Abstract

Aberrant DNA hypermethylation contributes to myeloid leukemogenesis by silencing structurally normal genes involved in hematopoiesis. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression by targeting protein-coding mRNAs. Recently, miRNAs have been shown to play a role as both targets and effectors in gene hypermethylation and silencing in malignant cells. In the current study, we showed that enforced expression of miR-29b in acute myeloid leukemia cells resulted in marked reduction of the expression of DNA methyltransferases DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B at both RNA and protein levels. This in turn led to decrease in global DNA methylation and reexpression of p15INK4b and ESR1 via promoter DNA hypomethylation. Although down-regulation of DNMT3A and DNMT3B was the result of a direct interaction of miR-29b with the 3′ untranslated regions of these genes, no predicted miR-29b interaction sites were found in the DNMT1 3′ untranslated regions. Further experiments revealed that miR-29b down-regulates DNMT1 indirectly by targeting Sp1, a transactivator of the DNMT1 gene. Altogether, these data provide novel functional links between miRNAs and aberrant DNA hypermethylation in acute myeloid leukemia and suggest a potentially therapeutic use of synthetic miR-29b oligonucleotides as effective hypomethylating compounds.

Introduction

DNA methylation consists of an enzymatic addition of a methyl group at the carbon 5 position of cytosine in the context of the sequence 5′-cytosine-guanosine (CpG) and is mediated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs).1 The promoter regions of approximately 50% of human genes contain regions of DNA with a cytosine and guanine content greater than expected (so-called CpG islands) that, once hypermethylated, mediate gene transcriptional silencing.2 Distinct roles in genomic methylation have been reported for DNMT isoforms. Whereas DNMT1 preferentially replicates already existing methylation patterns, DNMT3A and 3B are responsible for establishing de novo methylation.2 Silencing of structurally normal tumor suppressor genes by aberrant DNA hypermethylation has been reported in hematologic malignancies, including subsets of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).3,4 Although the mechanisms leading to aberrant DNA hypermethylation remain to be fully elucidated, increased levels of DNMT1 and DNMT3A and 3B have been observed in malignant myeloid blasts compared with normal bone marrow (BM) mononuclear cells (MNCs), suggesting that DNMT overexpression contributes to gene promoter hypermethylation and in turn to leukemogenesis.4

Growing evidence supports a role for microRNAs (miRNAs) as both targets and effectors in aberrant mechanisms of DNA hypermethylation.5,6 miRNAs are noncoding RNAs of 19 to 25 nucleotides in length that regulate gene expression by inducing translational inhibition or cleavage of their target mRNAs through base pairing at partially or fully complementary sites.7 Several groups have shown that miRNAs are altered in human malignancies and can function as tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes through expression regulation of their target genes.7 Similar to tumor suppressor genes, miRNAs with tumor suppressor activity are often located in deleted genomic areas or are silenced by mutations or promoter hypermethylation in malignant cells.5,8–10 Saito et al recently demonstrated that miR-127 is silenced by promoter DNA hypermethylation and down-regulated in human bladder cancer and reexpressed by treatment with hypomethylating agents; this coincided with down-regulation of the oncogene BCL6, which is a bona fide target of miR-127.5

Our group recently reported that miRNAs are also involved in the control of DNA methylation by targeting the DNA methylation machinery.6 We showed that, in lung cancer, the miR-29 family directly targets DNMT3A and 3B,6 thereby leading to down-regulation of these genes, reduction of global DNA methylation (GDM), and reexpression of the DNA hypermethylated and silenced tumor suppressor genes FHIT and WWOX. Nevertheless, whether down-regulation of DNMT3A and 3B by enforced expression of miR-29 suffices in inducing efficient DNA hypomethylation in malignant cells or rather additional mechanisms are necessary to attain such an effect remains to be fully elucidated.

By testing the hypomethylating role of miR-29b in myeloid leukemogenesis, in the current study we demonstrated that expression of miR-29b promotes DNA hypomethylation not only through direct targeting of DNMT3A and 3B but also by decreasing the DNMT1 expression indirectly via down-regulation of Sp1, a known transactivating factor of the DNMT1 gene. These results therefore support a previously unreported role of miRNAs in aberrant DNA methylation in AML and provide a pharmacologic rationale for the use of synthetic miR-29b as an efficient approach for therapeutic DNA hypomethylation of leukemic blasts.

Methods

Patients and cell lines

These AML cell lines, Kasumi-1, MV4-11, and K562, were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). We chose cell lines with either low (MV4-11) or absent miR-29b (K562 and Kasumi-1). MNCs from BM samples with more than 70% blasts from 3 untreated AML patients were obtained from the Ohio State University (OSU) Leukemia Tissue Bank. Morphologic (French-American-British [FAB] classification) and cytogenetics/molecular characteristics of these primary AML samples were as follows: patient 1: FAB M2, normal karyotype, FLT3 internal tandem duplications negative; patient 2: FAB M2, complex karyotype (> 5 aberrations, including −7); patient 3: FAB M2, normal karyotype. Patients signed an informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki to store and use their tissue for discovery studies according to OSU institutional guidelines under protocols approved by the OSU Institutional Review Board.

