Abstract

Stress-induced mutagenesis is a collection of mechanisms observed in bacterial, yeast, and human cells in which adverse conditions provoke mutagenesis, often under the control of stress responses. Control of mutagenesis by stress responses may accelerate evolution specifically when cells are maladapted to their environments, i.e., are stressed. It is therefore important to understand how stress responses increase mutagenesis. In the Escherichia coli Lac assay, stress-induced point mutagenesis requires induction of at least two stress responses: the RpoS-controlled general/starvation stress response and the SOS DNA-damage response, both of which upregulate DinB error-prone DNA polymerase, among other genes required for Lac mutagenesis. We show that upregulation of DinB is the only aspect of the SOS response needed for stress-induced mutagenesis. We constructed two dinB(oc) (operator-constitutive) mutants. Both produce SOS-induced levels of DinB constitutively. We find that both dinB(oc) alleles fully suppress the phenotype of constitutively SOS-“off” lexA(Ind−) mutant cells, restoring normal levels of stress-induced mutagenesis. Thus, dinB is the only SOS gene required at induced levels for stress-induced point mutagenesis. Furthermore, although spontaneous SOS induction has been observed to occur in only a small fraction of cells, upregulation of dinB by the dinB(oc) alleles in all cells does not promote a further increase in mutagenesis, implying that SOS induction of DinB, although necessary, is insufficient to differentiate cells into a hypermutable condition.

GENOMIC stability and mutation rates are tightly regulated features of all organisms. Understanding how cells regulate mutation rates has important implications for evolution, cancer progression and chemotherapy resistance, aging, and acquisition of antibiotic resistance and evasion of the immune system by pathogens, all processes driven by mutagenesis and all of which occur during stress.

Stress-induced mutagenesis refers to a group of related phenomena in which cells poorly adapted to their environment (i.e., stressed) increase mutation rates as part of a regulated stress response (reviewed by Galhardo et al. 2007). Abundant examples, particularly in microorganisms, show the induction of specific pathways of mutagenesis in response to stresses. The types of genetic alteration induced by stress include base substitutions, small deletions and insertions, gross chromosomal rearrangements and copy-number variations, and movement of mobile elements. These various pathways require the functions of different sets of genes and proteins. Thus, there appear to be multiple molecular mechanisms of stress-inducible mutagenesis that operate in different organisms, cell types, and growth-inhibiting stress conditions.

However, a common theme in the many mechanisms of stress-inducible mutagenesis described to date is the requirement for the function of one or more cellular stress responses. Starvation stress-induced mutagenesis in Bacillus subtilis requires the comK regulatory gene that controls the stress response that in turn allows competence for natural transformation in response to starvation (Sung and Yasbin 2002). The RpoS-controlled general or starvation stress response is required for starvation-induced excisions of phage Mu in Escherichia coli (Gomez-Gomez et al. 1997), for base-substitution mutagenesis in aging E. coli colonies (Bjedov et al. 2003), for starvation-induced point mutations (Saumaa et al. 2002) and transpositions (Ilves et al. 2001) in Pseudomonas putida, and for starvation-induced gene amplification (Lombardo et al. 2004) and frameshift mutagenesis (Layton and Foster 2003; Lombardo et al. 2004) in the E. coli Lac assay, described in more detail below. The SOS DNA-damage stress response is required for the stress-induced frameshift mutagenesis in the E. coli Lac assay discussed below, for E. coli mutagenesis in aging colonies (Taddei et al. 1997), for ciprofloxacin (antibiotic)-induced resistance mutagenesis (Cirz et al. 2005), and for mutagenesis conferring resistance to bile salts in Salmonella (Prieto et al. 2006). The stringent response to amino-acid starvation is required for a transcription-associated mutagenesis in E. coli that targets stringent-response-controlled genes (Wright et al. 1999) and for amino-acid-starvation-induced mutagenesis in B. subtilis (Rudner et al. 1999). Two different stress responses to hypoxia in human cancer cells also increase mutagenesis. One does so by specific downregulation of mismatch-repair genes (Mihaylova et al. 2003; Koshiji et al. 2005; Bindra and Glazer 2007). The other is postulated to promote genome rearrangement by its demonstrated downregulation of RAD51 and BRCA1 functions required for high-fidelity repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) (Bindra et al. 2004). These stress responses exert temporal control or restriction of mutagenesis, which favors genomic stability when cells and organisms are well adapted to their environments (i.e., not stressed) and increases mutagenesis, potentially accelerating evolution, specifically during stress when cells are maladapted to their environments. Except for the human examples, the ways by which the stress responses upregulate mutagenesis are mostly not understood. We focus here on how a stress response controls mutagenesis in an E. coli model system.

Stress-induced mutagenesis is perhaps best understood in the E. coli model system. A widely used assay system uses a +1 frameshift allele of a lacIZ fusion gene located in the F′128 plasmid in cells with a deletion of the chromosomal lac genes (Cairns and Foster 1991). When these cells are plated on lactose minimal medium, a few Lac+ revertant colonies are observed. Many of these arise from spontaneous generation-dependent mutations that occur during growth of the culture. Prolonged incubation of these plates results in the continuous accumulation of additional Lac+ revertants, which arise through two mechanisms, both different from the mechanisms that produce the generation-dependent mutants (reviewed by Galhardo et al. 2007).

First, within the first few days, most of the Lac+ colonies are “point mutants” that possess a compensatory −1 frameshift mutation in the lacIZ gene (Foster and Trimarchi 1994; Rosenberg et al. 1994). Cells that carry these mutations also carry increased numbers of secondary unselected mutations in other genomic regions, whereas most Lac− cells starved on the same plates do not, indicating that a subpopulation of the cells undergoes genomewide hypermutation (Torkelson et al. 1997; Rosche and Foster 1999; Godoy et al. 2000). Therefore, a subset of the starved cells experiences increased mutagenesis when compared with the majority of the cells. Hereafter we refer to this subpopulation as “hypermutable.” This hypermutable cell subpopulation (HMS) appears to be important to the formation of most or all of the Lac+ stress-induced mutants (Gonzales et al. 2008). The hypermutable state is transient, ceasing after growth impairment is ended and growth resumes (Longerich et al. 1995; Torkelson et al. 1997; Rosenberg et al. 1998; Rosche and Foster 1999; Godoy et al. 2000).

Second, longer incubation also results in the formation of a significant proportion of lac-amplified colonies in which the leaky lacIZ allele is amplified to 20–50 tandem copies, which produce sufficient enzyme activity to allow growth on lactose (Hastings et al. 2000; Powell and Wartell 2001; Kugelberg et al. 2006; Slack et al. 2006). In summary, E. coli cells may either increase point-mutation rates or undergo extensive genomic rearrangement in response to a growth-limiting environment.

Both of these processes require induction of the general or starvation stress response controlled by RpoS (Lombardo et al. 2004). Point mutagenesis, but not amplification, also requires induction of the SOS DNA-damage stress response (Cairns and Foster 1991; McKenzie et al. 2000, 2001). In this article, we focus on the role of the SOS response in the mechanism of stress-induced point mutagenesis. See Hastings (2007) for a review of the mechanisms of stress-induced amplification and genome rearrangement.

The molecular mechanism of point mutagenesis in the Lac system is now considerably well understood. It entails a switch from the normally high-fidelity DNA synthesis associated with recombination-dependent double-strand-break repair to an error-prone synthesis specifically under stress (Ponder et al. 2005). Several genetic requirements are known for stress-induced point mutagenesis, including DNA-recombination functions (Harris et al. 1994, 1996; Foster et al. 1996; He et al. 2006) in addition to the genes required for induction of the SOS DNA-damage response (Cairns and Foster 1991; McKenzie et al. 2000) and the σS (RpoS) general/starvation stress-response (Layton and Foster 2003; Lombardo et al. 2004) regulons, and the dinB gene encoding DNA polymerase (Pol) IV (McKenzie et al. 2001).

DinB is the founding member of the most widespread subfamily of Y-family specialized DNA polymerases, with orthologs in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, including humans (reviewed by Nohmi 2006). DinB/Pol IV can perform high-fidelity translesion DNA synthesis (TLS) across a number of different DNA lesion substrates (Jarosz et al. 2006; Bjedov et al. 2007; Yuan et al. 2008). However, this enzyme shows a significant error rate when copying undamaged DNA templates (Kobayashi et al. 2002). Some mutations in DinB can abolish its TLS activity, without interfering with the mutator phenotype caused by overexpression of DinB, suggesting that mutagenesis and TLS are independent activities of Pol IV (Godoy et al. 2007). Eighty-five percent of the stress-induced Lac+ point mutations generated in the nongrowing cells arise in a DinB-dependent manner (McKenzie et al. 2001).

