Abstract

The synthesis and reactivity of dibenzyl cationic tantalum imido complexes is described. The trialkyl tantalum imido compounds Bn3Ta=NCMe3 (1) and Np3Ta=NCMe3 (2) were synthesized as starting materials for the study of dialkyl cationic tantalum imido complexes. Compound 1 undergoes insertion reactions with diisopropylcarbodiimide and 2,6-dimethylphenylisocyanide to give (bisamidinate)imido complex 5 and (bisimino-acyl)imido complex 6, respectively. Treatment of compound 1 with B(C6F5)3 gives the zwitterionic tantalum complex [Bn2Ta=NCMe3][BnB(C6F5)3] (7) which is stabilized by η6-coordination of the benzyl triaryl borate anion. Coordination of the aryl anion can be displaced by three equivalents of pyridine to give the Lewis base complex 8. Treatment of compound 1 with [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] gives the cationic tantalum imido complex [Bn2Ta=NCMe3][B(C6F5)4] (3). This salt forms insoluble aggregates unless trapped by THF coordination or an insertion reaction with an alkyne or an alkene. Cation 3 undergoes migratory insertion reactions with diphenylacetylene, phenylacetylene, norbornene, and cis-cyclooctene to give the corresponding alkenyl or modified alkyl imido complexes. The characterization of these products and the significance of these insertion reactions with respect to Ziegler-Natta polymerizations and hydroamination reactions are described.

Introduction

Zirconocene imido complexes have been shown to undergo a variety of stoichiometric transformations such as [2+2] cycloadditions to form azametallacyclic compounds,1–3 activation of arene and alkane C-H bonds,2,4,5 epoxide ring-opening reactions,6 stereochemical rearrangements of 1,3-disubstituted allenes,7–9 and SN2′ additions to allyl alcohols.10 In addition to these stoichiometric transformations, zirconocene imido complexes have also been investigated as catalysts for hydroamination11,12 and imine metathesis.13–15 Metal-imido ligands of Group 5 and 6 complexes are generally less reactive than Group 4 analogues and have been used as ancillary groups for polymerization and metathesis catalysts.16,17 In an attempt to extend the reactivity of Group 4 imido compounds to Group 5, we have synthesized isoelectronic cationic tantalum imido complexes and investigated their reactivity with unsaturated organic substrates.

Many neutral tantalum imido compounds have been synthesized18–21 but the reactivity patterns of these complexes are ambiguous. Tantalum imido functionalities have been used as both ancillary ligands and as reactive sites. As ancillary ligands they have been compared electronically to cyclopentadienide.22 Stoichiometric transformations such as protonations of tantalum-amides,23 additions of dihydrogen to tantalum-alkyl groups,24,25 and insertions of isocyanides into tantalum-alkyl bonds25–28 have been observed in the presence of tantalum imido groups. In contrast to these examples of tantalum imido functionalities as spectator ligands, migratory insertions of isocyanides and CO2, imine and carbodiimide metatheses, imido to oxo ligand exchange, and the activation of benzene C-H bonds have been observed with Ta=NR bonds.29 The tantalum imido complex CpCl2Ta=NCMe3 has also been studied as an imine metathesis catalyst and a (bisguanidinate) tantalum imido complex has been investigated as a carbodiimide metathesis catalyst.30,31

Little is known about the reactivity trends of cationic tantalum imido complexes since few of these species have been synthesized and studied. Several examples have been generated in situ and employed as polymerization catalysts but the stoichiometric reactivity of cationic tantalum imido complexes and the mechanistic aspects of their polymerization reactions are not well understood.32–35 The most extensive investigation thus far has been the Bercaw group’s study of the cationic tantalum imido complex [(THF)Cp*2Ta=NCMe3][B(C6F5)4].36 Dihydrogen, phenylacetylene, and the methyl group of a Cp* ligand have been observed to add across the imido bond of this salt. Hermann and coworkers have also synthesized an amine-coordinated cationic tantalum imido complex by protonation of an amide group at a tantalum center with [PhNHMe2][BPh4],23 and Green has observed ethylene coordination to a cationic niobocene complex by NMR spectroscopy.37 In addition, Meyer and coworkers have abstracted a chloride ligand from an amidinate tantalum imido complex to form an SbF6− salt.35 These encouraging reports prompted our search for a more complete description of the reactivity of these complexes and a comparison to Group 4 imido compounds.

We have previously reported the hydroamination reactivity of the neutral and cationic tantalum imido complexes Bn3Ta=NCMe3 (1), Np3Ta=NCMe3 (2), and [Bn2Ta=NCMe3][B(C6F5)4] (3).38 All of these complexes are competent catalysts for the hydroamination of several different alkynes with a variety of anilines. Cationic complex 3 was shown to be the most efficient catalyst for these transformations. Here we report several stoichiometric transformations of compound 1 as well as the reactivity of two different types of cationic dibenzyltantalum imido complexes. Although the hydroamination catalysis of these complexes is similar to that of Group 4 metallocene imido compounds, their stoichiometric reactivity is distinct. Below we will describe the synthesis of neutral and cationic tantalum imido complexes and discuss the reactivity of these compounds with isocyanides, carbodiimides, alkynes, and alkenes.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Trialkyltantalum Imido Complexes

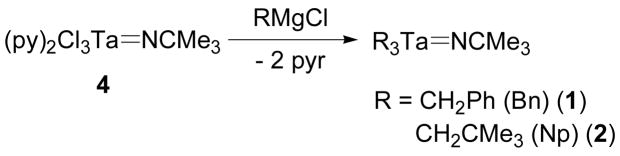

Charge-neutral trialkyl tantalum imido compounds were synthesized as simple starting materials to be used in the syntheses of cationic tantalum imido complexes. Compounds 1 and 2 were synthesized from the trichloride 4 via a salt metathesis with the appropriate Grignard reagent (Scheme 1). The neopentyl and benzyl groups of 1 and 2, respectively, are equivalent by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. This observation is consistent with 1 and 2 adopting C3 symmetry in solution and having time-averaged linear geometry at the imido bond. Furthermore, the chemical shift differences between the 13C NMR resonances for the quaternary t-butyl carbons and the primary t-butyl carbons of 1 and 2 are 34.8 ppm and 34.0 ppm, respectively.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of trialkyl tantalum imido complexes 1 and 2.

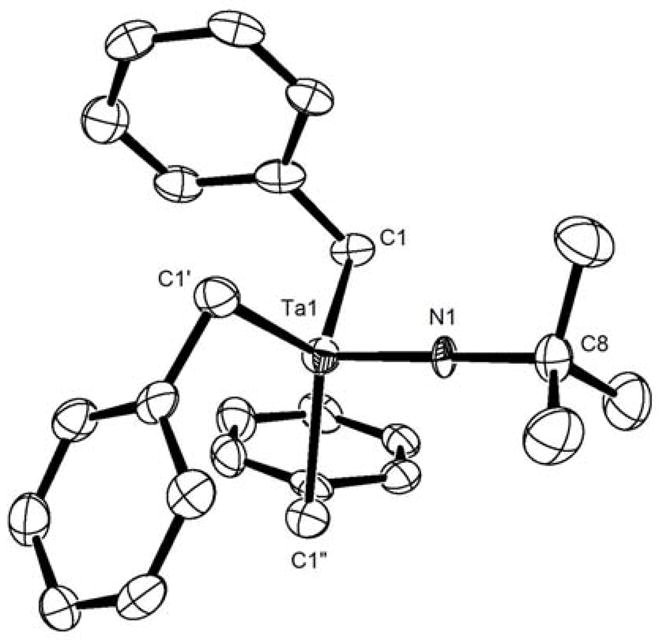

Single crystals of 1 were grown from a diethyl ether solution at −40 °C. An X-ray diffraction analysis of one of these crystals provided the structure depicted in Figure 1. Compound 1 crystallizes in the P31c space group and has C3 symmetry in the solid state. All three benzyl groups are crystallographically identical because of the symmetry of the space group. The Ta-C bond length of 1 is 2.216 Å and the Ta(1)-N(1)-C(8) bond angle is 180.0°. This Ta-C bond length is similar to other reported values for tantalum-benzyl bonds in the literature.39–41 The Ta(1)-N(1) bond length is 1.737 Å, which is the shortest reported value for a tantalum t-butyl imido bond.41–44

Figure 1.

An ORTEP diagram of the X-ray crystal structure of 1. Ta-C1 = Ta-C1′ = Ta-C1″ = 2.216 Å. Ta-N1 = 1.737 Å. Ta-N1-Cx = 180.0°.

Characterization of compounds 1 and 2 included the determination of the degree of π-donation from the imido nitrogen to the metal-center. This feature was investigated in order to classify these imido functionalities as either X2L or X2 ligands.45 The C3 symmetry of the crystal structure of 1 strongly suggested that the imido group of this complex was an X2L ligand; however, the 180° bond angle for Ta(1)-N(1)-C(8) could have been imposed by the space group of the crystal structure. Therefore, spectroscopic characteristics of 1 and 2 were investigated for further evidence of π-donation. The C3v symmetry that was observed for these compounds by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy supported the X-ray structure description of 1. In addition, the difference in 13C NMR chemical shifts between the quaternary carbons and the methyl carbons of the t-butyl imido groups of 1 and 2 are 34.8 and 34.0, respectively. These differences have previously been used to characterize imido-metal bonds and larger values have been shown to correspond to greater degrees of π-donation.37,46 The values for 1 and 2 place these complexes at the high end of the reported scale and corroborate the assignment of the imido groups as X2L ligands.

Migratory Insertion Reactions of Diisopropylcarbodiimide and 2,6-Dimethylphenyisocyanide with Bn3Ta=NCMe3 (1)

The reactivity of compound 1 was investigated before the corresponding cationic complexes were synthesized. Compound 1 was initially treated with diisopropylcarbodiimide. This reagent reacts rapidly with zirconocene imido complexes to form diazazirconacyclobutane complexes.14 Carbodiimides have also been observed to undergo stoichiometric metathesis reactions with Cp*Cl2Ta=NCMe3 and catalytic carbodiimide metatheses with (bisguanidinate) tantalum imido compounds.29,31 This precedent suggested that diisopropylcarbodiimide was likely to undergo a [2+2] cycloaddition with 1 at the imido functionality; however, the alkyl ligands of 1 presented another potential reactive site.

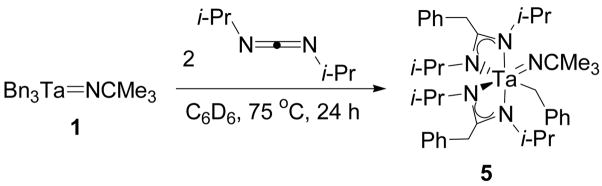

Treatment of a solution of 1 in benzene-d6 with one equivalent of diisopropylcarbodiimide gave no reaction. Heating this mixture in a sealed NMR tube at 75 °C for 24 h resulted in conversion of half of the tantalum starting material to a new product and complete consumption of the carbodiimide. In order to facilitate the complete consumption of 1, the experiment was repeated with a 2:1 ratio of the carbodiimide to the tantalum imido complex. This reaction mixture gave 5 after thermolysis at 75 °C (Scheme 2). Compound 5 is formed by diisopropylcarbodiimide migratory insertion into two different tantalum-benzyl bonds of 1.

Scheme 2.

Migratory insertion of diisopropylcarbodiimide into two of the tantalum-benzyl bonds of 1.

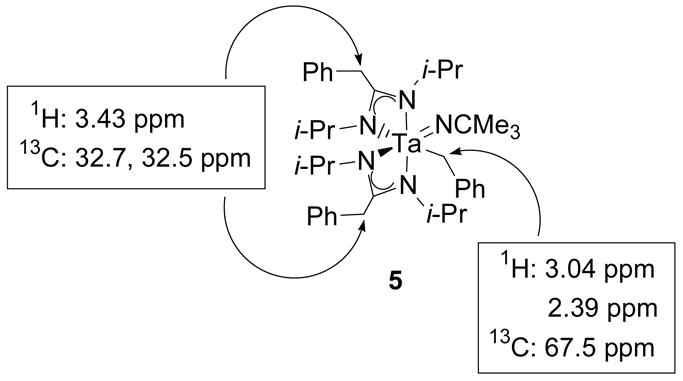

Compound 5 was identified by NMR spectroscopy. The 1H NMR spectrum of 5 contains distinct doublet resonances for all eight methyl groups of the isopropyl substituents of the amidinate ligands. These resonances initially suggested that the insertion product lacked symmetry, but further examination of the three sets of proton methylene resonances associated with the three benzyl groups of 5 provided more specific information regarding the structure of the complex. The two methylene doublets at 3.04 and 2.39 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum of 5 are coupled to each other and correlate to a single carbon resonance at 67.5 ppm in a 1H-13C HMQC experiment. This carbon resonance has a similar chemical shift to that of the benzyl methylene groups of 1 as well as other tantalum-benzyl complexes reported in the literature.39,40,47 Therefore, the methylene doublets at 3.04 and 2.39 ppm were assigned as diastereotopic geminal methylene resonances of a tantalum-coordinated benzyl group (Figure 2). The two other sets of methylene resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum of 5 overlap to form a multiplet at 3.43 ppm and correlate to two carbon resonances at 32.7 and 32.5 ppm in a 1H-13C HMQC experiment (Figure 2). These carbon methylene resonances are shifted upfield from typical tantalum-bound benzyl methylene resonances and correspond to the benzyl methylene groups of the amidinate ligands.48

Figure 2.

1H-13C HMQC correlations for the benzyl methylene resonances of compound 5.