Cell culture and transfection

Kasumi-1, MV4-11, and K562 cell lines were grown in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum or 15% fetal bovine serum (Kasumi-1) at 37°C. MNCs from BM AML samples were prepared by Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) gradient centrifugation and cultured with serum-free expansion medium (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) supplemented with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (50 ng/mL), interleukin-3 (20 ng/mL), interleukin-6 (20 ng/mL), and stem cell factor (100 g/mL) at 37°C. Synthetic pre-miR-29b oligonucleotides or scrambled oligonucleotides used as negative controls (Ambion, Austin, TX) at a final concentration of 50 nM were introduced into primary blasts or cell lines by nucleoporation (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfected cell lines were harvested at 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours. Primary blasts were harvested 24 hours after transfection. Cells were placed in cell lysis buffer for protein assay or in Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for RNA studies. MV4-11 cells were treated with 2.5 μM decitabine (Sigma-Aldrich) or phosphate-buffered saline (Sigma-Aldrich) for 72 hours.

miR-29b lentivirus infection

The miR-29b lentivirus is a feline immunodeficiency virus-based construct purchased from Systems Biosciences (Mountain View, CA). This construct consists of the stem loop structure of miR-29b-1 and 200 base pairs of upstream and downstream flanking genomic sequence cloned into the pMIF-cGFP-Zeo-miR plasmid (catalog no. MIFCZ301A-1). Packaging of the miR-29b constructs in pseudoviral particles was performed using the pPACKH1 packaging plasmid mix (catalog no. LV500A-1) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Systems Biosciences). Lentivirus rapid titer polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit (catalog no. LV950A-1) was used to measure the copy numbers and determine the multiplicity of infection to perform experiments. Kasumi-1 cells (106) were infected with the miR-29b lentivirus with an efficiency of approximately 40% as determined by fluorescence microscopy. Empty lentivirus was used as a control for the experiments.

Cell differentiation assay

Kasumi-1 cells were infected with empty vector or miR-29b lentivirus, flow cytometry sorted after 48 hours (using GFP expression, sorting efficiency 90%), followed by assessment of CD11b expression by flow cytometry at 3 and 6 days after infection. Approximately 5 × 105 kasumi-1 cells were washed twice and incubated for 1 hour at 4° in the dark with anti-CD11b (BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Appropriate isotype control was used as well.

Quantitative real-time-PCR

The single-tube TaqMan miRNA assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to detect and quantify mature miRNAs as described.11 To detect Sp1, DNMT1, DNMT3A and 3B, p15INK4b, and ESR1 mRNA levels, we used the TaqMan gene expression assay. Raw values were normalized using let-7i (for miR-29b) and 18S (for DNMTs, Sp1 p15INK4b, and ESR1 genes) as internal controls. Let-7i was selected because of its lack of expression variability among more than 200 AML patients tested in a previous study by our group.12 Real-time PCR reactions were performed in triplicate, including no-template controls. Relative expression was calculated using the comparative Ct method.13

Northern blotting

Northern blotting was performed as previously described.8 Briefly, total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA samples (20 μg) were run on 12% polyacrylamide denaturing (urea) precast gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and then transferred onto Hybond-n_membrane (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). The hybridization was performed with α-32P miR-29b labeled probes overnight at 42°. The miR-29b probe sequence was the complementary one to the mature miR-29b. As a loading control, we used 5S rRNA stained with ethidium bromide and U6 hybridization after stripping the filter as previously described.8

Western blotting

Western blot was performed as previously described.14 Antibodies anti-Sp1, -DNMT1, -DNMT3A, and -DNMT3B were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Equivalent gel loading was confirmed by probing with antibodies against β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Sp1 silencing

A pool of 2 Sp1 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were obtained commercially (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Approximately 100 nM of Sp1 siRNA or control oligonucleotide siRNA was transfected in K562 cells by nucleoporation as previously described in cell culture and transfection methods.

Luciferase assays

The 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of the Sp1, DNMT1, and DNMT3A and 3B gene were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA and inserted into the pGL3 control vector (Promega, Madison, WI), using the XBA1 site immediately downstream from the stop codon of luciferase. The primer sets used were: Sp1 FW 5′-CCTTCAGGGATTTCCAACTG-3′ and Sp1 RV 5′-GTCCAAAAGGCATCAGGGTA-3′, DNMT1 FW: 5′-GGAGGAGGAAGCTGCTAAGG-3′and DNMT1 RV: 5′-TTGGTTTATAGGAGAGAT- TTATTTG-3′, the DNMT3A and 3B primers were previously reported.6 We also generated several inserts with deletions of 4 bp from the site of perfect complementarity of the DNMT3A, DNMT3B, and Sp1 gene using the QIAGEN XL-site directed Mutagenesis Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). K562 cells (5 × 106) were cotransfected using nucleoporation (Amaxa Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol (solution V, program T-016) using 5 μg of the firefly luciferase report vector and 0.5 μg of the control vector containing Renilla luciferase, pRL-TK (Promega). For each nucleoporation, 50 nM of the pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide was used. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured consecutively using the dual luciferase assays (Promega) 24 hours after transfection.