The dinB gene is under the control of the SOS response, which upregulates its transcription 10-fold (Kim et al. 2001). Additionally, the alternative σ (transcription) factor σS (RpoS), which is responsible for the general stress response, upregulates dinB expression transcriptionally by 2- to 3-fold upon entry into stationary phase (Layton and Foster 2003). Proteins such as Ppk (Stumpf and Foster 2005) and the chaperones GroEL (Layton and Foster 2005), RecA, and UmuD (Godoy et al. 2007) all seem to modulate DinB activity. An interesting in vivo role of DinB is SOS untargeted mutagenesis of phage λ (Kim et al. 1997). In it, −1 frameshift mutations in runs of G's are generated, similarly to the predominant mutations detected in the lac gene during stress-induced mutagenesis (Foster and Trimarchi 1994; Rosenberg et al. 1994). On the other hand, DinB has no effect on the spontaneous mutation rate in growing cells (McKenzie et al. 2001, 2003; Kuban et al. 2004; Wolff et al. 2004). DinB is implicated as the DNA polymerase that, only during the stress responses, makes DSB-repair-associated errors that become stress-induced point mutations (Ponder et al. 2005).

The role of the SOS response in controlling mutagenesis in the Lac assay is a complex issue because several SOS-controlled genes are required for the process. dinB, recA, ruvA, and ruvB are all required for mutagenesis (Cairns and Foster 1991; Harris et al. 1994, 1996; Foster et al. 1996; McKenzie et al. 2001; He et al. 2006) and are all upregulated by SOS (Courcelle et al. 2001). Also, the F-encoded psiB gene exerts a negative effect on mutagenesis in SOS-derepressed cells (McKenzie et al. 2000) and is thought to inhibit SOS induction and RecA (reviewed by Cox 2007). We sought to determine whether the requirement for induction of the SOS response in stress-induced mutagenesis reflects a need for upregulation solely of dinB or whether any other gene(s) is required at SOS-induced levels. We present evidence below that indicates, first, that DinB is the only SOS-controlled gene required at induced levels for efficient stress-induced point mutagenesis and, second, that, although SOS-induced levels of DinB are required, they are not sufficient to differentiate cells into a hypermutable condition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media:

The bacterial strains used in this work are shown in Table 1. dinB(oc) alleles were constructed as described below. Other strains were constructed using P1-mediated transduction as described (Miller 1992). The antibiotics used were as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml; tetracycline, 10 μg/ml; kanamycin, 30 μg/ml; and rifampicin, 40 μg/ml. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-gal) was used at 40 μg/mL. M9 minimal medium (Miller 1992) was supplemented with 10 μg/ml of vitamin B1 and either 0.1% glycerol or 0.1% lactose. Luria–Bertani–Herskowitz (LBH) medium was used as described by Torkelson et al. (1997).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Name | Relevant genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| FC29 | Δ(lac-proB)XIII ara thi [F′ Δ(lacI-lacZ)] | Cairns and Foster (1991) |

| FC40 | Δ(lac-proB)XIII ara thi RifR [F′ lacI33ΩlacZ proAB+] | Cairns and Foster (1991) |

| FC231 | FC40 lexA3(Ind−) | Cairns and Foster (1991) |

| SMR868 | FC40 lexA3(Ind−) | McKenzie et al. (2000) |

| SMR4562 | Identical to FC40, independent construction | McKenzie et al. (2000) |

| SMR5400 | SMR4562 sulA211 lexA51(Def) ΔpsiB∷cat | McKenzie et al. (2000) |

| SMR9436 | SMR4562 ΔruvC∷FRTKanFRT | Magner et al. (2007) |

| SMR5889 | SMR4562 ΔdinB50∷FRT [F′ ΔdinB50∷FRT] | McKenzie et al. (2001) |

| SMR10292 | SMR4562 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT] | This study |

| SMR10299 | FC36 Δ(lafU-dinB)2097(∷FRTKanFRT) | This study |

| SMR10303 | SMR4562 Δ(lafU-dinB)2097(∷FRTKanFRT) [F′ Δ(lafU-dinB)2096(∷FRT)] | This study |

| SMR10304 | SMR4562 Δ(lafU-dinB)2097(∷FRTKanFRT) [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-21(oc)] | This study |

| SMR10306 | SMR4562 Δ(lafU-dinB)2097(∷FRTKanFRT) [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-22(oc)] | This study |

| SMR10308 | SMR4562 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-21(oc)] | SMR4562 × P1(SMR10304) |

| SMR10309 | SMR4562 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-22(oc)] | SMR4562 × P1(SMR10306) |

| SMR10310 | SMR868 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-21(oc)] | SMR868 × P1(SMR10304) |

| SMR10311 | SMR868 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-22(oc)] | SMR868 × P1(SMR10306) |

| SMR10314 | SMR868 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT] | SMR868 × P1(SMR10292) |

| SMR10760 | FC231 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT] | FC231 × P1(SMR10292) |

| SMR10761 | FC231 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-21(oc)] | FC231 × P1(SMR10304) |

| SMR10762 | FC231 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-22(oc)] | FC231 × P1(SMR10306) |

| SMR10766 | SMR4562 ΔruvC∷FRTKanFRT [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT] | SMR10292 × P1(SMR9436) |

| SMR10767 | FC231 ΔruvC∷FRTKanFRT [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-21(oc)] | SMR10761× P1(SMR9436) |

| SMR10768 | FC231 ΔruvC∷FRTKanFRT [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT] | SMR10760 × P1(SMR9436) |

| SMR10838 | SMR4562 [pPdinB] | This study |

| SMR10839 | SMR4562 [pPdinBOC1] | This study |

| SMR10840 | SMR4562 [pPdinBOC2] | This study |

| SMR10841 | SMR5400 [pPdinB] | This study |

| SMR10842 | SMR5400 [pPdinBOC1] | This study |

| SMR10843 | SMR5400 [pPdinBOC2] | This study |

| SMR11023 | SMR4562 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT ΔyafNOP∷FRTKanFRT] | This study |

| SMR11024 | SMR4562 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT ΔyafNOP∷FRTKanFRT dinBo-21(oc)] | This study |

| SMR11026 | FC231 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT ΔyafNOP∷FRTKanFRT] | FC231 × P1(SMR11023) |

| SMR11027 | FC231 [F′ lafU2∷FRTcatFRT ΔyafNOP∷FRTKanFRT dinBo-21(oc)] | FC231 × P1(SMR11024) |

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. Plasmids containing PdinBlacZ fusions used in β-galactosidase assays for gene expression analysis were constructed by amplification of the dinB promoter (from bases −432 to −2 of dinB) with primers 5′-TCGGCTGAATTCTGTTCGACTCGCTCGATAAT-3′ and 5′-CGGTACAAGCTTGCTCACCTCTCAACACTGGT-3′ and by cloning into the pFZY plasmid (Koop et al. 1987) using the EcoRI and HindIII sites introduced in the primers. The dinB promoter was amplified from strain SMR4562 and cloned into pFZY to generate plasmid pPdinB and amplified from strains SMR10308 and SMR10309 to generate the plasmids pPdinBOC1 and pPdinBOC2, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Name | Description and source |

|---|---|

| pFZY | Low-copy plasmid with multicloning site abutting a promoterless lacZ (Koop et al. 1987) |

| pPdinB | Bases −432 to −2 of dinB from strain SMR4562 cloned into pFZY, producing a PdinBlacZ fusion |

| pPdinBOC1 | Bases −432 to −2 of dinB from strain SMR10308 cloned into pFZY, producing a PdinBo-21(oc)lacZ fusion |

| pPdinBOC2 | Bases −432 to −2 of dinB from strain SMR10309 cloned into pFZY, producing a PdinBo-22(oc)lacZ fusion |

Construction of the dinB(oc) alleles and strains bearing them:

We created each of two mutations predicted from previous work on other SOS genes (Friedberg et al. 2005) to inactivate the predicted LexA-binding site in dinB (Figure 1A). The Lac assay strains carry two copies of dinB, one in the chromosome and one in F′128 (discussed in the results). The constructions required several steps as below. Primer sequences are given in the supporting information, File S1.

Figure 1.—

Construction and characterization of two dinB(oc) alleles. (A) Location of the operator-constitutive mutations in the dinB promoter. The SOS operator (from Fernandez De Henestrosa et al. 2000) is shaded, and the mutations introduced in each of the alleles are in boldface and italic type. The beginning of the dinB ORF is shown in boldface type. (B) Activity of the dinB promoter in transcriptional fusions with lacZ, measured in both wild-type (SMR4562) and its LexA-defective (null), lexA51(Def), derivative strain SMR5400, in which SOS is constitutively highly induced. The strains from left to right are SMR10838, SMR10839, SMR10840, SMR10841, SMR10842, and SMR10843. PdinB indicates the wild-type dinB promoter present in plasmid pPdinB, POc1 indicates the dinBo-21(oc) promoter contained in plasmid pPdinBOC1, and POc2 indicates the dinBo-22(oc) promoter contained in plasmid pPdinBOC2. Mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (SEM) for three independent determinations.

