Abstract

Summary: Francisella tularensis is a facultative intracellular gram-negative pathogen and the etiological agent of the zoonotic disease tularemia. Recent advances in the field of Francisella genetics have led to a rapid increase in both the generation and subsequent characterization of mutant strains exhibiting altered growth and/or virulence characteristics within various model systems of infection. In this review, we summarize the major properties of several Francisella species, including F. tularensis and F. novicida, and provide an up-to-date synopsis of the genes necessary for pathogenesis by these organisms and the determinants that are currently being targeted for vaccine development.

INTRODUCTION

Francisella tularensis is a gram-negative coccobacillus that has an exceedingly low infectious dose. It is a category A select agent and is one of the most infectious bacteria known. Following the terrorist attacks of 2001 and subsequent anthrax mailings in the fall of that year, there has been a renewed interest in the study of this organism. Advancements in the field of F. tularensis genetics have lead to a dramatic expansion in the generation of mutant strains of various F. tularensis subspecies. Collectively, this has led to an improved understanding of F. tularensis biology, host responses to infection, and virulence factors required for infection and/or disease elicitation. Many investigators in this field have focused on the development of a vaccine capable of protecting against the most virulent biovars of F. tularensis. Of particular interest are those providing substantive protection against type A strains delivered by the respiratory route. Here, we review the major characteristics of F. tularensis and provide an update regarding genes required for pathogenesis and determinants being targeted for vaccine development.

FRANCISELLA TULARENSIS AND TULAREMIA

Classification

Francisella tularensis is one of the most infectious and pathogenic bacteria known. It is the etiological agent of the debilitating febrile illness tularemia. The bacterium is a gram-negative, capsulated, facultative intracellular pathogen and is one of the members of the genus Francisella of the Gammaproteobacteria class. Francisella has no close pathogenic relatives but exists in a sister clade with the arthropod endosymbiont Wolbachia persica. It is also distantly related to human pathogens Coxiella burnetii and Legionella pneumophila (109). F. tularensis is commonly classified into three subspecies, F. tularensis subsp. tularensis, F. tularensis subsp. holarctica, and F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica, based on genetic makeup, virulence, ability to produce acid from glycerol, and citrulline ureidase activity (49) (Table 1). Francisella novicida is also often considered a subspecies of F. tularensis; however, recent whole-genome single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis indicates that it is likely an independent species (104). F. tularensis subsp. tularensis and F. tularensis subsp. holarctica are the primary biovars associated with disease in humans. F. tularensis subsp. tularensis, also known as type A Francisella, is found primarily in North America and is highly virulent in humans. This subspecies is responsible for roughly 70% of Francisella disease cases in North America (186). Type A strains have an infectious dose of <10 CFU in humans (174, 175) and can lead to life-threatening illness, particularly when infection occurs via the respiratory route. Molecular subtyping techniques indicate that F. tularensis subsp. tularensis can be further divided into two genetically distinct clades (A.I and A.II) that differ with respect to disease outcome, transmission, and geographic location (59, 98, 104, 187, 194). F. tularensis subsp. holarctica, or type B strains, is found throughout much of the Northern Hemisphere and is the primary cause of tularemia in Europe (141). These organisms have an infectious dose of <103 CFU and cause a milder form of tularemia in humans. The live vaccine strain (LVS) that was developed in the former Soviet Union and gifted to the United States in the 1950s is a human-attenuated type B derivative. F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica and F. novicida are focally distributed and are rarely associated with disease in humans. F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica is primarily isolated to central Asian regions of the former USSR, while F. novicida is found in North America and Australia (57, 141, 147). F. novicida has been extensively studied as a model organism in the laboratory setting due to its enhanced genetic tractability relative to other subspecies and its relative avirulence in humans. All F. tularensis subspecies are highly pathogenic in animal models, particularly in rabbits and mice. F. novicida is also highly pathogenic in mice, but its virulence remains less characterized outside this model system.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Francisella speciesa

| Species or subspecies | LD50 (CFU) in: |

Straind | Accession no. | Length (bp) | No. of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miceb | Humansc | Genes | Pseudogenese | ||||

| F. tularensis subsp. tularensis | <10 | <10 | Schu S4 | NC 006570 | 1,892,819 | 1,852 | 201 |

| FSC198 | NC 008245 | 1,892,616 | 1,852 | 199 | |||

| WY96-3418 | NC 009257 | 1,898,476 | 1,872 | 0 | |||

| F. tularensis subsp. holarctica | <10 | <103 | LVS | NC 007880 | 1,895,994 | 2,020 | 213 |

| OSU18 | NC 008369 | 1,895,727 | 1,932 | 328 | |||

| FTNF002-00 | NC 009749 | 1,890,909 | 1,887 | 2 | |||

| F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica | NRf | NR | FSC147 | NC 010677 | 1,893,886 | 1,750 | 297 |

| F. novicida | <10 | >103 | U112 | NC 008601 | 1,910,031 | 1,781 | 14 |

Adapted from Table 1 in reference 140 with kind permission from Springer Science + Business Media (© Springer 2005) and from reference 203 with kind permission of Wiley-Blackwell.

Doses delivered subcutaneously.

Estimated LD based on virulence in animal models and case studies.

Several additional Francisella isolates are currently being sequenced, including F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (strains MA00-2987 [NZ ABRI00000000] and FSC033 [NZ AAYE00000000]), F. tularensis subsp. holarctica (strains FSC200 [NZ AASP00000000], FSC022 [NZ AAYD00000000], and 257 [NZ AAUD00000000], and F. novicida (strains FTG [NZ ABXZ00000000], FTE [NZABSS00000000], GA99-3548 [NZ ABAH00000000], and GA99-3549 [NZ AAYF00000000]).

Refers to sequences resembling functional genes but thought to have lost protein-coding capability.

NR, doses have not been reported.

Comparative Genomics

There are currently eight completely sequenced Francisella genomes (Table 1) and an additional nine genomes for which shotgun sequencing is currently under way. Sequence analysis of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (FSC198 [NC 008245], Schu S4 [NC 006570], and WY96-3418 [NC 009257]), F. tularensis subsp. holarctica (FTNF002-00 [NC 009749], OSU18 [NC 008369], and LVS [NC 067880]), F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica (FSC147 [NC 010677]), and F. novicida (U112 [NC 008601]) indicates that these strains are highly similar at the genetic level. The genome of each strain is roughly 1.8 Mb, with F. novicida U112 having the largest genome at 1.91 Mb. All genomes have a G+C content of approximately 32%, with between 1,800 and 2,000 putative coding sequences depending on the subspecies and strain. Between 70 and 90% of open reading frames within these isolates are predicted to code for functional proteins. Interestingly, the more virulent subspecies, F. tularensis subsp. tularensis and F. tularensis subsp. holarctica, contain roughly 200 to 300 pseudogenes, depending on the strain, while the less pathogenic F. novicida U112 contains only 14 pseudogenes (109, 203). Additionally, nearly 30% of annotated genes within an F. tularensis isolate are characterized as hypothetical proteins with unknown function, suggesting that Francisella is likely to encode novel virulence determinants. A 30-kb region with low G+C content (27.5%) that is unique to Francisella among the 17 gammaproteobacterial genomes exists in duplicate in type A and B strains of F. tularensis but is present in single copy in F. novicida. This locus has been identified as a pathogenicity island and is required for aspects of F. tularensis survival within host cells.

Comparative genomic studies have indicated that there is a high level of nucleotide identity between and within F. tularensis subspecies, ranging from roughly 97% to 99%. Despite this, there are numerous DNA rearrangements present between subspecies, particularly between type A and type B strains, and among different type A strains (148). These rearranged sequences are flanked by repeated DNA insertion sequence elements, indicating that they likely evolved from homologous recombination events. In contrast, little genomic reorganization is observed in type B strains. Though the precise impact of these rearrangements remains unclear, it is of note that they exist primarily in the more virulent type A strains.

