Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) have the capacity to self-renew and continuously differentiate into all blood cell lineages throughout life. At each branching point during differentiation, interactions with the environment are key in the generation of daughter cells with distinct fates. Here, we examined the role of the cell adhesion molecule JAM-C, a protein known to mediate cellular polarity during spermatogenesis, in hematopoiesis. We show that murine JAM-C is highly expressed on HSCs in the bone marrow (BM). Expression correlates with self-renewal, the highest being on long-term repopulating HSCs, and decreases with differentiation, which is maintained longest among myeloid committed progenitors. Inclusion of JAM-C as a sole marker on lineage-negative BM cells yields HSC enrichments and long-term multilineage reconstitution when transferred to lethally irradiated mice. Analysis of Jam-C–deficient mice showed that two-thirds die within 48 hours after birth. In the surviving animals, loss of Jam-C leads to an increase in myeloid progenitors and granulocytes in the BM. Stem cells and myeloid cells from fetal liver are normal in number and homing to the BM. These results provide evidence that JAM-C defines HSCs in the BM and that JAM-C plays a role in controlling myeloid progenitor generation in the BM.

Introduction

There is increasing evidence that interactions of stem cells with the environment are key in maintaining the balance between self-renewal and differentiation. Adult hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside in a special microenvironment known as the “niche,” which provides extrinsic regulatory signals that control intrinsic genetic programs required for HSC function.1–3 A number of cell-surface molecules on HSCs have been shown to regulate the maintenance of HSCs. Among others, these include bone morphogenic proteins,4 Ca-sensing receptor,5 Notch,6–8 α4,9 and Tie2.10 In addition, transcription profiling of the most primitive HSCs has identified cell junction proteins, which were previously not implicated in stem cell functions, to be differentially expressed11–13; moreover, adhesion and junction complexes have been proposed to trigger molecular signals, influencing the balance between self-renewal and differentiation.14

The junctional adhesion molecule JAM-C is a member of a family of adhesion molecules belonging to the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily. JAM-C was found to be expressed on a number of different cells such as endothelial15–17 and epithelial cells,18 fibroblasts,19 smooth muscle cells,20 spermatids,21,22 and peripheral nerves.23 Expression of JAM-C on platelets24 and lymphocytes16,25 is restricted to human tissue. JAM-C interacts via its ectodomain homotypically26,27 and heterotypically with the integrins αMβ2 and αXβ218,24, JAM-B,16,28–30 and the viral receptor CAR.21 Through the c-terminal PDS95/Dig/ZO-1 (PDZ) domain-binding motif, JAM-C associates with the PDZ domain containing proteins ZO-1, Par-3, Par-6, PATJ, and PICK-1,22,31,32 and localizes to cell-cell junctions.17,19,20,33,34

The broad expression and variety of counterreceptors suggests that JAM-C regulates heterotypic cell-cell interactions, such as leukocyte-endothelial interactions in the immune system, as well as homotypic cell-cell interactions, such as cellular junctions in endothelial and epithelial cells.35–39 Blocking of JAM-C function inhibits leukocyte migration in several in vivo models of inflammation,18,25,34,40–43 leukocyte-platelet interactions,24,44 and neovascularization in models of angiogenesis, a process that requires remodeling of endothelial junctions.33,45 JAM-C may also be necessary for the formation and maintenance of different cell junctions as it colocalizes at cell-cell contacts with adherence and tight junction proteins.19,33,46,47 JAM-C–mediated cell polarization has been proposed as the underlying mechanism for its functions.39 JAM-C directly associates with the cell polarity protein PAR-3, targeting it to tight junctions.31 Furthermore, JAM-C–mutant mice are infertile due to a defect in spermatid differentiation, which requires polarization of round spermatids.22 JAM-C appears to be essential for the assembly of a cell polarity complex containing PAR-6, aPKC, PATJ, and the small GTPase Cdc42 that ensures elongation and maturation of spermatids.

Here, we investigate the role of JAM-C in hematopoiesis. We demonstrate that JAM-C is expressed on hematopoietic progenitors and that expression levels decrease with loss of self-renewal and increased differentiation. Deletion of Jam-C in mice resulted in increased bone marrow (BM) cellularity caused by an increase in myeloid progenitors and granulocytes. Our phenotypic analysis combined with in vitro and in vivo characterization provides evidence that JAM-C is involved in the differentiation of HSCs into myeloid progenitors.

Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). The congenic strain Igha B6 Ptprca B6.SJL used for transfer experiments was generated by crossing B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ with B6.Cg-Igha Thy1a Gpi1a/J (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Jam-C−/− mice were generated by Lexicon Genetics (Woodlands, TX) by homologous recombination. Gestational age of heterozygous pregnancies was determined by detection of the vaginal plug as embryonic day (E) 0.5. All animals were housed in microisolators in a specific pathogen–free facility. Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Genentech.

Reagents

JAM-C–specific antibodies were generated by Josman (Napa, CA). In brief, rabbits were immunized with recombinant his-tagged murine JAM-C ectodomain. JAM-C reactive antibodies were obtained from the bleeds by affinity purification.

Cell isolation

BM cells were obtained from mouse femurs and tibia by flushing the central cavity with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Blood was collected from anesthetized mice by cardiac puncture and transferred to heparin-coated tubes (Sarstedt AG & Co, Nümbrecht, Germany). Red blood cells were lyzed in ACK buffer (Biosource Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA). For enrichment of early thymic progenitors, samples were depleted of single- and double-positive thymocytes by anti-CD4 (L3T4) and anti-CD8a (Ly-2) coupled magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Fetal livers (FLs) were dissected from E14.5 embryos.

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting

Purified cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% FCS and 10% mouse serum. Fc receptors were blocked with anti-CD16/CD32 (2.4G2; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and mouse serum IgG (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). For staining of granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMPs) and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor (MEP) biotin-labeled anti-CD16/32 was used for blocking. Surface expression of JAM-C was detected by staining with rabbit anti–murine JAM-C followed by PE-conjugated anti–rabbit F(ab′)2 secondary reagent (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Lineage-negative cells were identified by staining with the biotin- or FITC-conjugated mouse lineage panel (BD Pharmingen). For analysis of FL, CD11b was excluded from the lineage mix and replaced with CD5 (53-7.3), CD4 (GK1.5), and CD8-biotin (53-6.7). Additional antibodies used were c-Kit (2B8), Sca-1 (E13-161.7), Flt3 (A2F10.1), Thy1.2 (53-2.1), IL7Rα (A7R34), CD34 (S7), FcγRII/III (2.4G2), C1qRp (AA4.1), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD3ϵ (145-2C11), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), CD11b (M1/70), Ly-76 (Ter119), and CD45.2.(104) All biotin-conjugated or directly conjugated fluorescent antibodies used were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) or BD Pharmingen. Biotin-conjugated antibodies were visualized with either PerCP-streptavidin (BD Pharmingen), or Pacific Blue–streptavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Propidium iodide (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was added for exclusion of dead cells. Cells were analyzed on a 3-laser FACSscan (Cytek Development, Fremont, CA), or on a LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells were sorted on an Aria (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed with FlowJo (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

