Abstract

Candida albicans interacts with oral epithelial cells during oropharyngeal candidiasis and with vascular endothelial cells when it disseminates hematogenously. We set out to identify C. albicans genes that govern interactions with these host cells in vitro. The transcriptional response of C. albicans to the FaDu oral epithelial cell line and primary endothelial cells was determined by microarray analysis. Contact with epithelial cells caused a decrease in transcript levels of genes related to protein synthesis and adhesion, whereas contact with endothelial cells did not significantly influence any specific functional category of genes. Many genes whose transcripts were increased in response to either host cell had not been previously characterized. We constructed mutants with homozygous insertions in 22 of these uncharacterized genes to investigate their function during host-pathogen interaction. By this approach, we found that YCK2, VPS51, and UEC1 are required for C. albicans to cause normal damage to epithelial cells and resist antimicrobial peptides. YCK2 is also necessary for maintenance of cell polarity. VPS51 is necessary for normal vacuole formation, resistance to multiple stressors, and induction of maximal endothelial cell damage. UEC1 encodes a unique protein that is required for resistance to cell membrane stress. Therefore, some C. albicans genes whose transcripts are increased upon contact with epithelial or endothelial cells are required for the organism to damage these cells and withstand the stresses that it likely encounters during growth in the oropharynx and bloodstream.

Candida albicans is the most common cause of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection or AIDS, Sjogren's syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and head and neck cancers (52, 54, 55, 61, 74). This organism is also the most common cause of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis in neonates and in adult patients with central venous catheters, cancer, or recent surgery (3, 23, 51). The predominance of C. albicans in these infections suggests that this organism expresses unique virulence factors that enable it to cause disease in susceptible hosts.

Some aspects of the pathogenesis of oropharyngeal candidiasis and disseminated candidiasis are comparable. For example, during the development of oropharyngeal candidiasis, the organism adheres to and invades the epithelial cells of the oral mucosa (8, 14, 30, 31, 40, 69, 78). Similarly, during the initiation of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis, C. albicans adheres to and invades the endothelial cell lining of the blood vessels (19, 21, 49, 57). In addition, this organism invades both oral epithelial cells and endothelial cells in vitro by inducing its own endocytosis (14, 15, 19, 49, 57, 78). This endocytosis requires functional host cell microfilaments and is induced in part by Als3 on the fungal surface binding to E-cadherin on epithelial cells and N-cadherin on endothelial cells (19, 47, 49, 50, 57). Invasion of both cell types by live C. albicans results in damage and eventual death of these host cells (47, 48, 50, 59, 78). Moreover, the capacity of C. albicans to form hyphae is required for maximal virulence during both oropharyngeal and disseminated candidiasis (34, 47, 62).

There are also distinct differences between the pathogenesis of oropharyngeal and disseminated candidiasis. The microenvironment of the oropharynx, which contains epithelial cells, antimicrobial salivary proteins, and numerous species of bacteria, is distinct from that of the blood vessels, which contain endothelial cells, blood cells, and plasma proteins, and is normally sterile. Furthermore, some C. albicans genes, such as TPK2 and CKA2, are required for normal virulence in a murine model of oropharyngeal candidiasis, but not disseminated candidiasis (9, 47). In contrast, C. albicans IRS4 and NRG1 are necessary for maximal virulence during disseminated candidiasis, but not oropharyngeal candidiasis (4, 41, 43). These findings have led us to hypothesize that different virulence determinants and regulatory pathways enable C. albicans to initiate and maintain an infection in different host microenvironments.

Here we set out to test this hypothesis through transcriptional profiling and subsequent functional analysis. We have used the interactions of C. albicans with epithelial and endothelial cells as surrogates for animal models of disease in order to compare these distinct pathogen-cell interactions under controlled in vitro conditions. Our results distinguish gene expression patterns and functional requirements for each of these pathogenic interactions and lend overall support to the evolving view that niche-specific responses are critical for infection (6).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. albicans strains and growth conditions.

The C. albicans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were maintained on YPD agar (1% yeast extract [Difco], 2% peptone [Difco], and 2% glucose plus 2% Bacto agar). C. albicans transformants were selected on synthetic complete medium (2% dextrose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base [YNB] with ammonium sulfate, and auxotrophic supplements). For use in the experiments, the strains were grown in YPD broth at 30°C in a shaking incubator overnight. The resulting blastospores were harvested by centrifugation and enumerated with a hemacytometer as previously described (19). The strains were adjusted to the desired concentration in RPMI 1640 medium and warmed to 37°C prior to adding them to the host cells.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| CAI4-URA | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434::URA3 | Y. Fu (59) |

| 36082 | Wild type (human blood isolate) | American Type Culture Collection |

| 7392 | Wild type (human oral isolate) | T. Patterson (50) |

| BWP17 | ura3Δ::λimm434/ura3Δ::λimm434his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG | A. Mitchell (75) |

| DAY286 | ura3Δ::λimm434/ura3Δ::λimm434pARG4::URA3::arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG | A. Mitchell (13) |

| DAY185 | pARG4::URA3::arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG pHIS1::his1::his1/his1::hisG | A. Mitchell (13) |

| EpKO1 | atm1-Tn7::UAU1/atm1-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| EpKO2 | orf19.4656-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.4656-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| EpKO3 | orf19.4793-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.4793-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| EpKO4 | orf19.2398-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.2398-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| EpKO5 | clp1-Tn7::UAU1/clp1-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| EpKO6 | opt26-Tn7::UAU1/opt26-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| EpKO7 | cdc47-Tn7::UAU1/cdc47-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| EpKO8 | orf19.1504-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.1504-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| JJH34 | yck2-Tn7::UAU1/yck2-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| JJH34H | yck2-Tn7::UAU1/yck2-Tn7::URA3::pHIS1 | This study |

| JJH34C | yck2-Tn7::UAU1/yck2-Tn7::URA3::pHIS1-YCK2 | This study |

| BL35-1 | vps51-Tn7::UAU1/vps51-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL35-2 | vps51-Tn7::UAU1/vps51-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL35-1H | vps51-Tn7::UAU1/vps51-Tn7::URA3::pHIS1 | This study |

| BL35-1C | vps51-Tn7::UAU1/vps51-Tn7::URA3::pHIS1-VPS51 | This study |

| BL36 | orf19.6168-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.6168-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL37 | orf19.1766-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.1766-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL38 | orf19.3740-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.3740-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL39 | orf19.4142-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.4142-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL40 | orf19.4791-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.4791-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL41-1 | uec1-Tn7::UAU1/uec1-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL41-2 | uec1-Tn7::UAU1/uec1-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL41-1H | uec1-Tn7::UAU1/uec1-Tn7::URA3::pHIS1 | This study |

| BL41-1C | uec1-Tn7::UAU1/uec1-Tn7::URA3::pHIS1-UEC1 | This study |

| BL42 | orf19.3664-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.3664-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL43 | orf19.4894-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.4894-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL44 | orf19.1980-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.1980-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL45 | orf19.1939-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.1939-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL46 | orf19.6392-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.6392-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL48 | orf19.403-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.403-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

| BL88 | orf19.1148-Tn7::UAU1/orf19.1148-Tn7::URA3 | This study |

Epithelial and endothelial cells.

The FaDu oral epithelial cell line, originally isolated from a pharyngeal carcinoma, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. This cell line was maintained in Eagle's minimum essential medium with Earle's balanced salt solution (Irvine Scientific) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM pyruvic acid, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 IU/ml streptomycin. Endothelial cells were harvested from human umbilical veins by the method of Jaffe et al. (28). The cells were grown in M-199 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% defined bovine calf serum, and 2 mM l-glutamine with penicillin and streptomycin (16). All cell cultures were grown at 37°C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2.

Microscopic observation of C. albicans.

C. albicans blastospores were added to tissue culture-treated plastic, or 95% confluent FaDu oral epithelial cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells at 105 blastospores per cm2. After incubation for various times at 37°C, the cells were rinsed once with Hanks balanced salt solution (Irvine Scientific) to remove the unbound organisms and then fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde. The cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and imaged using differential interference contrast with a Leica Microsystems confocal microscope.

The vacuolar morphology of the C. albicans strains was visualized by pulse-chase staining with FM4-64 by a minor modification of the method of Subramanian et al. (68). Briefly, each strain was grown to log phase in YPD broth at 30°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in YPD broth, after which FM4-64 (Invitrogen) was added to achieve a final concentration of 25 μM. The cells were incubated at 30°C for 30 min and then harvested by centrifugation. They were resuspended in fresh YPD broth and incubated for an additional 90 min. During the last 60 min of this incubation, a polyclonal anti-C. albicans antibody (Biodesign International) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) was added to the medium to label the cell surface of the organisms. Next the cells were rinsed once in phosphate-buffered saline, resuspended in YNB broth (0.17% YNB, 2% glucose), and imaged by confocal microscopy.

Adherence and endocytosis assay.