First, we linked the cat selectable marker with dinB. We chose to put a selectable marker in the lafU (formerly known as mbhA) gene, which is present immediately upstream from the 5′-end of dinB. The FRTcatFRT cassette was amplified from pKD3 (Datsenko and Wanner 2000) using primers CatupdinB-F and CatupdinB-R. The product was used to obtain SMR4562 recombinants containing the lafU∷FRTcatFRT insertion (allele ΔlafU2∷FRTcatFRT), using short-homology recombination as described (Datsenko and Wanner 2000). One recombinant containing the ΔlafU2∷FRTcatFRT in the F′ plasmid was selected. This strain (SMR10292) was used to amplify the ΔlafU2∷FRTcatFRT-dinB+ region by PCR using primers CatupdinB-F and dinBcatnock-R. This product was used as a template for PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis, altering the dinB promoter.

Next we constructed a ΔlafU-dinB deletion strain to be used as a recipient for allelic replacement with the site-directed dinB-mutant genes linked to ΔlafU2∷FRTcatFRT. We created a FC36-derivative containing a deletion encompassing the 3′ half of ΔlafU and the whole dinB gene using primers kandinBchrom-F and DinBRCAT to amplify FRTKanFRT from pKD13 (Datsenko and Wanner 2000). The products were used for short-homology recombination in the FC36 background, creating strain SMR10299. A similar deletion in the same region in the F′ plasmid was created by short-homology recombination in SMR4562, using FRTcatFRT amplified from pKD3 with primers CatupdinB-F and DinBRCAT. Location of the deletion in the F′ plasmid was confirmed by the ability to conjugate the cat gene conferring chloramphenicol resistance. The cat gene was removed by FLP-mediated site-specific recombination using the pCP20 plasmid (Datsenko and Wanner 2000). The resulting F′128 ΔlafU-dinB∷FRT [allele Δ(lafU-dinB)2096(∷FRT)] was mated into strain SMR10299, creating strain SMR10303 {SMR4562 Δ(lafU-dinB)2097(∷FRTKanFRT) [F′ Δ(lafU-dinB)2096(∷FRT)]}. This strain was used as a recipient for allelic replacement using the site-directed dinB mutants produced by PCR with the ΔlafU2∷FRTcatFRT-dinB fragment as a template. The sequence of the promoter and coding sequence of the dinB gene from the KanR CamR recombinants was determined by PCR and DNA sequencing to ensure that the desired mutation was introduced and that no other mutation in dinB was generated inadvertently by PCR. One recombinant containing the dinBo-21(oc) mutation (SMR10304) and one containing the dinBo-22(oc) mutation (SMR10306) were chosen. Those strains were used as P1 donors of ΔlafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-21(oc) and ΔlafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-22(oc), respectively, to transduce the dinB(oc) alleles to all the genetic backgrounds of interest, including SMR4562 and strains FC231 and SMR868 carrying lexA3(Ind−).

Deletion of the yafNOP genes in the dinB operon was performed using short-homology recombination (Datsenko and Wanner 2000) as follows. Strains SMR10292 [SMR4562 (F′ ΔlafU2∷FRTcatFRT)] and SMR10308 [SMR4562 (F′ ΔlafU2∷ FRTcatFRT dinBo-21(oc))] were used as recipients for deletion by transformation with a DNA fragment amplified from pKD13 with primers yafNwL and yafPwR. Homologous incorporation of this DNA fragment, which contains the FRTKanFRT marker, results in a deletion of the yafNOP genes. KanR recombinants were selected, and location of the marker in the F′ episome was confirmed both by ability to transfer the resistance during mating and by cotransduction of KanR and CamR (present in the linked lafU2∷FRTcatFRT in both strains). The strains resulting from deletion of yafNOP from the episomes of SMR10292 and SMR10308 were named SMR11023 and SMR11024, respectively. Both strains were used respectively as P1 donors to transfer the lafU2∷FRTcatFRT ΔyafNOP∷FRTKanFRT linkage and the lafU2∷FRTcatFRT dinBo-21(oc) ΔyafNOP:FRT:KanFRT linkage into the FC231 background, creating strains SMR11026 and SMR11027.

β-Galactosidase assays:

β-Galactosidase assays were performed to determine the relative expression of lacZ under the control of the different versions of the dinB promoter cloned into the low-copy plasmid pFZY (Koop et al. 1987). Cells were grown in LBH medium until mid-log phase, and the levels of β-galactosidase were determined in samples of the cultures as described (Miller 1992).

DinB Western blots:

For DinB detection on Western blots, stationary-phase cultures grown from single colonies in 5ml of M9 B1 glycerol medium for 48 hr were harvested, and cells were suspended in sample loading/lysis buffer (62.5 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol), correcting for the OD600 of the terminal culture. For 1 ml of a culture at OD600 of 2 (measured at OD600 ≤1 with diluted samples), 100 μl of sample loading buffer was used. Twenty microliters of each sample was separated by electrophoresis on a SDS polyacrylamide gel (12.5%). Proteins were transferred to a Hybond-LFP PVDF membrane (Amersham Biosciences), and the membrane was probed with a polyclonal DinB rabbit antiserum (Kim et al. 2001). A goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to the Cy5 fluorescent dye (Amersham Biosciences) was used for detection of DinB, using the Typhoon scanner (Amersham Biosciences).

Stress-induced mutagenesis assays:

Stress-induced lac reversion assays were performed as described (Harris et al. 1996) with four independent cultures of each strain. The proportion of Lac+ point mutants and lac-amplified colonies was determined by plating cells from 20 colonies of each culture for each day in which Lac+ colonies were counted (days 2–5) on LBH rifampicin X-gal plates. This allows the distinction between Lac+ point mutants (solid-blue colonies) and lac-amplified cells, given the lac-unstable sectoring-colony phenotype diagnostic of lac amplification (Hastings et al. 2000).

Determination of the mutation sequences in the lac gene:

Lac+ point mutants from experiment day 5 were identified as described above and purified on LBH plates containing rifampicin and X-Gal. A 300-nucleotide region spanning the lac +1 allele was amplified by PCR using primers lacIL2 (5′-AGGCTATTCTGGTGGCCGGA-3′ and lacD2 (5′-GCCTCTTCGCTATTACGCCAGCT-3′). DNA sequencing was performed by Seqwright (Houston) using primer lacU (5′-ATATCCCGCCGTTAACCACC-3′).

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of the dinB(oc) alleles:

To test the hypothesis that dinB might be the sole SOS gene required at induced levels for stress-induced point mutagenesis, we constructed dinB mutants in which the transcriptional repression by LexA, the repressor controlling the expression of the SOS regulon, is alleviated. This was achieved by site-directed mutagenesis of the dinB promoter, altering the binding site of the LexA repressor. These are used (see below) to express dinB at SOS-induced levels in strains in which the rest of the SOS genes are repressed. The sequences of the operator-constitutive dinB(oc) mutations that were constructed are shown in Figure 1A.

To test whether these mutations behave as bona fide operator-constitutive alleles, we fused the dinB promoter regions from the two dinB(oc) alleles to lacZ and measured the levels of β-galactosidase expression from these PdinBlacZ fusions carried in a low-copy plasmid (Figure 1B). Introduction of these plasmids into wild-type cells resulted in ∼10-fold higher lacZ expression from both PdinB(oc)lacZ fusions when compared with wild-type PdinB. This is in agreement with previous estimates of transcriptional induction of dinB during the SOS response (Courcelle et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2001). lexA51(Def) cells have no functional LexA repressor and show constitutive SOS expression (Mount 1977). We find that lacZ expression is increased in a lexA51(Def) strain when driven by the wild-type dinB promoter, but see no significant increase with the dinB(oc) promoters, showing that levels of dinB transcription similar to that achieved by true SOS derepression are achieved by the dinB(oc) mutations. The lexA51(Def) strain SMR5400 also carries a mutation in the sulA gene, which allows survival under constitutive SOS induction (Mount 1977), and a mutation in the F-encoded psiB gene, which has been shown to exert a negative effect on stress-induced mutagenesis (McKenzie et al. 2000) probably by affecting SOS induction (reviewed by Cox 2007).