Comparisons of deletion events, repeat sequences, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms between sequenced Francisella genomes have provided important insights into the evolution of these organisms. The presence of conserved genomic deletion events and single-nucleotide variations in F. tularensis and F. novicida isolates suggest that these species have evolved vertically, with F. novicida being the most ancestral. Additionally, the highly virulent type A strains appeared before the less virulent type B strains (59). The reduced genomic heterogeneity of type B strains compared with type A strains and the recovery of type B strains from around the world indicate that F. tularensis subsp. holarctica has evolved recently and spread rapidly (59). The evolution of F. tularensis from a common ancestor appears to have resulted from both a loss and a gain of genetic information over time, as type A strains have undergone a reduction in their genomic content relative to F. novicida, but type B strains contain additional genomic content that is otherwise absent from their type A counterparts. These observations indicate either that rearrangements occurred in type A Francisella after type A and B strains diverged evolutionarily or that type B strains were derived from one type A strain that lost the ability to undergo such rearrangements (148).

Epidemiology of F. tularensis

Though its primary environmental niche remains unknown, F. tularensis has a broad and complex host distribution, infecting a number of wildlife species, including lagomorphs, rodents, insectivores, carnivores, ungulates, marsupials, birds, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates (14, 18, 136, 196). F. tularensis is most frequently found in rodents, hares, and rabbits; however, these are unlikely reservoirs for F. tularensis, considering that infection often leads to acute disease in these animals. It has also been suggested that protozoa may play a role as hosts in aquatic cycles, which is supported by the demonstration of F. tularensis in amoebal cysts (2, 111, 141, 202). Finally, although most arthropod vectors serve only as transient hosts, F. tularensis may be transmitted by ticks throughout their life cycle, raising the possibility that a single tick may infect multiple hosts (90, 149).

A primary route of F. tularensis transmission to humans and other animals is through arthropod vectors such as ticks, biting flies, and possibly mosquitoes. Infection by F. tularensis can also occur through direct contact with contaminated water, food supplies, or infected animals (49). F. tularensis is occasionally acquired by inhalation of organisms that have been aerosolized through disruption of contaminated materials. For these reasons, high-risk groups include hunters or trappers, who might come into contact with infected animals, and landscapers, who may encounter aerosolized organisms through mechanical disruption of contaminated soil or animal carcasses. Though F. tularensis organisms are readily aerosolized, transmission via human-to-human contact has yet to be reported.

F. tularensis-mediated disease was first recognized as a plague-like illness in rodents during an outbreak in Tulare County, CA, in 1911, resulting in the first isolation of the bacterium (70). Three years later, human disease caused by F. tularensis in two patients in Ohio who had recent contact with wild rabbits was described (215). In 1919, Edward Francis established that a number of clinical symptoms were specifically caused by “Bacterium tularense,” named for the county in which the disease was found to be endemic, and the name “tularemia” was subsequently used to describe them (68, 70). Tularemia has been referred to as “rabbit fever,” “market men's disease,” and “meat-cutter's disease,” all named for the frequent incidence of disease associated with dressing rabbits for meat. The terms “deer-fly fever” and “glandular type of tick fever” have also been used to describe tularemia in the context of symptoms arising from a tick or fly bite resulting in a noted enlargement of lymph nodes. Identification of symptoms and potential sources led to the subsequent accumulation of tularemia reports in the United States, with roughly 14,000 cases reported by 1945 (96) and a peak incidence of 2,291 cases in 1939 (60, 183). Concurrently, reports of a similar disease were emerging from Japan and Russia. Large waterborne outbreaks in the 1930s and 1940s further solidified the epidemic potential of this organism and prompted further investigation into the characteristics of F. tularensis. The largest recorded tularemia outbreak occurred via airborne transmission of the European biovar F. tularensis subsp. holarctica and involved more than 600 individuals between 1966 and 1967 in a farming area of Sweden (45). In this case, most individuals acquired tularemia while doing farm work that created aerosols, such as sorting hay.

Today, the worldwide occurrence of human tularemia is likely underestimated and underreported due to the generic nature of the disease symptoms. It is well established that natural tularemia outbreaks are typically highly localized, with areas of endemicity often encompassing only a few hundred square kilometers. Outbreaks of tularemia often occur in parallel with outbreaks in rodents, hares, rabbits, and other small mammals (196). Tularemia is known to be dispersed throughout much of the Northern Hemisphere, particularly in parts of North America, Europe, and northern Asia (57, 91). There have been reports of human tularemia in every state in the United States except Hawaii, with a localization of most cases to south-central and western states (18, 24a, 48). Overall, reported cases of tularemia have dropped from several thousand per year prior to 1950 to fewer than 200 in the 1990s (18, 24a, 48). Cases are typically sporadic or occur in small clusters during June through September, correlating with the incidence of arthropod-borne transmission (18, 48, 58). A summary of a number of tularemia reports during the 1980s in the United States revealed that 63% of infected individuals reported an attached tick, and 23% reported contact with wild rabbits (197). The most recent major incident involving F. tularensis in the United States occurred on Martha's Vineyard in 2000 and involved 15 patients with one fatality; 11 of the patients had acquired pneumonic tularemia (61). Many of those infected were landscapers, and it is speculated that lawn mowing or brush cutting was a major risk factor (61). Though less numerous, reports of tularemia continue to arise from Martha's Vineyard annually, with landscapers representing a majority of the infected. Most tularemia reports in Europe are from the northern and central countries, particularly Scandinavian countries (196). Disease in many of these countries occurs in an uneven geographical distribution, with high percentages of reports coming from localized rural regions. Furthermore, a strain similar to Francisella novicida was recently isolated from a patient in Australia, indicating that the geographic distribution of Francisella is likely more widespread than previously reported (216).

Tularemia

Tularemia is an acute febrile illness, the type and severity of which depend on the route of infection and the infecting biovar. F. tularensis can infect humans through the skin, mucous membranes, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory tract. Major target organs include the lymph nodes, lungs, spleen, liver, and kidneys (58, 69, 116, 154, 190). Infection acquired through the skin or mucous membranes results in ulceroglandular tularemia, which comprises up to 90% of all cases (195). Ulceroglandular tularemia results from direct contact of the organism with the skin, often while handling infected animals or animal tissues or as a result of vector-borne transmission. A primary ulcer develops at the infection site, followed by painful swelling of the nearby lymph nodes. After an incubation period that can last up to 21 days, there is a rapid onset of high fever accompanied by flu-like symptoms. F. tularensis may further disseminate to and replicate in other organs in the body, particularly the lungs, liver, and spleen. Ulceroglandular tularemia has a mortality rate of less than 5% (58), though dissemination and replication within the lung may lead to a more serious respiratory disease. Inhalation of live organisms or accumulation of organisms in the lung following dissemination from other infection routes often leads to respiratory tularemia, the most severe form of the disease. Outbreaks resulting from respiratory transmission are rare but can involve a large number of cases, depending on the mechanism of dispersion. Symptoms for respiratory tularemia can be somewhat variable. While inhalation of F. tularensis subsp. holarctica results in a mild and generally non-life-threatening respiratory infection, inhalation of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis results in an acute, serious infection that presents with a high fever, chills, malaise, and cough. Organisms deposited into the lung readily spread to the draining lymph nodes and further disseminate to the liver and spleen, where severe inflammation and tissue damage can occur. Tularemia resulting from respiratory infection of type A Francisella has mortality rates approaching 30% to 60% if untreated (50, 174, 175). However, the fatality rate is reduced to less than 2% when antibiotics are administered in a timely fashion (58). Other, less common forms of the disease include oculoglandular tularemia, which results from direct contact of organisms with the eye, accounting for 1% to 4% of all cases (141). Ingestion of food or water contaminated with F. tularensis may also cause oropharyngeal and/or gastrointestinal tularemia, which is the least common form of the disease. Typhoidal tularemia is a term used to describe infection with severe systemic symptoms without regional ulcerations or swollen lymph nodes indicative of a site of inoculation (49). Though less common, these additional disease forms highlight the ability of Francisella to infect humans via multiple routes.