The time course of C. albicans adherence to and endocytosis by oral epithelial and endothelial cells was determined by our standard differential fluorescence assay, as described previously (47, 48). Briefly, the host cells were grown on 12-mm-diameter glass coverslips and inoculated with 105 blastospores of C. albicans CAI4-URA in RPMI 1640 medium. After, 45, 90, and 180 min, the nonadherent organisms were removed by rinsing with Hanks balanced salt solution, after which the cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde. The adherent, extracellular organisms were stained with the anti-C. albicans rabbit antiserum conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568 (red fluorescence; Molecular Probes). Next, the host cells were permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100, after which the cell-associated organisms (the adherent plus endocytosed organisms) were stained with anti-C. albicans antiserum conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (green fluorescence). The coverslips were mounted inverted on a microscope slide, and the number of endocytosed and cell-associated organisms was determined by viewing the cells with an epifluorescent microscope. At least 100 organisms were counted on each coverslip, and organisms that were partially internalized were scored as being endocytosed. Each experiment was performed in triplicate on at least three separate occasions.

Damage assay.

The time course of oral epithelial and endothelial cell damage caused by C. albicans was determined using a 51Cr release assay with a minor modification of our previously described method (19, 47, 70). Briefly, the oral epithelial or endothelial cells were grown to 95% confluence in a 24-well tissue culture plate and loaded with 51Cr. They were infected with 106 blastospores of C. albicans CAI4-URA to yield the same ratio of organisms to host cells as was used in the transcriptional profiling experiments (see below). After 45, 90, and 180 min, the medium was aspirated from each well and the 51Cr content was determined by gamma counting. Next, the cells were lysed by the sequential application of 6 N NaOH and RadiacWash (Atomic Products), after which the 51Cr content of the lysate was measured. The amount of 51Cr released by epithelial or endothelial cells infected with the various C. albicans strains was compared with the amount of 51Cr released by uninfected host cells to calculate the specific release of 51Cr using the following formula: (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(total incorporation − spontaneous release). Experimental release was the amount of 51Cr released into the medium by cells infected with C. albicans. Spontaneous release was the amount of 51Cr released into the medium by uninfected host cells. Total incorporation was the sum of the amount of 51Cr released into the medium and remaining in the host cells. Each experiment was performed in triplicate on at least three separate occasions.

Isolation of C. albicans RNA.

C. albicans cells suspended in prewarmed RPMI 1640 medium were added to 15-cm-diameter polystyrene tissue culture plates containing either oral epithelial or endothelial cells. As a control, organisms were added to empty tissue culture plates that did not contain host cells (hereafter called “polystyrene”). In all experiments, the final concentration of organisms was 5 × 105 cells/cm2 and the same RNA extraction procedure was used for both the experimental and control conditions. The organisms were incubated with the host cells or plastic for 45, 90, and 180 min. At the end of each incubation period, the nonadherent organisms were removed by rinsing with ice-cold distilled water. To reduce the amount of host cell RNA, 10 ml of mammalian cell RNA extraction buffer (4 M guanidine thiocyanate, 25 mM sodium citrate, 0.5% Sarkosyl [N-lauroyl-sarcosine], and 0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol) (10) was added to each dish. This buffer lyses the host cells but leaves the fungal cells intact (18). The fungal cells were collected by centrifugation at 4°C, washed once with ice-cold diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Next, the cells were thawed on ice and the fungal RNA was extracted by the hot phenol method (32). The quality of RNA was determined using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Inc.).

To verify that the RNA extraction procedure did not significantly alter the gene expression profile of C. albicans, an alternative approach was also used. C. albicans cells suspended in prewarmed RPMI 1640 medium were added to either empty polystyrene tissue culture plates or tissue culture plates containing endothelial cells. After 90 min, the nonadherent organisms were removed by rinsing once with ice-cold distilled water. Next, 8 ml of ice-cold diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water was added to each dish, and the cells were removed with a cell scraper. They were vortexed vigorously for 30 s to lyse the host cells, after which the fungal cells were collected by a 2-min centrifugation at 4°C. They were quickly resuspended in 400 μl TES buffer (10 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) and then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The total time from rinsing the cells to freezing them in liquid nitrogen was less than 5 min. The total RNA was extracted from these cells as described above. This RNA was used for the confirmatory real-time PCR experiments described below.

C. albicans microarray.

The microarrays were constructed using the C. albicans Genome Oligo set (Qiagen), which consists of 70-mer oligonucleotide probes designed from 6,266 predicted open reading frames (ORFs) in assembly 6 of the C. albicans Genome Sequencing Project. Because multiple ALS genes were misassembled in this assembly, we added custom-designed oligonucleotides to detect ALS1, ALS2, ALS3, ALS4, ALS5/6, ALS7, and ALS9. In addition, we added probes to detect the following genes that were not represented in the original set of oligonucleotides: CDC24, CLN2, EFG1, HDA1, HOS2, HSP12, MAD2, PCL2, PLC2.3, PHO11, RBT2, RBT4, RBT7, RHO3, SNF1, SRA1, STT4, TEM1, TPK1, and TPK2. The oligonucleotides were spotted onto glass slides.

cDNA labeling and microarray hybridization.

Preparation and labeling of the cDNA and hybridization with the microarrays were performed following standard protocols (http://microarrays.org/). Briefly, 10 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) in the presence of 5-(3-aminoallyl)-2′-dUTP (aa-dUTP), using both oligo(dT) and random primers (Stratagene). The cDNAs from the control and experimental conditions were coupled with Cy3 or Cy5 monoreactive dyes (Amersham Biosciences), mixed at 1:1 ratio, and concentrated in a Microcon-30 spin column (Millipore). The concentrated probes were hybridized with the microarray slides in hybridization buffer 3 (Ambion) at 50°C for 16 h. The arrays were visualized with 428 array scanner (Affymetrix). At least three hybridizations were performed for each time point, host cell type, and strain of C. albicans.

Data analysis.

The scanned images of both channels were quantified using ImaGene 5.0 (Biodiscovery). Spots were quantified as the median value of all pixel intensities in the spot region. The local background values were calculated from the area surrounding each feature and subtracted from the respective spot signal values. The data from each array were normalized by locally weighted linear regression (lowess) analysis using the MIDAS program (http://www.tigr.org/software/).

Strain CAI4-URA, which was originally derived from the clinical isolate SC5314 (59), was used as the reference strain, and its response to both oral epithelial cells and endothelial cells was determined. To increase the power of our analysis, we also determined the transcriptional response to oral epithelial cells of another oral isolate, strain 7392 (50). We combined the data from both CAI4-URA and 7392 and considered a gene to have a significant change in transcript levels in response to oral epithelial cells only when the following two criteria were met: (i) there had to be at least a twofold difference in transcript levels between the two conditions, and (ii) this difference had to be statistically significant by the Cyber-t test (P ≤ 0.05) (71). We also determined the transcriptional response to endothelial cells of both CAI4-URA and the blood isolate, strain 36082 (17), and analyzed the data in a similar manner. Strain 7392 adheres to, invades, and damages oral epithelial cells in vitro and is virulent in a mouse model of oropharyngeal candidiasis (50; H. Park and S. G. Filler, unpublished data). Similarly, strain 36082 adheres to, invades, and damages endothelial cells in vitro and is virulent in a mouse model of disseminated candidiasis (17, 19, 25, 27, 38).

Real-time PCR.

C. albicans CAI4-URA was incubated with oral epithelial cells, endothelial cells, or polystyrene as in the microarray experiments. Next C. albicans RNA was extracted, treated with DNase I (Ambion), and then used to synthesize cDNA with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Ambion). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out using the SYBR green PCR kit (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI 7000 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's protocol. The primers used in these experiments are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The results were analyzed by the threshold cycle (2−ΔΔCT) method (33) using the transcript level of the C. albicans ACT1 gene (CaACT1) as the endogenous control. The mRNA levels for each gene were determined in at least two biological replicates, and the results were combined.

Construction of insertion mutants.

C. albicans mutants with homozygous insertions in genes that were verified to be upregulated in response to oral epithelial cells or endothelial cells were constructed using the Tn7-UAU1 transposon (13, 44). Insertion cassettes were obtained from a library of Tn7-UAU1 insertions in C. albicans CAI4 DNA that were sequenced from one end. The insertion sites for each clone are listed at http://www.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/e2k1/qzhao/page.cgi? num=1, and the specific sequence from the end of each insertion may be found through the Seq_ID link. Because insertion cassettes for orf19.403 and orf19.1148 were not present in this library, they were constructed using the Tn7-UAU1 transposon using the GPS-M mutagenesis system (NEB), following the manufacturer's protocol. Each cloned DNA insert, including the Tn7-UAU1 insertion, was excised from the plasmid backbone by digestion with NotI, and then transformed into strain BWP17 (75). Arg+ Ura+ clones with homozygous insertions were selected as previously described (13, 44). The presence of homozygous insertions was verified by whole-cell PCR using the primer sets listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The homozygous insertion mutant strains were transformed with pGEM-HIS1 (75), linearized with NruI to generate His+ strains.

Complementation of insertion mutants.