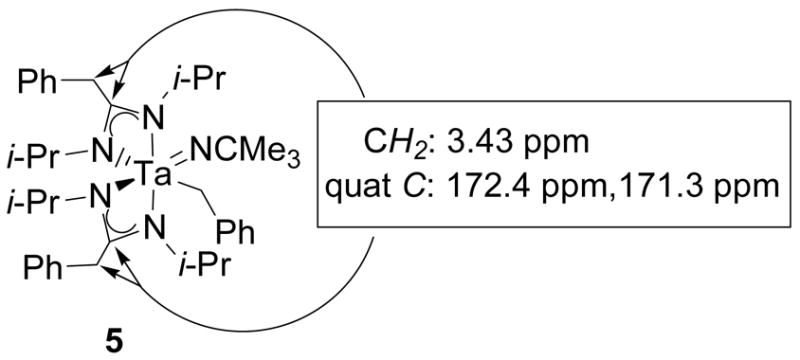

After it had been determined that two equivalents of diisopropylcarbodiimide had inserted into two of the tantalum-benzyl bonds of 1, additional spectroscopic characterization provided a more detailed picture of the structure of 5. The two sets of overlapping methylene resonances at 3.43 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum of 5 correlate to two quaternary carbon resonances at 172.4 and 171.3 ppm in a 1H-13C HMBC spectrum (Figure 3). Carbon chemical shifts between 160 and 180 ppm are characteristic of amidinate ligands.31,35,48,49 Correlation of the methylene protons of the insertion products to these resonances suggested that the imine nitrogens were coordinated to tantalum to give the amidinate ligands shown in Scheme 2. The observed asymmetry of the ancillary groups can be explained by cis-coordination of the imido functionality and the tantalum-coordinated benzyl ligand.

Figure 3.

1H-13C HMBC correlations for the amidinate ligands of compound 5.

In light of previously observed reactions between carbodiimides and early transition metal imido bonds, the insertion of diisopropylcarbodiimide into the tantalum-benzyl bonds of 1 was surprising. Nevertheless, treatment of early metal alkyl compounds with carbodiimides is a common method for the synthesis of amidinate complexes.50–53 These types of reactions are usually performed with simple transition metal starting materials such as cyclopentadienyl or halide complexes. A two step procedure involving the synthesis of a lithium salt of an amidinate ligand from a carbodiimide prior to a salt metathesis reaction with a metal-halide bond can also be used to synthesize amidinate complexes.35,49 This method has previously been used to synthesize amidinate-coordinated titanium imido compounds.54–56 Recently, however, the direct treatment of an alkyl titanium imido complex with diisopropylcarbodiimide has been reported to provide an amidinate complex.57 The similar transformation observed for compound 1 provides an efficient way to make tantalum imido complexes supported by amidinate ligands. It also shows that the imido bond of 1 is either less reactive towards carbodiimides than the imido bonds of zirconocene imido complexes or that the activity of the alkyl bond of 1 obscures the reactivity of the imido functionality.

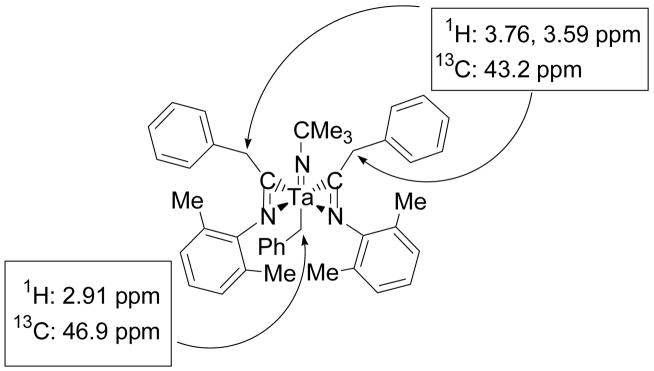

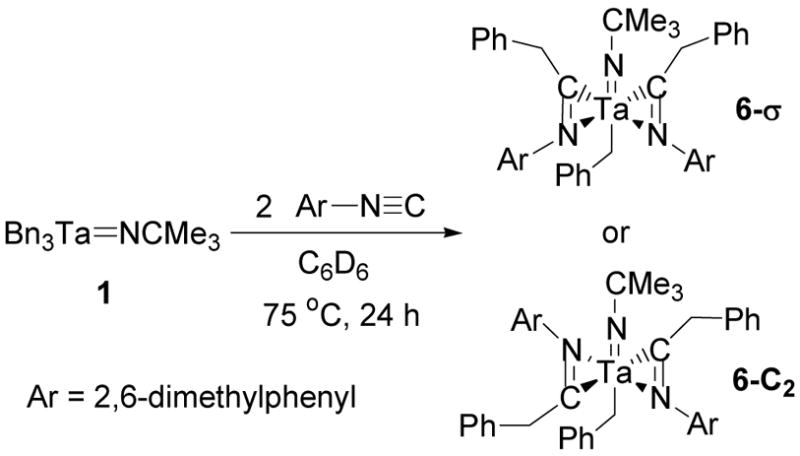

The reagent 2,6-dimethylphenylisocyanide has previously been observed to undergo a 1,1-insertion into the tantalum-imido bond of CpCl2Ta=NCMe329 and insert into the tantalum-methyl bonds of CpMe2Ta=NCMe3.26 However, when compound 1 was mixed with 2,6-dimethylphenylisocyanide no reaction occurred. When the reaction mixture was thermolyzed at 75 °C insertion of isocyanide into two tantalum-benzyl bonds provided complex 6 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Migratory insertion of 2,6-dimethylphenylisocyanide into the tantalum-benzyl bonds of 1.

Complex 6 was characterized by NMR spectroscopy. The two benzyl methylene resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum of 6 were particularly important in the structural assignment of this compound. One methylene singlet at 2.91 ppm integrates to two protons and correlates to a carbon resonance at 46.9 ppm in a 1H-13C HMQC experiment. This carbon signal is shifted upfield in comparison to many tantalum-benzyl bonds but is still within the range of several aryloxide complexes.40 These data are consistent with the assignment of a tantalum-coordinated benzyl group (Figure 4). The other methylene resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum of 6 are two doublets at 3.76 and 3.59 ppm that are coupled to each other and integrate to four protons. A 1H-13C HMQC experiment shows a correlation between these methylene doublets and a single carbon resonance at 43.2 ppm (Figure 4). This indicates that the two benzyl groups associated with these signals are equivalent. A 1H-13C HMBC experiment also correlates the methylene resonances at 3.76 and 3.59 ppm to a single imino-acyl carbon signal at 254.7 ppm and shows that the equivalent benzyl groups are attached to equivalent imino-acyl carbons. Based on these correlations, the methylene doublets at 3.76 and 3.59 ppm are assigned as the diastereotopic geminal methylene resonances of the benzyl groups that undergo insertion reactions with the isocyanide. These NMR characteristics also match other (bisimino-acyl) tantalum and zirconium complexes.58–61

Figure 4.

1H-13C HMQC correlations for the benzyl methylene resonances of compound 6.

η2-Coordination of imino-acyl ligands is common for early transition metal complexes and was assumed to be the coordination mode for insertion product 6.25,27,28,58,59 The symmetry of 6 was determined by the observation of only one imino-acyl carbon resonance and equivalent diastereotopic methylene resonances for both benzyl groups of the imino-acyl ligands. In order for the imino-acyl groups of 6 to be equivalent, either a mirror plane or a C2 axis needs to include the tantalum-coordinated benzyl group, the tantalum atom, and the imido ligand (Scheme 3). A crystal structure of a similar tantalum aryloxide complex has been reported in which the imino-acyl ligands have a cis-relationship.58 However, the structure of the zirconium analogue of the aryloxide complex has symmetrical imino-acyl ligands that are related by a C2 rotation.59 NMR spectroscopy cannot distinguish between these two isomers and we were unable to determine which isomer was the product of the reaction shown in Scheme 3. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compound 6 also show two distinct methyl resonances for the 2,6-dimethylphenyl groups of the imino-acyl ligands. These resonances indicate that the rotation of these aryl functionalities is hindered in this molecule.

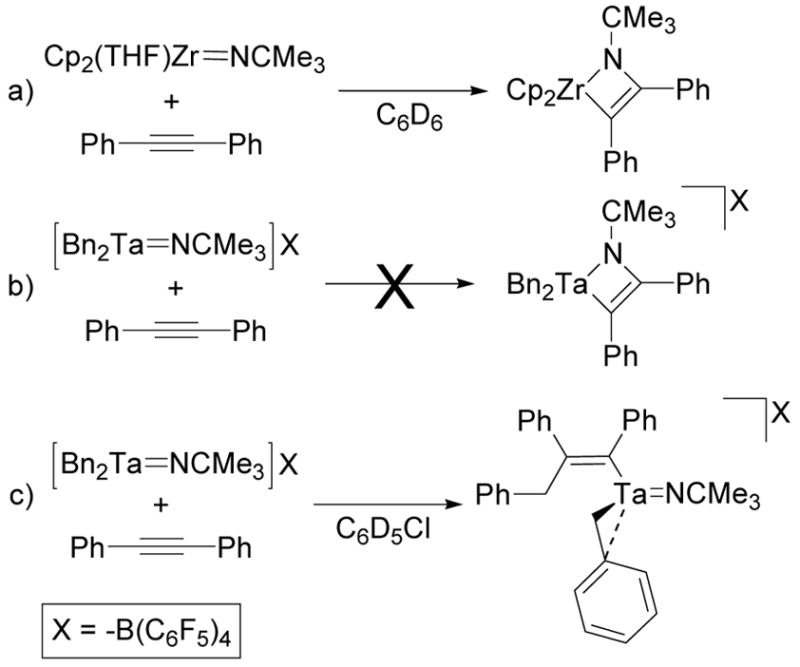

In order to extend the reactivity and selectivity observed for the reactions between compound 1 and carbodiimides and isocyanides to less active unsaturated substrates, compound 1 was treated with diphenylacetylene. Although this substrate reacts readily with zirconocene imido complexes at room temperature, no reaction was observed between compound 1 and this internal alkyne at 25 °C or 75 °C.

Synthesis of [Bn2Ta=NCMe3][BnB(C6F5)4] (7)

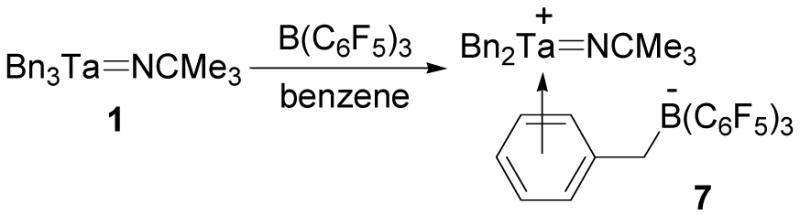

In an effort to increase the reactivity of the Ta=NR bonds of 1, cationic tantalum imido complexes were synthesized. Trispentafluorophenylborane is a common alkide abstraction reagent that has been used to synthesize a variety of early metal cations including tantalum cations.33,62–65 This Lewis acid is often used as a cocatalyst for Ziegler-Natta polymerizations to increase the reactivity of transition metal catalysts by forming the corresponding cationic alkyl species.66 This reagent has also been used as an activator for polymerizations catalyzed by tantalum imido complexes.33 Treatment of a benzene solution of 1 with B(C6F5)3 gave the yellow, analytically pure cationic tantalum imido complex 7 (Scheme 4). This compound dissolves in chloro- or fluorobenzene, polymerizes THF, and decomposes in CH2Cl2.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of cationic complex 7.

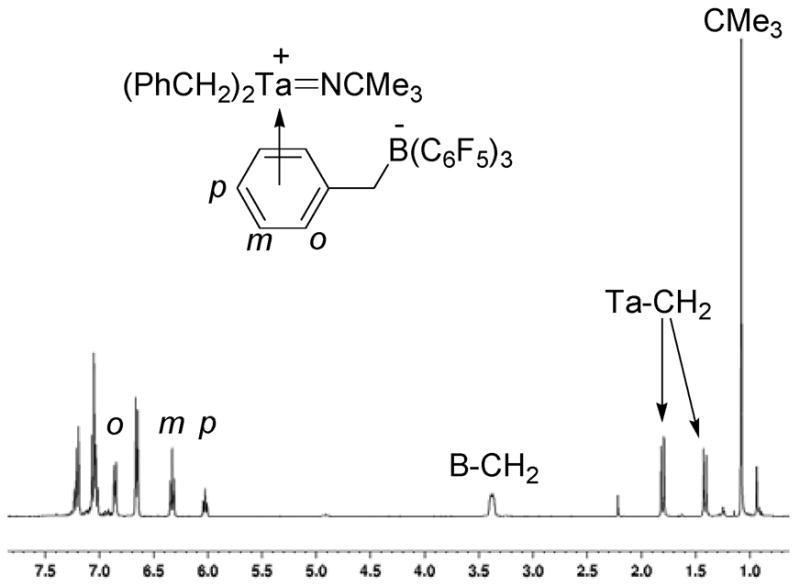

The structure of cation 7 was determined by NMR spectroscopy and comparison to similar zirconium complexes.62,67 The BnB(C6F5)3- anion was initially identified by a characteristic tetracoordinate boron resonance in the 11B NMR spectrum at −12.6 ppm. The chemical shift for the boron resonance of B(C6F5)3 appears at 59.7 ppm. A 1H-11B HMQC experiment also correlates the boron resonance at −12.6 ppm to a broad methylene singlet in the 1H NMR spectrum at 3.35 ppm. This proton methylene resonance is associated with the abstracted benzyl group and is broad due to the quadrupole of the neighboring boron nucleus. The 1H NMR spectrum of 7 also contains a set of methylene doublets at 1.78 and 1.41 ppm that are coupled to each other and integrate to four protons. These resonances correlate to a single carbon resonance at 48.3 ppm in a 1H-13C HMQC experiment and correspond to the diastereotopic geminal methylene resonances of the equivalent tantalum-bound benzyl groups.

