Abstract

Several lines of evidence indicate that the elaborated calcium signals and the occurrence of calcium waves in astrocytes provide these cells with a specific form of excitability. The identification of the cellular and molecular steps involved in the triggering and transmission of Ca2+ waves between astrocytes resulted in the identification of two pathways mediating this form of intercellular communication. One of them involves the direct communication between the cytosols of two adjoining cells through gap junction channels, while the other depends upon the release of “gliotransmitters” that activates membrane receptors on neighboring cells. In this review we summarize evidence in favor of these two mechanisms of Ca2+ wave transmission and we discuss that they may not be mutually exclusive, but are likely to work in conjunction to coordinate the activity of a group of cells. To address a key question regarding the functional consequences following the passage of a Ca2+ wave, we list, in this review, some of the potential intracellular targets of these Ca2+ transients in astrocytes, and discuss the functional consequences of the activation of these targets for the interactions that astrocytes maintain with themselves and with other cellular partners, including those at the glial/vasculature interface and at perisynaptic sites where astrocytic processes tightly interact with neurons.

Keywords: glial cells, gliotransmitters, ATP, gap junctions, connexins

CALCIUM SIGNALS AS A SPECIFIC MODE OF EXCITABILITY AND TRANSMISSION IN ASTROCYTES: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The findings that astrocytes express a variety of ion channels and membrane receptors, which enable them to respond on a millisecond time scale to neuronal activity with changes in membrane potential and/or increases in intracellular Ca2+ levels (Barres et al., 1990; MacVicar and Tse, 1988; Marrero et al., 1989; McCarthy and Salm, 1991; Salm and MacCarthy, 1990; Usowic et al., 1989) was the first step in the glia field leading to the hypothesis that these cells could play a role in CNS information processing. It was based on these early reports that Cornell-Bell et al. (1990) and Charles et al. (1991) first reported that astrocytes were not only able to respond to external stimulation with increases in intracellular calcium elevations but, most importantly, they were be able to transmit these calcium signals to adjacent non-stimulated astrocytes, as intercellular Ca2+ waves (ICWs). The presence of such phenomenon of propagating waves of calcium lead to the proposition that “networks of astrocytes constitute an extraneuronal pathway for rapid long-distance signal transmission within the CNS.” Moreover, these authors (Cornell-Bell et al., 1990) proposed that “if Ca2+ activity in the network of astrocytes constituted another form of intercellular communication, such signaling should have a physiological relevance influencing neuronal activity, and thus being bi-directional.” Work by several independent groups showed that indeed there is a reciprocal communication between neurons and astrocytes. Hippocampal neuronal activity was shown to trigger calcium waves in astrocyte networks (Dani et al., 1992) and astrocyte calcium waves were shown to modulate neuronal activity (Dani et al., 1992; Kang et al., 1998; Nedergaard, 1994; Parpura et al., 1994; Parri et al., 2001). The mode by which astrocyte calcium signals affect synaptic transmission was then shown to be dependent on regulated exocytosis of stored glutamate, ATP, and D-serine (Bezzi et al., 2004; Coco et al., 2003; Mothet et al., 2005; Parpura et al., 1994; Pascual et al., 2005). Consequently, the pre- and post-synaptic components of neuronal transmission gained a new partner, the perisynaptic glia, forming together what was initially termed the “tripartite-synapse” (Araque et al., 1998a,b). Because these studies indicated that the electrically silent astrocytes were active participants of CNS information processing, it became plausible to consider that astrocytes are nevertheless “excitable” cells, with Ca2+ fluctuations being the signal by which they respond, integrate, and convey information.

Although with the limitation of the studies performed in culture, pioneering experiments (Cornell-Bell et al., 1990) generated insightful ideas that, followed by experimental evidence, brought a new perspective to the role of glial cells in CNS function. Of note is their report on the spatial and temporal pattern changes that occur after 100 μM glutamate application. Following the initial Ca2+ elevation induced by receptor activation, oscillatory Ca2+ fluctuations preceded the intercellular spread of Ca2+. This oscillatory behavior persisted for long periods of time (5–30 min) with variable frequencies (10–110 mHz). A direct correlation between glutamate concentration and frequency of oscillations was observed: at low concentrations (below 1 μM) intracellular Ca2+ transients were asynchronous and localized, whereas at higher concentrations (10–100 μM) intercellular CA2+ waves propagated over long distances. This indicated that small fluctuations in intracellular Ca2+ could be integrated to generate a global intracellular response, which could be transmitted throughout the astrocytic network. Recent development of in vivo imaging, using two-photon microscopy, has provided evidence for coordinated astrocyte Ca2+ activity in the neocortex of rats (Hirase et al., 2004).

Although many of the questions that were raised when Ca2+ waves were first described have been answered, many are still debated and others have been generated. This review is not intended to revisit the concept and evidence that culminated in this new line of investigation, for which several recent reviews are available (Charles and Giaume, 2002; Nedergaard et al., 2003; Scemes, 2000). Instead, this review will focus on the characteristics and consequences of intercellular Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes and their relevance to CNS function. Because “gliotransmitter” released from astrocytes (the mechanisms by which this release is accomplished are discussed in the other reviews), besides affecting synaptic transmission and brain microcirculation, is also likely to serve as an autocrine signal, we will consider in this review some important aspects of this feedback mechanism for the transmission of Ca2+ waves between astrocytes.

CA2+ WAVES IN VITRO AND IN VIVO: WHEN AND WHERE DO THEY OCCUR?

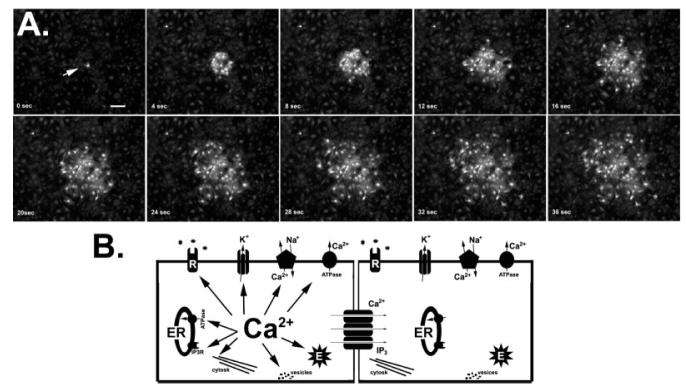

A calcium wave is defined as a localized increase in cytosolic Ca2+ that is followed by a succession of similar events in a wave-like fashion. These Ca2+ waves can be restricted to one cell (intracellular) or transmitted to neighboring cells (intercellular) (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Intercellular Ca2+ waves and their intracellular targets. (A) The transmission of intercellular Ca2+ signals between astrocytes is illustrated in the sequential images obtained from Fluo-3-AM loaded spinal cord astrocytes. Mechanical stimulation (arrow) of a single astrocyte in culture induces intracellular Ca2+ elevation (displayed as an increase in fluorescence intensity) in the stimulated cells, which is then followed by Ca2+ increases in neighboring astrocytes. Images were acquired with an Orca-ER CCD camara attached to Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope equipped with a ×10 objective, using Metafluor software. Bar: 50 μm. (B) The diagram illustrates the major intracellular targets of cytosolic Ca2+ fluctuations in astrocytes. Elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels is shown to affect (arrows) several plasma membrane proteins (symbols refer from left to right to metabotropic receptors, K+ (Ca2+) channels, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, and Ca2+-ATPase), as well as intracellular ones. The inositol-trisphosphate receptors (IP3R) are located at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where Ca2+ exert a cooperative action. Rises in [Ca2+]i also target several cytoskeleton elements (cytosk), enzymes (E), and vesicles involved on the release of “gliotransmitters”. Finally, Ca2+ and the Ca2+ liberating second messenger IP3 permeate gap junction channels and then act on similar intracellular targets in neighboring coupled cells.