The same approach was used to complement the yck2/yck2, vps51/vps51, and uec1/uec1 insertion mutants. DNA fragments encompassing the protein-coding regions of YCK2 (orf19.7001), VPS51 (orf19.5568), or UEC1 (orf19.4646) plus ∼1,000 bp of upstream sequence and 500 bp of downstream sequence were amplified from genomic DNA of strain CAI4-URA with high-fidelity polymerase. The primers were YCK2 comp-5 and YCK2 comp-3 for YCK2, VPS51 comp-f and VPS51 comp-r for VPS51, and UEC1 comp-f and UEC1 comp-r for UEC1 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Each fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy. The fragment containing YCK2 was then subcloned into the SphI site of pGEM-HIS1 to yield pHIS1-YCK2. The fragments containing VPS51 and UEC1 were subcloned into the NruI site of pGEM-HIS1 to produce pHIS1-VPS51 and pHIS1-UEC1, respectively. pHIS1-YCK2 was linearized with PacI and transformed into strain JJH34. pHIS1-VPS51 and pHIS1-UEC1 were linearized with SalI and transformed into strains BL35 and BL41, respectively. Correct integration of the complementation plasmids was verified by PCR.

Susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides and environmental stressors.

Agar dilution assays were used to test the susceptibility of the various C. albicans strains to protamine and environmental stressors. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the strains (range 104 to 101 CFU) in 10 μl were plated onto YPD agar containing 2.8 mg/ml protamine sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich), 200 μg/ml Congo red, 1 M NaCl, 0.05% SDS, or 5 mM H2O2 and incubated at 30°C. The plates were photographed after 5 days in the protamine experiments and after 2 days when the other stressors were tested.

The susceptibility of the C. albicans strains to human β-defensin 2 was determined by a radial diffusion assay as previously described (77). Briefly, late-logarithmic-phase organisms were suspended in 1% agarose (pH 7.5) at a final concentration of 106 organisms/ml. The agar was solidified in petri dishes, and 4-mm-diameter sample wells were bored. Ten micrograms of human β-defensin 2 was added to each well, after which the dishes were overlaid with YNB agar. After incubation at 30°C for 2 days, the diameters of the zone of growth inhibition around each of the wells were measured.

Statistical analysis.

Differences in C. albicans adherence to, endocytosis by, and damage to the two different types of host cells were compared by analysis of variance. P values of ≤0.05 were considered to be significant.

Microarray data accession numbers.

The transcriptional profiling data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession no. GSE5340 (transcriptional response of C. albicans to oral epithelial cells) and GSE5344 (transcriptional response of C. albicans to endothelial cells).

RESULTS

Interactions of C. albicans with oral epithelial cells and endothelial cells.

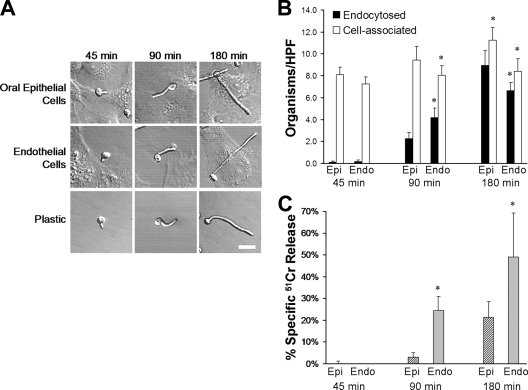

The interaction of C. albicans with host cells includes three features: germination of C. albicans to produce hyphae, binding to and endocytosis by host cells, and damage to the host cells. We first compared germination of C. albicans after contact with FaDu oral epithelial cells, endothelial cells, or polystyrene. We added blastospores of C. albicans to the different host cells or polystyrene and observed the morphology of the organisms. After 45 min, the blastospores had just begun to germinate (Fig. 1A). At subsequent time points, the resulting hyphae progressively elongated. We tested three different clinical isolates of C. albicans, and all had similar morphologies at these time points (data not shown). At each time point, the hyphae that formed in the presence of either host cell type were of similar length to those grown on polystyrene. Thus, the host cells did not visibly influence candidal germination or hyphal elongation at the time points studied. These findings also indicate that differences discussed below in the transcriptional profile of C. albicans exposed to these conditions were the result of factors other than differences in morphology.

FIG. 1.

Time course of C. albicans interaction with host cells and polystyrene. Blastospores of C. albicans strain CAI4-URA were incubated with FaDu oral epithelial cells, human umbilical vein endothelial cells, or polystyrene. (A) At the indicated times, the cells were fixed and the organisms were imaged by differential interference contrast. The scale bar indicates 5 μm. All images were taken at the same magnification. (B) The number of organisms that were endocytosed by and cell associated with the host cells at the indicated times was determined by a differential fluorescence assay. Results are means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. *, P = < 0.015 compared to oral epithelial cells at the same time point. (C) The extent of C. albicans-induced host cell damage was measured using a 51Cr release assay. Results are the means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.001 compared to oral epithelial cells at the same time point. Epi, oral epithelial cells; Endo, endothelial cells; HPF, high-powered field.

Next, we compared the time course of C. albicans adherence to, invasion of, and damage to oral epithelial cells and endothelial cells. At the 45-min time point, slightly more organisms adhered to the epithelial cells than to the endothelial cells, and very few organisms had been endocytosed (Fig. 1B). There was no detectable damage to either type of host cell at this time (Fig. 1C). After 90 min, 24% of the cell-associated organisms had been endocytosed by oral epithelial cells, whereas 50% of the cell-associated organisms had been endocytosed by endothelial cells. The epithelial cells experienced significantly less C. albicans-induced damage than did endothelial cells at this time. By 180 min, endocytosis was largely complete as the majority of cell-associated organisms had been endocytosed by both types of host cell. It is noteworthy that the oral epithelial cells endocytosed significantly more organisms than the endothelial cells, yet C. albicans caused ∼50% less damage to the epithelial cells than to the endothelial cells. The delayed endocytosis of C. albicans by oral epithelial cells and the relative resistance of these cells to C. albicans-induced damage are consistent with the model that C. albicans interacts differently with epithelial cells than endothelial cells.

C. albicans responded differently to oral epithelial cells compared to endothelial cells.

We used microarray analysis to determine the transcriptional response of C. albicans to contact with oral epithelial cells and endothelial cells. Organisms grown on polystyrene were used as the reference condition. The response of strain CAI4-URA, which was derived from the sequence strain SC5314, to both cell types was determined. To increase the power of our analysis, we also determined the oral epithelial cell response of strain 7392, which was isolated from a patient with oropharyngeal candidiasis. As our goal was to determine the core response of C. albicans to oral epithelial cells, we focused our analysis on genes whose mRNA levels changed in the same direction in both 7392 and CAI4-URA (73). Similarly, we determined the endothelial cell response of strain 36082, which was isolated from a patient with candidemia, and focused on genes whose transcript levels changed in both this strain and in CAI4-URA.

The transcript levels of only 29 C. albicans genes changed significantly in response to both epithelial and endothelial cells at 45 min, and the transcript levels of all of these genes were decreased (see Table 3). A complete list of C. albicans genes whose transcript levels changed significantly in response to either host cell type is provided in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The mRNA levels of 116 genes changed in response to epithelial cells at 90 and/or 180 min (Table 3). Interestingly, contact with endothelial cells did not alter the transcript levels of any of these genes. These results indicate that the response of C. albicans to oral epithelial cells is substantially different from its response to endothelial cells.

TABLE 3.

Overrepresented functional categories of C. albicans genes whose transcript levels were decreased in response to FaDu oral epithelial cellsa

| Time | GO term | P value | Genes annotated to the term |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45 min | Biological adhesion | 0.04 | ALS1, ALS3, ALS9, MNT1, MP65, PDE1, RFX2, SAP6, SUN41 |

| Ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis | 0.004 | DIP2, HCR1, MPP10, NIP7, RIA1, RLP24, RPB4, RPL3, RPP0, RPS15, RPS21, RPS5, RPS6A, RPS7A, RPS8A, TIF5, UTP20, YST1, orf19.1466, orf19.1833, orf19.2384, orf19.3481, orf19.4479, orf19.501, orf19.6197, orf19.7422 | |

| 90 min | Protein catabolic process | 0.006 | CDC48, DOG1, RAD16, RAD7, RPN4, SAP1, SAP6, orf19.6672 |

| Biological adhesion | 0.02 | ALS3, HWP1, MNT1, SAP1, SAP6 | |

| 180 min | Adhesion to host | 0.008 | ALS3, ALS5, HWP1, TDH3 |

The combined data from C. albicans strains CAI4-URA and 7392 were used this analysis.

Different strains of C. albicans were used in the epithelial cell experiments compared to the endothelial cell experiments. Therefore, it was possible that some of the differences in the response of C. albicans to the two types of host cells were due to the difference in C. albicans strains. To evaluate this possibility, we analyzed the microarray data of strain CAI4-URA alone to oral epithelial cells and endothelial cells. As expected, when the response of a single strain was used, many more genes had changes in transcript levels. A total of 1,424 genes had significant changes in transcript levels after 45, 90, and 180 min of contact with epithelial or endothelial cells compared to polystyrene. However, only 160 (11%) of these genes had transcript levels that changed in the same direction in response to both cell types. These results support our conclusion that the response of C. albicans to oral epithelial cells is substantially different from its response to endothelial cells.