Potential as a Biological Weapon

F. tularensis has long been considered a potential biological weapon based on its ability to cause severe disease upon inhalation of doses as low as 10 CFU (174). The biological weapons programs in several countries, including Japan, the former Soviet Union, and the United States, developed weapons containing F. tularensis (49, 87). In the 1960s, F. tularensis was one of a number of agents stockpiled by the United States military as part of a biological weapons development program that was eventually terminated by executive order in 1970 (30). Despite efforts to disengage biological weapons programs around the world, former Soviet Union biological weapons senior scientist Ken Alibeck reported that weaponization efforts occurred in the Soviet Union well into the 1990s (3). In light of recent world events, the extreme infectivity and the ability to potentially disseminate aerosolized organisms over an urban area continue to drive concerns regarding Francisella weaponization and/or intentional release. In 1969, a report from a World Health Organization committee assessed the bioweapon threat of F. tularensis. It estimated that an aerosol release of 50 kg of F. tularensis over an urban area with a population of nearly 5 million individuals would result in 250,000 incapacitating casualties and 19,000 deaths (220a). More recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that the total base costs to society resulting from such an attack would approach $5.4 billion for every 100,000 persons exposed (102). In the event of an intentional release of F. tularensis, it is likely that prompt treatment of at-risk individuals would dramatically reduce the impact of the event.

F. TULARENSIS PATHOGENESIS

The success of Francisella as a pathogen is intimately associated with its ability to survive and replicate within a wide variety of host cell types. Upon entering a mammalian host, Francisella is known to target macrophages. However, it has become increasingly clear that these organisms can infect and survive in a number of additional cell types, including dendritic cells, neutrophils, hepatocytes, and lung epithelial cells. While the importance of these cell types to infection is not completely understood, it is well documented that Francisella replicates within mononuclear phagocytes in vivo and exhibits a disease cycle within these cells that appears to differ little between strains or subspecies.

Intracellular Life Cycle of F. tularensis in Phagocytic Cells

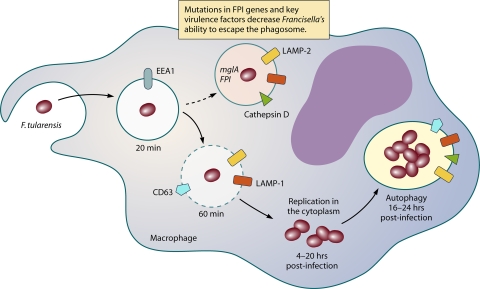

Francisella enters cells through the process of phagocytosis. It has been reported that F. tularensis may utilize an unusual mechanism involving the formation of spacious asymmetric pseudopod loops. This process, termed “looping phagocytosis” (33), involves actin rearrangement through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling and is strongly dependent on the presence of complement factor C3 and complement receptor CR3 (32, 33). Francisella may also enter cells via the mannose receptor, type I and II class A scavenge receptors, and the Fcγ receptor (11, 151, 178). Following internalization into host cells, F. tularensis is able to alter normal bactericidal processes. It prevents induction of the respiratory burst (66), limiting its exposure to superoxide or other reactive oxygen by-products. It alters phagosome maturation and as a result only transiently interacts with components of the endocytic trafficking network (Fig. 1). The organism initially resides in a membrane-bound compartment that acquires limited amounts of early endosomal and late endosomal-lysosomal markers, including EEA1, CD63, LAMP1, and LAMP2 (35). The F. tularensis-containing vacuole (FCV) fails to acquire the acid hydrolase cathepsin D and does not fuse with lysosomes (35). In addition, F. tularensis alters host cell trafficking by escaping from the phagosome and entering the host cell cytosol, where it undergoes extensive replication (27, 35, 82, 173). While the relative timing of these events appears to differ between the various Francisella species and the host cell types infected (27, 35, 82, 173), mutants that fail to prevent fusion with the lysosome and/or are unable to escape from the phagosome are highly attenuated in virulence in vitro and in vivo (19, 117, 133, 135).

FIG. 1.

Illustration of Francisella survival inside macrophages. Francisella is taken up by macrophages through looping phagocytosis (33) into an endosomal compartment that transiently acquires late endosome-associated markers (29, 32). Francisella then exits the phagosomal compartment and replicates to high numbers in the cellular cytosol. Prior to lysis of the cell, Francisella has been shown to reside in an autophagy-like compartment (27).

There are conflicting reports regarding the extent to which the FCV acidifies as it transiently interacts with components of the endocytic pathway. It also remains controversial whether exposure to acidic pH is necessary and/or sufficient for F. tularensis egress from the phagosome. Studies conducted by Clemens et al. using THP1 cells (a human macrophage-like cell line) or primary macrophages derived from peripheral blood monocytes have demonstrated that FCVs harboring LVS or type A F. tularensis become only minimally acidified (pH of 6.7) and acquire limited amounts of the proton vacuolar ATPase (34, 35). Additionally, use of the proton pump inhibitor bafilomycin A prior to infection of these macrophage types with F. tularensis strains does not alter the efficiency of F. tularensis phagosomal escape (34). In contrast, studies published by Santic et al. and Chong et al. have reported significant levels of FCV acidification and vacuolar ATPase acquisition in primary human and murine macrophages infected with F. tularensis Schu S4, LVS, and F. novicida (29, 173). Treatment of these macrophages with bafilomycin A prior to infection significantly reduced the efficiency with which these F. tularensis derivatives were able to escape from the phagosome (29, 173).

Phagosomal escape requires viable F. tularensis and occurs via an unknown mechanism that involves degradation of the surrounding lipid bilayers (27, 34, 35, 78, 173). At roughly 12 h postinfection, Francisella begins to replicate to high numbers within the host cell cyotosol, eventually leading to cell death, egress of Francisella, and presumably infection of nearby cells. Escape of F. tularensis from the phagosome and replication within the host cell cytosol is dependent on genes present in the Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI) (29, 78, 83, 110, 117, 138, 171, 173, 176). Francisella has also been shown to reside in vesicles similar to autolysosomes at ≥24 h postinfection, prior to host cell death, indicating that Francisella may reenter the endocytic pathway through host cell autophagy (27). The significance of this process for either Francisella infection or the immune response to infection remains unclear. Francisella may also exhibit an extracellular phase, as both LVS and Schu S4 have been found in the plasma following infection of mice via various inoculation routes (63). Whether this observation correlates to humans or plays a significant role in the ability of the organism to cause disease awaits further investigation.

IMMUNITY AND HOST RESPONSE TO INFECTION

Successful development of a Francisella vaccine will ultimately rely on a comprehensive understanding of the host immune response to infection. Many of the details regarding the host response to F. tularensis infection have come from studies using the less virulent F. novicida or the F. tularensis subsp. holarctica LVS, both of which are thought to differ from the more virulent type A strains in certain aspects of infection. Studies carried out with various murine infection models have shown that low doses of the attenuated LVS strain can be cleared by innate host defense mechanisms, while the fully virulent type A and B strains are able to rapidly kill mice prior to generation of a cell-mediated immune response. The precise mechanisms by which virulent strains avoid and overcome murine immune responses remain unknown. Differences in the host response to these subspecies and the route of infection highlight the complexities of this issue and suggest that the correlates of immunity need to be evaluated for each potential infection scenario.

