Abstract

Three kinds of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) determinants have been discovered and have been shown to be widely distributed among clinical isolates: qnr genes, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA. Few data on the prevalence of these determinants in strains from animals are available. The presence of PMQR genes in isolates from animals was determined by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing. The production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and AmpC β-lactamases in the strains was detected, and their genotypes were determined. The genetic environment of PMQR determinants in selected plasmids was analyzed. All samples of ceftiofur-resistant (MICs ≥ 8 μg/ml) isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae were selected from 36 companion animals and 65 food-producing animals in Guangdong Province, China, between November 2003 and April 2007, including 89 Escherichia coli isolates, 9 Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates, and isolates of three other genera. A total of 68.3% (69/101) of the isolates produced ESBLs and/or AmpC β-lactamases, mainly those of the CTX-M and CMY types. Of the 101 strains, PMQR determinants were present in 35 (34.7%) isolates, with qnr, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA detected alone or in combination in 8 (7.9%), 19 (18.8%), and 16 (15.8%) strains, respectively. The qnr genes detected included one qnrB4 gene, four qnrB6 genes, and three qnrS1 genes. Five strains were positive for both aac(6′)-Ib-cr and qepA, while one strain was positive for qnrS1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA. qnrB6 was flanked by two copies of ISCR1 with an intervening dfr gene downstream and sul1 and qacEΔ1 genes upstream. In another plasmid, aac(6′)-Ib-cr followed intI1 and arr-3 was downstream. PMQR determinants are highly prevalent in ceftiofur-resistant Enterobacteriaceae strains isolated from animals in China. This is the first report of the occurrence of PMQR determinants among isolates from companion animals.

Since 1998, three kinds of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) determinants have been described: Qnr (QnrA, QnrB, QnrS) (8, 13, 21), AAC(6′)-Ib-cr (32), and QepA (40). Qnr proteins belong to the pentapeptide-repeat family and protect DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV from quinolone inhibition (30). AAC(6′)-Ib-cr is a variant of AAC(6′)-Ib and is responsible for reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin or norfloxacin by N-acetylation of a piperazinyl amine (32). QepA is a quinolone efflux pump protein and shows a considerable similarity to the MFS types of efflux pumps belonging to the 14-transmembrane segment family of environmental actinomycetes (27, 40).

qnr and aac(6′)-Ib-cr determinants are widely distributed in human clinical isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae around the world (24, 28, 30, 37, 38), while only a few surveys on the prevalence of the newer qepA gene are available (18, 39). The transferability of resistant bacteria or mobile resistance determinants between animals and humans via the food chain or by direct contact has been indicated in several studies (6, 20, 22). Quinolones have also been widely used to treat livestock and for pet animal therapy in some countries. However, few reports on the occurrence of PMQR determinants among bacteria from companion animals and food-producing animals have been published, and the total strain number is limited (1, 2, 15, 42).

Quinolones and β-lactams are among the most commonly used antimicrobials in both human and veterinary clinical medicine. The association of qnr and aac(6′)-Ib-cr determinants with extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and AmpC β-lactamases has been documented (14, 23, 25, 31). A variety of β-lactamases, including extended-spectrum CTX-M and plasmid-encoded AmpC-type β-lactamases, have been identified in bacteria derived from food-producing and companion animals. Such strains may provide a reservoir for β-lactamase-producing bacteria in humans (3, 17, 19, 41). In a previous study, we showed that PMQR determinants were present among 16S rRNA methylase RmtB-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from pigs and demonstrated a strong linkage between qepA and rmtB, with qepA being present in 28 (58.%) of 48 rmtB-carrying strains (18). The aim of the present study was to investigate the prevalence of PMQR determinants among ceftiofur-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from companion and food-producing animals and to identify whether these strains produce ESBLs and/or plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases. The genetic environment of qnr and aac(6′)-Ib-cr in selected plasmids was also characterized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