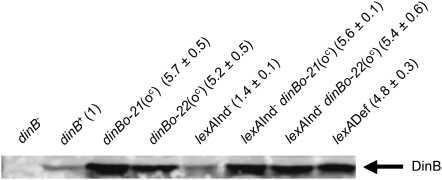

In the Lac-assay strains such as FC40 and SMR4562, dinB is present both in the chromosome and in the F′128, at which locus it is more highly expressed (Kim et al. 2001). Introduction of both dinB(oc) alleles into the episomal dinB locus results in about five- to six-fold increased DinB-protein levels in stationary-phase cells compared with an otherwise isogenic SMR4562 derivative in both wild-type and lexA3(Ind−) backgrounds (Figure 2). This indicates that both dinB(oc) alleles are functional in vivo, conferring an increased basal dinB expression. Furthermore, both alleles confer levels of expression similar to those observed in lexA51(Def) cells (Figure 2), at least in the growth conditions used by us in the stress-induced mutagenesis experiments (cells grown for 48 hr in M9 B1 glycerol minimal medium). It was noted before (Kim et al. 2001) that expression of dinB in the F′128 plasmid is higher than that from the chromosomal dinB. Our finding that both dinB(oc) alleles, when present only in the episome, increase DinB to levels similar to that observed in the lexA51(Def) strain (in which both the episomal and the chromosomal copy are constitutively highly expressed), also implies that the episomal expression is more pronounced than the chromosomal expression. To facilitate further strain construction and genetic analysis, we carried out the subsequent experiments in cells bearing a single dinB(oc) allele in the F′128 plasmid.

Figure 2.—

DinB Western blots. Stationary-phase cells grown in M9 B1 glycerol medium were harvested and analyzed using a rabbit polyclonal DinB antiserum as described (materials and methods). Values shown represent the average DinB protein levels relative to wild type determined in three independent experiments ± SEM. Similar results were obtained with Western blots performed with a DinB monoclonal antibody. Strains are the following: dinB, SMR5889; dinB+, SMR10292; dinBo-21(oc), SMR10308; dinBo-22(oc), SMR10309; lexA3(Ind−), SMR10760; lexA3(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc), SMR10761; lexA3(Ind−) dinBo-22(oc), SMR10762; and lexA(Def), SMR5400.

dinB(oc) mutations restore stress-induced point mutagenesis in SOS-off strains:

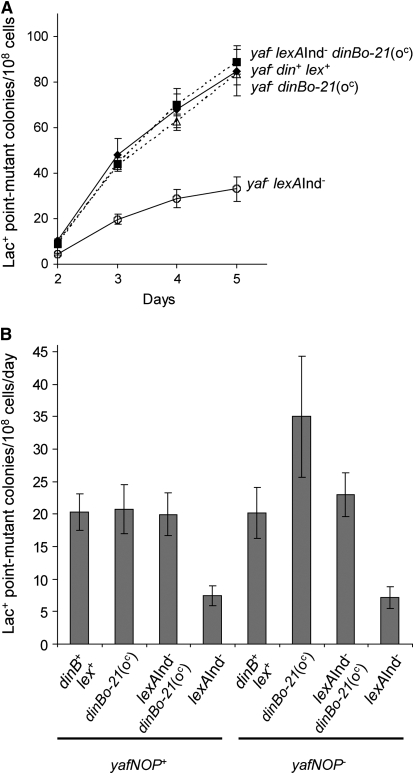

Because DinB is a key player in stress-induced mutagenesis, we wanted to examine whether dinB is the only gene required at SOS-induced levels for stress-induced point mutagenesis in the Lac assay. The SOS response is induced when DNA damage is sensed in the form of single-strand DNA (reviewed by Friedberg et al. 2005). RecA binds the single-strand DNA and becomes active as a co-protease that facilitates cleavage of the LexA repressor, resulting in upregulation of the SOS genes, including dinB. To determine whether dinB upregulation constitutes the sole role of the SOS response in stress-induced point mutagenesis, we tested the effect of the dinB(oc) alleles on lac reversion in both wild-type and lexA3(Ind−) backgrounds. The lexA3(Ind−) mutation creates an uncleavable LexA/SOS repressor such that derepression of the SOS response genes during an SOS response is prevented (Mount et al. 1972). Previously, this allele was shown to cause reduced stress-induced point mutagenesis in the Lac assay (Cairns and Foster 1991; McKenzie et al. 2000, 2001), indicating that one or more SOS-controlled genes are needed at induced levels for efficient stress-induced mutagenesis. Representative results from single experiments with each of the two dinB(oc) alleles constructed are shown in Figure 3, A and B, and quantification of the stress-induced point mutagenesis rates from multiple experiments is shown in Figure 3C. Strikingly, either allele provides a complete suppression of the phenotype of the lexA3(Ind−) strain. These results show that the reduced stress-induced mutagenesis in a lexA3(Ind−) strain is caused specifically by the failure to upregulate dinB, and not any other gene in the LexA/SOS regulon. This finding places DinB as the central SOS-regulated protein in stress-induced mutagenesis and indicates that upregulation of other SOS genes such as recA, ruvA, and ruvB beyond their constitutive levels of expression is irrelevant.

Figure 3.—

Two dinB operator-constitutive alleles restore stress-induced Lac point mutagenesis to SOS-off lexA(Ind−) cells. (A) Effect of the dinBo-21(oc) allele in stress-induced mutagenesis: a representative experiment. (B) Effect of the dinBo-22(oc) allele in stress-induced mutagenesis: a representative experiment. Note that, for both alleles, the stress-induced point mutagenesis-defective phenotype of lexA3(Ind−) cells is fully suppressed; however, overproduction of DinB with these alleles does not stimulate mutagenesis above wild-type levels. Data represent means ± SEM for four cultures. Strains are the following: dinB+ lex+, SMR10292 (solid diamonds in A and B); lexA(Ind−), SMR10760 (open circles in A and B); dinBo-21(oc), SMR10308 (solid circles in A); dinBo-22(oc), SMR10309 (solid circles in B); lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc), SMR10761 (open squares in A); and lexA(Ind−) dinBo-22(oc), SMR10672 (open squares in B). (C) Quantification of stress-induced point-mutation rates from six independent experiments, each with all genotypes done in parallel. Strains were as above except that three experiments were performed in the lexA3(Ind−) strains listed above, whereas an additional three experiments were performed, with similar results, in an independently constructed, identical set of lexA3(Ind−) strains: lexA(Ind−), SMR10314; lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc), SMR10310; and lexA(Ind−) dinBo-22(oc), SMR10311. Rates represent the increase of Lac+ point mutant colonies per day observed between days 3 and 5 of each experiment. Means ± 1 SEM are shown. P-values were obtained for pairwise comparisons by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney rank-sum test using the SYSTAT 11 statistics software by SYSTAT software and are as follows. The mutation rate of dinB+ is not different from those of dinBo-21(oc) (P = 0.699), dinBo-22(oc) (P = 0.699), lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc) (P = 0.818), or lexA(Ind−) dinBo-22(oc) (P = 0.18), but is significantly different from the rate of lexA(Ind−) (P = 0.002), and the lexA(Ind−) rate differs from those of lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc) (P = 0.002) and lexA(Ind−) dinBo-22(oc) (P = 0.002).

SOS-induced levels of DinB are not sufficient to increase stress-induced point mutagenesis:

We note that providing SOS-induced levels of DinB to all cells, with the dinB(oc) mutations, did not stimulate stress-induced mutagenesis above wild-type levels in the lexA3(Ind−) strain (Figure 3 and legend), even though normally SOS is expected to be induced spontaneously in only ∼1% of cells (Pennington and Rosenberg 2007). Neither did DinB overproduction increase mutagenesis in the wild-type genetic background (Figure 3 and legend). These results indicate that DinB upregulation by the SOS response, although required, is not sufficient to differentiate the mutating subpopulation; dinB(oc) appears not to make all cells in the population mutable. This might reflect either of two possible realities. First, in principle, it could be possible that during stress-induced mutagenesis conditions all cells are SOS-induced such that providing an operator-constitutive dinB does not provide any more DinB protein than the population of cells already has, and so does not increase mutagenesis further. This is unlikely (discussed below). Second, and more likely, it could be that during stress-induced mutagenesis only a small fraction of cells is SOS induced, as is the case for growing cells in which ∼10−2 are (Pennington and Rosenberg 2007), but that in this cell subpopulation some other condition must be met to allow mutagenesis. For example, it is likely that possession of a DNA double-strand break at which the mutagenic repair occurs (Ponder et al. 2005) is also required such that DinB upregulation alone is not sufficient.

SOS induction of other genes in the dinB operon is irrelevant for stress-induced mutagenesis:

dinB is part of a four-gene operon including dinB, yafN, yafO, and yafP (McKenzie et al. 2003). The functions of the three yaf genes are unknown. The whole operon, including the three genes downstream of dinB, is induced as part of the SOS response (Courcelle et al. 2001). Thus, in the experiments described above, all three yaf genes were also upregulated by the operator-constitutive mutations in the dinB promoter. We show that the restoration of mutability to SOS-off lexA(Ind−) cells conferred by the dinB(oc) mutations was not conferred by increased yafNOP expression, only by increased dinB expression, because it also occurred in strains carrying a deletion of the yafNOP genes in cis with (downstream of) the dinBo-21(oc) mutation in F′128 (Figure 4). Although intact yaf genes are present in the chromosome of this strain, they will be repressed by the lexA(Ind−)-encoded uncleavable LexA/SOS repressor, such that only DinB is produced at SOS-induced levels in this strain. Therefore, dinB is indeed the only gene of the SOS regulon that is required at SOS-induced levels for stress-induced mutagenesis in the Lac assay. These experiments do not rule out a role for the yaf genes (expressed at uninduced levels) in mutagenesis, a topic that will be addressed in a future publication (L. Singletary, J. Gibson, E. Tanner, G. J. McKenzie, P. L. Lee and S. M. Rosenberg, unpublished data).