EMSAs

Complementary oligonucleotides derived from the human DNMT1 promoter regions that contain putative Sp1-binding site were synthesized, annealed, and labeled with 32P-dCTP and Klenow. Nuclear extracts were isolated from K562 cells after transfection with pre-miR-29b or scrambled oligonucleotides using Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) with nuclear extracts and 32P-labeled DNMT1 promoter oligonucleotides were performed as previously described.14

GDM analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from AML cells using DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer's instructions. A liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method was used for determination of GDM as previously reported by our group.15

DNA methylation analysis of gene promoter regions

Quantitative DNA promoter methylation of ESR1 and p15 as well as the 5′ upstream flanking sequence from the pre-miR-29b-1 were performed using the EpiTYPER methylation analysis (Sequenom, San Diego, CA). DNA of scrambled or miR-29b nucleoporated MV4-11 cells was extracted 72 hours after transfection. A total of 1 μg of DNA was bisulfite treated, in vitro transcribed, and cleaved by RNase A, before being subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis for DNA methylation pattern determination as previously described.16 The following primers were used to amplify the regulatory regions of p15 and ESR1: p15 forward, 5′-AGGTTTGTAGGTTTATAGGTTTTT-3′; p15 reverse, 5′-TCTACTCTCTCTAACAAATCATAATAATAA-3′; ESR1 forward, 5′-GGGTAGAATTAGAGTAGTTTTGTGTT-3′; ESR1 reverse, 5′-AAAATTCTTTACTCCCAAAAATAAC-3′. A second method (pyrophosphate sequencing) was used to validate the ESR1 results as previously described.17 In brief, DNA obtained at 72 hours from MV4-11 cells transfected with miR-29b or scrambled oligonucleotides were bisulfite treated and PCR amplified (supplemental data, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). A biotin-labeled primer was used to purify the final PCR product using Sepharose beads. The PCR product was bound to Streptavidin Sepharose High Performance (GE Healthcare), and the Sepharose beads containing the immobilized PCR product were purified, washed, and denatured. Then, 0.3 amol/L of pyrosequencing primer was annealed to the purified single-stranded PCR product, and pyrosequencing was done using the PSQ HS96 Pyrosequencing System. These experiments were performed by an independent laboratory (Epigen, Cambridge, MA).17 The degree of methylation was expressed for each DNA locus as percentage of methylated cytosines over the sum of methylated and unmethylated cytosines.

Statistical analysis

Paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare methylation frequencies between the samples. All analyses were performed using SPSS statistics 17.0 software (Chicago, IL). P values are 2-sided.

Results

miR-29b down-regulates DNMT1, and DNMT3A and 3B in AML

To test the hypothesis that miR-29b down-regulates DNA methyltransferases in AML, we transfected pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide into K562 and MV4-11 AML cell lines and measured levels of DNMT1 and DNMT3A and 3B mRNAs and proteins by quantitative real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively. A third AML cell line, Kasumi-1, was infected with miR-29b lentivirus or empty vector because of low efficiency with the nucleoporation method in these cells. Basal miR-29b levels in these AML cell lines and miR-29b expression values after transfection/infection are reported in Figure S1.

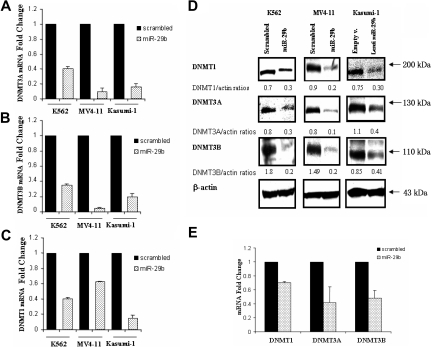

Transfection of the pre-miR-29b, but not the scrambled controls, resulted in a marked reduction of the endogenous mRNA levels of DNMT3A and 3B for all 3 cell lines (Figure 1A,B). The observed fold change reduction at 24 hours was 2.5, 11.1, and 6.1 for DNMT3A (Figure 1A) and 2.8, 17.7, and 4.9 for DNMT3B (Figure 1B) in pre-miR-29b–treated K562, MV4-11, and Kasumi-1 cells, respectively, compared with their respective controls. We also noted a reduction in the levels of DNMT1 in pre-miR-29b–treated K562, MV4-11, and Kasumi-1 cells (Figure 1C). This was a surprising finding as DNMT1 is not predicted to be a target for miR-29b. Consistent with these results, a significant down-regulation of endogenous DNMT1 and DNMT3A and 3B protein levels was also observed in all 3 AML cell lines 48 hours after pre-miR-29b transfection (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

miR-29b targets DNMT1, DNMT3A, and 3B in AML cell lines and primary AML blasts. (A) DNMT3A, (B) DNMT3B, and (C) DNMT1 mRNA expression after nucleoporation (K562, MV4-11) or infection (Kasumi-1) of pre-miR-29b or their respective controls (scrambled oligonucleotides for K562 and MV4-11cells and empty vector lentivirus for Kasumi-1 cells). Histograms show fold changes (reduction) in mRNA expression with respect to the controls after normalization with 18s in 3 independent experiments. Bars represent SD. (D) DNMT1, DNMT3A, and 3B protein expression after pre-miR-29b or control nucleoporation or infection in K562, MV4-11, and Kasumi-1 cell lines. Equivalent gel loading was confirmed by probing with antibodies against β-actin. (E) DNMT1 and DNMT3A and 3B mRNA expression in primary AML patient samples (n = 3) after nucleoporation of pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide. Histograms show fold changes (reduction) in mRNA expression with respect to the control after normalization with 18s. Bars represent SD.