Enterobacteriaceae isolates were collected from 20 animal farms and a veterinary hospital; each isolate was from a separate animal, and all 101 unique ceftiofur-resistant (MICs ≥ 8 μg/ml) strains were selected. Thirty-six strains, including 25 E. coli strains, 8 Klebsiella pneumoniae strains, 2 Enterobacter cloacae strains, and 1 Citrobacter freundii strain, were isolated from feces, vomitus, or sneeze samples from diseased pet animals (31 dogs and 5 cats) at the South China Agricultural University Veterinary Hospital in Guangzhou, China, between September 2006 and May 2007. Sixty-five strains (64 E. coli strains and 1 K. pneumoniae strain) were collected from feces or liver samples of diseased food-producing animals (29 ducks, 18 pigs, 11 chickens, 6 partridges, and 1 goose) in Guangdong Province of China from November 2003 to April 2007. The bacterial strains were identified by classical biochemical methods and by using the Microlog (release 4.2) program (Biolog). Additional strains used were E. coli V517 and E. coli J53 containing plasmid R1, Plac, or R27, which were used as standards for determination of plasmid sizes (36). E. coli J53Azir, which is resistant to azide, was used as the recipient strain in conjugation experiments (12). E. coli UAB1 (21), E. coli J53 containing plasmid PMG298 (13), a K. pneumoniae strain containing qnrS1 (10), E. coli 12 (36), and E. coli GZ3 (18) were used as positive control strains for qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA, respectively, in PCR screening experiments. Sequenced strains that were positive for ESBL and AmpC β-lactamase genes and that were obtained in our previous studies (10, 19) were used as positive controls in PCR screening experiments. E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain in antimicrobial susceptibility testing experiments.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and β-lactamase determination.

The MICs of nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and other antimicrobials were determined by agar dilution, in accordance with the guidelines of the CLSI (4, 5). The Etest (Biodisk AB, Solna, Sweden) was used to detect minimal changes in ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin susceptibility. The production of ESBLs by the strains was determined by the phenotypic confirmatory test (5), and AmpC expression was evaluated by the three-dimensional test with cefoxitin disks (16). The genotypes of the ESBL- and AmpC-positive strains were determined by PCR and sequencing.

Detection of PMQR determinants and β-lactamase-encoding genes.

The isolates were investigated for the presence of qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, aac(6′)-Ib, blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M genes by PCR amplification with the primer sets described previously (3, 19, 24, 31, 37). Two sets of primers for qnrB and qnrS were used to ensure the amplification of all subtypes (11). AmpC β-lactamases were amplified with the primers described by Perez-Perez and Hanson (26). The primers used for qepA were 5′-CGGCGGCGTGTTGCTGGAGTTCTT and 5′-CCGACAGGCCCACGACGAGGATGC. Both strands of the purified PCR products were sequenced. The DNA sequences obtained and the deduced amino acid sequences were compared with those available in the GenBank database to identify the subtypes of the qnr determinants and the β-lactamase genes. All positive PCR products of aac(6′)-Ib were further analyzed by digestion with FokI (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China) and/or direct sequencing to identify aac(6′)-Ib-cr, which lacks the FokI restriction site present in the wild-type gene.

ERIC-PCR analysis.

Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequence PCR (ERIC-PCR) was performed with all PMQR determinant-positive isolates. The PCR amplifications were performed in 25-μl volumes containing 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 U of ExTaq polymerase, 0.25 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2.5 μl of 10× amplification buffer, 10 ng of crude template DNA, and 25 pmol each of two opposing primers, primers ERIC1R (5′-ATGTAAGCTCCTGGGGATTCA-3′) and ERIC2 (5′-AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG-3′) (TaKaRa Bio, Dalian, China) (35). A negative control consisting of the same reaction mixture without a DNA template was included in each PCR. The samples were amplified as follows: 95°C for 5 min to denature the template; four-low stringency cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 26°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 40°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and finally, 72°C for 10 min.

Conjugation experiments and plasmid analysis.

Conjugation experiments were performed with the qnr-positive strains by the liquid mating-out assay, as described previously (36). Transconjugants were selected on tryptic soy agar plates containing sodium azide (100 μg/ml) and sulfamethoxazole (300 μg/ml) or ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Plasmid DNA extraction was performed by a rapid alkaline lysis procedure (34). Plasmid DNAs from the qnr-positive isolates and transconjugants or reference strains were subjected to electrophoresis in 0.7% agarose gels. Plasmid sizes were estimated as described previously (36).

Structure analysis of the qnrB- or aac(6′)-Ib-cr-containing plasmids.

To determine the genetic environment of aac(6′)-Ib-cr or the qnr genes, plasmid DNA was digested with EcoRI or HindIII, ligated to pUC18 (which is resistant to ampicillin; TaKaRa Bio, Otsu, Japan), and introduced into E. coli DH5α. Transformants were selected on tryptic soy agar plates containing ampicillin at 50 μg/ml and ciprofloxacin at 0.06 μg/ml. The sequencing of both DNA strands was carried out by primer walking. The DNA sequences and the deduced amino acid sequences were analyzed and compared by use of the NCBI BLAST program.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences in plasmid pHND2 containing qnrB6 and pHND1 harboring aac(6′)-Ib-cr have been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession numbers EU543271 and EU543272, respectively.

RESULTS

Prevalence of qnr, qepA, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes.

