Abstract

A tissue-specific transcriptional enhancer, Eμ, has been implicated in developmentally regulated recombination and transcription of the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene locus. We demonstrate that deleting 220 nucleotides that constitute the core Eμ results in partially active locus, characterized by reduced histone acetylation, chromatin remodeling, transcription, and recombination, whereas other hallmarks of tissue-specific locus activation, such as loss of H3K9 dimethylation or gain of H3K4 dimethylation, are less affected. These observations define Eμ-independent and Eμ-dependent phases of locus activation that reveal an unappreciated epigenetic hierarchy in tissue-specific gene expression.

Activation of a tissue-specific locus involves multiple epigenetic changes that are brought about by cis-regulatory sequences. However, the order or regulation of these changes is poorly understood for any mammalian gene. The β-globin gene cluster is one of the best characterized in terms of epigenetic regulation. In this locus, a region encompassing the four β-like genes is in a DNase I–sensitive configuration and associated with acetylated histones H3 and H4 in the erythroid lineage (1, 2). A cluster of DNase I hypersensitive sites (HS) comprise a locus control region that is essential for high-level transcription but not for erythroid-specific histone hyperacetylation or DNase I sensitivity (3–5). These observations provide evidence that transcription activation may be uncoupled from chromatin structural alterations that accompany locus activation.

The mouse Ig heavy chain (IgH) gene locus comprises variable (VH), diversity (DH), and joining (JH) gene segments and constant region exons that are dispersed over 2 Mb on chromosome 12. VH genes occupy ∼1.5 Mb and are separated by a gap of 100 kb from 8–12 DH gene segments (6). Most DH gene segments are part of a tandem repeat (7, 8), and the 3′-most segment, DQ52, is positioned less than 1 kb 5′ of the JH cluster. Functional IgH genes are assembled by site-specific recombination between VH, DH, and JH segments to create a V(D)J exon that encodes the antigen-binding variable domain of IgH. V(D)J recombination is developmentally regulated so that DH to JH recombination occurs first, followed by VH to DJH recombination.

Tissue specificity and developmental timing of V(D)J recombination has been conceptualized in terms of the accessibility hypothesis, which posits that recombinase access is restricted to the appropriate antigen-receptor locus depending on the cell type (9). Recent studies implicate histone acetylation as an epigenetic mark of accessible loci (9, 10). At the IgH locus, this is reflected in only the DH-Cμ region being associated with acetylated histones before initiation of rearrangements (11–14). VH genes are hyperacetylated at a later developmental stage coincident with the second rearrangement step (11, 15). Thus, the pattern of histone acetylation closely parallels developmental regulation of IgH gene rearrangements.

Locus accessibility is established by cis-regulatory sequences that were originally identified as transcriptional promoters and enhancers. The DH-Cμ region contains two tissue-specific DNase I HS in the germline configuration (11). One marks the intron enhancer Eμ (16) (Fig. 1) and the other marks a region 5′ to DQ52 that has promoter and enhancer activity (17). Genetic deletion of the DQ52 HS has little effect on IgH recombination (18, 19), whereas Eμ deletion reduces DH to JH recombination and blocks VH to DJH recombination (18, 20, 21). Although additional HSs have been identified in other parts of the IgH locus (22, 23), those that have been examined by genetic deletion appear not to contribute to V(D)J recombination.

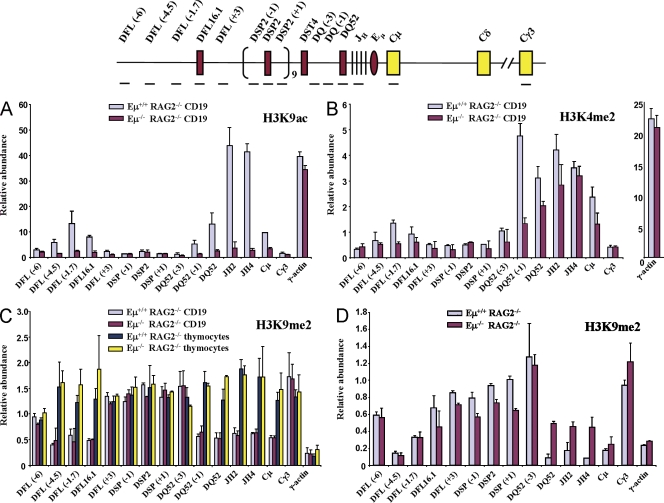

Figure 1.