Next, we used Gene Ontology (GO) term analysis to determine the functional categories of the C. albicans genes whose transcript level changed in response to epithelial and endothelial cells. A large percentage of these genes did not have GO terms associated with them (Table 2). As a result, the genes whose transcripts were increased in response to either type of host cell were not significantly enriched for any GO term. Also, no GO term was significantly overrepresented among the genes whose transcripts were decreased in response to endothelial cells. Interestingly, the genes with reduced transcript levels in response to epithelial cells were significantly enriched in three functional categories. Genes related to adhesion were overrepresented at all three time points (P < 0.04 at each time point) (Table 3). Also, genes involved in ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis were significantly enriched at 45 min (P = 0.004). Finally, genes related to the protein catabolic process were overrepresented at 90 min. Collectively, these data suggest that C. albicans responds to contact with epithelial cells by reducing expression of adhesins. There is also decreased protein synthesis that may be counteracted by a reduction in protein catabolism.

TABLE 2.

Number of C. albicans genes with significant changes in transcript levels in response to FaDu oral epithelial cells and endothelial cells by microarray analysis

| Time | Direction of change | No. of genesa

|

% of uncharacterized genes

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epithelial cells | Endothelial cells | Both cell types | Epithelial cells | Endothelial cells | ||

| 45 min | Increase | 31 | 9 | 29b | 53 | 44 |

| Decrease | 211 | 54 | 36 | 35 | ||

| 90 min | Increase | 8 | 35 | 0 | 38 | 43 |

| Decrease | 54 | 19 | 32 | 33 | ||

| 180 min | Increase | 12 | 33 | 0 | 33 | 27 |

| Decrease | 32 | 23 | 38 | 36 | ||

Results represent the combined data from C. albicans strains CAI4-URA and 7392 for the epithelial cell data and strains CAI4-URA and 36082 for the endothelial cell data.

All genes had a decrease in transcript levels.

Functional analysis of differentially induced genes.

We used real-time PCR using RNA from strain CAI4-URA to verify the increased transcript levels of selected genes identified in the microarray experiments. The verification experiments focused on genes for which Tn7-UAU1 transposon insertion cassettes (7, 13, 42) were available and whose function had not been studied previously. Real-time PCR assays verified that the transcripts of 13 C. albicans genes were significantly increased in response to oral epithelial cells compared to polystyrene (Table 2). Similarly, we confirmed that the transcripts of 15 C. albicans genes were significantly increased in response to endothelial cells. These measurements confirm our microarray results, thus strengthening the argument that C. albicans interacts with and responds differently to these distinct host cell types.

To verify that the observed changes in gene transcript levels were induced by contact with the host cells and not by the RNA isolation procedure, we infected endothelial cells and polystyrene with C. albicans CAI4-URA for 90 min. Next, the host cells were lysed in ice-cold distilled water, after which the C. albicans cells were collected and then snap-frozen. The total time between adding the distilled water and snap-freezing the fungal cells was less than 5 min. We then used real-time PCR to measure the transcript levels of YCK2, orf19.5568, and orf19.4646. When CaACT1 was used as the endogenous control gene, the transcripts of YCK2, orf19.5568, and orf19.4646 increased by 1.8-, 2.2-, and 1.8-fold, respectively, in response to endothelial cells compared to polystyrene. A similar increase was also observed when either CaTDH3 or CaTEF1 was used as the endogenous control gene (data not shown), indicating that CaACT1 was an appropriate endogenous control gene for the real-time PCR experiments.

For genes whose transcripts were found by real-time PCR to be increased by at least 1.5-fold in response to epithelial cells or endothelial cells, we constructed homozygous insertion mutants using the Tn7-UAU1 transposon insertion cassettes. We generated mutant strains with homozygous insertions in 8 of the 13 genes whose transcripts were increased in response to epithelial cells and 14 of the 15 genes whose transcripts were increased in response to endothelial cells (Tables 1 and 4). Among the six genes for which we were unable to construct homozygous insertion mutants, orf19.202 and orf19.3260 have essential orthologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (MCM7 and CAB3, respectively). The others are predicted to participate in vital cellular processes, including cell wall biogenesis, transcription, or mitochondrial function, so that homozygous mutations may cause lethality or very slow growth.

TABLE 4.

List of genes for generation of insertion mutant strains

| ORF19 no. | Gene name | Possible function | Fold change bya:

|

TIGR insertion ID | Insertion mutation | Hyphae | Host cell damage (% of wild type ± SD)b

|

Protamine susceptibility | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray

|

Real-time PCR

|

|||||||||||

| Epithelial | Endothleial | Epithelial | Endothelial | Epithelial | Endothelial | |||||||

| orf19.348 | Uncharacterized | 2.2 | 1.0 | 2.5 | NDc | CAGOO23 | No | |||||

| orf19.1077 | ATM1 | Member of MDR subfamily of ABC family | 2.2 | 1.1 | 3.5 | ND | CAGQD15 | Yes | Normal | 91 ± 5 | ND | Normal |

| orf19.4656 | Uncharacterized | 2.2 | −1.1 | 3.8 | ND | CAGPD46 | Yes | Normal | 112 ± 4 | ND | Normal | |

| orf19.4793 | Uncharacterized | 2.0 | −1.1 | 1.6 | ND | CAGAQ76 | Yes | Normal | 111 ± 15 | ND | Normal | |

| orf19.6266 | Uncharacterized, CCR4-NOT core complex | 2.0 | −1.1 | 2.5 | ND | CAGB385 | No | |||||

| orf19.2398 | Uncharacterized | 2.1 | 1.2 | 2.5 | ND | CAGN836 | Yes | Normal | 114 ± 8 | ND | Normal | |

| orf19.6931 | CLP1 | Uncharacterized, probable cleavage/polyadenylation factor | 2.0d | −1.5 | 1.9 | ND | CAGI909 | Yes | Normal | 109 ± 24 | ND | Normal |

| orf19.200 | THO1 | Uncharacterized | 2.1e | −1.1e | 2.5e | ND | CAGDN85 | No | ||||

| orf19.4655 | OPT6 | Putative oligopeptide transporter | 2.4e | −1.7e | 3.1e | ND | CAGFI33 | Yes | Normal | 94 ± 9 | ND | Normal |

| orf19.7001 | YCK2 | Casein kinase I (by homology) | 2.2e | −1.4e | 3.5e | 2.0e | CAGDI41 | Yes | Short/multiple | 48 ± 8 | 79 ± 8 | Increased |

| orf19.202 | CDC47 | Cell division control protein | 2.5e | −1.5e | 1.6e | ND | CAGCJ23 | No | ||||

| orf19.1504 | Uncharacterized, putative patatin-like phospholipase | 2.6 | 1.1 | 4.3 | ND | CAGBR73 | Yes | Normal | 107 ± 13 | ND | Normal | |

| orf19.3455 | LPE10 | Uncharacterized, putative magnesium transporter activity | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.6 | ND | CAGDF12 | No | ||||

| orf19.4922 | Uncharacterized | 2.3 | 1.0 | 1.6 | ND | CAGF844 | Yes | Normal | 122 ± 10 | ND | Normal | |

| orf19.3260 | SIS2 | Uncharacterized | −1.2 | 2.1d | ND | 3.0d | CAGB279 | No | ||||

| orf19.5568 | VPS51 | Protein targeting to vacuole (by homology) | 1.2d | 2.1d | 2.2d | 2.9d | CAGDP76 | Yes | Short | 2 ± 13 | 3 ± 4 | Increased |

| orf19.6168 | Uncharacterized, possible structural constituent of cytoskeleton | 1.2 | 2.3 | ND | 2.4 | CAGEP09 | Yes | Normal | ND | 97 ± 9 | Normal | |

| orf19.1766 | IFO3 | Uncharacterized, similar to Streptomyces coelicolor putative hydrolase | 1.3 | 2.1 | ND | 1.8 | CAGL436 | Yes | Normal | ND | 80 ± 3 | Normal |

| orf19.3740 | PGA23 | Putative glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein with unknown function | 1.0d | 2.7d | ND | 2.8d | CAGN829 | Yes | Normal | ND | 99 ± 2 | Normal |

| orf19.4142 | Uncharacterized | 1.0d | 2.4d | ND | 1.6d | CAGC641 | Yes | Normal | ND | 71 ± 16 | Normal | |

| orf19.4791 | Uncharacterized | −1.8d | 2.0d | ND | 2.2d | CAGE249 | Yes | Normal | ND | 107 ± 9 | Normal | |

| orf19.4646 | UEC1 | Uncharacterized | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 3.4 | CAGLQ62 | Yes | Thickened | 36 ± 18 | 91 ± 5 | Increased |

| orf19.3664 | HSP31 | Heat shock protein (by homology) | −1.8 | 2.2 | ND | 4.9 | CAGJM81 | Yes | Normal | ND | 84 ± 13 | Normal |

| orf19.4894 | Uncharacterized | −1.5d | 3.4d | ND | 2.3d | CAGKC82 | Yes | Normal | ND | 73 ± 11 | Normal | |

| orf19.1980 | GIT4 | Putative glycerophosphoinositol permease | 1.1d | 2.5d | ND | 1.7d | CAGP819 | Yes | Normal | ND | 77 ± 12 | Normal |

| orf19.1939 | Uncharacterized | −1.1d | 2.1d | ND | 1.5d | CAGM083 | Yes | Normal | ND | 67 ± 6 | Normal | |

| orf19.6392 | Uncharacterized | −1.1d | 2.3d | ND | 1.5d | CAGJP50 | Yes | Normal | ND | 96 ± 16 | Normal | |

| orf19.403 | PCL2 | Cyclin-dependent protein kinase | −1.3d | 2.3d | ND | 2.0d | —f | Yes | Normal | ND | 94 ± 6 | Normal |

| orf19.1148 | CIS312 | Uncharacterized | 1.0 | 2.4 | ND | 2.5 | —f | Yes | Normal | ND | 96 ± 6 | Normal |

After 45 min of incubation unless otherwise specified.

