Abstract

A vaccine for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is desperately needed to control the AIDS pandemic. To address this problem, we constructed single-cycle simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) pseudotyped with the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus and expressing different levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) as a potential vaccine strategy. We previously showed that IFN-γ expression by pseudotyped SIVs does not alter viral single-cycle infectivity. T cells primed with dendritic cells transduced by pseudotyped SIVs expressing high levels of IFN-γ had stronger T-cell responses than those primed with dendritic cells transduced by constructs lacking IFN-γ. In the present study, we tested the immunogenicities of these pseudotyped SIVs in a rat model. The construct expressing low levels of rat IFN-γ (dSIVLRγ) induced higher levels of cell-mediated and humoral immune responses than the construct lacking IFN-γ (dSIVR). Rats vaccinated with dSIVLRγ also had lower viral loads than those vaccinated with dSIVR when inoculated with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing SIV Gag-Pol as a surrogate challenge. The construct expressing high levels of IFN-γ (dSIVHRγ) did not further enhance immunity and was less protective than dSIVLRγ. In conclusion, the data indicated that IFN-γ functioned as an adjuvant to augment antigen-specific immune responses in a dose- and cell type-related manner in vivo. Thus, fine-tuning of the cytokine expression appears to be essential in designing vaccine vectors expressing adjuvant genes such as the gene for IFN-γ. Furthermore, we provide evidence of the utility of the rat model to evaluate the immunogenicities of single-cycle HIV/SIV recombinant vaccines before initiating studies with nonhuman primate models.

We previously constructed vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G)-pseudotyped single-cycle simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) expressing two different levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and we showed that IFN-γ acts as an adjuvant to augment T-cell priming by antigen-presenting cells in an in vitro model (35). We have now proceeded to an in vivo model to further assess the levels of immunogenicity and efficacy of these constructs. Due to the fact that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/SIV replication is subject to a number of species-specific restrictions, efforts to develop murine models for HIV/SIV infection and disease have been unsuccessful (3). In contrast, numerous studies have shown that the only significant block to HIV replication in many rat cell lines is at the level of virus entry (3, 22, 38). Transgenic rats carrying the HIV type 1 (HIV-1) provirus develop pathological and immunological dysfunction similar to that of humans infected with HIV-1 (38). HIV long terminal repeat activity in some rat cell lines and primary rat lymphocytes, macrophages, and microglias was found previously to be relatively high compared to that in murine cells (22, 52), although it is not equivalent to that in primate cells. Unlike murine cells, most rat cells other than primary rat T lymphocytes do not show any evidence indicating a defect in Rev activity (22, 38). Moreover, an analysis of primary rat macrophages and microglias infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV demonstrated previously that these cells are highly permissive of viral replication (21, 22). Therefore, the rat appears to be a practical small-animal model for the initial evaluation of our vaccine strategy before trials with nonhuman primates and was chosen for the present in vivo study.

We found that rats immunized with pseudotyped single-cycle SIVs expressing IFN-γ developed stronger proliferative and humoral immune responses to viral antigens than those immunized with a construct lacking IFN-γ. The enhancement of immune responses appeared to be dose dependent, since the construct expressing a low level of IFN-γ (designated SIVΔERγΔNgfp/G and abbreviated dSIVLRγ) resulted in enhanced cell-mediated immune (CMI) responses and decreased postchallenge viral loads compared to the construct expressing high levels of IFN-γ (designated SIVΔEΔNRγ/G and abbreviated dSIVHRγ). Thus, fine-tuning the levels of cytokine expression appears to be essential in designing vaccine vectors expressing adjuvant genes such as the gene for IFN-γ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and media.

HeLa, HeLa S3, and embryonic kidney (293T) cells, as well as African green monkey kidney (BS-C-1) and rat fibroblast (Rat-2) cells, were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin), referred to hereinafter as complete DMEM. MAGI-CCR5 cells (5) (catalogue no. 3522) were obtained from Julie Overbaugh through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program and were propagated in complete DMEM supplemented with 0.25 μg/ml Fungizone, 0.2 mg/ml G418 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.1 mg/ml hygromycin B, and 1 μg/ml puromycin. The WR strain of vaccinia virus (VV) and the recombinant VV expressing SIV Gag-Pol (vSIVgag-pol) were propagated in HeLa S3 cells, and virus titers were determined using BS-C-1 cells. Serum-free UltraCULTURE medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and antibiotics was used to prepare viral stocks. All cultures of rat splenocytes were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, antibiotics, and 50 μM 2-β-mercaptoethanol, referred to hereinafter as complete RPMI 1640 medium.

Animals.

Groups of Fischer 344 (F344) rats (6- to 7-week-old females) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). All animals were maintained in a specific-pathogen-free facility according to NIH guidelines. Animal care protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Administrative Advisory Committee at the University of California, Davis.

Construction of pseudotyped SIVs.

The plasmids were constructed as described previously (35). The rat IFN-γ gene, which replaced the macaque IFN-γ gene, was amplified from plasmid pRγcDNAII (50) by standard PCR techniques using Pfu polymerase and primers 5′-ATAATCCGGACGCCACCATGAGTGCTACA-3′ and 5′-TCTACCTCCGGATCAGC ACCGACTCC-3′ or 5′-ATAACCCGGGCGCCACCATGAGTGCTACA-3′ and 5′-AATTATCGGCCGTCAGCACCGACTCC-3′ (engineered BspE1, XmaI, and EagI restriction endonuclease sites are underlined). The pseudotyped particles were prepared and titers were determined as described previously (35). To prepare high-titer stocks, viral particles were concentrated with Centricon Plus-80 units (Millipore, Bedford, MA) by centrifugation at 250 × g for 2.5 h in an RT6000B centrifuge (Sorvall, Asheville, NC) (39).

Construction of vSIVgag-pol.

SIVmac239 gag-pol was PCR amplified from pSIVΔnef (18) with primers 5′-TAATAGCGGCCGCCATGGGCGTGAGAAAC-3′ and 5′-AATTTACGGCCGATGAGGCTATGCCACC-3′ (engineered EagI restriction endonuclease sites are underlined). The nucleotide sequence derived by PCR was confirmed by sequencing analysis. The gag-pol gene was inserted at the EagI site of p2B8Rgpt (28, 50) under the control of one of two back-to-back strong synthetic VV promoters (dsP) that are active in both early and late stages of infection. Recombinant VV was generated by standard techniques using cationic liposome-mediated transfection of BS-C-1 cell monolayers, infected 2 h earlier with VV at 0.05 PFU per cell, with the transfer vector p2B8RgptGP. Recombinant gpt-positive VVs were plaque purified from transfection supernatants on BS-C-1 cells by using gpt selection medium (25-μg/ml mycophenolic acid, 250-μg/ml xanthine, and 15-μg/ml hypoxanthine) (11). Blue plaques were visualized with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-d-galactopyranoside) to detect the lacZ marker gene. The expression of the lacZ gene by the final plaque-purified vSIVgag-pol was tested by cytochemical staining of infected cell monolayers as described previously (31). High-titer stocks were generated by infecting HeLa S3 cells with vSIVgag-pol at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. Infected cells were harvested 3 days postinfection by centrifugation at 200 × g for 10 min. Cells were then lysed by freeze-thawing, sonication, and trypsinization. Finally, cell lysates were clarified to remove contaminating cell debris by a second round of sonication and centrifugation at 200 × g for 5 min. The expression of Gag and Pol was confirmed by Western blotting and a reverse transcriptase (RT) assay. RT activity in the viral stocks was measured with an RT assay kit by evaluating the incorporation of digoxigenin- and biotin-labeled dUTP into DNA as described in the protocol of the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics, Germany).