A striking aspect of the 1H NMR spectrum of 7 is a set of aryl resonances that are shifted approximately 1 ppm upfield (Figure 5). These resonances integrate for a single arene and consist of a meta-resonance at 6.83 ppm, an ortho-resonance at 6.31 ppm, and a para-resonance at 6.01 ppm. These upfield aryl resonances are characteristic of η6-arene-coordination of a borane-abstracted benzyl group to an electrophilic metal-center and suggest that 7 is stabilized by this type of coordination.67–71 The chemical shift differences between the meta- and para-19F NMR resonances of BnB(C6F5)3 anions have also been used to identify η6-coordination of abstracted benzyl groups. Differences greater than 3.5 ppm indicate coordination of the abstracted arene to the electrophilic metal center and differences less than 3 imply the presence of a free anion.72 The chemical shift difference between the meta- and para-19F resonances for 7 is 4.1 ppm and agrees with the assignment of η6-coordination of the abstracted benzyl group.

Figure 5.

1H NMR spectrum of compound 7 showing the upfield chemical shifts of the η6-coordinated aryl group.

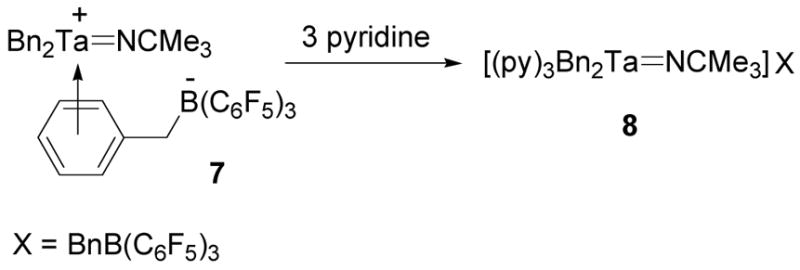

The coordination of the benzyl borate counterion of compound 7 can be displaced by three equivalents of pyridine to give the Lewis base adduct 8 (Scheme 5). This displacement was identified by the appearance of a set of coordinated pyridine resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum as well as specific 1H and 19F NMR spectroscopic characteristics which were consistent with a non-coordinated benzyl borate anion. In contrast to 7, the 1H NMR spectrum of 8 did not contain a set of upfield shifted aryl resonances and the difference between the meta- and para-19F NMR resonances was only 2.8 ppm which is significantly smaller than the values observed for η6-coordination. One and two equivalents of pyridine also formed coordination complexes with 7 but these compounds had broad 1H NMR signals for the pyridine and the benzyl borate anion, suggesting that a fluxtional process was exchanging these donor ligands.

Scheme 5.

Diplacement of η6-coordination of the benzyl borate counterion with pyridine.

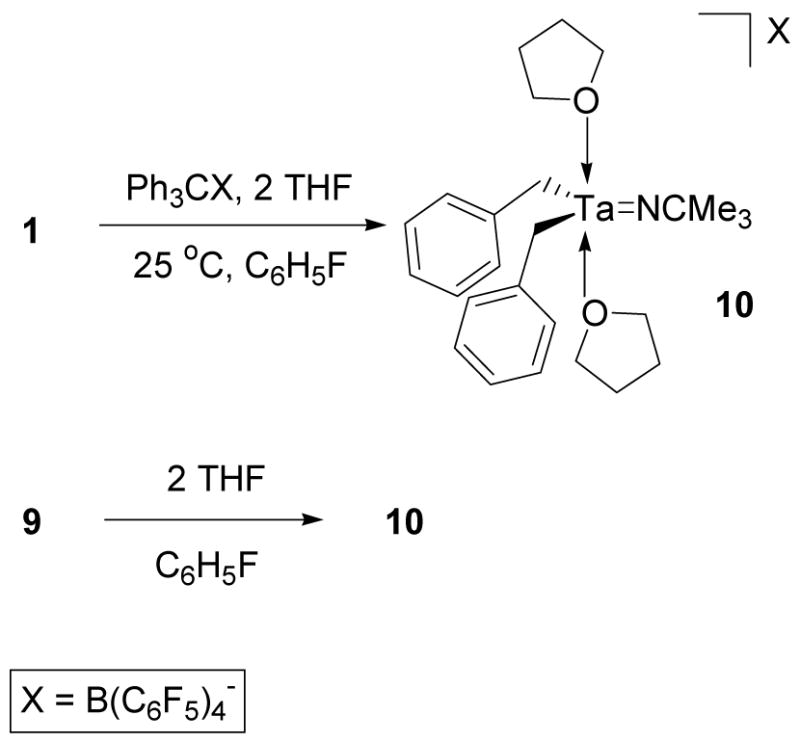

Synthesis of [Bn2Ta=NCMe3][B(C6F5)4] (3) and Reactivity with THF and Unsaturated Hydrocarbons

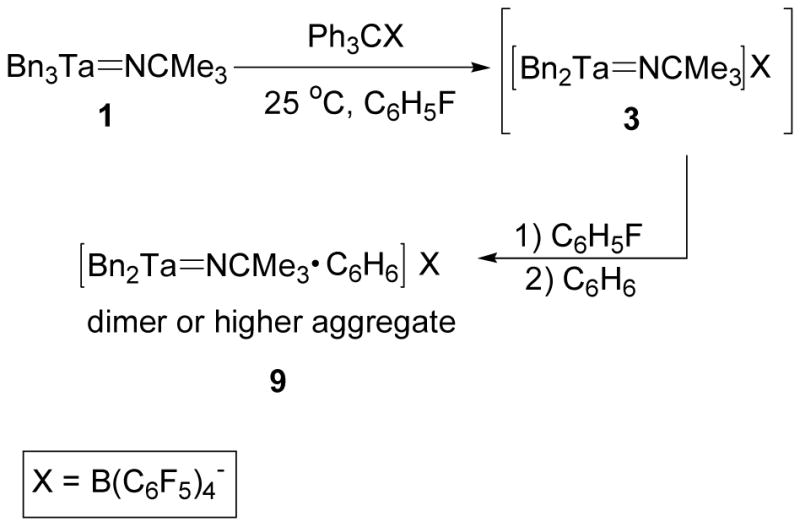

The zwitterion 7 is stabilized by η6-coordination of the benzyl borate anion and the salt 8 is stabilized by Lewis base coordination. In order to synthesize a cationic tantalum imido complex without the stabilizing effect of η6-aryl or pyridine coordination, the alkide abstraction reagent [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] was used to abstract a benzyl group from 1.36,37,73

Treatment of 1 with [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] in fluorobenzene resulted in the precipitation of a brown oil. After removal of solvent, the crude product was washed with benzene to remove the 1,1,1,2-tetraphenylethane byproduct and ultimately yielding a dark brown glass which was insoluble in chlorobenzene, fluorobenzene, and benzene, polymerized THF, and decomposed in CH2Cl2. These characteristics prevented solution NMR characterization of this complex. The results of an elemental analysis of the salt 9 were consistent with the molecular formula [Bn2Ta=NCMe3][B(C6F5)4]·C6H6. Based on these characteristics, 9 was identified as an aggregate of cation 3 and benzene (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of 3 and Aggregation in Nonpolar Solvent to Form 9.

In order to prevent the aggregation of 3, compound 1 was treated with [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] in the presence of two equivalents of THF. Lewis base coordination prevented aggregation and 10 was isolated as an orange foam that was soluble in chloro- or fluorobenzene (Scheme 7). The results of an elemental analysis of 10 were consistent with the proposed chemical formula and all 1H and 13C NMR data indicated the coordination of two equivalents of THF to a cationic tantalum center with two equivalent benzyl groups.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of 10 and Aggregation Reversal with THF.

The 1H NMR resonances corresponding to the benzyl methylene and THF functionalities of complex 10 are broad at 25 °C. This characteristic is most likely associated with a trigonal bipyramidal isomerization process that is slow on the NMR time scale at 25 °C. When a solution of 10 is cooled to −31 °C, this fluxional process slows, the THF resonances sharpen, and the benzyl methylene resonances decoalesce into two broad singlets. Due to the fact that the aryl resonances of the two benzyl groups of 10 are equivalent, the inequivalent methylene resonances that are observed at low temperature are most likely diastereotopic geminal methylene signals. Additional cooling of the sample could not be pursued due to the freezing point of chlorobenzene-d5 (−40 °C) as well as the lack of solubility of 10 or its reactivity with other solvents. The fluxional spectroscopic characteristics observed for 10 are in contrast to the sharp NMR spectra observed for 7 and 8.

In addition to preventing the aggregation of 3 by trapping the cationic tantalum complex during synthesis, THF can also be used to reverse the aggregation of 3. Treatment of 9 with two molar equivalents of THF in chlorobenzene-d5 provided a 1H NMR spectrum identical to that of 10 (Scheme 7). One equivalent of THF is sufficient to break up the aggregate; however, the NMR data for the mono-coordinated THF product are extremely broad. Addition of two equivalents of the Lewis base facilitate the interpretation of the NMR spectrum.

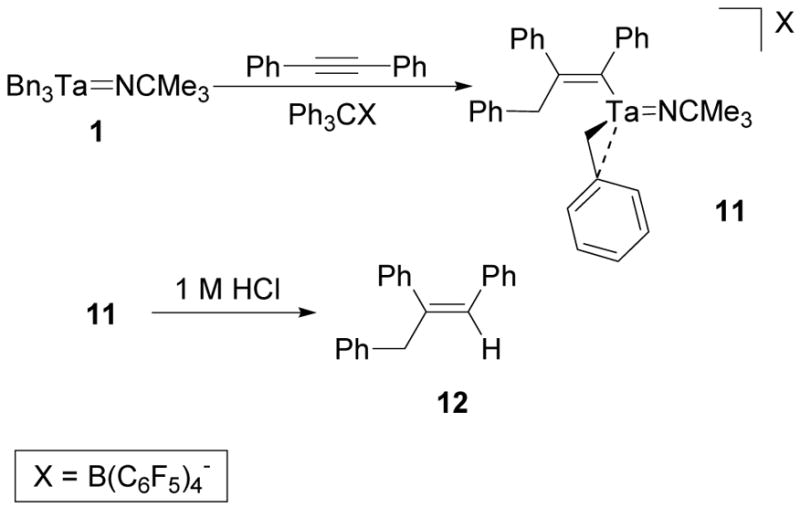

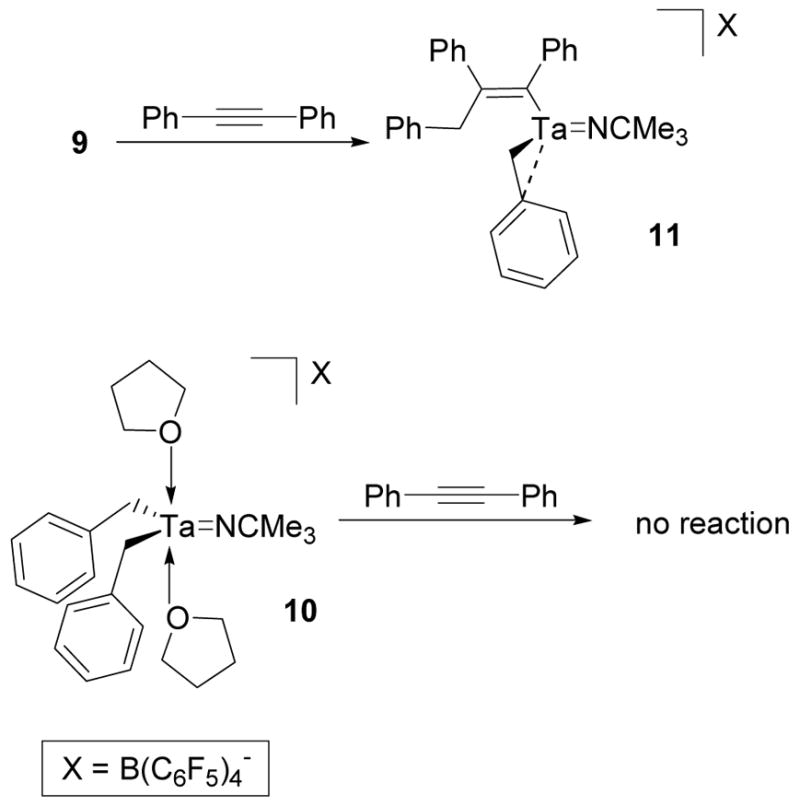

After observing that 3 could be trapped as a Lewis base adduct, the cation was synthesized in the presence of diphenylacetylene to determine whether the complex would favor aggregation or a reaction with the alkyne. When a fluorobenzene solution of 1 and diphenylacetylene was mixed with [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4], the reaction mixture immediately turned red and the migratory insertion product 11 was isolated (Scheme 8). An elemental analysis of the isolated product was consistent with the predicted molecular formula and the details of its structure were confirmed by NMR spectroscopy.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of the Diphenylacetylene Migratory Insertion Product of 3.