Innate Immunity

The innate immune responses to F. tularensis infection share much in common with the responses seen with other intracellular pathogens. Francisella infection results in an early pronounced inflammatory response, with initial induction of proinflammatory and Th1-type cytokines, including interleukin-12, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (38, 81, 189, 217). Tumor necrosis factor alpha and IFN-γ are essential for control of infection, as depletion of either converts typically sublethal infections into lethal ones (55, 56, 112). Macrophages, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) cells are likely responsible for the cytokine induction seen almost immediately postinfection (17, 118). Activation of proinflammatory cytokines in murine macrophages occurs in a Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)-dependent manner, indicating that TLR2-mediated signaling may be crucial for early pathogen recognition (37). IFN-γ activation of macrophages and other professional phagocytes is also particularly important for initial containment of Francisella, as these cells are a primary target of the organism for infection and replication. In addition to macrophages, neutrophils have been shown to be important in the initial control of infection, but their importance may differ with respect to the different tissues infected. In mouse infection models, depletion of neutrophils increases sensitivity to systemic infection but has little effect on respiratory infection with Francisella (41, 56, 184).

There is evidence that Francisella evades and modulates the host immune response beyond its ability to inhibit maturation of the host phagosome and escape lysosomal degradation. Francisella diminishes the capacity of macrophages to respond to engagement of TLRs with secondary stimuli such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (198). Similar effects have also been demonstrated in dendritic cells (81). A recent report by Bosio et al. has indicated that when delivered via the respiratory route, the type A strain Schu S4 actively suppresses early inflammatory responses in the lung (16). In particular, Schu S4 fails to activate pulmonary macrophages and dendritic cells and actively interferes with induction of proinflammatory cytokines, in part through the induction of transforming growth factor β (16). In addition, Woolard et al. have recently demonstrated that Francisella infection of bone marrow-derived macrophages results in secretion of prostaglandin E2, which inhibits interleukin-2 production and promotes a Th2-type response, a T-cell response that is ineffective against the clearing of intracellular organisms (220). This increase in prostaglandin E2 has also been confirmed in the lung in vivo (219). Finally, Francisella has been shown to infect and replicate within neutrophils and inhibit the respiratory burst, thus evading neutrophil killing mechanisms (127, 179). Though the precise contributions of these findings to infection remain unclear, it is likely that immune evasion and/or suppression is essential to the highly virulent nature of Francisella and differences between subspecies.

Adaptive Immunity

Exposure to sublethal concentrations of Francisella induces strong protective immunity against secondary exposure in humans and in experimental animal models (51, 188). Though specific antibodies are readily detectable in sera upon F. tularensis infection, their importance to immunity remains unclear. Passive antibody transfer studies carried out in animals suggest that antibodies may play a role in combating infection with lower-virulence strains while playing a lesser role against the more virulent subspecies (51, 54, 188). Although Francisella antibodies may prove beneficial in some situations, they are likely not essential. Rather, they must be coupled with an effective cellular immune response to fully control infection. Adaptive immunity to F. tularensis infection is largely dependent on T-cell-mediated immunity, particularly that mediated by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (56). In mice, either CD4+ or CD8+ cells are able to control infection by F. novicida or LVS, while both cell types seem to be required for successful defense against the highly virulent type A strains (43, 74, 222). Similar to the case for mice, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses are prominent in humans vaccinated with LVS (107, 192). The T-cell effector functions are likely very closely linked to the ability to activate macrophage intracellular killing mechanisms. Despite the known requirement of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for resolving F. tularensis infection, little is known regarding the T-cell receptors, coreceptors, memory profiles, or major histocompatibility complex restriction of T-cell responses to infection.

Immunity to Infection by Different Routes

An effective vaccine against F. tularensis will require generation of an immune response that is protective against pulmonary infection. However, much of the work examining and characterizing the immune responses to Francisella infection have involved infection by the systemic route. Though there are many general consistencies, correlates of immunity to F. tularensis infection differ in certain aspects depending on the route of infection. A number of recent reports highlight potentially key differences in the host immune response to respiratory versus systemic infection (41). In addition to the diminished role of neutrophils and reactive nitrogen species, there exists disparity in the timing of initial host inflammation when comparing respiratory versus systemic infection. During murine infection initiated via the intradermal or subcutaneous route, there is an immediate onset of inflammation within the first 2 days postinfection that includes the rapid induction of IFN-γ (36, 54). During respiratory infection this response is delayed, not occurring until 3 to 5 days postinfection. By this time, significant bacterial burdens have begun to accumulate in the livers and spleens of infected mice, and it has been speculated that systemic disease contributes to the morbidity observed in these animals (40). The delay in inflammation onset is consistent with what has been seen in human disease (6). The precise reasons for this delay remain unclear, but it may play a contributing factor in the general difficulty in vaccinating against respiratory forms of the disease. Other recent reports also highlight potential differences in T-cell responses between respiratory and systemic infection. Woolard et al. have demonstrated that intranasal infection of mice produces much lower levels of IFN-γ-secreting T cells than systemic infection (219). Furthermore, intranasal inoculation results in a delayed accumulation of T cells in the spleen and lung, along with a significant increase in the amounts of prostaglandin E2. Collectively, these observations suggest that virulent F. tularensis subspecies alter T-cell responses to the detriment of the host (220).

Though our understanding of Francisella host/pathogen interactions is advancing, there is still a great deal that remains unclear. Of particular interest, the host immune response to infection by highly virulent type A strains has only now been investigated in any great detail. Further evaluation of the host immune response to infection, as well as identification of key Francisella virulence mediators, will be necessary to gain a more complete understanding of the interplay between Francisella and the host immune system, particularly for the development of novel prophylactic treatments.

FRANCISELLA GENETICS AND VIRULENCE FACTORS

The ability to effectively colonize or parasitize a diverse array of hosts suggests that F. tularensis is capable of adapting to a wide variety of growth environments. Despite its extreme virulence and fairly well-characterized intracellular life cycle, very little is known about the mechanisms of F. tularensis pathogenesis or the virulence factors encoded by this organism. Initial assessments of the completed genomic sequences from different F. tularensis subspecies have indicated that F. tularensis does not encode any toxins or secretion systems that are commonly present in other intracellular pathogens. In addition, F. tularensis does not encode homologs of genes that mediate phagosomal escape in other organisms, such as Listeria and Shigella. Due in large part to an increase in the development and efficiency of genetic tools, recent studies have begun to shed light on the specific virulence genes necessary for successful infection by F. tularensis.

Genetic Tools

Shuttle and integration vectors.

The field of Francisella genetics has undergone an extensive expansion over the past 10 years (71). Until recently, few vectors or selectable markers were amenable for use in Francisella, and the available methods for introducing DNA were generally inefficient. In 1994, identification of a 3,990-bp cryptic plasmid (pFNL10) from an F. novicida-like strain designated F6168 helped to usher in the first generation of useful genetic vectors for this organism (144). pFNL10 could be introduced by standard procedures and maintained in various subspecies of F. tularensis, although it was not capable of replicating in Escherichia coli and lacked any antibiotic resistance markers (144). Further modifications to pFNL10 led to the construction of second-generation vectors that carried replication origins for E. coli and selectable antibiotic resistance markers. pFNL100 included sequences from both pFNL10 and cloning vector pBR328 (143). pFNL200 was a deletion derivative of pFNL100 and expressed tetracycline and chloramphenicol resistance; however, it suffered from stability issues (143). pKK202 was a more stable derivative of pFNL200 that carried the p15A origin of replication from E. coli (139). Finally, the generation of pKK214 and its variants expanded the utility of pKK202 by incorporating a promoterless chloramphenicol acetyltransferase or green fluorescent protein reporter gene in place of the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene (2, 108).

More recently, Maier et al. have constructed a series of E. coli-Francisella shuttle vectors, termed pFNLTP, that are hybrids between pFNL10 and cloning vector pCR2.1-TOPO (125). These vectors can be efficiently transformed into F. tularensis subspecies by electroporation, are stably maintained even in the absence of antibiotic selection, and do not alter virulence characteristics of F. tularensis in vitro or in vivo (124, 125, 145, 146). A variety of pFNLTP1 variants have been generated, and these include derivatives that carry antibiotic resistance elements amenable for use in type A strains of F. tularensis, multiple cloning sites, reporter genes and counterselectable markers, and temperature-sensitive origins of replication (93, 125). In addition to their use as complementation and reporter gene platforms, pFNLTP1-based vectors (or vectors that have been derived from them) have been used as delivery vehicles to carry out transposon mutagenesis, targeted allelic exchange, and promoter-trap library construction (22, 125, 128).