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western immunoblotting.

To detect p27 Gag, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis were performed using a 4 to 20% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) loaded with 10 μl of viral stock per well. Samples were electrotransferred onto an Immobilon-P membrane (Amersham International, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). The membrane was blocked by incubation in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution containing 0.1% Tween 20. p27 Gag was detected after incubation with an anti-p27 monoclonal antibody (19) diluted 1:1,000 and subsequent incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) diluted 1:1,000 in PBS-0.1% Tween 20. The anti-SIV p27 antibody (SIVmac p27 monoclonal antibody 55-2F12; catalogue no. 1610) was obtained from Niels Pedersen through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. Finally, the membrane was incubated for 15 to 30 min in BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate)-nitroblue tetrazolium solution (Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) for the detection of binding to specific antigens.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Rat-2 cells were plated onto chamber slides (5 × 103 cells/chamber) the day before transduction and then were transduced at an MOI of 0.5 with different viral particles for 3 h. Cells were then washed thoroughly and incubated for 0, 2, 4, 7, or 10 days in complete DMEM. Supernatants were harvested at different time points to measure rat IFN-γ production by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the protocol of the assay kit manufacturer (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Gag concentrations in 2-day culture supernatants were determined using the p27 ELISA according to the protocol of the assay kit manufacturer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) to measure viral protein production during single-cycle infection. Cells in each chamber were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.04% Triton X-100. PBS containing 5% goat serum was used as a blocking solution. Cells were then stained for intracellular Gag by using a mouse anti-p27 Gag monoclonal antibody (Advanced Bioscience Laboratory, Kensington, MD) followed by Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) diluted in PBS-5% goat serum. Slides were mounted with mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to counterstain nuclei. The total number of cells in each field was determined by counting more than 500 consecutive nucleated cells, identified by DAPI staining, under an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), and the number of cytoplasmic red fluorescence-stained cells was recorded to calculate the percentage of Gag-positive cells. Three fields of cells for each sample preparation were counted.

Immunization protocol.

Groups of F344 rats were immunized at 7 to 8 weeks of age. Immunization was carried out by intradermal injection with 106 transducing units (TU) of pseudotyped SIVs in a final volume of 100 μl of sterile PBS or with 100 μl of the mock control supernatant diluted in PBS into a shaved area of the flank. On day 14, the animals were boosted intradermally with the same regimen. On day 28, the animals were sacrificed for immunoassays.

Humoral studies.

Groups of rats were bled, and serum samples were measured individually. To detect antigen-specific antibodies by ELISA, 96-well MaxiSorp microtiter plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight with 100 μl of recombinant SIVmac251 p27 Gag produced in an Escherichia coli expression system (ImmunoDiagnostics, Woburn, MA) and diluted 1:1,000 in PBS or with 100 μl of SIVmac251 viral lysate (ZeptoMetrix, Buffalo, NY) diluted 1:1,000 in PBS. These dilutions were determined to give the highest readings with positive control samples and the lowest background readings with naïve serum samples. After overnight incubation at 4°C, plates were washed and blocked for 2 h at 37°C with 4% bovine serum albumin in PBS. The plates were then incubated for 3 h at 37°C with fourfold serial dilutions of serum from each animal. Antibody binding was detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rat immunoglobulin G (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) at a 1/10,000 dilution. Finally, optical densities (OD) at 450 nm were measured with a Labsystems Multiskan Ascent microplate reader with a reference wavelength of 620 nm. Sample dilutions were considered positive if the OD for that dilution was at least twofold higher than the OD for the mock control serum samples at the same dilution. Titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of samples scoring positive.

Proliferation assays.

Lymphocyte proliferation assays were performed as described previously (28). Two weeks after the final vaccination, the rats in each group were sacrificed. The spleens were removed, and the tissue was disrupted by compression through a cell strainer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Splenocytes (105 in 100 μl of complete RPMI 1640 medium) were seeded in triplicate onto 96-well plates containing 0, 1.25, 5, or 12.5 μg/ml of baculovirus-expressed p55 Gag (1). The mitogen concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma) at 5 μg/ml served as a positive control, and vesicular stomatitis virus nucleoprotein (VSV-N) at 1.25 μg/ml was used as an additional nonspecific stimulation control. Splenocytes were incubated for 6 days at 37°C. On day 6, 1.0 μCi of [3H]thymidine per 50 μl per well was added, and cells were incubated for 18 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested to assess the incorporation of radioactivity, and data were expressed as the stimulation indices (SI), which were calculated as the ratio of the counts per minute in the presence and absence of antigen. An SI of greater than 3 was considered to indicate positivity (12).

Analysis of antigen-specific cytokine production.

To further characterize the type of immune response induced in vaccinated rats, splenocytes were cultured for 3 days (106 cells/ml) in the presence of baculovirus-expressed SIV p55 Gag (1) at a final concentration of 1.25 or 5 μg/ml or VSV-N at 1.25 μg/ml. Culture supernatants were collected, and the concentrations of IFN-γ, interleukin-2 (IL-2), and IL-4 were measured with commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems).

ELISPOT assay.

Splenocytes were collected as described above, and samples were depleted of CD4+ T cells by magnetic cell sorting with an autoMACS system from Miltenyi Biotech (Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol (44). The purity of depletion was greater than 97% as determined by flow cytometric analysis. Ninety-six-well plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA) were coated overnight at 4°C with 6 μg/ml of mouse anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). The plates were washed and blocked with complete RPMI 1640 medium. Aliquots of CD4+-T-cell-depleted splenocytes (105 cells/50 μl/well) were transferred onto the plates for 24 h of incubation in the presence of overlapping 15-mer peptides spanning SIV Gag (with 11-amino-acid overlaps) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml of each peptide. These peptides were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. Negative controls were medium alone and a human T-lymphotropic virus Env peptide pool (obtained from Renu Lal through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) (43) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml of each peptide. Negative controls were also supplemented with dimethyl sulfoxide to a final concentration equivalent to that in the SIV peptide pools. ConA (5 μg/ml; Sigma) served as a positive control. The plates were washed and incubated for 1.5 h with 2 μg/ml of biotin-conjugated anti-IFN-γ polyclonal antibody (eBioscience). The wells were subsequently incubated for 1 h with 100 μl of 1:1,000-diluted streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Mabtech, Mariemont, OH), followed by BCIP-nitroblue tetrazolium (Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) as a substrate. Spot-forming cells (SFC) were counted by using a KS enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) compact system (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The mean number of SFC in duplicate wells was calculated. Wells were scored positive if the number of SFC per well was greater than the average for the medium-alone wells + 2 standard deviations (34). Results were normalized as the number of SFC per 106 cells.

Challenge studies.

Groups of female F344 rats were immunized twice as described above. Two weeks after the final immunization, they were inoculated intraperitoneally with 5 ×107 PFU of vSIVgag-pol in a final volume of 250 μl of sterile PBS. Ovaries were removed 3 days postchallenge, weighed, homogenized, and resuspended in DMEM at a concentration of 10% (wt/vol). The tissues were then lysed by freeze-thawing and trypsinization. Viral titers were determined by a plaque assay on BS-C-1 cell monolayers and defined as the numbers of PFU per organ (28).

Data analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software program Prism, version 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Data were expressed as the means ± the standard errors of the means (SEM), and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant. The comparative analysis of animal groups subjected to different vaccine regimens was performed by using the Kruskal-Wallis H test, followed by Dunn's multiple-comparison test, or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison test.

RESULTS

Construction of IFN-γ-expressing pseudotyped single-cycle SIVs.

