Abstract

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) dysregulation is implicated in the two Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathological hallmarks: β-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. GSK-3 inhibitors may abrogate AD pathology by inhibiting amyloidogenic γ-secretase cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP). Here, we report that the citrus bioflavonoid luteolin reduces amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide generation in both human ‘Swedish’ mutant APP transgene-bearing neuron-like cells and primary neurons. We also find that luteolin induces changes consistent with GSK-3 inhibition that (i) decrease amyloidogenic γ-secretase APP processing, and (ii) promote presenilin-1 (PS1) carboxyl-terminal fragment (CTF) phosphorylation. Importantly, we find GSK-3α activity is essential for both PS1 CTF phosphorylation and PS1-APP interaction. As validation of these findings in vivo, we find that luteolin, when applied to the Tg2576 mouse model of AD, decreases soluble Aβ levels, reduces GSK-3 activity, and disrupts PS1-APP association. In addition, we find that Tg2576 mice treated with diosmin, a glycoside of a flavonoid structurally similar to luteolin, display significantly reduced Aβ pathology. We suggest that GSK-3 inhibition is a viable therapeutic approach for AD by impacting PS1 phosphorylation-dependent regulation of amyloidogenesis.

Introduction

Amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide generation and aggregation as plaques are key pathological events in the development of Alzheimer's disease (AD) [1–5]. Aβ peptides and plaques have been extensively studied and evidenced to be neurotoxic, as they are reported mediators of apoptosis [6, 7], inflammation [8, 9] and oxidative stress [10, 11]. For this reason, some of the earliest proposed therapeutic strategies entail the prevention or elimination of these Aβ peptides and subsequent deposits. Aβ peptides are produced via the amyloidogenic pathway of amyloid precursor protein (APP) proteolysis, which involves the concerted effort of β and γ-secretases [5, 12]. Initially, β-secretase (BACE) cleaves APP, creating an Aβ-containing carboxyl-terminal fragment known as β-C-terminal fragment (β-CTF), or C99 [13–15]. This proteolysis also generates an amino-terminal, soluble APP-β (sAPP-β) fragment, which is released extracellularly. Intracellularly, β-CTF is then cleaved by a multi-protein γ-secretase complex that results in generation of the Aβ peptide and a smaller γ-CTF, also known as C57 [16, 17]. While both cleavage events are essential to the formation of the peptide, it is the γ-secretase cleavage that determines which of the two major forms of the peptide (Aβ1–40, 42) will be generated and consequently both the peptide's ability to aggregate and the rate at which it is deposited [18, 19]. Thus, one clear potential therapeutic target for AD has been γ-secretase.

Despite the potential toxicity involving possible disruption of Notch signalling and intracellular accumulation of β-CTFs, γ-secretase inhibition remains a viable anti-amyloidogenic strategy [20, 21]. In addition to previous reports that novel γ-secretase inhibitors (GSI) significantly reduced Aβ production both in vitro and in vivo[22–26], Comery et al. recently reported that similar GSIs may even improve cognitive functioning in a transgenic mouse model of AD (Tg2576) [27]. These findings have functioned to further the vigorous search for potential candidate GSIs. Among the many, promising potential candidates are the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) inhibitors. These compounds target this tonically active serine/threonine kinase, which has been implicated in several disorders of the CNS [28–31]. With regard to AD, both isoforms of GSK-3 (α and β) have been found to directly phosphorylate tau on residues specific to hyperphosphorylated paired helical filaments (PHF) [32], GSK-3β has been shown to phosphorylate APP and to contribute to Ap–mediated neurotoxicity [33–35], and GSK-3β has been found to phosphorylate PS1, which may act as a docking site for subsequent tau phosphorylation [36]. Therefore, GSK-3 inhibitors are especially attractive as they may not only oppose Aβ generation but also neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) formation. Moreover, Phiel et al. reported that inhibition of the GSK-3α isoform may regulate γ-secretase cleavage of APP in a substrate-specific manner [37]. Accordingly, this selective inhibition of GSK-3 might provide the maximal therapeutic benefit while reducing the potential for toxic side effects.

The intense search for small-molecular compounds that may modulate AD pathology has advanced the analysis of specific dietary derived substances from fruits and vegetables, which epidemiological study suggest are beneficial against the neurodegeneration and aging processes [38, 39]. In this light, recent focus has been given to a group of polyphenols categorized as flavonoids, which have been found to be potentially anti-amyloidogenic [40–42]. In the present study, we demonstrate that treatment of both murine N2a cells transfected with the human ‘Swedish’ mutant form of APP (SweAPP N2a cells) and primary neuronal cells derived from Alzheimer's ‘Swedish’ mutant APP overexpressing mice (Tg2576 line; [43]) with the flavonoid luteolin results in a significant reduction in Aβ generation. Furthermore, data show that luteolin treatment apparently achieves this reduction through a selective inactivation of the GSK-3α isoform. As in vivo validation, we find that administration of luteolin and a glycoside of a structurally similar flavonoid, diosmin, to Tg2576 mice similarly reduces Aβ generation potentially through GSK-3 inhibition. Importantly, this reduction in GSK-3 activation increases phosphorylation of presenilin 1 (PS1), which forms the catalytic core of the γ-secretase complex, and may suggest a mechanism whereby these small-molecular compounds (GSK-3 inhibitors) modulate AD pathology.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Luteolin (>95% purity by HPLC) was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Diosmin (>90% purity by HPLC) was purchased from Axxora (San Diego, CA, USA). GSK-3 inhibitor was obtained from BIOMOL® (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) was purchased from Fermentas (Hanover, MD, USA). Antibodies against the amino-terminus and carboxyl-terminus of PS1 were obtained from Chemicon (Temecula, CA, USA), and those against the amino-terminus and carboxyl-terminus of APP (22C11) and against actin were purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Antibodies against Aβ, including 6E10, 48G, were obtained from Covance Research Products (Emeryville, CA, USA). Antibody against phosphor-GSK3α (ser21, clone BK202) was obtained from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY, USA). Antibodies against phospho-GSK3α/β (pTyr279/216), phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9) and total GSK-3α/β were purchased from Sigma. Aβ1–40, 42 ELISA kits were obtained from IBL-American (Minneapolis, MN, USA). γ-secretase activity kit was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Pre-designed siRNA against murine GSK-3α or β and Code-Breaker transfection reagent were purchased from Dharmacon, Inc. (Lafayette, CO, USA) and Promega (Madison, WI, USA), respectively.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation

Cultured cells were lysed in ice-cold-lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% v/v Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyropgosphate, 1 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF) as previously described [41]. Mouse brains were isolated under sterile conditions on ice and placed in ice-cold lysis buffer. Brains were then sonicated on ice for approximately 3 min., allowed to stand for 15 min. at 4°C and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min. Following sample preparation, an aliquot corresponding to 50 μg of total protein was electrophoretically separated using 12% Tris-HCl or 16.5% Tris-tricine gels. Electrophoresed proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes, washed in dH2O and blocked for 1 hr at ambient temperature in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA) containing 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk. After blocking, membranes were hybridized for 1 hr at ambient temperature with various primary antibodies. Membranes were then washed 3× for 5 min. each in dH2O and incubated for 1 hr at ambient temperature with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000). All antibodies were diluted in TBS containing 5% (w/v) of non-fat dry milk. Blots were developed using the luminol reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). Densitometric analysis was done as previously described using a FluorS Multiimager with Quantity One™ software (Bio-Rad) [41]. Immunoprecipitation was performed for detection of sAPP-α, sAPP-β and Aβ by incubating 200 μg of total protein of each sample from media with various sequential combinations of 6E10 (1:100) and/or 22C11 (1:100) antibodies overnight with gentle rocking at 4°C. Co-immunoprecitipation was performed for detection of APP bound to PS1 CTF by incubating 400 μg of total protein from cell lysates with PS1 CTF antibody (1:50) overnight with gentle rocking at 4°C. Ten microlitre of 50% protein A-Sepharose beads was then added to each sample (1:10; Sigma) prior to gentle rocking for an additional 4 hrs at 4°C. Following washes with 1 × cell lysis buffer, samples were subjected to Western blot as described above. Antibodies used for Western blot included the APP-carboxyl-terminal antibody (1:50), amino-terminal APP antibody (clone 22C11), or 6E10 (1:1000), actin antibody (1:1500; as an internal reference control) or IgG (1:1500 as an internal reference control).