Eμ-dependent histone modifications in the unrearranged IgH locus. (A and B) CD19+ bone marrow pro–B cells from RAG2− and Eμ−RAG2− mice were used in chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays using anti-H3K9ac (A) or anti-H3K4me2 (B) antibodies. A typical experiment used cells pooled from six to eight mice of each genotype. Positions of amplicons are indicated in the schematic on the top line; numbers in parentheses indicate position in kb 5′ (−) or 3′ (+) of the nearest DH gene segment. Amplicons from Cγ3 and γ-actin served as negative and positive controls, respectively. Results shown are from three independent cell preparations and immunoprecipitates analyzed in duplicates. Error bars represent standard deviation between experiments. (C and D) H3K9me2 was assayed by ChIP using primary pro–B and pro–T cells (C) or Abelson mouse leukemia virus–transformed pro–B cell lines from RAG2− and Eμ−RAG2− mice (D). Primary pro–B cells were CD19+ bone marrow cells from RAG2− or Eμ−RAG2− mice and primary pro–T cells were CD4−CD8− thymocytes obtained from the same animals. Anti-H3K9me2 antibody was used to coprecipitate genomic DNA from the four cell types followed by quantitative PCR and analysis as described for A and B. Cell lines were obtained by transforming bone marrow cells from mice of each genotype with Abelson virus. Immunoprecipitation and analysis was performed as described for primary cells. The error bars represent the standard deviation between three experiments.

Eμ transcriptional activity has been localized to a 700-bp region of the JH-Cμ intron, the bulk of which maps to a 220-bp “core” region that contains all the functionally characterized binding sites for transcription factors (16). The core is flanked by matrix attachment regions, whose deletion does not affect IgH gene recombination (21).

As a step toward understanding how Eμ regulates IgH locus activation, we analyzed the effects of deleting the Eμ core on IgH chromatin structure, transcription, and recombination. For simplicity, we shall refer to this core deletion as Eμ deletion throughout this paper. Of the several histone modifications that characterize a fully active locus, we found that a subset were affected by Eμ, whereas others, such as H3K9 demethylation or H3K4 methylation, were not. Eμ deletion also resulted in reduced transcription and transcription-associated histone modifications, as well as loss of the DQ52 HS. We suggest that Eμ− alleles are trapped in a partially activated state that has not been previously described for any mammalian gene. Based on these observations, we propose that a hierarchy of epigenetic changes activate the IgH locus.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Contribution of Eμ to histone modifications

We used core Eμ-deleted mice bred to a recombination activation gene (RAG) 2–deficient background (20) to study the chromatin and transcription state of the IgH locus just before initiation of recombination. We used chromatin immunoprecipitation to assay histone modification changes in the absence of Eμ. In primary B cell precursors that contain unrearranged IgH loci (pro–B cells), H3K9 acetylation (H3K9ac), a mark of gene activation, was severely reduced throughout the DH-Cμ domain on Eμ− alleles compared with Eμ+ alleles (Fig. 1 A). This included particularly high levels of H3K9ac at the JH gene segments and the peak located close to DFL16.1, which is more than 50 kb 5′ of Eμ. Because the H3K9ac pattern in an Abelson virus–transformed pro–B cell line from Eμ−/RAG2− mice (Fig. S1 A) was indistinguishable from that seen in primary cells, we extended the analysis to H4 acetylation (H4ac) in this cell line. H4ac levels were also substantially reduced in the absence of Eμ (Fig. S1 B). In contrast, a third activation-specific modification, dimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me2), was considerably less affected on Eμ− alleles from bone marrow–derived pro–B cells (Fig. 1 B). We conclude that Eμ controls only a subset of tissue-specific positive histone modifications that mark the unrearranged IgH locus.

Dimethylation of lysine 9 of histone H3 (H3K9me2) is a mark of inactive chromatin. In pro–T cells, or nonlymphoid lineage cells, H3K9me2 is present throughout the IgH locus. In pro–B cells, H3K9me2 is replaced by H3K9ac in all parts of the DH-Cμ region except the intervening DSP2 gene segments (7). We therefore investigated whether Eμ− alleles reverted to H3K9me2 modification in the absence of H3K9ac. The pattern of H3K9me2 was indistinguishable between Eμ+ or Eμ− pro–B cells (Fig. 1 C), revealing a discordance in the inverse relationship between H3K9ac and H3K9me2. We infer that loss of H3K9me2 is Eμ independent and gain of H3K9ac is Eμ dependent in primary pro–B cells. These observations indicate that Eμ− alleles are in a partially activated state.

This idea was further corroborated by analysis of suppressive histone modifications in pro–B cell lines. We found that DQ52, JH2, and JH4 amplicons that were associated with particularly high H3K9ac in Eμ+ cells contained 2–3-fold higher levels of H3K9me2 in Eμ− cells (Fig. 1 D). We note, however, that the locus was not restored to the fully repressed state seen in pro–T cells (Fig. 1 C) or to the level of H3K9me2 at the adjacent DSP2 repeats in Eμ+ pro–B cells. Dimethylation of lysine 27 of H3 (H3K27me2), another negative regulatory mark which has been proposed to be most evident in dividing cells (24), was also greatly elevated in the DQ52-Cμ region on Eμ− alleles (Fig. S2). These observations emphasize the state of the Eμ-deleted locus as a transitional intermediate between a fully “open” and a fully “closed” configuration.