The wild-type control strain was DAY185.

ND, not determined.

After 90 min of incubation.

After 180 min of incubation.

—, insertion cassettes for orf19.403 and orf19.1148 were made in the present study.

The 22 insertion mutants were screened for defects in virulence-related phenotypes, including hyphal formation and capacity to damage epithelial and endothelial cells (34, 47, 59, 62). In addition, because C. albicans is likely exposed to host antimicrobial peptides during oropharyngeal and disseminated candidiasis, the mutants were tested for their susceptibility to protamine. Protamine is a helical cationic polypeptide that is often used to screen for antimicrobial peptide susceptibility (22, 76).

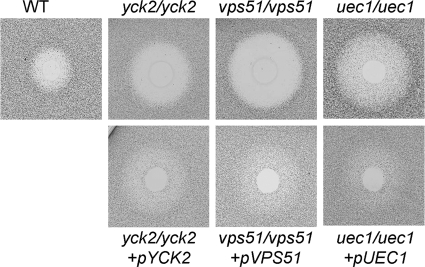

We found that mutants with insertions in YCK2 (orf19.7001), orf19.5568, orf19.4646, and orf19.1939 had defects in at least one of the following characteristics: hyphal formation, host cell damage, and protamine resistance (Table 4). These phenotypes were shared with at least one additional independent insertion mutant for each gene. To verify that each insertion mutation caused the phenotypic defect, the mutants were complemented with the respective wild-type allele. This approach linked the mutant phenotypes to insertions in YCK2, orf19.5568, and orf19.4646. YCK2 encodes the highly conserved serine/threonine kinase, casein kinase 1 (CK1). orf19.5568 has no S. cerevisiae ortholog, but the predicted protein product has limited homology to S. cerevisiae Vps51, a component of the Vps53 complex. This complex is required for fusion of endosome-derived vesicles with the late Golgi compartment (11, 53, 64). Based on our phenotypic analysis below, we suggest the provisional name “VPS51” for orf19.5568. orf19.4646 specifies a unique protein that does not share significant homology with any other protein, including the predicted proteins of the closely related species Candida dubliniensis. Because expression of orf19.4646 was increased in response to endothelial cells, we named it “UEC1” (for up-regulated by endothelial cells).

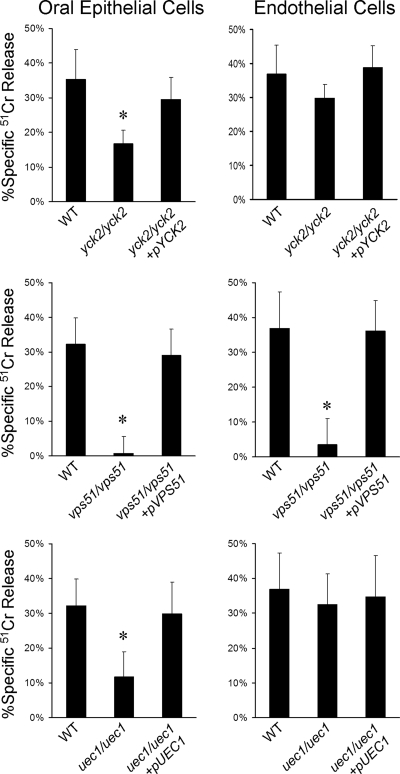

YCK2 governs cell polarity and is necessary for maximal epithelial cell damage.

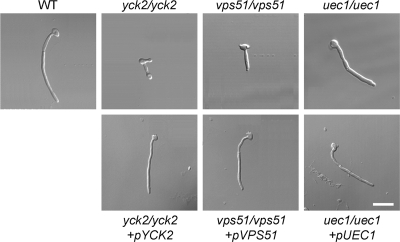

YCK2 mRNA was increased in response to contact with either oral epithelial or endothelial cells, as indicated by real-time PCR measurements (Table 4). The yck2/yck2 insertion mutant produced multiple short hyphae on epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and plastic, suggesting that it had a defect in polarized growth (Fig. 2) (data not shown). It had significantly reduced capacity to damage oral epithelial cells, but not endothelial cells, and this defect was reversed by complementation (Fig. 3). Prior studies indicate that mutant germination defects are invariably associated with endothelial cell damage defects (48, 59), so the yck2/yck2 mutant is novel in separating these two phenotypes.

FIG. 2.

Morphology of the yck2/yck2, vps51/vps51, and uec1/uec1 insertion mutants. Blastospores of the indicated strains were incubated on plastic for 180 min and then were fixed and imaged by differential interference contrast. The scale bar indicates 5 μm. All images were taken at the same magnification. WT, wild-type strain DAY185.

FIG. 3.

Damage to oral epithelial cells and endothelial cells caused by the yck2/yck2, vps51/vps51, and uec1/uec1 insertion mutants. The indicated strains were incubated with FaDu oral epithelial cells or endothelial cells for 180 min, after which the extent of host cell damage was assessed using a 51Cr release assay. *, P < 0.01 compared to both the wild-type (WT) strain (DAY185) and complemented strains.

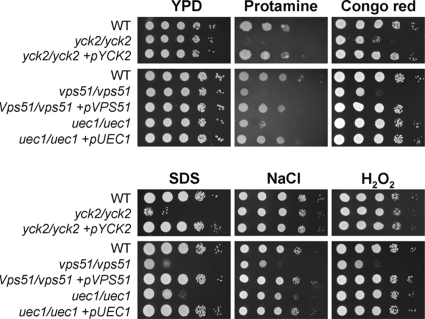

The yck2/yck2 mutant also had impaired response to stress. It had markedly increased susceptibility to protamine, Congo red, and SDS (Fig. 4). As predicted by the protamine results, this mutant also had increased susceptibility to human β-defensin 2 (Fig. 5), which is made by oral epithelial cells (1, 29, 39), All defects of the yck2/yck2 mutant were due to the insertions in YCK2 because complementing this mutant with a wild-type copy of YCK2 restored the wild-type phenotype in all assays. Collectively, these results suggest that in C. albicans, YCK2 governs polarized growth, capacity to damage epithelial cells, and resistance to environmental stress.

FIG. 4.

Susceptibility of the yck2/yck2, vps51/vps51, and uec1/uec1 insertion mutants to stressors. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the indicated strains were plated onto YPD agar containing 2.8 mg/ml protamine sulfate, 200 μg/ml Congo red, 1 M NaCl, 0.05% SDS, or 5 mM H2O2 and incubated at 30°C. The plates containing protamine were photographed after 5 days, and the other plates were photographed after 2 days. WT, wild-type strain (DAY185).

FIG. 5.

Susceptibility of the yck2/yck2, vps51/vps51, and uec1/uec1 insertion mutants to human β-defensin 2. The susceptibility of the indicated strains of C. albicans to human β-defensin 2 was measured using a radial diffusion assay. The zones of growth inhibition were imaged after incubation at 30°C for 2 days. WT, wild-type strain (DAY185).

VPS51 is required for hyphal elongation, maximal damage to host cells, and stress resistance.

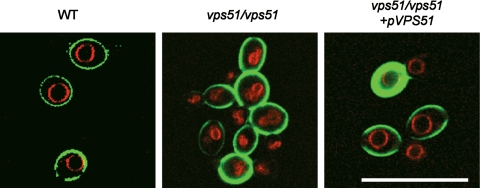

VPS51 mRNA levels were also increased in response to contact with either oral epithelial or endothelial cells, as indicated by real-time PCR measurements (Table 4). The vps51/vps51 insertion mutant produced unbranched hyphae that were shorter than those of the wild-type strain when it was grown on epithelial cells, endothelial cells, or plastic (Fig. 2) (data not shown). This mutant had a severe defect in its capacity to damage both epithelial and endothelial cells (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the vps51/vps51 insertion mutant had significantly increased susceptibility to all stressors tested (Fig. 4 and 5). To verify that VPS51 did indeed specify a protein involved in vacuolar function, we stained the vps51/vps51 insertion mutant with FM4-64, which stains the vacuolar membrane (72). The vacuoles of this mutant were highly fragmented (Fig. 6), similar to the vacuolar morphology of the S. cerevisiae vps51Δ mutant (53). In contrast, the vacuoles of the wild-type cells were much larger and either single or multilobed. Complementing the vps51/vps51 insertion mutant with a wild-type copy of VPS51 rescued all of these defects. Therefore, VPS51 is necessary in C. albicans for normal vacuolar morphology as well as many virulence-related phenotypes.