Among the total of 101 animal isolates, PMQR determinants were present in 35 (34.7%), with qnr, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA being detected alone or in combination in 8 (7.9%), 19 (18.8%), and 16 (15.8%) strains, respectively. The qnr genes included one qnrB4 gene, four qnrB6 genes, and three qnrS1 genes; qnrA was not detected. Five strains were positive for aac(6′)-Ib-cr, in addition to qepA, while one strain harbored both qnrB4 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr. qnrS1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA coexisted in a strain of E. coli isolated from partridge feces. Detailed information on these PMQR determinant-positive isolates is given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the qnrB-, qnrS-, qepA-, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr-positive Enterobacteriaceae strains

| Strain | Animal sourcea | Origin | Date of isolation | Ciprofloxacin MIC (μg/ml) | PMQR determinant | ESBL or AmpC β-lactamase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae C1 | PH | Cat feces | 4 Sept. 2006 | 8 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | NDb |

| K. pneumoniae C7 | PH | Cat sneeze | 5 Sept. 2006 | 8 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | ND |

| K. pneumoniae D10 | PH | Dog feces | 8 Sept. 2006 | 32 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qnrB4 | CTX-M-1G,c DHA-1 |

| K. pneumoniae D20 | PH | Dog vomitus | 15 Oct. 2006 | 32 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX-M-9G, DHA-1 |

| K. pneumoniae D24 | PH | Dog vomitus | 18 Oct. 2006 | 2 | qnrB6 | CTX-M-9G |

| K. pneumoniae D34 | PH | Dog sneeze | 22 Nov. 2006 | 32 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qepA | CTX-M-9G |

| K. pneumoniae D61′ | PH | Dog feces | 12 Mar. 2007 | 16 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX-M-9G |

| E. cloacae D32 | PH | Dog feces | 20 Nov. 2006 | 32 | qepA | CTX-M-9G |

| E. cloacae D73 | PH | Dog feces | 7 Apr. 2007 | 16 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX-M-9G |

| C. freundii D26 | PH | Dog feces | 2 Nov. 2006 | 4 | qnrB6 | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D3 | PH | Dog feces | 4 Sept. 2006 | 16 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qepA | CTX-M-1G, CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D23 | PH | Dog feces | 17 Oct. 2006 | 32 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qepA | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D40 | PH | Dog feces | 4 Dec. 2006 | 8 | qepA | CTX-M-1G, CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D47 | PH | Dog feces | 7 Dec. 2006 | 32 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qepA | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D55 | PH | Dog feces | 9 Dec. 2006 | 32 | qepA | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D57 | PH | Dog feces | 9 Mar. 2007 | 4 | qepA | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D60 | PH | Dog feces | 10 Mar. 2007 | 0.125 | qepA | CTX-M-1G, CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D61 | PH | Dog feces | 11 Mar. 2007 | 16 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D71 | PH | Dog feces | 5 Apr. 2007 | 64 | qepA | CTX-M-1G, CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D76 | PH | Dog sneeze | 9 Apr. 2007 | 16 | qepA | ND |

| E. coli D77 | PH | Dog feces | 4 Apr. 2007 | 4 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D81′ | PH | Dog feces | 2 May 2007 | 16 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX-M-9G, CMY-2 |

| E. coli D86 | PH | Dog feces | 7 May 2007 | 0.06 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli D87 | PH | Dog feces | 8 May 2007 | 16 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli Du6 | F1 | Duck feces | 21 Apr. 2007 | 2 | qnrB6 | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli Du27 | F1 | Duck feces | 21 Apr. 2007 | 32 | qepA | CTX-M-1G |

| E. coli Du19′ | F2 | Duck liver | 21 Apr. 2007 | 64 | qnrB6 | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli Du89 | F8 | Duck feces | 12 Sept. 2004 | 0.5 | qnrS1 | ND |

| E. coli P1 | F3 | Pig liver | 15 Apr. 2007 | 32 | qepA | ND |

| E. coli P17′ | F4 | Pig liver | 15 Apr. 2007 | 32 | qepA | CTX-M-1G |

| E. coli P498 | F6 | Pig feces | 27 Apr. 2005 | 64 | qnrS1 | ND |

| E. coli Chi197 | F5 | Chicken feces | 20 Jan. 2005 | 64 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | CTX-M-9G |

| E. coli PA09 | F7 | Partridge feces | 23 May 2005 | 64 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr | ND |

| E. coli PA11 | F7 | Partridge feces | 23 May 2005 | >128 | qnrS1, qepA, aac(6′)-Ib-cr | ND |

| E. coli PA14 | F7 | Partridge liver | 23 May 2005 | >128 | aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qepA | ND |

PH, pet hospital; F1 to F8, animal farms 1 to 8, respectively.