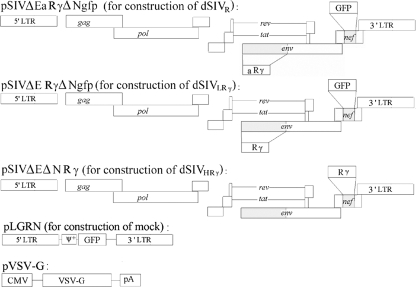

We previously constructed and characterized VSV-G-pseudotyped SIVs expressing IFN-γ (35). As an initial study of the efficacy of this strategy in vivo, inbred rats were used due to their low cost, small size, and relatively well-characterized immune system. The macaque IFN-γ gene was replaced with the rat IFN-γ gene due to the species specificity of IFN-γ (Fig. 1). Viral titers were determined by two quantification approaches and expressed as numbers of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-forming units per milliliter and numbers of TU per milliliter (Table 1). As expected, the titers obtained by the two methods were equivalent, and the latter titers were used in later experiments to determine the doses given as immunogens.

FIG. 1.

Strategy for generating pseudotyped single-cycle SIVs expressing IFN-γ and a mock control. Deletions in full-length SIVmac239 proviral DNA are shown as shaded regions, and the inserted rat IFN-γ (Rγ) and GFP genes are shown as open boxes. An IFN-γ gene was also inserted in the antisense orientation and is designated aRγ. Pseudotyped SIVs or the mock control was generated by the transient cotransfection of 293T cells with pVSV-G and a plasmid encoding the defective proviral DNA or pLGRN. LTR, long terminal repeat; CMV, cytomegalovirus; pA, polyadenylation signal.

TABLE 1.

Titers of VSV-G-pseudotyped SIVs

| Viral particle type | Designation | No. of GFU/mla | No. of TU/mlb |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIVΔEaRγΔNgfp/G | dSIVR | 2.0 × 107 | 1.6 × 107 |

| SIVΔERγΔNgfp/G | dSIVLRγ | 1.4 × 107 | 1.2 × 107 |

| SIVΔEΔNRγ/G | dSIVHRγ | NAc | 6.4 × 107 |

GFP-forming units (GFU) per milliliter of viral stocks as measured on HeLa cells.

TU per milliliter of viral stocks as measured on MAGI-CCR5 cells.

NA, not applicable.

Kinetics and levels of Gag expression were not significantly altered by different levels of IFN-γ.

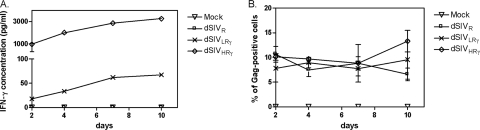

The expression of IFN-γ from different regions of the SIV genome resulted in different levels of the cytokine. Since this variation may affect the levels of gag gene expression or the turnover of target cells, we measured the expression of Gag by intracellular staining in parallel with the quantification of IFN-γ in the cell culture supernatant over time. In a pilot study, we compared cell staining patterns at MOIs of 5, 1, and 0.5 and observed a high level of cell death in dSIVHRγ-transduced cells only at an MOI of 5 (data not shown). Since the level of transduction of cells in vivo is unlikely to be as high as an MOI of 5, we performed subsequent experiments using an MOI of 0.5. As shown in Fig. 2A, IFN-γ was expressed at significantly higher levels from the nef site (dSIVHRγ) than from the env site (dSIVLRγ) over the 10-day period of measurement, while the expression of the IFN-γ gene inserted in the antisense orientation (dSIVR) was not detectable. No IFN-γ could be detected at day 0 in any group of cells (data not shown). The transduction of Rat-2 cells with the different viral particles did not result in any significant difference in the frequency of Gag-positive cells over the 10-day time period (Fig. 2B). p27 Gag was detected at day 0 in 100% of cells, presumably by the staining of internalized viral particles (data not shown). The staining of cells for Gag expression resulted in bright cytoplasmic fluorescence beginning on day 2 posttransduction. We also measured p27 Gag concentrations in supernatants of transduced cells to compare late gene expression patterns among the different constructs in HeLa cells (which are not responsive to rat IFN-γ) and Rat-2 cells (which are responsive to rat IFN-γ). Levels of p27 Gag in the supernatants of dSIVR-, dSIVLRγ-, or dSIVHRγ-transduced HeLa or Rat-2 cells were not significantly different (Table 2). Gag was undetectable in the supernatants of the mock-transduced cells. The treatment of cells with azidothymidine (an RT inhibitor) before the addition of the pseudotyped viruses led to undetectable levels of Gag (data not shown), indicating that the assay measured newly synthesized viral proteins but not the original transducing particles. These experiments demonstrated that the expression of IFN-γ at early or late stages of the viral replication cycle did not alter levels and kinetics of Gag expression at a low MOI.

FIG. 2.

IFN-γ was expressed at lower and higher levels by different constructs and did not alter the kinetics of Gag expression. (A) The rat IFN-γ concentrations in supernatants of Rat-2 cells transduced with the mock control, dSIVR, dSIVLRγ, or dSIVHRγ at an MOI of 0.5 were measured by ELISA at 2, 4, 7, and 10 days posttransduction. (B) In parallel, at the above-mentioned time points, transduced Rat-2 cells were stained intracellularly using antibody to Gag and the frequency of Gag-positive cells was recorded using the fluorescence microscope. The mean value for three fields for each sample stained in duplicate is shown, with bars indicating the SEM.

TABLE 2.

Gag produced by single-cycle SIVs in different cell linesa

| Viral particle designation | Amt of Gag (ng/ml) produced in:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| HeLa cells | Rat-2 cells | |

| Mock | <0.049b | <0.049b |

| dSIVR | 0.67 ± 0.026 | 0.45 ± 0.089 |

| dSIVLRγ | 0.61 ± 0.0079 | 0.35 ± 0.063 |

| dSIVHRγ | 0.71 ± 0.043 | 0.35 ± 0.030 |

HeLa or Rat-2 cells were transduced with different constructs at an MOI of 0.5. Two days posttransduction, supernatants were collected and p27 Gag concentrations were measured by ELISA. The data shown are the mean values ± SEM for triplicate samples.

The detection range for this assay is 0.049 to ∼0.784 ng/ml. The reading was under the detection limit.

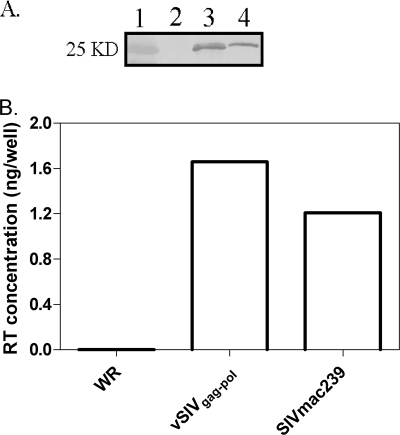

Preparation of surrogate challenge virus.

In order to evaluate vaccine efficiency, we constructed a VV (WR strain) expressing SIV Gag-Pol to be used as a surrogate challenge (2, 46). The gag-pol open reading frame was cloned by PCR and inserted under the dsP which were previously demonstrated to result in increased levels of expression compared to VV natural promoters (49). The gag-pol fragment was then introduced into the VV genome through homologous recombination and insertional inactivation of the VV B8R gene, generating vSIVgag-pol. The expression of Gag was confirmed by Western blot analysis using an anti-SIV p27 monoclonal antibody (19) (Fig. 3A), and the expression of Pol was confirmed by measuring RT activity (Fig. 3B). Results indicated that SIV Gag-Pol was expressed properly in the VV vector. We also used this viral stock as a positive control for the immunogenicity assays described in the following section, since it is a replication-competent virus and the expression of viral genes by VV in rat cells is not compromised. Thus, this control construct will be immunogenic.