Figure 4.—

Stress-induced mutagenesis proficiency in SOS-off lexA3(Ind−) cells with a dinB(oc) mutation does not require SOS induction of the yafNOP genes. (A) Representative experiment showing that deletion of the yafNOP genes in cis with dinBo-21(oc) does not affect the ability of this promoter mutation to rescue the phenotype of SOS-off lexA3(Ind−) cells. (B) Quantification of stress-induced point-mutation rates (calculated as in Figure 3) from four independent experiments. Means ± SEM are shown. P-values (calculated as in Figure 3) are as follows. For the yaf+ background, the dinB+ rate is not different from the rates observed with dinBo-21(oc) (P = 0.886) or lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc) (P = 0.686) but differs from that of lexA(Ind−) (P = 0.029), and the rate of lexA(Ind−) differs from that of lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc) (P = 0.029). Similarly, for the yaf− background, the dinB+ rate is not significantly different from the rates of dinBo-21(oc) (P = 0.114) or lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc) (P = 0.886) but differs from the lexA(Ind−) rate (P = 0.029), and the lexA(Ind−) rate differs from that of lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc) (P = 0.029). Strains are the following: dinB+, SMR10292; lexA(Ind−), SMR10760; dinBo-21(oc), SMR10308; lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc), SMR10761; yaf− dinB+ lexA+, SMR11023 (solid diamonds); yaf− dinBo-21(oc), SMR11024 (open triangles); yaf− lexA(Ind−), SMR11026 (open circles); yaf− lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc), SMR11027 (solid squares).

The mechanism of stress-induced lac reversion in dinB(oc) cells is similar to that in wild-type cells:

The results obtained show that the dinB(oc) alleles are able to rescue completely the mutagenesis-defective phenotype of lexA3(Ind−) (SOS-off) cells in stress-induced mutagenesis (Figure 3). This could result from restoration of the same stress-induced mutagenesis pathway and mechanism that operates in wild-type cells. Alternatively, it was possible that constitutive expression of dinB might activate a different mutagenesis mechanism that coincidentally yielded similar mutant frequencies in the course of several days. We provide two lines of support for the first possibility that the normal pathway and mechanism of stress-induced point mutagenesis was restored to lexA3(Ind−) (SOS-off) cells by the dinB(oc) mutations.

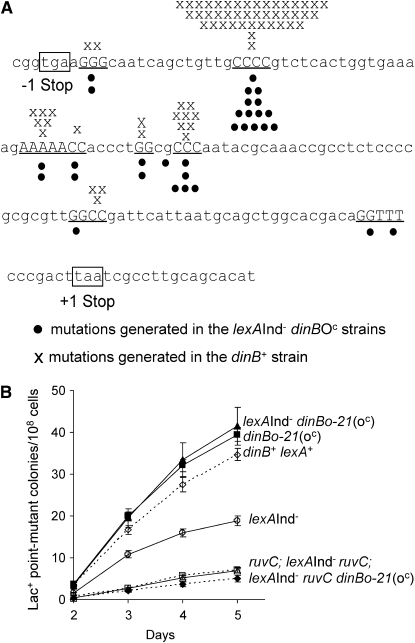

First, we find that the Lac-reversion-mutation sequences in lexA3(Ind−) dinB(oc) cells are indistinguishable from the characteristic point-mutation sequences seen normally in stress-induced point mutagenesis (in lexA+ dinB+ cells) (Figure 5A). The mutations are dominated by −1 deletions at mononucleotide repeats that occur preferentially in the same preferred hotspot sequences as observed in lexA+ dinB+ cells. This characteristic mutation sequence spectrum is highly specific and different from, for example, spontaneous reversions of this lac allele during growth, which are more heterogeneous, including −1 deletions not at mononucleotide repeats and larger frameshift-reverting additions and deletions in about half the mutations (Foster and Trimarchi 1994; Rosenberg et al. 1994). These results imply that mutations occur via a similar or the same mechanism in both genetic backgrounds, supporting the idea that the rescue of the lexA3(Ind−) phenotype by the dinB(oc) alleles restored the same mutagenesis mechanism that normally operates in lexA+ dinB+ cells.

Figure 5.—

Stress-induced mutagenesis in SOS-off lexA3(Ind−) cells with dinB(oc) alleles occurs via a mechanism similar to normal stress-induced mutagenesis in the Lac assay. (A) Sequences of Lac+ mutations are the same in lexA3(Ind−) dinB(oc) strains and in lexA+ dinB+ cells. Both sets of reversion mutations are nearly all −1 deletions in mononucleotide repeats. The positions of the −1 deletions observed in the lexA3(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc) and lexA3(Ind−) dinBo-22(oc) strains (SMR10761 and SMR10762) are shown as circles, and the position of the −1 deletions observed in lexA+ dinB+ cells (data from Foster and Trimarchi 1994 and Rosenberg et al. 1994) are marked as X's. The region shown is part of the lacIZ fusion gene present in these strains. Compensatory frameshift mutations in a 130-nt region between the two out-of-frame stop codons (boxed) can restore gene function. (B) Stress-induced mutagenesis promoted by the dinBo-21(oc) allele in the lexA3(Ind−) background requires RuvC. A representative experiment performed with four independent cultures of each strain is shown. Means ± SEM. This result was repeated twice. Strains are the following: dinB+ lex+, SMR10292 (open diamonds); dinBo-21(oc), SMR10308 (solid squares); lexA(Ind−) dinBo-21(oc), SMR10761 (solid triangles); lexA(Ind−), SMR10760 (open circles); ruvC, SMR10766 (open triangles); lexA(Ind−) ruvC, SMR10768 (open squares); and lexA(Ind−) ruvC dinBo-21(oc), SMR10767 (closed diamonds).

Second, a hallmark of stress-induced mutagenesis in the Lac assay is its requirement for homologous-recombination, double-strand-break-repair functions, including recA, recB, and ruvAB, and ruvC (Harris et al. 1994, 1996; Foster et al. 1996; He et al. 2006), because the mutagenesis results from error-prone double-strand-break-repair events (Ponder et al. 2005). Similarly, we find that deletion of ruvC reduces stress-induced mutagenesis in lexA3(Ind−) (SOS-off) cells carrying a dinB(oc) allele (Figure 5B). Thus the mutagenesis restored to lexA3(Ind−) cells by the dinB(oc) mutation requires ruvC. This supports the conclusion that a similar or the same recombination-dependent mutagenesis pathway is operating in lexA3(Ind−) dinB(oc) cells as is normal in cells wild-type for lexA and dinB.

DISCUSSION

How stress responses confer temporal regulation of mutagenesis:

The coupling of mutagenesis programs to cellular stress responses observed in bacterial and eukaryotic cells (reviewed in the Introduction and by Galhardo et al. 2007) provides a temporal regulation of mutagenesis, limiting mutagenesis to times of stress. This may potentially accelerate genetic change, and thus the ability to evolve, specifically when cells and organisms are maladapted to their environments, i.e., are stressed. Here we demonstrate that, in the case of the E. coli Lac assay, the requirement for the SOS stress response can be deconvoluted to the need for induction of one specific gene, dinB. A number of other stress responses have been shown to upregulate mutagenesis, such as the RpoS response in E. coli, Salmonella, and Pseudomonas; the stringent response in E. coli and B. subtilis; the competence response of B. subtilis; and two human responses to hypoxic stress (see Introduction). All of these modulate the expression of tens to hundreds of different genes. It is not yet known whether any other of these stress responses can be narrowed down to relevant effects on one or a few genes.