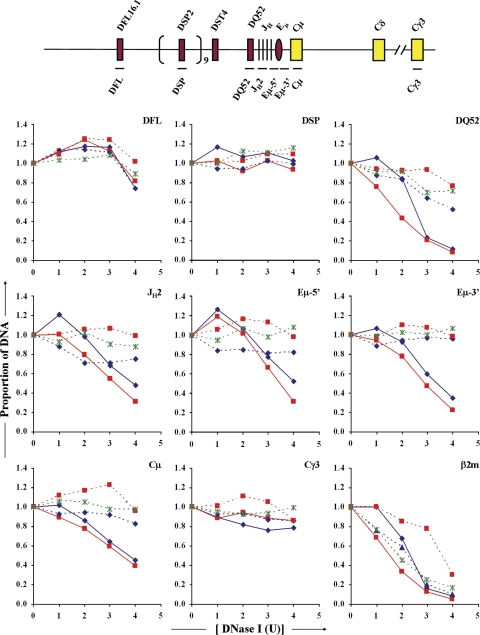

Contribution of Eμ to DNase I sensitivity

We further investigated the effects of Eμ deletion using a PCR-based DNase I sensitivity assay to probe Eμ+ and Eμ− alleles in pro–B cell lines. To compare between samples, signals from IgH locus amplicons were normalized to an amplicon from the β-globin gene (25). Amplicons just 5′ or 3′ to the Eμ core were rapidly degraded in Eμ+ cells (Fig. 2, solid lines), which is indicative of the Eμ DNase I HS. Both amplicons were relatively insensitive in Eμ− cells (Fig. 2, dashed lines), indicating that Eμ core deletion abrogated the HS (Fig. 2, Eμ-5′ and Eμ-3′). Classical DNase I hypersensitive site mapping by Southern blots confirmed this conclusion (unpublished data). Notably, DQ52 hypersensitivity was also substantially reduced in Eμ− cells, suggesting that it was Eμ dependent. Loss of Eμ also reduced DNase I sensitivity within JH gene segments and at Cμ but not at DFL16.1. The H3K9me2-bearing DSP genes remained DNase I insensitive in Eμ+ or Eμ− cells. We conclude that Eμ controls local chromatin accessibility and is critical for generation of the DQ52 HS.

Figure 2.

DNase I sensitivity analysis of Eμ+ and Eμ− IgH alleles. Nuclei from Abelson virus–transformed cell lines of the genotypes indicated below were treated with increasing concentrations of DNase I (x axis, DNase I U) followed by purification of genomic DNA. Primer pairs from the DH-Cμ region (shown in the schematic on the top line), the Cγ3 region, the β-globin, and β2-microglobulin (β2m) loci were used in quantitative PCR amplification of equal amounts of genomic DNA. The proportion of DNA for each amplicon (y axis) at each DNase I concentration was normalized to the level of β-globin amplicon at that DNase I concentration, as described in Materials and methods. The resulting value at 0 U DNase I is assigned the value 1 on the y axis. In this method of analysis, the value for the inactive β-globin gene remains at 1 through all concentrations of DNase I used (not depicted). Increased DNase I sensitivity is reflected in loss of signal with increasing DNase I digestion. To score for the Eμ hypersensitive site, we used primer sets located just 5′ (Eμ-5′) and 3′ (Eμ-3′) to the core region that is deleted in Eμ− alleles. Results are shown for three independent DNase I digestion experiments with Eμ−RAG2− cells (dashed lines) and two independent preparations from Eμ+RAG2− cells (solid lines). Each amplicon was analyzed in duplicate and each experiment is denoted by a different color.

Because the DQ52 HS is Eμ dependent, Eμ-deleted alleles lack both known DNase I HSs in the germline DH-Cμ region. The partially activated state of the locus that we observed may be the result of cryptic transcription factor binding sites that are revealed in the absence of Eμ. A more interesting implication is that initial locus opening (scored as H3K9 demethylation and H3K4 methylation) is mediated by cis sequences that are not marked by DNase I HS. Codependence of DNase I HS has been previously explored in the β-globin locus control region. In the mouse locus, loss of one HS does not affect formation of the others (3, 26); that is, these sites are generated independently. In contrast, deletion of individual HSs in BAC transgenics that carry the human locus substantially reduces the formation of other HSs (27). Loss of DQ52 HS on Eμ-deleted alleles resembles the latter observation in a germline rather than transgenic context.