LoVullo et al. have recently developed a series of shuttle vectors, pMP, that are based on the minimal regions of pFNL10 required for replication and regions from E. coli-mycobacterial shuttle vector pMV261 carrying the aphA1 antibiotic resistance determinant and ColE1 replication origin (121). While the original plasmid, pMP393, could be efficiently introduced by electroporation and was stable in various F. tularensis subspecies, it was frequently lost in the absence of selection (121). Second-generation variants of pMP393 have corrected maintenance issues and expanded the choice and utility of antibiotic resistance determinants for selection within F. tularensis (120). Third-generation pMP-based vectors have also been developed, in which stability has been further enhanced, useful multiple cloning sites introduced, and heterologous promoters added for gene expression studies (120). Finally, a single-copy chromosomal integration system for Francisella has been developed by that group (119). Vectors designed for this system include plasmids allowing integration at the attachment site for the Tn7 transposon (located downstream of the glmS gene) or within the blaB gene, encoding resistance to the antibiotic ampicillin (119). Development of an integration system for F. tularensis represents a major advancement for the field, as it alleviates some of the previous issues inherent with use of multicopy shuttle vectors, including lack of stability, use of heterologous antibiotic resistance determinants, and multicopy expression artifacts.

Gene disruption vectors.

Much of the lack of understanding of Francisella virulence can be directly attributed to the difficulty in generating defined genetic lesions within this family. While genetic tools and methodologies have been available for some time to disrupt genes in F. novicida, construction of mutant derivatives in the type A or B genetic background was not reported until 2004 (82). Gene disruptions in F. novicida have been generated using a variety of approaches, including allelic exchange of linear substrates (Table 2) (110). Initial efforts to disrupt genes in type A or type B strains were based largely on utilization of pUC19-derived suicide vectors (82). Optimization of these vectors, along with the development of additional vectors, has allowed the list of Francisella mutants to expand significantly (Tables 3 and 4). This list includes mutants that are defective for putative virulence factors as well as metabolic genes that may be utilized for the construction of live attenuated vaccine candidates. More recently, the TargeTron group II intron mutagenesis system has been adapted for use with various F. tularensis subspecies (162, 163). This system has proven efficient, and it is advantageous as it allows simultaneous disruption of genes that are present in more than one copy (162, 163).

TABLE 2.

F. novicida genes involved in pathogenesis

| Locus tag | Name | Function | Method(s)a | Cells/animals in which mutant strain is attenuatedb | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTN_0008 | FTN_0008 | Ten-transmembrane-spanning drug/metabolite exporter protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0012 | FTN_0012 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0019 | pyrB | Aspartate carbamoyltransferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0020 | carB | Carbamoylphosphate synthase large chain | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199, 213 |

| FTN_0021 | carA | Carbamoylphosphate synthase small chain | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0023 | tmpT | Thiopurine S-methyltransferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0028 | FTN_0028 | Conserved hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0031 | FTN_0031 | Transcriptional regulator, LysR family | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0035 | pyrF | Orotidine 5′-phosphate decarboxylase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0036 | pyrD | Diyroorotate dehydrogenase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0045 | FTN_0045 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0055 | tyrA | Prephenate dehydrogenase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0090, FTN_1556, FTN_1061, FTN_0954 | acpABC, hap | Acid phosphatasesc | Ar | J774A.1, activated THP-1, BALB/c | 13, 133, 135 |

| FTN_0096 | FTN_0096 | Conserved hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0097 | FTN_0097 | Aromatic amino acid transporter of the hydroxy/aromatic amino acid permease family | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0098 | gidB | Methyltransferase, glucose-inhibited cell division protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0111 | ribH | Riboflavin synthase beta-chain | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0112 | ribA | RibA/GTP-cyclohydrolase II | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0113 | ribB | Riboflavin synthase a-subunit 3,4-digydroxy-2-butanone 4-phosphate synthetase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0132 | FTN_0132 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_0133 | FTN_0133 | RNase II family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0143 | FTN_0143 | Monovalent cation:proton antiporter | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0169 | FTN_0169 | Conserved hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0177 | purH | AICAR transformylase/IMP cyclohydrolase | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199, 213 |

| FTN_0178 | purA | Adenylosuccinate synthetase | Ar/In | J774A.1, BALB/c | 158 |

| FTN_0196 | cyoB | Cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase subunit I | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0197 | cyoC | Cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase subunit III | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0198 | cyoD | Cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase subunit IV | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0199 | cyoE | Heme O synthase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0202 | pdxY | Pyridoxal/pyridoxine/pyridoxamine kinase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0205 | FTN_0205 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0208 | FTN_0208 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0210 | FTN_0210 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0211 | pcp | Pyrrolidone-carboxylate peptidase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0217 | FTN_0217 | l-Lactate dehydrogenase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0229 | pyrH | Uridylate kinase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0240 | rplD | 50S ribosomal protein L4 | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0241 | rplW | 50S ribosomal protein L23 | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0248 | rpsQ | 30S ribosomal protein S17 | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_0265 | rplQ | 50S ribosomal protein L17 | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0266 | htpG | Chaperone Hsp90, heat shock protein HtpG | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199, 213 |

| FTN_0280 | FTN_0280 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0281 | FTN_0281 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0289 | FTN_0289 | ProP osmoprotectant transporter, fragment | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0292 | FTN_0292 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0295 | lpxF | Phosphatidic acid phosphatase, PAP2 superfamily | Ar | C57BL/6 | 209 |

| FTN_0296 | FTN_0296 | Amino acid transporter | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0297 | FTN_0297 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_0298 | gplX | Fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase II | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_0299 | putP | Proline:Na+ symporter | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0300 | FTT1629c | Glycosyl transferase, group 2 | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_0302 | FTN_0302 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0326 | FTN_0326 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0330c | minD | Septum formation inhibitor-activating ATPase | In | PM, BMDM, C57BL/6NCrIBR | 8 |

| FTN_0337 | fumA | Fumarate hydratase, class I | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199 |

| FTN_0340 | FTN_0340 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0344 | FTN_0344 | Aspartate:alanine exchanger family | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0347 | fkpB | FK506 binding protein-type peptidyl-prolyl, cis-trans | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0351 | FTN_0351 | Hypothetical protein, novel liver | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0365 | FTN_0365 | Conserved hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0393 | FTN_0393 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0395 | FTN_0395 | Transcriptional regulator, ArsR family | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0397 | gpsA | Glycerol-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0400 | FTN_0400 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0402 | aroC | Chorismate synthase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0416 | FTN_0416 | Conserved hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0417 | folD | Methylene tetrahydrofolate | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_0419 | purM | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamide cyclo-ligase | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199, 213 |

| FTN_0420 | purCD | SAICAR synthetase/phosphoribosylamine-glycine ligase | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199, 213 |

| FTN_0422 | purE | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase, catalytic subunit | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0426 | FTN_0426 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0427 | tul4 | Lipoprotein of unknown function | Ar/In | J774A.1c | 110 |

| FTN_0429 | FTN_0429 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0430 | lpnB | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_0431 | FTN0431 | Type IV pilus glycosylation protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0436 | FTN_0436 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0437 | FTN_0437 | Hydrolase, HD superfamily | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0438 | rrmJ | 23S rRNA methylase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0443 | maeA | NAD-dependent malic enzyme | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_0444 | FTT0918 | Membrane protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 181 |