Roles of SOS in other stress-induced mutagenesis mechanisms:

The SOS response is a major upregulator of mutagenesis during stress conditions but may not function identically in each case. For example, the SOS response is required for phage λ untargeted mutagenesis (Ichikawa-Ryo and Kondo 1975), stress-induced point mutagenesis in E. coli in the Lac assay (McKenzie et al. 2000), ciprofloxacin (antibiotic)-resistance mutagenesis induced by exposure to ciprofloxacin (Cirz et al. 2005), mutagenesis in aging colonies in a laboratory E. coli strain (Taddei et al. 1995), and bile-resistance mutagenesis in Salmonella (Prieto et al. 2006). Although DinB is required for λ untargeted mutagenesis (Kim et al. 1997) and for Salmonella bile-resistance mutagenesis (Prieto et al. 2006), it is not yet known whether the SOS requirement in either case is based on DinB upregulation. In the ciprofloxacin-induced mutagenesis, the SOS-controlled DNA polymerases DinB, Pol II, and Pol V are all required, as are the double-strand-break-repair genes, including SOS-regulated recA, ruvA, and ruvB (Cirz et al. 2005). Part of this mutation pathway's requirement for SOS is likely to be for production of DNA Pol V (Cirz et al. 2005) because this polymerase is required for mutagenesis and is produced virtually not at all without an SOS response (reviewed by Nohmi 2006). It is not yet known whether upregulation of any, all, or none of the other two SOS-controlled DNA polymerases additionally account for the requirement for an SOS response for ciprofloxacin-induced mutagenesis. Conversely, in the Lac assay, we measure frameshift reversion, which DinB promotes but Pols II and V do not, whereas the ciprofloxacin-induced mutations are base substitutions, which all three SOS polymerases promote (Cirz and Romesberg 2007). Cirz and Romesberg (2007) have pointed out that the mutagenesis pathway in the Lac system might be identical to that in ciprofloxacin-resistance mutagenesis and might also require Pols II and V if base substitution mutations were assayed. In a different assay system, mutagenesis in aging colonies required an SOS response, did not require DinB, and required Pol I instead (Taddei et al. 1997). Therefore, in the mutagenesis mechanism operating during that stress, the SOS requirement must be for some other function. Thus, although the SOS response is required for multiple examples of stress-inducible mutagenesis, its means of promoting mutagenesis in at least some of these different stress circumstances is different.

SOS induction of DinB is necessary but not sufficient for stress-induced mutability and for differentiation of a hypermutable cell subpopulation:

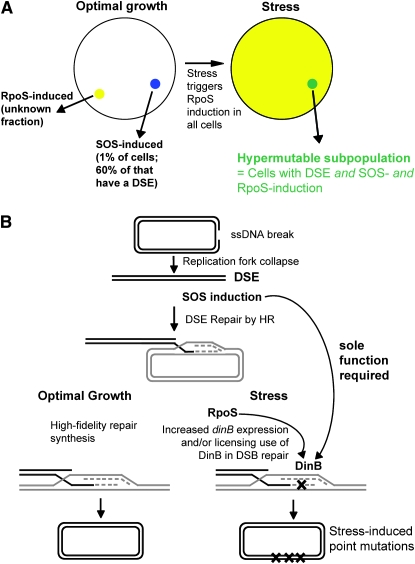

Several lines of evidence indicate that although SOS induction of DinB is necessary, it is not sufficient for creating the transient mutable state in which most Lac reversions occur (Gonzales et al. 2008). Rather, the evidence also supports a model in which at least three events must occur: (1) a double-strand break and its repair, (2) SOS induction, and (3) induction of the RpoS stationary-phase and general stress response. The concerted induction of these stress responses in cells bearing double-strand DNA ends (DSEs) is proposed to differentiate the hypermutable subpopulation, as depicted in Figure 6A.

Figure 6.—

Models for the role of SOS induction and DinB in differentiation of a hypermutable cell subpopulation and double-strand-break-repair-associated mutagenesis during stress. (A) Venn-diagram model of cell subpopulations that overlap to produce a transiently hypermutable cell subpopulation. In this model (modified from Galhardo et al. 2007), differentiation of a HMS (green) is proposed to occur when three conditions are met: (1) induction of the SOS response in cells bearing (2) a double-strand break or a DSE (blue) and (3) induction of the RpoS regulon (yellow) by suboptimal growth conditions. During stress, all cells induce RpoS and, we suggest, the fraction of cells bearing both a DSE and SOS induction [∼6 × 10−3 of growing cells (Pennington and Rosenberg 2007)] might remain roughly constant. In this model, the dinB(oc) mutations, which upregulate DinB in all cells, would not increase HMS size because the DSEs are not available in all cells. (B) Mutagenic double-strand-break repair during stress. Ponder et al. (2005) showed that repair of a double-strand break is a high-fidelity, nonmutagenic process in unstressed cells (left) but switches to a mutagenic mode during stress under the control of the RpoS general stress response (right). This process requires a DSE and its repair; induction of the SOS response (McKenzie et al. 2000), which we show here, is solely to provide DinB upregulation, and induction of the RpoS regulon (Ponder et al. 2005). Some as yet-unknown function regulated by the RpoS response licenses the use of DinB in those conditions. This function could be the documented increase in DinB expression (Layton and Foster 2003) or the induction of another regulatory factor, or a combination of both. ssDNA, single-strand DNA; HR, homologous recombination; X's, DNA polymerase errors/mutations; parallel lines, double-strand DNA; dashed lines, newly synthesized DNA strands.

The first evidence for this model comes from experiments in which DNA double-strand breaks were delivered to the DNA by expression of the I-SceI double-strand endonuclease in vivo (Ponder et al. 2005). DinB-dependent, stress-induced mutagenesis was stimulated >1000-fold near the DSBs, but only weakly (3-fold) in a another DNA molecule (with no DSB) in the same cell. SOS is induced robustly by I-SceI-induced DSBs (Pennington and Rosenberg 2007). Therefore, these results indicate that the SOS-mediated DinB upregulation caused by I-SceI-mediated DNA cleavage was not sufficient for mutagenesis. A DSB was also required locally. The mutations appear to occur in acts of error-prone DSB repair (Ponder et al. 2005). Figure 6B shows a model for such mutagenic double-strand-break repair occurring in stressed cells.

Second, RpoS is required for stress-induced Lac reversion (Layton and Foster 2003; Lombardo et al. 2004). Moreover, in the study using I-SceI-induced DSBs (Ponder et al. 2005), the DinB-dependent DSB-associated mutagenesis was provoked only in cells that either were in stationary phase or were expressing the RpoS stationary-phase and general stress-response transcriptional activator inappropriately during log phase. Again, because the SOS response is induced efficiently by I-SceI-mediated double-strand breakage (Pennington and Rosenberg 2007), this implies that repair of a DSB under the influence of the SOS response is also not sufficient for DinB-dependent mutagenesis; RpoS must also be induced. Additionally, although some kinds of DNA damage can induce RpoS (Merrikh et al. 2009), if it occurs in these experimental conditions, damage induction of RpoS appears not to be sufficient for mutagenesis; another RpoS-inducing input must contribute.

Finally, in growing cells, only ∼1% of cells are SOS induced spontaneously (Pennington and Rosenberg 2007), and in this study we observed that making every cell in the population experience SOS-induced levels of DinB production, using the dinB(oc) alleles, did not increase stress-induced mutagenesis in otherwise wild-type cells (Figure 3). This could mean either of two things:

Unlike growing cells, in stationary phase, all of the cells are already SOS induced, and so the dinB(oc) alleles do not change the number of cells expressing DinB or the DinB levels in most cells. This possibility is unlikely, given the large increase in DinB levels that we observed with the dinB(oc) alleles measured in stationary-phase cells (Figure 2).

More plausibly, the data imply that, even though the dinB(oc) alleles confer SOS-induced levels of DinB to all cells, this is not sufficient for mutagenesis. These data support the model in which a DNA double-strand break and its repair, an RpoS response, and an SOS response (shown to act solely via DinB production) are all required for stress-induced point mutagenesis (Figure 6, A and B). We note that if all cells had become hypermutable when DinB was overproduced in all cells, mutation rate would have been higher than normal because the hypermutable cells would no longer be a small subpopulation. This was not observed (Figures 3 and 4).

Role of SOS/DinB in a hypermutable cell subpopulation:

We previously suggested a model for the origin of the hypermutable cell subpopulation that appears to underlie most double-strand-break-repair-associated stress-induced point mutagenesis (Gonzales et al. 2008) on the basis of three requirements for stress-induced mutability discussed above: a genomic DSB/DSE (and its repair), an SOS response, and an RpoS response (Galhardo et al. 2007). The simultaneous occurrence of these three events is proposed to differentiate the hypermutating cells. It is unknown what fraction of the cells in a stationary population experience an SOS response, but ∼1% of the cells in log-phase cultures display spontaneous SOS induction, ∼60% of those (∼6 × 10−3) due to a spontaneous DSB/DSE (Pennington and Rosenberg 2007). When these cells enter the stationary phase, RpoS is likely to be induced in all of them (Hengge-Aronis 2002). Thus, if the numbers for growing cells hold, then the ∼6 × 10−3 of cells with a DSB and an SOS response would become the HMS when RpoS induction occurred in the whole population in stationary phase (Figure 6A). We can now refine this model to note that the sole component of the SOS response required would be DinB upregulation.