FIG. 3.

Gag-Pol was expressed by vSIVgag-pol. (A) vSIVgag-pol was generated in B-SC-1 cells, harvested, and blotted using an anti-SIV p27 monoclonal antibody to confirm Gag expression. Lanes: 1, molecular mass standard (the molecular mass is marked on the left); 2, parental WR strain VV, which served as a negative control; 3, vSIVgag-pol; and 4, SIVmac239, which served as a positive control. (B) An RT assay was performed to confirm pol gene function in vSIVgag-pol. WR strain VV and SIVmac239 were negative and positive controls, respectively.

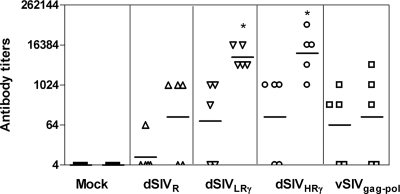

Characterization of vaccine-induced humoral and CMI responses.

The purpose of this study was to compare different single-cycle SIV constructs to determine the effects of lower and higher levels of IFN-γ expression on immunogenicity in vivo. Intradermal vaccination was chosen since Langerhans cells are located mainly in the stratum spinosum, where transduction with pseudotyped SIV particles will induce them to mature into potent antigen-presenting cells. Furthermore, it has been shown previously that HIV-1 long terminal repeat-driven gene expression takes place preferentially in Langerhans cells in the skin and lymphoid organs of transgenic mice (29). We measured vaccine-induced humoral responses by ELISA using two different coating antigens: p27 Gag expressed in E. coli and whole inactivated SIVmac251. In preliminary studies, one immunization gave rise to low SIV-specific antibody titers (data not shown) while one boost increased the titers significantly. The second boost further increased antibody titers in each group but also dramatically increased titers of antibodies to VSV-G (data not shown), which is not desirable as it may interfere with SIV-specific immunity (24). We therefore chose one immunization with one boost as our vaccine regimen and then analyzed the immune responses to SIV. Gag-specific antibody was detected in some animals in each group but not in the mock-vaccinated rats. No significant differences among the vaccinated groups were found (Fig. 4). This outcome may be due to the fact that Gag is not readily expressed, processed, and secreted in rat cells (3, 22). We further measured titers by ELISA using inactivated SIVmac251 as a coating antigen, and antibody was detected in almost all immunized animals (Fig. 4). Rats vaccinated with dSIVLRγ and dSIVHRγ had significantly higher antibody titers than the mock-vaccinated group (P < 0.05). Using inactivated virus as a coating antigen increases the number of available SIV epitopes. However, this effect did not result in increased titers in the vSIVgag-pol-vaccinated group. This result suggested that viral proteins other than Gag-Pol play important roles in the immunogenicities of pseudotyped SIVs.

FIG. 4.

Prechallenge antigen-specific humoral responses were enhanced by IFN-γ expression. Groups of F344 rats (five animals per group) were inoculated and boosted once with different constructs. Antibody titers 2 weeks after the boost were determined using recombinant SIVmac251 p27 Gag (corresponding to the first column for each group) produced in an E. coli expression system or SIVmac251 viral lysates (corresponding to the second column for each group) as coating antigens for ELISA. Results are shown as mean titers of individual samples assayed in duplicate and the geometric means for each group (bars). Comparative analysis was performed by using nonparametric ANOVA, followed by a multiple-comparison test. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between pseudotyped SIV groups and the mock control are marked by *.

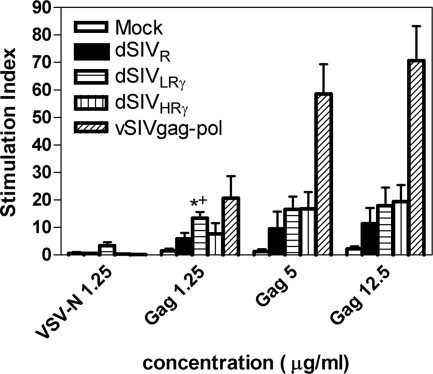

We then measured p55 Gag-specific lymphocyte proliferation responses to evaluate CD4+-T-cell responses (12, 13). Splenocytes harvested at 2 weeks postboost were stimulated by p55 Gag at increasing concentrations. VSV-N and ConA served as negative and positive controls, respectively. VSV-N consistently resulted in an SI of no more than 3, while ConA resulted in an SI of >50 (data not shown). The vSIVgag-pol group also served as a positive control. The finding that immune responses to p55 Gag at 12.5 and 5 μg/ml were similar suggests that the latter concentration had reached the threshold level for maximum cellular responses. There were no significant differences between the dSIVHRγ and dSIVLRγ groups. The dSIVLRγ group had a significantly higher SI than the dSIVR- and mock-vaccinated groups (P < 0.05) at only one concentration (1.25 μg/ml of p55 Gag), due probably to the high variability of the results at the other Gag concentrations (Fig. 5). Overall, animals vaccinated with dSIVs expressing IFN-γ had greater proliferative responses to Gag than those vaccinated with dSIVR.

FIG. 5.

Prechallenge p55 Gag-specific T-cell proliferation was enhanced by IFN-γ expression. Five groups of F344 rats (six animals per group) were vaccinated and boosted once with different constructs. Splenocytes were obtained at 2 weeks postboost and then stimulated in vitro with baculovirus-expressed VSV-N at a final concentration of 1.25 μg/ml or p55 Gag at a final concentration of 0, 1.25, 5, or 12.5 μg/ml. Cell proliferation was expressed as the SI, which was calculated as a ratio of the counts per minute in the presence and absence of antigen. Statistic analysis was performed using ANOVA. A significant difference (P < 0.05) between dSIVLRγ-immunized and mock-immunized animals is marked by *, while a significant difference between dSIVLRγ-immunized and dSIVR-immunized animals is marked by +.

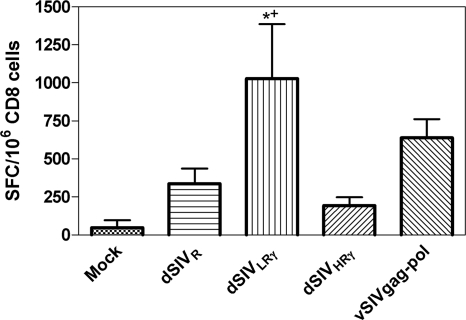

We next evaluated antigen-specific CD8+-T-cell responses using the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. At 2 weeks postboost, CD4-depleted splenocytes were stimulated in vitro with pools of 15-mer peptides spanning SIV Gag. A human T-lymphotropic virus Env peptide was used as a mock stimulation control and did not result in positive responses. dSIVR did not induce significantly higher levels of CD8 responses than the mock control (P > 0.05) (Fig. 6), whereas dSIVLRγ induced stronger CD8 responses than the mock control (P < 0.01) and dSIVR (P < 0.05). Unexpectedly, dSIVHRγ gave rise to significantly weaker CD8 responses than dSIVLRγ (P < 0.05). These responses were not significantly different from those of the mock- and the dSIVR-immunized groups, suggesting that concentrations of IFN-γ that enhance the immune response have a narrow range. Although a direct comparison cannot be made, 106 TU of dSIVLRγ induced CD8 responses equivalent to those induced by vaccination with vSIVgag-pol, indicating the strong adjuvant effects of IFN-γ expressed at this level by single-cycle SIV.

FIG. 6.