Contribution of Eμ to sterile transcription

We used quantitative RT-PCR with primers as indicated (Fig. 3, top line) to assay transcription in the absence of Eμ. Consistent with earlier results (18, 20), Cμ-encompassing transcripts were reduced ∼7–10-fold in Eμ-deficient primary pro–B cells. Additionally, sense-oriented transcripts, as assayed by the DQ52 amplicon, as well as all antisense transcripts assayed by all other DH-amplicons (7, 8), were reduced 10–50-fold in Eμ− pro–B cells (Fig. 3 A). Reduced transcript levels coincided with reduced RNA polymerase II density on Eμ− alleles in pro–B cell lines (Fig. 3 B). We conclude that one function of Eμ is to recruit RNA Pol II to the IgH locus.

Figure 3.

Eμ-dependent transcription and transcription-associated histone modifications in the unrearranged IgH locus. Total RNA obtained from bone marrow pro–B cells of the indicated genotypes were converted to complementary DNA using random hexamers and reverse transcription, followed by quantitative PCR using primers from the DH-Cμ region (A) or VH region (D). Amplicon locations are indicated in the schematics that accompany each figure. The numbers in D represent the approximate distance in kilobase between neighboring amplicons. For comparing between genotypes, the data with each primer pair was normalized to the expression level of γ-actin; the DFL16.1 amplicon from A is included in D to provide an indication of transcript levels across the entire IgH locus (note that y axis scales differ between A and D). The data shown is the mean of two independent RNA preparations from each genotype analyzed in duplicates with each primer set. The error bars represent the standard deviation between experiments. Anti-RNA polymerase II (B) and anti-H3K4me3 (C) antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate chromatin from Abelson virus–transformed cell lines (B) or primary pro–B cells (C) of the indicated genotypes. Results shown are from three independent chromatin preparations that were analyzed in duplicate with each primer set. Error bars represent the standard deviation between experiments.

We also assayed the effect of Eμ deletion on transcription-associated histone modifications. H3K4me3 has been shown to be enriched at the 5′ ends and H3K36me3 at the 3′ ends of transcription units (28, 29). Eμ deletion reduced H3K4me3 levels to a third of that seen on Eμ+ alleles in primary pro–B cells (Fig. 3 C) and virtually eliminated both forms of modifications in the Eμ− pro–B cell line (Fig. S3). We infer that low-level transcription in primary cells may be sufficient to induce H3K4me3; alternatively, this mark may build up as a result of its slow removal by histone demethylases. A plant homeodomain (PHD) in RAG2, which selectively binds H3K4me3, was recently shown to be required for efficient V(D)J recombination (30, 31). Our observations provide the first evidence that low levels of H3K4me3 present in Eμ− primary pro–B cells may be sufficient to direct DH to JH recombination even in the absence of histone acetylation.

Because Eμ deletion affects VH to DJH recombination, we examined sterile VH gene transcription in Eμ+ and Eμ− primary pro–B cells. By quantitative RT-PCR, we found that sterile transcripts of proximal VH genes were substantially attenuated by loss of Eμ (Fig. 3 D); however, five amplicons representing upstream VHs were not significantly affected. For reference, VH7183.1b (also know as VH81X) is located ∼98 kb from DFL16.1 and Vox-1, a further 300 kb from VH7183.1b. VGK2, the most 3′ gene in our set which is not affected by Eμ deletion, lies 420 kb 5′ of Vox-1. We conclude that Eμ influences transcription of gene segments located >400 kb away.