In vitro culture analysis

For cloning efficiency assessment, cells were seeded in round-bottom 96-well plates in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; Biosource Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) supplemented with 15% FCS (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), recombinant human (rh) insulin (Sigma-Aldrich), human transferrin (Serologicals, Billerica, MA), 2 mM glutamine (Gibco Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco Invitrogen), 50 μM mercaptoethanol (Gibco Invitrogen), 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), 10 ng/mL recombinant murine (rm) IL-3, 10 ng/mL rmIL-6, 50 ng/mL rmSCF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 2.5 μg/mL human erythropoietin (hEPO; Research Diagnostics Inc., Concord, MA). Colony growth was assessed after 10 days of culture at 37°C and 5% CO2. Methylcellulose cultures were initiated in 35-mm culture dishes with the indicated populations of cells purified by flow cytometry or with BM- and FL-derived single-cell suspensions. Cells were plated into duplicate dishes containing Methocult GF M3434 (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). Colonies were scored and phenotyped on an inverted-phase microscope after 10 days in culture.

Transplantation and engraftment assays

For BM transplantation experiments, the indicated number of sorted BM cells from C57BL6 mice together with 2 × 105 host-type BM cells were injected intravenously into the tail veins of lethally irradiated (12 Gy [1200 rad]) congenic B6/SJL mice. Peripheral blood was obtained from the tail vein at the indicated time points and analyzed by flow cytometry. For FL engraftment, 1 × 106 FL cells from E14.5 Jam-C−/− or Jam-C+/+ embryos were injected. After 8 weeks, the animals were humanely killed, and BM was harvested and analyzed for extent of reconstitution. Donor-derived cells were distinguished from host cells by the expression of different CD45 (Ly5; ptprc) antigen.

Genotyping

Mice were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In brief, genomic DNA was extracted from mouse tail clips or yolk sacs of embryos and used for subsequent PCR with ReadyAMP polymerase mix (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 cycles: 95°C for 60 seconds 60°C for 60 seconds. The primers used for wild-type allele amplification were 5′-TCA CAT TCC CCT CGA CAT GGC-3′ (p1) and 5′-ATC TGC CAC GGT CCT TCT AGA G-3′ (p2), which yielded a 347-bp product. The primers used for mutant allele amplification were 5′-TCA CAT TCC CCT CGA CAT GGC-3′ (p1) and 5′-GCA GCG CAT CGC CTT CTA TC-3′ (p3), which yielded a 412-bp product.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from testis with the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and reverse-transcribed using murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (MuLV-RT; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). cDNA was amplified using Advantage polymerase mix (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) for 37 cycles: 95°C for 60 seconds and 62°C for 60 seconds (JAM-C) or 66°C for 60 seconds (actin) and 68°C for 30 seconds. The following primer sequences were used for JAM-C: 5′-GAA GAT CTT CAC CAT GGC GCT GAG CCG G-3′ and 5′-CCA TCG ATG GTC AGA TAA CAA AGG ACG ATT TG-3′ (956 bp); and actin: 5′-CCA TGG ATG ACG ATA TCG CTG CGC TGG TCG-3′ and 5′-CCT AGA AGC ACT TGC GGT GCA CGA TGG AGG-3′ (1135 bp).

Western blot

The testis was homogenized in lysis buffer (0.5% TX-100, NaCl, and protease inhibitors) and the lysates were separated on 4% to 10% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen) and immunoblotted with rabbit anti–JAM-C or mouse anti–β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), followed by secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–labeled anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and visualized by SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

IHC and IF

Staining was performed on 5-μm-thick frozen sections of mouse testis fixed in acetone. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), endogenous peroxidase was quenched by glucose oxidase, and biotin was blocked with an avidin-biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). After blocking, the sections were incubated with anti–JAM-C at 0.1 μg/mL, followed by biotinylated goat anti–rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories). Staining was visualized using Vectastain ABC Elite reagents (Vector Laboratories), followed by metal enhanced diaminobenzidine (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Slides were counterstained with Meyer hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. For immunofluorescence (IF), sections were stained with DAPI (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) and coverslipped with ProLong Gold (Invitrogen).

Hematology

Blood was analyzed with an automated cell counter (Abbott CellDyn 3700; Abbott, Abbott Park, IL). E18.5 or postnatal (P) day 1 (P1) bleeds were analyzed with a hematology analyzer (scil Vet abc; scil animal care company, Gurnee, IL) and differential counts were determined by manual scoring of blood smears. White blood cell counts were adjusted to the number of nucleated red blood cells present.

Statistics

Statistical significance of the difference between groups was calculated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a t test assuming equal variance using JMP (SAS, Cary, NC). All P values less than or equal to .05 are considered significant and are indicated in the text.

Results

JAM-C expression on hematopoietic progenitors

HSCs are found within the lineage-negative (Lin−) fraction of the BM and can be further identified by expression of high levels of 2 other markers, the c-Kit receptor and stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1).48,49 HSCs have been named LSK cells based on the expression pattern of these markers: Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+. HSCs differentiate into common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), giving rise to the natural killer (NK) cell, T-cell, and B-cell lineages,50 or common myeloid progenitors (CMPs). CMPs differentiate into GMPs and MEPs,51 giving rise to granulocytes and monocytes, or megakaryocytes, and erythrocytes, respectively.

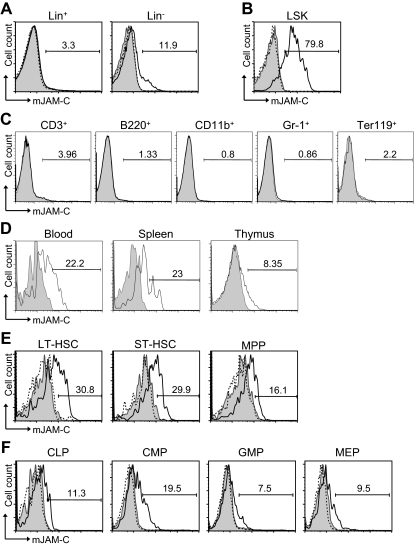

To address a potential role of JAM-C during hematopoiesis, we performed flow cytometric staining of HSCs. JAM-C is expressed on approximately 12% of Lin− cells but not on Lin+ cells in adult BM (Figure 1A). Within the lineage-negative population, JAM-C is highly expressed on LSK cells (Figure 1B). Staining of BM with lineage markers showed that JAM-C is not expressed on cells committed to specific lineages (Figure 1C). Although most adult HSCs reside in the BM, they can also be found in the peripheral blood. HSCs in the blood have the capacity to reengraft functional BM niches at distant sites.52 In addition, it has been proposed that LSK cells in the blood have efficient T-lineage potential and are able to seed the thymus.53 Thus, we examined the levels of JAM-C expression on HSCs in the blood and spleen, as well as in the thymus. JAM-C expression levels are decreased on LSK cells in the blood and spleen and almost absent on LSK cells in the thymus (Figure 1D), indicating that high levels of JAM-C expression are specific for HSCs in the BM.