γ-secretase activity assay

γ-secretase activity was quantified in cell lysates using an R& Systems kit based on secretase-specific substrates conjugated to fluorogenic reporter molecules (EDANS/DABCYL) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cultured cells were lysed in ice-cold 1 × cell extraction buffer for 10 min. and subsequently centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 1 min.

Appropriate amounts of cell lysate, reaction buffer and flurogenic substrate were added in duplicate to a 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C for various periods of time. Following incubation, fluorescence was monitored (excitation at 335 nm and emission at 495 nm) at 25°C by using a Molecular Devices SPECTRAmax GEMINI plate reader. Fluorogenic background was adjusted using appropriate controls (no cell lysate and no fluorogenic substrate).

ELISA

Mouse brains were isolated under sterile conditions on ice and placed in ice-cold lysis buffer. Brains were then sonicated on ice for approximately 3 min., allowed to stand for 15 min. at 4°C and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min. Aβ1–40, 42 species were detected by acid extraction of brain homogenates in 5 M guanidine buffer [41], followed by a 1:10 dilution in lysis buffer. Soluble Aβ1–40, 42 were directly detected in cultured cell media or brain homogenates prepared with lysis buffer described above by a 1:4 or 1:10 dilution, respectively. Aβ1–40, 42 was quantified in these samples using the Aβ1–40, 42 ELISA kits (IBL-America) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, except that standards included 0.5 M guanidine buffer in some cases.

RNA interference

SweAPP N2a cells were transfected with siRNA pre-designed to knockdown murine GSK-3α or β (Dharmacon Inc., Lafayette, CO, USA). SweAPP N2a cells were seeded in 24-well plates and cultured until they reached 70% confluence. The cells were then either mock transfected or transfected with 50–200 nM anti-GSK-3α or β siRNA using Code-Breaker transfection reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and cultured for an additional 18 hrs in serum-free MEM. Transfection efficiency was determined to be greater than 70% (data not shown). The cells were allowed to recover for 24 hrs in complete medium (MEM 10% FBS) before treatments. The cells were subsequently evaluated by Western blot analysis for expression of PS1 CTF.

Mice

Tg2576 were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY, USA). For intraperitoneal administration of luteolin, a total of 16 (8♂/8♀) Tg2576 mice were used; 8 mice received luteolin and the other 8 received phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Beginning at 8 months of age, these Tg2576 mice were intraperitoneally injected with luteolin (20 mg/kg) or PBS daily for 30 days based on previously described methods [41]. These mice were then sacrificed at 9 months of age for analyses of Aβ levels and Aβ load in the brain according to previously described methods [44]. For oral administration of diosmin, a total of 20 (10♂/10♀) Tg2576 mice were used; 10 mice received a diet containing 0.05% diosmin in standard mouse chow (7012, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI, USA) and the other 10 received the standard diet alone. Beginning at 8 months of age, these Tg2576 mice consumed both diets ad libitum for 6 months. These mice were then sacrificed at 14 months of age for analyses of Aβ levels and Aβ load in the brain according to previously described methods [44]. Animals were housed and maintained in the College of Medicine Animal Facility at the University of South Florida (USF), and all experiments were in compliance with protocols approved by the USF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Primary neuronal culture

Cerebral cortices were isolated from Tg2576 mouse embryos, between 15 and 17 days in utreo, cortices were mechanically dissociated in trypsin (0.25%) individually after incubation for 15 min. at 37°C. Cells were collected after centrifugation at 1200 rpm, resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum, 10% horse serum, uridine (33.6 μg/ml; Sigma) and fluorodeoxyuridine (13.6 μg/ml; Sigma), seeded in 24-well collagen coating culture plates at 2.5 × 105 cells per well. When neuronal cells were isolated from Tg2576 mice to verify human APPsw mutant status, genotyping PCR analysis was performed as previously described [44] and human APPsw mutant gene was detected in these cells (data not shown).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anaesthetized with isofluorane and transcardinally perfused with ice-cold physiological saline containing heparin (10 U/ml). Brains were rapidly isolated and quartered using a mouse brain slicer. The first and second anterior quarters were homogenized for Western blot analysis, and the third and fourth posterior quarters were used for microtome or cryostat sectioning. Brains were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C overnight and routinely processed in paraffin in a core facility at the Department of Pathology (USF College of Medicine). Five coronal sections from each brain (5-μm thickness) were cut with a 150-μm interval. Sections were routinely deparaffinized and hydrated in a graded series of ethanol prior to pre-blocking for 30 min. at ambient temperature with serum-free protein block. GSK-3α/β immunohistochemical staining was performed using anti-phospho-GSK-3/α/β (pTyr279/216) antibody (1:50) in conjunction with the VectaStain Elite™ ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) coupled with diaminobenzidine substrate. Phospho-GSK-3α/β-positive neuronal cells were examined under bright-field using an Olympus BX-51 microscope. Aβ immunohistochemical staining was performed using anti-human amyloid-β antibody (4G8) in conjunction with the VectaStain Elite ABC kit coupled with diaminobenzidine substrate. β-amyloid plaques positive for 4G8 were visualized under bright field using an Olympus BX-51 microscope. Aβ burden was determined by quantitative image analysis. Briefly, images of five 5-μm sections (150 μm apart) through each anatomic region of interest (hippocampus and neocortex) were captured and a threshold optical density was obtained that discriminated staining form background. Manual editing of each field was used to eliminate artifacts. Data are reported as percentage of immunolabelled area captured (positive pixels divided by total pixels captured). Quantitative image analysis was performed by a single examiner (TM) blinded to sample identities [1].

Statistical analysis

All data were normally distributed; therefore, in instances of single mean comparisons, Levene's test for equality of variances followed by t-test for independent samples was used to assess significance. In instances of multiple mean comparisons, ANOVA was used, followed by post hoc comparison using Bonferonni's method. Alpha levels were set at 0.05 for all analyses. The statistical package for the social sciences release 10.0.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all data analysis.

Results

Luteolin inhibits Aβ1–40, 42 generation from SweAPP N2a cells and Tg2576 mouse-derived primary neuronal cells

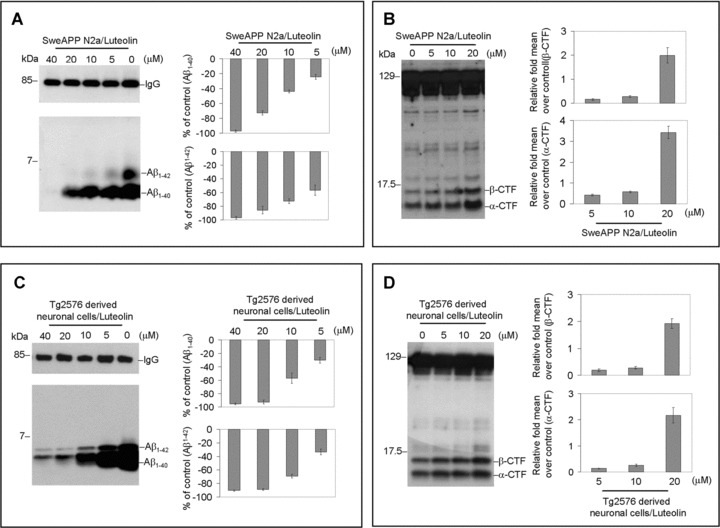

To examine the effect luteolin has on APP proteolysis, we first treated SweAPP N2a cells and primary neuronal cells derived from Tg2576 mice with a wide range of concentrations. Following a series of analyses, of which involved immunoprecipitation, Western blot and ELISA, we found that luteolin effectively reduced both Aβ1–40, 42 production in either cell line in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A and C). In fact, results indicate that luteolin markedly abolished generation of both Aβ peptides with >70% and >85% reductions at treatment concentrations of 20 and 40 μM, respectively (Fig. 1A and C). Furthermore, to determine at which level luteolin impacts amyloid processing, we looked at the CTF profiles of both SweAPP N2a and primary Tg2576-derived neuronal cells following treatment. As illustrated in Fig. 1B and D, Western blot analysis shows a concentration-dependent accumulation of both α and β CTFs, approximately two- to three-fold increases in either cell line. Given the obvious implications on γ-secretase activity, we analysed what effect luteolin treatment had on SweAPP N2a cells using a fluorometric assay for γ-cleavage. In accordance with expectations, luteolin lowered γ-secretase cleavage activity in both a concentration and time-dependent fashion (Fig. 1E and F). More importantly, these concentration and time-dependent decreases in γ-secretase cleavage activity correlate with the decreases in total Aβ generation (Fig. 1E and F). Taken together, the above data suggest that luteolin exerts its anti-amyloidogenic effects through down-regulation of γ-secretase activity.