ND, not detected.

G, group.

Among the 36 isolates from companion animals, 24 (66.7%) strains carried at least one PMQR determinant; 3 (8.3%), 15 (41.7%), and 11 (30.6%) strains were positive for qnr genes, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA, respectively. Of the 65 isolates from food-producing animals, 11 (16.9%) contained one or more PMQR determinants; 5 (7.7%), 4 (6.2%), and 5 (7.7%) strains were positive for qnr genes, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA, respectively. The prevalence of PMQR determinants was significantly higher in companion animal strains (66.7%) than in food-producing strains (16.9%) (by the Pearson chi-square test, χ2 = 25.32; P < 0.001). The difference contributed to the higher prevalence of aac(6′)-Ib-cr and qepA in pet animals than in food-producing animals.

ERIC-PCR analysis indicated that most PMQR determinant-positive isolates were not clonally related. However, two K. pneumoniae isolates from cats (isolates C1 and C7) had indistinguishable ERIC patterns. Both carried aac(6′)-Ib-cr but contained different β-lactamase genes: blaTEM-1 in K. pneumoniae C1 but blaSHV-1 in K. pneumoniae C7. Three isolates from food producers, two E. coli strains from partridges (strains PA11 and PA14) and one E. coli strain from a chicken (strain Chi197), also showed indistinguishable ERIC-PCR patterns, although they carried different PMQR determinants.

Identification of ESBLs and plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases.

ESBLs and/or AmpC β-lactamases were detected in 68.3% (69/101) of all strains and in 74.3% (26/35) and 65.2% (43/66) of the PMQR determinant-positive and -negative strains, respectively (χ2 = 0.88; P = 0.348). Among the ESBLs detected in ESBL-positive strains, 53 belonged to the CTX-M-9 group, 13 belonged to the CTX-M-1 group, and 1 was an SHV type. Among the AmpC-positive strains, eight had the CMY-2 β-lactamase and two had the DHA-1 β-lactamase. Eleven strains had two ESBLs or both ESBL and AmpC enzymes. The ESBLs or AmpC β-lactamases present in 35 strains positive for PMQR determinants are listed in Table 1.

PMQR determinants were detected in 26 (37.7%) of 69 isolates positive for ESBLs and/or AmpC β-lactamases and in 9 (28.1%) of 32 ESBL- and/or AmpC-negative isolates (P = 0.348).

Conjugation experiments and plasmid analysis.

Quinolone resistance could be transferred by conjugation from four qnrB-positive strains and one qnrS1-positive strain. These transconjugants contained single plasmids of the same size as those in their respective donors. aac(6′)-Ib-cr and blaDHA-1 were cotransferred with qnrB4 carried by plasmid pHND1 from donor strain K. pneumoniae D10, which was isolated from dog feces. blaCTX-M-9G was cotransferred with qnrB6 carried by plasmid pHND2 from K. pneumoniae D24, but blaCTX-M-9G was not detected on the transfer of qnrB6-carrying plasmid pHND3 from C. freundii D26 or qnrB6-carrying plasmid pHNDU1 from E. coli Du19′. A donor strain of E. coli PA11 isolated from a partridge carried three PMQR determinants (qnrS1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA), but a transconjugant carrying only qnrS1 was obtained, indicating that qnrS1 was located on a plasmid separate from plasmids carrying the other two determinants. The sizes of the plasmids harboring the qnr genes were between 70 kb and >180 kb. The ciprofloxacin MICs of four qnrB transconjugants and one qnrS1 transconjugant ranged from 0.06 to 0.5 μg/ml, an increase of 8- to 64-fold over that of the recipient strain (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of donor strains and E. coli J53 transconjugants

| Straina | Plasmid (size [kb]) | PMQR determinant | ESBL or AmpC β-lactamase | MIC (μg/ml)b