Figure 1.

Expression of JAM-C on HSCs. (A) BM cells from BL6 mice were stained with anti-lineage cocktail (anti-CD3ϵ, anti-B220, anti-CD11b, anti–Gr-1, and anti-Ter119) and the lineage-positive (Lin+) and lineage-negative (Lin−) populations were analyzed for their JAM-C expression. (B) JAM-C expression on HSCs in the Lin− population defined by expression of Sca-1 and c-Kit (LSK). (C) BM cells were individually stained with lineage markers (anti-CD3ϵ, anti-B220, anti-CD11b, anti–Gr-1, and anti-Ter119) and analyzed for their expression of JAM-C. (D) Blood, thymus, and spleen cells were stained for JAM-C expression on LSK cells. (E) Staining of the different stem cell populations contained within the LSK gate with anti–JAM-C: LT-HSCs (Lin−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, Thy1.1+, and Flt-3−), ST-HSCs (Lin−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, Thy1.1+, and Flt-3+), and MPPs (Lin−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, Thy1.1−, and Flt-3−). (F) Expression of JAM-C on lymphoid progenitors (CLPs: Lin−, Sca-1int, c-Kitint, and Il7Rα+), and myeloid progenitors (CMPs: Lin−, Sca-1−, Il7Rα−, c-Kit+, CD34+, and FcγRII/III−; GMPs: Lin−, Sca-1−, Il7Rα−, c-Kit+, CD34+, and FcγRII/III+; MEPs: Lin−, Sca-1−, Il7Rα−, c-Kit+, CD34−, FcγRII/III−). Shown are representative histograms with anti–JAM-C staining (black histogram line), rabbit serum IgG (filled gray histogram), or anti–JAM-C together with 10 times excess of blocking murine JAM-C–Fc (hatched histogram line). The numbers above the brackets indicate the percentage of cells expressing JAM-C.

The population of LSK cells in the adult BM is composed of stem cells with different self-renewing potential: long-term repopulating HSCs (LT-HSCs) and short-term repopulating HSCs (ST-HSCs) as well as nonrenewing multipotent progenitors (MPPs).54,55 LT-HSCs showed the highest level of JAM-C expression (Figure 1E). The expression level gradually decreased as stem cells lost their self-renewal potential and became lineage committed (Figure 1F). A total of 19% of CMPs express low levels of JAM-C compared with 11% of CLPs. The percentage decreased further in the more mature GMP and MEP populations to 7% and 9%, respectively. These results indicate that JAM-C expression levels correlate with self-renewal and differentiation potential of HSCs, which are highest on LT-HSCs, and that expression is maintained longer among myeloid progenitors.

Colony-formation of JAM-C–expressing BM-derived cells

Although JAM-C expression is highest on LT-HSCs, analysis of the expression of the stem-cell markers Sca-1 and c-Kit on sorted JAM-C+ cells showed that the population is composed of stem cells and progenitors at different levels of differentiation. About 46% are LSK cells expressing high levels of c-Kit and Sca-1 (Figure 2A). Another 32% had high levels of c-Kit and low levels of Sca-1 and could therefore be classified as CMPs. A total of 3% had intermediate levels of c-Kit and Sca-1, which corresponds to CLPs, and 12% did not express either, which could reflect other cells present in the BM such as endothelial and/or stromal cells.

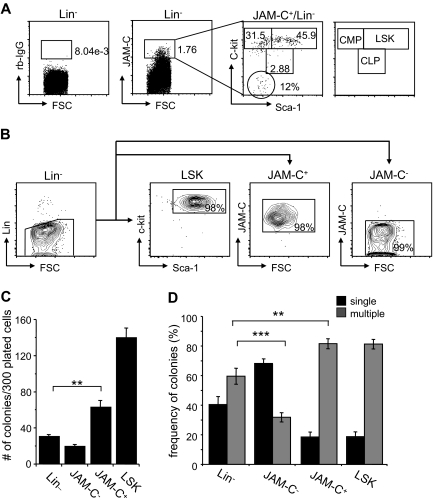

Figure 2.

Colony formation potential of JAM-C–expressing BM cells. (A) BM cells were stained with anti-lineage cocktail (anti-CD3ϵ, anti-B220, anti-CD11b, anti–Gr-1, and anti-Ter119), anti–Sca-1, anti–c-Kit, and anti–JAM-C. Subsequently, the Lin− cells were sorted into populations lacking JAM-C expression (JAM-C−), expressing JAM-C (JAM-C+), or expressing Sca-1 and c-Kit (LSK). Numbers indicate the percentage of cells in each gate after the sort. Shown is a representative FACS sort profile. (B) JAM-C+Lin− cells were gated and analyzed for expression of c-Kit and Sca-1, which are differentially expressed on hematopoietic progenitors (shown in the far right panel). Staining with control rabbit serum IgG is shown on the left of the dot plot. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells in each gate. (C) Lin−, JAM-C−, JAM-C+, and LSK cells were sorted from BM at a density of one cell per well into 96-well plates containing IMDM with mSCF, mIL-3, mIL-6, and hEPO. After 10 days of culture, the number of colonies was determined. Data represents mean number of colonies plus or minus SEM that grew in a total of 300 wells in 4 independent experiments. (D) Lin−, JAM-C−, JAM-C+, and LSK cells were sorted from BM for analysis of in vitro colony-forming ability. A total of 1000 Lin− and JAM-C− cells or 200 JAM-C+ and LSK cells were plated in methylcellulose containing mSCF, mIL-3, mIL-6, and hEPO. After 10 days, colonies were assigned scores for the presence of colonies containing single lineages (■) or multiple lineages (■). Data represent mean plus or minus SEM on duplicate plates of 4 independent experiments. Significances are shown on the graph. **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001.