The basic steps that lead to intracellular Ca2+ waves in astrocytes usually involve the activation of G-protein-coupled receptors, activation of phospholipase C, and the production of IP3, which following IP3R activation leads to Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Golovina and Blaustein, 2000; Scemes, 2000; Sheppard et al., 1997). These intracellular Ca2+ signals are spatially and temporally complex events involving the recruitment of elementary Ca2+ release sites (Ca2+ puffs: Parker and Yao, 1994), which then propagate throughout the cell by an amplification mechanism. This amplification involves four components, two of which depend on positive and two on negative feedback mechanisms provided by released Ca2+. These feedback mechanisms are: (a) the activation of nearby IP3Rs due to the co-agonistic action of Ca2+ on these receptors (Bezprovanny and Ehrlich, 1995; Finch et al., 1991; Yao et al., 1995), (b) the additional generation of IP3 through the Ca2+ -dependent activation of PLC (Berridge, 1993; Venance et al., 1997), (c) the buffering power of mitochondria, attenuating the excess Ca2+ levels at IP3R microdomains that otherwise would reduce the sensitivity of these receptors to IP3 (Boitier et al., 1999; Simpson et al., 1998), and (d) the presence of endogenous low affinity Ca2+ buffers (calcium binding proteins) that limit the diffusion of Ca2+ ions within single astrocytes (Wang et al., 1997).

Once triggered, intracellular Ca2+ waves can be transmitted to neighboring cells as ICWs. Regardless of the mechanism by which these waves may travel (see details that follow), the mechanism that triggers Ca2+ transients in adjacent astrocytes relies on IP3 production and subsequent release of Ca2+ from the ER, as summarized above for intracellular Ca2+ waves. Therefore, the extent to which these intercellular Ca2+ waves can travel are governed by the effective diffusion properties of the Ca2+ mobilizing signaling molecules within and between cells.

ICW spread between astrocytes derived from cell culture, brain slice, and whole retina preparations has been observed following pharmacological, electrical, and mechanical stimulation (for review see Boitier et al., 1999; Charles, 1998; Charles and Giaume, 2002; Giaume and Venance, 1998; Newman, 2004; Scemes, 2000; Simpson et al., 1998). Although there are some differences regarding the distance and shape of ICWs generated by each type of stimulation, once they are initiated, the velocities by which they travel between astrocytes are fairly similar, independent of the mode of stimulation and type of preparation. For instance, pharmacological, mechanical, and electrical stimulation of rat retina induced ICWs that traveled at a mean speed of 23 μm/sec (Newman and Zahs, 1997); pharmacologically and mechanically-induced intercellular Ca2+ waves between cultured astrocytes travel at a mean velocity of 18 μm/sec (for reviews see Giaume and Venance, 1998; Scemes, 2000), and in the electrically stimulated brain slice preparations, the mean Ca2+ wave velocity is 15 μm/sec (Dani et al., 1992; Hass et al., 2005; Schipke et al., 2002). In contrast to the velocity of Ca2+ wave spread, the extent to which ICW travels is highly variable, even when comparing a single type of stimulation among different types of preparations. For example, differences in the number of cells participating in ICW transmission following mechanical stimulation were observed among cultures of astrocytes prepared from distinct brain regions; ICWs spread to twice as many cortical and hippocampal astrocytes as between astrocytes from the hypothalamus and brain stem (Blomstrand et al., 1999). Similarly, mechanically induced Ca2+ waves between cultured telencephalic astrocytes spread radially to an area of 450 μm2 comprising about 400 cells while waves traveling between cultured diencephalic astrocytes spread unevenly to an area of 130 μm2 recruiting about 100 cells (Peters et al., 2005).

Regardless of the notorious differences between culture and in situ conditions (e.g., morphology of astrocytes, size of the extracellular space), some generalizations can be made with respect to the properties of ICWs. Based on the studies reported above, it is likely that some of the characteristics of Ca2+ waves are governed by the intrinsic properties of the astrocytic Ca2+ signaling toolkit (Berridge et al., 2000a,b)—G-coupled membrane receptors, Ca2+ mobilizing second messengers, ER, Ca2+ buffering molecules and intracellular organelles—that once fully activated to produce an intracellular Ca2+ wave can be transmitted to an adjacent astrocyte, with a velocity that is independent of the type of preparation used, i.e., independent of the morphological differences. Moreover, even considering that the extent of ICW spread is vastly larger in culture conditions than in brain slices, most likely due to the restricted extracellular space in the latter, the studies performed in cultured astrocytes from different brain regions described above suggest that the distance of transmission of ICW is likely related to heterogeneous populations of astrocytes. Differences in type and number of membrane receptors and gap junction channels, main components of astrocyte intercellular Ca2+ signaling (see following), are likely responsible for defining boundaries of communicating networks.

Although these in vitro studies indicate that astrocytes can to some variable extent and degree transmit ICWs, the magnitude of the stimuli necessary to trigger this form of Ca2+ signaling is usually considerably higher than would be expected to occur under physiological situation. Thus, the existence and relevance of this form of astrocytic communication for CNS function may be questioned at least in normal, physiological situations. In whole-mount retinas, flickering light stimulation induces Ca2+ transients, but not intercellular Ca2+ waves in Mueller cells of the inner plexiform layer; however, in the presence of adenosine, light flashes enhance Mueller cell responses and induce ICW spread between these glial cells (Newman, 2005). This study suggested that ICW propagation between Mueller cells may occur under non-physiological conditions, such as under hypoxic conditions where adenosine levels are significantly increased (Ribelayga and Mangel, 2005). However, it should be noted that adenosine levels in retinas also fluctuate in a circadian and light-dependent manner (Ribelayga and Mangel, 2005) and therefore, ICW spread between Mueller cells may occur under physiological conditions. Similarly, using two-photon laser scanning microscopy to monitor in vivo Ca2+ dynamics in astrocytes from superficial cortical layer of rat brains, Hirase et al. (2004) recorded low frequency Ca2+ transients in single astrocytes that could be spread, although within a very limited range, between few neighboring cells with a low but non-zero level of coordination; the degree of such coordinated Ca2+ activity between neighboring astrocytes was found to be positively correlated with neuronal discharge, as observed following blockade of neuronal GABAA receptors with bicuculline. Thus, this study provided evidence that enhanced but not seizure-related neuronal activity influences intercellular glia communication in the intact brain.

In view of what is known so far about ICWs in astrocytes, it is likely that this form of Ca2+ signal transmission play important role under pathological but not under physiological conditions. With the exception of early CNS developmental stages, when spontaneous Ca2+ waves are frequently observed and implicated in the generation, differentiation, and migration of neural cells (Feller et al., 1996; Gu and Spitzer, 1995; Kumada and Komuro, 2004; Scemes et al., 2003; Weissman et al., 2004; Wong et al., 1995), spontaneous ICWs are rarely seen in the mature CNS, even following physiological stimulation.

PATHWAYS FOR INTERCELLULAR TRANSMISSION OF CA2+ SIGNALS IN ASTROCYTES

There are two possible pathways by which Ca2+ signals can be transmitted between cells; one involves the transfer of Ca2+ mobilizing second messengers directly from the cytosol of one cell to that of an adjacent one through gap junction intercellular channels and the other involves the “de novo” generation of such messengers in neighboring cells through the activation of membrane receptors due to extracellular diffusion of agonists. These two pathways are not mutually exclusive but are likely to work in conjunction to provide coordinated activity within groups of cells.