Pre-miR-29b–mediated down-regulation was further validated in primary AML blasts. After 24 hours, there was a 1.4-, 2.3-, and 2.1-fold reduction in DNMT1 and DNMT3A and 3B mRNA levels in primary AML blasts transfected with pre-miR-29b compared with controls transfected with scrambled oligonucleotides(Figures 1E, S2).

DNMT3A and 3B are bona fide targets of miR-29b

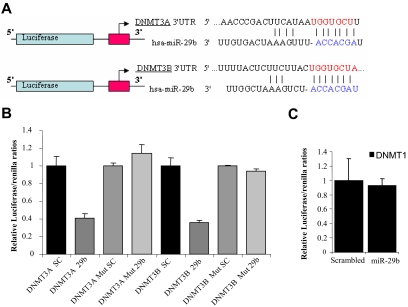

Available miRNA target prediction programs18,19 indicate that DNMT3A and 3B are putative targets of miR-29b (Figure 2A). We confirmed this finding in AML cells by performing luciferase reporter assays. DNMT3A and 3B complementary sites were cloned downstream of the firefly luciferase gene and cotransfected with pre-miR-29b or scrambled oligonucleotide. Luciferase activity was measured after 24 hours of transfection. Cells cotransfected with either DNMT3A or 3B reporter and pre-miR-29b exhibited approximately 60% reduction of the luciferase activity with respect to those cotransfected with the scrambled oligonucleotide (Figure 2B). We further deleted 4 nucleotides (GGUG) from each miR-29b–predicted site and cotransfected the mutated constructs along with pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide in K562 cells. As shown in Figure 2B, the deletion of miR-29b interaction sites abrogated the miR-29b/DNMT3A and miR-29b/DNMT3B interaction evidenced by no change in the normalized luciferase activity.

Figure 2.

DNMT3A and 3B are targets of miR-29b. (A) Schema of the 2 firefly luciferase reporter constructs for DNMT3A and 3B, indicating the interaction sites between miR-29b and the 3′ UTRs of the DNMT3s. (B) Dual luciferase assay of K562 cells cotransfected with firefly luciferase constructs containing the DNMT3A or 3B wild-type or mutated 3′ UTRs and pre-miR-29b or scrambled oligonucleotides as indicated. The firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. The data are shown as relative luciferase activity of pre-miR-29b transfected cells with respect to the control (scrambled oligonucleotide) of a total of 9 experiments from 3 independent transfections. Bars represent SD. (C) Dual luciferase assay of K562 cells cotransfected with firefly luciferase constructs containing the DNMT1 3′ UTR and pre-miR-29b or scrambled oligonucleotides. The data are shown as relative luciferase activity of pre-miR-29b–transfected cells with respect to the control (scrambled oligonucleotide) of 9 experiments obtained from 3 independent transfections. Bars represent SD.

miR-29b down-regulates indirectly DNMT1 by targeting its regulator Sp1

In contrast to DNMT3A and 3B, miR-29b is not predicted to hybridize with the DNMT1 3′ UTR region and therefore directly target this gene.18,19 To further prove that DNMT1 is not a direct target of miR-29b, we cloned the DNMT1 3′ UTR into a luciferase reporter vector and cotransfected with pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide into K562 cell lines, as done for DNMT3A and 3B. Consistent with the notion that DNMT1 is not a direct target of miR-29b, no difference in the luciferase activity was noted between cells treated with scrambled or pre-miR-29b oligonucleotides (Figure 2C). Therefore, we reasoned that miR-29b probably down-regulated DNMT1 indirectly.

Recent work suggests that Sp1, a zinc finger transcription factor, binds directly to the promoter of DNMT1 and positively regulates the transcription of this gene in mice and humans.14,20 Here, we further confirm the Sp1-DNMT1 link by showing that Sp1-siRNA treatment of K562 cells results in down-regulation of Sp1 and in turn DNMT1 mRNA and protein levels as measured by quantitative RT-CR and Western blotting (Figure S3A,B). DNMT1 down-regulation results in a GDM reduction of 40% with respect to the control (Figure S3C) and estrogen receptor 1 alpha (ESR1) gene reexpression (1.3-fold increase in Sp1-siRNA compared with controls; Figure S3D).