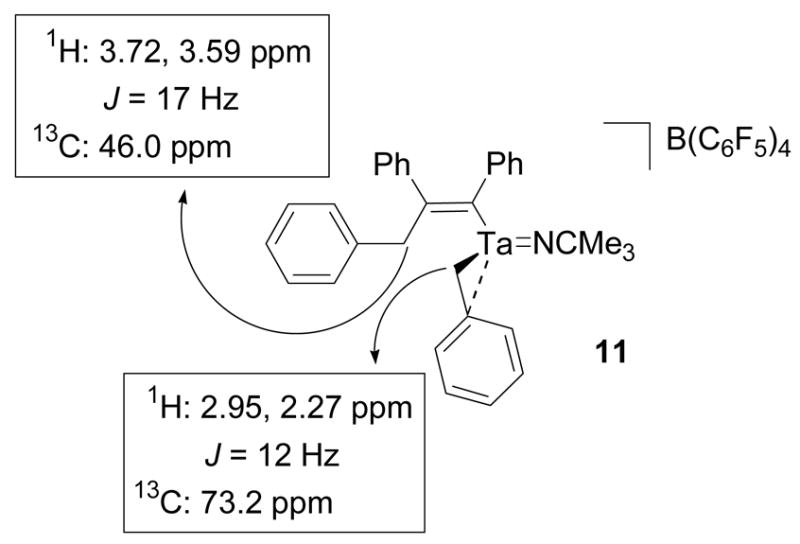

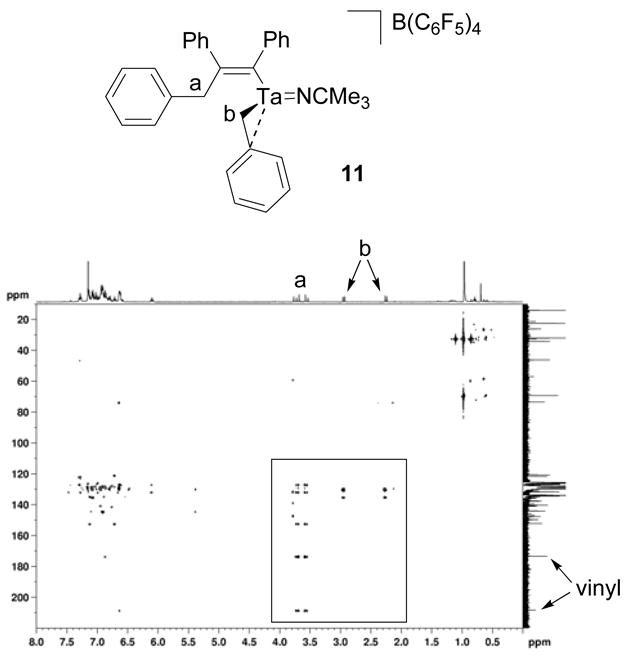

Two sets of inequivalent benzyl methylene resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum of 11 initially indicated that diphenylacetylene had inserted into a single tantalum-benzyl bond of 3. The set of methylene resonances at 2.95 and 2.27 ppm correlate to a carbon resonance at 73.2 ppm in a 1H-13C HMQC experiment and are consistent with a tantalum-coordinated benzyl group (Figure 6).40,47 The set of methylene resonances at 3.72 and 3.59 ppm correlate to a carbon resonance at 46.0 ppm in a 1H-13C HMQC experiment and are associated with the benzyl group that participated in the migratory insertion reaction (Figure 6).67 The methylene doublets at 3.72 and 3.59 ppm also correlate to five aryl carbon resonances in a 1H-13C HMBC experiment (Figure 7). These correlations include the quaternary carbon resonances at 208.2 and 173.2 which match the alkenyl carbon signals of a similar diphenylacetylene insertion product of a zirconium benzyl complex.67 The proton methylene signals at 2.95 and 2.27 ppm do not exhibit similar correlations. In order to confirm the structural assignment of the insertion product, complex 11 was hydrolyzed by aqueous HCl and the organic components were extracted into ether. The ether layer was then analyzed by GC-MS. The GC-MS trace contained a single peak that corresponded to a molecular ion with a 270 m/z which matches the molecular weight of alkene 12 and agrees with the structural assignment of 11 (Scheme 8). The Z-alkene geometry was assumed based on the stereochemical requirements for migratory insertion and observations made on similar alkyne and alkene insertion reactions with other early metal complexes.67,74 This assignment could not be confirmed by a 2D NOESY NMR experiment due to the complication of overlapping aryl resonances.

Figure 6.

1H-13C HMQC correlations for the benzyl methylene resonances of compound 11.

Figure 7.

1H-13C HMBC spectrum of compound 11.

Cation 11 is a coordinatively unsaturated, ten-electron complex. Based on previous studies of similar electronically unsaturated complexes, it seemed likely that one of the arenes of 11 was coordinated to the electrophilic metal center. The two possible arene coordination modes for this complex are η6-coordination of the benzyl group of the alkenyl ligand or coordination of the ipso-carbon of the benzyl ligand.67,68,70,75–78 Arene coordination of zirconium insertion products have characteristic downfield aryl resonances for the meta- and para-protons of the coordinated arene.67,68,70 Coordination of the ipso-carbon of metal-bound benzyl groups is usually identified by upfield ortho- and para-aryl resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum and an upfield ipso-carbon signal in the 13C NMR spectrum.62,70,78 The 1H NMR spectrum of complex 11 has a para-aryl resonance at 6.13 ppm, a multiplet of aryl resonances at 6.64 ppm, and an ipso-carbon resonance at 134.8 ppm. These data suggest that the benzyl ligand of 11 is η2-coordinated to the metal center as illustrated in Scheme 8.

In addition to trapping cation 3 as an insertion product, diphenylacetylene can also be used to reverse the aggregation of 3. When 9 was mixed with one equivalent of diphenylacetylene in chlorobenzene-d5, this reaction mixture exhibited an identical 1H NMR spectrum to that of 11 (Scheme 9). The reversal of cation dimerization by treatment with an alkene has previously been observed by Horton.68 However, diphenylacetylene cannot be used to displace THF from 10. When 10 was mixed with diphenylacetylene, no reaction was observed (Scheme 9).

Scheme 9.

Reversal of the Aggregation of 3 with Diphenylacetylene and the Inability of Diphenylacetylene to Displace THF from 10.

The observation that diphenylacetylene undergoes a migratory insertion reaction with a benzyl ligand of 3 at room temperature showed that this cation is more reactive than compound 1 but that the imido groups of both complexes are spectator ligands. The migratory insertion of diphenylacetylene into the tantalum-benzyl bond of 3 is an example of a single propagation step of the type that occurs in Ziegler-Natta polymerization.79 Similar single insertions have been studied with several early metal systems in order to better understand polymerization processes and to design more advanced catalysts.67,68 Tantalum imido complexes have also been used to catalyze alkene polymerizations and these systems are thought to proceed via a Ziegler-Natta mechanism. The imido group is assumed to be a spectator ligand in tantalum imido catalyzed polymerization processes; however, mechanistic investigations have not yet been reported for these catalysts.32–35 The migratory insertion of diphenylacetylene into the tantalum-benzyl bond of 3 suggests that the imido group of tantalum imido polymerization catalysts is truly a spectator ligand and that these types of transformations are directly analogous to Group 4 metallocene catalyzed processes.

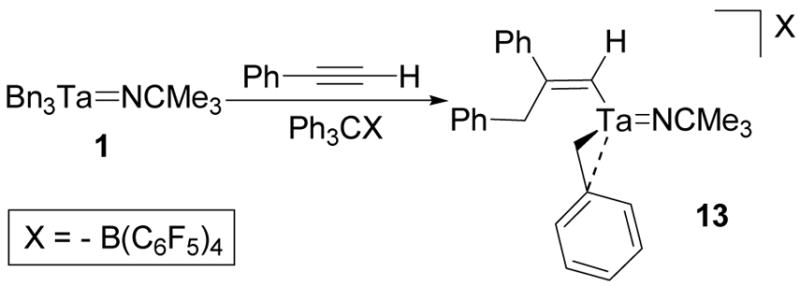

After observing the migratory insertion of diphenylacetylene, cation 3 was treated with phenylacetylene. This substrate could potentially participate in an analogous insertion or protonate either the imido ligand or a benzyl group of 3 to give an acetylide complex.36 Treatment of a fluorobenzene solution of 1 and phenylacetylene with [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] immediately formed the dark red migratory insertion product 13 (Scheme 10). An elemental analysis of the isolated product was consistent with the predicted molecular formula and the structure of the complex was determined by NMR spectroscopy.

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of the phenylacetylene migratory insertion product of 3.

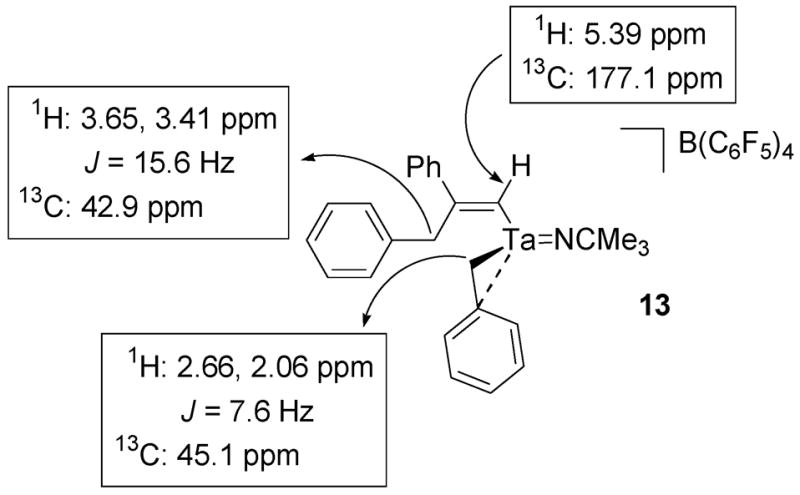

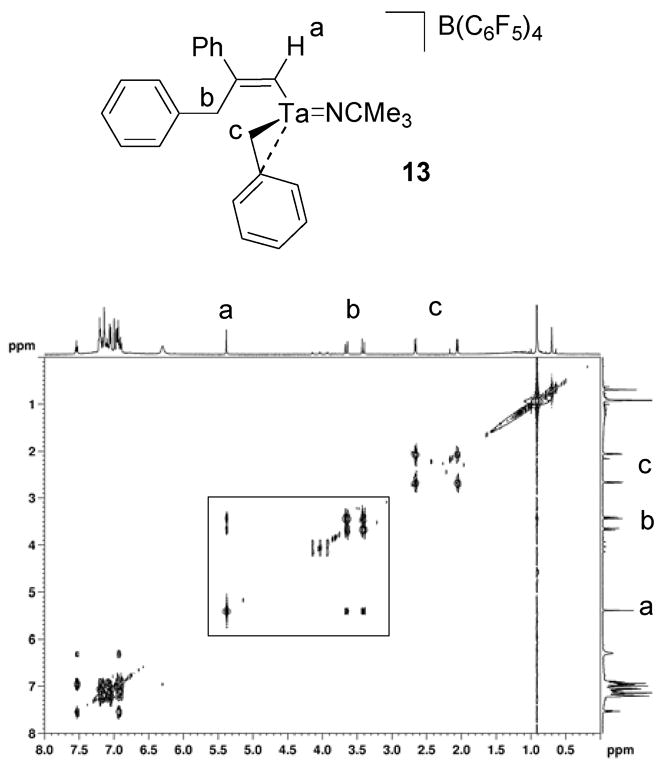

The NMR spectra of 13 are analogous to the spectra of 11. The 1H NMR spectrum of 13 contains two different sets of benzyl methylene resonances and a vinyl singlet at 5.39 ppm. The two sets of methylene doublets are consistent with a single migratory insertion product and the vinyl singlet is characteristic of a terminal acetylene insertion. The set of methylene doublets at 2.66 and 2.06 ppm correlate to a carbon resonance at 45.1 ppm in a 1H-13C HMQC experiment and are associated with the tantalum-coordinated benzyl group (Figure 8). The set of methylene doublets at 3.65 and 3.41 ppm correlate to a carbon resonance at 42.9 ppm in a 1H-13C HMQC experiment and are associated with the benzyl group that participates in the insertion reaction (Figure 8). These assignments are based on the fact that the methylene resonances at 3.65 and 3.41 ppm also correlate to five aryl carbon resonances in a 1H-13C HMBC experiment as well as to the alkenyl carbon resonances at 177.1 ppm and 169.1 ppm. The vinyl proton resonance at 5.39 ppm also correlates to the methylene resonances at 3.65 ppm and 3.41 ppm in a 1H-1H TOCSY experiment (Figure 9) and to the carbon signal at 177.1 ppm in a 1H-13C HMQC experiment (Figure 8). The lack of splitting between the vinyl resonance and the benzyl methylene resonances of the alkenyl ligand suggest that the insertion reaction gives the sterically favored regiochemistry illustrated in Scheme 10.

Figure 8.

1H-13C HMQC NMR data for compound 13.

Figure 9.

1H-1H TOCSY spectrum for compound 13.

Compound 13 is also a coordinatively unsaturated complex that can potentially be stabilized by arene coordination. The 1H NMR spectrum of 13 contains a broad upfield aryl resonance at 6.29 ppm that integrates for two protons and a downfield triplet at 7.54 ppm that integrates for one proton. The downfield resonance could be associated with an η6-coordinated arene of the alkenyl ligand; however, the lack of a corresponding downfield meta-resonance makes this assignment unclear.67,68 The ortho-resonances at 6.29 ppm and an ipso-carbon resonance at 134.2 ppm suggest that η2-coordination of a benzyl ligand may also be present in the structure of complex 13.70,78 The coupling constant of the geminal methylene protons of the tantalum-coordinated benzyl group is 7.6 Hz. This coupling constant value is low for geminal methylene resonances and suggests that these protons are separated by a bond angle that is larger than 109.5°.80 This type of distortion is also consistent with η2-coordination of the tantalum-benzyl ligand and this interaction has been illustrated in Scheme 10.