Gap junction mediated transmission of ICWs was the first pathway identified in astrocytes (Finkbeiner, 1992). In this study it was shown that neither the direction nor the velocity of glutamate-induced intercellular Ca2+ waves were affected by rapid superfusion and that two gap junction channel blockers impaired Ca2+ wave spread between astrocytes without affecting this spread within cells. This finding together with several others performed in different systems (Blomstrand et al., 1999; Charles et al., 1991, 1992; Enkvist and McCarthy, 1992; Guan et al., 1997; Leybaert et al., 1998; Nedergaard, 1994; Saez et al., 1989; Scemes et al., 1998; Venance et al., 1995) provided a strong basis supporting the view that gap junction channels played a crucial role in the transmission of Ca2+ signals between astrocytes. It should be mentioned, however, that some of these early experiments performed using compounds that block gap junction channels may have not allowed the selective discrimination between gap junction-dependent and -independent pathways for ICW transmission. For instance, several gap junction channel/hemichannel blockers (heptanol, octanol, carbenoxolone, flufenamic acid, and mefloquine) have been recently reported to prevent ATP-dependent amplification of ICWs under low divalent cation solutions by acting on P2X7 receptors (Suadicani et al., 2006).

Evidence for the participation of an extracellular pathway for the spread of intercellular Ca2+ waves in astrocytes, first described in the non-coupled mast cells (Osipchuk and Cahalan, 1992), was provided by Enkvist and McCarthy (1992), showing that Ca2+ waves could cross cell bare areas in confluent cultures of cerebral astrocytes. Later, Hassinger et al. (1996) showed that electrically-induced Ca2+ waves in cultured astrocytes were able to cross cell-free areas up to 120 μm and travel with similar velocity between confluent cells and through the acellular lanes; moreover, the extent and direction of waves traveling in confluent cultures were shown to be affected by superfusion (Hassinger et al., 1996). It was then demonstrated that ATP was the extracellular molecule released by stimulated astrocytes and that this messenger also mediated the acellular transmission of Ca2+ waves (Guthrie et al., 1999). Such findings provided an explanation for the results showing that Ca2+ waves were not totally abolished in conditions where coupling was reduced, as in the case of astrocytes derived from Cx43-null mice (Naus et al., 1997; Scemes et al., 1998), or astrocytes treated with oleomide and anandamide, a condition that totally prevented dye- and electrical-coupling (Guan et al., 1997), and why blocking purinergic receptors with the P2R antagonist suramin totally prevented this spread (Guan et al., 1997; Zanotti and Charles, 1997).

As mentioned above, calcium signals can be transmitted through the diffusion of an extracellular molecule acting on membrane receptors. Except for striatal astrocytes, which display a prominent Ca2+ response to glutamate (Cornell-Bell et al., 1990; Finkbeiner, 1992), astrocytes from other brain regions, including the cortex (Guthrie et al., 1999), retina (Newman and Zahs, 1997) and spinal cord (Scemes et al., 2000; Scemes, unpublished observations), are more responsive to ATP than to glutamate. Astrocytes in situ and in vitro express, at different levels, several ionotropic and metabotropic P2 purinergic receptors, some of which have been implicated in the transmission of calcium signals (Fumagalli et al., 2003). Among the metabotropic P2Y receptors, the P2Y1R and P2Y2R subtypes are likely those predominantly expressed in astrocytes (Ho et al., 1995; Idestrup and Salter, 1998; Zhu and Kimelberg, 2001, 2004). Although both of these G-coupled P2Rs generate PLC and IP3 upon stimulation and thus contribute to generating Ca2+ elevations, they differ with regard to their sensitivity and selectivity for nucleotides; with the exception of ATP that is an agonist (in the micromolar range) at both receptors, the purine diphosphate nucleotide ADP is a potent agonist (in the nanomolar range) at the P2Y1R while the pyrimidine triphosphate nucleotide UTP stimulates (in the micromolar range) P2Y2R but not P2Y1R (Burnstock and Knight, 2004). Given the presence of ectonucleotidases at the cell surface that readily hydrolyze ATP to form ADP before the full hydrolysis into adenosine (Wink et al., 2006), signaling through P2Y1R activation is likely to predominate.

Using a P2R-null astrocytoma (1321N1) cell line to selectively express P2YR, Gallagher and Salter (2003) and Suadicani et al. (2004) reported that both P2Y1R and P2Y2R were equally efficient to sustain Ca2+ wave spread and that, however, the properties (velocity, extent, and shape) of these waves differed. Although differences in sensitivity of these two P2 receptor subtypes to ATP can in part explain why ICWs traveling between P2Y1R and P2Y2R differ (Gallagher et al., 2003), it is also likely that gap junction channels contribute to modulating the velocity, distance, and the shape of these extracellular generated waves. For instance, by overexpressing the Cx43 in this poorly coupled astrocytoma cell line stably expressing P2Y1R and P2Y2R subtypes, a 40% decrease in the rate of ICW transmission was observed (Suadicani et al., 2004). Moreover, overexpression of Cx43 in P2Y1R and P2Y4R-cells caused dramatic changes in the shape and distance of ICW spread; the non-wave shape, saltatory behavior of Ca2+ waves traveling amongst poorly coupled P2Y1R expressing cells assumed a more homogeneous, wave-shaped form in better coupled P2Y1R astrocytoma cells, while the limited spread of Ca2+ signals provided by P2Y4R, was practically abolished by increasing gap junctional communication (Suadicani et al., 2004).

These studies illustrate that the properties of Ca2+ signal transmission not only depend on the (sub)-type of membrane receptors but also on the degree of gap junction mediated intercellular coupling. If, for example, an agonist (at its maximal effective concentration at a particular receptor) is not sufficient to generate appropriate quantities of Ca2+ mobilizing second messengers (e.g., IP3) to sustain long distance Ca2+ signal transmission, the increase in the effective volume of the intracellular compartment provided by the gap junction channels will certainly dissipate the gradient to levels below threshold and the wave will be terminated (Giaume and Venance, 1998; Suadicani et al., 2004). Alternatively, gap junction channels could recruit non-responsive cells into a network of cells expressing receptors that more efficiently generate second messengers (Venance et al., 1998). Thus, as initially proposed (Hassinger et al., 1996), both gap junction dependent and independent pathways participate in the transmission of Ca2+ signals between astrocytes; however, the relative contribution of each of these pathways is likely to depend upon developmental, regional, and physiological states. Accordingly, it has been recently shown in acute brain slices that depending on the brain regions (cortex versus hippocampus and corpus callosum), the pathway mediating the transmission of Ca2+ signals in brain slices is different (Haas et al., 2006). Another example illustrating that Ca2+ waves can utilize different routes when traveling between glial cells was provided in whole mounts of mouse retina, where astrocyte-to-astrocyte Ca2+ waves are mainly mediated by the diffusion of second messengers through gap junction channels, whereas astrocyte-to-Mueller cells are basically dependent on the diffusion of ATP through the extracellular space (Newman, 2001, 2003, 2004).