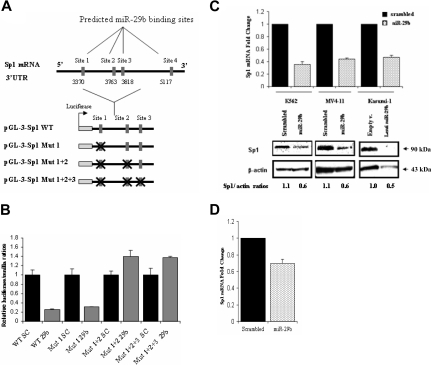

Interestingly, the 3′ UTR of Sp1 contains 4 predicted binding sites (at nucleotides 3370, 3763, 3818, and 5117) for miR-29b according to Pictar 200518 and 2 predicted binding sites (at nucleotides 3370 and 3818) according to Targetscan 4.219 (Figure 3A). Therefore, we hypothesized that miR-29b down-regulates Sp1 expression, which in turn inhibits DNMT1 transactivation, thereby resulting in a decrease of DNMT1 at both mRNA and protein levels. To validate this hypothesis, we cloned the 3′ UTR region of Sp1 that encompasses 3 of the 4 miR-29b binding sites (sites 3370, 3763, and 3818) predicted by Pictar into a luciferase reporter vector and cotransfected it with pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide in K562 cells. The transfection with pre-miR-29b, but not with the scrambled oligonucleotide, decreased the luciferase activity of the gene reporter by at least 50% in 3 independent experiments (Figure 3B). We further deleted 4 nucleotides from each miR-29b predicted site and cotransfected the mutated constructs along with pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide in K562 cells. Concurrent mutations of sites 1 and 2 (ie, 3370 and 3763) or sites 1, 2, and 3 (ie, 3370, 3763, and3818) predicted miR-29b binding sites abrogated the miR-29b/Sp1 interaction evidenced by no change in the normalized luciferase activity. Mutations of only site 1 (ie, 3370) did not suffice in preventing this interaction (Figure 3B). Furthermore, ectopic expression of pre-miR-29b in AML cell lines and in primary AML blasts induced down-regulation of endogenous Sp1 mRNA and protein compared with scrambled oligonucleotides (Figure 3C,D).

Figure 3.

miR-29b targets Sp1. (A) Genomic representation of the Sp1 3′ UTR with the localization of the 4 predicted pre-miR-29b binding sites. Immediately below there is a schema of the luciferase reporter assays used in the luciferase experiments. The “X” sign over the red boxes indicates the miR-29b sites that were deleted. mut indicates mutated. (B) Dual luciferase assay of K562 cells cotransfected with firefly luciferase constructs containing the wild-type or mutants target site of the Sp1 3′ UTR region with pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide. The data are shown as relative luciferase activity of pre-miR-29b-transfected cells with respect to the control (scrambled oligonucleotide) of 9 experiments from 3 independent transfections. Bars represent SD. (C) Sp1 mRNA and protein expression after nucleoporation (K562, MV4-11) or infection (Kasumi-1) of pre-miR-29b or their respective controls, scrambled oligonucleotide, or empty vector lentivirus. Histograms show fold changes with SD. (D) Sp1 mRNA expression in 3 primary AML samples after nucleoporation of pre-miR-29b or scrambled oligonucleotide. Histograms show fold change (reduction) with respect to control after normalization with 18s. Bars represent SD.

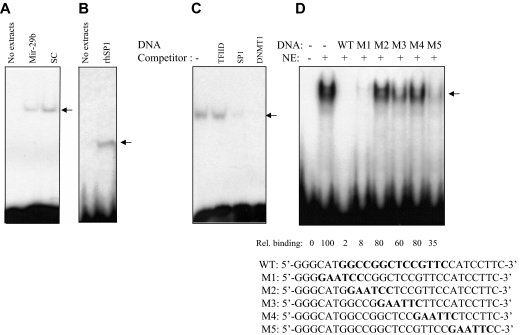

Finally, we performed EMSAs with nuclear extracts from K562 cells untransfected or transfected with pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide. We used a probe derived from the spanning DNMT1 promoter that contains an Sp1-binding site (Figure 4). We observed that Sp1 protein was present on DNMT1 gene promoter in untreated or scrambled oligonucleotide-treated controls whereas enforced expression of pre-miR-29b disrupted the association of Sp1 with the DNMT1 promoter. These results further support a mechanistic link between miR-29b–mediated down-regulation of Sp1 and decrease in DNMT1 expression.

Figure 4.

DNMT1 promoter activity was down-regulated by pre-miR-29b through repression of Sp1. (A) EMSA of DNMT1 promoter DNA and nuclear extracts prepared from K562 cells transfected with miR-29b construct (miR-29b) or scrambled control (sc). The arrow represents the DNMT1-protein complex. (B) EMSA of DNMT1 promoter DNA with human recombinant Sp1 protein (0.5 mg, rhSp1, Promega, catalog no. E6391) or no protein extracts. These data further indicate that Sp1 is binding to the DNMT1 promoter DNA. (C) EMSA of DNMT1 promoter DNA using K562 nuclear extracts with unlabeled DNA competitors (Sp1-binding elements and DNMT1 promoter DNA, WT). As a control, we used no DNA competitor (−) and a nonspecific unlabeled probe (TFIID) that contains the TATA box sequence 5′-GCAGAGCATATAAGGTGAGGTAGG A-3′. This sequence is not related to the DNMT1 promoter DNA. The fact that this oligo did not compete shows specificity of DNA competition by DNMT1 DNA and by SP1 DNA. (D) EMSA of DNMT1 promoter DNA using K562 nuclear extracts and unlabeled wild-type (WT) or mutants (M) excess (20 times) DNA competitors. The first 2 lanes (from the left) are without competitors. The sequences of the DNMT1 promoter DNA and various DNMT1 mutants with linker scanned mutations (shown in bold-type) are shown below (M1-M5).