1.

Luteolin reduces Aβ generation and decreases γ-secretase cleavage activity in cultured neuronal cells. SweAPP N2a cells (A, B) or Tg2576 derived neuronal cells (C, D) were treated with luteolin at various concentrations as indicated for 12 hrs. For A, C, Secreted Aβ1–40, 42 peptides were analysed by immunoprecipitation/Western blot (right) and ELISA (left; n= 3 for each condition) in conditional media. For Aβ ELISA, data are represented as a percentage of Aβ1–40, 42 peptides secreted 12 hrs after luteolin treatment relative to control (untreated). (B, D) APP CTFs were analysed by Western blot (right) in cell lysates and relative fold mean over control (α, β-CTF) was calculated by Densitometry analysis (left). (A-D) One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc comparison revealed significant differences between each concentration (P < 0.005) except between 20 μM and 40 μM (P > 0.05). SweAPP N2a cells were treated with luteolin at a single concentration (20 μM) for various time-points as indicted. (E) Secreted Aβ1–40, 42 peptides were analysed in conditional media by ELISA following 12 hrs of incubation (top panel; n= 3 for each condition) and γ-secretase activity was analysed in cell lysates following 90 min. of incubation using secretase cleavage activity assay (lower panel; n= 3 for each condition). For (E), data presented as a percentage of fluorescence units/milligrams protein activated 30, 60, 90, 120, 300 min. after luteolin treatment relative to control (untreated). (E) A difference was noted between each time-point examined (P < 0.005). In parallel, we employed a similar structure compound, apigenin, as control. However, we did not observe similar results as luteolin (data not shown).

Luteolin reduces GSK-3α/β activation in SweAPP N2a cells and Tg2576 mouse-derived primary neuronal cells

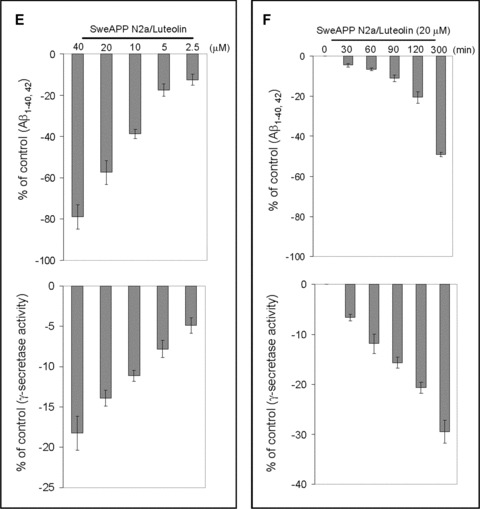

To establish the mechanism whereby luteolin modulates γ-secretase activity and subsequent Aβ generation, we evaluated the effect this compound had on a variety of proteins related to and/or required for proper functioning of the γ-secretase complex. Interestingly, we found that luteolin (20 μM) increased levels of serine 21 phosphorylated inactive GSK-3α isoforms in both SweAPP N2a and primary Tg2576-derived neuronal cells (Fig. 2). However, we did not observe any significant changes in overall expression of either GSK3-α or β by Western blot, confirming that this phenomenon most likely occurs at the post-translational or protein stage of this kinase (Fig. 2). In addition, this increase in GSK-3α serine 21 residue phosphorylation-mediated inactivation continued through 3 hrs (Fig. 2B and E). At the same time, it is evident that levels of tyrosine 279 phosphorylated active GSK-3α isoforms decreased in time-dependent manner (Fig. 2B and E). More to the point, these time-dependent decreases in phospho-tyrosine 279 active GSK-3α are quite congruent with the increases we see with phospho-serine 21 inactive isoforms (Fig. 2). Figure 2C and F clearly indicates abrupt decreases in active phosphorylated isoforms and increases in inactive phosphorylated isoforms within 60 min. of luteolin treatment. Also notable, following 2 hrs of treatment, levels of phospho-tyrosine 216 active GSK-3β drop off, which may also explain, in part, the luteolin-mediated effects on the γ-secretase complex via PS1. Although luteolin clearly affects that of GSK-3α, no such significant changes in phospho-serine 9 GSK-3β inactivation were detected. Therefore, when considering the above data, it is apparent that luteolin affects GSK-3α/β signalling and confirms that this signalling is a potential upstream event required for modulation of γ-secretase activity.

2.

Luteolin reduces GSK-3α activation. SweAPP N2a cells (A, B, C) or Tg2576-derived neuronal cells (D, E, F) were treated with luteolin at 20 μM for various time-points as indicated. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis in phosphorylated forms of GSK-3α/β. For (A, D), Western blot analysis using anti-phospho-GSK-3α (Ser21) antibody shows one band (51 kD) corresponding to phosphorylated form of GSK-3α or using anti-GSK-3 monoclonal antibody recognizes both total GSK-3α and GSK-3β, 51 and 47 kD, respectively. Western blot analysis using anti-actin antibody shows actin protein (as an internal reference control). Densitometry analysis shows the ratio of phospho-GSK-3α (Ser21) to total GSK-3α as indicated below the figures (n= 3 for each condition). (A, D) One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc comparison revealed a significant difference between 0 min. and 5, 10, 15, 20 or 25 min. (P < 0.001). For (B, E), Western blot analysis using anti-phospho-GSK-3α/β(Tye279/216) antibody shows two bands (51 and 47 kD) corresponding to phosphorylated forms of GSK-3α and GSK-3β or using anti-phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9) antibody recognizes phosphorylated form of GSK-3B at 47 kD. Anti-actin antibody was used as shows an internal reference control. Densitometry analysis shows the ratio of phospho-GSK-3α (Tye279/216) to total GSK-3α as indicated below the figures (n= 3 for each condition). (B, E) One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc comparison significant difference was noted between 30 min. and 45, 60, 75, 90, 120, 150 or 180 min. (P < 0.005). For (C, F), plots comparing ratios of phospho-GSK-3α (Ser21) and phospho-GSK-3α/β(Tye279/216) to total GSK-3α from densitometic analysis of Western blots over time.

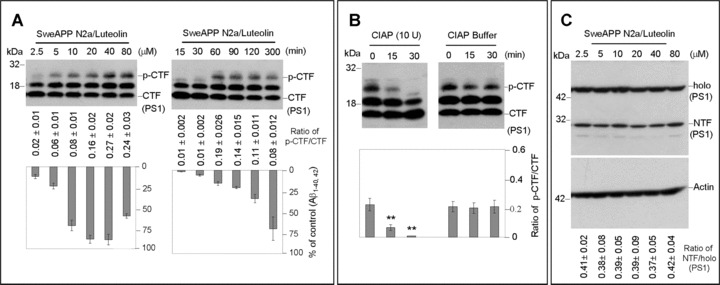

GSK-3 inhibition alters PS1 processing/phosphorylation in SweAPP N2a cells

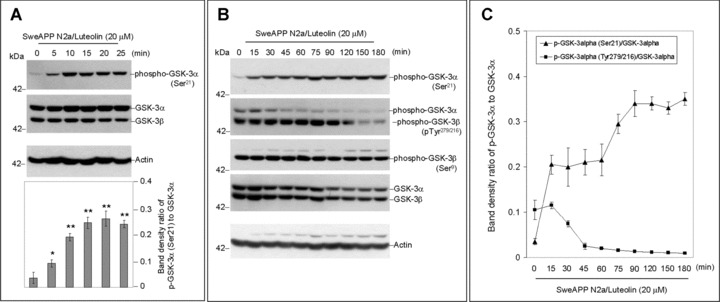

As indicated by Fig. 3A-C, Western blot analysis of carboxyl-terminal portions of PS1 reveals three distinct bands. The two bands of highest molecular weight, approximately 20 kD and 18 kD in size, most likely represent previously reported phosphorylated PS1 CTFs with the smaller 16-kD band representing the more common CTF product indicative of PS1 endoproteolytic cleavage. Following treatment of SweAPP N2a cells with various concentration of luteolin, we found that PS1 CTF phosphorylation increases. We observed significant differences in phospho-PS1 CTF:PS1 CTF ratios with luteolin treatment, both concentration and time-dependently (Fig. 3A). More to the point, these trends correlated with the concentration and time-dependent decreases in Aβ1–40, 42 generation. To confirm that the 20-kD and 18-kD bands were representative of phosphorylated PS1 isoforms, we treated SweAPP N2a cells with luteolin (20 μM) prior to lysis and subsequently incubated cell lysates with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) to dephosphorylate any potential phosphorylated proteins, which consequently have skewed electrophorectic mobilities. Indeed, following 30 min. of incubation, the 20-kD band is not evident in the CIAP treated lysates (Fig. 3B). Also, the 18-kD band is clearly reduced and the endogenous CTF, 16 kD, appears to accumulate. When compared to lysates incubated with only reaction buffer, we see time-dependent decreases in phosphorylated residues by ratios of the 20-kD CTF:16-kD CTF (Fig. 3B). While luteolin treatment influenced PS1 CTF species, this compound had no significant effect on either full-length PS1 or PS1 NTF protein levels (Fig. 3C). Luteolin therefore appears to affect PS1 phosphorylation and may indicate a means by which γ-secretase activity may be regulated.