To determine if JAM-C expressing cells are HSCs with self-renewal capacity, we sorted Lin− cells from the BM into 4 populations: a Lin− population, including all progenitor cells; a Lin−/JAM-C− population depleted of JAM-C–expressing progenitors (JAM-C−), a Lin−/Sca-1+/c-Kit+ population enriched in stem cells (LSK), and a Lin−/JAM-C+ population enriched in stem cells and early progenitors (JAM-C+; Figure 2B). Cells were sorted at a density of one cell per well into 96-well plates. After 10 days in culture, the number of wells with colonies was assessed (Figure 2C). Plating efficiency of JAM-C+ was 20%, about half of the LSK population, which had a plating efficiency of 50%. This correlates with the fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis, which showed that only 46% of JAM-C+ cells express high levels of the stem cell markers c-Kit and Sca-1 and correspond to LSK cells. Sorting on JAM-C–expressing cells within the Lin− population doubled the plating efficiency (P = .002). The number was low in the Lin− and JAM-C− populations, reaching plating efficiencies of about 10% and 6%, respectively. This result indicates that the JAM-C+ population is composed of stem cells that have the ability to self-renew as well as progenitors that do not self-renew under the provided conditions.

We next analyzed the in vitro differentiation potential of the sorted populations by comparing their colony-forming ability in methylcellulose. The generation of colonies with a single lineage is indicative of a more mature progenitor cell producing one lineage. In contrast, the presence of multilineage colonies is indicative of more immature progenitor cells with the capacity to differentiate into multiple lineages. The colonies growing from the Lin− population were composed of a similar percentage of single-lineage colonies (40%) and multilineage colonies (60%). Depleting the Lin− population from cells expressing JAM-C lead to a decrease in multilineage colonies (30%; P < .001; Figure 2D), indicating that this population is depleted of more immature progenitors that give rise to multilineage colonies. In contrast, including JAM-C as a marker in the sort increased the frequency of multilineage colonies (80%; P = .002), suggesting that JAM-C identifies progenitors within the Lin− population that are more immature and have multilineage potential. Both the JAM-C+ and LSK sorted populations give rise to similarly differentiated colonies composed to a large extent of multilineage colonies (80%). These data suggest that the JAM-C+ population is enriched in early progenitors with multilineage potential, and that inclusion of JAM-C in the Lin− sort leads to an increase in immature progenitors.

Lineage potential of JAM-C–expressing BM-derived cells

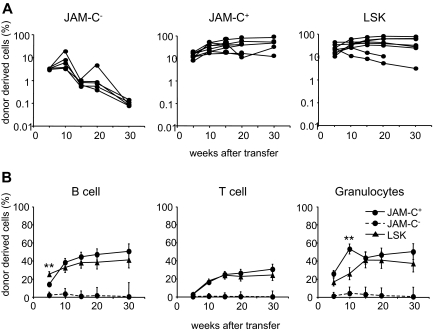

To determine the in vivo lineage potential of the sorted JAM-C+ population, we compared their repopulation potential with that of the JAM-C− and LSK populations. Sorted cells from B6 mice were injected intravenously into lethally irradiated B6.SJL hosts along with host-type BM. The repopulation capacity was assessed by the donor cell contribution to myeloid and lymphoid lineages in the peripheral blood measured by flow cytometry. Transfer of JAM-C+ cells resulted in a slightly elevated level of chimerism as transfer of LSK cells, assessed by the percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the blood (Figure 3A; Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). In contrast, the transfer of JAM-C− cells resulted in a low and transient wave of donor-derived immune cells. Using JAM-C as a marker on lineage-negative BM cells leads to the purification of HSCs that efficiently reconstitute lethally irradiated mice in the long term.

Figure 3.

Reconstitution potential of JAM-C+ BM cells. (A) A total of 500 JAM-C−, JAM-C+, and LSK cells were sorted from the BM of C57BL6 donor mice and injected intravenously into lethally irradiated BL6/SJL recipients along with 2 × 105 host-type BM cells for rescue. Peripheral blood was stained with anti-CD45.2 for identification of donor progeny and shown as the frequency of donor-derived cells after transfer. Each line represents the frequency of donor-derived cells in a single mouse. The experiment was repeated 3 times with an average of 5 animals per group. (B) The presence of donor-derived cells within the different blood cell lineages was determined by gating on B220+ (B cells), CD3ϵ+ (T cells), or CD11b+/Gr-1+ (granulocytes) prior to the assessment of the frequency of CD45.2+ cells, LSK cells (▴), JAM-C+ (—●—), and JAM-C− (- - -●- - -). Shown is the average of all mice of 3 independent experiments with an average of 5 animals per group that showed reconstitution above background level as determined by analysis of B6/SJL mice that did not receive transplants (≥ 0.4% B220+, and > 0% CD3+ and CD11b/Gr-1+). Significances are shown on the graph. **P ≤ .01.

The JAM-C+ population gave rise to a sustained production of T cells, B cells, and myeloid cells, indicating that like LSK subsets, the JAM-C+ population is composed of HSCs (Figure 3B). Compared with the LSK population, JAM-C+ cells showed a slower B-cell reconstitution potential at week 5 (P = .004) and a wave of increased granulocyte production at week 10 (P = .003). This observation is in agreement with our earlier finding that the JAM-C+ population contains 32% of Lin−/Sca-1−/c-Kit+ cells with myeloid potential. The presence of non–self-renewing myeloid progenitors in the transferred population could lead to a transient increase in granulocytes. All of the mice receiving JAM-C+ cells had donor-derived granulocytes at more than 5 weeks, and between 60% and 100% of the mice continued to have long-term granulocyte chimerism (Table S1). In contrast, only up to 20% of the mice receiving JAM-C− cells showed long-term granulocyte chimerism at very low levels. The JAM-C+ population is composed of HSCs that produce all blood cell lineages long term, and nonrenewing myeloid progenitors.

Mice deficient in JAM-C

To analyze the role of JAM-C in hematopoiesis, we obtained Jam-C−/− mice from Lexicon Genetics that were generated by deletion of exon 1 through homologous recombination (Figure S1A). Deletion of the gene was confirmed by PCR-based genotyping (Figure S1B). Loss of JAM-C expression was assessed by RT-PCR, Western blot, and IHC on testis tissue obtained from wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mice (Figure S1C-E). Absence of JAM-C expression was also observed on HSCs cells in the BM (Figure S1F). In accordance with previously published observations, many Jam-C−/− mice died perinatally (Table S1), some had megaesophagus (data not shown), and all mutant males were infertile, failing to produce mature spermatozoa (Figure S1E).22,56

Genotyping the offspring of heterozygous crosses at different developmental stages showed that Jam-C−/− mice were not found at expected frequency at 2 weeks after birth (3.8%). Although they were appropriately presented before birth (E18.5, 21.8%; Table 1), the majority of mutant mice died within 48 hours after birth (P2, 6.7%). Some mutant mice were cyanotic and gasping for air shortly after birth, filling the intestine with bubbles. As these are possible signs of anemia, we measured hematologic parameters and peripheral blood counts of E18.5 embryos as well as mice 6 to 10 weeks of age. Adult mice showed a small but significant increase in the neutrophil count (P = .049) compared with wild-type littermates (Table S2). No difference in the white blood cell, lymphocyte, monocyte, or platelet counts was observed. The hemogram and red blood cell count did not show any differences between wild type and Jam-C−/− mice. In summary, we did not observe any difference in blood parameters in the surviving Jam-C−/− mice that could account for the phenotype observed in the neonates.