| FTN_0480 | fevR | Protein of unknown function | Ar | BMDM, C57BL/6 | 20 |

| FTN_0488 | cspC | Cold shock protein, | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0493 | mtn | Adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0494 | FTN_0494 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0494 | FTN_0494 | BNR/Asp box repeat protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0503 | lolD | Lipoprotein releasing system, subunit D, ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0504 | cadA | Lysine decarboxylase, inducible | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0505 | gcvT | Glycine cleavage complex T protein (aminomethyltransferase) | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0506 | gcvH | Glycine cleavage system H protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0507 | gcvP1 | Glycine cleavage system P protein, subunit 1 | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0514 | pgm | Phosphoglucomutase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0536 | yjjK | ABC transporter, ATP binding protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0537 | FTN_0537 | Proton-dependent oligopeptide | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0544 | FTN_0544 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0545 | flmF2 | Glycosyl transferase, group 2 | Tp | BALB/c, C57BL/6 | 101, 213 |

| FTN_0546 | flmK | Dolichyl-phosphate-mannose-protein, mannosyltransferase family protein | Tp | BALB/c, C57BL/6 | 101, 213 |

| FTN_0554 | FTN_0554 | RNA methyltransferase, | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0559 | surA | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0560 | ksgA | Dimethyladenosine transferase, kasugamycin resistance | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0571 | xasA | Amino acid-polyamine-organocation | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_0578 | FTN_0578 | Major facilitator superfamily transport | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0582 | gph | Phosphoglycolate phosphatase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0594 | sucC | Succinyl-coenzyme A synthetase, beta chain | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_0599 | FTN_0599 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0609 | pnp | Polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0624 | sdaC1 | Serine transporter | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0643 | FTN_0643 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0646 | cscK | ROK family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0651 | cdd | Cytidine deaminase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0669 | deoD | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0678 | FTN_0678 | Drug:H+ antiporter-1 (DHA1) family | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0689 | ppiC | Parvulin-like peptidyl-prolyl isomerase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0690 | deaD | DEAD box subfamily, ATP-dependent | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0710 | FTN_0710 | Type I restriction-modification system | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0713 | ostA2 | Organic solvent tolerance protein OstA | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0714 | FTT0742 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199 |

| FTN_0720 | FTN_0720 | Transcriptional regulator, LclR family | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_0728 | FTN_0728 | Cation efflux family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0737 | potI | ATP binding cassette putrescine uptake | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0740 | FTN_0740 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0756 | fopA | OmpA family protein | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_0757 | FTN_0757 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0768 | tspO | Tryptophan-rich sensory protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0787 | rep | UvrD/REP superfamily I | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0806 | FTN_0806 | β-Glucosidase-related glycosidase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0810 | FTN_0810 | ROK family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0814 | bioF | 8-Amino-7-oxononanoate synthase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0815 | bioB | Biotin synthase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0816 | bioA | Oxononanoate aminotransferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0817 | FTN_0817 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0818 | FTN_0818 | Lipase/esterase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0821 | FTN_0821 | AMP binding family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0822 | FTN_0822 | Chorismate binding family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0823 | trpG | Anthranilate synthase component II | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0824 | FTN_0824 | Major facilitator superfamily | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0825 | FTN_0825 | Aldo/keto reductase family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0840 | mdaB | NADPH-quinone reductase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0848 | FTN_0848 | Amino acid antiporter | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0853 | sufD | SufS activator complex, SufD subunit | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0857 | FTN_0857 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0869 | FTT0989 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Ar/In | BMDM, C57BL/6 | 21 |

| FTN_0873 | dcd | dCTP deaminase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0877 | cls | Cardiolipin synthetase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0881 | FTN_0881 | Fe2/Zn2 uptake regulator protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0891 | ruvB | Holliday junction DNA helicase, subunit B | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0918 | FTN_0918 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0925 | FTN_0925 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_0933 | FTN_0933 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0938 | FTN_0938 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_0998 | FTN_0998 | Potassium channel protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1006 | FTN_1006 | Transporter-associated protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1015 | FTN_1015 | Isochorismatase family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1016 | FTN_1016 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_1029 | FTN_1029 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1030 | lipA | Lipoic acid synthetase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1038 | FTN_1038 | Conserved hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1055 | lon | DNA binding, ATP dependent | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1063 | FTN_1063 | tRNA-methylthiotransferase MiaB protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1064 | phoH | PhoH-like protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1066 | FTN_1066 | Metal ion transporter protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1090 | FTN_1090 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1098 | FTN_1098 | Conserved hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1107 | metIQ | Methionine uptake transporter family | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1111 | FTN_1111 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1112 | cphA | Cyanophycin synthetase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1131 | putA | Multifunctional protein, transcriptional repressor of proline utilization, proline dehydrogenase, pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1132 | FTN_1132 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1133 | FTN_1133 | Protein of unknown function, novel lung, spleen | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1146 | aspC2 | Aspartate aminotransferase | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_1148 | FTN_1148 | Glycoprotease family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1157 | FTN_1157 | GTP binding translational elongation | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1165 | FTN_1165 | Predicted ATPase of the PP loop | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1177 | sbcB | Exodeoxyribonuclease I | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1186 | pepO | M13 family metallopeptidase | Ar/In | C57BL/6 | 21 |

| FTN_1196 | FTN_1196 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1199 | FTN_1199 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1200 | capC | Capsule biosynthesis protein CapC | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1201 | capB | Capsule biosynthesis protein CapB | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1209 | cphB | Cyanophycinase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_1211 | FTN_1211 | Haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1212 | FTN_1212 | Glycosyltransferase group 1 family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1213 | FTN_1213 | Glycosyltransferase family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1214 | FTN_1214 | Glycosyltransferase family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1217 | FTN_1217 | ABC transporter, ATP binding and membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1218 | FTN_1218 | Glycosyltransferase, group 1 | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_1219 | gale | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1220 | FTN_1220 | Bacterial sugar transferase family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1232 | FTN_1232 | Conserved hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1241 | dedA2 | DedA family protein | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_1242 | dedA1 | DedA family protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1243 | recO | RecFOR complex, RecO component | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1254 | FTN_1254 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1255 | FTN_1255 | Glycosyl transferase family 8 protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1256 | FTN_1256 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1257 | FTN_1257 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1259 | glyA | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_1272 | FTN_1272 | Proton-dependent oligopeptide | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1273 | fadD1 | Acyl coenzyme A synthetase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1276 | emrA1 | HlyD family secretion protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1277 | FTN_1277 | Outer membrane efflux protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1284 | dnaK | Chaperone, heat shock protein, HSP 70 family | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199 |

| FTN_1290 | mglA | Macrophage growth locus, protein A | Ar/In | J774A.1, Acanthamoeba castellanii, BALB/cAnNHsd, BALB/c | 110, 111, 214 |

| FTN_1292 | FTN_1292 | Solute:sodium symporter | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1298 | FTN_1298 | GTPase of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1309 | pdpA | Protein of unknown function | Ar | CE, BALB/cByJ | 176, 177, 213 |

| FTN_1310 | pdpB | Protein of unknown function | Ar/In, Tp | BMDM, C57BL/6, J774A.1, RAW, BALB/c | 21, 199, 213 |

| FTN_1311 | FTN_0311 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1312 | FTN_1312 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106, 213 |

| FTN_1313 | FTN_1313 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1314 | FTN_1314 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1315 | FTN_1315 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1316 | FTN_1316 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1317 | FTN_1317 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1318 | cds2 | Hypothetical protein | Ar/In, Tp | BMDM, C57BL/6 | 21, 213 |

| FTN_1319 | FTN_1319 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1320 | FTN_1320 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1321 | iglD | Intracellular growth locus protein D | Ar/In, Tp | BALB/c, hMDMs, C57BL/6 | 106, 172, 213 |

| FTN_1322 | iglC | Intracellular growth locus, protein C | Ar/In | J774A.1, Acanthamoeba castellanii, BALB/cAnNHsd, C57BL/6 | 110, 111, 142, 213 |

| FTN_1323 | iglB | Intracellular growth locus, protein B | In | J774, BALB/c | 39, 213 |