The additional requirement for RpoS—to license the use of DinB in error-prone DSB/DSE repair (shown by Ponder et al. 2005)—could be based either solely on RpoS upregulation of DinB or on RpoS-controlled expression of other factors that permit DinB use (Figure 6B). The SOS and RpoS responses increase DinB expression ∼10-fold and 2- to 3-fold, respectively (Kim et al. 2001; Layton and Foster 2003). The identities of potential DinB-licensing factors in the RpoS regulon are not yet known. This control would provide a restriction of the mutagenesis to periods of stress, and only to those few cells with a DSB/DSE. The restriction of mutagenesis to a cell subpopulation may allow clonal populations to hedge their bets during adaptation to changing environments, both conserving the original genome sequence, which is well adapted to the previous environment and useful if resources become available again suddenly, and simultaneously exploring the new adaptive landscape in the subpopulation.

Regulation of DinB mutator activity:

In many other assay systems in which DinB-dependent mutagenesis has been observed, stress responses other than, or in addition to, SOS are required. In Salmonella bile-induced resistance mutagenesis, which is DinB dependent, the SOS and RpoS responses are required (J. Casadesus, personal communication, and Prieto et al. 2006). In B. subtilis starvation-associated mutagenesis, the ComK competence stress response is required for the DinB-dependent mutagenesis (Sung and Yasbin 2002). In E. coli, β-lactam antibiotics induce dinB transcription independently of SOS (Perez-Capilla et al. 2005). P. putida DinB-dependent, stress-induced mutagenesis requires RpoS (Saumaa et al. 2002). It is not known whether any stress response other than SOS is required for DinB-dependent, ciprofloxacin-induced resistance mutagenesis (Cirz et al. 2005). Thus, it is plausible that DinB-dependent mutagenesis might usually require more than one stress-response input to occur. Although effects of DinB in SOS mutagenesis of E. coli (Kuban et al. 2006) have been observed, it is not known whether the DinB-dependent mutations may have arisen in cells also induced for RpoS or another stress response simultaneously.

What factors modulate DinB mutator activity? As a translesion DNA polymerase that inserts bases opposite several otherwise replication-blocking DNA adducts, DinB performs this role mostly in a high-fidelity fashion (Jarosz et al. 2006; Bjedov et al. 2007; Godoy et al. 2007). This, and the existence of dinB mutations that separate translesion from mutagenic functions (Godoy et al. 2007), imply that mutator activity occurs during synthesis that is not part of translesion synthesis (although it does occur during DSB repair; Ponder et al. 2005). Alternatively, DinB mutator activity could be taking place at sites of yet-unidentified DNA lesions.

A recent study implicated the SOS-induced UmuD protein as a candidate to inhibit DinB mutagenic potential during SOS induction (Godoy et al. 2007). UmuD is produced virtually only during an SOS response (Courcelle et al. 2001). Consequently, UmuD is not expected to be present in lexA(Ind−) dinB(oc) cells, but stress-induced mutation rates were similar to those in wild-type cells (Figures 3 and 4). Therefore, UmuD appears not to inhibit DinB in its role in stress-induced point mutagenesis. Other levels of control are likely to exist.

One case of strongly DinB-dependent mutagenesis thought to occur with only one stress-response input in physiological conditions is SOS-mediated untargeted mutagenesis of phage λ (Kim et al. 1997). Under those conditions, mutagenesis of the phage DNA is heavily dependent on DinB, presumably relying on the physiological levels of dinB expression achieved in vivo during SOS induction. It is interesting to note that extensive double-strand-end-initiated recombination between the multiple copies of the phage DNA is expected to occur during a lytic cycle (Thaler and Stahl 1988). Those might be the sites of mutagenic action of DinB. Nevertheless, it is not known whether other factors, λ or host encoded, might also play a role in that process. Another example is the recent finding of increased DinB-dependent mutagenesis in cells lacking the ClpXP protease (Al Mamun and Humayun 2009). RpoS does not seem to be involved in the observed mutagenesis. However, the lack of a major protease is likely to have many pleiotropic effects, and there remains the possibility that other responses, which foster DinB activity, are triggered in those cells.

Evolution of stress-induced mutagenesis pathways:

The occurrence of many different molecular mechanisms of stress-inducible mutagenesis (reviewed in the Introduction and by Galhardo et al. 2007), and even of mechanisms by which a single stress response such as SOS promotes mutagenesis under different stress circumstances, suggests that these mutagenesis programs have evolved many times at least somewhat independently. This is also suggested by a survey of starvation-stress-inducible mutability in 787 E. coli natural isolates (Bjedov et al. 2003). Those authors found that whereas >80% of the natural isolates displayed stress-inducible mutator activity, the ability to do so correlated well with ecological niche and poorly with strain phylogeny, suggesting multiple recent evolutions of the stress-inducible mutagenesis pathways. We have suggested that stress-inducible mutagenesis mechanisms are both somewhat varied and recently acquired because they confer a benefit to cells that is under periodic (alternating positive and negative) second-order selection (Galhardo et al. 2007). That is, these pathways are useful and selected in changing environments in which adaptation is promoted by mutability and responsiveness and superfluous and perhaps costly in static environments. Despite the variability and potential multiple origins, the basic themes of the regulation of mutability temporally by stress responses, and potentially spatially in genomes (Galhardo et al. 2007), are widespread and appear to be potentially important evolutionary strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kenneth Hu for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (18201010) (T.N.), and the National Institutes of Health grants R01-GM-64022 (P.J.H.), and R01-GM53158 (S.M.R.). R.S.G. was supported in part by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Pew Latin American Fellows Program.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.100735/DC1.