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAL | CIP | LEV | AMP | CTF | CTX | CAZ | CEQ | GEN | AMK | CHL | SMZ | TMP | ||||

| E. coli J53 | NAc | NA | NA | 4 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 8 | 16 | 0.25 |

| K. pneumoniae D10 | MPd | qnrB4 aac(6′)- Ib-cr | CTX-M-1G, DHA-1 | >128 | 32 | 16 | >128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 64 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >256 | >256 |

| Tc-D10 | pHND1 (>180) | qnrB4 aac(6′)-Ib-cr | DHA-1 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.25 | >128 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.06 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >256 | >256 |

| K. pneumoniae D24 | MP | qnrB6 | CTX-M-9G | 64 | 2 | 1 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 2 | 64 | 128 | 2 | >128 | >256 | >256 |

| Tc-D24 | pHND2 (75) | qnrB6 | CTX-M-9G | 16 | 0.5 | 0.25 | >128 | 64 | 32 | 1 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | >128 | >256 | >256 |

| C. freundii D26 | MP | qnrB6 | CTX-M-9G | 128 | 4 | 2 | >128 | 128 | 64 | 1 | 64 | >128 | >128 | 64 | >256 | >256 |

| Tc-D26 | pHND3 (145) | qnrB6 | NDe | 4 | 0.06 | 0.06 | >128 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 16 | 1 | 8 | 4 | >256 |

| E. coli Du19′ | MP | qnrB6 | CTX-M-9G | >128 | 16 | 16 | >128 | 128 | 128 | 16 | 32 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >256 | >256 |

| Tc-Du19′ | pHNDU1 (70) | qnrB6 | ND | 64 | 0.5 | 2 | 64 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 128 | 0.5 |

| E. coli PA11 | MP | qnrS1, qepA, aac(6′)-Ib-cr | ND | >128 | >128 | 128 | >256 | >128 | 16 | 32 | 64 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 |

| Tc-PA11 | pHNPA1 (85) | qnrS1 | ND | 32 | 0.5 | 1 | >256 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 16 | >256 | >256 |

Tc-D10, Tc-D24, Tc-D26, Tc-Du19′, and Tc-PA11, transconjugants of K. pneumoniae D10, K. pneumoniae D24, C. freundii D26, E. coli Du19′, and E. coli PA11, respectively.

CIP, ciprofloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin; NAL, nalidixic acid; AMP, ampicillin; CTF, ceftiofur; CTX, cefotaxime; CAZ, ceftazidime; CEQ, cefquinome; GEN, gentamicin; AMK, amikacin; CHL, chloramphenicol; SMZ, sulfamethoxazole; TMP, trimethoprim. Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin MICs were determined by Etest.

NA, not applicable.

MP, multiple plasmids.

ND, not detected.

Genetic structures adjacent to qnrB6 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes.

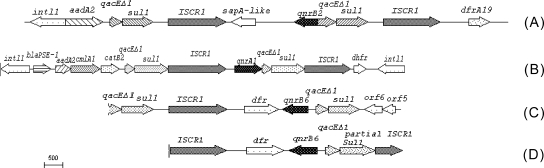

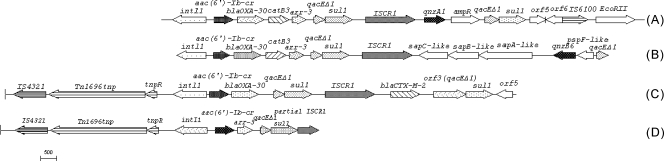

DNA from qnrB6-carrying plasmids pHND2, pHND3, and pHNDU1 was digested with EcoRI and cloned into pUC18 by selection for ampicillin and ciprofloxacin resistance. Recombinant plasmids from all three donors contained an identical 5.5-kb sequence in which qnrB6 was flanked by two copies of ISCR1 and an intervening dfr gene downstream and sul1 and qacEΔ1 upstream (Fig. 1). An EcoRI-digested fragment of about 10.0 kb from plasmid pHND1 carrying aac(6′)-Ib-cr was also cloned and sequenced. aac(6′)-Ib-cr was located in a class 1 integron cassette, following intI1, with arr-3, sul1, and qacEΔ1 being located downstream (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of regions flanking qnrB6 in pHND2 and in three other plasmids carrying qnrB2, qnrB6, and qnrA1, respectively. (A) Salmonella enterica plasmid (GenBank accession no. AM234698); (B) pMG252 (GenBank accession no. DQ831140); (C) K. pneumoniae plasmid (GenBank accession no. EF667294); (D) pHND2 (GenBank accession no. EU543271).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of regions flanking aac(6′)-Ib-cr in pHND1 and in other three plasmids. (A) pHSH2 (GenBank accession no. AY259086); (B) K. pneumoniae plasmid (GenBank accession no. EF636461); (C) pAS1 (GenBank accession no. DQ310703); (D) pHND1 (GenBank accession no. EU543272).