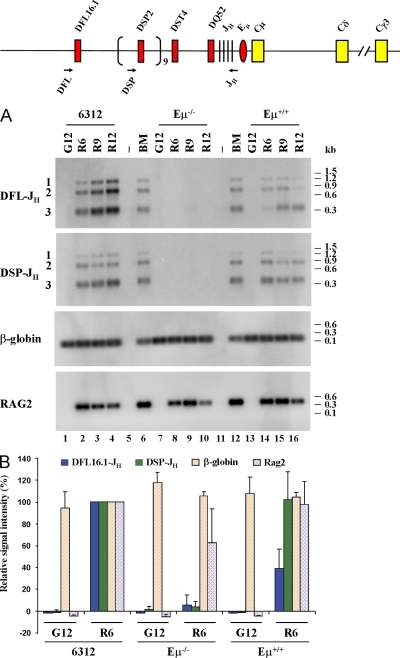

Effect of Eμ deletion on DH to JH recombination

Earlier studies show that Eμ deletion results in five- to eightfold lower levels of DH to JH recombination (18, 20). These numbers were obtained from analyses of steady-state cell populations that are potentially subject to selection in vivo. To get an independent measure of DH recombination efficiency, we expressed RAG2 in two Eμ+ and one Eμ− RAG2-deficient pro–B cell lines by retroviral gene transfer and followed the levels of DH recombination as a function of time. We amplified genomic DNA from infected cells with 5′ primers corresponding to either DFL16.1 or DSP gene segments and a common 3′ primer downstream of JH3 (Fig. 4, top line). The amplified fragments were detected by Southern blotting after agarose gel fractionation. We observed easily detectable levels of DFL16-JH and DSP-JH rearrangements over the experimental time course in both Eμ+ cell lines (Fig. 4 A, lanes 1–4 and 13–16) but not in the Eμ− cell line (Fig. 4 A, lanes 7–10). Transduced RAG2 gene levels were comparable between all three cell lines, and an amplicon from the β-globin locus was used to ensure equal loading of genomic DNA. The mean of three independent infections is quantitated in Fig. 4 B. We conclude that Eμ deletion severely impairs DH to JH recombination in this assay. The greater reduction of DH to JH recombination in cell lines compared with primary cells may be because the chromatin structure of the IgH locus in continuously cycling Eμ− cells is skewed toward a suppressive state. This is reflected in lower levels of activating modifications H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 and higher levels of inactivating modifications H3K9me2 and H3K27me2 in these cells compared with primary cells. Alternatively, DJH junctions seen in the bone marrow of Eμ-deficient mice represents a gradual accumulation of recombinant alleles.

Figure 4.

Analysis of DH to JH recombination in Eμ− cells. (A) Abelson virus–transformed Eμ+RAG2− cell lines (6312, lanes 1–4; Eμ+, lanes 13–16) and an Eμ−RAG2− cell line (lanes 7–10) were infected with control (G) or RAG2-expressing (R) retroviruses. Genomic DNA prepared after 6, 9, and 12 d was used to analyze DFL16.1 and DSP2 rearrangements as described in Materials and methods. Location of DH-specific 5′ primers and the common 3′ primer are shown as arrows on the top line. The infection efficiency of the RAG2 virus was 10–15% in 6312 cells as determined by GFP fluorescence. This number could not be determined for Eμ+ or Eμ− cells because all cells were GFP+ before infection. The level of introduced RAG2 in each cell line was determined by PCR amplification of genomic DNA (labeled RAG2). Reactions in lanes 6 and 12 were performed with genomic DNA from total bone marrow cells from a C57BL/6 mouse, and those in lanes 5 and 11 were performed with water to serve as positive and negative control, respectively. An amplicon from the β-globin gene was used to ensure equal DNA usage from all samples. After PCR amplification, the products were fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis and the products assayed by Southern blotting. Data shown is representative of three independent infection experiments. (B) Signals from control retrovirus-infected day-12 (G12) samples and RAG2 retrovirus-infected day-6 (R6) samples from 6312, Eμ−RAG2−, and Eμ+RAG2− cell lines were quantitated by phosphorimager. Signal intensities from 6312 cells (6312 R6) were taken as 100% and compared with all other samples. Data shown is the mean of three independent infection of each cell line, analyzed in duplicate by PCR and Southern blotting. Error bars represent the standard deviation between experiments.

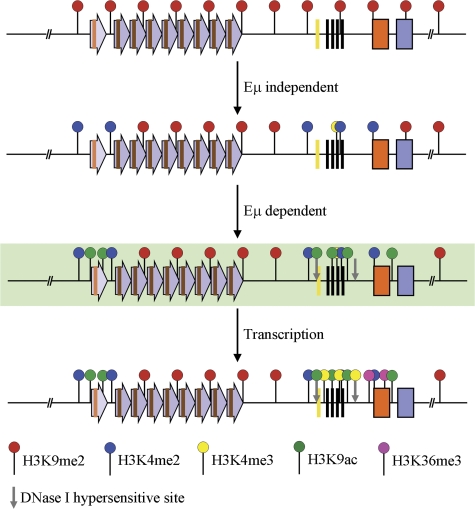

Our observations suggest an epigenetic hierarchy in the activation of the IgH locus. We propose that an Eμ-independent first step removes H3K9me2 and establishes the H3K4me2 mark (Fig. 5, line 2). This may permit transcription factors to access Eμ to convert a partially activated state to a fully activated one by Eμ-dependent induction of DNase I HS, histone acetylation, and transcription (Fig. 5 line 4). Though we cannot exclude the possibility that Eμ-independent and Eμ-dependent steps occur in parallel, we favor a sequential model based on studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae demonstrating that histone acetyl transferases are recruited to promoters that are premarked with H3K4me2 (32). The coordinate control of acetylation and transcription in the IgH locus is in line with genome-wide association studies (28, 33). Because histone acetylation likely precedes transcription (34), we suggest that Eμ binding proteins recruit RNA Pol II and chromatin-modifying enzymes to generate the optimal substrate for transcription (Fig. 5, line 3). Subsequently, transcription-associated histone modifications, such as H3K4me3, are incorporated into the locus (Fig. 5, line 4), which, in the case of antigen receptor genes, may be particularly important in targeting the V(D)J recombinase via the PHD domain in RAG2.