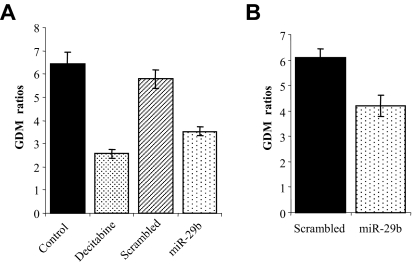

Overexpression of pre-miR-29b reduces global DNA methylation

Next we investigated whether the enforced expression of pre-miR-29b could also functionally result in DNA hypomethylation. GDM was measured using an LC-MS/MS method15 in MV4-11 and Kasumi-1 cells lines after 72 hours of transfection or infection, respectively, with pre-miR-29b oligonucleotide or a lentivirus expressing miR-29b. Scrambled oligonucleotides and empty lentivirus vectors served as negative controls for MV4-11 and Kasumi-1, respectively. We observed a reduction of approximately 30% in GDM for the AML cells lines treated with pre-miR-29b oligonucleotide or miR-29b lentivirus compared with the negative controls (Figure 5A,B). The reduction in GDM in MV4-11 cells by pre-miR-29b was comparable with that achieved with decitabine treatment at the same time point (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Overexpression of pre-miR-29b in AML cell lines reduces GDM. MV4-11 (A) and Kasumi-1 (B) cell lines were nucleoporated (MV4-11) or infected (Kasumi-1) with pre-miR-29b (oligonucleotides and lentivirus) or their respective controls. DNA was obtained from both cell lines after 72 hours of nucleoporation or infection, and GDM was measured by LC-MS/MS.14 Results from treatment with 2.5 μM decitabine, a hypomethylating agent, or phosphate-buffered saline (control) are also shown for the MV4-11 cell line as positive controls. The data are shown as absolute GDM. Bars represent range of 2 independent experiments.

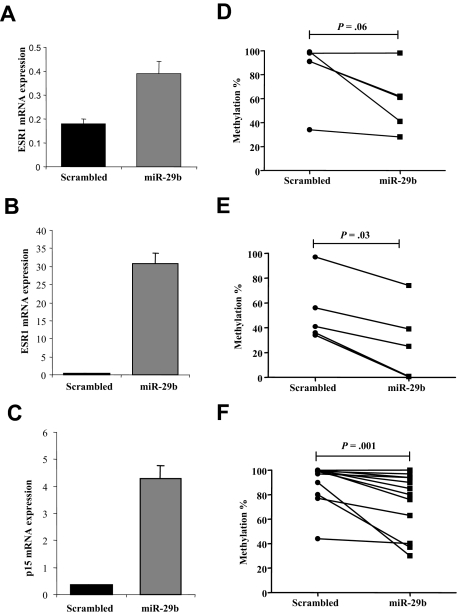

Overexpression of pre-miR-29b restores the expression of the hypermethylated ESR1 and p15 INK4b in AML via promoter DNA hypomethylation

Several genes have been found methylated, silenced, and reexpressed after treatment with hypomethylating agents in AML, including ESR121 and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B (p15 INK4b).22 To assess whether overexpression of miR-29b could also lead to reexpression of hypermethylated and silenced genes in AML, we measured the mRNA levels of ESR1 and p15INK4b by quantitative RT-PCR in the MV4-11 cell line and ESR1 for the K562 cell line after transfection with pre-miR-29b or a scrambled oligonucleotide. The reason we did not measure p15INK4b in K562 is because this gene is homozygously deleted in this cell line.23 Transfection with pre-miR-29b induced ESR1 expression by 86.1-fold in MV4-11 and 2.1-fold in K562 cells compared with the control after 72 hours (Figure 6A,B). Likewise, transfection with pre-miR-29b induced p15INK4b by 11.6-fold compared with the control after 72 hours (Figure 6C). Furthermore, using a quantitative approach,16 we showed that, after transfection of pre-miR-29b oligonucleotides, reexpression of ESR1 and p15INK4b coincided with reduction in the DNA methylation levels of both genes. The ESR1 DNA methylation level was decreased in K562 cells transfected with pre-miR-29b compared with those transfected with scrambled oligonucleotides (mean, 58% vs 82%; P = .06, paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Figure 6D). Although this difference was not statistically significant, there was a trend toward significance. In the same vein, the ESR1 DNA methylation level was significantly decreased in MV4-11 cells transfected with pre-miR-29b compared with those transfected with scrambled oligonucleotides (mean, 26% vs 49%; P = .03, paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Figures 6E, S4A). The p15INK4b DNA methylation levels were significantly decreased in MV4-11 cells transfected with pre-miR-29b compared with those transfected with scrambled oligonucleotides (mean, 75% vs 91%; P = .001, Paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Figures 6D, S4B). Using an alternate method (pyrophosphate sequencing), we confirmed that ESR1 DNA methylation level was significantly decreased in pre-miR-29b MV4-11 transfected cells compared with the scrambled oligonucleotides (mean, 76% vs 62%; P = .04, paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Figure S4C,D).

Figure 6.