3.

PS1 phosphorylation is associated with luteolin-mediated inhibition of Aβ generation. SweAPP N2a cells were treated with luteolin at a range of concentrations for 4 hrs or at 20 μM for various time-points as indicated. Cell lysates were prepared from these cells and subjected to Western blot analyses of PS1 C-terminal fragments (CTF) (A) and N-terminal fragment (NTF) (C). Western blot analysis by anti-PS1 CTF antibody shows two bands corresponding to phosphorylated PS1 CTF (p-CTF) and one dephosphorylated PS1 CTF (CTF). While Western blot analysis by anti-PS1 CTF antibody shows tow bands corresponding to holo PS1 and PS1 NTF. For (B), cell lysates from luteolin treated cells (20 μM) were incubated with calf-intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) or buffer for various time-points. Western blot analysis by anti-PS1 CTF antibody confirms two higher molecular weight bands corresponding to phosphorylated isoforms. Densitometry analysis shows the ratio of PS1 p-CTF to CTF below figures. A t-test revealed a significant deference between luteolin concentrations and time-points for ratio of PS1 p-CTF to CTF (P < 0.005 with n= 3 for each condition, but not for ratio of holo PS1 to PS1 NTF (P > 0.05 with n= 3 for each condition) at each time-point examined. Cultured media were collected for Aβ ELISA. Data correspond to percentage of Aβ1–40, 42 peptides secreted 4 hrs after luteolin treatment relative to control (untreated) as indicated below panel (A).

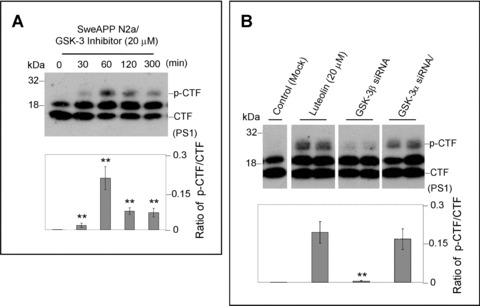

To determine if this phenomenon was specifically attributable to luteolin treatment or more generally in regards to GSK-3 inhibition, we treated SweAPP N2a cells with GSK-3 inhibitor SB-415286 over a range of concentrations (Fig. 4A). Again, we observed similar decreases in Aβ1–40, 42 generation (data not shown) and alterations in phospho-PS1 CTF:PS1 CTF ratios with SB-415286 treatment (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, to substantiate the role of GSK-3α in this luteolin-mediated PS1 processing, we successfully knocked down (>70%, data not shown) GSK-3α and β with siRNA in SweAPP N2a cells. As expected, GSK-3α siRNA transfected cells exhibit significantly higher phosphorylated PS1 isoforms as compared to GSK-3β siRNA or mock transfectants (Fig. 4B; P < 0.001). We also observed similar differences when comparing the level of PS1 phosphorylation in luteolin treated (20 μM) cells to that of GSK-3β siRNA or mock trans-fectants (Fig. 4B; P < 0.001). These data suggest that GSK-3α may regulate PS1 CTF phosphorylation and additionally that this 20-kD phospho-PS1 CTF band may represent a less active or non-amyloidogenic form of γ-secretase.

4.

GSK-3α regulates PS1 phosphorylation. For (A), SweAPP N2a cells were treated with a known GSK-3 inhibitor (SB-415286) at 20 μM for various time-points. Western blot analysis by anti-PS1 CTF antibody produces a similar phosphorylation profile to that of luteolin-treated cells. Densitometry analysis shows the ratio of PS1 p-CTF to CTF and ratio of holo PS1 to actin as indicated below the figures. A t-test revealed significant differences between time-points for the ratio of PS1 p-CTF to CTF (P < 0.001 with n= 3 for each condition). For (B), expression of PS1 C-terminal fragments was analysed by Western blot in cell lysates from SweAPP N2a cells transfected with siRNA targeting GSK-3α, β, or mock transfected 48 hrs after transfecion. Prior to experiments, siRNA knockdown efficiency >70% for GSK-3α, β was confirmed by Western blot analysis (data not shown). Densitometric analysis reveals the ratio of PS1 p-CTF to CTF as indicated below the each panel. A t-test revealed significant differences between GSK-3α siRNA-trans-fected cells and GSK-3β siRNA or control (Mock transfected cells) (P < 0.001 with n= 4 for each condition) on the ratio of PS1 p-CTF to CTF. In addition, a t-test also revealed significant differences between luteolin-treated cells and GSK-3β siRNA or control (Mock transfeced cells) (P < 0.001 with n= 4 for each condition) on the ratio of PS1 p-CTF to CTF.

GSK-3α regulates PS1-APP association in SweAPP N2a cells

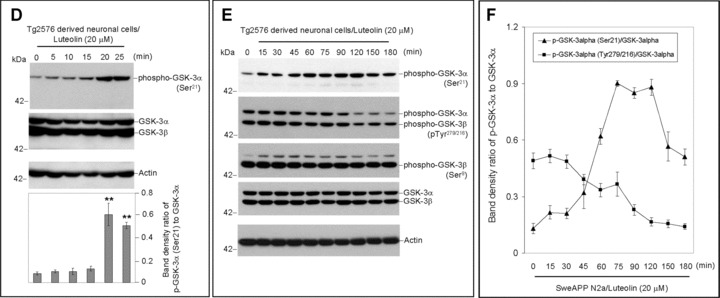

Although previous study has linked GSK-3 inhibitors to reduced Aβ generation through the γ-secretase complex [37], the manner in which this complex's activity is affected remains unclear. To clarify how phospho-PS1 CTF isoforms may regulate γ-secretase activity, cell lysates of treated SweAPP N2a cells were immuno-precipitated by PS1 antibody and probed for APP (Fig. 5). As illustrated in Fig. 5A, the APP-PS1 association is significantly disrupted by not only luteolin and SB-415286 treatment, but also by GSK-3α siRNA. Moreover, this treatment-mediated disruption has no correlation to full-length APP levels (Fig. 5B). This analysis suggests that treatment has little effect on APP expression/trafficking. Thus, it is likely that GSK-3α or, more specifically, downstream phosphorylation of the PS1 CTF plays an essential role in regulating the association of γ-secretase complex with its APP substrate.

5.

GSK-3α regulates PS1-APP association. SweAPP N2a cells were treated with either luteolin (20 μm) or SB-415286 (20 μm) for 4 hrs. Cell lysates from these treated cells and GSK-3α siRNA-transfected cells were subsequently analysed by immunoprecipitation/ Western blot. For (A), lysates were immunoprecipitated by anti-PS1 CTF antibody. Densitometric analysis of Western blot by 6E10 antibody shows the ratio of APP to IgG as indicated below panel (A). A t-test revealed significant differences between all treatments and control (P < 0.001 with n= 3 for each condition). For (B), cell lysates were analysed by Western blot by 6E10 antibody. Densitometric analysis of Western blot by anti-actin antibody reveals no significant changes in the ratio of APP to actin as indicated below panel (B) (P > 0.05).