Figure 5.

Hierarchical model for epigenetic activation of the IgH locus. The DH-Cμ domain of the germline IgH locus in non–B lineage cells (top line). Purple arrows represent DSP- and DFL16.1-associated repeats; the gene segment is indicated as a brown line within the repeat. DQ52 and JH gene segments are shown as yellow and black vertical lines, respectively. Orange and blue boxes represent Cμ and Cδ exons, respectively. Red balloons identify the repressive H3K9me2 mark. Based on the analysis of core Eμ-deficient alleles, we propose that the first step of lineage-specific locus activation is Eμ independent and results in the configuration shown on line 2. Blue balloons represent H3K4me2, and low level of H3K4me3 is shown as a partial yellow balloon. This partially activated state allows Eμ binding proteins access to the IgH locus, leading to induction of DNase I HS at Eμ and DQ52 (gray vertical arrows, line 3). Eμ binding proteins also recruit histone acetyl transferases, which mark the locus with H3 and H4ac (green balloons, line 3) and RNA polymerase II. Induction of sterile transcription leads to transcription-associated histone modification (HeK4me3 and H3K36me3 marked as yellow and purple balloons, respectively) and a fully activated prerearrangement epigenetic state. Line 3 is shown in a background color to emphasize that this is an inferred intermediate that we have not experimentally characterized. All other lines summarize experimental data described in this paper obtained from pro–T cells (line 1), RAG2-deficient pro–B cells with Eμ-deficient alleles (line 2), and RAG2-deficient pro–B cells with wild-type IgH alleles (line 4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Abelson-transformed RAG2−/− and Eμ−/−RAG2−/− bone marrow–derived cell lines were cultured as previously described (7). CD19+ bone marrow cells were purified from RAG2−/− and Eμ−/−RAG2−/− mice were purified as previously described (11). Thymi from the same animals yielded CD4−CD8− thymocytes. All mouse experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of the National Institute on Aging (Harvard University and the Immune Disease Institute).

ChIPs.

ChIPs were performed as previously described (7). Formaldehyde–cross-linked and sonicated chromatin from 107 cells was precleared with 5 µg of nonspecific IgG and immunoprecipitated with the requisite antibody (sources noted in Table S1) or an equal amount of nonspecific IgG. The coprecipitated DNA was purified and analyzed by real-time PCR using either previously described primers (7) or primers shown in Table S2.

Real-time PCR and ChIP data analysis.

Real-time PCR was performed as previously described (7) using the ABI Prism 7000 (Applied Biosystems). Abundance of target sequences in the immunoprecipitate relative to the input DNA (IN) was determined as previously described (35), where the relative abundance of the target sequence in the immunoprecipitate is 2−[Ct(IP)−Ct(IN)], and Ct is the cycle at which the sample reached a threshold value where PCR amplification was exponential.

DNase I sensitivity.

20 × 106 nuclei from RAG2−/− and Eμ−/−RAG2−/− cells were treated with varying concentrations of DNase I. 25 ng of purified genomic DNA was used in quantitative PCR assays performed in duplicate with primer pairs shown in Table S2. The proportion of DNA for each amplicon was normalized to the amount of intact β-globin alleles at each DNase I concentration using the formula 2amp[Ct(0)−Ct(n)]/2β[Ct(0)−Ct(n)], where Ct(0) is the cycle number for non-DNase I–treated samples at which an amplicon reaches the threshold for exponential amplification and Ct(n) is the cycle number for the sample treated with n units of DNase I. In this analysis, signal strength for β-globin amplicon would be 1 at all concentrations of DNase I. Sensitivity at the IgH locus was determined using two to three independent DNase I–treated samples from cells of each genotype.

Lentiviral transduction.

Lentiviral particles expressing RAG2 were generated as previously described (31) by transiently transfecting 293T cells with pWPI-RAG2 along with helper plasmids pΔ8.2R and pVSVG using FuGENE 6 (Roche). The supernatant containing the virus was collected at 48 and 72 h after transfection and concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 2 h at 25,000 rpm and 20°C over a 20% sucrose cushion. 4–6 × 106 cells were infected with freshly prepared control or RAG2-expressing lentivirus by spin inoculation in the presence of 10 µg/ml polybrene. Genomic DNA was isolated from the infected cells at different days after infection using the DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN). All procedures involving lentiviruses were performed under BSL2 conditions.