Table 1.

Genotype of litters of heterozygous breeding pairs

| Genotype expected | JamC+/+ (25%) | JamC+/− (50%) | JamC−/ − (25%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E14.5, no (%) | 10 (23.3) | 21 (48.8) | 12 (27.9) |

| E18.5, no (%) | 8 (26.7) | 14 (46.7) | 8 (26.7) |

| P2, no (%) | 20 (26.7) | 50 (66.7) | 5 (6.7) |

| Total pups, no (%) | 199 (31.6) | 406 (64.5) | 24 (3.8) |

Immunophenotypic analysis of Jam-C−/− mice

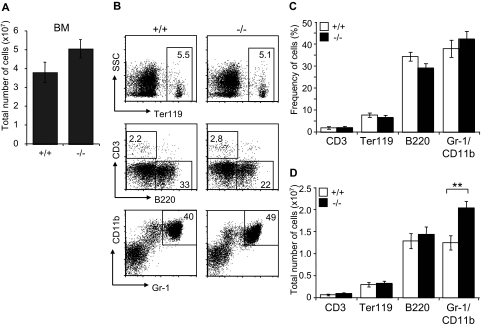

Since JAM-C is expressed on HSCs in the BM, we analyzed the distribution of mature blood cell lineages in the BM of adult surviving mice by flow cytometry. A mild increase in BM cellularity was detected in Jam-C−/− mice when compared with wild-type littermates (P = .057; Figure 4A). The frequency of mature lymphoid and myeloid cells was not different between wild type and Jam-C−/− mice (Figure 4B,C). Analysis of the total number of cells in the BM showed that the number of granulocytes was increased in Jam-C−/− mice (P = .009; Figure 4D), whereas the number of erythroblasts and B cells was not different. No abnormalities were observed in other immunologic tissues when comparing wild-type with Jam-C−/− mice. Mature T and B cells in the spleen were generated normally from HSCs, as were all major thymus subsets (Table S3). Taken together with the complete blood cell count, these data show that loss of JAM-C leads to an increase of granulocytes in the BM and subsequently of neutrophils in the blood, whereas generation of mature B and T cells is not affected.

Figure 4.

Characterization of mature hematopoietic cell populations in Jam-C−/− mice. (A) Total number of mononuclear cells in BM (femur and tibia of both hind legs) of wild-type and homozygous mice (n = 7). (B,C) Frequency of hematopoietic lineages in BM of wild-type and homozygous mice assessed by flow cytometry with antibodies against Ter119 (erythroid lineage), Gr-1 and CD11b (myeloid lineage), and B220 (B-cell lineage). (D) Enumeration of erythroid cells, B cells, and granulocytes in the BM of wild-type and homozygous mice. Shown are representative FACS profiles; the numbers on the plots indicate the frequency of cells in the indicated regions. Bar graphs indicate mean plus or minus SE. Significances are shown on the graph. **P ≤ .01.

Hematopoietic progenitor population in BM of Jam-C−/− mice

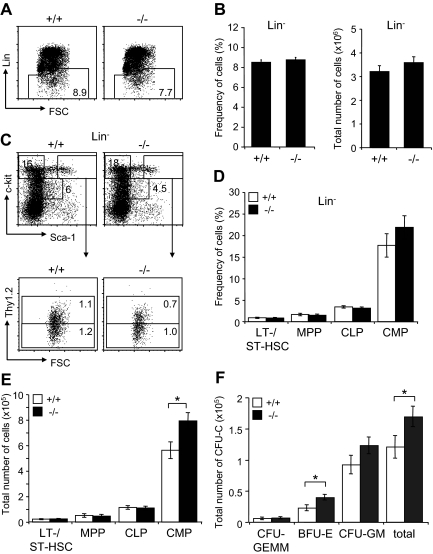

Next, we investigated the effect of Jam-C deficiency on the hematopoietic progenitors present in adult BM. We found the frequency within the BM and total numbers of the lineage-negative population to be normal in surviving Jam-C−/− mice (Figure 5A,B). Analysis of the frequency and total number of LSK cells, including LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and MPPs, did not show any differences between Jam-C−/− and wild-type animals (Figure 5C-E). However, analysis of the total number of BM progenitors showed a significant increase in the number of CMPs (P = .032; Figure 5E). As shown earlier, the myeloid-committed progenitors have the highest percentage of JAM-C–expressing cells among the lineage-committed progenitors (Figure 1F). In contrast, the number of CLPs, which show lower percentages of JAM-C–expressing cells, was not affected in Jam-C−/− mice. Analysis of BM stem cells and progenitors showed that loss of JAM-C leads to an increase in myeloid progenitors, but is otherwise not essential for hematopoiesis.

Figure 5.

Effects of Jam-C deletion on hematopoietic progenitor numbers and activities. Assessment of the frequency (A,B) and total number (B) of lineage-negative cells in the BM of wild-type and homozygous (n = 7) mice. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of LT- and ST-HSCs (Lin−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+Thy1.2+) and progenitors (MPPs: Lin−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+Thy1.2−; CMPs: Lin−, Sca-1−, c-Kit+; CLPs: Lin−, Sca-1int, c-Kitint) contained within the Lin− population. Frequency (D) and total number (E) of stem cells and progenitors in the BM of wild-type and homozygous mice. Shown are representative FACS profiles; the numbers on the plots indicate the frequency of cells in the indicated regions. Bar graphs indicate mean plus or minus SE. (F) Colony-forming ability of BM cells derived from wild-type (n = 5) and homozygous (n = 6) mice cultured in methylcellulose containing mSCF, mIL-3, mIL-6, and hEPO. After 10 days in culture, colonies were assigned scores for the presence of CFU-GEMM, BFU-E, and CFU-GM. Data represent mean plus or minus SE of duplicate plates. Significances are shown on the graph. *P ≤ .05.

In order to compare the colony-formation capacity of myeloid-committed precursors with wild-type and Jam-C−/− mice, we performed colony-forming assays by plating out fresh BM cells in methylcellulose supplemented with growth factors and cytokines. Enumeration of colony growth on day 10 showed that Jam-C−/−–derived cells had higher colony-forming ability than did control cells (P = .034; Figure 5F). This increase is caused by a higher number of erythroid colonies (erythroid burst-forming unit [BFU-E]; P = .045) and possibly granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming units (CFU-G; P = .078), but not by an increase of the most primitive in vitro colony-forming cell, the granulocyte-erythroid-macrophage-megakaryocyte colony-forming unit (CFU-GEMM; P = .92). These results indicate that the loss of JAM-C leads to an increased growth advantage for more mature myeloid progenitors in vitro.