Gag-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were significantly enhanced by low levels of IFN-γ expression. CD4+-T-cell-depleted-splenocytes from animals (six animals per group) immunized with different constructs were stimulated with 15-mer peptide pools spanning SIV Gag, and IFN-γ-secreting cells were identified by using an ELISPOT analysis. A human T-lymphotropic virus Env peptide pool was used as a control and did not give rise to detectable numbers of SFC (result not shown). Bars represent the mean number of SFC for each group, and error bars represent SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA. The significant difference (P < 0.05) between dSIVLRγ-immunized and mock-immunized animals is marked by *, while the significant difference between dSIVLRγ-immunized and dSIVR immunized-animals is marked by +.

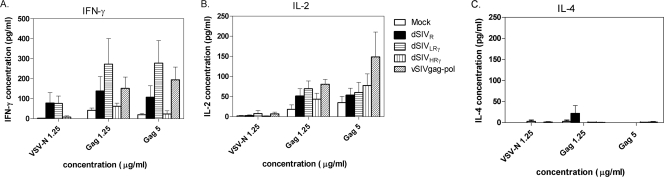

To study the vaccine-induced cytokine secretion profile of Th cells, various cytokines were measured in supernatants of splenocytes that were stimulated with SIV p55 Gag at final concentrations of 1.25 and 5 μg/ml, which were within a linear range for detection of the proliferative responses; VSV-N at 1.25 μg/ml served as a control. VSV-N induced low levels of IFN-γ nonspecifically in cells obtained from dSIVR- and dSIVLRγ-vaccinated animals but not vSIVgag-pol-vaccinated rats. This observation suggests that splenocytes from dSIVR- and dSIVLRγ-vaccinated animals were more activated than those from vSIVgag-pol-vaccinated animals. This difference may be due to the length of time of exposure to the antigen since the recombinant VV vector is rapidly cleared compared to the integrated retrovirus vector. Similar to the samples analyzed for CD8+-T-cell responses by the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay, cells from the various groups showed that dSIVLRγ-vaccinated rats secreted larger amounts of IFN-γ in response to specific antigen than splenocytes obtained from mock- or dSIVR-immunized animals (Fig. 7A). However, vaccination with dSIVHRγ again resulted in cells with a reduced IFN-γ expression response to specific antigen compared to those of T cells from animals vaccinated with dSIVR or dSIVLRγ. This result suggests that the higher level of expression of IFN-γ from dSIVHRγ may result in negative regulation of IFN-γ secretion from T cells. All of the vaccines appeared to polarize CD4+ T lymphocytes to a Th1 immune response, since the cells secreted higher levels of IFN-γ and IL-2 than IL-4 (Fig. 7). Despite the lower levels of IFN-γ secretion from cells from dSIVHRγ-vaccinated animals, the levels of IL-2 secreted were similar to those induced by the other vaccines (Fig. 7B). The relative levels of IL-2 in each group correlated with the proliferation responses shown in Fig. 5.

FIG. 7.

Prominent Th1 polarization in dSIVLRγ-immunized animals was detected. The production of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 after SIVp55 Gag-specific stimulation or VSV-N nonspecific stimulation of splenocytes from immunized animals was demonstrated. Cytokine concentrations in supernatants of stimulated cells were measured by ELISA. Positive controls were ConA-stimulated splenocytes (results not shown). Bars represent the mean concentration for each group, and error bars represent SEM.

Surrogate VV challenge.

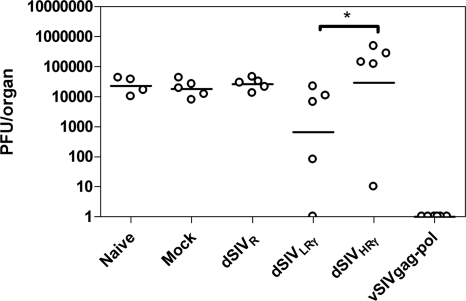

Due to the significant block to HIV/SIV entry into rat cells (3, 22, 38), direct challenge of vaccinated rats by SIV is impossible. On the other hand, surrogate challenge by VV expressing HIV proteins has been used previously for mice to prove the effectiveness of HIV DNA or peptide vaccines (2, 46); we thus challenged F344 rats intraperitoneally with the WR strain construct vSIVgag-pol for the same purpose. We collected ovaries after the challenge, since VV replicates to high titers in this tissue. We then performed a plaque assay to measure the VV load. In preliminary studies, we detected the highest levels of VV in ovaries of unimmunized animals 3 days postchallenge (data not shown). Challenge virus was undetectable in rats vaccinated with vSIVgag-pol, as expected (Fig. 8), although the result for this group cannot specifically indicate what type of immunity was acting to reduce virus loads in the challenge of the pseudotyped-virus-vaccinated animals. There were no differences in viral loads after challenge in the mock- and dSIVR-vaccinated groups, which correlated with the poor immunogenicity of the vaccine as discussed above. Rats immunized with dSIVLRγ had a 70% reduction of viral load on average; one of five animals had undetectable VV loads. The dSIVHRγ group had the highest mean viral load of all the groups, although one of five animals had a very low viral load. The viral load in this group was significantly higher than that in the dSIVLRγ group (P < 0.05), correlating with the lower levels of IFN-γ, a critical mediator in VV clearance (14, 37), secreted by both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells after in vitro restimulation with SIV Gag. Again, the pseudochallenge results correlated with the immune responses measured as described above.

FIG. 8.

VV loads in ovaries after surrogate challenge corresponded to prechallenge T-cell responses. Immunized and naïve rats were challenged by vSIVgag-pol as described in Materials and Methods. Ovaries were collected and assayed on BS-C-1 cells to determine VV loads 3 days postchallenge. Naïve rats served as a control. Data represent viral loads in individual rats, and bars indicate the geometric mean for each group.

DISCUSSION

We have been investigating ways to produce safe and efficacious vaccines by incorporating adjuvant and attenuating genes. Our previous studies demonstrated that, in the VV and SIV systems, the expression of IFN-γ enhances host immune defenses while attenuating pathogenic agents (16, 17, 27). Differential production of cytokines by Th cells during an immune response has important regulatory effects on the nature of the response. Infection with virulent SIVmac239 induced a Th2 response (high levels of IL-4, IL-10, macrophage inflammatory proteins 1α and 1β, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and RANTES and low levels of IL-12 and granzyme B), whereas infection with the more attenuated SIVΔnef resulted in a Th1 response (53). Therefore, the maintenance of a Th1 phenotype is probably critical to the control of HIV/SIV replication. IFN-γ inhibits the proliferation of Th2 cells, resulting in the preferential expansion of Th1 cells (9). This cytokine affects the activities of macrophages, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, and T cells by enhancing antigen presentation, cell differentiation, and cytokine expression profiles, ultimately resulting in enhanced antiviral effector functions (32). Thus, we constructed VSV-G-pseudotyped single-cycle SIVs expressing human IFN-γ to enhance immunogenicity as well as mimic live-attenuated vaccines, minimize pathogenesis, and expand target cell populations (35). By placing the IFN-γ gene at different regions in the SIV genome, we obtained lower and higher levels of IFN-γ expression and showed that the resulting constructs enhanced the activation and function of primate dendritic cells in vitro (35).

To further test the immunogenicities of these constructs, we replaced the human IFN-γ gene with the rat IFN-γ gene to enable us to do preliminary experiments in a rat model. After confirming that kinetics and levels of Gag expression were not affected significantly by IFN-γ expression in vitro (Fig. 2 and Table 2), we compared the immunogenicities of the different constructs by measuring immune responses to SIV Gag in animals. It has been shown previously that rat-derived cells support substantial levels of early HIV gene expression while displaying quantitative, qualitative, and cell type-specific limitations in supporting the expression of late genes such as gag (22). We demonstrated that Gag is detectable in the supernatants of Rat-2 cells, although it is expressed at a lower level than that in HeLa cells (Table 2). Although the lower viral gene expression in rat cells may have affected vaccine immunogenicity, there were detectable differences in resistance to challenge. Thus, the rat model appears to be suitable for preliminary studies before initiating experiments with nonhuman primates.