REGENERATIVE VS NON-REGENERATIVE INTERCELLULAR CA2+ WAVE TRANSMISSION

For both gap junction-dependent and -independent pathways discussed above, the basic law governing Ca2+ signal transmission is provided by diffusion equations, and therefore, diffusional parameters are expected to play a significant role limiting the extent to which these signals propagate. However, regenerative models for Ca2+ transmission have been proposed. These models are derived from evidence obtained from several independent groups indicating that, upon stimulation, astrocytes were able to release ATP and glutamate (Ballerini et al., 1996; Kimelberg et al., 1990, 1995; Parpura et al., 1994, 1995; Queiroz et al., 1997, 1999). The release of these Ca2+-mobilizing “gliotransmitters” can potentially feedback on the astrocytic population, in an autocrine fashion, thus amplifying the extent to which these Ca2+ signals are transmitted (Stout et al., 2002; Suadicani et al., 2006). In the studies performed by Hassinger et al. (1996) and Guthrie et al. (1999) showing that astrocyte Ca2+ waves depended upon the release of the extracellular messenger ATP, the authors also proposed a mechanistic model by which ATP released from the stimulated cells would activate P2R receptors, which would then lead to mobilization of intra-cellular Ca2+ in the neighboring cell that in turn would be followed by the release of ATP from this neighboring cell. This succession of events would then occur sequentially along the ICW path. Although recent evidence supports the hypothesis that ATP induces ATP release from astrocytes (Anderson et al., 2004), this regenerative ATP release model, however, does not explain why Ca2+ waves travel within defined limits. By taking advantage of the dominant role of gap junctions in the propagation of calcium waves in rat striatal astrocytes, Giaume and Venance (1998) proposed that limiting factors linked to intracellular calcium signaling (PLC activity, calcium buffering, filling and re-filling of internal stores) contribute to setting a threshold in cells at the edge of the ICW that resulted in stopping the propagation. However, this process of ICW spread through gap junctions is not totally passive but requires a regenerative process dependent upon calcium activation of PLCγ to produce new IP3 in the receiving cells. This regenerative but limited intercellular signaling was then tested by a mathematical approach that reproduced the propagation properties of ICWs (Hofer et al., 2002).

As a counter-proposal for such regenerative model of Ca2+ wave transmission, Nedergaard’s group (Arcuino et al., 2002; Cotrina et al., 1998, 2000) suggested a non-regenerative model based on a point source of ATP release, such that ATP released from a single cell would diffuse and stimulate a limited number of nearby cells. Evidence in favor of such a non-regenerative model of Ca2+ wave transmission is their observation that only cells located at the epicenter of a spontaneously generated Ca2+ wave were permeable to molecules (propidium iodide; 562 Da) large enough to allow the release of ATP (Arcuino et al., 2002) and that the distance traveled by waves crossing cell-free areas was the same as those traveling between cells (Arcuino et al., 2004). This point source release mechanism of initiation of ICWs from the stimulated cell, together with P2R activation and gap junction-mediated diffusion of IP3, have been incorporated into a recent mathematical model of ICW transmission in astrocytes (Iacobas et al., 2006).

Although all evidence so far generated indicates that Ca2+ waves are spatially restricted, it is technically difficult to distinguish between the regenerative and non-regenerative models. For instance, it is possible that due to the presence of ectonucleotidases at the membrane surface of cells, and/or the hydrolysis of ATP on the extracellular solution, the concentration of extracellular ATP decreases with distance of stimulation and therefore the concentration of the agonist will not attain the levels necessary to trigger ATP release in cells located at the wave front. In favor of this hypothesis are the observations that the concentration of ATP in the extracellular solution declines 10-fold (from 78 μM to 6.8 μM) over a distance of 100 μm (Newman, 2001) and that the EC50 value necessary for ATP to induce ATP release from astrocytes is 144 μM (Anderson et al., 2004).

Also important for the evaluation of whether or not and the extent to which ICW transmission involves a regenerative process is certainly dependent upon studies aimed to identify the pathways of gliotransmitter release as well as the stimulation parameters necessary to activate a particular pathway. In this regard, several sites of gliotransmitter release have been identified, including exocytotic vesicles, anion channels, pore-forming P2X7 receptors, and connexin hemichannels. The properties, relevance, and evidence in favor or against each of the pathways are reviewed in this special issue.

POTENTIAL TARGETS FOR CALCIUM WAVES IN ASTROCYTES

If one considers that calcium signaling is a major way by which astrocytes encode and transmit information, it is likely that during the passage of a wave several calcium-dependent targets would be activated leading to changes in astrocytes engaged in the wave. Moreover, in certain cases the passage of a wave could lead to the priming of the astrocytes, thus leaving a “print” that persists and modifies forthcoming astrocytic responses, setting the cellular basis for plasticity in glial cells. The understanding of the consequences of the engagement of these calcium-dependent events should provide a more comprehensive picture of what is the role of these ICWs. Of course to reach such a goal, the spatial distribution, frequency, amplitude, and pattern of propagating events would have to be considered. In addition, the possibility of interaction between several waves triggered from different sites would also be of importance. Actually, we are far from that and what can be realistically achieved first is the identification of potential targets that could be activated following the occurrence of a calcium wave. In fact, besides the generation of the calcium-dependent release of “gliotransmitters” that will be reviewed in the following sections, several categories of cellular and molecular events can be targets that are affected during or after the propagation of calcium waves (Fig. 1B). Such targets include membrane effectors whose activity is calcium-dependent. First, there is now abundant evidence indicating that astrocytes express various classes of calcium-dependent ion channels (see Olsen, 2005), mainly potassium channels. Indeed, three K+ channel types (BK, IK, and SK) can be distinguished by their biophysical properties, calcium-sensitivity, and their differential pharmacology with regard to toxins. So far, BK and SK, which are sensitive to [Ca2+]i in the micromolar and nanomolar ranges, respectively, have been described in astrocytes (Armstrong et al., 2005; Byschkov et al., 2001; Gebremedhim et al., 2003; Nowak et al., 1987; Price et al., 2002; Quandt and MacVicar, 1986). They constitute potential targets of propagating calcium waves and both channel types have been shown to be activated by endothelin-1 (Bychkov et al., 2001), a vasoactive peptide that was also reported to trigger calcium waves in cultured astrocytes (Venance et al., 1997). Interestingly, this peptide induces a biphasic response in astrocytes, which results in a transient depolarization followed by a sustained hyperpolarization (Bychkov et al., 2001). Second, calcium waves may also be important to amplify calcium signals by activating calcium release from internal stores mainly in the endoplasmic reticulum; indeed such rise in [Ca2+]i can operate either through a calcium-induced calcium release process involving ryanodine receptor type 3 (Matyash et al., 2001) or by a cooperative activation of IP3 receptors (Marchant and Taylor, 1997; Meyer and Stryer, 1988). However, since in astrocytes the main source of Ca2+ release from internal stores is mediated through the activation of IP3 receptors (Charles et al., 1993, Venance et al., 1997), amplification of a rise in [Ca2+]i may operate through this pathway. Third, the activity of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger can be increased as a secondary step of the rise in [Ca2+]i (Carafoli and Chiesi, 1992). In astrocytes, this exchanger has been identified at the plasma and the endoplasmic reticulum membranes and may be an important mechanism by which glia regulate the ionic content within the cytoplasm and of the extracellular space (see Olsen, 2005).

