 321551-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torkko, J. M., K. T. Koivuranta, I. J. Miinalainen, A. I. Yagi, W. Schmitz, A. J. Kastaniotis, T. T. Airenne, A. Gurvitz, and K. J. Hiltunen. 2001. Candida tropicalis Etr1p and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ybr026p (Mrf1′p), 2-enoyl thioester reductases essential for mitochondrial respiratory competence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 216243-6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tzagoloff, A., and C. L. Dieckmann. 1990. PET genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 54211-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Underbrink-Lyon, K., D. L. Miller, N. A. Ross, H. Fukuhara, and N. C. Martin. 1983. Characterization of a yeast mitochondrial locus necessary for tRNA biosynthesis. Deletion mapping and restriction mapping studies. Mol. Gen. Genet. 191512-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wada, H., D. Shintani, and J. Ohlrogge. 1997. Why do mitochondria synthesize fatty acids? Evidence for involvement in lipoic acid production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 941591-1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker, S. C., and D. R. Engelke. 2006. Ribonuclease P: the evolution of an ancient RNA enzyme. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 4177-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wiesenberger, G., and T. D. Fox. 1997. Pet127p, a membrane-associated protein involved in stability and processing of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial RNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 172816-2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiesenberger, G., F. Speer, G. Haller, N. Bonnefoy, A. Schleiffer, and B. Schafer. 2007. RNA degradation in fission yeast mitochondria is stimulated by a member of a new family of proteins that are conserved in lower eukaryotes. J. Mol. Biol. 367681-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Witkowski, A., A. K. Joshi, and S. Smith. 2007. Coupling of the de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and lipoylation pathways in mammalian mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 28214178-14185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiao, S., F. Scott, C. A. Fierke, and D. R. Engelke. 2002. Eukaryotic ribonuclease P: a plurality of ribonucleoprotein enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71165-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yarunin, A., V. G. Panse, E. Petfalski, C. Dez, D. Tollervey, and E. C. Hurt. 2005. Functional link between ribosome formation and biogenesis of iron-sulfur proteins. EMBO J. 24580-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zewail, A., M. W. Xie, Y. Xing, L. Lin, P. F. Zhang, W. Zou, J. P. Saxe, and J. Huang. 2003. Novel functions of the phosphatidylinositol metabolic pathway discovered by a chemical genomics screen with wortmannin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1003345-3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]