References

- Al Mamun, A. A., and M. Z. Humayun, 2009. Spontaneous mutagenesis is elevated in protease-defective cells. Mol. Microbiol. 71 629–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindra, R. S., and P. M. Glazer, 2007. Co-repression of mismatch repair gene expression by hypoxia in cancer cells: role of the Myc/Max network. Cancer Lett. 252 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindra, R. S., P. J. Schaffer, A. Meng, J. Woo, K. Maseide et al., 2004. Down-regulation of Rad51 and decreased homologous recombination in hypoxic cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 8504–8518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjedov, I., O. Tenaillon, B. Gerard, V. Souza, E. Denamur et al., 2003. Stress-induced mutagenesis in bacteria. Science 300 1404–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjedov, I., C. Nag Dasgupta, D. Slade, S. Le Blastier, M. Selva et al., 2007. Involvement of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV in tolerance of cytotoxic alkylating DNA lesions in vivo. Genetics 176 1431–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, J., and P. L. Foster, 1991. Adaptive reversion of a frameshift mutation in Escherichia coli. Genetics 128 695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirz, R. T., and F. E. Romesberg, 2007. Controlling mutation: intervening in evolution as a therapeutic strategy. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42 341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirz, R. T., J. K. Chin, D. R. Andes, V. de Crecy-Lagard, W. A. Craig et al., 2005. Inhibition of mutation and combating the evolution of antibiotic resistance. PLoS Biol. 3 e176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courcelle, J., A. Khodursky, B. Peter, P. O. Brown and P. C. Hanawalt, 2001. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 158 41–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M. M., 2007. Regulation of bacterial RecA protein function. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42 41–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner, 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 6640–6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez De Henestrosa, A. R., T. Ogi, S. Aoyagi, D. Chafin, J. J. Hayes et al., 2000. Identification of additional genes belonging to the LexA regulon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 35 1560–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, P. L., and J. M. Trimarchi, 1994. Adaptive reversion of a frameshift mutation in Escherichia coli by simple base deletions in homopolymeric runs. Science 265 407–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, P. L., J. M. Trimarchi and R. A. Maurer, 1996. Two enzymes, both of which process recombination intermediates, have opposite effects on adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli. Genetics 142 25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg, E. C., G. C. Walker, W. Siede, R. D. Wood, R. A. Schultz et al., 2005. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- Galhardo, R. S., P. J. Hastings and S. M. Rosenberg, 2007. Mutation as a stress response and the regulation of evolvability. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42 399–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, V. G., F. S. Gizatullin and M. S. Fox, 2000. Some features of the mutability of bacteria during nonlethal selection. Genetics 154 49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, V. G., D. F. Jarosz, S. M. Simon, A. Abyzov, V. Ilyin et al., 2007. UmuD and RecA directly modulate the mutagenic potential of the Y family DNA polymerase DinB. Mol. Cell 28 1058–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gomez, J. M., J. Blazquez, F. Baquero and J. L. Martinez, 1997. H-NS and RpoS regulate emergence of Lac Ara+ mutants of Escherichia coli MCS2. J. Bacteriol. 179 4620–4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, C. P., L. Hadany, R. G. Ponder, M. Price, P. J. Hastings et al., 2008. Mutability and importance of a hypermutable cell subpopulation that produces stress-induced mutants in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 4 e10000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R. S., S. Longerich and S. M. Rosenberg, 1994. Recombination in adaptive mutation. Science 264 258–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R. S., K. J. Ross and S. M. Rosenberg, 1996. Opposing roles of the Holliday junction processing systems of Escherichia coli in recombination-dependent adaptive mutation. Genetics 142 681–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, P. J., 2007. Adaptive amplification. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42 271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, P. J., H. J. Bull, J. R. Klump and S. M. Rosenberg, 2000. Adaptive amplification: an inducible chromosomal instability mechanism. Cell 103 723–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, A. S., P. R. Rohatgi, M. N. Hersh and S. M. Rosenberg, 2006. Roles of E. coli double-strand-break-repair proteins in stress-induced mutation. DNA Rep. 5 258–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge-Aronis, R., 2002. Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the sigma(S) (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66 373–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa-Ryo, H., and S. Kondo, 1975. Indirect mutagenesis in phage lambda by ultraviolet preirradiation of host bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 97 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilves, H., R. Horak and M. Kivisaar, 2001. Involvement of sigma(S) in starvation-induced transposition of Pseudomonas putida transposon Tn4652. J. Bacteriol. 183 5445–5448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz, D. F., V. G. Godoy, J. C. Delaney, J. M. Essigmann and G. C. Walker, 2006. A single amino acid governs enhanced activity of DinB DNA polymerases on damaged templates. Nature 439 225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. R., G. Maenhaut-Michel, M. Yamada, Y. Yamamoto, K. Matsui et al., 1997. Multiple pathways for SOS-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli: an overexpression of dinB/dinP results in strongly enhancing mutagenesis in the absence of any exogenous treatment to damage DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94 13792–13797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. R., K. Matsui, M. Yamada, P. Gruz and T. Nohmi, 2001. Roles of chromosomal and episomal dinB genes encoding DNA pol IV in targeted and untargeted mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, S., M. R. Valentine, P. Pham, M. O'Donnell and M. F. Goodman, 2002. Fidelity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV. Preferential generation of small deletion mutations by dNTP-stabilized misalignment. J. Biol. Chem. 277 34198–34207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koop, A. H., M. E. Hartley and S. Bourgeois, 1987. A low-copy-number vector utilizing beta-galactosidase for the analysis of gene control elements. Gene 52 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiji, M., K. K. To, S. Hammer, K. Kumamoto, A. L. Harris et al., 2005. HIF-1alpha induces genetic instability by transcriptionally downregulating MutSalpha expression. Mol. Cell 17 793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuban, W., P. Jonczyk, D. Gawel, K. Malanowska, R. M. Schaaper et al., 2004. Role of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV in in vivo replication fidelity. J. Bacteriol. 186 4802–4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuban, W., M. Banach-Orlowska, R. M. Schaaper, P. Jonczyk and I. J. Fijalkowska, 2006. Role of DNA polymerase IV in Escherichia coli SOS mutator activity. J. Bacteriol. 188 7977–7980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugelberg, E., E. Kofoid, A. B. Reams, D. I. Andersson and J. R. Roth, 2006. Multiple pathways of selected gene amplification during adaptive mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 17319–17324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton, J. C., and P. L. Foster, 2003. Error-prone DNA polymerase IV is controlled by the stress-response sigma factor, RpoS, in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 50 549–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton, J. C., and P. L. Foster, 2005. Error-prone DNA polymerase IV is regulated by the heat shock chaperone GroE in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187 449–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, M. J., I. Aponyi and S. M. Rosenberg, 2004. General stress response regulator RpoS in adaptive mutation and amplification in Escherichia coli. Genetics 166 669–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longerich, S., A. M. Galloway, R. S. Harris, C. Wong and S. M. Rosenberg, 1995. Adaptive mutation sequences reproduced by mismatch repair deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92 12017–12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magner, D. B., M. D. Blankschien, J. A. Lee, J. M. Pennington, J. R. Lupski et al., 2007. RecQ promotes toxic recombination in cells lacking recombination intermediate-removal proteins. Mol. Cell 26 273–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, G. J., R. S. Harris, P. L. Lee and S. M. Rosenberg, 2000. The SOS response regulates adaptive mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 6646–6651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, G. J., P. L. Lee, M. J. Lombardo, P. J. Hastings and S. M. Rosenberg, 2001. SOS mutator DNA polymerase IV functions in adaptive mutation and not adaptive amplification. Mol. Cell 7 571–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, G. J., D. B. Magner, P. L. Lee and S. M. Rosenberg, 2003. The dinB operon and spontaneous mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185 3972–3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrikh, H., A. E. Ferrazzoli, A. Bougdour, A. Olivier-Mason and S. T. Lovett, 2009. A DNA damage response in Escherichia coli involving the alternative sigma factor, RpoS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106 611–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova, V. T., R. S. Bindra, J. Yuan, D. Campisi, L. Narayanan et al., 2003. Decreased expression of the DNA mismatch repair gene Mlh1 under hypoxic stress in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 3265–3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. H., 1992. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harobr, NY.

- Mount, D. W., 1977. A mutant of Escherichia coli showing constitutive expression of the lysogenic induction and error-prone DNA repair pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74 300–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount, D. W., K. B. Low and S. J. Edmiston, 1972. Dominant mutations (lex) in Escherichia coli K-12 which affect radiation sensitivity and frequency of ultraviolet light-induced mutations. J. Bacteriol. 112 886–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohmi, T., 2006. Environmental stress and lesion-bypass DNA polymerases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60 231–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, J. M., and S. M. Rosenberg, 2007. Spontaneous DNA breakage in single living Escherichia coli cells. Nat. Genet. 39 797–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Capilla, T., M. R. Baquero, J. M. Gomez-Gomez, A. Ionel, S. Martin et al., 2005. SOS-independent induction of dinB transcription by beta-lactam-mediated inhibition of cell wall synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187 1515–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder, R. G., N. C. Fonville and S. M. Rosenberg, 2005. A switch from high-fidelity to error-prone DNA double-strand break repair underlies stress-induced mutation. Mol. Cell 19 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, S. C., and R. M. Wartell, 2001. Different characteristics distinguish early versus late arising adaptive mutations in Escherichia coli FC40. Mutat. Res. 473 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, A. I., F. Ramos-Morales and J. Casadesus, 2006. Repair of DNA damage induced by bile salts in Salmonella enterica. Genetics 174 575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosche, W. A., and P. L. Foster, 1999. The role of transient hypermutators in adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 6862–6867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, S. M., S. Longerich, P. Gee and R. S. Harris, 1994. Adaptive mutation by deletions in small mononucleotide repeats. Science 265 405–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, S. M., C. Thulin and R. S. Harris, 1998. Transient and heritable mutators in adaptive evolution in the lab and in nature. Genetics 148 1559–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner, R., A. Murray and N. Huda, 1999. Is there a link between mutation rates and the stringent response in Bacillus subtilis? Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 870 418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saumaa, S., A. Tover, L. Kasak and M. Kivisaar, 2002. Different spectra of stationary-phase mutations in early-arising versus late-arising mutants of Pseudomonas putida: involvement of the DNA repair enzyme MutY and the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. J. Bacteriol. 184 6957–6965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack, A., P. C. Thornton, D. B. Magner, S. M. Rosenberg and P. J. Hastings, 2006. On the mechanism of gene amplification induced under stress in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 2 e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf, J. D., and P. L. Foster, 2005. Polyphosphate kinase regulates error-prone replication by DNA polymerase IV in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 57 751–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, H. M., and R. E. Yasbin, 2002. Adaptive, or stationary-phase, mutagenesis, a component of bacterial differentiation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184 5641–5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei, F., I. Matic and M. Radman, 1995. cAMP-dependent SOS induction and mutagenesis in resting bacterial populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92 11736–11740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei, F., J. A. Halliday, I. Matic and M. Radman, 1997. Genetic analysis of mutagenesis in aging Escherichia coli colonies. Mol. Gen. Genet. 256 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, D. S., and F. W. Stahl, 1988. DNA double-chain breaks in recombination of phage lambda and of yeast. Annu. Rev. Genet. 22 169–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torkelson, J., R. S. Harris, M. J. Lombardo, J. Nagendran, C. Thulin et al., 1997. Genome-wide hypermutation in a subpopulation of stationary-phase cells underlies recombination-dependent adaptive mutation. EMBO J. 16 3303–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, E., M. Kim, K. Hu, H. Yang and J. H. Miller, 2004. Polymerases leave fingerprints: analysis of the mutational spectrum in Escherichia coli rpoB to assess the role of polymerase IV in spontaneous mutation. J. Bacteriol. 186 2900–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B. E., A. Longacre and J. M. Reimers, 1999. Hypermutation in derepressed operons of Escherichia coli K12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 5089–5094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B., H. Cao, Y. Jiang, H. Hong and Y. Wang, 2008. Efficient and accurate bypass of N2-(1-carboxyethyl)-2′-deoxyguanosine by DinB DNA polymerase in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 8679–8684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]