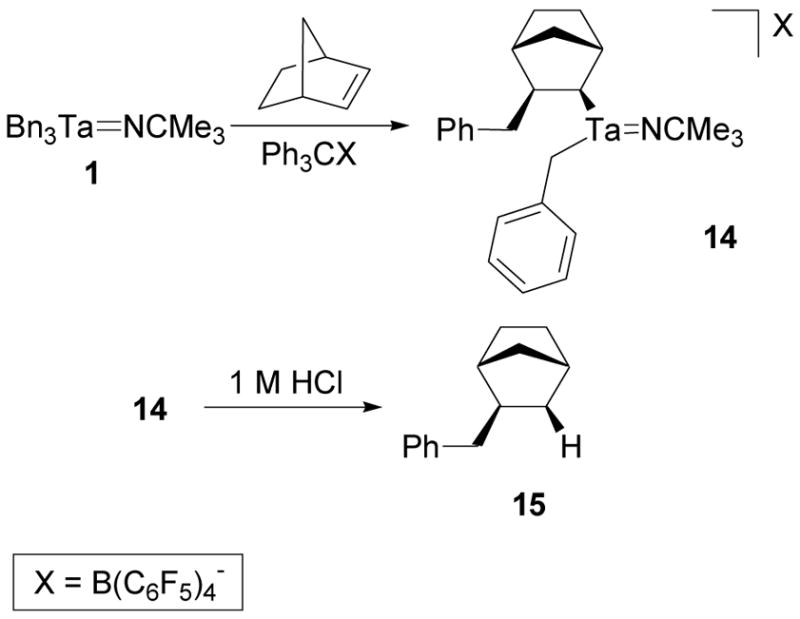

Treatment of cation 3 with alkenes provides migratory insertion products similar to 11 and 13. These reactions are analogous to previously studied insertion reactions of monsubstituted alkenes with Group 4 benzyl complexes.68,75 When 1 was mixed with [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] in the presence of norbornene, complex 14 was isolated (Scheme 11). The 1H NMR spectrum of 14 contains methylene resonances for the tantalum-coordinated benzyl group at 2.32 ppm, benzyl methylene resonances for the insertion product at 2.61 and 2.32 ppm, a tantalum-coordinated methine resonance at −1.84 ppm, and resonances corresponding to an unsymmetrical norbornyl fragment. The carbon resonances corresponding to the norbornyl fragment only correlate to the methylene resonances at 2.61 and 2.32 ppm in a 1H-13C HMBC spectrum and show that the insertion reaction occurs at a single benzyl group. The coupling constant of the tantalum-coordinated methine resonance is 8.8 Hz which suggests that this proton is in a syn-relationship to the neighboring methine proton and that the migratory insertion proceeds via the expected syn-addition to the alkene. 1H-1H NOESY correlation of the tantalum-coordinated norbornyl methine resonance at −1.84 ppm to the benzyl methylene resonance of the alkenyl group at 2.32 ppm and the methylene bridge proton at 0.85 ppm strongly suggests that the insertion occurs on the sterically favored, exo-face of the alkene. Hydrolysis of 14 and analysis of the organic components by GC-MS showed a single peak that corresponded to a molecular ion with a 243 m/z which agrees with the molecular weight of alkene 15.

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of 14 via a Migratory Insertion Reaction of Norbornene with 3.

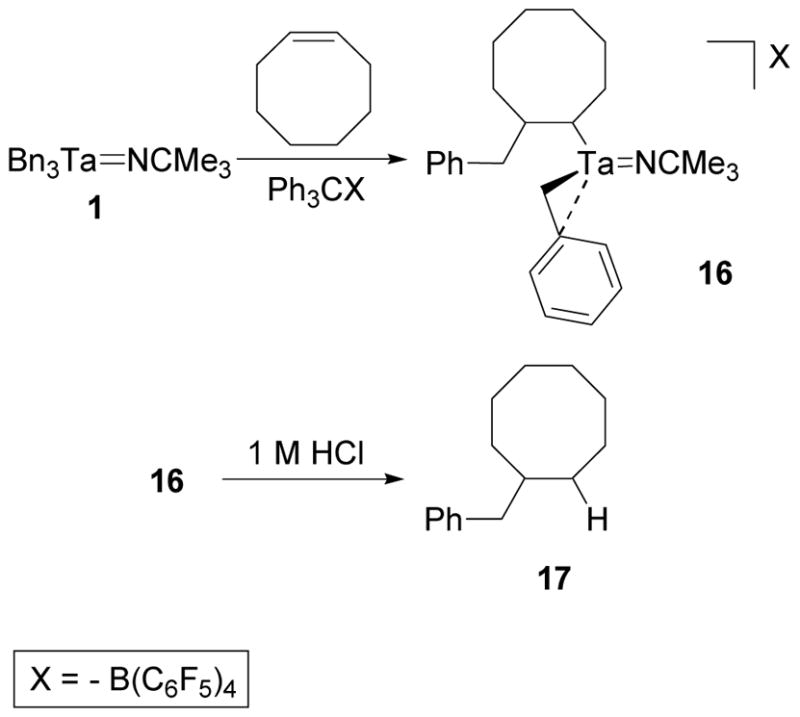

Similarly, when 1 was treated with [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] in the presence of cis-cyclooctene, complex 16 was isolated (Scheme 12). The 1H NMR spectrum of 16 contains benzyl methylene resonances for the tantalum-coordinated benzyl group at 2.58 and 2.06 ppm and a tantalum-coordinated methine resonance at −1.37 ppm. The methylene resonances of the insertion product and the other methine resonance overlap as a multiplet at 2.20 ppm. As expected for the single insertion product, a 1H-13C HMBC spectrum of 16 correlates the carbon resonances of the octyl group to the multiplet at 2.20 ppm but not to the methylene resonances of the tantalum-coordinated benzyl group. These spectral characteristics are similar to those observed for 14 and are consistent with the structure depicted in Scheme 11. Hydrolysis of 16 and analysis of the organic components by GC-MS showed a single peak that corresponded to a molecular ion with a 202 m/z which agrees with the molecular weight of alkene 17.

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of 16 via a Migratory Insertion Reaction of Cis-cyclooctene with 3.

Complexes 14 and 16 are coordinatively unsaturated and can potentially exhibit a type of arene coordination similar to that observed in 11 and 13. The 1H NMR spectrum of 14 contains an upfield ortho-aryl resonance at 6.25 ppm which is consistent with η2-coordination of the tantalum-coordinated benzyl group; however, the methylene resonances of the tantalum-coordinated benzyl group of 14 are not distorted and a corresponding upfield ipso-carbon resonance was not observed. Therefore, it is unclear whether the tantalum coordination sphere of 14 includes η2-coordination of the benzyl ligand. The 1H NMR spectrum of 16 contains an upfield ortho-aryl resonance at 6.40 ppm as well as a coupling constant of 8 Hz for the methylene resonances of the tantalum-coordinated benzyl group. These characteristics are consistent with the distortion caused by η2-coordination of a tantalum-coordinated benzyl group as illustrated in Scheme 12.

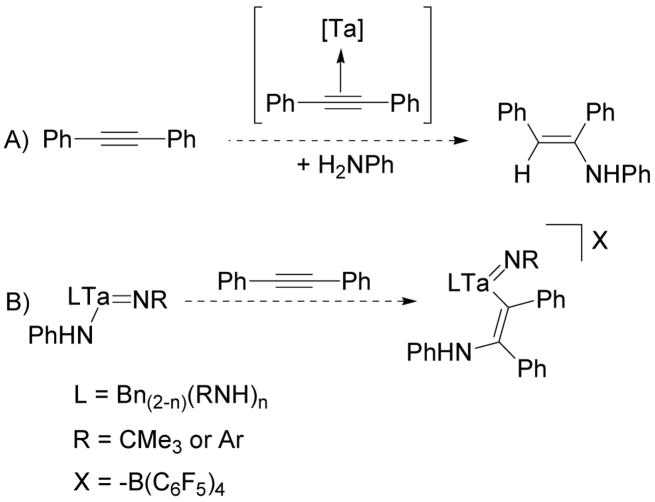

Implications for Hydroamination

Previously, we reported that 1, 2, and 3 are competent catalysts for the hydroamination of alkynes with anilines.38 Subsequently, we showed that [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] and [PhNH3][B(C6F5)4] are catalysts for alkene hydroamination reactions with arylamines81 but are inactive for alkynes.82 These data suggested that the alkyne hydroamination reactions catalyzed by 1–3 were proceeding by a metal-catalyzed pathway.

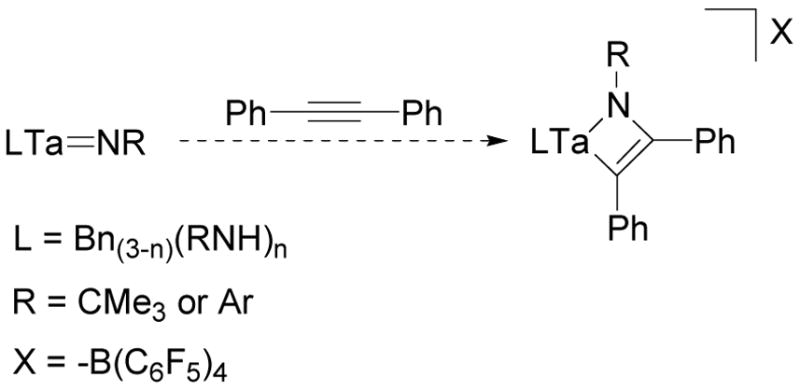

Studies of a variety of well-known hydroamination catalysts of the electropositive early transition metals83–85 led to the consideration of two potential mechanisms for the N-H additions observed at these electrophilic, tantalum(V) centers: 1) [2+2] cycloadditions between the imido ligand and the alkyne followed by amine protonation of the resulting metallacycle;11,86–91 and 2) metal-amide bond insertion reactions followed by amine protonation of the resulting metal-carbon bonds.92–96 Initially we assumed that the hydroamination reactions catalyzed by 1–3 were proceeding via the [2+2] cycloaddition route because this pathway had previously been strongly supported for several other early metal imido complexes (Scheme 13a).11,12,86,97 Conversely, the stoichiometric reactions discussed above have shown that these metallacyclic intermediates are not accessible to neutral and cationic, alkyl tantalum imido complexes (Scheme 13b and 13c). Therefore, complexes 1–3 must either be precatalysts for active complexes that can access [2+2] metallacyclic intermediates or function as catalysts or precatalysts for an alternative mechanistic pathway.

Scheme 13.

Different Modes of Alkyne Reactivity for Zirconcene Imido and Alkyl Tantalum Imido Complexes

If compounds 1–3 are precatalysts for active catalytic species that undergo [2+2] imido cycloadditions, there are several transformations that these alkyl tantalum imido complexes can undergo that may increase the likelihood alkyne metallacycle formation. Alkyl-amide ligand exchange is likely to occur in the presence of the amine substrate required for hydroamination.97–100 Amide imido or mixed alkyl-amide imido complexes may favor [2+2] cycloaddition reactions over the alkyl imido compounds discussed above due to the corresponding change of electronics at the metal center (Scheme 14). Imido exchange may also occur under the reaction conditions,101 and exchange of the t-butyl group for a less sterically encumbered phenyl group may also favor metallacycle formation.

Scheme 14.

Potential Metallacycle Formation with Mixed Alkyl/Amide Complexes

Alternatively, complexes 1–3 may be participating in hydroamination reaction mechanisms where the imido ligand is a spectator. As mentioned above, a recent report from our laboratory has shown that Brønsted acids catalyze the hydroamination of several different alkenes with anilines.81 This suggests that the tantalum imido catalysts may be functioning simply as Lewis acids and activating the alkyne substrates towards nucleophilic attack by the amine (Scheme 15a). However, this scenario is unlikely due to the fact that Brønsted acids and TaCl5 are inactive catalysts for alkyne hydroamination reactions.38,81,82 Alternatively, it is possible that hydroamination takes place by insertion of an alkyne into a tantalum-amide bond, as observed for lanthanide-catalyzed hydroaminations (Scheme 15b).92 The required tantalum-amide bond for this transformation can be formed by attach upon a tantalum alkyl ligand by aniline that is present in the reaction mixture. Future work will involve determining which of these mechanistic pathways is active for the reported hydroamination reactions, whether the alkyl tantalum imido complexes are precatalysts, and if the imido bond is involved in the catalytic process.

Scheme 15.

Potential Hydroamination Mechanisms that do not Involve the Tantalum Imido Bond

Summary

Tribenzyl tantalum imido compound 1 undergoes migratory insertion reactions with isocyanides and carbodiimides to form (bisamidinate) and (bisimino-acyl) complexes. This compound can also be used to synthesize the cationic complexes 7 and 3 with the alkide abstraction reagents B(C6F5)3 and [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4], respectively. Complex 3 undergoes migratory insertion reactions with diphenylacetylene, phenylacetylene, norbornene, and cis-cyclooctene at the tantalum-benzyl bond to form 11, 13, 14, and 16, respectively. These insertions reactions are representative of the propagation step of Ziegler-Natta polymerizations and support the current hypothesis for the mechanism of alkene polymerizations catalyzed by tantalum imido complexes. The heterocumulene and unsaturated hydrocarbon insertion reactions of 1 and 3, respectively, show that the tantalum imido functionalities of neutral and cationic alkyl tantalum imido complexes are spectator ligands. Nevertheless, the tantalum-alkyl bonds of these complexes are highly reactive in the presence of these ancillary groups. These stoichiometric transformations imply that complexes 1–3 are either precatalysts for hydroamination reactions that proceed via metallacyclic intermediates or that the imido ligand of these complexes is not involved in the hydroamination reactions that they have been observed to catalyze. Future work will involve a detailed investigation of the mechanism of hydroamination reactions catalyzed by neutral and cationic tantalum complexes.