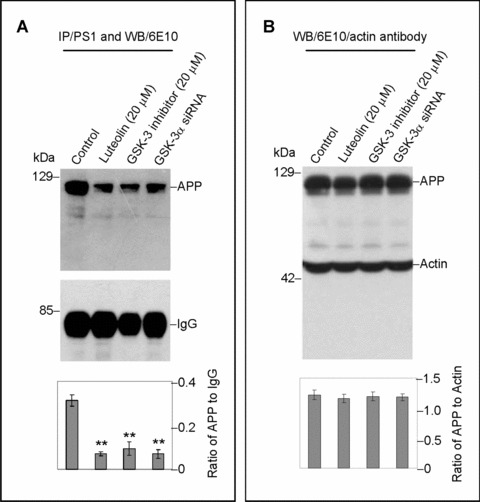

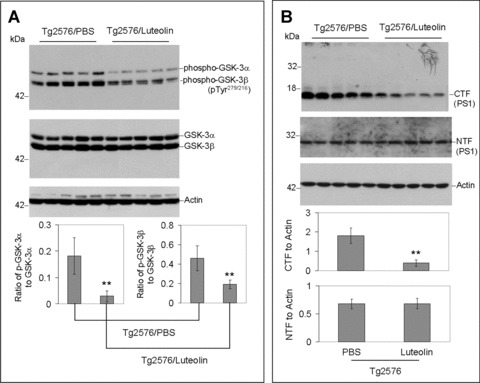

Luteolin reduces GSK-3 activation and results in reduction of cerebral Aβ levels in Tg2576 mice

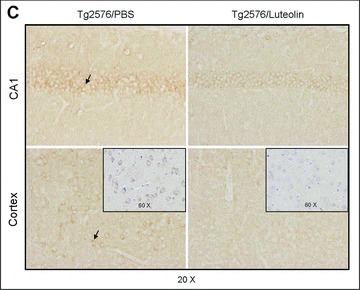

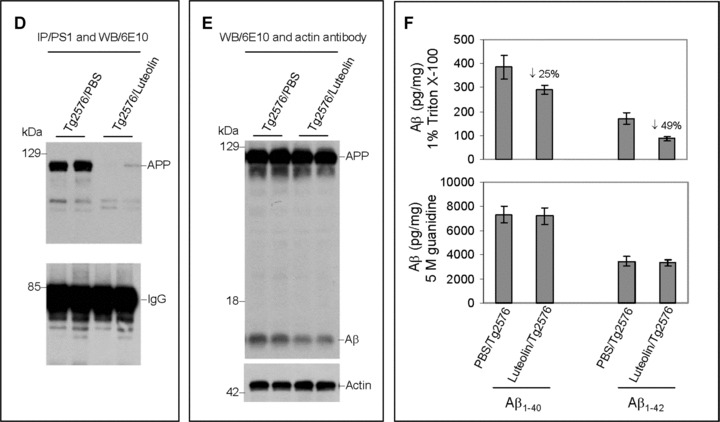

To validate the above findings in vivo, we treated 8 month-old Tg2576 mice with 20 mg/kg luteolin administered by daily intraperitoneal injection for 30 days. Brain homogenates from these mice were subsequently analysed by immunoprecipitation, Western blot and ELISA (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 6A, both GSK-3α/β active isoforms from the homogenates of luteolin treated mice are reduced when compared to control. Moreover, ratios of each phosphorylated GSK-3 isoform to its respective holo protein revealed a significant decrease in activation with treatment (P < 0.001, Fig. 6A). These decreases in activation are also apparent in the immunohistochemical analysis of GSK-3α/β activity in neurons of the CA1 region of the hippocampus and regions of the cingulate cortex (Fig. 6C). Western blot analysis of PS1 from treated mice interestingly shows significantly lower levels of PS1 processing by CTF to actin ratios (P < 0.001, Fig. 6B). To further confirm our mechanism in this model, brain homogenates were immunoprecipitated by PS1 antibody and probed for APP. As expected, luteolin treatment effectively abolished the PS1-APP association (Fig. 6D). We also observed no significant changes in holo APP expression following treatment and even detected a potential decrease in oligomeric forms of Aβ as illustrated in Fig. 6E. Finally, to assess this potential decrease, we conducted ELISA of both soluble and insoluble Aβ1–40, 42 (Fig. 6F). Luteolin treatment markedly reduced both soluble isoforms of Aβ by 25% and 49%, respectively (Fig. 6F). However, we found no such significant reductions in insoluble Aβ isoforms (Fig. 6F). All together, the above lines of evidence suggest luteolin treatment can attenuate ongoing AD pathology in vivo and does so through GSK-3-mediated regulation of PS1/γ-secretase activity.

6.

Luteolin reduces GSK-3 activation and cerebral amyloidosis in Tg2576 mice. Brain homogenates and sections from Tg2576 mice treated with luteolin (n= 5) or vehicle (PBS, n = 5). For (A), homogenates were analysed by Western blot with active and holo anti-GSK-3 antibodies with anti-actin antibodies as an internal control. Densitometric analysis reveals the ratio of active phosphorylated GSK-3α/β to holo GSK-3. A t-test reveals significant reductions in both active GSK-3α and β isoforms from luteolin-treated animals compared to control (P < 0.001). For (B), homogenates were analysed by Western blot with anti-PS1 CTF or NTF antibody. Densitometric analysis produces the ratio of PS1 CTF or NTF to actin (internal control). A t-test shows significant reductions in PS1 CTF levels with luteolin treatment (P <0.001), but not for PS1 NTF levels (P >0.05). For (C), immunochemistry staining analysis for active phosphorylated GSK-3α/β. For (D), homogenates were immunoprecipitated by anti-PS1 CTF antibody. Densitometric analysis of Western blot by 6E10 antibody shows the ratio of APP to IgG. A t-test revealed significant differences between luteolin treatment and control (P < 0.001). For (E), homogenates were analysed by Western blot by 6E10 antibody. Approximately 12-kD band may represent oligomeric form of amyloid. Densitometric analysis of Western blot by anti-actin antibody reveals no significant changes in the ratio of APP to actin. For (F), soluble and insoluble Aβ1–40, 42 peptides from homogenates were analysed by ELISA. For Aβ ELISA, data are represented as picograms of peptide present in milligrams of total protein. Luteolin treatment results in markedly reduced soluble Aβ1–40, 42 levels, 25% and 49%, respectively (top panel). No significant reductions in insoluble Aβ isoforms following treatment were observed (bottom panel).

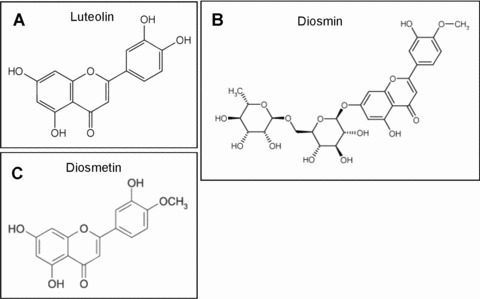

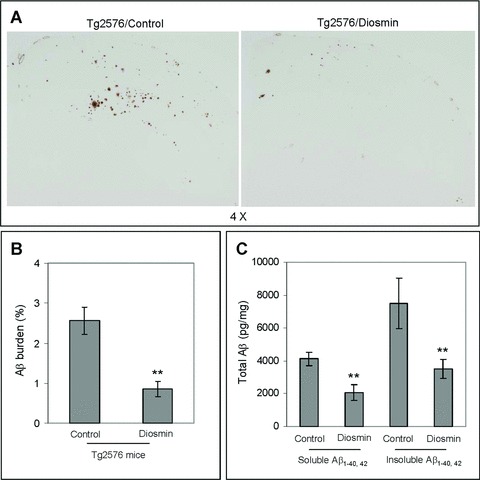

Oral administration of diosmin reduces Aβ pathology in Tg2576 mice

Previous pharmacokinetic studies suggest luteolin has an oral bioavailability <2% and a half-life in plasma <4 hrs, which would make it a poor candidate compound for oral clinical trials [45, 46]. Taking this situation into consideration, we screened other compounds with a 5,7-dihydroxyflavone structural backbone to identify a more suitable flavonoid for oral administration (Fig. 7). One compound, diosmetin, proved to be just as efficacious as luteolin in promoting PS1 CTF phosphorylation and consequently inhibiting γ-secretase activity in SweAPP N2a cells (data not shown). Cova et al. reported that the flavonoid diosmin, a well-evidenced vascular protecting agent, is rapidly transformed by intestinal flora to its aglycone form, diosmetin. Taken in this manner, diosmetin was found to be readily absorbed and rapidly distributed throughout the body with a plasma half-life >26 hrs [47]. To determine whether oral administration of diosmin, as a parent compound for diosmetin, could have similar anti-amyloidogenic effects in vivo as luteolin, Tg2576 mice were orally treated with 0.05% diosmin supplemented or control diet at 8 months of age for 6 months. As shown in Fig. 8, we found that diosmin treatment similarly reduced Aβ deposition in these mice. Image analysis of micrographs from Aβ antibody (4G8) stained sections reveals that plaque burdens were significantly reduced throughout the brain (P < 0.001; Fig. 8A and B). To verify the findings from these coronal sections, we analysed brain homogenates for Aβ levels by ELISA. Again, diosmin oral treatment markedly decreased both soluble and insoluble forms of Aβ1–40, 42 (Fig. 7C). Taken together, the above data confirm an oral route of administration of diosmin provides effective, if not superior, attenuation of amyloid pathology comparable to that of i.p injected luteolin.