Biochemical cascades could also be targeted following ICWs since Ca2+ binds to various molecular targets that trigger or contribute to intracellular signal transduction pathways. These include the Ca2+-dependent phospholipases such as sub-classes of PLC and PLA2. These phospholipases also might provide a certain degree of facilitation, given that during the waves, their activation causes an increase in the efficacy of metabotropic receptors to which they are coupled (Glowinski et al., 1994; Oertner and Matus, 2005). Interestingly, this could be the case of P2Y metabotropic receptors coupled to PLC that are involved in the control of the extent of ICW spread (see above). Moreover, downstream calcium-dependent elements such as the phosphatases and protein kinases, including the two most widely studied calcium-sensitive protein kinases PKC and CaM kinase, are also potential targets of calcium waves. These facilitatory mechanisms can lead to the production of second or transmembrane messengers that may act distally and affect the properties of neighboring astrocytes and also those of surrounding neurons and smooth muscles, and endothelial cells. Finally, these transduction pathways can also interact with cytoplasmic enzymes linked to calcium-dependent effectors and further transfer signals to the nucleus and thus control gene expression. In addition, cytoskeletal elements can be indirect targets of the propagating rises in [Ca2+]i. For instance, in neurons many calcium-dependent proteins that regulate the turn-over of filamentous actin have been proposed to transduce intracellular Ca2+ levels into spine shape changes (Oertner and Matus, 2005). Interestingly, rapid spontaneous motility was recently reported to occur in astrocytes at processes close to active synaptic terminals, a location expected to induce calcium responses in astrocytes (Hirrlinger et al., 2004). Thus, changes in [Ca2+]i during the propagation of waves could be associated with rapid motility and morphological changes of astrocytes.

Finally, the radius of action (<5 μm) and the life-time (<1 ms) of calcium ions are rather limited in the cytoplasm making Ca2+ itself a restricted rather than a global messenger (Allbritton et al., 1992). However, when [Ca2+]i is increased in astrocytes it may diffuse to neighboring astrocytes through gap junction channels, which are known to be permeable to Ca2+ (Saez et al., 1989), only if the site of [Ca2+]i rise occurs in the vicinity of these intercellular channels. Indeed, although the main permeating messenger is thought to be IP3 (Venance et al., 1997), Ca2+ can also contribute to the propagation process (Giaume and Venance, 1998). In this case, it is then expected that Ca2+ entering within a coupled cells through this pathway can secondarily activate the above listed elements.

FUNCTIONAL CONSEQUENCES OF INTERCELLULAR CALCIUM WAVES

As the result of the activation of several of these molecular targets, the propagation of calcium waves may have functional consequences in astrocytes themselves and in the interactions that they achieve with other cellular partners. A first obvious interaction is that the rise in [Ca2+]i might directly spread from an astrocyte to an adjacent neuron through gap junction channels and thus support a direct mode of neuroglial interaction. Such a relationship was initially reported in co-cultures of neurons and astrocytes in which calcium waves initiated in glia were shown to induce calcium responses in some neurons that were blocked by gap junction inhibitors (Nedergaard, 1994). Although this interpretation was challenged by studies demonstrating that glutamate release from astrocytes is also involved (Parpura et al., 1994), several subsequent studies have confirmed that functional gap junctions between these two cell types can be formed in co-cultures and brain slices under certain conditions (Alvarez-Maubecin et al., 2000; Bittman et al., 2002; Froes et al., 1999). However, up to now there is no evidence for functional coupling between mature neurons and astrocytes; thus this property could be rather limited to early stages of CNS development.

Another consequence of calcium waves that has been recently well documented is the control of synaptic activity. This pioneering observation was performed in co-cultures by recording neuronal spontaneous and evoked activity during the passage of an ICW triggered in the underlying carpet of astrocytes (Araque et al., 1998a). This was then confirmed and complemented by brain slice studies, leading to a full picture of an interaction loop involving active neurons, astrocytic responses, and release mechanisms of gliotransmitter that finally results in changes in neuronal activity (Fellin and Carmignoto, 2004; Haydon, 2001; Volterra and Meldolesi, 2005). Such findings have contributed to the emerging concept of an active glial role in the control of synaptic transmission in which intra- and intercellular calcium signaling in astrocytes are key elements.

A new role of calcium waves was also recently demonstrated in the generation of Na1-mediated metabolic waves in astrocytes (Bernardinelli et al., 2004). Indeed, glutamate released in the synaptic cleft is rapidly taken up by surrounding astrocytes and one consequence of this uptake is the triggering of a molecular cascade that provides metabolic substrates to neurons (Magistretti et al., 1999). This glutamate uptake results in an increase in intracellular Na+ and the activation of Na+/K+-ATPase. Single cell stimulation in cultured astrocytes generates Na+ waves in parallel with Ca2+ waves although the spatial and temporal properties of the waves carried by the two pathways are different. Moreover, Na+ waves give rise to spatially correlated increases in glucose up-take, indicating the occurrence of metabolic waves (Bernardinelli et al., 2004). While maneuvers that inhibit calcium waves also inhibit Na+ waves, the inhibition of the Na+/K+ co-transporter or the enzymatic degradation of extracellular glutamate do not affect the propagation of calcium waves. All together, these observations suggest that astrocytes, through their properties by which they propagate intercellular calcium signals, also mediate Na+ and metabolic waves that should affect feeding of neurons and secondarily their activity.

Interestingly, a single astrocyte can enwrap a large number of synapses and also be in contact with cerebral vessels (Peters, 1991; Simard et al., 2003; Ventura and Harris, 1999). Accordingly, another important consequence of ICW propagation concerns the interface between astrocytes and the vasculature. Indeed, the intimate relationship between astrocytic processes, termed “end-feet,” and blood vessels is well-known, which together contribute a cellular architecture of gliovascular units (Nedergaard et al., 2003). Recently, in vivo imaging has provided convincing demonstrations of the functional role of such interface units. Indeed, [Ca2+]i increases in astrocyte end-feet have been reported to produce either a dilation or a constriction of blood vessels (Mulligan and MacVicar, 2004; Zonta et al., 2003). Although these observations seem conflicting, this could be due to difference in pharmacological treatments of the brain slices used (Peppiatt and Attwell, 2004). Moreover, a recent report indicates that in acutely isolated retina, light flashes and glial stimulation can both evoke dilatation or constriction of arterioles (Metea and Newman, 2006). Finally, astrocytes in the somatosensory cortex in vivo have been shown to possess a powerful mechanism for rapid vasodilation, indicating that one of their physiopathological roles is to mediate the control of microcirculation in response to neuronal activity and its dysfunction (Takano et al., 2006). Altogether, these observations are important because they could provide the basis to explain the contribution of astrocytes to deregulation of cerebral circulation in brain pathologies.

CONCLUSIONS

There are still many aspects of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling that need to be further explored to appreciate in more detail the importance of astrocyte ICW for brain function under physiological and pathological conditions (for reviews see Butt et al., 2004; Charles and Giaume, 2002; Ostrow and Sachs, 2005). An essential question to be addressed is whether these waves occur in vivo and in which situation those global intracellular Ca2+ transients are transmitted to neighboring astrocytes. This still waits for estimations of the size of astrocyte networks involved in an ICW, by determining the distribution and properties of Ca2+-mobilizing membrane receptors and ion channels as well as the distribution and properties of gap junctional communication. For instance, to better resolve whether and how astrocytes can integrate Ca2+ signals, one has to determine the components and cellular locations of the Ca2+ microdomains and to resolve the conditions in which the elementary Ca2+ events (puffs) are transformed into a global Ca2+ response. For that, the readers are certainly going to benefit from the reviews in the first half of this special issue describing the dynamics of Ca2+ signals in glia.