Experimental

General Information

All reactions and manipulations, unless otherwise noted, were carried out in an inert atmosphere (N2) glovebox at 10 °C or using standard Schlenk and high vacuum techniques. All glassware was dried in an oven at 150 °C for at least 12 h prior to use or was flame dried under vacuum. Magnetic stirring was used when necessary. All reactions and manipulations involving compounds with benzyl ligands were done in the absence of light by using aluminum foil to cover reaction vessels or by turning the lights off in the glovebox. After several hours of light exposure, of the color of these compounds begins to darken and bibenzyl can be observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Pentane, hexane, diethyl ether, benzene, toluene, tetrahydrofuran and methylene chloride were dried and purified by passage through a column of activated alumina under N2 pressure, sparging with N2 and storage over 4Å sieves.102 Fluorobenzene, diisopropylcarbodiimide, phenylacetylene, and cis-cyclooctene (Aldrich) were distilled from CaH2 prior to use. Diphenylacetylene (Aldrich) was sublimed. Norbornene (Aldrich) was vacuum transferred. PhCH2MgCl, (CH3)3CCH2MgCl, and 2,6-dimethylphenylisocyanide (Aldrich) were purchased and used without further purification. Compound 4,20 B(C6F5)3,103 and Ph3CB(C6F5)4,104 were prepared according to published protocols. Deuterated solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. Benzene-d6 was vacuum transferred from purple Na/benzophenone and degassed with 3 freeze-evacuation-thaw cycles. Chlorobenzene-d5 was vacuum transferred from CaH2 and degassed with 3 freeze-evacuation-thaw cycles. 1H and 13C spectra were recorded on Bruker AVQ-400 (400 MHz), AV-400 (400 MHz), and DRX-500 (500 MHz) spectrometers as indicated. 1H NMR chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to residual protiated solvent (C6D6, 7.15; C6D5Cl, 6.99 (o-CH)) or an external standard of CH2Cl2 in C6D6 (4.42). Data are reported as follows: (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, hept = heptet, m = multiplet; coupling constant(s) in Hz; integration; assignment). Chemical shifts were assigned with the aid of DEPT 135 experiments as well as 1H-13C HMQC (AV-400, pulse program: hmbcgplpndqf), 1H-1H TOCSY (DRX-500, pulse program: mlevtp.UCB), and 1H-13C HMBC (DRX-500, pulse program: inv4gpph) experiments where necessary. NMR tubes were sealed on a high vacuum line using a Cajon Ultra Torr reducing union. Merck silica gel, 60 Å, 230–400 mesh, grade 9385 was used for filtering samples prior to GC-MS analysis. Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectroscopy (GC-MS) data were obtained using an Agilent Technologies Instrument 6890N GC (column #HP-5MS, 30.0m × 250μm × 0.25 μm calibrated) and 5973N MS. Elemental analyses were performed at the UC-Berkeley Microanalytical facility with a Perkin Elmer 2400 Series II CHNO/S Analyzer.

Bn3Ta=NCMe3 (1)

A slurry of 3.51 g (6.79 mmol, 1.0 equiv) of (py)2Cl3Ta=NCMe3 (4) in Et2O (200 mL) was cooled to −78 °C with an IPA/dry ice bath and treated with 20.4 mL (20.40 mmol, 3.0 equiv) of PhCH2MgCl (1.0 M in Et2O). The reaction mixture was covered in aluminum foil and allowed to stir for 8 h while warming to 25 °C. Volatile materials were removed from the reaction mixture under vacuum to give a light yellow solid. The solid was extracted with 150 mL of toluene and separated from the insoluble MgCl2 by cannula filtration. The toluene was removed from the filtrate under vacuum to give 1 as a bright yellow solid (2.68 g, 5.10 mmol, 75%). Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from a concentrated solutions of ether at −40 °C. 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 7.02 (m, 9H, ArH), 6.68 (m, 6H, ArH), 1.66 (s, 6H, CH2Ph), 1.39 (s, 9H, CMe3). 13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 136.4 (Ar), 130.1 (Ar), 129.9 (Ar), 125.7 (Ar), 67.9 (CMe3), 67.6 (CH2Ph), 33.1 (CMe3). Anal. Calcd. C, 57.15; H, 5.76; N, 2.67. Found C, 57.46; H, 5.97; N, 2.65.

Np3Ta=NCMe3 (2)

In the glovebox, a slurry of 426 mg (0.825 mmol, 1.0 equiv) of (py)2Cl3Ta=NCMe3 5 in Et2O (15 mL) was treated with 2.5 mL (2.5 mmol, 3.0 equiv) of Me3CCH2MgCl (1.0 M in Et2O),. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 8 h. Volatile materials were removed under vacuum to give an off-white solid. The solid was extracted with 15 mL of hexane and separated from the insoluble MgCl2 by filtration through a glass fiber filter pipet plug. Hexane was then removed from the filtrate under vacuum to give the off-white solid 2 (294 mg, 0.631 mmol, 76%). 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 1.62 (s, 9H, CMe3), 1.14 (s, 27H, CH2CMe3), 0.81 (s, 6H, CH2CMe3). 13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 108.2 (CH2CMe3), 68.3 (CMe3), 35.3 (CH2CMe3), 35.1 (CH2CMe3), 34.3 (CMe3). Anal. Calcd. C, 49.03; H, 9.10; N, 3.00. Found C, 49.27; H, 9.15; N, 3.01.

Preparation of Carbodiimide Double Insertion Product 5

In the glovebox, a vial was charged with 53.9 mg (0.103 mmol, 1 equiv) of Bn3Ta=NCMe3 (1) and 15 mL of benzene. The resulting solution was mixed with 25.8 mg (0.205 mmol, 2 equiv) of diisopropylcarbodiimide. The reaction mixture was then transferred to a teflon-sealed flask, which was taken out of the glovebox and placed in an oil bath heated to 75 °C for 24 h. The reaction flask was then taken back into the glovebox and the reaction mixture was transferred to a vial. The solvent was removed from the reaction mixture under vacuum to give a viscous yellow oil. The oil was mixed with 5 mL of pentane in order to assist in benzene removal. All remaining volatiles materials were then removed under vacuum to give the yellow foam 5 (45.8 mg, 57.4 %). 1H NMR (C6D6, 400 MHz) δ 7.54 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.32 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.19 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.07 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H, ArH), 6.94 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H, ArH), 6.94 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 3.91 (hept, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, CHMe2), 3.73 (m, 3H, CHMe2), 3.43 (m, 4H, amidinate CH2Ph), 3.04 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H, TaCH2Ph), 2.39 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H, TaCH2Ph), 1.58 (s, 9H, CMe3), 1.37 (m, 6H, CHMe2), 1.30 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, CHMe2), 1.21 (m, 6H, CHMe2), 1.09 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, CHMe2), 0.94 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, CHMe2), 0.80 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, CHMe2). 13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 172.4 (-N-C=N), 171.3 (-N-C=N), 152.8 (q-Ar), 135.9 (q-Ar), 135.0 (q-Ar), 129.0 (Ar), 128.8 (Ar), 128.7 (Ar), 128.6 (Ar), 128.5 (Ar), 127.7 (Ar), 126.9 (Ar), 126.8 (Ar), 121.2, Ar), 67.5 (TaCH2Ph), 64.6 (CMe3), 49.4 (CHMe2), 48.9 (CHMe2), 48.6 (CHMe2), 47.3 (CHMe2), 34.9 (CMe3), 32.7 (amidinate-CH2Ph), 32.5 (amidinate-CH2Ph), 27.6 (CHMe2), 25.60 (CHMe2), 25.56 (CHMe2), 25.49 (CHMe2), 25.38 (CHMe2), 25.35 (CHMe2), 24.37 (CHMe2), 24.1 (CHMe2), 22.7 (CHMe2). All carbon resonances were assigned by 1H -13C HMQC correlation and DEPT 135o. Anal. Calcd. C, 60.22; H, 7.52; N, 9.00. Found C, 55.97; H, 7.10; N, 8.04. The elemental analysis for 5 did not agree within .4% of the calculated molecular formula. An image of the 1H NMR spectrum of 5 is provided in the supporting information.

Preparation of Isocyanide Double Insertion Product 6

In the glovebox, a vial was charged with 72.2 mg (0.137 mmol, 1 equiv) of Bn3Ta=NCMe3 (1) and 10 mL of benzene. The resulting solution was mixed with 36.1 mg (0.275 mmol, 2 equiv) of 2,6-dimethylphenylisocyanide. The reaction mixture was then transferred to a reaction vessel with a Kontes teflon stopper and placed in an oil bath heated to 75 °C for 24 h. The reaction vessel was then removed from the bath and taken inside the glovebox. The reaction mixture was transferred to a vial and the solvent was removed under vacuum to give a brown oil. The oil was dissolved in 5 mL of pentane to assist in benzene removal and all remaining volatile materials were removed under vacuum to give the brown oil 6 (107.2 mg, 99.0%). 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 7.06 (m, 6H, ArH), 6.98 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H, ArH), 6.90 (m, 6H, ArH), 6.78 (m, 4H, ArH), 6.62 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 3.76 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 2H, N=CCH2Ph), 3.59 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 2H, N=CCH2Ph), 2.91 (s, 2H, TaCH2Ph), 1.82 (s, 6H, 2,6-Me2C6H3), 1.43 (s, 6H, 2,6-Me2C6H3), 1.02 (s, 9H, CMe3). 13C{1H} NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 254.7 (C=N), 152.9 (q-Ar), 144.1 (q-Ar), 136.3 (q-Ar), 130.5 (q-Ar), 130.0 (Ar), 128.82 (Ar), 128.79 (Ar), 128.74 (q-Ar), 128.4 (Ar), 128.2 (Ar), 127.9 (q-Ar), 127.7 (Ar), 127.5 (Ar), 126.9 (Ar), 126.4 (Ar), 120.2 (Ar), all other aryl resonances were buried under the solvent resonance, 66.5 (CMe3), 46.9 (TaCH2Ph), 43.2 (N=CCH2Ph), 34.2 (CMe3), 19.6 (2,6-Me2C6H3), 18.6 (2,6-Me2C6H3). The carbon resonances were assigned using DEPT 135o and 1H-13C HMQC techniques. Anal. Calcd. C, 64.48; H, 6.34; N, 5.50. Found C, 64.63; H, 6.18; N, 5.15.

[Bn2Ta=NCMe3][BnB(C6F5)3] (7)

In the glovebox, a vial was charged with 164 mg (0.314 mmol, 1 equiv) of Bn3Ta=NCMe3 (1) and 161 mg (0.314 mmol, 1 equiv) of B(C6F5)3. The vial was then charged with 10 mL of benzene and a stir bar. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 5 h. A yellow solid precipitated from solution during this time. The precipitate was separated from the solution by vacuum filtration through a glass frit. The filtrate was concentrated to 5 mL in vacuo and layered with 3 mL of hexane. After 2 h additional yellow solid had precipitated out of solution. This solid was also separated from the solution by vacuum filtration with a glass frit. The yellow solids were combined and the final traces of solvent were removed under vacuum to give the yellow solid 7 (240 mg, 73.8%). 1H NMR (C6D5Cl, 500 MHz) δ 7.19 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, p-ArH), 7.03 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H, mArH), 6.83 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, o-η6-ArH), 6.63 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H, o-ArH), 6.31 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, m-η6-ArH), 6.01 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, p-η6-ArH), 3.35 (bs, 2H, PhCH2B(C6F5)3), 1.78 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H, TaCH2Ph), 1.41 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H, TaCH2Ph), 1.08 (s, 9H, CMe3). 13C{1H} NMR (C6D5Cl, 100 MHz) δ 157.1 (q-Ar), 148.3 (d, J = 250 Hz, ArF), 137.0 (d, J = 241 Hz, ArF), 132.8 (q-Ar), 132.1 (Ar), 129.7 (Ar), 128.5 (Ar), 126.3 (Ar), 123.4 (Ar), 116.6 (p-η6-Ar), all other aryl carbon resonances are buried underneath the solvent resonances, 68.5 (CMe3), 48.3 (CH2Ph), 36.9 (BCH2Ph), 31.6 (CMe3). All carbon resonances were assigned by 1H -13C HMQC correlation and DEPT 135°. 11B NMR (C6D5Cl, 164.7 MHz) δ −12.63. 19F NMR (C6D5Cl, 376.5 MHz) δ −130.1, −159.8, −163.9. Anal. Calcd. C, 49.79; H, 2.92; N, 1.35. Found C, 49.72; H, 2.92; N, 1.40.