FIG. 6.

Abnormal vacuolar morphology of the vps51/vps51 insertion mutant. Blastospores of the indicated strains were grown to the mid-log phase and then pulse-chased with FM4-64 to label their vacuolar membranes. The cell walls were stained with an Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-C. albicans antibody, after which the cells were imaged by confocal microscopy. The cell walls are shown in green, and the vacuolar membranes are show in red. The scale bar indicates 5 μm. WT, wild-type strain (DAY185).

UEC1 is required for maximal epithelial cell damage and protamine resistance.

UEC1 mRNA levels were increased by contact with endothelial cells, but not epithelial cells (Table 4). Under all conditions tested, the uec1/uec1 insertion mutant produced hyphae that were as long as those of the wild-type strain but slightly thicker (Fig. 2) (data not shown). Although UEC1 transcript levels were not increased by contact with epithelial cells, the uec1/uec1 insertion mutant had significantly reduced capacity to damage these cells (Fig. 3). However, it did not have an endothelial cell damage defect. The uec1/uec1 insertion mutant also had significantly increased susceptibility to protamine, SDS, and human β-defensin 2, as well as a slight increase in susceptibility to NaCl (Fig. 4 and 5). These defects were rescued by complementing the insertion mutant with a wild-type copy of UEC1. Taken together, these results indicate that UEC1 is necessary for C. albicans to cause normal damage epithelial cells in vitro, perhaps by governing cell membrane integrity.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here demonstrate that C. albicans interacts differently with oral epithelial cells compared to endothelial cells. C. albicans hyphae were endocytosed more slowly by epithelial cells and caused less damage to these cells than endothelial cells. Also, the transcriptional response of C. albicans to epithelial cells was different from its response to endothelial cells. Interestingly, the C. albicans genes whose transcripts were increased in response to either of these cell types were also different from those that have been reported to be induced by exposure to monocytes or neutrophils (35, 58). These divergent responses to different types of host cells likely enable C. albicans to survive and proliferate in diverse anatomic sites within the host.

To our knowledge, the transcriptional response of C. albicans to endothelial cells has not been determined previously. However, two other groups of investigators have studied the response of this organism to contact with vaginal, cervical, and intestinal epithelial cell lines as compared to polystyrene (60, 65). Both groups found that contact with epithelial cells caused only a two- to fourfold change in C. albicans gene transcript levels. This magnitude of differential transcript levels is comparable to the results reported here. Sohn et al. (65) found that, when C. albicans was added to either vaginal or intestinal cell lines, the transcript levels of most genes changed within 30 to 60 min of contact; the mRNA of very few genes changed after 120 min of contact with these epithelial cells. Our results reported here lead to a similar conclusion.

The prior epithelial cell interaction studies (60, 65) reported that contact with epithelial cells increased mRNA levels of C. albicans cell surface protein genes, including ALS2, ALS5, HWP1, PRA1, and PGA7. In contrast, we found that the transcript levels of some adhesin genes actually fell in response to epithelial cells. Sohn et al. (65) noted that HWP1 transcripts were induced simply by contact with a solid support, so it is possible that that HWP1 transcript levels were stimulated more strongly by contact with polystyrene than by contact with epithelial cells. Also, PRA1 orthologs in S. cerevisiae and Aspergillus fumigatus are members of a zinc-responsive regulon (36, 63), and recent results verify the induction of C. albicans PRA1 by zinc limitation (Nobile et al., unpublished data). Thus, it seems likely that competition for zinc by host cells and C. albicans cells may have caused the PRA1 induction reported by Sandovsky-Losica et al. (60), and our failure to detect its upregulation may simply reflect a higher zinc level in our medium. Other key differences between these other microarray studies and ours include differences in the epithelial cell type, growth media, and strains of C. albicans used.

The microarray studies also suggested that contact with oral epithelial cells resulted in an early reduction of protein synthesis followed by a decrease in protein catabolism. Inhibition of genes involved in protein synthesis also occurs when the organism is ingested by macrophages and neutrophils, and in response to nitric oxide (20, 24, 35). The downregulation of genes involved in protein synthesis may be a response to stress (24, 35). It is known that oral epithelial cells can inhibit the growth of C. albicans (66, 67). Even though we did not observe any reduction in growth or hyphal elongation at the time points studied, it is possible that inhibition of protein synthesis may have preceded growth inhibition, which might have been detectable after longer incubation times.

Zakikhany et al. (78) used microarrays to analyze the transcript levels of C. albicans during infection of reconstituted human epithelium in vitro. They also analyzed C. albicans gene expression in samples from patients with pseudomembranous oropharyngeal candidiasis. In these analyses, the reference condition was C. albicans blastospores grown to the mid-log phase in YPD broth. Because contact with epithelial cells induces hyphal formation, the microarray data of Zakikhany et al. were enriched in hyphal-associated genes, such as ALS3, HYR1, RBT1, and ECE1 (78). In the present experiments, the reference condition (contact with polystyrene) caused the organisms to form hyphae, and thus increased transcript levels that were induced by hyphal formation alone were not detected. However, Zakikhany et al. found that a large proportion of genes with increased transcript levels during the early phase of infection had not been previously characterized (78), similar to the results presented here.

The main value of our expression profiling results comes from the implication of new genes in the process of C. albicans-host cell interaction. Our analysis of mutants defective in upregulated genes indicates that a relatively modest change in gene expression can nonetheless be biologically significant. Of the 22 unique insertion mutants reported here, 3 (14%) had defective capacity to damage epithelial or endothelial cells. In contrast, our previous screen of unselected C. albicans insertion mutants yielded only 3 (1.6%) of 183 mutants with consistent defects (9). Therefore, the use of microarray data to guide candidate gene selection significantly improves the efficiency of virulence-associated gene identification.

Mutants with insertion in YCK2, VPS51, and UEC1 all had defects in damaging oral epithelial cells, while only the vps51/vps51 insertion mutant had a defect in damaging endothelial cells. We also found that the wild-type strain of C. albicans caused less damage to epithelial cells than to endothelial cells. We hypothesize that oral epithelial cells may be relatively resistant to C. albicans-induced damage because oral epithelial cells frequently encounter C. albicans even in normal hosts, whereas endothelial cells do not. Our microarray data also suggest the possibility that oral epithelial cells may actually induce downregulation of some C. albicans genes (such as those involved in protein synthesis) that are likely required for the organism to cause maximal epithelial cell damage.

Damage to epithelial and endothelial cells requires that C. albicans adheres to and invades these cells and that it secretes lytic enzymes (9, 26, 43, 47, 50). Therefore, it is probable that the yck2/yck2, vps51/vps51, and uec1/uec1 insertion mutants have defects in one or more of these processes. Furthermore, mutants with reduced capacity to damage epithelial cells or endothelial cells in vitro have a high probability of having attenuated virulence in mouse models of oropharyngeal or hematogenously disseminated candidiasis (9, 47, 59). Collectively, our results suggest that YCK2, VPS51, and UEC1 may influence the virulence of C. albicans.

It was notable that all three insertion mutants also had increased susceptibility to the antimicrobial peptides, protamine and human β-defensin 2. C. albicans is exposed to antimicrobial peptides, such as histatins and defensins, when it is in the oral cavity. The organism also encounters defensins and antimicrobial chemokines as it disseminates hematogenously and interacts with leukocytes and endothelial cells. Our finding that three of the genes that were upregulated in response to either epithelial or endothelial cells were required for C. albicans to resist antimicrobial peptides suggests that contact with these host cells induces a protective reaction that enables C. albicans to withstand these peptides. The capacity to tolerate antimicrobial peptides is important for C. albicans virulence because the extent of antimicrobial peptide resistance is directly related to virulence in animal models of disseminated candidiasis (22, 76).

C. albicans Yck2 shares extensive homology with S. cerevisiae Yck2 and slightly less homology with S. cerevisiae Yck1, which are the two plasma membrane-associated isoforms of CK1 in this yeast. BLAST searches of the C. albicans genome did not identify a YCK1 ortholog, suggesting that C. albicans has only a single plasma membrane-associated isoform of CK1. In S. cerevisiae, Yck2 and Yck1 are required for normal bud morphogenesis, cytokinesis, and endocytosis (2, 56). Strains of S. cerevisiae with reduced plasma membrane CK1 activity have defects in cell polarity (56). The early branching phenotype of the C. albicans yck2/yck2 insertion mutant suggests that Yck2 is also required for maintenance of cell polarity in C. albicans.