IFN-γ expression in both of our vaccine constructs enhanced antigen-specific humoral and proliferative responses. However, the different levels of IFN-γ had different effects on the responses of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes to specific antigen, as demonstrated by measuring IFN-γ secretion. Compared to vaccination with dSIVR, vaccination with dSIVLRγ induced strong CD4+-T-cell lymphoproliferative responses, increased numbers of IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells, and pronounced Th1 polarization 2 weeks postboost. On the other hand, vaccination with dSIVHRγ resulted in decreased levels of IFN-γ secretion from both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared to vaccination with dSIVR and dSIVLRγ, although levels of antibody, proliferative responses, and IL-2 secretion were similar to those induced by vaccination with dSIVLRγ. Moreover, vaccination with dSIVLRγ resulted in lower viral loads postchallenge than vaccination with dSIVHRγ; rats immunized with dSIVHRγ had mean viral loads higher than those found in the mock-vaccinated controls. Since IFN-γ is a critical component of mediators essential to VV clearance (14, 37), a diminished IFN-γ response to viral antigens is likely to result in greater virus replication. Hence, it is not surprising that in vitro assays demonstrating less IFN-γ secretion from both CD8+ and CD4+ splenocytes from the dSIVHRγ-vaccinated group after restimulation correlated with higher postchallenge VV loads. In contrast, vaccination with dSIVLRγ appeared to result in a prolonged effector phase, causing higher levels of responses to nonspecific antigen (VSV-N) and greater memory responses to specific antigen (Gag). These responses suggest that the expression of IFN-γ at this level may induce immune responses more similar to those induced by live-attenuated SIVs, due possibly to persistent antigenic stimulation (24). How these constructs influence long-term protective immunity against SIV challenge remains to be determined.

The poorer protection against surrogate challenge in the dSIVHRγ-vaccinated rats suggests that the range of IFN-γ expression levels required to enhance protective immunity is relatively narrow and too much IFN-γ can actually result in an immune response that may potentiate viral replication by decreasing CD4+- and CD8+-T-lymphocyte responses. A very similar result for a Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine regime using IFN-γ as an adjuvant was seen previously. Whereas a dose of 5 μg of IFN-γ per mouse per immunization gave optimal protection, 50 μg of IFN-γ per mouse resulted in a virus load that was equal to or even higher than that observed in naïve animals (20). A high level of IFN-γ may activate non-T-cell populations, such as macrophages and granulocytes; the latter secrete factors including reactive oxygen metabolites that impair T-cell activity by downregulating the ξ subunit of the T-cell receptor complex (4). Consistent with this pattern, other groups have suggested that high levels of IFN-γ promote the induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase by activated macrophages, generating levels of nitric oxide (NO) which can inhibit T-cell proliferation (23, 51). The inhibition is dose dependent and transient (15, 25) and likely to be cell type dependent, since CD8+ T cells are more susceptible to the detrimental effects of NO than CD4+ T cells and B cells are protected by NO against apoptosis (26, 33). This explains why T and B cells reacted differently to high levels of IFN-γ expression in the present study. The discrepancy in dSIVHRγ-induced immune responses between the present in vivo study and our previous in vitro study is likely due to the fact that monocyte-derived dendritic cells were used previously as antigen-presenting cells, which are not affected by NO-mediated immune impairment (51). Nevertheless, the in vitro study results and the in vivo proliferation and antibody responses indicate that the lack of protection by dSIVHRγ is not due to low immunogenicity of this construct. This does not suggest, but cannot exclude the possibility, that the overexpression of IFN-γ from the nef locus, encoding a viral early gene product, might have had cytotoxic side effects that shortened the life span of dSIVHRγ-transduced cells and thereby reduced the half-life of antigen presentation in vivo.

Other nonreplicating viral vectors, including modified VV Ankara, replication-defective adenovirus, and alphavirus replicons (7, 36, 47), have been used as SIV vaccine strategies for safety reasons. Although strong CMI responses have been induced, preexisting vector-induced immunity can interfere with vaccine efficacy and may limit the efficiency of booster immunization. Preexisting immunity to VSV-G in humans or rhesus macaques is quite rare (8), and this approach should induce the optimal level of immune response since there is no interference from previous vaccination with the vector. Moreover, the construction of pseudotyped SIVs with different serotypes of VSV-G may further increase the efficiency of booster immunizations by eliminating the interference of neutralizing antibodies generated against the priming serotype (42). Since the preparation of pseudotyped viral particles is relatively simple, VSV-G could also be replaced by other viral envelopes to specifically target an organ or cell types (6, 48). Thus, this is an open-ended system, with wide-ranging applications for different therapeutic and prophylactic purposes. Another advantage of our strategy is that it permits mucosal administration, since this is the natural route of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection (30). It has been shown previously that a single intranasal (i.n.) immunization with a recombinant VSV expressing the hemagglutinin protein of influenza or measles virus completely protects animals against lethal challenge with influenza or measles virus (40, 45). VSV expressing HIV/SIV gag or env has been widely studied recently, with promising results (36, 41). Significantly stronger antigen-specific CMI responses to i.n. vaccination than to intramuscular vaccination have been detected previously (8). Since our strategy also utilizes a VSV-G-mediated entry mechanism, our future studies will employ i.n. administration, which may further enhance mucosal immunity.