7.

Chemical structures of the 5,7-dihydroxyflavone compounds.

8.

Oral administration of diosmin reduces Aβ pathology in Tg2576 mice. Brain homogenates and sections from Tg2576 mice treated with 0.05% diosmin supplemented diet (n= 10) or control diet (n= 10). For (A), half-brain coronal sections were analysed by Aβ antibody 4G8 staining. For (B), percentage of 4G8 positive plaques (mean ± S.E.M.) was quantified by image analysis. A t-test for independent samples revealed significant differences (P < 0.001) between groups. For (C), total soluble and insoluble Aβ1–40, 42 peptides from homogenates were analysed by ELISA. For Aβ ELISA, data are represented as picograms of peptide present in milligrams of total protein. Diosmin treatment results in markedly reduced total soluble and insoluble Aβ1–40, 42 levels, 37% and 46%, respectively. A t-test for independent samples revealed significant differences (P < 0.005) between groups.

Discussion

Although previous reports have substantiated the therapeutic potential of GSK-3 inhibitors in AD [28, 37, 48, 49], the underlying anti-amyloidogenic mechanisms have hitherto not been established. Here, we elucidate a mechanism whereby these GSK-3 inhibitors may reduce amyloidosis. Our study shows that reductions in GSK-3α activation, whether achieved by pharmacological means or by genetic silencing, promote the phosphorylation of the CTF of PS1, which subsequently disrupts the enzyme-substrate association with APP. As in vitro validation, we observe significant increases in PS1 CTF phosphorylation (20-kD isoforms) with luteolin, SB-415286, and GSK-3α RNAi treatment, which act with similar potentcy (luteolin and SB-415286) and efficacy (Fig. 4). Moreover, both in vitro and in vivo analyses reveal significant reductions in APP co-immunoprecipitated with PS1 following treatment (Figs. 5A, B and 6D, E). Accordingly, we would expect the concentration and time-dependent reductions in Aβ1–40, 42 generation following treatment that we observe in Fig. 1E and F. Even though it is apparent that γ-secretase activity also dose- and time-dependently decreases (Fig. 1E and F), it is unclear how this protein complex is affected. GSK-3α inhibition may potentially affect complex formation; however, we find no alteration of PS1, nicastrin, PEN2 or APH-1 expression levels following treatment (data not shown). Furthermore, GSK-3α inhibition does not appear to phosphorylate full-length PS1 and does not affect endo-proteolytic cleavage based on PS1 NTF analysis (Fig. 3C). Although we do not detect any phospho-PS1 CTFs in vivo, we do detect clear reductions in the 16-kD PS1 CTF bands (Fig. 6B), which are presumably indicative of a more highly active, amy-loidogenic γ-secretase complex. Therefore, it is likely that these compounds affect γ-secretase at the level of the CTF of PS1. However, it remains to be seen if phosphorylation of the CTF of PS1 is a required step for γ-secretase inhibition/Ap reduction mediated by luteolin. There are some obvious complexities to the mechanism of dimerization of PS1 along with subsequent association with other essential γ-secretase components such as nicastrin, which recent studies suggest may function as the γ-secretase substrate receptor [50]. Accordingly, it will now be important to investigate how or if this 20-kD phospho-PS1 CTF species interacts with PS1 NTFs or nicastrin.

Some of the earliest work investigating the activity of PS1 endo-proteolytic fragments and the oligomerization of the γ-secretase complex has already identified two human phosphorylated PS1 CTFs [51, 52]. What is more, the presence of these aforementioned phosphorylated PS1 CTFs corresponded with both reduction of Aβ generation and accumulation of the β-CTF of APP [51–53], which is what we clearly observe following luteolin treatment (Fig. 1). It is also important to note that the accumulation β-CTFs following luteolin treatment is a mere fraction of that seen when compared to the use of a direct γ-secretase inhibitor (data not shown). In view of this finding, it becomes increasingly evident that selective GSK-3 inactivation may be a less toxic, more regulative, substrate-specific mode of γ-secretase inhibition. Given the fact that the above earlier studies routinely employed the use of phorbol-12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu), a potent PKC activator, as their phosphorylating agent [51–53], we wondered if luteolin was similarly a PKC activator, rather than a GSK-3 inhibitor. Co-treatment of SweAPP N2a cells with luteolin or SB-415286 and the PKC inhibitor GF109203X had no effect on GSK-3 inhibition (data not shown). However, we did observe minor decreases in both 20-kD and 18-kD phospho-PS1 CTF isoforms following GF109203X treatment, indicating that PKC may play a part either in the downstream signalling mechanism or by directly phosphorylating the PS1 CTF. Additionally, there are no indications that GSK-3α inhibition affects non-amyloidogenic processing of APP as luteolin, SB-415286 and GSK-3αRNAi treatment have no effect on the maturation of TACE, ADAM10 or sAPPα release (data not shown), which are all strongly associated with PKC activation [54–58]. Collectively, these data suggest that GSK-3α may be an upstream regulator of PS1 CTF phosphorylation and consequently of γ-secretase activity.

In addition to clarifying this mechanism in our study, we also identify a flavonoid, luteolin, that we evidence to attenuate Aβ generation (Figs. 1 and 6) and feel may possess the potential to protect against the multiple arms of AD pathology. Luteolin, categorized as a citrus biflavonoid, has been previously shown to be a potent-free radical scavenger [59, 60], anti-inflammatory agent [61, 62] and immunomodulator [63, 64], possibly owing these two latter properties to its GSK-3 inhibitory nature. However, it must be noted that although we observe changes consistent with GSK-3 inhibition following luteolin treatment, it remains unclear whether or not this flavonoid is a direct inhibitor of this kinase. What seems to be evident, and a point at which it potentially differs from direct GSK-3 inhibitors (including SB-415286), is that luteolin treatment appears to selectively inactivate GSK-3α isoforms over β isoforms (Fig. 2). That is to say, luteolin treatment does appear to reduce active GSK-3β isoforms expressed at about 2 hrs (Fig. 2B and E), as compared to control (data not shown), but expression of active GSK-3α isoforms is more timely and effectively reduced (Fig. 2B and E). Remarkably, we also find that p-catenin remains unaffected by luteolin treatment, which may imply that this selective GSK-3 inactivation can circumvent the potential toxicity of more general GSK-3 inhibitors (data not shown). Furthermore, there is a clear correlation between increases in inactive and decreases in active GSK-3α (Fig. 2C and F) following treatment, which suggests that luteolin may affect the positive feedback loop of GSK-3 activation by inactivating the PP1 phosphatase [65]. The direct targeting of this feedback loop as a means to reduce GSK-3 activation seems highly probable in light of the fact that calyculin A, a PP1 inhibitor, treatment has previously been found to increase PS1 CTF phosphorylation [52].

Turning to luteolin's efficacy as an anti-amyloidogenic agent, we find that luteolin treatment markedly reduces both soluble Aβ1–40, 42 isoforms in vivo (Fig. 6F). Even though we observe no significant changes in insoluble Aβ1–40, 42 isoforms (Fig. 6F), one would expect this result given the age and consequent low plaque burden of these Tg2576 mice [43]. Like many aglycone forms of flavonoids, luteolin potentially reaches its molecular target by passive diffusion through cell membranes. This means of cellular uptake may explain the rapid onset of GSK-3α inactivation as we observed following luteolin treatment (Fig. 2A and D) and, along with our findings in Fig. 6, may indicate favourable blood – brain barrier permeability. It would also appear that diosmetin, via its parent compound diosmin, may possess a favourable blood -brain barrier permeability as Aβ pathology is markedly reduced in treated Tg2576 mice (Fig. 8). A micronized nutraceutical formulation of diosmin, under the trade name Daflon, has been successfully used to treat chronic venous disease and haemorrhoids for over a decade in Europe. Recently, improved formulations of diosmin have been marketed in both Europe and the United States for treatment of varicose and spider veins. However, these newer formulations may not actually improve efficacy of diosmin, as diosmetin is likely the active compound responsible for this nutraceu-tical's therapeutic attributes. At the same time, clinical study evaluating diosmin and its various formulations has laid the groundwork for future AD clinical trial. Based on the faster metabolic rate of the Tg2576 mice, the dose employed in our oral study would be equivalent to a ∼1000 mg of diosmin daily intake in human beings.