Pre-miR-29b restores expression of hypermethylated ESR1 and p15INK4b in the MV4-11 cell line. (A) Quan-titative RT-PCR for ESR1 in K562 and MV4-11 cells (B), and p15INK4b (C) after 72 hours of nucleoporation with pre-miR-29b or scrambled oligonucleotides. Histograms represent mean values with SD. (D) Scatter plots of the quantitative DNA methylation data of ESR1 promoter regions in K562 (D) and MV4-11 cells (E) after nucleoporation with pre-miR-29b (■) or a scrambled oligonucleotide (●) obtained using the MassArray system.15 The lines connecting the dots indicate the corresponding CpG pairs. (F) Scatter plots of the quantitative DNA methylation data of p15INK4b in MV4-11 cells after nucleoporation with pre-miR-29b (■) or a scrambled oligonucleotide (●). Each dot represents a single CpG or a group of CpGs analyzed. The lines connecting the dots indicate the corresponding CpG pairs. The scatter plots were created using GraphPad Prism, version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The P values were obtained comparing the CpG methylation levels between scrambled and pre–miR-29b–transfected cells using paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Error bars indicate SD.

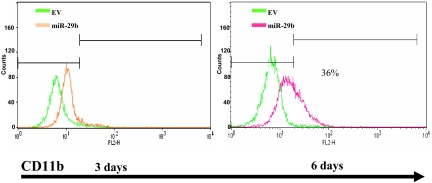

Overexpression of pre-miR-29b induces partial differentiation of AML blasts

To assess the biologic effects of overexpressing miR-29b in AML blasts, we infected Kasumi-1 cells with miR-29b lentivirus or empty vector and measured CD11b expression by FACS. As shown in Figure 7, Kasumi-1 cells infected with miR-29b exhibited higher levels of CD11b expression compared with the empty vector at 6 days (38% increase in CD11b expression in miR-29b lentivirus compared with empty vector).

Figure 7.

Overexpression of pre-miR-29b induces partial differentiation of AML blasts. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of CD11b expression in Kasumi-1 cells infected with lentivirus-expressing miR-29b or empty vector. Green represents empty vector (EV); red, miR-29b lentivirus.

Discussion

In the current study, we characterized the role of miR-29b in the regulation of DNA methylation in AML. Our data showed that miR-29b targets DNMTs, thereby resulting in global DNA hypomethylation and reexpression of hypermethylated, silenced genes in AML. The current results are consistent with our previous work in lung cancer with regard to the targeting activity of miR-29b on DNMT3A and 3B and expand the epigenetic regulatory role of this miRNA to myeloid malignancies.6 We also showed that miR-29b down-regulates DNMT1 by targeting Sp1, which is a zinc finger transcription factor that regulates a large numbers of genes involved in the cell cycle, proliferation, apoptosis, and malignant transformation.24 It has been shown that Sp1 binds to the promoter of DNMT1 and transactivates the DNMT1 gene in the mouse.20 Our group recently reported that the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib induces DNA hypomethylation by interfering with the NF-κB/Sp1-dependent transcription of DNMT1 in AML cell lines and patients' primary blasts.14 Here we showed that miR-29b down-regulates Sp1, thereby interfering with the Sp1-dependent transcription of DNMT1.

The discovery that miR-29b down-regulates not only DNMT3A and 3B but also DNMT1 has important functional ramifications because it has been reported that selective genetic disruption of DNMT3B in colon cancer cell lines reduced GDM only by 3%. However, genetic disruption of both DNMT1 and DNMT3B completely abolished DNA methyltransferase activity and reduced GDM by 95%.25 Consistent with these results, we now show that miR-29b can efficiently modulate DNA hypomethylation because of its targeting of both DNMT3s and DNMT1.

To our knowledge, this is also the first report showing that overexpression of miR-29b results functionally in global DNA hypomethylation and gene reexpression of the hypermethylated and silenced p15INK4b and ESR1 in AML cell lines. Elegant studies in mice support a tumor suppressor role of p15INK4b in AML as p15INK4b-deficient mice are more susceptible to develop myeloid leukemia.26 The ESR1 gene is also frequently silenced by methylation in AML,22 and we previously showed that reexpression of these genes correlates with clinical response in patients treated with the hypomethylating agent decitabine.27 In the current study, reexpression of both p15INK4b and ESR1, induced by pre-miR-29b, coincided with significant DNA hypomethylation of the promoter regions of these genes, thereby validating the hypomethylation activity of miR-29b.

In this work, we also provide insights about the biologic effects of overexpressing miR-29b in AML. Restoring miR-29b expression in Kasumi-1 cells induces partial granulocytic differentiation. Similar differentiation effects have been shown in AML cell lines treated with hypomethylating agents.28 It has been shown that miR-29b induces apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cells by targeting MCL-1.29 We recently confirmed this finding in AML.30 The ectopic expression of miR-29b in AML cells induces apoptosis by targeting MCL-1.30 Therefore, restoring miR-29b expression in AML blasts induces partial differentiation and apoptosis.