A study of rhesus macaques immunized with a single-cycle SIV showed promising results in inducing virus-specific immunity and reducing viral loads after challenge with SIVmac239 (10). Our study provides evidence for the specific enhancement of the CMI and humoral responses to SIV by the expression of IFN-γ in a single-cycle SIV construct and provides evidence of the usefulness of the rat model. Due to the limited number of animals in each group, high variations in viral loads in some groups were observed, which may contribute to the lack of significant differences in postchallenge virus loads. Lower viral gene expression in rat cells than in primate cells may also affect vaccine immunogenicity, as well as vaccine efficacy. Since IFN-γ may play different roles in VV and SIV clearance, it is possible that we might observe different results if a direct SIV challenge of rats was possible. Since the results in our study were encouraging, we plan to conduct similar studies with rhesus macaques to confirm our observations with the rat model.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the International Laboratory of Molecular Biology for Tropical Disease Agents, especially Julia Collins, Kenneth Chan, Shirley Leung, Lael Brown, and Colleen Tang, for their assistance; Hung Y. Fan from the University of California, Irvine, for providing the pV1EGFP plasmid; and the Immunology Core Laboratory of the California National Primate Research Center for assistance with the CMI study.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI47025, AI53811, AI54951, and AI66344 (to T.D.Y.) and AI59185 (to P.H.V.). Y.P. received support from the Jastro Shields scholarship and the University of California, Davis, humanities graduate research award.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 December 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad, S., B. Lohman, M. Marthas, L. Giavedoni, Z. el-Amad, N. L. Haigwood, C. J. Scandella, M. B. Gardner, P. A. Luciw, and T. Yilma. 1994. Reduced virus load in rhesus macaques immunized with recombinant gp160 and challenged with simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10195-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belyakov, I. M., M. A. Derby, J. D. Ahlers, B. L. Kelsall, P. Earl, B. Moss, W. Strober, and J. A. Berzofsky. 1998. Mucosal immunization with HIV-1 peptide vaccine induces mucosal and systemic cytotoxic T lymphocytes and protective immunity in mice against intrarectal recombinant HIV-vaccinia challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 951709-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bieniasz, P. D., and B. R. Cullen. 2000. Multiple blocks to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in rodent cells. J. Virol. 749868-9877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bronstein-Sitton, N., L. Cohen-Daniel, I. Vaknin, A. V. Ezernitchi, B. Leshem, A. Halabi, Y. Houri-Hadad, E. Greenbaum, Z. Zakay-Rones, L. Shapira, and M. Baniyash. 2003. Sustained exposure to bacterial antigen induces interferon-gamma-dependent T cell receptor zeta down-regulation and impaired T cell function. Nat. Immunol. 4957-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chackerian, B., E. M. Long, P. A. Luciw, and J. Overbaugh. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors participate in postentry stages in the virus replication cycle and function in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 713932-3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cronin, J., X. Y. Zhang, and J. Reiser. 2005. Altering the tropism of lentiviral vectors through pseudotyping. Curr. Gene Ther. 5387-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, N. L., I. J. Caley, K. W. Brown, M. R. Betts, D. M. Irlbeck, K. M. McGrath, M. J. Connell, D. C. Montefiori, J. A. Frelinger, R. Swanstrom, P. R. Johnson, and R. E. Johnston. 2000. Vaccination of macaques against pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus with Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon particles. J. Virol. 74371-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egan, M. A., S. Y. Chong, N. F. Rose, S. Megati, K. J. Lopez, E. B. Schadeck, J. E. Johnson, A. Masood, P. Piacente, R. E. Druilhet, P. W. Barras, D. L. Hasselschwert, P. Reilly, E. M. Mishkin, D. C. Montefiori, M. G. Lewis, D. K. Clarke, R. M. Hendry, P. A. Marx, J. H. Eldridge, S. A. Udem, Z. R. Israel, and J. K. Rose. 2004. Immunogenicity of attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus vectors expressing HIV type 1 Env and SIV Gag proteins: comparison of intranasal and intramuscular vaccination routes. AIDS Res. Hum Retrovir. 20989-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erard, F., M. T. Wild, J. A. Garcia-Sanz, and G. Le Gros. 1993. Switch of CD8 T cells to noncytolytic CD8− CD4− cells that make TH2 cytokines and help B cells. Science 2601802-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans, D. T., J. E. Bricker, H. B. Sanford, S. Lang, A. Carville, B. A. Richardson, M. Piatak, Jr., J. D. Lifson, K. G. Mansfield, and R. C. Desrosiers. 2005. Immunization of macaques with single-cycle simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) stimulates diverse virus-specific immune responses and reduces viral loads after challenge with SIVmac239. J. Virol. 797707-7720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falkner, F. G., and B. Moss. 1988. Escherichia coli gpt gene provides dominant selection for vaccinia virus open reading frame expression vectors. J. Virol. 621849-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauduin, M. C., R. L. Glickman, S. Ahmad, T. Yilma, and R. P. Johnson. 1999. Immunization with live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus induces strong type 1 T helper responses and beta-chemokine production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9614031-14036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauduin, M. C., A. Kaur, S. Ahmad, T. Yilma, J. D. Lifson, and R. P. Johnson. 2004. Optimization of intracellular cytokine staining for the quantitation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses in rhesus macaques. J. Immunol. Methods 28861-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gherardi, M. M., J. C. Ramirez, and M. Esteban. 2003. IL-12 and IL-18 act in synergy to clear vaccinia virus infection: involvement of innate and adaptive components of the immune system. J. Gen. Virol. 841961-1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gherardi, M. M., J. C. Ramirez, and M. Esteban. 2000. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) enhancement of the cellular immune response against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env antigen in a DNA prime/vaccinia virus boost vaccine regimen is time and dose dependent: suppressive effects of IL-12 boost are mediated by nitric oxide. J. Virol. 746278-6286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giavedoni, L., S. Ahmad, L. Jones, and T. Yilma. 1997. Expression of gamma interferon by simian immunodeficiency virus increases attenuation and reduces postchallenge virus load in vaccinated rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 71866-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giavedoni, L. D., L. Jones, M. B. Gardner, H. L. Gibson, C. T. Ng, P. J. Barr, and T. Yilma. 1992. Vaccinia virus recombinants expressing chimeric proteins of human immunodeficiency virus and gamma interferon are attenuated for nude mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 893409-3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giavedoni, L. D., and T. Yilma. 1996. Construction and characterization of replication-competent simian immunodeficiency virus vectors that express gamma interferon. J. Virol. 702247-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins, J. R., S. Sutjipto, P. A. Marx, and N. C. Pedersen. 1992. Shared antigenic epitopes of the major core proteins of human and simian immunodeficiency virus isolates. J. Med. Primatol. 21265-269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovav, A. H., Y. Fishman, and H. Bercovier. 2005. Gamma interferon and monophosphoryl lipid A-trehalose dicorynomycolate are efficient adjuvants for Mycobacterium tuberculosis multivalent acellular vaccine. Infect. Immun. 73250-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keppler, O. T., F. J. Welte, T. A. Ngo, P. S. Chin, K. S. Patton, C. L. Tsou, N. W. Abbey, M. E. Sharkey, R. M. Grant, Y. You, J. D. Scarborough, W. Ellmeier, D. R. Littman, M. Stevenson, I. F. Charo, B. G. Herndier, R. F. Speck, and M. A. Goldsmith. 2002. Progress toward a human CD4/CCR5 transgenic rat model for de novo infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Exp. Med. 195719-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keppler, O. T., W. Yonemoto, F. J. Welte, K. S. Patton, D. Iacovides, R. E. Atchison, T. Ngo, D. L. Hirschberg, R. F. Speck, and M. A. Goldsmith. 2001. Susceptibility of rat-derived cells to replication by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 758063-8073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koblish, H. K., C. A. Hunter, M. Wysocka, G. Trinchieri, and W. M. Lee. 1998. Immune suppression by recombinant interleukin (rIL)-12 involves interferon gamma induction of nitric oxide synthase 2 (iNOS) activity: inhibitors of NO generation reveal the extent of rIL-12 vaccine adjuvant effect. J. Exp. Med. 1881603-1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuate, S., C. Stahl-Hennig, P. ten Haaft, J. Heeney, and K. Uberla. 