Ultimately, the identification of compounds that target multiple pathologies is essential for the formulation of effective therapeutic interventions. For these reasons, luteolin and diosmin/diosmetin may prove to be such effective compounds. We intend to further characterize and qualify both luteolin's and diosmin/diosmetin's therapeutic potential in AD (against both amyloidosis and tau hyperphosphorylation/NFT formation) in future study.

References

- 1.Funamoto S, Morishima-Kawashima M, Tanimura Y, Hirotani N, Saido TC, Ihara Y. Truncated carboxyl-terminal fragments of beta-amyloid precursor protein are processed to amyloid beta-proteins 40 and 42. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13532–40. doi: 10.1021/bi049399k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sambamurti K, Greig NH, Lahiri DK. Advances in the cellular and molecular biology of the beta-amyloid protein in Alzheimer's disease. Neuromol Med. 2002;1:1–31. doi: 10.1385/NMM:1:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golde TE, Eckman CB, Younkin SG. Biochemical detection of Abeta isoforms: implications for pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1502:172–87. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huse JT, Doms RW. Closing in on the amyloid cascade: recent insights into the cell biology of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2000;22:81–98. doi: 10.1385/MN:22:1-3:081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selkoe DL, Yamazaki T, Citron M, Podlisny MB, Koo EH, Teplow DB, Haass C. The role of APP processing and trafficking pathways in the formation of amyloid beta-protein. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;777:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaFerla FM, Tinkle BT, Bieberich CJ, Haudenschild CC, Jay G. The Alzheimer's A beta peptide induces neurodegeneration and apoptotic cell death in transgenic mice. Nat Genet. 1995;9:21–30. doi: 10.1038/ng0195-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loo DT, Copani A, Pike CJ, Whittemore ER, Walencewicz AJ, Cotman CW. Apoptosis is induced by beta-amyloid in cultured central nervous system neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7951–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradt BM, Kolb WP, Cooper NR. Complement-dependent proinflammatory properties of the Alzheimer's disease beta-peptide. J Exp Med. 1998;188:431–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suo Z, Tan J, Placzek A, Crawford F, Fang C, Mullan M. Alzheimer's beta-amyloid peptides induce inflammatory cascade in human vascular cells: the roles of cytokines and CD40. Brain Res. 1998;807:110–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00780-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami K, Irie K, Ohigashi H, Hara H, Nagao M, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T. Formation and stabilization model of the 42-mer Abeta radical: implications for the long-lasting oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15168–74. doi: 10.1021/ja054041c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hensley K, Carney JM, Mattson MP, Aksenova M, Harris M, Wu JF, Floyd RA, Butterfield DA. A model for beta-amyloid aggregation and neurotoxicity based on free radical generation by the peptide: relevance to Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3270–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenk DB, Rydel RE, May P, Little S, Panetta J, Lieberburg I, Sinha S. Therapeutic approaches related to amyloid-beta peptide and Alzheimer's disease. J Med Chem. 1995;38:4141–54. doi: 10.1021/jm00021a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinha S, Lieberburg I. Cellular mechanisms of beta-amyloid production and secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11049–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vassar R, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, Teplow DB, Ross S, Amarante P, Loeloff R, Luo Y, Fisher S, Fuller J, Edenson S, Lile J, Jarosinski MA, Biere AL, Curran E, Burgess T, Louis JC, Collins F, Treanor J, Rogers G, Citron M. Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by the trans-membrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–41. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan R, Bienkowski MJ, Shuck ME, Miao H, Tory MC, Pauley AM, Brashier JR, Stratman NC, Mathews WR, Buhl AE, Carter DB, Tomasselli AG, Parodi LA, Heinrikson RL, Gurney ME. Membrane-anchored aspartyl protease with Alzheimer's disease beta-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;402:533–7. doi: 10.1038/990107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steiner H, Duff K, Capell A, Romig H, Grim MG, Lincoln S, Hardy J, Yu X, Picciano M, Fechteler K, Citron M, Kopan R, Pesold B, Keck S, Baader M, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Baumeister R, Haass C. A loss of function mutation of presenilin-2 interferes with amyloid beta-peptide production and notch signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28669–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Strooper B, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Vanderstichele H, Guhde G, Annaert W, Von Figura K, Van Leuven F. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1998;391:387–90. doi: 10.1038/34910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Citron M, Diehl TS, Gordon G, Biere AL, Seubert P, Selkoe DJ. Evidence that the 42- and 40-amino acid forms of amyloid beta protein are generated from the beta-amyloid precursor protein by different protease activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13170–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evin G, Cappai R, Li QX, Culvenor JG, Small DH, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. Candidate gamma-secretases in the generation of the carboxyl terminus of the Alzheimer's disease beta A4 amyloid: possible involvement of cathepsin D. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14185–92. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barten DM, Meredith JE, Jr, Zaczek R, Houston JG, Albright CF. Gamma-secretase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease: balancing efficacy and toxicity. Drugs R D. 2006;7:87–97. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200607020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evin G, Sernee MF, Masters CL. Inhibition of gamma-secretase as a therapeutic intervention for Alzheimer's disease: prospects, limitations and strategies. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:351–72. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dovey HF, John V, Anderson JP, Chen LZ, De Saint Andrieu P, Fang LY, Freedman SB, Folmer B, Goldbach E, Holsztynska EJ, Hu KL, Johnson-Wood KL, Kennedy SL, Kholodenko D, Knops JE, Latimer LH, Lee M, Liao Z, Lieberburg IM, Motter RN, Mutter LC, Nietz J, Quinn KP, Sacchi KL, Seubert PA, Shopp GM, Thorsett ED, Tung JS, Wu J, Yang S, Yin CT, Schenk DB, May PC, Altstiel LD, Bender MH, Boggs LN, Britton TC, Clemens JC, Czilli DL, Dieckman-McGinty DK, Droste JJ, Fuson KS, Gitter BD, Hyslop PA, Johnstone EM, Li WY, Little SP, Mabry TE, Miller FD, Audia JE. Functional gamma-secretase inhibitors reduce beta-amyloid peptide levels in brain. J Neurochem. 2001;76:173–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Citron M, Diehl TS, Capell A, Haass C, Teplow DB, Selkoe DJ. Inhibition of amyloid beta-protein production in neural cells by the serine protease inhibitor AEBSF. Neuron. 1996;17:171–9. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Games D, Adams D, Alessandrini R, Barbour R, Berthelette P, Blackwell C, Carr T, Clemens J, Donaldson T, Gillespie F, Guido T, Hagopian K, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Lee M, Leibowitz P, Lieberburg I, Little S, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Montoya-Zavala M, Mucke L, Paganini L, Penniman E, Power M, Schenk D, Seubert P, Snyder B, Soriano F, Tan H, Vitale J, Wadsworth S, Wolozin B, Zhao J. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in trans-genic mice overexpressing V717F beta-amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1995;373:523–7. doi: 10.1038/373523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higaki L, Quon D, Zhong Z, Cordell B. Inhibition of beta-amyloid formation identifies proteolytic precursors and subcellu-lar site of catabolism. Neuron. 1995;14:651–9. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klafki HW, Paganetti PA, Sommer B, Staufenbiel M. Calpain inhibitor I decreases beta A4 secretion from human embryonal kidney cells expressing beta-amyloid precursor protein carrying the APP670/671 double mutation. Neurosci Lett. 1995;201:29–32. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12122-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comery TA, Martone RL, Aschmies S, Atchison KP, Diamantidis G, Gong X, Zhou H, Kreft AF, Pangalos MN, Sonnenberg-Reines J, Jacobsen JS, Marquis KL. Acute gamma-secretase inhibition improves contextual fear conditioning in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8898–902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2693-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engel T, Hernandez F, Avila J, Lucas JJ. Full reversal of Alzheimer's disease-like phenotype in a mouse model with conditional overexpression of glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5083–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0604-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozlovsky N, Belmaker RH, Agam G. Low GSK-3beta immunoreactivity in postmortem frontal cortex of schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:831–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carmichael J, Sugars KL, Bao YP, Rubinsztein DC. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibitors prevent cellular polyglutamine toxicity caused by the Huntington's disease mutation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33791–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agam G, Levine J. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 – a new target for lithium's effects in bipolar patients? Hum Psycho -pharmacol Clin Exp. 1998;13:463–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishiguro K, Shiratsuchi A, Sato S, Omori A, Arioka M, Kobayashi S, Uchida T, Imahori K. Glycogen synthase kinase 3(3 is identical to tau protein kinase I generating several epitopes of paired helical filaments. FEBS Lett. 1993;325:167–72. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aplin AE, Gibb GM, Jacobsen JS, Gallo JM, Anderton BH. In vitro phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain of the amyloid precursor protein by glycogen synthase kinase-3β. J Neurochem. 1996;67:699–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67020699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takashima A, Noguchi K, Michel G, Mercken M, Hoshi M, Ishiguro K, Imahori K. Exposure of rat hippocampal neurons to amyloid β peptide (25–35) induces the inactivation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and the activation of tau protein kinase 1/glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Neurosci Lett. 1996;203:33–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takashima A, Honda T, Yasutake K, Michel G, Murayama O, Murayama M, Ishiguro K, Yamaguchi H. Activation of tau protein kinase 1/glycogen synthase-3β by amyloid β peptide (25–35) enhances phosphorylation of tau in hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Res. 1998;32:317–23. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(98)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takashima A, Murayama M, Murayama O, Kohno T, Honda T, Yasutake K, Nihonmatsu N, Mercken M, Yamaguchi H, Sugihara S, Wolozin B. Presenilin 1 associates with glycogen synthase kinase-3(i and its substrate tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9637–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phiel CJ, Wilson CA, Lee VM, Klein PS. GSK-3alpha regulates production of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta peptides. Nature. 2003;423:435–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barberger-Gateau P, Raffaitin C, Letenneur L, Berr C, Tzourio C, Dartigues JF, Alperovitch A. Dietary patterns and risk of dementia: the Three-City cohort study. Neurology. 2007;69:1921–30. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000278116.37320.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dai Q, Borenstein AR, Wu Y, Jackson JC, Larson EB. Fruit and vegetable juices and Alzheimer's disease: the Kame Project. Am J Med. 2006;119:751–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marambaud P, Zhao H, Davies P. Resveratrol promotes clearance of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta peptides. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37377–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rezai-Zadeh K, Shytle D, Sun N, Mori T, Hou H, Jeanniton D, Ehrhart J, Townsend K, Zeng J, Morgan D, Hardy J, Town T, Tan J. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) modulates amyloid precursor protein cleavage and reduces cerebral amyloi- dosis in Alzheimer transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8807–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1521-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang F, Lim GP, Begum AN, Ubeda OJ, Simmons MR, Ambegaokar SS, Chen PP, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5892–901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan J, Town T, Crawford F, Mori T, DelleDonne A, Crescentini R, Obregon D, Flavell RA, Mullan MJ. Role of CD40 ligand in amyloidosis in transgenic Alzheimer's mice. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1288–93. doi: 10.1038/nn968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wittemer SM, Ploch M, Windeck T, Miiller SC, Drewelow B, Derendorf H, Veit M. Bioavailability and pharmacokinet-ics of caffeoylquinic acids and flavonoids after oral administration of Artichoke leaf extracts in humans. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimoi K, Okada H, Furugori M, Goda T, Takase S, Suzuki M, Hara Y, Yamamoto H, Kinae N. Intestinal absorption of lute-olin and luteolin 7-O-beta-glucoside in rats and humans. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:220–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cova D, De Angelis L, Giavarini F, Palladini G, Perego R. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of oral diosmin in healthy volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1992;30:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong M, Chen DC, Klein PS, Lee VM. Lithium reduces tau phosphorylation by inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25326–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munoz-Montano JR, Moreno FJ, Avila J, Diaz-Nido J. Lithium inhibits Alzheimer's disease-like tau protein phosphorylation in neurons. FEBS Lett. 1997;411:183–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shah S, Lee SF, Tabuchi K, Hao YH, Yu C, LaPlant Q, Ball H, Dan CE, 3rd, Sudhof T, Yu G. Nicastrin functions as a gamma-secretase-substrate receptor. Cell. 2005;122:435–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seeger M, Nordstedt C, Petanceska S, Kovacs DM, Gouras GK, Hahne S, Fraser P, Levesque L, Czernik AJ, George-Hyslop PS, Sisodia SS, Thinakaran G, Tanzi RE, Greengard P, Gandy S. Evidence for phosphorylation and oligomeric assembly of presenilin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5090–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walter J, Grunberg J, Capell A, Pesold B, Schindzielorz A, Citron M, Mendla K, George-Hyslop PS, Multhaup G, Selkoe DJ, Haass Proteolytic processing of the Alzheimer disease-associated presenilin-1 generates an in vivo substrate for protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5349–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buxbaum JD, Gandy SE, Cicchetti P, Ehrlich ME, Czernik AJ, Fracasso RP, Ramabhadran TV, Unterbeck AJ, Greengard P. Processing of Alzheimer beta/A4 amyloid precursor protein: modulation by agents that regulate protein phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6003–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.6003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lopez-Perez E, Zhang Y, Frank SJ, Creemers J, Seidah N, Checler F. Constitutive alpha-secretase cleavage of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in the furin-deficient LoVo cell line: involvement of the pro-hormone convertase 7 and the disintegrin metalloprotease ADAM10. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1532–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buxbaum JD, Liu KN, Luo Y, Slack JL, Stocking KL, Peschon JJ, Johnson RS, Castner BJ, Cerretti DP, Black RA. Evidence that tumor necrosis factor a converting enzyme is involved in regulated α-secretase cleavage of the Alzheimer amyloid protein precursor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27765–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Savage M, Trusko SP, Howland DS, Pinsker LR, Mistretta S, Reaume AG, Greenberg BD, Siman R, Scott RW. Turnover of amyloid β-protein in mouse brain and acute reduction of its level by phorbol ester. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1743–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01743.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Checler F. Processing of the β-amyloid precursor protein and its regulation in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 1995;65:1431–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65041431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hung AY, Haass C, Nitsch RM, Qiu WQ, Citron M, Wurtman RJ, Growdon JH, Selkoe DJ. Activation of protein kinase C inhibits cellular production of the amyloid beta-protein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22959–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hyun SK, Jung HA, Chung HY, Choi JS. In vitro peroxynitrite scavenging activity of 6-hydroxykynurenic acid and other flavonoids from Gingko biloba yellow leaves. Arch Pharm Res. 2006;29:1074–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02969294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horvathova K, Novotny L, Tothova D, Vachalkova A. Determination of free radical scavenging activity of quercetin, rutin, luteolin and apigenin in H2O2-treated human ML cells K562. Neoplasma. 2004;51:395–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hougee S, Sanders A, Faber J, Graus YM, Van Den Berg WB, Garssen J, Smit HF, Hoijer MA. Decreased pro-inflammatory cytokine production by LPS-stimulated PBMC upon in vitro incubation with the flavonoids apigenin, luteolin or chrysin, due to selective elimination of mono-cytes/macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verbeek R, Plomp AC, Van Tol EA, Van Noort JM. The flavones luteolin and apigenin inhibit in vitro antigen-specific proliferation and interferon-gamma production by murine and human autoimmune T cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:621–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hirano T, Higa S, Arimitsu J, Naka T, Ogata A, Shima Y, Fujimoto M, Yamadori T, Ohkawara T, Kuwabara Y, Kawai M, Matsuda H, Yoshikawa M, Maezaki N, Tanaka T, Kawase I, Tanaka T. Luteolin, a flavonoid, inhibits AP-1 activation by basophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirano T, Higa S, Arimitsu J, Naka T, Shima Y, Ohshima S, Fujimoto M, Yamadori T, Kawase I, Tanaka T. Flavonoids such as luteolin, fisetin and apigenin are inhibitors of interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 production by activated human basophils. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;134:135–40. doi: 10.1159/000078498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang F, Phiel CJ, Spece L, Gurvich N, Klein PS. Inhibitory phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) in response to lithium. Evidence for autoreg-ulation of GSK-3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33067–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]