Understanding the role of astrocyte Ca2+ signals in CNS function also involves the identification of the intracellular targets activated by these Ca2+ transients, and the functional consequences of these activated pathways for the interactions that astrocytes maintain with themselves and with other cellular types. Moreover, to provide a more complete description of astrocyte Ca2+ waves, a better knowledge of mechanisms by which transmitters are released from these cells is required. “Gliotransmitters” are not only expected to affect neuronal activity and brain microcirculation, but are also expected to feedback on astrocytes and thus modulate their “Ca2+ excitability”. Because several mechanisms of gliotransmitter release have been proposed in the last few years, it is fundamental to define the properties and conditions in which each of these release sites are brought into action. Presently, this field still faces controversial data and interpretations that may or may not be contradictory, but certainly needs to be discussed and analyzed from the different viewpoints of workers in these areas. We certainly consider that such a critical evaluation is timely, and we hope that by bringing together in this special issue of Glia expertise from different laboratories we will provide the readers with state-of-the-art discussions on the “mechanisms of transmitter release from astrocytes.”

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: RO1-NS41023 to ES; Grant sponsor: INSERM.

REFERENCES

- Allbritton NL, Meyer T, Stryer L. Range of messenger action of calcium ion and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Science. 1992;258:1812–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.1465619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Maubecin V, Garcia-Hernandez F, Williams JT, Van Bockstaele EJ. Functional coupling between neurons and glia. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4091–4098. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04091.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CM, Bergher JP, Swanson RA. ATP-induced ATP release from astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2004;88:246–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG. Glutamate-dependent astrocyte modulation of synaptic transmission between cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998a;10:2129–2142. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Sanzgiri RP, Parpura V, Haydon PG. Calcium elevation in astrocytes causes an NMDA receptor-dependent increase in the frequency of miniature synaptic currents in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998b;18:6822–6829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06822.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcuino G, Cotrina M, Nedergaard M. Mechanism and significance of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling. In: Hatton GL, Parpura V, editors. Glial neuronal signaling. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht: 2004. pp. 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Arcuino G, Lin JH, Takano T, Liu C, Jiang L, Gao Q, Kang J, Nedergaard M. Intercellular calcium signaling mediated by point-source burst release of ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9840–9845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152588599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong WE, Rubrum A, Teruyama R, Bond CT, Adelman JP. Immunocytochemical localization of small-conductance, calcium-dependent potassium channels in astrocytes of the rat supraoptic nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2005;491:175–185. doi: 10.1002/cne.20679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballerini P, Rathbone MP, Di Iorio P, Renzetti A, Giuliani P, D’Alimonte I, Trubiani O, Caciagli F, Ciccarelli R. Rat astroglial P2Z (P2X7) receptors regulate intracellular calcium and purine release. Neuroreport. 1996;7:2533–2537. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611040-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres BA, Koroshetz WJ, Chun LLY, Corey DP. Ion channel expression by white matter glia: Type-1 astrocyte. Neuron. 1990;5:527–544. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90091-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardinelli Y, Magistretti PJ, Chatton JY. Astrocytes generate Na+-mediated metabolic waves. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14937–14942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405315101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. Signal transduction. The calcium entry pas de deux. Science. 2000a;287:1604–1605. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000b;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprovanny I, Ehrlich BE. The inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptors. J Membr Biol. 1995;145:205–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00232713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzi P, Gundersen V, Galbete JL, Seifert G, Steinhauser C, Pilati E, Volterra A. Astrocytes contain a vesicular compartment that is competent for regulated exocytosis of glutamate. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:613–620. doi: 10.1038/nn1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittman K, Becker DL, Cicirata F, Parnavelas JG. Connexin expression in homotypic and heterotypic cell coupling in the developing cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2002;443:201–212. doi: 10.1002/cne.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomstrand F, Aberg ND, Eriksson PS, Hansson E, Ronnback L. Extent of intercellular calcium wave propagation is related to gap junction permeability and level of connexin43 expression in astrocytes in primary cultures from four brain regions. Neuroscience. 1999;92:255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitier E, Rea R, Duchen MR. Mitochondria exert a negative feedback on the propagation of intracellular Ca2+ waves in rat cortical astrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:795–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Knight GE. Cellular distribution and function of P2 receptor subtypes in different systems. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;240:31–304. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)40002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AM, Pugh M, Hubbard P, James G. Functions of optic nerve glia: Axoglia signaling in physiology and pathology. Eye. 2004;18:1110–1121. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov R, Glowinski J, Giaume C. Sequential and opposite regulation of two outward K+ currents by ET-1 in cultured striatal astrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1373–C1384. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.4.C1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E, Chiesi M. Calcium pumps in the plasma and intracellular membranes. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1992;32:209–241. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-152832-4.50007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles A. Intercellular calcium waves in glia. Glia. 1998;24:39–49. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199809)24:1<39::aid-glia5>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles AC, Dirksen ER, Merrill JE, Sanderson MJ. Mechanisms of intercellular calcium signaling in glial cells studied with dantrolene and thapsigargin. Glia. 1993;7:134–145. doi: 10.1002/glia.440070203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles AC, Giaume G. Intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes: Underlying mechanisms and functional consequences. In: Volterra A, Magistretti P, Haydon PG, editors. The tripartite synapse: Glia in synaptic transmission. Oxford University Press; Oxford, NY: 2002. pp. 100–126. [Google Scholar]