Hematopoietic population in FLs of Jam-C−/− mice

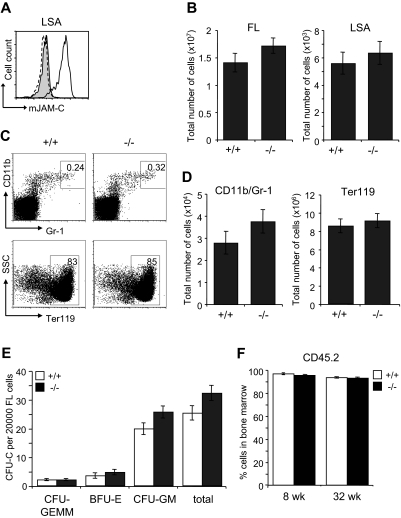

The defect in the BM of Jam-C−/− mice could result from an impaired generation of fetal HSCs, defective migration to the BM or a defective BM environment. We therefore analyzed the HSC compartment in fetal Jam-C−/− mice. During embryonic development, hematopoiesis occurs within the FL. Expansion of the stem cell population occurs between E11 and E15,57,58 after which HSCs begin to migrate from the liver to the BM. HSCs in the FL are called LSA cells, identified by the surface expression of AA4.1 and Sca-1 on lineage-negative cells59,60 (Lin−Sca-1+AA4.1+). JAM-C is highly expressed on LSA cells in the FL at E14.5 by flow cytometry (Figure 6A). Jam-C−/− mice had similar numbers of total FL cells and LSA cells when compared with wild-type littermates (Figure 6B; Table S3). We found no difference in the frequency and total number of mature cells of the myeloid lineage-like erythroblasts (Ter119+) and granulocytes (Gr-1/CD11b+) (Figure 6C,D; Table S3). In summary, we found that Jam-C deficiency does not affect the number of HSCs and mature myeloid cells in the FL, despite the high expression levels on LSA cells.

Figure 6.

Characterization of hematopoietic lineages and progenitors in E14.5 FL. (A) JAM-C expression on E14.5 FL-derived hematopoietic progenitors of wild-type (black histogram line) and homozygous embryos (hatched histogram line) measured by flow cytometry (LSA). Shown is a representative histogram with rabbit serum IgG (filled gray histogram) as control. (B) Total number of cells in E14.5 FL (left plot) and hematopoietic progenitors (LSA cells, right plot) of wild type (n = 12) and homozygous (n = 11) embryos. (C) Frequencies of the different hematopoietic lineages in E14.5 FL of wild-type and homozygous embryos were measured by flow cytometry with antibodies against Gr-1 and CD11b (myeloid lineage) and Ter119 (erythroid lineage). (D) Total number of myeloid and erythroid cells in E14.5 FL of wild-type and homozygous embryos. Shown are representative FACS profiles; the numbers on the plots indicate the frequency of cells in the indicated regions. Bar graphs indicate mean plus or minus SE. (E) Colony-forming ability of E14.5 FL cells derived from wild-type (n = 12) and homozygous (n = 11) embryos cultured in methylcellulose containing mSCF, mIL-3, mIL-6, and hEPO. After 10 days in culture, colonies were assigned scores for the presence of CFU-GEMM, BFU-E, and CFU-GM. Data represent mean plus or minus SE of duplicate plates. (F) Frequency of CD45.2+ donor-derived BM cells 8 and 32 weeks old after the transfer of 2 × 106 FL cells derived from wild-type and homozygous embryos (n = 4 in each group) into lethally irradiated BL6 hosts. Data represent mean plus or minus SE.

To identify functional defects in myeloid-committed progenitors in the FLs of Jam-C−/− mice, we compared their in vitro colony-formation ability. E14.5 FL-derived cells were plated in methylcellulose supplemented with growth factors supporting myeloid growth. Colony counts on day 10 showed a slight increase in CFU-GM (P = .061) and a minor increase in total colonies (P = .074) that was not statistically significant (Figure 6E). Next, we transplanted FL cells into lethally irradiated mice to assess whether there was an intrinsic engraftment defect. FL cells from either Jam-C−/− mice or wild-type littermate controls gave 100% survival. There was no difference in the extent of reconstitution by FL cells between Jam-C−/− mice and wild-type littermate controls (Figure 6F), and all blood cell lineages were equivalent long term (up to week 32; data not shown). These results show that the loss of JAM-C is not vital for myeloid progenitor development in the FL and seeding of the BM. Thus, the increase in myeloid progenitors in the adult BM is not likely to be the result of a developmental defect.

Discussion

In the present study, we show that the cell adhesion molecule JAM-C is highly expressed on HSCs and plays a role in myeloid progenitor generation. Expression levels correlate with self-renewal and are maintained longest among myeloid-committed progenitors. Deletion of Jam-C resulted in an increase in myeloid progenitors and granulocytes in the BM of adult mice. The JAM-C+Lin− population in the BM is composed of HSCs that produce all blood cell lineages long term, and nonrenewing myeloid progenitors in lethally irradiated mice. These results suggest that JAM-C is a cell-surface marker characterizing early progenitors within the BM and is regulating myeloid progenitor differentiation.

In Jam-C−/− mice that survive beyond weaning, the number of stem and progenitor cells was unaltered up to the stage of MPPs, indicating that JAM-C does not control the population size of the stem cell compartment. In contrast, the number of myeloid-committed progenitors was increased, showing that JAM-C is important at the stage of myeloid lineage fate decision. Interestingly, the defect in the Jam-C−/− mice becomes apparent in a cell population that in wild-type animals expresses low levels of the protein. A study has shown that the gene expression program of the myeloid lineages is present in HSCs,12 and that differentiation into the myeloid lineage is permissive.61 Possibly, JAM-C mediates cues from the microenvironment influencing the balance between self-renewal and differentiation. Loss of JAM-C either through deletion of Jam-C or through low expression levels could activate the intrinsic default pathway, leading to an increase in myeloid lineage commitment.