Vps51 was first identified in S. cerevisiae, where it functions in a complex with Vps52, Vps53, and Vps54 (53, 64). This complex is required for retrograde protein traffic from the early endosome to the late Golgi compartment. Mutants that lack any of the subunits of this complex have missorting of vacuolar proteins, abnormal Golgi membrane proteins, and fragmented vacuoles (12, 53). While vacuoles are not required for growth under nutrient-rich conditions, they are important for S. cerevisiae to resist stress due to starvation, changes in environmental pH, and hyperosmolarity (5). The Vps51-54 complex has not been studied previously in C. albicans. However, a vps11Δ/vps11Δ mutant of C. albicans, which does not contain a vacuole, has delayed germination and increased susceptibility to osmotic stress due to glycerol or high NaCl (45). It also has markedly reduced secretion of secreted aspartyl proteinases and lipases, enzymes that have been implicated in damaging host cells (26, 46). The abnormal vacuole, shortened hyphae, and increased susceptibility to environmental stress of the C. albicans vps51/vps51 insertion mutant are consistent with the probable role of Vps51 in vacuolar function. The impaired capacity of the vps51/vps51 insertion mutant to damage epithelial and endothelial cells is probably due to multiple factors, including abnormal hyphal formation and possibly reduced secretion of hydrolytic enzymes.

Our recommendation that orf19.5568 be named “VPS51” is based upon three considerations. First, as discussed above, the C. albicans mutant has several phenotypes that would be expected to result from a Vps51 defect. Second, although the homology between CaVps51 and ScVps51 is limited (64% similarity over 56 residues; P = 4.6e−06), it spans the most highly conserved region of ScVps51 among fungi (residues 90 to 145; see http://www.yeastgenome.org/cache/fungi/YKR020W.html). Third, we note that ScVps51 does not have a closer homolog than CaVps51 among C. albicans predicted proteins. Thus, this gene name recommendation is based upon independent lines of evidence.

UEC1 encodes a unique 145-amino-acid protein. The function of Uec1 cannot be inferred from its primary amino acid sequence as it has no close orthologs and Pfam analysis does not reveal any conserved domains. Although UEC1 is listed as a dubious ORF in the Candida Genome Database, our results suggest that it is a functional gene for the following reasons. First, the microarray and real-time PCR data indicate that UEC1 is transcribed. Second, homozygous insertions in the UEC1 locus induced a mutant phenotype. In principle, these properties might be expected for a 5′ regulatory transcript, as has been described for the S. cerevisiae SER3 gene (37). However, we were able to complement the uec1/uec1 insertion mutant with a wild-type copy of UEC1, integrated ectopically at the HIS1 locus, to restore the wild-type phenotype. This observation argues that the uec1::Tn7-UAU1 insertion phenotype does not result from a cis-acting effect on a neighboring gene. While the exact function of Uec1 remains to be determined, our finding that the uec1/uec1 insertion mutant had increased susceptibility to the cell membrane's stressors, antimicrobial peptides and SDS, suggests that Uec1 may be required for maintenance of cell membrane integrity.

In summary, our microarray analysis demonstrates that the transcriptional response of C. albicans to oral epithelial cells is significantly different from its response to vascular endothelial cells. Furthermore, a significant fraction of the C. albicans genes whose transcript levels are increased upon contact with either of these host cells are uncharacterized. Some of these genes, such as YCK2, VPS51, and UEC1, are required for the organism to damage host cells and resist the types of environmental stress that it likely encounters during growth in the oropharynx and bloodstream.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Q. Trang Phan for expert support with tissue culture, Deborah Kupferwasser for technical assistance, and the perinatal nurses of the Harbor-UCLA General Clinical Research Center for collection of umbilical cords. We are also grateful for Shelley Lane's assistance with the microarray experiments and Matthew Schibler of the Microscopy/Spectroscopy Core Facility at the California NanoSystems Institute of the University of California, Los Angeles, for help with confocal microscopy. We appreciate the Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org/) for providing genomic sequence data and protein information for C. albicans. We thank Qi Zhao and William C. Nierman (J. Craig Venter Institute) and Frank J. Smith (Columbia University) for providing Candida gene disruption cassettes.