[(py)3Bn2Ta=NCMe3][BnB(C6F5)3] (8)

In the glovebox, a vial was charged with 102 mg (98.0 mmol, 1 equiv) of [Bn2Ta=NCMe3][BnB(C6F5)3] (7) and 10 mL of fluorobenzene. The resulting solution was mixed with 23.8 μL (0.294 mmol, 3 equiv) of pyridine. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3 h before the solvent was removed under vacuum to give the light orange solid 8 (95.2 mg, 76.2 %). 1H NMR (C6D5Cl, 400 MHz) δ 8.09 (bs, 6H, m-pyH), 7.38 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H, p-pyH), 7.12 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 4H, m-ArH), 6.96 (m, 6H, o-pyH), 6.89 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, p-ArH), 6.55 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H, o-ArH), 3.29 (bs, 2H, BCH2Ph), 2.40 (bs, 4H, TaCH2Ph), 1.13 (s, 9H, CMe3). 13C{1H} NMR (C6D5Cl, 100 MHz) δ 150.0 (py), 148.9 (q-Ar), 148.7 (d, J = 260 Hz, ArF), 140.1 (py), 137.7 (d, J = 242 Hz, ArF), 136.6 (d, J = 240 Hz, ArF), 128.5 (Ar), 127.1 (Ar), 124.7 (Ar), 124.1 (Ar), 122.8 (py), 78.4 (TaCH2Ph), 67.0 (CMe3), 31.5 (CMe3). All carbon resonances were assigned by 1H -13C HMQC correlation and DEPT 135°. The BCH2Ph carbon resonance was too broad to be observed. 11B NMR (C6D5Cl, 164.7 MHz) δ −12.81. 19F NMR (C6D5Cl, 376.5 MHz) δ −130.1, −163.5, −166.3. Anal. Calcd. C, 54.65; H, 3.56; N, 4.40. Found C, 54.48; H, 3.36; N, 4.21.

[Bn2Ta=NCMe3][B(C6F5)4]-C6H6 (9)

In the glovebox a vial was charged with 55.6 mg (0.106 mmol, 1 equiv) of 1 and 10 mL of fluorobenzene. The resulting solution was mixed with 97.6 mg (0.106 mmol, 1 equiv) of [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4]. The reaction mixture was shaken vigorously and then the solvent was removed under vacuum to give a brown oil. The oil was mixed with 10 mL of benzene and shaken. The slurry was then allowed to settle. The benzene supernatant was decanted away from the brown oil via pipet. This procedure for washing the oil with benzene was repeated three times. The oil was then mixed with 5 mL of hexane to assist in benzene removal. All volatile materials were removed from the sample under vacuum to give the dark brown glass 9 (42.6 mg, 36.2%). The low yield is caused by the benzene washings needed to remove tetraphenylethane. This compound is insoluble in chlorobenzene or benzene and reacts with all other common NMR solvents. Anal. Calcd. C, 48.39; H, 2.45; N, 1.18. Found C, 48.05; H, 2.60; N, 1.16.

[Bn2(THF)2Ta=NCMe3][B(C6F5)4] (10)

In the glovebox, a vial was charged with 69.9 mg (0.133 mmol, 1 equiv) of 1 and 10 mL of fluorobenzene. The resulting solution was mixed with 123 mg (0.133 mmol, 1 equiv) of [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] and 21.6 μL (0.266 mmol, 2 equiv) of THF. The reaction mixture was shaken briefly before the solvent was removed under vacuum to give a red/brown oil. The oil was washed with 3 × 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of benzene:hexane to remove the 1,1,1,2-tetraphenylethane side product. The oil was then mixed with 10 mL of pentane. All volatile materials were then removed under vacuum to give the red/orange foam 10 (88.0 mg, 52.6%). The yield of this reaction is low due to a small amount of solubility of the product in benzene. 1H NMR (C6D5Cl, 500 MHz, 25 °C) δ 7.07 (t, J =7.5 Hz, 4H, m-ArH), 6.98 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, p-ArH), 6.75 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H, o-ArH), 3.42 (bs, 8H, THF), 2.34 (bs, 4H, TaCH2Ph), 1.53 (bs, 8H, THF), 1.19 (s, 9H, CMe3). 1H NMR (C6D5Cl, 500 MHz, −31 °C) δ 7.07 (t, J =7.5 Hz, 4H, m-ArH), 6.98 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, p-ArH), 6.75 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H, o-ArH), 3.26 (bs, 8H, THF), 2.60 (bs, 2H, TaCH2Ph), 1.84 (bs, 2H, TaCH2Ph), 1.39 (bs, 8H, THF), 1.19 (s, 9H, CMe3). 13C{1H} NMR (C6D5Cl, 125 MHz) δ 148.7 (d, J = 236 Hz, ArF), 137.6 (t, J = 236 Hz, ArF), all other aryl carbon resonances overlap with the solvent resonances, 131.3 (Ar), 129.2 (Ar), 127.0 (Ar), 75.1 (bs, Ta-CH2Ph), 73.7 (THF), 69.6 (CMe3), 32.2 (CMe3), 25.3 (THF). 11B NMR (C6D5Cl, 164.7 MHz) δ −16.6. 19F NMR (C6D5Cl, 376.5MHz) δ −131.2, −162.1, −166.1. Anal. Calcd. C, 47.15; H, 3.09; N, 1.10. Found C, 46.76; H, 3.11; N, 1.21.

Preparation of Diphenylacetylene Insertion Product 11

In the glovebox, a vial was charged with 92.4 mg (0.176 mmol, 1 equiv) of 1 and 10 mL of fluorobenzene. The resulting solution was mixed with 162.2 mg (0.176 mmol, 1 equiv) of [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] and 31.3 mg (0.166 mmol, 1 equiv) of diphenylacetylene. The reaction was shaken briefly and then the solvent was then removed under vacuum to give a red/brown oil. The oil was washed with 3 × 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of benzene:hexane to remove the 1,1,1,2-tetraphenylethane side product. The oil was then mixed with 10 mL of pentane and all remaining volatile materials were removed under vacuum to give the red/orange foam 11 (125.7 mg, 55.4%). The yield of this reaction is low due to the slight solubility of the product in benzene. 1H NMR (C6D5Cl, 500 MHz) δ 7.31 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.16 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.09 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H, ArH), 6.91 (m, 5H, ArH), 6.79 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.74 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.64 (m, 4H, ArH), 6.13 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, η2-Ar), 3.72 (d, J = 17 Hz, 1H, alkenyl-CH2Ph), 3.59 (d, J = 17 Hz, 1H, alkenyl-CH2Ph), 2.95 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H, TaCH2Ph), 2.27 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H, TaCH2Ph), 0.98 (s, 9H, CMe3). 13C{1H} NMR (C6D5Cl, 500 MHz) δ 208.2 (alkenyl-CPh), 173.2 (alkenyl-CPh), 152.1 (q-Ar), 148.7 (d, J = 236 Hz, ArF), 143.9 (q-Ar), 140.2 (q-Ar), 138.5 (d, J = 244 Hz, ArF), 136.6 (d, J = 238 Hz, ArF), all other carbon aryl resonances overlap with solvent resonances, 134.8 (η2-q-Ar), 134.4 (Ar), 131.5 (Ar), 129.8 (Ar), 129.7 (Ar), 128.9 (Ar), 128.2 (Ar), 128.0 (Ar), 127.8 (Ar), 126.5 (Ar), 126.3 (Ar), 121.6 (Ar), 120.5 (Ar), 73.2 (TaCH2Ph), 69.3 (CMe3), 46.0 (alkenyl-CH2Ph), 31.9 (CMe3). 11B NMR (C6D5Cl, 164.5 MHz) δ −16.56. 19F NMR (C6D5Cl, 376.5 MHz) δ −131.6, −161.6, −165.6. Anal. Calcd. C, 52.08; H, 2.58; N, 1.08. Found C, 51.93; H, 2.78; N, 1.25.

A solution of ~25 mg of compound 11 in 1.5 mL diethyl ether was transferred to a vial and taken out of the glovebox. The solution was mixed with 1 mL of 1M HCl(aq). The mixture was shaken and allowed to settle. The ether layer was then decanted via pipet and filtered through 1 mL of silica in a pipet filter plug. The filtrate was then analyzed by GC-MS. Retention time: 22.2 min. M+ = 270 m/z.

Preparation of Phenylacetylene Insertion Product 13

In the glovebox, a vial was charged with 79.1 mg (0.151 mmol, 1 equiv) of 1 and 10 mL of fluorobenzene. The resulting solution was mixed with 139 mg (0.151 mmol, 1 equiv) of [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] and 15.4 mg (0.151 mmol, 1 equiv) of phenylacetylene. The reaction mixture was shaken briefly before the solvent was removed under vacuum to give a red/brown oil. The oil was washed with 3 × 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of benzene:hexane to remove the 1,1,1,2-tetraphenylethane side product. The oil was then mixed with 10 mL of pentane and all remaining volatile materials were removed under vacuum to give the dark red foam 13 (88.5 mg, 48.4%). The yield of this reaction is low due to the slight solubility of the product in benzene. 1H NMR (C6D5Cl, 400 MHz) δ 7.54 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.19 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.07 (m, 3H, ArH), 6.90 (m, 4H, ArH), 6.29 (bs, 2H, η2-ArH), 5.39 (s, 1H, vinyl-CH), 3.65 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, alkenyl-CH2Ph), 3.41 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, alkenyl-CH2Ph), 2.66 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, TaCH2Ph), 2.06 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, TaCH2Ph), 0.92 (CMe3). 13C{1H} NMR (C6D5Cl, 100 MHz) δ 177.1 (vinyl-CH), 169.1 (alkenyl-CPh), 153.5 (q-Ar), 148.7 (d, J = 238 Hz, ArF), 140.9 (q-Ar), 138.6 (d, J = 244 Hz, ArF), 137.1 (d, J = 256 Hz, ArF), 134.2 (η2-q-Ar), 131.3 (Ar), 130.8 (Ar), 128.6 (Ar), 128.6 (Ar), 124.7 (Ar), 121.6 (Ar), 119.5 (Ar), 118.5 (Ar), 114.5 (q-Ar), other aryl carbon resonances overlap with solvent resonances, 68.7 (CMe3), 45.1 (TaCH2Ph), 42.9 (alkenyl-CH2Ph), 31.3 (CMe3). 11B NMR (C6D5Cl, 164.7 MHz) δ −16.7. 19F NMR (C6D5Cl, 376.5MHz) δ −131.7, 161.8, 165.8. Anal. Calcd. C, 49.41; H, 2.40; N, 1.15. Found C, 49.13; H, 2.68; N, 1.21.

Preparation of Norbornene Insertion Product 14

In the glovebox, a vial was charged with 87.4 mg (0.166 mmol, 1 equiv) of 1 and 10 mL of fluorobenzene. The resulting solution was mixed with 153 mg (0.166 mmol, 1 equiv) of [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] and 13.9 mg (0.166 mmol, 1 equiv) of norbornene. The solvent was then removed under vacuum to give a red/brown oil. The oil was washed with 3 × 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of benzene:hexane to remove the 1,1,1,2-tetraphenylethane side product. The oil was then mixed with 10 mL of pentane and all remaining volatile materials were then removed under vacuum to give the light orange foam 14 (96.9 mg, 48.2%). The yield of this reaction is low due to the slight solubility of the product in benzene. 1H NMR (C6D5Cl, 400 MHz) δ 7.25 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.95 (m, 4H, ArH), 6.77 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.58 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.51 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H ArH), 6.25 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, ArH), 2.61 (dd, J = 9.2 Hz, 5.2 Hz, 1H, CHCH2Ph), 2.32 (m, 3H, TaCH2Ph, CHCH2Ph), 2.21 (bs, 1H, bridgehead-H), 1.88 (dd, J = 9.2 Hz, 5.2 Hz, 1H, CHCH2Ph), 1.54 (m, 1H, CH2), 1.35 (bd, 10 Hz, methylene bridge-CH2), 1.20 (m, 1H, CH2), 1.01 (s, 9H, CMe3), 0.85 (bd, 10Hz, methylene bridge-CH2), 0.74 (m, 1H, CH2), 0.24 (m, 1H, CH2), −1.84 (d, 8.8 Hz, 1H, Ta-CH). 13C NMR (C6D5Cl, 125 MHz) δ 151.0 (q-Ar), 148.4 (d, J = 236 Hz, ArF), 146.5 (q-Ar), 137.4 (t, J = 238 Hz, ArF), 133.5 (Ar), 132.4 (Ar), 132.1 (Ar), 129.3 (Ar), 128.3 (Ar), 127.3 (Ar), 124.4 (Ar), 122.5 (Ar), 113.7 (Ar), all other carbon aryl resonances overlap with solvent resonances, 69.9 (TaCH), 69.4 (CMe3), 60.8 (CHCH2Ph), 53.6 (CH bridgehead), 44.2 (CH bridgehead), 44.0 (TaCH2Ph), 43.1 (CHCH2Ph), 39.7 (CH2), 35.7 (CH2), 31.2 (CMe3), 27.2 (CH2). 11B NMR (C6D5Cl, 164.5) δ −16.57. 19F NMR (C6D5Cl, 376.5MHz) δ −131.7, 161.8, 165.8. Anal. Calcd. C, 48.74; H, 2.75; N, 1.16. Found C, 48.70; H, 2.93; N, 1.20.

A solution of ~25 mg of compound 14 in 1.5 mL diethyl ether was transferred to a vial and taken out of the glovebox. The solution was mixed with 1 mL of 1M HCl(aq). The mixture was shaken and allowed to settle. The ether layer was then decanted via pipet and filtered through 1 mL of silica in a pipet filter plug. The filtrate was then analyzed by GC-MS. Retention time: 24.9 min. M+ = 243 m/z.