Alternatively, the increase in granulocytes could be caused by a defect in migration, as JAM-C has been implicated in leukocyte migration across endothelial borders.36–38,62 Granulocyte recruitment into peripheral tissue in response to inflammation has been shown to involve JAM-C through its interaction with Mac-1 (αMβ2; CD11b/CD18).18,34,41 In our studies, Jam-C−/− mice show a granulocyte increase in the BM. However, the number of circulating neutrophils is only slightly affected, and no increase in immature neutrophils has been observed in the blood. This indicates that control of granulocyte egress is still functional, and cells are not released from the BM with an immature phenotype. In contrast to published data,56 the degree of neutrophilia is modest, possibly due to the lack of infection in our mice. This is supported by the observation of Imhof et al that the number of circulating neutrophils is higher in moribund mice. Although mice with rescued expression of JAM-C on endothelial cells do not suffer from infections,56 these mice still showed a trend toward increased circulating neutrophils compared with littermate controls. This corresponds to our observation and, possibly, additional defects to the one caused by loss of endothelial JAM-C could influence the number of granulocytes in the BM and subsequently those of circulating neutrophils.

Including JAM-C as a marker on lineage-negative BM cells yields HSC enrichments that are comparable with previously identified markers,48 and transfer of these cells leads to long-term multilineage reconstitution in lethally irradiated mice. The identification of simple combinations of markers that allow reliable identification and purification of the most primitive HSCs are of great interest. A large proportion of the sorted JAM-C+ cells grow in methylcellulose, and the colonies show phenotypes comparable with those grown from LSK cells. Nevertheless, there is a subpopulation of JAM-C+ cells whose growth is not supported in the cytokines provided. JAM-C is expressed on a variety of cell types such as endothelial cells15,17 and fibroblasts19 which could be copurified with lineage-negative BM cells. In contrast to LSK cells, repopulation with JAM-C+ cells leads to a temporary increase in myeloid reconstitution, suggesting that in vivo expansion of the myeloid-committed progenitors contained within the JAM-C+ population is supported. These progenitors are non–self-renewing, leading to a normally sized myeloid compartment at later time points. In summary, JAM-C seems to identify HSCs in the BM that have long-term repopulation potential as well as non–self-renewing myeloid potential.

In summary, our studies provide the first evidence that JAM-C is expressed on HSCs in the BM and plays a role in the differentiation of HSCs into myeloid progenitors. Significantly, JAM-C defines a multipotent stem cell population able to reconstitute all blood cell lineages, and its loss leads to a deregulation of myeloid development. Using JAM-C as sole marker to purify HSCs from lineage-negative BM cells yields HSC enrichments similar to the previously identified markers Sca-1 and c-Kit.48 The transfer of JAM-C+ cells leads to long-term multilineage reconstitution in lethally irradiated mice. Future studies will be needed to identify the specific mechanisms by which JAM-C regulates HSC differentiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rich Erickson and Zhilan Hu for technical support, Stephan Gasser and Robert M. Campbell for scientific discussion, and Christine Olsson, Gerald Pan, Ryan Scott, and Meredith Nunley for animal care.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: A.P. designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the paper; J.M., H.C., L.R., L.C., and W.L. performed research; J.C. designed and performed research; D.D. analyzed and interpreted data; and S.F. supervised design and performance of research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: All authors are either current or past employees of Genentech, Inc, and declare competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Asja Praetor, Lilly-Singapore Centre for Drug Discovery Pte Ltd, 8A Biomedical Grove, No. 02-05 Immunos, Biopolis, Singapore 138648; e-mail: praetor_asja@lilly.com.