DJ rearrangement in RAG2-transduced cells.

45 ng of genomic DNA from transduced cells or 9 ng of genomic DNA from C57BL/6 bone marrow was amplified by 33 rounds of PCR using the HotStarTaq polymerase (QIAGEN). The forward primers hybridized 5′ of either the DFL16.1 segment or the DSP2 segments and the reverse primer hybridized 3′ of JH3 (Table S2). 25% of the PCR reaction was resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, and rearrangement products were detected by Southern hybridization to an oligonucleotide probe that recognizes JH3. An amplicon from the mouse β-globin locus was used to normalize across samples, and level of RAG2 was ascertained using a primer pair that amplified part of the Rag2 gene not present in RAG2− cells (30 rounds of PCR amplification and 20% of the reaction used for Southern blotting).

Online supplemental material.

Supplemental figures show the effects of Eμ deletion on histone modifications assayed in Abelson mouse leukemia virus–transformed cell lines derived from the bone marrow of Eμ+ and Eμ− mice in a RAG2-deficient background. Table S1 lists the sources of antibodies and reagents used for ChIP and Table S2 lists primer sequences used in this work. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20081621/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sebastian Fugmann, Cosmas Giallourakis, Yu Nee Lee, and Lei Wang for discussion and comments on the manuscript and Valerie Martin for editorial assistance.

T. Perlot is supported by a Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds PhD scholarship. F.W. Alt is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI2047 (to F.W. Alt) and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (Baltimore, MD).