Preparation of Ciscyclooctene Insertion Product 16

In the glovebox, a vial was charged with 79.6 mg (0.151 mmol, 1 equiv) of 1 and 10 mL of fluorobenzene. The resulting solution was mixed with 140 mg (0.151 mmol, 1 equiv) of [Ph3C][B(C6F5)4] and 16.7 mg (0.151 mmol, 1 equiv) of ciscyclooctene. The solvent was then removed under vacuum to give a red/brown oil. The oil was washed with 3 × 10 mL of a 50:50 mixture of benzene:hexane to remove the 1,1,1,2-tetraphenylethane side product. The oil was then mixed with 10 mL of pentane and all of the remaining volatile materials were removed to give the orange foam 16 (102 mg, 54.9%). The yield of this reaction is low due to the slight solubility of the product in benzene. 1H NMR (C6D5Cl, 400 MHz) δ 7.53 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.30 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.14 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.95 (m, 2H, ArH), 6.77 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.60 (m, 2H, ArH), 6.40 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, η2-ArH), 2.58 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ta-CH2Ph), 2.27-2.15 (m, 3H, CH and CH2Ph), 2.06 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ta-CH2Ph), 1.98 (m, 1H, CH2), 1.49 (m, 1H, CH2), 1.32-1.04 (m, 12H, CH2), 0.97 (s, 9H, CMe3), −1.37 (m, 1H, Ta-CH). 13C NMR (C6D5Cl, 125 MHz) δ 159.6 (q-Ar), 149.2 (d, J = 247 Hz, ArF), 137.8 (t, J = 243 Hz, ArF), 134.9 (Ar), 134.6 (Ar), 133.6 (Ar), 130.6 (Ar), 128.3 (Ar), 123.5 (Ar), 121.8 (Ar), 118.1 (Ar), 115.3 (Ar), all other aryl carbon resonances overlap with the solvent resonances, 68.9 (CMe3), 68.2 (CHPh), 67.0 (Ta-CH), 53.5 (TaCH2Ph), 46.3 (CHCH2Ph), 46.3 (CH2), 40.5 (CH2), 34.2 (CH2), 32.9 (CH2), 31.6 (CMe3), 29.1 (CH2), 27.9 (CH2), 24.7 (CH2), 24.2 (CH2), 22.7 (CH2). 11B NMR (C6D5Cl, 164.5 MHz) δ −16.56. 19F NMR (C6D5Cl, 376.5MHz) δ −131.7, 161.8, 165.8. Anal. Calcd. C, 48.74; H, 2.75; N, 1.16. Found C, 48.70; H, 2.93; N, 1.20.

A solution of ~25 mg of compound 16 in 1.5 mL diethyl ether was transferred to a vial and taken out of the glovebox. The solution was mixed with 1 mL of 1M HCl(aq). The mixture was shaken and allowed to settle. The ether layer was then decanted via pipet and filtered through 1 mL of silica in a pipet filter plug. The filtrate was then analyzed by GC-MS. Retention time: 17.9 min. M+ = 202.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details for the X-ray diffraction study of 1, the images of all 1H-13C HMQC and 1H-13C HMBC spectra for compounds 5, 6, 7, 11, 13, 14, and 16, and the image of the 1H-1H NOESY spectrum of 14 are available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

Joseph A. R. Schmidt preformed the crystallographic study of compound 1. The authors would like to acknowledge the University of California, Berkeley CHEXRAY facility and Dr. Allen Oliver for assistance with the data. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. GM-25459 to R.G.B.) and the National Science Foundation (Grant No. CHE-0072819 to J.A.).

References

- 1.Duncan AP, Bergman RG. Chem Rec. 2002;2:431–445. doi: 10.1002/tcr.10039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh PJ, Hollander FJ, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:8729–8731. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh PJ, Hollander FJ, Bergman RG. Organometallics. 1993;12:3705–3723. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoyt HM, Michael FE, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1018–1019. doi: 10.1021/ja0385944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummins CC, Baxter SM, Wolczanski PT. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:8731–8733. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum SA, Walsh PJ, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14276–14277. doi: 10.1021/ja037267t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michael FE, Duncan AP, Sweeney ZK, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7184–7185. doi: 10.1021/ja0348389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michael FE, Duncan AP, Sweeney ZK, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1752–1764. doi: 10.1021/ja045607k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeney ZK, Salsman JL, Andersen RA, Bergman RG. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2000;39:2339–2343. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000703)39:13<2339::aid-anie2339>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lalic G, Blum SA, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16790–16791. doi: 10.1021/ja056132f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh PJ, Baranger AM, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1708–1719. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baranger AM, Walsh PJ, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:2753–2763. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuckerman RL, Krska SW, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:751–761. doi: 10.1021/ja992869r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuckerman RL, Bergman RG. Organometallics. 2001;20:1792–807. doi: 10.1021/om010091o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krska SW, Zuckerman RL, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11828–11829. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolton PD, Mountford P. Adv Synth Catal. 2005;347:355–366. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:4592–4633. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wigley DE. Progress In Inorganic Chemistry. 42. Vol. 42. 1994. pp. 239–482. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pugh SM, Trosch DJM, Skinner MEG, Gade LH, Mountford P. Organometallics. 2001;20:3531–3542. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt S, Sundermeyer J. J Organomet Chem. 1994;472:127–138. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gust KR, Heeg MJ, Winter CH. Polyhedron. 2001;20:805–813. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundermeyer J, Runge D. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1994;33:1255–1257. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrmann WA, Baratta W, Herdtweck E. J Organomet Chem. 1997;541:445–460. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gavenonis J, Tilley TD. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8536–8537. doi: 10.1021/ja025684k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burckhardt U, Casty GL, Gavenonis J, Tilley TD. Organometallics. 2002;21:3108–3122. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomez M, Gomez-Sal P, Jimenez G, Martin A, Royo P, Sanchez-Nieves J. Organometallics. 1996;15:3579–3587. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez-Nieves J, Royo P, Pellinghelli MA, Tiripicchio A. Organometallics. 2000;19:3161–3169. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prashar S, Fajardo M, Garces A, Dorado I, Antinolo A, Otero A, Lopez-Solera I, Lopez-Mardomingo C. J Organomet Chem. 2004;689:1304–1314. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royo P, Sanchez-Nieves J. J Organomet Chem. 2000;597:61–68. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burland MC, Pontz TW, Meyer TY. Organometallics. 2002;21:1933–1941. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ong TG, Yap GPA, Richeson DS. Chem Commun. 2003:2612–2613. doi: 10.1039/b308710g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antonelli DM, Leins A, Stryker JM. Organometallics. 1997;16:2500–2502. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng SG, Roof GR, Chen EYX. Organometallics. 2002;21:832–839. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coles MP, Dalby CI, Gibson VC, Little IR, Marshall EL, da Costa MHR, Mastroianni S. J Organomet Chem. 1999;591:78–87. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Decker JM, Geib SJ, Meyer TY. Organometallics. 1999;18:4417–4420. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blake RE, Antonelli DM, Henling LM, Schaefer WP, Hardcastle KI, Bercaw JE. Organometallics. 1998;17:718–725. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Humphries MJ, Douthwaite RE, Green MLH. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 2000:2952–2959. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson LL, Arnold J, Bergman RG. Org Lett. 2004;6:2519–2522. doi: 10.1021/ol0492851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groysman S, Goldberg I, Kol M, Goldschmidt Z. Organometallics. 2003;22:3793–3795. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chamberlain LR, Rothwell IP, Folting K, Huffman JC. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1987:155–162. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mashima K, Yonekura H, Yamagata T, Tani K. Organometallics. 2003;22:3766–3772. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nugent WA, Harlow RL. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1978:579–580. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bailey NJ, Cooper JA, Gailus H, Green MLH, James JT, Leech MA. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1997:3579–3584. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schorm A, Sundermeyer J. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2001:2947–2955. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Green MLH. J Organomet Chem. 1995;500:127–148. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nugent WA, Mayer JM. Metal-Ligand Multiple Bonds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 1988. pp. 133–134. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaller CP, Wolczanski PT. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:131–144. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang YH, Kissounko DA, Fettinger JC, Sita LR. Organometallics. 2003;22:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Littke A, Sleiman N, Bensimon C, Richeson DS, Yap GPA, Brown SJ. Organometallics. 1998;17:446–451. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gambarotta S, Strologo S, Floriani C, Chiesivilla A, Guastini C. Inorg Chem. 1985;24:654–660. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rowley CN, DiLabio GA, Barry ST. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:1983–1991. doi: 10.1021/ic048501z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keaton RJ, Jayaratne KC, Henningsen DA, Koterwas LA, Sita LR. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6197–6198. doi: 10.1021/ja0057326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sita LR, Babcock JR. Organometallics. 1998;17:5228–5230. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muller E, Muller J, Olbrich F, Bruser W, Knapp W, Abeln D, Edelmann FT. Eur J Inorg Chem. 1998:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stewart PJ, Blake AJ, Mountford P. J Organomet Chem. 1998;564:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guiducci AE, Cowley AR, Skinner MEG, Mountford P. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 2001:1392–1394. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bolton PD, Clot E, Cowley AR, Mountford P. Chem Commun. 2005:3313–3315. doi: 10.1039/b504567c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chamberlain LR, Durfee LD, Fanwick PE, Kobriger L, Latesky SL, McMullen AK, Rothwell IP, Folting K, Huffman JC, Streib WE, Wang R. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:390–402. doi: 10.1021/ja00236a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McMullen AK, Rothwell IP, Huffman JC. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:1072–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chamberlain LR, Rothwell IP, Huffman JC. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1986:1203–1205. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ong TG, Yap GPA, Richeson DS. Organometallics. 2003;22:387–89. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duncan AP, Mullins SM, Arnold J, Bergman RG. Organometallics. 2001;20:1808–1819. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pellecchia C, Immirzi A, Grassi A, Zambelli A. Organometallics. 1993;12:4473–4478. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang XM, Stern CL, Marks TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:3623–3625. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang XM, Stern CL, Marks TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:10015–10031. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen EYX, Marks TJ. Chem Rev. 2000;100:1391–1434. doi: 10.1021/cr980462j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shafir A, Arnold J. Organometallics. 2003;22:567–575. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Horton AD, de With J. Organometallics. 1997;16:5424–5436. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pellecchia C, Grassi A, Immirzi A. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1160–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gauvin RM, Osborn JA, Kress J. Organometallics. 2000;19:2944–2946. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thorn MG, Etheridge ZC, Fanwick PE, Rothwell IP. Organometallics. 1998;17:3636–3638. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Horton AD, de With J, van der Linden AJ, van de Weg H. Organometallics. 1996;15:2672–2674. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chien JCW, Tsai WM, Rausch MD. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:8570–8571. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Collman JP, Hegedus LS, Norton JR, Finke RG. Principles and Applications of Organotransition Metal Chemistry. University Science Books; Mill Valley: 1987. p. 390. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pellecchia C, Grassi A, Zambelli A. Organometallics. 1994;13:298–302. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pellecchia C, Immirzi A, Zambelli A. J Organomet Chem. 1994;479:C9–C11. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pellecchia C, Immirzi A, Pappalardo D, Peluso A. Organometallics. 1994;13:3773–3775. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jordan RF, Lapointe RE, Baenziger N, Hinch GD. Organometallics. 1990;9:1539–1545. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Collman JP, Hegedus LS, Norton JR, Finke RG. Principles and Applications of Organotransition Metal Chemistry. University Science Books; Mill Valley: 1987. p. 580. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Silverstein RM, Bassler GC, Morrill TC. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. 5. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1991. p. 197. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anderson LL, Arnold J, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14542–14543. doi: 10.1021/ja053700i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Anderson LL. PhD Thesis. University of California; Berkeley, Berkeley, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Muller TE, Beller M. Chem Rev. 1998;98:675–703. doi: 10.1021/cr960433d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pohlki F, Doye S. Chem Soc Rev. 2003;32:104–114. doi: 10.1039/b200386b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bytschkov I, Doye S. Eur J Org Chem. 2003:935–946. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Johnson JS, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2923–2924. doi: 10.1021/ja005685h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haak E, Bytschkov I, Doye S. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1999;38:3389–3391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Heutling A, Doye S. J Org Chem. 2002;67:1961–1964. doi: 10.1021/jo016311p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shi YH, Ciszewski JT, Odom AL. Organometallics. 2001;20:3967–3969. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cao CS, Ciszewski JT, Odom AL. Organometallics. 2001;20:5011–5013. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Khedkar V, Tillack A, Beller M. Org Lett. 2003;5:4767–4770. doi: 10.1021/ol035653+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hong S, Marks TJ. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:673–686. doi: 10.1021/ar040051r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Giardello MA, Conticello VP, Brard L, Gagne MR, Marks TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:10241–10254. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim YK, Livinghouse T, Horino Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9560–9561. doi: 10.1021/ja021445l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lauterwasser F, Hayes PG, Brase S, Piers WE, Schafer LL. Organometallics. 2004;23:2234–2237. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ryu JS, Li GY, Marks TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12584–12605. doi: 10.1021/ja035867m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pohlki F, Doye S. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:2305–2308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Groysman S, Goldberg I, Kol M, Genizi E, Goldschmidt Z. Organometallics. 2004;23:1880–1890. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Giesbrecht GR, Shafir A, Arnold J. Chem Commun. 2000:2135–2136. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shafir A, Power MP, Whitener GD, Arnold J. Organometallics. 2001;20:1365–1369. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Blake AJ, Collier PE, Dunn SC, Li WS, Mountford P, Shishkin OV. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1997:1549–1558. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Alaimo PJ, Peters DW, Arnold J, Bergman RG. J Chem Ed. 2001;78:64–64. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Massey AG, Park AJ. J Organomet Chem. 1964;2:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lambert JB, Zhang SZ, Ciro SM. Organometallics. 1994;13:2430–2443. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details for the X-ray diffraction study of 1, the images of all 1H-13C HMQC and 1H-13C HMBC spectra for compounds 5, 6, 7, 11, 13, 14, and 16, and the image of the 1H-1H NOESY spectrum of 14 are available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.