We also think that these findings have potentially relevant therapeutic implications. Targeting DNMT1 with decitabine or azacitidine in AML cell lines and patients only partially reduces hypermethylation despite compelling inhibition of DNMT1,15 suggesting an underlying activity of other DNMT isoforms that are not efficiently inhibited by these agents. Therefore, one could envision that combining DNMT1 inhibitors (decitabine or azacitidine) with synthetic miR-29b oligonucleotides may result in a synergistic hypomethylating effect, more robust gene reexpression, and in turn better disease response in AML.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Donna Bucci from the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Leukemia Tissue bank for assistance in primary AML sample preparation.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant R01-CA102031, G.M.; grants P01-CA76259 and P01-CA81534, C.M.C.) and a Lauri Strauss Discovery Grant and Kimmel translational award (R.G.).

Footnotes

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: R.G., S.L., M.F., Z.L., C.E.A.H., E.C., S.S., J.P., J.Y., V.H., L.J.R., and L.-C.W. performed research; R.G., S.L., Z.L., S.V., W.B., K.C., M.A., N.M., L.J.R., D.P., C.D.B., J.C.B., C.M.C., and G.M. analyzed data; and R.G., S.L., and G.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.M.C. has applied for a patent on clinical use of miR-29 family in cancer. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Guido Marcucci, Ohio State University, BRT Bldg, Rm 898, 460 12th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210; e-mail: Guido.Marcucci@osumc.edu.

References

- 1.Galm O, Herman JG, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetics in hematopoietic malignancies. Blood Rev. 2006;20:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toyota M, Kopecky KJ, Toyota MO, Jair KW, Willman CL, Issa JP. Methylation profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:2823–2829. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizuno S, Chijiwa T, Okamura T, et al. Expression of DNA methyltransferases DNMT1, 3A, and 3B in normal hematopoiesis and in acute and chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:1172–1179. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito Y, Liang G, Egger T, et al. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabbri M, Garzon R, Cimmino A, et al. MicroRNA-29 family reverts aberrant methylation in lung cancer by targeting DNA methyltransferases 3A and 3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15805–15810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707628104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garzon R, Fabbri M, Cimmino A, Calin GA, Croce C. MicroRNA expression and function in cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calin GA, Dumitru DC, Shimitzu M, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro-RNA genes miR-15 and miR-16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calin GA, Ferracin M, Cimmino A, et al. A microRNA signature associated with prognosis and progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1793–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raveche ES, Salerno E, Scaglione BJ, et al. Abnormal microRNA-16 locus with synteny to human 13q14 linked to CLL in NZB mice. Blood. 2007;109:5079–5086. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-071225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garzon R, Volinia S, Liu CG, et al. MicroRNA signatures associated with cytogenetics and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:3183–3189. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-098749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C (T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S, Liu Z, Xie Z, et al. Bortezomib induces DNA hypomethylation and silenced gene transcription by interfering with Sp1/NF-κB-dependent DNA methyltransferase activity in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:2364–2373. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Z, Liu S, Xie Z, et al. Characterization of in vitro and in vivo hypomethylating effects of decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia by a rapid, specific and sensitive LC-MS/MS method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehrich M, Nelson MR, Stanssens P, et al. Quantitative high-throughput analysis of DNA methylation patterns by base-specific cleavage and mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15785–15790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507816102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasquali L, Bedeir A, Ringquist S, Styche A, Bhargava R, Trucco G. Quantification of CpG island methylation in progressive breast lesions from normal to invasive carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2007;257:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krek A, Grün D, Poy MN, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target prediction. Nat Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis B, Shih I, Jones-Rhoades M, Bartel D, Burge C. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kishikawa S, Murata T, Kimura H, Shiota K, Yokoyama KK. Regulation of transcription of the Dnmt1 gene by Sp1 and Sp3 zinc finger proteins. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:2961–2970. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Issa JP, Zehnbauer BA, Civin CI, et al. The estrogen receptor CpG island is methylated in most hematopoietic neoplasms. Cancer Res. 1996;56:973–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herman JG, Jen J, Merlo A, Baylin SB. Hypermethylation-associated inactivation indicates a tumor suppressor role for p15INK4B. Cancer Res. 1996;56:722–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakashita K, Koike K, Kinoshite T, et al. Dynamic DNA methylation change in the CpG island region of p15 during human myeloid development. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1195–1204. doi: 10.1172/JCI13030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black AR, Black JD, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Sp1 and krüppel-like factor family of transcription factors in cell growth regulation and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2001;188:143–160. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee I, Bachman KE, Park BH, et al. DNMT1 and DNMT3B cooperate to silence genes in human cancer cells. Nature. 2002;416:552–556. doi: 10.1038/416552a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolff L, Garin MT, Koller R, et al. Hypermethylation of the Ink4b locus in murine myeloid leukemia and increased susceptibility to leukemia in p15(Ink4b)-deficient mice. Oncogene. 2003;22:9265–9274. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blum B, Klisovic R, Liu S, et al. Phase I study of decitabine alone or in combination with valproic acid treatment in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3884–3891. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koschmieder S, Agrawal S, Radomska HS, et al. Decitabine and vitamin D3 differentially affect hematopoietic transcription factors to induce monocytic differentiation. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mott JL, Kobayashi S, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Mir-29 regulates Mcl-1 protein expression and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2007;26:6133–6140. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garzon R, Pichiorri F, Calin GA, et al. MicroRNA-29b targets MCL-1 and is down-regulated in chemotherapy-resistant acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [abstract]. Blood. 2007;110:717a. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.