- Charles AC, Merrill JE, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ. Intercellular signaling in glial cells: Calcium waves and oscillations in response to mechanical stimulation and glutamate. Neuron. 1991;6:983–992. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90238-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles AC, Naus CC, Zhu D, Kidder GM, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ. Intercellular calcium signaling via gap junctions in glioma cells. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:195–201. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coco S, Calegari F, Pravettoni E, Pozzi D, Taverna E, Rosa P, Matteoli M, Verderio C. Storage and release of ATP from astrocytes in culture. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1354–1362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell-Bell AH, Finkbeiner SM, Cooper MS, Smith SJ. Glutamate induces calcium waves in cultured astrocytes: Long-range glial signaling. Science. 1990;247:470–473. doi: 10.1126/science.1967852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotrina ML, Lin JH, Alves-Rodrigues A, Liu S, Li J, Azmi-Ghadimi H, Kang J, Naus CC, Nedergaard M. Connexins regulate calcium signaling by controlling ATP release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15735–15740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotrina ML, Lin JH, Lopez-Garcia JC, Naus CC, Nedergaard M. ATP-mediated glia signaling. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2835–2844. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02835.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JW, Chernjavsky A, Smith SJ. Neuronal activity triggers calcium waves in hippocampal astrocyte networks. Neuron. 1992;8:429–440. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90271-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkvist MO, McCarthy KD. Activation of protein kinase C blocks astroglial gap junction communication and inhibits the spread of calcium waves. J Neurochem. 1992;59:519–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller MB, Wellis DP, Stellwagen D, Werblin FS, Shatz CJ. Requirement for cholinergic synaptic transmission in the propagation of spontaneous retinal waves. Science. 1996;272:1182–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T, Carmignoto G. Neurone-to-astrocyte signalling in the brain represents a distinct multifunctional unit. J Physiol. 2004;559:3–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch EA, Turner TJ, Goldin SM. Calcium as a coagonist of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate-induced calcim release. Science. 1991;252:443–446. doi: 10.1126/science.2017683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner S. Calcium waves in astrocytes-filling in the gaps. Neuron. 1992;8:1101–1108. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90131-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froes MM, Correia AH, Garcia-Abreu J, Spray DC, de Carvalho AC Campos, Neto MV. Gap-junctional coupling between neurons and astrocytes in primary central nervous system cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7541–7546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli M, Brambilla R, D’Ambrosi N, Volonte C, Matteoli M, Verderio C, Abbracchio MP. Nucleotide-mediated calcium signaling in rat cortical astrocytes: Role of P2X and P2Y receptors. Glia. 2003;43:218–223. doi: 10.1002/glia.10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher CJ, Salter MW. Differential properties of astrocyte calcium waves mediated by P2Y1 and P2Y2 recetors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6728–6739. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06728.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebremedhin D, Yamaura K, Zhang C, Bylund J, Koehler RC, Harder DR. Metabotropic glutamate receptor activation enhances the activities of two types of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in rat hippocampal astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1678–1687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01678.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaume C, Venance L. Intercellular calcium signaling and gap junctional communication in astrocytes. Glia. 1998;24:50–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowinski J, Marin P, Tence M, Stella N, Giaume C, Premont J. Glial receptors and their intervention in astrocyto—astrocytic and astrocyto—neuronal interactions. Glia. 1994;11:201–208. doi: 10.1002/glia.440110214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovina VA, Blaustein MP. Unloading and refilling of two classes of spatially resolved endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ stores in astrocytes. Glia. 2000;31:15–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(200007)31:1<15::aid-glia20>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Spitzer NC. Distinct aspects of neuronal differentiation encoded by frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients. Nature. 1995;375:784–787. doi: 10.1038/375784a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan X, Cravatt BF, Ehring GR, Hall JE, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB. The sleep-inducing lipid oleamide deconvolutes gap junction communication and calcium wave transmission in glial cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1785–1792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie PB, Knappenberger J, Segal M, Bennett MV, Charles AC, Kater SB. ATP released from astrocytes mediates glial calcium waves. J Neurosci. 1999;19:520–528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas B, Schipke CG, Peters O, Sohl G, Willecke K, Kettenmann H. Activity-dependent ATP-waves in the mouse neocortex are independent from astrocytic calcium waves. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:237–246. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassinger TD, Guthrie PB, Atkinson PB, Bennett MV, Kater SB. An extracellular signaling component in propagation of astrocytic calcium waves. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13268–13273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon PG. GLIA: Listening and talking to the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:185–193. doi: 10.1038/35058528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirase H, Qian L, Barthó P, Buzsáki G. Calcium dynamics of cortical astrocytic networks in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:494–499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirrlinger J, Hulsmann S, Kirchhoff F. Astroglial processes show spontaneous motility at active synaptic terminals in situ. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:2235–2239. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C, Hicks J, Salter MW. A novel P2-purinoceptor expressed by a subpopulation of astrocytes from the dorsal spinal cord of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:2909–2918. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer T, Venance L, Giaume C. Control and plasticity of intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes: A modeling approach. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4850–4859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-04850.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobas DA, Suadicani SO, Spray DC, Scemes E. A stochastic two-dimensional model of intercellular Ca2+ wave spread in glia. Biophys J. 2006;90:24–41. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.064378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idestrup CP, Salter MW. P2Y and P2U receptors differentially release intracellular Ca2+ via the phospholipase c/inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate pathway in astrocytes from the dorsal spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1998;86:913–923. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Jiang L, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated potentiation of inhibitory synaptic transmission. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:683–692. doi: 10.1038/3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelberg HK, Goderie SK, Higman S, Pang S, Waniewski RA. Swelling-induced release of glutamate, aspartate, and taurine from astrocyte cultures. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1583–1591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-05-01583.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelberg KH, Rutledge E, Goderie S, Chamiga C. Astrocytic swelling due to hypotonic or high K+ medium causes inhibition of glutamate and aspartate uptake and increase their release. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15:409–416. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumada T, Komuro H. Completion of neuronal migration regulated by loss of Ca2+ transients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8479–8484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leybaert L, Paemeleire K, Strahonja A, Sanderson MJ. Inositoltrisphosphate-dependent intercellular calcium signaling in and between astrocytes and endothelial cells. Glia. 1998;24:398–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacVicar BA, Tse RWY. Norepinephrine and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate enhance a nifedipine-sensitive calcium current in cultured rat astrocytes. Glia. 1988;1:359–365. doi: 10.1002/glia.440010602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti PJ, Pellerin L, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. Energy on demand. Science. 1999;283:496–497. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant JS, Taylor CW. Cooperative activation of IP3 receptors by sequential binding of IP3 and Ca2+ safeguards against spontaneous activity. Curr Biol. 1997;7:510–518. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero H, Astion ML, Coles A, Orkland RK. Facilitation of voltage-gated ion channels in frog neuroglia by nerve impulses. Nature. 1989;339:378–380. doi: 10.1038/339378a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyash M, Matyash V, Noble C, Sorrentino V, Kettenmann H. Requirement of functional ryanodine receptor type 3 for astrocyte migration. FASEB J. 2002;16:84–86. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0380fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KD, Salm AK. Pharmacologically-distinct subsets of astroglia can be identified by their calcium response to neuroligands. Neuroscience. 1991;41:325–333. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90330-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metea MR, Newman EA. Glial cells dilate and constrict blood vessels: A mechanism of neurovascular coupling. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2862–2870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4048-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T, Stryer L. Molecular model for receptor-stimulated calcium spiking. Proc Natl Aacd Sci USA. 1988;85:5051–5055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mothet JP, Pollegioni L, Ouanounou G, Matineau M, Fossier P, Baux G. Glutamate receptor activation triggers a calcium-dependent and SNARE protein-dependent release of the gliotransmitter D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5606–5611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408483102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan SJ, MacVicar BA. Calcium transients in astrocyte end-feet cause cerebrovascular constrictions. Nature. 2004;431:195–199. doi: 10.1038/nature02827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naus CC, Bechberger JF, Zhang Y, Venance L, Yamasaki H, Juneja SC, Kidder GM, Giaume C. Altered gap junctional communication, intercellular signaling, and growth in cultured astrocytes deficient in connexin43. J Neurosci Res. 1997;49:528–540. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19970901)49:5<528::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard M. Direct signaling from astrocytes to neurons in cultures of mammalian brain cells. Science. 1994;263:1768–1771. doi: 10.1126/science.8134839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard M, Ransom B, Goldman SA. New roles for astrocytes: Redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA. Propagation of intercellular calcium waves in retinal astrocytes and Muller cells. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2215–2223. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02215.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA. Glial cell inhibition of neurons by release of ATP. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1659–1666. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01659.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA. Glial modulation of synaptic transmission in the retina. Glia. 2004;47:268–274. doi: 10.1002/glia.20030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA. Calcium increases in retinal glial cells evoked by light-induced neuronal activity. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5502–5510. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1354-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA, Zahs KR. Calcium waves in retinal glial cells. Science. 1997;275:844–847. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5301.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak L, Ascher P, Berwald-Netter Y. Ionic channels in mouse astrocytes in culture. J Neurosci. 1987;7:101–109. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-01-00101.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertner TG, Matus A. Calcium regulation of actin dynamics in dendritic spines. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen ML. Voltage-activated ion channels in glial cells. In: Kettenmann H, Ransom BR, editors. Neuroglia. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. pp. 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Osipchuk Y, Cahalan M. Cell-to-cell spread of calcium signals mediated by ATP receptors in mast cells. Nature. 1992;359:241–244. doi: 10.1038/359241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow LW, Sachs F. Mechanosensation and endothelin in astrocytes: Hypothetical roles in CNS physiopathology. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:488–508. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker I, Yao Y. Regenerative release of calcium from functionally discrete subcellular stores by inositol trisphosphate. Proc R Soc Lond. 1994;246:269–274. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Basarsky TA, Liu F, Jeftinija K, Jeftinija S, Haydon PG. Glutamate-mediated astrocyte-neuron signalling. Nature. 1994;369:744–747. doi: 10.1038/369744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Fang Y, Basarsky T, Jahn R, Haydon PG. Expression of synaptobrevin II, cellubrevin and syntaxin but not SNAP-25 in cultured astrocytes. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:489–492. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parri HR, Gould TM, Crunelli V. Spontaneous astrocytic Ca2+ oscillations in situ drive NMDAR-mediated neuronal excitation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:803–812. doi: 10.1038/90507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual O, Casper KB, Kubera C, Zhang J, Revilla-Sanchez R, Sul J-Y, Takano H, Moss SJ, McCarthy K, Haydon PG. Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks. Science. 2005;310:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1116916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppiatt C, Attwell D. Neurobiology: Feeding the brain. Nature. 2004;431:137–138. doi: 10.1038/431137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HDF. The fine structure of the central nervous: Neurons and their supportive cells. In: Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HDF, editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford, NY: 1991. pp. 276–295. [Google Scholar]