DISCUSSION

PMQR determinants were highly prevalent (34.7%) in the set of ceftiofur-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from companion and food-producing animals from China evaluated in this study. In these strains, qepA and aac(6′)-Ib-cr were more common than qnr determinants. Prior to our study, only a few investigations evaluated animal strains for PMQR determinants. The qnrS gene was identified in a strain of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis isolated from a chicken in Germany (15) and in three strains of Salmonella enterica serovar Virchow obtained from chickens in Turkey (2). qnrB, qnrS, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr were found in 10 strains of gram-negative bacteria isolates from zoo animals in Japan (1) and recently in E. coli isolates of food-producing animals from China (18, 42). Interestingly, as shown in this study, qnrA has not been detected in any reported animal isolates. qepA, a newly identified PMQR determinant, often seems to be carried along with the rmtB gene, which encodes a 16S rRNA methyltransferase (18, 27, 40). A recent study showed that the prevalence of qepA was low (0.3%) in E. coli clinical isolates collected from 140 Japanese hospitals between 2002 and 2006 (39). We previously showed that qepA is common in rmtB-positive E. coli isolates from pigs (18), and the present study also revealed a very high prevalence of qepA (15.8%) in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from food-producing and companion animals. To the best of our knowledge, qepA has been identified only in E. coli strains from Japan (39, 40), Belgium (27), and China (18). Our study extended the set of strains carrying qepA to K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae (Table 1).

This study found that the prevalence of PMQR determinants was significantly higher in isolates from companion animals (66.7%) than isolates from food-producing animals (16.9%). This finding may be related to the extensive use of broad-spectrum agents, including antimicrobial preparations also used in human medicine, in small-animal veterinary practice (9). Many fewer data on the public health impact of antimicrobial usage in companion animals are available. In Denmark, a comparatively small number of dogs and cats consumed approximately the same amount of fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins as was consumed annually by the much larger population of food-producing animals (9). Thus, bacteria in pets are more likely to be subjected to rather high levels of antibiotic selection pressure, which may in turn explain the high rate of detection of these PMQR determinants. Since cats and dogs are in close contact with humans, the transfer of bacteria between animals and humans is also possible. The prudent use of antibiotics in companion animals is desirable.

The levels of production of ESBLs and/or AmpC β-lactamases were high (68.3%) in the ceftiofur-resistant Enterobacteriaceae strains evaluated in this study, with the main genotypes identified being the blaCTX-M-9 group, the blaCTX-M-1 group, and blaCMY-2. Among the five transferable plasmids obtained during the conjugation experiment in this study, two plasmids harbored a qnr gene and an ESBL or AmpC gene simultaneously: qnrB4 and blaDHA-1 in pHND1 and qnrB6 and blaCTX-M-9 in pHND2. The linkage of the DHA-1 β-lactamase and QnrB4 has been described in several recent reports (23, 25, 38). Our previous study found that blaDHA-1 is located downstream of qnrB4 and is separated by psp operons and orf1 (10).

qnrB6 was flanked by two copies of ISCR1, with sul1 and qacEΔ1 located upstream. This organization is similar to that seen in plasmid pMG252 carrying qnrA1 (30), in a Salmonella enterica serovar Keurmassar plasmid (GenBank accession no. AM234698) carrying qnrB2 (7), and in a K. pneumoniae plasmid carrying qnrB6 (GenBank accession no. EF667294); but there are three differences among these four plasmids. The first is that orf5 and orf6 replaced one copy of ISCR1 upstream of qnrB6 in the K. pneumoniae plasmid. The second is that sul1 and qacEΔ1 are located upstream of qnrB6 or qnrB2 in plasmid pHND2, the K. pneumoniae plasmid and the S. enterica serovar Keurmassar plasmid but they are downstream of qnrA1 in pMG252. The third is that the orientation of qnrB6 and qnrB2 is reversed with respect to the location of ISCR1 in pHND2, the K. pneumoniae plasmid, and the S. enterica serovar Keurmassar plasmid; but qnrA1 has the same orientation as ISCR1 in pMG252. Just as in In37 (36), in a qnrB6-bearing K. pneumoniae plasmid (GenBank accession no. EF636461) (29) and Vibrio cholerae plasmid pAS1 (GenBank accession no. DQ310703) (33), aac(6′)-Ib-cr was located in the variable region of a class 1 integron and was always found in the first position of the gene cassettes directly following intl1.