2003. Single-cycle immunodeficiency viruses provide strategies for uncoupling in vivo expression levels from viral replicative capacity and for mimicking live-attenuated SIV vaccines. Virology 313653-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurzawa, H., M. Wysocka, E. Aruga, A. E. Chang, G. Trinchieri, and W. M. Lee. 1998. Recombinant interleukin 12 enhances cellular immune responses to vaccination only after a period of suppression. Cancer Res. 58491-499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasarte, J. J., F. J. Corrales, N. Casares, A. Lopez-Diaz de Cerio, C. Qian, X. Xie, F. Borras-Cuesta, and J. Prieto. 1999. Different doses of adenoviral vector expressing IL-12 enhance or depress the immune response to a coadministered antigen: the role of nitric oxide. J. Immunol. 1625270-5277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Legrand, F. A., P. H. Verardi, K. S. Chan, Y. Peng, L. A. Jones, and T. D. Yilma. 2005. Vaccinia viruses with a serpin gene deletion and expressing IFN-gamma induce potent immune responses without detectable replication in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1022940-2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Legrand, F. A., P. H. Verardi, L. A. Jones, K. S. Chan, Y. Peng, and T. D. Yilma. 2004. Induction of potent humoral and cell-mediated immune responses by attenuated vaccinia virus vectors with deleted serpin genes. J. Virol. 782770-2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leonard, J., J. S. Khillan, H. E. Gendelman, A. Adachi, S. Lorenzo, H. Westphal, M. A. Martin, and M. S. Meltzer. 1989. The human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat is preferentially expressed in Langerhans cells in transgenic mice. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 5421-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lichty, B. D., A. T. Power, D. F. Stojdl, and J. C. Bell. 2004. Vesicular stomatitis virus: re-inventing the bullet. Trends Mol. Med. 10210-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacGregor, G. R., G. P. Nolan, S. Fiering, M. Roederer, and L. A. Herzenberg. 1991. Use of E. coli lacZ (β-galactosidase) as a reporter gene, p. 217-235. In E. J. Murray (ed.), Gene transfer and expression protocols, vol. 7. Humana Press, Clifton, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malmgaard, L. 2004. Induction and regulation of IFNs during viral infections. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 24439-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mannick, J. B., K. Asano, K. Izumi, E. Kieff, and J. S. Stamler. 1994. Nitric oxide produced by human B lymphocytes inhibits apoptosis and Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. Cell 791137-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pahar, B., J. Li, T. Rourke, C. J. Miller, and M. B. McChesney. 2003. Detection of antigen-specific T cell interferon gamma expression by ELISPOT and cytokine flow cytometry assays in rhesus macaques. J. Immunol. Methods 282103-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng, Y., F. C. Lin, P. H. Verardi, L. A. Jones, M. B. McChesney, and T. D. Yilma. 2007. Pseudotyped single-cycle simian immunodeficiency viruses expressing gamma interferon augment T-cell priming responses in vitro. J. Virol. 812187-2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramsburg, E., N. F. Rose, P. A. Marx, M. Mefford, D. F. Nixon, W. J. Moretto, D. Montefiori, P. Earl, B. Moss, and J. K. Rose. 2004. Highly effective control of an AIDS virus challenge in macaques by using vesicular stomatitis virus and modified vaccinia virus Ankara vaccine vectors in a single-boost protocol. J. Virol. 783930-3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramshaw, I. A., A. J. Ramsay, G. Karupiah, M. S. Rolph, S. Mahalingam, and J. C. Ruby. 1997. Cytokines and immunity to viral infections. Immunol. Rev. 159119-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reid, W., M. Sadowska, F. Denaro, S. Rao, J. Foulke, Jr., N. Hayes, O. Jones, D. Doodnauth, H. Davis, A. Sill, P. O'Driscoll, D. Huso, T. Fouts, G. Lewis, M. Hill, R. Kamin-Lewis, C. Wei, P. Ray, R. C. Gallo, M. Reitz, and J. Bryant. 2001. An HIV-1 transgenic rat that develops HIV-related pathology and immunologic dysfunction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 989271-9276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reiser, J. 2000. Production and concentration of pseudotyped HIV-1-based gene transfer vectors. Gene Ther. 7910-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts, A., E. Kretzschmar, A. S. Perkins, J. Forman, R. Price, L. Buonocore, Y. Kawaoka, and J. K. Rose. 1998. Vaccination with a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing an influenza virus hemagglutinin provides complete protection from influenza virus challenge. J. Virol. 724704-4711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rose, N. F., P. A. Marx, A. Luckay, D. F. Nixon, W. J. Moretto, S. M. Donahoe, D. Montefiori, A. Roberts, L. Buonocore, and J. K. Rose. 2001. An effective AIDS vaccine based on live attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus recombinants. Cell 106539-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rose, N. F., A. Roberts, L. Buonocore, and J. K. Rose. 2000. Glycoprotein exchange vectors based on vesicular stomatitis virus allow effective boosting and generation of neutralizing antibodies to a primary isolate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 7410903-10910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rudolph, D. L., and R. B. Lal. 1993. Discrimination of human T-lymphotropic virus type-I and type-II infections by synthetic peptides representing structural epitopes from the envelope glycoproteins. Clin. Chem. 39288-292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakaue, G., T. Hiroi, Y. Nakagawa, K. Someya, K. Iwatani, Y. Sawa, H. Takahashi, M. Honda, J. Kunisawa, and H. Kiyono. 2003. HIV mucosal vaccine: nasal immunization with gp160-encapsulated hemagglutinating virus of Japan-liposome induces antigen-specific CTLs and neutralizing antibody responses. J. Immunol. 170495-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlereth, B., J. K. Rose, L. Buonocore, V. ter Meulen, and S. Niewiesk. 2000. Successful vaccine-induced seroconversion by single-dose immunization in the presence of measles virus-specific maternal antibodies. J. Virol. 744652-4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shata, M. T., and D. M. Hone. 2001. Vaccination with a Shigella DNA vaccine vector induces antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and antiviral protective immunity. J. Virol. 759665-9670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiver, J. W., T. M. Fu, L. Chen, D. R. Casimiro, M. E. Davies, R. K. Evans, Z. Q. Zhang, A. J. Simon, W. L. Trigona, S. A. Dubey, L. Huang, V. A. Harris, R. S. Long, X. Liang, L. Handt, W. A. Schleif, L. Zhu, D. C. Freed, N. V. Persaud, L. Guan, K. S. Punt, A. Tang, M. Chen, K. A. Wilson, K. B. Collins, G. J. Heidecker, V. R. Fernandez, H. C. Perry, J. G. Joyce, K. M. Grimm, J. C. Cook, P. M. Keller, D. S. Kresock, H. Mach, R. D. Troutman, L. A. Isopi, D. M. Williams, Z. Xu, K. E. Bohannon, D. B. Volkin, D. C. Montefiori, A. Miura, G. R. Krivulka, M. A. Lifton, M. J. Kuroda, J. E. Schmitz, N. L. Letvin, M. J. Caulfield, A. J. Bett, R. Youil, D. C. Kaslow, and E. A. Emini. 2002. Replication-incompetent adenoviral vaccine vector elicits effective anti-immunodeficiency-virus immunity. Nature 415331-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steffens, S., J. Tebbets, C. M. Kramm, D. Lindemann, A. Flake, and M. Sena-Esteves. 2004. Transduction of human glial and neuronal tumor cells with different lentivirus vector pseudotypes. J. Neurooncol. 70281-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verardi, P. H., F. H. Aziz, S. Ahmad, L. A. Jones, B. Beyene, R. N. Ngotho, H. M. Wamwayi, M. G. Yesus, B. G. Egziabher, and T. D. Yilma. 2002. Long-term sterilizing immunity to rinderpest in cattle vaccinated with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing high levels of the fusion and hemagglutinin glycoproteins. J. Virol. 76484-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verardi, P. H., L. A. Jones, F. H. Aziz, S. Ahmad, and T. D. Yilma. 2001. Vaccinia virus vectors with an inactivated gamma interferon receptor homolog gene (B8R) are attenuated in vivo without a concomitant reduction in immunogenicity. J. Virol. 7511-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamazaki, T., H. Akiba, A. Koyanagi, M. Azuma, H. Yagita, and K. Okumura. 2005. Blockade of B7-H1 on macrophages suppresses CD4+ T cell proliferation by augmenting IFN-gamma-induced nitric oxide production. J. Immunol. 1751586-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yedavalli, V. S., M. Benkirane, and K. T. Jeang. 2003. Tat and trans-activation-responsive (TAR) RNA-independent induction of HIV-1 long terminal repeat by human and murine cyclin T1 requires Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 2786404-6410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zou, W., A. A. Lackner, M. Simon, I. Durand-Gasselin, P. Galanaud, R. C. Desrosiers, and D. Emilie. 1997. Early cytokine and chemokine gene expression in lymph nodes of macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus is predictive of disease outcome and vaccine efficacy. J. Virol. 711227-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]