| FTN_1324 | iglA | Intracellular growth locus protein A | Ar | J774A.1, CE | 46, 213 |

| FTN_1325c | pdpD | Protein of unknown function | Ar/In | BMDM, BALB/cByJ | 138, 213 |

| FTN_1326 | FTN_1326 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1333 | tktA | Transketolase I | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199 |

| FTN_1349 | FTN_1349 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1351 | FTN_1351 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1355 | FTN_1355 | Regulatory factor, Bvg | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1357 | recB | Exodeoxyribonuclease V b-chain | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1362 | FTN_1362 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1400 | FTN_1400 | S-Adenosylmethionine dependent | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1403 | flmF1 | Glycosyltransferase | Tp | BALB/c, C57BL/6 | 101 |

| FTN_1415 | FTN_1415 | Thioredoxin | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1417 | manB | Phosphomannomutase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1421 | wbtH | Asparagine synthase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1423 | wbtG | Glycosyl transferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1425c-FTN_1427c | wbtDEF | LPS O-antigen biosynthetic gene cluster | Ar/In | BALB/c | 200, 213 |

| FTN_1432 | wbtA | dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1439 | fadA | Acetyl coenzyme A acetyltransferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1440 | FTN_1440 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1444 | ocd | Ornithine cyclodeaminase, mu-crystallin homolog | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_1455 | FTN_1455 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1459 | FTN_1459 | Short-chain dehydrogenase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1464 | lepB | Signal peptidase I | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1465 | pmrA | Two-component response regulator, orphan | Ar | J774A.1, activated THP-1, HeLa, BALB/c | 134 |

| FTN_1467 | proC | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1471 | pcs | (CDP-alcohol) phosphatidyltransferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1500 | FTN_1500 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1501 | FTN_1501 | Na+/H+ antiporter | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1507 | FTN_1507 | Pilus assembly protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1513 | xerC | Integrase/recombinase XerC | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1518 | relA | GTP pyrophosphokinase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1433 | FTN_1433 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1438 | fadB-acbP | Fusion product of 3-hydroxacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase and acyl coenzyme A binding protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1470 | ispA | Geranyltransferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1471 | pcs | Phosphatidylcholine synthase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1534 | FTN_1534 | Conserved protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1536 | FTN_1536 | Amino acid-polyamine-organocation | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1538 | groL | Chaperone protein, GroEL | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1548 | FTN_1548 | Conserved hypothetical lipoprotein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1551 | ampD | N-Acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1558 | xerD | Integrase/recombinase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1567 | rpoC | DNA-directed RNA polymerase, beta′ subunit/160-kDa subunit | Tp | RAW | 199 |

| FTN_1582 | FTN_1582 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1587 | FTN_1587 | Protein of unknown function | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1588 | FTN_1588 | Major facilitator superfamily transport | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1592 | oppB | Peptide/opine/nickel uptake transporter (PepT) family protein | Ar/In | C57BL/6 | 21 |

| FTN_1597 | prfC | Peptide chain release factor 3 | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1602 | deoB | Phosphopentomutase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1607 | cca | tRNA nucleotidyltransferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1608 | dsbB | Disulfide bond formation protein | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c, C57BL/6 | 199, 213 |

| FTN_1611 | FTN_1611 | Major facilitator superfamily transport | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1617 | qseC | Sensor histidine kinase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1633 | apt | Adenine phosphoribosyltransferase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1634 | sucB | Dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1639 | sdhC | Succinate dehydrogenase, cytochrome b556 | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1645 | FTN_1645 | AtpC ATP synthase, F1 sector, subunit epsilon | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1653 | FTN_1653 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1654 | FTN_1654 | Transport protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1655 | rluC | Ribosomal large subunit pseudouridine synthase C | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1656 | FTN_1656 | ATPase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1657 | FTN_1657 | Major facilitator superfamily transport protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1658 | hisS | Histidyl-tRNA synthetase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1659 | rbfA | Ribosome binding factor A | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1665 | FTN_1665 | Magnesium chelatase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1673 | nuoH | NADPH dehydrogenase I, H subunit | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1682 | figA (fslA) | Siderophore biosynthesis protein | Ar/In | J774A.1 | 47, 213 |

| FTN_1683 | FTN_1683 | Conserved membrane protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1684 | lysA | Diaminopimelate decarboxylase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1686 | figE | Hypothetical membrane protein involved in siderophore uptake | Ar | BALB/c | 132 |

| FTN_1699 | purL | Phosphoribosylformylglycinamide synthase | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, BMDM, BALB/c | 199, 213 |

| FTN_1700 | purF | Amidophosphoribosyltransferase | Ar/In | J774A.1, BALB/c | 158, 213 |

| FTN_1715 | kdpD | Two-component sensor protein KdpD | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1726 | FTN_1726 | Pyridoxal-dependent decarboxylase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1731 | pip | Proline iminopeptidase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1743 | clpB | ClpB protein | Tp | RAW | 199, 213 |

| FTN_1744 | FTN_1744 | Chitinase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1745 | purT | Phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase 2 | Tp | C57BL/6 | 213 |

| FTN_1753 | FTN_1753 | Rieske (2Fe-2S) domain protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1756 | bcp | Bacterioferritin comigratory protein | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1760 | FTN_1760 | Zinc binding alcohol dehydrogenase | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

| FTN_1778 | trpE | Anthranilate synthase component I | Tp | C57BL/6 | 106 |

Ar, allelic replacement; In, insertion; Tp, transposon insertion.

BMDM, bone marrow-derived macrophages; PM, peritoneal macrophages; CE, chicken embryos; hMDMs, human monocyte-derived macrophages; RAW, RAW264.7 murine macrophages.

Attenuated phenotype more pronounced with accumulated mutations.

TABLE 3.

F. tularensis subsp. holarctica genes involved in pathogenesis

| Locus tag | Name | Function | Method(s)a | Cells/animals in which mutant strain is attenuatedb | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTL_0009 | FTT1747 | Outer membrane protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0010 | glpE | Thiosulfate sulfurtransferase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0012 | recA | Recombinase A protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0028-FTL_0030 | carA, carB, pyrB | Uracil biosynthesis | Tp | MDM | 179 |

| FTL_0050 | FTT1645 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124 |

| FTL_0058 | FTT1688 | Aromatic amino acid transporter of the hydroxy/aromatic amino acid permease family | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_0073 | FTT1676 | Membrane protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0094 | clpB | Caseinolytic protease | Ar, Tp, STM | BMM, J774A.1c, BALB/c | 124, 129, 191 |

| FTL_0111 | iglA | Intracellular growth | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0112 | iglB | Intracellular growth | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0113 | iglC | Intracellular growth | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0113, FTL_1159 | iglC1, iglC2 | Intracellular growth locus C | Ar | J774A.1, PM, PEC, BALB/c | 82, 117 |

| FTL_0133 | feoB | Ferrous iron transport protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0193 | cyoC | Cytochrome o-ubiquinol oxidase subunit III | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0257 | rpmJ | 50S ribosomal protein L36 | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0304 | FTT1490 | Na+/H+ antiporter | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_0337 | FTT0843 | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0382 | rocE | Amino acid permease | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0387 | aspC1 | Aspartate aminotransferase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0395-FTL_0396 | purMCD | Purine biosynthesis | Ar/In, Ar | J774A.1, THP-1, PM, A549, BALB/c | 145, 146 |

| FTL_0421 | tul4 | Lipoprotein, T-cell-stimulating antigen | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0428 | parB | Chromosome partition protein B | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0430 | FTT0910 | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0439 | FTT0919 | Hypothetical outer membrane protein | Tp | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124 |

| FTL_0439 | FTT0918 | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0440 | FTT0920 | Transposase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0456 | rpsU1 | 30S ribosomal protein S21 | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0483 | glgB | Glycogen branching enzyme, GlgB; polysaccharide metabolism | Tp, STM | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124, 191 |