- Peters JL, Earnest BJ, Tjalkens RB, Cassone VM, Zoran MJ. Modulation of intercellular calcium signaling by melatonin in avian and mammalian astrocytes is brain region-specific. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:370–380. doi: 10.1002/cne.20779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Ludwig JW, Mi H, Schwarz TL, Ellisman MH. Distribution of rSlo Ca2+-activated K+ channels in rat astrocyte perivascular endfeet. Brain Res. 2002;956:183–193. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt FN, MacVicar BA. Calcium activated potassium channels in cultured astrocytes. Neuroscience. 1986;19:29–41. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz G, Gebicke-Haerter PJ, Schobert A, Starke K, von Kugelgen I. Release of ATP from cultured rat astrocytes elicited by gluta-mate receptor activation. Neuroscience. 1997;78:1203–1208. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz G, Meyer DK, Meyer A, Starke K, von Kugelgen I. A study of the mechanism of the release of ATP from rat cortical astroglial cells evoked by activation of glutamate receptors. Neuroscience. 1999;91:1171–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00644-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribelayga C, Mangel SC. A circadian clock and light/dark adaptation differentially regulate adenosine in mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2005;25:215–222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3138-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez JC, Connor JA, Spray DC, Bennett MV. Hepatocyte gap junctions are permeable to the second messenger, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, and to calcium ions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2708–2712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salm AK, McCarthy KD. Norepinephrine-evoked calcium transients in cultured cerebral type 1 astroglia. Glia. 1990;3:529–538. doi: 10.1002/glia.440030612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E. Components of astrocytic intercellular calcium signaling. Mol Neurobiol. 2000;22:167–179. doi: 10.1385/MN:22:1-3:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Dermietzel R, Spray DC. Calcium waves between astrocytes from Cx43 knockout mice. Glia. 1998;24:65–73. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199809)24:1<65::aid-glia7>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Duval N, Meda P. Reduced expression of P2Y1 receptors in connexin43-null mice alters calcium signaling and migration of neural progenitor cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11444–11452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11444.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Suadicani SO, Spray DC. Intercellular communication in spinal cord astrocytes: Fine tuning between gap junctions and P2 nucleotide receptors in calcium wave propagation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1435–1445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01435.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schipke CG, Boucsein C, Ohlemeyer C, Kirchhoff F, Kettenmann H. Astrocyte Ca2+ waves trigger responses in microglial cells in brain slices. FASEB J. 2002;16:255–257. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0514fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard CA, Simpson PB, Sharp AH, Nucifora FC, Ross CA, Lange GD, Russell JT. Comparison of type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor distribution and subcellular Ca2+ release sites that support Ca2+ waves in cultured astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2317–2327. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard M, Arcuino G, Takano T, Liu QS, Nedergaard M. Signaling at the gliovascular interface. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9254–9262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09254.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson PB, Mehotra S, Langley D, Sheppard CA, Russell JT. Specialized distributions of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum proteins define Ca2+ wave amplification sites in cultured astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1998;52:672–683. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980615)52:6<672::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout CE, Costantin JL, Naus CC, Charles AC. Intercellular calcium signaling in astrocytes via ATP release through connexin hemi-channels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10482–10488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suadicani SO, Brosnan CF, Scemes E. P2X7 receptors mediate ATP release and amplification of astrocytic intercellular Ca2+ signaling. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1378–1385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3902-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suadicani SO, Flores CE, Urban-Maldonado M, Beelitz M, Scemes E. Gap junction channels coordinate the propagation of intercellular Ca2+ signals generated by P2Y receptor activation. Glia. 2004;48:217–229. doi: 10.1002/glia.20071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano T, Tian GF, Peng W, Lou N, Libionka W, Han X, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:260–267. doi: 10.1038/nn1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usowic MM, Gallo V, Cull-Candy SG. Multiple conductance channels in type-2 cerebellar astrocytes activated by excitatory amino acids. Nature. 1989;339:380–383. doi: 10.1038/339380a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venance L, Piomelli D, Glowinski J, Giaume C. Inhibition by anandamide of gap junctions and intercellular calcium signalling in striatal astrocytes. Nature. 1995;376:590–594. doi: 10.1038/376590a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venance L, Stella N, Glowinski J, Giaume C. Mechanism involved in initiation and propagation of receptor-induced intercellular calcium signaling in cultured rat astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1981–1992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-01981.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venance L, Premont J, Glowinski J, Giaume G. Gap junctional communication and pharmacological heterogeneity in astrocytes cultured from the rat striatum. J Physiol. 1998;510:429–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.429bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura R, Harris KM. Three-dimensional relationships between hippocampal synapses and astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6897–6906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-06897.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volterra A, Meldolesi J. Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: The revolution continues. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:626–640. doi: 10.1038/nrn1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Tymianski M, Jones OT, Nedergaard M. Impact of cytoplasmic calcium buffering on the spatial and temporal characteristics of intercellular calcium signals in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7359–7371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07359.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman TA, Riquelme PA, Ivic L, Flint AC, Kriegstein AR. Calcium waves propagate through radial glial cells and modulate proliferation in the developing neocortex. Neuron. 2004;43:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink MR, Braganhol E, Tamajusuku AS, Lenz G, Zerbini LF, Lieberman TA, Sevigny J, Batastini AM, Robson SC. Nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-2 (NTPDase2/CD39L1) is the dominant ectonucleotidase expressed by rat astrocytes. Neurosci. 2006;138:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong RO, Chernjavsky A, Smith SJ, Shatz CJ. Early functional neural networks in the developing retina. Nature. 1995;374:716–718. doi: 10.1038/374716a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Choi J, Parker I. Quantal puffs of intracellular Ca2+ evoked by inositol trisphosphate in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1995;482:533–553. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanotti S, Charles A. Extracellular calcium sensing by glial cells: Low extracellular calcium induces intracellular calcium release and intercellular signaling. J Neurochem. 1997;69:594–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69020594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Kimelberg HK. Developmental expression of metabotropic P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors in freshly isolated astrocytes from rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2001;77:530–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Kimelberg HK. Cellular expression of P2Y and β-AR receptor mRNAs and proteins in freshly isolated astrocytes and tissue sections from the CA1 region of P8-12 rat hippocampus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;148:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonta M, Angulo MC, Gobbo S, Rosengarten B, Hossmann KA, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:43–50. doi: 10.1038/nn980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]