The insertion library project was accomplished with the support of NIH 1R01AI057804. This study was supported by Public Health Service grants 5R01DE13974, 1R01DE017088, R01AI054928, RO1AI19990, and MO1RR00425 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 August 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abiko, Y., Y. Jinbu, T. Noguchi, M. Nishimura, K. Kusano, P. Amaratunga, T. Shibata, and T. Kaku. 2002. Upregulation of human beta-defensin 2 peptide expression in oral lichen planus, leukoplakia and candidiasis. an immunohistochemical study. Pathol. Res. Pract. 198:537-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babu, P., J. D. Bryan, H. R. Panek, S. L. Jordan, B. M. Forbrich, S. C. Kelley, R. T. Colvin, and L. C. Robinson. 2002. Plasma membrane localization of the Yck2p yeast casein kinase 1 isoform requires the C-terminal extension and secretory pathway function. J. Cell Sci. 115:4957-4968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bader, M. S., S. M. Lai, V. Kumar, and D. Hinthorn. 2004. Candidemia in patients with diabetes mellitus: epidemiology and predictors of mortality. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 36:860-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badrane, H., S. Cheng, M. H. Nguyen, H. Y. Jia, Z. Zhang, N. Weisner, and C. J. Clancy. 2005. Candida albicans IRS4 contributes to hyphal formation and virulence after the initial stages of disseminated candidiasis. Microbiology 151:2923-2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banta, L. M., J. S. Robinson, D. J. Klionsky, and S. D. Emr. 1988. Organelle assembly in yeast: characterization of yeast mutants defective in vacuolar biogenesis and protein sorting. J. Cell Biol. 107:1369-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, A. J., F. C. Odds, and N. A. Gow. 2007. Infection-related gene expression in Candida albicans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:307-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruno, V. M., and A. P. Mitchell. 2005. Regulation of azole drug susceptibility by Candida albicans protein kinase CK2. Mol. Microbiol. 56:559-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cawson, R. A., and K. C. Rajasingham. 1972. Ultrastructural features of the invasive phase of Candida albicans. Br. J. Dermatol. 87:435-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiang, L. Y., D. C. Sheppard, V. M. Bruno, A. P. Mitchell, J. E. Edwards, Jr., and S. G. Filler. 2007. Candida albicans protein kinase CK2 governs virulence during oropharyngeal candidiasis. Cell. Microbiol. 9:233-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conibear, E., J. N. Cleck, and T. H. Stevens. 2003. Vps51p mediates the association of the GARP (Vps52/53/54) complex with the late Golgi t-SNARE Tlg1p. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:1610-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conibear, E., and T. H. Stevens. 2000. Vps52p, Vps53p, and Vps54p form a novel multisubunit complex required for protein sorting at the yeast late Golgi. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:305-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis, D. A., V. Bruno, L. Loza, S. G. Filler, and A. P. Mitchell. 2002. C. albicans Mds3p, a conserved regulator of pH responses and virulence identified through insertional mutagenesis. Genetics 162:1573-1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eversole, L. R., P. A. Reichart, G. Ficarra, A. Schmidt-Westhausen, P. Romagnoli, and N. Pimpinelli. 1997. Oral keratinocyte immune responses in HIV-associated candidiasis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 84:372-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farah, C. S., R. B. Ashman, and S. J. Challacombe. 2000. Oral candidosis. Clin. Dermatol. 18:553-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filler, S. G., B. O. Ibe, A. S. Ibrahim, M. A. Ghannoum, J. U. Raj, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 1994. Mechanisms by which Candida albicans induces endothelial cell prostaglandin synthesis. Infect. Immun. 62:1064-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filler, S. G., B. O. Ibe, P. M. Luckett, J. U. Raj, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 1991. Candida albicans stimulates endothelial cell eicosanoid production. J. Infect. Dis. 164:928-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filler, S. G., A. S. Pfunder, B. J. Spellberg, J. P. Spellberg, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 1996. Candida albicans stimulates cytokine production and leukocyte adhesion molecule expression by endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64:2609-2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filler, S. G., J. N. Swerdloff, C. Hobbs, and P. M. Luckett. 1995. Penetration and damage of endothelial cells by Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 63:976-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fradin, C., P. De Groot, D. MacCallum, M. Schaller, F. Klis, F. C. Odds, and B. Hube. 2005. Granulocytes govern the transcriptional response, morphology and proliferation of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol. Microbiol. 56:397-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu, Y., A. S. Ibrahim, D. C. Sheppard, Y. C. Chen, S. W. French, J. E. Cutler, S. G. Filler, and J. E. Edwards. 2002. Candida albicans Als1p: an adhesin that is a downstream effector of the EFG1 filamentation pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 44:61-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gank, K. D., M. R. Yeaman, S. Kojima, N. Y. Yount, H. Park, J. E. Edwards, Jr., S. G. Filler, and Y. Fu. 2008. SSD1 is integral to host defense peptide resistance in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 7:1318-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hajjeh, R. A., A. N. Sofair, L. H. Harrison, G. M. Lyon, B. A. Arthington-Skaggs, S. A. Mirza, M. Phelan, J. Morgan, W. Lee-Yang, M. A. Ciblak, L. E. Benjamin, L. T. Sanza, S. Huie, S. F. Yeo, M. E. Brandt, and D. W. Warnock. 2004. Incidence of bloodstream infections due to Candida species and in vitro susceptibilities of isolates collected from 1998 to 2000 in a population-based active surveillance program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1519-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hromatka, B. S., S. M. Noble, and A. D. Johnson. 2005. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans to nitric oxide and the role of the YHB1 gene in nitrosative stress and virulence. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:4814-4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibrahim, A. S., S. G. Filler, M. A. Ghannoum, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 1993. Interferon-gamma protects endothelial cells from damage by Candida albicans. J. Infect. Dis. 167:1467-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibrahim, A. S., S. G. Filler, D. Sanglard, J. E. Edwards, Jr., and B. Hube. 1998. Secreted aspartyl proteinases and interactions of Candida albicans with human endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 66:3003-3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim, A. S., F. Mirbod, S. G. Filler, Y. Banno, G. T. Cole, Y. Kitajima, J. E. Edwards, Jr., Y. Nozawa, and M. A. Ghannoum. 1995. Evidence implicating phospholipase as a virulence factor of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 63:1993-1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaffe, E. A., R. L. Nachman, C. G. Becker, and C. R. Minick. 1973. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J. Clin. Investig. 52:2745-2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joly, S., C. Maze, P. B. McCray, Jr., and J. M. Guthmiller. 2004. Human β-defensins 2 and 3 demonstrate strain-selective activity against oral microorganisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1024-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamai, Y., M. Kubota, Y. Kamai, T. Hosokawa, T. Fukuoka, and S. G. Filler. 2002. Contribution of Candida albicans ALS1 to the pathogenesis of experimental oropharyngeal candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 70:5256-5258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamai, Y., M. Kubota, T. Hosokawa, T. Fukuoka, and S. G. Filler. 2001. New model of oropharyngeal candidiasis in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3195-3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kohrer, K., and H. Domdey. 1991. Preparation of high molecular weight RNA. Methods Enzymol. 194:398-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo, H. J., J. R. Kohler, B. DiDomenico, D. Loebenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G. R. Fink. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90:939-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorenz, M. C., J. A. Bender, and G. R. Fink. 2004. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1076-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyons, T. J., A. P. Gasch, L. A. Gaither, D. Botstein, P. O. Brown, and D. J. Eide. 2000. Genome-wide characterization of the Zap1p zinc-responsive regulon in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7957-7962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martens, J. A., P. Y. Wu, and F. Winston. 2005. Regulation of an intergenic transcript controls adjacent gene transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 19:2695-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayer, C. L., S. G. Filler, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 1992. Candida albicans adherence to endothelial cells. Microvasc. Res. 43:218-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer, J. E., J. Harder, T. Gorogh, J. B. Weise, S. Schubert, D. Janssen, and S. Maune. 2004. Human beta-defensin-2 in oral cancer with opportunistic Candida infection. Anticancer Res. 24:1025-1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montes, L. F., and W. H. Wilborn. 1968. Ultrastructural features of host-parasite relationship in oral candidiasis. J. Bacteriol. 96:1349-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murad, A. M., P. Leng, M. Straffon, J. Wishart, S. Macaskill, D. MacCallum, N. Schnell, D. Talibi, D. Marechal, F. Tekaia, C. d'Enfert, C. Gaillardin, F. C. Odds, and A. J. Brown. 2001. NRG1 represses yeast-hypha morphogenesis and hypha-specific gene expression in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 20:4742-4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nobile, C. J., V. M. Bruno, M. L. Richard, D. A. Davis, and A. P. Mitchell. 2003. Genetic control of chlamydospore formation in Candida albicans. Microbiology 149:3629-3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nobile, C. J., N. Solis, C. L. Myers, A. J. Fay, J. S. Deneault, A. Nantel, A. P. Mitchell, and S. G. Filler. 2008. Candida albicans transcription factor Rim101 mediates pathogenic interactions through cell wall functions. Cell. Microbiol. 10:2180-2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norice, C. T., F. J. Smith, Jr., N. Solis, S. G. Filler, and A. P. Mitchell. 2007. Requirement for Candida albicans Sun41 in biofilm formation and virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 6:2046-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palmer, G. E., A. Cashmore, and J. Sturtevant. 2003. Candida albicans VPS11 is required for vacuole biogenesis and germ tube formation. Eukaryot. Cell 2:411-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paraje, M. G., S. G. Correa, M. S. Renna, M. Theumer, and C. E. Sotomayor. 2008. Candida albicans-secreted lipase induces injury and steatosis in immune and parenchymal cells. Can. J. Microbiol. 54:647-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park, H., C. L. Myers, D. C. Sheppard, Q. T. Phan, A. A. Sanchez, J. E. Edwards, Jr., and S. G. Filler. 2005. Role of the fungal Ras-protein kinase A pathway in governing epithelial cell interactions during oropharyngeal candidiasis. Cell. Microbiol. 7:499-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phan, Q. T., P. H. Belanger, and S. G. Filler. 2000. Role of hyphal formation in interactions of Candida albicans with endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 68:3485-3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phan, Q. T., R. A. Fratti, N. V. Prasadarao, J. E. Edwards, Jr., and S. G. Filler. 2005. N-cadherin mediates endocytosis of Candida albicans by endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280:10455-10461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phan, Q. T., C. L. Myers, Y. Fu, D. C. Sheppard, M. R. Yeaman, W. H. Welch, A. S. Ibrahim, J. E. Edwards, and S. G. Filler. 2007. Als3 is a Candida albicans invasin that binds to cadherins and induces endocytosis by host cells. PLoS Biol. 5:e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rangel-Frausto, M. S., T. Wiblin, H. M. Blumberg, L. Saiman, J. Patterson, M. Rinaldi, M. Pfaller, J. E. Edwards, Jr., W. Jarvis, J. Dawson, and R. P. Wenzel. 1999. National epidemiology of mycoses survey (NEMIS): variations in rates of bloodstream infections due to Candida species in seven surgical intensive care units and six neonatal intensive care units. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Redding, S. W., R. C. Zellars, W. R. Kirkpatrick, R. K. McAtee, M. A. Caceres, A. W. Fothergill, J. L. Lopez-Ribot, C. W. Bailey, M. G. Rinaldi, and T. F. Patterson. 1999. Epidemiology of oropharyngeal Candida colonization and infection in patients receiving radiation for head and neck cancer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3896-3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reggiori, F., C. W. Wang, P. E. Stromhaug, T. Shintani, and D. J. Klionsky. 2003. Vps51 is part of the yeast Vps fifty-three tethering complex essential for retrograde traffic from the early endosome and Cvt vesicle completion. J. Biol. Chem. 278:5009-5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Revankar, S. G., O. P. Dib, W. R. Kirkpatrick, R. K. McAtee, A. W. Fothergill, M. G. Rinaldi, S. W. Redding, and T. F. Patterson. 1998. Clinical evaluation and microbiology of oropharyngeal infection due to fluconazole-resistant Candida in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:960-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rhodus, N. L., C. Bloomquist, W. Liljemark, and J. Bereuter. 1997. Prevalence, density, and manifestations of oral Candida albicans in patients with Sjogren's syndrome. J. Otolaryngol. 26:300-305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson, L. C., C. Bradley, J. D. Bryan, A. Jerome, Y. Kweon, and H. R. Panek. 1999. The Yck2 yeast casein kinase 1 isoform shows cell cycle-specific localization to sites of polarized growth and is required for proper septin organization. Mol. Biol. Cell 10:1077-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rotrosen, D., J. E. Edwards, Jr., T. R. Gibson, J. C. Moore, A. H. Cohen, and I. Green. 1985. Adherence of Candida to cultured vascular endothelial cells: mechanisms of attachment and endothelial cell penetration. J. Infect. Dis. 152:1264-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rubin-Bejerano, I., I. Fraser, P. Grisafi, and G. R. Fink. 2003. Phagocytosis by neutrophils induces an amino acid deprivation response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:11007-11012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sanchez, A. A., D. A. Johnston, C. Myers, J. E. Edwards, Jr., A. P. Mitchell, and S. G. Filler. 2004. Relationship between Candida albicans virulence during experimental hematogenously disseminated infection and endothelial cell damage in vitro. Infect. Immun. 72:598-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sandovsky-Losica, H., N. Chauhan, R. Calderone, and E. Segal. 2006. Gene transcription studies of Candida albicans following infection of HEp2 epithelial cells. Med. Mycol. 44:329-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sangeorzan, J. A., S. F. Bradley, X. He, L. T. Zarins, G. L. Ridenour, R. N. Tiballi, and C. A. Kauffman. 1994. Epidemiology of oral candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: colonization, infection, treatment, and emergence of fluconazole resistance. Am. J. Med. 97:339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saville, S. P., A. L. Lazzell, C. Monteagudo, and J. L. Lopez-Ribot. 2003. Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1053-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]