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- Bulger M., Sawado T., Schubeler D., Groudine M. 2002. ChIPs of the beta-globin locus: unraveling gene regulation within an active domain.Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12:170–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenfeld G., Burgess-Beusse B., Farrell C., Gaszner M., Ghirlando R., Huang S., Jin C., Litt M., Magdinier F., Mutskov V., et al. 2004. Chromatin boundaries and chromatin domains.Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 69:245–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender M.A., Bulger M., Close J., Groudine M. 2000. Beta-globin gene switching and DNase I sensitivity of the endogenous beta-globin locus in mice do not require the locus control region.Mol. Cell. 5:387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell C.M., Grinberg A., Huang S.P., Chen D., Pichel J.G., Westphal H., Felsenfeld G. 2000. A large upstream region is not necessary for gene expression or hypersensitive site formation at the mouse beta-globin locus.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:14554–14559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubeler D., Groudine M., Bender M.A. 2001. The murine beta-globin locus control region regulates the rate of transcription but not the hyperacetylation of histones at the active genes.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:11432–11437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevillard C., Ozaki J., Herring C.D., Riblet R. 2002. A three-megabase yeast artificial chromosome contig spanning the C57BL mouse Igh locus.J. Immunol. 168:5659–5666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty T., Chowdhury D., Keyes A., Jani A., Subrahmanyam R., Ivanova I., Sen R. 2007. Repeat organization and epigenetic regulation of the d(h)-cmu domain of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene locus.Mol. Cell. 27:842–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland D.J., Wood A.L., Afshar R., Featherstone K., Oltz E.M., Corcoran A.E. 2007. Antisense intergenic transcription precedes Igh D-to-J recombination and is controlled by the intronic enhancer Emu.Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:5523–5533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostoslavsky R., Alt F.W., Bassing C.H. 2003. Chromatin dynamics and locus accessibility in the immune system.Nat. Immunol. 4:603–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krangel M.S., McMurry M.T., Hernandez-Munain C., Zhong X.P., Carabana J. 2000. Accessibility control of T cell receptor gene rearrangement in developing thymocytes. The TCR alpha/delta locus.Immunol. Res. 22:127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury D., Sen R. 2001. Stepwise activation of the immunoglobulin mu heavy chain gene locus.EMBO J. 20:6394–6403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Angelin-Duclos C., Park S., Calame K.L. 2003. Changes in histone acetylation are associated with differences in accessibility of V(H) gene segments to V-DJ recombination during B-cell ontogeny and development.Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:2438–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes J., O’Neill L.P., Cavelier P., Turner B.M., Rougeon F., Goodhardt M. 2001. Chromatin remodeling at the Ig loci prior to V(D)J recombination.J. Immunol. 167:866–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morshead K.B., Ciccone D.N., Taverna S.D., Allis C.D., Oettinger M.A. 2003. Antigen receptor loci poised for V(D)J rearrangement are broadly associated with BRG1 and flanked by peaks of histone H3 dimethylated at lysine 4.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:11577–11582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Pflugh D.L., Yu D., Hesslein D.G., Lin K.I., Bothwell A.L., Thomas-Tikhonenko A., Schatz D.G., Calame K. 2004. B cell-specific loss of histone 3 lysine 9 methylation in the V(H) locus depends on Pax5.Nat. Immunol. 5:853–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolajczyk B.S., Dang W., Sen R. 1999. Mechanisms of mu enhancer regulation in B lymphocytes.Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 64:99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottmann A.H., Zevnik B., Welte M., Nielsen P.J., Kohler G. 1994. A second promoter and enhancer element within the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus.Eur. J. Immunol. 24:817–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afshar R., Pierce S., Bolland D.J., Corcoran A., Oltz E.M. 2006. Regulation of IgH gene assembly: role of the intronic enhancer and 5′DQ52 region in targeting DHJH recombination.J. Immunol. 176:2439–2447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke L., Kestler J., Tallone T., Pelkonen S., Pelkonen J. 2001. Deletion of the DQ52 element within the Ig heavy chain locus leads to a selective reduction in VDJ recombination and altered D gene usage.J. Immunol. 166:2540–2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlot T., Alt F.W., Bassing C.H., Suh H., Pinaud E. 2005. Elucidation of IgH intronic enhancer functions via germ-line deletion.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:14362–14367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai E., Bottaro A., Davidson L., Sleckman B.P., Alt F.W. 1999. Recombination and transcription of the endogenous Ig heavy chain locus is effected by the Ig heavy chain intronic enhancer core region in the absence of the matrix attachment regions.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:1526–1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khamlichi A.A., Pinaud E., Decourt C., Chauveau C., Cogne M. 2000. The 3′ IgH regulatory region: a complex structure in a search for a function.Adv. Immunol. 75:317–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlitzky I., Angeles C.V., Siegel A.M., Stanton M.L., Riblet R., Brodeur P.H. 2006. Identification of a candidate regulatory element within the 5′ flanking region of the mouse Igh locus defined by pro-B cell-specific hypersensitivity associated with binding of PU.1, Pax5, and E2A.J. Immunol. 176:6839–6851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter J., Sauer S., Peters A., John R., Williams R., Caparros M.L., Arney K., Otte A., Jenuwein T., Merkenschlager M., Fisher A.G. 2004. Histone hypomethylation is an indicator of epigenetic plasticity in quiescent lymphocytes.EMBO J. 23:4462–4472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur M., Gerum S., Stamatoyannopoulos G. 2001. Quantification of DNaseI-sensitivity by real-time PCR: quantitative analysis of DNaseI-hypersensitivity of the mouse beta-globin LCR.J. Mol. Biol. 313:27–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Bulger M., Bender M.A., Fields J., Groudine M., Fiering S. 2006. Deletion of the core region of 5′ HS2 of the mouse beta-globin locus control region reveals a distinct effect in comparison with human beta-globin transgenes.Blood. 107:821–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X., Xiang P., Yin W., Stamatoyannopoulos G., Li Q. 2007. Cooperativeness of the higher chromatin structure of the beta-globin locus revealed by the deletion mutations of DNase I hypersensitive site 3 of the LCR.J. Mol. Biol. 365:31–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokholok D.K., Harbison C.T., Levine S., Cole M., Hannett N.M., Lee T.I., Bell G.W., Walker K., Rolfe P.A., Herbolsheimer E., et al. 2005. Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast.Cell. 122:517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakoc C.R., Sachdeva M.M., Wang H., Blobel G.A. 2006. Profile of histone lysine methylation across transcribed mammalian chromatin.Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:9185–9195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews A.G., Kuo A.J., Ramon-Maiques S., Han S., Champagne K.S., Ivanov D., Gallardo M., Carney D., Cheung P., Ciccone D.N., et al. 2007. RAG2 PHD finger couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with V(D)J recombination.Nature. 450:1106–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Subrahmanyam R., Chakraborty T., Sen R., Desiderio S. 2007. A plant homeodomain in RAG-2 that binds hypermethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 is necessary for efficient antigen-receptor-gene rearrangement.Immunity. 27:561–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pray-Grant M.G., Daniel J.A., Schieltz D., Yates J.R., III, Grant P.A. 2005. Chd1 chromodomain links histone H3 methylation with SAGA- and SLIK-dependent acetylation.Nature. 433:434–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdistani S.K., Tavazoie S., Grunstein M. 2004. Mapping global histone acetylation patterns to gene expression.Cell. 117:721–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant M., Pugh B.F. 2006. Genome-wide relationships between TAF1 and histone acetyltransferases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:2791–2802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt M.D., Simpson M., Recillas-Targa F., Prioleau M., Felsenfeld G. 2001. Transitions in histone acetylation reveal boundaries of three separately regulated neighboring loci.EMBO J. 20:2224–2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]