References

- 1.Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 2004;116:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore KA, Lemischka IR. Stem cells and their niches. Science. 2006;311:1880–1885. doi: 10.1126/science.1110542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scadden DT. The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature. 2006;441:1075–1079. doi: 10.1038/nature04957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams GB, Chabner KT, Alley IR, et al. Stem cell engraftment at the endosteal niche is specified by the calcium-sensing receptor. Nature. 2006;439:599–603. doi: 10.1038/nature04247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stier S, Cheng T, Dombkowski D, Carlesso N, Scadden DT. Notch1 activation increases hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in vivo and favors lymphoid over myeloid lineage outcome. Blood. 2002;99:2369–2378. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan AW, Rattis FM, DiMascio LN, et al. Integration of Notch and Wnt signaling in hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:314–322. doi: 10.1038/ni1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Priestley GV, Scott LM, Ulyanova T, Papayannopoulou T. Lack of alpha4 integrin expression in stem cells restricts competitive function and self-renewal activity. Blood. 2006;107:2959–2967. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arai F, Hirao A, Ohmura M, et al. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venezia TA, Merchant AA, Ramos CA, et al. Molecular signatures of proliferation and quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akashi K, He X, Chen J, et al. Transcriptional accessibility for genes of multiple tissues and hematopoietic lineages is hierarchically controlled during early hematopoiesis. Blood. 2003;101:383–389. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsberg EC, Prohaska SS, Katzman S, Heffner GC, Stuart JM, Weissman IL. Differential expression of novel potential regulators in hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho AD, Wagner W. The beauty of asymmetry: asymmetric divisions and self-renewal in the haematopoietic system. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:330–336. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3281900f12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aurrand-Lions M, Duncan L, Ballestrem C, Imhof BA. JAM-2, a novel immunoglobulin superfamily molecule, expressed by endothelial and lymphatic cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2733–2741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005458200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arrate MP, Rodriguez JM, Tran TM, Brock TA, Cunningham SA. Cloning of human junctional adhesion molecule 3 (JAM3) and its identification as the JAM2 counter-receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45826–45832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aurrand-Lions M, Johnson-Leger C, Wong C, Du Pasquier L, Imhof BA. Heterogeneity of endothelial junctions is reflected by differential expression and specific subcellular localization of the three JAM family members. Blood. 2001;98:3699–3707. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zen K, Babbin BA, Liu Y, Whelan JB, Nusrat A, Parkos CA. JAM-C is a component of desmosomes and a ligand for CD11b/CD18-mediated neutrophil transepithelial migration. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3926–3937. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris AP, Tawil A, Berkova Z, Wible L, Smith CW, Cunningham SA. Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs) are differentially expressed in fibroblasts and co-localize with ZO-1 to adherens-like junctions. Cell Commun Adhes. 2006;13:233–247. doi: 10.1080/15419060600877978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keiper T, Al-Fakhri N, Chavakis E, et al. The role of junctional adhesion molecule-C (JAM-C) in oxidized LDL-mediated leukocyte recruitment. FASEB J. 2005;19:2078–2080. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4196fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirza M, Hreinsson J, Strand ML, et al. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) is expressed in male germ cells and forms a complex with the differentiation factor JAM-C in mouse testis. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:817–830. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gliki G, Ebnet K, Aurrand-Lions M, Imhof BA, Adams RH. Spermatid differentiation requires the assembly of a cell polarity complex downstream of junctional adhesion molecule-C. Nature. 2004;431:320–324. doi: 10.1038/nature02877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheiermann C, Meda P, Aurrand-Lions M, et al. Expression and function of junctional adhesion molecule-C in myelinated peripheral nerves. Science. 2007;318:1472–1475. doi: 10.1126/science.1149276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santoso S, Sachs UJ, Kroll H, et al. The junctional adhesion molecule 3 (JAM-3) on human platelets is a counterreceptor for the leukocyte integrin Mac-1. J Exp Med. 2002;196:679–691. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson-Leger CA, Aurrand-Lions M, Beltraminelli N, Fasel N, Imhof BA. Junctional adhesion molecule-2 (JAM-2) promotes lymphocyte transendothelial migration. Blood. 2002;100:2479–2486. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamagna C, Meda P, Mandicourt G, et al. Dual interaction of JAM-C with JAM-B and {alpha}M{beta}2 integrin: function in junctional complexes and leukocyte adhesion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4992–5003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santoso S, Orlova VV, Song K, Sachs UJ, Andrei-Selmer CL, Chavakis T. The homophilic binding of junctional adhesion molecule-C mediates tumor cell-endothelial cell interactions. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36326–36333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang TW, Chiu HH, Gurney A, et al. Vascular endothelial-junctional adhesion molecule (VE-JAM)/JAM 2 interacts with T, NK, and dendritic cells through JAM 3. J Immunol. 2002;168:1618–1626. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamagna C, Meda P, Mandicourt G, et al. Dual interaction of JAM-C with JAM-B and alpha(M)beta2 integrin: function in junctional complexes and leukocyte adhesion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4992–5003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunningham SA, Rodriguez JM, Arrate MP, Tran TM, Brock TA. JAM2 interacts with alpha4beta1: facilitation by JAM3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27589–27592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200331200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebnet K, Aurrand-Lions M, Kuhn A, et al. The junctional adhesion molecule (JAM) family members JAM-2 and JAM-3 associate with the cell polarity protein PAR-3: a possible role for JAMs in endothelial cell polarity. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3879–3891. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reymond N, Garrido-Urbani S, Borg JP, Dubreuil P, Lopez M. PICK-1: a scaffold protein that interacts with Nectins and JAMs at cell junctions. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2243–2249. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orlova VV, Economopoulou M, Lupu F, Santoso S, Chavakis T. Junctional adhesion molecule-C regulates vascular endothelial permeability by modulating VE-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contacts. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2703–2714. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chavakis T, Keiper T, Matz-Westphal R, et al. The junctional adhesion molecule-C promotes neutrophil transendothelial migration in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55602–55608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller WA. Leukocyte-endothelial-cell interactions in leukocyte transmigration and the inflammatory response. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber C, Fraemohs L, Dejana E. The role of junctional adhesion molecules in vascular inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:467–477. doi: 10.1038/nri2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chavakis T, Preissner KT, Santoso S. Leukocyte trans-endothelial migration: JAMs add new pieces to the puzzle. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bazzoni G. The JAM family of junctional adhesion molecules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:525–530. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ebnet K, Suzuki A, Ohno S, Vestweber D. Junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs): more molecules with dual functions? J Cell Sci. 2004;117:19–29. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vonlaufen A, Aurrand-Lions M, Pastor CM, et al. The role of junctional adhesion molecule C (JAM-C) in acute pancreatitis. J Pathol. 2006;209:540–548. doi: 10.1002/path.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aurrand-Lions M, Lamagna C, Dangerfield JP, et al. Junctional adhesion molecule-C regulates the early influx of leukocytes into tissues during inflammation. J Immunol. 2005;174:6406–6415. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ludwig RJ, Zollner TM, Santoso S, et al. Junctional adhesion molecules (JAM)-B and -C contribute to leukocyte extravasation to the skin and mediate cutaneous inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer G, Busso N, Aurrand-Lions M, et al. Expression and function of junctional adhesion molecule-C in human and experimental arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R65. doi: 10.1186/ar2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langer HF, Daub K, Braun G, et al. Platelets recruit human dendritic cells via Mac-1/JAM-C interaction and modulate dendritic cell function in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1463–1470. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lamagna C, Hodivala-Dilke KM, Imhof BA, Aurrand-Lions M. Antibody against junctional adhesion molecule-C inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5703–5710. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandicourt G, Iden S, Ebnet K, Aurrand-Lions M, Imhof BA. JAM-C regulates tight junctions and integrin-mediated cell adhesion and migration. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1830–1837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Satohisa S, Chiba H, Osanai M, et al. Behavior of tight-junction, adherens-junction and cell polarity proteins during HNF-4alpha-induced epithelial polarization. Exp Cell Res. 2005;310:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okada S, Nakauchi H, Nagayoshi K, Nishikawa S, Miura Y, Suda T. In vivo and in vitro stem cell function of c-kit- and Sca-1-positive murine hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1992;80:3044–3050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikuta K, Weissman IL. Evidence that hematopoietic stem cells express mouse c-kit but do not depend on steel factor for their generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1502–1506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kondo M, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell. 1997;91:661–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright DE, Wagers AJ, Gulati AP, Johnson FL, Weissman IL. Physiological migration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Science. 2001;294:1933–1936. doi: 10.1126/science.1064081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwarz BA, Bhandoola A. Circulating hematopoietic progenitors with T lineage potential. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:953–960. doi: 10.1038/ni1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adolfsson J, Borge OJ, Bryder D, et al. Upregulation of Flt3 expression within the bone marrow Lin(-)Sca1(+)c-kit(+) stem cell compartment is accompanied by loss of self-renewal capacity. Immunity. 2001;15:659–669. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christensen JL, Weissman IL. Flk-2 is a marker in hematopoietic stem cell differentiation: a simple method to isolate long-term stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14541–14546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261562798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Imhof BA, Zimmerli C, Gliki G, et al. Pulmonary dysfunction and impaired granulocyte homeostasis result in poor survival of Jam-C-deficient mice. J Pathol. 2007;212:198–208. doi: 10.1002/path.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ema H, Nakauchi H. Expansion of hematopoietic stem cells in the developing liver of a mouse embryo. Blood. 2000;95:2284–2288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morrison SJ, Hemmati HD, Wandycz AM, Weissman IL. The purification and characterization of fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10302–10306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jordan CT, Astle CM, Zawadzki J, Mackarehtschian K, Lemischka IR, Harrison DE. Long-term repopulating abilities of enriched fetal liver stem cells measured by competitive repopulation. Exp Hematol. 1995;23:1011–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jordan CT, McKearn JP, Lemischka IR. Cellular and developmental properties of fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 1990;61:953–963. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90061-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Graf T. Determinants of lymphoid-myeloid lineage diversification. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:705–738. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chavakis T, Orlova V. The role of junctional adhesion molecules in interactions between vascular cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;341:37–50. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-113-4:37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.