| FTL_0485 | glgC | Glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0514 | FTT1611 | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0519 | minD | Division inhibitor ATPase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0520 | minC | Septum site-determining protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0525 | fumA | Fumarate hydratase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0540 | lpxB | Lipid A-disaccharide synthase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0544 | FTT1564 | Hypothetical protein | Tp | J774A.1, BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0552 | pmrA | Two-component response regulator, orphan | Ar/In | J774A.1, PM, MH-S, BALB/c, C57BL/6 | 165 |

| FTL_0584 | fadB | Acyl coenzyme A binding protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0589 | FTT1525c | Hypothetical membrane protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0592 | wbtA | dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase | Ar, Tp | J774A.1, BALB/c, BALB/cByJ | 124, 160, 180, 191 |

| FTL_0594 | wbtC | UDP-glucose-4-epimerase | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_0597 | wbtF | NAD-dependent epimerase, LPS modification | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0601 | wbtI | Sugar transaminase/perosamine synthetase | Pm | BALB/c | 115 |

| FTL_0606 | wbtM | dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_0616 | rpoA2 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase, subunit | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0617 | bfr | Bacterioferritin | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0645 | FTT1416c | Lipoprotein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0663 | FTT1400c | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0706 | FTT1238c | Hypothetical membrane protein | Tp | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124 |

| FTL_0723 | FTT1221 | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0766 | ggt | Gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase | Tp | J774A.1, RAW, THP-1, BMM, BALB/c | 4, 124 |

| FTL_0768 | bipA | GTP-binding translational elongation factor Tu and G family protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0789 | aspC2 | Aspartate aminotransferase, amino acid biosynthesis | Tp, STM | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124, 191 |

| FTL_0803 | FTT1152 | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0837 | metIQ | d-Methionine transport protein (ABC transporter) | Tp, STM | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124, 191 |

| FTL_0838 | metN | d-Methionine transport protein (ABC transporter) | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_0846 | FTT1117c | Isochorismatase hydrolase family protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0878 | FTT0610 | DNA/RNA endonuclease family | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_0886 | FTT0618c | Conserved hypothetical protein YleA | Tp | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124 |

| FTL_0891 | tig | Molecular chaperone | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0892 | clpP | ATP-dependent Clp protease subunit P | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0893 | clpX | ATP-dependent Clp protease subunit X | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0894 | lon | ATP-dependent protease Lon | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0899 | hflX | Protease, GTP binding subunit | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0903 | hflK | Protease modulator | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0928 | elbB | DJ-1/PfpI family protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0950 | rplY | 50S ribosomal protein L25 | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_0960 | sthA | Soluble pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1029 | pilF | Type IV pilus lipoprotein | Ar | C3H/HeN | 25 |

| FTL_1030 | rluB | Ribosomal large subunit pseudouridine synthase B | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1071, FTL_1478 | guaA, guaB | Guanine biosynthesis | Ar/In | J774, BALB/c | 170 |

| FTL_1075 | FTT1015 | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1096 | FTT1103 | Hypothetical lipoprotein | Tp | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124, 191 |

| FTL_1096 | FTT1103 | Lipoprotein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1097 | FTT1102 | Macrophage infectivity potentiator | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1134 | NA | Membrane protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1158, FTL_0112 | iglB | Intracellular growth locus B | Ar | J774A.1 | 19 |

| FTL_1225 | FTT0975 | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1233 | FTT0968c | Amino acid antiporter | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1240 | aroG | Phospho-2-dehydro-3-deoxyheptonate aldolase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1262 | FTT0945 | Chorismate family binding protein, aromatic amino acid and folate biosynthesis | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_1266 | lipP | Lipase/esterase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1273 | bioF | 8-Amino-7-oxononanoate synthase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1274 | bioC | Biotin synthesis | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1275 | bioD | Dethiobiotin synthetase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1328 | fopA | Outer membrane-associated protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1354 | FTT0759 | Membrane protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1392 | deaD | Cold shock DEAD box protein A | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1393 | ppiC | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase or parvulin | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1404 | rplT | 50S ribosomal protein L20 | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1414 | capA | Transmembrane HSP60 family protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1414-FTL_1416 | capACB | Capsule biosynthesis | Ar, Tp | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124, 191 |

| FTL_1415 | capC | Capsular polyglutamate biosynthesis protein CapC | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1416 | capB | Capsular polyglutamate biosynthesis protein CapB | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1419 | cphB | Cyanophycinase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1452 | rpmA | 50S ribosomal protein L27 | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1458 | secA | Preprotein translocase, subunit A | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1461 | deoD | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1473 | uvrA | DNA excision repair enzyme, subunit A | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1474 | greA | Transcription elongation factor | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1475 | FTT1314c | Type IV pilus fiber building block protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1504 | katG | Catalase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1528 | FTT0708 | Major facilitator superfamily transport protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1542 | migR | Transcriptional regulator | Ar | MDM | 22 |

| FTL_1553 | sucC | Succinyl coenzyme A synthetase beta chain | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1554 | sucD | Succinyl coenzyme A synthetase alpha chain | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1581 | tivA | Hypothetical lipoprotein | Ar/In | CE, MDM | 93 |

| FTL_1583 | xasA | Glutamate-aminobutyric acid antiporter, XasA; amino acid transport | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_1601 | yibK | tRNA/rRNA methyltransferase | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1622 | FTT0444 | Multidrug transporter | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1623 | FTT0443 | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1664 | deoB | Phosphopentomutase | Ar/In | CE, MDM, DC, HEK-293 | 93 |

| FTL_1670 | dsbB | Disulfide bond formation protein, DsbB | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_1672 | acrB | RND efflux pump | In, STM | BALB/c | 15, 191 |

| FTL_1678 | FTT0101 | Membrane protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1701 | gplX | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase | Tp, STM | J774A.1, BALB/c | 124, 191 |

| FTL_1750 | secE | Preprotein translocase, subunit E | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1771 | pilT | Twitching motility protein PilT | Tp | C3H/HeN | 25 |

| FTL_1793 | sodB | Fe-superoxide dismutase | Ar | BALB/c, C57BL/6, MH-S | 9 |

| FTL_1806 | FTT0053 | Major facilitator superfamily transporter | Tp | J774A.1 | 124 |

| FTL_1832 | FTT0029c | Unknown | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1865 | tolC | Glutamate decarboxylase | Ar | C3H/HeN | 77 |

| FTL_1867 | yegQ | Protease | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1912 | rpsA | 30S ribosomal protein S1 | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1914 | ripA | Hypothetical protein | Ar | J774A.1, TC-1, C57BL/6 | 72 |

| FTL_1936 | FTT0209c | Periplasmic solute binding family protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_1947 | yjjk | ABC transporter ATP binding protein | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_R0003 | 16S rRNA | 16S rRNA | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTL_R0004 | tRNA-Ile | tRNA-isoleucine | STM | BALB/c | 191 |

| FTT0890 | pilA | Type IV pilus fiber building block protein | Recomb. | C57BL/6 | 65 |

Ar, allelic replacement; In, insertion; Tp, transposon insertion; STM, signature-tagged mutagenesis; Recomb., direct repeat-mediated deletion.

MDM, monocyte-derived macrophages; PM, peritoneal macrophages; PEC, peritoneal exudate cells; CE, chicken embryos; DC, dendritic cells.

Intermediate attenuation phenotype.

TABLE 4.

F. tularensis subsp. tularensis genes involved in pathogenesis

| Locus tag | Name | Function | Method(s)a | Cells/animals in which mutant strain is attenuatedb | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTT0026c | fslE | Siderophore uptake | Tp, Ar | BALB/c | 100, 159 |

| FTT0056c | FTT0056c | Major facilitator superfamily transport protein | Tp | Hep G2 | 155 |

| FTT0069c | FTT0069 | Unannotated | Tp | BALB/c | 100 |