In summary, we have found a high prevalence of PMQR determinants in ceftiofur-resistant isolates from companion and food-producing animals in China. qepA and aac(6′)-Ib-cr were more prevalent in companion animal isolates than in food-producing animal isolates. The presence of these genes in bacteria isolated from pets and food-producing animals is an important fact that constitutes a public health concern. The prudent use of antimicrobial agents is thus necessary in veterinary medicine as well as in human medicine to minimize the spread of these resistance genes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 2005CB0523101 (to M.W.) from the National Basic Research Program of China from the Ministry of Science and Technology, China; grant 2006 BAK02A03-5 (to J.L.) from the National Science and Technology Pillar Program for Food Safety Key Technology Project during the 11th Five-Year Plan of China; and grants 30572229 (to M.W.), 30500373 (to J.L.), 30671584 (to Z.Z.), and U0631006 (to J.L. and Z.Z.) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

We thank George A. Jacoby, and David C. Hooper for providing reference strains E. coli J53Azir, E. coli V517, E. coli R1, E. coli Plac, E. coli R27, UAB1, and E. coli pMG298 and George A. Jacoby for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, A. M., Y. Motoi, M. Sato, A. Maruyama, H. Watanabe, Y. Fukumoto, and T. Shimamoto. 2007. Zoo animals as a reservoir of gram-negative bacteria harboring integrons and antimicrobial resistance genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:6686-6690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avsaroglu, M. D., R. Helmuth, E. Junker, S. Hertwig, A. Schroeter, M. Akcelik, F. Bozoglu, and B. Guerra. 2007. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance conferred by qnrS1 in Salmonella enterica serovar Virchow isolated from Turkish food of avian origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:1146-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinas, L., M. A. Moreno, M. Zarazaga, C. Perrero, Y. Saenz, M. Garcia, L. Dominguez, and C. Torres. 2003. Detection of CMY-2, CTX-M-14, and SHV-12 β-lactamases in Escherichia coli fecal sample isolates from healthy chickens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2056-2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2002. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals. Approved standard, 2nd ed. Document M31-A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2005. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 15th informational supplement. M100-S15. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 6.Fey, P. D., T. J. Safranek, M. E. Rupp, E. F. Dunne, E. Ribot, P.C. Iwen, P. A. Bradford, F. J. Angulo, and S. H. Hinrichs. 2000. Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella infection acquired by a child from cattle. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1242-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garnier, F., N. Raked, A. Gassama, F. Denis, and M. C. Ploy. 2006. Genetic environment of quinolone resistance gene qnrB2 in a complex sul1-type integron in the newly described Salmonella enterica serovar Keurmassar. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3200-3202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hata, M., M. Suzuki, M. Matsumoto, M. Takahashi, K. Sato, S. Ibe, and K. Sakae. 2005. Cloning of a novel gene for quinolone resistance from a transferable plasmid in Shigella flexneri 2b. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:801-803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heuer, O. E., V. F. Jensen, and A. M. Hammerum. 2005. Antimicrobial drug consumption in companion animals. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:344-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu, F. P., X. G. Xu, D. M. Zhu, and M.G. Wang. 2008. Coexistence of qnrB4 and qnrS1 in a clinical strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 29:320-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacoby, G., V. Cattoir, D. Hooper, L. Martínez-Martínez, P. Nordmann, A. Pascual, L. Poirel, and M. Wang. 2008. qnr gene nomenclature. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2297-2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacoby, G. A., and P. Han. 1996. Detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:908-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacoby, G. A., K. E. Walsh, D. M. Mills, V. J. Walker, H. Oh, A. Robicsek, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. qnrB, another plasmid-mediated gene for quinolone resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1178-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang, Y., Z. Zhou, Y. Qian, Z. Wei, Y. Yu, S. Hu, and L. Li. 2008. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants qnr and aac(6′)-Ib-cr in extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:1003-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kehrenberg, C., S. Friederichs, A. D. Jong, G. B. Michael, and S. Schwarz. 2006. Identification of the plasmid-borne quinolone resistance gene qnrS in Salmonella enteica serovar Infantis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:18-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, K., S. G. Hong, Y. J. Park, H. S. Lee, W. Song, J. Jeong, D. Yong, and Y. Chong. 2005. Evaluation of phenotypic screening methods for detecting plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase-producing isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 53:319-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, X. Z., M. Mehrotra, S. Ghimire, and L. Adewoye. 2007. β-Lactam resistance and β-lactamases in bacteria of animal origin. Vet. Microbiol. 121:197-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, J. H., Y. T. Deng, Z. L. Zeng, J. H. Gao, L. Chen, Y. Arakawa, and Z. L. Chen. 2008. Co-prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants QepA, Qnr, and AAC(6′)-Ib-cr among 16S rRNA methylase RmtB-producing Escherichia coli isolates from pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2992-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, J. H., S. Y. Wei, J. Y. Ma, Z. L. Zeng, D. H. Lu, G. X. Yang, and Z. L. Chen. 2007. Detection and characterization of CTX-M and CMY-2 β-lactamases among Escherichia coli isolates from farm animals in Guangdong Province of China. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29:576-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manian, F. A. 2003. Asymptomatic nasal carriage of mupirocin-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a pet dog associated with MRSA infection in household contacts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:e26-e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Martinez, L., A. Pascual, and G. A. Jacoby. 1998. Quinolone resistance from a transferable plasmid. Lancet 351:797-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mølbak, K., D. L. Baggesen, F. M. Aarestrup, J. M. Ebbesen, J. Engberg, K. Frydendahl, P. Gerner-Smidt, A. M. Petersen, and H. C. Wegener. 1999. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant, quinolone-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1420-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pai, H., M. R. Seo, and T. Y. Choi. 2007. Association of qnrB determinants and production of extended-spectrum-β-lactamases or plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:366-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park, C. H., A. Robicsek, G. A. Jacoby, D. Sahm, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. Prevalence in the United States of aac(6′)-Ib-cr encoding a ciprofloxacin-modifying enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3953-3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park, Y. J., J. K. Yu, S. Lee, E. J. Oh, and G. J. Woo. 2007. Prevalence and diversity of qnr alleles in AmpC-producing Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter aerogenes, Citrobacter freundii and Serratia marcescens: a multicentre study from Korea. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:868-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Perez, F. J., and N. D. Hanson. 2002. Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase genes in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2153-2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perichon, B., P. Courvalin, and M. Galimand. 2007. Transferable resistance to aminoglycosides by methylation of G1405 in 16S rRNA and to hydrophilic fluoroquinolones by QepA-mediated efflux in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2464-2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirel, L., C. Leviandier, and P. Nordmann. 2006. Prevalence and genetic analysis of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants QnrA and QnrS in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from a French university hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3992-3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quiroga, M. P., P. Andres, A. Petroni, A. J. Soler, Bistué, L. Guerriero, L. J. Vargas, A. Zorreguieta, M. Tokumoto, C. Quiroga, M. E. Tolmasky, M. Galas, and D. Centrón. 2007. Complex class 1 integrons with diverse variable regions, including aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and a novel allele, qnrB10, associated with ISCR1 in clinical enterobacterial isolates from Argentina. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4466-4470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robicsek, A., G. A. Jacoby, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. The worldwide emergence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6:629-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robicsek, A., J. Strahilevitz, D. F. Sahm, G. A. Jacoby, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. qnr prevalence in ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2872-2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robicsek, A., J. Strahilevitz, G. A. Jacoby, M. Macielag, D. Abbanat, C. H. Park, K. Bush, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. Fluoroquinolone-modifying enzyme: a new adaptation of a common aminoglycoside acetyltransferase. Nat. Med. 12:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soler Bistué, A. J., F. A. Martín, A. Petroni, D. Faccone, M. Galas, M. E. Tolmasky, and A. Zorreguieta. 2006. Vibrio cholerae InV117, a class 1 integron harboring aac(6′)-Ib and blaCTX-M-2, is linked to transposition genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1903-1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi, S., and Y. Nagano. 1984. Rapid procedure for isolation of plasmid DNA and application to epidemiological analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:608-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Versalovic, J., T. Koeuth, and J. R. Lupski. 1991. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6823-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, M., J. H. Tran, G. A. Jacoby, Y. Y. Zhang, F. Wang, and D. C. Hooper. 2003. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Shanghai, China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2242-2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu, J. J., W. C. Ko, S. H. Tsai, and J. J. Yan. 2007. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants QnrA, QnrB, and QnrS among clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae in a Taiwanese hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1223-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu, J. J., W. C. Ko, S. H. Tsai, and J. J. Yan. 2008. Prevalence of Qnr determinants among bloodstream isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Taiwanese hospital 1999-2005. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 10:1093-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamane, K., J. Wachino, S. Suzuki, and Y. Arakawa. 2008. Plasmid-mediated qepA gene among Escherichia coli clinical isolates from Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1564-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamane, K., J. I. Wachino, S. Suzuki, K. Kimura, H. K. Shibata, K. Shibayama, T. Konda, and Y. Arakawa. 2007. New plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone efflux pump, QepA, found in an Escherichia coli clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3354-3360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan, J. J., C. Y. Hong, W. C. Ko, Y. J. Chen, S. H. Tsai, C. L. Chuang, and J. J. Wu. 2004. Dissemination of blaCMY-2 among Escherichia coli isolates from food animals, retail ground meats, and humans in southern Taiwan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1353-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yue, L., H. X. Jiang, X. P. Liao, J. H. Liu, S. J. Li, X. Y. Chen, C. X. Chen, D. H. Lü, and Y. H. Liu. 2008. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance qnr genes in poultry and swine clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Vet. Microbiol. 132:414-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]